Introduction

Since the 19th century, brief psychotic episodes (BPE) have been characterised as a divergent and shifting nosographic concept, providing a major challenge both for clinical practice and classification. Historically, their fleeting and dynamical nature constituted an early anomaly within the Kraepelinian dichotomous concept of psychoses (dementia praecox v. manic-depressive illness; Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1899). The historical development of operationalisations for BPE has been previously appraised (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Bonoldi, Hui, Rutigliano, Stahl, Borgwardt, Politi, Mishara, Lawrie, Carpenter and McGuire2016a) by our group. Briefly, World Health Organization includes the concept of acute and transient psychotic disorders (ATPD) in ICD-10 within the group of ‘schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders’ (World Health Organization, 1992), with six subtypes, including disorders defined by acute onset of frank psychotic symptoms (acute within 2 weeks; abrupt within 48 h) and complete recovery within 1–3 months even with antipsychotic treatment. However, the 11th edition of the ICD has narrowed the ATPD category to the subtype of acute polymorphic psychotic disorders (APPD) without the symptoms of schizophrenia (Castagnini and Foldager, Reference Castagnini and Foldager2014). DSM-5 includes brief psychotic disorder (BPD) within the ‘schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders’, defined by the presence of at least one across four of five core symptoms of schizophrenia (negative symptoms are not included): delusions, hallucinations, disorganised speech and grossly disorganised or catatonic behaviour (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Duration of the episode must be less than 1 month and sudden onset and polymorphic and fluctuating nature of symptoms are not mandatory criteria (Gaebel, Reference Gaebel2012). The paradigm of clinical high-risk states of psychosis (CHR-P) operationalised BPE not as frank psychotic disorder, but as a state of increased clinical risk for developing subsequent persistent psychotic disorders. Brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms (BLIPS) (Yung et al., Reference Yung, McGorry, McFarlane, Jackson, Patton and Rakkar1996) last less than 7 days and accommodate potential ‘transdiagnostic’ (Fusar-Poli, Reference Fusar-Poli2019; Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Solmi, Brondino, Davies, Chae, Politi, Borgwardt, Lawrie, Parnas and McGuire2019c) comorbidities. Brief intermittent psychotic symptoms (BIPS) exclude individuals with seriously disorganising and dangerous features (Miller et al., Reference Miller, McGlashan, Rosen, Cadenhead, Cannon, Ventura, McFarlane, Perkins, Pearlson and Woods2003) and extend the duration of brief psychotic symptoms up to 3 months.

Given these differences, in previous studies we employed meta-analyses to test the prognostic significance of these competing operationalisations. We found no difference in their risk of psychotic recurrence at any follow-up timepoint, but a lower risk of recurrence compared to first-episode remitting schizophrenia (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Bonoldi, Hui, Rutigliano, Stahl, Borgwardt, Politi, Mishara, Lawrie, Carpenter and McGuire2016a). We also demonstrated meta-analytically that, at 4.5 years follow-up, about 56% of patients with BPE retained their index diagnosis (prospective diagnostic stability) whereas 44% shifted to other diagnoses (prospective diagnostic change), schizophrenia being the most frequent one (21%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 16–25) (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Heslin, Stahl, Brittenden, Caverzasi, McGuire and Carpenter2016c). Other clinical outcomes such as remission, quality of life, vocational status and mortality have traditionally seen as more favourable than in schizophrenia (Pillmann and Marneros, Reference Pillmann and Marneros2005) but findings have been conflicting. Similarly, predictors of these outcomes appear patchy and inconsistent and require a systematic appraisal. These meta-analytic summaries had been completed more than 5 years ago, and several recent publications have emerged, which require periodical updates of the evidence. Our aim was to provide an updated systematic review and meta-analysis which comprehensively addresses for the first time multiple clinical outcomes in BPE encompassing psychotic recurrence, prospective diagnostic stability and change, remission, quality of life, functional/vocational status and mortality and systematically appraise the consistency of predictors of these outcomes.

Methods

This study (protocol registered on https://osf.io/5dw98) was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009) and the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie, Moher, Becker, Sipe and Thacker2000) (online Supplementary eTables 1 and 2).

Search strategy and selection criteria

A multistep systematic PRISMA-compliant literature search was performed for articles published from inception until 1st March 2021 (see the details in online Supplementary eMethods 1). The references of systematic reviews or meta-analyses that were retrieved during the systematic literature search were manually searched. Articles identified were screened as abstracts. The remaining articles were assessed for inclusion eligibility against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and decisions were made regarding their final inclusion in the meta-analysis.

The inclusion criteria were: (a) original studies, published in English; (b) conducted in individuals meeting BIPS or BLIPS criteria according to Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndromes (SIPS any version) (McGlashan TH, Reference McGlashan and Wood2010) or Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS any version) (Yung et al., Reference Yung AR, Yuen and McGorry2006); ATPD according to ICD (any version) criteria (World Health Organization, 1992); or BPD according to DSM (any version) criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and (c) reporting on at least one of meta-analytic outcomes (see below).

The exclusion criteria were: (a) reviews, conference proceedings or pilot data sets; (b) unpublished data; (c) studies evaluating BPE but using criteria different from those established above; (d) studies that did not report specific information on the ATPD/BPD/BIPS/BLIPS group alone, but reported composite results including other subgroups (e.g. attenuated psychosis syndrome, APS and genetic risk and deterioration syndrome, GRD) and (e) studies with samples of individuals with other persisting psychotic disorders (e.g. schizophrenia). For the meta-analyses we additionally excluded studies with overlapping datasets, selecting the largest and most recent data set. Disagreements in selection criteria were resolved through discussion and consensus with a senior researcher.

Outcome measures and data extraction

Two independent researchers extracted data. The primary outcome was risk of psychotic recurrence after at least 3 months since the index BPE. Secondary outcomes were the prospective diagnostic stability (defined as the proportion of baseline patients retaining the same ICD/DSM psychotic diagnosis over time) (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Heslin, Stahl, Brittenden, Caverzasi, McGuire and Carpenter2016c) or diagnostic change to any other mental disorder (defined as the proportion of baseline patients shifting to other ICD/DSM diagnoses at follow-up) (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Heslin, Stahl, Brittenden, Caverzasi, McGuire and Carpenter2016c), remission (defined as indicated in each study), quality of life (defined as indicated in each study, at baseline and/or follow-up), functional/vocational status (defined as indicated in each study at baseline and/or follow-up), mortality (number of patients deceased during the follow-up) or predictors of these outcomes (any regression models testing the association between factors and clinical outcomes, within longitudinal designs). When the predictors were not directly presented in the text, they were extracted from associated information (e.g. graphs); corresponding authors were also contacted to retrieve missing data. From each study, a predetermined set of variables characterising the study, outcomes or predictors was included (online Supplementary eMethods 2). Data were extracted closest to the follow-up time of interest. Disagreements in selection/extraction criteria were resolved through discussion and consensus with a senior researcher.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies, which has been repeatedly used (Catalan et al., Reference Catalan, Salazar de Pablo, Vaquerizo Serrano, Mosillo, Baldwin, Fernández-Rivas, Moreno, Arango, Correll, Bonoldi and Fusar-Poli2020). Studies were awarded a maximum of eight points on items related to the representativeness, exposure, outcomes, follow-up period and loss to follow-up.

Strategy for data synthesis

Meta-analyses were attempted when there were enough data for each outcome, otherwise outcomes were systematically described.

The primary meta-analytical outcome was risk of psychotic recurrence across BPE. This was estimated by extracting the raw counts of psychotic recurrence in individuals with an initial short BPE (defined according to the inclusion criteria (b)) at 6 months (including a 3–9 months range); 12 months (including a 10–18 months range); 24 months (including a 19–29 months range); 36 months (including ⩾30 months) follow-up. The primary effect size was the meta-analytical proportion of psychotic recurrence. Because the studies were expected to be heterogenous, random-effects models were used. Heterogeneity among study point estimates was assessed with the Q-statistics, with the proportion of the total variability in the effect size estimates being evaluated with the I 2 index (Lipsey and Wilson, Reference Lipsey and Wilson2001) which does not depend upon the number of studies included. The meta-analysis was stratified by operationalisations of BPE: BIPS, BLIPS, ATPD or BPD. The four main operationalisations (BIPS, BLIPS, ATPD and BPD) were compared testing for between-group heterogeneity (Q). Sensitivity analyses, removing one study at a time, were conducted to test the robustness of results. Publication bias was assessed with funnel plot inspection, Egger's test and meta-regression between the main outcome (psychotic recurrence) as dependent variable and sample size as independent variable.

Planned meta-analyses on secondary outcomes included: (i) prospective diagnostic stability (effect size: proportion), (ii) prospective diagnostic change to any other mental disorder (effect size: proportion), (iii) remission (effect size: standardised mean difference), (iv) quality of life (effect size: standardised mean difference) at baseline and/or follow-up, (v) functional/vocational status (effect size: proportion) at baseline and/or follow-up and (vi) mortality (effect size: proportion). The analyses (i–ii) were not conducted for BLIPS/BIPS because these do not correspond to standard ICD/DSM diagnoses at baseline and were conducted pooling all available studies and estimating the average follow-up time. Within analyses (i–ii), we additionally clustered the individual ICD/DSM diagnoses across NICE-compliant diagnostic spectra (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014): schizophrenia spectrum psychoses (schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder and schizoaffective disorder), affective spectrum psychoses (mania with psychosis and/or bipolar disorder with psychosis and/or depression with psychosis), other psychotic disorders and other (non-psychotic) mental disorders. For all outcomes (primary and secondary), we also sought to perform additional analyses restricted to the ATPD subtype which will be retained in the ICD-11 version (APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia). Sensitivity analyses were planned on the primary outcome, by excluding one study per time and rerunning the analyses. We performed multiple meta-regression analyses (i.e. employing two meta-regressor factors at the same time) of factors that were known to moderate transition risk when at least ten studies were available. The fixed meta-regressor factor was follow-up time, which was combined with: mean age, female ratio, publication year and study quality (NOS score). Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software v3.0 was used for the analyses (Borenstein et al., Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2013).

Results

Database

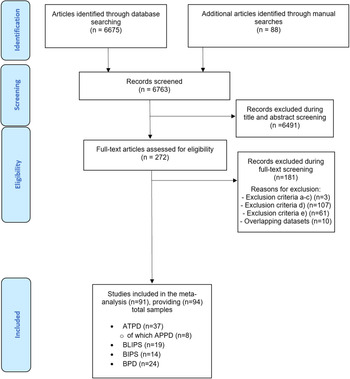

The systematic literature search (PRISMA flow-chart, Fig. 1) identified 91 independent articles, some of which contributed with more than one sample. The total number of samples (n = 94) included 37 ATPD, 24 BPD, 19 BLIPS and 14 BIPS samples. Eight samples (1262 patients) comprising ATPD subjects also provided data for APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia subtype. The total database included 15 729 individuals, with a mean age of 30.89 ± 7.33 years and an average female ratio of 60.0% (range from 8.3 to 86.2%). In total, 59% of the studies were conducted in Europe, 28% in Asia, 7% in North America, 3% in Australia, 2% in Africa and 1% in South America. The characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analyses are illustrated in online Supplementary eTable 3.

Fig. 1. PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Risk of psychotic recurrence of BPE

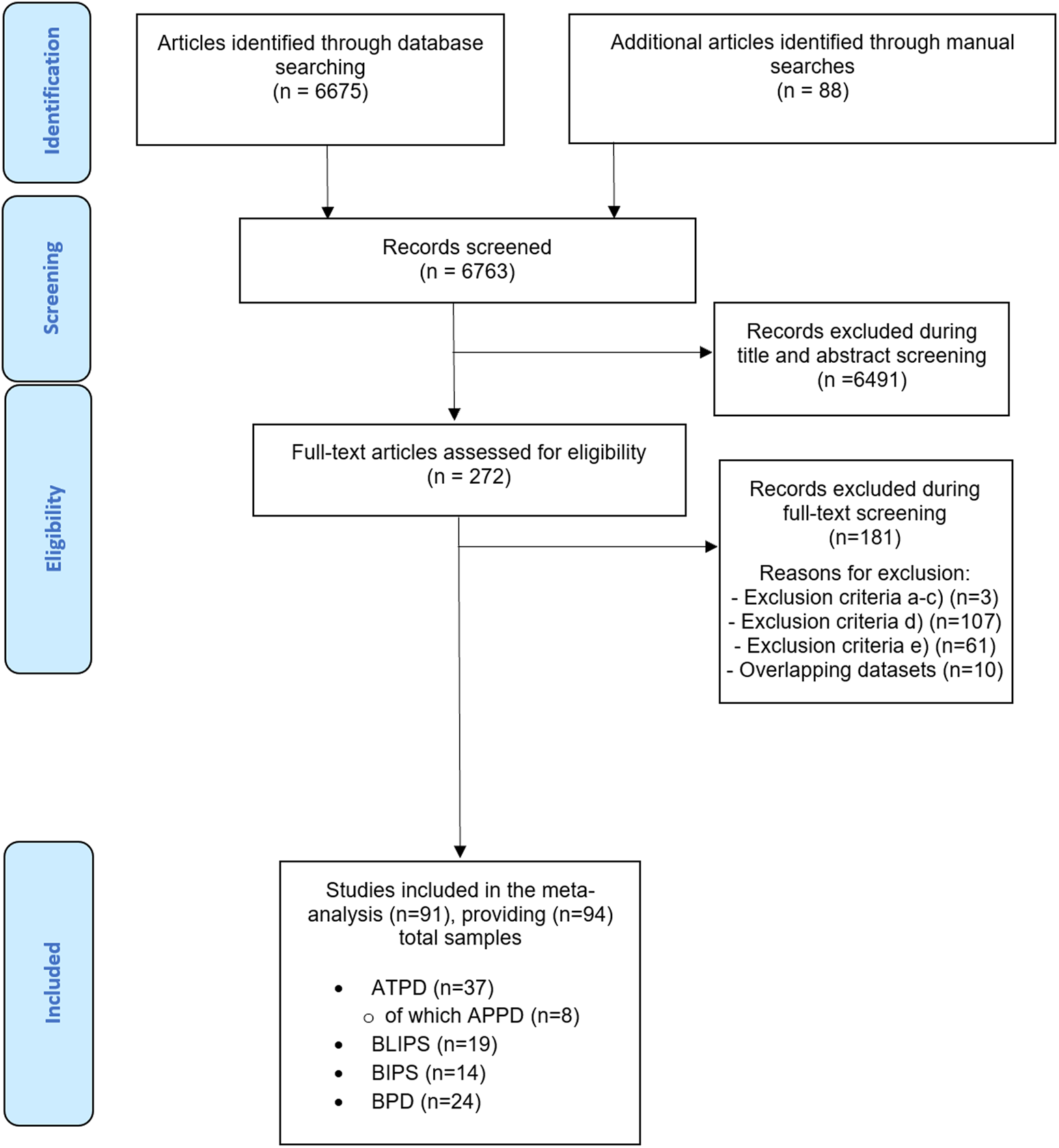

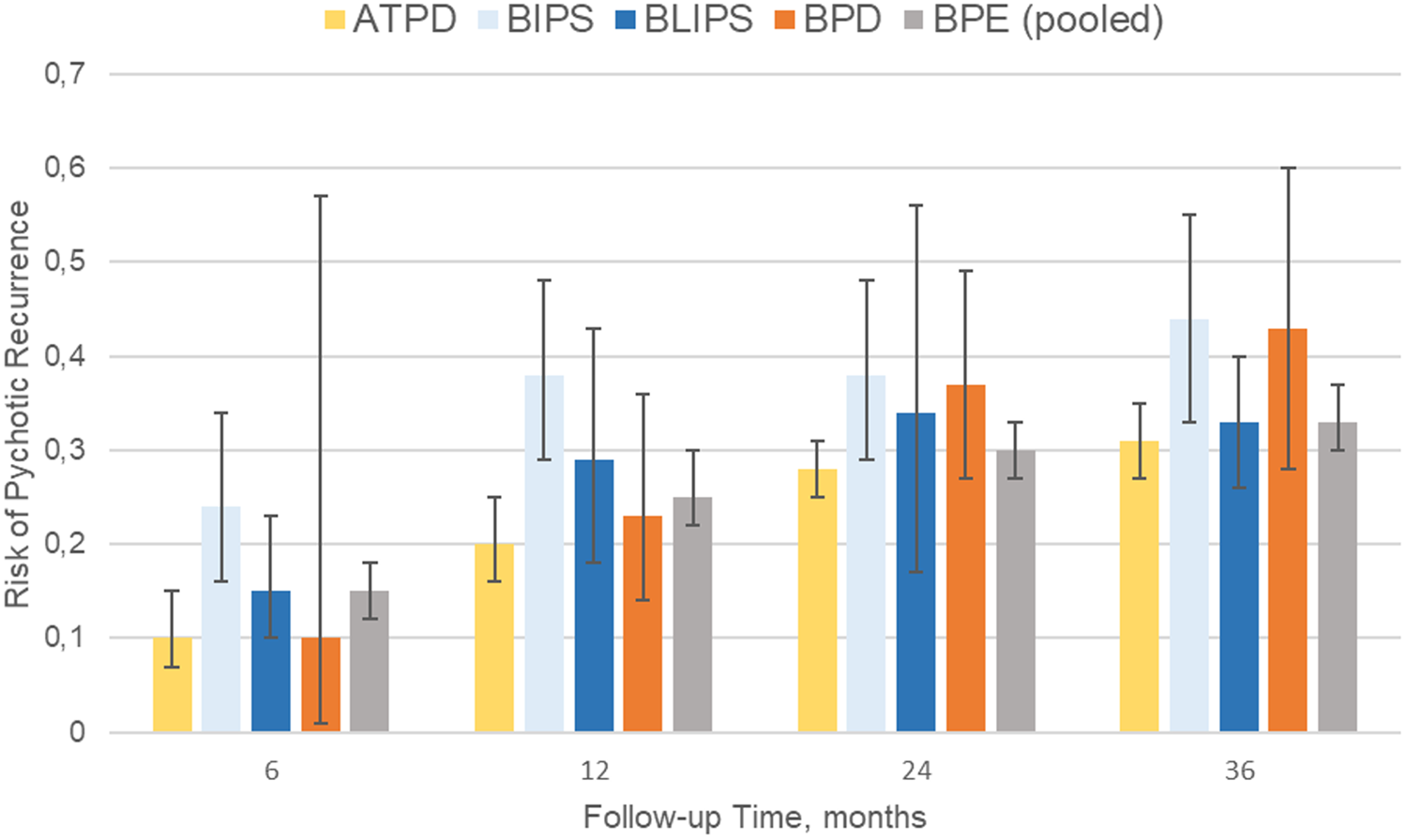

Ninety-one independent samples reported primary outcome data at different follow-up time points (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The meta-analytical risk of psychotic recurrence for all BPE was 15% (95% CI 12–18) at 6 months, 25% (95% CI 22–30) at 12 months, 30% (95% CI 27–33) at 24 months and 33% (95% CI 30–37) at ⩾36 months follow-up. The meta-analytical risk of psychotic recurrence for ATPD was 10% (95% CI 7–15) at 6 months, 20% (95% CI 16–25) at 12 months, 28% (95% CI 25–31) at 24 months and 31% (95% CI 27–35) at ⩾36 months follow-up; for BIPS, 24% (95% CI 16–34) at 6 months, 38% (95% CI 29–48) at 12 months, 38% (95% CI 29–48) at 24 months and 44% (95% CI 33–55) at ⩾36 months follow-up; for BLIPS, 15% (95% CI 10–23) at 6 months, 29% (95% CI 18–43) at 12 months, 34% (95% CI 17–56) at 24 months and 33% (95% CI 26–40) at ⩾36 months follow-up; for BPD, 10% (95% CI 1–57) at 6 months, 23% (95% CI 14–36) at 12 months, 37% (95% CI 27–49) at 24 months and 43% (95% CI 30–37) at ⩾36 months follow-up. There were significant between-group differences at 6 months (p = 0.020) and 12 months (p = 0.003), mostly driven by the BIPS group, but not at 24 (p = 0.110) and at ⩾36 (p = 0.100) months (Table 1). The risk of psychotic recurrence in APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia was 21% (95% CI 14–31) at mean follow-up of 51 months (online Supplementary eFig. 1).

Fig. 2. Meta-analysis of risk of psychotic recurrences in BPE. ATPD, acute and transient psychotic disorder; BIPS, brief intermittent psychotic symptoms; BLIPS, brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms; BPD, brief psychotic disorder.

Table 1. Meta-analysis of risk of psychotic recurrences in BPE

ATPD, acute and transient psychotic disorder; BIPS, brief intermittent psychotic symptoms; BLIPS, brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms; BPD, brief psychotic disorder; BPE, brief psychotic episodes.

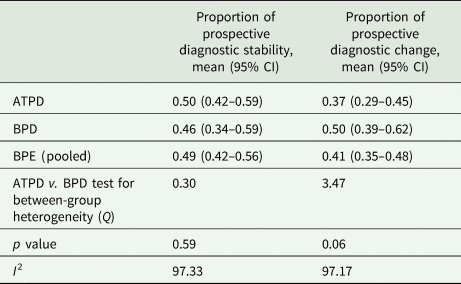

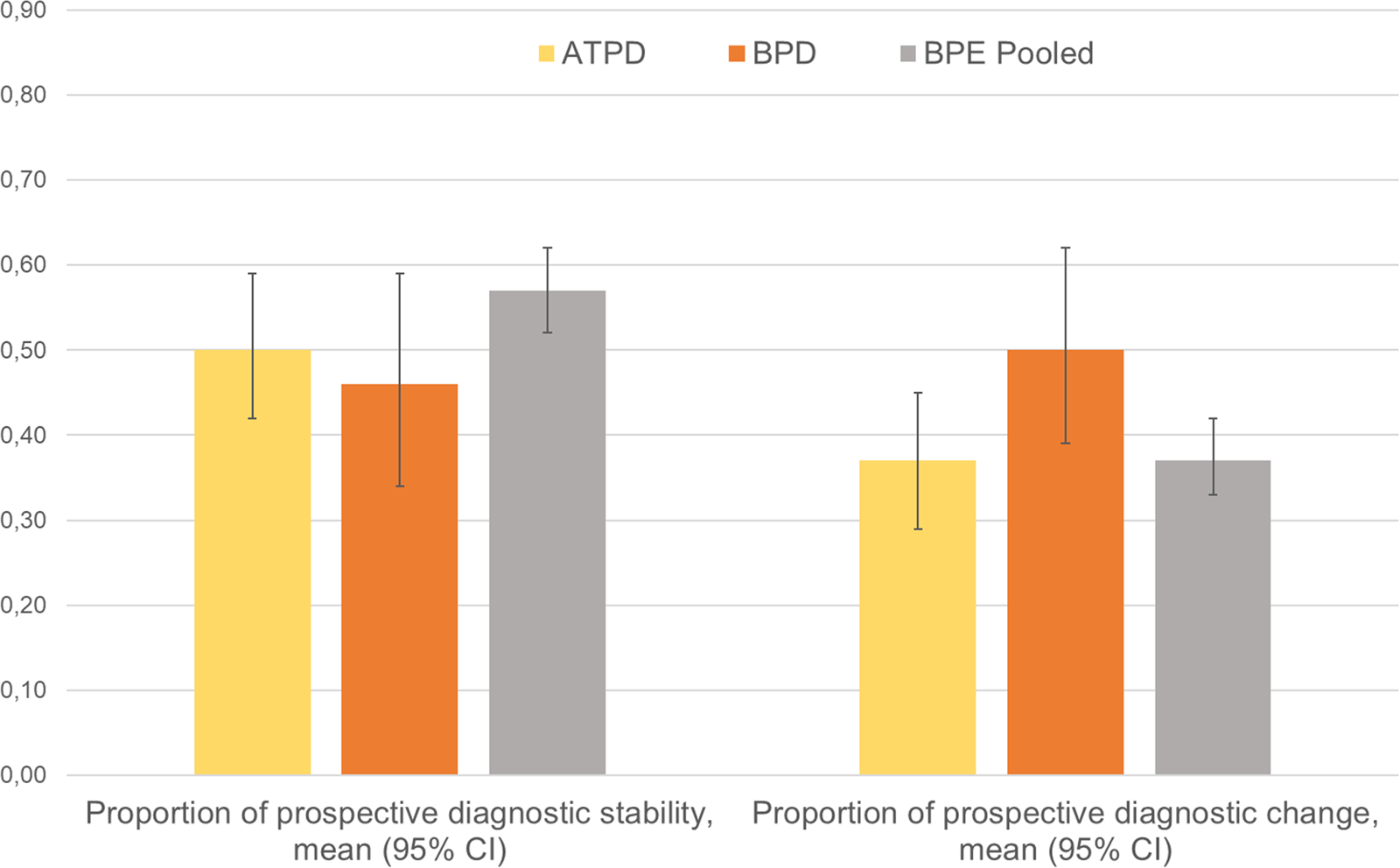

Proportion of prospective diagnostic stability and diagnostic change

Sixty-one independent samples (15 034 patients) reported prospective diagnostic stability or diagnostic change data at different follow-up time points (Table 2). The meta-analytical proportion of prospective diagnostic stability (average follow-up 47 months) was 49% (95% CI 42–56) for all BPE. It was 50% (95% CI 42–59) for ATPD and 46% (95% CI 34–59) for BPD (Table 2 and Fig. 3), with no significant between-group differences (p = 0.59).

Table 2. Prospective diagnostic stability and change of BPE

ATPD, acute and transient psychotic disorder; BPD, brief psychotic disorder; BPE, brief psychotic episodes.

Fig. 3. Meta-analysis of prospective diagnostic stability and change of BPE. ATPD, acute and transient psychotic disorder; BPD, brief psychotic disorder

Note: Diagnostic stability and diagnostic change values are not reciprocal, because they were calculated analysing different datasets.

The meta-analytical proportion of prospective diagnostic change (average follow-up 47 months) was 41% (95% CI 35–48) for all BPE: 37% (95% CI 29–45) for ATPD and 50% (95% CI 39–62) for BPD. There were no significant between-group differences (p = 0.063). Specifically, the meta-analytical proportion of diagnostic change to schizophrenia spectrum psychoses was 19% (95% CI 16–23) for all BPE: 19% (95% CI 15–24) for ATPD, 20% (95% CI 14–28) for BPD (between-group difference p = 0.770); to affective spectrum psychoses: 5% (95% CI 3–7) for all BPE, 1% (95% CI 0.6–2) for ATPD, 10% (95% CI 6–15) for BPD (between-group difference p < 0.01); to other psychotic disorders: 7% (95% CI 5–9) for all BPE, 3% (95% CI 2–5) for ATPD, 12% (95% CI 8–16) for BPD (between-group difference p < 0.010); to other (non-psychotic) mental disorders: 14% (95% CI 11–17) for all BPE, 14% (95% CI 12–18) for ATPD, 14% (95% CI 8–23) for BPD (between-group difference p = 0.950).

The meta-analytical prospective diagnostic stability for APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia (average follow-up 51 months) was 56% (95% CI 46–66), prospective diagnostic change was 34% (95% CI 24–46), proportion of diagnostic change to schizophrenia spectrum psychoses was 18% (95% CI 11–30) and of other (non-psychotic) mental disorders was 17% (10–26%) (online Supplementary eFig. 1). There were not enough data to meta-analyse change from APPD to affective spectrum psychoses or to other psychotic disorders.

Remission

There were not enough data to meta-analyse this outcome. Four studies (two BPD and two ATPD samples) (Rahm and Cullberg, Reference Rahm and Cullberg2007; Castagnini et al., Reference Castagnini, Bertelsen and Berrios2008; Castro-Fornieles et al., Reference Castro-Fornieles, Baeza, de la Serna, Gonzalez-Pinto, Parellada, Graell, Moreno, Otero and Arango2011; Bjorkenstam et al., Reference Bjorkenstam, Bjorkenstam, Hjern, Reutfors and Boden2013) reported proportion of remitted patients, defined as not having any mental disorder at follow-up, ranging from 14 (Castagnini et al., Reference Castagnini, Bertelsen and Berrios2008) to 67% (Rahm and Cullberg, Reference Rahm and Cullberg2007).

Quality of life

There were not enough data to meta-analyse this outcome. Two studies reported outcomes related to quality of life. One study (Aadamsoo et al., Reference Aadamsoo, Saluveer, Kueuenarpuu, Vasar and Maron2011) found that the World Health Organization Quality of Life scale (WHO-QoL) scores were not significantly different between ATPD and schizophrenia at baseline, but it became better in ATPD at follow-up. Another study (Satghare et al., Reference Satghare, Abdin, Shahwan, Chua, Poon, Chong and Subramaniam2020) reported that BPD, but not schizophrenia, is positively correlated with WHO-QoL scores at baseline.

Functional/vocational status

Twelve samples (907 patients) (nine ATPD, two BLIPS, one BPD) reported the functional/vocational status. The meta-analytical proportion of patients with BPE who were employed at baseline was 48% (95% CI 38–58). There were not enough data to meta-analyse this outcome at follow-up.

Mortality

There were not enough data to meta-analyse this outcome. Three studies (Castagnini et al., Reference Castagnini, Bertelsen and Berrios2008, Reference Castagnini, Foldager and Bertelsen2013a; Korner et al., Reference Korner, Lopez, Lauritzen, Andersen and Kessing2009), all including ATPD samples, independently reported a proportion of deaths of 17.0% at 60 months follow-up (Castagnini et al., Reference Castagnini, Bertelsen and Berrios2008), 5.6% at 84 months (Castagnini et al., Reference Castagnini, Foldager and Bertelsen2013a) and 33.5% at 96 months (Korner et al., Reference Korner, Lopez, Lauritzen, Andersen and Kessing2009).

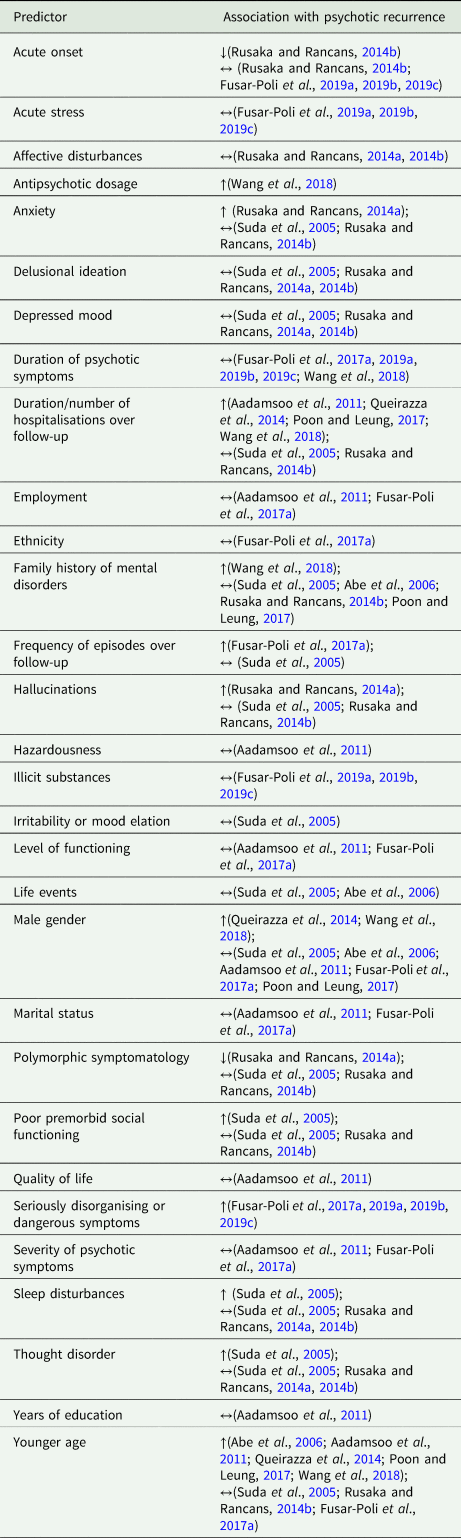

Predictors of clinical outcomes

Ten studies reported predictors for psychotic recurrence in BPE (Table 3). No factor was consistently associated with psychotic recurrence. Predictors of diagnostic stability partially overlap (but not consistently) with predictors of recurrence, with studies suggesting that older age at onset (Aadamsoo et al., Reference Aadamsoo, Saluveer, Kueuenarpuu, Vasar and Maron2011; Queirazza et al., Reference Queirazza, Semple and Lawrie2014; Poon and Leung, Reference Poon and Leung2017; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guo, Li, Tao, Meng, Wang, Deng and Li2018), female gender (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Burns, Amin, Jones and Harrison2004; Castagnini et al., Reference Castagnini, Foldager and Bertelsen2013b; Castagnini and Foldager, Reference Castagnini and Foldager2014; Queirazza et al., Reference Queirazza, Semple and Lawrie2014; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guo, Li, Tao, Meng, Wang, Deng and Li2018), abrupt onset (Sajith et al., Reference Sajith, Chandrasekaran, Unni and Sahai2002; Rusaka and Rancans, Reference Rusaka and Rancans2014a), seriously disorganising or dangerous symptoms (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, De Micheli, Rutigliano, Bonoldi, Tognin, Ramella-Cravaro, Castagnini and McGuire2017a), polymorphic symptomatology and absence of schizophrenic features at onset (Sajith et al., Reference Sajith, Chandrasekaran, Unni and Sahai2002; Aadamsoo et al., Reference Aadamsoo, Saluveer, Kueuenarpuu, Vasar and Maron2011; Salvatore et al., Reference Salvatore, Baldessarini, Tohen, Khalsa, Sanchez-Toledo, Zarate, Vieta and Maggini2011; Castagnini et al., Reference Castagnini, Foldager and Bertelsen2013b; Rusaka and Rancans, Reference Rusaka and Rancans2014a, Reference Rusaka and Rancans2014b) predict higher diagnostic stability (Lopez-Diaz et al., Reference Lopez-Diaz, Fernandez-Gonzalez, Lara and Ruiz-Veguilla2020). One study suggested that female gender was associated with early remission (Esan and Fawole, Reference Esan and Fawole2014). There were no predictors of quality of life, functional/vocational status or mortality.

Table 3. Predictors of psychotic recurrence in BPE (ATPD/BPD/BLIPS/BIPS)

BPE, brief psychotic episodes.

↑: predictor is associated with higher risk of psychotic recurrence.

↔: predictor is not associated with a change in psychotic recurrence.

↓: predictor is associated with lower risk of psychotic recurrence.

Sensitivity analyses

Excluding one study at a time at each follow-up point for primary outcome confirmed the robustness of the findings (sensitivity plots are presented in the online Supplementary eFigs 2a–d).

Heterogeneity and multiple meta-regression

Heterogeneity (I 2) ranged from 43.8% at 24 months to 84.6% at ⩾36 months for risk of psychotic recurrences (online Supplementary eResults 1). Significant multiple meta-regression analyses (online Supplementary eTable 4) associated the female ratio (β = 0.0040; f = 4.03, p = 0.022) with a lower proportion of recurrence; study quality (β = 0.0018; f = 3.47, p = 0.036) and with higher proportion of recurrence (scatterplots are depicted in online Supplementary eFigs 3 and 4).

Publication bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plot did not reveal publication bias. Egger's test for funnel plot asymmetry was not significant (p = 0.27). There was no meta-regression association between sample size and psychotic recurrence (online Supplementary eFigs 5a–c).

Discussion

To our best knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to have appraised multiple clinical outcomes across several operationalisations of BPE. We showed that these patients have a high risk of developing psychotic recurrences, in particular schizophrenia spectrum psychoses, and high proportion of baseline unemployment, while there were not enough data to explore remission, quality of life and mortality and no consistent factors predicting outcomes. As one in two patients presenting with short-lived psychotic episodes is at risk of recurrences, close monitoring and secondary preventive strategies should be systematically implemented for this vulnerable patient group.

This is the largest meta-analysis of BPE, which encompasses four operationalisations (ATPD, BPD, BLIPS and BIPS) over 91 independent articles and 15 729 individuals. Their mean age of about 31 years falls in the upper range of the 15–35-year window for highest risk of psychosis in the general population (Radua et al., Reference Radua, Ramella-Cravaro, Ioannidis, Reichenberg, Phiphopthatsanee, Amir, Yenn Thoo, Oliver, Davies, Morgan, McGuire, Murray and Fusar-Poli2018). A recent meta-analysis of epidemiological studies completed by our group confirmed that the peak age at onset is 18.5 years, and the median age of onset for ATPD is past 30 years (at 35 years), compared to 25 years for schizophrenia spectrum disorder (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo, Salazar de Pablo, Shin, Kirkbride, Kim, Kim, Carvalho, Seeman, Correll and Fusar-Poli2021). Despite a variable pattern of course and outcome reported by the individual studies, reflected by the high levels of heterogeneity in our analyses, we found that about one-third of patients with BPE will develop a psychotic recurrence after 3 years. In the short term, the BIPS group showed a higher risk of psychotic recurrence. This finding is in line with previous evidence highlighting the substantial higher level of risk in BLIPS/BIPS subgroups compared to other CHR-P subgroups (APS and GRD) (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Borgwardt, Woods, Addington, Nelson, Nieman, Stahl, Rutigliano, Riecher-Rossler, Simon, Mizuno, Lee, Kwon, Lam, Perez, Keri, Amminger, Metzler, Kawohl, Rossler, Lee, Labad, Ziermans, An, Liu, Woodberry, Braham, Corcoran, McGorry, Yung and McGuire2016b). The higher risk of recurrence in BIPS might be related to its 3-month duration criteria, compared to 7-days in BLIPS and 1 month in BPD and most ATPD subtypes. A longer duration of baseline psychotic symptoms is expected to increase the risk of recurrence (Aadamsoo et al., Reference Aadamsoo, Saluveer, Kueuenarpuu, Vasar and Maron2011; Queirazza et al., Reference Queirazza, Semple and Lawrie2014; Poon and Leung, Reference Poon and Leung2017; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guo, Li, Tao, Meng, Wang, Deng and Li2018). We also demonstrated that the presence of seriously disorganising or dangerous features within BLIPS/BIPS is associated with an extreme risk of psychotic recurrence over time (90% at 5-years) (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, De Micheli, Rutigliano, Bonoldi, Tognin, Ramella-Cravaro, Castagnini and McGuire2017a). However, these differences of risk for psychotic recurrences across operationalisations were not maintained in the long term. Importantly, we observed that the risk of psychotic recurrence continues increasing up to 3 years, suggesting that these patients should be offered clinical monitoring and relapse prevention strategies for at least 3 years after their index episode (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Rutigliano, Stahl, Davies, De Micheli, Ramella-Cravaro, Bonoldi and McGuire2017b, Reference Fusar-Poli, De Micheli, Signorini, Baldwin, Salazar de Pablo and McGuire2020; Rutigliano et al., Reference Rutigliano, Merlino, Minichino, Patel, Davies, Oliver, De Micheli, McGuire and Fusar-Poli2018). Unfortunately, first-episode services tend to discharge patients who have spontaneously remitted from an initial episode of psychosis, whereas CHR-P services typically cap their care at 2 years only (the average duration of care in these teams is of 24 months; Salazar de Pablo et al., Reference Salazar de Pablo, Estradé, Cutroni, Andlauer and Fusar-Poli2021). Consequently, patients with BPE have several unmet needs that are not addressed by current mental health services. For example, only 3% of BLIPS engage with the minimum effective dose of cognitive behavioural therapy, which is also of questionable efficacy for this patient population (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Davies, Solmi, Brondino, De Micheli, Kotlicka-Antczak, Shin and Radua2019a, Reference Fusar-Poli, De Micheli, Chalambrides, Singh, Augusto and McGuire2019b, Reference Fusar-Poli, Davies and Jauhar2021a).

We also showed that about half of patients with BPE will retain the initial diagnoses, compared to 90% in schizophrenia (90%) (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Heslin, Stahl, Brittenden, Caverzasi, McGuire and Carpenter2016c). About 19% of BPE is being rediagnosed as schizophrenia spectrum psychoses, 5% as affective spectrum psychoses (higher in BPD than ATPD), 7% as other psychotic disorders (higher in BPD than ATPD) and 14% other (non-psychotic) mental disorders. These findings corroborate the conceptual foundations of BPE, which are not static nosological entities (Ey, Reference Ey1954; Pillmann and Marneros, Reference Pillmann and Marneros2003), but have an intrinsically dynamic nature. Diagnostic changes are therefore to be expected, reflecting the natural trajectory of the disorders. This presents an unprecedented empirical prognostic and preventive opportunity for clinical practice, overcoming the sterile discussion about prospective instability of static diagnostic snapshots (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Hijazi, Stahl and Steyerberg2018).

Notably, our sensitivity analyses provided useful data in view of the forthcoming ICD-11 revisions. The APPD without symptoms of schizophrenia showed a 21% meta-analytic risk of psychotic recurrence (at 51 months), a prospective diagnostic stability comparable to the whole ATPD group (56 v. 49%), as well as a comparable proportion of diagnostic change to schizophrenia spectrum psychoses (18 v. 19%) and of other (non-psychotic) mental disorders (17 v. 14%). These findings do not align with the arguments made by the ICD-11 Panel that APPD is ‘not indicative of schizophrenia’ (Reed et al., Reference Reed, First, Kogan, Hyman, Gureje, Gaebel, Maj, Stein, Maercker, Tyrer, Claudino, Garralda, Salvador-Carulla, Ray, Saunders, Dua, Poznyak, Medina-Mora, Pike, Ayuso-Mateos, Kanba, Keeley, Khoury, Krasnov, Kulygina, Lovell, de Jesus Mari, Maruta, Matsumoto, Rebello, Roberts, Robles, Sharan, Zhao, Jablensky, Udomratn, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rydelius, Bährer-Kohler, Watts and Saxena2019). The ICD-11 field study also showed that the ICD-11 ATPD diagnostic reliability (moderate: kappa = 0.45) is lower than for the ICD-10 ATPD (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Sharan, Rebello, Keeley, Elena Medina-Mora, Gureje, Luis Ayuso-Mateos, Kanba, Khoury, Kogan, Krasnov, Maj, de Jesus Mari, Stein, Zhao, Akiyama, Andrews, Asevedo, Cheour, Domínguez-Martínez, El-Khoury, Fiorillo, Grenier, Gupta, Kola, Kulygina, Leal-Leturia, Luciano, Lusu, Nicolas, Martínez-López, Matsumoto, Umukoro Onofa, Paterniti, Purnima, Robles, Sahu, Sibeko, Zhong, First, Gaebel, Lovell, Maruta, Roberts and Pike2018). Some authors have argued that ICD-11 ATPD category is too narrow and may counter-productively reduce its clinical utility (Castagnini and Berrios, Reference Castagnini and Berrios2019).

We also uncovered gaps of knowledge because evidence relating to remission, functional status, quality of life and mortality in brief psychoses is still to sparse and insufficient. For example, most studies addressing quality of life focused on first-episode psychosis without distinguishing across short lived and persistent disorders (Sevilla-Llewellyn-Jones et al., Reference Sevilla-Llewellyn-Jones, Cano-Domínguez, de-Luis-Matilla, Espina-Eizaguirre, Moreno-Kustner and Ochoa2019; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Shahwan, Satghare, Chua, Verma, Tang, Chong and Subramaniam2019; Satghare et al., Reference Satghare, Abdin, Shahwan, Chua, Poon, Chong and Subramaniam2020). We were only able to meta-analyse the proportion of patients with brief psychoses who were employed at baseline (48%) and we uncovered no robust and replicated predictors of any outcomes in short-lived psychotic episodes. Our meta-regressions confirm previous findings underlining reduced risk for transition to schizophrenia in females (Queirazza et al., Reference Queirazza, Semple and Lawrie2014; Radua et al., Reference Radua, Ramella-Cravaro, Ioannidis, Reichenberg, Phiphopthatsanee, Amir, Yenn Thoo, Oliver, Davies, Morgan, McGuire, Murray and Fusar-Poli2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guo, Li, Tao, Meng, Wang, Deng and Li2018). Overall, it is unlikely that single prognostic factors can be robustly associated with this complex and evolving condition. Some multivariable prognostic models that can forecast clinical outcomes in patients with BPE have been developed (Lopez-Diaz et al., Reference Lopez-Diaz, Fernandez-Gonzalez, Lara and Ruiz-Veguilla2020; Fusar-Poli, Reference Fusar-Poli2021). We have recently developed and internally validated (3018 individuals with short-lived psychotic episodes, up to 8 years of follow-up) an individualised clinical prediction model based on Electronic Health Records which adequately predicts the long-term risk of psychotic recurrence in this patient group (prognostic accuracy = 0.7, Damiani et al., Reference Damiani, Rutigliano, Fazia, Berzuini, Bernardinelli and Fusar-Poli2021). This clinical prediction models retained adequate prognostic performance when tested in the context of the ICD-11 changes to this groups and could further be improved by incorporating a dynamic component (Lopez-Diaz et al., Reference Lopez-Diaz, Fernandez-Gonzalez, Lara and Ruiz-Veguilla2020; Studerus et al., Reference Studerus, Beck, Fusar-Poli and Riecher-Rössler2020) which better captures the evolving nature of this condition.

Overall, based on the findings of this study best practice affords for patients with short-lived psychotic episodes would require repeated clinical monitoring bolstered by complementary relapse prevention strategies (Alvarez-Jimenez et al., Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, O'Donoghue, Thompson, Gleeson, Bendall, Gonzalez-Blanch, Killackey, Wunderink and McGorry2016) for at least 3 years follow-up, to align with the current early intervention recommendations (Chandra et al., Reference Chandra, Patterson and Hodge2018). At a research level, larger prospective studies with a harmonised set of assessment and outcome measures are needed to further advance precision psychiatry efforts that are essential in this field. Future clinical and research perspective have been fully elaborated in an independent study (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Salazar de Pablo, Rajkumar, Lopez-Diaz, Malhotra, Heckers, Lawrie and Pillmann2021b). The limitations are appended in the online Supplementary eLimitations.

Conclusions

Short-lived psychotic episodes are associated with a high risk of psychotic recurrences, in particular schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Other clinical outcomes remain relatively underinvestigated. There are no consistent prognostic/predictive factors.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000548

Financial support

None.

Conflict of interest

PFP received honoraria or grant fees from Lundbeck, Angelini and Menarini in the past 36 months outside the current work.

Availability of data and materials

The authors give no permission to share raw data.