Introduction

The Schrems I judgment by the Court of Justice of the European Union was a case to remember.Footnote 1 The Court quashed Commission Decision 2000/520 (the ‘Safe Harbor Decision’), which allowed for personal data transfer to the United States, assuming that the safe harbour privacy principles applicable to US-based organisations ensured an adequate level of protection. The Court declared the invalidity of Decision 2000/520 under EU law on the ground that the right to respect for private life (Article 7 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union) and to effective judicial protection (Article 47) were not simply infringed by the Decision, but radically deprived of their very essence,Footnote 2 a notion enshrined in Article 52(1) of the Charter. Article 52(1) was not quoted explicitly in Schrems I,Footnote 3 but the concept of essence was directly recalled.Footnote 4 This marked a departure from the previous Digital Ireland case, in which the so-called Data Retention DirectiveFootnote 5 was quashed based on a ‘serious limitation’ of the right.Footnote 6

The idea that rights have an essence or core is not new. Countries like Germany and Spain are equipped with general constitutional clauses on the essence of rights.Footnote 7 In other cases, like Italy, France, or the European Convention on Human Rights, protection of the essence is either guaranteed for specific rights (in opposition to general clauses) or a doctrinal construction.Footnote 8 Moreover, before the Charter the Court of Justice used to talk about the ‘substance’ of rights, a notion which clearly influenced the drafting of Article 52(1).Footnote 9 In this sense, Schrems I is the prosecution of an ancient line of cases in which the Court relied on the substance of rights.

I will not enter further into the details of this historical and comparative reconstruction. The point is that, after Schrems I, the idea of an essential content of rights has attracted scholars’ attention. In the literature on Article 52(1) a question was asked, but never answered in a fully satisfactory way: how do we establish what is the essential content of a specific right? I call this the question of method. To account for it, in this article I raise two issues, one theoretical, the other empirical.

As for the theoretical issue, the perspective I would like to adopt here is that of the theory of rights. When addressing the question of method, scholarly approaches adopt two different theories, the absolute and the relative theory.Footnote 10 The absolute theory draws a firm line between the core of a right, which is assumed as untouchable, and a periphery which, conversely, might be sacrificed. According to this approach, while one may interfere with the periphery of a right to realise a competing one, no limitation of the core would be legally acceptable. Moreover, the essence of a right shall not be established through proportionality, as a proportionality assessment would inevitably involve mutual adjustments and limitations between rights. The relative theory, on the other hand, claims that every interference with a right can and shall ultimately be justified through proportionality, including limitations of the core. I am going to argue that current debate, summarised in next section, should be grounded on a wider jurisprudential discussion about the nature of fundamental rights and that this perspective, in my opinion illuminating, is currently lacking. My aim is to fill this lacuna by relying on a specific theory of rights, namely a version of the so-called interest theory, which sheds light on the debate between the absolute and the relative theories, to the advantage of the latter.

As for the second issue, the empirical one, I would like to consider how the Court interpreted and applied Article 52(1) by selecting and analysing a sample of post-Schrems I cases. I will then try to explain the selected cases by means of the interest theory of rights.

As a result, this analysis will show that a crucial notion in the Charter, that of essence, must be understood by relying on the relative theory if we want to avoid conceptual mistakes and, most importantly, high yet fragile hopes.

What is the essence of a right?

Let us start by first quickly recalling the debate between the absolute and the relative theory on Article 52(1) of the Charter. I will then situate this controversy within the larger debate on the nature and structure of rights in jurisprudence and introduce the approach I find most convincing in that field, namely a specific version of the interest theory of rights.

The riddle of Article 52(1): absolute and relative theories

It has been claimed that a fair reading of Article 52(1), which provides criteria for lawful limitation of fundamental rights under EU law, requires a dissection into six autonomous conditions: (a) limitations must be provided by the law; (b) the essence cannot be subject to limitations; (c) limitations must have a legitimate aim in that they correspond with the objectives of general interest recognised by the EU or the need to protect the rights and freedoms of others; (d) limitations ought to be necessary for genuinely reaching the legitimate aim; and (e) must conform to the principle of proportionality.Footnote 11 By recalling the subsequent Article 52(3), one might also add a further consideration: (f) that limitations must be consistent with the Convention.

However, bearing in mind the structure of proportionality, this list can be greatly simplified.

Proportionality is usually conceived as a three-Footnote 12 or four-stageFootnote 13 argumentative structure used to assess whether a certain public decision is suitable to achieve its goals and does not entail unnecessary or disproportionate sacrifice of competing interests. Relying on the four-stage model, we first assess whether a certain measure is enacted in a regular manner and aimed at an admissible goal (the rule of legitimacy). The measure must also realise the primary goal, even if it harms the competing right (the rule of suitability). The third step is the rule of necessity or ‘less restrictive means’:Footnote 14 given two suitable measures, it is necessary to choose the one that entails the lesser sacrifice for the sacrificed principle. Suitability and necessity are instances of the general criterion of Paretian efficiency.Footnote 15 Finally, we find the rule of proportionality in a narrow sense. The greater the sacrifice, the greater must be the realisation of the competing right.Footnote 16 A particularly great sacrifice (even if it is legitimate, suitable, and necessary) would still be disproportionate if paired with a modest protection of the competing right.Footnote 17

Returning to Article 52(1), conditions (a), (c), and (f) instantiate legitimacy, respectively in relation to EU or domestic law ((a), (c)) and to the Convention ((f)). Condition (d) coincides with suitability and necessity. As a result, one is left with the instruction that limitations of fundamental rights under the Charter must be proportionate (conditions (a), (c), (d), (e), (f)) and respect its essence ((b)). The riddle of Article 52(1) is, therefore, whether the conditions for the acceptability of fundamental rights’ restrictions under EU law ultimately collapse on proportionality aloneFootnote 18 or whether it is possible to disentangle essence from proportionality.

According to the absolute theory it is indeed possible to distinguish a core that cannot be legally limited. If the latter is harmed, then the right simply disappears.Footnote 19 Likely, this view is both descriptive and normative. On the one hand, rights have in fact a core and a periphery, which can be distinguished (descriptive); on the other hand, it is better if we apply proportionality only to the periphery of the right (normative).

It is important not to conflate the claims of the absolute theory with the view that admits the existence of ‘absolute’ rights, i.e. rights so fundamental to be unlimitable (as opposed to relative and limitable rights, as propertyFootnote 20). An absolute right can only be violated, i.e. unjustifiably infringed, and never overridden, i.e. justifiably infringed.Footnote 21 Examples include the ban on torture and degrading treatment or the prohibition of slavery. Absolute rights are ‘all essence’ – rights made of core only.Footnote 22

In the relative theory, conversely, all interferences with fundamental rights can be assessed through proportionality. This can be interpreted as a normative view (that we shall better assess interferences through proportionality) and as a description, namely that this is de facto how we behave. Authors such as Robert Alexy and Aharon Barak,Footnote 23 who endorse it, seem to conceive it in the normative sense. In the following paragraphs I will advocate for a descriptive version of the relative theory, claiming that as a matter of fact this is how we conceive rights. However, this statement must be interpreted in a weak sense that will become completely clear only later in the article.

When it comes to the debate on Article 52(1), the absolute theory seems to prevail. Several supreme or constitutional courts in Europe have endorsed this approach, including influential institutions as the German and the Spanish Constitutional Courts.Footnote 24 At the moment, the most famous supporter of the relative theory in the judicial arena is perhaps the European Court of Human Rights, and its support is not consistent.Footnote 25 Moreover, various scholars have endorsed the absolute theory. Maja Brkan, who wrote an extremely sophisticated article on the matter, explicitly argued for the absolute theoryFootnote 26 and so did Tuomas Ojenen, when commenting on Schrems I.Footnote 27 Takis Tridimas and Giulia Gentile took a more ambiguous stance, yet they seem to me closer to the absolute theory.Footnote 28 Finally, an undisputed prestige was given to this approach when it was approved by Koen Lenaerts, the current President of the Court of Justice, who revealed his stance in the German Law Journal.Footnote 29

The support for the absolute theory is hardly surprising. The sheer distinction between core and periphery seems to many to be more faithful to the text of the Charter.Footnote 30 Second, it squares with the history and precedents of the Court, which relied extensively on the equivalent notion of substance.Footnote 31 Finally, it appears ethically more fitting, as it allows a line to be drawn in the sand between acceptable and unacceptable limitations of a right. As Lenaerts points out, ‘the concept of the essence of a fundamental right operates as a constant reminder that our core values are absolute and, as such, are not subject to balancing’.Footnote 32

It is crucial to realise how the two theories diverge when it comes to the question of method, namely how the core of a fundamental right is determined.

The relative theory hinges on proportionality. If every limitation is determined through proportionality, then the answer to the question of method inevitably is that we determine the core, and whether it was touched, through proportionality too. Intuitively core-infringing measures, as in Schrems I, are just exceptionally disproportionate limitations and the difference between it and cases like Digital Ireland is merely one of scale. As Brkan correctly points out, in the relative theory the notion of essence mostly has a declaratory value.Footnote 33

Scholars supporting the absolute theory, on the other hand, give different answers. Lenaerts, for instance, argues that the Court first establishes that the essence was not violated and only later engages in a proportionality assessment.Footnote 34 This two-step method is clear, but the comments on how the first step should be accomplished are not always specific. We know that essence is not violated when the right is limited in specific circumstances only, and only to a certain extent.Footnote 35 Yet, this is helpful to a certain point as an abstract method for the identification of the core. It does not specifically state how to establish that something is the essence of a right.Footnote 36 Moreover, it reinforces the view that the core-periphery difference is merely one of scale.

Brkan’s attempt to provide a method to determine the essence of a right under EU law is rather articulated.Footnote 37 She proposes a two-step test based on: (a) whether the interference calls into question the very existence of the right for rights holders; and (b) whether there are overriding legal reasons for such interference. Essence is violated when the right ceases to exist for all right-holders or for a subset of them and when there are no reasons of at least equal legal weight to justify the restriction. This is a quite well-developed attempt to address the question of method, but there are some remaining concerns.

As for the first step, it is doubtful that it can work as a relevant method to establish the essence. Truly, every time a right is outweighed, it will ‘cease to exist’ for the right holder, at least in the minimal sense that a specific application of that right will be forbidden. If, for instance, it is forbidden to publish information regarding someone’s personal life if it does not satisfy a general interest, then, for the journalist involved, the freedom of the press simply disappears. The problem is in knowing why the ban on a certain application of the right is so basic as to be essential, while others are not. It seems likely that the example just given would represent a reasonable and non-essential sacrifice of the freedom of the press. Yet, why is this not essential, while other sacrifices are? Recalling that infringing the essence makes the right disappear for the holder is correct, but begs the question of what the core of the right is as opposed to unessential applications.

As for the second part of the test, it tells us that when it comes to the essence, there are no reasons of an equal legal rank (or no legal reasons at all) to justify the interference. Overriding reasons are legally acceptable insofar as they preserve fundamental rights of others in the Charter or equally weighty ‘general interests’ recognised by the Union.Footnote 38 But this amounts to a definition of what the essence is, rather than an operative criterion to establish it. Essence’s infringements are such that no overriding reasons exist, but how do we know that they do not exist? Unworthy limitations, outside the catalogue of acceptable overriding reasons (rights of others or general interests), could be equally quashed through proportionality in the legitimacy assessment.Footnote 39 Yet our concern, i.e. why some limitations would affect the core while others would not, remains unanswered.

In other words, we are left with the sense that the answers to the question of method provided by the absolute theory are still unsatisfactory.

A fresh start: a theoretical assessment on the essence of fundamental rights

In the previous section I considered the recent debate on Article 52(1) as centred on the distinction between an absolute and a relative conception, with the former currently prevailing among scholars: for reasons that are textual, historical, and ethical, the idea that proportionality shall not be used to establish the essence of a right turns out to be more appealing. However, the absolute theory seems problematic when the question of method is raised. While the relative theory emphasises balancing through proportionality, and thus treats the essence by assigning a very high abstract or concrete weight to the infringed value, the absolute theory crumbles in defining a proper method.

In this section I assess the jurisprudential foundations of both the absolute and the relative theories and show why a certain interpretation of the latter is, in my view, convincing. This requires some exposition of the main tenets of contemporary fundamental rights’ theory. Such abstract study hardly appears in the current literature on Article 52(1). In part, this is understandable and perhaps even healthy: positive law must often be assessed by considering its current practice and this is what several authors have done. I agree with this approach to the point that the next section will be devoted to a similar inquiry.

However, the notion of essence is itself metaphysical and almost esoteric. It requires a deeper understanding of fundamental rights, before we can understand its relations with proportionality and how we can establish its content (the question of method). Let us start, then, by looking at the jurisprudential debate on what a fundamental right is.

As for the adjective ‘fundamental’, I adopt a functional definition which labels as fundamental only those rights used as grounds of validity of other norms, rather than more substantive views.Footnote 40 Although it is reasonable that we rank the values of political morality at the basis of legal rights hierarchically,Footnote 41 this ranking is inevitably controversial. Instead, by focusing on the role that some rights perform in legal practice (grounds of validity), the functional view proves simpler to use, clearer, and more explicative.

As for the definition and structure of ‘rights’, we need to introduce a more complex analysis. Broadly, legal rights are positions of benefit or advantage secured to persons by law.Footnote 42 Yet, this definition is so extensive as to be almost useless. A more refined analysis is usually grounded in Hohfeld’s famous works on legal conceptions.Footnote 43 He identified four fundamental legal relations or conceptions, i.e. claims (or rights stricto sensu), privileges (or liberties), powers, and immunities, and four correlatives/opposites (duties, no-rights, liabilities, and disabilities). Correlatives are relations necessarily involved by the existence of another fundamental relation, while opposites are necessarily excluded by the existence of a fundamental relation. Correlatives and opposites just rephrase the definition. The fundamental relations are held by physical persons (or groups) or by artificial persons like states or corporations.Footnote 44

Hohfeldian relations logically entail very few consequences, namely their respective correlatives and opposites, but they are often coupled with further relations for practical reasons.Footnote 45 For example, a minor may lack the power to form a contract. His incapacity per se does not logically place an incapacity on me too, but practically I am not able to form a contract with him.Footnote 46 Thus, rights are often described by the fundamental relations and by their mutual logical and practical connections,Footnote 47 which Hohfeld himself defined ‘lowest common denominators in law’.Footnote 48 One would rarely describe a legal right through a single Hohfeldian relation though. Perhaps one might think about basic immunities, such as the legislative immunity of representatives from prosecution, but few rights really are that simple. If we think about these extremely simple rights as ‘atoms’, made of single relations, then we might imagine the vast majority of rights as ‘molecules’.Footnote 49 To recall the wording used by Judith Thomson, most rights are ‘clusters’ of Hohfeldian relations,Footnote 50 internally connected by relations that, as we have seen, are both logical and practical. For instance, think about freedom of speech: it ordinarily entails the privilege to express personal thoughts, that of freely deciding to keep quiet,Footnote 51 the claim that others shall not interfere with these freedoms, the power to recur to judicial protection against public powers or private persons (or not to), and so on.Footnote 52

This analysis is static, as it shows the anatomy of a cluster-right at a certain moment in time. However, rights often change over time. The exact amount and combination of fundamental relations that are needed to protect a rather abstract and contested right such as freedom of speech might vary over time, as societal conditions (public morality, institutional settings, civil society, technology, and so on) change. This helps us to define the dynamic aspect of rights, namely the fact that the exact cluster of Hohfeldian relations used to enforce and safeguard the right changes over time.Footnote 53

One can already see something crucial to our argument here, something that amounts to a first critique of the absolute theory. If rights are clusters of elementary legal relations that change over time, then perhaps not all of these relations have the same role in defining the right. For instance, consider this example: the criteria for restoring property after public expropriation have changed in Italy in recent decades. In particular, after a pivotal decision by the Court of Strasbourg and two by the Constitutional Court,Footnote 54 financial compensation increased significantly. In Hohfeldian terms this would mean that the criteria to calculate the compensation were substituted with new ones: citizens could claim their application and officials were under a duty to apply them. Therefore, the cluster of deontic relations changed accordingly. However, it would be difficult to deny that the right to property existed even before 2007, although the cluster would have had a slightly different composition. New criteria, which strengthened property rights, were clearly not important enough to affirm the existence of the right. However, if Italians had not been allowed to own any good before 2007, or if no claim to compensation after expropriation was allowed at all, we would probably say the opposite. In other words, not all Hohfeldian relations are equally important in establishing and safeguarding a right. This leads us to order the elementary relations by their importance, starting from the core and finally getting to the periphery, or the ‘protective perimeter’, to quote Hart.Footnote 55

If we recall the distinction between the absolute and the relative theory, this might provide a first argument for the relative theory. If we distinguish between core and perimeter based on how important these relations are to protecting or enhancing the right, then the distinction is one of scale, for importance is quantitative. Hohfeldian relations can be more or less important for a right. If so, then the relative theory better fits our theoretical understanding: it squares with the jurisprudential view that the core-periphery distinction is relative, something that is not available to absolute theory’s supposedly sharp distinction.

But this is not all: after further elaboration, one can also draw from the theory of rights a second argument against the absolute theory. In order to do this, it is necessary to introduce the classic distinction between the will and the interest theory of rights.

Rights are clusters of Hohfeldian relations, structured in a seamless stream from the core to the perimeter. A crucial question at this point is: how do we pool the various clusters together to make one right? Some Hohfeldian relations or clusters seem unlikely to protect any right.Footnote 56 Moreover, how do we know that some legal relations, often spread in a variety of different sources of law, protect the one and same right?

Here one finds a divergence between two options, namely the will and the interest theory.Footnote 57 They explain differently the reasons why we are justified in thinking that a cluster constitutes a certain right.

According to the will theory (or choice theory), rights are faculties conferred on persons to exercise their will over others’ duties.Footnote 58 The right is understood as a little fief of elementary legal relations over which the holder exercises dominion at discretion in terms of claiming, waiving, or enforcing the correlative duty. As a result, those Hohfeldian relations which are necessary and sufficient to serve the holder’s will shall be pooled together into one right.

In the interest theory (or benefit theory), on the other hand, rights are clusters of elementary relations aimed at enhancing one aspect of the holder’s well-being (his or her interest). Therefore, once a social interest is identified as legally binding,Footnote 59 a cluster of Hohfeldian relations constitute that right as long as it is instrumental to the protection and enhancing of that interest.Footnote 60

Both theories can be criticised on various grounds.

The choice theory is based on the picture of the right-holder as a small-scale sovereign and it emphasises the role of rights in empowering free moral agents.Footnote 61 Yet, it makes quite hard to explain the existence of rights whose holders are not able to express any will at all. The rights of those who lack competence – such as children, animals, or comatose persons – are typical examples.Footnote 62 Moreover, the choice theory entails the large-scale possibility of waiving rights, a possibility that does not square with the so-called unwaivable rights.Footnote 63

The interest theory, on the other hand, might be in trouble when facing the rights of officeholders: judges, for instance, have the right to alter others’ normative sphere, but it is doubtful that this power-right they possess is exercised in their own interest.Footnote 64 Here interest-theorists are forced to say that officeholders have themselves an instrumental interest in enforcing someone else’s protective perimeter (e.g. the plaintiff in tort lawsuits), with a certain distortion of our prima facie intuitions.

This is no place for a full-fledged discussion of the relative merits of the two accounts. However, here I endorse the interest theory, based on two propositions. First, on balance, it is in my view more comprehensive, i.e. it accounts for a wider set of pre-theoretical commitments and intuitions regarding the notion of legal right. As long as an account is able to explain more intuitions than another, it is preferable. Second, it has a larger explanatory power regarding the issue at stake in this article. Within the interest theory, conflicts between rights are inevitable and easier to conceptualise.Footnote 65 It offers a richer toolkit with which to examine an area, that of limitations of rights under Article 52(1) of the Charter, where conflicts seem unavoidable. The interest theory seems more in line with our contemporary ‘age of balancing’,Footnote 66 in which rights are numerous, broadly defined, and inspired by quite different worldviews, as the Charter itself seems to assume. Moreover, it also allows us to distinguish between extremely intense interferences with the right, infringing the application of the most fundamental Hohfeldian relations, and the call into question of the right itself, which equates to full denial of the necessity to entrench the interest. Making sense of this distinction is helpful to clarify the difference between a limitation of the exercise of the right, although an extremely intense one, and the sharp disavowal of an interest’s relevance.

Briefly, we can define a right as a single Hohfeldian relation or a cluster of relations pooled together by their role in protecting or enhancing the holder’s interest. How the interest is identified, how broad it is considered to be, and what actually is necessary to protect it, are sometimes settled matters (mostly through regulation or adjudication) and sometimes issues open to debate and controversy.

In the following text I will refine further the interest theory, relying on the seminal work by Andrei Marmor. This, I argue, provides additional illumination on the choice between the absolute and the relative theory, to the advantage of the latter.

Marmor’s view is committed to the interest theory: interests justify the clusters of Hohfeldian relations that make up the right and they might change through time (clusters are dynamic).Footnote 67 Yet here comes the interesting variation, for Marmor criticises what he calls the ‘Newtonian’ conception of rights, namely the idea of rights as bodies in inertial movement that continue on their trajectory until another right cuts in. According to this view, the cluster-right is per se well defined and must be limited (and therefore balanced) only in the name of a competing right. However, and crucially, this assumption is misleading: rights are not only limited from the outside (by other rights), but also from ‘the inside’. The reason for these inner limits is simple: if A’s right is a cluster of Hohfeldian relations to serve A’s interest, then by definition it involves a series of burdens, especially duties, imposed on others. No burden is costless. Each imposes a potentially heavy toll on others, and we must necessarily balance A’s interest and others’ duties before recognising this right. We accept that the calculation is tolerable overall, considering the ‘gain’ that comes from preserving A’s interest and the ‘loss’ imposed on others. This sort of ‘preliminary balancing’ is a necessary step, not a contingent one, for the recognition of a right.Footnote 68 If we accept this characterisation of legal rights in general, then a particularly cogent argument against the possibility that the essence of a right is ever possibly left untouched inevitably follows.

It is possible to better understand what kind of argument this is by considering an alternative path. One might start from the fact that we know of cases in which fundamental rights conflict in such an intense and irreconcilable manner, that one of the two is inevitably infringed in the essence. This can happen both between rights of the same kind (intra-rights conflicts) and with different ones (inter-rights conflicts).Footnote 69 Famous conflicts, like the trolley problemFootnote 70 in ethics or constitutional dilemmas in law,Footnote 71 instantiate cases of this kind, in which no essence can be preserved. This suggests that de facto in some cases the enforcing of a fundamental right means the crushing of another. Thus, the essence of a right is in fact patently subject to balancing. But this is an argument a posteriori, based on the empirical observation that we have cases of this kind. The argument from preliminary balancing is more subtle and cogent, for it points out that balancing is not only verifiable in some cases, but conceptually necessary. It works a priori, because it relies on the concept of rights itself (or at least, on the most convincing account of rights available). The essence of a right is not exempt from balancing because the establishment of rights – by definition – entails a preliminary balancing.

How preliminary balancing happens is not easy to assess. It seems reasonable to think that the doctrinal and ideological considerations that lie at the basis of controversies between rights also apply to the cost-benefit analysis necessary to the establishment of a single right.Footnote 72 One might perhaps imagine the identification of the cluster through the American notions of balancing and categorisation. The entrenchment of a rule in a category presupposes a previous balancing of the various involved interests, although this process of balancing is often hidden.Footnote 73 Similarly, the definition of the cluster-right assumes an often-impalpable process of adjustment of the Hohfeldian relations on the right-holders and on the duty-bearers.

Be that as it may, this analysis makes clear that the establishment of a right, including its inner core or essence, never happens in vacuo, but always in the light of a certain degree of balancing. This may not take the form of proportionality but remains inevitable: balancing is unavoidable even before conflicts with other rights arise. Preliminary balancing is not easy to recognise because it remains largely untheorised.Footnote 74 Yet, however hidden, it does exist.

To sum up, rights are clusters of Hohfeldian relations aimed at preserving or enhancing a certain interest of the right-holders. Some of these relations are more closely connected to the interest that constitutes the right, for either logical or practical reasons. Other relations are less significant to the protection of the right, so we may progressively move from the core to the periphery of the right.

The fact that this shift is scalar makes for a first critique against the absolute theory, for if the difference between the essence of a right and its perimeter cannot be sharp, then the idea that part of the right is subject to balancing through proportionality (the perimeter), while another part is not (the essence), becomes hard to sustain.

Second, the establishment of the content of the right, including its core, does not happen in vacuo, for all Hohfeldian relations that protect or enhance the right involve a burden to be placed on others. Thus, following Marmor, in establishing a right we must always face a sort of preliminary balancing. Consequently, denying that the essence of the right might be subject to balancing is unrealistic.

As a result of this long digression, the absolute theory turns out to be in trouble for conceptual reasons. There is no such thing as pure identification of an essence to be preserved from balancing, as opposed to a periphery to be possibly balanced. In identifying the core of a right, we always engage in balancing, although not necessarily in the form of a full-fledged proportionality test. This unavoidable step works as a sort of hidden phase in the proportionality assessment, the pre-theoretical identification of what is to be evaluated: rights’ abstract content and weight. This process is properly described by a weak version of the relative theory, one that involves only a cursory preliminary balancing when we purport to establish the core and the periphery of the right, while a full-fledged proportionality assessment only occurs later, in their application in practice.

Mapping the case law on Article 52(1)

The discussion on Article 52(1) has been theoretical so far: the point of the above discussion was to give a picture of the meaning of essence and of its relations with proportionality. Now I would like to consider empirically how the Court of Justice understands the notion of essence.

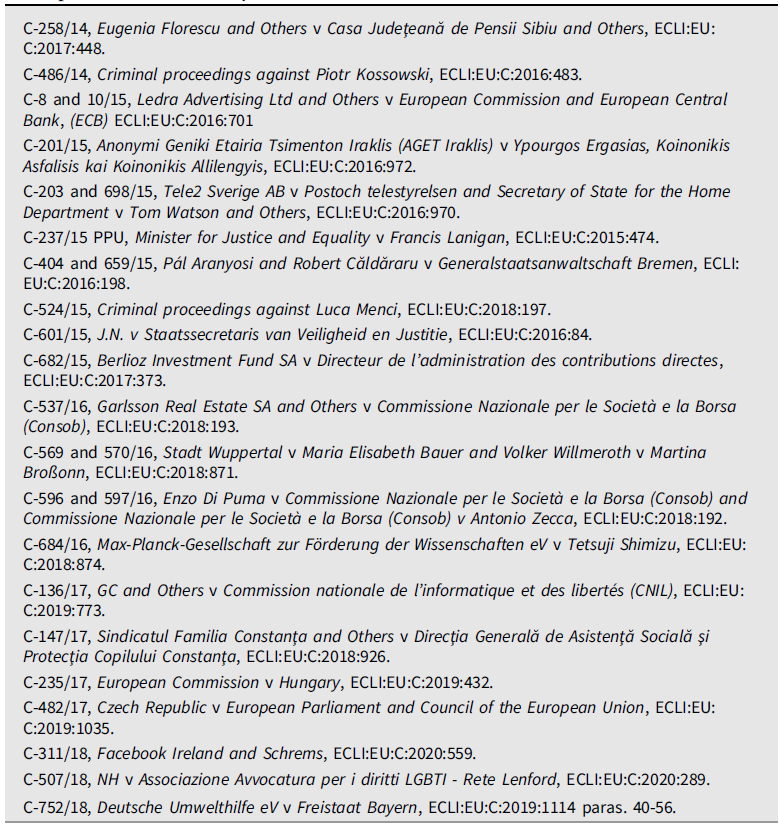

With this aim, a sample of 21 judgments decided after Schrems I was selected. As the task of mapping the entire case law, including the conclusions of the Advocates General, would be extremely long, I adopted three criteria to select a sample of cases from the CURIA database.Footnote 75 The considered cases are:

-

(i) decided by the Grand Chamber;

-

(ii) decided after Schrems I and before Schrems II; and

-

(iii) characterised by direct discussion of Article 52(1).

Since Schrems I was decided by the Grand Chamber, condition (i) ensures that the composition of the Court is authoritative enough for possible departure from it. Condition (ii) allows the focusing on a manageable series of cases by selecting a relatively brief yet informing period of time (from Schrems I in 2015 to Schrems II in 2020). Finally, condition (iii) restricts the inquiry to cases in which the Court explicitly quotes Article 52(1) in its reasoning.

Sample of cases selected by cumulative criteria (i) to (iii)

These criteria might partially distort the inquiry. Only looking at Grand Chamber cases could mean missing several possibly telling decisions. Similarly, the Court might be using the notion of essence even without explicitly mentioning Article 52(1), as it did in Schrems I itself. Finally, by not considering the Opinions by the Advocates General, one inevitably scrutinises only part of the case. Although these limits are undeniable, the criteria still allow for a reasoned selection of cases. In particular, since they only refer to a limited period of time (2015-2020), a specific deciding authority (the Grand Chamber), and a provision to interpret (Article 52), they do not involve any prior assessment of the cases’ content and, therefore, they limit some dangerous cherry picking.

I must also clarify that I take the Court as adhering to the absolute theory each time it attempts to establish what the essence of a right is (and whether it was harmed), and then moves to proportionality, as two logically separate phases. I take it as adhering to the relative theory when no such attempt is made and only proportionality is assessed. Only in the former case the Court might state that the essence was not infringed, although the measure is disproportionate, which is not possible under the relative theory. In the light of the previous analysis of rights, moreover, it should be clear that I do not consider adherence to the absolute theory as possibly successful: one simply cannot verify whether the core of the right was left untouched without any hidden balancing. However, what the Court is trying to do when adhering to the absolute theory is interesting per se and therefore it is worth separating the two groups of cases.

Starting from the distinction between the absolute and the relative theory, in most cases the Court remained faithful to the absolute theory. In 10 cases it tried to distinguish between interference with the essence of the right and proportionality. In four cases Article 52(1) was merely mentioned to rule out its applicability or recalled by the referring judge only: in these cases, neither interference with essence nor proportionality were assessed.Footnote 76 In seven cases the Court only carried out a proportionality assessment or asked the referring judge to do that (in this way shifting its position close to the relative theory).Footnote 77 In one of these, the Court distinguished between essence and proportionality, but then conflated essence on the rule of legitimacy of the proportionality test by arguing that a legitimate limitation of freedom of speech also safeguarded its essence. Thus, the Court adhered to the absolute theory in name only, while de facto upholding the relative one.Footnote 78

A special position belongs to the Schrems II judgment, which must really count as two cases in one. The Court did not quash the relevant provision (Decision 2016/1250) based on the alleged infringement of the essence of Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter, but in the light of proportionality (counting as a case of relative theory).Footnote 79 However, it also declared the invalidity of the Decision by looking at Article 47 of the Charter and recalling the reasoning of Schrems I, thus indirectly using the notion of essence (although it did not specify how the essence of Article 47 was affected).Footnote 80

When the absolute theory was embraced, the need to distinguish between interference with the core and mere proportionality assessment was grounded on two arguments. On the one hand, the literal argument: the text of Article 52(1) seems to ask for such distinction and is regularly recalled (all 10 cases). However, only in six is it the only ground for such distinction.Footnote 81 In the four remaining cases, the literal argument is also supported by an argument from precedents: the distinction between the two possible violations was based on previous cases in which the Court had interpreted the right in such a way.Footnote 82 The same is true of the already mentioned second part of the Schrems II decision. It is perhaps not surprising that sometimes the Court felt the need to reinforce its literal interpretation of Article 52(1) by relying on precedents. An empirical study on cases of constitutional importance decided by the Court shows that the literal argument is per se relatively uncommon.Footnote 83 Arguments from precedents, on the other hand, are extremely frequent and usually adopted by the Court to show consistency and predictability within its patterns of interpretation.Footnote 84 Moreover, it is worth noting that arguments from precedents, as the literal arguments, are based on authority: a certain interpretation is preferable because it was considered correct in the past or because the text itself demands it. Substantive assessment is missing. Such thin argumentation might be consistent with the conceptual difficulties highlighted in the last section about establishing the essence of a right in vacuo and separating it from any possible balancing.

As for the question of method, it is hard to find a structured and regular path. The most frequent argument made by the Court is that the limitations are exhaustively defined, so that the measure ‘does not call into question the very principle of the right’, which is quite close to the point made by Lenaerts in his article. Therefore, the idea seems to be that when a right’s exercise is simply limited and when limitations are sufficiently clear, then by definition the right is not completely effaced.

In one case the distinction between essence and proportionality was drawn, but whether essence had been infringed was not assessed, not even cursorily. It is probable that the core of the right was implicitly considered unharmed.Footnote 85

Mostly, however, the argument is explicit (six cases). In Florescu, the limitation to the right to pension is exceptional, temporary, and limited to well-defined circumstances, so that the ‘very principle of the right to a pension’ is not called into question.Footnote 86 In AGET Iraklis, the freedom to effect collective redundancies must be notified to national authorities, which, in turn, have specific powers of review and veto. This condition regulates but does not rule out the possibility of collective redundancies and therefore does not affect the essence of the freedom to conduct a business.Footnote 87 It is worth noting that the Court recalls a contrario a previous decision in which the substance of the right was entirely compromised,Footnote 88 for undertakings were entirely unable to participate in the collective bargaining body called upon to decide collective agreements. In Tele2 Sverige AB, an extremely wide amount of personal data is collected, yet the temporary character of the data retention and the scrutiny by an independent authority preserve the essence of the right.Footnote 89

In Menci and Garlsson, the right to ne bis in idem enshrined in Article 50 of the Charter is not compromised in its essence: the possibility of duplicating criminal and administrative proceedings and penalties is allowed only under well-specified conditions.Footnote 90 In J.N., the right to liberty is only limited, not interfered with in its essence: the possibility of detaining applicants for international protection is only allowed in exceptional circumstances, and must be based on individual conduct.Footnote 91 In Sindicatul Familia Constanta, the worker (a foster parent) had a right to free time that was limited, by subjecting it to an authorisation from the employer, in order to guarantee the interests of the child.Footnote 92 As a result, in none of these cases was the notion of essence used to quash an act within secondary EU law or to disapply national legislation.

Interestingly, however, in two cases (Bauer and Max Planck) the Court stated that it is part of the essence of the right to free time of workers that they might either enjoy paid annual leave or that, when this turns out to be impossible, they shall receive adequate compensation.Footnote 93 Consequently, the Court suggested the disapplication of national provisions preventing the compensation from being received (respectively, by the workers’ heirs after their death and by the worker himself at the end of the contract), for this would have otherwise meant an infringement of the core of the right. Thus, although there was no declaration of invalidity as in Schrems I or II, but mere disapplication of national law, still the Court used the notion of essence to preserve a fundamental right and did not establish it through proportionality. What is interesting is that in the already mentioned Sindicatul Familia Constanta the very same fundamental right, to a sufficient amount of free time for workers, was interpreted in a different manner. In all three cases the right is ultimately grounded in Article 31(2) of the Charter. Yet, the dependence of the right to paid leave on the employer’s authorisation or support, inacceptable in Max Planck,Footnote 94 was legal in Sindicatul.Footnote 95 The same event in one case preserves and in the others infringes the essence of the right: how can this be? It is likely that the riddle can be solved in the light of the interest theory set out in the previous section. The reason for tolerating a pretty large limitation in Sindicatul, but not in Bauer and Max Planck, lies in the countervailing interest. Specifically, the worker’s duty in Sindicatul, acting as a foster parent, is decisive. The need for continuous care for the child is an instantiation of another fundamental right recognised in the Charter (Article 24). This interest is so weighty as to make a severe limitation of the foster parent’s free time acceptable. When, as in Max Planck, the countervailing right is a mere economic interest of the employer, the balance shifts. This exemplifies rather well what Marmor’s remarks explain: when establishing the core and the periphery of rights, we never do that in vacuo. Rights involve duties on others and, depending on the countervailing interests, the untouchable core varies too. Whether this preliminary balancing is performed through a full-fledged proportionality assessment is a different issue. It is probably wiser to point out, again, that a weak version of the relative theory – one that only requires some informal preliminary balancing – is correct. Yet, the difficulties in establishing the content of a right (core and periphery) in vacuo are hard to overcome, both in theory and in practice.

Conclusion

The question of the meaning of Article 52(1) is crucial to our understanding of EU law. This debate might seem a rather technical discussion on the interpretation of a single provision of the Charter, but beyond the technicalities it concerns deep questions of political morality Those taking the side of the absolute theory do it for commendable reasons, i.e. trying to preserve the values of the Union through Article 52(1). If we consider the broader context of the rule of law crisis in the EU, this becomes even more understandable.Footnote 96

Despite this remarkable perspective, it is reasonable to doubt that the absolute theory is theoretically and empirically sound. The idea that we can establish the essence of a right in vacuo is deeply problematic. The interest theory of right entails that the core-periphery distinction, although meaningful, is not sharp, but scalar. It can only amount to a relatively fuzzy and relative distinction: drawing a firm line, as the absolute theory requires, is impossible. Moreover, the underlying ‘Newtonian’ conception of rights is misleading: when establishing a right, we necessarily impose burdens on others. When evaluating whether this imposition is acceptable overall, we must balance and relativise, including when setting the (blurred) core of the right. Relativisation, although sometimes less well-reasoned than we would like it to be, is also inevitable.

Finally, the analysis of the sample of cases suggests that, when adopting the absolute theory, the Court has not developed a full-fledged method to establish the essence of a right; instead it has relied on an intuitive understanding. Moreover, as the comparison between Bauer, Max Planck, and Sindicatul shows, when identifying the content of the right, the Court confirmed the necessity of preliminary balancing by evaluating a quite similar content as either untouchable or negotiable depending on the competing interest.

The debate on Article 52(1) really is a debate on the core of EU law, one in which the deepest ethical commitments of commentators show themselves. However, these cannot prevail over descriptive accuracy if scholarship has to fulfil its main function. Moreover, the fear of balancing, and of its potential to revitalise values, might turn out to be misplaced: balancing does not necessarily mean immoral reasoning. Much depends on how the reasoning is structured and how careful the deliberation on the involved interests is. Instead of looking for a comfortable but unrealistic ‘view from nowhere’, perhaps we should try to give the best argument we can when dealing with the most delicate issues in adjudication on rights.