The Bartonella genus includes fastidious Haemotropic Gram-negative bacteria transmitted by arthropod vectors [Reference Chomel1]. In Chile, Bartonella henselae, B. clarridgeiae and B. koehlerae DNA were previously detected in cats [Reference Müller2]; B. rochalimae in Pulex irritans from dogs and B. henselae and B. clarridgeiae in Ctenocephalides felis from cats [Reference Pérez-Martínez3]. No data concerning Bartonella spp. blood stream infection in dogs have been previously reported in the country so far. This study aimed to perform a molecular survey of Bartonella in dogs from Chile.

The study was approved by the Universidad Austral de Chile Bioethics Committee (250/2016). Blood samples were collected from 139 client-owned dogs from rural localities (Chaihuín (39°56′15″S, 73°35′19″W), Cadillal Alto (39°59′18″S, 73°31′11″W), Huiro (39°54′51″S, 73°30′55″W) and Huape (39◦54′51″ S, 73◦30′55″ W)) in the Valdivia Province, Southern Chile, including most of the dogs located in each of the communities. DNA extraction was performed (DNeasy® Blood & Tissue Kit; QIAGEN®, Valencia, CA, USA) and DNA concentration and purity were determined (NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer; Thermo Scientific©, Waltham, MA, USA). The RPS19 was used as an endogenous gene [Reference Brinkhof4]. Samples were screened by nuoG real-time PCR (qPCR) for Bartonella spp. [Reference Andre5] (CFX96 Thermal Cycler; BioRad©, Hercules, CA, USA). nuoG qPCR-positive samples were subsequently tested using conventional PCR assays based on ftsZ [Reference Paziewska6], gltA [Reference Norman7], rpoB [Reference Paziewska6] and nuoG [Reference Andre5] genes (T100 BioRad termocycler; BioRad©). cPCR-positive samples were sequenced (Sanger method; ABIPrism310 genetic analyser; Applied Biosystems©/Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA, USA) for speciation and phylogenetic analysis. Phylogenetic inference based on maximum likelihood criterion (ML) was inferred with RAxML-HPC BlackBox 7.6.3 (CIPRES Science Gateway).

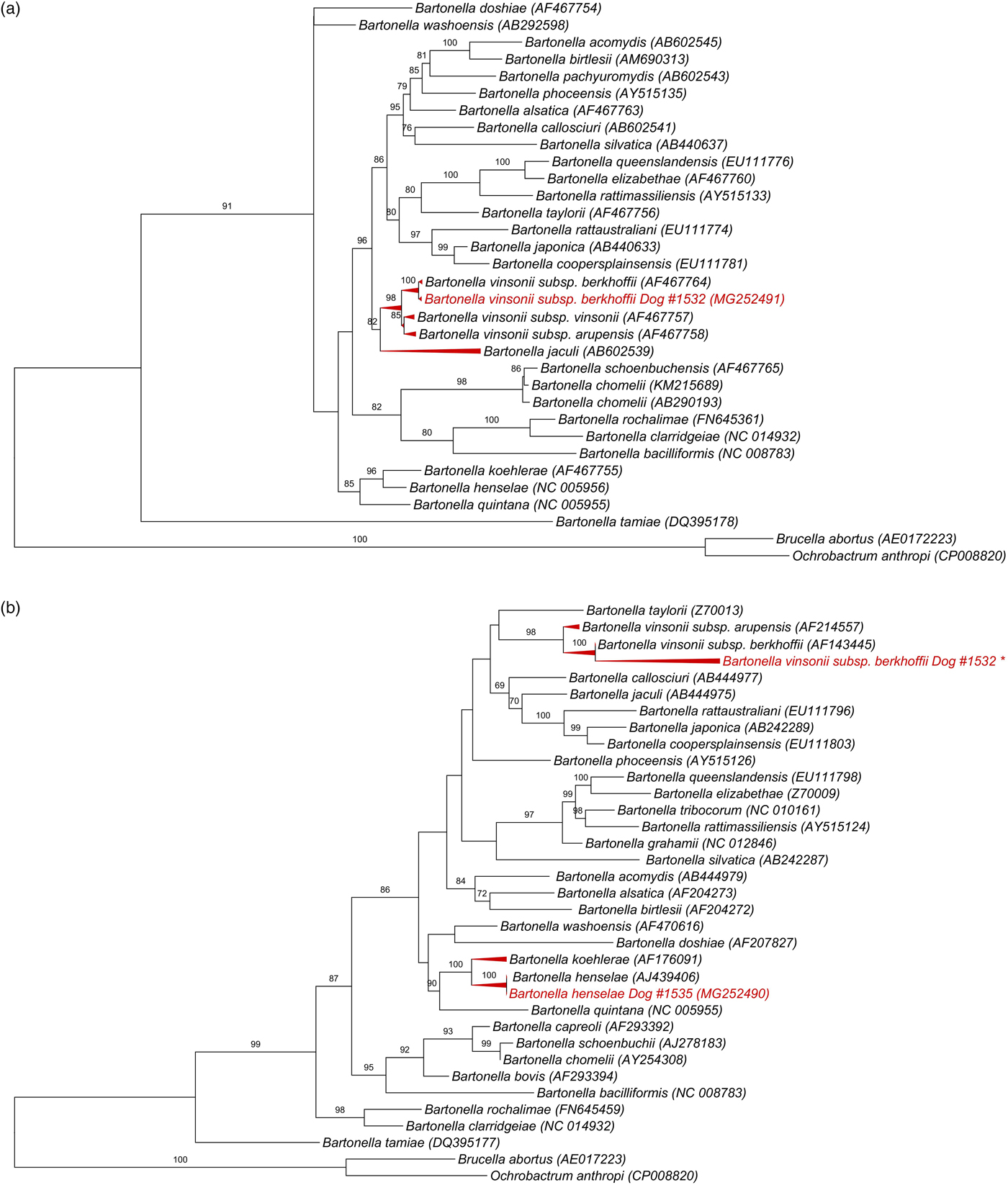

All 139 DNA samples (mean and standard deviation (s.d.) of DNA concentration = 33 ± 22.3 ng/μl; mean and s.d. 260/280 ratio = 1.8 ± 0.07) were positive for the RPS19 gene. Bartonella-nuoG DNA (mean and s.d. efficiency: 96·2 ± 0·81%, r 2 = 0·998 ± 0·00046) was detected in 4.3% (6/139) of the tested dogs. Out of six nuoG qPCR-positive samples, six, three, two and none showed results consistent with Bartonella spp. in cPCR assays based on gltA, ftsZ, rpoB and nuoG genes, respectively. Consistent sequencing results were obtained only for the ftsZ gene (550 bp) from sample #1532 (GeneBank accession number: MG252491), and gltA gene (305 bp) from sample #1535 (MG252490) and from sample #1532 (148 bp fragment that was not deposited in GenBank). While Blastn analysis of ftsZ fragment showed 99% identity with B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii (CP003124.1, AF467764.1), gltA fragment shared 100% identity to B. henselae (HG969191.1; AJ439406). It was not possible to identify species in the other cPCR-positive samples due to low signal strength in the electropherogram. While B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii sequence (MG252491) from sample #1532 clustered with an American Type Culture Collection B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii, B. henselae sequence obtained from sample #1535 (MG252490) grouped with a human B. henselae Houston-1 isolate (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic relationships within the Bartonella genus based on: (a) 950 pb fragment of the ftsZ gene after alignment including B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii from dog #1532 (GeneBank accession number: MG252491), (b) 1320 pb fragment of the gltA gene after alignment, including B. henselae gltA gene (305 bp) from sample #1535 (MG252490) and *B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii from #1532 (148 bp fragment that was not deposited in GenBank due to low length). The tree was inferred by using the ML method and evolutive model GTR + G + I. The numbers at the nodes correspond to the bootstrap values higher than 50% obtained with 1000 replicates. Brucella abortus and Ochrobactrum anthropi were used as out groups.

Few reports in South America have evaluated the molecular occurrence of Bartonella spp. in dogs. For instance, B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii was molecularly detected only in a dog from Colombia [Reference Brenner8] and in a dog from Brazil, co-infected with B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and B. henselae [Reference Vissotto De Paiva Diniz9]. To the best of our knowledge, B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and B. henselae are detected for the first time in dogs from Chile. Serologic surveys of B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii have been performed in North America, Europe, Asia and Africa, with an exposure that ranged from 3% to 65% [Reference Chomel1]. Nevertheless, as observed in the present study, B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii DNA is rarely detected by PCR from domestic dogs because dogs tend to maintain a very low level of bacteraemia, which makes molecular confirmation of blood stream infection challenging [Reference Duncan, Ricardo and Breitschwerdt10]. Differences between qPCR and cPCR results in this study were in accordance with other authors [Reference Gonçalves11, Reference André12], with a higher sensibility of qPCR compared with cPCR assays, highlighting the use of multiple approaches in order to increase the sensitivity of Bartonella detection. Better performance of qPCR over cPCR in detecting low Bartonella DNA copy numbers was described before [Reference André12]. Evidence suggests that dogs from regions with cold average winter temperatures, as the observed in southern Chile, are less likely to be PCR-positive than dogs from other climatic zones [Reference Chomel1]. Attempts to improve the detection of this Bartonella species from dog blood samples using pre-enrichment media should be addressed in the future [Reference Duncan, Ricardo and Breitschwerdt10], as the techniques used in this study may have resulted in a lower molecular prevalence than actually exists in the dogs from Chile. Although cats are known to play a major role as B. henselae reservoirs in Chile [Reference Ferrés13], our results suggest that this species is also circulating in domestic dogs from the country. As observed before in Brazil [Reference Vissotto De Paiva Diniz9] and Colombia [Reference Brenner8], and described in Africa and Asia [Reference Chomel1], rural and stray dogs, such as the dogs from Valdivia Province, are more likely to be infected or seroreactive to Bartonella spp.

Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii is an emerging bacteria that has been isolated from immunocompetent human patients with arthritis, endocarditis, neurological disease and vasoproliferative neoplasia [Reference Breitschwerdt14]. Vector transmission is suspected among dogs, which are the primary reservoir hosts. Unlike the domestic cat, for which clinical manifestations of natural infection are rarely documented, a wide range of clinical abnormalities have been reported in B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and B. henselae bacteraemic dogs [Reference Chomel1].

Since Bartonella spp. infected dogs develop pathology that is very similar to their human counterparts, natural and experimental infection in dogs could provide important information to enhance knowledge of the disease in people [Reference Breitschwerdt15]. In Chile, B. henselae has been implicated in more than 200 human cases of bartonellosis serologically diagnosed between 1997 and 2000 [Reference André12]. The presence of B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii suggests the need to consider this species when testing clinical samples from suspected human cases in Chile. High similarity detected between B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and B. henselae from dogs and human isolates highlights the importance of the canine population as a potential source of zoonotic agents and infection risk to humans in the country.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the veterinary team of the UACh Veterinary Hospital for their helpful contributions in collecting samples. They also wish to thank the team of the Inmunoparasitology Laboratory, Faculdade de Ciências Agárias e Veterinárias of the Universidade Estadual Paulista, Jaboticabal, Brazil, for their technical support.

Conflict of interest

None.