The politics of peace is primarily the internal and external politics of the powerful.

Kenneth WaltzFootnote 1

Emancipation, not power or order, produces true security.

Ken BoothFootnote 2

Introduction

Jeju Island, located 80 km southwest of South Korea’s mainland, is an island full of paradoxes. Its scenic waterfalls, volcanic rock formations, and natural beauty lure South Korean honeymooners and international tourists to the island. It is also the site of the torture and mass killings that took place from 1948–54 following an uprising by leftists on 3 April 1948. In remembrance of this tumultuous past, former president Roh Moo-hyun (2003–7) declared Jeju Island an ‘island of peace’ in 2005. However, President Roh’s progressive government also advocated the construction of a naval base on Jeju Island. Anti-base opposition remained small in scale and scope, limited primarily to coastal villages surrounding the proposed base sites. However, in 2011, the movement escalated and then exploded onto the national scene, rapidly transforming from a local to a transnational campaign.

What appears as an obscure issue on a far-removed island actually has greater implications for maritime security in East Asia. Designed to host Aegis destroyers, the South Korean base may potentially enhance missile defence cooperation with the United States and Japan. As a treaty alliance partner, the South Korean government may also grant US naval vessels port access if requested by the US. Furthermore, the base raises geostrategic stakes for middle powers such as South Korea as they position themselves between growing US-Sino rivalry. Who commands legitimate claims to security and how base politics are framed thus travels beyond Jeju Island and South Korean politics, carrying wider implications for Asian security.

It is no surprise that peace activists and policymakers clash on a number of national security and foreign policy issues. But little understood is how or why such differences occur, especially when both sides profess to make claims advancing peace and security. In effect, why do anti-base activists and policymakers often come to radically different conclusions about the meaning of these concepts and the role military bases play in upholding regional peace and security? Differences are often attributed to disparate political ideologies wrapped around labels such as ‘progressive’ and ‘conservative’. Looking beyond generic labelling, I connect insights from International Relations (IR) and social movement theories to dig deeper into the basic worldviews and assumptions held by anti-base activists and policymakers that perpetuate the politics of peace and security.

Based on ethnographic research in Gangjeong village in July 2012, interviews with activists and policymakers in Seoul and Jeju Island, and an analysis of discourse (understood here as statements and written text) produced by activists and the Republic of Korea Navy, I find that the politics of peace are tied to different worldviews regarding the nature of existing power relations and the legitimacy of state actions on security policy. These differences are partly reflected in whether actors see states or people as the primary object of security. South Korean policymakers tend to view the naval base as a means of protecting national interests and enhancing security in a region embroiled in ongoing maritime disputes. This worldview is embedded in a realist discursive structure – discourse anchored in institutions that reinforce the logic of power politics and state security. Meanwhile, a broad range of local and transnational anti-base activists, while not always unified, challenge what they see as an illegitimate state project leading to greater militarisation, environmental destruction, and the unnecessary uprooting of a peaceful community. Their worldview is reflected in discourse that strikingly resonates with arguments favoured by critical international theorists.

My argument is organised into five sections. Linking IR paradigms to worldviews, Section I connects realism and critical international theory to different logics of peace and security as articulated in the discourse of policymakers and anti-base activists, respectively. Section II chronicles the Jeju anti-base movement from its local inception in 2007 to its transnational pinnacle in 2012. Section III develops a simple conceptual framework for thinking about the Jeju Naval Base in the context of peace and security. Section IV presents the findings from an analysis of activist newsletters and government statements. Section V provides further discussion on the perpetuation of a realist discursive structure among South Korean policymakers and the barrier it creates for anti-base and other peace movements. I conclude with broader implications regarding the politics of peace.

I. Realism, critical theory, and the politics of peace

Rather than address base politics per se, I use the Jeju anti-base episode to think critically about existing notions of peace, security, and power (or what I refer to as the politics of peace and security) where state and societal actors have clashed over the presence of military bases. Why do peace activists and policymakers who both presumably desire peace and security often come to contradictory conclusions about the purpose and consequence of bases? In the Jeju anti-base episode, virtually no middle ground exists between activists and policymakers, making a consensus difficult to reach.

To understand different worldviews about the Jeju Naval Base and its relationship to peace and security, I begin with a general premise that policymakers and activists gravitate towards a realist or critical international outlook when making claims about the naval base and its impact on peace and security. This premise is based on existing arguments in the base politics literature. Policy analysts and some political scientists tend to explore overseas bases at the level of grand strategy, thus treating bases as an enabler of national and regional security as argued by realists.Footnote 3 Others examine base politics as a series of bargains between the US and host states,Footnote 4 or from a bottom-up perspective placing local actors and activists at the centre of analysis.Footnote 5 In a more critical turn, anthropologists and sociologists reveal the disruption military bases bring to local communities, including increased pollution, noise, crime, and violence against women.Footnote 6 Such findings are complemented by authors who take a normative stand and declare US bases as manifestations of global imperialism and domination.Footnote 7 By seeking relief from either Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) problems and/or the structure of US militarism, activists are inclined to adopt a critical perspective of military bases that extend from their existing worldview.Footnote 8

Operating at the broadest level of ideas, worldviews are ‘embedded in the symbolism of a culture and deeply affect modes of thought and discourse … they are entwined with people’s conceptions of their identities, evoking deep emotions and loyalties’.Footnote 9 Different world religions such as Christianity or Islam, or broad economic ideologies such as liberalism or communism are examples of worldviews which shape actors’ preferences, actions, and discourse.Footnote 10 Worldviews might also be captured through the lens of International Relations paradigms.Footnote 11

I do not suggest that activists or policymakers are necessarily cognisant of critical international theory or realism, but only that the claims made by real world actors resonate with theories offered by IR paradigms that help us to analytically parse their assumptions about peace and security. Support for this approach is found among scholars who argue that the logics central to IR theories function as ‘modes of thinking or ways of constructing social reality’.Footnote 12 The relationship between IR theory and policy frameworks has also been addressed by advocates of ‘bridging the gap’ between the academic and policy worlds,Footnote 13 and additionally from scholars who look beyond policy relevance to explain the hermeneutical links between IR theory and the practice of world politics.Footnote 14 Policy actors utilise grand theories such as realism or liberalism to conceptualise the complexities of global politics. They may also refer to academic theories, such as the democratic peace theory, to legitimate or challenge existing policy paradigms.Footnote 15 As Piki Ish-Shalom argues, theoretical constructions may transform into public conventions (or what I refer to here as worldviews), which then translate into political convictions.Footnote 16 A network of actors, comprised of scholars and practitioners among others, helps perpetuate such political convictions through their own practice and discourse.Footnote 17

To better understand the contrasting worldviews adopted by activists and policymakers, I focus on discourse. Central to this approach is the ontological assumption that worldviews, or one’s conception of reality, are both conveyed and shaped through language.Footnote 18 According to Jennifer Milliken, discourses can be seen as ‘systems of signification’ that construct social realities and ‘operationalize a particular “regime of truth” while excluding other possible modes of identity and action’, and that they ‘operationalize a particular “regime of truth” while excluding other possible modes of identity and action’.Footnote 19 From a methodological standpoint, then, discourse is ‘the interactive process of conveying ideas’, enabling researchers to tap into the worldviews of specific actors.

I.i. Realist discursive structure

State policymakers, particularly within the foreign policy and national security establishment, tend to legitimate a realist worldview through words and action.Footnote 20 Whether wittingly or unwittingly, policymakers often create and project a realist framework for addressing national security.Footnote 21 In this framework, international politics is often dictated by the logic of power politics.Footnote 22 Anarchy, or the absence of central authority in international relations, fosters mistrust among states. State policymakers, acting prudently, are therefore compelled to develop and maintain a certain level of capabilities to ensure their security. As such, ‘rational behavior in the context of anarchy inevitably reproduces the very condition of distrust and insecurity which threatens all states … revealing that no state can avoid engaging in the politics of manipulation and control’.Footnote 23 The need for power, the search for security, and the primacy of national interests are constants that motivate states in the international system.Footnote 24 As a type of ‘problem-solving theory’, then, realism ‘takes the world as it finds it, with the prevailing social and power relationships and the institutions into which they are organized, as the given framework for action’.Footnote 25

Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde argue that ‘the distinguishing feature of securitization is a specific rhetorical structure’.Footnote 26 Security practices become publicly legitimised through public discourse. Such ideas about discourse and structure advanced by the Copenhagen School of International RelationsFootnote 27 resonate with the concept of discursive opportunity structure developed by social movement theorists and defined as ‘institutionally anchored ways of thinking that provide a gradient of relative political acceptability to specific packages of ideas’.Footnote 28 Discourses, of course, are a relational product, produced and reproduced between challengers and power-holders.Footnote 29 A dominant discourse is thus shaped by power relations. Discursive opportunity structures may resonate with similar concepts such as discursive hegemony or hegemonic discourse. The concept of discursive opportunity structure, however, gives particular attention to the ‘structured’ (either culturally or institutionally) nature of discourse, particularly as it becomes anchored in key political institutions.Footnote 30 Moreover, the concept draws on broader theories of political opportunity structure found in the social movement literature that indicate why ‘certain actors and frames are more prominent in the public discourse than others’ and how discursive structures, as external opportunities or constraints, embolden or weaken movements.Footnote 31

More than merely talking like a realist, then, a realist discursive (opportunity) structure suggests that realist security ideas and the discourse espoused by policymakers are very much embedded within institutions. For instance, during the Cold War, US policymakers, think tanks, and government agencies all converged around ideas such as containment or the balance of power which were then reflected in US strategic doctrine. Containment, domino theory, mutually assured destruction – strategic concepts all based on realist principles – in effect became institutionalised policy. Security interests, or how policymakers come to determine national interests more generally, are in part discursively constructed.Footnote 32 Needless to say, the presence of a realist discursive structure perpetuates a worldview advancing realism, including the need for military bases to defend national security interests.

I.ii. Critical international theory and activism

Peace activists often reject the security arguments (and hence the realist discursive structure) evoked by state policymakers. To some degree, the claims raised by peace activists’ against state security policies often resembles the attacks launched by critical IR theoristsFootnote 33 against the realist paradigm. Whereas realism provides a guide to action that sustains the existing order, critical theory calls into question existing social and power relationships and the institutions they are encased in.Footnote 34 The turn to critical theory therefore brings two fundamental challenges to realist and rationalist traditions in international politics.

The first is critical theory’s promotion of freedom and human emancipation from physical and human constraints such as war, poverty, and oppression.Footnote 35 As Andrew Linklater argues, ‘Critical theory investigates the prospects for new forms of political community in which individuals and groups can achieve higher levels of freedom and equality … its inquiry is oriented towards the realization of truth and freedom.’Footnote 36 Second, critical theorists challenge the realist’s ‘immutability thesis’, which assumes that political communities are unable to escape the logic of power and self-interest under the conditions of anarchy. Unlike realists who seek to explain repetition and recurrences within the anarchic system, critical perspectives assume the possibility of an alternative order. Thus, critical theorists try to identify ‘counter-hegemonic or countervailing tendencies that are invariably present within all social and political relations’.Footnote 37 At the heart of critical theory then is its belief in change and the desire to break free from the dominance of prevailing social relationships that perpetuate inequalities. Progressive political transformation can ‘upend entrenched centers of power’, thereby freeing individuals from the dominant forces shaping their lives.Footnote 38

Activists question the existing security ‘reality’ constructed by the state and question both the state’s use of power and existing power relationships between state and society and between states in the international arena. Rather than accepting a fixed political order as defined by existing social relations, activists mobilise to create an alternative discursive space that frees individuals from that order. Security problems must be examined holistically. Therefore, one cannot protect the national interest at the expense of violating human rights or abusing the environment. Moreover, peace activists break from a value-free assessment of the national interest and strategic decision-making, and try to provide a guide for action leading to an alternative (peaceful) order.

Counter-discourse and political communication become instrumental in challenging the realist worldview advanced by state policymakers. In democratic contexts, ‘lies and other deceptive communicative practices can be revealed and powerful actors can experience the collapse of their public standing and legitimacy … communicative action that promotes normative consensus and reduces the distorting influence of material power in a public discourse can help create political structures that reflect “legitimate” social purpose.’Footnote 39 Evoking a Habermasian response to state claims and action, activists seek emancipation by ‘evoking a crisis of consciousness at the periphery’ and enlarging the public sphere.Footnote 40

The true test for activists in challenging the state on national security issues, however, is mobilising a wider segment of society to counter the dominant realist discursive structure. Even when peace activists find a compelling cognitive frame that resonates with society (that is, democracy or human rights) and individuals are hit with a crisis of consciousness, the state exercises its power to counteract opposition.Footnote 41 This can be done through coercive means such as police suppression, or by co-opting more moderate factions within a movement. Such counter-movement strategies demonstrate the state’s material levers of power. However, the state also exercises its power through ideational means. In addition to discrediting the motives of activists as disingenuous, state policymakers reinforce the realist discursive structure and legitimate their actions by articulating and linking specific security initiatives to the national interest. Unable to ‘penetrate’ the state or find sympathetic allies inside the security or foreign policy establishment, success on the mobilisation front becomes much more difficult to translate into success on the policy front.Footnote 42 Below, I show how the politics of peace is articulated and framed by activists and South Korean policymakers through the Jeju anti-base episode and explain how the presence of a realist discursive structure functions as an ideational barrier against anti-base movements. I begin with a brief narrative of the anti-base movement on Jeju Island.

II. The Jeju anti-base movement

II.i. From local to global

How did a tiny movement in a local fishing village manage to transform into an international anti-base movement? Plans to build a naval base on Jeju Island, located 80 km southwest of the mainland, first emerged in 2002. After facing local opposition from two other nearby villages, the South Korean government chose Gangjeong village as the new base site in May 2007.Footnote 43 Although villagers were given the opportunity to vote on the proposal, most anti-base residents boycotted the town hall-style meeting. Part of this resistance stemmed from accusations that the ROK Navy, having already been rejected twice by villagers on other parts of the island, had negotiated backroom deals with key villagers prior to any public discussion.Footnote 44 The provincial and central government’s hasty decision in selecting Gangjeong as the future base site thus marred the legitimacy of the base project in the eyes of activists and a segment of Gangjeong residents.Footnote 45

Until late 2010, the anti-base movement was limited largely to Jeju Island. Local residents angered by the Jeju government’s failure to follow democratic procedures in the base site selection organised their own movement. Although some Korean activists and NGOs outside of Jeju Island drew attention to the base issue, their role remained limited.Footnote 46 At the time, anti-base activists were already engaged in another campaign against base expansion of a major US army base in Pyeongtaek located 50 km south of Seoul.Footnote 47 Additionally, Gangjeong residents did not completely trust ‘outside forces’ from the mainland entering their struggle.Footnote 48 Anti-base opposition therefore remained local.

The situation reached a new level of urgency upon the arrival of construction trucks in January 2010. Casting aside concerns about local-national tensions, the mayor of Gangjeong village, Kang Dong-kyun, made an appeal to anti-base activists at the national level to join in solidarity in opposing naval base construction. Several peace organisations alerted their members via email and web-postings about the Jeju base issue.

The national coalition-building effort also helped diffuse information about the Jeju issue at the transnational level. Acting as an important link between the national and transnational dimensions, Choi Sung-hee, an artist and leading peace activist based in Seoul and a member of the board of directors of the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space (Space for Peace), alerted other board members about the base struggle in Gangjeong village. Bruce Gagnon, serving as the coordinator of Space for Peace, responded by circulating an international petition opposing the naval base to submit to the South Korean and US governments.Footnote 49 Messages of solidarity were sent to Gangjeong from activists in Vieques, Puerto Rico, who recalled their successful struggle to close down a US Navy bombing range, and from ongoing anti-base campaigns in Okinawa and Vicenza, Italy. Several international peace and environmental activists later travelled to Gangjeong village to support residents and anti-base activists.

Despite efforts to mobilise a broad national and transnational anti-base movement, it was not until the arrest and hunger strike of a notable South Korean film critic, Yang Yoon-Mo, that the Jeju base issue began attracting attention from the mainstream South Korean media. News of Yang’s arrest in April 2011 (for lying underneath a concrete truck to halt base construction) spread through South Korea, particularly among the arts community.Footnote 50 Yang’s hunger strike led to appeals from residents and activists in South Korea on social media sites including Facebook and Twitter. On 8 June 2011, South Korean activists launched a broad coalition campaign with 140 organisations under the banner, ‘National Network of Korean Civil Society for Opposing the Naval Base on Jeju Island’.Footnote 51 Local residents were also supported by a growing number of Korean Catholics with a strong endorsement from Bishop Kang Woo-il, the head of the Jeju Diocese. Through the Catholic Justice and Peace Committee, clerics and priests nationwide formed the Catholic’s Solidarity to Realize the Jeju Peace Island.Footnote 52

International peace groups issued statements of solidarity and spread information about the naval base within their own respective networks, helping the Jeju anti-base movement to raise funds and mobilise resources. International peace activists also coordinated efforts to support Gangjeong residents in their struggle against naval base construction by forming an international advisory board and visiting Jeju Island. The emerging transnational movement received a boost when renowned activist Gloria Steinem penned an op-ed in the New York Times on 6 August describing the militarisation of Jeju Island.Footnote 53 This was followed by three more stories featuring Jeju anti-base opposition in the New York Times within the next month.Footnote 54 Jeju anti-base protests were also reported by Le Monde, Al Jazeera, the BBC, and the Washington Post, among several other international news outlets in 2011. By then, a handful of activists from abroad and the mainland had moved to Gangjeong in solidarity with the local resistance movement.

II.ii. Peace and life frame

Both local and international activists developed a ‘peace and life’Footnote 55 frame by juxtaposing the natural beauty and ecosystem of the island with the large, impending naval base; holding daily Catholic mass, protests, and vigils outside the base site; and evoking the past pain of the Jeju massacre. Jeju Island’s geographic and historical context made the peace and life frame especially compelling to outsiders, and the peace and life frame aided activists in transforming a local NIMBY movement into a transnational one with widespread appeal from peace, environment, human rights, and religious groups.Footnote 56

First, recognising its natural beauty, UNESCO designated Jeju Island as a world heritage island in 2007. The destruction of a complex ecosystem for the sake of a large military base drew the attention of environmentalists in particular. This was reinforced during the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) World Conservation Congress, held on Jeju Island in September 2012, where 269 delegates, mostly from NGOs, supported a resolution to ‘protect the people, nature, culture, and heritage of Gangjeong village’.Footnote 57

Second, the legacy of the 4.3 Massacre loomed behind the Jeju Naval Base struggle. Transnational activists previously unfamiliar with Jeju’s history saw the anti-base struggle in an entirely different light upon hearing stories of immense suffering on Jeju Island when South Korean forces (under the auspices of the US military government) rounded up and massacred 30,000 suspected leftists between 1948–9. Through a peace and life frame, residents, activists, and notable figures such as the Archbishop of Jeju Island managed to link the 4.3 Massacre to the current struggle in Gangjeong: Jeju islanders had already suffered once at the hands of the South Korean government. They should not have to suffer a second time. However, the state was now violating its own claim by constructing, as one interviewee put it, ‘an instrument for war’ on an island it had officially declared an ‘island of peace’.Footnote 58

Third, activists’ portrayal of the contrast between peaceful demonstrations and ‘violent’ actions executed by riot police reinforced the peace and life frame. As protests grew stronger, the South Korean government dispatched hundreds and later thousands of riot police to prevent activists from interfering with construction plans. Clashes between riot police and activists thus escalated in size and in level of violence between late 2011 and early 2012. On social media sites and newsletters, activists juxtaposed images of violent clashes and physical destruction of the Geurombi rock along Jeju’s coastline with images of Jeju’s natural environment and peaceful village life within Gangjeong. A daily Catholic mass held outside the base, and periodic confrontation between police and mass participants (including priests and nuns being forcefully removed), also helped strengthen the peace and life frame used by activists. This brought wider appeal for the Jeju anti-base movement from abroad, particularly among Catholic peace groups such as Pax Christi International. In short, a combination of favourable political opportunities, available resource networks, a compelling cognitive frame, and the use of social media contributed to the movement’s rapid shift in size, space, and scope in 2011.

II.iii. The state clamps down

From August 2011, anti-base activists followed a routine of daily protests, vigils, and sit-ins, periodically broken by the occasional clash with riot police along with the arrest and release of various protestors. However, in early March 2012, the Jeju base issue escalated once more with the ruling and main opposition parties in South Korea turning the base construction issue into a national election agenda. The government took more coercive action, relying on a range of physical, legal, and economic measures to undermine local resistance and transnational opposition.

The ROK Navy constructed a 12-foot wall around the entire base construction site to prevent base opponents from trespassing. Local plainclothes police officers were joined by hundreds of riot police from the mainland to monitor and physically block protestors from interfering with base construction. Meanwhile, the Jeju provincial and South Korean supreme courts ruled in favour of the government, underscoring the legality of base construction. At the same time, police detained and arrested activists and movement leaders on charges of trespassing and obstruction of official business.

To undermine support from abroad, several international activists deeply involved in the Save Jeju campaign were eventually deported. Most notably, French activist Benjamin Monnet, one of the first international activists to relocate to Gangjeong, was arrested and deported on 12 March 2012 on charges of unlawful interference with official duty, misdemeanor, infliction of injury, and obstruction of business. ROK immigration officers banned Monnet from returning to South Korea for five years. Other international activists travelling to Jeju with the intention of supporting anti-base activists were denied entry by South Korean immigration officials at the airport, including three US Veterans for Peace activists.Footnote 59

Despite such actions, transnational activism continued. Activists in London, Paris, Berlin, Seattle, Washington, DC, New York, Boston, and San Francisco continued to organise protests, screen documentary films, and host events and panels featuring residents and activists from Gangjeong. For instance, activists in New York City organised a New York Save Jeju Action Committee with participation from the Korean-American community, students, church groups, and peace groups such as Grannies for Peace and Veterans for Peace who mobilised activists within their respective networks.Footnote 60 On 11 December 2013, the City of Berkeley in California passed a symbolic resolution calling on the US government to cease support for the Jeju Naval Base. Although anti-base activism peaked in 2011–12 as captured by the number of ‘likes’ on its Facebook page in Figure 1, activists in Gangjeong continued to hold protests and their daily Catholic mass outside the near completed base at the end of 2016.Footnote 61 In the next section, I analyse the politics of peace and the ensuing clash between activists and state actors by examining their discourse.

Figure 1 Number of ‘Save Jeju Island’ Facebook page likes from August 2011 to December 2013, available at: {https://www.facebook.com/SaveJeju}

III. Conceptual framework and methods

Although some constructivist security scholars readily adopt a positivist approach to studying discourse,Footnote 62 researchers on the more critical end of the epistemological (and ontological) spectrum have been criticised for not substantiating their theoretical claims with greater empirical work.Footnote 63 As Karin Marie Fierke notes, the distinction between ‘positivist’ empirical research and ‘postmodernist’ discourse analysis ‘presumes that empirical research and discourse analysis are mutually exclusive methods’.Footnote 64 Critical theorists have contributed to this dichotomy by shunning ‘mainstream’ social science and treating their own enterprise as a post-positivist project.Footnote 65

The methodology adopted in this article answers recent calls to promote epistemological bridge building.Footnote 66 More concretely, I analyse text from anti-base activists and the ROK Navy to substantiate the existence of contrasting critical and realist worldviews underpinning actors’ assumptions about peace and security.Footnote 67 I begin with the general assumption that policymakers and activists adopt either a realist or critical framework when making claims about the Jeju Naval Base. I then construct a simple coding scheme involving two sets of questions that distinguish a realist perspective from a critical one and vice versa. First, whose interest is at stake regarding the Jeju Naval Base? For whom is the base being constructed? Here, the key distinction is between state and societal/individual interests. Do words and statements place an emphasis on state interests? Or do they highlight the importance of human interests? A realist perspective should be corroborated by statements and text supporting a state-centric view. The naval base should reflect the priorities of the state explicitly linked to the national interest. On the other hand, a critical perspective should be supported by statements focused on communities and people encouraging emancipation from the state, and in particular from the destructive effects of the incoming naval base.

Second, how does the base relate to security issues? Does the base promote security, stability, and peace, or is the base a source of insecurity, conflict, and destruction? The discourse of policymakers and activists tends to support a ‘dominant’ realist view of security linking the Jeju base to national defense or a critical view, which suggests that the base will militarise and destabilise the region.

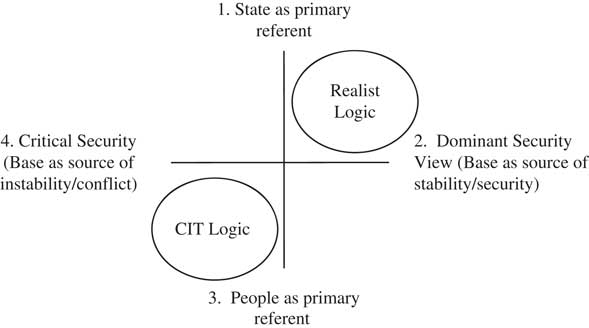

Applying a method that finds a middle ground between the systematic rigour of content analysis with the subtle nuances of discourse analysis,Footnote 68 I use these two sets of questions to produce a simple coding scheme presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Coding scheme mapping realist and critical worldviews.

Statements and words coded as (1) upholding state interests over other interests and/or (2) promoting the dominant security view linking the Jeju base to national security generally fall under the purview of the realist worldview. The far northeast quadrant represents an ideal type realist worldview that belies the dominant discursive structure (re)created by policymakers. Statements and words coded as (3) supporting human/societal interests and/or (4) promoting a critical security view that links the Jeju base to instability or adopts a human security angle by emphasising individual life, human or civil rights, or the environment fall under the perspective of the critical worldview.Footnote 69 The far southwest quadrant represents an ideal type critical perspective.

I constructed a list of key words and phrases used to code for a particular category.Footnote 70 An initial list was created by first analysing official statements about the naval base provided by the Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Foreign Affairs and press releases and pamphlets published by civil societal groups and Jeju anti-base activists. I then analysed documents directly produced by transnational activists and the ROK Navy, respectively. Specifically, I analysed the monthly newsletter Gangjeong Village Story produced by activists residing in Gangjeong from December 2011 to July 2012.Footnote 71 I also examined online documents about the Jeju base made available on the ROK Navy’s webpage in 2012.Footnote 72

To supplement textual analysis, I also conducted interviews with anti-base activists and South Korean policymakers and security experts.Footnote 73 Additionally, I spent ten days in Gangjeong village as a participant observer, interacting with activists and local residents. This included participation in evening vigils, observing the daily Catholic mass outside the main base gate, witnessing clashes between riot police and activists, and watching base construction from the Jeju coastline. Ethnographic data provided additional context and meaning to activists and policymakers’ words and actions.Footnote 74

One might criticise the relationship between ideas, discourse, and action as tautological if discourse itself shapes particular thought patterns and practices. Indeed, the constitutive relationship between discourse and worldviews means causal relationships cannot be fully determined. However, finding correlational patterns that link worldviews to a particular set of discourse does allow for interpretation and explanation of the contention surrounding the Jeju base. Of course, this begs us to ask why and how activists and policymakers consistently come to different conclusions about peace and security – a question I address towards the end of this article.

IV. Discourse and content analysis

IV.i. ROK Navy (ROKN)

Tasked with the organisational management of base construction, the ROKN presented the South Korean government’s rationale for building the base on Jeju Island and planned measures to address political and environmental concerns raised by activists and residents. An analysis of relevant documents (that is, documents explaining the purpose, function, and process of base construction) reflects a strong realist security mindset from the ROKN (and by extension the South Korean national security establishment that endorsed the ROKN plan). National interests trump other regional or local interests, and peace and security are framed in almost entirely military terms. Designed to address strategic shortcomings, the base represents peace and stability for the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia.

The pages most relevant to this analysis were a series of four statements released by the ROKN in response to activist grievances.Footnote 75 Here I discuss the two statements most directly related to the problem of peace and security. The first statement addresses whether a naval base needs to be located on Jeju Island. All five paragraphs of the statement evoke the national interest. For example, the statement begins by stating that 99.8 per cent of South Korea’s exports and imports are transported by ships with the vast majority passing through Jeju’s waters south of the Peninsula. The southwest sea-lane serves as South Korea’s ‘life line’. A national crisis would ensue if this passage were blocked beyond 15 days.Footnote 76 The ROKN argues that the absence of a major base on Jeju means that naval forces in Mokpo, Pusan, or Jinhae have to be dispatched to protect Jeju Island. Furthermore, no base outside of Mokpo can host the type of large vessels the ROKN plans to anchor on Jeju Island. The Jeju base therefore provides a rapid, ready response to threats off Jeju Island’s coast.

The second ROKN statement justifies how a naval base can exist on an ‘island of peace’. The statement notes that it was former president Roh Moo-hyun who declared Jeju Island an ‘island of peace’ in 2005. However, it was also President Roh who argued that ‘neither peace nor the nation can persist without arms … were a situation to arise in Jeju waters, naval power would be needed’.Footnote 77 The ROKN contends that ‘peace does not mean the existence of a demilitarized zone. Rather, it can only be achieved by strengthening national security.’Footnote 78 The Navy also argues that the Jeju Naval Base exists for defensive purposes. The Navy claims, ‘The base is being built not for war, but to secure sea lanes and protect the peace in order to prevent war.’Footnote 79

Additionally, I analysed a primer published by the ROKN titled, ‘Jeju naval base must be constructed for the Republic of Korea and Jeju Island.’Footnote 80 The primer offered four major arguments. First, the Jeju Naval Base projects a twenty-first-century blue water navy that protects South Korea’s national wealth and national security. Second, the base allows South Korea to operate a naval power hub. Third, the base allows South Korea to provide a foundation for peace by relying on its own strength. Finally, the base provides a homeport to protect ‘our backyard’ and ‘our (national) security’.

Using the above text, the Navy’s discourse falls predominantly in the northwest quadrant of Figure 2. The base is built to protect the national interest. State interests override local or individual interests. The Navy’s discourse supports the dominant security view. The base is presented as a vital part of national security. It is a source of peace and stability for the region.

This is not to argue that the Navy completely ignores the needs and interests of the local community or other issues such as the environment. For instance, an introductory message from the ROK admiral managing the base project contends that the project is a joint effort between the Navy and the Jeju people. The base contributes not only to national security, but economic revitalisation of the island through business and tourism. The message also gives mention to an eco-friendly construction process.Footnote 81

Iv.ii. South Korean and international activists in Gangjeong

An analysis of newsletters produced by activists residing in Gangjeong (and supplemented by personal interviews), demonstrates that activists assign an entirely different meaning to the naval base from the South Korean military. Their understanding of peace and security begins with life in Gangjeong village and providing security for individual residents and the environment. International activists in Gangjeong began publishing Gangjeong Village Story (GVS) in September 2011. The newsletter averaged 16 headlines per issue between December 2011 and July 2012. I categorised each headline as main articles, event postings and announcements, or solidarity and support letters. Most of the headlines focused on issues taking place within Gangjeong. This included information about rallies and conferences, police arrests and police suppression, and updates on environmental issues resulting from base construction. Activists also published reports and letters written by international supporters living abroad.

Activists claim that ‘true peace and security’ means protecting life, and to ‘live peacefully without feeling insecure’.Footnote 82 They ask whether the current base construction project gives life or if it is something that takes away life. Peace, according to one local activist, is to ‘live life and provide conditions that enable one to enjoy that life’. The activists’ role, then, is to reveal to local villagers and the broader public the political implications behind the base project and the destruction it brings. As one activist passionately remarks, ‘the truth about this must grow as we search for a more equal, non-violent society’.Footnote 83

A few sample headlines highlight the basic message of activists framed around life, peace, democratic rights, and the environment: ‘You, Gangjeong, you are the smallest village even in Korea, but the peace of the world will begin from you’ (GVS, December 2011); ‘Stop the navy and police violence against people!’ (GVS, September 2011); ‘Gangjeong for the life and peace village, Jeju for the world peace island!’ (GVS, February 2011); ‘Police violence leaves activist on crutches’ (GVS, July 2012); ‘Human rights are in great danger, regardless of gender, age, nationality’ (GVS, April 2012); ‘Urgent: Stop the dredging, stop the blast of the Gureombi rock!’ (GVS, February 2012).

Contrary to my expectations, only a limited number of headlines/articles framed the Jeju Naval Base in the context of regional or global peace. Activists (both local and transnational) primarily focused on local issues and actions. For instance, nearly every issue drew attention to police violence, destruction of land and property, and ‘illegal’ arrests. The newsletters were also consistent in their demands to halt construction and protect the environment. To the extent that peace issues were addressed, articles and headlines were framed in terms of life and peace for the villagers. Police abuse and arbitrary arrests were frequently framed as a human rights problem (GVS, February 2012).

Analysis of the newsletters suggests that activists fall within the critical worldview space (southwest quadrant) of Figure 2. For activists, local interests are at stake. The naval base destroys the environment, the local community, and the livelihood of Gangjeong residents through forced displacement. Headlines and articles indicate that human security trumps national concerns. Residents and activists should live free from oppression by the police, from corporate interests, and from the government who justify their actions in the name of national security. To a lesser extent, activists link the base to regional instability and insecurity. As two supporters of the anti-base struggle write in the inaugural September 2011 newsletter, ‘The consequences of losing the struggle to prevent the base construction might impact not only Asia but the United States and the rest of the world as well.’

In sum, discourse analysis reveals different cleavages in the interpretation of the Jeju base in relation to peace and security between activists and the ROKN. The ROKN (and security policymakers more broadly) projects a realist worldview and link the Jeju base to national security. Activists, on the other hand, challenge the Navy’s discourse by shifting the focus from the national interest to local needs. Taking a critical approach, activists question the legitimacy of the base project and the moral authority of the state as the police begin to crack down on anti-base activists and residents.

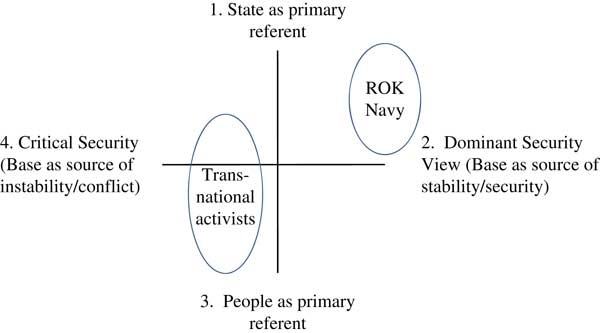

A mapping of ROK Navy and activist discourse is presented in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 Mapping of activists and policymakers.

Although I treat local and transnational activists as a singular group, in reality, most local activists would find themselves in the southwest quadrant, and international activists somewhere in between the south and northwest quadrant. In other words, international activists are more likely to highlight the wider geopolitical implications of the Jeju Naval Base in addition to its adverse impacts to the local community. As anti-base contention shifted from the local to transnational, so too have activists bridged and extended a ‘peace and life’ frame to adopt both tangible NIMBY issues and less tangible concerns regarding militarisation and regional peace.

V. Discourse, national security, and peace

An analysis of words and statements makes it clear that the South Korean government, the military, and supporters of the base see the Jeju base linked first and foremost to national security and state interests. Policymakers frame the Jeju base in the context of a realist worldview. Prudence and the national interest dictate the necessity of the Jeju base. Government officials justify base construction on the grounds of maintaining secure maritime transportation routes in the southern sea-lane. South Korean officials have also cited China’s assertiveness in territorial disputes as a reason for strengthening its naval capabilities. In a region where security is less then plentiful, government officials argue that peace and prosperity is maintained from a position of strength.

For peace activists, anti-base residents, far-left politicians, and to a lesser extent main opposition party members, the Jeju base is an issue about democratic rights and representation, ecological and environmental destruction, economic livelihood, and peace. Based on an analysis of newsletters, the majority of residents and activists in Gangjeong adopt a human security perspective of the base and its purpose and impact on people. The government has failed to live up to its moral purpose by not respecting the democratic rights of villagers and destroying their livelihood. Far from providing security, the state has ruined an entire community for the sake of building a base that is unnecessary at best and destabilising for the region at worst.

Activists claim that ‘true peace and security’ means protecting life, and to ‘live peacefully without feeling insecure’.Footnote 84 They ask whether the current base construction project gives life or if it is something that takes away life. Peace is to ‘live life and provide conditions that enable one to enjoy that life’.Footnote 85 The activists’ role, then, is to reveal to local villagers and the broader public the political implications behind the base project and the destruction it brings. As one activist passionately remarks, ‘the truth about this must grow as we search for a more equal, non-violent society’.Footnote 86

What do these different discourses suggest about the politics of peace on Jeju Island? Although I do not make any strong causal claims in this article, one implication is the important barrier of discursive structures confronting peace activists on the Korean Peninsula. Aside from the immediate goal of halting base construction, activists seek to shift the public discourse on peace and security. However, South Korean policymakers – particularly in the foreign policy and security establishment – maintain a realist worldview sustained by (and reflected in) a realist discursive structure.

The realist discursive structure dominating the South Korean national security establishment is a manifestation of South Korea’s status as a divided nation and the country’s reliance on the US-South Korea alliance. Shaped by anti-communist ideology, the legacy of the Korean War, and animosity towards North Korea, a dominant security discourse in South Korea emerged during the Cold War. This narrative was embedded and reproduced by domestic institutions, most notably the National Security Act used to restrict anti-state activities and ban communism. Although rules and institutions in themselves do not ‘cause’ political action, it is the discursive practices associated with institutions that ‘shape the behavior of what actors do’.Footnote 87

South Korean policymakers thwart challenges to a realist discursive structure by disciplining activists and politicians who make public declarations deviating too sharply from the prevailing realist worldview. This does not suggest complete uniformity in policy views by all policymakers, but it does prevent alternative security ideas and discourse from diffusing vertically (that is, from civil society to elites) or horizontally (towards the broader public). For example, those calling for unconditional engagement with North Korea or an abandonment of the US alliance are branded as radicals and thus sidelined from key debates on foreign policy and national security issues. In the same vein, the existing realist discursive structure shapes how ‘peace and life’ frames adopted by anti-base activists are received by the South Korean political elites and the mainstream public. This logic corroborates what realist E. H. Carr noted about international politics: ‘Theories of social morality are the product of a dominant group which identifies itself with the community as a whole, and which possesses facilities denied to subordinate groups or individuals for imposing its view of life on the community.’Footnote 88 As E. H. Carr explained, the interests of the privileged are therefore assumed to reflect the interests of the nation as a whole.Footnote 89 Those who challenge the ‘national interest’ are silenced or marginalised.

Although some national activists rely on realist assumptions to challenge the state’s logic for advancing new security initiatives (by claiming the base may trigger a security dilemma with China), on the whole they reject the realist worldview espoused by policymakers. They assume that the ‘national interest’ itself has been highjacked by government and corporate interests where dominant groups usurp power at the expense of the weak. A common theme raised by activists in statements and interviews is the source of peace. As one activist stated, ‘Peace does not come from bases or the military, but from freedom and relationships with people at the individual level and community.’Footnote 90 Activists in Gangjeong desire freedom and emancipation from what they see as an imposition by force of the naval base on Jeju Island. They seek to challenge the dominant paradigm and promote an alternative vision of peace and security centred on people rather than states. As Kim Jong-Il, a leading peace activist in the Jeju anti-base movement states:

When the government talks about national or state security, they mean protecting national borders – the territory inside the boundaries of the state. This may have adequately described national security up true up until the early 20th century … But this is the 21st century, yet the government has not changed its thinking of what security is. It still thinks about national security in terms of territorial integrity. Norms and laws today make this form of security less important. State security should also address political rights of people.Footnote 91

Kim and other activists bemoan the government’s use of national security to clamp down on activists and residents. Kim states, ‘The problem with the South Korean government is that once it utters national security, or claims that something is being done for the sake of national security, no one can challenge this. The term “national security” silences everyone.’Footnote 92 According to seasoned South Korean activists, the government promotes a dominant ‘security ideology’ that conjures fear and threats. While a realist discursive structure is not the only barrier facing anti-base activists on Jeju Island, Kim’s comments do suggest that the challenge in translating mobilisation success into effective policy change hinges as much on ideational constraints as it does on material factors such as the depletion of resources or brute force exercised by the national police.

Pushing the question one step further, why do the worldview of policymakers and activists diverge on issues pertaining to peace and security? Although beyond the scope of this article, the answer is likely some combination of dispositional and situational factors that shape one’s worldviews, reified through processes of socialisation. Policymakers and bureaucrats are often socialised into specific patterns of thinking that translate into acceptance of one set of policy beliefs over another.Footnote 93 Similar to the dominance of neoliberal thinking in global financial institutions, realist thinking often dominates the halls of security and foreign policy institutions.Footnote 94

For activists, significant life experiences during one’s early formative years play a role in shaping one’s assumptions about social justice, peace, and attitudes towards the government.Footnote 95 These ideas are reified within activist circles through education, but more importantly through shared experiences and collective struggles that leave an indelible imprint on activists’ beliefs and worldviews.

Interviews with approximately two dozen activists in Seoul and Jeju Island do support the socialisation hypothesis briefly mentioned earlier. Religion, one’s upbringing (that is, whether one grew up poor), and significant life experiences all play a role in shaping the assumptions embraced by activists about social justice, peace, and attitudes towards the government. Of all these explanations, significant life experience, particularly in early adulthood, appears most central in shaping activists views towards a critical perspective. For older activists, their experience in South Korea’s democracy movement and firsthand accounts of state repression and brutality played a significant role in shaping one’s views about political life. For younger activists, it was exposure to new ideas and experiences during college that brought about change in their political thinking. A common theme raised by activists young and old was a general distrust in government arising out of particular experiences from their formative years and hardened through activism. Therefore, the actions of the state, and the realist discursive structure promulgated by policymakers and used to justify naval base construction, is perceived as illegitimate.

Conclusion

The politics of peace is often an outgrowth of different worldviews and assumptions about the state’s role as a provider/guarantor of security and the nature of international politics. Using two different International Relations theories as the basis for opposing worldviews, those who accept the realist worldview accept military bases as a normal part of a state’s national security agenda. Given the uncertainties of international politics, bases are unproblematic so long as the purpose is to defend the national interest. Foreign policy and security officials, particularly in the conservative party, adopt and project this logic, perpetuating a wider realist discursive structure within South Korean society. In contrast, anti-base activists adopt a broader perspective on peace and security. They connect the base not only to regional (in)security, but also consider its impact on the environment, economy, and the local community. Far from providing security, the government has destroyed an entire community for the sake of building a base that is unnecessary at best and destabilising for the region at worst.

Those who take a critical position against bases tend to approach peace and security issues from the bottom up. That is, an emphasis is placed on people and communities rather than the state. Traditional security is replaced by human security. Anti-base activists have challenged dominant ideas about security through protest and discourse through this critical paradigm. In the process, they have assigned a different meaning to the naval base, reinterpreting its existence from a defensive capability to an offensive instrument of war.

Beyond Jeju Island, the arguments raised here apply to the politics of peace elsewhere. For instance, protestors have staged a NATO counter-summit the past several years to parallel NATO summit meetings. Whereas most US and European defence officials along with the broader public support NATO and see the alliance as contributing to peace and stability in Europe, peace activists refer to NATO as an American instrument for imperialism and militarisation. Rather than provide peace and stability, NATO has brought death and destruction to places such as Afghanistan. Like Jeju anti-base protestors, the counter-summit activists adopt a critical framework that challenges conventional wisdom on the meaning and purpose of NATO. Meanwhile, policymakers tend to speak about NATO in terms of regional defence and security, a view underpinned by a transnational realist discursive structure.

We presume that people and states prefer to pursue peace and security to war and insecurity. A careful analysis of discourse, however, helps us better understand how different actors conceive of these concepts and why particular security and foreign policy decisions become fraught with tension. The politics of peace will be most salient at the intersection of traditional and human security and where conflict (or preparation for conflict) encroaches on the lives of the individual.

Future research should further probe how discourses shape policy outcomes, and in particular why the national security narrative often wins out against a human security or more local narrative.Footnote 96 Part of the answer lies in the power of the state, which reflexively places national over individual interests. In translating International Relations into practice then, one suggestion for activists in challenging the dominant narrative is to frame ideas and discourse within ‘institutionalized ways of conceptualizing problems and solution’.Footnote 97 Thus, anti-base activists may gain more traction by framing their argument in terms of hard security, linking the Jeju Naval Base to regional security balances and evoking the security dilemma (between China and the US-South Korea alliance). But by doing so, they paradoxically strengthen realist discursive structures.

Kenneth Waltz, the father of structural realism, once argued that the politics of peace may primarily lie in the internal and external politics of the powerful.Footnote 98 But as the clash over naval base construction on Jeju Island suggests, the politics of peace may take on a more ideational dimension. Different actors carry different assumptions about international politics. The security that policymakers seek to provide for society may not be the same peace and security that activists envision for their community. Differences may never be fully resolved, but productive dialogue can only begin by understanding how issues are framed and discussed by various actors and how these discourses extend from different worldviews and alternative assumptions about security.

Biographical information

Andrew I. Yeo is Associate Professor of Politics and Director of Asian Studies at The Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. He is the author of Activists, Alliances, and Anti-U.S. Base Protests (Cambridge University Press 2011), and co-editor of Living in an Age of Mistrust (Routledge, 2017) and North Korean Human Rights: Activists and Networks (Cambridge University Press, 2018). Other publications have appeared in International Studies Quarterly, European Journal of International Relations, Perspectives on Politics, Comparative Politics, and International Relations of the Asia-Pacific. He received his PhD in Government from Cornell University.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Association for Asian Studies Northeast Asia Council and the Catholic University of America Grant-in Aid programme, and institutional support from Korea University’s Asiatic Research Institute. In addition to three anonymous reviewers, I thank Sandra Fahy, Stephan Haggard, David Kang, John Lie, Gi-Wook Shin, Jiyoung Song, and Jae-Jung Suh for helpful feedback on earlier drafts. I also thank seminar participants at Cornell University, Stanford University, and the University of Southern California where earlier drafts were presented. Eunhou Song provided invaluable research assistance. Finally, I am grateful to the many activists who took time to share their views with me, and especially Paco Booyah and Sung-Hee Choi.