Introduction

Proponents of sustainable development suggest that economic growth should be designed to meet the needs of the present generation without jeopardizing the rights of generations to come (Brundtland Reference Brundtland1987). Sustainable production and supply chains should thus find an optimal long-term balance between economic, social and environmental issues (Fay Reference Fay2012, Borel‐Saladin & Turok Reference Borel‐Saladin and Turok2013).

Despite the omnipresent discourse that sustainable growth should be pursued, production of agricultural commodities to supply the needs of the world’s growing population is increasing hastily and is responsible for driving c. 80% of global deforestation (Hosonuma et al. Reference Hosonuma, Herold, De Sy, De Fries, Brockhaus and Verchot2012). These include ‘forest risk commodities’ such as beef and leather, cocoa, palm oil, rubber, soya, pulp and paper (Newton et al. Reference Newton, Agrawal and Wollenberg2013, Rautner et al. Reference Rautner, Leggett and Davis2013, Lawrence & Vandecar Reference Lawrence and Vandecar2015). In response, businesses, scholars and governments have turned their attention to supporting sustainability in commodity supply chains (Brickell & Elias Reference Brickell and Elias2013, Green Reference Green2015). A ‘zero-deforestation movement’ has emerged based on the notion that more radical efforts had to be made to delink commodity production from deforestation (Lambin et al. Reference Lambin, Gibbs, Heilmayr, Carlson, Fleck, Garrett and de Waroux2018).

Consumer goods manufacturers, traders and corporate processing groups have pledged to eliminate deforestation from their supply chains, although they use different definitions of forests and compliance timeframes (Hower Reference Hower2014, United Nations 2014). In 2017, 12 of the world’s leading cocoa and chocolate companies collectively committed to end deforestation and forest degradation in the global cocoa supply chain, with an initial focus on Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana (World Cocoa Foundation 2017).

It is, however, not yet clear what factors these zero-deforestation commitments should take into account in order to effectively ensure that social, environmental and economic issues are addressed according to the principles of sustainable development. Moreover, the challenge is to ensure that these pledges are not reduced to simply conserving remnant forest plots adjacent to agricultural production areas, but that they contribute towards enhancing the sustainability of the landscapes where the raw materials are sourced, as well as the supply chains from farmer to consumer. The latter will entail actions aimed at ensuring forest protection, and thus securing the provision of ecosystem services, but also on stimulating the uptake of improved production practices that should result in improved cocoa famer income and well-being.

So far, the literature on zero-deforestation commitments has focused mostly on the challenges and risks associated with implementing these on the ground, with a heavy focus on deforestation, but with less attention given to the actions at different stages along the supply chain that are needed to address the environmental issues found upstream in the chain (primary production stage). This is problematic for three main reasons: (1) drivers of unsustainable commodity production are sometimes found elsewhere in the end-product supply chain, such as the lack of demand for certified sustainable products in consuming countries; (2) deforestation and its associated carbon emissions and biodiversity loss represent only some of the many environmental externalities related to the production of end products (e.g., chocolate); and (3) the livelihoods of smallholder farmers, who are the main cocoa suppliers, constitute a major challenge that needs to be addressed concomitantly with environmental concerns (Kopnina Reference Kopnina2017). Therefore, a limited focus on the commodity and deforestation at the farm level might not help address the problem in the long term.

Cocoa is a very important cash crop for millions of farmers and the national economies of several countries in West Africa, as well as in Brazil and Indonesia (FAO 2014). Notwithstanding the benefits that cocoa brings, it has been directly linked to deforestation and forest degradation in production areas (Gockowski & Sonwa Reference Gockowski and Sonwa2011). Although cocoa production has a lower contribution to deforestation compared to other commodities such as beef and soy (Henders et al. Reference Henders, Persson and Kastner2015), research suggests that over the last 50 years, cocoa cultivation has contributed to the disappearance of 14–15 million ha of tropical forests globally (Clough et al. Reference Clough, Faust and Tscharntke2009). Moreover, production continues to expand to meet the growing international demand, further increasing pressure on forest areas. Yet it is still important to address the impacts of cocoa on forest conversion since it has been leading to local and regional climatic changes (Laderach et al. Reference Laderach, Martínez-Valle, Schroth and Castro2013) that will likely impact not only cocoa production, but also the livelihoods of millions of cocoa producers and their dependants living in the cocoa belt (Schroth et al. Reference Schroth, Läderach, Martinez-Valle, Bunn and Jassogne2016, Coulibaly et al. Reference Coulibaly, Terence, Erbao and Bin2017).

Cocoa production is only one part of the chain, with several other sectors still needing to interact before chocolate – the final product – can be produced, including other basic ingredients (sugar, lecithin, vanilla, milk powder, nuts, etc.), the agricultural inputs industry (e.g., seedlings, fertilizers), local buyers (traders), processors, manufacturers, transporters, the packaging industry, retailers and final consumers (Afoakwa Reference Afoakwa2014; Camargo & Nhamtumbo Reference Camargo and Nhamtumbo2016) (Supplementary Material S1, available online).

In this study, findings from a thematic analysis of perceptions from different types of stakeholders connected to the production of cocoa and chocolate – in both producing and consuming countries – are systematically characterized in terms of what they believe are the main challenges and solutions to encouraging the sustainability of supply chains. This study aims to understand the factors shaping the challenges and potential solutions to transitioning towards more sustainable production of cocoa (commodity) and chocolate (end product) in the context of commitments to zero deforestation. The results can be used to inform what elements zero-deforestation pledges should take into account in order to contribute to sustainable development, especially in terms of addressing livelihoods. This will also help inform the future directions, policies, investments and other decisions that could contribute to the transition from a singular focus on zero deforestation to a more holistic approach that embraces sustainability.

Methods

Sample

Stakeholders were interviewed in six countries: Ghana and Brazil (the second and sixth largest producers of cocoa in the world); The Netherlands (the largest global importer and processor of cocoa); the USA and Belgium (major consumers of chocolate); and Denmark (during an international cocoa conference).

Stakeholders were selected using purposive and snowball sampling approaches. They included farmers, manufacturers, investors, government representatives, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), researchers and technical assistance (TA) providers working on cocoa or similar agricultural commodities. Fifty-nine interviews with 69 stakeholders were carried out between October 2014 and July 2015 (six interviews accommodated two or three people). Supplementary Material S3 provides more details on the methods.

Interviews

The majority of the interviews were carried out in person by the first author of this paper (MCC). Because the pool of stakeholders ranged from cocoa farmers to industry representatives, the interviews were not designed to have one set of specific questions. Instead, an interview guide was developed based on five pertinent topics drawn from a review of the literature. This helped give focus to the interviews, but also allowed the interviewer to customize questions to individual stakeholders’ realities. The open-ended approach was based on the understanding that stakeholders’ preferences are mainly socially constructed, based on different interests and experiences and shaped by social interaction (Rubin & Rubin Reference Rubin and Rubin2011).

At the start of each interview, interviewees were informed that the research was examining the three dimensions of sustainable development (social, environmental and economic) and that their responses would be kept anonymous. In most interviews, except with farmers and some producing country actors, we explained that the research was being carried in the context of the recent industry commitments to promote zero-deforestation supply chains. The interview guide is summarized in Supplementary Material S3.

Analysis

Both Atlas Ti (qualitative data analysis and research software) and open coding procedures (Strauss & Corbin Reference Strauss and Corbin1990) were used to analyse the interview responses and to identify codes and themes. A final list of 38 codes organized into six themes was developed. A sample of five coded interviews were checked by one of the co-authors (NJH) to ensure suitability of the codes and coding process before all remaining interviews were coded.

Results

Stakeholder Typology

Approximately half of the stakeholders interviewed were from cocoa-producing countries and the other half were from cocoa-importing and/or cocoa-consuming countries (Table 1). The respondents represented nine different stakeholder groups (Table 2).

Table 1 Number of interviews per stakeholder group per sample country. NGO=non-governmental organization

Table 2 Stakeholder group descriptions. NGO=non-governmental organization

Thematic Analysis

From the stakeholders’ responses, six main themes emerged: (1) policies, regulations and markets; (2) knowledge; (3) landscape and supply chain approaches; (4) coordination; (5) relationship between sustainability dimensions; and (6) private sector engagement.

A sample of interviewees’ responses provide details underpinning the findings (Supplementary Table S2).

Policies, Regulations and Markets

Approximately half the stakeholders, with representatives from all categories, agreed that policies featured as both a challenge and a solution when it comes to encouraging the sustainability of commodities at local and global levels. One NGO representative summarized, “If there is no basic rule of law it all fails. We need property rights, and other structure systems. The market push is important, but it cannot do it all alone, as it would lead to inequality.” A TA provider contested, “We should not try to regulate everything, only if there is a direct driver, as too many regulations are not efficient because they require monitoring and are costly.”

About a quarter of stakeholders suggested focusing on market-based approaches. One TA noted, “Industry commitment is more sustainable than government-imposed regulations, as it is a more stable driver for sustainability. The private sector always looks for gaps in regulations to avoid anyway, so making the business case is better.” Nonetheless, a small group of mostly industry stakeholders commented on the lack of market demand for good-quality, sustainable or certified cocoa and noted that supply and demand ‘come hand in hand’. Thus, a handful of stakeholders suggested that policies should focus on encouraging demand for sustainable products to support market-based approaches.

Certification as a market tool was widely discussed. The majority of industry stakeholders consider it a flawed process. A trader noted, “There are many sustainability challenges that certification does not touch upon, so certification bodies should be more of a driver and a guide of sustainability, identifying gaps (e.g., deforestation) and proposing ways for all to address them. Instead, they are lobby groups that hold companies to ransom.” The majority of farmers, on the other hand, reported more benefits than downsides, with one stating, “It is a tool to help manage farms in a better way.”

Knowledge

The majority of stakeholders, with representatives from all categories, agreed that there is still very little information and data available to the different actors to improve sustainability. Examples include: lack of market, social and environmental information, as well as tools to guide development assistance and corporate sustainability projects; lack of TA to farmers; and a lack of information on the real impacts of climate change, on sustainable production practices and to inform the business case for the private sector. To address this, a government representative from a producing country suggested, “A lot of it boils down to research. We need to get the basis of what is happening and show the trends to the private sector that this ‘business as usual’ is leading to decreased productivity. This is a way to have a win–win scenario for all.” A TA provider added, “Farmers also need training on managerial and bargaining skills, not only on how to increase yield,” a comment that demonstrates how TA is sometimes designed to address industry needs, rather than farmers’ interests and long-term well-being.

Landscape and Supply Chain Approaches

Led by NGOs, approximately half of the stakeholders from all groups, except investors and farmers, noted the benefits of adopting a landscape approach. One NGO commented, “Different companies source from different farmers spread in the land, so the same patches of mosaics of the environment, in a way, belong to different companies. If one company is trying to address deforestation and the other is not, this poses a problem. If not all the farmers within that landscape are certified; it is difficult to address deforestation. Monitoring is also very difficult patch per patch.” Only a few stakeholders noted the challenges associated with promoting landscape-wide interventions.

Climate change was also widely discussed by about half of the stakeholders from all groups. The main argument was that synergies between the reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) framework and efforts to ‘green’ commodities (e.g., monitoring systems and safeguards) should be explored instead of having processes running in parallel. But c. 10% of the stakeholders saw carbon as a wrong single focus. A government representative from a producing country summarized, “The focus should not only be on carbon, but also on other benefits because that is when people will start getting interested. Carbon does not drive farmers’ interest as much water, for example.”

Focusing on the rest of the supply chain, more than half of the stakeholders from all groups, but not investors, spoke about the importance of working with different actors along supply chains to inform them about the benefits of becoming more sustainable. A trader noted, “We need to raise awareness of all players in the supply chain, for example stimulate retailers to demand certified products.” A private company complemented this by saying, “Sometimes companies do not understand the risks and rewards, so this exercise to explore the supply chain might ensure better sustainability. It is an exercise to discover challenges.” Only a handful of stakeholders highlighted the role of the investment sector in helping to promote change.

Coordination of Activities and Stakeholders

The majority of stakeholders were in favour of promoting more cooperation and coordination between different initiatives. A government representative from a producing country mentioned, “If you look around Ghana, there are many projects and programmes from industry and international organizations trying to deal with cocoa, but I am not sure how these are working together.” Stakeholders noted that more coordination would allow higher cumulative results, including opportunities for scaling up.

Approximately 20% of the interviewees, most of whom were from international institutions from consuming countries, also brought attention to the need to promote better policy coordination. One industry representative summarized, “I am on the board of the International Cocoa Initiative, which was created to look into labour issues along the supply chain. I am mostly concerned about putting in place policies in consuming countries such as boycott campaigns and trade barriers. But these don’t resolve the problem. Cocoa-producing countries should have better policies on the ground on sanitation, teaching/education, which contributes considerably to child labour. In most cases, the child labour is simply related to lack of close schools, which gives farmers no options, so I feel that boycotts alone would only punish the farmers. Policy coherence is very important.”

Some half of the stakeholders highlighted the importance of improving communication and information, especially to consumers and retailers. A TA provider noted, “Consumers do not understand what goes on in the field, so we need to stimulate them to check data, scan the bar code in their smartphone and be interested in how things are produced.”

Approximately 20% of the stakeholders noted that emerging stakeholder platforms are positive forums to bring together diverse groups. However, they also noted that they should be more innovative, integrate the private sector more systematically and overcome competitiveness issues among stakeholders, such as between certification schemes.

Relationship between Sustainability Dimensions

More than half of the stakeholders, but not investors, discussed some type of positive relationship between the sustainability dimensions. Overall, stakeholders agreed that to ensure the delivery of the long-term supply of cocoa and livelihoods, both farms and the landscape where they reside need to be ecologically and socially resilient to, for example, the impacts of climate change. But for that to happen, there is a need for a clear and evidence-based business case on sustainable supply chains and on tested production models and information dissemination and education of farmers on many aspects such as the impacts of climate change in ecosystems that are not resilient. This will allow them to increase yield over time and reduce the pressure on natural forests, while ameliorating their livelihoods.

Nonetheless, about half of the stakeholders highlighted the competition between sustainability dimensions and that economic aspects often take precedent, leaving environmental aspects to be addressed last. Approximately 15% of the stakeholders indicated that sustainability encompasses too many issues that cannot be addressed simultaneously due to limited budgets and human resources.

Private Sector Engagement

Overall, the majority of stakeholders saw added value in engaging the private sector to promote sustainability through identifying and communicating risks (e.g., impacts of climate change, reputation), a view that was led by NGOs, or identifying positive incentives (e.g., de-risking investments), which mostly came from industry, investors and TA providers. Nonetheless, stakeholders highlighted several challenges, such as difficulty in communication (e.g., limited forums to promote discussions), secrecy of information due to competitiveness and a strong emphasis on economic aspects to the detriment of social and environmental issues.

Approximately 20% of the stakeholders, mostly industry and TA providers, highlighted that the private sector is diverse, with differences in perspectives also existing within the same companies; different solutions need to be developed to engage different types of players. A government official from a producing country noted, “Small- to medium-sized enterprises cannot look 20 years ahead of their business; this is different from something that Unilever has to do to survive. We need to come up with innovative options.”

The majority of stakeholders noted that the industry commitments and pledges towards zero deforestation and sustainability are steps in the right direction. One TA summarized, “For cocoa, the big breakthrough to start dealing with sustainability is the fear that cocoa will run out. So industry began committing to use sustainable cocoa only. For them it is a business case – without cocoa there is no Mars – sustainability is guaranteeing the future.”

Discussion

Five areas that deserve further reflection are: stakeholder preferences and power imbalances; policy mix; going from deforestation to sustainability; landscape approach; and supply chain approach.

Stakeholder Preferences and Power Imbalances

This is the first study on the cocoa and chocolate supply chain that explores different perspectives of stakeholders on the challenges and solutions to transition towards a more sustainable supply chain. It reveals that different types of stakeholders have disparate concerns on these issues and the likely solutions (e.g., Table 3).

Table 3 Example of stakeholder concerns and solutions. NGO=non-governmental organization

In practice, it can be a combination of interventions that satisfies all stakeholder perspectives in order to ensure the long-term success of interventions, as stakeholders will likely show higher levels of commitment to a process that promotes solutions that accommodate multiple interests. However, stakeholders are not always treated equally, nor do they have the same opportunities and skills to voice their concerns.

The literature on supply chain management argues that, even though there is a clear interdependence between the different stakeholders, they also have different levels of influence and power over others (French et al. Reference French, Raven and Cartwright1959, Park et al. Reference Park, Chang and Jung2017). This power asymmetry allows more powerful stakeholders to have greater leverage in determining suppliers’ practices (Ulstrup Hoejmose et al. Reference Ulstrup Hoejmose, Grosvold and Millington2013). This leads to the situation whereby farmers, who are often not well educated or informed, do not have a strong voice and their preferences are not prioritized. This may eventually diminish their buy-in, putting in question the entire intervention (e.g., zero-deforestation projects promoted by industry). Thus, it is important to integrate farmers well in the development of these interventions and to build their entrepreneurial skills in order to ensure their long-term commitment to continuing to grow cocoa, as they are the centrepieces of the supply chain.

Policy Mix

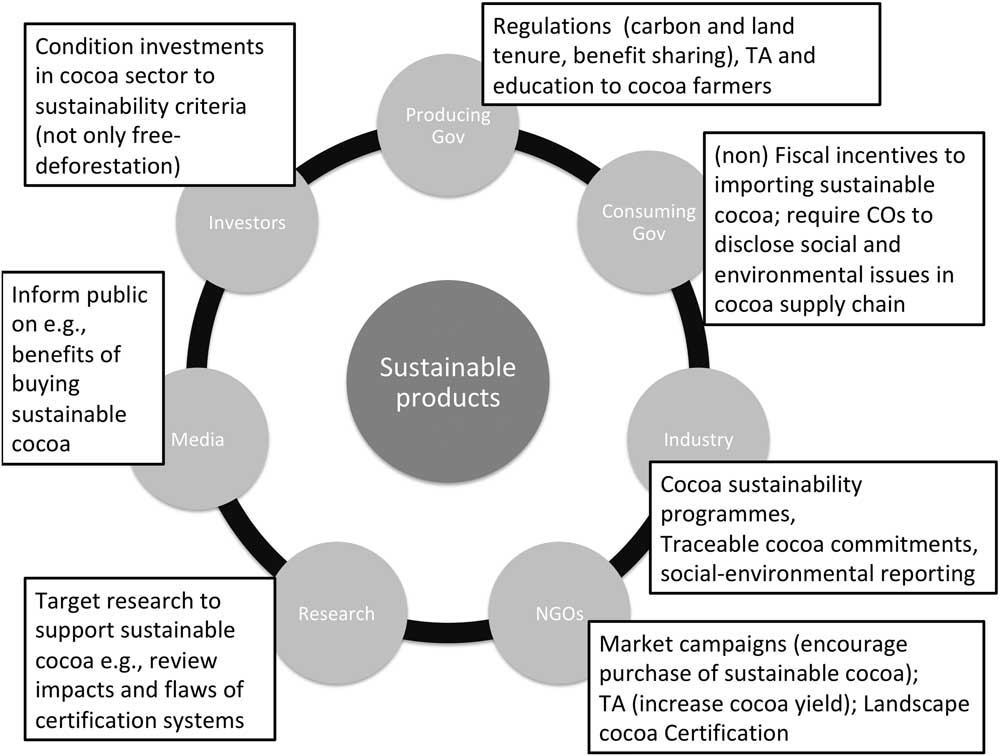

The literature and this study have shown that when designing interventions, policy and market instruments can help advance the agenda (Nikolakis & Innes Reference Nikolakis and Innes2017), but they need to be carefully evaluated and coordinated so as not to do more harm than good. In recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of different instruments, Gunningham and Young (Reference Gunningham and Young1997) argue against a ‘single instrument’ tactic and have proposed a policy mix approach. The goal is to find an optimal combination between instruments, such as voluntary, property rights, regulatory, price based and motivational and informational, along with identifying which stakeholder groups are in the best position to implement them in order to effectively reach the goal – in this case, sustainable development. In the context of cocoa and chocolate, Figure 1 provides examples of what different stakeholders can do in a synergistic manner.

Fig. 1 Policy mix: examples of what different stakeholders can do in a synergistic manner. NGO=non-governmental organization; TA=technical assistance.

From Deforestation to Sustainability

The results of the qualitative assessment showed that deforestation is not the only challenge, and that it is intrinsically connected to all three dimensions of sustainability. However, there is also tension between the three dimensions. Van der Byl and Slawinski (Reference Van der Byl and Slawinski2015) note four general approaches to how tensions can be examined: (i) ‘win–win’ looks for opportunities to reconcile tensions; (ii) ‘trade-offs’ recognizes that the conflict is irreconcilable, so one goal must prevail to the detriment of the other(s); (iii) ‘integrative’ proposes to bring balance between the three goals; and (iv) ‘paradox’ aims to recognize the complex nature of the tensions, as well as how actors work through them, and identify opportunities to generate creative approaches to address them. While the majority of the literature focuses on win–win and trade-off approaches, there is an emerging field proposing an integrative approach combined with paradox analysis (Hahn et al. Reference Hahn, Pinkse, Preuss and Figge2015, Van der Byl & Slawinski Reference Van der Byl and Slawinski2015). It proposes to embrace tensions and recognize that the three elements are interconnected, so none should be prioritized over the others. If this is ignored, the problem is not solved and eventually resurfaces.

Thus, zero-deforestation definitions and interventions should acknowledge and embrace this interconnectivity to ensure long-term impacts. This serves to recognize both the interdependence between livelihoods and deforestation at the landscape level and also the interactions and the chain of events from the production of raw material to the end consumer.

Nonetheless, there is still too little evidence to convince a broad range of stakeholders to address the dimensions concomitantly. Thus, it is paramount that different groups not only focus on pointing out the potential risks, but also help to test and develop incentive systems and benefit-sharing mechanisms that support the uptake of improved production practices. All of this should be while still favouring private sector needs of maintaining a competitive position in the markets, which will increasingly be based on green investment models.

Landscape Approach

Many stakeholders highlighted the need to look at the challenges in the broader landscape where different commodities are produced, rather than being limited to the plot/farm level. Focusing at the landscape level can allow for a more holistic analysis of the challenges at the farm and wider territorial level, instead of focusing on sectorial problems that impede the ability to address cross-boundary drivers of deforestation, which are more cross-sectorial in nature (DeFries & Rosenzweig Reference DeFries and Rosenzweig2010, Sayer et al. Reference Sayer, Sunderland, Ghazoul, Pfund, Sheil, Meijaard and Venter2013). Recent studies have shown that landscape approaches have the potential as a framework to bring together conservation and development goals, helping address deforestation while ameliorating livelihoods, through improving social capital and enhancing community income and employment (Reed et al. Reference Reed, van Vianen, Barlow and Sunderland2017, Sayer et al. Reference Sayer, Margules, Boedhihartono, Sunderland, Langston, Reed and Riggs2017). Nonetheless, there are still many barriers to successfully implementing landscape initiatives such as defining its boundaries, being able to reconcile conservation and development goals (Reed et al. Reference Reed, van Vianen, Barlow and Sunderland2017) and institutional and governance shortfalls (Sayer et al. Reference Sayer, Sunderland, Ghazoul, Pfund, Sheil, Meijaard and Venter2013). Thus, stakeholders should build more alliances to build synergies and move together towards the same aim, avoiding duplication of efforts.

Supply Chain Approach

Despite the unanimous call for integration at the landscape level, only a few stakeholders mentioned the need to think along the entire supply chain from primary production to end products (i.e., chocolate), with most of the emphasis on the upstream part of the supply chain. This narrow approach is problematic for two main reasons: first, research on life cycle assessment of chocolate has revealed that sugar, packaging, transportation and especially milk powder contribute to significant emissions (Büsser & Jungbluth Reference Büsser and Jungbluth2009, Marton Reference Marton2012, Humbert & Peano Reference Humbert and Peano2014). Thus, focusing solely at the landscape level mostly requires only farmers to change practices and address emissions, not the other stakeholders along the supply chain, which raises the question of fairness. Second, because the drivers of deforestation originate not only at the landscape level, they have more distant origins, mainly related to the consumer markets. As the industry respondents mainly pointed out, there is very little demand for sustainable/certified cocoa from consumers and retailers; thus, indirectly it seems there is very little ‘demand’ for issues such as deforestation to be addressed.

Interviewees acknowledged that there is still very little supply chain integration, with many stakeholders such as retailers and consumers not well aware of the impact of production and procurement systems on the ground, and therefore they often make demands that are not necessarily the most important for the farmers. Thus, it is paramount to think of supply chain interventions whereby all the different actors are targeted with information that is understandable to them in order to encourage more demand for sustainable products that address the needs of different actors in the supply chain, especially the livelihoods of farmers who are the core stakeholders in the chain.

Conclusion

Zero-deforestation commitments are seen as being an important step forward to help promote forest conservation. Nonetheless, discourses have been rendering an analysis of the problem that is too narrow, emphasizing deforestation and emissions at the upstream/ground level when there are many other environmental and social challenges that need addressing before cocoa and chocolate can be called sustainable. For zero-deforestation commitments to effectively contribute to sustainable development, a broader discussion and actions are needed in which the interdependencies of stakeholders along the supply chain are acknowledged and the deforestation issue is addressed concomitantly with other challenges, especially livelihoods. Thus, stakeholders along the chain need to work together in a coordinated fashion towards stimulating a market that rewards not only zero-deforestation cocoa, but also sustainable chocolate production. Such a broadened approach will enhance the likelihood of improving long-term forest conservation, and also help generate more positive livelihood outcomes for the cocoa farmers involved, who are the heart of the supply chain.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit http://www.journals.combridge.org/ENC

Supplementary material can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0376892918000243

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the interviewees that participated in this study, Verina Ingram (Wageningen University) and Denis Sonwa (CIFOR) for their valuable insights and the reviewers for their constructive comments.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO; MCC, grant number 32/14A) and the Department for International Development (DFID; MCC and IN, accountable grant component code 202834-101, purchase order 40054020).

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

None.