Introduction

Deliberative democracy has taken a constitutional turn,Footnote 1 with many advocating the integration of deliberative mini-publics into the constitutional amendment process.Footnote 2 Ireland has been at the forefront of these developments, attracting global attention with referendums on same-sex marriage and abortion that were held and passed after recommendations were made by a representative cross-section of citizens deliberating under favourable conditions before making recommendations for reform.Footnote 3 David Farrell et al. have characterised Ireland as ‘a world leader in the linking of deliberative democracy (mini-publics) and direct democracy (referendums)’.Footnote 4 The Irish experience has been cited in support of strong claims for the contribution that deliberative mini-publics can make to processes of constitutional amendment and democratic systems more broadly.Footnote 5 For example, based on the same-sex marriage and abortion referendums, John Parkinson argues that the combination of deliberative mini-publics and referendums can make a critical contribution to deliberative democracies.Footnote 6 Jane Suiter and Theresa Reidy argue that deliberative mini-publics at the pre-referendum stage help to secure better alignment between votes and voter preferences.Footnote 7 Focusing on the abortion referendum, Johan Elkink et al. contend that voters were more likely to vote in favour of constitutional change where they were aware of the deliberative mini-public.Footnote 8 They argue that the pre-initiation use of a deliberative mini-public enhanced the ‘information environment’ in which the subsequent referendum took place, influenced the strong vote in favour of reform, and potentially impacted voter turnout.Footnote 9

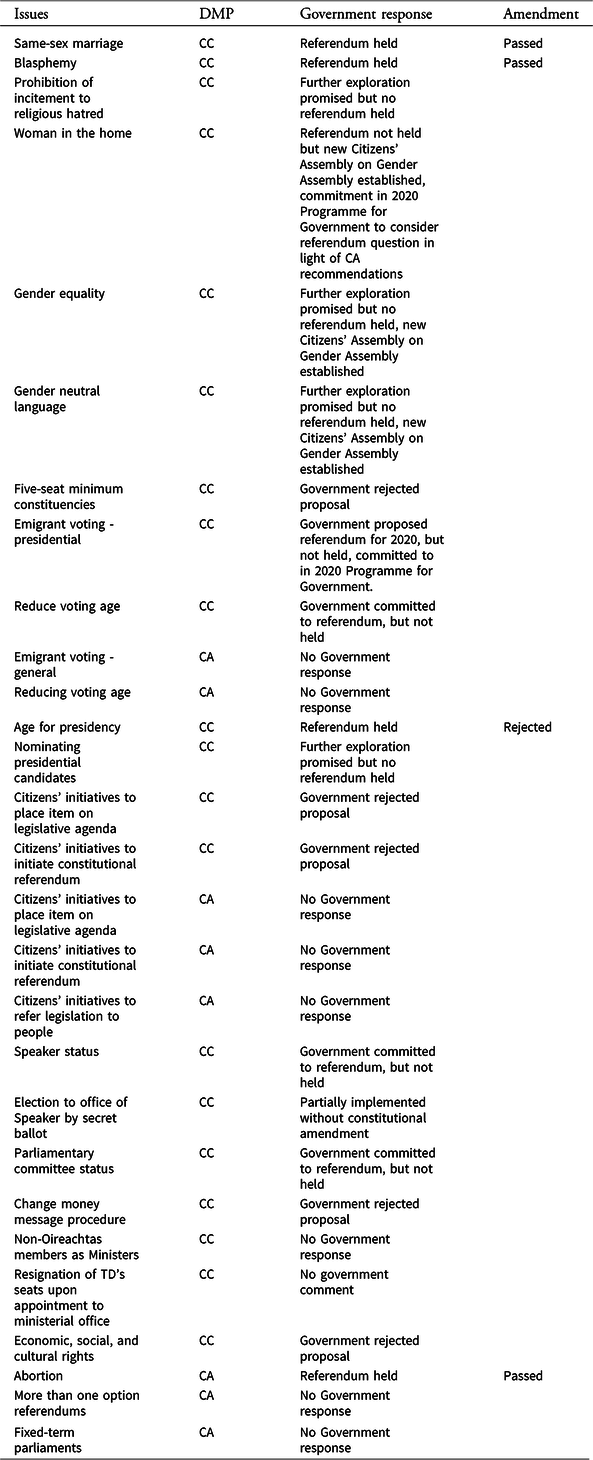

Little more than cursory reference has been made, however, to the recommendations of Ireland’s deliberative mini-publics that did not gain traction in the constitutional amendment process. This comparative blind-spot has the potential to undermine some of the stronger claims for deliberative mini-publics derived from the ‘success stories’ of abortion and same-sex marriage. It also has the potential to discourage exploration by deliberative democracy and constitutional scholars of the effects of deliberative mini-publics on constitutional amendment processes where the recommendations of such bodies are not implemented. To address this blind-spot, we present the first comprehensive account of the political take-up of recommendations for constitutional amendment made by Ireland’s deliberative mini-publics. Of 28 discrete recommendations, only three resulted in constitutional amendment.

The best explanation for this record, we suggest, lies in how constitutional amendment responds to the interests and concerns of legislative majorities. In other work, we have argued that constitutional amendment procedures involve the consensus democracy of will formation rather than electoral competition. The vast majority of state constitutions conform to a single model of constitutional amendment: legislative-majority-plus.Footnote 10 Constitutional amendment requires the agreement of the legislative majority and at least one other constitutional actor, be that the people in a referendum, federal sub-units, successive legislatures, or a legislative supermajority. These procedures prioritise the consensus democracy of public will formation at the expense of the representative democracy of electoral competition. The requirement that the legislative majority support constitutional amendment, however, means that constitutional amendment is not a deus ex machina that materialises to rescue or reboot ordinary constitutional processes. Instead, the legislative majority whose political power is determined by the constitution is also a component part of the constitutional amender that can reduce or increase the powers of current and future legislative majorities. Amendment requires the legislative majority to persuade the other relevant constitutional actors that it and future legislative majorities should be afforded more or less power.Footnote 11 Consistent with this account, we see that the recommendations of Ireland’s deliberative mini-publics led to constitutional amendment where: (a) they responded to real points of political disagreement where there was already some public interest in constitutional change; and (b) they did not contradict deep-seated commitments of legislative majorities. This does not rule out the possibility that deliberative mini-publics – rather than underlying political trends – played a role in the success stories, but any such claim requires careful work to isolate the contribution of the deliberative mini-public.Footnote 12 More subtly, it also suggests a reappraisal of what qualifies as success: in some instances, the contribution of a deliberative mini-public was to highlight the potential divergence of public and elite opinion on constitutional reform.

The first part of this article explains the Irish amendment process and its experimentation with deliberative mini-publics. The paper next outlines every recommendation for reform issued by Ireland’s deliberative mini-publics and the traction it gained in the formal amendment process. Based on that experience, the article analyses the factors that may indicate the likelihood of deliberative mini-publics having a direct impact on constitutional amendment. It also considers the potential impacts of deliberative mini-publics where their recommendations are not advanced through ordinary political processes, in particular in enhancing political accountability in respect of constitutional change. Following that, it raises a cautionary note about the generalisability of the Irish experience, before concluding.

The Irish amendment process and its ‘deliberative turn’

The Irish Constitution conforms to the legislative-majority-plus paradigm. An amendment proposal must be passed by both Houses of the Oireachtas (Parliament) before being put to the people by way of referendum, where a simple majority of those voting on the day is required for it to pass.Footnote 13 Ireland applies the Westminster model of responsible government for relations between parliament and executive. As a result, the Government typically – although not always – holds a legislative majority,Footnote 14 requiring only the additional approval of the people at referendum to approve constitutional amendments. The Constitution has been amended 32 times, 22 of these in the past three decades. Eight amendments allowed the State to ratify international treaties, mostly relating to the EU. Ten amendments made minor changes to the structure of government; 14 amendments made changes to social and moral values. Popular support for referendum proposals is far from guaranteed, 11 having been rejected at referendum. In particular, the people have repeatedly rejected proposals that would have enhanced the power of legislative majorities: changing the electoral system to first-past-the-post (1959 and 1968), granting a power of inquiry to parliamentary committees (2011), and abolishing the Seanad (upper House) (2013). Indeed, no amendment has ever been approved at referendum that was opposed by the principal opposition party.Footnote 15

Since 2012, Ireland has deployed deliberative mini-publics to consider issues of constitutional reform prior to the constitutionally stipulated process outlined above. The Constitutional Convention (2012-14) and the Citizens’ Assembly (2016-18) made 28 recommendations that would have required constitutional amendment, which are considered in the following section.Footnote 16 Both bodies were established in response to complex government formation negotiations. In February 2011, a new Government was elected consisting of a coalition between the centre-right Fine Gael and centre-left Labour Party. To manage their differing constitutional reform agendas, in particular in respect of same-sex marriage, the parties agreed to establish a Constitutional Convention. The backdrop to the establishment of the Citizens’ Assembly in 2016 was the general election held that year. Fine Gael committed to establishing a Citizens’ Assembly to consider the abortion issue. This assisted in securing the support of non-party member of Dáil Éireann Katherine Zappone for the Fine Gael minority government after the election. The Independent Alliance (a group of non-party members of Dáil Éireann, upon whose support the minority government also relied) has been identified as the likely source of the fixed-term parliaments issue that was considered by the Assembly, suggesting that the establishment of the Assembly also assisted in securing their support.Footnote 17

Each deliberative mini-public had an independent chair and 99 members. The citizen-members were randomly selected to be representative of the population as a whole, but 33 members of the Convention were elected politicians. Each was established by a parliamentary resolution that prescribed a list of topics to address, although the Convention was empowered to initiate consideration of additional issues.Footnote 18 Each was required to report to Parliament on its recommendations, with the Government obliged to respond formally to the recommendations. The members met at weekends and were presented with expert information, which they analysed through question and answer sessions and round-table deliberations before formulating ballot papers and voting on proposals. Most constitutional issues were dealt with over a single weekend, but the Convention devoted two weekends to electoral reform and the Assembly devoted five weekends to the issue of abortion. Expert groups provided support and advice to each deliberative mini-public, although the structure of these groups varied. Public submissions were sought in respect of each issue under consideration.

In the following section, we consider the recommendations for constitutional amendment that emerged from both deliberative processes, highlighting how they interacted with and framed the parameters of other constitutional processes.Footnote 19 We pay particular attention to the reception of the recommendations by the political actors in the amendment process.

Constitutional amendment recommendations from Ireland’s deliberative mini-publics

Same-sex marriage

The High Court had held in 2006 that the Constitution did not protect a right to same-sex marriage.Footnote 20 The Civil Partnership Act 2010 then allowed same-sex couples to form recognised civil partnerships, but not marriages. It appears that the Attorney General advised the 2008-2011 Government that a constitutional amendment would be required; this position – whether correct or incorrect – became accepted by political actors as imposing constraints on their legislative freedom of action.Footnote 21 The coalition Government elected in 2011 consisted of a centre-left party that had committed to introducing same-sex marriage, and a centre-right party that had not. Avoiding this contentious issue, the Government established the Constitutional Convention, with same-sex marriage as its most high-profile issue.

The Convention recommended by a vote of 79% that the Constitution should be amended to allow for same-sex marriage and that, if carried, laws should be enacted making further changes in respect of the parentage, guardianship and upbringing of children. In its response to the recommendations, the Government undertook to hold a referendum on the issue in mid-2015. In May 2015, 62% of those voting approved the amendment: ‘Marriage may be contracted in accordance with law by two persons without distinction as to their sex’. The parliament then passed the Marriage Equality Act 2015.Footnote 22

Blasphemy

Article 40.6.1.i of the Constitution declared that the ‘publication or utterance of blasphemous, seditious, or indecent matter’ was an offence, but did not define blasphemy. In Corway v Independent Newspapers (Ireland) Ltd, the Supreme Court prohibited a private prosecution for blasphemy on the ground that a statutory definition of blasphemy was necessary before such a prosecution could be initiated.Footnote 23 Section 36 of the Defamation Act 2009 provided that statutory definition, apparently following advice from the Attorney General that the parliament was constitutionally obliged to do so.Footnote 24 Political actors, including the Minister for Justice who sponsored that legislation, indicated their preference to amend the Constitution to remove the requirement for an offence of blasphemy.Footnote 25 61% of the Convention’s members recommended that the offence of blasphemy should not be kept as it was; 53% recommended it be replaced with a new general provision that would criminalise incitement to religious hatred; 38% voted to remove the offence of blasphemy altogether. In October 2014, the Government undertook to hold a referendum on removing the offence, indicating that the Convention’s secondary recommendation required ‘more detailed and other legal consideration’. In October 2018, by a vote of 65% in favour, the people approved a referendum simply removing the word ‘blasphemous’ from Article 40.6.1°.

Economic, social and cultural rights

The Supreme Court determined in 2001 that socio-economic rights, even if explicitly protected by the Constitution, cannot be enforced by way of mandatory orders.Footnote 26 That conclusion was based not on any one provision of the Constitution but rather on the view that such a role for judges would be inconsistent with the entire scheme of separation of powers established by the Constitution.Footnote 27 Some Supreme Court judges have also suggested for similar reasons that it would be inappropriate for the courts ever to recognise implicit socioeconomic rights.Footnote 28 The Constitutional Convention used its power to consider ‘any additional issues’ to address the question of constitutional protection for economic, social, and cultural rights. 85% of the Convention recommended amendment to strengthen the protection of economic, social, and cultural rights, although a sizeable minority of 43% recommended that the question of reform should be referred elsewhere for further consideration of its implications. 59% supported the insertion of a provision that the State should progressively realise economic, social, and cultural rights, subject to maximum available resources, with that duty cognisable by the courts. The Convention recommended that rights to housing, social security, essential health care, the rights of people with disabilities, linguistic and cultural rights, and rights covered in the International Covenant on economic, social, and cultural rights should be specifically included in the Constitution.

The Government’s formal response to the recommendations was sceptical, raising concerns over the costs and, echoing the reasoning of the Supreme Court, the allocation of power to the courts to determine the distribution of resources. The Government proposed that the report be referred to a parliamentary committee. Although this formally occurred in October 2017, no hearings have been held. In 2018, a non-party MP introduced the Thirty-Seventh Amendment of the Constitution (Economic, Social and Cultural Rights) Bill that would have imposed a justiciable duty on the State to progressively realise the rights protected by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. However, this Bill did not receive its second reading before the dissolution of that Oireachtas in 2020.

The ability of the Constitutional Convention, unlike the Citizens’ Assembly, to consider issues additional to those prescribed by parliament allowed it to propose reform that was not on the agenda of the legislative majority. Despite not being accepted by the legislative majority, the recommendations of the Convention show how a deliberative mini-public can plot a pathway to a radically different constitutional future. Constitutional interpretations of the courts – even interpretations of the overarching constitutional structure – can be disputed and alternative interpretations put forward, even where the views of the judiciary and politicians are aligned. The existence of the Convention’s report, and the Government’s obligation to respond to it, provided those advocating for amendment with an additional argument for change that is embedded in the formal institutional structures for amendment and that takes account of the history of constitutional interpretation on the issue.Footnote 29

The role of women in the home and gender equality

Article 41.2 of the Constitution recognises the value to the State of woman’s life within the home, requiring the State to endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home. The provision has played little role in judicial decision-making. It was judicially cited in relation to proper provision in the context of judicial separation or divorce,Footnote 30 and was relied upon to uphold social welfare legislation that discriminated in favour of women.Footnote 31 The courts have refused to grant an expansionary interpretation to the provision, rejecting the claim that it required a right to a share in matrimonial property,Footnote 32 as well as the claim that it allowed a mother to sue the state arising out of the unconstitutional treatment of her profoundly autistic son.Footnote 33 In other words, although clearly out of line with contemporary values, Article 41.2 has little or no practical effect.

Previous expert-led constitutional reviews recommended amendment of Article 41.2 to adopt gender neutral language to recognise the important role of carers.Footnote 34 The Constitutional Convention was charged with considering ‘amending the clause on the role of women in the home and encouraging greater participation of women in public life; and increasing participation of women in politics.’ 88% of members voted that the provision should be amended in some way, 88% then preferring amendment to simple deletion. In terms of modification, 98% supported making it gender neutral; 62% supported including carers outside the home. There were differing views on how strong an obligation to impose on the State.Footnote 35 Relatedly, as a result of its deliberation on the role of women in public life and politics, the Convention recommended amending the Constitution to include an explicit provision on gender equality (62% in favour), and to include gender-neutral language throughout its text (89% in favour).

In response, the Government accepted the need to amend Article 41.2 and committed to explore the most appropriate wording, including examining the constitutional recognition of carers. It further undertook to review the Convention’s proposals for an explicit constitutional provision on gender equality and for gender neutral language. In 2016, a new Government committed to holding a referendum on Article 41.2. It established a Department of Justice taskforce to identify a preferred proposal for change, taking account of previous recommendations and the need to avoid unforeseen additional costs to the exchequer. The taskforce rejected outright deletion but recommended two alternatives: a gender neutral recognition of care work in the home, with State support ‘as may be determined by law’; or a symbolic recognition of the value of home and family life in Article 41.2 with a commitment to support carers placed in the judicially non-enforceable Article 45.Footnote 36 On gender equality and gender neutral language, it recommended further consideration by experts in the Department of Justice and the Attorney General.

Notwithstanding these recommendations, the Government in 2018 proposed simple deletion of Article 41.2. The Government did not control a legislative majority, however, and the relevant parliamentary committee decided to conduct pre-legislative scrutiny of the proposal, disrupting the Government’s plan to hold the referendum on the same day as the blasphemy referendum.Footnote 37 The pre-legislative scrutiny report recommended either gender neutral language to recognise the support that home and family life gives to society or a new process of public engagement about the options for reform, specifically referencing the model of the Citizens’ Assembly.Footnote 38 Non-governmental organisations argued for constitutional recognition of the value of caring to society.Footnote 39 The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission advocated an amendment supporting the work of carers in gender neutral terms.Footnote 40 Against the backdrop of these political developments, in July 2019, the parliament established a new Citizens’ Assembly to carry out a wider exploration of gender equality.Footnote 41 It began its work in January 2020, with its Chair confirming in her opening address that it would consider the issue of women in the home.Footnote 42 The new Government elected in June 2020 has undertaken to consider or hold a referendum on Article 41.2 in light of the Assembly’s recommendations.Footnote 43

The political treatment of the Convention’s recommendations in relation to Article 41.2 suggests that, while deliberative mini-publics can plot pathways to alternative constitutional futures, it is difficult to garner political support for options for which there was not previously a political commitment, particularly if this involves the insertion of untested constitutional text the interpretation of which is not easily predicted. Nonetheless, even if the recommendation did not lead to constitutional amendment, the deliberative mini-public provided a platform for alternative views on the appropriate constitutional approach to contested issues, prompting constitutional actors to defend their position explicitly, thereby enhancing public debate.

Electoral reform

Both the Constitutional Convention and the Citizens’ Assembly made recommendations for changes to voting in elections and referendums that would necessitate constitutional amendment.

The Convention, although having voted to explore alternatives to the existing proportional representation-single transferable vote electoral system, rejected (79%) the alternative electoral system that was considered (a mixed member proportional system). In terms of adjustments to the existing system, 86% voted in favour of a move to a five-seat minimum constituency size from the existing three-seat minimum set out in the Constitution.Footnote 44 In its response, the Government accepted the recommendation to retain the current electoral system. It rejected the five-seat minimum recommendation, expressing the view that the practice of having a range of three, four, and five-seat constituencies had served the people well by achieving ‘appropriate balance in representation across the country.’Footnote 45

52% of the Convention voted to reduce the voting age to either 17 (39%) or 16 (41%). In 2013, the Government undertook to hold a referendum to reduce the voting age to 16 before the end of 2015.Footnote 46 However, no such referendum was initiated.Footnote 47 The Convention recommended (78%) that citizens resident outside the State should have the right to vote in presidential elections.Footnote 48 36% favoured extending that right to all citizens resident outside the State, while 26% wanted a prior residency requirement. The time-limit that gained most support was a restriction to five years residence outside the State. In 2016, the Government highlighted practical issues in relation to Northern Ireland, the registration of voters and voting procedures.Footnote 49 A referendum was planned for May 2019 and was then postponed to October 2019 but not held.Footnote 50 An amendment Bill was published in September 2019, but this lapsed with the general election in February 2020.Footnote 51 The Government elected in June 2020 has undertaken to hold a referendum on this issue,Footnote 52 but no new amendment Bill has been published, nor has a date been proposed for a referendum.

The Citizens’ Assembly also recommended as part of its work on referendums that the voting age should be reduced to 16 (80%) and that voting should be allowed by otherwise eligible voters who are resident outside the state for no more than five years (77%). The Government has not yet responded to these recommendations.

The presidency

The parliamentary resolution establishing the Constitutional Convention required it to consider reducing the Presidential term of office to five years. The Convention rejected this proposal (57%) but of its own motion recommended (50% to 47%) reducing the age of eligibility for candidacy from 35 to 21. In its response, the Government undertook to propose an amendment reducing the age of eligibility to 21.Footnote 53 Held on the same day as the same-sex marriage referendum, 73% voted against the proposal.

The Convention also recommended (94%) giving citizens a role in the nomination of presidential candidates. In response, the Government stated that citizens had sufficient influence through the ordinary representative channels of local and national government. It indicated that it had asked the relevant Oireachtas committee to do further work on the issue of citizen input into the nomination process, noting that the Convention had not set out its view on practicable changes to the existing process.Footnote 54 There has been no subsequent change in the nomination process.

Citizens’ initiatives

The Constitutional Convention chose to consider reforms to how Dáil Éireann (the Lower House) does its work. In this context, 83% favoured the introduction of citizens’ initiatives, 80% approved their use for setting the legislative agenda, while 78% thought they should trigger constitutional referendums. The Citizens’ Assembly also recommended the introduction of citizen initiatives – for constitutional referendums (69%), for putting a legislative change to the people (69%), and for putting an item on the legislative agenda (83%). The Government rejected the Convention’s recommendations on citizens’ initiatives, pointing to the relative frequency of referendums in Ireland and the possibility that citizens could present petitions under the existing system.Footnote 55 It has not responded to the Assembly’s recommendations.

Parliamentary reform

The Convention (88%) recommended amending the Constitution to recognise the office of the Speaker of the Lower House. A further 88% recommended that elections to that office should be held by secret ballot, which the Convention indicated could require an amendment. 76% favoured an express constitutional reference to parliamentary committees. 53% voted in favour of amending Article 17.2 of the Constitution that requires Government approval for any legislation that has a public expenditure implication. 55% of the members of the Convention voted in favour of allowing non-members of the Houses of the Oireachtas to be appointed as Ministers, while 59% favoured requiring members of the Lower House to resign their seats upon appointment to ministerial office.

In its response to these recommendations, the Government accepted in principle the recommendation to amend the Constitution to give the office of House Speaker constitutional status but has not moved to initiate a referendum on the issue. The Standing Orders of the Dáil (Lower House) were amended to provide for a secret ballot for the election of the Speaker; but the candidate chosen in this way is then put to the House in an open ballot for confirmation, observing the general constitutional rules on votes in the House.Footnote 56 The Government undertook to implement the recommendation for a constitutional reference to the Oireachtas committees but did not set out a time-line for a referendum. No such referendum has been held, and there is no indication that one is being planned. The Government rejected the possibility of changing Article 17.2 or the associated standing orders. It noted but did not express a view on the recommendation that non-members be eligible for appointment to ministerial office, and did not comment on the recommendation in relation to resignations.

Abortion

The Constitution was amended in 1983 to provide explicit protection for the right to life of the unborn in Article 40.3.3°. Two further amendments were passed in 1992 to ensure that this did not restrict the freedom of women to travel to secure abortions or to receive information about abortion services lawfully available in other countries.Footnote 57 The 2016 general election resulted in a minority government led by a centre-right party that had made a manifesto commitment to establish a Citizens’ Assembly to review the 8th Amendment.Footnote 58 The Assembly first decided by a majority of 79 votes to 12 that Article 40.3.3° should not be retained in full. They then, by a majority of 50 to 39, recommended that Article 40.3.3° should be replaced rather than repealed. In the third ballot, they decided, by a majority of 51 to 38, that Article 40.3.3° should be replaced with a constitutional provision that explicitly authorised the Oireachtas to legislate to address termination of pregnancy, any rights of the unborn, and any rights of the woman. In the final ballot, the Assembly made a series of recommendations for legislation that would significantly liberalise the circumstances in which abortion services were lawfully available in Ireland.

The Assembly’s recommendations were considered by a parliamentary committee that recommended that Article 40.3.3° should be simply repealed and that, subsequent to repeal (if passed), the Oireachtas should legislate to liberalise abortion law in a manner similar to – but with some important differences from – that proposed by the Assembly. The Attorney General subsequently advised the Government, however, that it would be appropriate to clarify the competence of the Oireachtas to legislate in this domain, taking an approach closer to that recommended by the Assembly than that recommended by the parliamentary committee. In the referendum in May 2018, 66% voted in favour of a new Article 40.3.3°: ‘Provision may be made by law for the regulation of termination of pregnancy’. In December 2018, the parliament enacted the Health (Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy) Bill 2018, broadly consistent with a draft scheme published by the Government before the referendum campaign and largely reflecting the recommendations made by the Assembly.

Several commentators have argued that the Citizens’ Assembly on abortion, while not changing public opinion, did shift the attitudes of legislators whose support was needed for constitutional amendment.Footnote 59 In other work, we argue that the Assembly had a greater impact than this. Based on a detailed analysis of the Assembly’s work, opinion polls, and political statements, we conclude that the Assembly may have assisted a consensus to evolve on the form of constitutional amendment, as well as placing on the political agenda the liberalisation of abortion on request.Footnote 60 Large majorities were opposed to such a change when the Assembly began its work but a large majority implicitly approved it at a referendum 18 months later. Notably, however, our argument is that the Assembly’s influence concerned the form of constitutional change and the scope of resulting legislative liberalisation – not the basic impetus for reform.

Referendums and fixed-term parliaments

We have already considered above the recommendations made by the Citizens’ Assembly in respect of voting and citizens’ initiatives. However, the Assembly also recommended (64 votes in favour, 20 against) to allow more than one option on a ballot paper in a constitutional referendum. In respect of fixed-term parliaments, in a close vote, a majority of 36 citizens voted to change the constitutional provision that effectively gives the Taoiseach an absolute discretion to dissolve the Dáil unless she has ceased to retain the support of the majority of the Dáil. 35 citizens rejected any such change. A majority of 36 votes were cast in favour of a four-year fixed parliamentary term, with 27 votes for a five-year term, and five voters preferring not to state an opinion on length of term. The Assembly recommended (by 63 votes to three, with five declining to express an opinion) allowing the legislature’s fixed term to be cut short subject to certain conditions: by 39 votes to 20, the Assembly supported a Cabinet-approval requirement for an early election; by a slimmer majority of 29 votes to 27, it recommended that a legislative majority could cut the term short; by 40 votes to 17, it recommended that a super-majority (e.g. two-thirds of representatives in the Dáil) could cut the term short; and by 46 votes to nine, the Assembly voted for the approval of the President as a requirement for curtailing the fixed term. The Government has not responded to these recommendations.

The contribution of deliberative mini-publics to constitutional amendment

Although it is possible to establish deliberative mini-publics in opposition to the existing political system, the deliberative turn in constitutionalism has largely sought to integrate these mechanisms into existing frameworks. As Goodin and Dryzek put it, where deliberative mini-publics are used, ‘[t]he ordinary institutions of representative democracy generally remain sovereign, such that micro-deliberative mechanisms merely provide inputs into them’.Footnote 61 In the Irish context, the institutional requirements of a response by Government to all recommendations issued by deliberative mini-publics and a pre-commitment to parliamentary consideration through committees in respect of abortion and gender equality formally linked the deliberative mini-publics with ordinary constitutional processes.Footnote 62 Deliberative mini-publics will contribute to constitutional amendment if they facilitate the development of public will required by the constitutional amendment process, namely the agreement of the legislative majority and other constitutional actors on the desirability and appropriate form of constitutional amendment. They may also contribute to debate about the appropriate nature of such reform. Both of these roles for deliberative mini-publics are considered in this section in light of the Irish experience.

We saw above that constitutional amendments in Ireland can be divided into three categories: social and moral values, minor changes to governmental structures, ratification of international treaties. Deliberative mini-publics made 28 discrete recommendations for constitutional amendment, which are detailed in Table 1, covering changes to moral and social values and to governmental structures. The latter were minor, with the exception of the recommendations on citizens’ initiatives, which would have significantly altered the balance of constitutional power. There was no consideration of international treaties.

Table 1. Summary of the Political Response to the Constitutional Reform Recommendations of the Constitutional Convention (CC) and Citizens’ Assembly (CA)

Two factors appear to influence whether a recommendation will lead to an amendment and, in that way, have a direct effect on constitutional change: responsiveness to real points of political disagreement generating prior support for constitutional change; consistency with Government preferences.

First, the three implemented recommendations all concerned issues where pressure for constitutional reform was already manifest in ordinary constitutional processes. This pressure had arisen due to the work of non-governmental organisations and others who lobbied politicians and pursued litigation strategies. The courts’ constitutional interpretations crystallised the need for constitutional amendment if legal change was to be secured. The two non-implemented recommendations that still have some political traction can also be partially understood as responses to prior political disagreements, providing further support for this account: voting rights for emigrants and the recognition of care work. The treatment of emigrants resonates powerfully with the Irish public; the country has traditionally suffered from mass emigration, a phenomenon that recurred in the wake of the financial and economic crisis of 2008-2012. Civil society groups have campaigned for the constitutional recognition of care work.

In contrast, the 25 other recommendations were motivated by a desire to improve constitutional processes rather than as a response to any existing political disagreement.Footnote 63 Governments must invest political capital to win referendum campaigns; they are unlikely to do so if the referendum responds to neither a public demand nor a governance objective to which the Government is committed. Considered in this light, it is somewhat surprising that the presidential age proposal was put to a referendum. However, the fact that it was held on the same day as the same-sex marriage referendum reduced the need to invest political capital.Footnote 64 The resounding defeat for a trivial amendment confirms the view that deliberative mini-publics can assist in the formation of public will but are not devices that can generate public support for constitutional reform out of nowhere.

Second, recommendations were less likely to be implemented where they contravened Government objectives. In this regard, there are three interrelated dimensions: wariness of new constitutional text; aversion to new spending commitments; and a preference for amendments that enhance rather than restrict the powers of legislative majorities. In the context of blasphemy and the role of women in the home, the Government preferred simple deletion to the inclusion of novel textual commitments. During the pre-legislative scrutiny of the proposal to delete the provision on women in the home, the Minister for Justice commented that the Government wished to avoid overly prescriptive provisions in the Constitution that might be interpreted in unpredictable ways.Footnote 65 Recommendations that might lead to financial obligations for the State have been rejected. This was the basis on which the Government rejected recommendations in relation to economic, social, and cultural rights, and was also a significant complicating factor in the Government’s response to recommendations about the role of women in the home and gender equality.Footnote 66 Recommendations that have gained political traction have tended to enhance rather than restrict the powers of legislative majorities. Although the recommendations of the Citizens’ Assembly on abortion were politically far-reaching, in constitutional terms they expanded the powers of legislative majorities. Similarly, the blasphemy amendment removed the obligation to legislate in respect of blasphemy. The same-sex marriage amendment effectively required the Oireachtas to enact legislation to amend the existing marriage code, but this was a discrete change that went no further than the basis on which the referendum campaign was fought. In contrast, citizens’ initiatives, recommended by both deliberative mini-publics but rejected by the Government, could dilute the power and influence of the legislative majority by establishing new methods of law-making and removing control of the constitutional amendment process from the legislative majority.

The importance of these two factors is consistent with our general account of the purpose of constitutional amendment procedures: democratic will formation through the consensus of the legislative majority and other constitutional actors. If a constitutional reform proposal does not already have some political traction, it is unlikely to appeal to the legislative majority. If the reform proposal contradicts deep political commitments of the legislative majority and/or constrains the power of the legislative majority, it is likely to be resisted by the legislative majority even if it has already acquired some political traction.

Together, these factors should also cause us to question any narratives that straightforwardly attribute the ‘success stories’ of abortion and same-sex marriage to the involvement of deliberative mini-publics. If constitutional amendments are likely to succeed where they already have political support and where they do not contradict deep political commitments of legislative majorities, it is difficult to specify the contribution that deliberative mini-publics may have made to the ‘success stories’ of abortion and same-sex marriage. As already noted, we suggest that the Citizens’ Assembly on abortion may have assisted a consensus to evolve on the form of constitutional amendment, as well as placing on the political agenda the liberalisation of abortion on request.Footnote 67 It is more difficult to pinpoint the influence of the deliberative mini-public’s recommendation on same-sex marriage. As noted above, the centre-left Labour party was committed to same-sex marriage before the Convention on the Constitution; the centre-right Fine Gael party only came to support the amendment proposal after the Convention. The referendum was held two years after the recommendation was made, allowing for a protracted public debate rooted in the Convention’s deliberations on the issue. It is difficult to assess, however, whether the Convention contributed to citizens and elected representatives changing their mind or just provided time for attitudes to evolve similarly to those in other liberal democracies at the same time.Footnote 68

Overall, our analysis of the political uptake of the recommendations of the Irish deliberative mini-publics suggests that deliberative mini-publics may facilitate the formation of public will – a consensus between the legislative majority and other constitutional actors – that is necessary for constitutional amendment to succeed. However, they do not of themselves generate the impetus for constitutional reform. Moreover, if they contradict deep-seated commitments of the legislative majority, they are still less likely to be successful. It may not be possible to know in advance, however, just how opposed the legislative majority is to constitutional change. Political representatives are at least sometimes responsive to changes in public opinion; deliberative mini-publics may play a role in informing legislators about how public opinion has changed.

Furthermore, our analysis suggests that deliberative mini-publics can help in plotting pathways to alternative constitutional futures. They can encourage and legitimise the consideration of constitutional developments foreclosed by both judicial and political actors, as illustrated in particular by the Irish experience of socioeconomic rights. In this case, the courts had enforced a strongly held – although strongly contestable – view about the appropriate role of courts in a constitutional democracy. By focusing on this issue, the Convention exposed a significant gap between the popular understanding of constitutional democracy and the dominant view in the judiciary. Such a gap in itself may threaten constitutional legitimacy.Footnote 69 Even though the Convention’s recommendations on this issue – and the related expansive recommendations on gender equality and blasphemy – did not lead to formal amendment, they showed how deliberative forums can enhance constitutional accountability. They required political actors to articulate and defend their views on what the Constitution should do or say on contentious issues. A similar function can be identified for the Convention and the Assembly in respect of electoral reform and fixed-term parliaments, where the take-up and response from Government was limited or non-existent. On the question of change or no change, and on the variety of options for constitutional change in respect of any issue, deliberative mini-publics can cast into sharp relief the political choices that are made by constitutional amenders and the role of judicial and non-judicial constitutional interpretations in shaping those choices.

Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson point out that representative democracies only require politicians to be accountable to their constituents – not to all those bound by their decisions.Footnote 70 We do not advocate deliberative mini-publics as an alternative to, or a short-cut around, representative democracy.Footnote 71 Nonetheless, the Irish experience suggests that deliberative mini-publics can allow politicians to be held accountable by the wider public by providing what Mark Warren terms ‘institutionalized opportunities for discursive challenge’.Footnote 72 They can render the political negotiations and trade-offs in constitutional amendment processes clearer, thereby enhancing the ability of the public to identify and critique if necessary elite understandings of the Constitution.

However, the number of citizens directly involved in deliberative mini-publics will usually be small. To be effective accountability mechanisms, they need to be accompanied by wide dissemination of their proceedings and must be accessible to the public through submissions processes. In addition, transparency, representativeness, and a meaningfully ‘citizen-led’ approach are important factors in assessing the effectiveness of deliberative mini-publics in contributing to public debate on constitutional reform.Footnote 73 Finally, the accountability function of deliberative mini-publics is limited where, as was largely the case in Ireland, politicians control the establishment, agenda, and resourcing of such bodies.Footnote 74 The ability of deliberative mini-publics to chart alternative constitutional futures and channel or spark contestation and debate about constitutional reform is significantly constrained, although not entirely removed, where the issues that they must consider are politically prescribed.

Deliberative mini-publics clearly have received sustained political support in Ireland, as reflected in the 2020 Programme for Government, which commits to holding four new citizens’ assemblies as well as a youth assembly.Footnote 75 However, the level of political commitment falls far short of institutionalisation.Footnote 76 The topics covered by deliberative mini-publics and their timing remain wholly driven by shifting political priorities. While governments have been required to respond to the recommendations of deliberative mini-publics, compliance with this accountability mechanism has been mixed, with responses outstanding on a number of issues.

There remains a further question about the extent to which Ireland’s experience of deliberative mini-publics is generalisable. The paradigm of legislative-majority-plus requires legislative majorities to seek the approval of other constitutional actors for constitutional amendment. In Ireland, this paradigm exists in substance and not just as a matter of form: the approval of other constitutional actors is not a foregone conclusion but is realistically attainable.Footnote 77 This obviously limits the generalisability of any lessons drawn: the Irish experience with deliberative mini-publics does not provide a template for countries where the legislative majority controls the other actor(s) whose consent is required for constitutional amendment, or where the consent of those other actors is not realistically attainable.Footnote 78 For that latter reason, it has little relevance to the amendment of the US Federal Constitution, although it might apply to the amendment of State constitutions.Footnote 79

Furthermore, Ireland’s approach to amendment may itself be a product of the political context: a small country with a relatively homogeneous population and a consensual political culture. These factors may have facilitated deliberation in the mini-publics themselves, assisted communication of their work and recommendations to the general public, and fostered public trust in the process. We cannot straightforwardly assume that, to the extent one considers the Irish process a success, this success would translate to large, diverse, and/or politically polarised societies. In particular, it is important not to overstate how contentious or surprising the outcomes of the same-sex marriage referendum or abortion referendum were. The Convention has been credited with securing ‘an outcome consistent with liberal value accommodation’ in the same-sex marriage referendum, notwithstanding the persistence of normative opposition to same-sex marriage.Footnote 80 Since the 1970s, however, both constitutional interpretation and constitutional amendment – reflecting changes in general society – had rendered the constitution considerably less religious and less conservative. The same-sex marriage and abortion referendums probably marked the culmination of that process with secular/progressive forces in the ascendant.Footnote 81 But they were not a constitutional revolution.

Conclusions

Our analysis of Ireland’s deliberative mini-publics has relevance for both scholars and advocates of a deliberative turn in constitutionalism. An exclusive focus on the ‘success stories’ of abortion and same-sex marriage may lead policy-makers to overestimate the utility of deliberative mini-publics in helping to build support for constitutional amendment. The clear lesson from Ireland’s experience is that deliberative mini-publics can assist in the formation of public will in response to reasonably weighty calls for constitutional reform. It seems difficult for deliberative mini-publics to build a political commitment to reform; however, even where the recommendations of deliberative mini-publics are not accepted, they can help to hold political actors accountable for their rejection of alternative constitutional futures. The simplest explanation for the variation in the direct impact of Irish deliberative mini-publics is that the three successes were already politically supported. If correct, this undermines the claim that even the successes were attributable to the deliberative mini-publics. In our view, such a conclusion is somewhat too blunt. As explored in more detail in our other work, there is evidence that public and elite opinion changed after the Citizens’ Assembly on abortion and a plausible narrative can be constructed that attributes to the Assembly a role in prompting and enabling those changes. Nonetheless, deliberative democracy advocates and practitioners must recognise that ultimately, no deliberative mini-public will achieve constitutional change without the consent of the legislative majority. This should not discourage experimentation with deliberative democracy in the constitutional context, but rather means that scholars of deliberative democracy who invoke the Irish experience should pay as much attention to its ‘failures’ as to its ‘successes’. Even if not accepted by legislative majorities, the recommendations of deliberative mini-publics play a useful role in suggesting alternative constitutional futures and holding both judicial and political actors accountable for their conceptions of the constitution and constitutional democracy more generally. However, that role is constrained where the timing and agenda of mini-publics is set by political elites.