Introduction

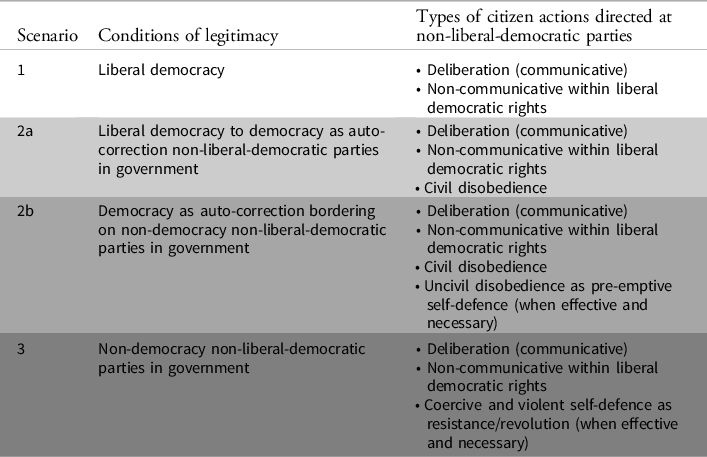

The literature on how democracy can defend itself mainly emphasises the role of public authorities and mainstream parties.Footnote 1 While it is widely recognised that the democratic identity and virtues of citizens are key in the protection and promotion of democracy,Footnote 2 so far few writers have focused on the active role of citizens in defending democracy against non-democratic actors.Footnote 3 This paper will remedy part of this by focusing on which actions citizens are justified in taking vis-à-vis non-liberal-democratic parties. The article combines literatures on militant democracy, political participation, ethical consumerism, (un-)civil disobedience and the ethics of self-defence to create a systematic overview of the nature of permissible citizen actions towards non-liberal-democratic parties under different conditions of political legitimacy. Figure 1 demonstrates the resulting ladder of escalation in the nature of citizen actions.

Figure 1. The escalation ladder of permissible citizens’ actions

The general argument behind the ladder of escalation is that depending on how threatened or how violated the preconditions for legitimate political rule are, citizens are permitted to exercise principled disobedience and even employ violence in defence of their liberal democratic institutions and rights if there is a well-supported presumption that this is necessary and effective. Given that the latter presumption often cannot be supported, the general argument is that citizens should stick to non-violent activities that are – or would be – in line with their liberal democratic rights. However, these activities include both communicative action aimed at persuasion and strategic actions aiming to pressure non-liberal-democratic parties out of the public domain and to undermine their ability to stay in and exercise power.

The focus is on non-liberal-democratic parties, which are parties defined by pursuing agendas that conflict with the principles of liberal democracy, including liberal democratic institutions and rights. The category ranges from extremist parties, which are explicitly against liberal democracy, to for example populist parties, which perceive themselves as true democrats but might be so in a problematic way.

Parties are important for the consolidation of democracy. When non-liberal-democratic parties become big and/or central for forming governing coalitions, they constitute a risk for liberal democracy and thus for the liberal democratic rights of citizens. They are therefore legitimate objects for citizens’ actions to protect democracy. Ultimately, what can be lost are the preconditions for making genuine democratic decisions and with those preconditions the basis for legitimate political rule.Footnote 4

Recent research shows that if parties characterised by ‘illiberal’ ideological views gain power by way of elections, they are very likely to turn democracies into autocracies.Footnote 5 The more illiberal views parties exhibit, the more likely they are to initiate steps towards autocratisation within the first year after the election. This suggests that citizens and other actors who are concerned with liberal democratic rights and institutions should see signs of illiberalism as early warnings and ought to act before illiberal parties gain power and certainly after they gain power.

It raises the question of what citizens can do to defend democracy, i.e. what forms of actions they can take. In Germany, antifascist groups try to make life as hard as possible for the party Alternative für Deutschland through inter alia vandalism and scare tactics, while the explicitly pacifist Sardines movement in Italy mobilises citizens against populist Lega by showing up in large numbers in city piazzas to listen to speeches, to sing and do coordinated dance moves. While the Sardines’ approach seems most appealing, is it clear that antifascist tactics are out of bounds? Neither in Germany nor in Italy have the conditions of legitimacy changed away from what we might broadly conceive as liberal democracy, and this is likely to influence our negative views of the permissibility of antifascist tactics. The question is whether this changes if we change context to, for example, Poland and Hungary, where it is unclear that the regimes are still based on liberal democratic principles. The independence of the judiciary has been undermined, governments exert problematic control over public and private media, and decision-making procedures fall short of standards of openness and fairness.Footnote 6

In order to create a general overview, this article investigates what the permissible types of actions are under different circumstances. It will look at three different scenarios:

In scenario 1, non-liberal-democratic parties are in opposition but have become an important factor in political life. They are not just a marginal phenomenon. Concrete examples could be modern day France and Germany.

In scenario 2, non-liberal-democratic parties have gained government power but have not (yet) changed the institutions of liberal democracy entirely and completely curtailed liberal democratic rights. The scenario entails some variation, with the preconditions for liberal democracy deteriorating towards a condition in which it is no longer a democracy. Poland and Hungary might be considered examples of different stages of that process.

In scenario 3, non-liberal-democratic parties hold government power and have changed institutions and rights away from the principles of liberal democracy. This resembles countries in which there is no real electoral competition, for example Belarus and Russia.

A key concern of the article regards the transition from scenario 2 to scenario 3 and how citizens can intervene to pre-empt it. The ban on the Turkish Refah party (1997) illustrates in part what is at stake. The Refah party was forced from office by the Turkish military (in June 1997) and subsequently banned from participating in elections for five years by the Turkish Constitutional Court, a decision which was later approved by the European Court on Human Rights on the basis that the party had the intention and potential to implement policies that were ‘dangerous for the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the [European Convention of Human Rights]’Footnote 7 and thus key liberal democratic rights. The case illustrates how actors concerned with protecting liberal democracy can intervene pre-emptively without relying on a democratic decision.Footnote 8

The paper proceeds as follows. First, it discusses the preconditions for legitimate rule and sets a pragmatic criterion for deciding when they are no longer present. It addresses the issue of how citizens can know when those preconditions are under threat of being undermined by non-liberal-democratic parties in order for them to act pre-emptively in defence of their liberal democratic rights. Second, it looks at permissible types of actions under different conditions of democratic legitimacy. This investigation relates to the different scenarios (1 to 3) set out above and draws on the literatures on civil disobedience and the ethics of self-defence. The third section specifies in a systematic manner the implications for each of the three scenarios. It is followed by the conclusion.

To clarify key concepts, the paper focuses on what citizens can do as citizens to protect liberal democracy against non-liberal-democratic parties in and out of government. ‘Citizens as citizens’ are here understood as individual citizens or loosely organised groups of ordinary citizens, social movements or non-governmental organisations. It does not include citizens in their capacity as legislators and/or as elected representatives. Citizens who are acting to protect and/or reestablish liberal democratic institutions and rights are referred to as ‘democratic citizens’.

The aim of the paper is to create a general overview of permissible citizen actions by combining different theories. In the interest of this ambition, the discussion of the individual theories stays at a general level, and the paper’s conclusions, which tend to be stated somewhat squarely, are therefore more conjectural and preliminary than definitive.

Liberal democracy, political legitimacy and when it is gone

There is a distinction between law as a set of norms that are generally followed and applied by citizens and public institutions on the one hand, and good laws consistent with moral principles on the other. Legal scholars have debated whether laws that violate moral principles should be considered law at all, and whether there is an obligation to adhere to them.Footnote 9 The literature on political obligation and legitimacy runs parallel to this discussion. The following draws on the democratic conception of political legitimacy.Footnote 10 A central premise for this conception is that political power is only fully legitimate, i.e. it has the unquestionable right to rule and thus coerce citizens to follow its laws and commands, when decisions are made using democratic procedures that grant all citizens equal political rights, and when they are secured the civic rights that facilitate both their equal private and public autonomy – or, in short, that political power is only legitimate when liberal democratic rights are secured.Footnote 11

The implication of the lack of legitimacy is that political power does not have the right to use coercion to make citizens follow rules and commands. Thereby the exercised coercion by (nominal) political authorities equals coercion or violence of one group of citizens against other citizens. As argued below, this means that the latter are justified in defending themselves against it.

That political power is legitimate does not necessarily mean that citizens are morally obligated to follow its rules and commands. The right to rule and the obligation to obey do not necessarily coincide.Footnote 12 Although there would be a presumption in favour of the notion that citizens should comply with democratic decisions, since non-compliance prima facie is equal to putting yourself above other citizens, there are certain circumstances in which deliberate non-compliance would be justified. Indeed, the basic argument in the literature on civil (and uncivil) disobedience is that the latter is justified when it can lead to a more perfect instantiation of the principles of justice and/or democracy; or, very crudely, the principles of liberal democracy.Footnote 13

The understanding of political legitimacy espoused here is relatively demanding or utopian. One objection would be that many people – scholars as well as citizens – have regarded other forms of regime as legitimate. Why, for example, does democracy have to be liberal and not just any type of democracy or government that people somehow have decided on? It would seem a very narrow – and historically and geographically rather limited – understanding of legitimacy and legitimate government. A second related objection would be that the importance of the question of political order is being ignored. Political order, i.e. the absence of anarchy, violence and civil war, opponents would hold, is the summum bonum of political morality.Footnote 14 Third, it is difficult to establish with certainty when the principles of liberal democracy have been violated, because it is by no means clear what ‘liberal democracy’ actually means.

The reply to the first objection would require a longer discussion, which space does not permit. However, the main argument against the objection is that the argument for the legitimacy of other forms of government in the end refers to some kind of self-government by the people, the preconditions for which are absent when liberal democratic rights are absent. Moreover, the argument for self-determination cannot be an argument for ending self-determination. In particular, it is unclear why democratic rights would entail the power to abolish democracy and remove the democratic rights of others.Footnote 15 The second objection is partly accommodated by bringing in a discussion of non-violent means as the generally most effective means of resisting autocracies and (re-) establishing liberal democratic institutions.

The third objection will be met here by introducing a more minimalist definition of when the preconditions for legitimate rule do not obtain. Given that liberal democracy and the content of liberal democratic rights are complex notions and contested issues, caution counsels us to employ a lower and simpler threshold in practice to decide when the preconditions of political legitimacy are absent. Following Rijpkema, the suggestion here is to set the threshold where a political regime is no longer able via democratic procedures to correct its (wrong) decisions to change away from liberal democracy.Footnote 16 To maintain democracy’s ability to autocorrect, the principles of evaluation, of political competition and of freedom of expression and of secure rights should be in place.Footnote 17 This is the case when there is an extensive right to vote and stand for election, when there is freedom of association and to establish political parties, and freedom of expression including, arguably, as a precondition for the latter, independent (public) media. The efficient and effective protection of rights requires the existence of independent courts.

With the notion that a political regime is beyond democratic repair when the principles of effective evaluation, competition, expression and rights protection are undermined by governing parties, we have relatively simple and minimalist criteria for when citizens may act against non-liberal-democratic parties to defend their rights. At first glance, the minimalism makes it easier to tell when the preconditions for legitimate political rule are gone. However, it still leaves us with the question of when and how citizens can achieve a reliable informational basis for deciding whether to act. A specific challenge here is that citizens would be well advised – as well as justified – to act before non-liberal-democratic parties have actually changed institutions and rights in violation of these principles. The challenge pertains to our scenario 2, where non-liberal-democratic parties have gained power as well as to what citizens can do to avoid ending up in scenario 3, where non-liberal-democratic parties have changed the regime away from democracy.

The epistemic challenge of knowing whether parties after gaining power will violate the principles of liberal democracy cannot be eliminated completely. However, it might be reduced in a number of ways. First, recent research shows that ‘illiberal parties’ that do not express clear commitment to the democratic rules of the game, deny the legitimacy of political opponents, tolerate or encourage violence or are willing to curtail civic liberties of opponents and the media will, more often than not, make steps away from democratic rule and towards autocratisation.Footnote 18 Thus democratic citizens should be very attentive to the public statements of parties, including their political and legislative programs. Second, problematic parties can be identified by a (self-proclaimed) affiliation with predecessor parties with a history involving criminal regimes, such as the fascist regime in Italy or the Nazi regime in Germany. History has already debunked such parties’ ideology, and they do not deserve the benefit of the doubt.Footnote 19 Third, the anti-liberal-democratic track record of parties from earlier periods in government as well as expressions of solidarity with and admiration of parties (in other countries) that have violated key principles of liberal democracy are other ill omens.

To repeat, knowledge of what non-liberal-democratic parties are planning or are likely to do is important for citizens’ action. Although by definition non-liberal-democratic parties have non-liberal-democratic agendas, the permissibility of citizens’ actions will depend on the conditions of political legitimacy. The next section discusses, in light of the changing conditions from scenario 1 to 3, under what conditions which types of action directed against non-liberal-democratic parties are permissible for democratic citizens to undertake. The discussion follows the logic of going from bad to worse but is not structured directly on the three scenarios since this would obstruct necessary excursuses. Instead, the implications for the three scenarios will be spelled out in the following section, which in a structured manner delivers the explanation for the escalation ladder in Figure 1. So, how can democratic citizens react to non-liberal-democratic parties?

Permissible citizen actions

At the most fundamental level, citizens’ actions can be communicative or strategic (non-communicative). Communicative forms of action aim to reach an understanding between actors and, accordingly, (new) agreements are based on a common understanding. Actors change their respective positions because they have changed their minds, their worldviews and values, through insights obtained through communication – or through dialogue in a wide sense of the word. Strategic actions aim to change the position of others through manipulation and/or pressure. Here actions, including speech acts, are aimed at producing an effect in the other actor (person) through manipulation, threats or direct coercion. While analytically separate, empirically the two forms of action are likely to be mixed.Footnote 20

From a normative point of view, communicative engagement with opponents is the first best mode of engagement because it expresses respect of the opponent as an equal dialogue partner.Footnote 21 This mode of engagement is in line with a deliberative conception of democracy, and it requires that democratic citizens make great efforts to understand non-liberal-democratic parties and their supporters, their values, and how they see the world and themselves in it and consider whether and how their claims might be accommodated.Footnote 22

However, the initiatives of democratic citizens do not all have to be based solely on argumentative speech in the strict sense. Modern politics does not (only) consist of town hall meetings. Political and public exchanges take place in public spaces and in different media (papers, radio, TV, internet, social media), and some forms of demonstrations, happenings and even civil disobedience can be considered communicative.Footnote 23 By dramatising and enhancing problems and grievances, they are aimed at increasing the understanding of political opponents of the nature and importance of specific issues relating to democracy and justice. Of course, such initiatives require a fine balance to the extent that opponents may feel manipulated, threatened and/or ridiculed by such initiatives.Footnote 24

While this communicative mode of engagement with others is to be preferred, it may not be very effective if or when non-liberal-democratic parties do not have a performative attitude towards their opponents and do not consider them free and equal citizens. Or in Rawlsian language, non-liberal-democratic parties may consist of unreasonable citizens who are not willing to seek fair terms of cooperation with other citizens and to provide public reasons for their points of view.Footnote 25 Rawls suggested that unreasonable citizens should be contained ‘like war and disease’.Footnote 26 This does not entail stripping them of all their rights,Footnote 27 and stripping parties and citizens of rights is not in any case something that ‘citizens as citizens’ can do. As long as sufficiently democratic institutions are in place, they have the authority (within limits) to define the rights of citizens and parties. However, the likely unreasonableness of non-liberal-democratic parties provides reasons for democratic citizens to undertake strategic forms of action to contain them. Under the conditions of legitimate democratic rule, such strategic actions should be within the parameters of the actions that are permitted by liberal democratic rights. Drawing inspiration from old and new forms of antifascist and anti-populist tactics, some of them could be:

-

showing oppositional strength by numbers in streets and piazzas;

-

holding counterdemonstrations when non-liberal-democratic parties march or meet;

-

obstructing political meetings with non-violent means (heckling and drowning out of speakers etc.);

-

name and shame members and economic sponsors of non-liberal-democratic parties;

-

put pressure on non-liberal-democratic parties and third parties (e.g. conference venue providers) through boycotts, strikes and bad publicity;

-

use the right of association and non-association to exclude non-liberal-democratic members from important social contexts.

A possible objection to these examples is that some of them constitute a violation of the rights of non-liberal-democratic parties, for example the obstruction of political meetings. Whether this is true depends on how much weight one should give to undisturbed meetings compared to freedom of expression of individuals. This issue cannot be settled here. However, in general, this non-communicative use of liberal democratic rights can take place without breaking the law and violating the rights of non-liberal-democratic parties and their members. The liberal democratic rights of citizen are generally justified with a view to securing their equal freedom. More concretely, each right refers to the ability of individual citizens to realise important interests including their interest in leading a life on their own terms. Rights are thus protecting important interests of individuals, including the interest in preserving the ability to pursue interests. It is inherent in the idea of rights that they entitle citizens to pursue their interests also through the strategic utilisation of their rights.Footnote 28 Nonetheless, an objection could be that the coordinated strategic use of rights undermines democratic procedures and decisions regarding the system of rights and freedoms that all citizens should have because it significantly reduces the real freedom of the targets of such coordinated action.Footnote 29 The rejoinder is that under the non-ideal circumstances in which not all are clearly committed to liberal democratic principles, the strategic use of rights is to compensate for the less than ideal democratic procedure and to keep the goal of maintaining liberal democratic principles and rights of all on the political agenda.Footnote 30 However, the objection could be accommodated by admitting that a clearer divergence from liberal democratic principles and a closer proximity to government power by non-liberal-democratic parties would justify more severe forms of strategic employment of civil and political rights by democratic citizens. The question is now whether – and if so, when – democratic citizens are permitted to go beyond the strategic employment of rights. The literature on civil disobedience addresses this question.

Civil disobedience in the protection of liberal democracy

The argument for civil disobedience is based on the idea that under certain circumstances, in which justice and democracy are violated by a specific law or policy, it is justified for citizens to deliberately break the law. This potentially violates the rights of other citizens, including their right to have common democratic decisions respected, and entails the risk of a degree of lawlessness and poor protection of rights. According to the often cited Rawlsian account of civil disobedience, it is permissible for groups in ‘nearly just’ societies to use civil disobedience to draw attention to instances of injustice that clearly conflict with rights based on the principles of equal liberty and opportunity, provided that people act publicly and in honesty, that they communicate openly about what they see as injustices and how to remedy them, and that such acts do not entail violence against persons. Civil disobedience also requires that people are willing to accept the legal consequences of breaking the law.Footnote 31

If arguments for civil disobedience are sound, they might open up a broader array of actions in the protection of liberal democracy. However, a further question is whether non-liberal-democratic parties and their members can legitimately be the objects of such acts of civil disobedience. The traditional argument for civil disobedience focuses on the state and government policies, and this would seem to leave non-liberal-democratic parties out, at least as long as they are not in government. Nevertheless, some accounts expand the objects of civil disobedience to (private) actors who contribute to, support or benefit from unjust and undemocratic regimes and societal structures.Footnote 32 Delmas argues that the object of civil disobedience can also be (unintended) structural injustices that emerge from ‘morally unacceptable values or belief systems’.Footnote 33 This means that injustice/oppression not only relates to institutions or the basic structure but also to the ideologies held and/or ‘social meanings that shape and filter how we think and act’.Footnote 34 Including ideologies as the objects for civil disobedience next to institutions and policies would mean that non-liberal-democratic parties – when they are big and growing – as carriers of problematic ideologies can become the targets of activities that violate their liberal democratic rights, including those of their members.

To sum up, acts of civil disobedience entail breaking the law and with it the rights of other citizens (as a minimum their democratic rights). The standard Rawlsian argument is directed against the state and government policies. It may include both direct and indirect forms of civil disobedience but is always non-violent. On this conception, civil disobedience would only be relevant in the cases where non-liberal-democratic parties are in government but not when non-liberal-democratic parties are in opposition (scenarios 2 and 3). Some alternative accounts include third parties with morally unacceptable belief systems among the objects of civil disobedience. And this would include non-liberal-democratic parties also outside of government (scenario 1).

Along with others, Candice Delmas breaks with the Rawlsian tradition and expands the view of civil disobedience.Footnote 35 She divides ‘principled disobedience’ against different kinds of injustice and oppression from political institutions, policies, ideologies, general practices etc. into civil and uncivil disobedience’. To her, civil disobedience is:

a principled and deliberate breach of law intended to protest unjust laws, policies, institutions, or practices, and undertaken by agents broadly committed to basic norms of civility. This means the action is public, non-evasive, nonviolent, and broadly respectful or civil (in accordance with decorum).Footnote 36

By contrast, she describes uncivil disobedience as consisting of:

[a]cts of principled disobedience that are covert, evasive, anonymous, violent, or deliberately offensive are generally (though not necessarily) uncivil. Examples include guerrilla theater (illegal public performances often designed to shock, in pursuit of revolutionary goals), antifascist tactics such as ‘black bloc’ (which often involves destruction of property), riots, leaks, distributed-denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and vigilantism.Footnote 37

Delmas sees civil disobedience as mainly communicative, i.e. as oriented towards changing the minds of government and co-citizens, while uncivil disobedience is a strategic form of action directed towards pressuring opponents to give up their positions. Arguably, both simultaneously involve a communicative and a strategic dimension. This means that both civil and uncivil disobedience can induce others to change their position, for example because they are scared, but they can also lead to the authentic realisation by other citizens, including supporters of non-liberal-democratic parties, that aspects of the current state of affairs, for example the policies of non-liberal-democratic parties, are wrong. Still, the most problematic aspect of uncivil disobedience is the use of violence and vigilantism. Both civil and uncivil disobedience are problematic when the preconditions for legitimate rule are in place, and the non-liberal-democratic parties are in opposition (scenario 1), but less so in contexts where those preconditions are being undermined or completely removed, as they are when non-liberal democratic parties are in government (scenarios 2 and 3). Civil disobedience is thus relevant in a process where the regime with non-liberal-democratic parties in charge deteriorate from liberal democracy to democracy as auto-correction (an example of a nearly just system) as a way of stopping and reversing this process. Uncivil disobedience would be prima facie relevant as action to prevent the regime from making the last move beyond the democratic point of no return as well as when this point of no return has been passed. Uncivil disobedience would, in these cases, have a large overlap with self-defence on the part of citizens, as self-defence ultimately would include organised violent resistance and revolution on the part of democratic citizens. To understand why this is so, we need a look at the ethics of self-defence. Again, space only permits us to touch on the most general features of this discussion.

The ethics of citizens’ democratic self-defence

There is general agreement in the literature on self-defence that those who want to violate the rights of others incur a liability to harm and thereby lose some right against being harmed by others who are acting in self-defence. The predominant focus in the ethics of self-defence is on death, i.e. on the permissibility of you killing people in self-defence who are likely to kill you. However, it also pertains to lesser rights violations. Important among these are the right to self-determination and, more controversially, the right to be treated as a moral and political equal in society.Footnote 38

In general, however, there is thought to be a difference between the rights protecting ‘vital interests’ and those protecting ‘lesser interests’, and this could imply that using violence and coercion in the protection of political rights (or rights tied to dignity) is problematic. Narrow proportionality, according to which reactions and harm (likely to be) sustained should be at the same level, would imply that armed and lethal self-defence is not justified in relation to violations of rights protecting lesser interests, in particular political rights.Footnote 39 Whether this position is tenable depends on a number of things and I here rely on two partly overlapping accounts of why and how citizens can defend their rights without wanting to settle definitively which approach is the most convincing. The two accounts are respectively the aggregate account and the conditional threat account. According to the aggregate account developed by reductivists in the ethics of war, the sheer number of rights violations makes a difference. There is a difference between stripping one person of their political rights and stripping a whole population of them (save perhaps the members of non-liberal-democratic parties).Footnote 40 Similarly, on the conditional threat account,Footnote 41 if the non-liberal-democratic regime is or is likely to be only lightly oppressive and not generally violating vital interests but is thought to be very repressive in its response to citizens resisting it (perhaps because of the existence of conditional threats on the side of the regime), citizens would be justified in acting pre-emptively in defence of their rights. The regime has no right to ask them to relinquish their non-vital rights, and citizens would be justified in responding proportionally in defence of their vital interests (threatened by the regime qua its warning about the dire consequences of resistance).Footnote 42

In general, the ethics of self-defence suggest that you are justified in acting pre-emptively with regard to rights violations. If you have clear knowledge or a credibly supported presumption that a violation of your rights is going to take place, you would also be justified in pre-empting it with proportionate means, including the use of violence or coercion.Footnote 43 You do not have to wait until the killer starts shooting at you or the rapist starts tearing off your clothes. The same applies to the violation of lesser rights, although again the principle of proportionality implies that your response would have to be proportionate to the rights violation that you are likely to suffer. The aggregate account of self-defence of lesser rights would imply that the response could be rather substantial, while on the conditional threat account, democratic citizens would have to take into consideration how the regime is likely to respond to resistance.

At the level of individual cases of rights violation, the right to self-defence depends very much on the existence of well-functioning public institutions. So generally in situations in which public institutions are well functioning, the argument would be that threats of rights incursions have to be imminent and of such a nature that they could not be rectified via compensation at a later point (for example theft of replaceable objects).

The absence or presence of public institutions is indeed central to the discussion of the scenarios discussed here. The key issue is that when non-liberal-democratic parties have removed the preconditions for democracy as self-correction (and liberal democracy), there will be no public institutions left through which democratic citizens would have a reliable chance of rectifying the violation of political rights. The (imminent) removal of the rights of liberal democracy (or – pragmatically – democracy as self-correction) implies not only a removal of significant (even if not necessarily vital) rights but also the removal of all legitimate authority. This means that the rights that citizens are left to defend on their own grow considerably,Footnote 44 for the removal of legitimate rule implies that what is nominally the state in principle is simply one group of citizens exerting coercion – whether based on ‘laws’ or not – on other citizens.

The loss of functioning public institutions is a great loss, even if it does not lead to a strongly repressive regime. It takes away the ability to make legitimate political decisions and – formally – the possibility for all citizens to act together in directing their common society. The Refah case mentioned in the introduction is an example of the logic at stake. The worry was that the Refah party would form an Islamic majority government and undermine the secular and democratic nature of the Turkish state. The Turkish court and the European Court of Human Rights argued on this background that it was justified to prevent this from happening by banning the party.Footnote 45 For democratic citizens, the case is primarily illustrative since it cannot be presumed that they somehow control the constitutional court. They find themselves outside the official institutions.

It is difficult to tell what the narrowly proportionate response is to a violation of the right to individual and collective self-government. On the aggregative account, armed (and lethal) responses would seem justified.Footnote 46 On the conditional threat account, the reaction thought justified might be less severe. This account would argue that the citizens would be justified in using coercion and violence at the same level as that of the non-liberal-democratic regime. They can, for example, resist arrest and incarceration and would, for example, be justified in detaining members of the regime governed by non-liberal-democratic parties.

If we return to scenario 2, where non-liberal-democratic parties are in government, and think about possible pre-emptive actions by democratic citizens, it might seem problematic to envision that they detain members of the non-liberal-democratic regime. It would be more plausible to point to those forms of actions that fell under Delmas’s conception of uncivil disobedience such as guerrilla theatre, black blocs, riots, leaks and distributed-denial-of-service attacks. These forms of action include violence against public property and private property belonging to non-liberal-democratic parties (and their members) and applying non-lethal and non-injurious coercion against people employed by the stateFootnote 47 and the non-liberal-democratic parties. Such action may also contain a communicative dimension that is absent from incidents of physical violence against persons.

A key question, of course, is whether such actions are effective or, by contrast, counterproductive. This is very context dependent and would be important for their all things considered permissibility (I return to this question below).

In scenario 3, where governing non-liberal-democratic parties have definitively undermined democracy, the conception of the potentially violent and coercive actions by democratic citizens is necessarily different from scenario 2. First, the notion of citizens being disobedient is strictly speaking no longer relevant in scenario 3, since disobedience implies the existence of an authority, including the authority of the law, that you otherwise should obey. Second, the lack of legitimate authority makes the case for democratic self-defence by citizens with coercion or violence against non-liberal-democratic parties even more clear. Autocracy does not have a right to rule, and democratic citizens would prima facie be justified in resisting its laws and commands and attempting to overthrow it in a revolution.Footnote 48

At first sight, then, the ethics of self-defence suggest that democratic citizens would be justified in using coercion or violence in defence and promotion of their liberal democratic rights, albeit in proportion to the harm they suffer. However, the ethics of self-defence include potential harms to third parties in the deliberation about permissible courses of action. For example, would it speak against coercive measures if otherwise mildly oppressive non-liberal-democratic regimes turn very repressive and indiscriminately injure third parties when they are resisted?

It can be questioned how much responsibility democratic citizens should have to bear for the regime’s reaction to others, since it easily leads to a problematic argument for passive acquiescence to rights violations. Nonetheless, democratic citizens need to choose the ‘lesser evil’ and make sure that their reactions to the regime do not create more harm than necessary.Footnote 49 Democratic citizens should abstain from violent or coercive measures if they are not effective in halting or reversing regime change, unless they are unavoidable for them individually, say when they are directly attacked. And if they are not necessary, i.e. if there are other non-violent (or less violent or coercive) measures that on average would get the same result, they would not be justified either.

This brings us to the objection from order mentioned in the introduction. The common objection is that political order and a condition of right – as Hobbes and Kant argued, each in their way – is preferable to the chaos, anarchy, and lawlessness that would result from such resistance and attempts to revolt. This makes the resistance and attempts to revolt questionable, especially because it undermines an important good for other citizens (‘innocent bystanders’), who might just want to live in relative peace, and who may become victims of violence exercised by either democratic citizens or the autocratic regime. This objection is important.

It is implausible that democratic citizens should just stand by idly when their rights are being removed, regardless of whether they are being threatened with severe repercussions by the regime and regardless of whether the regime decides to strike hard against innocent bystanders. It is also empirically unclear that the loss of democratic rights and the loss of general rule of law guarantees do not co-vary in the sense that even in relatively peaceful autocracies, citizens de facto live in a condition of lawless domination.Footnote 50 Also, as Buchanan argues, it is possible for democratic citizens to establish civil society organisations that would be able to secure basic justice in the transition (back) to democracy.Footnote 51

Nonetheless, the fact that violent and coercive strategies on average are not effective, and the fact that non-violent strategies on average are more effective, make them unnecessary. Empirical studies show that civil or non-violent resistance to autocracy in general is much more effective than violent resistance and for good reasons. Democratic citizens will often not be able to match the coercive resources of the regime.Footnote 52 Non-violent resistance is not only more likely to gain greater support among and participation by other citizens (including among the security forces and other erstwhile supporters of the regime), it is also more likely to result in more durable and internally peaceful democratic institutions.Footnote 53 This implies that in many cases, violent or coercive resistance would not be necessary. Even though it is possible to imagine that non-violent forms are not available to democratic citizens, for example where a regime is very repressive, it is likely that the non-violent resistance would be available to most democratic citizens and at a lesser cost.

Taking the comparative effectiveness of non-violent strategies into account, the general argument is thus against using violence and coercion in the self-defence of democratic citizens unless it is the only effective alternative available. Citizens should limit themselves to communicative action and to strategic action types that fall within the boundaries of the exercise of their liberal democratic rights. In scenarios 2 and 3, where some or most liberal democratic rights have been removed, this may imply that democratic citizens do something that is illegal from the viewpoint of the governing non-liberal-democratic parties.

However, we might add some detail to this overall conclusion in favour of non-violent strategies. As indicated above, it does not have to be completely categorical. We might imagine the use of some forms of violence and coercion in an overall non-violent strategy, taking into consideration the potential communicative dimension of certain types of violence. We can distinguish between violence against: (1) persons; (2) public property; and (3) private property. In certain circumstances, otherwise non-violent protests may become more effective when they include symbolic violence against public property and property of regime supporters (e.g. the property of non-liberal-democratic parties), and exercising such violence against property carries the risk of ending in violent confrontation with police and security forces, which means that some level of violence against persons might be practically unavoidable.

Symbolic violence against property, e.g. graffiti or vandalism, is not the same as (organised) violence against individual persons or groups of persons, in casu members of non-liberal-democratic parties. Similarly, blocking the free movement of others temporarily, e.g. by forming human barriers, is not the same as injuring them physically. The communicative potential of this kind of violence combined with its non-injurious nature would work together with the general non-violent approach to enhance its impact. That is, it will make some parts of the audience or adversaries realise what is undemocratic or unjust about existing policies etc.

In other words, it is not entirely clear that otherwise peaceful forms of resistance could not involve some aspects of violence that would enhance their effectiveness. We can thus imagine that peaceful and otherwise non-violent action by democratic citizens would involve direct action against non-liberal-democratic parties, e.g. against their buildings, party infrastructure, and against the ability of members to make decisions or pass legislation that will undermine liberal democratic institutions and rights, e.g. blocking access to the parliament and/or government offices. Table 1 sums up the discussion on permissible types of action by democratic citizens under different conditions of legitimacy and explains in full the escalation ladder in Figure 1 (in the introduction). The next section briefly spells out what the result of the discussion means for democratic citizens placed in each of the three scenarios.

Table 1. Permissible citizen actions under different conditions of legitimacy

Democratic citizen actions against non-liberal-democratic parties in opposition and in government

In scenario 1, non-liberal-democratic parties have become an important part of political life but are in opposition. Current examples would be Germany or France. In this context, citizens can use deliberative means to persuade non-liberal-democratic party members (and supporters) to change their mind. This would involve the genuine ambition also to understand non-liberal-democratic party and supporter worldviews. However, to the extent that non-liberal-democratic parties largely remain strategic and unreasonable in what they say and do, democratic citizens will be permitted to use non-communicative forms of action that remain within the boundaries of the exercise of their liberal democratic rights.Footnote 54 In scenario 1, the preconditions of legitimate democratic rule are intact, and this counts against breaking the law in ‘civil disobedient’ actions against non-liberal-democratic parties as third parties.

Scenario 2 is a borderline case. Here non-liberal-democratic parties have gained power but have not yet changed the liberal democratic institutions and rights. Or at least, they have not yet changed institutions and rights in such a way that it cannot be corrected via the democratic procedure. Real-life cases would be Poland and Hungary. On first impressions, the fact that there are at least some minimum conditions available for making legitimate political decisions speaks against democratic citizens taking matters into their own hands, disobeying the law and employing violence and coercion to defend democracy. However, if the arguments for civil disobedience are sound, democratic citizens may use forms of civil disobedience to draw attention to the injustice and oppression that are in store if no action is taken (2a). Also, citizens are allowed to act pre-emptively to defend their liberal democratic rights and the preconditions for public authority with violence and coercion (uncivil disobedience), if the specific circumstances do not leave them any (more) effective non-violent options (2b).

In scenario 3, the preconditions for legitimate public rule have been removed. There is no way back to liberal democracy via democratic procedures. The scenario covers cases like Belarus and Russia. This means that nominal public authorities really are just one group of citizens exercising coercion and ultimately violence against other citizens. Under these circumstances, democratic citizens are prima facie entitled to defend their rights with violence and coercion, if they are effective and necessary. However, since non-violent forms of protest and resistance are generally more effective than violent forms, democratic citizens should abstain from using violence as a general form of action against non-liberal-democratic parties. The same point applies to the pre-emptive self-defensive action in scenario 2b.

The paper began by asking whether the tactics applied by Antifa groups in Germany against the party Alternative für Deutschland were completely out of bounds. The answer is that they are not. But they would have to be reserved to instances where either democracy is gone or you have a solid presumption that it will be removed very soon and you have no good non-violent alternatives. This is not the case in Germany, so some of the scare tactics used by German Antifa groups are unjustified. In Poland, and more plausibly Hungary, the conditions are different, and it would be less clear that such tactics are categorically wrong. Still, the Sardines movement in Italy is the better example to follow. The Sardines are explicitly tied to the defence of the liberal democratic values in the Italian constitution (democracy, freedom and equality) and are unambiguously antifascist and anti-violent.Footnote 55 Their inclusiveness enhances their ability to build strong opposition against non-liberal-democratic parties, and their actions point to the importance of directing the attention not only to non-liberal-democratic parties but to the citizenry at large. Building large liberal democratic coalitions by appeal to other citizens may be more important than fighting non-liberal-democratic parties directly.

Conclusion

The discussion on militant democracy and more broadly on democracy’s defence has predominantly focused on the role of public institutions and political parties. Although there is wide agreement that the democratic identity and virtues of citizens are vital for maintaining democracy, less attention has been paid to how active democratic citizens can defend democracy. This paper has sought to remedy part of this shortcoming by providing a rough outline of permissible types of actions by democratic citizens against non-liberal-democratic parties under different conditions of political legitimacy. As carriers of non-liberal-democratic ideologies, the existence and growth of the latter are indications that liberal democracy is not fully consolidated and in potential danger. As suggested in the previous section, other objectives of citizen activities to defend democracy should also be discussed. Among them are other citizens broadly conceived, public institutions, governments, (liberal democratic) mainstream parties as well as international and supranational institutions. However, within its focus on non-liberal-democratic parties, the paper’s main argument has been that while different conditions of legitimacy in principle open up different types of actions, communicative as well as non-communicative, violent as well as non-violent, democratic citizens should in general consider sticking to communicative and non-communicative non-violent types of action that are – or would be – within the boundaries of their liberal democratic rights.