Introduction

For decades scholars have examined how foreigners who migrate and settle into a new society subjectively transform through acculturation, assimilation, incorporation, or integration. These processes are analogous to other micro-level socialization processes, like becoming a member of a family, political party, religion, or company. Yet just as individuals painfully adjust their identities to the sudden loss of a relationship [Vaughan Reference Vaughan1986], job [Gabriel, Gray and Goregaokar Reference Gabriel, Gray and Goregaokar2013], religious faith, [Zuckerman Reference Zuckerman2015], or loyalty to a political party [Barnfield and Bale Reference Barnfield and Bale2022], many potential immigrants go through a parallel process in deciding to give up their former plans to immigrate.Footnote 1

Just how often do potential immigrants give up immigrating? A study in the United States (hereafter the US) found that 37.5% of the 400,000 who legally immigrated to the US later returned to their country of citizenship [Keely and Kraly Reference Keely and Kraly1978]. Jasso and Rosenzweig [Reference Jasso and Rosenzweig1982] note based on U.S. Census data that around a third of foreign nationals that immigrated the United States between 1908 and 1957 later gave up on immigrating. With complete data for the entire cohort who arrived in the US and began the process of legal immigration in the fiscal year of 1971, they found that by 1979 as many as half of them had quit immigrating and emigrated from the United States. This varied substantially by nationality, with 72% of South Americans, 69.5% of Central Americans, 39.8% of Indians, 38.6% of Cubans, and 12.2% of Chinese changing their mind about immigrating during this 8-year period and emigrating from the United States. Hence, even for Chinese citizens, whose society of origin was far away and then challenging and difficult to return to, resettle, and live in, potential immigrants giving up the opportunity to immigrate has been a century-long phenomenon and not as rare as many may believe. More recently, 20-50% of prospective migrants abandoned high-income per capita countries within 5 years of arrival. They generally left before their permits expired [OECD 2008, 2019]. Since most migration scholars reside in migrant-receiving societies, they often study immigration by collecting and analyzing data from immigrants rather than those previously aspired to immigrate but later returned to their country of immigrant origin–a group I will hereafter refer to as ex-immigrants. Due to this, we arguably know much more about the process through which foreign nationals become immigrants than how previously aspiring immigrants become ex-immigrants. We can potentially enrich our understanding of immigration by studying the social forces and experiences that constitute the subjectivityFootnote 2 of these ex-immigrants.

As illustrated in Figure 1, with respect to migrant intentionality and behavior over time, ex-immigrants are a specific sub-class of return migrants who had previously intended to immigrate but later decided not to do so and to instead return to their country of origin. They are distinct from another sub-class of return migrants who had always planned to return to their country of origin, a sub-class that governments and scholars refer to as “non-immigrants,” temporary immigrants, or sojourners. The observed behavior of non-immigrants who never intended to migrate and ex-immigrants who give up immigrating is identical (return migration). However, their migration experience is subjectively distinct because an ex-immigrant’s project of migration changes over time. If a person intends to return to their country after some years and does so, their migration project remains the same. Ex-immigrants are also substantively important as a sub-class of return migrants because their decision to return to their country of origin is partly a product of their subjective experience with social forces in the migrant-receiving society. In contrast, those return migrants who had always intended to return to their country of origin do not change their identity from that of a prospective immigrant to that of a return migrant. The social forces behind this change in a prospective identity are of theoretical importance for how we counterfactually and critically think about those return migrants who may have immigrated if their social experience in the migrant-receiving country had been different. This study therefore contributes to past research programs about the “contexts of reception” that immigrants confront [Luthra, Soehl and Waldinger Reference Luthra, Soehl and Waldinger2018] by highlighting the social forces that lead immigrants to give up immigrating. Return migrants are also distinct from immigrants and those called transnational migrants, trans-migrants, or dual nationals, which research suggests are typically first-generation or second-generation immigrants who divide their lives between their migrant-host society and their migrant-origin society [Waldinger Reference Waldinger2015].

Figure 1 Diagram of Migrant Classes

Ex-immigrants are of substantive interest to both scholars and policymakers because 1) many prospective immigrants are the types of individuals that governments, employers, and society in migrant-receiving societies hope will transition to an immigrant visa and immigrate, and 2) migrant-receiving societies that would benefit from the presence and contribution of such prospective immigrants also suffer a loss if they choose not to immigrate. Although many scholars based in migrant-receiving societies have had opportunities to observe and study those who did not intend to immigrate but eventually ended up immigrating, scholars have not paid nearly as much attention to ex-immigrants who seem to represent an equally important change in intentionality. More knowledge about ex-immigrants would nonetheless be an illuminating complement to the abundant discoveries scholars have already made about immigrants as this would provide a stronger point of comparison and help us to more deeply understand international migration and migrant selectivity. If the proportion of prospective immigrants who give up on immigrating is as the aforementioned demographic studies suggest, then ex-immigrants are also consequential for the demographic size and composition of immigrant-receiving societies and of greater analytical interest to such societies and their policymakers than those return migrants who never intend to immigrate.

Acknowledging how the intentionality of a return migrant changes due to social forces is also a way of respecting the autonomy of a prospective immigrant to give up on immigrating, inviting analysis into the social forces and social experiences that structure this choice. If we do not analytically distinguish between those who always intended to return and those who did not, we will be unable to distinguish between those who might have immigrated if they had had a better experience in migrant-receiving countries and those who would never have immigrated no matter what their experience was. This analytical distinction helps migrant-receiving societies to come to terms with the consequences of how social forces discourage intending immigrants from immigrating.

Much past qualitative research about “return migrants” tends to focus on “non-immigrants” who never intended to immigrate or settle down [Waters Reference Waters2008], like students whose parents encourage them to study abroad so they can return and have a better life in their country of origin [Tong, Persons and Harris Reference Tong, Persons and Harris2019]. The New Economics of Labor Migration model of migration [Stark and Bloom Reference Stark and Bloom1985] assumes that after a migrant has earned and saved a certain minimum target of financial resources through work, they would return to their country of origin. Yet since prospective immigrants have agency, they can also certainly change their minds about immigrating due to their social experiences in the migrant-receiving society. Failing to analytically distinguish between “return migrants” who intended to return and “ex-immigrants” who gave up immigrating would assume that all return migrants consistently and strategically follow the New Economics of Labor Migration model. We can learn more than we have from the above literature if we analyze the diverse social processes by which those who intended to immigrate ultimately gave up on immigrating.

If attractive opportunities exist in a migrant’s society of origin, social forces in the prospective immigrant’s host society may lead those who previously aspired to immigrate to renounce immigrating voluntarily. Such forces gradually disenchant them with respect to the idea that they will have a better life by immigrating—an idea I will generally refer to in this paper as “the immigrant dream”. If the intensity of migrant suffering and uncertainty about their current situation and future becomes much greater than they believed it would be in their country of origin, immigrants will reasonably begin to question or doubt whether migrating will indeed make their life any better. Formerly aspiring immigrants will initially become ambivalent about their prospects and eventually decide to cut whatever losses they have invested in the migratory project. Thus, ex-immigrants are both “exceptional cases” [Ermakoff Reference Ermakoff2014] and “negative cases” [Emigh Reference Emigh1997] of what migration scholars more often study—immigrants. Knowledge about ex-immigrants can help us more fully and richly understand the challenges of immigration and how giving up an identity as an immigrant is analogous to but also distinct from micro-level transformations of subjective identity in other domains of social life.

Past Research on Why Ex-Immigrants Give Up on Immigrating

Given the large numbers of Chinese migrants in many migrant-receiving countries worldwide, mainland Chinese ex-immigrants are a contextually special and quantitatively consequential case of the general ex-immigrant. China’s rapid economic growth has motivated many migrants to return to China in the 21st century. However, China’s periodic tightening of political restrictions has also provoked anxiety among citizens about returning. Therefore, my findings from this study are probably most generalizable to ex-immigrants who originate in other autocratic societies that have also seen a rise in material living standards.

Becoming an ex-immigrant is a case of the more general phenomenon of transformations in an individual’s subjective social identity. Like marriage, taking a new job, buying a house, or becoming a member of an important affiliative group or community, a project to immigrate is a major investment. Like giving up on these other projects, giving up on immigrating also entails associated changes in identity and social relations that can often be fraught with ambivalent emotions varying across contexts and discourses about immigration. For example, a popular and academic discourse respectively characterizes ex-immigrants from migrant-sending societies as “failures” and “negatively selective” [Borjas Reference Borjas1989: 476] in narrow terms of merely their income-generating potential in migrant-receiving economies. However, diverse social forces lead prospective immigrants to give up immigrating even if immigrating is in their economic interest, making immigration a far less determined process than suggested by rational choice theory.

Past quantitative research about such “return migrants” has focused on measuring how strongly the probability of return migration is associated with discrete migrant traits and aspects of a migrant-origin and migrant-destination society. Generally, migrants are more likely to return if the context of migrant reception is more rural [Treacy Reference Treacy2010], xenophobic, and racist; keeps migrants more spread out and unable to form networks [Basok Reference Basok2000]; and features professional associations that reject immigrants’ educational credentials [Coniglio, Arcangelis and Serlenga Reference Coniglio, De Arcangelis and Serlenga2009; Thomas-Hope Reference Thomas-Hope1999; Venturini and Villosio Reference Venturini and Villosio2008]. Migrants are also less likely to return if they can obtain a secure legal status in the destination society [Constant and Massey Reference Constant and Massey2002; Dustmann, Bentolila and Faini Reference Dustmann, Bentolila and Faini1996]. Human capital-rich (“high-skilled”) migrants often return due to a limited social network in the migrant destination society [Khoo, Hugo and McDonald Reference Khoo, Hugo and McDonald2008]. Scholars find that, compared to immigrants, return migrants also tend to be married [Zweig and Wang, Reference Zweig and Wang2013], older, remit more [Treacy Reference Treacy2010], have better information about the law and debt bondage [Liu-Farrer Reference Liu-Farrer2020], lack friends or romantic partners in the host society [Bloch et al. Reference Bloch, Sigona, Zetter, Sigona and Zetter2013], and have not culturally adapted to their host society [Carling Reference Carling2004]. Scholars disagree about whether return migration is associated with age, sex, state/province of residence in the destination country, proficiency in their host society’s language, or their earnings or occupational prestige [Constant and Massey Reference Constant and Massey2002; Hagan, Hernandez-Leon and Demonsant Reference Hagan, Hernández-León and Demonsant2015; Khoo, Hugo and McDonald Reference Khoo, Hugo and McDonald2008; Thomas Reference Thomas2008; Treacy Reference Treacy2010].

Migrants are more likely to return if their country of origin is closer, has a diverse range of economic sectors, and not much poorer than their destination [Basok Reference Basok2000]. Many migrant-origin country governments incentivize emigrants to return. Although China has specific programs to attract migrant “talents” back to the country, like the Thousand and One Talent (Youth) Program or its “green card” policy [Hao, Guo and Wang Reference Hao, Yan, Guo and Wang2017], scholars have found that these are not representative of returnees in general. Researchers have noted that such programs only target a very selective group, with around 91% consisting of male scholars and STEM scholars [Zweig, Fung and Han Reference Zweig, Fung and Han2008; Xiang Reference Xiang2011]. Most found these programs disappointing [Hao, Guo and Wang Reference Hao, Yan, Guo and Wang2017]. Male student return migrants deciding whether to return tend to be more concerned about factors affecting their future career development, like their family socio-economic status, human capital, and social networks. Female students are more concerned about social/family concerns like parental influence toward migration, belonging, and support [Lu, Zhong and Schisel Reference Lu, Zong and Schissel2009], suggesting that gender may mediate decisions to give up immigrating.

The longer migrants stay in a migrant-destination country, the less likely they are to return [King Reference King2015]. Length of stay is especially important if there is a large time zone difference with the origin country (as is often the case for migrants from China) and their jobs reduce the free time available to communicate with their origin country [Waldinger Reference Waldinger2015]. Immigrants also sometimes experience anxiety and uncertainty about making plans due to restrictive policies [Jasso Reference Jasso2011]. In sum, anti-immigrant policies and various social forces can become so frustrating that immigrants decide it is better to cut their losses and return.

Conceptualizing the Specific Social Forces Behind the Formation of Ex-Immigrant Subjectivity

Migrants’ choice to return can be as fraught with ambivalence as the initial decision to migrate. The fact that they have already incurred “sunk costs” [Arkes and Blumer Reference Arkes and Blumer1985] means that many expect them to immigrate, and they confront the powerful discursive normative power of the immigrant dream. Due to such expectations and discourse, when many ex-immigrants describe the process of giving up on immigrating in their narratives on social media platforms, they often adopt a confessional tone of discourse as they feel like they must explain their decision to audiences who expect them to continue to immigrate. Many emphasize that individuals give up immigrating due to a single social force—typically racial-ethnic discrimination [Waters Reference Waters2008; Jin Reference Jin2021] based on retrospective interviews. This does not account for other factors at play that interact with racial discrimination. Aspiring immigrants must sacrifice much emotionally, mentally, and physically in their journey, investing energy, time, and money. The decision to give up on immigrating is frequently gradual rather than sudden, and results from multiple interrelated social forces that compound each other. What types of social forces form the subjectivity of an ex-immigrant?

I hypothesize that multiple forces contribute to an ex-immigrant’s decision not to immigrate. I diagram these and the way they contribute to each other in Figure A1 of the Appendix. These forces can be divided into two different general types: adaptational challenges and macro-structural forces. In the early years of an immigrant’s arrival in the host society, immigrants’ frustration is due to adaptational challenges such as their disappointment that the society is not as they had imagined, language barriers, and cultural alienation. As immigrants become more fluent in the local language and culture, and adjust to the reality of the migrant host society, they confront an “integration paradox” [Schaeffer and Kas Reference Schaeffer and Kas2023]—they become more acutely sensitive to macro-structural forces such as racial discrimination, the intersectional difficulties of navigating unfamiliar gender norms, the durable obstacles they confront in achieving upward socio-economic mobility, and the government’s visa restrictions.

In order to derive from the narratives of ex-immigrants a broader range of social forces that interact and reinforce each other, I collected oral life history interview and social media post data from 121 middle-income to high-income ex-immigrants from 16 different countriesFootnote 3. The method of analysis was similar to the way in which previous researchers studied the narratives of low-income migrants [El Miri Reference El Miri2011; Sarkar Reference Sarkar2017]. Their narratives document how their identity as an aspiring immigrant gradually first formed from the perceptions of foreign countries during the pre-migration period of their youth and later evolved into the identity of an ex-immigrant from their migratory experiences.

During their earlier phase of migration, ex-immigrants confront social forces that represented challenges for adapting to the new society. Since I hypothesized that ex-immigrants might find their migrant-receiving society disappointing due to how it differs from their country of origin, I collected data about the ex-immigrants’ pre-migration knowledge of foreign countries to better understand their expectations and why they were disappointed with their life in the migrant-destination society.

Although visa policies of the migrant-destination government require many foreigners to typically invest much energy, money, and time within China learning the language of their host society, I hypothesize that many aspiring migrants still confront a language barrier. This makes communicating and understanding social interactions a challenge, often amplifying their boredom and frustration. It also contributes to cultural alienation.

In contrast to the strict requirements for prospective migrants’ language ability, migrant-destination governments do not have systematic methods to assess potential immigrants’ cultural adaptability. Although governments might assume that if a migrant becomes sufficiently fluent in a language they will automatically pick up the culture, I hypothesized that the difficulties in cultural adaptation are still consequential even for those who can communicate in the local language. Even in culturally similar societies like Japan, Chinese immigrants often interact more with Chinese people than with people from other ethnic backgrounds. Such homophily [McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001] contributes to their cultural alienation, loneliness, and homesickness, feeling a “lack of belonging” [Liu-Farrer Reference Liu-Farrer2020: 50], even if they have the cognitive ability to master the language in order to pass the necessary standardized language exams. This prior research reveals how such a “lack of belonging” often leads many Chinese people to return since they can immediately re-acquire a sense of belonging upon returning to China.

Even after Chinese ex-immigrants adjust to their new society’s reality, acculturate, and become more conversant in the language, a distinct set of four structural-level factors are likely to compel them to give up immigrating. While they may have initially believed that the barrier to feeling a part of their host society was related to their lack of culture, language, and adaptation to the local lifestyle, even after they overcome such adaptational challenges, they still suffer a sense of exclusion. First, I hypothesized that they are likely to more frequently attribute their exclusion to racial discrimination due to experiences of double-consciousness [Du Bois Reference Du Bois2008]. They will come to interpret this as a sign that they will always remain a cultural and ethnic outsider, no matter how hard they strive to become accepted by acquiring Western cultural and economic capital. They realize that in their country of origin they would have less reason to wonder if the way people interact with them is related to their race.

I hypothesized that this sense of exclusion will be particularly acute for those who face challenges navigating the system of gender relations in their host society and do not have a steady romantic partner [Liu-Farrer Reference Liu-Farrer2020]. However, the Chinese immigrant experience of singledom is quite gendered: for Chinese men, this can lead to particularly acute intersectional difficulties in dating and developing partnerships with and marrying native-born people [Kao, Balistreri, and Joyner Reference Kao, Balistreri and Joyner2018]. Young Chinese adults, especially women, face stronger pressures from their parents to marry and bear children at earlier ages than women in most Western societieties or Chinese men. Therefore, I hypothesized that especially for those who reach an age where they feel biologically ready to find a partner, start a family, and bear children and face social pressures to do so, many ex-immigrants see much better prospects for this in their country of origin. This will also incentivize them to return.

Many immigrants may try to cope with a sense of exclusion by working harder and increasing their socio-economic status. However, I hypothesized that this generally will not lead them to achieve a sense of belongingness. Instead, ex-immigrants will continue to confront limited upward socio-economic and cross-career mobility due to how labor markets in Western societies in the past 200 years have commodified East Asian immigrants as “alien capital” [Day Reference Day2016]. This merely serves to expand and increase the efficiency of the migrant-receiving economy’s physical and cyber infrastructure while simultaneously limiting immigrants’ capacity to contribute to the content and design of products. Immigrants’ cultural alienation and their higher propensity to interact with those in their ethnic in-group due to homophily will result in difficulties in bridging structural holes [Burt Reference Burt2018] to individuals and groups with traits different from theirs, limiting their ability to acquire satisfying jobs and other opportunities via “weak ties” [Granovetter Reference Granovetter1977: 1360]. Even if they can “culturally match” the preferences of employers [Rivera Reference Rivera2012: 1000], culturally embrace more “assertive” leadership styles that are more highly rewarded in many migrant-receiving societies than in China [Lu, Nisbett and Morris Reference Lu, Nisbett and Morris2020: 4591], and evade employers’ unconscious tendencies to typecast them via stereotype threat [Steele and Aronson Reference Steele and Aronson1995] and stereotype promise [Lee and Zhou Reference Lee and Zhou2015], employers in the labor market prefer to hire immigrants in technical careers rather than the creative and human-based careers immigrants may prefer like advertising, product design, counseling, and the arts.

In contrast, ex-immigrants learn and hear that if they return to their countries of origin with foreign degrees and work experiences, they will find far more opportunities in China to have a more fulfilling career in these latter types of industries. Due to the above factors, barriers to social-economic mobility are far more complex than simply a gap in potential career opportunities and earnings between migrant-sending and migrant-receiving countries. Other scholars with a more rational-choice orientation have assumed that return migration is driven by the same economistic mechanisms as emigration decisions [Wiesbrock Reference Wiesbrock2008]. Yet the type of “bamboo ceiling” [Lee and Zhou Reference Lee and Zhou2015] described above calls into question this framework if immigrants derive more psychic or social utility from being in a particular profession than pure monetary compensation.

Exacerbating all the factors mentioned above is the way in which the migrant-receiving society places legal constraints on employers’ ability to employ immigrants, and limits the immigrants’ choice of occupation. I hypothesized that this results in an “unfree,” constrained, or indentured labor, and forces ex-immigrants to continually spend energy, time, and money in filing immigration paperwork to maintain a certain legal status––a form of “surplus value appropriation” by government and visa brokers [Sarkar Reference Sarkar2017: 173]. This increases their uncertainty about the future, and increases the risk of making long-term investments that tie them to the migrant-host society, like purchasing a car, a mortgage on a home, or starting a business and creating jobs for the migrant-host economy.Footnote 4 In contrast, aspiring immigrants know that if they return to their society of origin, at least they will not have to regularly file paperwork and pay fees to remain legally in the country and work legally in the economy. The absence of such a constraints in their country of origin makes it appear relatively more relaxing and more economically free. For many ex-immigrants, the probability of withstanding all the above-mentioned social forces results in immigration becoming a far less likely outcome for these prospective immigrants than most migration scholars have conceptualized in the past.

Analytical Strategy

I draw upon narratives from oral histories and social media posts of 121 ex-immigrants between 2018 and 2022. Unlike many studies of human capital-rich Chinese migrants in migrant-receiving societies [Lu, Zong and Schissel Reference Lu, Zong and Schissel2009; Tu and Nehring Reference Tu and Nehring2020], I decided to sample ex-immigrants in mainland China (hereafter China) because of recurring empirical evidence of the Attitude-Behavior Consistency problem [Jerolmack and Khan Reference Jerolmack and Khan2014] in empirical research about international migration that results from the widespread over-reliance of interviewing methods: many immigrants in migrant-receiving societies claim they plan to return to their own country but never do [Al-Rasheed Reference Al-Rasheed1994], and migration scholars have also found that many of those who claim they want to emigrate never do so [Siu-Lun Reference Siu-Lun2001]. I sampled interviewees in the economically prosperous cities of Beijing, Hangzhou, and Shanghai because I ascertained from prior research [Hao et al. Reference Hao, Yan, Guo and Wang2017] and pilot fieldwork that most return Chinese migrants settled in such cities rather than their hometowns in order to have a lifestyle that is relatively “freer”, less traditional, and more amenity-rich. Return migrants also frequently prefer to work in service occupations (e.g. finance, tutoring, translation services, information technology, education). Such jobs are more plentiful in these cities than in less urban areas.

I recruited citizens of the People’s Republic of China (PRC, hereafter China) into the study if they had gone abroad to a foreign country and had hoped to immigrate to that country. I excluded anyone from the sample who naturalized or acquired foreign citizenship, as China does not permit its citizens to hold dual nationality. I recruited seed participants from WeChat groups and Western social media applications, websites, and social media communities made up of many ex-immigrants. For example, people that have lived abroad tend to be overrepresented in specific cyber-communities such as those for US university alumni and entrepreneurs. I would often attend their social events which usually function as sources of elite status and social distinction for participants. I found it relatively easy to enter these spaces and interact with participants given my past attendance at selective educational institutions and identity as a White American. Communicating in both English and Mandarin, I was able to recruit and network with people who had been abroad, meeting many people through websites such as Couchsurfing and MeetMe which are more popular in the West and are accessible from behind China’s strong internet firewall via a Virtual Proxy Network (VPN). These Western sites were only visited by a minority of the population who know about them in part because they had migrated outside of mainland China.

I concluded that biographically contextualized oral-history interviews were the most practical and appropriate primary method for tracking these shifts from the identity of an immigrant to that of an ex-immigrant. I supplemented this with additional narrative data from social media posts by some of the ex-immigrants on websites such as Xiaohongshu, Zhihu, WeChat, and Bilibili, which contained demographic data and accounts of their experiences shortly after they occurred. They were therefore not as prone to recall bias and reconstructive memory as the retrospective interviews [Loftus and Palmer Reference Loftus and Palmer1974]. I interviewed both in Mandarin and English according to the interviewee’s preference. I translated oral history interview transcripts and social media posts in Mandarin to English.

Despite my efforts to field-test, compose and ask questions in culturally and linguistically appropriate ways, my positionality as a White US-citizen male researcher inevitably introduced both advantages and disadvantages for data collection. I reflexively learned that many Chinese ex-immigrants were favorably prejudiced toward someone of my race, which may have aided me at the recruitment stage. However, I was concerned as an American that participants might be reserved or reluctant about revealing negative opinions of the United States and immigration countries. Some may have developed certain nationalistic and antagonistic feelings toward the US and other Western societies due to their negative experiences abroad. Fortunately, I had previously traveled widely throughout all the migrant-destination countries they mentioned and every province of China. Mentioning my familiarity with these places may have helped me effectively establish stronger rapport, and encouraged participants to be more open about their experiences.

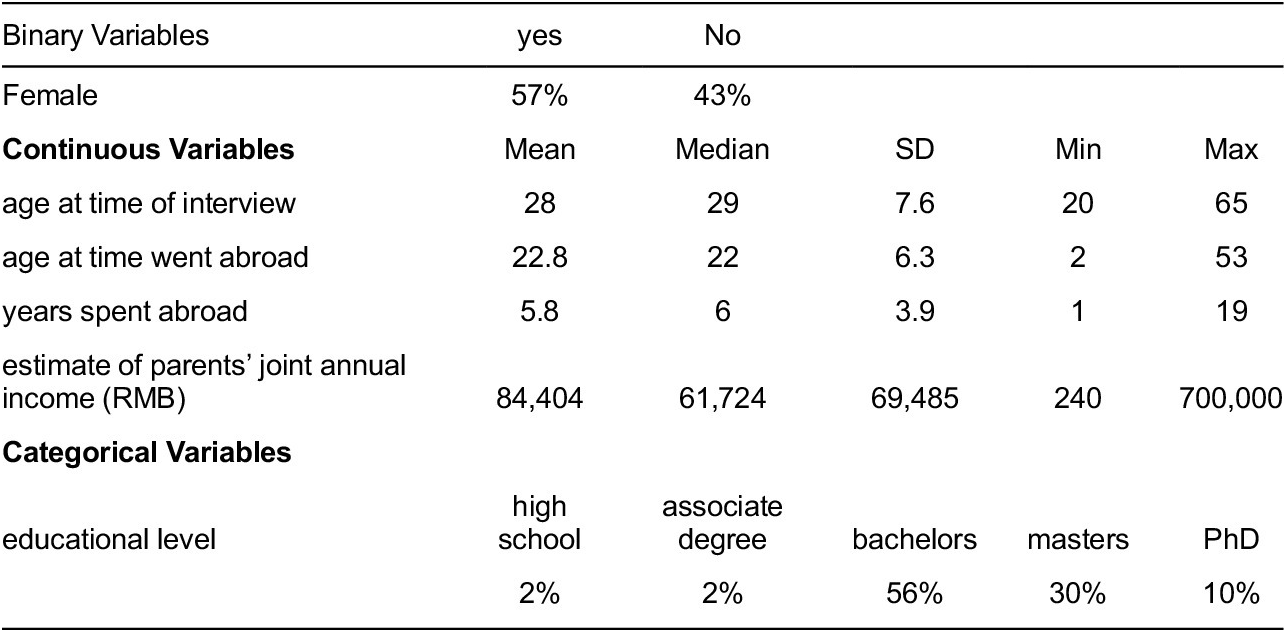

Table 1 includes relevant summary statistics of my sample for their sex, their age at the time of the interview, age at the time they migrated abroad, the number of years they spent abroad, the distribution of educational attainment of all participants, and their parents’ joint income in Chinese renminbi (RMB). Participants were roughly divided between men and women. All participants migrated legally. US immigration policy is highly selective in admitting those with superior educational attainment and socio-economic resources than the median citizen within mainland China. They were therefore mostly middle- to upper-class by the standards of China’s society. Most participants at the time of the interview had attained either an undergraduate or graduate degree. Although the income of parents may be a relevant factor, most people in China are reluctant to disclose or even calculate their income: income in China comes from many grey sources, and children do not even learn of their parent’s income. Therefore, if I could not obtain income data, I computed income figures by linking data I collected about parents’ occupation, data on pay by economic sector from the PRC’s National Bureau of Statistics, Pew Research Center, Statista, and the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. That data confirmed that most ex-immigrants had parents who earned above the median monthly income in Mainland China. In the Appendix, Figure A2 shows the percentage of individuals who went to the 9 most frequently visited countries and all the others

Table 1 Means, Medians Standard Deviations, Maxima and Minima of Key Variables, N=121

The mean age of when an individual went abroad was 22.8 years old. Most cases were within 6 years of this mean, with only a few outliers in the distribution. The mean number of years they spent abroad before giving up immigrating was 6 years, with most being abroad for 2 to 10 years. This would explain why by the time I interviewed many ex-immigrants they were, on average, 28 years old and most were between the ages of 20 and 36. Over 50% of ex-immigrants had acquired overseas full-time work experience ranging from one year to more than 6 years before returning, a result similar to that of previous large-scale surveys of high-skilled return migrants like the Center for China and Globalization’s Report on Employment & Entrepreneurship of Chinese Returnees 2017 [Tu and Nehring Reference Tu and Nehring2020]. However, in most previous extensive studies of Chinese returnees, the bulk of individuals had academic backgrounds in STEM subjects and worked in next-generation information technology, biological engineering, and the pharmaceutical industry [Wang and Bao Reference Wang and Bao2015]. In contrast, participants in my study had a higher diversity in academic backgrounds and occupations, including many who work in cultural industries, government, and finance. A few participants came to the US before they were 13, and some had lived most of their lives in the country of immigration (1.5 generation immigrants) before they gave up immigrating. A few older participants were fortunate to be among the few that went abroad in the 1980s or in the 1990s soon after Deng Xiaoping allowed more of China’s citizens to acquire passports and go abroad. They therefore spent many years abroad. However, most went abroad to study for either an undergraduate or graduate degree after China’s government liberalized its passport laws and joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, with sudden economic growth providing people with more financial resources to go abroad. At the least, the median interviewee both attended a higher education institution for a 4-year degree and worked for one to two years—typically in their 20s—before they gave up immigrating. Their parents at the time they went abroad had an average income of 84,404 RMB though this varied greatly depending on the year they migrated: a few who migrated in the 1980s or 1990s had parents with substantially lower incomes than most participants who migrated more recently.

I designed my interview schedule—included in the Supplementary Material file—in such a way that did not probe or solicit the factors I had hypothesized. Rather, I only asked participants to share their life history with me in order to see which social forces they mentioned, particularly with respect to how they perceived a society other than their own and their experiences as a migrant. I then inductively coded their raw narratives to search for the most frequently mentioned factors forming ex-immigrant subjectivity. Figure 2 shows the frequency of each factor that emerged in the ex-immigrants’ narratives. None of my questions prompted them to mention any specific factor. As we can observe, cultural alienation was the most common theme to emerge, followed by similar percentages referring to a disappointment with the lifestyle of the host-country and barriers to socio-economic mobility. Somewhat fewer participants mentioned language barriers, visa barriers, and racial-ethnic discrimination.

Figure 2 Frequency of Hypothesized Factors Mentioned by Ex-Immigrants as Formative of their Ex-Immigrant Subjectivity

Since much of a participant’s experience abroad as an ex-immigrant is related to their pre-immigration life, I began my interviews in the context of their childhood and upbringing, asking how and what they first learned about and perceived with respect to other countries, and how those ideas changed as they grew older. This had the methodological benefit of encouraging participants to gain more distance in how they viewed the current state of their lives, share experiences, and be more thoughtful, reflective, and aware of how they changed over time as they aged. That was preferable to them merely explaining and rationalizing retrospectively to me why they gave up immigrating as is the habit among interviewees who do not receive any interviewer guidance. This approach also helped guard against problems that qualitative methodologists report encountering with Chinese interviewees—which are arguably applicable to all interviewees—such as 1) the tendency to search for the “correct answer” to open-ended questions; 2) the wish to move on to the next question rather than elaborate and reflect upon their answer; and 3) a tendency to talk about abstract examples or offer general explanations rather than describing specific experiences from their own lives [Gustafsson, Blanchin and Li Reference Gustafsson, Hes, Blanchin and Li2016]. Where possible, I followed up with many interviewees and allowed them to amend what they had previously told me.

No ex-immigrant regretted going abroad—even though some wished they had returned earlier and not wasted so much time outside of China. Participants often reflected on how their migratory experience transformed them into a citizen of China who—compared to their non-migrant compatriots––was more happy, independent, self-aware, open-minded, and appreciative of different lifestyles and choices available to them. They were also more objective in their view of the differences between China and other societies, particularly in recognizing that China was not as bad a place as they had earlier thought. Although migrant-receiving countries also gave many positive impressions to ex-immigrants, due to space constraints I focused on the social forces that led ex-immigrants to gradually become ambivalent and ultimately abandon immigration, since that was at the focus of this study. Many interviewees often seemed relieved to honestly express why they changed their mind about immigrating, especially as some noted that they were uncomfortable expressing such views while in migrant-receiving societies. They also sometimes expressed how they were reluctant to express such views to most people in China whom they felt could not understand or relate to their experiences abroad.

Social Factors Constituting Ex-Immigrant Subjectivity

Disappointment with the Migrant-Destination Society

Aspiring Chinese immigrants were disappointed that their migrant-host society was not how they had envisioned it to be based on what they had learned from books, movies, news, television, and friends’ stories. Most of what ex-immigrants knew about countries outside of China came from their geography and history classes, and from prominent current events that teachers in China thought warranted discussion, such as the 1999 US bombing of the PRC embassy in Belgrade. Generally, they learned mostly about the negative aspects of foreign societies from the PRC government-controlled news, for example gun violence, racism, and widespread drug addiction. Their most important source of information about foreign societies was popular culture, especially the limited number of television and commercial films the government censorship system approved of and would permit to enter the country. However, their parents often conveyed to them the idea that “developed countries” were richer and offered a better education than that available in China.

Yet many prospective immigrants found that little of the information they had received about their host society was relevant in preparing them for their eventual disappointment. Notably, due to the positively selective visa policies of most migrant-receiving governments, many ex-immigrants grew up in large and developed cities. They first settled in less urbanized communities of their host society. They were therefore disappointed by how inadequate and under-developed the transportation infrastructures were relative to their city of origin. Many discovered they needed a car or had to take the buses that ran infrequently or did not arrive on time. Feng, an engineer, described how inconvenient life was for him in both Norway and the United States without a car: “I needed to spend a half hour in a bus just to go to the supermarket and get food to eat, and then I could only carry home so much on one trip.” Ex-immigrants like Feng also complained about being unable to find affordable Chinese food that they liked, even in nearby countries like Korea. Those who lived in more urbanized places, like Wei, a legal assistant, were nevertheless shocked by the poor level of infrastructure:

New York City was much dirtier than I expected. The apartments were very aged. The road, the bridge, the electricity grid. They even have those wooden electricity poles for the power lines! Trains did not run according to schedule. It was very dangerous in the subway system. People could just push you onto the tracks. Bathrooms were filthy, with big mice running all over the place. All types of homeless people. I witnessed a robbery and a street fight a couple of times.

However, despite Wei’s initial shock about these conditions, he then explained that he gradually adjusted to the socio-economic reality that the particular neighborhood in Flushing where his parents could afford to rent would not have “new and fancy facilities and people who were much better behaved than in China.”

Ex-immigrants were also shocked by the general inefficiency of their host societies. Participants frequently complained about the length of time it took to obtain a debit card, visit a doctor at a hospital, or deliver a package. Lei recounted how she had a toothache when she was in Britain and could not sleep. She made an appointment at a public hospital because it was free for students. Yet she had to wait for a month before she could register. She learned that she would not be able to see the dentist for one to three months. She therefore made an appointment at a private hospital, paying two or three times more than she would pay in China. Lei was surprised by this because she could typically see a doctor on the same day back home for a fraction of the cost. She also found the process of clarifying the costly medical bills exhausting: she constantly had to call the insurance company, and no one ever picked up.

Some ex-immigrants described how they found some of the native-born in the migrant-receiving society as “selfish”, “obsessed with freedom,” and lacking in “self-discipline” and “morality”. They were surprised to receive this impression because of a much more prevalent widespread belief in China that people in many migrant-receiving societies were of “high quality” (e.g. meaning well-mannered and better behaved) compared to those in China. Kino, a journalist, described how she found Americans “spiritually vulnerable”. When asked to elaborate on what she meant by this, she said:

I think some people are screaming for things that are not a big deal. When I was doing my masters degree, I had a close friendship with this American girl. But every time we were getting ready for our exams, or we had to do a core project, she would go nuts, saying I have a heavy headache, and I have to take some pills. But I think people are making themselves more vulnerable to turn on to drugs to find a release.

Kino realized she had taken for granted the fact that drugs were not such a pervasive problem in China after observing how extensive the abuse of drugs was in the United States.

Even if Chinese ex-immigrants adapted to such disappointments, what they found most intolerable over time was how “boring”, “quiet”, "monotonous”, and “slow” their host society was compared to China, which they described as far more “innovative”, “dynamic”, and filled with people “eager to achieve something.” When I asked them for examples of what they meant, they said they found fewer stores open for shorter hours, fewer choices in entertainment, and only activities they did not enjoy, like hiking, skiing, sporting events, watching movies, and the pub. Li, a trader and ex-immigrant of Australia, noted how:

Here [in China] I can have freedom to live a life here and have many choices. In Sydney, it is quite a simple, day-by-day life, like the retired life. That kind of life for me is too simple, and every day is the same. Meanwhile, China keeps changing, every day is different.

Fen, a trader, seemed to echo this perspective after I asked her what she thought of the lifestyle of Germans. She bluntly proclaimed,

BORING! You know at the weekend in China, so many people are outside, but in Germany the stores close early and some are not even open on Sunday. In China we can go shopping, then eating, and then singing, but in Germany all I can do is ride a bicycle, read a book, or take a walk in the forest.

Since Fen came from a city where shops stayed open quite late, she was disappointed to find that businesses in Germany did not operate such long hours and were closed one day each week. Neither Li nor Fen found the tranquil activities she mentioned as enjoyable or stimulating as the continuous urban activities they could enjoy in China’s large, bustling (热闹/rènào) cities. Although many found their education and work challenging and engaging, ex-immigrants found life far less convenient (方便/ fāngbiàn) and dull abroad than in China. Such boredom also seemed exacerbated by the frustration they experienced communicating with non-Mandarin speakers.

Language Barriers

Despite the tremendous amount of energy, money, and time ex-immigrants needed to invest in learning the local language and passing a language exam in order to acquire a visa, after arriving in their host society many still had trouble understanding the local vernacular. An education consultant, Jing, found it difficult after arriving in Alabama to understand the local accent. Their English sounded completely different from what she had learned from television and school:

I kept thinking my English was so bad. I didn’t understand at all whatever they were talking about. I had to spend a whole extra year to master learning their English, but I was really struggling. Almost like I don’t want to talk to anyone during the first year because I don’t know what they are saying to me.

Understanding little of what most people around Jing were talking about would further contribute to her boredom since she could not follow people’s conversations. She found that trying to listen carefully and understand what was being said exhausting. She would often tune out and just find herself lost in her own thoughts. Only after an extra year of English study did she gradually begin to understand Southern American English.

Even if ex-immigrants understood nearly all of what they heard, they often had trouble quickly comprehending and responding to their holistic meaning, jokes, and the plays-on-words that they would often hear in more casual conversations outside the workplace. Bo, a former photojournalist immigrant in Canada, spoke of how:

It’s just hard for me to understand what they were talking about, right? When I was helping edit a magazine, I checked the grammar of what they printed in the sample issue. I saw there’s a word called Movember. I was going to take it to the chief newspaper editor, thinking it is an error, but then he explained that it was referring to November. Because they have this activity where people kept growing their moustaches in November to raise awareness of cancer or something. You might think that sort of thing is rare, but I observed it happening a lot for me.

This made it difficult for Bo to share the Canadians’ cultural meanings and to edit their work appropriately.

The language barrier was especially daunting for those in professions which require much cultural knowledge. Mei, an advertiser and ex-immigrant of the United States, recognized that her difficulty in understanding the language puts immigrants in the marketing profession at an enormous disadvantage compared to the native-born:

English is our second language. Even if your language is very good, they know more about the cultural background of the language. A professor wants someone to answer a question. Although we (foreigners) may figure out the answer to the question after thinking for a while, we cannot respond as fast as natives because we still need to translate the language before we can answer. We cannot succeed in competing with them.

Silvia said this led her to anticipate that she would also be disadvantaged in getting a promotion in the workplace if she decided to immigrate.

Many noted they had no trouble communicating with native speakers on a one-on-one basis or in professional settings. However, they had a much harder time communicating even with the same colleagues around the water cooler or in more informal after-work settings in large groups. Tim described how this made it difficult to foster a shared perception, thereby reducing his sense of cultural belonging: “It is difficult to fully integrate into the culture. It is no problem to communicate with colleagues in English, but if you want to talk and laugh, you can’t do it.” Similarly, Li, a social worker who had tried immigrating to the US, noted how, “If three local people are together and they talk about their local things, it is hard for me to understand. Their use of language made me feel like I was not welcome.” Although the native-born may not have intended to be unwelcoming, ex-immigrants perceived the natives’ more colloquial use of language during after-work hours and cultural settings—when ex-immigrants admitted to being the most bored—as culturally alienating.

Cultural Alienation, Loneliness, and Homesickness

Many ex-immigrants’ boredom with the local people’s lifestyle and hobbies and the language barriers both contributed to their cultural alienation, loneliness, and/or homesickness, particularly during Western holidays and Chinese New Year. Exchange programs for students, au pairs, and work-and-travel cultural visitors often strived to reduce these sentiments and promote acculturation and adaptation by providing accommodation with a local host “pseudo family” [Selling Reference Selling1931] in the form of a host family or a college dormitory hall community. Yet ex-immigrants faced difficulties communicating deeply with locals due to a lack of shared cultural backgrounds even if they lived in such a pseudo family and had to regularly interact with the native-born since there were few Chinese people in their community. A counselor, Zixin, described how he initially wanted to “immerse myself into the local culture” of Grand Rapids, Michigan as a psychology student there. But over time, he confessed:

I realized it’s really hard! Maybe for Americans going to a new place in another country, city only takes a few months to learn about the local scene and make a Chinese friend, but for Chinese people it will take three or four times longer to get to know an American friend […] I think having a host family helped, but it also made me realize how difficult it is to really be a part of American society […] If you were not born in that culture, you cannot understand what’s even funny. You need to wait for an explanation […] It’s just that strange feeling you have when you are in a community but don’t feel like you are a part of it […] it affirmed my decision to return to China.

Hence, the cultural opportunity to live with a host family and the process of acculturation paradoxically accentuated Zixin’s desire to return rather than remain because of the way he became disappointed at the limits of how culturally connected he was to his host family.

Many ex-immigrants described a sense of alienation even in culturally similar societies such as Singapore. Shu, a 25-year-old computer programmer, spoke of how she did not communicate much with local Singaporeans because she felt she had a different cultural background from the local people. “They don’t want to talk about the same topics. It is not a problem of the language itself,” she clarified. Others like Jianyu, a software developer who immigrated to Canada while he was still in primary school, felt that he did not share interests with the native-born he had to work with, and felt that social norms constrained him from speaking his mind in big North American cities:

I don’t like football or sports, but I feel that in the US when you meet people around the water cooler you need to know about football to talk to people. I also am not interested in their American politics, all their political dramas! My co-workers in America want to talk about it and I really don’t care. And when I speak, many people just disagree with me. I did not feel free there to speak my mind as in China. Here I can criticize gay marriage as freely as I want. I can criticize America. In Canada I can’t criticize feminism. But I can criticize feminism here. I feel I can express my thoughts more here. It’s ironic, but I feel we have more free speech here in China.

Jianyu began to feel uncomfortable expressing his opinion over time and described feeling more comfortable doing so in China. This extended to the lack of cultural affinity some ex-immigrants felt toward the popular activities of the native-born. Yao, an engineer who gave up immigrating to Norway, described how, “It’s hard to get into the local people’s social activities. They like to go to the pub very much. I wouldn’t say I like it; it is very noisy. I don’t like the entertainment. They don’t have entertainment in Norway—besides the pub.” Due to a lack of interest in spending his leisure time like the native-born, Yao like many ex-immigrants never formed strong friendships with locals.

A lack of interest in locals’ conversation often resulted from a lack of understanding about the local sense of humor. Similarly, Sun, a financier who gave up immigrating to Spain explained that when his colleague at a dinner party would tell “a connotative joke, you understand everything literally, but you don’t understand why everyone is laughing […] how lonely and horrible.” A few ex-immigrants described how they would worry about being perceived as awkward or dumb in such situations if they asked the native-born to explain their implicit understanding of something. They therefore did not ask them, and the native-born rarely proffered an explanation of what was funny. Ex-immigrants would often describe how they would have to invest a lot more time to befriend a local person, unless that person was the rare type who earnestly wanted to befriend a foreigner and was comfortable spending time with and relating to someone with a different cultural background. When I asked why Lin, an ex-immigrant accountant from Poland, did not make more efforts to interact with locals, she recollected, “I feel like it’s troublesome for them”. Therefore, she would avoid befriending locals even though she wanted to get to know them better. Over time, she began to feel that even approaching a native-born was an imposition.

When ex-immigrants tried to connect with others, they felt their efforts were in vain. Lei, an ex-immigrant to Canada, described how:

There was a time when I liked to make sandwiches. A Black girl who lived next door to me rejected my invitation to come and have sandwiches with me three times in a row, and she said to me: I think we’re just friends. So you start to walk alone, but you fill up your schedule with activities because you know that once you have nothing to do, this feeling of loneliness will overcome you. After you get used to it, you will gradually discover the feeling of watching the world from the sidelines, which will give you a good illusion that you can live by yourself. This illusion terrifies me.

Many admitted to thinking that this sense of isolation was a normal part of immigrating due to their perception of their host society as more “individualistic” than China. For many, everyone appeared to be much more on their own in their host society than in China. Although Chinese ex-immigrants recalled how many native-born would jokingly comment on how they were too hard-working and needed to have more fun, many ex-immigrants explained that they threw themselves into their work as an escape from feelings of cultural alienation. For this reason, many ex-immigrants eventually ended up spending time with their co-ethnics where this was possible, even though several felt this was out of necessity and for mutual benefit rather than genuine friendship.

Eventually, ex-immigrants concluded that striving to become more “cool” or likeable necessitated becoming like someone they were not, provoking their desire to return. The photojournalist Bo spoke of how he would ask himself in the mirror:

Should I change myself, whiten myself to be more like the local people, or maybe I should not, because this may lead to an identity crisis? Why should I do this? Why should I give up all my unique cultural background? If you want to immerse in the local people, you have to do that. For example, they play baseball; they watch baseball. Do I really want to talk about this? I would have to learn how to play, but that takes time […] Even if you adjust yourself, that does not mean everybody will accept you. You’re just an immigrant, and everyone knows you are just an immigrant.

Bo and other recent immigrants viewed adapting to life in another culture as not only a process of addition but also of subtracting from their cultural perspective. This necessitated sacrificing an integral part of their identity. Eventually, many ex-immigrants realized that those who were comfortable around the native-born had a much stronger aspiration and will to immigrate. Still, many did not really desire to become part of a different culture that was not their own. As a 26-year-old teacher, Xi, reflected on her time studying and working in the United States:

After six years, I have come to understand that integrating into American society is not an objective state that can be judged by “understanding 95% of late-night talk shows”, but a psychological state. And I haven’t reached it yet. The more critical problem is that I don’t want to reach it. I don’t want to get involved.

As Xi elaborated, she would much rather check her WeChat for news about China that interested her than learn about the news from a US source. The ex-immigrants of color, however, who successfully acculturate eventually realized that racial-ethnic discrimination constituted another formidable barrier to their being recognized and accepted by the native-born as members of society.

Racial-Ethnic Discrimination

Although ex-immigrant interviewees expressed having a vague awareness of racial-ethnic discrimination, most only became more sensitive to it after they had overcome the previously mentioned challenges of adapting to society. Ting, a human rights lawyer, described how a high-school trip to Britain enchanted her. At an early age, she became an avid reader of Jane Austen novels and a viewer of the BBC, even believing British people to be more elegant and bettered-mannered than Chinese people. She spent more than five years studying and working in France and another year in Britain. But the more time she spent in both countries, the more she realized Europeans did not respect her. Even in the cosmopolitan city of Paris, she repeatedly encountered anti-Chinese verbal attacks. Ting stressed that she did not decide to return to China right after a single experience but only after multiple such experiences. To her surprise, she paradoxically confronted more racial-ethnic discrimination the more fluent and conversant she became in the English and French cultures and languages. Chaoxiang echoed Ting’s experience, noting that the first time he heard someone shout “Ching Chong” to him in Australia, it did not bother him at all—he was just perplexed. But after he learned what it meant and heard it several more times, it started to bother him. Hearing “Ching Chong” was also a common experience of other Chinese ex-immigrants in public spaces of many Western countries. Others did not report being robbed to the police due to concerns about racial discrimination. Over time, many even became more suspicious of strangers who walked close behind them in public places where they might be attacked.

Compared to those ex-immigrants who came to their migrant-receiving society as adults, ex-immigrants who grew up in their host society seemed to have developed a stronger form of racial consciousness due to their experiences of racial discrimination. Jianyu realized that other schoolchildren were not willing to become his friends around the age of nine: “All the people that were willing to become my friends were Chinese, Korean, and Russian immigrants.” He acknowledged that only a couple of children were overtly racist in making remarks to him like, “You fucking immigrant, go back to your country!” Rather than becoming angry, Jianyu described how he tried to be “objective” and rationalize why he confronted such hatred. He learned that many native-born feared the numbers of Chinese people moving to Vancouver: their investment in real estate was causing housing prices to rise and the locals could no longer afford to rent a place. He reasoned that such racial-ethnic attacks were just the local people’s irrational way of expressing their frustration about this phenomenon. However, as he repressed his anger about it, he discovered “I became even more nationalistic, more self-aware of my Chinese identity. As China developed more of its own search engines and websites, I could learn more about China and see that it was better” than either Canada or the US, both societies into which his parents had earlier expected he would immigrate. This provided Jianyu with information about China with which he identified more in cultural terms, and he began to view it as superior to Western societies. He eventually decided to return to China as he identified more with being Chinese than being Canadian or American.

Other ex-immigrants perceived racial-ethnic discrimination as undermining their inherent worth, so they came to cynically perceive it as “a means to an end” due to the lack of a reciprocally affective relationship with the migrant-host society. I met Cui outside Beijing’s US Embassy in March 2015 while I was carrying out a survey of denied non-immigrant visa applicants. He burst out laughing when I approached him, soliciting an interview from him in Mandarin. He responded with the strong drawl evocative of a native-born American from the South, “What the fuck are you talking about? Visa interview? I just surrendered my green card man!” When I asked him why he did so, he responded: “I don’t want to have to keep paying taxes when most of my businesses are in China. I think obtaining a 10-year tourist visa makes more sense, and I want to get one before Trump becomes president and takes it away. That motherfucker is crazy.” Cui elaborated on how he understood Trump’s political rise as symbolic of what really disturbed him about US society:

The racism. I lived in Nashville, Tennessee, so I experienced the worst of it. They treat me like shit over there until I come into a store and spend over a thousand dollars. The country is full of all these stupid white men that vote for Trump and they treat you like crap. Which is stupid because I am more whitewashed than you are. I am a DJ here and own clubs where I fuck lots of White girls, most of them dancers!

From Cui’s perspective, being required to pay tax on his business revenues while not being offered any of the respect he felt he deserved meant that he would much prefer to remain a national of China, a country where he could enjoy more of his income, have more fun, and bolster his racial and masculine ego through the seduction of white women. Indeed, how racial discrimination undermined ex-immigrants in such an intersectional way also touches on the parallel challenges ex-immigrants faced in navigating a different system of gender norms in their host society.

Navigating Unfamiliar Gender Norms as a Source of Disenchantment

When I asked many ex-immigrants what might have led them to immigrate rather than return to China, the modal response was if they had found their “significant other” in the host society. Dating native-born members of the opposite sex seemed more challenging for the men I interviewed than the women. Most Chinese ex-immigrant men I surveyed were more reluctant than women to discuss their direct experiences dating and interacting with the opposite sex. Typically, they would explain why they had not found a partner through observations or their beliefs rather than their own experiences. Jianyu related that, after giving up on immigrating into Canada, he encountered the same problems in the United States:

I was a programmer, so dating was hard. In the US, most Asian American women only date white guys. Just go to any restaurant in Seattle. All the Asian women in the restaurant are with white guys. All the Asian guys are single. Here [in China] at least I can get dates. In Seattle, every Asian guy is either an electrical engineer working for Boeing or a software developer working for Microsoft or Amazon. It is more homogeneous […] If I stay in the US, I will probably be single forever.

This feeling of being physically undesirable made life in the United States unattractive for Jianyu—even if he could earn a far higher income as a computer scientist in North America than he could back in China. Whenever I probed further for details of specific dating experiences he and other Asian men had had, they would often not mention any at all. Instead, they alluded to cultural prejudices such as that Asian women prefer White men to Asian men because the US colonized Asia, or that Americans and other Westerners see China as a threat, with Asian men demonized and depicted as creeps or losers, and Asian women being sexualized.

Those male ex-immigrants I interviewed who did succeed in finding a native-born partner in the United States often decided to break up with them due to fear that their parents might disapprove of them as a spouse. Peng, who dated a White American girlfriend for a long time, recalled how, in the United States, he was worried that his parents would not be able to accept her culturally. “I had a good relationship with my ex-girlfriend. We just could not stay together because my Chinese parents would not accept a wife from a foreign culture. I had to listen to what mom and dad said.” Many other male ex-immigrants would often note that their cross-cultural relationships enriched their time abroad, but they viewed them neither as having marriage potential nor as avenues for immigration. Regardless of their age or education level, more than half of the several Chinese ex-immigrant men who immigrated with their Chinese partners or wives later separated or divorced them and returned to China. In contrast, their ex-partners (who several obliquely suggested had left them for another man) remained in the United States. Geneticist Huizhong explained how he and many other Chinese men were much more attracted to the growing opportunities that China’s dynamic economy offered them than women were. Their wives were more risk-averse and preferred more “stable” places, which relative to China they understood the migrant-host society to be.

Young ex-immigrant women often said they returned to China because they faced pressure from their parents to marry before they were 28. Based on both personal experience and “sad stories,” Ruan discovered that men in the United States were not dating to find a marriage partner as much as they were in China: “You definitely will have to have sex with your boyfriend. In the US, finding the right person is not so easy.” After a while, she reasoned that it might be easier to find a more suitable partner back in China. Similarly, Nuo, a 26-year-old engineer, told me, “I thought if I can’t find someone in the US, then I probably could find someone in China. So that is one reason I came back.” Her parents, frequently asking her about when she was going to marry, eventually persuaded her that she would have an easier time finding a partner in China. But she became very emotional in our interview, explaining that after having been in China for around a year she had still not found “Mr. Right.” She seemed anxious and insecure about being single. She stated that returning to China had brought her comfort in that, at least there, her parents could help her find a marriage partner.

Several ex-immigrant women and gay men described how they feared giving up their independence by immigrating through marriage, even after several men proposed to them and offered a clear pathway to citizenship. Fen, a 29-year old interior designer, described how she dated a US citizen while she was working as an engineer in San Francisco. At one point, he asked her if she wanted to simply marry him and thereby eliminate her constantly mentioned stress of applying for student visas at community colleges while working until she could win the H1-B lottery. But she chose not to do so:

Getting a green card did not seem a good enough reason to marry someone and somehow wrong. I did not think either of us wanted to marry, even though we were romantically involved. I ended up giving up and coming back here [to China], so we split up.

Similarly, despite Zhan’s happy relationship with her boyfriend in Switzerland, she eventually decided to return to China due to the lack of economic opportunities there. As she reasoned:

I don’t want to be a housewife. If I stayed, I don’t speak the local language. The best thing I can get is like a tourist guide or a housewife or, you know, earn shitty money.

Zhan’s comments point to how even those who manage to establish a satisfying, stable, and equitable relationship are not willing to continue to immigrate if the immigrant-host society presents too many obstacles for them in terms of their career development.

Limited Opportunities for Socio-Economic and Career Mobility Relative to China

Racial discrimination, language barriers, and cultural alienation contributed to the difficulties ex-immigrants experienced in obtaining vertical socio-economic and career mobility. One male ex-immigrant, Yu, who worked for 7 years in Canada as an engineer, reflected on how:

When faced with a job, your output value is higher than your colleagues, and you have also worked hard to socialize to integrate, but the upper management will still put other people before you for “racial” reasons. Some people can be promoted after working for a year, and some people can be promoted after working for ten years.

This was not unique to Western countries. Another ex-immigrant of Japan, Hu, explained that Japanese managers would always treat their Chinese employees as “little brothers.” Eventually, even if they sometimes noted that there was less pressure and a slower pace of work than in China, most of the ex-immigrants became frustrated with the barriers to upward mobility the longer they worked, especially if they were ambitious. The geneticist Huizhong came to the US in the 1980s to obtain a Ph.D. He then worked hard with the dream of earning a Nobel Prize. Huizhong said he found it difficult to accomplish anything given how developed and established most industries were in the US. In contrast, his industry was booming when he returned to China in 1997. This attracted him back, even if it required him to live far away from his wife and children who remained in the US.

Others who returned in more recent decades also spoke of how they preferred to pursue higher-risk and higher-return ventures and self-employed careers that were increasing in China even if they had a stable job in their host society. The latter most viewed as limiting in terms of upward socioeconomic mobility or not aligned with their career goals. Ai, a businessman and ex-immigrant of New Zealand, noted:

Although Asian people work especially hard, they usually don’t get very good jobs. I was a sales assistant in New Zealand. I mean, it’s not bad. It makes money. But in China, I make more money by running my business without working every day. Working in New Zealand, you work today, you make some money; you don’t work tomorrow, you don’t make money. I think having your own business in New Zealand as a foreigner is very difficult, especially since I can’t invest that much.

Ai, like many entrepreneurs, saw far more opportunity in China to run his own business than he could have in New Zealand, since he found it far easier to attract investors than abroad.

Ex-immigrants stated that they felt they had more “freedom” in China than they did abroad due to a relatively greater range of career opportunities in China. Fen explained how in Germany:

I face the ceiling, so I cannot get the higher promotion. In China, it is different because here I have freedom: If I remained in Germany I would work in a low-level occupation like a waitress or a secretary in a small company or just be an employee at a Chinese business. But, in China, I can find a good job, like in the export-import business. To stay in Germany would be a waste of my life.

For her and many other ex-immigrants, “freedom” did not mean civil liberties and political rights as it does for many Westerners. Instead, it meant not having to face the constraints of either socio-economic ceilings or the limited range of career options they confronted. Therefore, for Fen and other ex-immigrants, China was much freer than any liberal-democratic society, even if that derived more from economic freedom than from political freedom. This was true even for ex-immigrants in cultural industries that greatly valued political freedom, like the arts. Wu, a director and dancer of a cultural institute in Beijing who was an ex-immigrant in Germany, noted how he even had more opportunities to engage in new artistic activities in China than he did during his 11 years in Europe. But for many, freedom was also the ability to engage in a broader array of occupations, which was particularly the case for those in cultural industries. One expressed the opinion of many noting how if you wanted to be both an international student and work abroad, “you can only bite the bullet and learn computer science.” Or, in the words of another, “I can only do a technical job and give up my favorite investment/entrepreneurial projects/small businesses. For me, I feel that life is less fun. I didn’t want to limit my youth to this one position, so I chose to go back.” Returning to China therefore expanded the career possibilities of many ex-immigrants.

Wei, who cared deeply about social justice, helped his immigrant mother campaign for Hillary Clinton in her race to become governor of New York. He was brought to tears when Obama won the presidential election. He once aspired to become a political leader in the United States. Yet he began to become disenchanted with the idea of immigrating to New York City while completing his J.D. in immigration law. Although he had completed two additional bachelor’s degrees (a double major in US History and American Political Science on top of his bachelor degree in English from China), other law students of color told him that he was not qualified to speak about racial issues as a Chinese immigrant.

They would tell me you are even more economically well-off and privileged than whites. They would talk about economic differences between Indian and Chinese immigrants. They would say your country grows fast. Once you get a US education you can go back, whereas Indians will not go back. Even though I was very committed to American society and social justice, I feel like I was marginalized there.

Despite his best efforts to contribute to US society through progressive politics, Wei did not feel an adequate sense of belonging and inclusion as an immigrant, even within progressive political movements. That reduced his sense of belonging even among those segments of US society he genuinely aspired to belong.

But Wei confronted an even more visible ceiling when he moved with his two-year old daughter and wife to Arizona so she could get a Ph.D in Accounting and he could obtain a Ph.D. in Sociology.

In New York City, people would treat you politely and quietly even though in their eyes you are a perpetual foreigner. But in Arizona, they are more straightforward. They don’t care how long you have been in the US, how much you know about the US, or whether you are better educated than many people in Arizona. They see you like an invader.