INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) in the prison setting poses a major public health problem globally, especially in countries of the former Soviet Union [Reference Aerts1] and in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [Reference Habeenzu2, Reference O'Grady3], where TB in prisons remains a neglected plague and a human rights issue [Reference Aerts1, Reference O'Grady3–Reference Aerts6]. Prisons are settings in which TB transmission occurs and high rates of active TB have been reported worldwide [Reference Aerts1–Reference Aerts6]. The situation in SSA makes TB a major public health problem due to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, overcrowding, insufficient ventilation, poor hygiene, low socioeconomic status, poor nutrition, prolonged duration in prison, and poor general health of inmates [Reference O'Grady3, Reference Braun7, Reference Snider and Hutton8]. Moreover, delayed diagnosis and inappropriate case management increases the problems associated with TB [Reference Coninx9]. Owing to incomplete, interrupted, inadequate treatment, or poor healthcare management, prisoners harbour drug-resistant TB [Reference Pleumpanupat10, Reference Ruddy11], which is increasingly being reported from SSA prisons [Reference Habeenzu2, Reference O'Grady3, Reference Noeske5] as well as from Eastern European prisons [Reference Aerts1, Reference Ruddy11–Reference Ignatova13]. Prison settings are important, but often neglected, reservoirs for drug-resistant TB transmission and pose a threat to individuals in the outside community [Reference Aerts1, Reference Habeenzu2, Reference Pleumpanupat10–Reference Ignatova13]. According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, the world's prisons hold 8–10 million prisoners each day, with 4–6 times this number passing through prison system each year. Studies in prevalence rates of TB in prison populations are among the highest documented in any population. While the bulk of studies have focused on the TB situation in prisons in Eastern Europe and the USA, data on the prevalence and incidence of TB in prisons in SSA countries are limited. Based on active screening studies from SSA prisons [Reference Habeenzu2, Reference Noeske5, 14–Reference Rutta20], TB prevalence rates were reported several fold higher than the national rates, indicating TB prevention and control in prisons is not well addressed nor integrated into most national TB programmes.

Given the high risk of TB in prison settings, there is an urgent need for policy makers, programme managers, and scientific communities to revise their efforts and implement effective control programmes to protect not only the health of people that are imprisoned but also the health of the wider community. Here we review and summarize the available literature on prevalence, drug resistance, and risk factors for acquiring TB in the prison population, as well as transmission and control of TB in prisons and discuss the importance of our findings for informing TB control policies in prison settings.

METHODS

A literature search was conducted for articles published between 1992 and 2014 from 1 January 2014 to 28 February 2014 using the online databases PubMed/Medline and Google scholar. To fined articles related to TB in prison settings, we considered one of the following key words such as: ‘Tuberculosis’ and ‘prisons’, ‘risk factors’, ‘drug resistance’, ‘prevalence rate’, and ‘control’. Each term was searched separately with the name of the regions and/or countries. Only English-language papers and WHO websites were included in the search and the searches were focused on studies of prevalence, drug resistance, and major risk factors associated with TB in prisons. Only study reports that used original research papers and case-control studies were reviewed. Literature that did not report on a study of TB in prisons was excluded. The three authors independently reviewed all of the studies found and WHO websites. A structured form for data extraction was used and included such points as country where the study was conducted, year of publication, TB prevalence rate in prison(s), total number of prisoners investigated for TB or TB in a comparison to the general population, risk factor for the prevalence, and drug-resistant TB in prison(s). We assessed and tallied the frequency of prevalence, drug resistance of TB and risk factors across all studies reported. In this review we report the risk factors and recommendations most commonly reported in the literature.

RESULTS

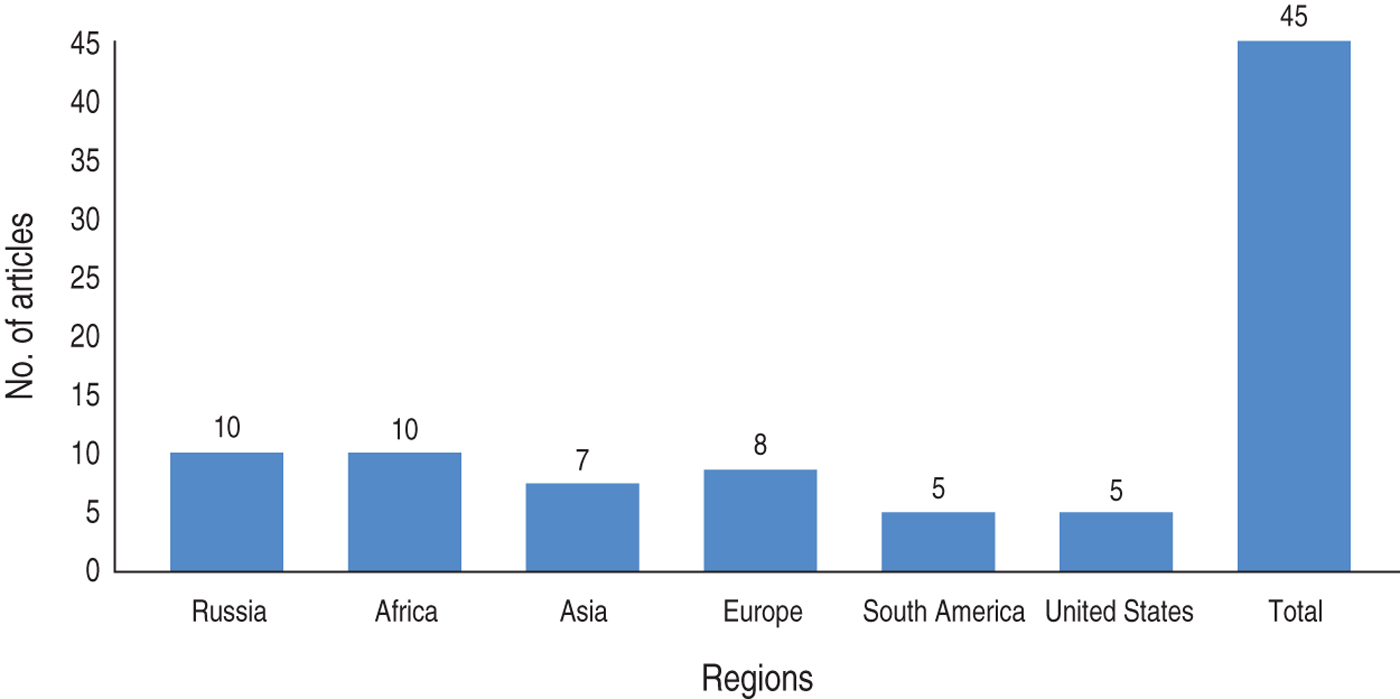

A research paper published between 1992 and 2014 shows the included studies were varied in terms of research methods and study site. As summarized in Figure 1, our electronic search resulted in 6474 citations. Finally, 127 articles were retrieved for full text review and 45 papers were determined to meet eligibility criteria and included in this review. Of the 45 relevant articles, 10 each were from Russia and Africa, seven from Asia, eight from Europe and five each from South America and the USA (Fig. 2). The prevalence of TB in prisons has been reported to be 3- to 1000-fold higher than that found in the civilian population (Table 1). In addition, high levels of multidrug-resistant (MDR)-TB at 54·8% and extensively drug-resistant (XDR)-TB at 11·1% have been reported from prison settings (Table 2). According to a WHO report in 2013, the notified XDR-TB cases among countries are shown in Figure 3. Multiple risk factors such as overcrowding, poor ventilation, malnutrition, HIV, and others have fuelled the spread of TB in prisons (Fig. 4). The most common recommendations by investigators to prevent and control the spread of TB in prison setting were active case-finding, followed by implementation of directly observed treatment, short course (DOTS)strategy and the need for improved mycobacteriological laboratory services (Table 3).

Fig. 1. Flow diagram showing literature review.

Fig. 2. Frequency of included articles for review by region.

Fig. 3. Notified extensively drug-resistant (XDR)-TB cases in countries, 2013 (Source: WHO Global tuberculosis report, 2013.)

Fig. 4. Risk factors that fuel TB infection in prisons and potential portals of exit for TB from prison to the community. (Sources: references [Reference Aerts1–Reference O'Grady3, Reference Noeske5, Reference Aerts6, Reference Abebe16–Reference Nyangulu18, Reference Rutta20, Reference Jittimanee23–Reference Sanchez25, Reference Lemos, Matos and Bittencourt37, Reference Banu47, Reference Narasimhan56–Reference Lobacheva, Asikainen and Giesecke62].)

Table 1. A summary of prevalence studies reporting TB in prisons

n, Number of cases; N, total number of cases; n.a., not available.

* All values are given as reported in the cited studies.

† Fold higher.

Table 2. Studies reporting drug-resistant TB in prisons

EMB, Ethambutol; INH, isoniazid; KAN, kanamycin; MDR, multidrug resistant; PZA, pyrazinamide; RMP, rifampicin; SM, streptomycin.

* The value of drug resistance and MDR-TB is reported in the cited studies.

Table 3. A summary of recommended TB control measures in prison setting

DOTS, Directly observed treatment, short course.

DISCUSSION

Evidence of prevalence of TB in prisons

In this review, we observed that, globally, the level of TB in prisons has been reported much higher than that of TB in the general population [Reference Aerts1, Reference Habeenzu2, Reference Noeske5, 14–Reference Rao29]. The WHO estimated a prevalence of TB in prisons about 10- to 100-fold higher than the prevalence in the general population [30]. According to our review of published studies, this ranged from 3·75- to 1000-fold higher than in the general population, both in high- and low-income countries (Table 1). In the studies from Russian prisons, the prevalence of TB was 5995/100 000 in Georgian (448 cases from 7473 prisoners) prison inmates, almost 200 times more than the prevalence rate of TB in the general population [Reference Aerts1]. The observation was confirmed for other Russian prison populations by study results from Slavukij et al. in 2002 [Reference Slavuckij31] and Lobacheva et al. in 2005 [Reference Lobacheva32]. According to studies in prisons from the WHO European region, the median TB detection rate was 393/100 000 inmates, which is 83·6 times more TB than in the general population [Reference Aerts6]. Based on this report, TB incidence rates in prisons of the surveyed countries were 8–35 times higher than in the general population. A study conducted in France showed a high prevalence rate of TB at 215/100 000 prisoners [Reference Hanau-Berçot33] and in Turkey the rate was 341/100 000 prisoners [Reference Kiter34]. Reports in other prison settings confirmed the overall trend [Reference Hutton, Cauthen and Bloch35–Reference Hernández-León43]. In the USA the rate was 3–11 times higher than in the general population and in Brazil it was 2065/100 000 and 2500/100 000 inmates, which is 70- and 42-fold higher than in the general population. Studies conducted in prisons in some Asian countries confirmed TB prevalence rates several times higher than in the general population [Reference Rao29, Reference Chiang44–Reference Banu47]. In Pakistan, Taiwan, Thailand, and Bangladesh the rate was 79/4870, 258·7/100000, 304/4751, and 2227/100 000, respectively, which is 3·75, 4, 8, and 20 times higher than in the general population, respectively. A TB surveillance study in correctional institutions over the period from 1999 to 2005 in Hong Kong found a very high TB prevalence rate in prisoners.

TB in African prisons poses a particularly challenging public health, economic, and social problem mainly in SSA, which also has a high prevalence of HIV infection [30]. In SSA, where poverty, HIV/AIDS, and chronic malnutrition are prevalent, the prison population probably has a high burden of TB [Reference O'Grady3, 30]. TB in prisons in SSA lacks the attention of both programme managers and scientific communities. It is one of the challenge areas in national TB prevention and control strategies. TB in prisons is prevalent, but data are scarce due to the lack of an active monitoring programme in SSA. This review yielded alarming information for understanding the disease burden as well as to motivate planning and implementing TB control and prevention measures in prisons. To our knowledge, there are ten published datasets that describe TB in prisons in SSA. These data reported high prevalence and incidence rates of TB compared to the general population [Reference Habeenzu2, Reference Noeske5, 14–Reference Rutta20, Reference Rasolofo-Razanamparany28]. For instance, in an active case-finding survey in Madagascar [Reference Rasolofo-Razanamparany28], the prevalence of TB in Antananarivo prison was 16 times higher and Zambian prisons [Reference Habeenzu2] had about 10-fold higher incidence than in the general population. A cross-sectional, cell-to-cell survey in 18 prisons in Malawi reported that 47 (5142/100 000) inmates had pulmonary TB [Reference Nyangulu18]. In 2009, Banda et al. [Reference Banda19] reported a period prevalence of 0·7% (54/7661). Cross-sectional studies from the Ivory Coast [Reference Koffi15], Tanzania [Reference Rutta20], Botswana [14], and Cameroon [Reference Noeske5], all confirm high TB prevalence rates in prisons compared to the civilian population.

In Ethiopia, TB in prisons is not well documented despite the presence of multiple physical, individual, and social factors that favour TB epidemics. The observed point prevalence in eastern Ethiopian prisons was 1913/100 000 inmates [95% confidence interval (CI) 1410–2580], seven times higher than that of the general population [Reference Abebe16] and in 2012 Moges et al. [Reference Moges17] reported a point prevalence of TB at 1482·3/100 000 in the prison population, which was 9·1 times higher than in the general population. These data suggest that inadequate TB control measures in prison settings have a considerable impact on communities inside and outside prisons in Ethiopia and with comparable situations in other SSA countries; it is arguably conceivable to be the case in SSA, generally. A review of all relevant English publications on TB in prisons in SSA performed by O'Grady et al. [Reference O'Grady3] in 2011 also suggested that there is evidence of an increasing prevalence of active TB in prisons in SSA with drug-resistant TB increasingly being detected. The survey of studies on TB prevalence and incidence rates shows disturbingly that TB in prisons is increasing and will threaten national TB programmes due to delayed case detection, incomplete treatment of TB, and release and recidivism without screening [Reference Abebe16].

Drug-resistant TB in prison

The WHO's 2010 Global MDR-TB report estimated that there were 440 000 MDR-TB cases (3·6%, 95% CI 3·0–4·4) and 150 000 deaths were due to MDR-TB worldwide in 2008 [48]. China and India accounted for 50% of MDR-TB worldwide. According to a WHO/International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (IUATLD) survey of 20 countries with the highest rates of MDR-TB in previously treated cases, 14 are in the European Region [49]. In Africa 69 000 MDR-TB cases were reported in 2008 [48]. Published studies on prevalence and incidence rates are increasingly available, but accurate data on drug-resistant TB in prisons is limited.

In prisons, high levels of MDR-TB and XDR-TB have been reported (Table 2). Prisons pool and serve the spread of drug resistance and MDR-TB [Reference Ruddy11], which is increasingly being reported worldwide [Reference Aerts1–Reference O'Grady3, Reference Aerts6, Reference Braun7, Reference Coninx9, Reference Ruddy11, Reference Toungoussova12, 14, 30, Reference Abrahão, Nogueira and Malucelli36, Reference Banu47, 48, Reference Kimerling50–Reference Anderson55]. A TB surveillance study in WHO European Region prisons in 2001 showed high levels of MDR-TB: 50% in Estonia, 18% in Azerbaijan, 14·0% in Latvia, and 0·6% in Spain [Reference Aerts6]. Other studies showed high levels of MDR-TB from prisons with up to 24% of all TB patients [30]. In a Russian prison 11·1% XDR-TB was reported [Reference Balabanova52]. Data on countries reporting at least one XDR-TB is presented in Figure 3. Re-imprisonment, poor healthcare, inadequate treatment, pressure on prisoners to self-treat, access to uncontrolled anti-TB drugs through the prison black market, staff and visitors, release and recidivism without screening, and failure to complete treatment were identified as prison factors contributing to the development of MDR-TB [30, Reference Banu47]. Obviously, MDR-TB is more difficult to treat than normal TB and consumes more resources. Preferably, all suspected TB cases should undergo drug susceptibility testing; however, the efficacy of this policy depends on local feasibility and skilled staff. At least, prison inmates must have access to the same facilities and healthcare services as the general population. Poor health service management, inadequate health professionals for prisons, poverty, lack of continuous monitoring and evaluation, inadequate discharge planning, contact tracing and follow-up after discharge, and general low attention given to prisoners are barriers to the implementation of TB control in prisons [Reference O'Grady3].

Effect of risk factors on TB infection and disease

Several potential environmental, social, and host-related risk factors that promote transmission and development of active TB in prisons were investigated in this review (Fig. 4). In prisons the most identified risk factors are HIV infection, poor ventilation, cough, overcrowding, malnutrition, stress and anxiety, poor prison health services, smoking, alcohol, addictive drugs, lack of sunshine and vitamin D deficiency, longer duration of stay in prison, young age, and urban residence [Reference Aerts1, Reference O'Grady3, Reference Noeske5, Reference Aerts6, Reference Abebe16, Reference Moges17, Reference Rutta20, Reference Banu47, Reference Narasimhan56–Reference Winetsky60]. Studies have shown that malnutrition and/or a body mass index (BMI) <18·5 kg/m2 were associated with increased risk of developing TB in prisons [Reference Moges17, Reference Rutta20, Reference Banu47, Reference Winetsky60]. For instance, a study in Zambia found that nutritional status and food intake was universally poor in all surveyed prisons. Similarly, studies in the Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Cameroon, and Russia reported a BMI < 18·5 kg/m2 as a significant predictor of TB.

HIV infection has emerged as the most important risk factor for development of TB in persons infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis [Reference O'Grady3, Reference Noeske5, Reference Moges17, Reference Narasimhan56–Reference Smith and Bloom58, Reference Winetsky60]. For example, those with HIV co-infection have an increased risk of reactivation of TB at 10% during each year of infection [Reference Noeske59]. There is evidence that TB infection in HIV-infected patients progresses to TB more rapidly than in those without HIV infection [Reference Narasimhan56–Reference Noeske59]. Being an urban resident, an inmate with a cough lasting >4 weeks, or sharing a cell with a confirmed TB case increased the risk of TB by nearly 4-, 3-, and 3·4-fold, respectively [Reference Abebe16]. In 2009 Lemos et al. [Reference Lemos, Matos and Bittencourt37] found cough as a determinant risk factor for active TB [prevalence rate (PR) 8·8, 95% CI 1·04–73·9, P = 0·025].

In addition to several risk factors, people with low socioeconomic status have a higher likelihood of being exposed to crowded and less ventilated places [Reference Narasimhan56]. Crowded living conditions increase transmission of tubercle bacilli, resulting in a higher prevalence of TB infection with subsequent increased incidence of disease [Reference Rieder61]. Consequent to low socioeconomic status, individuals may have poor access to healthcare that could increase the risk and prolong the period of infectiousness.

A case-control study in Russia reported that an overcrowded cell (more than two people per bed) and spending less time outdoors were independent risk factors for developing TB in the prison [Reference Lobacheva, Asikainen and Giesecke62]. The Georgian study also indicated that risk was also three times higher in inmates of a large size prison facility. Large prisons are notorious for having poor hygienic standards and lacking adequate ventilation [Reference Aerts1]. The length of imprisonment is one of the commonly identified risk factors for TB. The Georgian study showed that the risk of acquiring TB for those imprisoned ⩾2 years was twofold greater than for those who were imprisoned for <1 year [Reference Aerts1]. The longer prison stay may contribute to infection through lengthier exposure in addition to deterioration of immunological function as a result of poor living conditions and physical and emotional stress [Reference O'Grady3, Reference Rieder61]. On the other hand, the length of stay was not a significant risk factor for TB in a study of Zambian prisons [Reference Habeenzu2]. A history of previously being in a prison [Reference Noeske5, Reference Martin27, Reference Coker63, Reference MacNeil64] was found to increase the risk of TB. Overall, the studies explicitly stated that the prison-related factors contribute to a high TB burden both inside as well as outside of prisons and thus need to be addressed in TB control strategies.

Age and sex differences in the prevalence of TB infection and disease have been reported worldwide [Reference Habeenzu2, Reference Moges17, Reference Nyangulu18, Reference Rutta20, Reference Jittimanee23, Reference MacNeil, Lobato and Moore24, Reference Narasimhan56, Reference Winetsky60]. Children are at higher risk of contracting TB infection and disease [Reference Narasimhan56]. Studies have shown that prisoners aged 15–44 years had a higher risk compared to other age groups of acquiring TB and developing the disease [Reference Abebe16]. However, Winetsky et al. [Reference Winetsky60] reported in 2014 that old age >50 years (PR 5·79, 95% CI 3·07–10·91) increased the risk of acquiring TB in prison. Prison studies indicate a significant difference between male and female prisoners [Reference Habeenzu2, Reference Nyangulu18, Reference Jittimanee23, Reference MacNeil, Lobato and Moore24]. High incidence rates in male prisoners were reported in Zambia and Malawi [Reference Habeenzu2, Reference Nyangulu18]. Moreover, in 2005 Sanchez et al. reported high incidence rates of TB in female prisoners [Reference Sanchez25]. The epidemiological difference could be due to poorer access to healthcare facilities, higher exposure to infection, and increased susceptibility rather than biological difference [Reference Rieder61].

Risk of infection and progression to TB

The development of TB disease requires a two-stage process in which a susceptible person exposed to an infectious TB case first becomes infected and may later develop the disease, depending on various factors influencing the risk of exposure, the risk of infection, the risk of developing disease, and the risk of death [Reference Lienhardt65]. The first step is to have contact with an infectious TB patient, who expectorates bacilli in the surrounding environment. The probability of contact between a susceptible person and a source case depends on the prevalence of active pulmonary TB in a given population (in this case, the prison setting) and is influenced by several factors, the most important being crowding and poor ventilation [Reference Lienhardt65]. Droplet nuclei are produced and spread when patients with pulmonary or laryngeal TB cough, sneeze, speak, or sing. Of persons exposed to an infectious TB case, the risk of becoming infected is due to the joint effect of three factors: (1) the infectivity of the source case, (2) the frequency of exposure to the source case, and (3) susceptibility of the person to infection [Reference Lienhardt65]. The probability of infectivity of the case to tubercle bacilli depends on the frequency of coughing, the number of bacilli in the sputum [Reference Shaw and Wynn-Williams66], and the microbial ‘virulence’ [Reference North and Izzo67]. In patients with TB of the respiratory tract not all are equally efficient in transmitting. Patients whose sputum smears are positive for acid-fast bacilli have ⩾5000 organisms/ml of sputum [Reference Yeager68] and infect many of their close contacts. The close contact between a susceptible person and the infector determines the degree of exposure [Reference Lienhardt65]. In 2003, Beggs et al. identified small room volume, high resident density, and poor ventilation rate as crucial factors for TB transmission in confined spaces [Reference Beggs69]. The degree of vulnerability of the case is a function of health status of the person and genetic factors [Reference Di70, Reference Newport71]. In 2003 Tufariello and colleagues [Reference Tufariello, Chan and Flynn72] stated that progress of TB from infection to the disease involves the tubercle bacilli overcoming the immune system's defences, and in primary TB, which constitutes around 10% of all cases, the progression of the infection to TB disease occurs soon after infection. In many individuals, the disease may remain dormant within the body with the immune system capable of containing the infection (latent TB) [Reference Tufariello, Chan and Flynn72]. When the immune system weakens due to host-related factors, the infection is reactivated. The risk of this reactivation rises when immunity is suppressed [Reference Narasimhan56, Reference Tufariello, Chan and Flynn72]. Any factor influencing the risk of infection and/or the risk of breakdown after infection affects the incidence of TB disease in a given population [Reference Noeske59]. Environmental factors such as overcrowding, poor ventilation, urban residence, or low socioeconomic status affect the risk of infection [Reference Comstock73]. These factors may have an impact on the incidence of TB in a given population as the result of their effect on both the risk of infection and the risk of disease once a person is infected [Reference Lienhardt65].

Transmission of TB inside and outside prison cells

Prisoners usually come from communities with higher TB prevalence rates and bring with them an unhealthy lifestyle [Reference Reyes74]. Because of ignorance, neglect, or lack of means for screening, infected prisoners may enter prisons [Reference O'Grady3]. Prisons concentrate individuals usually in overcrowded and unhygienic environments and limit access to healthcare services [Reference Reyes74]. Overcrowded prisons facilitate the spread of TB, because prisoners are in close contact with others without access to outside spaces. Living together in cramped quarters with no ventilation is another major factor for contracting TB [Reference Reyes74]. Another aspect facilitating TB communication is that prisoners are often highly mobile within the system; inside the prison, between different prisons and institutions of the judiciary system, as well as healthcare institutions. Prison staff and visitors come and go as well. This pattern clearly indicates TB in prisons is not only of concern for prisoners, but also for the wider community [Reference Greifinger, Heywood and Glaser75]. In 2010 Baussano et al. [Reference Baussano76] reported the fraction of TB in the general population attributable to transmission from prisons to be 8·5% in high-income countries and 6·3% in middle- or low-income countries. The prison setting is therefore becoming the place for concentrating, disseminating, and worsening TB, including MDR-TB, and even for exporting it into the general population. The question at present is what to do about what was until very recently ‘a forgotten and neglected disease’ [Reference Coninx77].

Prevention and control of TB in prison

A simple model of TB infection control measures in prison is given in Figure 5. The model encompasses several infection prevention and control measures as indicated by the numbers next to the arrows [Reference Dara78]. The numbers by the arrows indicate the following practical TB prevention and control measures that could be implemented to inhibit the TB transmission chain in prisons and the community: (1) prisoners are screened for active and latent TB infection upon entry and during incarceration and isolation, rooms (for occupation for up to 2–4 weeks) should be provided for suspected prisoners; (2) conducting contact case-finding, TB screening for transferred prisoners, and health education; (3) examining prisoners before release and prison staff regularly; (4) providing early TB case detection and successful treatment. Furthermore, special emphasis should be given to establish and improve laboratory facilities for prompt and efficient diagnosis and treatment for control of TB in prison settings [Reference Aerts1, Reference Rueda39, Reference Chiang44, Reference Vinkeles79]. A DOTS strategy for patients with TB was recommended by the WHO [80]. The WHO Stop TB strategy applies to the general population and to TB control in prisons. The WHO/EURO prison health project implemented in 1995 is one of the initiatives addressing and integrating the Stop TB strategy in prison settings [Reference Aerts6]. However, these components are rarely implemented in developing countries. Unlike other African countries, Malawi has published guidelines on the implementation of specific interventions for TB in prisons [Reference Harries81]. The national TB programme (NTP) and the prison health services have effectively worked together to improve TB infection control [Reference Harries81]. Successes in TB infection control measures from programmes in Malawi were reported in comparison with other African countries [Reference Banda19].

Fig. 5. A simplified model of TB infection control methods in prisons [Reference Dara78]. (1, Screening for active and latent TB infection upon entry and during incarceration; 2, conducting contact case-finding, TB screening, and health education; 3, inspecting prisoners before release and prison staff regularly; 4, providing early TB case detection and successful treatment.)

The recommendations by investigators to prevent and control the spread of TB in the prison setting are presented in this review. Thus, according to the investigators, active case-finding and TB screening, adequate case-finding and containment strategies, implementation of DOTS strategy in prison, integration of a national TB control strategy with that of prison health services, entry examination for active and latent TB infection screening, intervention measures targeting inmates, the need for improved mycobacteriological laboratory services, and the need for improved screening and isolation of prisoners with TB were the reported recommendations to tackle TB in prisons [Reference Aerts1, Reference Habeenzu2, Reference Aerts6, 14–Reference Moges17, Reference Yerokhin, Punga and Rybka21, Reference Rao29, Reference Öngen38–Reference March40, Reference Chiang44, Reference Sretrirutchai45, Reference Banu47]. According to our review the most common recommendations by investigators to control TB in the prison setting were active case-finding followed by implementation of DOTS strategy and the need for improved mycobacteriological laboratory services. These control measures published in different journals provide much needed evidence for responsible agencies to renovate their effort to prevent the spread of TB in prison. In addition, each recommendation including the WHO guideline are available on how best to control and prevent TB in prisons [30].

Role of research in TB infection control

We are confident that research will play a vital role in the fight against TB. Promoting research is a key component of the Stop TB strategy [80], which includes programme-based operational research and research on introducing new tools into practice. There are questions that remain unanswered about TB in African prisons, mainly in SSA regions, suggesting an urgent need for research in addition to the efforts currently being made to improve programmes. The neglected issue of TB in prisons requires attention from scientific communities and political leaders. Political support and appropriate financing of research work is critical for TB infection control, since politicians have a responsibility to protect prisoners from harm from the disease [Reference O'Grady3]. Priority research questions should be identified and developed to assess new interventions and to improve TB infection control performance in prisons. This will provide an evidence base that can help governments allocate appropriate and adequate funding for TB infection control in prisons.

CONCLUSION

The incidence of TB in prisons was found to be several fold higher compared to the general population, indicating evidence for public health policy formulation. In addition, our review revealed that MDR and XDR-TB is widespread in prisons. Multiple factors such as overcrowding, poor ventilation, malnutrition, HIV, and others increases the transmission of TB within prisons. It is suggested that political leaders and scientific communities should work together and give special attention to the control of TB and MDR-TB in prisons. If not, TB in prisons will remain a neglected global problem and threaten national and international TB control programmes. Further research is required on the prevalence and drug resistance of smear-negative TB in prisons. In addition, evidence of the circulating strains and transmission dynamics inside the prison setting is also warranted.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF 1315883), the Institute of Medical Microbiology and Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases, Clinical Immunology, University Hospital Leipzig, Germany, Translational Centre for Regenerative Medicine (TRM)-Leipzig, University of Leipzig, Germany, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), and University of Bahir Dar, Ethiopia for supporting and funding the research.