Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are a group of pervasive developmental disorders characterized by core deficits in three domains, i.e. social interaction, communication and repetitive or stereotypic behaviour (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), occurring more often in boys than girls (4:1). There has been a significant increase of ASDs over the past few decades, with an incidence of approximately 4 per 10 000 to 6 per 1000 children (Lasalvia & Tansella Reference Lasalvia and Tansella2009; Pejovic Milovancevic et al. Reference Pejovic Milovancevic, Popovic Deusic, Lecic Tosevski and Draganic Gajic2009; Faras et al. Reference Faras, Al Ateeqi and Tidmarsh2010). The causes of autism remain largely unknown, but there is evidence that genetic, neurodevelopmental and environmental factors are involved, alone or in combination, as possible causal or predisposing effects of developing autism (Pensiero et al. Reference Pensiero, Fabbro, Michieletto, Accardo and Brambilla2009). Although the degree of impairment among individuals suffering from autism may vary, the impact on affected individuals and their families is generally life-changing. Most studies of ASDs are focused on epidemiology, genetics and neurobiology, but more intervention research is needed to help individuals with autism, their caregivers and educators. In this context, it is crucial to develop tools for neurocognitive habilitation enabling children with ASDs to increase their ability to perform daily-life activities. A rather promising tool has recently emerged in many domains of rehabilitation, namely virtual reality (VR) (Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Rizzo, Rogers and York2009). VR is a simulation of the real world based on computer graphics and can be used as an educational and therapeutic tool by instructors and therapists to offer children a safe environment for learning. Virtual environments (VEs) simulate the real world as it is or create completely new worlds, and provide experiences that can help patients understand concepts as well as learn to perform specific tasks, which can be repeated as often as required (Chittaro & Ranon, Reference Chittaro and Ranon2007). Furthermore, VEs are better suited for learning than real environments since they (1) remove competing and confusing stimuli from the social and environmental context, (2) manipulate time using short breaks to clarify to participants the variables involved in the interaction processes and (3) allow subjects to learn while they play (Vera et al. Reference Vera, Campos, Herrera and Romero2007).

The realism of the simulated environment allows the child to learn important skills, increasing the probability to transfer them into their everyday lives (Strickland, Reference Strickland1997). Until recently, head-mounted displays (HMDs) were typically used in VR to increase the feeling of immersion in the VE. Unfortunately, besides being a more costly and less comfortable solution with respect to ordinary computer monitors, HMDs may also cause ‘cyber-sickness’ (Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Mitchell and Leonard2004), whose most common temporary symptoms include nausea, vomiting, headache, drowsiness, loss of balance and altered eye–hand coordination. However, VEs can also be visualized and explored using an ordinary computer monitor connected to a common personal computer (desktop VEs). The user can move in the VE using common input devices, such as keyboard, mouse, joystick or touch screen, and interactions between the child and the therapist are also supported. Desktop VEs are more affordable and accessible for educational use, and less susceptible to the symptoms of cyber-sickness.

The literature is increasingly recognizing the potential benefits of VR in supporting the learning process, particularly related to social situations, in children with autism (Strickland et al. Reference Strickland, Marcus, Mesibov and Hogan1996; Strickland, Reference Strickland1997). Research has analysed the ability of children with ASDs in using VEs and several studies, except for one (Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Mitchell and Leonard2005), suggesting that they successfully acquire new pieces of information from VEs. In particular, participants with ASDs learned how to use the equipment quickly and showed significant improvements in performance after a few trials in the VE (Strickland et al. Reference Strickland, Marcus, Mesibov and Hogan1996; Strickland, Reference Strickland1997; Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Mitchell and Leonard2004).

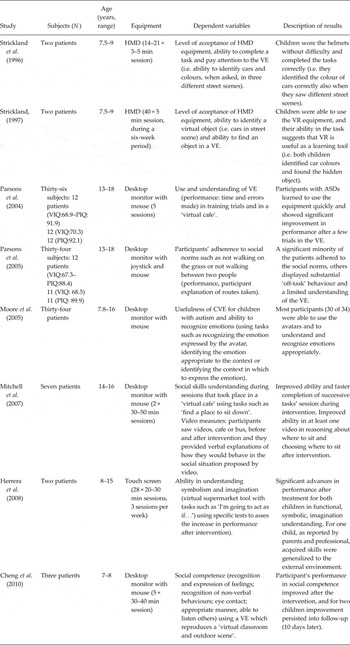

Two studies, using desktop VEs as a habilitation tool, have recently been carried out to teach children how to behave in social domains and how to understand social conventions (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Parsons and Leonard2007; Herrera et al. Reference Herrera, Alcantud, Jordan, Blanquer, Labajo and De Pablo2008). The first study reported that by using a VE that reproduces a ‘virtual cafe’ to teach social skills the speed of execution of the social task in the VE improved after the repetition of the task. The same study showed an improvement of understanding social skills after the VE session. The second study employed a VE that reproduces a ‘virtual supermarket’ with several exercises about physical, functional and symbolic use of objects, finding that the performance of participants, assessed by specific tests, increased after the VE intervention and one child was able to transfer the acquired skills to the real environment. Further studies were carried out using collaborative virtual environments (CVEs) that support multiple simultaneous users, in particular the patient and the therapist, who can communicate with each other through their avatars. CVEs have been used to examine and investigate the ability to recognize emotions (Moore et al. Reference Moore, Cheng, McGrath and Powell2005) and also to improve social interaction, teaching students how to manifest their emotions and understand those of other people (Cheng & Ye, Reference Cheng and Ye2010). These studies, respectively, found a good performance in identifying emotions and an improvement in social performance after the intervention (Table 1 summarizes the major behavioural studies involving VR).

Table 1. Behavioural studies investigating VR in patients with ASDs and healthy subjects

ASDs, autism spectrum disorders; VIQ, verbal IQ; PIQ, performance IQ; HMD, head-mounted display; VE, virtual environment; VR, virtual reality.

The use of VR tools for habilitation in autism is therefore very promising and may help caretakers and educators to enhance the daily life social behaviours of individuals with autism. Future research on VR interventions should investigate how newly acquired skills are transferred to the real world and whether VR may impact on neural network sustaining social abilities.