Introduction

Governments consistently make claims that provide justification for why the regimes over which they preside are entitled to rule. These claims legitimate the rules, both formal and informal, on who holds authority, how they can exercise it, and to what ends, thereby empowering rulers to exercise authority, that is make collectively binding decisions. Thus, legitimation strategies are not ‘cheap talk’ but have fundamental political consequences. Different claims to legitimacy have ramifications for how a country functions (Burnell, Reference Burnell2006), as well as for the nature of the relationship between the rulers and ruled (Weber, Reference Weber[1922] 1978). A regime’s claim to legitimacy is important in explaining how it rules and whether it is stable (Easton, Reference Easton1965; Weber, Reference Weber[1922] 1978).

In the literature on democratic rule, the establishment and maintenance of legitimacy – often procedural – is widely discussed and well-established (Lipset, Reference Lipset1959; Linz, Reference Linz, Linz and Stepan1978; Schaar, Reference Schaar1981; Almond and Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1989). Despite a traditional and largely European research tradition on the legitimation strategies of authoritarian regimes (Friedrich, Reference Friedrich1961; Pye, Reference Pye, Binder and La Palombara1971; Gill, Reference Gill1982; Rigby and Fehér, Reference Rigby and Fehér1982; Lane, Reference Lane1984; Pakulski, Reference Pakulski1986; Bernhard, Reference Bernhard1993), the recent rationalist turn in the study of authoritarianism has focused on institutional factors and their material and distributive consequences, and thereby has overlooked the effect of different legitimation strategies on citizen-state relations. Despite a recent upsurge in research on legitimacy, also in relation to authoritarian regimes (von Soest and Grauvogel, Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017; Gerschewski, Reference Gerschewski2018) and populism (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018), we still lack in-depth empirical explorations of how governments invoke different legitimacy claims and how this aspect of rule relates to others such as co-optation, repression of or the provision of public goods (Gerschewski, Reference Gerschewski2013). In particular, the lack of cross-sectional and longitudinal data on legitimation strategies that cut across the democracy–autocracy divide hampers scholarly progress. Existing studies of political legitimacy overwhelmingly address democracies (e.g. Almond and Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1989; Kaase and Newton, Reference Kaase and Newton1995; Inglehart and Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Booth and Seligson, Reference Booth and Seligson2009; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Hurrelmann, Krell-Laluhová, Wiesner and Nullmeier2010) and, occasionally, autocracies (Kailitz, Reference Kailitz2013).

We address this gap with a data collection strategy that differs from past approaches in two important ways. First, we comparatively assess the legitimation strategies of both democracies and autocracies in an integrated framework. Second, most studies focus on whether citizens accept the legitimation claims of their rulers. In contrast, we focus on the legitimacy claims proffered by those in power. We, thus, explore the strategies that rulers use to seek legitimacy rather than legitimacy itself. Building on the rich tradition of theory in comparative politics and political sociology, we distinguish four legitimation strategies; (1) ideological (2) personalistic, (3) rational-legal (procedural), and (4) performance-based. We then measure the extent to which governments utilize these legitimation strategies for their respective regimes using V-Dem’s expert coding methods for generating latent variables for 183 countries from 1900 to 2019. The V-Dem measurement model ensures that the latent variables generated by the aggregation of the expert coding are highly comparable across time and space. Country experts rated the extent to which the government promotes or references its performance, the person of the leader, rational-legal procedures, and ideology in order to justify the regime in place. Additionally, the item on ideology asked the experts to further categorize its nature as nationalist, communist/socialist, conservative/restorative, religious, and/or separatist.

The paper proceeds as follows. We first introduce the concepts of legitimacy and discuss the varieties of legitimation strategies, as well as how the experts coded them. We then subject our data to validation procedures along the lines suggested by Adcock and Collier (Reference Adcock and Collier2001). We conduct three different tests, examining the convergent, content (face), and construct (nomological) validity of our measure. The construct validity test evaluates the performance of our leader indicator in assessing a well-established hypothesis – the reliance of populists on personalism and charismatic leadership. Our purpose in framing this particular test is to demonstrate the new measures’ potential to investigate important contemporary political phenomena such as populism, and in extension provide data for future work on democratic backsliding.

The concept of legitimacy and legitimation

Legitimacy is one of the most crucial, yet also most contested concepts in political science (Lipset, Reference Lipset1959; Rigby and Fehér, Reference Rigby and Fehér1982; Beetham, Reference Beetham1991; Weatherford, Reference Weatherford1992; Barker, Reference Barker2001; Levi et al., Reference Levi, Sacks and Tyler2009). From its etymological beginnings, legitimate rule was explicitly delineated from tyrannical rule. In this sense, legitimate rule was supposed to be free of arbitrariness and despotism. As such, legitimacy occupies a key position in democratic theory as well as the normative philosophy of the state. In contrast to this rich normative tradition, Weber developed a sophisticated analytical framework for understanding legitimacy empirically (Reference Weber[1922] 1978). In other words, instead of asking how the political rule should look, Weber proposed we observe how political rule actually is (Collins, Reference Collins1986). Weber’s strict empirical usage of the concept makes it possible to apply it to the understanding of how democratic and autocratic regimes work.

We proceed in the spirit of the Weberian understanding of legitimacy and use the term in an explicit empirical-analytical way. We thus seek to identify the narratives by which rulers try to justify their rule, irrespective of whether the regime is democratic or autocratic. Of course, we understand that legitimacy refers not only to the claims of rulers, but their reception by the ruled as well. We conceptually distinguish claims to legitimacy that every political regime voices about why it is entitled to rule (Beetham, Reference Beetham1991) from legitimacy itself, that is ‘the capacity of a political system to engender and maintain the belief that existing political institutions are the most appropriate or proper ones for the society’ (Lipset, Reference Lipset1959: 86). Within the scope of this article, we concentrate on the legitimacy claims made by the incumbent government in order to justify their rule.

Famously, Weber distinguished between three ideal types of legitimate rule – rational-legal, charismatic, and traditional. We take these three types of legitimate rule as a starting point for our data collection efforts. We understand rational-legal rule as being based ‘on a belief in the legality of enacted rules and the right of those elevated to authority under such rules to issue commands’ (Weber, Reference Weber[1922] 1978: 215). Rational-legal rule is grounded on the existence of an extensive, binding, and consistent set of laws, which regulate and discipline the conduct of authority. Those exercising rational-legal domination are usually selected by special means, via elections (democracy or oligarchy), appropriation (seizing power), or succession (monarchy). Yet, even their authority is usually subject to constraint by law.

In contrast, traditional rule is understood as being based on age-old, sanctified practices. It rests ‘on an established belief in the sanctity of immemorial traditions and the legitimacy of those exercising authority under them’ (Weber, Reference Weber[1922] 1978: 215). The rulers in such systems are appointed on the basis of established customs (primogeniture, tournament, election by small collegial bodies) and obeyed on the basis of this status. Obedience is usually based on a common socialization that stresses the importance of customary practices and adherence to them. Subordinates are loyal to the ruler (in contrast to rational-legal officials who are bound by a set of elaborate and externally established impersonal rules).

Lastly, charismatic rule is based on the extraordinary, supernatural, or exceptional qualities of an individual leader. Such leaders share an intense personal bond with a devoted following that believes in their extraordinary qualities. Because of this they have a powerful say in the shape of the social formations over which they preside. Weber attributes the power to ‘reveal’ or ‘ordain’, ‘normative patterns’ and/or ‘order’ to them (Weber, Reference Weber[1922] 1978: 215–216). In its pure form, charismatic rule is inherently unstable and short-lived. Any failure that calls the extraordinary nature of leadership into account will weaken it, and if successful, over time it will come to be routinized, in the direction of the other two forms of legitimacy. It eventually will be traditionalized or rationalized.

We take these three Weberian types of legitimate rule as a theoretical starting point and expand on them by incorporating more recent work on the topic. Beyond the Weberian tradition, a second important conceptualization upon which we draw stems from David Easton (1965; Reference Easton1975). While Easton has a rather narrow understanding of legitimacy, we make use of his major distinction between two modes of ‘support’ – diffuse and specific. Diffuse support refers to ‘evaluations of what an object is or represents – to the general meaning it has for a person – not of what it does’ (Easton, Reference Easton1975: 444). In our data collection efforts, we fill diffuse support with concrete ‘meaning’, referring to specified political ideologies or models of society that rulers employ to justify their rule. They range from nationalism to religious ideologies, from socialism and communism to restorative or conservative ideologies.

In contrast to diffuse support, specific support is for Easton a short-term evaluation of the performance of the political system, which is a ‘quid pro quo for the fulfillment of demands’ (Easton, Reference Easton1965: 268). It is based on a cost–benefit calculus; if the incumbent rulers fail to deliver, the population will withdraw its support.Footnote 1 This form of performance legitimacy has gained currency in international research (White, Reference White1986; Hechter, Reference Hechter2009; Zhao, Reference Zhao2009; von Soest and Grauvogel, Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017). There is some disagreement to what extent performance legitimacy should be subsumed under the rubric of legitimacy. From a Weberian perspective, legitimacy must entail more than simple obedience based on material or coercive incentives or sanctions (Weber, Reference Weber[1922] 1978). Such criticism would not however take issue with the idea that poor government performance can weaken its legitimacy (Lipset, Reference Lipset1959; Linz, Reference Linz, Linz and Stepan1978). In order to facilitate the empirical and comparative study of legitimacy claims, we also collected data on the performance-based justifications of authority.

Rational-legal, traditional, charismatic, as well as ideological and performance-based legitimacy claims are ideal types. They are drawn in pure terms so that they can be compared to an empirical reality as tools of measurement that allow us to judge the extent to which certain principles or mechanisms are present in any concrete social or political formation (Weber, Reference Weber[1904] 1949: 89–91). In fact, we expect any real-world system of authority to combine elements of more than one form of legitimation. Previous work has confirmed that rulers frequently invoke overlapping claims that combine elements of all forms at the same time to justify their rule (Alagappa, Reference Alagappa1995; Burnell, Reference Burnell2006; von Soest and Grauvogel, Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017).

While there are certain affinities between forms of legitimacy and certain regimes, there is no direct correspondence. Anyone familiar with contemporary democracy will immediately recognize the centrality of the rational-legal type as essential to common understandings of democratic practice. But even in democracy, we can see a routinized element of charisma in the popular election of leaders who preside over rational-legal systems (Bernhard, Reference Bernhard1999).

In contrast to the majority of the existing literature, which focuses on the acceptance of a regime, often by means of representative surveys, we analyze the different bases on which democratic and nondemocratic regimes claim legitimacy (in general Kailitz, Reference Kailitz2013; for autocracies, Burnell, Reference Burnell2006; Grauvogel and von Soest, Reference Grauvogel and von Soest2014; von Soest and Grauvogel, Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017; Gerschewski, Reference Gerschewski2018). There are strong theoretical and empirical reasons to expect that legitimacy claims fundamentally shape a regime’s means of rule and its stability. First and most fundamentally, the sources of legitimation influence the structures of domination (Alagappa, Reference Alagappa1995: 3). As Weber, (Reference Weber[1922] 1978: 212–213) found, ‘the type of obedience, the type of administrative staff developed to guarantee it, the mode of exercising authority – all depend on the type of legitimacy claimed’. For instance, elaborated claims to legitimacy are likely to create collective identification which in turn may enhance elite cohesion and citizen support for the regime in place (Barker, Reference Barker2001; LeBas, Reference LeBas2013).

Second, the claims to legitimacy set the framework within which individual actors and organized groups can influence structures of power and can express dissent (Alagappa, Reference Alagappa1995: 4). For example, Schlumberger (Reference Schlumberger2010) showed that the Gulf monarchies use religious claims to legitimacy to avert the rise of Islamic opposition movements in their countries. Third, claims to legitimacy allow us to track and understand when rulers change the basis on which they justify their right to rule, particularly when facing acute economic or political crises (White, Reference White1986). For instance, in Russia, the personal factor has become far more pronounced since Vladimir Putin started his second stint as president in 2012. At that time, the country’s economic prospects had significantly deteriorated making it harder to focus on the regime’s success in providing economic growth and social security. This discursive focus on his person went hand in hand with the increasing concentration of power by President Putin (Baturo and Elkink, Reference Baturo and Elkink2014; von Soest and Grauvogel, Reference von Soest, Grauvogel, Ahrens, Brusis and Wessel2015). For these reasons, we are interested in the nature of the legitimacy claims made by the government and proceed by developing measures to capture these.

Measurement strategy

Based on these theoretical considerations, we compiled a list of five questions that mirror the most important legitimacy claims. As we outlined above, claims to legitimacy regularly rest on different components. They are not mutually exclusive but often invoked in parallel (e.g. Alagappa, Reference Alagappa1995). Based on the classic conceptualization of legitimization derived from Weber and its expansion with political ideologies and performance legitimation, we formulated five questions to country experts. These ask them to identify how the government justifies the system of rule – whether it does so in terms of rational-legal rule, the qualities of the leader, its political ideology, and/or its performance.

The understanding of ideology we use in our questionnaire is narrow.Footnote 2 It refers to any set of ideas that are used to justify the exercise of authority. Experts were asked to indicate if the government justified its rule using nationalist, socialist or communist, restorative or conservative, separatist or autonomist, or religious ideology (the questions and instructions are presented in Table 8 in the Appendix). The question captures ideologies with illiberal content. Those interested in capturing liberal ideology as a justification for authority can treat the absence of an illiberal ideology as an indicator of that, or rely on the question on rational-legal legitimation, as liberalism relies strongly on procedural justification of the exercise of power.

The design of the questions allows us to directly capture two of Weber’s three ideal types through the questions on the qualities of the leader and rational-legal justifications for rule. The third Weberian type, claims based on tradition, is captured by the restorative or conservative and religious responses to the ideology question.Footnote 3 Beyond the Weberian types, we further distinguish diffuse forms from specific (performance) legitimacy in Easton’s sense and other ideological justifications.

The five items in the legitimation battery were all coded by country experts. Except for the item on ideology,Footnote 4 the expert ratings for the other four items were entered into V-Dem’s measurement model, which converts expert scores into an interval latent variable. This is a Bayesian item response theory model that estimates country-year point estimates on the basis of the experts’ coding. Patterns of coder (dis)agreement are used to estimate variations in reliability and systematic differences in thresholds between ordinal response categories, in order to adjust the point estimates of the latent concept. To achieve cross-national and temporal comparability, V-Dem uses lateral coders that code several countries for a shorter time period, and bridge coders that code the full-time series for more than one country, as well as anchoring vignettes that integrate information on coder thresholds into the model. The measurement model thus allows for both the threshold (i.e. how experts apply ordinal scales) and the reliability parameters (i.e. the degree to which experts diverge from the other experts who code the same case) to vary across coders (for a detailed description on the method and model parameters, see Coppedge et al. (Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Krusell, Marquardt, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Pernes, Stepanova, Tzelgov, Wang and Wilson2018), Pemstein et al. (Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Krusell and Miri2018) and Marquardt and Pemstein (Reference Marquardt and Pemstein2018)). The vignettes employed for the legitimation battery are included in Appendix Table 8.

The mean number of expert coders ranges from 5.44 to 5.93 for the legitimation variables over the 120 years (totaling 18,787 country-years). In general, there are fewer coders as we move back in time; the mean number of expert coders per country/year rises from 5.01 in 1900 to 6.34 in 2019. A full accounting of the number of coders for each variable and country/year are available in the Appendix (see Figures 15, 16, 17, and 18). Only a few countries are excluded from analysis in this paper due to an insufficient number of coders on these items in the V-Dem v.10 update (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Mechkova, Römer, Sundtröm, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2020).Footnote 5 Hopefully, this can be remedied in the next scheduled update of the data set.

Validity checks

In this section, we examine the validity of our data on the four different legitimation claims and the variation in the ideological character of those claims. Based on Adcock and Collier (Reference Adcock and Collier2001), we employ three different validation strategies. First, we examine the convergent validity (Adcock and Collier, Reference Adcock and Collier2001: 540f), that is to what extent our measure correctly aligns with related concepts. Then, we move on to content validation (Adcock and Collier, Reference Adcock and Collier2001: 538f) by assessing the extent to the values generated by our operationalization of the concepts conform to what is generally known about specific cases. This type of validation strategy is also often referred to as face validity. Finally, we assess its construct validity (Adcock and Collier, Reference Adcock and Collier2001: 542ff) by testing the performance of our indicator in assessing a well-established generality in the nature of populism – in our case on the reliance of populists on personalist justifications.

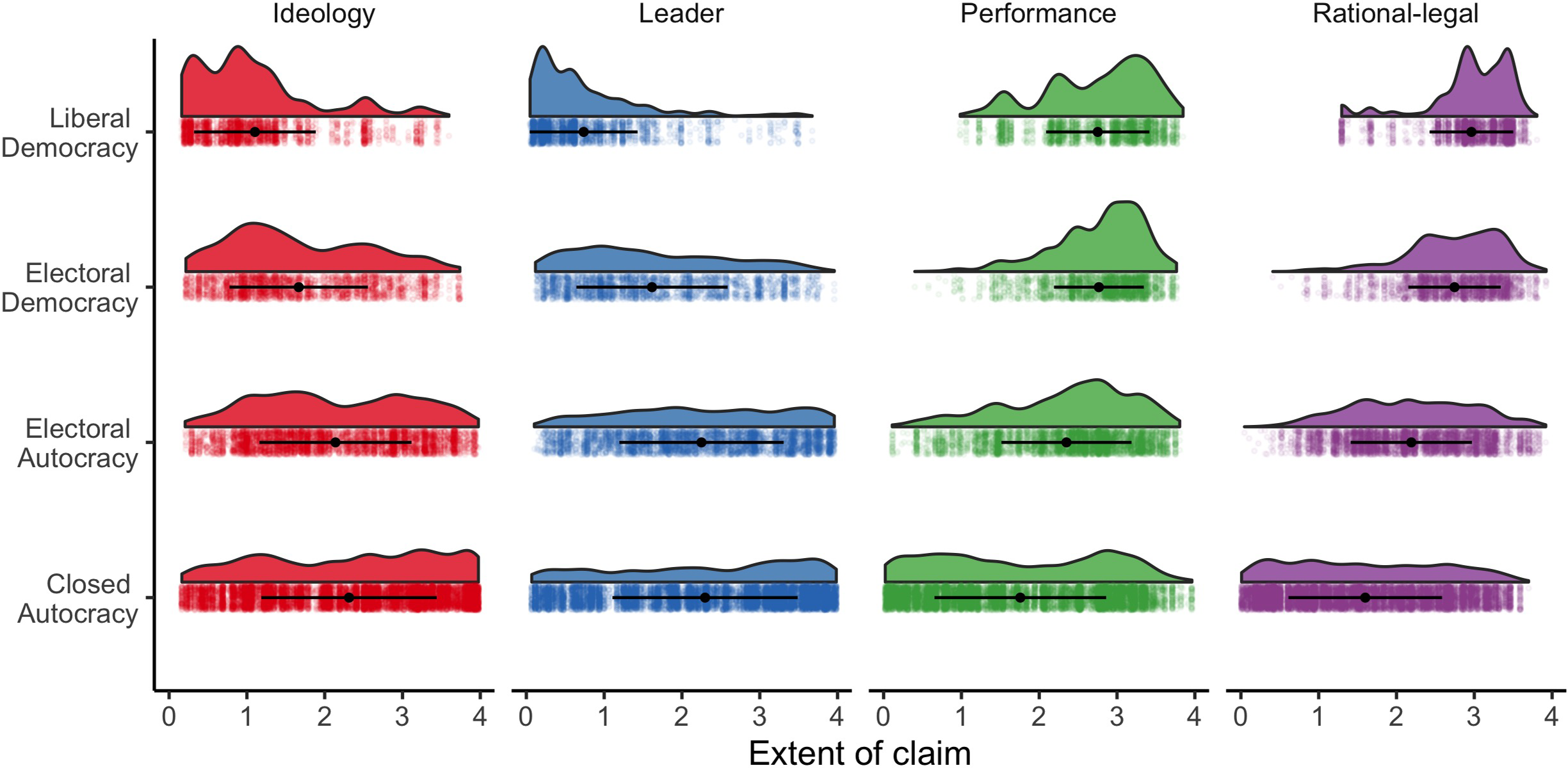

It is important to understand the distribution of data from a descriptive point of view before we go forward with the validation exercises. Figure 1 shows the distribution of claims for all available country-years, with dots and horizontal bars below indicating the mean and +/− 1 standard deviation. The x-axis denotes the extent of the claim with 0 representing ‘Not at all’, and 4 ‘Almost exclusively’. The y-axis denotes the number of observations, country-years, at each particular value. It shows that we have data points spanning the full spectrum for each claim and that the mean for Ideology, and the Leader is around the middle of the scale (at 2.03 and 2.00), and the distribution for Performance and Rational-legal is slightly skewed to the right with a mean at 2.15 and 2.06.

Figure 1. Distribution of legitimation claims.

Convergent validation: legitimation measures across regime types

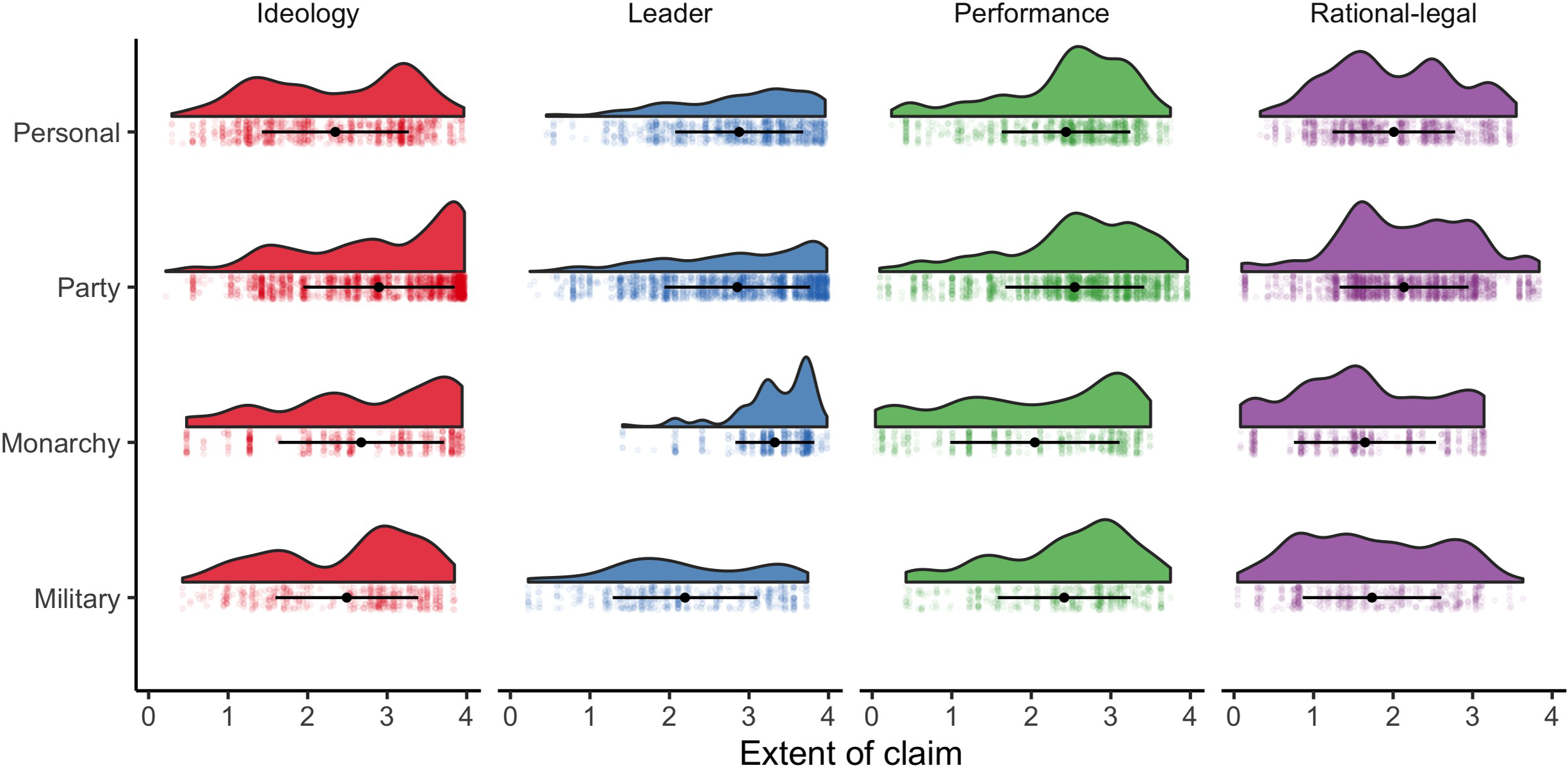

We frame this exercise in convergent validation in terms of a set of empirical expectations about the kinds of legitimation claims different regimes are more likely to make. Using the measures from Regimes of World (RoW) typology developed by V-Dem (Lührmann et al., Reference Lührmann, Tannenberg and Lindberg2018), Figure 2 plots the degree to which four different types of regimes rely on different legitimation claims from 1900 to the present. RoW distinguishes between closed autocracies without multiparty elections for the executive; electoral autocracies, which hold elections subject to relatively high levels of manipulation; electoral democracies; and liberal democracies. Our expectation is that autocracies should be more dependent on ideological and leadership-based claims, whereas democracies should be focused on rational-legal and performance criteria to justify authority. Our data are strongly in line with this expectation.

Figure 2. Distribution of claims by regime type.

Beginning with ideological claims, both closed and electoral autocracies rely more heavily on these claims to justify their rule, than the two democratic regime types. Among democracies, electoral democracies exhibit a greater propensity to utilize ideological rationales than liberal democracies. We see a similar pattern with regard to claims concerning the quality of the leader. Despite this, there are few liberal democracies that are exceptional in this regard. For instance, from 2004 to 2016, Israel relied heavily on the personal authority of domineering prime ministers Ariel Sharon and Benjamin Netanyahu. Another exception in this regard is South Africa under the presidency of Nelson Mandela. His role as the charismatic leader of the anti-apartheid movement, and its first democratically elected president, gave him strong credibility as a transformational leader.

The picture with regards to claims based on performance and rational-legal justification is also clearly in line with our expectations. Closed autocracies, in particular, do not rely on these sorts of claims to a great extent, whereas electoral autocracies, with their emulation of democratic procedures, rely on them to a greater extent, but not as extensively as a democracy of either type (Ginsburg and Moustafa, Reference Ginsburg and Moustafa2008). The other aspect that is interesting with regard to electoral authoritarianism is that it combines all four claims in large measure. With regard to personalistic leader-based and ideological claims, it ranks below closed autocracies, yet its level of reliance on performance and rational-legal claims is also below the democracies it emulates to generate legitimacy (Schedler, Reference Schedler2009). In Appendix Figure 10, we show the relationship between the four legitimation claims and a continuous measure of democracy, V-Dem’s Electoral Democracy Index. The correlations reiterate the pattern of associations already visible in the previous boxplots, but also highlights that the four legitimation measures are not mere proxy measures of democracy. They carry additional information.

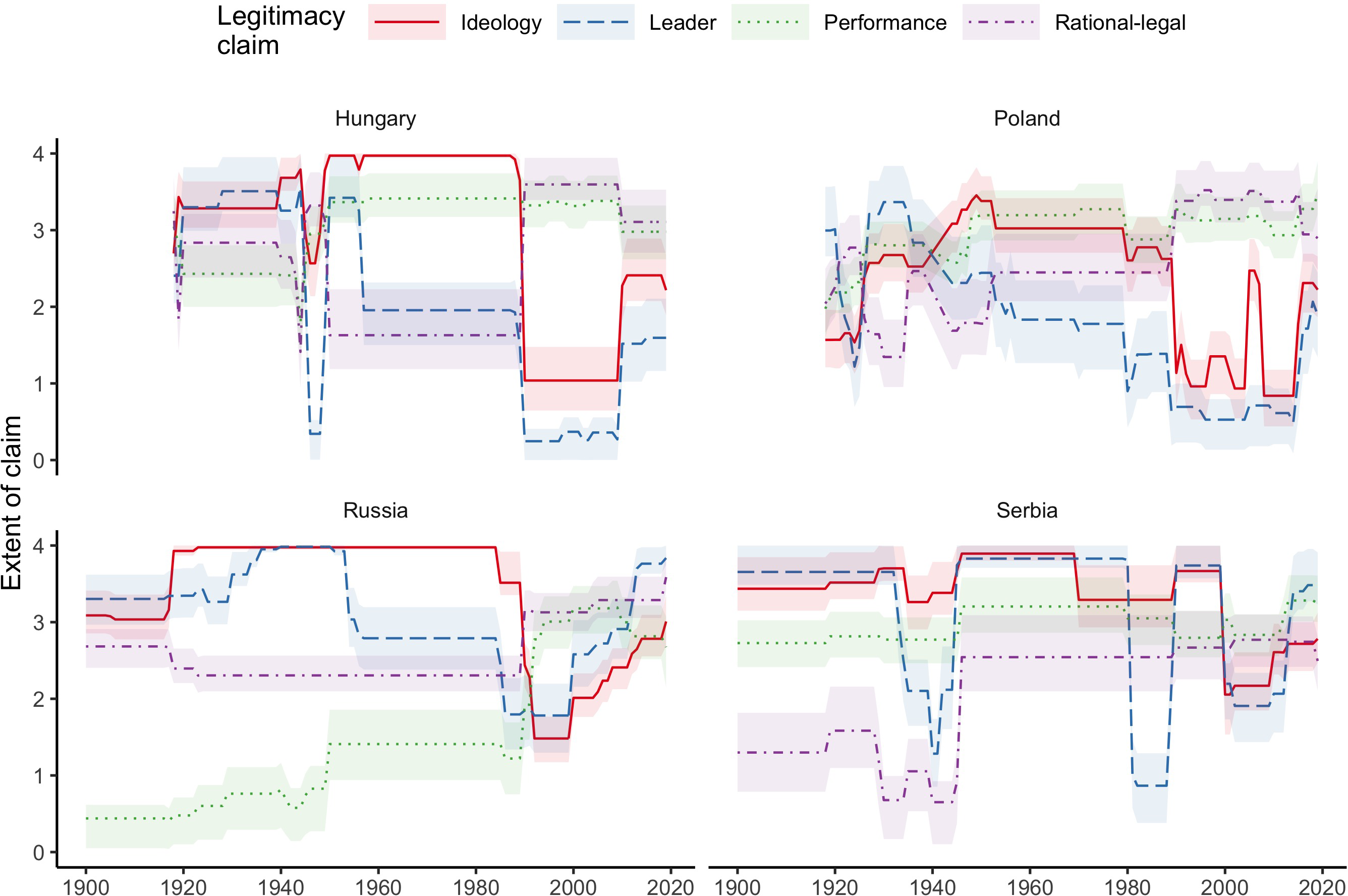

We also perform a second convergent validation exercise by posing a set of empirical expectations about different varieties of authoritarianism. In Figure 3, we compare the ways in which military, monarchic, one-party, and personalist autocracies seek to legitimize their rule. This categorization is drawn from the typology and coding proposed by Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014).Footnote 6 We expect one-party regimes to be most reliant on ideological claims. In terms of the role of the leader, we expect military regimes, which tend to be based on institutional identity, to be the least dependent on the qualities of the leader. With regard to performance claims, we expect monarchies, with their basis in tradition, to be less prone to rely on performance claims. Finally, we do not expect rational-legal claims to play the dominant role in the legitimation strategy of any form of authoritarian rule.

Figure 3. Distribution of claims by autocratic regime type.

As one would expect, dominant-party-based regimes (a high percentage of which are Leninist) rely on ideology to a larger extent than do other autocratic regimes. While there are some outliers, they do not cast doubt on what the aggregate shows. For instance, Ivory Coast under the rule of the Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire – African Democratic Rally (PDCI) from independence up until 1999 was not very ideological (Piccolino, Reference Piccolino2018: 502). Legitimation in this case was highly personalistic, based on the charisma of the leader of the independence struggle, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, who ruled until his death in 1993. His style of leadership was known as ‘Houphouetism’ and toward the end of his reign, his followers referred to him either as ‘Papa’ Houphouët or ‘The Old One’, cementing his reputation as the ‘father of the nation’ (Toungara, Reference Toungara1990).

Military regimes are less likely to make claims to rule on the basis of the qualities of the leader as the three other types. On average, monarchies rely on this claim to the greatest extent and with the most consistency, as demonstrated by the very low variance on the mean. We see a very similar pattern for personalist regimes as well. Governments in party-based regimes also make legitimacy claims on the qualities of the leader to a similar degree. This finding hinges on differences in the role of the leader over time in revolutionary one-party states. During revolutions, and periods of intense regime building that follows, charismatic leaders and their successors often play an instrumental role in the exercise of power. This is widespread in many Marxist–Leninist regimes (e.g. Lenin and Stalin in the Soviet Union, Mao in China, Castro in Cuba, or Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam). It is perhaps most pronounced in North Korea where three generations of the Kim Family have inaugurated a form of dynastic socialism. We also see this in the kind of Nationalist one-party rule that developed around independence leaders in postcolonial states (e.g. Nyerere in Tanzania, Kenyatta in Kenya, Yew in Singapore, Bourguiba in Tunisia, as well the case of Houphouët-Boigny discussed above).

With regard to performance legitimacy, monarchies rely on such claims to a lesser extent in line with our expectations. While personalistic dictatorship relies on such claims less than military or one-party rule, we were, at first, surprised that the levels between these three were similar. We believe that this makes sense because all three regimes pursue different kinds of goal-oriented agendas which can be justified and assessed in terms of performance criteria given the rationale of these distinct forms of rule. Personalistic regimes, because their rule relies upon the neo-patrimonial distribution of resources, delivering the goods to key constituencies is seen as a kind of performance on the basis of which legitimacy claims can be made. Such arguments make sense in the context of big-man patrimonial rule in Africa (Médard, Reference Médard1992; Bratton and van de Walle, Reference Bratton and Van de Walle1994; Erdmann and Engel, Reference Erdmann and Engel2007; Baldwin, Reference Baldwin2016). Military regimes often claim their right to rule based on the need to restore and physical security, which also qualifies as a potential criterion to frame performance-based legitimacy. And finally, one-party states are well-known for their commitments to developmentalist and welfarist goals, and give them great play in programs and in making appeals to their populations.

Assessing face validity

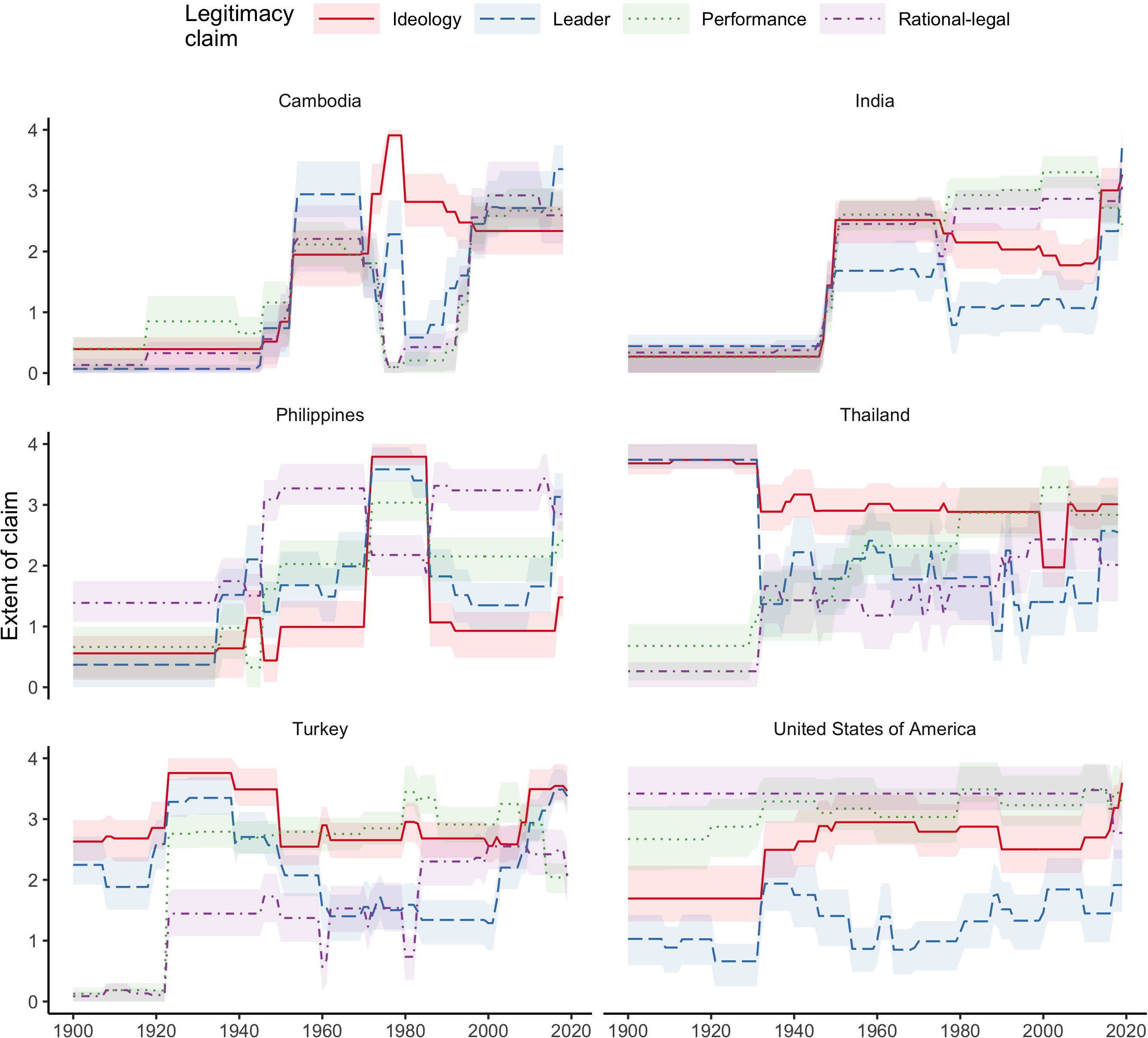

Our second exercise in validation concerns content or face validity. We use the case-based variant which concerns itself with whether the ‘indicator… sort(s) cases in a way that …fits conceptual expectations’ (Adcock and Collier, Reference Adcock and Collier2001: 539) by looking at individual countries over time to see if the values generated by the expert surveys are congruent with strongly held beliefs about the case. If we start by looking at legitimacy claims based on the personalistic characteristics of the ruler, the short, dotted blue line in Figure 4, we can clearly identify the rise of strongmen. In line with the recent literature on the personalization of the Cambodian regime (Morgenbesser, Reference Morgenbesser2018), the measure picks up Hun Sen’s ascension to the premiership in Cambodia in 1985 and notes a peak in person-based legitimation claims in 2018, when he audaciously commissioned a grand and ostentatious monument to himself (Nachemson, Reference Nachemson2018). We also see an uptick in India after the 2014 electoral success of Hindu-nationalist Narendra Modi and an even sharper rise in the Philippines after strongman Rodrigo Duterte was elected president. His vainglorious claims to legitimacy have begun to approach that of the previous, no-less-notorious egoist-in-chief of the island nation, Ferdinand Marcos (1965-86).

Figure 4. Rise of the strongmen.

In Thailand, we see a sharp rise in leader-based claims since the coup-mastermind General Prayuth Chan-o-cha assumed dictatorial power in 2014. In Turkey, we see a dramatic increase in personalistic legitimation claims since Recep Erdogan assumed the premiership in 2003. These increased even further after he became president in 2014. And even more striking, the intensity of claims based on Erdogan’s persona now surpasses those of the founder of the republic and its first president, Kemal Atatürk (in power 1923–38). In the US, we note a small, yet significant increase in claims based on the person of the leader since Trump’s inauguration in 2017.

In Figure 5, we see similar surges in personalist legitimacy claims in the two Central European EU members, Poland and Hungary that have experienced recent bouts of democratic backsliding. In Russia, the government has steadily elevated Putin’s persona and is approaching levels close to Stalin’s ‘cult of personality’. In Serbia, we note the dramatic fluctuation in claims based on the appeal of Josip Tito (in power 1953–80), Slobodan Milošević (in power 1989–97), and a rise again since after the Serbian Progressive Party’s Tomislav Nikolić won the presidency in 2012. The high level of personalist legitimacy claims has continued since Aleksandar Vučić assumed the presidency in 2017. In addition, we also observe an increase in legitimacy claims based on ideology, in particular nationalism, in all four countries.

Figure 5. European backsliders.

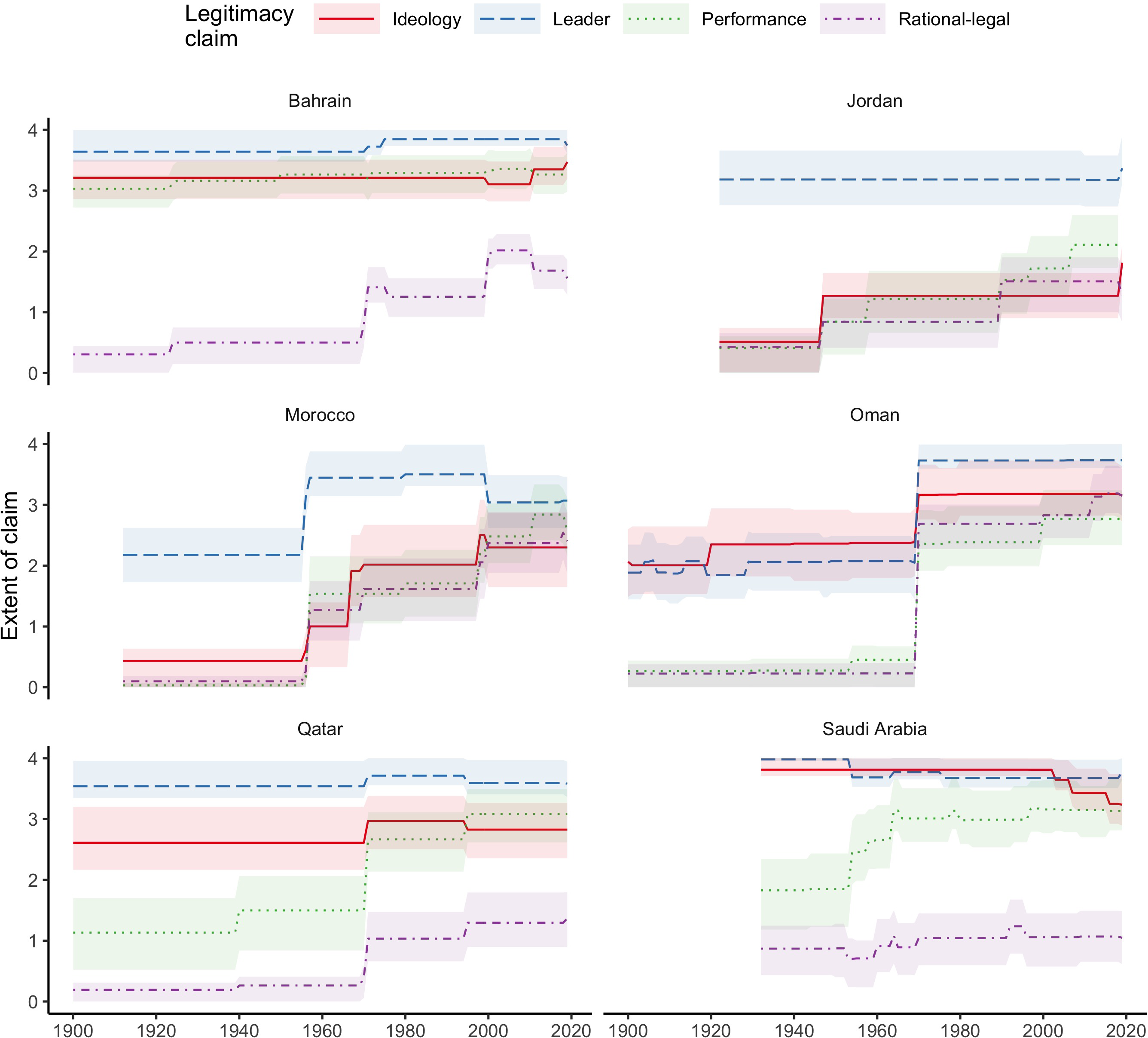

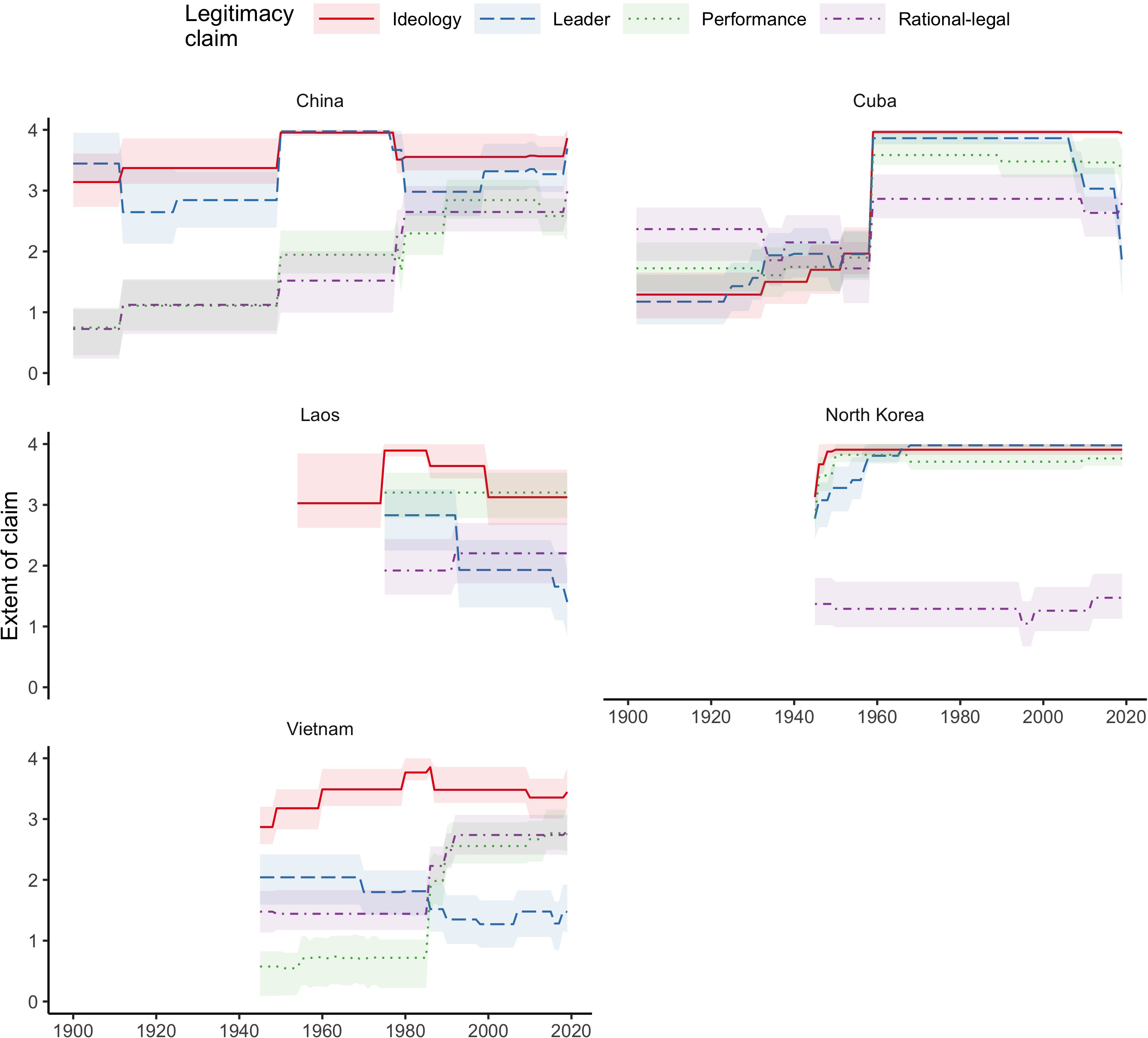

In line with expectations, the highest level of reliance on the person of the leader is seen in absolute monarchies, such as Bahrain, Jordan, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, and Oman (see Figure 6). Monarchy, by its nature, heavily relies on the person of the leader in staking its claim to the legitimacy of the regime. And as is evident from the North Korean timeline, see Figure 7, the score attains ridiculous heights in the context of the ‘socialism in one family’ practiced by the Kim dynasty.

Figure 6. Kingdoms promote the person of the leader.

Figure 7. Communist regimes.

The five remaining communist states in the world also all heavily rely on ideology to justify their rule (see Figure 7). In the case of Cuba, the drop-off at the end is a product of the retirement of a charismatic revolutionary leader, Fidel Castro, and the transfer of power to his brother Raul in 2011, and then again after Miguel Díaz-Canel assumed the presidency in 2018. Taken together the graphs in this section largely square with our expectations and offer us further confidence that expert coders can be employed to estimate legitimation claims over time.

Construct validation: populists and leader-based legitimation claims

One of the most convincing ways to persuade the research community that the effort spent on collecting a new indicator is to demonstrate its utility via an exercise in construct validation (sometimes also called nomological) that uses the new indicator to test a well-supported hypothesis (Adcock and Collier, Reference Adcock and Collier2001: 542). Based on the literature on populism, we will examine the pattern of change in leader-based legitimation strategies when countries elect populist governmentsFootnote 7, and thus test personalism as an essential characteristic of populism.

In much of the seminal work on populism, particularly that focused on Latin America and written in the 2000s, charismatic leaders are seen as a central to the phenomenon. Barr (Reference Barr2009: 40) emphasizes that populists tend to downplay the role of institutions such as political parties and parliaments and instead claim that he/she ‘embodies the will people the people’ (for similar arguments see Roberts (Reference Roberts2006) and Mainwaring (Reference Mainwaring2006)). Scholars such as Weyland (Reference Weyland2001: 13–14) point out that populist leaders need to create a particularly intense connection to their followers, because they do not build on strong party identification and institutionalization. Levitsky and Loxton (Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013) distinguish between populist rulers, who are typically political insiders who abandon established parties to make personalistic, anti-establishment appeals (e.g. Rafael Caldera and Fernando Collor) and anti-establishment outsiders, who emerge from social movements and maintain linkages that are more grass-roots oriented rather than personalistic (e.g. Evo Morales).

Given the strong consensus on personalistic leadership in large parts of the literature on populism, we should see an increase in personalist legitimation claims when populists are in power. We empirically test the construct validity of our measure of leader-based claims on the basis of a sample of Latin American and European countries, using a dichotomous variable of populists in power based on expert assessment (taken from Ruth-Lovell et al., Reference Ruth-Lovell, Lührmann and Grahn2019).Footnote 8

We start with a descriptive look at the leader-based legitimation strategies favored by populist governments in the last two or so decades. Do populist governments, on average, rely on different legitimation claims than non-populists? Figure 8 suggests they do: populist incumbents in Latin America and Europe typically rely on claims based on the person of the leader to a larger extent than do non-populists. The difference in means is substantially relevant (average difference of 1.14) and statistically significant (see Table 1 in the Appendix). At the same time, Figure 8 illustrates that the variance of the extent of leader-based legitimacy claims within the sample of populists is quite wide. The standard deviation is 1.45 times higher than in the sample of non-populists (which are concentrated on the low end of the scale).

Figure 8. Distribution of leader-based claims by populists and non-populists in Latin America and Europe (1995–2018).

We see that populist regimes are much more likely to make legitimation claims based on the character of the leader than the other regimes in the sample. While this is not universal, it suggests that those authors who see devotion to the leadership as central to populism have a point with regard to a substantial subset of populist governments. The connection of populist claims to the general will clearly in many cases finds embodiment in the charismatic leadership of leaders who issue claims of speaking in the name of the people.

Next, we examine if the relationship between populist government and personalistic legitimation claims holds in an OLS regression framework controlling for level of democracy, GDP per capita, a regional dummy variable for Latin America, and two-way fixed effects.Footnote 9 Figure 9, below shows the estimated coefficients of having a populist incumbent on the extent of relying on leader-based legitimation claims.

Figure 9. Estimated effect of populist incumbent on extent of leader-based legitimation claims in Latin America and Europe (1995–2018).

Having a populist incumbent is associated with a one-unit increase (on a five-point scale) to the extent that governments rely on the person of the leader to legitimate the regime. When we add control variables, country and year fixed effects, and a regional dummy variable for Latin America, the relationship holds though the magnitude of the effect is somewhat diminished (also see and Appendix, Table 5). This is well in line with the foundational literature on populism that has highlighted the centrality of charismatic leaders (e.g. Weyland (Reference Weyland2001), Mainwaring (Reference Mainwaring2006), and Levitsky and Loxton (Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013)).

To summarize, the exercise above shows the construct validity of our measure as, in line with expectations, the legitimation claims of populist governments are indeed more personalist in comparison to their competitors. Thus, we empirically demonstrate the centrality of the leader for the legitimation strategies of a large segment of populist governments.

Conclusion

This paper introduces the new Regime Legitimation Strategies (RLS) measure, which provides the first comprehensive measure of how governments justify their regime over a wide cross section of countries over a long period of time (183 countries over 120 years). We document how legitimation strategies are based on overlapping ideological, personalistic, performance-based, and rational-legal procedural claims. We also show how these claims vary across regimes and within countries over time.

We began by discussing the long history of the concept of legitimacy in political thought, but then we present our specific formulation of that concept focusing on the legitimacy claims of rulers emphasizing the analytic rather than the normative side of that discourse. We understand that this focuses on only one of the many important political aspects inherent in the broader discussion of legitimacy, but consciously do so because of the relative neglect of this important aspect of the concept and the opportunities to measure a concept of this nature using the methods of the Varieties of Democracy project. We outline how we operationalized our concept, and discuss the procedures that we used to generate scores for the indicators across a broad range of cases in temporal and geographic terms. We then performed a set of validation exercises, looking at the content, construct, and convergent validity of the measures.

Our tests provide strong evidence that experts are able to discriminate different degrees and modes of legitimation using the conceptual framework embedded in our questionnaire and can be employed to code legitimation claims. With very few exceptions, their coding squares well with expectations from thickly descriptive case studies as well as with existing regime typologies providing both convergent and face validity. In addition to capturing historical shifts, the measures pick up recent trends, such as an increased emphasis of the leader in countries such as Russia, Turkey, Cambodia, and more recently also in India and the Philippines, but also with recent increases in legitimation claims based on both conservative and nationalist ideologies in cases of democratic backsliding in Europe, such as Serbia, Hungary, and Poland.

Revisiting the focus in the populism literature on the role of personalism, we show that populist rulers in Europe and South America shift their legitimation strategies in more personalist directions than countries not ruled by populists. These findings are substantively important to the literature on populism. This justification of rule, so common to many anti-democratic movements in the past, should also serve to alert us to the anti-democratic threat of populism, something on which the contemporary literature on populism is sometimes ambiguous (Espejo, Reference Espejo, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Müller, Reference Müller, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Rummens, Reference Rummens, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Urbanati, Reference Urbanati, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017). Greater attention to the justificatory claims of populist movements for why they want to hold power would allow us to make substantive judgments about which claims are aimed at revitalizing democracy and which are interested in exploiting the current crisis of democracy to reconstruct power on an authoritarian basis.

It is our hope that this presentation and demonstration of new RLS measures convinces readers that it is a reliable tool that has the potential to open new avenues for cross-national research on the causes and consequences of divergent RLS. For the first time, scholars are able to systematically study what drives governments to change legitimation strategies and what effect such changes have on important regime outcomes such as regime stability, the nature of rule itself, and its consequences for those subject to it.

First, the RLS measures allow researchers to systematically assess the repercussions of legitimation shifts. For instance, a move away from claims embedded in rational-legal procedures in place toward leader-based and/or ideological claims may well constitute a warning signal for the erosion of democratic rights. Furthermore, a rapid shift of legitimation strategies might indicate that a regime’s stability is under threat.

Second, the RLS measures permit systematic examination of how particular legitimation strategies – governmental claims focusing on performance, processes, the person of the leader, and ideology – relate to other elements of rule most notably state repression, co-optation, and the provision of public goods (Gerschewski, Reference Gerschewski2013). This would allow researchers to shed new light on the nature of rule and the relationship between rulers and the ruled in different contexts. This would be particularly welcome for better understanding of the novel forms of authoritarianism that have arisen in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. We have provided insights on how specific legitimation strategies relate to established regime types. Scholars can furthermore use these legitimation strategies to construct and test refined regime typologies (Kailitz, Reference Kailitz2013).

Finally, the relationship between different legitimation strategies and the acceptance of these claims by elites and the general population can open a new important line of systematic analysis of legitimation (von Soest and Grauvogel, Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017). In the future, researchers may be able to pair the RLS data with representative surveys on citizen attitudes or event data on contentious behavior. Thus, the RLS measures are relevant, that is at minimum for scholars of democratic and autocratic politics, regime survival and stability, nationalism, and regime change.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000363.

Acknowledgments

For their helpful comments, we thank Anja Neundorf, participants in the 2019 V-Dem conference, and three anonymous reviewers. This project was supported by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (Grant M13-0559:1, PI: Staffan I. Lindberg); the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (Grant 2013.0166, PI: Staffan I. Lindberg); the European Research Council (Grant 724191, PI: Staffan I. Lindberg); and internal grants from the University of Gothenburg.