Introduction

It is estimated that for every suicide death there are about 10–30, depending on the country, non-lethal suicide attempts (SAs) (Mościcki et al., Reference Mościcki, O'Carroll, Rae, Locke, Roy and Regier1988; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Borges, Nock and Wang2005; Han et al., Reference Han, Kott, Hughes, McKeon, Blanco and Compton2016; Bachmann, Reference Bachmann2018). Having attempted suicide constitutes the best predictor of suicide since about 40% of victims of suicide have records of previous attempts (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Sutton, Haw, Sinclair and Harriss2005; Hawton and van Heeringen, Reference Hawton and van Heeringen2009), multiplying the risk of suicide in the year following an attempt by 49 (Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Cooper, Turnbull, Waters, Ness and Kapur2015). However, not all SAs convey the same risk.

A medically serious suicide attempt (MSSA) has been defined as an SA that would have been fatal without access to emergency care and that subsequently required hospitalisation for more than 24 h in an intensive care unit (ICU), or surgery under general anaesthesia, regardless of the violence of the act (Levi-Belz and Beautrais, Reference Levi-Belz and Beautrais2016). MSSAs constitute a subsample of all SAs, and thus imply a potentially self-injurious behaviour, associated with at least some intent to die (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Oquendo, Gould, Stanley and Davies2007). The main difference between MSSAs and other SAs (low-lethality SAs) is the medical lethality of the attempt and, correspondingly, the level of subsequent medical care needed to keep the person alive. Establishing a cut-off based on the medical lethality of the attempt has been proposed as the best method to differentiate serious SAs, i.e. those ‘that would have been lethal had it not been for the provision of rapid and effective emergency treatment’ (Gvion and Levi-Belz, Reference Gvion and Levi-Belz2018). Compared to low-lethality SAs, individuals who make MSSAs are phenotypically closer to those who die by suicide (Mościcki et al., Reference Mościcki, O'Carroll, Rae, Locke, Roy and Regier1988; Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2003a; Gvion and Levi-Belz, Reference Gvion and Levi-Belz2018). They are older, more likely to have prior records of SAs and report higher lethality in previous SAs compared to attempters that never made an MSSA (Giner et al., Reference Giner, Jaussent, Olié, Béziat, Guillaume, Baca-Garcia, Lopez-Castroman and Courtet2014). Mental disorders and suicide methods in MSSAs are also half-way between suicides and SAs. Many studies report that self-poisoning is majoritarian in MSSA samples (57–79%) but violent methods such as hanging are overrepresented (10–17%) in comparison to SAs with less serious consequences (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2003b; Horesh et al., Reference Horesh, Levi and Apter2012; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Guo, Zhang, Wang, Jia and Xu2015; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi, Lee, Kim, Hong, Lee, Kweon, Lee and Lee2020). Bipolar disorder, substance misuse and eating disorder are also overrepresented in MSSA samples (Giner et al., Reference Giner, Jaussent, Olié, Béziat, Guillaume, Baca-Garcia, Lopez-Castroman and Courtet2014). Conversely, the diagnoses of non-affective psychosis seem to be much more common in samples of suicide victims than in MSSA samples (OR = 8.5) (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2001).

Among suicide attempters, making an MSSA more than doubles the risk of completing suicide in the short term. One in 25 individuals (4%) die by suicide in the 18 months that follow an MSSA (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2004), but only 1.8% in the year after an SA (Probert-Lindström et al., Reference Probert-Lindström, Berge, Westrin, Öjehagen and Skogman Pavulans2020). This is also true in the medium term (over 5 years): 5.3–7% of MSSA attempters die by suicide (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2003a, Reference Beautrais2004) compared to 3.8% if we consider all the attempters (Probert-Lindström et al., Reference Probert-Lindström, Berge, Westrin, Öjehagen and Skogman Pavulans2020). The overall suicide mortality after an MSSA is multiplied by 5 compared to the general population (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2003a). Importantly, the direct assessment of individuals who made an MSSA, and could have died by suicide, provides proxy information about mental disorders, cognitive processes or psychological traits in suicide deaths (Clark and Horton-Deutsch, Reference Clark, Horton-Deutsch, Maris, Berman, Maltsberger and Yufit1992; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Appleby, Platt, Foster, Cooper, Malmberg and Simkin1998; Hawton, Reference Hawton2001).

We have scarce epidemiological information about MSSAs. Only some clinical studies investigated the somatic and psychiatric comorbidity associated to them. Here, we aimed to describe from a demographic and clinical standpoint the population that makes a first MSSA and what use they make of hospital care at a national level. We will also calculate the incidence of MSSAs. To our knowledge, only one study has done it before but it included suicide deaths before arrival at the hospital (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Guo, Zhang, Wang, Jia and Xu2015). Indeed, most previous studies were conducted on clinical samples of no more than 1500 individuals (Beautrais et al., Reference Beautrais, Joyce, Mulder, Fergusson, Deavoll and Nightingale1996; Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2001, Reference Beautrais2004; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi, Lee, Kim, Hong, Lee, Kweon, Lee and Lee2020). Our database provides exhaustive information on the entire French population admitted to hospitals between 2012 and 2019. Because of the small amount of data available on this topic and the high-risk profile of MSSA survivors, we believe that this study will provide useful information to caregivers in the management of suicidal behaviour.

Methods

Study design and data source

We conducted a nationwide observational study in French hospitals using the French nationwide hospital discharge database (Programme de Médicalisation des Systèmes d'Information, PMSI). The PMSI database contains synthetised and anonymised data about all the units of medical establishments providing acute care in France, which encompasses medicine, surgery and obstetrics (Medecine, chirurgie, obstétrique, MCO). Conventional psychiatric units are not included in the MCO sector. PMSI data are prospectively collected by all public and private hospitals in a standardised way for care reimbursement purposes. Every discharge summary contains sociodemographic information about the patient, medical information about the hospital stay and data related to the trajectory of the patient. Medical information is coded with the Tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).

National PMSI data are anonymised. Access to these data is authorised for research purposes and does not require the individual information and written consent of the patients. Approval of the National Data Protection Commission (Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté, CNIL) was obtained for this study and data were handled and analysed on the secured electronic platform of the National Agency for the Information on Hospitalisations (Agence Technique de l'Information sur l'Hospitalisation, ATIH).

Study population

All the inpatient admissions related to a first episode of MSSA in the acute care sector of French hospitals between 2010 and 2019 were considered for the present study. A hospital stay for an MSSA implied: (1) the presence of an intentional self-harm ICD-10 code X60–X84 in the discharge summary; (2) the admission to an ICU for somatic conditions, including critical care units; and (3) the absence of previous hospitalisations caused by an MSSA for at least the two preceding years. The 2-year period comprises the years 2010 and 2011 for MSSAs that took place in the year 2012, or the longest period available since 2010 for MSSA that took place after 2012. To ensure that we were studying a homogenous sample, only first admissions fulfilling the criteria for MSSA were selected.

Study variables

(1) Patients' demographics (sex and age), and comorbidities according to the Charlson index algorithm. The Charlson Comorbidity Index categorises a range of non-psychiatric comorbidities of patients based on the ICD to predict short-term mortality. The 1-year mortality rates for the different scores are: ‘0’, 12%; ‘l–2’, 26%; ‘3–4’, 52%; and ‘ >5’, 85% (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie1987).

(2) Medical variables: primary/main and secondary diagnoses coded with the ICD-10 related to organic and psychiatric comorbidities, and method of the SA. To summarise diagnostic data, we used ICD-10 chapter codes for mental disorders (F0 to F9). Three specific diagnoses were analysed separately because of their strong association with suicide risk: bipolar disorder (F30–F31), alcohol use disorder (AUD) (F10) and schizophrenia (F20).

(3) Variables related to the patients' intra and inter-hospital trajectory: lengths of stay, admission in ICU, origin of referral and destination, vital status at discharge.

(4) Admission in a psychiatric hospital within 3 days of discharge from the MCO units.

Statistical analysis

We performed descriptive analyses to characterise the sample. Qualitative variables were reported with numbers and percentages; quantitative ones, with means and standard deviations (SD). Comparison between groups were carried out using the Pearson χ 2 tests for qualitative variables (or Fischer exact tests for small groups as appropriate), and using the Student t-test for quantitative variables.

To estimate the incidence rates of first MSSA in the French general population, we used as numerator the exhaustive number of first MSSAs in France by age, sex and year (estimated by our whole population study), and as denominator the size of the French population by age, sex and year estimated by the French ‘National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies’ (INSEE). These population sizes are based on an annual national census and are directly available on the Institute's website (Papon & Beaumel, 2020).

Analyses were performed with a bilateral α level of 0.05 using the SAS Enterprise guide 7.15 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

A total of 7 35 416 MSSAs were found between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2019. Among them, 81 959 first-time MSSAs were identified and analysed (see data flowchart in Fig. 1). As we consider only the first MSSAs for the present study, one patient corresponds to one discharge summary.

Fig. 1. Data flowchart, selection of incident MSSA.

Sample description by sex

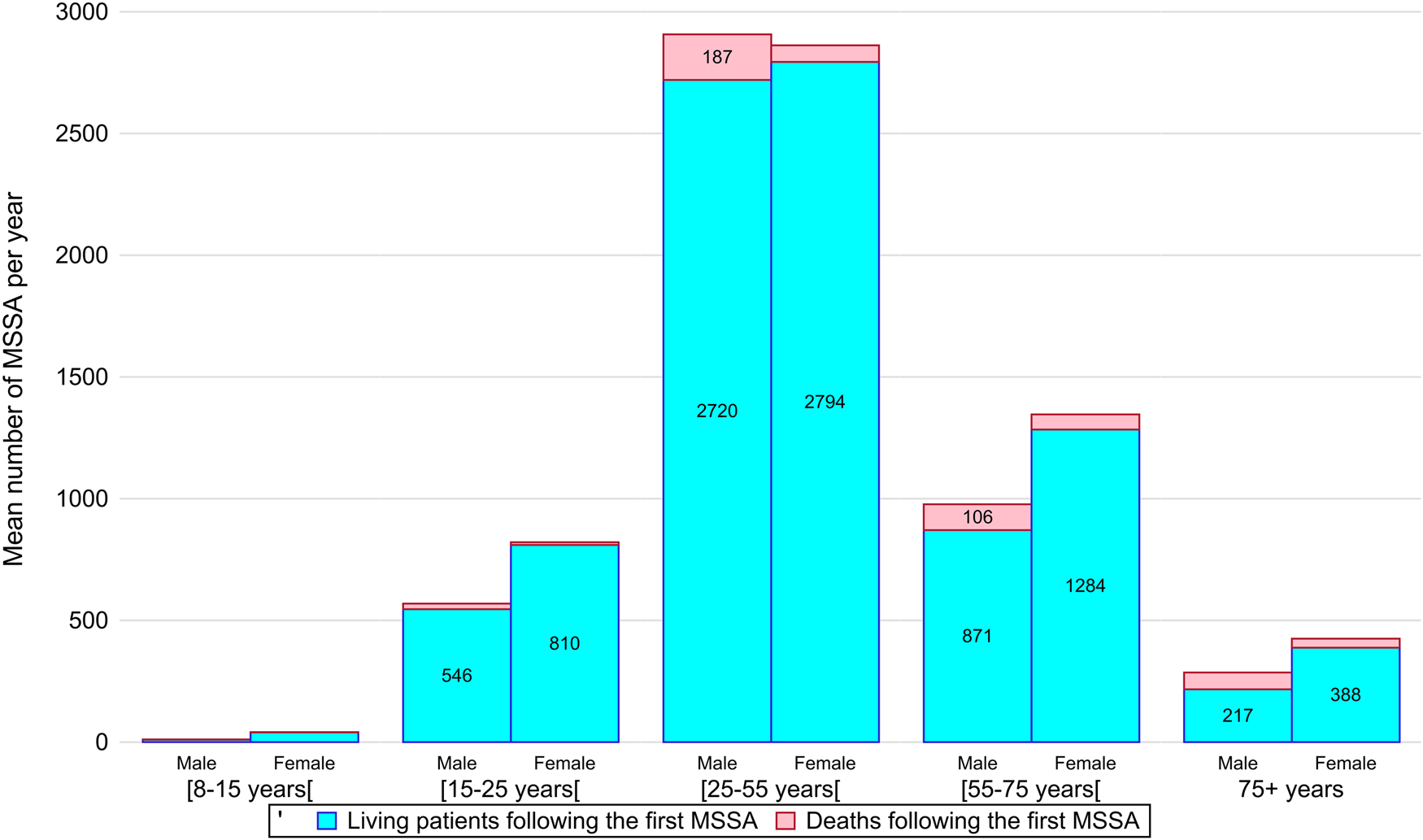

Women represent about a half of MSSA cases (N = 43 953, 53.62%; p < 0.0001), and a larger majority in extreme age groups (under 25 or over 55 years) (Table 1, Fig. 2). In the age group between 25 and 55 years, which counts with the largest caseload (N = 46 150, 56.3%), men are overrepresented (N = 23 258, 50.4%). MSSAs before 15 are rare in both sexes (N = 412, 0.5%).

Fig. 2. Stacked column chart representing the distribution by age group and gender of the average number of first medically serious suicide attempts (MSSAs) during the study period. Deaths following the first MSSA are shown on top of the columns.

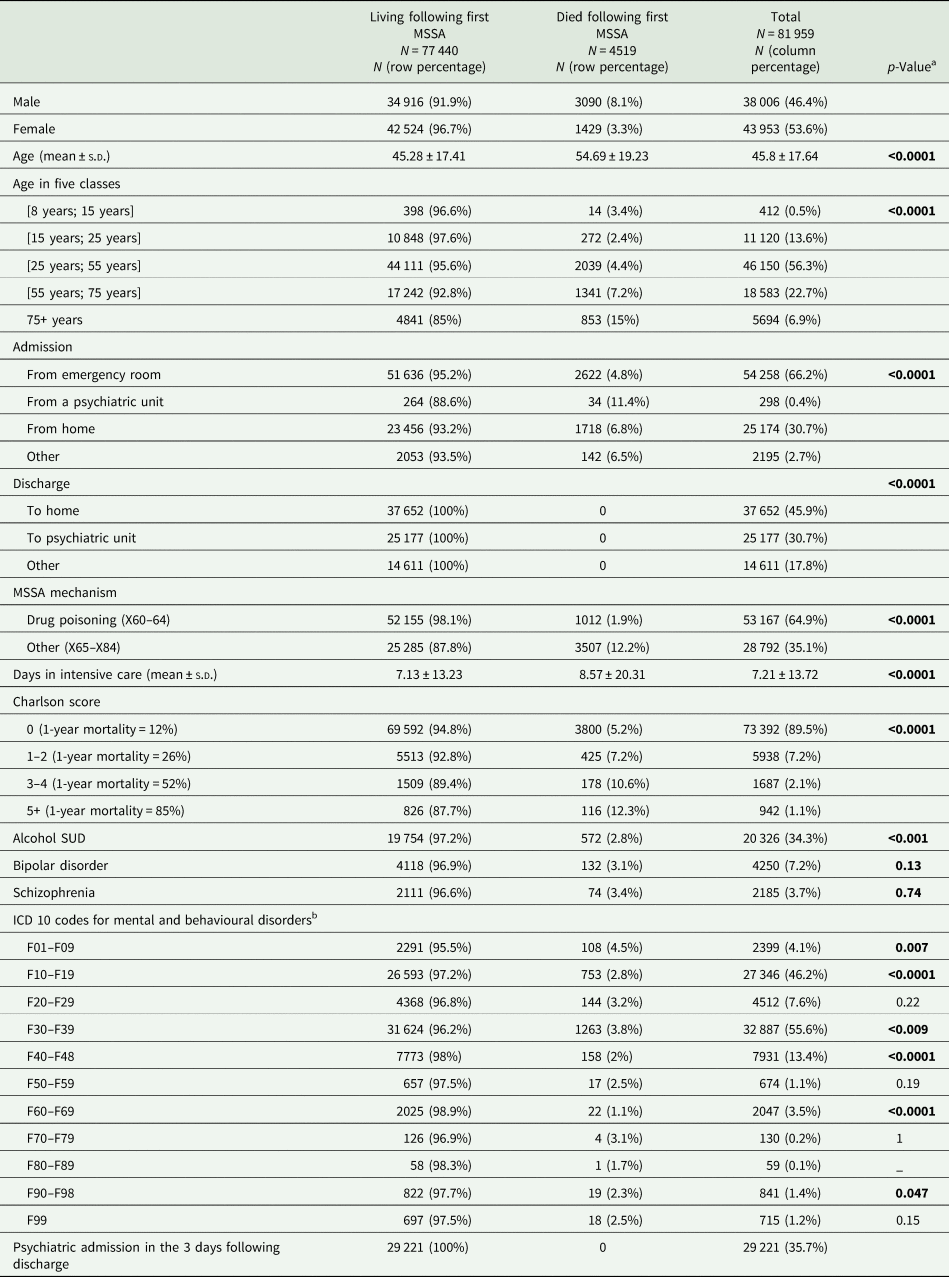

Table 1. Demographic and clinical features of all MSSA patients according to their sex

a p-Value for comparison between males and females, we used the Pearson χ 2 tests for qualitative variables and the Student t-test for quantitative variables.

b F00–F09: organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders; F10–F19: mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use; F20–F29: schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–F39: mood (affective) disorders; F40–F48: neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; F50–F59: behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors; F60–F69: disorders of adult personality and behaviour; F70–F79: mental retardation; F80–F89: disorders of psychological development; F90–F98: behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence; F99: unspecified mental disorder.

Bold text indicates p-values ≤ 0.5.

Deliberate self-poisoning (DSP) by drugs is the most common method of SA in MSSA (64.9% of the cases), especially among women (72.1% compared to 56.5% among men). Men are more likely to use violent methods such as hanging (7.9 v. 1.9% in women) or firearms (3.1 v. 0.2%). Men are also more likely to die after their first MSSA (8.1 v. 3.3%).

Concerning mental disorders, the most frequent diagnoses are mood disorders (55.6%), including bipolar disorder (7.2%), and substance use disorders (SUDs) (46.2%), including alcohol dependence (34.3%). Compared to women, men seem to suffer significantly more from SUDs (56.3 v. 37.5%), particularly alcohol dependence (42.8 v. 27.1%), and schizophrenia (5.5 v. 2.1%). Conversely, women are more concerned by mood disorders (64 v. 45.8%), including bipolar disorder (8.9 v. 5.1%). Personality disorders are balanced (approximately 3% in both genders).

The average length of stay is statistically higher for men, with 5.55 days spent in ICU compared with 4.4 days for women (p < 0.0001). The Charlson score is also higher in men (4.1% of men with Charlson score >3 v. 2.5% of women). Women are more likely to enter a psychiatric ward 3 days after their discharge from ICU (N = 16 912; 38.5% of women) than men (N = 12 309; 32.4% of men).

Comparison by fatal outcome

Following a first MSSA, 4519 patients died, representing 5.5% of the MSSA population (Table 2). MSSAs are significantly more lethal in men, resulting in death in 8.1% of cases v. 3.3% of women (p < 0.0001). On average, the deceased are older (54.69 ± 19.23 years) than the survivors (45.28 ± 17.41 years). A high case fatality rate is observed over 75 years of age, with 15% of deaths compared to 4.4% in the (25–55) age group. The proportion of fatal outcomes after an MSSA in patients admitted from psychiatry (11.4%) is higher than the same proportion in patients admitted from any other place (5.5%). The number of deaths to MSSA is stable throughout the study period (every year about 12–13% of the total).

Table 2. Demographic and clinical features of all MSSA patients by living v. deceased status

a p-Value for comparison between living v. deceased status, we used the Pearson χ 2 tests for qualitative variables, and the Student t-test for quantitative variables.

b F00–F09: organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders; F10–F19: mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use; F20–F29: schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–F39: mood (affective) disorders; F40–F48: neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; F50–F59: behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors; F60–F69: disorders of adult personality and behaviour; F70–F79: mental retardation; F80–F89: disorders of psychological development; F90–F98: behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence; F99: unspecified mental disorder.

Bold text indicates p-values ≤ 0.5.

DSP by drugs is less lethal (1.9% deaths) than any other method used in MSSAs (12.2% deaths). Among the deceased, the method chosen to attempt suicide is commonly violent. Hanging/strangulation is used in 38.5% of deaths but represents only 4.7% of all MSSAs, firearms are used in 9.8% of deaths and 1.6% of MSSAs. On the contrary, DSP accounts for 67.3% of MSSAs and 22.4% of deaths.

Mortality is particularly important in patients diagnosed with mood disorders or organic mental disorders (F3 and F0) when compared to any other diagnosis. On the contrary, diagnoses of SUD (F1), psychotic disorder (F2) or personality disorder (F6) are less often associated with a fatal outcome. Deceased patients have longer lengths of stay (8.57 ± 20.31 days) than survivors do (7.13 ± 13.23 days). In addition, the Charlson score is statistically higher in the decedents (15.9% with Charlson score >1 in the decedents v. 10.1% in the survivors).

Discharge to a psychiatric service

One-third of surviving MSSA patients are discharged directly to a psychiatric hospital (N = 25 177, 32.5%), while almost half are discharged directly to their home (N = 37 652; 48.6%) (Table 3). These numbers are stable over the study period. Women are more likely to be discharged to psychiatry than men. They represent 58.5% of discharges to a psychiatric hospital, whereas they constitute 54.9% of survivors. The extreme age groups are less likely to be hospitalised in psychiatry after ICU, less than 25% in the youngest and oldest age groups (8–15 years and over 75 years) compared to more than 30% in the other age groups (25–75 years).

Table 3. Demographic and clinical features of patients discharged to a psychiatric service after their first MSSA (n = 77 440 patients)

a p-Value for comparison according to the decision of discharge to a psychiatric unit or otherwise, we used the Pearson χ 2 tests for qualitative variables and the Student t-test for quantitative variables.

b F00–F09: organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders; F10–F19: mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use; F20–F29: schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–F39: mood (affective) disorders; F40–F48: neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; F50–F59: behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors; F60–F69: disorders of adult personality and behaviour; F70–F79: mental retardation; F80–F89: disorders of psychological development; F90–F98: behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence; F99: unspecified mental disorder.

Bold text indicates p-values ≤ 0.5.

MSSA survivors after DSP are more frequently hospitalised in psychiatry than those using different methods (34.2 v. 28.9%). Discharges to psychiatric hospitals after a violent MSSA, such as hanging (N = 925; 24%) or the use of a firearm (N = 167; 12.9%), are particularly infrequent.

Patients with psychotic disorder (N = 1969; 45.1%) or mood disorder (N = 11 843; 37.4%) are more often hospitalised in psychiatry, in contrast to those with SUD (N = 7639; 28.7%). Nearly three-quarters (N = 205; 77.7%) of psychiatric inpatients are re-admitted after intensive care in a psychiatric ward. On the other hand, about one-third of MSSA survivors coming from the emergency room (N = 17 525; 33.9%) or home (N = 6928; 29.5%) are subsequently admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

Patients who have fewer comorbidities are more often discharged to psychiatry (33.2% with Charlson score = 0 v. 17.7% with Charlson score > 5). Patients discharged to psychiatry wards also spend less time in intensive care than those discharged elsewhere (4.61 ± 7.2 v. 8.34 ± 15.17 days). Methods of attempting suicide are represented in Table 4.

Table 4. Demographic and clinical features of MSSA patients according to the main method used in the suicide attempt

a F00–F09: organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders; F10–F19: mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use; F20–F29: schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–F39: mood (affective) disorders; F40–F48: neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; F50–F59: behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors; F60–F69: disorders of adult personality and behaviour; F70–F79: mental retardation; F80–F89: disorders of psychological development; F90–F98: behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence; F99: unspecified mental disorder.

Incidence

We find an overall increase in the incidence of MSSAs over the study period, from 16.57 in 2012 to 17.75 in 2019 (cases per 1 00 000 person-years). This tendency was particularly marked in females aged 15–25 years with a 10-point increase (Table 5). In women, the incidence is consistently higher than in men, with a trend towards a narrowing of this gap. In 2012, the incidence is 17.42 in women and 15.66 in men. In 2019, 18.14 in women v. 17.33 in men.

Table 5. Incidence of the first MSSA per 100 000 person-years by age group and sex

Incidence rates were estimated using the exhaustive number of first MSSA in France by age, sex and year as the numerator and the French population size by age, sex and year as the denominator. The population size is based on an annual national census performed by the French ‘National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies’ (INSEE) and are directly available on the Institute's website (https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1913143?sommaire = 1912926).

a Incidence in the population over 8 years old.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date focused on MSSA. It provides an 8-year coverage of first MSSAs in the entire French population aged 8 or more and allows us to explore an important link of the ideation to action to death continuum. The resulting sample (n = 81 859) comprised roughly equal percentages of men and women, with a slight female majority. The most common method of attempting suicide in both sexes was DSP, although violent methods were over-represented in men and associated with higher mortality and comorbidity. These results are in accordance with the literature (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2001, Reference Beautrais2003b; Giner et al., Reference Giner, Jaussent, Olié, Béziat, Guillaume, Baca-Garcia, Lopez-Castroman and Courtet2014; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi, Lee, Kim, Hong, Lee, Kweon, Lee and Lee2020). More surprisingly, almost one in two MSSA went directly home after intensive care. These cases concern mainly men with psychiatric comorbidity and using violent methods. Precisely those MSSA survivors that are most at risk for suicide are the least hospitalised. For instance, one in four MSSA were discharged home after using violent methods such as firearms or jumping from a high place. Concerning psychopathology, we found an almost equal prevalence of mood disorders (55.6%) and SUDs (46.2%) in the sample. They were by large the most common psychiatric disorders and showed a clear gender pattern, women were more often diagnosed with mood disorders and men with SUDs.

One in 20 MSSA attempters died in our sample, which represents more than fivefold the death rate by any SA leading to hospitalisation in France between 2004 and 2011 (Chee and Jezewski-Serra, Reference Chee and Jezewski-Serra2014). Similar to suicide victims (Värnik et al., Reference Värnik, Kõlves, van der Feltz-Cornelis, Marusic, Oskarsson, Palmer, Reisch, Scheerder, Arensman, Aromaa, Giupponi, Gusmäo, Maxwell, Pull, Szekely, Sola and Hegerl2008; Cibis et al., Reference Cibis, Mergl, Bramesfeld, Althaus, Niklewski, Schmidtke and Hegerl2012; Bachmann, Reference Bachmann2018), the profile of MSSA attempters who die corresponds to a man over 65 years that used hanging as a method. MSSA attempters are older compared to other suicide attempters (Horesh et al., Reference Horesh, Levi and Apter2012; Giner et al., Reference Giner, Jaussent, Olié, Béziat, Guillaume, Baca-Garcia, Lopez-Castroman and Courtet2014; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi, Lee, Kim, Hong, Lee, Kweon, Lee and Lee2020), but younger than suicide victims (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2001).

The ‘gender paradox’ in suicide posits that women make more attempts but men die more often (Canetto and Sakinofsky, Reference Canetto and Sakinofsky1998; Schrijvers et al., Reference Schrijvers, Bollen and Sabbe2012). In our study, men represent 68.4% of deaths, spend more time in intensive care and have more somatic conditions than women. These differences could be explained by the choice of more lethal methods in men (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2003b) but even comparing similar methods men have higher mortality rates in our sample. However, the risk of suicide among women seems to be particularly high after an MSSA (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2004).

Two out of three MSSAs used DSP as a method for suicide. Similar results were found in previous studies with intoxications accounting for 57–79% of MSSAs (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2003b; Horesh et al., Reference Horesh, Levi and Apter2012; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Guo, Zhang, Wang, Jia and Xu2015; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi, Lee, Kim, Hong, Lee, Kweon, Lee and Lee2020). SA methods in our sample are thus closer to those of low-lethality SAs than to suicides if we compare with previous studies: (i) 81.7% of suicides used a highly lethal method against 17.6% in MSSAs (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2003b), (ii) DSP accounts for approximately two out of three SAs not requiring intensive care (Cibis et al., Reference Cibis, Mergl, Bramesfeld, Althaus, Niklewski, Schmidtke and Hegerl2012), but (iii) DSP accounts only for 12.7% of suicides in Europe (Värnik et al., Reference Värnik, Kõlves, van der Feltz-Cornelis, Marusic, Oskarsson, Palmer, Reisch, Scheerder, Arensman, Aromaa, Giupponi, Gusmäo, Maxwell, Pull, Szekely, Sola and Hegerl2008).

One in 10 patients with MSSA (10.5%) had multiple somatic comorbidities. Indeed, physical illnesses can precipitate MSSAs (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi, Lee, Kim, Hong, Lee, Kweon, Lee and Lee2020). Patients with somatic pathology are 2–3 times more likely to die by suicide compared to the general population in Taiwan (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chen, Chen and Jenkins2000), even more so in case of multiple co-morbidities or social isolation (Ahmedani et al., Reference Ahmedani, Peterson, Hu, Rossom, Lynch, Lu, Waitzfelder, Owen-Smith, Hubley, Prabhakar, Williams, Zeld, Mutter, Beck, Tolsma and Simon2017; Kennedy and Garmon-Jones, Reference Kennedy and Garmon-Jones2017). In the same vein, intensive care survivors have more risk of suicide after discharge than other inpatients (Fernando et al., Reference Fernando, Qureshi, Sood, Pugliese, Talarico, Myran, Herridge, Needham, Rochwerg, Cook, Wunsch, Fowler, Scales, Bienvenu, Rowan, Kisilewicz, Thompson, Tanuseputro and Kyeremanteng2021). According to a national population study, the interaction of psychiatric and somatic illnesses increases the risk of suicide (Qin et al., Reference Qin, Hawton, Mortensen and Webb2014), and this trend seems to be particularly significant in elderly men (Blasco-Fontecilla et al., Reference Blasco-Fontecilla, Baca-Garcia, Duberstein, Perez-Rodriguez, Dervic, Saiz-Ruiz, Courtet, de Leon and Oquendo2010). Somatic conditions often precipitate suicidal acts in the elderly, which present an elevated fatality rate post-MSSA. Physical pain interacts with psychological pain, cognitive impairments and loneliness facilitating more severe attempts in this age group (Conejero et al., Reference Conejero, Olié, Courtet and Calati2018). It should also be noted that the physical consequences of an MSSA may increase suicide risk and can hinder psychiatric care, especially after a violent SA (Persett et al., Reference Persett, Grimholt, Ekeberg, Jacobsen and Myhren2018). Overall mortality is sharply increased after violent self-harm, especially during the first year, and also among men and physically vulnerable persons (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Tan, Chen, Chen, Liao, Lee, Dewey, Stewart, Prince and Cheng2011; Bergen et al., Reference Bergen, Hawton, Waters, Ness, Cooper, Steeg and Kapur2012; Stenbacka and Jokinen, Reference Stenbacka and Jokinen2015; Goldman-Mellor et al., Reference Goldman-Mellor, Olfson, Lidon-Moyano and Schoenbaum2019; Vuagnat et al., Reference Vuagnat, Jollant, Abbar, Hawton and Quantin2019).

High levels of psychopathology increase the susceptibility to make an MSSA (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2003b). The diagnostic profile of MSSA patients (mood disorders, SUDs) in our study is similar to previous reports by Beautrais's group, which found high rates of current and lifetime mental disorders (around 90%), and previous SAs (23.6–52.7%) (Beautrais et al., Reference Beautrais, Joyce, Mulder, Fergusson, Deavoll and Nightingale1996, Reference Beautrais, Joyce and Mulder1998; Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2001). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was also more prevalent among MSSA survivors (Lopez-Castroman et al., Reference Lopez-Castroman, Jaussent, Beziat, Guillaume, Baca-Garcia, Olié and Courtet2015). Consistently with previous studies (Beautrais et al., Reference Beautrais, Joyce and Mulder1999; Gvion and Levi-Belz, Reference Gvion and Levi-Belz2018), SUDs and particularly AUDs were very frequent in our sample, one in three MSSA survivors (31.1%) had an AUD in the previous month (Beautrais et al., Reference Beautrais, Joyce and Mulder1999). Alcohol dependence more than doubles the risk of making an MSSA compared to the general population (Conner et al., Reference Conner, Beautrais and Conwell2003a), and drinking within 3 h of an SA causes a sixfold increase in the risk of MSSA (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Kresnow, Mercy, Potter, Swann, Frankowski, Lee and Bayer2001). In a prior study, the comorbidity of a mood disorder with alcohol dependence conveyed lower odds of an MSSA compared to a mood disorder alone (OR = 6 v. 17), but alcohol-dependent patients making MSSAs were more likely to have a mood disorder (Conner et al., Reference Conner, Beautrais and Conwell2003a, Reference Conner, Beautrais and Conwell2003b). Other SUDs, such as cannabis or tobacco dependence, have been strongly associated with MSSAs (Beautrais et al., Reference Beautrais, Joyce and Mulder1999; Lopez-Castroman et al., Reference Lopez-Castroman, Cerrato, Beziat, Jaussent, Guillaume and Courtet2016).

The psychiatric profiles of suicide victims and MSSAs present strong similarities. Mood disorders, SUDs and anxiety disorders are very frequent in both groups compared to the general population (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2001; Arsenault-Lapierre et al., Reference Arsenault-Lapierre, Kim and Turecki2004). Nevertheless, suicide victims appear to be several times more likely to present non-affective psychoses compared to MSSA survivors that in turn would be more likely to present anxiety disorders and mood disorders (Beautrais, Reference Beautrais2001, Reference Beautrais2003b). Compared with SAs not requiring critical care, psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, SUDs and SA recidivism are overrepresented in MSSAs (Giner et al., Reference Giner, Jaussent, Olié, Béziat, Guillaume, Baca-Garcia, Lopez-Castroman and Courtet2014; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi, Lee, Kim, Hong, Lee, Kweon, Lee and Lee2020).

In our study, only 32.5% of MSSA survivors were subsequently admitted in psychiatric hospitals. Male sex, long ICU stays and advanced age decreased the likelihood of admission in psychiatry after critical care according to our results. Between 2004 and 2011, 20% of all SAs hospitalised in French hospitals (MCO) were subsequently admitted in psychiatry (Chee and Jezewski-Serra, Reference Chee and Jezewski-Serra2014). These low rates are partly explained by admissions in psychiatric units within general hospitals, which are not differentiated in our study. In France, these units are mostly conceived to provide emergency psychiatric care in academic hospitals, and despite an increase in recent years they are still uncommon and most psychiatric care takes place in psychiatric clinics or hospitals (public or private). Besides, stays in psychiatric emergency units are short and most patients in our study were discharged to their homes (48.6%).

Given the low rate of psychiatric hospitalisations in our study, improving care pathways for MSSA survivors seems essential. Any intervention targeting this gap should focus on high comorbidity (especially between SUDs and mood disorders) and the male sex. Co-morbid conditions may increase attrition (Lamers et al., Reference Lamers, Hoogendoorn, Smit, van Dyck, Zitman, Nolen and Penninx2012) and decrease the efficacy of treatments. For instance, the response to antidepressants is modest in AUDs with comorbid depression (Agabio et al., Reference Agabio, Trogu and Pani2018) although it can be enhanced with cognitive behavioural therapy (Moak et al., Reference Moak, Anton, Latham, Voronin, Waid and Durazo-Arvizu2003). Concerning gender, men have less knowledge and more stigmatizing attitudes about suicide than women do (Batterham et al., Reference Batterham, Calear and Christensen2013), which may explain their tendency to seek help less often (Calear et al., Reference Calear, Batterham and Christensen2014). The 2-year period following discharge after an SA is at high risk for suicide (Tejedor et al., Reference Tejedor, Díaz, Castillón and Pericay1999; Parra-Uribe et al., Reference Parra-Uribe, Blasco-Fontecilla, Garcia-Parés, Martínez-Naval, Valero-Coppin, Cebrià-Meca, Oquendo and Palao-Vidal2017). Continuous psychiatric and somatic outpatient care is very important. A 7-day follow-up after discharge from a psychiatric hospital was associated with an important decrease in suicide rates in the 3-month period following discharge (While et al., Reference While, Bickley, Roscoe, Windfuhr, Rahman, Shaw, Appleby and Kapur2012). Specific training or sensibilisation of non-psychiatric teams about the risk of suicide and its management is important. Less than 70% of emergency physicians know how to assess the risk of suicide (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Sullivan, Manton, Espinola, Miller, Camargo, Boudreaux and ED-SAFE Investigators2013).

Non-psychiatric medical departments are not well-adapted to the management of suicide attempters (less communication, untrained teams) (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Hu and Tseng2009; Betz et al., Reference Betz, Sullivan, Manton, Espinola, Miller, Camargo, Boudreaux and ED-SAFE Investigators2013; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Evans and Larkins2016). Patients admitted for self-harm to non-psychiatric departments are more likely to die by suicide in the following year than those admitted to psychiatric units (Vuagnat et al., Reference Vuagnat, Jollant, Abbar, Hawton and Quantin2019). Consultation-liaison psychiatry (CLP) should identify and manage these cases to reinforce continuous care (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Müller, Meyer and Söllner2020), but the accessibility to CLP varies widely among hospitals (Olfson et al., Reference Olfson, Marcus and Bridge2014; Wood and Wand, Reference Wood and Wand2014; Wand et al., Reference Wand, Wood, Macfarlane and Hunt2016). According to one study, when CLP intervenes only 29.2% of violent or serious attempts are discharged (Cooper-Kazaz, Reference Cooper-Kazaz2013).

The incidence rate in our study is lower (45.7 per 1 00 000 person-years) compared to a Chinese study based on the 2009–2011 public health surveillance systems of three counties. However, their incidence rate included suicide deaths happening before arrival at the hospital (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Guo, Zhang, Wang, Jia and Xu2015). The incidence for all SAs (MSSAs included) was estimated to be 148.8 per 1 00 000 person-years in a US study (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Gallo and Tien2001).

Strengths and limitations of our study

The main limitation of this study is that it is based on administrative data, ICD-10 codes are mainly used for billing purposes by physicians in the hospital ward. They might vary according to the practitioner or the institution. Also, short stays, especially in services other than intensive care, may raise questions about the severity of the suicidal act, and important information such as suicidal intent or records of previous suicidality is not available in the database. Finally, the 2-year criterion we used to define a first MSSA is based on the diagnostic category of suicidal behaviour disorder, as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5), but it may not completely reflect true incidence. However, PMSI data provide exhaustive and updated information on all health establishments at the national level for almost 10 years. This information completes the profile of MSSA attempters outlined by clinical studies and confirms the epidemiological importance of MSSA, as well as the limitations of current approaches to ensure that survivors access psychiatric care.

Conclusions

MSSA survivors use more violent methods and have more serious somatic and psychiatric pathologies than low-lethality attempters. They are also at high risk of subsequent somatic complications or suicide. Very often they are discharged home instead of receiving inpatient psychiatric care, particularly those that are most at risk: men using violent methods or presenting comorbidities. The incidence of MSSAs is high, similar to that of suicides, and it seems essential to improve care pathways for MSSA survivors. This study needs to be extended with prospective data in order to better understand the consequences of MSSA and adapt care management.

Data

The data are not publicly available but will be provided upon request with the permission of the French Ministry of Health.

Author contributions

Jorge Lopez Castroman conceived and designed the study. Julien Corbé drafted the manuscript and managed the literature searches and analyses. Christine Montout and Thibault Mura performed the statistical analysis and analysed and interpreted the data. All authors revised the article critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. No one else fulfils the criteria but has not been included as an author. Christine Montout had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no interests that could be perceived as a possible conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.