Introduction

The Iron Age was a male world, or if not, research has understood it as such. Since its inception, Iron Age archaeology has often prioritized patriarchal narratives, mostly built on accounts of coercion rather than cohesion practices (see Pope, Reference Pope2021). Warlike events, weapons, trade, and authority have been at the heart of the investigation, neglecting reproductive, educational, and caring practices, more often associated with women. This approach to the past has a two-fold origin. On the one hand, men mainly directed nineteenth- and early twentieth-century archaeological enquiries. They were often well-off and had served compulsory military service and/or participated in wars, such as the World Wars, the Spanish Civil War, or the colonial wars, resulting in a strong interest in weapons and warfare. Moreover, the progressive modernization of the countries, which went hand-in-hand with industrialization and the abandonment of rural areas, encouraged a focus on urban planning and the technological innovations that iron brought. On the other hand, archaeologists have primarily conceptualized gender as binary and divided into rigid gender roles, assigning to men qualities such as agency, strength, or leadership, while understanding women as passive, weak, and dependant. Furthermore, researchers applied the nineteenth and twentieth centuries’ sexual division of Western culture to past societies, which gave rise to binary stereotypes that gave prominence to activities understood as male as being vital contributions to society and history (e.g. tool making, hunting, trade, or warfare), ignoring the activities traditionally assigned to women (e.g. parenting, gathering and processing food) (Nelson, Reference Nelson1997: 13–21, 88; Meyers, Reference Meyers, Dever and Gitin2003; Brumfiel & Robin, Reference Brumfiel and Robin2008; Levy, Reference Levy, Ray and Fernández-Götz2019). As a consequence of these discourses, women have been practically invisible in most archaeological narratives and their activities have frequently been an afterthought.

Over the last four decades, gender and feminist archaeologies have criticized the excessive androcentrism of traditional interpretations and offered alternative methodologies that address gender-based inequalities and contribute to filling the gender data gap (Conkey & Spector, Reference Conkey and Spector1984; Nelson, Reference Nelson1997, Reference Nelson2007; Sørensen, Reference Sørensen2000; Arnold & Wicker, Reference Arnold and Wicker2001; Sánchez-Romero, Reference Sánchez-Romero2005; Delgado & Picazo, Reference Delgado and Picazo2016; Muñoz & Moral, Reference Muñoz and Moral2020). Some scholars have proposed that we should not only make women more visible in the archaeological record but also raise awareness on how crucial their activities were for shaping past societies. Some of the main feminine activities have been related to nurturing, maintaining, and reinforcing those ideologies and mechanisms that contribute to society's production and reproduction (Hernando, Reference Hernando2005, Reference Hernando2012; Montón-Subías, Reference Montón-Subías and Sánchez-Romero2005; Sánchez-Romero, Reference Sánchez-Romero2005). To approach this, it has been necessary to create complex, flexible concepts, such as ‘maintenance activities’ that encompass tasks associated with repetition and recurrence, not change (Hernando, Reference Hernando2005: 125–26). These activities do not require moving to unknown places and are linked to the preservation and perpetuation of bonds and group cohesion. Sandra Montón-Subías (Reference Montón-Subías2000: 52–53) noted that these activities were mostly related to food processing, pregnancy, parenting, care, hygiene, or public health. Although not all need be carried out exclusively by women, in historic times they largely were. In addition to maintenance activities, women were also involved in production (e.g. agriculture, textiles, pottery, etc.). Most archaeological research has (erroneously) assumed that women's activities and production were unspecialized, thereby pushing them into the background of investigations, despite their contributions influencing the economic, social, and symbolic status of households and families.

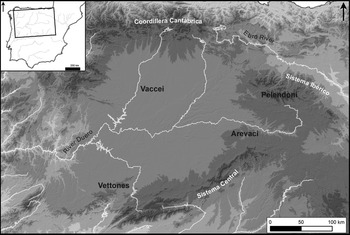

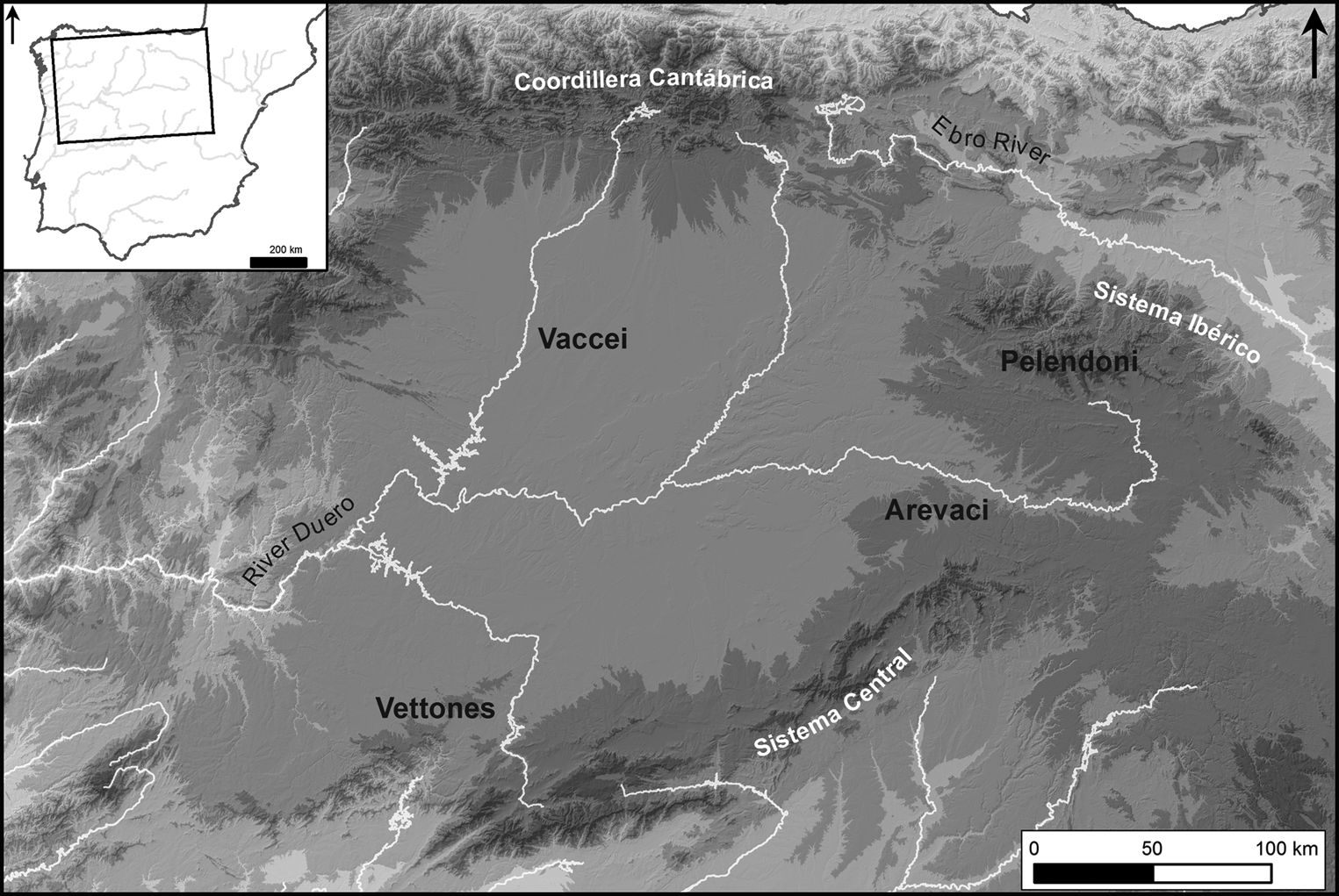

This article focuses on the northern Meseta in central Spain (Figure 1), a region with a long Iron Age research tradition, but for which knowledge about women is so far poor and limited to general overviews of gender mostly in funerary contexts (Prados-Torreira, Reference Prados-Torreira2011–2012; Baquedano & Arlegui, Reference Baquedano, Arlegui, Torija and Baquedano2020; Liceras-Garrido, Reference Liceras-Garrido2021) and some publications that merely present grave goods in female burials (Sanz-Mínguez & Diezhandino, Reference Sanz-Mínguez, Diezhandino, Sanz-Mínguez and Romero2007; Sanz-Mínguez & Romero, Reference Sanz-Mínguez, Romero and Burillo2010; Sanz-Mínguez, Reference Sanz-Mínguez, Sánchez-Romero, Alarcón and Aranda2015; Sanz-Mínguez & Coria, Reference Sanz-Mínguez, Coria, Sanz-Mínguez and Blanco2018). In none of these publications is the role of women in society as social agents posited, nor is it considered whether their agency influenced, transformed, or shaped past communities. The possible existence of alternative gender identities to the man-woman dichotomy has not been questioned either. Here, my aim is to revisit the traditional archaeological and textual evidence for the Late Iron Age Meseta, bringing hidden and overlooked data about women to the forefront.

Figure 1. The northern Meseta in the Late Iron Age, with main ethnic groups names.

An Overview of Oppida in the Northern Meseta

Archaeological evidence

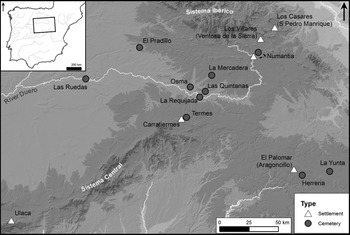

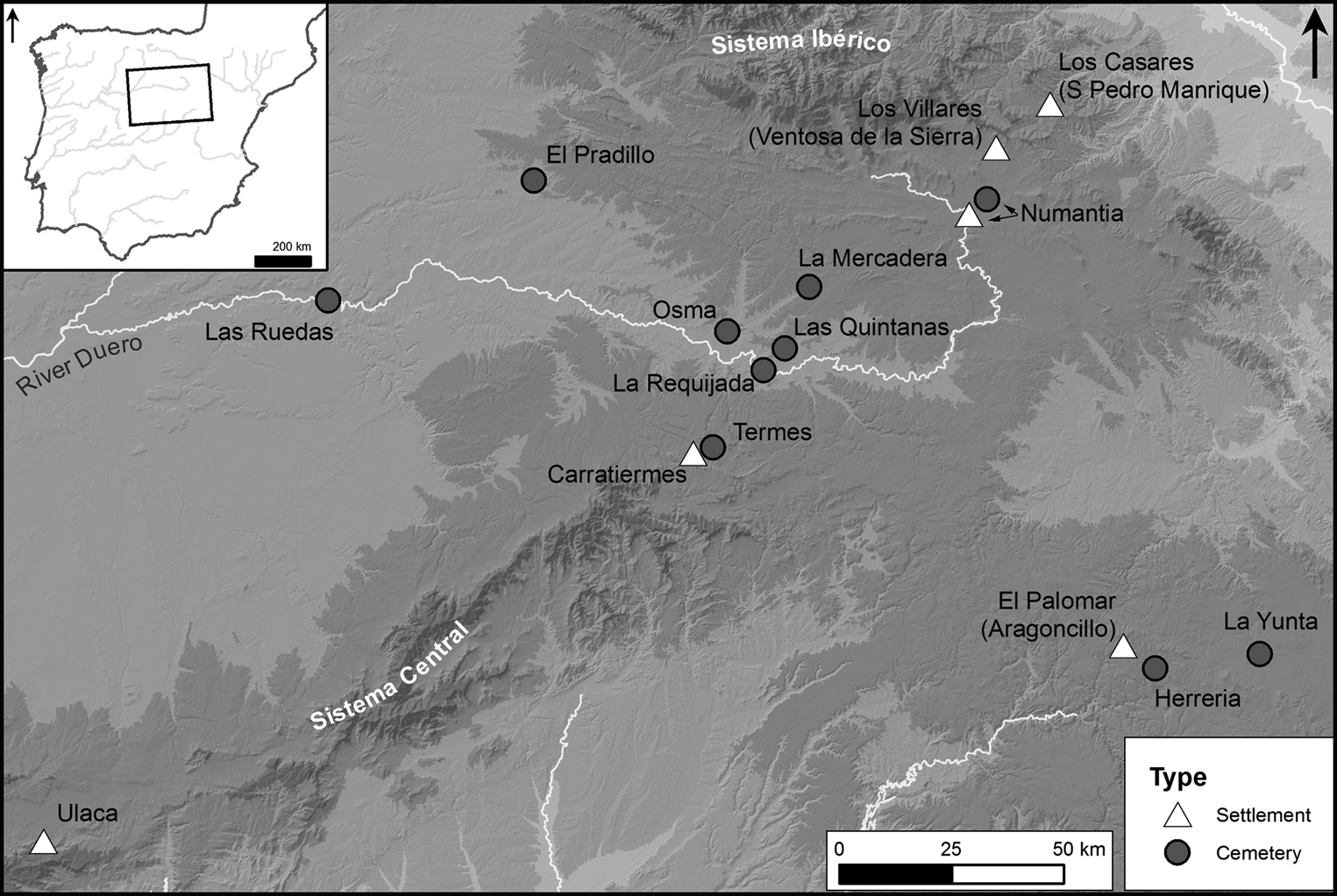

The Late Iron Age in the Meseta covers a period spanning the fourth to the second centuries bc, which saw the urbanization of the region up to the Roman conquest (Figure 2). This period is largely defined by a pattern of landscape occupation characterized by oppida, small urban centres that controlled extensive territories populated by farms, defensive forts, and secondary settlements (Liceras-Garrido, Reference Liceras-Garrido, Honrado, Brezmes, Tejeiro and Rodríguez2014; Liceras-Garrido & Quintero, Reference Liceras-Garrido, Quintero and Jimeno2017). Depending on their size, the settlements’ interiors tend to contain houses grouped into blocks, often attached to fortifications, with walking spaces and courtyards between them rather than actual streets (Arenas-Esteban, Reference Arenas-Esteban and Belarte-Franco2009; Jimeno, Reference Arenas-Esteban and Belarte-Franco2009; Ruiz-Zapatero, Reference Ruiz-Zapatero and Belarte-Franco2009; Jimeno et al., Reference Jimeno, Liceras-Garrido, Quintero, Chain, Sastre, Rodríguez-Monterrubio and Fuentes2018). In a few instances, central spaces have been identified, seemingly related to worship activities, such as the sanctuary of Ulaca (Álvarez-Sanchís, Reference Álvarez-Sanchís2011: 154) or the temple of Termes (Almagro-Gorbea & Lorrio, Reference Almagro-Gorbea and Lorrio2011: 123–206).

Figure 2. Northern Meseta Iron Age sites mentioned in the text.

Houses were rectangular, generally built on stone foundations, rammed-earth walls, and thatched roofs. Although there is a strong regional variability, domestic spaces were arranged in a simple, linear manner and were often divided into three rooms (Arenas-Esteban, Reference Arenas-Esteban and Belarte-Franco2009; Jimeno, Reference Arenas-Esteban and Belarte-Franco2009; Ruiz-Zapatero, Reference Ruiz-Zapatero and Belarte-Franco2009). Indoors, kitchen, storage, and tableware ceramics are usually the main material recovered, accompanied by artefacts related to domestic production such as querns, looms, or spindles whorls, which are also frequently found in house entrances and courtyards (Märtens et al., Reference Märtens, Contreras, Ruiz-Zapatero and Baquedano2014).

Cremation was the normal burial rite (Cerdeño & García-Huerta, Reference Cerdeño, García-Huerta, García Huerta and Morales2001; Lorrio, Reference Lorrio2005), with cemeteries containing a large number of graves grouped in clusters that correspond to family units (Liceras-Garrido, Reference Liceras-Garrido2022). Once again, regional variability is obvious, particularly in the shape of the burials, the stelae marking the graves, the quantity of burnt human remains deposited, the grave goods, and the treatment of these grave goods in funerary rituals. Burials are often simple pits in which the deceased and the grave goods were deposited. Pottery and weapons were the two most common grave goods, their types and combinations depending entirely on the cemetery and its community. While in the cemeteries of Numantia or Carratiermes (location on Figure 2; Argente et al., Reference Argente, Díaz and Bescós2001; Jimeno et al., Reference Jimeno, De La Torre, Berzosa and Martínez Naranjo2004) fibulae, pendants, horse harnesses, and weapons are the most common artefacts, in La Yunta (García-Huerta & Antona, Reference García-Huerta and Antona1992), pottery, spindles whorls, and ornaments are dominant.

Material differences between regions have traditionally been related to the ethnic identities mentioned by Classical authors (Figure 1). The north-western Meseta has been attributed to the Vaccei, who inhabited vast territories, which seemingly only contain large oppida without subsidiary settlements (Sacristán, Reference Sacristán2011). The Vettones were settled in the south-west. One of their most distinctive characteristics was the creation of verracos, large granite sculptures in the shape of bulls, pigs, or wild boars, thought to be territorial markers and/or related to the control of resources (Álvarez-Sanchís, Reference Álvarez-Sanchís2005, Reference Álvarez-Sanchís2011). A smaller, mountainous area in the north-east was occupied by the Pelendoni, whose territory is located in the middle altitudes of the Sistema Ibérico mountain range, where small settlements without cemeteries have been recorded. Finally, according to the Greco-Roman sources, the Arevaci, the main protagonists in the wars against Rome in the region, were settled in the south-east, in the fertile valley of the River Duero (Jimeno, Reference Jimeno2011).

Textual evidence

The introduction of writing in our region is one of the innovations that came with the interaction with Rome during the second century bc. The people of the Meseta adapted the north-eastern Iberian script to the particularities of their local language, known as ‘Celtiberian’. This writing still poses numerous challenges to the specialists, as only some words and excerpts have been translated. Carved or painted on bronze and ceramic artefacts (tablets, coins, tesserae, vessels, spindles whorls, etc.), these pieces of texts correspond to proper names and place names or deal with topics such as the administration of lands and resources (Hoz, Reference Hoz and Jimeno2005; Bernardo, Reference Bernardo and Burillo2010).

Greco-Roman authors, including Appian, Strabo, Silius Italicus, Sallust, or Diodorus, provide the main textual evidence for the region. The Classical writings are tainted with otherness and alterity, following the defined political and social strategy of the Roman conquest and subsequent colonization (Clarke, Reference Clarke2001: 102; Laurence, Reference Laurence, Adams and Laurence2001). In addition, most testimonies were compiled several centuries after the events; thus, the information is likely to have been modified, romanticized and/or distorted. We must therefore consider these documents as a colonial source with a two-fold aim: to justify the Roman war, and to gather information on the geography and the people from regions that the Classical authors considered relevant. Consequently, the quality of the information is uneven (Wells, Reference Wells2001: 74–83, 103–18; Moore, Reference Moore2011: 352). Nevertheless, these documents are potentially extremely valuable for understanding some abstract social aspects that otherwise would be impossible to apprehend.

Although most Classical texts focused on the colonial war, there are some references to women, related to their appearance, activities, and collective practices. Socially, the Meseta women were mentioned as the keepers of memory, responsible for transferring community wisdom and history across the generations (Sallust, Historiae 2, 75). Regarding marriage customs, women were able to choose their husbands from among those deemed the bravest (Sallust, Historiae 2, 73). According to some textual evidence from other regions of Iberia (Strabo, Geography 3, 4, 17; Silius Italicus, Punica 3, 350–53), women were in charge of managing the household and cultivating the land, since men were mostly dedicated to warfare. Tacitus (Germania 15) identified these same practices in Late Iron Age temperate Europe too.

Describing the development of the Roman conquest in the region, Appian (‘Wars of the Romans in Iberia’, Iberike or Hispania.) frequently mentioned women in relation to their children and how they faced the war. Indeed, women acted as instigators, breaking into the oppida assemblies to speak out in favour of continuing the war (Sallust, Historiae 2, 75; Diodorus, Bibliotheca Historica 33, 16), and fought alongside the men when the war reached their doorsteps (Appian, Hispania 12, 72; Plutarch, Mulier 10; Polyaenus, Stratagems 7, 48). These references show how, though centred on household bonds and care, the social role of women was not limited by this.

Women in Funerary Evidence

The Meseta cemeteries contain a rich material culture in terms of the abundance and variety of artefacts, which have been extensively studied. Large cemeteries such as La Requijada and Las Quintanas (both in Gormaz) or Osma (locations on Figure 2) were discovered and excavated early in the twentieth century, yielding lavish grave goods, which now form part of major museum collections. Their excavators were mostly educated men interested in the past, at a time when Spanish archaeology was changing from amateur practice to a scientific discipline.

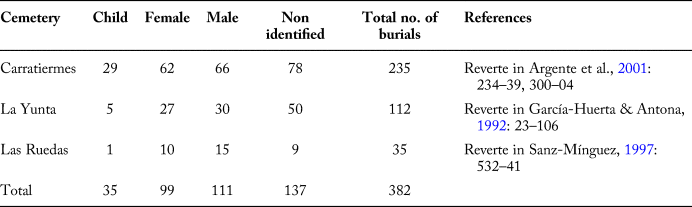

Unfortunately, records of burial distribution patterns and artefacts are scarce or non-existent, which poses a challenge when using gender approaches. This has led to the simplistic assumptions that graves with weapons corresponded to men, mostly warriors, and burials with personal ornaments were associated with women. In recent decades, Late Iron Age cemeteries such as those of Carratiermes, Numantia, El Pradillo, El Inchidero, La Yunta, Herrería, or Las Ruedas (Figure 2) have been excavated using modern techniques and, when possible, essential osteological data has been analysed, enabling us to compare age and sex profiles (Liceras-Garrido, Reference Liceras-Garrido2021) (Table 1).

Table 1. Sex and age of Late Iron Age individuals in the northern Meseta cemeteries analysed osteologically.

Often, Late Iron Age grave goods include weapons (mostly spearheads and daggers, frequently shields, and rarely swords and helmets); ornaments such as brooches, belt plates, pendants, or bracelets; and tools related to agricultural, livestock, or textile activities, among others. Regional variability is once again the main feature of these cemeteries. Differences are significant in both funerary practices and the grave goods. For instance, in the cemeteries of Numantia (Figure 3) or La Mercadera, metallic artefacts, such as personal ornaments or weapons, were deliberately folded. This practice has been interpreted as a way to make objects useless, to ‘kill’ them metaphorically when accompanying the deceased to the afterlife (Jimeno et al., Reference Jimeno, De La Torre, Berzosa and Martínez Naranjo2004). This practice has not been observed in other cemeteries, with only one similar example in Carratiermes where a small number of large artefacts (e.g. spearheads) were folded before insertion in the burial pits (Argente et al., Reference Argente, Díaz and Bescós2001: 242). The quantity of burnt human remains deposited in the grave also differs, averaging over 1 kg at Carratiermes (Argente et al., Reference Argente, Díaz and Bescós2001: 298) against 5.73 g at Numantia (Jimeno et al., Reference Jimeno, De La Torre, Berzosa and Martínez Naranjo2004: 439). Furthermore, remains were deposited in diverse ways depending on the cemetery. At La Yunta (García-Huerta & Antona, Reference García-Huerta and Antona1992), human remains were always contained in a ceramic vessel with a lid, while in most cemeteries no cinerary urns are present, the remains having been deposited directly into the ground.

Figure 3. Different burial types in Numantia (redrawn with modifications after Jimeno et al., Reference Jimeno, De La Torre, Berzosa and Martínez Naranjo2004: fig. 21).

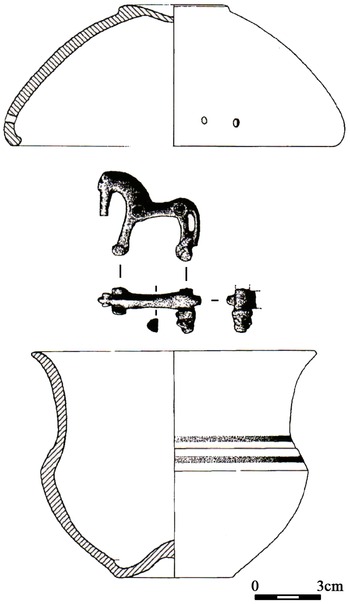

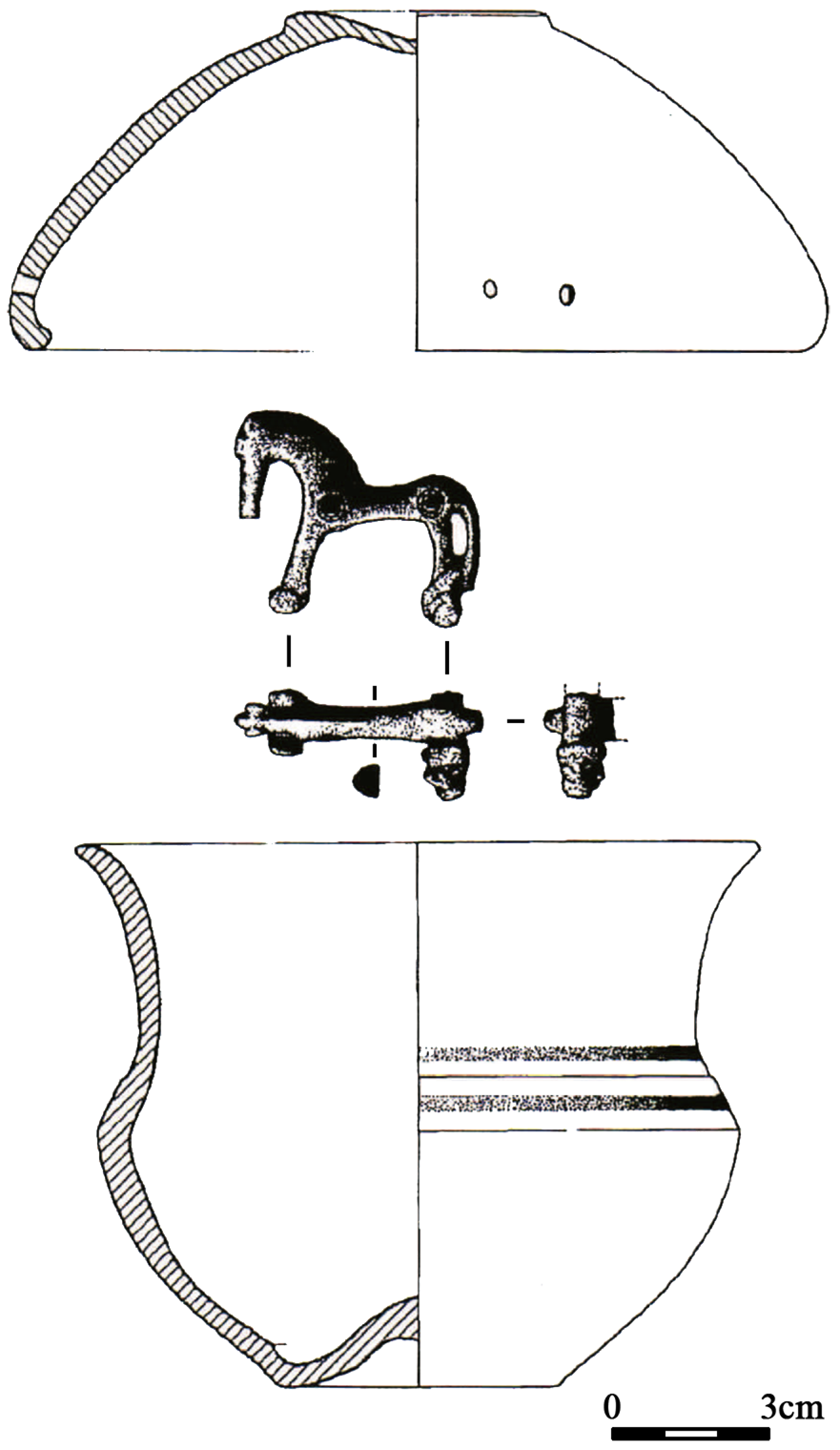

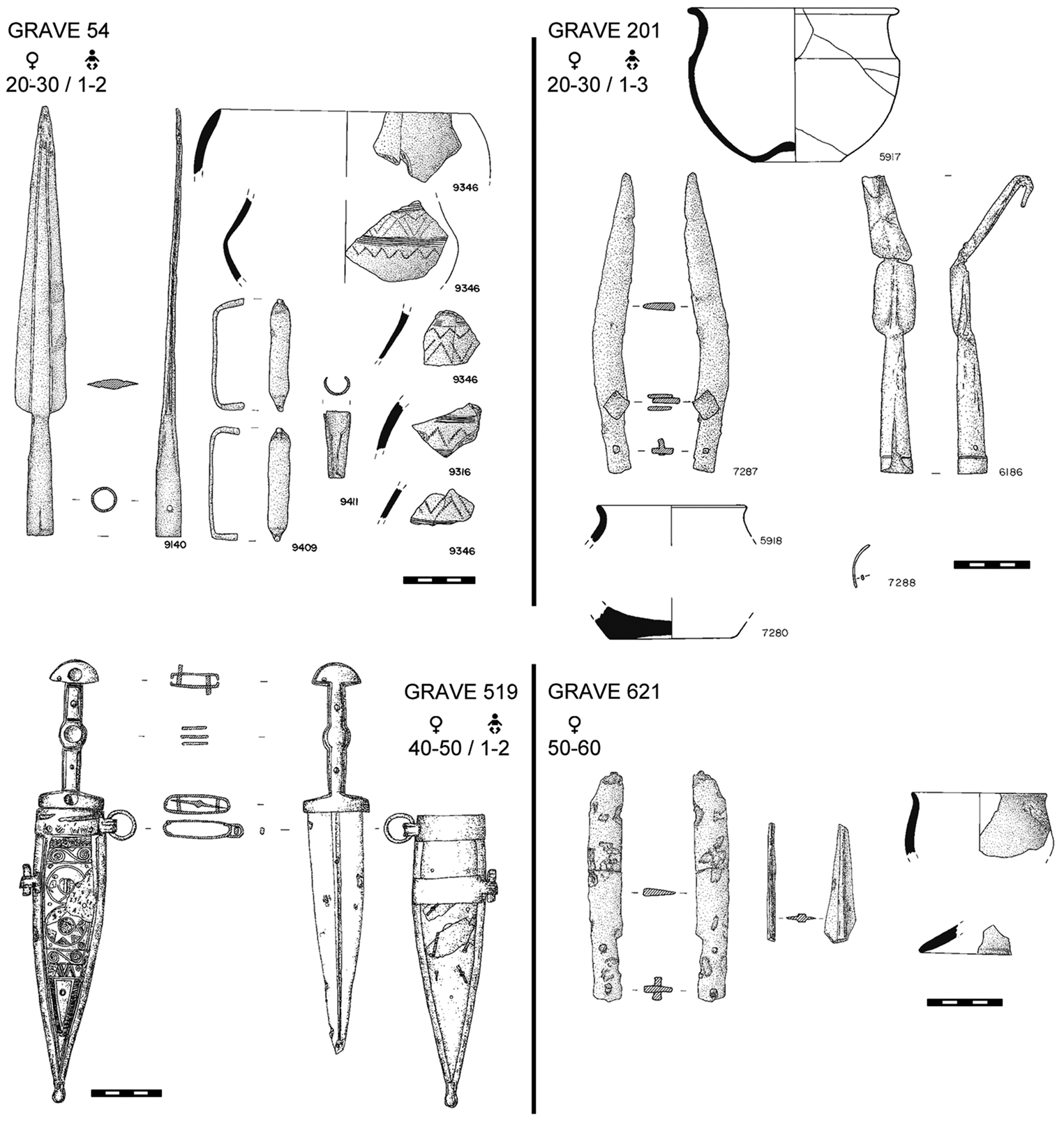

Since the mid-1980s, gender archaeology has been warning of the dangers of attributing certain elements of the material culture to a predetermined sex or age group (see Arnold, Reference Arnold, Walde and Willows1991; Prados-Torreira, Reference Prados-Torreira and Prados-Torreira2011), as objects traditionally associated with male warriors have been recovered in female and children's graves. A good example of this is the horse-shaped fibula, usually considered a marker of male equestrian elites (Almagro-Gorbea & Torres-Ortiz, Reference Almagro-Gorbea and Torres-Ortiz1999). Yet, the only fibula found in a grave with sufficient data to determine sex and age in our region was in the cemetery of La Yunta. This burial (Figure 4) is of an adolescent female between twelve and fifteen years old, accompanied by twenty-five goat talus bones perhaps used as gaming pieces (grave 74; García-Huerta & Antona, Reference García-Huerta and Antona1992: 75–76). Weapons provide another example. In the Meseta cemeteries, weapons were deposited with individuals of all ages and both sexes, including a double burial with an adult female and foetus, children, or individuals seventy years old (e.g. graves 262, 302, 347, and 607; Argente et al., Reference Argente, Díaz and Bescós2001) (Figure 5). The relationship between children and weapons is strong in most cemeteries. The distribution of weapons among ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ grave goods seems generally balanced, although differences exist between regions. Most of the female individuals buried with weapons were twenty–thirty years old, while the males were generally aged thirty–fifty, both age groups coinciding with the periods of highest mortality among adults (Liceras-Garrido, Reference Liceras-Garrido2021: 128–29).

Figure 4. Grave 74 of La Yunta (redrawn with modifications after García-Huerta & Antona, Reference García-Huerta and Antona1992: fig. 68).

Figure 5. Women and children's burial assemblages with weapons at Carratiermes (redrawn with modifications after Argente et al., Reference Argente, Díaz and Bescós2001: graves 54, 201, 519, 621).

A similar trend is visible among objects related to domestic production such as spindle whorls, sewing needles, wool shears, sickles, pickaxes, or gardening shears. Spindle whorls are represented in burials of females and males regardless of their age. La Yunta has the largest collection with 109 spindle whorls, equally distributed among males and females with the largest concentration in infant graves, according to osteological analyses (García-Huerta & Antona, Reference García-Huerta and Antona1992: 136; García-Huerta, Reference García-Huerta2013–2014: 318). Bronze and iron sewing needles are often found in the Numantia graves, associated with all sorts of materials. Finally, agricultural or livestock tools are usually found alongside weapons. In the cemeteries of La Mercadera, Numantia, Viñas del Portuguí, El Pradillo, and Carratiermes, sickles, pickaxes, or shears are often associated with daggers, knives, horse harnesses, and, occasionally, swords. Among all the burials that contained tools, two burials at Carratiermes (Argente et al., Reference Argente, Díaz and Bescós2001) had sufficient human remains to determine their sex and age. They belonged to males aged 30–40 and 60–70 (graves 6 and 263, respectively) but these sparse indications do not allow tools to be construed as gender markers. Overall, weapons, spindle whorls, needles, or agricultural tools do not suggest any type of relationship with gender or age identities; rather they speak of a link with the home, the family economy, or a source of wealth.

Given that funerary contexts are complex scenarios of social negotiation, identities such as age, social role, status, gender, or life stage should not be studied in isolation, but as dependant variables, as Bettina Arnold (Reference Arnold2016: 849–50) posits. In her analysis of the Heuneburg region in southern Germany in the Early Iron Age, she identified evidence that age may have been the primary organizing social category, while gender, status, or social role were dependant variables. By contrast, I have argued elsewhere (Liceras-Garrido, Reference Liceras-Garrido2021: 137) that, in the Iberian Meseta, the primary social category seems to have been the status of the lineage, with gender, age, or social role as secondary elements.

Households

Households are primary units for approaching past societies in terms of economy, politics, and social organization. Both the architecture and the material culture that they contain are vital for understanding living patterns (Allison, Reference Allison and Allison1999). According to the Classical authors, households were presumed to be the main arena of women's activities; hence these are preferential spaces to study the social role of women (Meyers, Reference Meyers, Dever and Gitin2003: 434). The type of structures, arrangement of space, complexity, diversity, or presence or absence of privacy could therefore shed some light on the relationships among the members of a household and beyond. For example, spatial syntax analyses (Westgate, Reference Westgate2007; Bermejo, Reference Bermejo2018) suggest that structures organized in a linear fashion lack rigid hierarchies and neither separate women from the outside world nor limit their contact with people outside the domestic unit. By contrast, complex, fragmented domestic space relates to isolation of women, specialization, and segregation (Westgate, Reference Westgate2007).

The Meseta domestic spaces are simple and linear. Houses are most commonly divided into three rooms and occasionally have an underground cellar. Behind the entrance, taking advantage of the light from the outside, a hallway served, according to the material record, as a space for storage and activities, such as grinding, weaving, etc. A trapdoor on the floor of this space would give access to the cellar (when present) for storage. The following room was the largest and contained a hearth and benches attached to the walls. Finally, a small pantry was located in the end room (Jimeno, Reference Arenas-Esteban and Belarte-Franco2009: 206).

Based on the eastern Meseta domestic units, Alfredo Jimeno (Reference Jimeno and Belarte-Franco2009) undertook mobility and visibility analyses to evaluate access and circulation through the different rooms of the houses, and to assess the degree of privacy within each. Since the excavations of the House Block XXIII at Numantia in 2009, I have been able to add one more instance to his study, House 4. For mobility, these analyses (Figure 6) suggest a linear route, which starts at the entrance, runs through each room, and ends in the last room with almost no boundaries. On the other hand, the visibility analysis shows how the first room has a strong public character, while the last room and especially the underground cellar (both for storage) have the highest degrees of seclusion. The room with the hearth, possibly because of its presence, is the room around which household life would revolve, hosting most of the daily activities such as preparation and consumption of food, caregiving tasks, craft, and production.

Figure 6. Accessibility and visibility of Upper Duero households (redrawn with modifications after Jimeno, Reference Arenas-Esteban and Belarte-Franco2009: fig. 14).

If we understand houses as the centre of the domestic unit and as a materialization of its members’ lives, these domestic spaces offer a low degree of segregation in two senses. First, only the hall or the first room separates the family space from the community (outside) and both worlds are connected by direct, easy access. The linear, open design encourages fluid relationships between the household and the whole community, i.e. the domestic space constitutes an extension of communal life. Second, the small size and the scant internal divisions create an unspecialized or only slightly specialized space, which limits the possibilities of internal segregation of both people and activities. This enables the household members to manipulate social links and negotiate their influence or power. Isolation and confinement were not characteristic of the Meseta Late Iron Age households, particularly since the largest room contained the hearth and most of household life. Furthermore, archaeological evidence suggests that most daily domestic activities may have taken place outside the houses or in open courtyards whenever possible (Märtens et al., Reference Märtens, Contreras, Ruiz-Zapatero and Baquedano2014). Consequently, the division of space offers little control over the interactions between household members, including women, and the outside.

Textile production

The domestic sphere has an influence on economic and political conditions, with households being privileged places to study production. They were spaces where economic operations were carried out, such as making, preserving, exhibiting, or redistributing goods, and houses are contexts in which artefacts used for milling, textile production, forging, tillage, or storage of products intended for, or gained from, commercial activity are found (Gorgues, Reference Gorgues2010). Therefore, house complexity and layout may have been related to economic activities, in which structures that are more complex may imply a greater labour force, economic capital, or power (see Brumfiel, Reference Brumfiel, Gero and Conkey1991). In some instances, it has been possible to establish how production exceeded the needs of the household unit: this is the case of the textile manufacture of Mas Boscà (Badalona, Catalonia), where at least four looms and more than ten scattered spindles whorls were recorded. This suggests that at least four women were engaged in textile-related activities, their output exceeding the requirements of the household members and constituting an intentional surplus (Gorgues, Reference Gorgues2010: 123–48).

Archaeological, iconographic, and textual evidence suggests that in many societies spinning and weaving were primarily carried out by women (Barber, Reference Barber1991: 283–98; Meyers, Reference Meyers, Dever and Gitin2003: 432–34; Rafel-Fontanals, Reference Rafel-Fontanals2007; Prados-Torreira & Sánchez-Moral, Reference Prados-Torreira and Sánchez-Moral2020: 130–31). Despite the number of houses excavated with modern techniques in the Meseta, detailed material records are still scarce. Yet, evidence of textile working, such as spindle whorls, loom weights, needles, etc., have been documented and may suggest surplus production, particularly of woven wool fabrics known as ‘saga’. Saga were cloaks or blankets, frequently mentioned by Classical authors due to their use as currency in commercial and political transactions, such as the negotiation of truces and surrenders signed between Rome and the Meseta oppida. Some textual references narrate how the oppidum of Intercatia delivered 10,000 saga to Consul Licinius Lucullus in 151 bc (Appian, Hispania 54), and how Termes and Numantia paid 9000 saga each in 141 bc (Diodorus Bibliotheca Historica 33, 16). Considering that the estimated population of the oppidum of Numantia was around 1500 people, or 8000 people if we include its entire territory (Liceras-Garrido & Quintero, Reference Liceras-Garrido, Quintero and Jimeno2017), the production of 10,000 or 9000 saga would have required a well-established productive infrastructure, supported mainly by domestic units and presumably led by women (cf. Brumfiel, Reference Brumfiel, Gero and Conkey1991).

Feasting and drinking

Feasts are one of the most recognized power strategies used to forge, maintain, and nurture power relationships in the Iron Age. They are deeply linked to specific elements of material culture (e.g. cauldrons, tableware, meat hooks, etc.) and alcoholic beverages, such as wine or beer. Women were in charge of managing the house and may also have been responsible for producing the ingredients for banquets since, as noted earlier, Classical authors mention that women cultivated the land in neighbouring regions (Strabo, Geography 3, 4, 17; Silius Italicus, Punica 3, 350–53). This is also supported by the osteological analyses of the Carratiermes cemetery, where the powerful musculature of the forearms of some women is thought to reflect heavy activities such as tilling or grinding (Argente et al., Reference Argente, Díaz and Bescós2001: 295). In addition to agricultural production, women may have been responsible for caring for small domestic animals (e.g. poultry), as well as dealing with planning, cooking, and serving meals (Mirón-Pérez, Reference Mirón-Pérez and Sánchez-Romero2005; Montón-Subías, Reference Montón-Subías and Sánchez-Romero2005).

Alcohol is central to any banquet; an essential element for manipulating political relationships, it played a significant role in the construction of authority (Dietler, Reference Dietler, Dietler and Hayden2001). For the eastern Meseta, the most relevant alcoholic beverage was caelia, a beer brewed mainly from wheat. Preparing beer for communal consumption requires investing substantially in agricultural resources and culinary activity. Using anthropological examples from pre-industrial contexts, a house in Botswana allocates fifteen to twenty per cent of its cereal production to making beer (Dietler, Reference Dietler, Dietler and Hayden2001: 81–82) and the Bemba of Zambia use 400 pounds of millet per year for brewing, which accounts for seventeen per cent of their production (Richards, Reference Richards1939). In terms of preparation effort and social benefit, the anthropological examples also reveal gender inequalities (Dietler & Hayden, Reference Dietler, Hayden, Dietler and Hayden2001; Jennings & Chatfield, Reference Jennings, Chatfiel, Jennings and Browser2009; Vogel & Cutright, Reference Vogel, Cutright and Bolger2012). In all documented cases, women mostly carried out the farming and brewing activities.

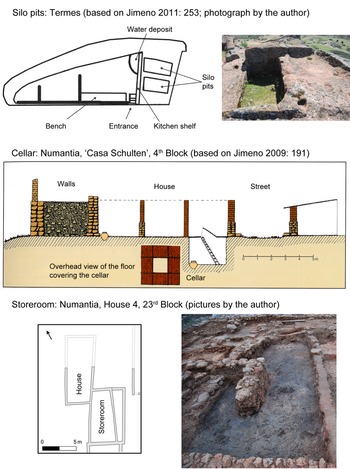

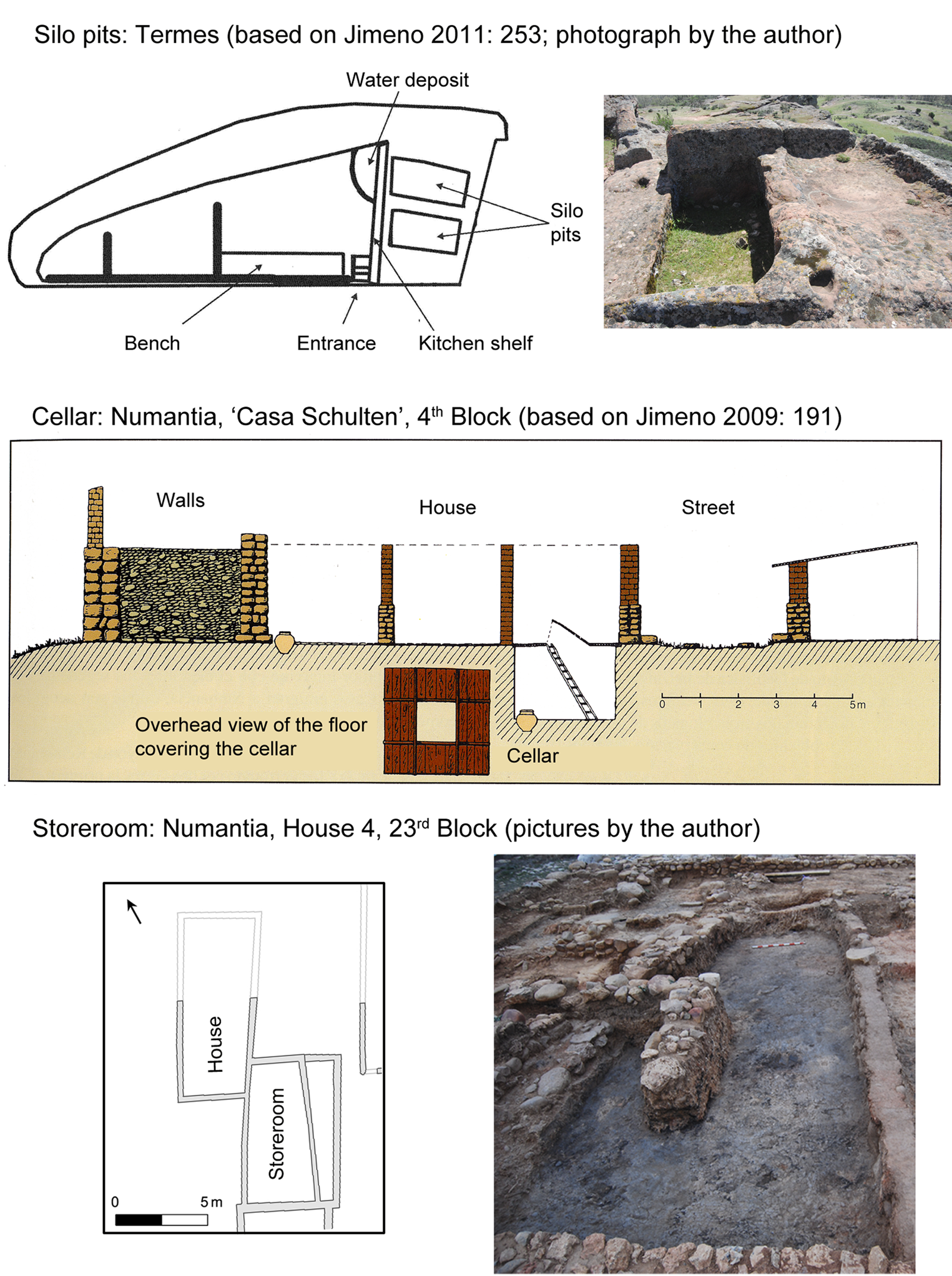

These productive activities and surplus accumulation would have required storage structures. In the Meseta, there is no evidence of communal storage structures in the oppida, suggesting that this responsibility lay in the domestic unit. Three main types of storage have been recorded at the region (Figure 7): storage pits excavated in the Termes bedrock, underground cellars in Numantia and Los Villares (Ventosa de la Sierra), and storage rooms attached to houses such as those in Los Casares (San Pedro Manrique) and Numantia. These storage spaces accumulated a large number of ceramic vessels of all kinds, as well as other items for domestic production. In Numantia, a storeroom attached to a house recorded in 2009 contained around 100 artefacts in a space measuring 22 m2 (Jimeno et al., Reference Jimeno, Chaín, Quintero, Liceras-Garrido and Santos2012). Most of the artefacts were pottery, including several types of storage vessels (for liquids and grain), bowls, cups, pots, jugs, lids, mortars, and gaming pieces. Also recovered were sewing needles and ceramic and stone loom weights for textile production, chisels for woodworking, a mould to produce annular fibulae, deer antlers with evidence of extraction for carving handles, a razor, and some personal ornaments such as a bronze ring. Similar examples of storage structures are known from El Palomar (Aragoncillo, Castilla-La Mancha) in the Upper Tajo region (Arenas-Esteban, Reference Arenas-Esteban and Jimeno2005: 397) and in the Iberian houses from La Bastida de les Alcuses or Sènia (Grau, Reference Grau, Gutiérrez and Grau2013: 60–62). These structures conserved and stored the supplies necessary for daily life, the celebration of certain events, and/or commercial exchanges.

Figure 7. Storage structures in northern Meseta households.

The household was therefore one more stage of social negotiation, consisting of open and accessible spaces in fluid and constant communication with the outside. Households were also production units capable of generating surpluses to trade or support the community in times of need (e.g. textiles) and to create an excess for conspicuous consumption (e.g. food and alcohol). The daily activities of women were linked to their households through maintenance activities and domestic production. On this basis, we can argue that women were responsible for most of the household production and the management of the different tasks, times, and resources of these units. Although the ability to mobilize and consume resources in a relatively public event may have benefited all members of the household in the arenas of authority and political power, men may have been the main beneficiaries, appropriating the work and effort of the women. Nevertheless, all unit members may have been able to improve their social position within the community by the mere fact of belonging to the household. Women would have been participants in the social recognition and status of the household identity, although at different scales and with differing benefits.

Concluding Remarks: An Iron Age with Women

I have tried to demonstrate that women's activities were crucial to understanding how Iron Age societies worked, despite them having been considered secondary by traditional approaches. Women maintained and nurtured the social bonds through maintenance activities, underpinned social cohesion, participated in the economic sphere via domestic production, contributed to improve the social position of the household and family, and transferred knowledge and rights.

Late Iron Age communities comprised both hierarchical and heterarchical networks (Fernández-Götz & Liceras-Garrido, Reference Fernández-Götz, Liceras-Garrido, Ray and Fernández-Götz2019). Hierarchy has been equated (sometimes explicitly, often implicitly) with masculine power; thus, the models of emerging social complexity and its articulation have made women mostly invisible, ignoring potential complementary sources of influence and power (Levy, Reference Levy, Ray and Fernández-Götz2019). These present triangular or trapezoidal societies, in which the upper echelons enact masculine roles (chiefs, warriors, merchants, blacksmiths, other artisans, etc.) with women, children, and some elders lower down the ranking. By contrast, Crumley (Reference Crumley1995: 3) defines heterarchy as ‘the relation of elements one to another when the elements are unranked or when they possess the potential for being ranked in a number of different ways’. This flexible theoretical framework enables archaeologists to explore broader axes of prestige, sources of power, and agency beyond the traditional paradigms, as well as to consider the shifting interactions of the daily activities of all members of a community, not merely those of its chiefs or leaders.

Using this idea of heterarchy and gender, Carol Meyers (Reference Meyers, Dever and Gitin2003: 437) suggested that women's activities worked as heterarchical subsystems, each with their own patterns of ranking, privilege, and status. Within these subsystems, some women were able to manipulate social relationships to advance their own ends, exercising leadership and even dominance. Some anthropological examples help illustrate how these subsystems work in current or preindustrial societies. Among the Toba Barak in Sumatra (Rodenburg, Reference Rodenburg, Sparkes and Howell2003), men were not the only household members capable of increasing the capital of the house, since women were the managers of the domestic economy and its resources. This is particularly relevant when their husbands explored other forms of power outside the limits of their settlements (González-Ruibal, Reference González-Ruibal and Belarte-Franco2009: 249).

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Meseta communities were open domestic units. Women would not have been confined, as occurred in Ancient Greece (Blundell, Reference Blundell1995; Mirón-Pérez, Reference Mirón-Pérez and Sánchez-Romero2005), or limited. In the Iron Age Meseta, the linear design of the houses shows a society that did not limit the contacts and relationships of the members of a household with the rest of the community. Women would have been able to negotiate and maintain fluid relationships with other members inside and outside the household.

Funerary contexts also reveal the existence of socially relevant female individuals buried with grave goods related to symbols of power (weapons, horse harness), body appearance (ornaments), or the consumption of food during funerary rituals (pottery, animal remains). Moreover, in neighbouring areas such as the south-eastern Iberian Peninsula, female burials have similar features attesting to their relevant social position within communities and the transmission of lineage rights (Izquierdo, Reference Izquierdo2007; Rísquez & García-Luque, Reference Rísquez and García-Luque2007; Rísquez, Reference Rísquez2015; González-Ruibal & Ruiz-Galvez, Reference González-Ruibal and Ruiz-Galvez2016; Ruiz-Galvez, Reference Ruiz-Gálvez2018). Finally, as we have seen, the testimonies of the Classical authors portray women as active social agents in at least three major contexts: in marriage, in wars (as instigators and fighting alongside men when conflict reached their villages), and as keepers of memory and transmitters of community wisdom and history.

Since the fourth century bc, Meseta warriors under the Roman ethnonym ‘Celtiberians’ were well-known as mercenaries across the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean. Artefacts, such as the Hispanic-Calcidic helmets (Graells et al., Reference Graells, Lorrio and Quesada2014) or the human and hybrid representations on the pottery from Numantia (Jimeno et al., Reference Jimeno, Chaín, Quintero, Liceras-Garrido and Santos2012) were the result of the cultural impact of their trips. Furthermore, in the cemeteries of the northern Meseta, there is a general absence of males under thirty years old (Liceras-Garrido, Reference Liceras-Garrido2021: 124–27). This contrasts with an increase in female mortality between the ages of twenty and thirty, possibly related to pregnancy, childbirth, and breast-feeding. Both the absence of young males in the cemeteries and the references by Classical authors to their travels as mercenaries suggest that women would have stayed in charge of the organization and management of the domestic and productive sphere, at least temporarily. This would imply that women had a degree of agency and influence in power and production structures. Indeed, while the spheres of women's influence were different from those of the men, these would have been equally relevant for the social configuration and the proper functioning of the community.

Approaching past societies requires understanding women's contributions to these communities. By bringing women to the centre of the narrative in the Late Iron Age Iberian Meseta, I hope to have shown how they were key agents in shaping society. Women were able to develop a wide range of social strategies and agency through their roles as mothers, wives, household managers, protectors of family lands, and supporters of emotional bonds. This offered them scope to improve their own social position and the status of their families within their communities.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sergio Quintero, Alba Comino, and Katherine Bellamy for their comments on an earlier draft of this article and their support while carrying out this research.