It is an interesting phenomenon within Outsider Art (Art Brut) and psychopathology of expression that several artists have made their own banknotes. Four of them are portrayed here and possible backgrounds of this work are presented.

Raimundo Camilo was born in the state of Ceará in north-eastern Brazil in 1939 or 1943, depending on the source (Fig. 1). He left his home region at an early age to work in Rio as a ‘slave’, as the Brazilian expression has it, taking menial jobs in places like building sites and kitchens.

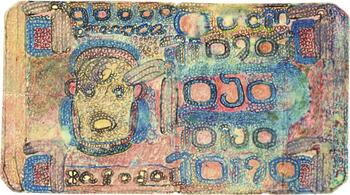

Fig. 1. Raimundo Camilo (b. 1939), Untitled, u.d. (around 2000), coloured pencil, graphite and pen ball on paper, 2.9 × 6.1 inches, private collection.

He broke off from his previous life as a result of one of these jobs: when an employer failed to pay him his due, he was forced to begin eking out a precarious existence on the streets of Rio. Camilo was hospitalised for almost 50 years in a psychiatric service called ‘Instituto Municipal de Assistência à Saúde Mental Juliano Moreira’ in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) because of schizophrenia. (For the history of art therapy in this institution, see de Araújo and Jacó-Vilela, Reference de Araújo and Jacó-Vilela2018.) He now lives in Ceará with his sister. Haunted by his past difficulties, Camilo began kneeling by his bed to draw his own banknotes. He uses whatever media is available, from paper packaging to administrative forms. He makes his own colours using materials like coffee. The head on the front of the banknotes represents either a king or a cangaceiro bandit, a bandit folk hero. Camilo likes to hand out his banknotes to his favourite hospital staff members, especially women. He claims not to be producing art, but rather doing his ‘job’.

The Brazilian cultural authorities have become increasingly aware of the significance of his creations in recent years, and they have been featured in several exhibitions and a catalogue (Museu Oscar Niemeyer, 2005). His works have recently been acquired by the Lille Métropole Museum of Modern, Contemporary and Outsider Art.

Pearl Blauvelt's (1893–1987) drawings, discovered by chance, date from the 1940s and 1950s (Fig. 2). During the restoration of an early 19th century post-and-beam house in a remote Pennsylvania village, Corrigan and Corrigan (Reference Corrigan and Corrigan2003) found a leather-hinged wooden box overflowing with seemingly worthless note paper.

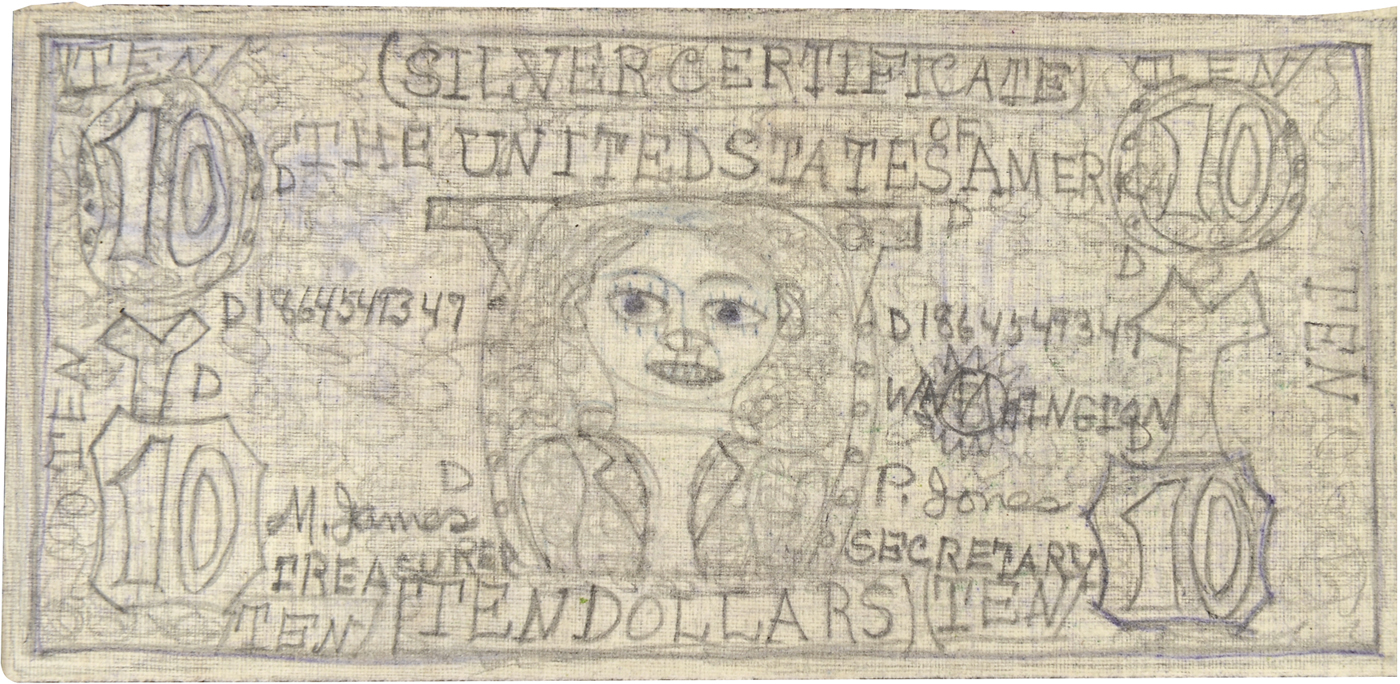

Fig. 2. Pearl Blauvelt (1893–1987), Untitled, u.d. (around 1940), coloured pencil and graphite on paper, 2.8 × 5.7 inches, private collection.

The house had been unoccupied for nearly 50 years. The last occupant had lived there without running water, plumbing or central heating. After numerous interviews with local villagers, buyers discovered that Pearl Blauvelt, still referred to by some residents as the ‘Village Witch’, had occupied the house from the early part of the 20th century until the 1950s. She was declared incompetent and moved to a nearby assisted-living facility, where she stayed until her death in the 1970s.

Closer examination revealed the significance of the Corrigan's discovery: the box contained more than 800 drawings [some integrated now in the Museum of Modern Art, New York (see Graw and Rattemeyer, Reference Graw and Rattemeyer2009)]. She appropriated imagery from shopping catalogues and illustrated furniture, clothing and architecture from her everyday life. Blauvelt drew using her own flattened perspective and organised her selections through careful classifications, enhanced by a methodical layering of line. With imaginary X-ray vision, Blauvelt revealed a world where knee bones are visible through pants and a building's rear windows can be spied through the brick façade. In the drawings there are some astounding moves: houses are transparent – clothes and the body as well – perspective is reversed, scale highly skewed. She flattens interior walls so that all are visible at the same time, as if seen from above. There is text in most of the drawings, and she often identifies every single object – each rug, each pair of stockings and so on – possibly an indication that she was copying images from mail order catalogues.

Several of the drawings were laced together with shoestrings in primitive book form. Others were contained in dime-store notepads and old school composition books. Many images were drawn on brown paper bags or other loose scraps of paper. One of the notebooks revealed Blauvelt's fascination with currency: numerous pieces of cut paper feverishly rendered on both sides depict American, Canadian and Confederate bills in fantasy denominations of $30, $125 etc. and were stuffed inside a notebook containing other uncut examples.

Else Blankenhorn (1873–1920) grew up in a southern German bourgeois family, and was active culturally and socially. She played the piano and sang until she lost her voice at age 26, the result of neurasthenia. Later, she suffered from hypochondria, then nightmares. From 1899 to 1902, and from 1906 to 1919, she was hospitalised in the famous private psychiatric hospital ‘Sanatorium Bellevue’ (of the Binswanger psychiatrist dynasty) in Kreuzlingen (Lake of Constance, Switzerland). Her gouache works are scenes from her imaginary life, in which her alter ego lived with Emperor Wilhelm II as his spiritual wife ‘Else von Hohenzollern’.

A central focus of her artistic work was the production of ‘banknotes’, featuring flowers and her angelic image in multiples. These notes were to finance the renewed earthly existence of (buried but not dead) couples Blankenhorn hoped to help resurrect with high sums of money. Thus, the notes painted with Indian ink have a value of many billions (‘die Erlösung beerdigter, aber nicht verstorbener Paare finanzieren’). She attempted to realise this conceptual task through her symbolic notation system. The cause of her excessive production of works was presumably that the emperor (William II, to whom she had developed a love mania), assigned this as her life's mission. This mission also mirrored Blankenhorn's concern in reaction to news about the First World War. In her large phantasmagoriac realm, ‘Empress Else of Germany’ ruled in anticipation of the Emperor. Tragically, she was moved to the ‘Badische Heil-und Pflegeanstalt’ (Baden Mental Hospital) of Reichenau (near Constance), where she died of stomach cancer in November 1920 (see Noell-Rumpeltes, Reference Noell-Rumpeltes, Jagfeld and Dammann2013).

(For an example of banknotes by Else Blankenhorn see: https://www.outsiderartmuseum.nl/en/kunstenaars/else-blankenhorn-2/).

Another important outsider artist making bills in the hospital was the French Georgine Hu (1939–2007) (see Mons Reference Mons1990). Hu had a terrible family history. One of seven children of an alcoholic father, who presumably raped her, and a helpless mother, she was first hospitalised at age 14. Just three years later, she was institutionalised in the psychiatric hospital of Saint-Venant (Département Pas-de-Calais, Northern France).

Her work is divided into two parts. One is mainly cities, images inspired by newspaper clippings, with representations of animals or human figures. The other consists of a series of banknotes drawn on toilet paper. Hu represented it as a historical figure or royal effigy. Like kings, she made money. To her, these notes had a real exchange value, which is why she distributed them to the hospital staff.

The amounts on the bills of Georgine Hu range from 50 to 50 000 000. The name ‘bank’ (French ‘banque’) can be recognised, but in very disturbed expression, indicating formal thought disorders (see Dammann et al., Reference Dammann, Schroeder and Röske2013): 10 Bancuercquer 10, B8anccercsquercs, Baaeurcquercs debet, Bakcuerdqoirest, Ban c de France, Ban cquercs, Bancecque, Banceoecques, Bancercquercsc, Bancerequerscdefran, Banceucoueroque or Banceuerccquerys.

Bills by Georgine Hu are conserved in the national museum for modern art ‘Lille Métropole Musée d'art moderne, d'art contemporain et d'art brut (LaM)’ in Villeneuve-d'Ascq, near the city of Lille, France (originating from the artist collection ‘L'Aracine’). They are also in private collections, such as the abcd of Bruno Decharme (Montreuil/France).

(See examples of these bills: http://abcd-artbrut.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/HU.Georgine.401.6.billets.jpg).

Why might outsider artists not only create drawings and paintings, but also bills?

There may be many reasons why persons with psychotic disorders hospitalised in psychiatric hospitals (Raimundo Camilo, Georgine Hu, Else Blankenhorn) made their own bills.

It is clear that patients in psychiatric hospitals typically do not have money or are poor; in many countries, psychiatric patients beg in the hospital areas. Making their own bills could be interpreted as an attempt to escape poverty. But this is not true for Else Blankenhorn, a member of a very wealthy German family with her own maid.

Another possible psychiatric explanation may be megalomania (or delusions of grandeur), a classic symptom of some patients with schizophrenic illness.

Megalomania is a subtype of delusion that occurs in patients suffering from a wide range of psychiatric diseases, including two-thirds of patients in a manic state of bipolar disorder, half of those with schizophrenia, patients with the grandiose subtype of delusional disorder, and a substantial portion of those with substance abuse disorders and narcissistic personality disorders. Grandiose delusions are characterised by fantastical beliefs that one is famous, omnipotent, wealthy or otherwise very powerful (Knowles et al., Reference Knowles, McCarthy-Jones and Rowse2011). In a psychodynamic view, grandiose delusions have some positive functions and may be seen as defense against feelings of inferiority, low self-esteem and depression (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Freeman and Kuipers2005).

Even more interesting, from a psychological point of view, is the fact that Georgine Hu used toilet paper for her bills and, perhaps in a subtle form of aggression, paid her psychiatrist (Mons, Reference Mons1990) with this ‘dirty’ money. It illustrates the psychodynamic link between money and anality.

We find the limits of scatological creativity in certain Art Brut creations of the mentally ill. Note the work of Georgine Hu (found in the museum l'Aracine) … Her art consists of false banknotes created on toilet paper, with which she often attempted to pay her psychiatrist! Here, the scatological significance of money, the link between excrement and filthy lucre, is symbolized in a desublimated creativity, where the black humor and irony of the situation call into question both the economic and psychological aspects of creativity as well as psychiatric endeavors. (Weiss, Reference Weiss1992, p. 11)

While the works of Raimundo Camilo, Georgine Hu and Else Blankenhorn are very unique artistic creations, only remotely reminiscent of real banknotes, Pearl Blauvelt's bills are much more realistic, integrating some elements (e.g. green colour) of official American bills. Additionally, the bills of Georgine Hu, Pearl Blauvelt and Else Blankenhorn are remarkable because the portraits of the banknote show self-assured, female faces. One possible hypothesis is that these are adapted self-portraits, portraying themselves as important figures.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

None.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

None.

About the Author

Gerhard Dammann, MD, MSc, MA, MBA, is a psychiatrist, clinical psychologist and a psychoanalyst (IPA). He is director of the Psychiatric Hospital of Münsterlingen (founded 1839) at the border of the Lake of Constance in Switzerland. He is Privatdozent for psychiatry and psychotherapy at the Medical University of Salzburg and Honorary Professor. His clinical and scientific areas of interest are the diagnosis and psychotherapy of severe personality disorders. He collects outsider art together with his wife, and has written about psychopathology of expression.