Introduction

State responses to repatriation of Islamic State (ISIS) foreign fighters and their children detained across Syria and Iraq are highly diverse.Footnote 1 The repatriation policies implemented between 2018 and 2020 range from denying repatriation of nationals and revocation of citizenship to repatriation and subsequent gender-responsive rehabilitation programmes.Footnote 2 Overall, states of the Global North seem reluctant to repatriate whereas Central Asian countries are taking a more proactive approach.Footnote 3 Yet, beyond this observation it remains unclear how and why states behave differently in terms of their approaches to repatriation of ISIS-affiliates. This article thus seeks to explain why state repatriation policies differ despite the common security and human rights dilemma faced by all states.

Repatriation of the twelve thousand foreign ISIS-associated women and children from the Syrian camps ran by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) is the only comprehensive long-term solution. This is not only advocated for by the AANES but by experts from across the globe, including security experts,Footnote 4 the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF),Footnote 5 the Red Cross,Footnote 6 and even victims of the 2016 ISIS Brussels attack.Footnote 7 The food and health situation in the camps is dire and the detained are held without charges increasing the risk of (re-)radicalisation.Footnote 8 This prolonged Guantánamo-like detention is a security risk as previous experiences show that unlawful detention can contribute to the development of ISIS, such as the Camp Bucca in Iraq.Footnote 9 Moreover, the current regional and global developments, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the Turkish offences on northern Syria further increase the need of finding a timely solution to avoid increasing harm.Footnote 10

This article investigates state repatriation policies of foreign fighters across 69 countries.Footnote 11 The policies are categorised ranging from unconditional repatriation to denying repatriation. To explain the variation of state responses a mixed-method approach is employed. First, an explorative statistical analysis is performed drawing on conventional International Relations (IR) propositions.Footnote 12 The results of the analysis are inconclusive and find no compelling explanation. Thus, second, a narrative analysis informed by an intersectional gender perspective is employed to help explain variance that the statistical analysis cannot. The narrative analysis explores state policies and their social constructions of the security threat of foreign fighters in policy documents and the media. The intersectional gender perspective is crucial to examine how intersecting markers of identity, including gender, racial, religious, or classist dynamics are instrumentalised to frame foreign fighters as, for example, threatening. My analysis builds upon feminist security studies that highlight the gendered and racialised constructions of threat.Footnote 13 This method enriches IR theorising by applying narrative analysis developed by critical and feminist security studies scholars in the context of foreign fighter repatriation. My narrative analysis reveals that gendered and racialised ‘threat narratives’ of foreign fighters are constructed by states to support and promote various repatriation policies, hence explaining the variation of state responses. These narratives, which, for example, victimise female ISIS members have far-reaching implications pertaining to access to rehabilitation and citizenship withdrawal. The article makes a distinct contribution to the field of feminist security studies as it not only employs a gendered, intersectionality-informed narrative analysis of foreign fighters’ repatriation but also demonstrates how such narrative analysis is essential to explain state behaviour in the context of an ongoing, unresolved crisis.

Categorisation of state repatriation policies

To explore states’ responses to repatriation of foreign fighters and explain why there is such wide variation among them, I analyse the policies of 69 countries between January 2018 and December 2020 (overview in Appendix 1, Table A1). A country is included in the dataset when citizens are currently or have been in the past detained in camps or prisons in Syria or Iraq.Footnote 14 The data is gathered with open-source material, predominantly policy documents, news articles, academic articles and research reports. From the 69 countries almost half (33 countries) repatriated citizens from Syria or Iraq, though most of them only in piecemeal operations and not as a comprehensive policy.

The repatriation policies of the countries are grouped into four different categories: Unconditional Repatriation, Conditional Repatriation, Allow Return, and Deny Repatriation (overview in Appendix 1, Figure A1). Of the 69 countries, seven were grouped into the category Unconditional Repatriation, which implies that the countries agreed to repatriate all its citizens or have already done so, such as Kazakhstan. Countries in this category also allow their citizens to return on their own. Twenty-six countries were grouped into Conditional Repatriation, which refers to countries that have occasionally repatriated but do not aim to repatriate all their citizens. Crucially, most of the countries in this category have repatriated women and children but not men (70 per cent of countries repatriated only women and children and 50 per cent minors only). Conditional Repatriation countries also allow citizens to return on their own. Sweden is one example of a Conditional Repatriation country because it repatriated a few citizens – the majority were children – but does not aim to repatriate unconditionally.Footnote 15 The third category is Allowed Return with 28 countries. This category includes countries that did not actively repatriate any citizen but allows them to return on their own. One example is Serbia since the Serbian government, unlike its Balkan neighbours, has allowed citizens to return but has not taken any active steps to repatriate its citizens nor addressed the issue of repatriation publicly.Footnote 16 The fourth category, Deny Repatriation, consists of eight countries and refers to countries that actively prevent citizens from re-entering.Footnote 17 This may take the form of stripping citizenship or legally banning citizens from re-entering the country, such as Denmark.Footnote 18

It is important to point out that these categories should be understood as dynamic and changing and more viewed on a continuum ranging from unconditional repatriation to denying repatriation. This is because the topic is current and ongoing developments, such as geopolitical events in the region and locally within the camps and prisons continue to influence the states’ repatriation policies. Moreover, some countries refrain from making their repatriation policy publicly available and others change theirs unannounced, making it challenging to assess the situation.Footnote 19 Another limitation is that because the countries were grouped according to the publicly available information there is a chance that for instance, a country claimed to have repatriated its citizens but there are still some remaining in the Iraqi justice system or hidden in the camps. However, the categories should not be understood as implying, for example, that every single citizen has been repatriated but rather as describing a countries general repatriation policy and political willingness. The presented data and subsequent analysis should be regarded as a first attempt at explaining the variety in states’ repatriation policies.

Explaining variation in repatriation policies: Conventional approach

To assess the factors behind the state adoption of widely varying policies, conventional IR propositions are operationalised as variables in an explorative statistical model. This is done because IR explanations have typically explained state behaviour including the international diffusion of state policies.Footnote 20 Thus, in an attempt to analyse repatriation policies cross-nationally, IR explanations could be pertinent.Footnote 21 These explanations can be operationalised through the study of the presence or extent of a range of domestic and international conditions and factors, such as form of government, conflict, or international cooperation.Footnote 22 As yet, no IR scholarship has explored or tested the various IR explanations for foreign fighter repatriation.

An explanation that has traditionally been used in the field of IR to understand various phenomena, including state compliance in international environmental agreements or economic well-being, is military spending.Footnote 23 Military spending is operationalised with the military spending (per GDP) variable from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute's database.Footnote 24 It is expected that countries focusing on militarism (high military spending) might want to ‘keep the terrorists out’ and refrain from repatriation because foreign fighters could pose a security risk.

Another alternative explanation in the context of foreign fighter repatriation might be international cooperation. This is because membership in international organisations has been used by IR scholars to understand state's behaviour in global challenges, including with regard to developmental assistance or the protection of the ozone layer.Footnote 25 International cooperation is operationalised by coding membership in the Global Coalition against Daesh.Footnote 26 The organisation was founded in 2014 to fight ISIS military, its economic infrastructure, and to support liberated areas. It is expected that member countries are more likely to repatriate their citizens as this would help to stabilise the region and to literally decrease the number of ISIS members.

IR explanations for state behaviour also focus on human rights, such as its relationship with sovereignty or conflict.Footnote 27 The repatriation of citizens is a human rights issue because, among many others, UN human rights experts claim that the ‘detention camps reach the threshold standard for torture, inhuman and degrading treatment under international law’.Footnote 28 Two variables from the Worldwide Governance Indicators provide the figures to assess the human rights records in a given country; namely the Rule of Law and Voice and Accountability variable.Footnote 29 These two variables provide an overview of the juridical system and the freedom of speech and media. Furthermore, two variables from the Human Freedom Index are analysed; the Identity and Relationship variable in order to assess rights around sexual orientation and gender identity, and the degree of Religious Freedom variable.Footnote 30 By analysing these four variables a range of human rights (and human rights violations) can be examined. It is argued that countries with a better human rights record are more likely to repatriate because they aim to evade that their citizens live in inhumane conditions.

Another alternative explanation for states' repatriation policies relates to concerns around national identity, which is ‘socially constructed through interaction with other actors’ and represents the state's self-understanding and interests.Footnote 31 This is proxied by the states’ independence year because newly independent states often have to find their identity and reputation in the international world order that can be influenced by, for example, foreign policy and internal politics, such as the choice to repatriate or not.Footnote 32 It is expected that younger states may still wish to influence their image positively through repatriation.

More recently, IR scholars also consider measures of gender equality to be a determining explanation for phenomena, such as states’ experience of terrorism.Footnote 33 Gender equality is operationalised by several variables from the Global Gender Equality ranking: Economic Participation and Opportunity, Political Empowerment, Educational Attainment, and Health and Survival.Footnote 34 Generally, states that institutionalise gender difference, meaning that women and men are fundamentally different from each other and that value traditional feminine stereotypes, such as vulnerability, have lower levels of gender equality.Footnote 35 It is argued that these countries are more likely to repatriate because viewing women as, for instance, vulnerable leads to the need for ‘protection’ and thus repatriation of women and children.

In IR scholarship the form of government is also thought to impact state behaviour, including, for example, in the context of durability of international military alliances.Footnote 36 The form of government is proxied by the Democracy Index.Footnote 37 It is expected that the more democratic a country is, the higher is the level of repatriation because democracies theoretically imply accountability, transparency, and public participation in politics.Footnote 38 Thus, in a functioning democracy the citizens are able to participate in political processes and can hold states accountable for, for instance, not adhering to international law and neglecting the duty of care for their citizens, which may foster governments to repatriate their citizens to avoid legal repercussions.

The salience of conflict and terrorism might also influence repatriation policies because it could lead to resources being focused on fostering peace or winning war instead of bringing ‘terrorists back’. This dynamic is operationalised by the Ongoing Domestic and International Conflict Domain from the Global Peace Index and the Global Terrorism Index.Footnote 39 It is argued that if a country has experienced conflict or terrorism in the past years it is less likely to repatriate. Crucially, the Global Terrorism Index only measures terrorism executed by non-state actors and not by the state itself. Yet, governments are often the ones perpetrating terror like tactics.Footnote 40 Therefore, state violence, such as arbitrary detention and kidnappings is proxied by the Political Terror Scale.Footnote 41 It is expected that states ranking high on the Political Terror Scale are less likely to repatriate citizens.

Analysis and results

To assess whether the IR explanations can explain states’ repatriation policies a dataset was created based on the variables operationalised with above-mentioned proxies. The dataset was examined and analysed in two steps: First, I ran a correlation analysis with all focal variables. Second, I ran a multiple linear regression with all focal variables as predictors and level of repatriation as the outcome variable.Footnote 42, Footnote 43 This was done to see if each of the predictor variables significantly predicts the level of repatriation while keeping all other factors that may affect level of repatriation constant.Footnote 44 All analyses were performed with and without controlling for country-level variables such as GDP per capita, Region, and Population Size. The results were unaffected by adding control variables, hence, the results are presented without control variables.

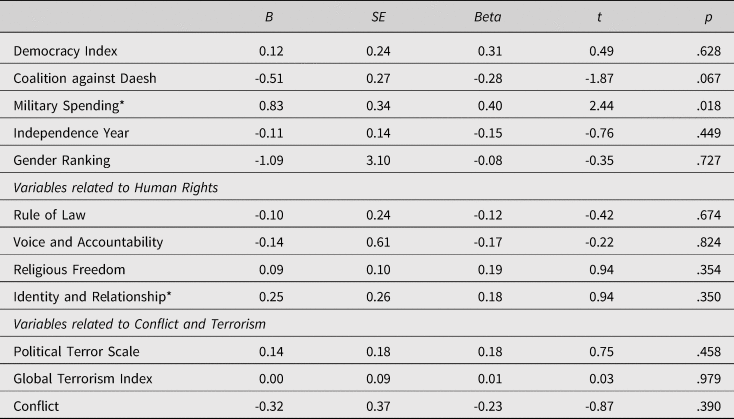

Results of the correlation analysis indicate that several of the predictor variables are intercorrelated, but that none were significantly correlated to repatriation policy (Appendix 2, Table A2). Results of the multiple linear regression with the identified key variables as predictors and level of repatriation as the outcome variable indicate that military spending is the only variable that has a statistically significant positive relationship with level of repatriation when controlling for all other factors (see Table 1). This indicates that countries with a higher military spending are less likely to repatriate their citizens fitting with the protectionist narrative that countries focusing on militarism might refrain from repatriation because foreign fighters could pose a security threat.Footnote 45

Table 1. Results of the multiple linear regression with repatriation policy as the outcome variable.

Note: N = 66.Footnote 46; R2 = .19; Adj. R2 = .01; ‘*’ after a variable indicates that the variable has been transformed through a log transformation. For the ‘Gender Ranking’ variable each subscale as well as the full Index of the Global Gender Equality ranking was tested and there was no difference in results. Thus, only the results with the full index are presented.

While IR propositions offer different explanations for why governments might choose to repatriate or not, statistical analysis of key variables shows none of them, except for military spending, have a significant relationship with the level of repatriation.Footnote 47 In addition to statistical analysis, taking a closer look at the individual categories reveals surprising patterns. For instance, although the variables measuring the human rights record do not have a significant relationship with the level of repatriation, the results reveal a counterintuitive picture. Countries that rank high on human rights, including Denmark and Australia, are not in the Unconditional Repatriation category but rather in the Deny Repatriation group. Moreover, countries that are not renowned for their human rights record, including Russia, have taken a proactive approach to repatriation. In particular, the Chechnyan leader Ramzan Kadyrov, infamous for his gross human rights violations, attempted to improve his record by repatriating children from the conflict zone.Footnote 48 This suggests that it is not the actual human rights record of a country (as indicated in the statistical analysis) that matters, but rather how repatriation is communicated with the intent of enhancing state reputation. Specifically, the repatriation of children – who are deemed most valuable and worthy of protection – might boost the international reputation of a country as repatriation signals that the country ‘values’ human rights. As such, the repatriation of children could be a strategic, calculated decision by political leaders and institutions to demonstrate a country's awareness, if not record, of human rights.

Another interesting finding is that countries in the Unconditional Repatriation category demonstrate certain commonalities pertaining to independence year, region, and religion. Five out of seven countries are younger states – they were founded after 1991 – and six out of seven countries are from two regions, namely from the Balkan and Central Asia. A possible explanation for these trends could be that younger countries, such as Kosovo and Uzbekistan still need to define their national identities and the repatriation provides them with a window of opportunities to project, build and confirm these. Moreover, given that six out of seven countries are from two regions, peer effects – a phenomena that countries within one region ‘learn’ from each otherFootnote 49 – might drive neighbouring countries to develop similar repatriation policies.Footnote 50 Additionally, six out of seven countries in the Unconditional Repatriation category are Muslim-majority states and five out of eight Deny Repatriation states are Christian-majority states. This might suggest that Muslim-majority states are more willing to repatriate whereas in Christian-majority states elements of Islamophobia might influence the repatriation policy.

The explorative statistical analysis that tested frequent propositions and explanations offered by IR shows they have limited utility in explaining why states choose to repatriate their ISIS-affiliated citizens or not. No strong pattern or common political, economic, or terrorism-related factor appears to explain the variation in policies. As a result, the question why some countries choose (not) to repatriate remains. This leads me to explore other possible explanations and relevant methodologies. Given the gendered and racialised nature of ‘terrorist’ framings, which I explore in the next section, I interrogate the policy narratives of states and employ an intersectional gender analysis to specifically examine the ‘threat narratives’ of foreign fighters. Such a nuanced, qualitative approach highlights significant and plausible explanations for the differing repatriation policies. Before moving to the narrative analysis of state repatriation policies, this next section explores feminist approaches to security studies, which promote the type of narrative analysis that I adopt in this study.

Feminist approaches to security studies

Feminist theorising has long demonstrated the importance of investigating intersecting gendered and racialised dynamics in international politics, because it can, for example affect the treatment of ‘terrorists’ by infantilising women or racialising ‘Muslim men’. Gargi Bhattacharyya has demonstrated this with her analysis of the ‘dangerous brown man’ in the War on Terror or, more recently, Caron Gentry has considered how gendered, racial, and sexualised assumptions frame ‘Western’ understandings of terrorist actors.Footnote 51 In terms of ISIS foreign fighters, these biases are illustrated when considering the dominant terminology. Throughout the academic literature,Footnote 52 UN reports and Resolution 2396,Footnote 53 policy documents,Footnote 54 and in the media,Footnote 55 the term foreign fighter refers to male foreign fighters – typically without acknowledging it. Female foreign fighters are referred to as ‘family’, conflating the categories ‘women and children’.Footnote 56 Assuming that women are family of the male foreign fighters carries wide-ranging implications. It alludes to the fact that men are the ‘actual terrorists’, whereas women are the benign family members who are just being carried along, influencing their culpability and equating the woman's mental competence with a child's.Footnote 57 This illustrates what Cynthia Enloe has been outlining for three decades, namely that women as a category seem to stay inextricably linked with children.Footnote 58 Although women have committed terrorist attacks across the globe, such as in Indonesia or the United States.Footnote 59 Indeed, most of the women who joined ISIS performed non-combat roles and most men fought. Nonetheless, scholars contend that female ISIS members should be referred to as foreign fighters because individuals who ‘join regular armies are classified as military personnel regardless of whether they perform combat duties’.Footnote 60 Besides, not categorising women as foreign fighters because they predominantly performed roles in logistics, propaganda, and childrearing underlines the gender-biased view that ‘supporting’ roles are not decisive for terrorist groups; although the longevity of organisations has always been connected to their female membership.Footnote 61

Underscoring the significance of intersectional gender analysis, gendered terrorist framings have implications for the way we treat foreign fighters in criminal law and prosecution, in prison terms, and with regard to the provision of social, psychological, health, and other services. For example, Jessica Davis stated that ‘the counter-terrorism response to women in the Islamic State has likely been influenced by the highly gendered language used by media when reporting on the subject.’Footnote 62 Moreover, Joanna Cook and Gina Vale argued that for female ISIS members the media portrayals have varied between ‘active security concern’ and duped ‘victim’.Footnote 63 Indeed, Harmonie Toros examined the narratives of women returnees in Morocco and Tunisia and found that in Morocco, where women were described as victims, rehabilitation dominated the narrative, whereas in Tunisia women were regarded as a threat, which led to a criminal justice response.Footnote 64 Crucially, the legal system is similarly biased as women who engaged in terrorism have a lower chance of getting arrested, convicted, and receive lesser sentences due to prevailing gender norms.Footnote 65

The bias for girls and women, in particular for mothers, is underlined when considering that they are often referred to as ‘jihadi brides’ in the public discourse,Footnote 66 portraying them with a lack of agency.Footnote 67 Yet, referring to women through their marital status – bride – is not just terminology used in tabloid media but in official government documents as well. The United States Department of Justice released a statement where a repatriated foreign fighter is described as ‘given a monthly stipend, a Chinese-made AK 47, and an ISIS bride’.Footnote 68 Moreover, Alice Martini studied media narratives of British ISIS women and argued that the usage of ‘bride’ is not only infantilising but also carries neo-orientalist tropes that homogenises women's experiences.Footnote 69 Carys Evans and Raquel da Silva found similar gendered, racialised, and Islamophobic narratives in the social media discourse around Shamima Begum, a British woman who joined ISIS as a minor.Footnote 70 Framing female ISIS members as brides is a narrative conveniently perceived by many as it aligns with the lack of political agency falsely assumed for women, specifically Muslim women in the Global North.Footnote 71 Overall, the gendered and neo-orientalist narratives are showcased by the widespread lack of understanding in the Global North of why women were attracted to ISIS, because by joining the women rejected ‘the security, stability and gender-based freedoms of their lives … [which is] deeply disturbing to established civilizational narratives of “West is best”.’Footnote 72

When researching the diffusion of states’ repatriation policies, it is also crucial to consider the gender power dynamics of the actor ‘implementing’ the repatriation policy, namely the state. Gender power relations describe the socially constructed hierarchical order of masculinities and femininities that structure the state and the international political arena in which terrorism and counterterrorism measures takes place.Footnote 73 Swati Parashar, J. Ann Tickner, and Jacqui True, for example, argue that the state ‘speaks a gendered language, behaves like a patriarch, and enables gendered politics’.Footnote 74 Thus, the masculine state may act like a male ‘protector' of its citizens.Footnote 75 This relationship becomes evident when considering counterterrorism and counter violent extremism policies where the state is regarded as a ‘bulwark’ against the threat.Footnote 76 Fighting ‘terrorists’ to protect citizens is, therefore, often viewed as legitimate, although a deeper analysis of how the racialised and gendered term of ‘terrorist’ comes into existence is lacking.Footnote 77 Hence, the masculine state upholds not only gendered, but also racialised and neo-orientalist structures that shape the policy narrative regarding the repatriation of foreign fighters. Feminist security studies argues for an intersectional gender perspective to adequately capture these power dynamics, and as such, the narrative analysis in the next section builds on this theorising.

‘Threat narratives’ of foreign fighters

To explain the variation in repatriation policies the national ‘threat narratives’ of foreign fighters are assessed with a narrative analysis informed by an intersectional gender perspective. The intersectional gender perspective is crucial to examine how intersecting markers of identity, including gender, racial, religious, or classist dynamics are instrumentalised to frame foreign fighters as, for example, threatening. The narrative analysis, which is now well established as a method, extends the traditional tools for policy analysis that typically explain policy diffusion through readily measurable indicators, such as governance arrangements, economic resources, or type of polity.Footnote 78 Based on the statistical analysis in the previous section, however, these factors do not appear to explain repatriation policy variation and therefore narrative analysis is used to develop an alternative explanation for the differences in repatriation policies.

Narrative analysis demonstrates the impact that key stories and ideas connected in a causal chain from politics and the media can have on the thoughts and behaviours of citizens in the context of, for example, policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemicFootnote 79 or in LGBTIQ+ activists’ use of personal stories to change discriminatory policies.Footnote 80 Interestingly, to be convincing policies do not necessarily have to rely only on facts.Footnote 81 Rather, to be persuasive policies need to be story-like and structured into a narrative ‘that includes setting the stage, establishing a plot, casting characters (heroes, victims, villains), and specify[ing] a moral’.Footnote 82

Feminist and critical security studies research shows the importance of narrative analysis in the context of, for example, surveillance, ‘counter-radicalisation’ strategies, or ‘violent women’.Footnote 83 My narrative analysis builds upon this tradition and focuses on states’ ‘threat narratives’ of foreign fighters that are employed to support and promote various repatriation policies. My analysis is informed by feminist security studies scholarship that highlights intersectionality, such as the gendered and racialised constructions of threat.Footnote 84 This method enriches IR theorising by applying narrative analysis developed by critical and feminist security studies scholars in the context of foreign fighter repatriation.

The ‘threat narratives’ are assessed through statements in policy documents and the media as well as their analysis in scholarship.Footnote 85 This includes different sources and media outlets depending on the respective country, such as Al Jazeera, The Guardian, Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), or Caravanserai.Footnote 86 Moreover, public announcements from politicians regarding repatriations, such as on presidents’ websites, or videos of the repatriation itself, which was predominantly the case in Central Asia, are also taken into consideration. Further, the analysis of repatriation policies in terrorism and security studies research is assessed.Footnote 87 The sources are examined in a three-step process. First, as repatriation policies were implemented from 2018 onwards, I created a database of all articles and publications from January 2018 until December 2020. Second, I selected a subset of articles and publications that described or analysed the detention or repatriation of foreign fighters. Third, to analyse these sources, I specifically asked the following question: How can attention to the narratives used to support and promote policies help to explain the differences in repatriation policies? Here I aimed to identify the stories around foreign fighters to analyse variations in the ‘threat narratives’ across states.

The repatriation narratives are investigated in two categories, namely Unconditional and Deny Repatriation states because the analysis could not be performed on all 69 states of the dataset. Moreover, researching these two categories demonstrates the sharp difference between the narratives of states who favour and deny repatriation because the two categories present both ends of the dynamic continuum. The middle of the continuum is neglected because it is difficult to assess the narratives of countries in the ‘middle’ as there is often no public discussion around foreign fighters. As such, choosing to investigate Unconditional and Deny repatriation states guarantees a narrative as well as shows the difference between the two ends of the continuum.

I argue that the gendered and racialised narratives of foreign fighters are crucial to explaining why some governments repatriate foreign fighters. Specifically, I argue, as illustrated in Figure 1, that countries that pursue Unconditional Repatriation portray foreign fighters as victims and in need of rehabilitation, whereas states that Deny Repatriation frame foreign fighters as racialised villains and threats to national security. The hero in this equation is the state – the masculinist protector of its citizens. Either as the patriarchal sovereign under whose protection the citizens are safe from the foreign fighters or as the institution facilitating rehabilitation to help foreign fighters, like prodigal sons and daughters, who took the wrong path.

Figure 1. Narrative of Foreign Fighters Repatriation Policy.

The ‘victim’ narrative

Among the seven countries in the Unconditional Repatriation category a common ‘Victim’ Narrative appears where the foreign fighters are presented as victims in need of rehabilitation. In Kazakhstan, Ruslan Seksenbayev, the Director of the Peaceful Sky non-governmental organisation that counters violent extremism, stated that Kazakh citizens in Syria were ‘enslaved’.Footnote 88 Similarly, then president Nursultan Nazarbayev referred to foreign fighters as innocent and argued that ‘they were taken to this crisis-ridden country under false pretences and held hostage there by terrorists from the international terrorist organisation called IS.’Footnote 89 Importantly, it can be assumed that the former president only refers to women and children because the intelligence chief further argued that women will be rehabilitated and men will be prosecuted.Footnote 90 This entirely shifts culpability away from the women and presents them as naive, non-threatening, and being tricked into going to Syria or Iraq. In contrast, the returning men were all charged upon arrival in Kazakhstan, which presents them as a threat.Footnote 91 This narrative is starkly reminiscent of Caron Gentry's and Laura Sjoberg's research who argue that women who are involved in terrorism are denied agency and political will.Footnote 92

The gendered narrative is further underlined by a seven-minute video released by the Kazakh government showcasing the repatriation of Kazakh citizens from Syria.Footnote 93 In the video, the male foreign fighters are brought into the open handcuffed and blindfolded whereas the women are shown holding their children with newly received toys. Moreover, all the Kazakh soldiers in the video are male, except for one soldier whose long, painted nails are supposed to suggest that she is a woman, and who is filmed changing the clothes of a baby.Footnote 94 This strongly underlines the gendered narrative not only of the threating male perpetrators and the women victims holding their children, but the soldiers are also portrayed as gender conforming. Interestingly, none of the countries in the Unconditional Repatriation group allow women to be in military combat roles, whereas in the Deny Repatriation group several countries do, such as Poland and Denmark.Footnote 95 This aligns with the stereotypes of presenting women in need of protection rather than providing protection, thus emphasising their victimhood and peacefulness.Footnote 96

A similar narrative is established in Uzbekistan where an article about the ‘humanitarian operation’ to rescue Uzbeks from Syria and Iraq was posted on the official website of the President Shavkat Mirziyoyev. In the article the President argues that citizens left Uzbekistan ‘due to delusion’.Footnote 97 Moreover, featured photos depict children and women kissing the ground of the ‘homeland’ upon arriving in Uzbekistan whereas returning men are not shown. This narrative demonstrates how gender stereotypes are guiding the presentation of these foreign fighters, where women and children depict the benign, peaceful, duped citizens and the men are either not present or clearly portrayed as threatening. The gendered nature of the narrative is further reinforced by Bakhtiyer Babajanov, an expert from the Uzbek Institute for Strategic and Interregional Studies, who states:

Almost all the repatriated women were low-performing students. I think their low level of education encouraged them to leave [Uzbekistan]. It meant they couldn't assess the reality of the world or understand what was truly happening.Footnote 98

Presenting women as unable to understand the ‘reality of the world’ suggests that they are not ideologically committed or threatening but naive and stupid.Footnote 99 This depiction feeds into the narrative that women are passive family members who are being carried along, equating their mental competence with a child's.Footnote 100 It clearly frames women as ‘duped victims’ who need to be guided in the right direction rather than as a threat. So, who is the actor that could guide the vulnerable, naive women? Who could be this hero?

In the foreign fighter narrative employed in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan there is one clear hero: the strong masculine state that provides protection to its citizens. This statist narrative is underlined in the glorified streaming of the rescue missions from Syria and Iraq through state channels.Footnote 101 As outlined above, these missions were not presented as ‘neutral’ repatriation acts but rather as rescue missions from a war zone. Thereby the state and its military, embodied by soldiers in uniforms were rescuing the vulnerable women and children from the foreign land of ‘terrorists’. The pictures from the missions on the Uzbek President's website show soldiers carrying children – who I argue could clearly walk themselves – out of the plane back to the praised ‘homeland’, signalling that the children are now safe with the soldiers.Footnote 102 This narrative underlines what Iris Young calls the masculine state ‘protector’ who safeguards its citizens.Footnote 103

The gendered narrative of women and children being rescued by the masculine state is further emphasised by the celebrations that have taken place to welcome children of returning foreign fighters. The Uzbek Ministry of Preschool Education organised festivities with entertainers and gifts to welcome returning women and children.Footnote 104 But not only the children received gifts, also the women were treated with government benefits and gifts, including sewing machines.Footnote 105 Thus, whereas the Uzbek men were imprisoned the Uzbek women received rehabilitation programmes and benefits that suit feminine gender norms. These resources were provided by the state underscoring it as the masculine provider and protector who helps and rehabilitates the women – the prodigal daughters who took the wrong path. This fosters an understanding of the returning women ‘as passive and vulnerable, perhaps even victims … [not] as active participants in the I.S. project’,Footnote 106 and the state as ‘patriarch’.Footnote 107 Importantly, the gender power dynamics between the state and the non-state actor ISIS underline the rhetoric of the strong, masculine state against the feminised, weak non-state actor.Footnote 108

Another interesting dynamic in the masculine state narrative is the nationalist component. The Uzbek foreign ministry contends that all citizens, regardless of where they are, are ‘under the protection of the Republic of Uzbekistan, and that the state will take all necessary measures to protect their rights and interests’.Footnote 109 Similarly, in Kazakhstan the spokeswoman for Kazakhstan's Air Assault Troops stated: ‘Our country looks after its citizens.’Footnote 110 In Kosovo, the justice minister noted after repatriating 110 citizens: ‘We will not stop before bringing every citizen … back to their country.’Footnote 111 Crucially, in Kosovo the foreign fighters do not stem from a minority group within the population but are regarded as ‘simply Kosovars’, which might decrease the pushback against repatriation from the population.Footnote 112 The Kosovar National Coordinator for Countering Terrorism and Violent Extremism even argued that Kosovar foreign fighters – compared to other European countries where foreign fighters are typically second or third generation ‘immigrants’Footnote 113 – are viewed as having shared traditions and history rendering the rehabilitation easier.Footnote 114 Presenting the returnees as ‘one of us’ and underlining their nationality is a uniting narrative and does not present them as a threat.

The nationalist sentiment also fits with the observation that five out of seven countries in the Unconditional Repatriation category are newly independent states. The countries are, therefore, at an early stage of state formation and eager to legitimise themselves through the construction of distinct national identities. Importantly, state legitimacy requires both international recognition and domestic support and unity. The response to foreign fighters in Kazakhstan achieves both goals simultaneously by broadcasting a national rescue mission that emphasises national identity and unity through the projection of a strong masculine state both domestically and internationally. Additionally, in the Kazakh rehabilitation centres for women and children the women were instructed to sing Kazakh songs, which highlights their Kazakh identity and solidifies the legitimacy of statehood.Footnote 115 The repatriating Balkan states North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo may also still define their identities due to their ‘recently’ gained independence. Implementing a comprehensive repatriation policy might stress that the countries value human rights. Indeed, clearing the human rights record could be viewed as an attempt to come closer to European Union (EU) membership, a process that these countries have been involved in for years.Footnote 116

The ‘villain’ narrative

Among the eight countries in the Deny Repatriation category a ‘threat narrative’ is clearly established. The foreign fighters and their children are framed as villains of the state who are a threat to national security, which serves to ‘justify’ hard measures, such as citizenship withdrawal. This narrative regarding foreign fighters is demonstrated by Andrew Laming, a member of the Australian parliament, who stated that returnees are trying to ‘get back onto welfare payments again’ and that they ‘walked away from Australia and our values’.Footnote 117 Australia's policy mirrors this narrative as they not only revoke citizenship from adults but also from minors from the age of 14.Footnote 118 Similarly, in Denmark the children born to ‘ISIS parents’ do not receive Danish citizenship. The former Minister of Immigration Inger Støjberg stated: ‘Their parents have turned their backs on Denmark, so there is no reason for their kids to become Danish citizens.’Footnote 119 In the United Kingdom (UK) the children are also thought to pose a threat, as a Home Office authority argued: ‘We feel there are legitimate security concerns here. Returnees, even children, are a security risk …’. Footnote 120 Crucially, states that put forward such a narrative create fear and present the returnees and their children as a threat to legitimise their policies. This is epitomised by the British Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson who suggested that foreign fighters should be ‘hunted down and killed’, as ‘a dead terrorist can't cause any harm to Britain.’Footnote 121

The gendered and racialised dynamics of the ‘threat narrative’ are illustrated when considering how female foreign fighters are framed in the Deny Repatriation category. An infamous example is Shamima Begum who was stripped of her UK citizenship right after she had a baby in 2019.Footnote 122 She had left the UK when she was 15 to join ISIS in Syria and is currently detained in al-Roj camp.Footnote 123 To strip Begum of her citizenship, although she left the UK as a minor, shows how convincingly the ‘threat narrative’ had to be constructed. The former Home Secretary who authorised the decision, Sajid Javid, argued that ‘dangerous dual nationals’ who ‘hate our country’ should be prevented from returning to the UK.Footnote 124 He further argued that Begum should go to Bangladesh as her parents are from there, which – from a postcolonial perspective – shows how fragile her citizenship was in the first place. Moreover, the UK Counter Terrorism Commander Neil Basu has publicly referred to her as a ‘bride’, which demonstrates the gendered and neo-orientalist tropes that risk to further bias investigations.Footnote 125 This narrative is echoed in recent research of Begum's case where social media narratives were shown to reflect gendered and neo-orientalist dynamics of a ‘West is best’ rhetoric.Footnote 126 Overall, Begum's case illustrates how the narrative for women foreign fighters shifts from a victimising one in the Unconditional Repatriation category towards a threatening one in the Deny Repatriation category, supporting the respective policy choices of the states. When considering the narratives for male foreign fighters in the Deny Repatriation category it does not seem to change – they continue to pose a threat.

So, if foreign fighters are a threat, even the young children – who remains to safeguard the citizens? Who could be this hero? Again, the state. Although the narratives of female foreign fighters could not be more different in comparison to countries in the Unconditional Repatriation category, the hero in the narrative remains the same. This is illustrated by Australia's former prime minister Scott Morrison, who stated: ‘They [foreign fighters] have to take responsibility for those decisions to join up with terrorists who are fighting Australia. I'm not going to put any Australian at risk to try to extract people from those situations.’Footnote 127 This gendered narrative, which was prevalent in several countries, allows the strong masculine state to protect its citizens and to keep the ‘enemies’ away. Additionally, there are no videos or pictures of repatriations from Syria or Iraq because they are generally not performed in the Deny Repatriation countries. In rare cases where individuals were repatriated, such as a recent case in the UK where one orphan was repatriated due to public pressure,Footnote 128 the repatriation process is kept secret like a counterterrorism operation.Footnote 129

Othering and racialised dynamics in ‘threat narratives’

Another dynamic in foreign fighter ‘threat narratives’ is whether returnees are presented as belonging to society. As outlined above, in the Unconditional Repatriation states foreign fighters are framed as being ‘one of us’. Whereas in the Deny Repatriation group as well as in most Global North countries the narrative engages in a process of ‘othering’. This is achieved through underlining the descendancy of a person in the media or in political debates. For example, this occurs by stating that a Norwegian foreign fighter has Moroccan descendancy and not just stating that the person is Norwegian. Emphasising descendancy racialises the narrative because it underlines that a person is not actually ‘Norwegian’ (read: white). Ironically, the state's ‘othering’ narrative plays into the hands of ISIS because it echoes their propaganda that foreign fighters (read: Muslims) never belonged to the state in the first place.Footnote 130 Besides, commonly cited push factors for joining ISIS have been racism, Islamophobia and the lack of the feeling of belongingness.Footnote 131 Underlining the descendancy of foreign fighters plays into this narrative and emphasises that the person indeed does not belong.Footnote 132 However, discrimination is not only a push factor in the Global North. In Kyrgyzstan, for instance, 90 per cent of foreign fighters are ethnic Uzbeks who are subject to oppression.Footnote 133 Furthermore, discrimination against those who openly practice Islamic traditions has also been a push factor in Muslim-majority states. In certain parts of Tunisia, women wearing a niqab are discriminated against by secular women.Footnote 134 Overall, societal issues that confirm a discriminatory narrative of ‘not belonging’ can present a push factor for foreign fighters (back) into the arms of terrorist groups.

Alongside employing the narrative of ‘not belonging’, some states also strip (dual national) foreign fighters of their citizenship, which strongly underlines the belief that they are a security threat.Footnote 135 Countries in my dataset that make use of this measure are Bahrain, Israel, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, France, Switzerland, the UK, the United States, and Australia. Withdrawing citizenship as a counterterrorism measure is highly symbolic, however, at the same time, it also renders the foreign fighters someone else's problem.Footnote 136 For example, in Belgium it was reported that after stripping the citizenship of a foreign fighter the country has ‘less terrorists’, which is highly misleading.Footnote 137 Withdrawing citizenship appears more like a quick solution appeasing domestic citizens and allaying security concerns than an actual approach to counterterrorism.Footnote 138 It also opens pathways for discriminatory treatment because it is predominantly decided based on evidence of terrorism committed abroad (read: Islamist terrorism) and not cases of domestic terrorism (read: right-wing terrorism), therefore favouring right-wing terrorism.Footnote 139 Moreover, history reveals how revoking citizenship can turn out. In the 1990s foreign fighters in Afghanistan were prevented from returning home and some stripped of their citizenship as a security measure – Osama Bin Laden being the most infamous example.Footnote 140

The reasons why states withdraw dual nationals of their citizenship varies. Yet a common pattern is revealed among Global North states where it is typically discussed for, for example, British-Pakistanis but not for British-Americans demonstrating how neo-orientalist and racialised dynamics drive the policy.Footnote 141 Shamima Begum's case is an illustration of this dynamic where her ethnic background renders her a ‘second-class’ citizen and suggests that she has always been ‘foreign’.Footnote 142 Or, as Shiraz Maher argues: ‘British citizenship is a two-tiered system … because … anyone who can potentially claim another nationality can be stripped of their British citizenship. This impacts the children of immigrants such as myself, all Jews, and anyone from Northern Ireland.’Footnote 143 With the recent changes in the British citizenship bill this dynamic becomes even more pronounced, as the citizenship can be withdrawn without notice.Footnote 144 Crucially, over 80 per cent of the countries in this article's dataset that withdraw citizenship are democracies in the Global North, which pride themselves on their ‘good’ human rights records.Footnote 145 Yet these same states deprive citizenship of children of immigrants, thus creating a ‘two-tiered’ citizenship system. Overall, the racialised and neo-orientalist narrative of foreign fighters in the Deny Repatriation group and in Global North states is epitomised by citizenship withdrawal, which fosters marginalisation and echoes ISIS propaganda.Footnote 146

Conclusion

This article employed several explanations and methodologies to assess the variation in state repatriation policies regarding foreign fighters and their children in Syria and Iraq. The explorative statistical analysis that tested frequent propositions and explanations offered by IR showed they have limited utility in explaining why states choose to repatriate their ISIS-affiliated citizens or not. No strong pattern or common political, economic, or terrorism-related factor appears to explain the variation in policies. The subsequent qualitative narrative analysis informed by an intersectional gender perspective examined the ‘threat narratives’ of various governments. The narrative analysis indicated why some states choose (not) to repatriate by uncovering the racialised and gendered narratives of foreign fighters. To be more specific: why Unconditional Repatriation states portray foreign fighters as victims needing rehabilitation and Deny Repatriation states as villains that threaten national security. Male foreign fighters were presented as a threat throughout the states’ policy narratives. The narratives of female foreign fighters varied. In Unconditional Repatriation states the foreign ISIS-associated women were portrayed as confused victims, whereas in Deny Repatriation states they were presented as threats. Thus, the narrative for female foreign fighters is dichotomous, they are either victims or villains but cannot be both simultaneously. This finding coheres with other research on women who engage in terrorism, including women returnees and supports the claim that more nuanced accounts analysing the women's degree of agency and exploitation are rare in the security literature.Footnote 147

In addition, the analysis demonstrated that the narrative of foreign fighters moves from a uniting, welcoming one – towards an othering narrative, often racialising and externalising foreign fighters. Crucially, in the ‘Villain’ Narrative the states’ racial structures are evident because states’ decision to, for example, withdraw citizenship reveals their two-tiered system where children of migrants’ citizenship is predicated on good behaviour. The fact that most ‘Victim’ Narrative states are in Central Asia and the Balkans could suggest that they are less influenced by racially driven neo-orientalism, which should be investigated in further research.

Interestingly, the hero presented in the narratives, the state itself, remained the same across categories. Most of the countries demonstrate a masculinist protective view of the state who takes care of its citizens, in particular of women and children. This is either as the patriarchal sovereign under whose protection the citizens are safe from the foreign fighters or as the institution facilitating rehabilitation to help foreign fighters.

Overall, by showing how different gendered and racialised narratives construct repatriation policies, this analysis enriches IR theorising by applying a narrative analysis prevalent in critical and feminist security studies in the context of foreign fighter repatriation. An important implication of this analysis is that societies need to address underlying issues of national identity and social inclusion informing their narratives of returning foreign fighters, such as racism, Islamophobia, and gender discrimination. These structural systems of oppression that underlie states’ narratives and practices can fuel the same grievances that attracted citizens to join terrorist organisations in the first place. These grievances include the subordination of women or the ‘othering’ of ethnic minority citizens.Footnote 148 Gendered and racialised ‘threat narratives’ undermine efforts to counter violent extremism. They must be taken seriously and rethought since repatriation, prosecution, and gender-responsive rehabilitation and reintegration of foreign fighters is important to resolve the ongoing humanitarian crisis in the north Syrian camps and relieve the burden from Iraqi and Syrian communities.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Jacqui True for her helpful comments and guidance in writing this article and developing the argument. As well as Dinah Gutermuth and Patricia Salas Sanchez for your invaluable support. I also want to thank the anonymous peer reviewers for their pertinent reviews.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Helen Stenger is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow for the Monash Gender, Peace and Security Centre. Her research investigates intersectional gender dynamics in extremism. Helen's PhD thesis explored the repatriation, rehabilitation and reintegration of ISIS foreign fighters. She worked in the NGO sector implementing community-based strategies to prevent violent extremism while focusing on women's empowerment. Helen holds a Master of Arts in International Relations from Leiden University and a Master of Science in Clinical Neuropsychology from the University of Groningen.

Appendix 1

Figure A1. Overview dataset mapping repatriation policy.

Table A1. Overview dataset mapping repatriation policy per country.

Appendix 2

Table A2. Results of correlations.

Appendix 3

Table A3. Sources for the narrative analysis.