1 Introduction

Global governance today relies explicitly on business action to mobilise a transition to a sustainable world, which has long been understood as meaning an environmentally safe and socially just world. The Brundtland Report,Footnote 1 a canonical text in sustainability policy, states: ‘Sustainable development aims to promote harmony among human beings and between humanity and nature’. Footnote 2 Its call for ‘action on the part of individuals, voluntary organizations, businesses, institutes, and governments’, established a mandate for science–business–policy interfaces for sustainable development, initially with a local impetus.Footnote 3

Our concern, in this decade of action for global sustainable development goals,Footnote 4 is that some science–business–policy interactions that are dominating current regulatory debates about corporate sustainability can, paradoxically, undermine the potential for transformations to sustainability. Our aim is to scrutinise these debates, identify tensions and emergent risks that they present to sustainability, and suggest approaches that are more broadly grounded in sustainability research on multiple levels.

We concentrate on three actor groups in their interconnected roles. The global change science community occupies an influential position in diagnosing unsustainability and informing global sustainability goal-setting, notably through articulations of what constitutes a ‘safe and just operating space’. The challenges of translating scientific insights to policy-relevant messages are far from new to sustainability research,Footnote 5 but they are heightened in today’s global-scale transdisciplinary interfaces. Business, by which we mean the organisation of commercial activity in all its varieties, is explicitly highlighted in global sustainability policymaking as a vitally important actor. Corporations with global reach often get particular science and policy attention,Footnote 6 but also activities of ‘local’ business are globalised through trade and information networks and value webs. The European Union (EU), as a non-state policymaker, self-presents and is regarded as ‘leading’ on business and sustainability. It emphasises the importance of ‘undeniable scientific evidence’ in guiding its work.Footnote 7 The EU has unprecedented regulatory ability and power compared to both nation states and international law regimes. The EU is actively engaging in Earth system governance, which can broadly be understood as the setting of environmental policy in the context of anthropogenic Earth system change.Footnote 8 For example, the European Commission’s 8th Environment Action Programme to 2030 includes the explicit framing of living ‘within planetary boundaries’.Footnote 9

Interactions between these three influential global actors shape current understandings, practices and regulation of ‘sustainable business’. We are seeing a tendency for problematic transfers of concepts between different domains of scholarship (notably, between a particular branch of physical Earth science and other natural and social sciences) and from academic to action contexts. Accordingly, we see a need to scrutinise these developments critically. When critical scrutiny is lacking, oversimplified understandings can be deployed for deflecting attention and delaying action.

For our interdisciplinary critique, we combine an Earth system science perspective on global environmental change with a sustainability law perspective on regulation and governance of business. In bringing together environmental science, social and legal studies and real-life context into a broader conversation on sustainable business, we need to be clear about the basics within each contributory domain. Our starting premise is that setting the scope of sustainability must draw meaningfully on much more broadly based sustainability research than is actually happening now. In Section 2, we outline our research-based understanding of sustainability as a safe and just space for humanity. We observe with concern a trend where important research-based insights are simplified into blunt ‘science-based’ targets and prescriptive recommendations, informed by overly narrow segments of global change science and sustainability scholarship. We also discuss how fundamental aspects of sustainability are recognised in international laws and policies, yet are not sufficiently emphasised, prioritised and implemented, often leaving sustainability as future-oriented aspirations.

In Section 3 we turn to what a safe and just space means for business. We introduce a research-based understanding of corporate sustainability. In our analysis, we focus on the science-business interface, and discuss two key concepts in the discourses on governance and regulation of business for sustainability: sustainable value creation, and what often paradoxically are denoted sustainability risks.

In Section 4, we concentrate on regulatory policy for sustainable business. Viewing the EU as a global actor, we outline how the EU interacts with globalised business and the global change science community, revealing tensions in the discourses and deployments of narrowly defined ‘science-based’ approaches to sustainability. We show, through an illustrative analysis of a representative selection of law and policy initiatives since the financial crisis of 2007–2008, how the EU is increasingly aware of the need for regulating business and finance for sustainability, and how its initiatives are informed and constrained by specific business-science interactions.

Section 5 gives our concluding reflections. Placing particular attention on the role of sustainability scholarship, we sketch our recommendations for navigating science–business–policy interactions and invite further interdisciplinary debates.

2 What is sustainability science saying?

A. Conceptualising sustainability as a safe and just space for humanity

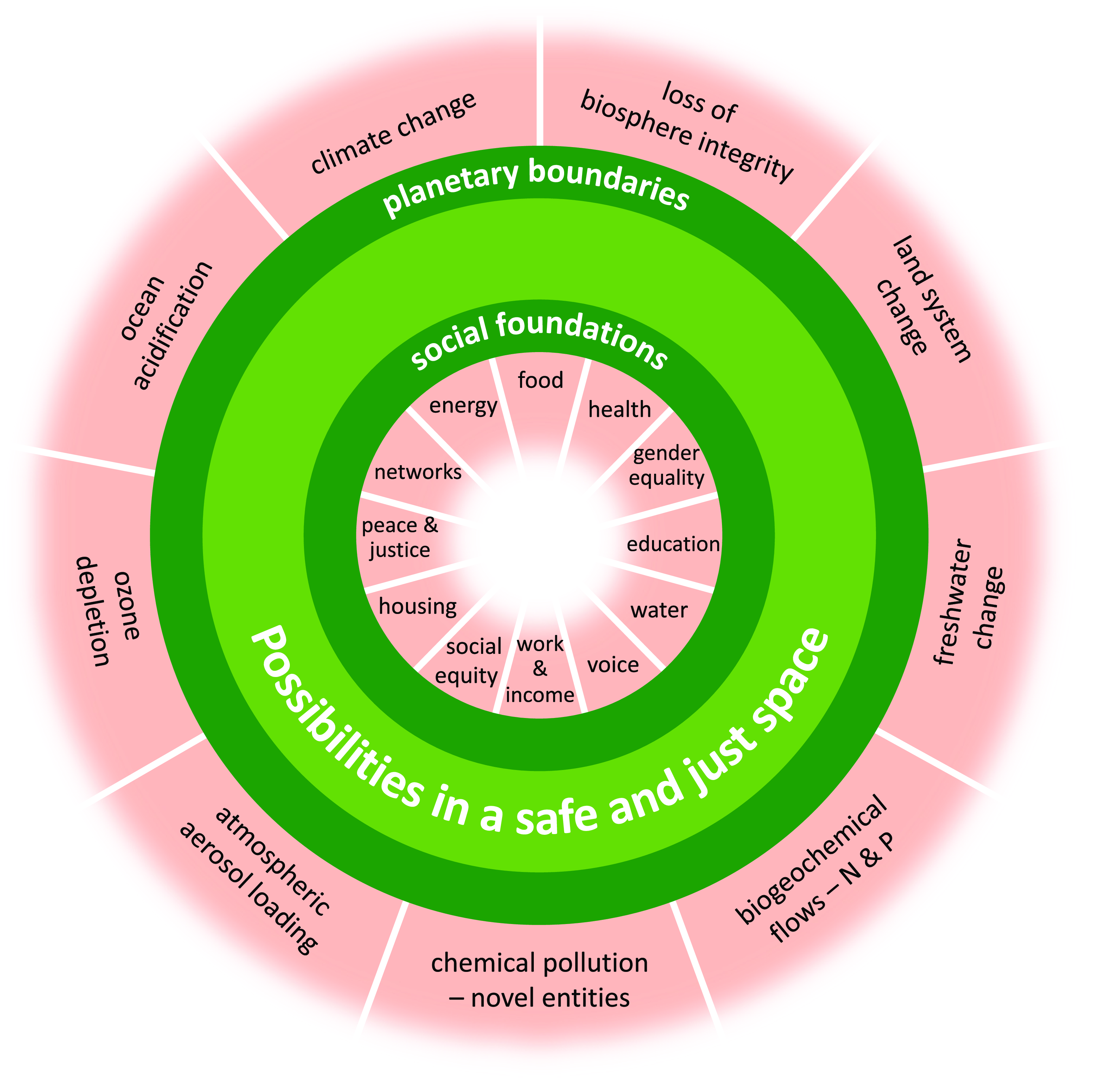

As societal concerns about global changes grow, so too have interdisciplinary efforts to provide global-scale perspectives on sustainability.Footnote 10 For over a decade, we have worked with the planetary boundaries framework,Footnote 11 an influential initiativeFootnote 12 that diagnoses the world’s departure from a biophysically characterised ‘safe operating space for humanity’. Threats have long been recognised to both the ‘inner limits’ of basic human needs and the ‘outer limits’ of the planet’s environmental integrity.Footnote 13 RaworthFootnote 14 coined the ‘safe and just space’, demonstrating today’s severe sustainability shortfalls by combining planetary boundaries with social foundations based on internationally agreed minimum social requirements. Raworth’s inclusion of social foundations also permits a diagnostic analysis of key aspects of unsustainability. This visually simple yet conceptually powerful approach characterises an environmentally safe and socially just space where societies can seek opportunities to thrive (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A safe and just space for humanity entails mitigating pressures on biophysical planetary boundaries and securing social foundations. The greater the departure from this space (shown as red shading), the greater the risks and harms of unsustainability. Adapted from Raworth (2017), Leach et al (2013).

We work with this safe and just framework for sustainability for several reasons. It is highly salient to today’s agendas, helping its users hold the world’s most pressing interdependent sustainability challenges in mind at the same time. Its global perspective complements existing local and sectoral approaches for sustainability assessment and action. Its biophysical and social dimensions are underpinned with multidisciplinary research and worldwide data,Footnote 15 conferring scientific credibility and political legitimacy, and pointing decision-makers to a robust evidence base that can support sustainability action across geographic scales and governance levels. And there is now considerable experience in translating this framework into action contexts.Footnote 16

However, recent academic publications reveal interpretive flexibility about ‘planetary boundaries’,Footnote 17 which unfortunately aggravates fuzzy conceptualisations and mixed messages even within contributory research.Footnote 18 We are concerned that in these publications, an uncritically teleological interpretation is being imposed on the diagnostic framework. We see serious risks arising when the framework’s individual boundaries are treated as planet-management goals. Powerful and influential initiatives, such as the self-styled Global Commons AllianceFootnote 19 discussed further below, are promoting the use of this small set of quantified indicators of global change, in ways that become disconnected from the systemic understanding provided by the underpinning science and the reflexive practices of sustainability research. So we must first set out here the basic premises informing our inter- and transdisciplinary use of this concept.

Earth system science underpins the planetary boundaries framework, conferring it with considerable authority.Footnote 20 Earth system analysis characterises the interconnections of life and its physical and geochemical environment – the ‘workings’ of planet Earth, which here we term biophysical processes. These interactions shape planetary flows of matter and energy (manifest as climate), which in turn shape conditions for life (termed biosphere integrity in the framework).Footnote 21 The variability of Earth’s behaviour arises from combinations of the internal dynamics (‘feedbacks’) and driving forces from outside the coupled climate-life system (‘forcings’), such as major volcanic eruptions, changes in Earth’s positioning relative to the sun – and the anthropogenic introduction of fossil-fuelled greenhouse gases. The stability of Earth’s climate and ecosystems is fundamentally governed by physical and chemical properties of land, water, ice and the atmosphere, and by the capacity of living organisms to exploit, respond and adapt to those conditions. A key insight from the field of resilience science is that Earth’s stability is a dynamic outcome of the behaviour of complex adaptive living systemsFootnote 22 – and that the resilience of Earth’s ecosystems, of which human beings are part, can be eroded to the point of destabilisation and abrupt reorganisation.Footnote 23 Thus, planetary boundaries are not static limits, carrying capacities, or resource constraint or allocation budgets, although they are often viewed interchangeably with these precedent conceptsFootnote 24; and their tools and metrics are often used in operationalisation of the planetary boundaries framework.Footnote 25

It can work as a scientifically coherent framework because the comparatively stable conditions of the ∼12,000-year Holocene epoch provide a well-characterised conceptual baseline for the set of processes included in the framework.Footnote 26 While Earth’s environment has varied greatly over geological time, it is mainly in the Holocene that human societies established themselves worldwide, hence the normative judgement that planetary boundaries together demarcate a ‘safe’ space for humanity. Evidence of the variability of Earth’s behaviour from deeper geological time provides additional understanding of the possible pace, abruptness and interconnectivity of large-scale Earth system changes.Footnote 27 Today, the nine human-driven global change processes are shifting the world away from both biophysical stability and scientific predictability (Table 1). The framework’s ‘core boundaries’, climate change and biodiversity loss, characterise Earth’s epochal climatic and ecological conditions; breaching these boundaries irreversibly alters the trajectory of Earth system dynamics.Footnote 28 The other processes in the framework capture the most consequential aspects of natural resource use and the synthesis and mobilisation of pollutants. Major changes in any one process cascade through the others, altering biophysical feedbacks and affecting how ecosystems reconfigure themselves to adapt to climate conditions.Footnote 29

Table 1. Trends and status of the nine human-changed global biophysical processes in the planetary boundaries frameworkFootnote 32

Summary overview of assessments by Steffen et al 2015, Persson et al 2022, Wang-Erlandsson et al 2022, and Richardson et al 2023. Six planetary boundaries are assessed as overstepped and severe impacts are already well documented. Trends are currently worsening for most of the boundaries. The boundaries are defined against a relatively stable long-term global baseline of Holocene conditions (represented as green shading). Predictability decreases and risks to society rise as the world oversteps these boundaries and departs from resilient and well-characterised Earth system conditions (intensifying red shading). International law recognizes all the processes as issues requiring large-scale and multilateral responses; indicative examples are given in the last column.

The planetary boundaries framework’s relevance to sustainability decision-making is its clear message that societal risks rise when biophysical boundaries are breached – as most already are. Perturbing multiple processes intensifies systemic shifts from well-characterised conditions to increasingly turbulent, poorly predictable dynamics.Footnote 30 The greater (and faster) the human-caused disruptions, the more likely that hazards will materialise not only locally but also elsewhere in the globalised system,Footnote 31 aggravating and perhaps perpetuating structural, socioeconomic and intergenerational injustice.

In this dynamic and interconnected context, sustainability involves dealing justly with today’s unsafe conditions, and dealing safely with unjust conditions. A ‘safe and just space’ is not a natural biophysical state of the planet which merely needs to be quantified and managed. Nor is it a social condition that can be achieved through scientifically optimised planetary allocation of resources, risks and benefits. And in this context, we are concerned at the ways that particularly reductive strands of physical environmental science are encroaching into the territory of justice scholarship. For example, the coalitions of global change science networks, wealthy philanthropists, strategic sustainability think tanks and campaign organisations, and business actors making up the ‘Global Commons Alliance’ are defining, promoting and creating tracking systems for a particular set of social and technological ‘key transformations’. Key components in this constellation are the so-called ‘Earth Commission’ selected from self-nominees in the international global change science community to ‘define limits’ for ‘shared resources that are essential for a habitable planet’Footnote 33; and the ‘Science-Based Targets Network’,Footnote 34 which is modelled on the highly influential Science-Based Targets InitiativeFootnote 35 for setting and disclosing corporate climate targets, with several actors and organisations in common. For full disclosure, one of us (Cornell) has been involved in earlier phases of these initiatives, opting to end that involvement because of growing misalignment with her own long-standing commitments to transdisciplinary critique and integrative methodology across natural and social sciences.Footnote 36

The situation today is that a very small subset of scientists assesses what is ‘safe’, honing in on climate target-setting to reduce carbon emissions. In turn, this informs the prevailing understanding of sustainability risks, which explains why so many aspects of today’s extreme unsustainabilities are not recognised.Footnote 37 The dominant climate-centric emphasis has direct implications for policy,Footnote 38 with the science–business–policy interface presenting ‘science-based’ solutions that are paradoxically counterproductive, as we discuss below.

These initiatives are also disregarding social research insights. Just as most biophysical planetary boundaries are overstepped, there are shortfalls on most social dimensions – which also both reflect and present unsafe and unjust conditions for many people, despite internationally agreed sustainability priorities. Raworth’s inclusion of social foundations in the safe and just frameworkFootnote 39 are underpinned with consensus in UN deliberations and adoption of Sustainable Development Goals,Footnote 40 conferring political and societal legitimacy to the framework. They are also supported in international law including human rights, labour, taxation and anti-corruption law, albeit to varying and consistently insufficient extents.Footnote 41

Safeguarding and sustaining a safe and just space require continual negotiation and intentional transitions, informed by research and real-world knowledge about the interconnected complexities of Earth’s social-ecological systems. We argue that the proper role of global sustainability science is less about imposing static, simplistic ‘science-based’ metrics with tenuous links to the establishment of stable future conditions (because complex Earth system changes cannot simply be reversed) and more about exposing ‘questions of justice and inequality relating to global patterns of consumption and production, resource allocation, benefit distribution, and so on’.Footnote 42

B. An expanded research base for the ‘safe and just space’ is needed

Globally coordinated environmental change science has long been an influential actor in international law that responds to the biophysical issues flagged in the planetary boundaries’ framework, as evidenced in the multilateral environmental agreement examples shown in Table 1. Recent agreements include the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework to guide action to 2030 for implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the UN High Seas Treaty extending the protection of marine nature. Ongoing developments include negotiations for a UN Plastics Treaty. All explicitly emphasise the role of science, continuing what some scholars regard as a shift from instrumental ‘science in action’ to ‘science for action’.Footnote 43

Despite this emphasis, the international law framework has major gaps between scientific issue-recognition and actual action to mitigate environmental changes and reduce associated risks. For some issues, these are law and policy gaps. For example, for nitrogen and phosphorus flows, the global problem is only partially covered by regional agreementsFootnote 44 and sectoral instruments deal piecemeal with different environmental compartments (eg, air quality, wastewater management, agriculture and spatial planning). More often, the challenge is an implementation gap. For climate change, biodiversity loss and chemical pollution, global-scale multilateral agreements are in place, with well-specified and scientifically informed objectives, precisely defined targets and quantified metrics (Table 1). And yet there is a lack of legal bindingness and persistent enforcement failures, so problematic trendlines continue and agreed policy goals are repeatedly deferred or redefined.Footnote 45

The strong influence of (environmental) science in global environmental law may be contrasted to international law’s governance of social foundations, where there is no similarly powerful global coordination of academic actors. Human rights law and international labour law are (historically) more informed by civil society than by the scholarly community.Footnote 46 Raworth emphasises that the minimum requirement for securing social foundations in the safe and just operating space entails ensuring the realisation of basic human rights,Footnote 47 as set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.Footnote 48 According to Samuel Moyn, this milestone document ‘did more than simply enshrine the ideal of distributive sufficiency that the declaration explicitly defined in its series of basic entitlements; it also reflected the ambitious political enterprise of distributive equality’. Footnote 49 However, distributive equality is not widely implemented as an intrinsic element of social justice, and socio-economic rights have remained in the shadow of civil and political rights. Raworth’s work may thus be seen as a criticism of the human rights movement.Footnote 50 Social justice concerns are also entwined with ecological dimensions.Footnote 51 This calls for an analysis that addresses the ‘causally interdependent structural causes of socio-ecological justice globally’, and that is ‘more inclusive and attentive, refusing to shut out complexities and connections that might otherwise go unaccounted for’.Footnote 52

Research-based responses to the sustainability challenge involve understanding that we, the peoples of the world, are all vulnerable to global changes but not all equally exposed nor equally resilient. Risks and opportunities alike are in flux, and they cannot be steered through simplistic global-level quantifications.Footnote 53 Achieving sustainability ‘requires exploration of and debate about which combinations of pathways to pursue at different scales’, in a process that needs to be ‘as open and inclusive as possible, giving voice to the knowledge, values and priorities of women and men who are marginalised, so that they are able to challenge powerful groups and interests’.Footnote 54 As Oomen, Hoffman and Hajer discuss, the politics of the future indeed depend on whose imagined futures are constituted in the forums that matter.Footnote 55

C. Global sustainability goals fall short of a research-based understanding of sustainability

International law has not managed to establish a global regulatory framework to achieve a safe and just space, yet international policy support for sustainability is clear and other kinds of regulatory initiatives, broadly understood, are being employed. Key amongst these is the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which can be seen as giving ways to structure coordinated international responses to the global risks of unsustainability.

The 2030 Agenda opens with a clear statement that aligns with mitigating biophysical pressures and securing social foundations of the safe and just space:

We resolve, between now and 2030, to end poverty and hunger everywhere; to combat inequalities within and among countries; to build peaceful, just and inclusive societies; to protect human rights and promote gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls; and to ensure the lasting protection of the planet and its natural resources.Footnote 56

The SDGs may be perceived as a useful starting point for businesses wanting to assess risks and impacts of their activities, but despite the 2030 Agenda’s assertion that its Goals are ‘integrated and indivisible’,Footnote 57 it is very unclear about the connections between goals (both in the texts and the targets; thus both in the spirit and substance of the SDGs). Treating the SDGs as a sustainability checklist presents problematic trade-off situations,Footnote 58 where a short-term focus means risks of continued unsustainability remain high.

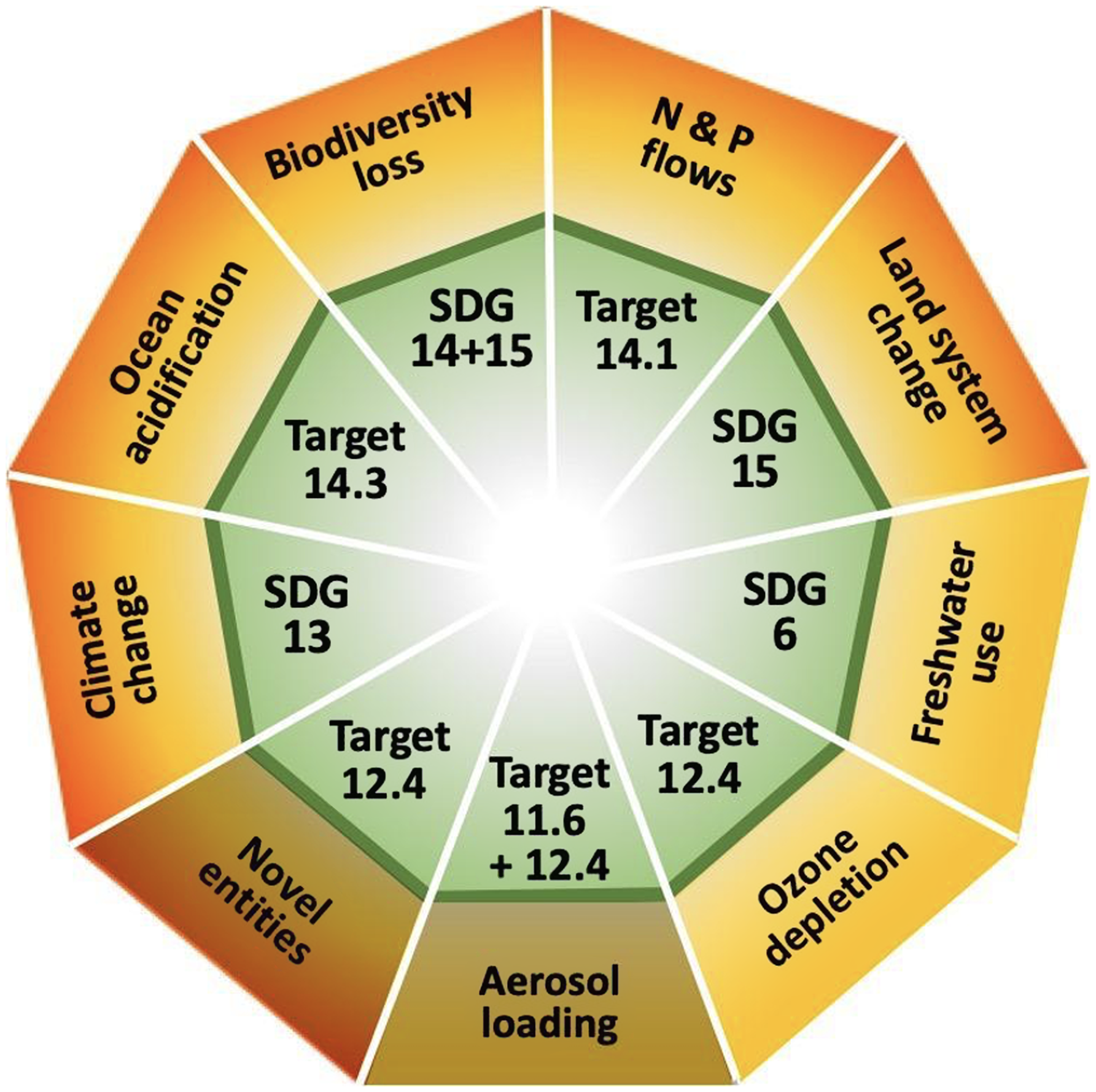

The SDGs encompass all biophysical issues highlighted in the planetary boundaries framework, to some extent (Figure 2). SDGs 13, 14 and 15 tackle climate change and biodiversity loss. Water is the focus of SDG6, and several SDG targets relate directly to other biophysical processes. Similarly, the economic goals SDG 8 and SDG 12 acknowledge the importance of maintaining Earth’s natural resources and avoiding environmental degradation, creating strong interdependencies with SDGs 6, 13, 14 and 15. However, the SDGs fall short of responding sufficiently to these planetary pressures. A fragmentary approach to achieving the desired near-term gains could undermine long-term ecological resilience.Footnote 59 Because the 2030 Agenda does not recognize that continued stable functioning of the living environment forms the basis for achievement of all other goals, the economic SDGs do not acknowledge any constraints on Earth’s regenerative capacity. For instance, SDG 8 leaves the decoupling of economic growth from environmental degradation as an aspiration for countries’ endeavours, and it assumes that such decoupling is indeed globally possible.

Figure 2. The 2030 Agenda addresses all nine environmental priorities in the planetary boundaries’ framework. Climate change, biodiversity loss, land systems and water used are the focus of Goals. The other processes are included in Targets under other goals. (Figure: Sarah Cornell).

The social aspects of the SDGs inform the selection of social foundations in the safe and just framework and yet they are insufficient. Implementing the social targets of Agenda 2030 requires going beyond some international treaty obligations, while other international obligations are not adequately encompassed by the SDGs. Notably, operating in a safe and just space should be interpreted as including wider international obligations towards Indigenous Peoples, with their concomitant environmental relations.Footnote 60

In this regulatory space, where states and international institutions have not been able to achieve overarching sustainability goals, the science–business–policy interface has become very important. However, several interlinked problems arise.

While science has informed conceptualisation and contributes importantly to the basis for governing towards global sustainability, a very narrow segment of science dominates today’s discussions of how to facilitate sustainable business.

Political choices made at the global level take the world’s societies along different development pathways, raising challenging questions about the transparency, accountability and legitimacy of decisions and institutions – at all levels. Setting global goals and limits necessarily involves consideration of allocation principles and implementation options.Footnote 61 In prominent science-business interactions, these political aspects tend to be bypassed through the quantitative emphasis that prioritises (quantifiable) physical climate and a technologically enabled pathway to a decarbonised future. When ways forward are conceptualised from a biophysically narrow and socially universalising perspective, the diversity of perspectives and opportunities is suppressed, and there is a danger that the most marginalised and vulnerable groups remain insufficiently included in decision-making processes.Footnote 62

3. What is business up to?

A. A ‘safe and just’ understanding of corporate sustainability

‘Corporate sustainability’ is a term that is intended to encompass the contribution of business to sustainability.Footnote 63 Our conceptualisation of corporate sustainability for a safe and just world embeds these core elements: business that supports the long-term environmental resilience of Earth’s ecosystems, on which humanity and all other living beings depend, and that secures the economic, governance and social bases of good lives for people and of well-functioning societies. This stands in stark contrast to the dominant so-called ‘weak’ understanding of corporate sustainability, where economic value, social welfare and the natural environment are seen as substitutable.Footnote 64 It also contrasts starkly with today’s aggregate reality of business as usual, which is contributing to environmental destruction, the exploitation of people and the undermining of the economic and governance bases for well-functioning societies.

This ‘safe and just’ understanding of corporate sustainability is the basis for our engagement with two key concepts in the discourses on governance and regulation of business for sustainability. We first discuss sustainable value, an emerging concept in the influential area of corporate governance. It is connected to and can be seen as the positive flipside of the second key concept that we discuss further below: sustainability risks.

B. The insufficiency of ‘sustainable value creation’

Why is business in aggregate still contributing to the extreme unsustainabilities of our time? Multijurisdictional comparative company law analyses show that business is part of a market-driven, financialised system that prioritises near-term maximisation of returns to investors. The social norm of shareholder primacy, a short form for the complex mix of market signals and economic incentives prioritising shareholder interests in value creation, is a main barrier to more sustainable business.Footnote 65 It constrains the possibility for the board and by extension senior executive management to shift businesses onto more sustainable paths. Competing social norms, such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct of 1976, and the UN Guiding Principles of Business and Human Rights of 2011, have so far been insufficient to fundamentally shift these unsustainable dynamics,Footnote 66 although there are interesting regulatory developments, which we discuss in Section 4.B.

Perceptions of the role of business in society are changing, presenting possibilities for ensuring that business contributes to the transformation to sustainability. Indicative of this change is the emerging concept of sustainable value creation. Recent reforms of corporate governance codes in Europe have included this terminology, possibly signalling a shift away from the focus on shareholder primacy, which many of the codes have been informed by and supported. However, the treatment in the codes of sustainable value creation is relatively superficial, and still constrained by shareholder-primacy ways of thinking.Footnote 67 Also, there is no academic consensus on the definition of sustainable value, and the concept is poorly understood in management theory.Footnote 68

In this landscape, the risk is that the ubiquitous references by business to ‘sustainable value’Footnote 69 are without any meaningful basis, let alone a research-based understanding of sustainability. This allows businesses to claim that they are creating sustainable value (whether by using the terminology or through other forms of ‘green claims’) while continuing with unsustainable business as usual.Footnote 70 Business attempts to set or narrow down the defining terms of ‘sustainable value’, for instance, by concentrating mainly on climate action,Footnote 71 increase the risk that the concept becomes a hollow term or a device for deflecting attention from continued unsustainable practices.

In contrast, positioning sustainable value creation within a research-based concept of sustainability opens up space for wider societal discussion about what sustainable business entails, and it could give corporate decision-makers a new mandate and a firmer regulatory framework for sustainable corporate governance.

We see sustainable value creation as a dynamic concept: it is the process by which business can operationalise corporate sustainability. Our starting point is accordingly that sustainable value entails economic value for business and for society that is created in ways that are sustainable. For us, this means contributing to ensuring the resilience of the planetary ecosystems of which humanity is part and to securing social foundations. Every element of this starting point calls for elaboration and discussions of key concepts such as ‘value’.Footnote 72 However, our intention in the short elaborations below is to contrast with ‘business as usual’ and to inform our further analysis.

Translated into the governance of business, contributing to long-term environmental resilience entails recognising the existence and complexity of ecological limits. It entails seeking to respond adaptively to changing hazards and working to mitigate pressures on planetary boundaries, as far as relevant and possible, depending on the sector, the size of the business and the possibilities for coordinated efforts. Sustainable value creation entails moving towards more sustainable, more circular models.Footnote 73 Yet business as usual is based on a competitive race to extract as much economic value from ‘natural resources’ as possible, thus ‘externalising’ the resulting harms of depletion of the same ‘resources’, pollution, ecosystem destruction and the changing of Earth’s climate, and undermining the ecological basis for a safe and just space. The impacts of today’s unsustainable linear business models are often displaced to communities far away.

Contributing to securing social foundations encompasses ensuring fair treatment, a ‘living wage’ and safe working conditions of employees as well as of workers and local communities across global value chains. Respect for international human rights and core conventions of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) is a minimum. Business governance for sustainable value creation includes open and inclusive participatory processes, resisting the ‘commodification of labour by seeking to revitalise the voice of everyone, regardless of the types of work they do or how they are hired’.Footnote 74 This is as relevant for workers employed by large businesses as it is for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). It is also in stark contrast with how business in aggregate currently operates. Extreme exploitation of people working in slavery-like conditions is a business norm, both within Europe and across the global value chains of European businesses. Business as usual is also complicit in the connection between environmental destruction and exploitation of people,Footnote 75 where Indigenous Peoples and (other) local communities are particularly vulnerable to being ‘invisibilised’ workers.Footnote 76

Sustainable value creation contributes to the economic basis of the societies in which the business interacts and precludes so-called aggressive tax planning and outright evasion.Footnote 77 Further, creating sustainable value entails support for democratic political processes,Footnote 78 including those that change the regulatory framework for businesses. This requires a shift away from business as usual, where intensive corporate lobbying and various forms of corporate capture of regulatory processes currently delay and derail transformation towards sustainability (we discuss examples in Section 4.B).

This transformation will in turn require more than the improvements in resource-efficiency and recyclability promoted in current approaches to circular economy business models, and more than the (at best) minimalist ‘do no harm’ respect for human rights of current sustainable corporate governance initiatives. Ultimately, we envisage sustainable value creation as a shift away from the current competition-driven ‘winner takes it all’ business mentality with infinite growth as a goal and a trail of harmful externalities in its path, to value creation that is based on socially and ecologically situated cooperation and coevolution.

C. Sustainability risks fall short of capturing the hazards of continued unsustainabilities

Business depends critically on the continued resilience of the world’s societies and Earth’s living systems, yet business today continues putting the global environment under increasing pressure; and the consequences of ignoring biophysical constraints and societal impacts are increasingly clear.Footnote 79 History gives plenty of warning signals about what it means for societies to operate outside of safe environmental conditionsFootnote 80: ideas of fairness and justice are challenged profoundly in disruptive shifts to alternative social configurations. Although awareness of the financial and corporate risks of continued unsustainability has begun to inform business and policy, we see severely problematic aspects in current approaches.

The recognition of financial risks of climate change is shaping the emerging discourse and approaches, as we return to below. Yet, the simplifying assumptions used to characterise and manage these risks can themselves present problematic hazards. They embody a representation of the world as quantifiable, predictable and to some degree optimizable. Today’s global change science and technology, such as Earth observations from space, can increasingly detect and attribute human-caused climatic and ecological changes even as they happen.Footnote 81 However, because of the interdependence of social and ecological systems, biophysical science alone cannot make a complete evaluation of the risksFootnote 82 or the responsibilities.Footnote 83 The systemic risks associated with Anthropocene changes,Footnote 84 cannot be adequately captured in a single global physical metric like a carbon budget, nor as an aggregate economic valuation expressed in euros, dollars or any other currency. Scientific understanding of complex Earth system dynamics makes clear that the future consequences of human-driven environmental changes cannot be precisely predicted.

Also, global environmental risks are too often presented as an abstract dehumanised problem rather than as human-caused problems that can actually be mitigated or halted through business action. And when the human causes are acknowledged, it is too often in terms of a globally undifferentiated ‘humanity’ that obscures systematic and structural issues of injustice linked to exploitative and neocolonialist corporate behaviours. The actual intertwined social and ecological consequences frequently are not considered at all, but instead are either regarded as external to business or are simply taken to be subsumed within financial risks to the business.

Indeed, until recently, most efforts for global environmental governance were framed in terms of national responsibility, concentrating on state actors.Footnote 85 Now, the global heterogeneity of environmental impacts increasingly motivates scientific and political efforts to more precisely place responsibility on the range of actors who cause them.Footnote 86

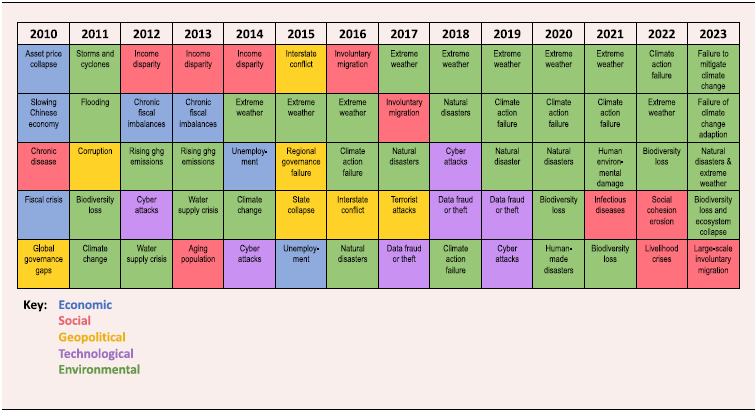

The World Economic Forum’s series of Global Risks Reports document the business world’s growing concern about environmental risks (Table 2). However, this does not necessarily signal that business is better prepared now for a future of global change than it was fifteen years ago. Preparedness requires, for business, as it does for policymakers, internalising the recognition that environmental risks are inextricably linked with social, economic, geopolitical and technological changes. Without this internalisation, the pursuit of short-term economic gains rather than investing in the shift to sustainable practices is more likely to compound global-scale risks than to provide a buffer against them. Shifting risks and resilience to disruptive changes (including to intended transformations) will need to be captured in a richer multidimensional research-based story that expresses intertwined social and ecological concerns and possibilities,Footnote 87 not just ‘science-based’ quantitative assessments of qualitatively degraded biophysical conditions.

Table 2. The highest-ranked global risks in terms of likelihood identified in annual World Economic Forum surveys for The Global Risks Report 2010–2023 (compiled by the authors from annual reports available at www.weforum.org/reports).

D. Risks of unsustainability can act as a driver for change

The recognition of financial risks of climate change has placed the connection between business and environmental unsustainabilities under unprecedented scrutiny. It is acting as a driver of change, and creating a new locus of science–business–policy interactions.

The recommendations presented by the business-driven ‘Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures’ (TCFD)Footnote 88 are regarded as a gold standard for business.Footnote 89 The recommendations, while informed by the science basis for recognising that climate change entails financial risks, were based on consultations with business.Footnote 90 The TCFD was led by the US business person and politician Michael R. Bloomberg, and its 31 international members included ‘providers of capital, insurers, large non-financial companies, accounting and consulting firms, and credit rating agencies’.Footnote 91 In 2023, its final year, the TCFD had close to 5000 ‘supporters’, apparently representing a ‘combined market capitalisation of $29.5 trillion (£23.5 trillion), with over 1,800 financial institutions responsible for assets of $222.2 trillion’.Footnote 92 The TCFD had international legitimacy (especially in high-income countries) from the start, as it was established by the Financial Stability Board, an ‘international body’ endorsed by the Heads of Government and State of the Group of Twenty (G20), a group of the world’s major economies.Footnote 93

As we show in Section 4, the TCFD is also regarded as a template for international and European regulatory initiatives. Indeed, according to the TCFD itself, 19 jurisdictions (including the EU), representing ‘close to 60% of global 2022 gross domestic product’, have requirements of some kind that incorporate or draw on the TCFD recommendations.Footnote 94

However, when analysed from a research-based sustainability perspective, the TCFD recommendations have shortcomings, beyond the obvious point that the report concentrates only on climate change. The TCFD’s approach to physical risks is limited, and human and societal impacts are not included in its risk categories.Footnote 95 Yet, international recognition of the recommendations is unaffected by these shortcomings, with the International Sustainability Standards Board taking over the follow-up from 2024.Footnote 96

The recognition of environmental risks of unsustainability is now broadening towards encompassing financial risks of biodiversity loss, through the ‘Task Force for Nature-Related Financial Disclosures’ (TNFD), launched in 2021 and with the first version of recommendations published in 2023.Footnote 97 The aim is an ‘integrated approach to climate- and nature-related risks, scaling up finance for nature-based solutions’.Footnote 98 It is positive that the discussion of risks now addresses biodiversity as well as climate change. However, criticism has been raised of corporate capture of the process, highlighting the risk of continued greenwashing.Footnote 99 As commentators have highlighted, allowing a group of ‘executives from big corporations and financial institutions’ to set the ground rules for disclosure in this area, raises serious questions about ‘representation, accountability and conflict of interest’.Footnote 100 Indeed, the ‘Task Force’ itself consists of 40 ‘senior executives from financial institutions, corporates and market service providers’. One of the two co-chairs is from the United Nations Environmental Programme, lending international legitimacy to the project.Footnote 101 Further legitimacy is bestowed upon the TNFD by its long list of ‘Knowledge Partners’, including academic institutions (amongst them Stockholm Resilience Centre, a key science organisation behind the planetary boundaries framework), the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB),Footnote 102 and more recently, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG).Footnote 103 Civil society has criticised TNFD for working in a way that is ‘shrouded in secrecy’ and developing a framework that ‘is distracting from, and undermining, real and sustainable solutions’. Footnote 104

It is not fruitful to develop, piece by piece, risk frameworks for each aspect of sustainability, nor to impose approaches designed for climate change onto other environmental challenges.Footnote 105 The limited and fragmented disclosure infrastructure that TCFD and TNFD have been outlining for business action may give rise to an increase in the financial and corporate risks of unsustainability, undermining the integration of sustainability into corporate governance.

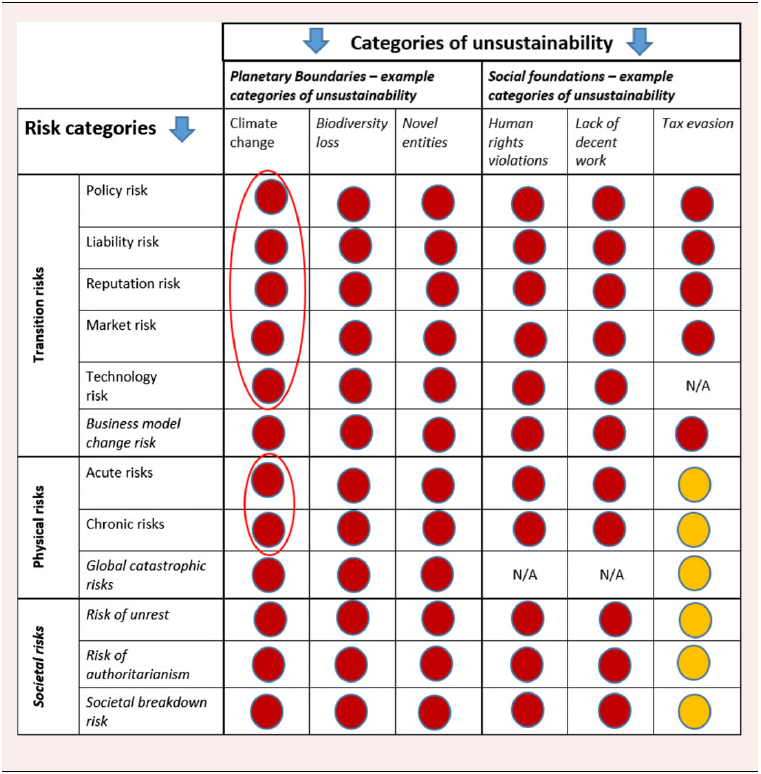

Rather, risks must be dealt with together, within the framework of a research-based concept of sustainability.Footnote 106 An indication of such a safe and just approach is presented by Sjåfjell,Footnote 107 and summarised in Table 3 below. Categories of unsustainability are proposed that encompass the continued pressures on planetary boundaries (exemplified with climate change, biodiversity loss and novel entities), and the undermining of social foundations (showing human rights violations, lack of decent work and tax evasion as examples). Broadened risk categories are also proposed, with business model change added to the transition risks, and global catastrophic risk to the physical risks. Further, societal risks, including unrest, authoritarianism and societal breakdown, is added as a new risk category. This broader approach to risks of unsustainability sets sustainability at the heart of business governance, and could be part of an adaptive, responsive system for sustainable corporate governance. This could increase resilience to the poorly predictable, weakly controllable, and increasingly turbulent global conditions that are anticipated.

Table 3. Risks of unsustainability

Source: Sjåfjell 2024, drawing on teamwork in the SMART project, notably Sjåfjell et al 2020. Unsustainability categories are shown in vertical columns, risk categories in horizontal rows. Red circles indicate that environmental degradation or social harm entails direct risks within the various risk categories. Orange circles indicate indirect risk, while N/A explains that the category of unsustainability is not assumed to involve the specific risk category. The red outline highlights the seven categories from the dominant climate risk approach introduced in TCFD 2017. Italics indicate new risk categories.

Yet, this research-based conceptualisation of risks of unsustainability remains in contrast to actual business approaches, where sustainability risks are regarded as an add-on that can be dealt with through voluntary disclosure. As we show below in Section 4, policymaking follows up along the same lines, dealing with sustainability risks as a matter of reporting and disclosure requirements.

Critiques of today’s science–business–policy interfaces from civil society and academic actors are muted, despite the ways that these interfaces actually reproduce hegemonic discourse(s) and existing power relations.Footnote 108 In these coalitions of elites, no space is given for other people’s experiences and capabilities. Academic norms of neutrality and scientific objectivity generate strong incentives to suppress critical debate, where views that depart from the authoritative ‘science-based’ messages are seen as radical or political statements, as if the recommendations for transformation that are being made were somehow apolitical. The room for nuanced and constructive discussions of how to ensure the contribution of business to a safe and just space is thereby deeply constrained.

4 What is the EU actually doing?

A. The EU’s unrealised potential as a supranational power

Compared to international law, the supranational legal order of the EUFootnote 109 has unprecedented power to regulate market actors. The EU can regulate, shape and influence decision-making in the many businesses, small and large, that are headquartered or based in the EU. The EU’s regulatory power has limitations, including its shared competence with EU Member States in key areas. Yet, the EU is both a powerful European legislator and a global actor, and its influence goes beyond its actual regulatory competence.Footnote 110 The EU Commission’s flagship programme, the European Green Deal, highlights that as ‘the world’s largest single market, the EU can set standards that apply across global value chains’ and support European and global markets for ‘sustainable products’.Footnote 111 The EU accordingly has the potential for integrating sustainability in and across globalised and interconnected business.

This gives rise to the question of whether we can trace any research-based understanding of sustainability in the EU’s policy documents and legislative initiatives. Certainly, the planetary boundaries concept has gained interest.Footnote 112 It is seen as a multidimensional framework for analysing systemic effects of environmental policies, helping identify opportunities for vertical (cross-scale) and horizontal (cross-sectoral) coherence in policy planning and implementation. It is also seen as providing a basis for specifying ‘absolute’ environmental sustainability criteria that help characterise and concretize aspirational statements. The EU’s 8th Environment Action Programme sets out amongst its priority objectives that ‘people live well, within the planetary boundaries in a well-being economy where nothing is wasted, growth is regenerative, climate neutrality in the Union has been achieved and inequalities have been significantly reduced’.Footnote 113

It is symptomatic, however, that neither the European Green Deal nor one of its major building blocks, the EU’s Sustainable Finance initiative,Footnote 114 mention ‘boundaries’ or any form of constraints or limits although apparently acknowledging the severity of environmental degradation. The Green Deal recognises that ‘the global climate and environmental challenges are a significant threat multiplier and a source of instability’ and the ‘ecological transition will reshape geopolitics, including global economic, trade and security interests’, and it expresses an aim to work with all partners to ‘support a just transition globally’.Footnote 115 However, the central aim appears to be to support the EU’s own transition rather than fully engaging with global goals for a sustainable future. And in line with the dominant finance-driven approaches, its emphasis on ‘sustainability risks’ is limited to climate and environmental risks, excluding human and societal risks.Footnote 116 Indeed, the EU’s initiatives have been assessed as lacking integration of all aspects of sustainability, including a lack of recognition of ecological limits of our planet.Footnote 117

Further, the Green Deal sets out from the start that it is a ‘new growth strategy … where economic growth is decoupled from resource use’.Footnote 118 ‘Regenerative growth’ is also the approach of the 8th Environment Action Programme. Yet, there is very little research-based support for this premise.Footnote 119 Measuring the EU’s ambitious environmental goals against empirical results underlines this point: EU countries mainly exceed their share of global limits.Footnote 120 While EU countries may have made progress preventing their own local environmental harms, they are contributing to eroded resilience far beyond their territories. Analysis shows that European pressures on planetary boundaries often have regional impacts that are crucial in low and lowest-income countries, undermining their access to resources necessary for positive social development.Footnote 121 These two points are interconnected, both because breaching planetary boundaries will have greater impacts on some countries due to their geographic location, and because most-impacted countries may have fewer economic resources available for adaptation.Footnote 122

These empirical results on European consumption and production are not in line with the EU’s overarching Treaty aims on sustainability, nor, specifically, its provision dealing with the relationship between the EU and the international community, where the EU expresses that it shall ‘foster the sustainable economic, social and environmental development of developing countries, with the primary aim of eradicating poverty’ (Treaty on European Union, Article 21(2)(d) and (f)). Policy coherence for development is set out as an EU legal norm in the Treaty on Functioning of the European Union, Article 208, requiring that any area of EU law and policy must not work against development policies, also with the sustainability aim of ‘leaving no one behind’.Footnote 123

The emphasis in the EU Green Deal on creating a Just Transition and leaving ‘no one behind’ appears generally to be limited to ensuring justice in the transition to sustainability within the EU Member States. References to those ‘most vulnerable’ do not appear to encompass vulnerable people and communities outside of the European Union.Footnote 124 Yet, the vulnerability of workers across global value chains is exacerbated through ‘business model(s) based on exploitation and abuse of human rights’.Footnote 125 Indigenous Peoples are amongst the most vulnerable communities, exposed to exploitation by states and businesses alike.Footnote 126 The Green Deal makes no mention of Indigenous Peoples, in Europe or in the rest of the world. This omission is contrary to the environmental aims of the Green Deal, as their traditional land management strategies are among the world’s most effective in protecting biodiversity and contributing to climate mitigation.Footnote 127 It is also, and most crucially, a missed opportunity to confront the long history, within and beyond Europe, of exploitation of Indigenous Peoples, from colonisation by states to the ongoing neo-colonisation by business.Footnote 128

B. Thwarted EU attempts at regulating business for sustainability

EU institutions have a Treaty-based duty, with a correspondingly clear legal basis, to integrate sustainability into the governance of European business.Footnote 129 Meeting this duty requires a fundamental change in the regulation of business. The current regulatory framework for business has encouraged the perception that minimum compliance with (insufficient) legal requirements is adequate. In practice, the individual legal entity of the company is still allowed to externalise its responsibility for negative environmental and societal impacts. The EU recognises the need for regulatory reform. This may be the beginning of a shift away from a siloed approach where environmental law and policy were perceived to be sufficient to ensure adequate environmental protection, where labour issues could be left to labour law and human rights issues to human rights law, etc. Business law currently reinforces the inherent limitations of this siloed approach and is associated with negative environmental and social business impacts.Footnote 130

The current emphasis on regulating businesses to integrate aspects of sustainability into their governance may be traced back to changes in EU policy perceptions after the 2007-2008 financial crisis. For many years, corporate social responsibility (CSR) was conceptually the umbrella under which business impact on society was discussed. After the financial crisis, the Commission in 2011 revised its 2002 definition of CSR, rejecting mere voluntary integration by business of ‘social and environmental concerns in their business operations’, and explicitly discussing the responsibility of business for impact on society.Footnote 131 Yet, the legislative follow-up was limited.

One outcome was the adoption of the so-called Non-Financial Reporting Directive of 2014,Footnote 132 which set out requirements for reporting by the largest businesses on ‘the impact of [their] activity, relating to, as a minimum, environmental, social and employee matters, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery matters’.Footnote 133 The approach of the Directive, including the lack of enforcement of the reporting requirements and of requirements for verification of the information provided by companies, negated the legislative aim of shifting businesses onto a sustainable path. The Directive gave far too much discretion to Member States on the implementation, and to businesses on the reporting (with a ‘comply or explain’ approach) for these reporting rules to have significant impact.Footnote 134 By not confronting the social norm of shareholder primacy, the chasm remained between the perceived role and duty of the board and management (to maximise returns for shareholders), and the ‘non-financial’ issues that boards and management were asked to report on. However, the 2014 Directive shifted the focus in the EU Accounting Directives on information relating to environmental and employee matters, which since 2003 had focused narrowly on the financial impact on business of such matters,Footnote 135 and opened up for a broader debate on the responsibility of business to contribute to sustainability.

The EU responded to the corporate governance failures exposed by the financial collapses and scandals in the 2007–2008 financial crisis, with a strong belief in the potential of better shareholder engagement as a way forward.Footnote 136 After several years of negotiations, facing resistance against the very idea of imposing any kind of duties, however mild, on shareholders, the EU adopted the reform of the Shareholder Rights Directive in 2017.Footnote 137 The Shareholder Rights Directive II seeks to encourage shareholders and notable institutional investors to become more active in a long-term and sustainability-oriented way and disclose their policies accordingly.Footnote 138 This may be seen as part of a global stewardship debate, discussing the potential of shareholder governance in promoting sustainability.Footnote 139 Moving from a narrow view on shareholder rights to a more open discussion on shareholder responsibilities and their role in corporate governance is positive. However, references to sustainability in the Directive were mainly framed as ‘the long-term interests and sustainability of the company as a whole’.Footnote 140 There is only one mention in the Directive itself of broader issues, with ‘social and environmental impact and corporate governance’ included in a long list of issues to be taken into account in the engagement policy of institutional investors and asset managers.Footnote 141 The indication that ‘environmental, social and governance matters’ also could be included, ‘where appropriate’, in the assessment of ‘[d]irectors’ performance’, never made it further than the Preamble of the Directive.Footnote 142

In 2018, informed by the specific understanding of financial risks of climate change in the TCFD recommendations, the Commission launched its Action Plan for Financing Sustainable Growth,Footnote 143 and what has become commonly known as the Sustainable Finance initiative. European financial markets provide the credit and financing required for businesses in the EU and beyond, making them fundamental to a successful transition to sustainable market activity and vital to realising the EU’s commitments on sustainability. An unusually speedy process resulted in legislative instruments of the strongest binding category (EU regulations as opposed to directives), including the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation of 2019Footnote 144 and the Taxonomy Regulation of 2020.Footnote 145 Both regulations aim to ensure that financial markets have reliable information about which economic activities are sustainable.

Yet the Taxonomy, this ‘cornerstone of the EU’s sustainable finance framework’,Footnote 146 is not about sustainability in any broad, research-based sense. The Taxonomy Regulation seeks to establish the ‘criteria for determining whether an economic activity qualifies as environmentally sustainable for the purposes of establishing the degree to which an investment is environmentally sustainable’.Footnote 147 The Taxonomy’s six environmental objectives go beyond climate mitigation and adaptation to include sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources; the transition to a circular economy; pollution prevention and control; and the protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.Footnote 148 However, the Taxonomy has just one paragraph in its Preamble on the ‘systemic nature of global environmental challenges’ and the need for a ‘systemic and forward-looking approach’,Footnote 149 and it makes no acknowledgement of the ecological limits of our planet and the concurrent urgency of a fundamental transformation.

There is even less consideration of the ‘just’ aspect of safe and just. The proposal for a separate Social Taxonomy, to complement the environmentally focused Taxonomy Regulation of 2020, has not been followed up.Footnote 150 The Taxonomy Regulation expects that an undertaking seeking to have its economic activities classified as environmentally sustainable, will implement procedures to ‘ensure the alignment’ with the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines, and through them, indirectly, also international human rights and labour law.Footnote 151 There are no Delegated Acts on these ‘minimum safeguards’. While the Taxonomy has its own ‘do no significant harm’ rule concerning the six environmental objectives,Footnote 152 it references the ‘do no significant harm’ rule in the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)Footnote 153 (which goes beyond the environmental issues to also include social and governance), for the carrying out of the procedures of the ‘minimum safeguards’.Footnote 154 However, the following up of this is limited and even counterproductive, as we return to below.

The SFDR sets out a relatively broad definition of sustainability risk: an ‘environmental, social or governance event or condition’. Yet, the SFDR does not position its understanding of sustainability risks within any research-based concept of sustainability. In line with the financial risks’ underpinning of the Sustainable Finance initiative, the emphasis in the SFDR is on ‘actual or a potential material negative impact on the value of the investment’, rather than on the impact on society.Footnote 155 While there is a recognition of the need for urgent action to shift finance in light of the ‘the catastrophic and unpredictable consequences of climate change, resource depletion and other sustainability-related issues’ that the EU faces, the choice of regulatory approach is the weak mechanism of disclosure.Footnote 156

As opposed to the Taxonomy Regulation, the SFDR sets out that to ‘qualify as a sustainable investment’, an economic activity must contribute to an environmental objective or a social objective, provided that it does no significant harm to any of these objectives and ‘the investee companies follow good governance practices, in particular with respect to sound management structures, employee relations, remuneration of staff and tax compliance’.Footnote 157 The Commission has highlighted that this, together with the reference from the Taxonomy to the SFDR, ‘ensures that minimum social standards are defined at European level, and that there is consistency in European legislation’.Footnote 158 However, the Commission’s guidance to ensure a coherent follow-up undermines the potential by stating that ‘Taxonomy-aligned economic activities’ are ‘deemed’ to have fulfilled the ‘do no significant harm’ and ‘good governance’ requirements, with reference to the minimum safeguards of the Taxonomy.Footnote 159

The approach of the Sustainable Finance initiative is constrained by the same flaws and partial scope of the risks approach on which it is based.Footnote 160 The limited inclusion of social aspects are, at best, encouragement to do due diligence and to report. We turn now to the developments on reporting and due diligence.

The 2014 Non-Financial Reporting Directive was replaced by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), adopted in 2022.Footnote 161 Made possible by the Sustainable Finance Initiative,Footnote 162 the CSRD appears to signal a shift towards policymakers taking sustainability aspects as seriously as they for decades have taken traditional financial issues, with firmer rules and auditing requirements.Footnote 163 Reforms were very much needed for corporate sustainability reporting requirements (a term preferable to ‘non-financial’ reporting requirements), to make them more stringent and with requirements for external verification. While covering a broad set of sustainability-relevant aspects, the underpinning of the whole Sustainable Finance initiative is present in the recognition of a ‘very significant increase in demand for corporate sustainability information’, a demand ‘driven by the changing nature of risks to undertakings and growing investor awareness of the financial implications of those risks’, especially concerning ‘climate-related financial risks’.Footnote 164 ‘Corporate sustainability’ is not defined. Sustainability reporting is defined, though, as reporting on ‘sustainability matters’, which ‘means environmental, social and human rights, and governance factors’, including those listed in the SFDR.Footnote 165 The requirements for the sustainability reporting are embellished compared to the 2014 Directive, and include the business model and strategy, specific requirements for climate objectives, and spelling out the sustainability risks.Footnote 166

The push-back internationally, especially in the United States, and within Europe, against sustainability-oriented (‘ESG’) legislation,Footnote 167 created tension between the EU’s own follow-up of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and the International Financial Reporting Standards body, with a pressure for convergence between international and European sustainability reporting standards. The Commission Delegated Regulation to set out European Sustainability Reporting Standards adopted in July 2023 and seeking this convergence, has been criticised as a step backwards for corporate sustainability reporting.Footnote 168 With the TCFD and the TNFD strongly influencing the European Sustainability Reporting Standards,Footnote 169 the weaknesses of these business-driven initiatives are integrated directly into EU law. There is no ‘safe and just’ understanding of sustainability informing this stream of legislation. References are made to various aspects of environmental and societal issues in a fragmented and incoherent manner. There is a (limited) inclusion of the OECD Guidelines and UNGPs, and international human rights and labour law, in the CSRD and ESRS as we saw above in the Taxonomy and SFDR. This is unprecedented, and can be seen as seeds for change, yet it is far from sufficient. Consistently, mitigating financial and corporate risks of environmental issues, and notably climate change, is prioritised. All of these instruments rely on disclosure. Alone, disclosure as a regulatory tool is clearly insufficient to shift business towards sustainability.Footnote 170

Finally opening up for sustainability-oriented action on core company law issues, the Sustainable Finance initiative indicated a role for legislative intervention in the rules concerning corporate boards.Footnote 171 Reinforced by the EU Green Deal’s statements that ‘sustainability should be further embedded into the corporate governance framework’,Footnote 172 the Commission launched its Sustainable Corporate Governance initiative in 2020.Footnote 173 Its goal was to change company law and corporate governance to promote long-term creation of sustainable value.Footnote 174

However, the Sustainable Corporate Governance initiative was constrained through very strong resistance from business lobbyists and some academics.Footnote 175 The Commission’s originally more ambitious proposal was stopped twice by the Commission’s own Regulatory Scrutiny Board after intense lobbyingFootnote 176 – to the extent that the European Ombudsman has opened an investigation into the Regulatory Scrutiny Board.Footnote 177 The Commission eventually put forward its proposal in February 2022 for a Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive.Footnote 178 Due diligence was the one aspect of its undoubtedly broader reform programme that the Commission felt it had support for, with the mainly environmental focus of the Sustainable Finance Initiative merging with the push for mandatory human rights due diligence, informed by the UN Guiding Principles, supported by the European Parliament and a range of national legislative initiatives.Footnote 179 Further, reporting on due diligence was already included in the CSRD and expected under the ‘minimum safeguards’ and ‘do no significant harm’ requirements of the Taxonomy and the SFDR, respectively.

In spite of the political consensus achieved between Member States and the European Parliament in December 2023, the road towards adoption of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive was to become even more rocky.Footnote 180 After months of uncertainty and horse-trading amongst Member States, the Directive was adopted with a much reduced scope in terms of companies included in June 2024.

The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD)Footnote 181 is a legislative instrument that is very much on the defensive, with ‘corporate sustainability’ left undefined but in practice limited to those elements that can be traced back to the mainly international environmental and human rights legal instruments. The CSDDD does not engage with planetary boundaries nor have any kind of references aligned with the safe and just framework. Its engagement with social issues is limited; it does not include fair taxation and anti-corruption. And yet, indicating the tension in social norms and the emerging potential for change, some positive changes were included in the final version thanks to extensive support by civil society, academics, and businesses.Footnote 182 There are more detailed rules on the due diligence and its follow-up, with a firming up of the corporate sustainability requirements.Footnote 183 The price, however, was a much reduced scope of the CSDDD. Even the limited and flawed company law attempt at integrating sustainability issues into the role of the corporate board was left out.

The shareholder primacy drive explains the strong resistance to the Sustainable Corporate Governance initiative, the difficulty of getting the CSDDD into place, and the strong reaction to any indication of reforming EU company law. With its simplistic approach to measuring ‘good’ business governance through the maximisation of returns for investors, the shareholder primacy drive provides very receptive ground for the limiting ideas of governing for sustainability through quantified goal-settings and assessments. It also connects to entrenched macro-level economic efficiency ideas using economic growth (as GDP) as a measurement of the success of a nation state, with its deeply constraining effects for transformation.

With shareholder primacy opponents framing the discussion as a choice between shareholder primacy and an often vague and poorly defined stakeholder theory, company law proper, as the regulatory infrastructure for business, is left out of the debate.Footnote 184 This has proved to be a powerful way of constraining the discussion, and negating the possibility for the Commission to propose a meaningful company law reform.

In light of all this, the final adoption of the CSDDD with some strengthening of the due diligence rules is an important step towards more sustainability-oriented business law. With its now more explicit connection to the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines,Footnote 185 the CSDDD has the potential to be a hard-law basis for the argument of corporate sustainability due diligence emerging into a horizontal norm for business. Nevertheless, what it requires is due diligence – it could have explicitly mandated corporate sustainability, eg, through integrating research-based sustainable value requirements in the duties of the board.Footnote 186

The fact that the processes towards the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive were undertaken by separate Directorates-General (DGs) in the Commission is symptomatic of the stronger emphasis on finance. The CSRD, under DG Finance,Footnote 187 was adopted without much controversy, and is aligned with the Sustainable Finance initiative’s emphasis on mitigating risks and relying on disclosure as a legislative tool. The process towards the CSDDD, under DG Just,Footnote 188 was one that sought to promote actual change and facilitate sustainable value creation, and it was supported by civil society rather than being informed by a financial risks approach. As a result, it was extremely difficult to get into place. It also illustrates that reporting remains the preferred compromise solution between those who wish to continue with business as usual and those supporting the transformation towards sustainable business. Rather than taking the opportunity to close the chasm between accounting rules on reporting and company law rules on the corporate board,Footnote 189 Directorates-General still operate in silos and corporate capture continues to undermine efforts for sustainability-oriented legislation.

Unsustainable linear (‘take-make-waste’) business models are based on overproduction and overconsumption. The EU’s Circular Economy initiatives (under yet another Directorate-General, DG EnvironmentFootnote 190) seek to regulate products from the design phase onwards to promote more circular business models.Footnote 191 In 2022, the Sustainable Products Policy was launched, with ambitious plans for expanding the eco-design requirements for certain products, including household appliances, to products more generally, including textiles.Footnote 192 Integrating sustainability into product design has the potential to change the core of business models. However, the emphasis in the Circular Economy initiative remains on economic efficiency in the form of more efficient resource use, rather than aiming for sufficiency, informed by the need for absolute reductions in production and consumption.Footnote 193 The Circular Economy initiative does not fully integrate the recognition of the limits of our planet, in spite of references to planetary boundaries in the Circular Economy Action Plan of 2020, nor does it encompass social and governance aspects of sustainability.Footnote 194 Indeed, the Ecodesign Regulation for Sustainable ProductsFootnote 195 postpones until 2028 the assessment of whether social issues should also be included.Footnote 196 This shows that the Circular Economy initiative continues on the path of economic efficiency-based ‘greening’ rather than transforming the current economy.

The research-based concept of sustainability we have outlined, and notably the planetary boundaries framework, is referred to in several EU policy documents informing environmental legislative initiatives. International human rights law, the recognised minimum basis for social foundations, together with the internationally endorsed social norms of the OECD Guidelines and the UNGPs, is being included in EU finance and business law in an unprecedented way. Yet, this is also being done in a very reticent way. Common for the adopted legislative initiatives outlined above, is that they do not properly engage with any meaningful conceptualisation of sustainability. The disconnect between the Circular Economy initiative, the Sustainable Corporate Governance initiative, and the Sustainable Finance initiative reveals how they are shaped by somewhat different rationales, while they all are informed by the illusion of green growth and the emphasis on economic efficiency. The initiatives discussed in this section further illustrate the EU’s emphasis on the largest business entities and their belief in the transformative power of financial markets.Footnote 197 They exclude most SMEs.Footnote 198 This is based on a misconception, promoted by business lobbyists, that regulating for sustainability entails burdens and costs only. Yet, achieving a ‘Just Transition’ entails securing a level playing field and legal certainty for sustainability-oriented businesses, channelling the potential of entrepreneurship across Member States, and dedicating sufficient resources to facilitating the sustainability transition of all European businesses.Footnote 198 It also, crucially, entails regulating for a fundamental transformation, where securing the ecological basis for human prosperity on this planet, and the bases for good lives for people everywhere, is prioritised above the interests of financial and corporate actors. Financial and economic goals can meaningfully only be regarded as instrumental goals.

C. The EU’s fixation on growth and finance derails its sustainability efforts

The EU’s attempts at regulating business for sustainability are historically and globally unprecedented, and yet they are fundamentally insufficient. Its policies appear to be informed by the conviction that continued pursuit of economic growth as a macro goal, reflected in business as the maximisation of returns for shareholders as a micro goal, is necessary and possible. That economic growth explains human prosperity historically and is necessary for continued progress is increasingly called into doubt.Footnote 200 The justification for continuing with ‘business as usual’, that negative environmental impacts can be completely decoupled from economic activities, does not have empirical support.Footnote 201 Likewise, the assumptions underpinning the idea that maximising returns for investors increases social welfare have been disproven.Footnote 202 Yet, these postulates continue to constrain political imagination and negate any truly transformational proposals. Prioritising economic growth and financial interests is contrary to a comprehensive approach to sustainability that recognises the inextricable interconnectedness of environmental, social and governance aspects. When the complex, interconnected and dynamic nature of sustainability is simplistically broken down to separate, fixed and ‘objectively’ determinable performance targets and indicators, unavoidable tensions are concealed, and misleading approaches continue to inform policies.

How could a regulatory framework for business governance for sustainability then be shaped to navigate the tensions and mitigate the dangers of oversimplification arising from these dominant science–business–policy interactions? A starting point is to understand corporate sustainability as being about the contribution of business to global sustainability, taking this contribution seriously, and recognising that the ever-present tensions cannot be simplified away through narrowly selective quantifications and disclosures. This also entails not expecting or waiting for globally quantified science-based targets for all aspects of sustainability. Regulating for sustainable business governance means finding a balance between being flexible and open enough to facilitate the innovative creation of value in each business (because corporate sustainability cannot be achieved through top-down planning of everything), while being firm enough on the goals and processes to shift business away from the unsustainable path-dependent trajectory of business as usual on to a more sustainable direction. Crucially, such a regulatory framework will need to include thoughtful process-oriented rules to facilitate the open, inclusive and participatory processes that must be a part of the governance of globalised business.Footnote 203