Introduction

Self-harm, increasingly acknowledged as a major public health concern (Borschmann et al., Reference Borschmann, Young, Moran, Spittal and Kinner2018; Pilling et al., Reference Pilling, Smith, Roth, Sherrat, Monnery, Boland, Lawes and Furmaniak2018; The Lancet Public, 2018; Ayre et al., Reference Ayre, Dutta and Howard2019), is a key area in the national suicide prevention strategies of many countries and is a priority area in the Mental Health Gap Action Programme produced by the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2008). People who self-harm are at elevated risk of premature death (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Harriss and Zahl2006; Bergen et al., Reference Bergen, Hawton, Waters, Ness, Cooper, Steeg and Kapur2012; Carr et al., Reference Carr, Ashcroft, Kontopantelis, While, Awenat, Cooper, Chew-Graham, Kapur and Webb2017), especially by suicide (i.e. death by intentional self-harm) (Bergen et al., Reference Bergen, Hawton, Waters, Ness, Cooper, Steeg and Kapur2012; Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Metcalfe and Gunnell2014; Olfson et al., Reference Olfson, Wall, Wang, Crystal, Bridge, Liu and Blanco2018), and poor mental health, including depression and substance abuse (Da Cruz et al., Reference Da Cruz, Pearson, Saini, Miles, While, Swinson, Williams, Shaw, Appleby and Kapur2011; Mars et al., Reference Mars, Heron, Crane, Hawton, Lewis, Macleod, Tilling and Gunnell2014; Borschmann et al., Reference Borschmann, Becker, Coffey, Spry, Moreno-Betancur, Moran and Patton2017).

In England, prevention of self-harm and suicide is a priority area in public health policy, being the focus of national strategy and clinical guidelines (NICE, 2011; UK Government, 2012, 2019). It was highlighted as a key issue in its own right when the national suicide prevention strategy in England was updated in 2017 and its prevention was recognised as fundamental priority for all organisations involved in delivering the strategy (HM Government, 2019). Furthermore, the first ever Minister of Mental Health, Inequalities and Suicide Prevention was appointed in 2018 along with increased funding for suicide prevention (GOV.UK, 2018). In a series of policy initiatives, local NHS organisations and local government have been asked to draw up joint plans, according to guidelines from Public Health England, to reduce suicide by 10% in 2020 (Appleby et al., Reference Appleby, Hunt and Kapur2017; NHS England, 2018). Although suicide rates are strongly related to self-harm rates (Geulayov et al., Reference Geulayov, Casey, McDonald, Foster, Pritchard, Wells, Clements, Kapur, Ness, Waters and Hawton2018), hospital management of self-harm remains variable across the country and there has until recently been little sign of service improvement over time (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Steeg, Bennewith, Lowe, Gunnell, House, Hawton and Kapur2013).

Although the overall incidence of self-harm in England has been estimated previously (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Casey, Simkin, Palmer, Cooper, Kapur, Horrocks, House, Lilley, Noble and Owens2007; Geulayov et al., Reference Geulayov, Kapur, Turnbull, Clements, Waters, Ness, Townsend and Hawton2016), little is known about its distribution across England. The only available nationwide estimates of self-harm incidence at local level are reported by Public Health England based on hospital admissions, which underestimate the scale of the problem (Clements et al., Reference Clements, Turnbull, Hawton, Geulayov, Waters, Ness, Townsend, Khundakar and Kapur2016; Public Health England, date accessed 27/02/2018). Besides the impact on population health, self-harm has considerable implications for healthcare costs, including costs of medical, psychiatric and social care (Sinclair et al., Reference Sinclair, Gray, Rivero-Arias, Saunders and Hawton2011a). A recent UK study based on a single centre estimated hospital costs to be on average £809 per self-harm presentation, with an approximate extrapolation to England of an impact on the NHS budget of approximately £162 million each year (Tsiachristas et al., Reference Tsiachristas, McDaid, Casey, Brand, Leal, Park, Geulayov and Hawton2017). This is a concerning figure for local health service commissioners, which increasingly face budget constraints and pressure to improve efficiency in healthcare organisation and delivery.

Estimating the incidence of self-harm presentations to hospitals and the associated hospital costs at a local level is key for designing services for individuals who self-harm and in planning hospital budgets. The aim of this study was to estimate the incidence of self-harm presentations to hospitals at both local and national levels and the associated hospital costs across England.

Methods

Study setting and primary data

The data were collected as part of the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. The three centres in the study have been collecting comprehensive data on hospital presentations for self-harm for many years, using similar methodology. The Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England was established early this century in order to provide more representative data on self-harm than each individual centre could provide. In this respect the three cities have a broad geographical distribution, with Oxford in South-East England, Derby in the East-Midlands and Manchester in North-West England. Oxford, Manchester and Derby also have distinctly different profiles in terms of the extent of socio-economic deprivation of their individual catchment areas. Based on the 2015 ratings of the Index of Multiple Deprivation scores for England, which range from 1 (worst) to 209 (best) across England, Manchester was ranked 5 (worst), Derby 55 and Oxford 166 (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2015). While this does not entirely ensure that the study is fully representative of England as a whole, it means that the data on self-harm are far more representative than those from single centres.

The provision of mental health care in general hospitals in England is mainly limited to that focussed on general medical patients with mental health problems and patients who present following self-harm. This includes both care while patients are in hospital and coordinating care after hospital discharge, such as psychological support (e.g. for cancer patients). The overall provision of mental health-related care is funded through general government funds allocated to NHS England. With regards to self-harm, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends provision of a psycho-social assessment for all patients who present with self-harm to the emergency departments of general hospitals (NICE, 2011). This assessment is conducted by a member of the hospital mental health team and is focussed on assessing patients' problems, needs and risks to determine their subsequent care after leaving hospital. As other specialised mental health care is generally provided by separate community and other mental health teams and is therefore not part of our study. Since there are virtually no emergency departments in private hospitals in England, the cost of self-harm in private hospitals was not included in our study.

Adopting the working definition of the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England, which is used nationally in England (NICE, 2011), self-harm was defined as intentional self-injury or self-poisoning, irrespective of type of motivation or degree of suicidal intent. Self-poisoning was defined as the intentional self-administration of more than the prescribed or recommended dose of any drug (e.g. analgesics, antidepressants), and includes poisoning with non-ingestible substances (e.g. household bleach), overdoses of ‘recreational drugs’ and severe alcohol intoxication where clinical staff consider such cases to be acts of self-harm. Self-injury was defined as any injury that has been deliberately self-inflicted (e.g. self-cutting, jumping from height). Identification of cases was determined by clinical and research staff using these criteria.

The data included individual patient level data for all self-harm presentations to the emergency departments of five general hospitals (one in Oxford, three in Manchester and one in Derby) between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2014. The information collected included: overall self-harm method (i.e. self-poisoning, self-injury, both), specific self-harm method (e.g. cutting, poisoning by specific drugs), hospital admission and patient socio-demographic characteristics (i.e. age, gender and ethnicity). It also included the provision of psychosocial assessment. We also obtained the actual hospital cost (i.e. direct and indirect costs of all hospital services) of each self-harm presentation in our dataset (i.e. in 2013/14 fiscal year) from the finance departments of the hospitals in Oxford and Derby. Mid-year 2013 population estimates for the study catchment areas by single year of age and gender, as well as suicide rates and proportion of the catchment area populations living in rural areas were retrieved at Clinical Commissioning Group level from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Data on the Market Forces Factor (an index that adjusts price differences across the country) in Oxford, Manchester and Derby were retrieved from NHS England.

Approximating the incidence of self-harm presentations to hospitals across England

The number of self-harm presentations was divided by the total population in the catchment area of the three centres of the Multicentre Study for single age years and gender to estimate the rate of self-harm presentation to hospital by age and gender in 2013. This rate was multiplied by the population per age year and gender in each local health service commissioning area (known as Clinical Commissioning Groups – CCGs) in England to estimate the number of self-harm presentations in each CCG nationally by age and gender. The total number of self-harm presentations per CCG area in England was calculated by summing all self-harm presentations by age and gender.

Exploring heterogeneity in hospital costs in the multicentre study

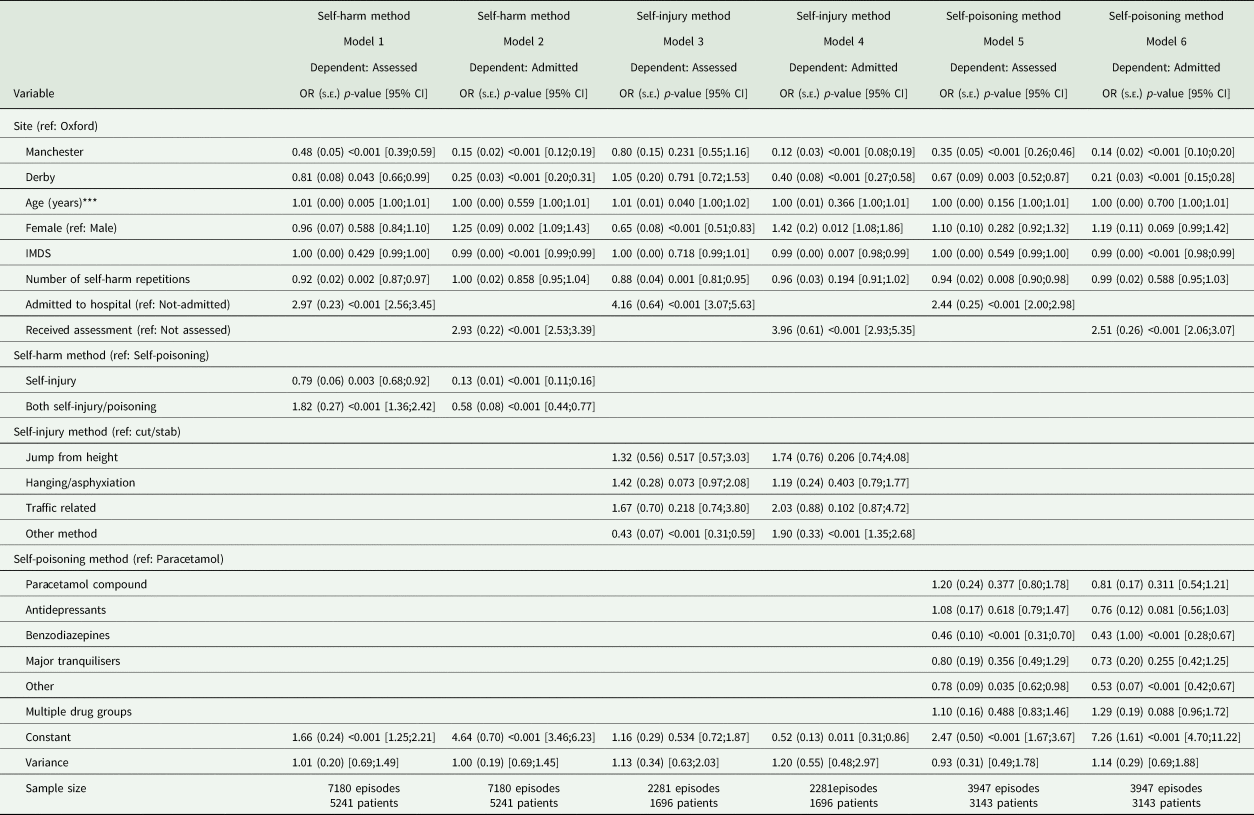

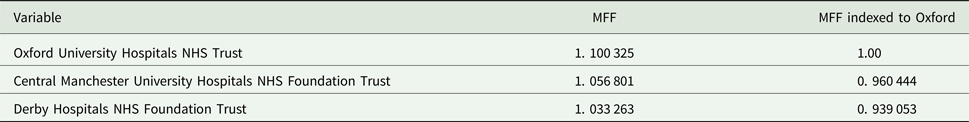

Heterogeneity in costs among hospitals may be explained by patient case-mix (i.e. hospitals provide medical services to patients of different severity and medical needs), mix and quality of services provided (i.e. hospitals may provide services differently for the same need for care and their quality may vary) and production constraints (i.e. hospitals may have different prices for capital and labour inputs) (Street et al., Reference Street, Scheller-Kreinsen, Geissler and Busse2010). We explored differences in patient case-mix between the three centres in terms of patient socio-demographic characteristics, overall and specific methods of self-harm and number of self-harm presentations during the study period. For this purpose, descriptive statistical analysis (i.e. frequencies, measures of central tendency and variability) was performed and differences between the three centres were tested with ANOVA and Kruskal−Wallis for continuous variables and chi-squares for categorical variables. In a subgroup descriptive analysis, we additionally compared the occupational status of those patients who had received psychosocial assessment between the three centres. Furthermore, we explored the variation in provided services (i.e. hospital admission and provision of psychosocial assessment) across the three centres using a descriptive statistical analysis. Mixed-Effects Generalised Linear Models were specified to estimate odds ratios for hospital admission and provision of psychosocial assessment adjusted for patient case-mix in order to explore differences in quality of care for self-harm between the three centres. Production constraints were accounted in our study by using the Market Forces Factor to adjust for unavoidable and location-specific cost differences (e.g. differences in land, buildings and staff costs) between the hospitals included in the Multicentre Study.

Estimating hospital costs of self-harm across England

Hospital cost data from Derby did not include the costs of psychosocial assessment. Therefore, we added £392 for patients younger than 18 years and £228 for adult patients to the hospital costs of those patients who had received psychosocial assessment in Derby. These unit costs were published recently and were close to the national average costs of psychosocial assessment reported by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (Tsiachristas et al., Reference Tsiachristas, McDaid, Casey, Brand, Leal, Park, Geulayov and Hawton2017). Furthermore, hospital cost data for each self-harm presentation in Oxford and Derby were regressed by gender, age, receipt of psychosocial assessment, hospital admission and general type of self-harm using a generalised linear model with Gamma distribution, log link and standard errors adjusted for clustering of episodes in patients. The coefficients of this regression analysis were fitted to the data from Manchester to estimate the hospital costs of self-harm presentations in Manchester after adjusting further for the Market Forces Factors. Using the hospital cost of all self-harm presentations in the dataset, we then calculated the mean hospital costs per self-harm presentation by age year and gender. The total costs of self-harm in each CCG area in England were then estimated by multiplying the estimated mean hospital costs per self-harm episode by age and gender with the estimated number of self-harm episodes in each CCG by gender and age.

Sensitivity analysis

Monte-Carlo simulation with 10 000 iterations was performed using the regression coefficients and standard errors from the generalised linear model to address the uncertainty in the results caused by predicting the hospital costs of self-harm presentations in Manchester. The uncertainty based on the simulation was displayed as 95% confidence intervals of the estimated hospitals costs across England. Furthermore, two univariate sensitivity analyses were performed to address the uncertainty in the national estimates of self-harm incidence and related hospital costs from the extrapolation of the Multicentre study. In the first, we used gender-specific and age standardised rates of suicide in each CCG between 2012 and 2014 to adjust the estimated number of self-harm presentations. To do this, we multiplied the estimated number of self-harm presentations by an adjustment factor. The suicide adjustment factor (by gender) was calculated by dividing the age standardised suicide rate in each CCG area by the average age standardised suicide rate in the three centres of the Multicentre Study. The underlying assumption for performing this sensitivity analysis was that suicide (i.e. death by intentional self-harm) and self-harm have common risk factors (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2012) and there is evidence showing a strong positive relationship between rates of self-harm and suicide (Geulayov et al., Reference Geulayov, Casey, McDonald, Foster, Pritchard, Wells, Clements, Kapur, Ness, Waters and Hawton2018). Given that the method used to estimate the incidence of self-harm in the present study was based on data from largely urban areas in the Multicentre Study, a second univariate sensitivity analysis was performed by adjusting the estimated number of self-harm presentations in each CCG based on the rural/urban classification. For this, we used a rurality adjustment factor (by gender) for each CCG to account for approximately 31% lower self-harm presentations in males and 26% in females in rural areas compared with urban areas in England (Harriss and Hawton, Reference Harriss and Hawton2011).

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study reviewed the study proposal, awarded funding and monitored the conduct of the study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

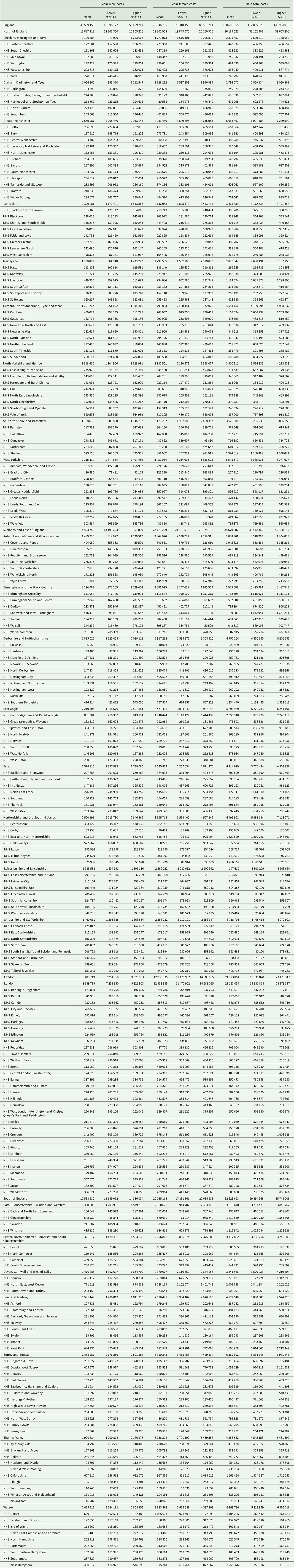

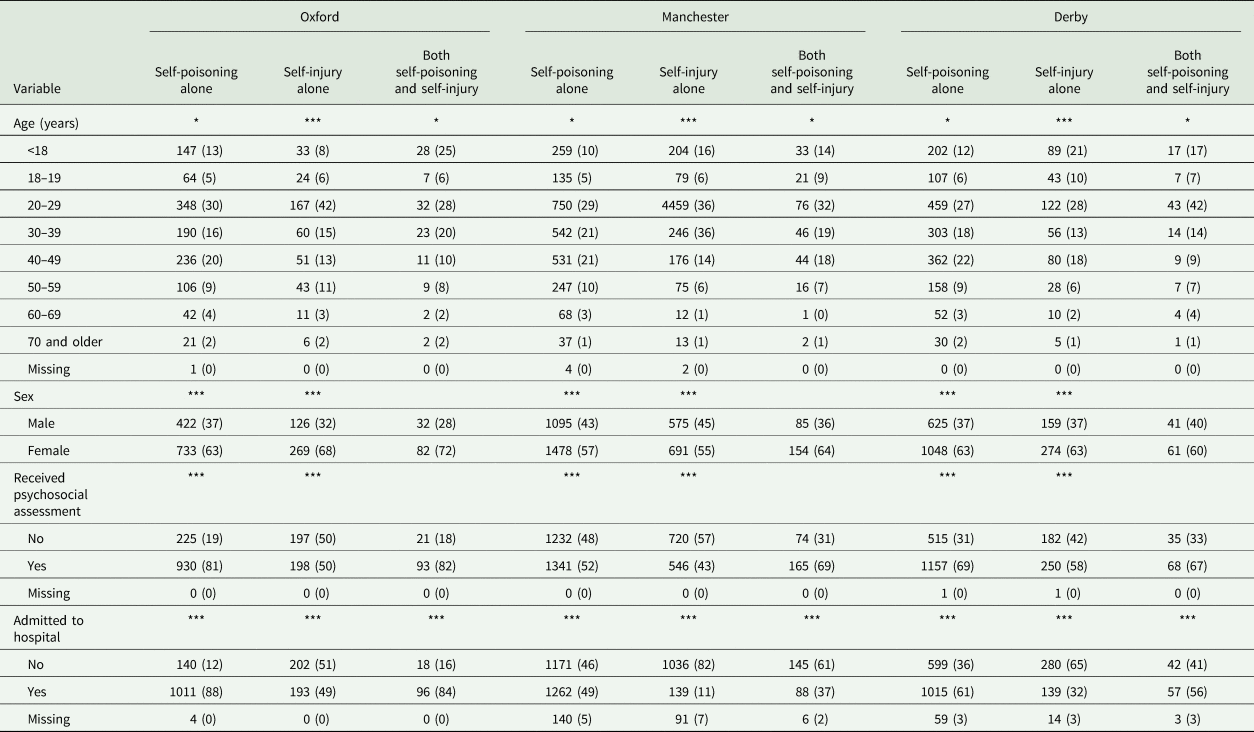

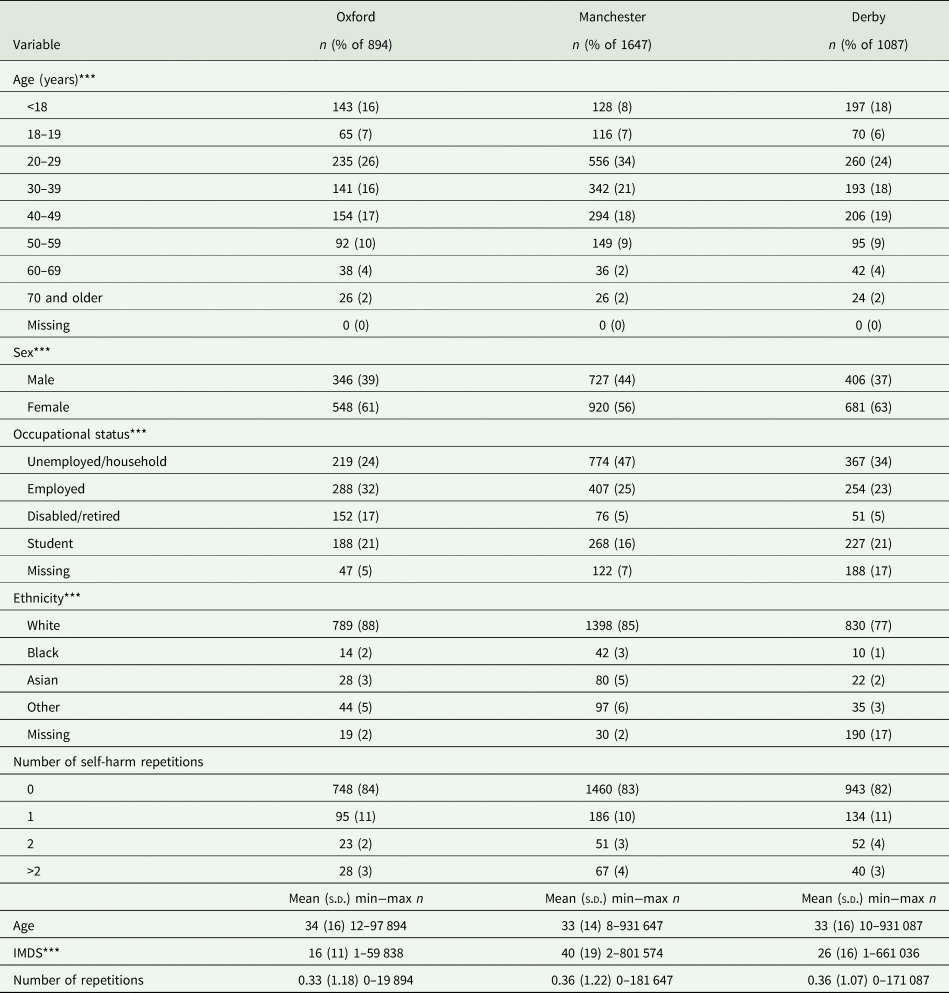

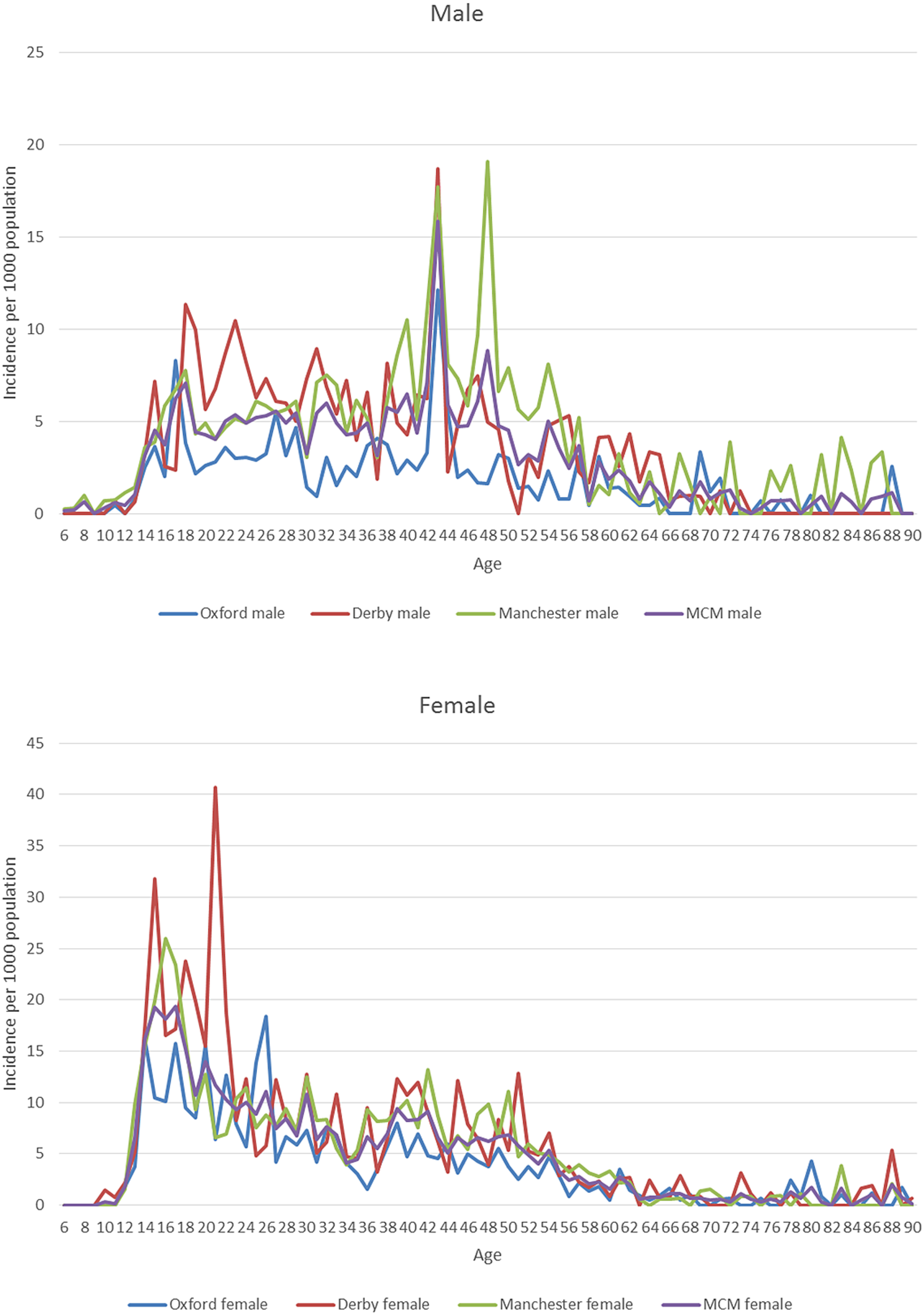

The results in panel A of Table 1 show that the sample in Manchester included proportionally fewer patients younger than 20 years (2 percentage points) and less females (5 percentage points) compared to the other two settings, while there were proportionally more patients of White ethnicity in Oxford (10 percentage points) compared to Manchester and Derby. The percentage of people having two or more self-harm repetitions in 2013 was higher in Derby (9%) followed by Oxford (7%) and Manchester (6%). Among the three centres, the proportion of episodes of self-harm involving self-poisoning alone ranged from 63% in Manchester to 76% in Derby, the proportion in which cutting was the method of self-injury ranged from 65% in Oxford to 80% in Derby, the proportion of self-poisoning episodes involving paracetamol or paracetamol-containing compounds ranged from 27% in Manchester to 33% in Derby (panel B of Table 1). The proportion of self-harm episodes in which a psychosocial assessment was conducted ranged from 50% in Manchester to 73% in Oxford, while admissions to hospitals ranged from 37% of episodes in Manchester to 78% in Oxford. The rate of self-harm presentations per 1000 population was highest in Manchester, except for the age groups 19–29 years, 30–39 years and 60–69 years where it was highest in Derby (panel C of Table 1). More detailed information about the variation in patient case-mix, service provision, self-harm rates and Market Force Factors between the three centres is provided in Appendices 1–5.

Table 1. Variation in patients and self-harm episodes across the three centres of the multicentre study

*p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.0001; # other methods include: drowning, gunshot, gas, head banging.

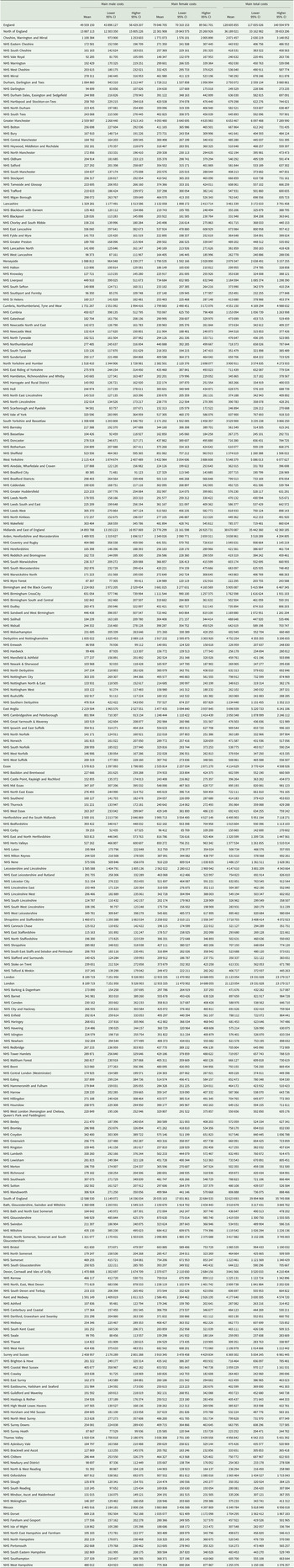

As Table 2 shows, there were an estimated 228 075 self-harm presentations (39% males and 61% females) by 159 857 patients in 2013 in England. The highest proportion of self-harm presentations among males was in the 40–49 year age group (30%), while for females the 19–29 year age group had the highest percentage of presentations (28%). Based on the two univariate sensitivity analyses, estimated self-harm presentations in England were 215 588 after adjusting for suicide rates and 225 172 after adjusting for rurality.

Table 2. Estimated incidence of self-harm in England in 2013 by gender and age group

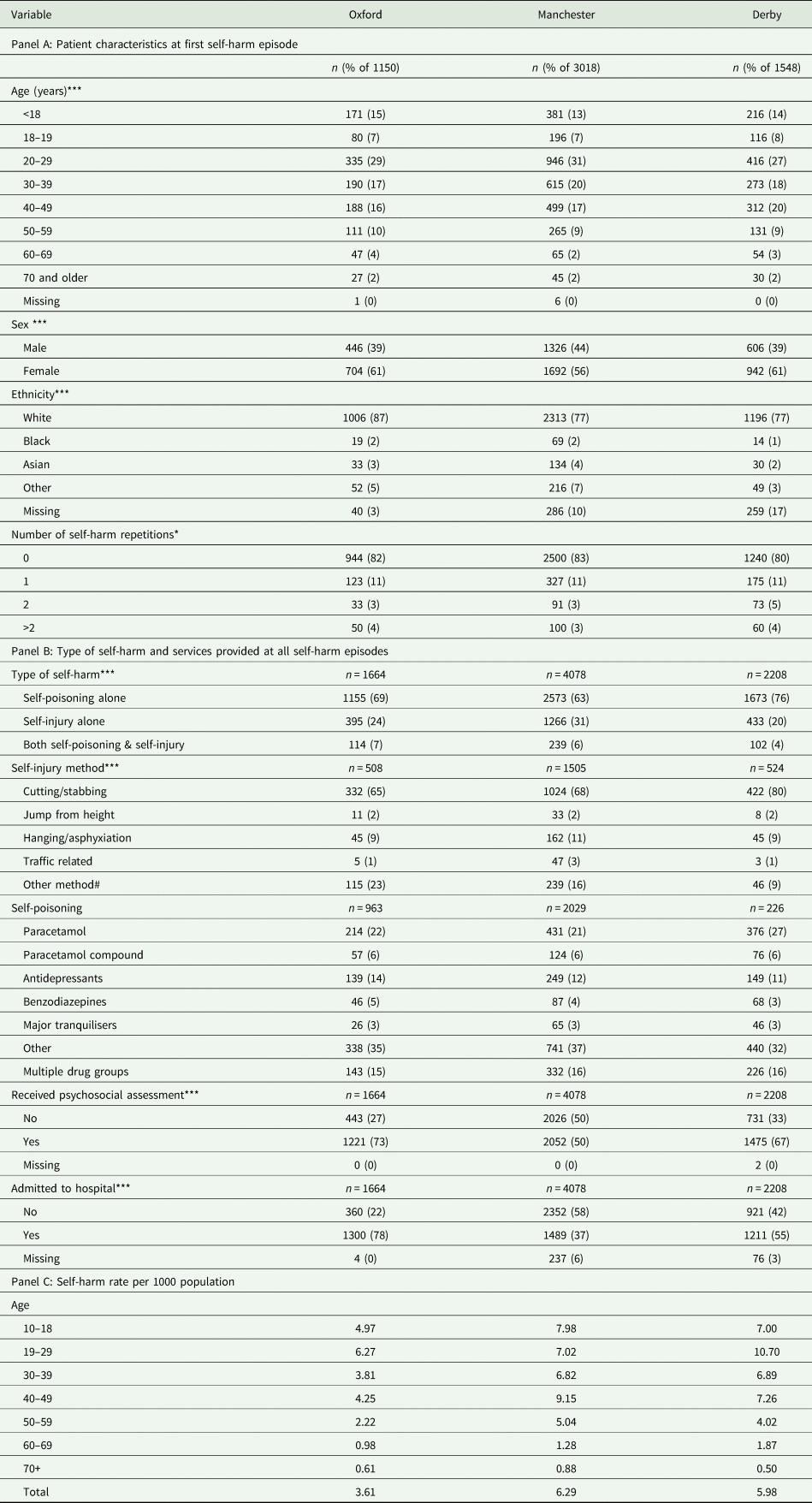

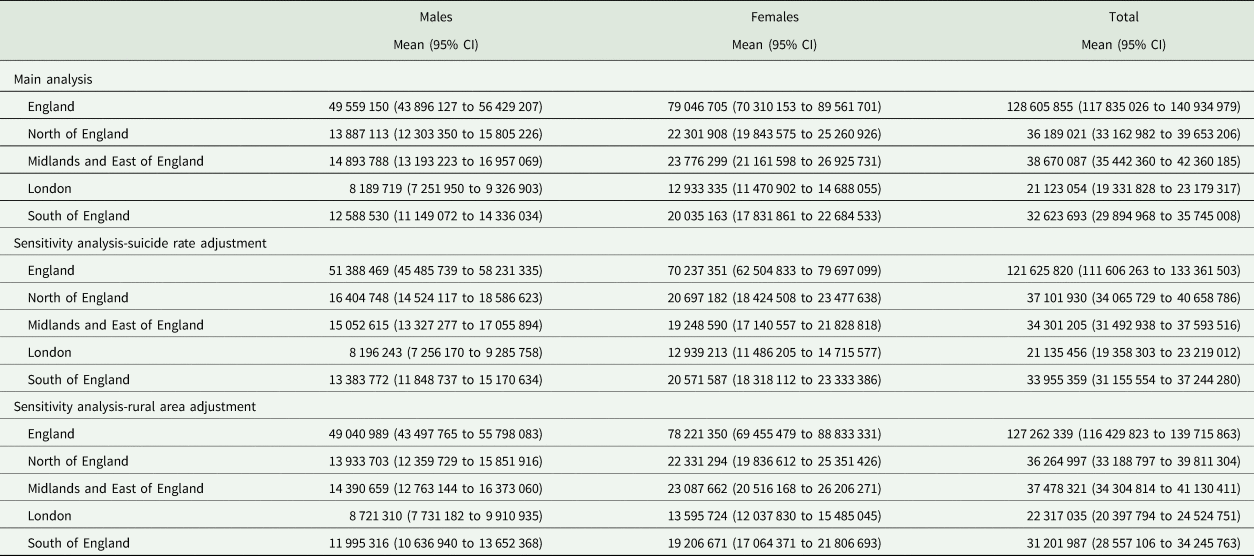

The estimated hospital cost of self-harm in England in 2013 was approximately £128.6 (95% CI 117.8−140.9) million. In absolute terms, the majority of costs were for episodes involving women and were greatest in the Midlands and East regions (Table 3). The total hospital costs of self-harm reduced to £121.6 (95% CI 111.6−133.4) million or £127 (95% CI 116.4−139.7) million after independently adjusting for suicide rates and rurality, respectively, and assuming that the representativeness of the patients recorded in the Multicentre Study of Self-harm to all patients who self-harmed in England in the same period was not perfect.

Table 3. Hospital cost of self-harm across large geographic areas in England (£, 2013)

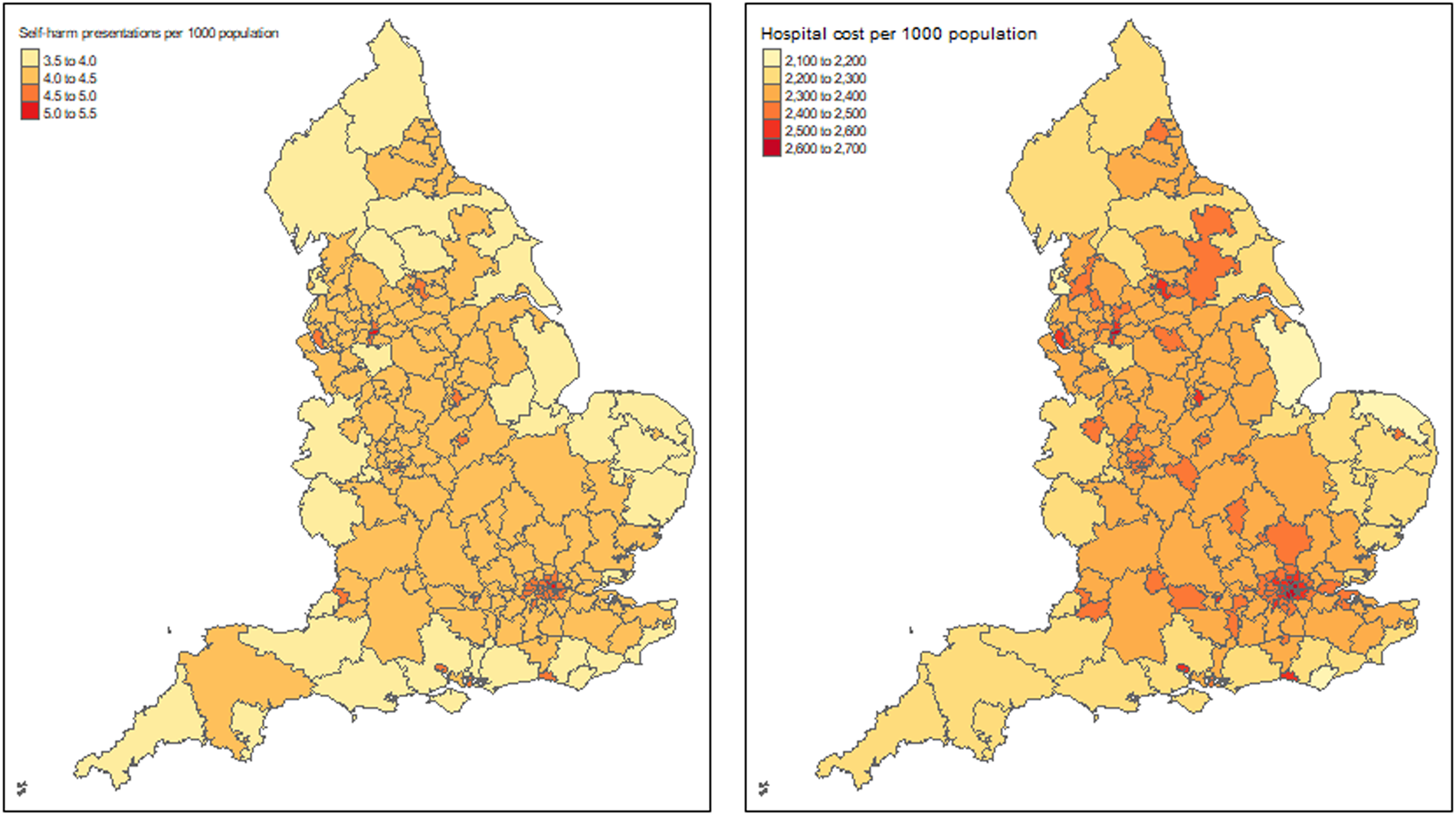

Figure 1 presents the distribution of estimated self-harm presentations and associated hospital costs per 1000 population across local health authorities in England. As shown in the figure, the incidence of self-harm and associated hospital costs was relatively lower in the majority of coastal areas, higher in inland areas and highest in the greater London area. The estimated hospital costs by CCG in England are presented in Appendix 6.

Fig. 1. Map of England with the estimated self-harm episodes and associated hospital cost per 1000 population in 2013.

Discussion

This study provides the first detailed estimates of self-harm presentations to hospitals and their associated hospital costs across England. The results of this study may assist national and local health decision makers in planning the distribution of funds for self-harm and prioritising interventions in areas with the highest need for tackling self-harm. Providing the incidence of self-harm presentations in each CCG by gender and age highlights sub-populations potentially where additional resources might be targeted to interventions that may prevent self-harm and assist those who have self-harmed, reducing therefore suicide deaths.

Using our incidence estimates and considering that there were 4727 (3688 male and 1039 female) deaths by suicide in England in 2013 (Statistics, 2016), our results indicate that there were 48 (24 male and 135 female) self-harm presentations to hospitals per suicide and 34 (17 male and 93 female) patients presenting with self-harm per suicide. While these ratios may seem quite large, self-harm is the strongest factor associated with subsequent suicide (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Cooper, Turnbull, Waters, Ness and Kapur2015). Risk is also particularly high in the period shortly after self-harm (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Ferrey, Casey, Wells, Fuller, Bankhead, Clements, Ness, Gunnell, Kapur and Geulayov2019). Therefore, primary and secondary prevention interventions that focus on reducing self-harm presentations and on provision of effective aftercare for those who do self-harm may prevent subsequent deaths by suicide (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Casanas, Haw and Saunders2013; Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Metcalfe, Steeg, Davies, Cooper, Kapur and Gunnell2016; Geulayov et al., Reference Geulayov, Casey, McDonald, Foster, Pritchard, Wells, Clements, Kapur, Ness, Waters and Hawton2018). This is in line with economic evidence that supports the provision of public health interventions (including psychological therapies) for self-harm and suicide prevention (McDaid et al., Reference McDaid, Park and Knapp2017; Campion and Knapp, Reference Campion and Knapp2018). However, effective implementation of self-harm and suicide prevention strategies at local level is challenging in terms of both deciding what initiatives may be effective and how to evaluate these (Saunders and Smith, Reference Saunders and Smith2016; Hawton and Pirkis, Reference Hawton and Pirkis2017). In England, Public Health England and CCGs also have to contend with many competing health issues. Moreover, strategies need to be implemented in partnership with multiple local health service providers, as well as the local government public health services. Compliance with national guidance is another challenge for policy makers and service commissioners. Most public health and healthcare decision making in England is made at a local level, leading to substantive variation in service delivery so that many patients still do not receive psychosocial assessment when presenting at hospital for self-harm (Geulayov et al., Reference Geulayov, Kapur, Turnbull, Clements, Waters, Ness, Townsend and Hawton2016).

Our estimated incidence of self-harm presentations in England (i.e. 228 075) is close to previously reported more crude estimates of 200 000 episodes per year (Geulayov et al., Reference Geulayov, Kapur, Turnbull, Clements, Waters, Ness, Townsend and Hawton2016). This can be contrasted with much lower rates seen in Public Health England's ‘Fingertips’ database suggesting that this underestimates overall rates of self-harm by approximately 60% compared with rates based on the Multicentre Study (Clements et al., Reference Clements, Turnbull, Hawton, Geulayov, Waters, Ness, Townsend, Khundakar and Kapur2016). This is because Fingertips only includes self-harm episodes resulting in hospital admission based on Hospital Episodes Statistics data. It should be noted that our study has estimated only the incidence of self-harm presentations to hospitals; it is well recognised that much self-harm occurs in the community without presentation to hospital, especially among adolescents (Geulayov et al., Reference Geulayov, Casey, McDonald, Foster, Pritchard, Wells, Clements, Kapur, Ness, Waters and Hawton2018).

We estimated the hospital cost of self-harm in England in 2013 to be approximately £128.6 million (£133.8 million in 2017 prices using an inflation rate of 1.04062 based on the Hospital and Community Health Services inflation index) (Curtis and Burns, Reference Curtis and Burns2017). This figure is lower than the roughly estimated £161.8 million per year cost of self-harm to NHS hospitals reported recently (Tsiachristas et al., Reference Tsiachristas, McDaid, Casey, Brand, Leal, Park, Geulayov and Hawton2017). It also seemed robust after performing two sensitivity analyses that accounted for the association of self-harm rates with suicide rates (Geulayov et al., Reference Geulayov, Kapur, Turnbull, Clements, Waters, Ness, Townsend and Hawton2016) and rural areas (Harriss and Hawton, Reference Harriss and Hawton2011). The estimated costs in the Oxford CCG area in the present study was £1 565 464 and the total hospital cost of self-harm presentations to the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford was actually £1 280 394. These figures therefore provide us with confidence about the internal validity of our cost estimates considering that the difference is likely to be due to the costs of self-harm presentations to the Horton General Hospital, a much smaller hospital than the John Radcliffe, which is also contracted by the Oxfordshire CCG. An additional reassurance for the robustness of our estimated incidence and costs is that the five hospitals included in the Multicentre Study cover populations with a wide range of socio-economic deprivation e.g. 5 in Manchester, 55 in Derby and 166 in Oxford (IMD score range: 1 most deprived to 209 most affluent) (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2015). This variation is reassuring considering that socio-economic deprivation is associated with self-harm and suicide (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Harriss, Hodder, Simkin and Gunnell2001).

While detailed estimates of the costs of all cases of self-harm have been made for a single hospital (Tsiachristas et al., Reference Tsiachristas, McDaid, Casey, Brand, Leal, Park, Geulayov and Hawton2017), this study is to our knowledge the only detailed analysis, applying a consistent methodology to estimate national self-harm costs by documenting care trajectories and measuring actual resource utilisation for all self-harm treatment costs, broken down by age, gender and means of self-harm, across multiple general hospital sites in different areas of England. A recent evaluation of the extension of hours of a liaison psychiatry service in a hospital in the south-west of England reported mean costs per emergency department self-harm attendance, including liaison psychiatry service use and inpatient care were reduced from £784 to £700 (£777−£694 in 2013/14 prices), but unlike our analysis NHS reference costs rather than a detailed resource and costing exercise were used to estimate costs (Opmeer et al., Reference Opmeer, Hollingworth, Marques, Margelyte and Gunnell2017). No attempt was made to estimate costs at a wider geographical level.

Other UK studies have concentrated on the costs of deliberate self-poisoning alone. In 2006/07 one-year costs, not including psychosocial assessment, of 1598 deliberate self-poisonings (aged >16 years) presenting to a general hospital in Nottingham were estimated using NHS reference costs to be £1.64 million or £1026 per poisoning; the authors noted that if repeated across England costs per annum would be much higher than our estimate for all self-harm costs at approximately £170 million (£192 million at 2013/14 prices) (Prescott et al., Reference Prescott, Stratton, Freyer, Hall and Le Jeune2009). UK-wide costs for emergency department presenting paracetamol poisonings following the impact of a change in national guidelines on presentations at three hospitals in Edinburgh, Newcastle and London were estimated to be £48.3 million (£49.7 at 2013/14 prices), again using English NHS tariffs rather than measuring costs (Bateman et al., Reference Bateman, Carroll, Pettie, Yamamoto, Elamin, Peart, Dow, Coyle, Cranfield, Hook, Sandilands, Veiraiah, Webb, Gray, Dargan, Wood, Thomas, Dear and Eddleston2014). Some much older English studies also compared the costs of treating self-poisoning, including psychosocial assessment, across multiple general hospitals over periods of up to five months in the late 1990s; they highlighted substantive variations in costs in part due to type of poisoning as well as differences in care pathways (Kapur et al., Reference Kapur, House, Creed, Feldman, Friedman and Guthrie1999a, Reference Kapur, House, Creed, Feldman, Friedman and Guthrie1999b, Reference Kapur, House, Dodgson, May, Marshall, Tomenson and Creed2002), estimating England wide costs of £56 million (£90 million at 2013/14 prices) (Kapur et al., Reference Kapur, House, May and Creed2003).

Information making use of the total costs of hospital presenting self-harm to estimate national costs in other high-income countries has also been limited, although access to administrative datasets linked to health insurance records in some countries potentially would allow for more detailed estimates to be produced. Data from the 2006 US Nationwide Emergency Data Sample was used to identify presentations by individuals aged 65 years and over to emergency departments, as well as hospitalisations and hospital charges (Carter and Reymann, Reference Carter and Reymann2014). This resulted in an estimate of almost 22 500 presentations per annum nationwide with total charges of $354 million. Other US studies have also estimated the costs of self-harm for specific population groups or for specific types of self-harm at state or national levels make use of various administrative/billing datasets. None looked at costs for all intentional self-harm (White et al., Reference White, MacInnes, Hingson and Pan2013; Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Kalb, Vasa, Goldstein and Wilcox2015; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, McDonald, Koziol, McCormick, Viner-Brown and Alexander-Scott2017). Similarly, in Australia, cost estimates have only been made for young people, with costs between 2002 and 2012 for all children aged ⩽16 years identified through the National Hospital Morbidity Database as being hospitalised for intentional self-harm estimated to be $A 64 million (£34.5 million in 2013/14 prices). In this case neither annual costs nor detailed data for different injuries were reported (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Seah, Ting, Curtis and Foster2018). In Japan standard healthcare tariffs were combined with nationwide acute hospital discharge data to estimate costs of 7.7 billion Yen (£39.8 million in 2013/24 prices) for all drug-poisonings in people aged over 12 years in 2008 (Okumura et al., Reference Okumura, Shimizu, Ishikawa, Matsuda, Fushimi and Ito2012). This estimate did not distinguish between intentional and unintentional poisonings, nor did it include costs for patients who were not hospitalised. An in-depth analysis of costs for all patients presenting with intentional self-harm at two hospitals in Basel, Switzerland in 2003 generated mean cost of CHF 19 165; the authors also assumed nationwide costs of CHF 191 million (£112 million in 2013/24 prices), using a national conservative estimate of 10 000 hospital presenting self-harm events per annum, but noting the very limited information on self-harm rates in the country (Czernin et al., Reference Czernin, Vogel, Flückiger, Muheim, Bourgnon, Reichelt, Eichhorn, Riecher-Rössler and Stoppe2012).

The strengths of this study include the precision of identification of self-harm presentations to general hospitals through the Multicentre Study, the use of hospital cost data for all episodes in Oxford and Derby, the advanced analytical approach to extrapolate self-harm incidence and hospital costs from the Multicentre Study to England, and the extensive sensitivity analyses to address the uncertainty in the results. The main study limitations are related to the available data and include: (a) the lack of hospital cost data in Manchester, (b) cost data being limited only to care received in general hospitals, which is only a part of the overall long-term costs of self-harm (Sinclair et al., Reference Sinclair, Gray, Rivero-Arias, Saunders and Hawton2011b) and (c) that estimated self-harm incidence and hospital cost may have changed since 2013 due to changes in the incidence patterns (e.g. increase in incidence among young females) and services provision (e.g. there has recently been a considerable increase in provision of hospital services for self-harm patients on a 24 h seven day a week basis in England).

Our analysis can help to identify specific population groups to support within localities and also draw more attention directly to self-harm when developing local suicide and self-harm prevention and reduction strategies. A key element of our approach has been to measure resource use and costs rather than simply use published health system charges, which usually do not reflect actual costs. This will also help in more accurate evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of any interventions that may reduce self-harm events.

There is certainly a need to build on recent albeit relatively small-sized economic evaluations of actions to increase the use of psychosocial assessments (Opmeer et al., Reference Opmeer, Hollingworth, Marques, Margelyte and Gunnell2017) to help improve referral to appropriate care pathways, as well as economic evaluations of psychological and other follow-up care (O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Ferguson, Scott, Smyth, McDaid, Park, Beautrais and Armitage2017; Haga et al., Reference Haga, Aas, Grøholt, Tørmoen and Mehlum2018; Park et al., Reference Park, Gysin-Maillart, Müller, Exadaktylos and Michel2018). The potential economic benefits of effective interventions may also be greater than shown in these analyses, as there will be additional costs to the health sector, local government and other public agencies which may be averted by any reduction in future risk of both non-fatal and fatal self-harm events (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Cooper, Turnbull, Waters, Ness and Kapur2015). Although our analysis has focused on England we believe our approach could also in principle be adapted for use in the development of self-harm prevention strategies in other country contexts, particularly those where national administrative datasets that record hospital presenting self-harm are not available.

Data

Due to constraints on the data sharing permissions of the data in the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England, we are not allowed to share the data for public use.

Acknowledgements

We thank the NIHR Oxford-Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care, and in particular Professor Belinda Lennox, for their support. Our special thanks to A-La Park at the London School of Economics and Political Science for contributing to the literature review. We also thank members of the finance departments of Oxford University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust and the University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust, for providing data and advice. The authors from Derby would also like to thank Callum Burgess, Information Analyst, University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust, as well as Abigail Marron and Anita Patel (Research Assistants at Derbyshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust). KH was supported by Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. AT acknowledges financial support by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Oxford and Thames Valley. KH is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator (Emeritus). The Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England is funded by the Department of Health and Social Care. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author contributions

AT, KH and DM conceived the idea of the study. All authors developed the study protocol. AT drafted the manuscript, led the analyses and interpreted the results alongside DMcD, GG, DC and KH. GG, DC, FB, JN, KW, CC, NK, collected, managed and provided data from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm. KH was principal investigator. All authors made substantial revisions to earlier drafts and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

Department of Health and Social Care and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Conflict of interest

We declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The three research sites involved in the Multicentre Study of self-harm have approvals to collect data on self-harm for their local monitoring systems of self-harm and for multicentre projects. The monitoring systems in Oxford and Derby have received their approval from national health research ethics committees while self-harm monitoring in Manchester is part of a local clinical audit system ratified by the local research ethics committee. The three monitoring systems are fully compliant with the Data Protection Act (1998) and have approval under Section 251 of the National Health Service (NHS) Act (2006) to collect patient-identifiable data without explicit patient consent.

Appendix 1

Variation in patient characteristics and clinical care by method of self-harm in the three study sites

Appendix 2

Variation in patient characteristics of those who received psychosocial assessment by site

Appendix 3

Variation in the provision of clinical care between the three study sites

Appendix 4.

Self-harm incidence per 1000 population in the three study sites

Appendix 5

Market force factors (2013/14)

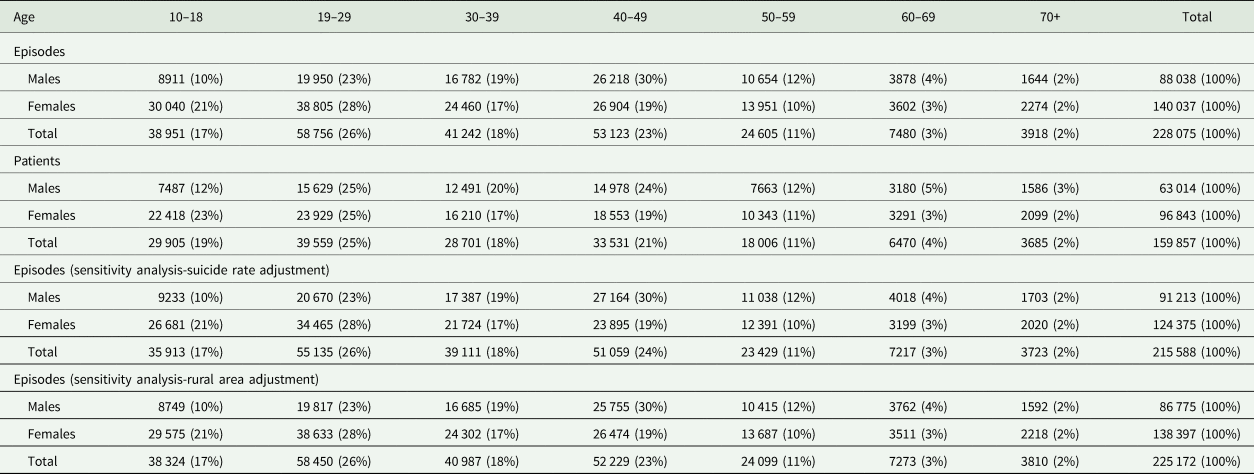

Appendix 6. Hospital cost of self-harm by local authority across England in 2013