Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a serious mental health issue, affecting about 17% of mothers (Shorey et al., Reference Shorey, Chee, Ng, Chan, Tam and Chong2018) and 9% of fathers (Rao et al., Reference Rao, Zhu, Zong, Zhang, Hall, Ungvari and Xiang2020). PPD is a major depressive episode occurring during pregnancy or up to 4 months postpartum (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), but a universally accepted definition of PPD is lacking (Abbasi et al., Reference Abbasi, Bilal, Muhammad, Riaz and Altaf2024). Individual studies relate it freely to a period they consider relevant for assessing PPD symptoms (e.g., Baron et al., Reference Baron, Bass, Murray, Schneider and Lund2017).

PPD risk factors in both mothers and fathers include low social support (Dadi et al., Reference Dadi, Miller and Mwanri2020; McCall-Hosenfeld et al., Reference McCall-Hosenfeld, Phiri, Schaefer, Zhu and Kjerulff2016), history of depression (McCall-Hosenfeld et al., Reference McCall-Hosenfeld, Phiri, Schaefer, Zhu and Kjerulff2016; Tebeka et al., Reference Tebeka, Strat and Dubertret2016) and low marital satisfaction (Escriba-Aguir and Artazcoz, Reference Escriba-Aguir and Artazcoz2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Qiu and Xiao2021). Especially for fathers, these risk factors also include unemployment and financial strain (Serhan et al., Reference Serhan, Ege, Ayrancı and Kosgeroglu2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Qiu and Xiao2021), while low economic and educational status were also identified for mothers (Dadi et al., Reference Dadi, Miller and Mwanri2020; McCall-Hosenfeld et al., Reference McCall-Hosenfeld, Phiri, Schaefer, Zhu and Kjerulff2016). Adverse obstetric history correlated with PPD in mothers (Dadi et al., Reference Dadi, Miller and Mwanri2020), and newborn’s impaired health correlated with PPD in both mothers and fathers (Genova et al., Reference Genova, Neri, Trombini, Stella and Agostini2022).

PPD may have important adverse outcomes in children including malnutrition, common infant illness, poorer parent–child bonding and non-exclusive breastfeeding (Dadi et al., Reference Dadi, Miller and Mwanri2020; Handelzalts et al., Reference Handelzalts, Ohayon, Levy and Peled2024). Children in families where both parents or at least mothers experience PPD show higher amount of externalizing and internalizing problems under 5 years of age (Pietikäinen et al., Reference Pietikäinen, Kiviruusu, Kylliäinen, Pölkki, Saarenpää‐Heikkilä, Paunio and Paavonen2020; Volling et al., Reference Volling, Yu, Gonzalez, Tengelitsch and Stevenson2019). However, results are mixed about whether PPD of parents influences the motor and language skills or cognitive development of their children (Aoyagi et al., Reference Aoyagi, Takei, Nishimura, Nomura and Tsuchiya2019; Aoyagi and Tsuchiya, Reference Aoyagi and Tsuchiya2019).

Previous research on PPD risk factors often utilized cross-sectional design on the overall sample (e.g., Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Qiu and Xiao2021; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wu and Chen2022). In contrast, the state-of-the-art approach relies on identifying patterns in the data where subgroups of individuals or couples follow unique (e.g., progressing or regressing) longitudinal depressive symptom trajectories (e.g., Csajbók et al., Reference Csajbók, Štěrbová, Jonason, Cermakova, Dóka and Havlíček2022; Formánek et al., Reference Formánek, Csajbók, Wolfová, Kučera, Tom, Aarsland and Cermakova2020). In a systematic review, the commonest classes found in mothers were (1) a large, stable, low-risk trajectory with minimal symptoms; (2) a small, stable, high-risk trajectory with severe symptomatology; and (3) a stable or transient trajectory with variously serious symptoms (Baron et al., Reference Baron, Bass, Murray, Schneider and Lund2017). Prior psychiatric diagnosis, singlehood, post birth complications, alcohol and tobacco use and hypertension increased the likelihood of belonging to stable high trajectories, while having social support decreased it (Drozd et al., Reference Drozd, Haga, Valla and Slinning2018; Handelzalts et al., Reference Handelzalts, Ohayon, Levy and Peled2024; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Le, Lu, Shi, Xiang, Liu, Zhang, Zhou, Wang, Xu, Yu and Zhao2022). Few studies examined possible PPD trajectories in fathers, but they found similar patterns: low, moderate and high PPD, with financial status being a risk factor (Molgora et al., Reference Molgora, Fenaroli, Malgaroli and Saita2017; Nieh et al., Reference Nieh, Chang and Chou2022). Shared risk factors between mothers and fathers were insomnia, anxiousness, earlier depression, stressfulness and poor family atmosphere (Kiviruusu et al., Reference Kiviruusu, Pietikäinen, Kylliäinen, Pölkki, Saarenpää-Heikkilä, Marttunen, Paunio and Paavonen2020). One study identified four joint, dyadic trajectories: both mother and father non-depressed; both mother and father depressed; mother non-depressed, father depressed; and mother depressed, father non-depressed (Volling et al., Reference Volling, Yu, Gonzalez, Tengelitsch and Stevenson2019). When both parents were depressed, they had worse marital quality, and their child demonstrated more externalizing and internalizing problems.

We compared how overall PPD symptoms and depressive symptom trajectories correlate with PPD risk factors and offspring outcomes in a large, well-characterized prenatal cohort of new parents in Czechia. Since PPD can be a precursor of long-term depressive symptoms in parents (Bloch et al., Reference Bloch, Tevet, Onn, Fried-Zaig and Aisenberg-Romano2024), we uniquely followed parents from the prenatal period until their child was 11 years old. Unlike much of the previous research, we used a dyadic, parallel processes approach to study couples, allowing us to estimate unique combinations of maternal and paternal trajectories in a data-driven manner. By exploring the heterogeneity among couples, we aimed to better identify risk factors that are uniquely applicable to different family trajectory classes.

Methods

Participants and procedure

We analysed data from the Czech arm of the international European Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood (ELSPAC-CZ; Piler et al., Reference Piler, Kandrnal, Kukla, Andrýsková, Švancara, Jarkovský, Dušek, Pikhart, Bobák and Klánová2016). ELSPAC-CZ is a prenatal cohort following children born between 1991 and 1992 in two towns in Czechia (Brno, Znojmo). Mothers were enrolled in the second or the third trimester. Mothers and fathers filled in several questionnaires about themselves and their child, including repeated assessments of their mental health. Presently, we use data from questionnaires administered to the parents at the following time points: in the prenatal period, in the newborn stage and at 6 months, 18 months, 3 years, 5 years, 7 years and 11 years of age of the child. Additionally, we use information acquired from the children themselves at the ages of 11, 15, 18 and 19 years. We excluded mothers and fathers who did not have any measures of depressive symptoms and those who were not biological parents of the children, leaving a sample of 5,518 families. All participants provided written informed consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the ELSPAC-CZ Ethics Committee.

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Edinburgh Perinatal/Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987), which was administered to the mothers and fathers at all follow-up points. The measure has been validated for non-postnatal populations (Becht et al., Reference Becht, Van Erp, Teeuwisse, Van Heck, Van Son and Pop2001; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Chapman, Murray and Jones1996). The scale consists of 10 items concerning the experience of symptoms of depression during the past week. The parents reported to what extent they have experienced the following: ability to laugh, looking forward to things, feeling guilty, being worried, feeling panicky, feeling that things have been getting on top of them, difficulty sleeping, feeling sad, crying, thought of harming oneself. Symptoms were assessed on a 0–3 scale. The final score is the sum of the points from the individual items, where higher values indicate greater severity of depressive symptoms. We considered the cut-off for PPD to be 11 and above (Levis et al., Reference Levis, Negeri, Sun, Benedetti and Thombs2020). We also relied on a general risk assessment for elevated depressive symptoms using 5 as a cut-off (Matthey et al., Reference Matthey, Barnett, Kavanagh and Howie2001).

Covariates

We selected psychosocial, health-related and obstetrical covariates available in the ELSPAC database based on existing literature, focusing on characteristics of parents and offspring that have been linked to parental depressive symptoms (Guintivano et al., Reference Guintivano, Manuck and Meltzer-Brody2018) or offspring psychological outcomes (Pietikäinen et al., Reference Pietikäinen, Kiviruusu, Kylliäinen, Pölkki, Saarenpää‐Heikkilä, Paunio and Paavonen2020). We grouped the selected covariates into eight areas as follows: relationship maintenance, demographic data, socio-economic resources, emotional life, health, obstetric history, parental history, and offspring temperament and mental health. The data on all areas except offspring mental health were reported by the mothers and the fathers in several questionnaires throughout the first 11 years. Here, we consider the information from baseline; if this information was not available in the questionnaire from the prenatal stage, it was taken from the next one, when the information was first available.

Relationship maintenance was categorized in multiple ways: unstable relationship, only married, continuously married, married ever, married later, other than first marriage (remarriage), bereavement, separated, divorced, single (at any point during the study) and continuously cohabitated (no indication of living apart). Demographic data included age of the parents, child’s sex, town (Brno, Znojmo) and education. Data on socio-economic resources concerned income, crowding, deprivation, father’s employment, financial help and living in own house. We also included information about social network and social support. Further information was reported by the mother of the child at 6 months on childcare provided by other people (father, other family members, someone who is not family) expressed in hours per week and the age of the child (in months) when they started to take care of the child.

Information about emotional life concerned relationship aggression, affection and love of the baby (how long it took the mother to love the baby). Information about health concerned the number of diseases, substance use, smoking, alcohol use and use of psychotropic pills. Obstetric history included data about previous pregnancy, number of previous pregnancies, number of own children, history of miscarriage, number of miscarriages, history of abortion, number of abortions and obstetric treatment for getting pregnant.

Information about parental history includes stressful life events (sum of 41 events since pregnancy), parental care (derived from the Parental Bonding Instrument, PBI; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Tupling and Brown1979), overprotection (derived from the PBI items), home stability and sexual abuse. Offspring temperament was assessed in the newborn questionnaire, in which parents rated 14 items based on how much the child shows the characteristics of being whiny, cranky, satisfied, etc. Offspring mental health was completed by the child and included internalizing and externalizing symptoms (derived from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; Goodman, Reference Goodman1997), satisfaction with life (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985) and stressful life events (year 11: 20 events, year 15: 28 events, year 18 and 19: 33 events). Cronbach’s alphas of all scales ranged between 0.65 and 0.90, which is considered an acceptable level of internal consistency (Tables S1 and S6; Bland and Altman, Reference Bland and Altman1997). The detailed definitions of each covariate with rating scales are presented in Supplementary Measures.

Data analysis

Descriptive characteristics are presented as mean and standard deviation or frequency (n, %). Parental longitudinal dyadic depression trajectories were extracted with Latent Class Growth Modelling method (see Supplementary Data analysis). This is a probabilistic method that can identify subgroups in our sample, based on which couples are most likely to follow similar longitudinal trajectories. The Latent Base Growth Model (LBGM) that allows for any shape of trajectories fit better the data than the simple linear growth model (and the curved growth model did not converge), thus we submitted the LBGM to the mixture modelling for classification (Table S2). Relying on the combination of model indices and interpretability, the five-class model was selected for further analysis (Tables S3–S5).

In Methods, we listed all covariates tested, and in Results, only class comparisons across covariates with meaningful associations were mentioned. In the Supplement, (1) the overall sample was correlated with all covariates and we reported only those, which had meaningful associations (Supplementary Results, Tables S7 and S8), and (2) results of class comparisons with weak associations are presented in supplementary tables (Tables S10–S12). The covariates selected for reporting in the main text were identified based on effect size (η 2 > .02, or V > .04). The selected parental and offspring characteristics, if they were continuous variables, were compared between the five classes of couples with Brown–Forsythe ANOVA and Games–Howell post hoc tests due to unequal variances and class sizes. χ 2 tests were used to compare categorical parental characteristics between classes.

Results

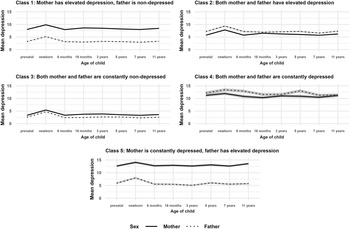

Descriptive statistics and data coverage of the depressive symptoms scores are presented in Table S1. In the overall sample, baseline parental characteristics, along with offspring temperament and mental health, were examined for associations with parental depressive symptoms at each time point using independent samples t-tests and Pearson correlations (see Supplementary Results and Supplementary Discussion). The five-class model of dyadic longitudinal depressive symptom trajectories showed the following patterns of dyads: Class 1 mother has elevated depressive symptoms, father is non-depressed (24.19%); Class 2 both mother and father have elevated depressive symptoms (19.61%); Class 3 both mother and father are constantly non-depressed (42.30%); Class 4 both mother and father are constantly depressed (4.93%); and Class 5 mother is constantly depressed, father has elevated depressive symptoms (8.97%), see Table 1 and Figure 1.

Figure 1. Five classes of parental dyadic depression trajectories presenting mean depressive symptom scores at each time point across mothers and fathers with 95% confidence intervals (shadowed with grey).

Table 1. Proportions of couples and model results of the five-class solution

Note: Variables in the analyses were divided by three to aid model convergence (following the common practice using Mplus software). We converted these results back to the original scaling (i.e., we reported here three times the results presented in Table S4) to help interpretation using the more familiar scoring of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

* p < .05, ***p < .001.

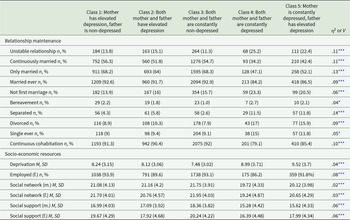

Descriptive statistics and data coverage of the covariates are in Table S6. When we compared the five classes of parents along the selected covariates, the classes differed in relationship stability with the non-depressed Class 3 being the least likely unstable and the depressed Classes 4 and 5 being the most likely unstable, while Classes 1 and 2 were in-between (V = .11, Table 2). Most notably, Class 3 was the most likely married (only married V = .13 and continuously married V = .11) and the least likely separated (V = .14). Class 4 was the least likely married and the most likely divorced considering the entire study period (V = .09). Related to socio-economic resources, we found notable differences in deprivation. Based on the post hoc test, the non-depressed Class 3 was the least deprived and the depressed Classes 4 and 5 were the most deprived, while Classes 1 and 2 were in-between (η 2 = .04). Fathers were the most likely working if non-depressed (i.e., Classes 1 and 3). Both mothers (η 2 = .06) and fathers (η 2 = .06) enjoyed the most amount of social support in the non-depressed Class 3 and the least amount of support in the depressed Classes 4 and 5, while Classes 1 and 2 were found in-between.

Table 2. Brown–Forsythe analysis of variance tests and χ 2 tests comparing the five classes along selected parental characteristics

Note: m = mother, f = father, M = mean, SD = standard deviation.

* p < .05, ***p < .001.

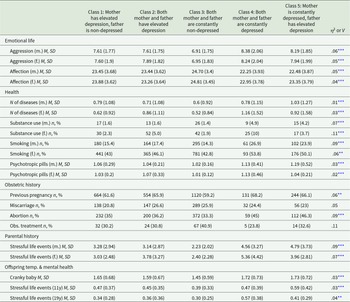

Aggression (mother η 2 = .06, father η 2 = .05) was the least pronounced in Class 3 and the most noticeable in Classes 4 and 5, while affection (mother η 2 = .05, father η 2 = .04) was the strongest in Class 3 and the weakest in Classes 4 and 5 (Table 3). Aggression and affection levels in Classes 1 and 2 were consistently found between Class 3 and Classes 4 and 5. We also found differences in the number of diseases in fathers (η 2 = .03) with the non-depressed Class 3 experiencing the least and the depressed Classes 4 and 5 the greatest number of diseases, while Classes 1 and 2 were found in-between. Similarly, mothers used psychotropic pills the least amount in Class 3 and the most in Classes 4 and 5, while Classes 1 and 2 were in-between (η 2 = .03). Substance use in Class 4 fathers was the most prevalent and in Class 2 the second most prevalent (V = .11). Class 3 parents experienced the least amount of stressful life events and Classes 4 and 5 parents were influenced the most by such events, with Classes 1 and 2 being in-between (mother η 2 = .09, father η 2 = .07). We also found that the non-depressed Class 3 parents evaluated their baby the least cranky (η 2 = .03) and the depressed Classes 4 and 5 evaluated their baby the crankiest, with Classes 1 and 2 in-between. The children of Class 3 were the least influenced by stressful life events at the age of 11 (η 2 = .03) and 19 years (η 2 = .04), while children in Class 5 experienced the most stressful life events at age 11 and Class 4 at age 19.

Table 3. Brown–Forsythe analysis of variance tests and χ 2 tests comparing the five classes along selected parental and offspring characteristics

Note: m = mother, f = father, M = mean, SD = standard deviation, Obs. treatment = obstetric treatment to get pregnant. Temp = temperament.

** p < .01, ***p < .001.

Among relationship maintenance variables only being married later was not a meaningful covariate (Table S10). Demographic data like age, education, town, child’s sex; socio-economic resources like living in own house, needing financial help, income, crowding, the amount of childcare provided by the father, other family and non-family did not differ substantially across the classes. Love of the baby (emotional life covariate) did not correlate with the trajectories either. Obstetric history, such as the number of previous pregnancies, miscarriages or abortions did not differ substantially. Similarly, alcohol use (health covariate) had a negligible association. Temperamental and mental health characteristics of the offspring (apart from a cranky baby), such as internalizing and externalizing problems, self-esteem and satisfaction with life were only negligibly associated with parental depressive symptom trajectories (Tables S11 and S12).

Discussion

We identified five distinct classes of parental depression trajectories. First, mother has elevated depressive symptoms, father is non-depressed; second, both mother and father have elevated depressive symptoms; third, both mother and father are non-depressed; fourth, both mother and father are depressed; and fifth, mother is constantly depressed, father has elevated depressive symptoms. Importantly, the levels of depressive symptoms were maintained during the entire study period from before the birth of the child till the child’s age of 11 years. Further, understandably, we can see a spike in depressive symptoms at newborn age in essentially all the classes. Notably, while the mean latent slope factors were all positive and non-zero, we did not interpret the pace of change due to inconsistent measurement intervals (i.e., prenatal, newborn, 6 months, 18 months, etc.), making it difficult to assess the rate of increase accurately. Comparing the five classes of parents, we found that only some studied characteristics, such as relationship maintenance, some indicators of socio-economic resources, emotional life, health, obstetric history and having a cranky baby were associated with increased levels of depressive symptoms after childbirth in both mothers and fathers. Offspring of more depressed parents were more likely to experience more stressful life events at the ages of 11 and 19 years. Additionally, similar variables were found to be important covariates in the overall sample as across the classes.

Surprisingly, several established socio-demographic and socio-economic risk factors for depression – such as age, education and wealth indicators (home ownership, financial need, income, crowding) – were not associated with parental depressive symptom trajectories in our study, contrasting with prior research (Cermakova and Csajbók, Reference Cermakova and Csajbók2023; McCall-Hosenfeld et al., Reference McCall-Hosenfeld, Phiri, Schaefer, Zhu and Kjerulff2016; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wu and Chen2022). In our study, only deprivation – likely reflecting the experience of poverty – was linked to parental depressive trajectories, suggesting that other wealth-related markers are not meaningful predictors of parents’ depressive symptom development over time. Conversely, we found that the strength of parents’ social network and the support they receive are significant predictors of future depressive symptom trajectories, supporting the view that social support plays a crucial role in mitigating the stressors faced by parents (Escriba-Aguir and Artazcoz, Reference Escriba-Aguir and Artazcoz2011; McCall-Hosenfeld et al., Reference McCall-Hosenfeld, Phiri, Schaefer, Zhu and Kjerulff2016). Contrary to the notion that childcare responsibilities predominantly falling on mothers predict future mental health problems (Serhan et al., Reference Serhan, Ege, Ayrancı and Kosgeroglu2013), our findings do not suggest that childcare provided by others significantly impacts long-term parental depressive trajectories in Czech parents. Perhaps we found this because our measure only indicated the timing and duration of childcare provided instead of the quality and satisfaction with the help received or the associated childcare stress experienced (Ando et al., Reference Ando, Shen, Morishige, Suto, Nakashima, Furui, Kawasaki, Watanabe and Saijo2021; Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Brown and Brennenstuhl2018). Also, since social support and network was a significant alleviating factor, but not directly childcare, it is likely that Czech parents benefit from social support in some aspects other than childcare provision, such as time availability for personal care, emotional support and having adult conversations, exchanging information, or cooking and household maintenance (Chojenta et al., Reference Chojenta, Loxton and Lucke2012; Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Kwasky and Groh2015).

Consistent with previous research (Beach et al., Reference Beach, Katz, Kim and Brody2003; Braithwaite and Holt-Lunstad, Reference Braithwaite and Holt-Lunstad2017), we found that the emotional quality of the relationship between parents – characterized by levels of aggression, affection and various indicators of relationship stability – strongly predicts the development of depressive symptoms. This highlights that intervention techniques such as family therapy improving relationship functioning between mothers and fathers should be a key focus of practical and clinical professionals (Cluxton-Keller and Bruce, Reference Cluxton-Keller and Bruce2018). Notably, the strongest association was found with being separated, emphasizing the significant emotional burden parents face during such challenging life transitions. It is likely that by the time parents divorce or reconcile, many of the difficulties have already been processed during the separation period, which may explain why having experienced a separation is associated with worse outcomes.

Previous studies on couples’ dyadic longitudinal depressive trajectories have either not identified couples where both partners are depressed (Csajbók et al., Reference Csajbók, Štěrbová, Jonason, Cermakova, Dóka and Havlíček2022) or have done so (Volling et al., Reference Volling, Yu, Gonzalez, Tengelitsch and Stevenson2019). In our study, we identified a small group where both mothers and fathers were constantly depressed. Notably, fathers in this group had the highest intercept score, nearly 12, among all classes. This highlights that while women face an elevated risk for depression throughout life (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Tam, Lu, Ho, Zhang and Ho2018), men can also be vulnerable during sensitive periods, such as when caring for young children.

Previous research found a group of couples where women were constantly depressed and men were constantly non-depressed (Csajbók et al., Reference Csajbók, Štěrbová, Jonason, Cermakova, Dóka and Havlíček2022; Pietikäinen et al., Reference Pietikäinen, Kiviruusu, Kylliäinen, Pölkki, Saarenpää‐Heikkilä, Paunio and Paavonen2020; Volling et al., Reference Volling, Yu, Gonzalez, Tengelitsch and Stevenson2019). In our study, we also found couples who were different from each other, but not to such a great extent. In Class 1, women had elevated depressive symptoms and men were non-depressed. In Class 5, women had high depression, and men had elevated depressive symptoms. This is interesting, because couples generally tend to be similar in various traits, including depressiveness (Luo, Reference Luo2017; Nordsletten et al., Reference Nordsletten, Larsson, Crowley, Almqvist, Lichtenstein and Mataix-Cols2016). Surprisingly, while Class 1 formed a stable relationship, Class 5 had an increased risk for dissolution. Class 5 was also deprived, had relatively little support, had worse emotional life and more stressful life events. Thus, the difference between the overall picture of Classes 1 and 5, alarmingly, is more than just 2–4 depression points. Notably, mothers in this group had the highest intercept score, almost 13 points, among all classes.

Similarly to previous studies (Csajbók et al., Reference Csajbók, Štěrbová, Jonason, Cermakova, Dóka and Havlíček2022; Kiviruusu et al., Reference Kiviruusu, Pietikäinen, Kylliäinen, Pölkki, Saarenpää-Heikkilä, Marttunen, Paunio and Paavonen2020; Volling et al., Reference Volling, Yu, Gonzalez, Tengelitsch and Stevenson2019), we also found that most couples are non-depressed, though this proportion is significantly lower postpartum compared to later life. Specifically, 41–42% of parents in both Volling et al. (Reference Volling, Yu, Gonzalez, Tengelitsch and Stevenson2019) and our study reported no elevated depressive symptoms. In Kiviruusu et al. (Reference Kiviruusu, Pietikäinen, Kylliäinen, Pölkki, Saarenpää-Heikkilä, Marttunen, Paunio and Paavonen2020), 63% of mothers and 75% of fathers were constantly non-depressed, while approximately 80% of older couples in Csajbók et al. (Reference Csajbók, Štěrbová, Jonason, Cermakova, Dóka and Havlíček2022) fell into this category. This figure is alarming and highlights the vulnerability of families with small children in Czechia. Additionally, other studies identified groups of mothers and/or couples with either decreasing or increasing depressive symptoms (Baron et al., Reference Baron, Bass, Murray, Schneider and Lund2017; Csajbók et al., Reference Csajbók, Štěrbová, Jonason, Cermakova, Dóka and Havlíček2022). We did not find such a dynamic change in depressive symptoms except for the spike around the birth of the child. The lack of alleviating effects is worrisome and indicates that these couples are dealing with pervasive and persistent problems, as our data indicated no noticeable improvement over at least 11 years. Future research should explore why depressive symptoms remain stable (though not worsening) in Czech families with young children.

Findings are in accordance with the social risk hypothesis that posits that depressed mood is part of an adaptive strategy that protects the individual from acting dangerously and losing more social capital than one can afford (Allen and Badcock, Reference Allen and Badcock2003). Caring for young and dependent offspring requires significant psychological and physical investment from both mothers and fathers (Trivers, Reference Trivers and Campbell1972). This investment is especially critical for parents in particularly vulnerable positions, such as the parents of Classes 4 and 5. It follows that these more depressed parents have fewer resources and privileges to draw upon, leading them to respond with depressive symptoms as an evolutionarily developed strategy. The associated covariates and outcomes of depressive trajectories, such as relationship and emotional problems, socio-economic deprivation, substance abuse and offspring mental health likely have a complex interplay among them (e.g., Amendola et al., Reference Amendola, Hengartner, Ajdacic-Gross, Angst and Rössler2022; Boardman et al., Reference Boardman, Finch, Ellison, Williams and Jackson2001; Ettekal et al., Reference Ettekal, Eiden, Nickerson, Molnar and Schuetze2020; Whisman, Reference Whisman2007). While it is more likely that marital distress is causing depressive symptoms, living with a depressed partner is also negatively affecting marital quality (Coyne, Reference Coyne1976; Gariépy et al., Reference Gariépy, Honkaniemi and Quesnel-Vallée2016; Whisman and Bruce, Reference Whisman and Bruce1999). Thus, while depressed mood serves important functions in a person’s life, professionals need to apply a nuanced and complex approach when helping families in need.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study was that all families with a child born in Brno and Znojmo between 1991 and 1992 were invited to participate, and these families were very closely monitored essentially throughout the child’s life. Further, instead of simply correlating depression measures with various covariates, we could identify mothers and fathers who specifically experienced elevated or high depressive symptoms postpartum, focusing on estimating combined trajectories of the dyads. Based on this analysis, we showed that not only high depression, but elevated depressive symptoms could be a sign of relational and socio-economic hardship and an indicator of need for help. Several limitations need to be mentioned. There were missing data and a high attrition in the offspring data at ages 18 and above. Some of the covariates, such as smoking status, were also measured on an overly simplistic scale, thus limiting how much variance they could capture as a function of depressive symptoms. We had limited overlapping mental health data coming from both offspring and parents (only from the age of 11 years), which limits the predictive power of parental depression trajectories on children’s mental health outcomes. Future research should aim to gather longitudinal data that includes parallel assessments of all family members and to perform detailed psychometric analysis, including longitudinal measurement invariance testing of the depressive symptoms scale.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796025000174.

Availability of data and materials

Access to the data is provided free of charge to researchers upon reasonable request. More information can be found on this website: elspac.cz. The study protocol and syntax of the statistical analysis will be shared upon request from the corresponding author of this study.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Zsófia Csajbók: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft. Jakub Fořt: Writing – Original Draft. Pavla Brennan Kearns: Data curation, Writing – Original Draft.

Financial support

Z.C., J.F., and P.B.K. were supported by the Czech Science Foundation (23-05379S).

Competing interests

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.