INTRODUCTION

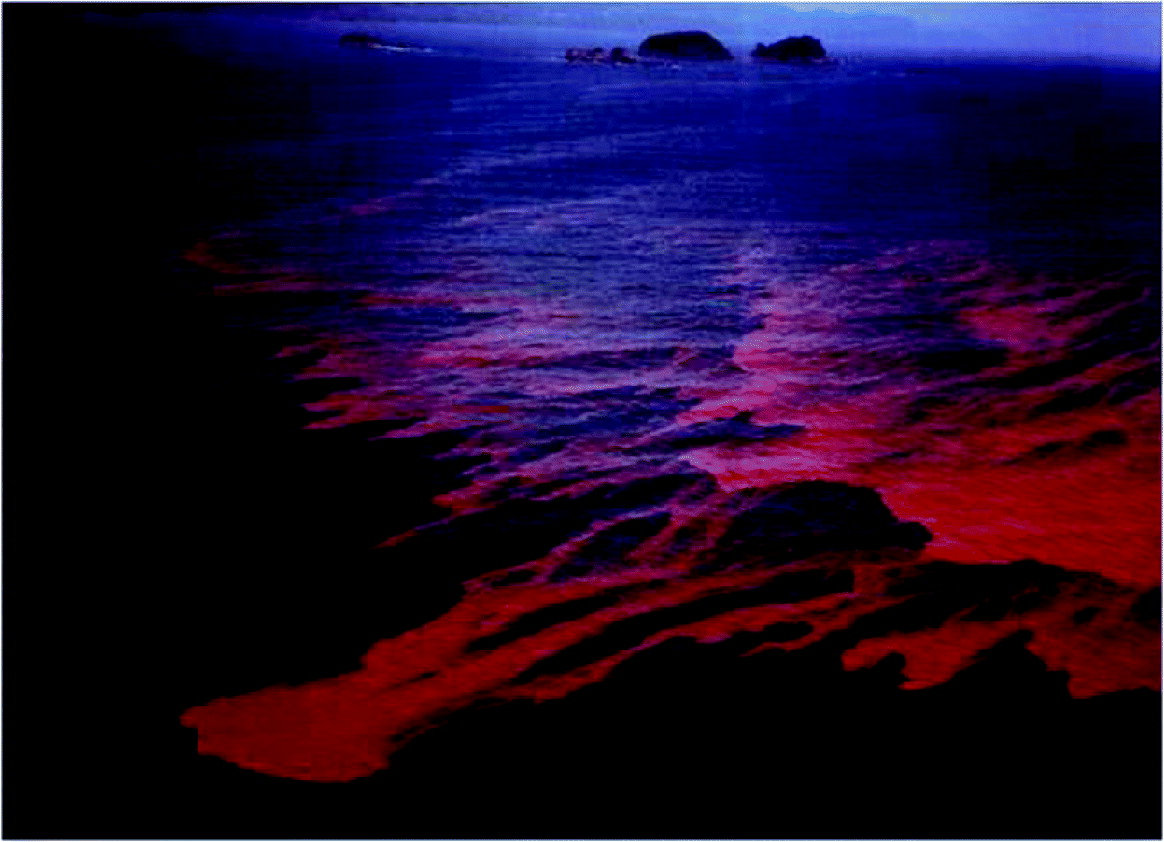

Shellfish are a rich source of protein, essential minerals and vitamins A and D and they feed mainly on marine microalgae. The importance of algae in the food chain arises from the fact that they are the only organisms that can readily make long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and the potential beneficial role of shellfish and finfish in the human diet has been attributed to the presence of oils that are rich in PUFAs [Reference Martinez, Dubinsky and Archer1]. Bivalve molluscs filter large volumes of water when grazing on microalgae, and can concentrate both bacterial pathogens and phycotoxins [Reference Huss2]. A range of human illnesses associated with shellfish consumption have been identified as being due to toxins that are produced by marine microalgae. When algae populations increase rapidly to form dense concentrations of cells they may form visible blooms, the so-called ‘red tides’ (Fig. 1), but blooms are not always visible as they may not be coloured and they can proliferate well below the surface. The term ‘harmful algal blooms’ (HABs) is preferred and these events can have negative environmental impacts including oxygen depletion of the water column and damage to the gills of fish. Moreover, toxin-producing algae can cause mass mortalities of fish, birds and marine mammals and human illness via consumption of seafood. It is estimated that only 60–80 species of about 4000 known phytoplankton are potentially toxin-producing and capable of producing HABs [Reference Smayda3]. Maximum toxin levels permitted in shellfish are controlled by national and international regulations and new analytical methods have been developed for the determination of toxins in shellfish, especially liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS). These methods have recently been reviewed and will not be discussed in detail [Reference James and Pico4]. The European Food Standards Agency has recently published a scientific opinion on marine biotoxins with proposals to lower some toxin limits and other measures that will hasten the replacement of mouse bioassay (MBA) methods that have traditionally been used to monitor toxin levels in shellfish for human consumption [5]. Unfortunately, the lack of clinical testing methods has led to a large underestimation of the incidence of human poisonings due to algal toxins, especially since many of the symptoms are similar to viral and bacterial infections. In addition, only acute intoxications due to algal toxins are recognized and there is very little knowledge of the human impacts due to chronic exposure to these toxins. The high potency and target specificity that many of these marine toxins possess has led to their exploitation as research tools [Reference Fusetani, Kem, Fusetani and Kem6].

Fig. 1. A dramatic algal bloom (red tide) in the South China Sea. This bloom, Noctiluca scintillans, was non-toxic. (Reproduced with permission of Springer SBM NL. In: Okaichi T, Fukuyo Y, eds. Red Tides, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2004.)

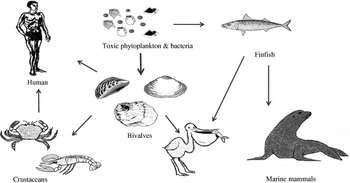

The main vectors of algal toxins to humans are filter-feeding bivalve molluscs and herbivorous finfish that ingest toxic algae (Fig. 2). The bivalve molluscs that are mainly affected with algal toxins include mussels, clams, scallops and oysters. Although crustaceans can also be contaminated with toxins, the extent of toxicity is generally low and the incidences of human intoxications due to crustacean consumption are rare. Other significant environmental impacts of HABs include major fish kills and large mortalities to birds and marine mammals [Reference Aune and Botana7, Reference Hallegraeff8]. One of the most dramatic events involving sea mammals was the extensive mass mortalities to sea lions in California due to domoic acid (DA) intoxication where the main vector was anchovy [Reference Scholin9]. Figure 2 summarizes the interrelationships and potential vectors for toxins arising from HABs but the toxic impact to humans is predominantly from shellfish consumption. Bivalve shellfish graze on algae and concentrate toxins, if present, very effectively.

Fig. 2. The toxin cycle: diagram illustrating the interrelationships between harmful algae and shellfish, finfish, birds and mammals.

Historically, there have been sporadic reports of shellfish poisoning; one fatal incident that occurred in British Columbia in 1793 was reported by Captain Vancouver and the earliest scientific reference to shellfish poisoning appeared in 1851 [Reference Chevallier10]. Prohibitions regarding the consumption of shellfish are found in several cultures and, together with religious beliefs, this has limited the role of shellfish as a potential food source. Such prohibitions are found in the Old Testament:

These ye shall eat of all that are in waters: all that have fins and scales shall ye eat: And whatsoever hath not fins and scales ye may not eat; it is unclean unto you. (Deuteronomy 14: 9–10; King James Version)

In this review, five major human toxic syndromes caused mainly by the consumption of bivalve molluscs contaminated by algal toxins are discussed (Table 1), together with the identification of the increased risks to humans of shellfish toxicity.

Table 1. Confirmed outbreaks of human poisonings due to shellfish toxins

PSP, Paralytic shellfish poisoning; DSP, Diarrhoetic shellfish poisoning; NSP, Neurotoxic shellfish poisoning; ASP, Amnesic shellfish poisoning; AZP, Azaspiracid poisoning.

SHELLFISH TOXIC SYNDROMES

Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP)

Mild symptoms include a tingling sensation or numbness around the lips which gradually spreads to the face and neck, accompanied by a prickly sensation in fingertips and toes. Greater intoxications induce headache, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea with increasing muscular paralysis and pronounced respiratory difficulty. In the absence of artificial respiration there is a high risk of death as a consequence of acute PSP intoxication [Reference Aune and Botana7]. The onset of symptoms of PSP in humans is dose dependent and can occur rapidly (within 30 min) after the consumption of shellfish. PSP toxins are collectively called saxitoxins (STXs) and at least 21 analogues of these cyclic guanidines are known in shellfish, with saxitoxin (Fig. 3 a) being the most common toxin. STXs exert their effect by a direct binding on the voltage-dependent sodium channel blocking the influx of sodium and the generation of action potentials in nerve and muscle cells, leading to paralysis [Reference Narahashi and Tu11]. The primary site of action of STXs in humans is the peripheral nervous system. The lethal dose in humans is 1–4 mg STX, or equivalent STXs, and since levels up to 100 μg STX equivalents/g shellfish have been reported, consumption of only a few contaminated shellfish have proved fatal in these rare cases. However, hospitalization of affected individuals is critical to deal with respiratory paralysis and STXs clear from the blood within 24 h leaving no organ damage or long-term effects [Reference Levin12]. Saxitoxin has reached notoriety by being included, along with ricin, in the Schedule 1 list of the Chemical Weapons Convention. Detection and control of PSP toxins in shellfish is less problematic than the control of lipophilic toxins. PSP toxins are efficiently extracted from shellfish tissues using a strong acid and a MBA has been validated as an official method by AOAC International [Reference Hellrich13].

Fig. 3. Structures of the most abundant toxin responsible for each of the five shellfish toxic syndromes; (a) saxitoxin (PSP), (b) okadaic acid (DSP), (c) brevetoxin (NSP), (d) domoic acid (ASP), (e) azaspiracid (AZP).

Dinoflagellates that produce STXs belong to three genera; Alexandrium, Gymnodinium and Pyrodinium and HABs involving blooms of these dinoflagellates occur in both Northern and Southern Hemispheres [Reference Hallegraeff8] (Table 2). It has been estimated that there are 2000 human intoxications per year and PSP outbreaks are seasonal [Reference Gessner and Middaugh14, Reference Van Dolah15]. Although there is anecdotal evidence of human intoxications associated with shellfish for centuries, a PSP outbreak that occurred in northern California in 1927 led to a major investigation of this phenomenon. Poisoning of 102 individuals from mussel consumption caused six deaths [Reference Sommer and Meyer16]. PSP outbreaks have occurred on both the eastern and western coastlines on North America, with Alaska being particularly badly affected and toxic events have been reported for more than 130 years [Reference Prakash, Medcof and Tennant17, Reference Gessner and Botana18]. Large marine mammals have also been affected by PSP and 14 humpback whales died in Cape Cod Bay in 1987 from exposure to STXs where mackerel was suspected to be the main vector [Reference Anderson19].

Table 2. Seafood toxic syndromes, toxins and the phytoplankton source of toxins

Although STXs are detected in the coastal waters and shellfish in many European countries, human intoxications are rare. In the 1970s, there were several PSP intoxications involving 80–120 individuals, caused by mussels produced in Spain, Portugal and the UK [Reference Anderson, Sullivan and Reguera20–Reference Ingham, Mason and Wood22] but implementation of good regulatory control has effectively eliminated further major outbreaks. There have been repeated PSP outbreaks in Chile and Argentina during the past 40 years, with 21 PSP deaths reported in Chile since 1991 [Reference Lagos23], and these investigations included one of the rare identifications of toxins in the body fluids of victims [Reference García24]. In the Philippines, there have been an estimated 2000 cases of PSP between 1983 and 1998, with 115 deaths [Reference Jacinto, Azanza RV, Velasquez, Siringan and Wolanski25]. Blooms of Pyrodinium spp. were the main cause of these intoxications and these blooms have spread throughout the tropical Pacific region. Climate change has been implicated with an apparent correlation between these HABs and the occurrence of El Niño Southern Oscillation events [Reference Maclean26]. PSP events in geographically remote locations cause higher death rates due to the lack of hospital facilities with respiratory support equipment.

Diarrhoetic shellfish poisoning (DSP)

DSP is a gastrointestinal illness and the main symptoms are diarrhoea followed by nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramps. DSP can occur within 30 min to a few hours after ingestion of contaminated shellfish and complete recovery occurs within 3 days. Since clinical tests are rarely used for DSP toxins, this condition is often confused with bacterial enterotoxin poisoning. DSP is caused by the ingestion of contaminated filter-feeding bivalve molluscs, especially mussels and scallops, where the lipophilic toxins are accumulated mainly in the digestive glands (hepatopancreas) [Reference Murata27].

DSP toxins were originally divided into three different structural classes: (a) okadaic acid (OA) (Fig. 3 b) and its analogues, dinophysistoxins (DTXs), (b) pectenotoxins (PTXs) and (c) yessotoxins (YTXs) [Reference Yasumoto28]. However, YTXs have now been excluded from the DSP classification because they are not orally toxic and do not induce diarrhoea [Reference Ogino, Kugami and Yasumoto29, Reference Aune30]. PTXs and YTXs are toxic to mice upon intraperitoneal injection, which is the official, but primitive, DSP testing procedure. However, no case of human poisoning due to these toxins has been reported. The strange scenario when using the official MBA is that the least toxic substances, YTXs, elicit the highest toxic response [Reference Aune and Botana7]. Not only are these lethal bioassays prohibited in several countries, including Germany, The Netherlands and Sweden, alternative methods for toxin determination can only be implemented in the EU when they have been validated against the MBA which itself has never been validated [31]. A recent pronouncement from the European Food Safety Authority belatedly acknowledged the unacceptable current regulatory situation and stated [5]:

The mouse bioassay (MBA) is the official reference method for lipophilic biotoxins. The Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM Panel) noted that this bioassay has shortcomings and is not considered an appropriate tool for control purposes because of the high variability in results, the insufficient detection capability and the limited specificity.

The mechanism of action of the OA group toxins is via inhibition of serine-threonine protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) [Reference Bialojan and Takai32], which plays important roles in many regulatory processes in cells. OA probably causes diarrhoea by stimulating phosphorylation of proteins that control sodium secretion in intestinal cells [Reference Cohen, Holmes and Tsukitani33]. Protein phosphatase assays are very sensitive and can be readily applied for detecting OA and analogues in shellfish but LC–MS methods are more widely used [Reference Draisci34, Reference James and Botana35]. Although DSP is not fatal, this type of poisoning deserves attention, because in addition to the severe acute effects, the chronic effects may be important as OA and DTX1 have been shown to be potent tumour promoters [Reference Suganuma36, Reference Fujiki37]. A major risk factor for colorectal cancer from shellfish consumption has been proposed due to the presence of DSP toxins [Reference Manerio38].

The first confirmed outbreak of DSP occurred in Japan in the late 1970s with 164 cases of shellfish poisoning [Reference Yasumoto, Oshima and Yamaguchi39]. There were 34 outbreaks of DSP in Japan between 1976 and 1984, affecting more than 1000 people [Reference Kawabata, Natori, Hashimoto and Ueno40]. DSP outbreaks have involved large population numbers and have affected the greatest number of individuals compared to the other shellfish toxic syndromes (Table 1). In Europe, DSP outbreaks involving several thousand individuals have been reported since 1978 in France [Reference van Egmond41, Reference Belin, Smayda and Shimizu42], Norway and Denmark [Reference Gestal-Otero and Botana43], Spain [Reference Gestal-Otero and Botana44, Reference Durborow45] and mussels exported from Ireland have caused DSP outbreaks throughout Europe [Reference Carmody, James and Kelly46]. Despite this DSP monitoring, mussels from Denmark caused DSP intoxications to more than 1000 individuals in Belgium [Reference De Schrijver47]. DSP is now recognized as a worldwide problem and also affects Canada, Chile, Argentina and New Zealand (Table 1).

DSP toxins are produced by the dinoflagellates, Dinophysis spp. and Prorocentrum spp. (Table 2) and their toxin profiles can vary within a single species [Reference Murakami, Oshima and Yasumoto48–Reference Fernández Puente50]. In Europe, OA and its isomer, DTX2, are the predominant DSP toxins and they co-occur in shellfish from Ireland [Reference Carmody, James and Kelly46], Portugal and Spain [Reference Blanco and Lassus51]. DTX1, the methyl analogue of OA, is the predominant DSP toxin in Japan [Reference Yasumoto49, Reference Suzuki52]. The regulatory level for these toxins in Europe is currently 0·16 μg/g.

Neurotoxic shellfish poisoning (NSP)

NSP is a illness caused by the consumption of bivalve molluscs contaminated with neurotoxins that are produced by the marine dinoflagellate, Karenia brevis (formerly known as Gymnodinium breve and Ptychodiscus brevis) [Reference Baden53, Reference Steidinger, Baden and Spector54]. Brevetoxin (Fig. 3 c) and its analogues can also affect finfish, aquatic mammals and birds and this topic has been recently reviewed [Reference Furey, Botana and Hui55, Reference Watkins56]. The symptoms of NSP include gastroenteritis and neurological problems [Reference Baden53]. Brevetoxin-producing HABs have caused problems in the Gulf of Mexico for many decades and have been responsible for respiratory problems and eye irritation in humans due to exposure to aerosol sprays along Florida beaches [Reference Furey, Botana and Hui55]. Brevetoxins have also been responsible for the deaths of large marine animals, including manatees and bottlenose dolphins [Reference Flewelling57]. In New Zealand, brevetoxins have also caused problems and new analogues have been identified [Reference Morohashi58, Reference Sim and Wilson59]. The first confirmed NSP outbreak in New Zealand occurred in 1993, affected 186 individuals, and caused both gastrointestinal symptoms and respiratory problems due to aerosol inhalation (Table 1) [Reference Sim and Wilson59].

In humans, the onset of symptoms of NSP occurs within 0·5–3 h after consumption of shellfish and can include gastroenteritis, chills, sweats, hypotension, arrhythmias, numbness, peripheral tingling and, in severe cases, broncho-constriction, paralysis, seizures and coma. NSP symptoms can persist for a few days [Reference Baden53, Reference Morris60, Reference Poli61].

In addition to ingestion, the second route of exposure to brevetoxins is by inhalation of sea spray and this affects individuals who are near to a beach. K. brevis is a very fragile dinoflagellate and during rough seas this organism readily ruptures releasing toxins into the water. This exposure to aerosols containing brevetoxins can cause irritation of the eyes and nasal membranes, as well as respiratory problems [Reference Fleming, Backer and Baden62].

The mode of action of brevetoxins is by receptor binding to the sodium channels which control the generation of action potentials in nerve, muscle and cardiac tissue, enhancing sodium entry into the cell. This leads to the incessant activation of the cell which causes paralysis and fatigue of these excitatory cells [Reference Dechraoui63]. A recent NSP outbreak in Florida affected 20 individuals, of which seven were hospitalized. Six individuals complained of uncontrolled muscle contractions and psychotic outbursts [Reference Watkins56].

The monitoring of shellfish for NSP has traditionally involved MBAs that involve a non-specific extraction process but this test can be effective for control in situations where other lipophilic toxins are not prevalent. The action level is 20 mouse units (MU) per 100 g shellfish tissue which is equivalent to 0·8 μg brevetoxin (PbTx-2)/g tissues [Reference Watkins56]. There are a number of sensitive receptor-binding assays that utilize the specific binding of brevetoxins to sodium channels [Reference Poli, Rein and Baden64]. LC–MS is the only method for identifying individual brevetoxins in seafood [Reference Furey, Botana and Hui55]. Overall, it can be concluded that NSP is relatively rare [Reference Watkins56], it is not geographically widespread and therefore poses the least threat to human health of the five toxic syndromes discussed in this review.

Amnesic shellfish poisoning (ASP)

ASP first came to attention in Canada in 1987 when human fatalities occurred from eating mussels (Mytilus edulis) cultivated in Prince Edward Island [Reference Perl65]. In addition to gastrointestinal disturbance, unusual neurological symptoms, especially memory impairment, were observed. Of the 107 cases involved in this ASP event, three individuals died within 18 days after admission to hospital [Reference Todd66]. The neurological symptoms included headache, confusion, disorientation, seizures and coma within 48–72 h. However, the permanent loss of short-term memory in some of the survivors led this toxic syndrome to be named ASP. Epidemiological studies revealed age-dependent responses to ASP. Those aged <40 years were more likely to suffer gastrointestinal problems whereas individuals aged >50 years were more likely to suffer from memory loss [Reference Todd66]. DA was identified as the causative toxin (Fig. 3 d) [Reference Wright67] and a short time later, marine diatoms of the Pseudonitzschia spp. were identified as the source of this toxin [Reference Bates68]. DA was a previously known marine natural product and was originally discovered in seaweed in Japan where the latter was used for its anthelminthic and insecticidal properties [Reference Daigo69]. In addition to mussels, DA can enter the food chain through vectors such as scallops, razor clams and crustaceans [Reference Wekell70–Reference Powell72]. There was a second report of human intoxications from consumption of razor clams, cultivated in Washington State, USA, but only two individuals experienced slight neurological problems [Reference Wright73].

Although there are many analytical methods for the determination of DA in seafood, liquid chromatography with ultra-violet detection is used by most regulatory agencies. The permitted limit of 20 μg DA/g shellfish tissue has been generally adopted [Reference Lawrence, Charbonneau and Menard74]. DA is a tricarboxylic amino acid and analysis is complicated somewhat by the presence of isomers of DA, as well as tryptophan, in naturally contaminated samples [Reference López-Rivera75]. There have been many worldwide reports of DA contamination of seafood and mortalities to marine animals and birds [Reference Beltran76]. An event that generated worldwide publicity was when 70 sea lions were washed up onto beaches in California. It was evident that they were suffering from neurological problems including seizures and 47 animals died. DA was identified in faecal samples from these animals and in anchovies collected nearby [Reference Scholin9].

In 1991, an outbreak of DA poisoning was reported in Monterey Bay, California, USA, where pelicans and cormorants were behaving strangely, e.g. vomiting, exhibiting unusual head movements, scratching, with many deaths [Reference Work77]. In this case the vector was the northern anchovy and it is probable that the making of the Alfred Hitchcock film The Birds was prompted by a similar event that happened in the summer of 1961, near Santa Cruz in California. Flocks of shearwaters began acting erratically, flying into houses and cars, pecking people, breaking windows and vomiting. These ‘strange’ events were reported in local newspapers and these clippings were included with Alfred Hitchcock's studio proposal to make the film, based on Daphne du Maurier's novella. In subsequent years, several similar incidents occurred along the same coastline which have been attributed to DA produced by blooms of Pseudonitzschia spp. [Reference Trainer, Hickey, Bates and Walsh78].

Soon after the establishment of monitoring programmes in Europe, DA was found in shellfish from Galicia, Spain [Reference Miguez, Luisa Fernandez, Fraga, Yasumoto, Oshima and Fukuro79], Ireland [Reference James80], Portugal [Reference Vale and Sampayo81], Scotland [Reference Hess82] and France [Reference Amzil83]. In Ireland, only the king scallop (Pecten maximus) exhibited high levels of toxin. Although a record high level of DA (2820 μg DA/g) was found in the digestive glands of scallops, the adductor muscle and gonad contained levels below or just over the regulatory limit of 20 μg DA/g [Reference James71]. It would therefore be a prudent and simple food safety measure to recommend the non-consumption of the digestive glands of these shellfish to reduce the risk of exposure of humans to ASP. DA has also been found in shellfish from New Zealand, Australia and Chile, but there have been no major toxic incidents involving humans. Further information regarding ASP and DA can be found in a recent review [Reference Pulido84].

Azaspiracid shellfish poisoning (AZP)

AZP is the most recently discovered toxic syndrome from shellfish consumption and several analogues belonging to this new class of toxins were identified in contaminated mussels [Reference Satake85–Reference Ofuji87]. The first confirmed event was in 1995 in The Netherlands and was caused by the consumption of mussels (M. edulis) that were cultivated in Killary Harbour in the west of Ireland. At least eight individuals were affected and the symptoms, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal cramps were similar to DSP. Azaspiracid (AZA1) was isolated from these mussels and the structure was later modified following the total synthesis of AZA1 (Fig. 3 e) [Reference Nicolaou88]. Several other AZP outbreaks occurred in the following years due to the consumption of mussels cultivated in Ireland (Table 1) [Reference James89]. Following the development of sensitive LC–MS methods for their determination [Reference Draisci90–Reference Lehane92], azaspiracids were identified in five other European countries, including the UK, Norway [Reference James93], France, Spain [Reference Braña Magdalena94] and Denmark [Reference De Schrijver47], as well as throughout the western coastline of Ireland [Reference Furey95]. Azaspiracids have also recently been found in North Africa [Reference Taleb96] and Japan [Reference Ueoka97]. More than 20 analogues of AZA1 have been identified in shellfish [Reference Ofuji86, Reference Ofuji87, Reference James98, Reference Rehmann, Hess and Quilliam99], which complicates the regulatory control of these toxins as most have not yet been toxicologically evaluated.

Toxicological studies have indicated that azaspiracids can induce widespread organ damage in mice and that they are probably more dangerous than previously known classes of shellfish toxins [Reference Ito100, Reference Ito101]. AZA1 is distinctly different from DSP toxins as its target organs include liver, spleen, the small intestine and it has also been shown to be carcinogenic. Using oral administration to mice, multiple organ damage was observed; (a) fatty change and single-cell necrosis in liver, (b) erosion epithelial cells of small intestinal villi and (c) lymphocyte necrosis in the thymus and spleen. In the most severe cases, inflammation and oedema in the lungs and stomach occurred. The chronic study showed tumour formation in lungs and malignant lymphomas. All mice used in these studies developed interstitial pneumonia and had shortened small intestinal villi, even at low doses (1 mg/kg) [Reference Ito100, Reference Ito101]. Cytotoxicity studies using neuroblastoma cells showed that AZA1 disrupts cytoskeletal structure, inducing a time- and dose-dependent decrease in F-actin pools. A link between F-actin changes and diarrhoeic activity has been suggested and this may explain the severe gastrointestinal disturbance in AZP outbreaks. Azaspiracids were found to induce a significant increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration in lymphocytes. Elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels can lead to cell death [Reference Román102–Reference Vilariño104].

Azaspiracids have been identified in two dinoflagellates, Protoperidinium crassipes [Reference James105] and a new species, Azadinium spinosum [Reference Tillmann106]. AZA2 has also recently been found in a sponge (Echinoclathria sp.) in Japan, representing the first report of this class of toxins in Asia [Reference Ueoka97]. Although confirmed reports of AZP have only been associated with mussel consumption, several other types of bivalve shellfish species have been found to accumulate these toxins, including oysters, clams and scallops [Reference Furey95]. The exclusive reliance on the DSP live animal bioassays, recommended by the EU, to monitor azaspiracids contamination of shellfish failed to prevent human intoxications [Reference James89]. This was a consequence of poor sensitivity of the assay and the incorrect assumption that azaspiracids were exclusively concentrated in the shellfish digestive glands that were used for testing [Reference James107]. Most regulatory agencies in Europe now comply with a strict regulatory control of azaspiracids in shellfish (<0·16 μg/g edible tissues) by frequent testing of shellfish using sensitive LC–MS/MS analytical methods, as outlined in recent reviews [Reference James and Pico4, Reference James, Botana and Hui108].

GLOBAL INCREASE IN HABs

There has been an apparent global increase in the occurrence of algal toxins in shellfish, with several new toxin classes identified in recent years. However, the reasons behind the apparent expansion in HABs and shellfish toxicity remain unclear with a number of factors being implicated including, climate change, anthropogenic activities, changes in shellfish cultivation, eutrophication, increased global marine traffic, improved toxin detection and better food control and toxin monitoring programmes [Reference Van Dolah15, 109–Reference Kelly112]. Projected increases in ocean temperatures are predicted to change global circulation that may lead to an increase of HABs. Moreover, the increased concentrations of greenhouse gases are expected to reduce pH, increase surface-water temperatures and affect vertical mixing and upwelling [Reference Moore113]. Phytoplankton growth is dependent on the availability of nitrogen. Atmospheric deposition of nitrogen, from agricultural and urban sources, can lead to increased algal blooms [Reference Smayda3, Reference Pearl and Whitall114]. Most marine HABs are comprised of dinoflagellates. The mobility characteristics of dinoflagellates allow them to swim under stratified layers of the water column to access nutrients in deeper layers. This may give dinoflagellates a competitive edge over other phytoplankton that cannot swim [Reference Moore113]. The potential consequences of these changes for HABs have received relatively little attention and are not well understood. Several studies have emphasized the relevance of coastal eutrophication to increased HABs and this is especially relevant to shellfish production and intoxication [Reference Maso and Garces110]. Increased coastal aquaculture activities can lead to local nutrient enrichment and eutrophication which not only increases the growth of toxic algae but also acts as the main vector for increased exposure of humans to toxins. A remarkable example of the positive effects of reducing nutrient loading was in Hong Kong harbour where the frequency of algal blooms declined after several years of nutrient reduction [Reference Hodgkiss and Ho115]. However, many algal blooms are not due to national anthropogenic activities and toxic algae can be transported from remote oceanic regions to affect coastal regions which have normally pristine waters. Thus, in Europe, the major shellfish toxicity from HABs occurs along the western Atlantic coastline, affecting Scotland, Norway, Ireland, France, Spain and Portugal, but the Mediterranean region which has a high nutrient loading, has a low incidence of such problems. It is therefore prudent to caution against a rush to judgement until there has been an extensive database of algal population flux over an extended period of years.

The emergence of non-indigenous toxic algal species in various geographical locations has been linked to an increase in global marine traffic. In particular, the release of ballast waters has been shown to be responsible for invasions of exotic species, including algae, bacteria and zooplankton. Algal cysts in ballast waters have been identified as the cause of new PSP events in regions of Australia that were previously unaffected and led to new ballast water guidelines to limit exposure to exotic species [Reference Hallegraeff8, Reference Hallegraeff and Graneli116]. Recent evidence of an increased global expansion of HABs includes the first reports of palytoxin and tedrodotoxin in European waters and the discovery of azaspiracids in Japan [Reference Ueoka97]. An outbreak of respiratory illness in people exposed to marine aerosols occurred in Genoa, Italy, in 2005 and a palytoxin analogue was identified as the probable causative agent [Reference Ciminiello117]. Ostreopsis spp. are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical areas, but recently these dinoflagellates have also started to appear in the Mediterranean where they produce palytoxins [Reference Louzao, Ares and Cagide118, Reference Cagide119].

Tetrodotoxin is a well known paralytic toxin that is found in pufferfish and causes fatalities in Japan almost annually [Reference Noguchi and Arakawa120]. Once again, a toxin that is usually found in tropical and sub-tropical waters appeared in a trumpet shellfish (Charonia sauliae), harvested from the Atlantic coastline of Portugal. An individual was hospitalized and suffered general paralysis, including the respiratory muscles, a few minutes after the consumption of several grams of this shellfish [Reference Fernández-Ortega121]. The investigation of the extent and implications of these new toxic problems in Europe is currently the subject of a collaborative EU project (ATLANTOX) [122].

CONCLUSIONS

The impact on human health from the consumption of biotoxins in shellfish has apparently increased in recent decades. There is evidence, although not conclusive, that the increase in HABs is a consequence of large-scale ecological changes from anthropogenic activities, especially increased eutrophication, marine transport and aquaculture. Global climate change has also been implicated. Recent improvements in toxin detection methods and increased toxin surveillance programmes are positive developments in limiting human exposure to shellfish toxins. However, there is a requirement for the development of clinical tests to improve the correct diagnosis of shellfish poisoning in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge funding from the Higher Education Authority of Ireland, as part of Ireland's EU Structural Funds Programmes (2007–2013) and the European Regional Development Fund; Programme for Research in Third Level Institutions (PRTLI-4), ‘Environment and Climate Change: Impacts and Responses’.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.