Introduction

Social anxiety disorder, a prevalent yet often overlooked mental disorder, is characterized by an intense fear of embarrassment, rejection, or humiliation in social or public settings, driven by the anticipation of negative evaluation by others (Liebowitz et al., Reference Liebowitz, Gorman, Fyer and Klein1985; Nagata et al., Reference Nagata, Suzuki and Teo2015; Salari et al., Reference Salari, Heidarian, Hassanabadi, Babajani, Abdoli, Aminian and Mohammadi2024). Social anxiety disorder is a chronic condition that usually manifests in childhood or early adolescence and has a negative effect on social interactions, academic performance, and professional functioning in both children and adults (Liebowitz et al., Reference Liebowitz, Gorman, Fyer and Klein1985; Nagata et al., Reference Nagata, Suzuki and Teo2015; Salari et al., Reference Salari, Heidarian, Hassanabadi, Babajani, Abdoli, Aminian and Mohammadi2024). Global field studies have estimated that social anxiety disorder affects 4.7% of children, 8.3% of adolescents, and 17% of young adults (Salari et al., Reference Salari, Heidarian, Hassanabadi, Babajani, Abdoli, Aminian and Mohammadi2024). Despite its prevalence, only a small proportion of individuals with social anxiety disorder seek mental consultation or treatment, often delaying seeking assistance until they develop comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as major affective disorders (Liebowitz et al., Reference Liebowitz, Gorman, Fyer and Klein1985; Nagata et al., Reference Nagata, Suzuki and Teo2015).

Growing evidence has established a strong association between social anxiety disorder and suicidal symptoms, including suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Lemke, Jeffries and Shah2017; Leigh et al., Reference Leigh, Chiu and Ballard2023; Thibodeau et al., Reference Thibodeau, Welch, Sareen and Asmundson2013). The National Comorbidity Survey Replication and the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions revealed that individuals with social anxiety disorder had significantly higher odds of experiencing lifetime suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR], 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.09, 1.68–2.60; 1.72, 1.58–1.87) and suicide attempts (OR, 2.70, 95% CI: 1.93–3.79; 1.62, 1.42–1.85), irrespective of comorbid major affective disorders, alcohol use disorder (AUD), and substance use disorder (SUD) (Thibodeau et al., Reference Thibodeau, Welch, Sareen and Asmundson2013). Buckner et al. further identified an indirect link between social anxiety disorder and suicidal ideation, mediated by feelings of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, in line with the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Lemke, Jeffries and Shah2017). A meta-analysis of 16 cross-sectional and prospective studies similarly demonstrated that social anxiety disorder was associated with lifetime suicide attempts (r = 0.10, 95% CI: 0.04–0.15) and current suicidal ideation (r = 0.22, 95% CI: 0.02–0.41) (Leigh et al., Reference Leigh, Chiu and Ballard2023). Despite these findings, research has yet to explore the relationship between social anxiety disorder and suicide mortality.

This study obtained data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which comprises data for the entire population of Taiwan (n = 29,077,426), and compared the risk of suicide among patients with social anxiety disorder to that of individuals without social anxiety disorder. Furthermore, the effects of social anxiety disorder-related psychiatric comorbidities, such as bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and autism, on suicide risk were evaluated. The primary hypothesis was that social anxiety disorder serves as an independent risk factor for suicide mortality, irrespective of the presence of these psychiatric comorbidities. Furthermore, we hypothesized that patients with social anxiety disorder who also presented with additional psychiatric comorbidities exhibited the highest suicide risk.

Methods

Data source

The Health Data Science Center of the Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare audits and makes available for research purposes the NHIRD, which includes comprehensive healthcare data on almost 99.7% of Taiwan’s population. To protect individual privacy, individual medical records are kept anonymous in the NHIRD. We linked the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database of the NHIRD, which contains all medical records from 2003 to 2017 of the entire Taiwanese population, and the Database of All-cause Mortality, which includes all-cause mortality records from 2003 to 2017 of the entire Taiwanese population, to analyse the suicide risk among people with social anxiety disorder. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth or Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification is used in Taiwanese clinical practice (ICD-9-CM [2003–2014] or ICD-10-CM [2015–2017]). Since deidentified data were utilized in this study and no individuals were actively enrolled, the Taipei Veterans General Hospital’s institutional review board authorized the study methodology and waived the need for informed consent. The NHIRD has been used in numerous epidemiological studies in Taiwan (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Su, Chen, Hsu, Huang, Chang and Bai2013; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chang, Chen, Tsai, Su, Li, Tsai, Hsu, Huang, Lin, Chen and Bai2018; Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Liang, Tsai, Bai, Su, Chen and Chen2023; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Bai, Tsai, Su, Chen, Wang and Chen2021).

Inclusion criteria for individuals with and without social anxiety disorder

This study was a matched retrospective cohort study, and individuals who were diagnosed with social anxiety disorder (the exposed group) were matched to those without social anxiety disorder (the unexposed group). Specifically, the individuals in the social anxiety disorder group were those who had at least two diagnoses of social anxiety disorder (ICD-9-CM code: 300.23 or ICD-10-CM code: F41.1) from board-certified psychiatrists (Fig. 1). A 1:4 exposed and unexposed groups-matched analysis based on birth year and sex was carried out to reduce the confounding effects of age and sex. The unexposed group was selected at random from the entire Taiwanese population after all people who had ever been diagnosed with social anxiety disorder were removed from the database (Fig. 1). In Taiwan, levels 1–4, which represent the most to least urbanized residential areas, were evaluated as a proxy for the availability of healthcare (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Hung, Chuang, Chen, Weng and Liu2006). The income and urbanicity levels were defined using the most recent data of all individuals. The social anxiety disorder diagnosis was regarded as a time-dependent variable. The time zero was defined as 1 January 2003, for those who were born before 2003 and was defined as the birthdates for those who were born ≥2003, respectively. Suicide was identified between 2003 and 2017 from the Database of All-cause Mortality. For patients with social anxiety disorder and matched individuals without social anxiety disorder, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) values were calculated during the study period. Every enrolled subject’s systemic health state was determined by evaluating the 22 physical conditions that make up the CCI (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie1987). Furthermore, we further assessed social anxiety disorder-related psychiatric comorbidities with suicide risk, including schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM code: 295 or ICD-10-CM code: F20, F25), bipolar disorder (ICD-9-CM codes: 296 except 296.2, 296.3, 296.9, and 296.82 or ICD-10-CM codes: F30, F31), major depressive disorder (ICD-9-CM codes: 296.2, 296.3, 300.3, 311 or ICD-10-CM codes: F32, F33, F34), OCD (ICD-9-CM code: 300.3 or ICD-10-CM code: F42), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (ICD-9-CM code: 314 or ICD-10-CM code: F90), autism (ICD-9-CM codes: 299.0, 299.8, 299.9 or ICD-10-CM codes: F84.0, F84.5, F84.8, F84.9), AUD (ICD-9-CM codes: 291, 303.0, 303.9, 305.0 or ICD-10-CM code: F10), and SUD (ICD-9-CM codes: 292, 304, 305 except 305.0 and 305.1 or ICD-10-CM codes: F11, F12, F13, F14, F15, F16, F18, F19) during the study period, because those comorbid psychiatric disorders are also associated with suicide risk. The study period was defined from 1 January 2003, or birthdates, to 31 December 2017, or death. These psychiatric disorders were diagnosed at least twice by board-certified psychiatrists. Finally, given that increasing the number of people in the comparison improved the statistical power, following the same procedure mentioned above to select the unexposed group, we additionally performed a sensitivity analysis using a 1:10 exposed and unexposed groups-matched analysis to reconfirm our findings (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Study flowchart.

Statistical analysis

For between-group comparisons in grouping data, we employed conditional logistic regressions for nominal variables and repeated measure analyses of variance with general linear models for continuous variables. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI of subsequent suicide between groups were determined using time-dependent Cox regression models with adjustments for sex, birth year, income, level of urbanization, psychiatric comorbidities, and CCI. We investigated the effects of psychiatric comorbidities, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, autism, ADHD, OCD, AUD, and SUD, on the suicide risk among people with social anxiety disorder in comparison to the unexposed group using Cox regression models with adjustments for sex, birth year, income, levels of urbanization, and CCI. The proportional hazards assumptions were verified using the log-minus-log plots, resulting in no considerable violation. Finally, given that social anxiety disorder is a female-predominant mental condition (Liebowitz et al., Reference Liebowitz, Gorman, Fyer and Klein1985; Nagata et al., Reference Nagata, Suzuki and Teo2015; Salari et al., Reference Salari, Heidarian, Hassanabadi, Babajani, Abdoli, Aminian and Mohammadi2024), sex-stratified analyses were performed in the present study. A two-tailed p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data processing and statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis Software Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The current study identified 15,776 patients with social anxiety disorder, matching their birth year and sex to 63,104 (1:4 unexposed cohort) and 157,760 (1:10 unexposed cohort) individuals, respectively (Table 1). Of the patients with social anxiety disorder, 1534 (9.72%) had co-occurring schizophrenia, 1490 (9.44%) had bipolar disorder, 9112 (57.76%) had major depressive disorder, 1588 (10.07%) had OCD, 651 (4.13%) had autism, 1571 (9.96%) had ADHD, 316 (2.00%) had AUD, and 381 (2.42%) had SUD (Table 1). Rates of all co-occurring mental disorder diagnoses were significantly higher in the social anxiety disorder group than in the two unexposed groups (Table 1). Patients with social anxiety disorder had higher CCI scores, resided in the more urban area, and had higher income than the two unexposed groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients with social anxiety disorder and matched individuals

OCD: obsessive compulsive disorder; USD: United State dollar; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AUD: alcohol use disorder; SUD: substance use disorder.

Adjusting for sex, birth year, income, level of urbanization, psychiatric comorbidities, and CCI, patients with social anxiety disorder were more likely (HR, 95% CI) to die by suicide than the two unexposed groups, specifically 3.49 (2.02–6.03) in the 1:4 exposed and unexposed groups-matched analysis and 2.84 (1.94–4.17) in the 1:10 exposed and unexposed groups-matched analysis (Table 2).

Table 2. Suicide risk between patients with social anxiety disorder and matched individuals

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index.

# adjusting for sex, birth year, income, level of urbanization, psychiatric comorbidities and CCI.

Bold type indicates the statistical significance.

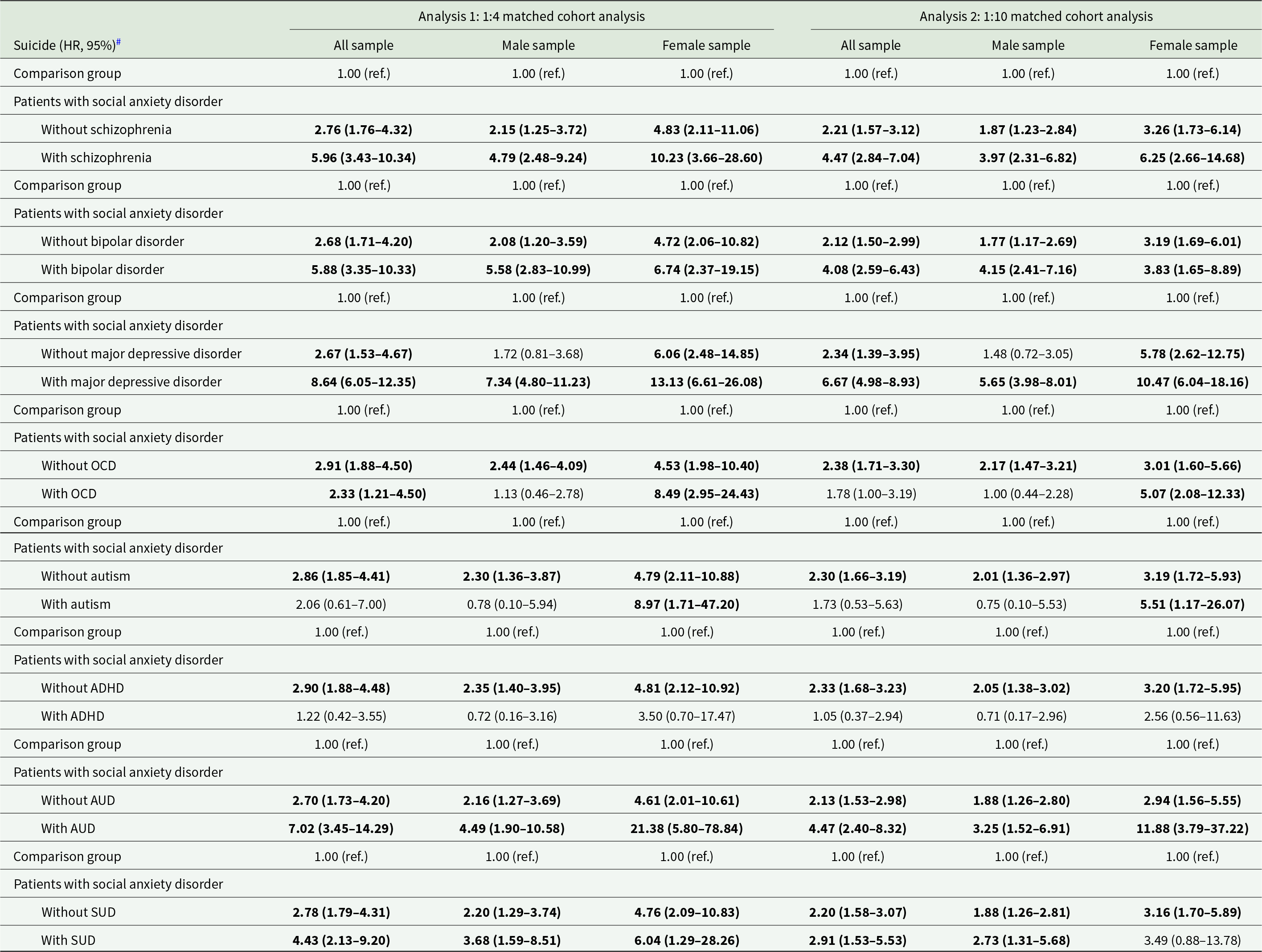

Lastly, we evaluated the additional psychiatric comorbidities associated with social anxiety disorder in relation to the suicide risk (Table 3). Both the 1:4 exposed and unexposed groups-matched and 1:10 exposed and unexposed groups-matched analyses revealed a higher risk of suicide death among patients with social anxiety disorder who had schizophrenia (5.96, 3.43–10.34; 4.47, 2.84–7.04), bipolar disorder (5.88, 3.35–10.33; 4.08, 2.59–6.43), major depressive disorder (8.64, 6.05–12.35; 6.67, 4.98–8.93), AUD (7.02, 3.45–14.29; 4.47, 2.40–8.32), or SUD (4.43, 2.13–9.20; 2.91, 1.53–5.53) compared with those without corresponding psychiatric comorbidities (Table 3). Furthermore, only females with social anxiety disorder who were comorbid with OCD (8.49, 2.95–24.43; 5.07, 2.08–12.33) and autism (8.97, 1.71–47.20; 5.51, 1.17–26.07) had a higher suicide risk compared with those without OCD and autism (Table 3).

Table 3. Suicide risk between patients with social anxiety disorder with different psychiatric comorbidities and matched individuals

OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AUD: alcohol use disorder; SUD: substance use disorder.

# Separate Cox regression models with adjustment of sex, birth year, income, level of urbanization, and CCI.

Bold type indicates the statistical significance.

Discussion

The study findings supported the hypothesis that patients with social anxiety disorder had a higher likelihood of dying by suicide than did those without social anxiety disorder, independent of comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, major affective disorders, AUD, and SUD. Additionally, comorbid schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, AUD, and SUD further increased the risk of suicide among patients with social anxiety disorder.

Substantial evidence has demonstrated an association between social anxiety disorder and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, independent of comorbid major psychiatric disorders (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Lemke, Jeffries and Shah2017; Leigh et al., Reference Leigh, Chiu and Ballard2023; Thibodeau et al., Reference Thibodeau, Welch, Sareen and Asmundson2013). This suggests that core symptoms of social anxiety disorder play a crucial role in suicidality (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Stringaris and Leigh2024; Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Prinstein, Simon and Spirito2014). A prospective study was conducted on 2,397 adolescents aged 14–24 years to assess symptoms of social anxiety disorder, depression, and suicidal ideation at baseline and follow-up. The results revealed that baseline social anxiety disorder symptoms were associated with suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms 2 years later (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Stringaris and Leigh2024). Buckner et al. indicated a pivotal role of perceived burdensomeness in the association between social anxiety and suicidal ideation, particularly among individuals experiencing increased thwarted belongingness (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Lemke, Jeffries and Shah2017). This may indicate that a vicious cycle of social frustration and subsequent social dyscognition fosters the development of suicidal symptoms. In a clinical study, 144 adolescents were evaluated for social anxiety disorder, depression, suicidal ideation, and loneliness during psychiatric hospitalization, with follow-up assessments at 9 and 18 months (Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Prinstein, Simon and Spirito2014). Gallagher et al. identified a direct link between social anxiety symptoms at baseline and suicidal ideation at the 18-month follow-up after baseline depressive symptoms and ideation were controlled for (Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Prinstein, Simon and Spirito2014). Additionally, they demonstrated that loneliness at the 9-month follow-up mediated this relationship (Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Prinstein, Simon and Spirito2014). Rapp et al. noted a direct association between social anxiety disorder and active suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, particularly among ethnic minorities (Rapp et al., Reference Rapp, Lau and Chavira2017). A combined analysis of two community-based family studies, namely the National Institute of Mental Health study and the Cohort Study of Lausanne, revealed that social anxiety disorder in probands was associated with suicide attempts in first-degree relatives (OR: 2.4; 95% CI: 1.7–3.5), even after adjustment for comorbid affective disorders and SUD (Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Cui, Vandeleur, Castelao, Zarate, Preisig and Merikangas2019). Ballard et al. reported a familial coaggregation of social anxiety disorder and suicide attempts, indicating a genetic overlap between two conditions (Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Cui, Vandeleur, Castelao, Zarate, Preisig and Merikangas2019). Our study is the first to identify social anxiety disorder as an independent risk factor for suicide, regardless of the major psychiatric comorbidities.

Despite the passage of time, social anxiety disorder remains underrecognized in both clinical and nonclinical settings (Liebowitz et al., Reference Liebowitz, Gorman, Fyer and Klein1985; Nagata et al., Reference Nagata, Suzuki and Teo2015), which may partly account for the relatively small number of individuals identified with social anxiety disorder in this study (n = 15,776). Patients with social anxiety disorder often delay seeking mental health support and treatment until they develop comorbid psychiatric disorders (Liebowitz et al., Reference Liebowitz, Gorman, Fyer and Klein1985; Nagata et al., Reference Nagata, Suzuki and Teo2015; Salari et al., Reference Salari, Heidarian, Hassanabadi, Babajani, Abdoli, Aminian and Mohammadi2024). This could explain why, in the present study, more than three-quarters of individuals with social anxiety disorder also had other major psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, AUD, and SUD. Given this high rate of comorbidity, we infer that conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, AUD, and SUD further elevated the risk of suicide among individuals with social anxiety disorder in the present study (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Lemke, Jeffries and Shah2017; Leigh et al., Reference Leigh, Chiu and Ballard2023; Thibodeau et al., Reference Thibodeau, Welch, Sareen and Asmundson2013).

Interestingly, we observed that female but not males with social anxiety disorder and OCD or autism exhibited an elevated suicide risk. Research has demonstrated that females with autism often exhibit more severe autistic symptoms, particularly in social interaction and cognition, than do males with autism (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Amestoy, Bishop, Brown, Giwa Onaiwu, Halladay, Harrop, Hotez, Huerta, Kelly, Miller, Nordahl, Ratto, Saulnier, Siper, Sohl, Zwaigenbaum and Goldman2023). Another of our studies similarly indicated that females with autism (HR: 4.30, 95% CI: 2.54–7.25) had a higher risk of unnatural-cause mortality, including suicide, than did males with autism (2.06, 1.62–2.63) (Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Chang, Cheng, Liang, Bai, Hsu, Huang, Su, Chen and Chen2023). Additionally, studies reported a positive correlation between symptoms of social anxiety disorder and autism (Gaziel-Guttman et al., Reference Gaziel-Guttman, Anaki and Mashal2023; Montaser et al., Reference Montaser, Umeano, Pujari, Nasiri, Parisapogu, Shah and Khan2023), suggesting that females with autism experience more severe social anxiety disorder symptoms than do males with autism. The combined effects of autism and social anxiety may be more pronounced in female than in males (Gaziel-Guttman et al., Reference Gaziel-Guttman, Anaki and Mashal2023; Montaser et al., Reference Montaser, Umeano, Pujari, Nasiri, Parisapogu, Shah and Khan2023; Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Chang, Cheng, Liang, Bai, Hsu, Huang, Su, Chen and Chen2023), which may explain why only females with autism with social anxiety disorder exhibited an elevated risk of suicide in the present study. Furthermore, Asher et al. and Mathes et al. reported that females with social anxiety disorder or OCD exhibited more severe clinical presentations and experienced greater subjective distress compared with their male counterparts (Asher and Aderka, Reference Asher and Aderka2018; Mathes et al., Reference Mathes, Morabito and Schmidt2019). Asher et al. also revealed that males with social anxiety disorder were more likely to seek treatment than were females (Asher and Aderka, Reference Asher and Aderka2018). These findings echo our finding of an increased risk of suicide among female but not males with social anxiety disorder and OCD. However, although there were significant differences in HRs between males and females in the subgroups of patients with social anxiety disorder with or without autism or OCD, the 95% CIs still overlapped, which may limit the conclusion of the gender differences in such subgroups. Further studies would be required to elucidate the role of genders in associations between additional psychiatric comorbidities (i.e., autism, OCD) with social anxiety disorder and suicide.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the prevalence of social anxiety disorder may have been underestimated. As noted, social anxiety disorder continues to be widely overlooked in both clinical and nonclinical settings. Additionally, the NHIRD only includes individuals who sought medical consultation and treatment, potentially reflecting a population with more severe clinical presentations. Further research is necessary to determine whether our findings can be generalized to individuals with milder symptoms of social anxiety disorder. Second, in the present study, social anxiety disorder was diagnosed by board-certified psychiatrists at least twice, which increased the diagnostic validity of social anxiety disorder. However, the NHIRD did not have an exact algorithm used to identify cases of social anxiety disorder, which may lead to the possibility of the misclassification. Further cohort studies using the face-to-face diagnostic interview would be necessary to validate our findings. Third, the NHIRD lacks data on psychosocial and environmental factors, personal lifestyle choices, and childhood experiences. The absence of these variables limits our ability to assess their potential effect on the relationship between social anxiety disorder and suicide risk.

In conclusion, patients with social anxiety disorder were at a higher risk of suicide than were those without, regardless of the presence of major psychiatric comorbidities, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, AUD, and SUD. These comorbidities further increased the risk of suicide among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Notably, autism and OCD increased suicide risk only among females with social anxiety disorder. Mental health professionals and clinicians should prioritize suicide prevention strategies tailored to individuals with social anxiety disorder, particularly those with comorbid major psychiatric disorders.

Availability of data and materials

The Department of Health and the Bureau of the NHI Program provided and audited the NHIRD with the intention of using it for scientific study (https://www.apre.mohw.gov.tw). Through a formal application that is governed by the Health Data Science Center of the Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, one can access the NHIRD.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. I-Fan Hu, MA (Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London; National Taiwan University) for his friendship and support.

Author contributions

Drs MHC, SJT, and HTW designed the study and drafted the paper; Drs MHC and CMC and Ms WHC analysed the data; Drs SJT, YMB, CMC, TPS, TJC performed the literature review and critically reviewed the manuscript and interpreted the data; All authors contributed substantially to the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript for submission. All authors are responsible for the integrity, accuracy and presentation of the data.

Financial support

The study was supported by grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V113C-039, V113C-011, V113C-010, V114C-089, V114C-064, V114C-217); Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation (CI-113-32, CI-113-30, CI-114-35); Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST111-2314-B-075-014-MY2, MOST 111-2314-B-075-013, NSTC113-2314-B-075-042); Taipei, Taichung, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Tri-Service General Hospital, Academia Sinica Joint Research Program (VTA112-V1-6-1, VTA114-V1-4-1); Veterans General Hospitals and University System of Taiwan Joint Research Program (VGHUST112-G1-8-1, VGHUST114-G1-9-1); and Cheng Hsin General Hospital (CY11402-1, CY11402-2). The funding source had no role in any process of our study. All authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Competing interests

All authors declared no conflict of interest. Mr. Hu declares no conflicts of interest.