No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 February 2009

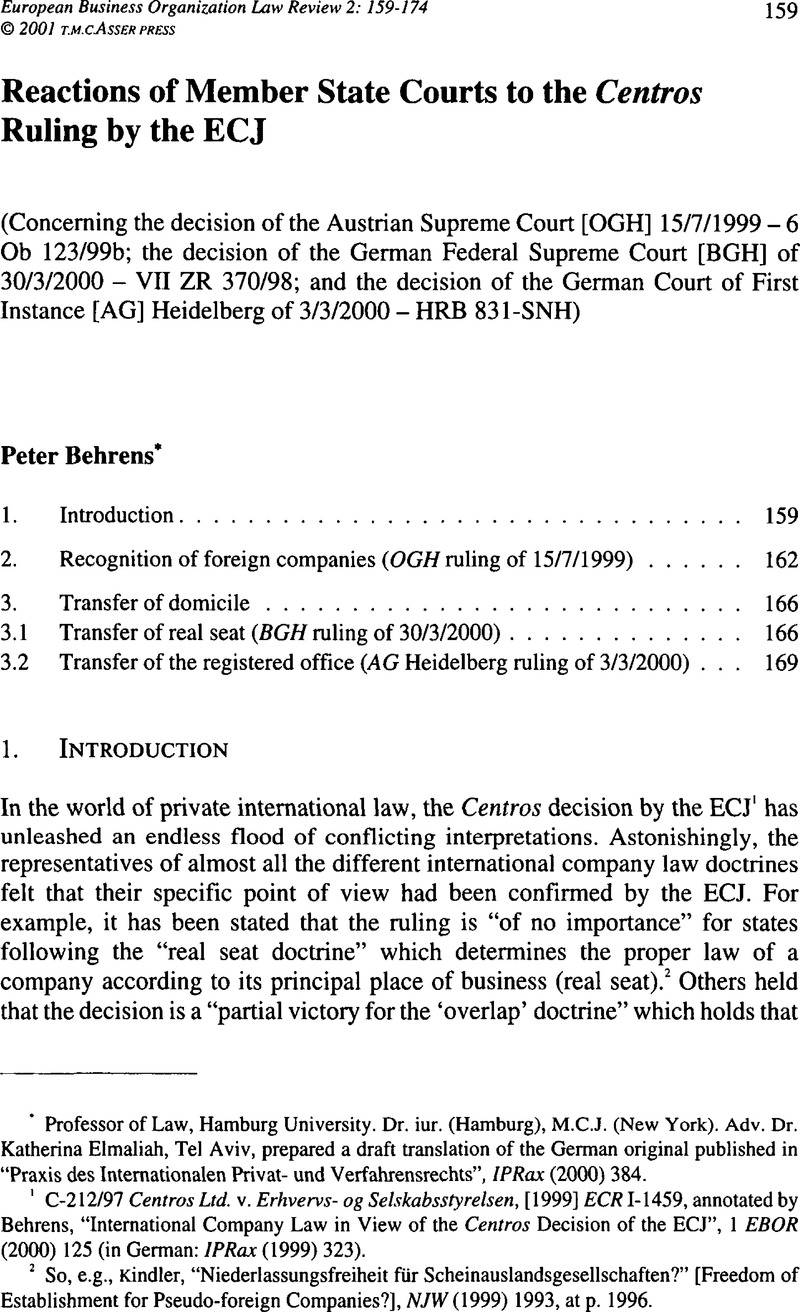

1 C-212/97 Centros Ltd. v. Erhvervs- og Selskabsstyrelsen, [1999] ECR1-1459, annotated by Behrens, , “International Company Law in View of the Centros Decision of the ECJ”, 1 EBOR (2000) 125Google Scholar (in German: IPRax (1999) 323).Google Scholar

2 So, e.g., Kindler, , “Niederlassungsfreiheit für Scheinauslandsgesellschaften?” [Freedom of Establishment for Pseudo-foreign Companies?], NJW (1999) 1993, at p. 1996.Google Scholar

3 Sandrock, , “Centros: ein Etappensieg für die Überlagerungstheorie” [Centros: A Partial Victory for the Overlap Doctrine], BB (1999) 1337. See Behrens, supra n. 1.Google Scholar

5 Flessner, , “Schiffbruch der Interpreten und Statuten” [A Shipwreck of Interpretations and Proper Laws], ZEuP (2000) 1.Google Scholar

6 So ibid., at p. 4.

7 C-81/87 The Queen v. HM Treasury and Commissioners of Inland Revenue, exparte Daily Mail and General Trust pic [1988] ECR 5483 = IPRax (1989) 381, annotated by Behrens, , “Die grenzüberschreitende Sitzverlegung von Gesellschaften in der EWG” [Cross-Border Transfer of a Company Domicile within the EEC], IPRax (1989) 354, at p. 359.Google Scholar

8 On the same day, a very similar ruling was delivered in parallel proceedings (6 Ob 124/99z), which, however, is not worth analyzing, because it is almost identical to the ruling discussed here.

9 For a comparison between the private company and the GmbH, see Behrens, , “Great Britain and Ireland”, in: Behrens, (ed.), Die Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung im internationalen und europäischen Recht [The Limited Liability Company in International and European Law], 2nd ed. (Berlin: de Gruyter 1997) no. GB/NI/EI 14.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

10 The provision reads as follows: “The proper law of a legal entity or any other association of persons or unity of assets with the capacity to assume rights and obligations under the law, is the law of the state of the real seat of the headquarters of such entity.”

11 This follows from the considerations of the OLG.

12 In harmony with these principles established by the OGH is Behrens, supra n. 1.

13 See for example the reviews of Mäsch, , JZ (2000) 201Google Scholar, and Kieninger, , NZG (Neue Zeitschrift für Gesellschaftsrecht) (2000) 39.Google Scholar

14 See Carsten, “Dänemark”, in: Behrens (ed.), supra n. 9, no. DK 49.

15 Of this opinion are however Mäsch, supra n. 13; Kieninger, supra n. 13.

16 Behrens, “Niederlande”, in: Behrens (ed.), supra n. 9, no. NL 10.

17 § 124 para. 1 HGB reads as follows: “The general commercial partnership may under its business name acquire rights and assume obligations, purchase ownership and other rights in rem in real estate as well as file claims and be sued in court.”

18 On this interpretation of a company's resolution to amend its articles of association by changing the registered office and transferring it abroad, see Behrens, , “Identitatswahrende Sitzverlegung einer Kapitalgesellschaft von Luxemburg in die Bundesrepublik Deutschland” [Identity-preserving Transfer of Domicile of a Company from Luxembourg to the Federal Republic of Germany], RIW (1986) 590Google Scholar; Id., “Die Umstrukturierung von Unternehmen durch Sitzverlegung oder Fusion über die Grenze im Licht der Niederlassungsfreiheit im Europäischen Binnenmarkt (Art. 52 und 58 EWGV)” [Restructuring of Enterprises by a Cross-Border Transfer of Domicile or Merger in Light of the Freedom of Establishment in the European Single Market (Arts. 52 and 58 ECT)], ZGR (1994) 1, at pp. 9 et seq..

19 On the equivalence of the German GmbH and the Spanish SL, see Keil, “Spanien”, in: Behrens (ed.), supra n. 9, no. E 11.

20 This would correspond with the solution presented in Arts. 163 and 161 of the Swiss Private International Law Act. Art. 163 provides that a Swiss company may turn into a foreign company and Art. 161 provides that a froeign company may turn into a Swiss company without being wound up and newly incorparated, if certain conditions are fulfilled. See thereon Behrens, supra n. 18.

21 C-221/89 The Queen v. Secretary of State for Transport, exparte Factortame (Factortame II), [1991] ECR I-3905, recital 20 of the Court's decision.

22 Ibid., recital 21.

23 Daily Mail, supra n. 7, recital 16 of the Court's decision.

24 Ibid., recital 23.

25 A few years ago, the EC Commission presented a Draft Proposal for a Fourteenth Directive on the transfer of the registered office or de facto head office of a company from one Member State to another with a change in the applicable law, XV/6002/97, published in ZIP (1997) 1721.

26 Behrens, , “Gemeinschaftsrecht und juristische Methodenlehre” [Community Law and Legal Methodology], EuZW (1994) 289.Google Scholar

27 See supra n. 25. The presented draft directive will need to be reviewed following the Centros ruling.