Introduction

References to human remains in wetlands often evoke images of the famous northern European bog bodies (Glob, Reference Glob1971; van der Sanden, Reference van der Sanden1996). With their finely preserved features (Figure 1), they arouse curiosity about who they were, how they lived, and why they ended up the apparent victims of violent death, deposited in bogs with intentionality and, in some cases, care. Even in the most objective observer, they elicit empathy and an emotional response unparalleled by most other forms of human remains encountered by archaeologists (see Giles, Reference Giles2009; Sanders, Reference Sanders2009; Giles & Williams, Reference Giles, Williams, Williams and Giles2016). Here, however, we posit that less emotively engaging human skeletal remains from wetlands raise equally pertinent questions about past ways of being, configurations of identity, and questions of value. By engaging with incomplete skeletal material, we seek to address questions relating to the assignment of personhood and its assumed residence in human bodies.

Figure 1. Tollund Man, one of the best-preserved Early Iron Age bog bodies (c. fourth century bc).

Images by permission of the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen.

The material comprises fragmentary skeletal deposits from wetlands in Norway (Sellevold, Reference Sellevold2011; Bukkemoen & Skare, Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018). The sample is small, restricted to just fifteen individuals from eleven contexts (see Table 1). Chronologically, the corpus belongs mostly to the Early Iron Age (500 bc to ad 500), coinciding with the heyday of bog body depositions across northern Europe. Our enquiry is thus conducted against this wider backdrop of presumed sacrificial deposits but, crucially, our sample is quite different from the near-complete faces of the past that ‘proper’ bog bodies present. We use this difference to examine the different responses such material tends to elicit, as a way of involving the skeletal remains in interpretations of how both collective and individual identity is configured, and to consider what human remains in sacrificial contexts reveal about underlying perceptions of value in relation to personhood.

Table 1. Sites mentioned in the text, by region. Dates are from the skeletal remains, calibrated.

We situate our research within a theoretical framework that sees personhood as relational, performative, and culturally relative (Butler, Reference Butler1990; Barad, Reference Barad2003; Brück, Reference Brück2004; Fowler, Reference Fowler2004). Though Eurocentric understandings of personhood are firmly anchored in the human body, the idea of a universal human personhood even in modern times unravels when we consider recent historical periods or the contemporary world around us. We need look no further than 1929, to the so-called ‘Persons Case’ in Canada, which established that women had the right to be appointed to its Senate, i.e. that they were people (Sharpe & McMahon, Reference Sharpe and McMahon2008), implying that there had previously been some doubt on the matter. Personhood and citizenship remain inextricably linked, defining access to resources and rights. Personhood retains relational aspects (Fowler, Reference Fowler2016), and is conditional, governed by complex rules of otherness and belonging.

Theories of Personhood

The use of anthropological understandings of personhood in archaeological interpretations is well-established (Brück, Reference Brück2004; Fowler, Reference Fowler2004, Reference Fowler2016; Jones, Reference Jones2005; Rebay-Salisbury et al., Reference Rebay-Salisbury, Sørensen and Hughes2010). Discussions of personhood have helped demonstrate how modern Eurocentric notions of ways of being have coloured our understanding of distant pasts (Jones, Reference Jones2005: 194). The application of concepts of dividual and partible persons has shed light on how being a person is dependent on more than just being an individual (Strathern, Reference Strathern1988; Fowler, Reference Fowler2004), and that personhood can be perceived, assigned, and experienced in differing ways.

Social identity is not fixed, but an ongoing process of production in both the emic and etic senses (Brück, Reference Brück2004: 311; Jones, Reference Jones2005: 216). This becoming is dependent on the cultural framework and historical circumstance within which it takes place. It also involves constantly evolving relationships with the surrounding environment, both material and social. Consequently, the performance (performance being taken here as a constant production and reproduction, following Butler, Reference Butler1990) of identity and personhood is a process that operates on many levels, from the individual to the collective.

Perceived and acknowledged divides between animals, objects, and humans are not universal and static but culturally determined (Fowler, Reference Fowler2004: 4, Reference Fowler2016; Ingold, Reference Ingold2006). Indeed, all classificatory ontologies are specific to the knowledge systems to which they belong and within which they are created and maintained (Todd, Reference Todd2016), giving grounds to question the rigidity of such divisions within past societies (Brück, Reference Brück2004). This can help explain how depositions of human remains need not always be the deposition of a person. By approaching the relationships between entities, such as human/object/landscape, we can address the underlying structures through which meaning is created and thus the world constituted (Barad, Reference Barad2003: 817). This becomes especially relevant when we consider that pre-Christian cosmologies in northern Europe were filled with notions of agency and aptitude applied to non-human entities (Price, Reference Price and Price2001, Reference Price2019; Andrén et al., Reference Andrén, Jennbert and Raudvere2006).

Here we propose that a relational approach to the construction and maintenance of personhood lifts the interpretative gaze past current notions and theoretical perspectives. We believe that envisaging different ways of being reflected in human skeletal remains can contribute to archaeological knowledge production. By engaging with a posthumanist, performative, and relational understanding of ways of becoming and being (Barad, Reference Barad2003), we acknowledge that personhood is in a constant state of flux rather than something inherent to and fixed within human bodies.

The relational construction of meaning through depositions opens up discussions of the fragmentary nature of the human remains in our study, which belong to wider webs of potential meaning within relative cultural structures. We shall attempt to understand them as ‘complete’ parts of complex assemblages of meaning, rather than approaching them as ‘partial’ human bodies.

Background: Sacrificial Interpretations

The Norwegian bog skeletons date primarily to the Pre-Roman to Roman Iron Age (eighth century bc to c. ad 400; Aldhouse-Green, Reference Aldhouse-Green2015: 8). Their chronological closeness and depositional similarities (human remains in wetlands) provide grounds for considering the Norwegian evidence in light of the wider wetland sacrifice tradition known across northern Europe. There is, however, considerable regional variation; as Ravn (Reference Ravn and Boye2011: 86) points out, the best-preserved bog bodies predominantly consist of complete bodies, unlike our incomplete skeletal remains. Though we postulate that the purposeful deposition of incomplete human remains demonstrates that something conceptually different may have taken place with regard to configurations of personhood and its relationship with human remains, we recognize that such ritual depositions in wetland sites invite and justify interpretative comparisons. The alignment of Norwegian bog skeletons with northern European bog bodies is further justified by the fact that the dominant mortuary practice at the time was cremation. Indeed, the bog skeletons are exceptional for being unburnt human remains in this period in Norway (Sellevold, Reference Sellevold2011: 81), which arguably indicates a ritual separate from normative burial practices.

In this context, we should also consider the occurrence of partial human remains found in some buildings in the northern European Iron Age. Though infrequent, examples of such remains placed in locations construed as particularly significant parts of buildings or settlements (e.g. thresholds, inside walls, under hearths, or in wells; Carlie, Reference Carlie2004; Eriksen, Reference Eriksen2017, Reference Eriksen2020) suggest that partial human remains could be potent offerings both on dryland and wetland sites. We suggest that the occurrence of human remains in settlement contexts establishes a precedent for interpreting fragmented human remains as votive (and even conceptually sacrificial) offerings.

The study of bog bodies has traditionally been influenced by Classical sources, such as Tacitus’ Germania, leaning towards interpretations of judicial punishment and ritual sacrifice (Ström, Reference Ström1942; Thorvildsen, Reference Thorvildsen1952; Glob, Reference Glob1971; van der Sanden, Reference van der Sanden1996; Nordström, Reference Nordström, Williams and Giles2016). There is not scope here to delve into whether Classical sources should be considered objective or truthful, but—setting aside the tendency to exoticize the Other and related political motivations (e.g. Fredengren, Reference Fredengren2015)—we note a persistent link between Germanic tribes and human sacrifice (see Aldhouse-Green, Reference Aldhouse-Green2015, with references). Some sources describe details that may be reflected in archaeological finds, including evidence of hanging and other forms of killing, deliberate submersion in water by weighing down with stones or sticks or wedging into place with stakes (see Glob, Reference Glob1971: 114; Aldhouse-Green, Reference Aldhouse-Green2015).

Given that deposits of fragmentary remains can be interpreted in a votive light, and that the ritual deposition of human remains in wetlands across time and space is a recurrent feature in our study area, we contend that our material can be set in the wider interpretatitive tradition pertaining to the bog bodies proper. While other interpretations are viable, we consider it justifiable to view many of the bog depositions as sacrificial offerings, in keeping with both the historical and current discourse on the subject (Thorvildsen, Reference Thorvildsen1952; Glob, Reference Glob1971: 218; van der Sanden, Reference van der Sanden1996; Nordström, Reference Nordström, Williams and Giles2016; Sitch, Reference Sitch2019; Giles, Reference Giles2020; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Christensen and Frei2020).

The Material

Just as the Norwegian human remains differ from fully fleshed bog bodies, so do the Norwegian wetlands differ from the Atlantic raised bogs in which the bog bodies are found (van der Sanden, Reference van der Sanden1996: 25; Strand et al., Reference Strand, Bjørkelo and Bardalen2019). Norwegian wetlands are numerous and often less threatened than those found in more densely populated regions. Moreover, the main threat they face is conversion into arable land, as opposed to peat cutting, as e.g. in Denmark and Ireland. We consider the data presented here to represent tentative regional manifestations, given that no other human remains (from intentional depositions) have so far been found, as could be reasonably expected had it been a widespread practice. Moreover, while inland Norway and the central/northern part of Norway contain a high proportion of wetland areas (Strand et al., Reference Strand, Bjørkelo and Bardalen2019), other regions, such as around the Oslofjord, have seen historical conversion of wetlands into arable land that yielded no human remains (Rebecca Cannell, pers. comm.).

The research history concerning Norwegian bog skeletons is brief, although recent work on the topic raised its profile (Lillehammer, Reference Lillehammer, Lally and Moore2011; Eriksen, Reference Eriksen2017; Bukkemoen & Skare, Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018). In the mid-twentieth century, Dieck (Reference Dieck1969) published a list of twelve finds, which on closer examination in the 1990s was reduced to four, as many of Dieck's inclusions could not be traced (Sellevold, Reference Sellevold2011). A subsequent re-examination of the existing material and the addition of new finds resulted in an updated list by Berit Sellevold (Reference Sellevold2011: 80), comprising fifteen bodies from nine locations. The material discussed here differs slightly in that it includes the discovery of two more individuals from inland Norway (Bukkemoen & Skare, Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018). It excludes those not attributable to intentional wetland deposition, namely two bodies buried in dry ground that subsequently turned wet (Skjoldehamn and Hamarøy) and an insufficiently documented body from Håland (Sellevold, Reference Sellevold2011: 82).

Our data are presented in regional groupings, listing information about the landscape context at the time of deposition where known, the date and nature of the depositions (fragmented remains, articulated or not) and associated finds. We draw inspiration from Chapman and colleagues’ (Reference Chapman, van Beek, Gearey, Jennings, Smith, Nielsen and Elabdin2020) framework for a scalar interpretation of bog bodies that proposes a best practice structure, where the micro-scale includes the precise context of the body and its deposition, the meso-scale widens to the wetland context and the macro-scale includes longer-term considerations and landscape archaeology. We consider the micro- and meso-scales as far as is known and where relevant to our analysis in the regional sections. The macro-scale comes into play in our interpretation of ritual behaviour in the discussion.

Inland: A Very Local Tradition

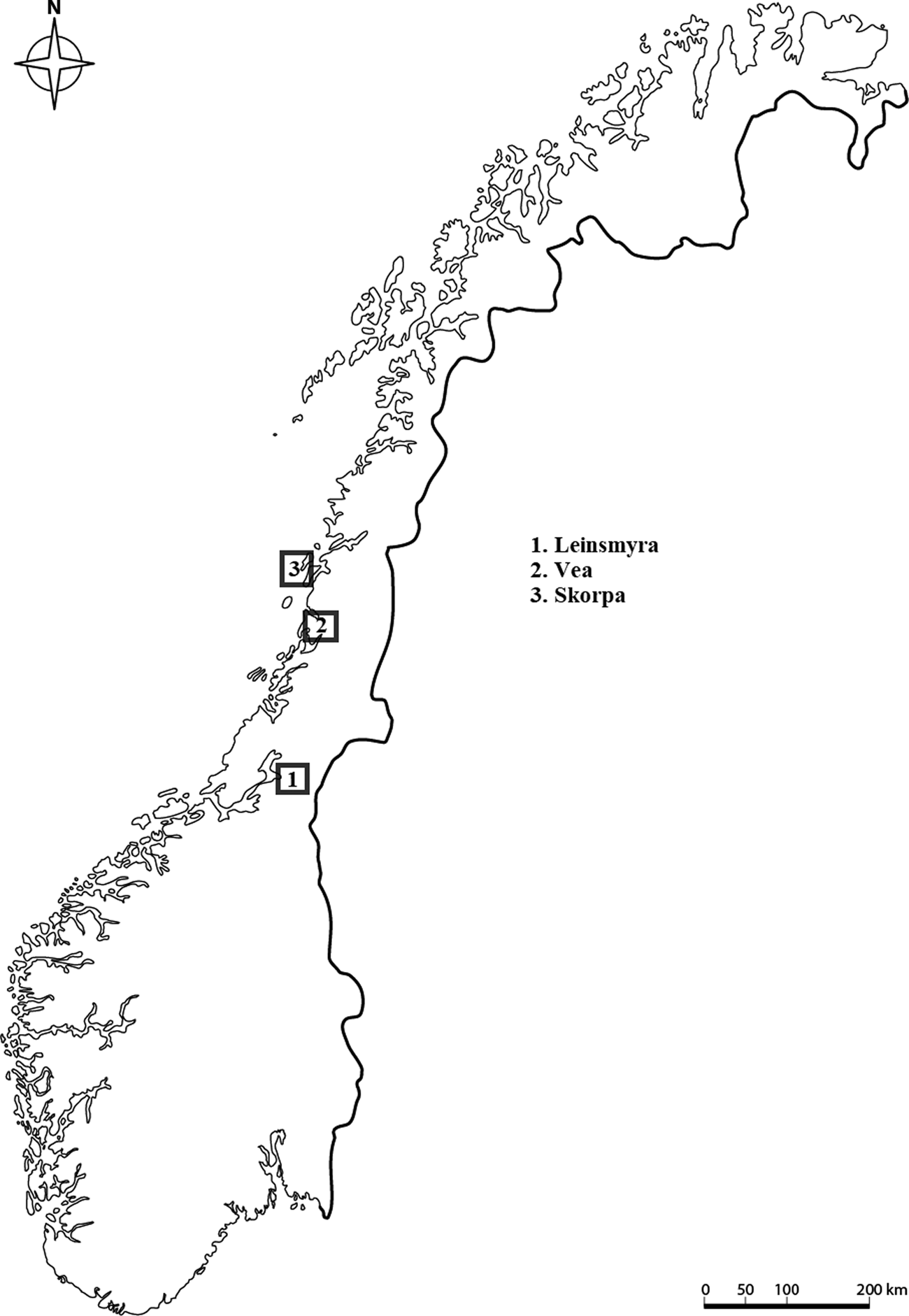

The largest concentration of human remains from wetlands in Norway comes from a small area in inland Norway (Figure 2), with the remains of seven individuals, mostly dating to the Pre-Roman Iron Age (500–0 bc) (Bukkemoen & Skare, Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018).

Figure 2. Map of the inland sites.

The material shares several traits, including deposition in open water that subsequently turned marshy, as indicated by pollen analysis; all the remains appear to be fragmentary; several were found with twigs and small stones. At least one site (Starene) shows repeated ritual use over time, though with a change from depositions of human remains to those of animal remains (Bukkemoen & Skare, Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018: 8–10).

As shown in Table 1, there is no clear pattern in the deposited body parts: the deposition from Starene (Figures 3 and 4) consists of only femora, while Ry and Kinnlitjernet have most, though not all, skeletal parts present. This appears to have been a deliberate and repeated trait. For instance, at Ry most of the body was present but disarticulated. As it was placed in stagnant water at the time of deposition and was held in place by branches, tree trunks, and stones, it seems likely that the remains were deliberately placed in disorder, rather than disturbed by taphonomic processes (Bukkemoen & Skare, Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018: 10). At Kinnlitjernet, the remains were most probably deposited in anatomical disorder as well (Bukkemoen & Skare, Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018: 12). Bukkemoen and Skare (Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018: 12) have reasoned that the occurrence of disarticulated human remains which do not exhibit signs of deliberate fragmentation and at sites that do not show evidence of post-depositional disturbance can be interpreted as a regional practice of depositing selected (potentially defleshed) body parts.

Figure 3. One of the femora from Starene in situ.

Photograph by Grethe Bjørkan Bukkemoen (KHM CC BY-SA. 4.0).

Figure 4. View of the site at Starene (centre of the image).

Photograph by Grethe Bjørkan Bukkemoen (KHM CC BY-SA 4).

The cause of death was unclear in all cases, and there are no certain indications of violence, though one adult male (from Lange Re) had a broken collarbone that had healed prior to death (Sellevold, Reference Sellevold2011: 72, 80). The remains are all of adults and they are all unburnt at a time when cremation was the norm (Sellevold, Reference Sellevold2011: 81). We deduce the existence of a coherent tradition of depositional offerings, with intentionality and citations between the deposits hinting at ritualized invariance and repetition (Bell, Reference Bell1997).

Rogaland: The Children at Bø

Our second grouping consists of a single site at Bø, in Rogaland on the south-west coast of Norway. Here, the cranial fragments of four infants were discovered in a sunken bog, which had been open water at the time of deposition (Lillehammer, Reference Lillehammer, Lally and Moore2011; Sellevold, Reference Sellevold2011). It cannot be ascertained whether or not the skulls were deposited intact before the flesh disintegrated (Lillehammer, Reference Lillehammer, Lally and Moore2011: 48). Their position (at a depth of approximately 1 m, with 30 cm between the fragments) suggests a single depositional event (Lillehammer, Reference Lillehammer, Lally and Moore2011: 50; Eriksen, Reference Eriksen2017). No other body parts were found; selective deposition is likely, though it is possible that unequal preservation is a factor. The cause of death remains undetermined (Lillehammer, Reference Lillehammer, Lally and Moore2011).

The deposition of very young children in wetlands was, judging from the known corpus of bog bodies, relatively rare (but see Monikander, Reference Monikander2010: 79–91; Lillehammer, Reference Lillehammer, Lally and Moore2011; Eriksen, Reference Eriksen2017: 343). Several of the more famous bog bodies were in their teens at the time of death; while they are called ‘children’ by some scholars (van der Sanden, Reference van der Sanden1996: 82), it is arguably appropriate to term them young adults when considering the times in which they lived (Lillehammer, Reference Lillehammer1989; Ariès, Reference Ariès1996). The Bø crania stand out therefore, both within the context of the Norwegian material and that of the northern European bog bodies.

Central/Northern Norway: Hints of a Regional Tradition

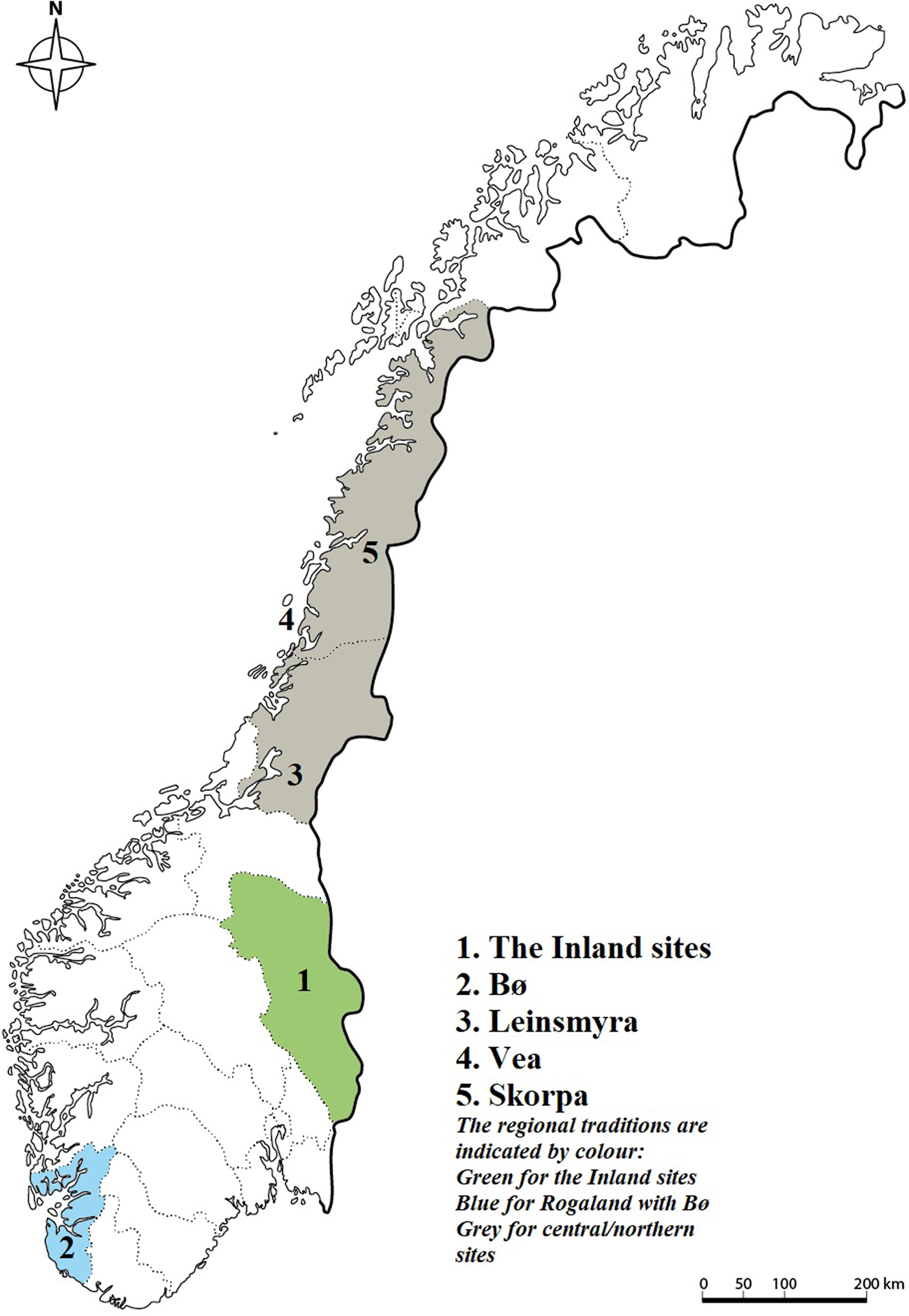

The third grouping includes sites in central/northern Norway (Figure 5) that yielded the skeletal parts of four relatively young adults between 15–30 years old (Henriksen & Sylvester, Reference Henriksen, Sylvester, Barber, Crone, Henderson, Sands, Clark and Hale2007: 344), all dating to the first five centuries ad. Three finds are of crania only (Henriksen, Reference Henriksen2014).

Figure 5. Map of the central/northern sites.

Leinsmyra yielded two skulls, found roughly 20–30 cm apart at a depth of 2–3 m. Their dates are respectively ad 265–410 and ad 450–550, suggesting that, despite their proximity, they may represent separate depositional events (Henriksen & Solem, Reference Henriksen and Solem2005; Henriksen & Sylvester, Reference Henriksen, Sylvester, Barber, Crone, Henderson, Sands, Clark and Hale2007); alternatively, they may indicate the curation of one of the skulls. No other remains were found in the area despite archaeological excavation at the time of discovery (Henriksen & Sylvester, Reference Henriksen, Sylvester, Barber, Crone, Henderson, Sands, Clark and Hale2007: 344). It is therefore not unlikely that the crania were deliberately deposited as skulls and not as parts of articulated bodies. The Leinsmyra skulls also appear to have been deposited in water that subsequently turned marshy (Henriksen & Sylvester, Reference Henriksen, Sylvester, Barber, Crone, Henderson, Sands, Clark and Hale2007).

Another skull, dating to between 30 bc and ad 115, was discovered at Vea, Nærøy (T19287; Henriksen, Reference Henriksen2014) (Figure 6). Its condition when discovered (with one side crushed) suggests that it may have been defleshed before deposition (Gaustad, Reference Gaustad1972). No other remains were found, leading to the supposition that only the skull was deposited. As at Leinsmyra, this skull also appears to have been deposited in open water (Gaustad, Reference Gaustad1972). A more complete skeleton was found at Skorpa in Nordland, dated to ad 415–495, and also aged between fifteen and thirty years (T16416b; Henriksen, Reference Henriksen2014). This find included several small stones, and was considerably disordered at the time of discovery, though documentation is sparse (Norwegian University of Science and Technology archives, 1946).

Figure 6. The skull from Vea.

Photograph by Ole Bjørn Pedersen, NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet (CC BY-SA 4.0).

As Henriksen (Reference Henriksen2014: 22) has pointed out, the occurrence of four individuals, all interpreted as female (although sex determination based on cranial morphology is far from secure), all of a similar age, and all dated to within a few centuries of each other with potential overlap in three cases, can be taken to represent a coherent regional phenomenon.

Summary of the Data

Each regional group (Figure 7) contains fragmented or incomplete remains, interpreted as attributable to depositional practices rather than taphonomic processes (Henriksen & Solem, Reference Henriksen and Solem2005; Bukkemoen & Skare, Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018). Nearly all skeletal remains were deposited in open water, which turned marshy over time. None of the bodies had traces of fatal violence (though healed injuries and post-mortem damage were observed). The time between death and deposition cannot be ascertained in any of the cases. In some instances, this must have been considerable (long enough for soft tissue to decompose and selected bones to be deposited). As cremation was the dominant burial custom throughout the period, it is possible that the deposition of unburnt bones did not form part of ordinary funerary practices, justifying interpretations within a ritually charged framework. Considering our sample from a relational perspective of personhood, we contend that even though these skeletal materials may represent ‘sacrificed’ human remains, this does not necessarily make them human sacrifices in the modern meaning of the term with its embedded assumptions of personhood and social recognition.

Figure 7. Overview of regions and sites.

Discussion

Recent research on bog bodies has offered new insights by shifting its focus beyond the ideologies and actions that led to their deposition, and instead examines the reactions that these bodies produce among scholars and the public (Giles, Reference Giles2009; Sanders, Reference Sanders2009). By working from a conceptual platform that construes the bodies as introspective devices, we may grasp why they cause such strong emotional responses today, explore ideas of personhood, apprehend how modern audiences engage with certain past materials over others (Giles & Williams, Reference Giles, Williams, Williams and Giles2016), and better understand how this shapes our ideas of past ritual behaviours. A complete bog body, to a present-day observer, represents a person from the past, but in the context of conditional or relational personhood this is not so simple.

For much of prehistory, notions of personhood are likely to have been deeply contextual. Thus, we need to first query whether or not a human body should be considered a person or whether conditional access to personhood makes this culturally variable. For instance, Fredengren's (Reference Fredengren2018) examination of networks of care and neglect in Swedish bog depositions highlighted the fundamental issue of assuming that human remains necessarily signify a sacrificed ‘person’. She argues that the victims’ identities were constructed through their status as differentiated, as ‘others’ intended to be killed. As far as is currently known, the Norwegian data do not show overt evidence of exclusionary lives, but this does not mean that such tactics were not employed. Not all forms of discriminatory ‘othering’ leave skeletal traces, and the question of whether the Norwegian remains should be viewed as ‘people’ in a culturally relative sense remains unanswered. These topics are intimately entangled with how we envisage and configure personhood, and how we project it onto the past.

Personhood, in the modern conception, is embodied, in the sense that embodiment encapsulates the ‘perceptual experience and mode of presence and engagement in the world’ (Csordas, Reference Csordas and Csordas1994: 11). Encountering a preserved body from the past is a powerful experience: it generates feelings of connectedness, not only in the general public but also in the scholars who study them (Giles, Reference Giles2009; Sanders, Reference Sanders2009). Such a link with a distant past is, we argue, ultimately founded on current notions of the body as the chalice of personhood (Brück, Reference Brück2004; Fowler, Reference Fowler2004; Jones, Reference Jones2005). Thus, better-preserved human remains tend to engage our notions of personhood more than bare bones. A face allows us to engage with the humanity of the past in ways that are generally unfathomable in archaeology (e.g. Sanders, Reference Sanders2009; Joy, Reference Joy, Fletcher, Antoine and Hill2014; Giles, Reference Giles2020), even among the best-preserved material (Giles & Williams, Reference Giles, Williams, Williams and Giles2016: 5). And yet, this intimacy is an illusion perpetuated by soft tissue. While highly valuable both scientifically and culturally, soft tissue is no more a direct link with the past than disarticulated bones. Nonetheless, prehistoric skin gets under our skin. This projection of personhood by the living onto the dead lies entirely in the eye of the beholder, and it can be argued that ascribing personhood to dead faces, but not to dead bones, is deeply ethnocentric.

Modern understandings of personhood are a post-enlightenment affair, based on notions of human separateness, boundedness, and individuality (Brück, Reference Brück2004). They do not easily apply to other ways of viewing the world, in which agency and intentionality may not be restricted to human entities, nor personhood contained in a bounded vessel. It is this idea of bounded and indivisible personhood residing in the human body that we question, positing instead that an understanding of personhood as relational (Barad, Reference Barad2003; Brück, Reference Brück2004) can provide a useful tool for engaging with ‘bodiless’ bones. Using Butler's (Reference Butler1990) definition of identity as constantly performed and produced, along with Barad's (Reference Barad2003) concept of relational ontologies, we can explore different configurations of the self, the Other, and personhood as a socially structuring concept created as much in the spaces and relations between beings, objects, and the spiritual world as within them. In this sense, we approach the fragmented Norwegian evidence as symbolic of perceptions of personhood that were not anchored in bounded human flesh but determined by contexts and relations. Fragmented skeletal remains may symbolize much the same as a complete human body if we allow for a nuanced view of where identity resides. The very choice of words here is revealing: we consider skeletal remains incomplete or fragmentary when not representing our ideas of a complete human body, and yet their incompleteness may have a material significance that ‘whole’ bodies do not (Koslicki, Reference Koslicki2008; for archaeological investigations of the possible significances of purposely fragmentary assemblages see, e.g., Chapman, Reference Chapman2000; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Gaydarska, Raduncheva and Koleva2007; Frieman, Reference Frieman2012). They may have been seen as complete or otherwise proper to the task at hand in and of themselves. Bearing in mind that ideas of where personhood resides are profoundly culturally contingent, as are ideas of what the body itself constitutes (Robb & Harris, Reference Robb and Harris2015; McClelland & Cerezo-Román, Reference McClelland, Cerezo-Román, Williams and Giles2016: 41), we place the remains discussed here in a context where personhood need not require a complete body (Fowler, Reference Fowler, Tarlow, Hamilakis and Pluciennik2002, Reference Fowler2004, Reference Fowler, Tarlow and Nilsson Stutz2013; Williams, Reference Williams2006; Rebay-Salisbury et al., Reference Rebay-Salisbury, Sørensen and Hughes2010).

Selective burial involving partial bodies is known from various periods in European prehistory, in diverse societies from the Neolithic to the early Middle Ages (Brück, Reference Brück2004; Jones, Reference Jones2005; Williams, Reference Williams2006: 86). These indicate that the belief in the body as indivisible is not universal. Indeed, it was the custom to inter only parts of cremations during the Norwegian Iron Age rather than the complete remains of the cremated body (Holck, Reference Holck1996). This also corresponds with wetland sites containing partial bodies found in Sweden (Monikander, Reference Monikander2010; Fredengren, Reference Fredengren2018). Certainly, the ‘completeness’ of bodies does not always appear to have been important to depositional and burial logics.

Offerings in Fragments as Symbolic Wholes

Partial skeletal remains can be viewed in light of a cosmology that conceives personhood as less individualistic and more dependent on collective actions and relations in and between what constitutes the known world. The deposition of bodies and body parts in wetland landscapes may be seen as a substantiation of the sacred condition of both the human (and animal, and material) object and the place itself, including the entanglements between them. Within an eschatological framework, the act of ritually depositing any kind or number of components into a sacred space could have symbolically charged not just the landscape but the whole of human experience with agential potential, and mnemonic significance (Semple & Brookes, Reference Semple and Brookes2020).

Within the context of northern European bog body depositions, a significant difference exists between the deposition of whole bodies and that of body parts. Many of the well-preserved bog bodies come from contexts with little or no objects or remains around them. By contrast, single elements or fragments of human skeletons in bogs often belong to assemblages reflecting a greater variety of sacrificial offerings, such as animal remains and natural and worked objects (Becker, Reference Becker1972; Karsten, Reference Karsten1994; Lund, Reference Lund2002). From a mereological perspective (mereology being the study of parts and the whole they form), the parts may, in prehistoric cosmological contexts, have been considered equal to or even more valuable than the whole body after death (Koslicki, Reference Koslicki2008). In our relational perspective, the parts themselves become agents in, and co-creators of, meaning. Used in performative and ceremonial contexts, their perceived value may not necessarily have reflected the value of the individual from whom the parts derived. It is possible that they were the end point of rituals which took place elsewhere and perhaps even some considerable time before final deposition.

Alternatively, the partial human remains may reflect a rite in which they acted as a replacement or substitute for an actual ritual killing. This is especially applicable when we consider sacrificial offerings as communal and collectively invested acts, demanding symbolic or actual offerings and collective contributions to such performances. Thus, it is plausible that bones may be the remnants of collective acts, represented by fragmented but no less ‘living’ remains, conceived as more than just objects. They may have been carriers of individual (deceased) identities, e.g. within an ancestor cult, or expressions of collective identities at group level, a form of collective sacrifice where the fragments belong to everyone.

With respect to mereology (see Koslicki, Reference Koslicki2008: 125–26), if we consider a body or whole skeleton as a kind of structured whole, parts of which may be rearranged but still maintain their essence or identity (Koslicki, Reference Koslicki2008: 179), when that whole comes apart through decomposition or dismemberment, the assemblage of those parts could become the focus of perceived personhood, identity, or value replacing the previous whole. The location and proximity of the elements within an assemblage take on new meaning, as does their use in ritual. As Bell (Reference Bell1997: 75) observes, ‘the dramatic or performative dimensions of social action as affording a public reflexivity or mirroring that enables the community to stand back and reflect upon their actions and identity’, ritual depositions in watery places would constitute both physical and metaphorical reflections. Indeed, for much of human existence, smooth water surfaces were the only places where one could actually look into one's own face.

Portions or fragments of bodies inserted into these reflective spaces may have been understood to represent entire kin groups or communities, because they were disarticulated and removed from normative funerary rites, having returned through disarticulation to the collective identity, which transcended notions of individual ways of being. The watery locations and the remains placed in them could impose the kind of ‘ontological entanglements’ between observer and observed, as suggested by Barad (Reference Barad2007: 333). Thus, the wetland as sacred landscape might invoke in the Iron Age observer a sense of communication and exchange with the transempirical, made stronger through the investment of material remains.

Offerings in Relation to Their Context

We propose that meaning was not created simply by the presence of human remains, but rather by the relations between them and their wider contexts. The children deposited at Bø provide an example. Their identities were probably defined not only by their relationship to the individual(s) who placed them in the bog, as well as to each other, but also by their depositional contexts and the landscape. It is worth considering that children as social beings have been understood differently in various societies and times, often not considered ‘full’ people until well past infancy (Mundal, Reference Mundal1987; Ariès, Reference Ariès1996; Eriksen, Reference Eriksen2017). Considering high mortality rates, the prevalence of infanticide as a pragmatic act in times of stress or perceived necessity (Scheper-Hughes, Reference Scheper-Hughes1993; Scott, Reference Scott, Arnold and Wicker2001; Wicker, Reference Wicker2012; Eriksen, Reference Eriksen2017), and more broadly that not all humans were born equal (Mundal, Reference Mundal1987), it may be useful to distance ourselves from current modes of thinking about personhood being assigned a priori to all human lives. Lillehammer (Reference Lillehammer, Lally and Moore2011: 55) has fielded the idea that if very young children had lower social value, the sacrifice of a new-born may have been a way of cheating the gods (see also Willerslev, Reference Willerslev2013). By offering something technically proper (a human life) but of lower social value (a child), the necessary exchange could have been made without undue social stress.

The children may of course have died of natural causes. Whatever the reason behind the deposition, we can surmise that the site served as a powerful mnemonic space in the sacred landscape. Regardless, whether the scenario leading up to the deposition was an act of sacrifice, an infanticide, or the result of natural causes, the placement of the children's skulls in the bog and their close arrangement is key to the ritual significance of the act itself. We argue they draw their meaning and their agency from the relations between each other, the water in which they were placed, the (ritual) act which placed them there, the actions of those who deposited the skulls, as well as the wider landscape. These represent a series of bounded and entangled circumstances and conditions which situate them in the world (see Barad, Reference Barad2007: 171).

Such a view can in turn be applied to the other regional manifestations. Once offered, the remains may have taken on relational meanings strengthened by their place both in the ritual landscape and the system of beliefs. If they were sacrificial in nature, their importance in the landscape suggests they formed part of a wider network of meaning, of a complex mesh of acts, agents, and relations.

The landscape itself and the choice of wetlands for the depositions of such offerings is also meaningful; the bogs themselves are not a uniform entity, they are also subject to change. The Norwegian skeletal material was typically deposited in open water which turned into bogs over time, underscoring the shifting nature of wetlands (Chapman, Reference Chapman2015). They are often described as liminal spaces amenable to communion with the gods (van der Sanden, Reference van der Sanden1996: 134), though we cannot know if such a view was universally held (Farley et al., Reference Farley, Giles and Fredengren2019). We may imagine that their transitional and liminal nature (see Monikander, Reference Monikander2010: 93) set these features of the landscape apart and set them up for ritual activity. While we contend that there was a perceived link between wetlands and votive offerings, we acknowledge that there may be an evidential bias caused by preservation by water and wetlands and by infrequent human disturbance over time.

Sites were often reused. At Starene, two distinct phases were identified by Bukkemoen and Skare (Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018): human deposits in the Pre-Roman Iron Age (500–0 bc) and animal deposits during the Migration and Merovingian periods (ad 400–740). Bukkemoen and Skare (Reference Bukkemoen and Skare2018: 2) urge scholars to turn away from anthropocentric notions of human primacy in their interpretations and highlight how a detailed knowledge of find contexts can expand our understanding of a site's multigenerational lifespan. Understanding what constituted appropriate offerings at different times can thus help contextualize acts of sacrifice and deposition. It is possible that the remains created significance that was remembered for a considerable time, upholding the ritual significance of a particular body of water across generations. For example, the range of dates for the Leinsmyra skulls may fit within a pattern of reuse and repeated ritual behaviour (Henriksen & Sylvester, Reference Henriksen, Sylvester, Barber, Crone, Henderson, Sands, Clark and Hale2007). We attribute such a manifestation to the interplay of objects, acts, and landscapes, creating lasting relational ontologies.

Conclusions

While the Norwegian bog skeletons may not have the same instant pull as the better-preserved bog bodies, they raise just as many questions. As sacrificial offerings they reflect an entanglement of lives, values, personhood, relationships, and cultural contexts, which together create(d) their meaning. Crucially, their personhood and value may have been influenced by factors present both in life and death, generated and maintained by complex interactions and relations, perpetuating a web of meaning which cannot be simply reduced to, or contained in, human bodies.

In a sacrificial tradition, we need to consider restrictions of access to personhood and its implicit agency in tandem with what personhood entails within a given society. Some human lives as offerings were likely to have been more or less valuable than others, depending on a range of considerations concerning the victims, their relationship to their sacrificer(s), the explicit and underlying reason(s) for the ritual undertaking, and its intention(s). These factors are not mutually exclusive, but dynamic and inclusive, depending on the contexts of the events. In short, we need to consider how human remains relate to personhood in a context that is wider than that requiring a ‘complete’ human body.

Our relational approach places bog skeletons and disarticulated remains in a framework that explores understandings of past personhood as not limited to, nor necessarily contained in, the human body, and not intrinsically understood even across time in a regional context. We posit that modern notions of embodied personhood are unlikely to be directly applicable to the distant past, especially when we contrast how modern audiences relate to the past through imagined ‘persons’ in the form of whole bog bodies as opposed to mere bones. Potentially the latter had the same or parallel ritual meaning for those who deposited them. Seeking answers in relations may hold the key to better understanding the varied logics at play in the ritual deposition of humans and parts of humans in wetlands in the past.

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken as part of the project Human Sacrifice and Value, funded by the Norwegian Research Council (PI Rane Willerslev; FRIPRO HUMSAM, project 275947). We are grateful to Lasse Sørensen and Susanne Klingenberg with the National Museum of Denmark for access and permission to use the original archive photos of Tollund Man. The authors also wish to thank Merete Moe Henriksen for generously sharing her research and archival documents on the bog skeletons from central and northern Norway. Grateful thanks are also extended to Grethe Bjørkan Bukkemoen for sharing thoughts, images, and research on the subject, and to Sean O'Neill and Svein Harald Gullbekk for insightful discussions about the nature of sacrifice. The authors are grateful to four anonymous peer reviewers for their invaluable feedback and comments.