1. Introduction

Administration of law without forms is doubtless as impracticable and undesirable as administration of justice without law. (R. Pound)Footnote 1

If procedures are the engine room of a vessel, which is the judicial system, orders are an essential part of the mechanical equipment. Their function is to steer the machinery of justice fairly and efficiently. In a well-functioning system, the engines hum silently. In the European Union judicial system, the rumble from the national courts, and the troubling institutional reforms,Footnote 2 signal malfunction, calling for a maintenance check or repair.Footnote 3

This article uses the orders of the European Court of Justice (the Court) to zoom into the engine room of the European Union’s judicial system. It proposes the first comprehensive taxonomy of orders, mapping over 5,000 documents. The taxonomy crosses the distance between the purely practical matters and the academic debates about adjudication, unpacking the hidden layers of the Court’s working methods.

Orders are an unusual object of legal analysis, which explains why they have remained an untapped legal resource.Footnote 4 The Court’s Rules of Procedure (RoP), the main legal source regulating orders, is formally an implementing act and rarely a matter of scholarly interest.Footnote 5 The RoP contain exhaustive – but not at all hard and fast – rules on the handling of cases. They appear prosaic, doctrinally uninteresting, and possibly odd to the outsiders and academics who have never argued a case in Luxembourg. The day-to-day administration of the RoP is the bread-and-butter of legal practitioners, inside baseball between legal counsel, government agents, avocats, barristers, the Court’s staff, and its members. Detailed procedural instructions are not easily accessible.Footnote 6 The Internal Guidelines with comprehensive information about case management are not a public document.Footnote 7 Therefore, in the absence of a Common Code of Procedure, the RoP constitute the nervous system of European procedural law, operationalising fundamental principles, procedural guarantees, due process, and daily logistics.

At the outset, the analysis distinguishes between the orders on the merits of the dispute and procedural orders, based on their nature, substance, and institutional aspects.Footnote 8 The former include decisions that reply to preliminary questions of the referring courts, or dismiss appeals against the judgements of the General Court as unfounded. They are typically reasoned. Examples of the latter are a decision to grant legal aid, request additional documents, or dispense with a hearing. Procedural orders can be strictly procedural or procedural administrative. Strictly procedural orders ensure the correct application of procedural rights during the procedure (the right to intervene, submit written pleadings, evidence, or testimonials), and affect the substance of disputes only indirectly – by imposing a form on the substance of the dispute. Frequently, they are issued by the sitting judges. Administrative procedural orders principally relate to case-management, like the orders to reopen or stay the oral proceedings.Footnote 9 Even if the exact boundaries remain unclear,Footnote 10 the tasks are distinct and indispensable.Footnote 11 Finally, administrative orders typically involve the Court’s Registry/central administration, such as the order to remove a case from the Registry.

Orders are inseparable from procedural economy, and as such naturally affect the length of the proceedings. The taxonomy considers this fact by distinguishing between the orders, which shorten the proceedings and increase procedural economy (contributing to the efficient handling of cases), and orders, which extend the length of the proceedings (adding procedural steps). Finally, the taxonomy accounts for the implications of orders on deliberation – orders can either expand or reduce the deliberation phase. Orders with limited or no effect on the deliberation and the duration of the proceedings are deliberation neutral and classified accordingly.

To paint an accurate picture of the Court’s practice, the article relies on the automated parsing of the texts of orders published from 1954 to 2020 and accompanying information (the so-called metadata).Footnote 12 Automation is necessary given the amount, the legal diversity of orders (42 different orders), and the Court’s practice of referring to all documents indiscriminately as orders.Footnote 13 Finally, the RoP are detailed but adaptable to the case’s complexity. Mapping is key to the understanding of the procedural practice.Footnote 14

The analysis reveals the blurring of lines between administration and judging. This is reflected in a growing use of procedural administrative orders and orders on the merits, which delegate judicial tasks to the administrative support units manned by national legal experts. The coordination of the latter is in the hands of the Cabinet of the President of the Court, who is also involved in the decision-making process and the final decision on the merits. The trends coincide with manifold amendments of the RoP, intended to reduce procedural delays and tame the flood of preliminary references (that is, the quest for efficiency).

One should not demonise efficient distribution and division of tasks, especially when resources are scarce, the dockets are swelling, and procedural delays paralyse the judicial system. Moreover, there are good normative and pragmatic reasons for leaving case management to the Court, allowing it to respond to the challenges of its time swiftly and autonomously. Democratic legislators do not (nor should they) systematically meddle in the business of courts.

The examination of procedural reforms and proposed solutions to solve the problem of backlog, however, suggests that the Court has not been at the mercy of the dockets, nor a helpless bystander in the processes of institutional transformation. It actively co-designed and initiated reforms, prioritising effectiveness, imposing demands on its interlocutors – particularly on the referring courts – and guarding its interpretive monopoly. The Court consciously opted for limited deliberation and participation, insisting on delivering timely justice on its own terms – by entrenching its status and custody over European Union law.

These conclusions can contextualise the debates on the reasoning of the Court and its relationship with the referring national courts, inform the discussion about the effects of institutional expansion and enlargement, and provide a factual basis for policy proposals addressing overwhelmed judicial institutions and procedural delays.

The argument develops in five sections. Section 2 situates the orders of the Court in debates about the European justice system and adjudication, and introduces the Court’s RoP. Section 3 draws on these debates when presenting a taxonomy of orders. Section 4 surveys the Court’s use of orders, identifying broader patterns and trends. Section 5 teases out the rationale, which motivates the use of orders, and two implications for the institution and the judicial process: centralisation and bureaucratisation. Section 6 summarises the argument and concludes.

2. Efficient form and uniform law: The values of the European judicial process

On the one hand, orders might strike one as obscure legal sources of limited doctrinal significance. They are official documents, tersely accounting for minutiae and decisive procedural turns. The overly factual and technical RoP, which provide the immediate legal basis and the framework for orders, are the domain of insiders. On the other hand, the same features that make orders appear mundane – their factuality and detail – make them the most reliable markers of the judicial process. From this perspective, orders become an ideal ground for examining the gap between the stated principles and aspirations of a legal order (like a complete system of judicial protection).

A. The subtle constraints and liberties of the Court in a mature system of judicial protectionFootnote 15

The Court’s contribution to the making of the European Union legal system is undoubtedly significant:Footnote 16 The Court carved out the fundamental principles from the silent Treaty Articles, and carried the integration process forward when the political forces were pulling it apart.Footnote 17 Literature has examined the factors underwriting the story of effective supranational adjudication.Footnote 18 The present analysis complements the existing literature by prying open the procedural forms of the Court’s decision-making process, and the ways in which these forms restrain or facilitate the pursuit of the values of the European legal system.Footnote 19

The Treaties impose few explicit constraints on the Court regarding procedural form.Footnote 20 Institutionally, the Court has the autonomy to self-organise and self-manage its working process. With porous boundaries, limited input, and scant control of other institutions, including the European legislator, it is free to adopt and apply the rules. The situation is not particular to the Court but common to judicial institutions in democratic societies. The distinctiveness of the European administration of justice is the asymmetry between the substance and the form, that is, the legal nature of procedural rules and the process for their amendment.

A subtler limit to the Court’s procedural freedom and autonomy is the requirement of uniformity, a practical necessity of a supranational legal system. Formal rules (like the RoP) can support and assure uniformity by giving the Court an interpretive monopoly (like the exclusive jurisdiction in the preliminary reference procedure in Article 267 TFEU)Footnote 21 and a broad jurisdiction in appeals. In practice, however, uniformity hinges on (1) the goodwill of national courts to submit preliminary references and adhere to the answers and (2) the compliance of Member State governments with the rulings rendered in infringement proceedings.Footnote 22

The Court has won the loyalty of national courts and secured compliance with its rulings.Footnote 23 On the flip side, the trust of national courts progressively translated into a stream of preliminary references. The symbiotic relationship with the Commission and the exclusive jurisdiction in appeals further added to the backlog. As the system matured and evolved, the potential risks of incoherence grew. This is again a common development in judicial institutions with no power to select cases.Footnote 24

The Court’s working process first became a topic of public debate when procedural delays reached the limits of tolerable (it took over two years for the Court to reply to preliminary references), threatening to erode the Court’s legitimacy and authority.Footnote 25 Given the pile of pending cases on open display, no one questioned the nature and the gravity of the problem. The Court and the judges had recurrently acknowledged and expressed concerns over their workload and the length of the proceedings in extra-judicial writings, Annual Reports, and explanatory notes accompanying formal proposals for the amendments of the RoP. Scholars concluded that the Court had fallen victim to its own success.Footnote 26 A comprehensive reform, featuring legislative intervention to increase the output and reduce delays, seemed inevitable.Footnote 27

The proposed solutions had a mature legal order in mind,Footnote 28 meriting a flexible rapport with the national courts, and a constructive judicial dialogue on topics of broad European relevance.Footnote 29 The reforms assumed that national judges had had enough time to internalise the new legal order and the terms of its interpretation and application. The Court contributed to this impression with the CILFIT criteria, outlining the duty of the highest national courts to submit preliminary references.Footnote 30 Among other adjustments, the RoP introduced the orders on the merits (Section 3) to reply to repetitive preliminary references. Even if the solutions sought to balance the quality of deliberation with the quantity of the Court’s output, their main aim was to increase the latter without surrendering too much of the former.

Scholars occasionally wondered whether the reforms struck the right balance, highlighting their undesirable side effects: decreased deliberation and poorer quality of legal reasoning.Footnote 31 Both negatively affect the persuasiveness and the acceptability of the Court’s pronouncements (legitimacy),Footnote 32 already aggravated by the opaqueness of its decision-making process.Footnote 33

Finally, the institutional side-effects of a mature and overburdened justice system include the transformation of the office of the President of the Court, the bureaucratisation of the Court and the rising status of administrative (non-judicial) staff and secretariats.Footnote 34 The Registry, for instance, becomes central.Footnote 35 Coordination typically streamlines the process and increases the output while securing the continuity of the practice. Even if its effect on the law is elusive and unpredictable, it is certainly thinkable (and troubling) that the streamlining of the form in the RoP streamlines (impoverishes) argumentation.Footnote 36

B. The RoP as a moving target

The main legal framework of orders are the RoP operationalising broad Treaty requirementsFootnote 37 of judicial protection and remedies.Footnote 38 The Treaty and the Statute have not changed the organisation of procedures significantly since 1959. Major changes include the Treaty of Amsterdam (1999), which gave the Court the right to propose amendments to the RoP, and the Treaty of Nice (2003), which additionally simplified this process. Under the current legal regime, the Council approves the Court’s proposals with a qualified majority. The Treaty of Lisbon added Article 255 TFEU, establishing an expert panel to assess the suitability of the candidates to the Court. The Statute introduced the office of the Vice President and reformed the Grand Chamber in 2012.Footnote 39

The current RoP from 2012 are organised in eight Titles,Footnote 40 further divided in Chapters. The Titles lay out the internal organisation of the Court and successive procedural stages. Individual rules apply to all procedures, like the rights and obligations of agents, advisers, and lawyers. Other Titles govern only procedures with direct actions or the review of decisions of the General Court. The 2012 RoP include (for the first time) a separate Title for the preliminary reference procedure.Footnote 41

The Chapters of the Titles detail the handling of narrower procedural or organisational matters, like the appointment of the members of the Court (judges and Advocates General), the allocation of costs, the assignment of cases, or legal aid. The provisions on orders are scattered across several Titles and Chapters and should be interpreted in that narrower legal framework. Similarly, as the Articles of the RoP, some Orders apply to all procedures, like the President’s order to stay the proceedings. Others are relevant to specific procedures, like the order to declare an appeal against the decision of the General Court manifestly unfounded.

As a formally binding source of law, the RoP are an implementing act. In practice they assume the role of a procedural code or legislation, regulating the procedures, the rights of the parties and imposing time limits. Just like other implementing acts, the RoP regulate the judicial calendar and the means of official communication, but skip details on case processing. Those are relegated to the (unpublished) Internal Guidelines. The rules on case assignment and the composition of Chambers are not included in the RoP.

As mentioned earlier, the Court can propose amendments to the RoP, subject only to the Council’s approval by qualified majority. In most Member States, amendments of procedural codes require parliamentary intervention and debate. The contrast is stark. The Treaty allows the Court to de facto mend any issue it considers troubling: the growing caseload, inefficiency, or repetitive questions.

The Court has made effective use of the so-called right of legislative initiative in a positive sense – to introduce amendments – and in a negative sense – to resist reforms. It has always resisted alternatives that could have reduced its control or status.

To illustrate, at the time of the establishment of the Court of First Instance (now the General Court) in 1989,Footnote 42 the Court immediately proposed an amendment to the RoP to declare an appeal manifestly well foundedFootnote 43 and unfounded.Footnote 44 In 2019, the RoP introduced orders to process the appeals against the judgements of the General Court concerning the decisions of selected independent boards of appeal (BoA).Footnote 45,Footnote 46 The Court can issue those orders unless the appeal ‘raises an issue that is significant with respect to the unity, consistency or development of Union law’ (Article 170 bis RoP), that is, by default.Footnote 47 So far, the Court considered that only one of 126 appeals raised a significant legal issue.Footnote 48

The Court’s resistance to reforms can be illustrated by its reactions to the proposals, debated especially in the period leading to the 2004 enlargement.Footnote 49 Those included a filtering mechanism for preliminary references, a possibility to limit the references to a handful of national courts, and the option of shared responsibility and competence for preliminary rulings between the Court and the (then) Court of First Instance.Footnote 50 The Court strongly opposed the establishment of a filtering mechanism in the Report on Judicial Reform,Footnote 51 citing its possible detrimental impact on the relationship with national courts, and the adverse consequences for the uniformity of European Union law. The Working Party agreed,Footnote 52 echoing those arguments. All major changes were rejected. Oddly, the Court and the Working Party were not at all concerned with the effects of marginal procedural modifications on judicial cooperation and uniformity.

3. A taxonomy of orders

Orders are a unique window in the judicial process, an ideal to explore the long-term implications of the Court’s choices, notably efficiency. Efficiency is a value, propelled by workload and sustained by external pressure. A comprehensive classification is the initial step to articulate the subtle trade-offs underlying its pursuit.

Most existing accounts of orders follow the characteristics of orders in the RoP,Footnote 53 or analyse only selected types of orders in a narrower context, such as orders on the merits issued in reply to the preliminary questions in the preliminary reference procedure.Footnote 54

This Section proposes the first comprehensive taxonomy of orders of the Court of Justice or any other international court.Footnote 55 First, it systematically maps the orders of the Court, identifying 42 legally distinct orders. Then, it describes each order with a reference to the RoP and its formal characteristics (like the signatory), adding analytical categories with information about the nature and the implications.

The mapping criteria are based on the reading of the RoP, numerous decisions containing orders, and scholarly literature on judicial protection and procedural law.Footnote 56 They indicate the division of labor in the institution, the decision-making power, the time spent to issue orders, and the degree to which the Court operationalises (rationalises) its workflow. The taxonomy incorporates aspects that are often discussed, and arguably of considerable concern to the Court, like procedural economy, judicial dialogue, or the uniform application of European Union law.

In this sense, the taxonomy approximates the debates about the price of efficiency, especially decreased deliberation, and reduced quality of legal reasoning. Following recent literature, which highlights the rising influence of the President of the Court, the taxonomy also considers the signatory of the order as specified in the RoP, and the probable implication of the use of each order on the division of labor within the institution (centralisation or the balance of power).Footnote 57

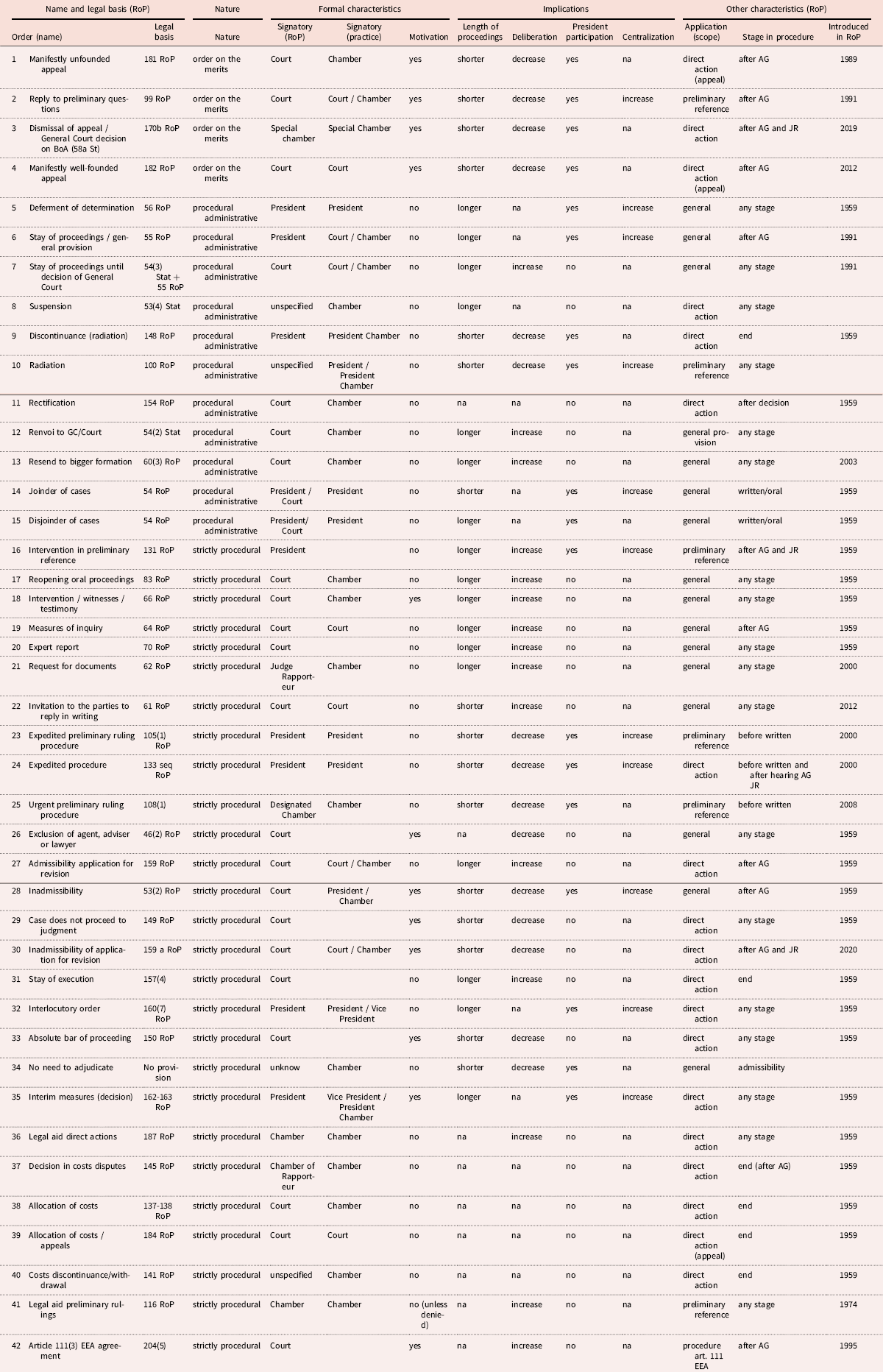

Table 1 provides an overview of orders following these criteria. The first two columns from the left indicate the name of the order and the legal basis as specified in the RoP. The third column from the left shows the initial distinction based on the nature of the order: order on the merits or a procedural order. Following the analysis of the RoP, Table 1 records the formal characteristics of orders, including the signatory of the order (according to the RoP and in practice), and the motivation. Additionally, Table 1 provides information related to the implications of the order on the length of the procedure, the centralisation of the decision-making process, and deliberation. Finally, it indicates the scope of application of each order (whether general or specific to a particular procedure), and the stage of the procedure in which the Court can issue it. The purpose of the representation of orders in the table format is to offer the most detailed, factual, and comprehensive overview of orders.

Table 1. An overview of orders, regulated in the RoP (adopted in 2012). The first column from the left indicates the name of the order from the RoP. The second column indicates the Article of the RoP (legal basis of the order). The third column indicates the function of the order: order on the merits, procedural administrative order or a strictly procedural order. Columns under the heading formal characteristics display the formal characteristics of orders. The column Signatory indicates the authority that signs the order according to the RoP, and the column Signatory (practice) indicates who signs the orders in practice. The blank spaces are left whenever there were not enough documents indicating the signatory in practice. The column Motivation indicates whether the order must be reasoned according to the RoP (yes/no). The four subsequent columns indicate the implications of the order. The column length of procedures shows whether an order shortens the procedures, usually by relaxing the procedural constraints, or extends it (shorter/longer procedure). The next column indicates whether an order increases or decreases deliberation. It approximates, albeit imperfectly, the quality of the decision-making process, and the decision. The column President Participation indicates whether the President or the administrative units under her supervision (the Registry or the Research and Documentation Unit) participate in the decision to issue the order. The column Centralisation indicates whether the order centralises the decision-making (either decreases or increases centralisation). Orders that do not have a strong effect on the decision-making – whose effect is almost neutral regarding deliberation, increased productivity or centralisation – are marked with ‘na’. Finally, the final three columns provide general information about the order. The column Application (scope) indicates whether the order applies to all procedures or only to direct actions/preliminary references/appeal proceedings. The column next to it indicates the stage in the proceedings in which the Court can issue an order. The final column indicates the year in which the provision regulating each type of order was added to the RoP

A. Primary distinction: Process and substance in the orders of the court

The main distinction of the taxonomy of orders relates to their nature: While procedural orders are concerned with the processing of cases (the form), orders on the merits of the dispute effectively decide the case (the legal substance).

Procedural orders provide a form in which the Court reaches the decision on the merits of the legal claim (petitum) and settles the dispute. They are diverse, ranging from factual administrative decisions (orders setting the date of the hearing) to decisions that govern (operationalise) procedural rights of the parties, like the right to be heard (the decision to reopen the oral part of the proceedings). Orders on the merits, by contrast, rule on the subject of the dispute (petitum). The distinction is reminiscent of the traditional form against substance divide. However, the analysis does not enter the debate but simply assumes that procedures are ‘a form in which legal solutions to the substantive problems should be cast’.Footnote 58

In this sense, procedural orders and orders on the merits fulfil complementary functions, and are as such not entirely separate categories. The line between form and substance is porous but visible. Procedural orders, like an order declaring that the preliminary reference is inadmissible, indirectly affect the rights and duties of the parties in the main proceedings. An order that the Court does not have the jurisdiction to rule on the claim, a procedural question par excellence, is frequently based on the substantive legal assessment of the case (it has a substantive component). By analogy, an order to reopen the oral proceedings or appoint an expert witness is not only a matter of procedure for the litigants. Experts’ testimonies can bear significantly on the decision whether the claim is justified, and hence on the outcome of the case. The Court’s decision to reopen the oral phase of the procedure can increase the quality of deliberation and swing the final judgement. Nonetheless, the immediate decision to reopen the oral proceedings is mainly procedural. Even if the division appears formalistic, it is useful for analytical purposes and the inquiry into the institutional dynamics. There, the questions who decides, how fast, and who is involved, are central. What the Court decides, and what strategies the litigants pursue, is important in other contexts.Footnote 59

The following Sections provide detailed descriptions, examples, and illustrations of the problématique (and the realities) captured by the taxonomy.

Strictly procedural orders and procedural administrative orders

Procedural orders, concerned with case management, are manifold and diverse. Some are communications and instructions (deciding when the oral hearing will take place), others are procedural decisions affecting the procedural rights of the parties and guaranteeing fair procedures (orders, which deny intervention or omit a hearing, deciding on the admissibility of the question or granting interim relief). Given the diversity, procedural orders can be further divided into procedural administrative orders and strictly procedural orders for the purposes of the inquiry.

Procedural administrative orders are orders by which the Court manages the case, like the order to delete the case from the Registry (radiation).Footnote 60 Importantly, these orders frequently involve the Court’s Registry.Footnote 61 For instance, in Case C-731/19, a Spanish court submitted a preliminary reference on certain aspects of the Court’s decision in Zaizoune.Footnote 62 The Court received the reference of the Spanish court in October 2019. In October 2020, while Case C-731/19 was pending, the Court clarified its decision in Zaizoune in Case C-568/19.Footnote 63 Pursuant to the latter, the Registry of the Court contacted the Spanish Court to inquire whether it still wished to maintain the preliminary questions. The national court swiftly withdrew the reference, and the President of the Court swiftly ordered that the case be erased from the Registry.

Strictly procedural orders primarily delimit procedural rights of the parties (to submit written pleadings, evidence, or testimonials), including interim measures and, ultimately, the decision to not hear the case (admissibility/jurisdiction). They are tangential to the substance of the dispute (they can effectively put an end to it), providing a procedural framework rather than allocating substantive rights and duties or redrawing the limits of European Union’s competences. To illustrate, in Case C-213/19, the Commission lodged an action against the United Kingdom for failing to fulfill its obligations in relation to textiles and footwear imports from China. Several Member States expressed their interest to intervene in the proceedings in support of the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom supported those requests, but also asked for the confidential treatment of data on individuals because ‘the mention of their names could affect their legitimate commercial interests, whereas disclosure of those names would not be of any benefit to the interveners.’Footnote 64 The President of the Court issued an order granting the intervention and the request for the confidential treatment of information. Withholding information probably affected the content of interventions, and hence the oral hearing and deliberations. It would be, however, mistaken to believe that the decision to allow the intervention and the confidential treatment of information was substantive/on the merits.

Orders on the merits of the case

Orders on the merits of the case bear directly on the legal claim.Footnote 65 They effectively settle disputes, allocate rights and duties, confirm the existing judicial allocation of rights and duties (in appeals), and authoritatively determine the questions of validity and interpretation of European Union law. Some orders on the merits are judgements bar their name. The difference between an order and a judgement is at times unclear. For instance, decisions in which the Court rules that it lacks jurisdiction or that the question is inadmissible could be judgements, but they are often orders pursuant to Article 53(2) of the Statute. To illustrate, in Case C-92/16, a Spanish reference on consumer protection, the Court ruled in the case with an order after soliciting a written Opinion of the AG and convening an oral hearing with seven interveners.Footnote 66

Orders on the merits of the case are typically reasoned. They can be further divided into orders on the merits of appeals and orders on the correct interpretation and validity of European Union law in the preliminary reference procedure. The distinction is pertinent because of the diverse institutional and procedural implications of those orders.

The first type of orders on the merits of the case are Article 99 RoP orders. The Court can issue them in reply to the preliminary questions of the national court where those are identical to earlier questions on which the Court has already ruled, where the reply may be deduced from the existing case law or where the answer is beyond reasonable doubt.Footnote 67 For example, in Case C-134/21, a Belgian Court inquired about the possibility of transfer measures against an applicant in the context of Dublin III Regulation. The Court decided to apply Article 99 RoP and replied by a reasoned order as the case ‘raised no reasonable doubt’. It was the second order in the case, as the Chamber already issued a procedural order rejecting the application for an urgent procedure.

The second type of orders on the merits are Article 181, Article 182 and Article 170 bis RoP orders, which allow the Court to declare an appeal, either against a decision of the General Court or of selected Boards of Appeals, manifestly unfounded, inadmissible, manifestly well-founded, or lacking significant legal interest. Examples are plentiful, owing to the Court’s frequent use of these orders (see Section 4). Just from January to April 2022, the Court rejected four appeals against decisions of the European Union Intellectual Property Office based on Article 170 bis.Footnote 68 The reason was the same in all of them: ‘the appellant’s request is not capable of establishing that the appeal raises issues that are significant with respect to the unity, consistency or development of EU law.’Footnote 69

Orders on the merits of the case affect the inter-institutional dynamics, altering the arrangement of authority over European Union law and the status of actors who participate in the judicial system. Potentially, they create tensions within the Court, between parts of the institution (that is, in relation to the General Court), and in the broader community of courts (that is, in relation to the national courts).

B. Formal characteristics of orders

Signatory of the order

The signatory refers to the authority in the Court that issues the order. The criterion is formal, referring to the RoP. Table 1 shows that the RoP are flexible: Orders are not necessarily issued by the signatory indicated in the Rules. According to the RoP, some orders are a formal prerogative of the Cabinet of the President. Only she can decide to join cases,Footnote 70 postpone the decision in the case to a later date,Footnote 71 grant an injunction,Footnote 72 or process the reference for a preliminary ruling in an expedited procedure. In practice, the President frequently delegates her prerogatives to the Vice President of the Court or the Chambers. The Vice President often decides on injunctions and the Presidents of the Chamber sign orders to remove the case from the Registry. Similarly, the RoP can refer to the Court without further specification. The examples include orders in important technical matters like the allocation of costs,Footnote 73 the decision to grant legal aid,Footnote 74 or the order to request additional documents.Footnote 75 The tasks most often fall on the Chambers of five and three sitting judges because they process most cases, and thus issue most orders.

Motivation

The RoP specify when the Court must motivate an order.Footnote 76 Thus, it is useful to distinguish between reasoned (motivated) and non-reasoned (non-motivated) orders. Reasoned orders can declare an appeal manifestly well-founded or unfounded,Footnote 77 bar the continuation of the proceedings,Footnote 78 exclude legal counsel,Footnote 79 allow interventions or the hearing of witnessesFootnote 80 and declare an action inadmissible.Footnote 81 According to the RoP, the Court must state reasons in 12 out of 42 instances (sixth column from the left in Table 1). Somewhat counterintuitively, reasoned orders often decrease deliberation and shorten the proceedings (the four columns under the heading ‘implications’ in Table 1). The Court can issue them either in direct actions or preliminary reference procedures. Many orders can be issued at almost any stage of the proceedings (like the order that the case will not proceed to judgement). Most often, the RoP specify that the Court can issue a reasoned order only after the consultation/hearing of the Advocate General (column ‘stage’ in the procedure in Table 1).

C. Implications of orders

The raison d’être of orders is to bootstrap and/or shorten procedures without compromising their fairness or frustrating the rights of the parties.Footnote 82 Three criteria, the length of proceedings, the impact on deliberation and the effect on centralisation, directly address this trade-off.

The length of proceedings indicates whether and how the order affects the length of the procedure. For instance, an order of the President to process the preliminary reference in the urgent procedure shortens the proceedings. Similarly, an order deciding to join cases increases efficiency by treating two cases as one (solving two disputes in one procedure). Not all orders that increase efficiency have the same implications for the rights of the parties and, potentially, for the substance of the case. Additional criteria are necessary to measure this effect.

The impact of an order on deliberation refers to the effect of that order on the participation of different actors in the decision-making process. Orders to dispense with the opinion of the Advocate General or the oral proceedings decrease deliberation and participation. Orders on the merits in the preliminary reference procedure effectively exclude most actors, including the Advocate General, from the decision-making.Footnote 83

Finally, centralisation is often associated with cost-cutting and efficiency.Footnote 84 The criterion refers to the effect of the order on the concentration of the decision-making in one or more units of the Court, meaning the Cabinet of the President and the units under her supervision. For instance, an order of the President to reply to a preliminary reference by a reasoned order shortens the proceedings delegating the ‘judgement’ to the administrative units and the Cabinet of the President. It partially excludes the members of the Court from deliberation on the merits of the case.

4. A map and the territory of orders

This Section explains the mapping process (the empirical analysis) of orders and outlines the patterns of their use. The quantitative analysis is based on the taxonomy developed in Section 3. It shows that the Court most commonly uses orders that shorten the proceedings. Those orders also condense the deliberation phase in preliminary reference procedures, appeals, and direct actions, limiting the participation of the members of the Court (Judges and Advocates General), the parties and other actors (like the referring courts). Moreover, the Court has been more frequently resorting to procedural orders and orders on the merits, which involve the Cabinet of the President of the Court, and the Registry and the Research and Documentation Unit (DRD).

A. The mapping process

The mapping of the Court’s practice proceeds on the basis of an automated search. This means that an algorithm parses the documents containing orders, searching for references to the Articles of the RoP,Footnote 85 common expressions associated with different types of orders in the operative part (the Court’s decision) and the keywords corresponding to the individual provisions of the RoP.

By way of illustration, the automated search can identify an order that declares an action inadmissible in three ways. First, it identifies a reference to an article of the RoP or the legal basis of the order. In the example, the Court will almost certainly refer to Article 53(2) RoP. Second, the search locates the operative part of the decision, which typically repeats the relevant text of the same Article. In this example, it will locate the phase that ‘the Court has no jurisdiction to hear the case or that the request for the preliminary reference is manifestly inadmissible.’Footnote 86 Third, the algorithm searches for the keywords in the document that identify the order, in this case the admissibility of preliminary reference. The keywords are, as mentioned, attached to the document and available on the website of the Court.

Combining these three approaches, the automated search accurately classifies nine out of ten orders, irrespective of possible occasional discrepancies between the documents. Further, the method is impervious to the Court’s inconsistent use of terminology, a problem often cited in the literature.Footnote 87 The classification is also resilient to the amendments of the RoP (like the renumbering of Articles). Finally, by parsing the texts, it is possible to identify multiple orders in a single document. Some documents contain two decisions, where the second decision typically allocates costs. Thus, the method captures the number of orders rather than only the number of published documents. A caveat of the approach (as well as all other approaches relying on the analysis of legal texts) is that the Court might still issue orders without publishing them. Those orders would fall outside the scope of the analysis.

B. Orders by type and policy area

The Court’s use of orders varies greatly across time and policy areas. The most frequent orders are the orders allocating the costs in direct actions and appeals. The second most frequent orders are radiation orders, which remove the case from the Registry, typically after the referring court has withdrawn the preliminary reference. Referring courts can do so either on their own motion or when prompted by the Registry of the Court. The Registry normally addresses a communication to the referring court, inquiring whether a past decision on a similar case (usually attached to the communication) could be helpful in solving the referred question, in which case the reference is moot.Footnote 88 In the past decade, the use of radiation orders in the preliminary reference procedure has increased tenfold.Footnote 89 The third most commonly used orders are orders declaring an appeal manifestly unfounded or an action inadmissible.

The policy areas with most orders depend on the type of procedure. In direct actions, the Court most often uses orders in disputes related to agriculture and fisheries, transport, environment, and competition, followed by free movement (of services, goods, and establishment). In preliminary reference procedures, the orders in cases dealing with free movement are most common, followed by fundamental rights, consumer protection, the area of freedom, security, and justice, and social policy.

Finally, the use of individual orders differs over time. The number of orders deciding on the right of interested parties to intervene in the proceedings peaked at 79 orders in 2011. Until the eighties, those orders were highly uncommon.

C. Patterns of use

Process and substance

The primary distinction between process and substance serves as a starting point from which to draw a map of orders and explore their territory. The use of procedural orders and orders on the merits of the case is illustrated in Figure 1. Noteworthy developments, which merit further investigation, are a sharp increase of strictly procedural orders (along with an extended period of their frequent use between 2003 and 2012), a considerable rise of procedural administrative orders after 2000, and a steady rise of orders on the merits after 2005.

Figure 1. Orders on the merits and procedural orders (strictly procedural and procedural administrative) from 1975 to 2022, relative to the number or judgements.Footnote 91 A single published document can contain several orders, for instance an order deciding the appeal and an order deciding on the costs. This further implies that the three lines do not add up to the numbers of documents published, but display the total number of orders, which fit within these categories. The full drawn line shows a clear upward trend in the use of orders on the merits since the first orders of this type in the early 1990s. The use of both types of procedural orders (dotted lines) increased substantially around 2005, but has since stabilised.

Strictly procedural orders, such as interlocutory orders or orders allowing interventions, balance the procedural economy with the rights of the parties. These orders multiply when procedures grow more complex, and when cases draw the interest of the national governments and require increased awareness of the procedural steps to secure the legitimacy of the judicial process. Strictly procedural orders, such as orders to process the case in an urgent procedure, give priority to procedural economy – their main aim is to decide the case (reply to the preliminary references) without delay. To achieve a timely outcome, they minimise the input of the litigants and the interested parties, curtail procedural steps, and de facto allocate the management of the procedure to the Cabinet of the President of the Court. These specificities are important when interpreting the patterns.

Procedural administrative orders are orders to join cases, stay the proceedings, defer the decision in the case, resend the case to a larger formation, suspend the decision, or erase a preliminary reference from the Registry. They are issued by the Registry and based on the reports drafted by the administrative services under the supervision of the President of the Court.Footnote 90

Procedural administrative orders bureaucratise institutional practices, explicitly articulating and transforming them into mandatory procedural steps. Even when valid rules and regulations do not prescribe the steps, the internal rules impose them as vital for record-keeping or case tracking. Usually, they do so by introducing further written internal instructions for the processing of cases through the system. Their growing use has implications for the deliberation phase – especially for the participation of the members of the Institution. As indicated in Table 1, procedural administrative orders do not require the intervention/consultation of the Advocate General, compared to the orders on the merits (rows 1 to 5 in Table 1) and strictly procedural orders, which directly affect the (procedural) rights of the parties. It could be argued that the rise of procedural administrative orders after 2000 signals a turn to a greater bureaucratisation and dwindling participation and deliberation.

The orders on the merits are discussed separately in the fourth subsection.

Length of proceedings

Figure 2 below illustrates the Court’s frequent use of orders, which shorten the proceedings (area with slanted stripes). The development is particularly evident in the past two decades when their share has stabilised at a rather overwhelming 75–85 percent.

Figure 2. The share of orders by their effect on the length of procedures from 1975. Until 1975, the Court issued and published only a few orders. The figure shows a clear increase in the orders shortening the procedures (slanted gray area), particularly from the mid-nineties. Orders, which lengthen (prolong) the procedure have been less common since the late nineties (black area). The figure shows that these orders surged between 2004 and 1012, decreasing since. The white area indicates the orders without a clear effect on the duration of the proceedings.

The development is noteworthy given that the RoP balance the orders shortening the procedures (like orders to join cases) with orders prolonging them (like the request for documents). As shown in Table 1 (seventh column from the left), the RoP include 15 types of the former and 14 types of the latter. The effect is unclear for the remaining 12 orders. It is, however, most reasonable to assume that it is not significant, as they do not omit, simplify, or add procedural steps. The Cabinet of the President participates in nearly all orders shortening the procedures (as illustrated in Table 1).

From Table 1 it transpires that the orders shortening the procedure also limit participation and involve fewer members of the Court in the decision-making process. Almost 96 percent of the orders, which reduce the length of the proceedings, also decrease deliberation. In other words, orders decrease the length of proceedings by decreasing deliberation and centralising the decision-making (Table 1, fourth column from the right). Thus, Figure 2 also demonstrates the decrease of deliberation and the increase of centralization.

Centralisation/orders of the President

Orders of the President are a facet of centralisation – a process of institutional transformation evidenced in Figures 1 and 2 above as the use of orders shortening the procedure, the use of orders on the merits and procedural administrative orders. Figure 3 shows that the number of orders, signed by or involving the President of the Court in direct actions, grew exponentially around 2003, and that the growing trend was reversed after 2011 (bar a spike in 2018 – 2019). The trend in appeals displays a steady growth since 2000. In preliminary reference procedures, the orders of the President increased sharply after 2000 and 2008, tripling since 2011.

Figure 3. Orders signed by the President of the Court or involving the President´s Cabinet or any other service under her direct supervision by type of action (dashed line: preliminary references, straight line: direct actions, dash-and-dots line: appeals). A majority of orders of the President of the Court or involving her in the decision-making are administrative orders, others are substantive.

Content wise, in the preliminary reference procedures most orders are radiation/removal from the Registry orders, reflecting a more active role of the Registry in communicating with the national courts, as well as the orders of the President exercising emergency powers. Regarding direct actions, most orders are applications for interventions related to the disputes concerning the environment.

The upward trend partly coincides with the amendments to the RoP in 2000 and 2008, which introduced the so-called emergency powers.Footnote 92 According to Articles 105 and 107 RoP, the President can issue orders to process the case in an expedited (accelerated) or urgent procedure.Footnote 93 Expedited procedures shorten the written part of the procedure by limiting the number of participants who can submit written pleadings or omits written pleadings altogether. Urgent procedures, used to deal with the reference in the area of freedom, security, and justice, can dispense with both if merited by the circumstances of the case – meaning urgency. They were introduced when asylum cases, often requiring swift handling, began to crowd out pressing references in other policy fields. To ensure equal treatment of cases, the RoP separated the two procedures and introduced a greater discretion/more procedural flexibility into the urgent procedure.

On the one hand, scholars have argued that the President’s power to assign cases to reporting judges – and the possibility to use this power strategically – has positive implications for the Court’s relationship with Member States’ governments and compliance rates.Footnote 94 Reporting judges, who are perceived as neutral by the litigants (including national governments), can increase the legitimacy of the process and the acceptability of the ruling. On the other hand, the practice leads to specialisation and disproportionate influence of individual judges on the deliberation in the Chambers.Footnote 95 The problem is obvious especially in the context of non-permanent Chambers, which persist despite the Court’s non-hierarchical organisation compared to other higher national courts.Footnote 96 In this context, the allocation of cases by the President of the Court can result in institutional asymmetries, increasing her power to influence legal developments.

Orders on the merits

Figure 4 demonstrates the use orders on the merits. These are orders to dismiss an appeal against the decision of the General Court as manifestly unfounded, orders to dismiss an appeal against the decision of the General Court deciding on the decision of the Board of Appeals (Article 170 bis RoP), and orders issued in reply to preliminary references. While the use of all has expanded, the growth has been greatest for the latter two. The use of these orders increases centralisation, involving the administrative units of the Court, particularly the Cabinet of the President, the DRD, and the Registry. Figure 4 thus suggests a growing centralisation and a greater role of the Cabinet of the President in the decision-making process.

Figure 4. Orders on the merits over time: orders on the merits in the preliminary reference procedure (Article 99 RoP), orders to declare an appeal manifestly unfounded (181 RoP) or to dismiss appeals against the General Court’s rulings on the decision of the Boards of Appeals (Article 170 bis RoP). The use of all orders on merits has increased, but mostly for orders declaring an appeal manifestly unfounded, and orders of Article 170 bis. Not visible on the figure are orders declaring appeals manifestly well-founded (Article 182 RoP): the first such order was published in 2019 (Case C-58/19 P), and two related orders were published on the same date in early 2022 (C-663/20 P and C-664/20 P).

The patterns of use, illustrated above, coincide with procedural reforms. In 2000, the RoP introduced the option to reply to a preliminary reference with a reasoned order ‘where the answer to such a question may be clearly deduced from existing case-law and where the answer to the question admits of no reasonable doubt.’Footnote 97 The use of orders on the merits surged. In 2005, a second amendment to the RoP relaxed those procedural requirements,Footnote 98 except in cases where the answer admitted no reasonable doubt. The reform in 2010 eliminated the last procedural constraints. The use of those orders rose in both instances, as illustrated in Figure 4.

By comparison, the amendments of the RoP, which introduced new procedures or orders, but maintained the requirements of participation and deliberation, did not trigger an increase of those procedures or orders. This suggests that efficiency motivates the practice. The RoP in 1991, for instance, stipulated a possibility to issue an order ‘[w]here a question referred to the Court for a preliminary ruling was manifestly identical to a question on which the Court has already ruled’.Footnote 99 The Court had to inform the referring court, consider all submitted observations, and consult the written Opinion of the Advocate General.Footnote 100 The constraints were not trivial, which might explain why the Court rarely used them, and why by the end of the 1990s the number of pending references became ‘the most pressing issue’.Footnote 101

Finally, the upward trend for Article 170 bis orders is related to the amendments to the RoP in 2019, which introduced the possibility to issue orders in the appeals against the judgements of the General Court concerning the decisions of selected independent Boards of Appeal (BoA).Footnote 102, Footnote 103 The Court will issue such orders by default, that is, unless the appeal ‘raises an issue that is significant with respect to the unity, consistency or development of Union law’ (Article 170 bis RoP).Footnote 104 Since the provision was added to the RoP in 2019, the Court has issued 125 orders rejecting the requests to proceed with the appeal, and only one order in which the appeal was allowed to proceed (interestingly, the only case so far in which an EU body, the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), was the appellant and not the defendant).Footnote 105 Figure 4 illustrates this development.

5. The blurred lines between judging and administration: causes and consequences

This Section explains that the use of orders reflects the Court’s strife for productivity and the desire to oversee the application of rules. To be clear, there are convincing reasons to insist on both. Greater productivity delivers timely justice, outwardly legitimising the institution. Control can secure and promote the uniform application of European Union law and the protection of individual rights.Footnote 106 Both are indispensable for the institution seeking to manage an efficient justice system and maintain exclusive interpretive authority under the Treaty (Article 267 TFEU).

Greater productivity, timely justice, uniform application, and exclusive interpretation, however, seem difficult to pursue together, clashing with competing and equally desirable and legitimating attributes of the judicial process: the quality of the legal argument, a constructive judicial dialogue, fair procedures, the right to be heard. … There is little reason to question the purity of the Court’s stated motive to deliver timely justice of excellent quality in a cordial spirit of cooperation with national courts.Footnote 107 Inasmuch as those call for broad participation, extensive deliberation, incalculable logistics and organisation, they undermine procedural economy. Inasmuch as a shared responsibility for the development of law potentially enables the Court to focus on a handful of most legally interesting matters of general importance, it also challenges its interpretive monopoly and uniform interpretation.

The use of orders offers valuable insight into how the Court reconciles the conflicting demands. No other procedural instrument is so intimately linked to procedural economy and yet so often missing from the discussion. The history of procedural reforms and the Internal Guidelines of the Court exposes the peculiarity/uniqueness of the European approach. Together, they show that the Court delegates judicial tasks to the Cabinet of the President and the administrative support units. This has far-reaching normative and institutional implications in the context where the President has – compared to other international courts – the exclusive right to allocate cases to the reporting judges or allocate judges in Chambers as she sees fit, potentially pre-empting case outcomes.Footnote 108

In the current institutional context, delegation leads to the centralisation of the institution and the bureaucratisation of judging. Orders, issues in reply to preliminary references or solving appeals, illustrate and support this conclusion.

A. Motivation: Full oversight without delay

The Court’s ambition to preserve its interpretive monopoly and full control transpires through each reorganisation of the preliminary reference procedure, leaving national courts aside, and otherwise limiting participation. The gradual implementation of practices attests to the changing priorities and the power of the Court to formalise them in the RoP.

The amendments (Figure 4) have altered the division of labor. Speaking on the future of the European Union’s Justice System in 2006, President Skouris noted that the referring judge would have to submit ‘better drafted references’ demonstrating that ‘his knowledge and awareness in terms of European law have increased.’Footnote 109 The national judge, however, would not acquire a more important role in the interpretation of European Union law. The intention of the 2005 reform was decisively not to make the national courts ‘better placed to give informed decisions on a growing number of questions of Community law’,Footnote 110 but to reduce delays, which the Court seemed to attribute to a combination of legally uninteresting questions and multilingualism.Footnote 111 Post reforms, national judges were no longer aware of the possibility of an order until receiving one.

The weeding of preliminary references can efficiently tackle the bottlenecks caused by unwarranted litigation. The practice sits uncomfortably with the demanding CILFIT criteria.Footnote 112 The analogy might seem odd, but less so when one thinks of the practice of orders in terms of broad control over interpretation and uniform application, and an inverted acte clair.Footnote 113 To recall, CILFIT concerned the question whether the national courts of last instance had to refer questions of interpretation under Article 267 TFEU even if the correct interpretation (and application) of Community law was ‘so obvious as to leave no scope for any reasonable doubt as to the manner in which the question raised is to be resolved’.Footnote 114 The Court established a high threshold that few courts of last instance met in practice. The criteria that the national court had to be convinced that the matter was ‘equally obvious’ to other national courts and to the Court was particularly demanding and hypothetical. By comparison, the Court never established corresponding criteria for the application of Article 99 RoP.Footnote 115

The standard of ‘no scope for reasonable doubt’ sounds similar, except that acte clair leaves the decision of legal relevance to the referring courts, and Article 99 RoP negates the soundness of their judgement. The double standard signals distrust in the ability and responsibility of national courts. The arrangement, probably justified occasionally, functions more like – in the vernacular of apps and tablets – parental controls. Experts understand that it invites detached cooperation at best.

Orders on the merits in the preliminary reference procedure might not drastically affect the Court’s relation with the national courts, but they disrupt the participation of the parties to the proceedings. The Court seems aware but not excessively concerned. In the explanatory note to the proposal for amendment of the RoP in 2005, which sought to relax the criteria to reply to a preliminary refer,ence by an order, the Court argued that the obligation to hear the parties and the referring judge had no useful purpose and merely held up the decision by a month and a half.Footnote 116 The observations, the Court explained, ‘d[id] no more than repeat the arguments previously put forward by the party in question during the written procedure’.

The amendments in 2011 responded to the same justification and showed equally little interest in ensuring the participation of the parties. In its explanatory note, the Court repeated that the parties’ opportunity to submit written observations on the Court’s intention to rule by reasoned order in cases in which the reference ‘offered no reasonable doubt’ was ‘often synonymous with a significant increase in the workload of one or other party’. The litigants and other participants in the procedure tended to reproduce the content of their earlier written observations, requiring translation. The latter caused a delay of several months, prompting the Court ‘to choose to rule by way of a judgement delivered without a hearing and without an Opinion, instead of by order’.Footnote 117 The fourth modification of the RoP in 2012 entirely removed the obligation to hear (or notify) the parties and inform the referring court of its intention.Footnote 118

Second, those appealing the decision of the General Court pursuant to Article 170 bis RoP must satisfy a further condition and demonstrate the ‘significance of the issue raised by the appeal with respect to the unity, consistency or development of EU law’.Footnote 119 The Court can dismiss appeals, which do not meet the threshold, with an order, and focus on questions that it considers novel and relevant (interesting). The aim of the provision was to discourage certain type of appeals,Footnote 120 and reduce their number overall.Footnote 121 The frequency of those orders shows that the Court accepts a negligible number of appeals (Figure 4). The option is a reminder of who has the final word more than a remedy – to request the legality review of administrative decisions. Given that the Court declares almost all appeals unfounded, an appeal to an extended Grand Chamber or the Plenary of the General Court might present a more efficient solution.

B. Implications: Centralisation and bureaucratisation

The increase of procedural orders, especially procedural administrative orders, and orders on the merits suggests a parallel increase in the bureaucratisation of the decision-making and the centralisation within the institution. It is related to the involvement of the President’s Cabinet and the DRD in the process.

Delegation of judicial work to non-judicial (administrative) support units, particularly the Registry and the DRD, which is composed of national experts, increases judicial productivity, unburdening the Judges and the clerks. The new division of labor increases the influence of the President.Footnote 122 The task of the support units is to screen for (un)important legal issues and draft the decisions. The Court’s Internal Guidelines confirm this understanding of the patterns.Footnote 123 The following four examples are illustrative.

First, the most obvious example are the emergency powers. The President can decide on its own motion or at the request of the referring court to process the case in an expedited procedure (Article 105 RoP). The President might also ask the designated Chamber to consider whether it is necessary to proceed according to the rules of the urgent preliminary reference procedure (Article 107 RoP). The decision to use the emergency powers is an order, which omits (substantial) procedural steps. The President can request that the parties ‘restrict the matters addressed in their written observations to the essential points of law raised by the request for a preliminary ruling’ and even prescribe a ‘maximum length of those documents’ in the urgent procedure. In extreme urgency, the Chamber can decide to omit the written part entirely (Article 111 RoP). Figure 3 showed an increased use of emergency powers since their addition to the RoP.

Second, in appeals involving intellectual property, public procurement, access to documents and staff cases, the DRD (which reports to the President) indicates whether the Court could issue an order pursuant to Article 181 RoP (manifestly unfounded appeal) or whether the appeal should proceed, as it raises a ‘significant issue’ (Article 170 bis RoP). If the DRD believes that the case meets the criteria for an order, it already drafts the order and attaches that draft to the file.Footnote 124 In parallel, the Registry (which also reports to the President´s Cabinet)Footnote 125 conducts a preliminary analysis of the case to facilitate the assignment to the reporting judge (by the President). This so-called fiche objet signals a quick solution.Footnote 126 Figure 4 shows that since the introduction of Article 170 bis, the Court solved nearly all appeals with an order.

Third, if the DRD and the Registry indicate a possibility to decide by an order in the general appeals procedure (Article 181 RoP),Footnote 127 the Judges will discuss the merits of the appeal in a general meeting only at the explicit request of at least one member of the Court. Otherwise, the Advocate General will draft an Opinion that the reporting Judge will reproduce in her draft.Footnote 128 According to Articles 181, 182 and 170 bis RoP, the Court can declare an appeal manifestly unfounded or inadmissible, manifestly well-founded or lacking legal interest, and decide with an order without involving the parties. In the absence of their submissions, the preliminary analysis (fiche objet), drafted by the DRD, is the sole reference. Figure 4 shows a steady increase in the use of those orders, particularly after 2010. This is consequential because the members of the Court and the parties have no say in the process. While this applies to the orders issued in preliminary reference procedures and appeals, it is not equally conclusive. The parties can request (at least in theory) a second reference from the national court in the same procedure.Footnote 129 Appeals, on the contrary, exclude this option per definition.

Fourth, in the preliminary reference procedures, the President influences the decision to issue an order formally and informally. Formally, the President receives the preliminary analysis of the DRD, highlighting the possibility to reply by an order and a draft of the decision,Footnote 130 before assigning the case to the reporting judge. Informally, she might assign the case with the possibility of a reply by an order in mind, gaining influence that exceeds the formal power inherent in the attribution of cases.Footnote 131 If in agreement to reply to the reference with an order, the reporting judge might propose to inquire whether the national court wishes to maintain the reference. The communication is subject to the President’s approval.Footnote 132 The Court makes a formal decision to reply by an order, based on the preliminary report of the reporting judge,Footnote 133 at the general meeting.

6. Conclusion

What do the Court’s orders reveal about the decision-making routines, the institutional priorities and transformations? So far, these have remained impressionistic owing much to the absolute secrecy of deliberation.Footnote 134

The article replied to this question by systematising 42 types of orders and mapping their use. The analysis reveals a growing use of orders, which increase the Court’s output, like orders on the merits in direct actions, preliminary reference procedures, and appeals, or orders deciding to process cases in urgent and accelerated procedures. Institutionally, these orders strengthen the role of the Registry, delegate judicial tasks to the administrative support units, like the DRD, and fortify the position of the President’s Cabinet. While the efficient handling of cases reduces delays and disposes of the backlog, it also centralises the decision-making and bureaucratises the institution. In this way, orders contribute to the blurring of lines between judging and administration.

The patterns reflect the Court’s strife to remain in control over the European judicial system without buckling under increasing demand. They also imply that the Court is prepared to forego participation and short-circuit deliberation to increase its output. In other words, the Court seeks to demonstrate that it can deliver timely justice and oversee the development of all aspects of European Union law.

The conclusions of the analysis, highlighted below, are primarily relevant to the study of European Union law and institutions. They should resonate with all judicial institutions without direct control over their dockets and the scope of their jurisdiction, but with powerful figures at the helm, substantive institutional autonomy, and a decisive say in the administration of procedures.Footnote 135

Yet, the situation of the Court is unique. The Court designs its procedural framework to an extent unknown to most other high courts, which operate within tighter procedural frameworks adopted and amended by the Legislator. The internal procedural guidelines, common to courts but of diverse character, tend to govern practical and organisational matters.Footnote 136 Their content and limited availability, adding on to the closed nature of the decision-making (dissenting opinions, case allocation, and the logic of Chamber composition come to mind) does not show the Court in its most legitimate light. Additionally, the role of the President far exceeds representational duties. Orders shed light on these powers, which she exercises continuously via her Cabinet and the Registry. They tangibly affect the process of judicial decision-making (notably, a decrease in deliberation) and the institution (especially, a progressive centralisation).

The institutional transformations coincide with procedural amendments. Those were often motivated and merited by structural changes and events beyond the Court’s control. The 2004 enlargement, the budgetary crisis, and the expansion of competences, complicated by a pile of pointless preliminary references and appeals, called for a responsive organisation with a supple procedural framework, and a decisive managerial approach. Yet, all amendments carried the Court’s seal of approval, embraced its priorities, and catered to its ambitions. The Court could impose its diagnosis of the problems and the ensuing greater demands on its interlocutors without sharing the responsibility and the authority over European Union law. The diagnosis often lay in external circumstances – the clumsily drafted or repetitive references, the influx of new cases owing to several rounds of enlargement, financial or immigration crisis, the exponential increase of the membership of the institution, the broadening of its jurisdiction, and the language regime – to mention the most often debated. The Court proposed 14 piecemeal modifications of the RoP tackling those issues, subject only to qualified approval by the Council. At the same time, the Court resisted comprehensive reforms, subject to democratic debate.Footnote 137 It consciously opted for a process that it could initiate and administer with minimum transparency and reduced oversight of the Council.

Finally, yet importantly, are these developments consequential and is the problématique significant? Timely judgements cater to the interests of litigants and guarantee the stability of the legal system. Informational asymmetry and effective application of rules speak in favor of institutional autonomy and heavy involvement of the Court in procedural reforms. Importantly, the Court must internalise the RoP to apply them effectively, and it knows best how to conduct its proceedings and organise the workflow. Financially, fewer resources and better performance are preferable. These are non-negligible benefits of efficiency driven reforms.

The European Union lacks a general procedural code, and the RoP assume this role. In this context, the RoP should not be crafted behind closed doors, nor practiced according to internal guidelines, inaccessible to outsiders. This is, alas, the case. The Council routinely seconds the Court’s perception of reality, its (often-unverifiable) diagnosis of the challenges of the justice system, and a mixed bag of remedies. The practice creates a sense of obscurity around the Court’s institutional practices and the management of procedures. Safeguarding the rule of law and order(s), however, calls for constructive engagement with the legislator and the legal actors. It begins with a guided tour of the engine room and a conversation about its maintenance.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the anonymous reviewers, to Claire Kilpatrick, Martijn Hesselink, Nicolas Petit, and other colleagues at the European University Institute. We are grateful to the Danish and the Swedish Council for Independent Research for their generous financial support.

Competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.