INTRODUCTION

Negative attitudes toward wolves and other large carnivores can stem from conflicts with the species such as depredation (killing or injury) of domestic animals, fear for personal safety and perceived competition for game species (Baker et al. Reference Baker, Boitani, Harris, Saunders and White2008; Rust & Marker Reference Rust and Marker2013). However, attitudes toward large carnivores are not solely determined by conflicts and direct costs associated with living alongside them (Treves & Bruskotter Reference Treves and Bruskotter2014). According to Dickman et al. (Reference Dickman, Marchini, Manfredo, Macdonald and Willis2013, p. 111), they are ‘the product of a dynamic and complex web of individual, societal, and cultural factors’. Negative attitudes can in turn influence human behaviour, including poaching, which is a major threat to large carnivores worldwide (Ripple et al. Reference Ripple, Estes, Beschta, Wilmers, Ritchie, Hebblewhite and Wirsing2014). Some authors suggest hunting predators will improve public attitudes toward these animals (reviewed in Treves Reference Treves2009) and wolf hunting is being promoted in several regions as a strategy for managing wolves. A wolf hunting and trapping season (referred to throughout the paper as wolf hunt) has been hypothesized to improve attitudes toward wolves among hunters and, in turn, foster stewardship of the species as valued game (Linnell et al. Reference Linnell, Swenson and Anderson2001; Heberlein & Ericsson Reference Heberlein and Ericsson2008; Treves Reference Treves2009). According to Heberlein et al. (Reference Heberlein, Ericsson and Wollscheid2003, p. 393), ‘Making wolves a game species even in a limited number might make wolves part of the utilitarian culture of wildlife and provide rural residents with a greater sense of control. . .Efforts should be put into making wolves valuable to hunters. . .’. Other studies show hunter and non-hunter support for a wolf hunt, but with little inclination on behalf of hunters to conserve wolves (Ericsson et al. Reference Ericsson, Heberlein, Karlsson, Bjärvall and Lundvall2004; Treves & Martin Reference Treves and Martin2011).

Some consider attitudes as expressions of underlying wildlife values, which can influence human behaviour (Bright & Manfredo Reference Bright and Manfredo1996; Manfredo et al. Reference Manfredo, Teel and Bright2003). Attitudes and subsequent individual behaviours can influence management decisions for predators and may determine sustainability of their populations in many regions. Understanding data on public attitudes has the potential to guide policymakers to implement politically acceptable solutions that balance wildlife conservation with human needs. Cross-sectional studies of attitudes toward large carnivores, in particular wolves in the USA and internationally, show mixed results. Although some studies suggest that there has not been observable change in attitudes toward wolves in recent times, others show a reduction in positive attitudes toward wolves and increased support for lethal control in cross-sectional comparisons (Dressel et al. Reference Dressel, Sandström and Ericsson2014). Research in Sweden showed widespread support for wolves in the early stages of recovery (Ericsson & Heberlein Reference Ericsson and Heberlein2003; Ericsson et al. Reference Ericsson, Sandström and Bostedt2006), and conditional support for a wolf hunt to control the population (Ericsson et al. Reference Ericsson, Heberlein, Karlsson, Bjärvall and Lundvall2004). Bruskotter et al. (Reference Bruskotter, Schmidt and Teel2007) found more negative attitudes among hunters and consistency in attitudes over time among other subgroups of Utah residents in a study from 1994 to 2003. Recent research in Montana indicates low tolerance for wolves in the state and strong support for the wolf hunt (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Pauly, Kujala, Guide, King and Skogen2012). Some data have shown that, prior to a hunt, attitudes toward wolves became more negative over time and in increasing proximity to wolf territories (Karlsson & Sjöström Reference Karlsson and Sjöström2007; Treves et al. Reference Treves, Jurewicz, Naughton-Treves and Wilcove2009, Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013). Longitudinal research showed a decline in tolerance among Wisconsin residents living in wolf range was associated with competitiveness over deer, greater fear for personal safety, and a rise in endorsements for lethal control of wolves, including a wolf hunt (Treves et al. Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013). That study operationalized tolerance as a multi-item scale variable, an approach we followed here (see Methods).

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) launched a wolf hunting and trapping season in winter 2012, allowing for public harvest of wolves for the first time since 1957, when the wolf bounty ended. Following federal delisting of the wolf from the Endangered Species Act, the wolf hunt was mandated by the Wisconsin state legislature under Act 169, and signed into law on April 2, 2012 (Wydeven et al. Reference Wydeven, Wiedenhoeft, Schultz, Thiel, Jurewicz, Kohn, Van Deelen, Wydeven, Van Deelen and Heske2009, Reference Zinn and Pierce2012). Goals of the hunt and wolf management included reducing the wolf population to the state management goal of 350 wolves (at the seasonal low estimate), reducing conflict with humans, and ‘maintaining social tolerance’ for the species (WDNR 2013). In regard to the third goal, we measured attitudes toward wolves in a longitudinal study based on a survey that was conducted both before and after the inaugural wolf hunt.

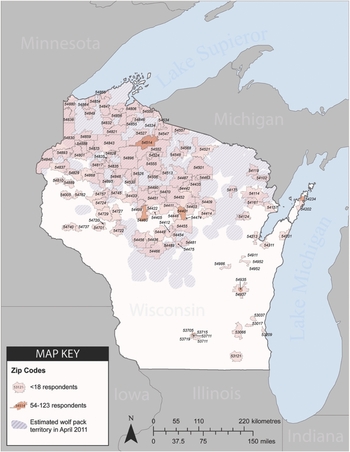

Based on the findings of previous attitudinal studies, we predicted that attitudes toward wolves and wolf management would have changed since 2009 among residents in Wisconsin's wolf range (see Fig. 1). Given that implementation of a wolf hunt occurred after the respondents were first surveyed, we were particularly interested in the potential effects that this policy change would have exerted on hunters’ attitudes. Changes in attitudes toward wolves have been documented over varying time periods (Duda et al. Reference Duda, Bissell and Young1998; Ericsson & Heberlein Reference Ericsson and Heberlein2003), amid changes in wolf numbers and wolf policies (Treves et. al Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013). Collectively, policy, management (Wydeven et al. Reference Wydeven, Wiedenhoeft, Schultz, Thiel, Jurewicz, Kohn, Van Deelen, Wydeven, Van Deelen and Heske2009), perceived risks, and media representations of wolves may influence attitudes (Gore & Knuth Reference Gore and Knuth2009; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Bruskotter and Fan2010; Bruskotter et al. Reference Bruskotter, Vucetich, Enzler, Treves and Nelson2013; Treves & Bruskotter Reference Treves and Bruskotter2014), and there were several publicized controversial changes in wolf management during the sampling interval for this study. These include relisting and delisting from the Endangered Species Act (status of federal protection), resumption of lethal control, legal controversies over the delisting and lethal control, and, most notably, the declaration and implementation of the wolf hunt. Isolating the causes of attitudes or attitude changes with certainty would require an experimental manipulation where an intervention could be applied as a treatment at a known time and under set conditions, while simultaneously treating a control group. Given the infeasibility of such an experiment, we approached causal inferences through before-and-after comparisons of the same subjects, who are all residents of Wisconsin's wolf range.

Figure 1 2013 Survey respondents by zip code in and outside of wolf range in Wisconsin. Zip codes 54324 and 54402 are missing because they lack spatial data and could not be mapped. Zip code boundaries are according to census data from the USA (US Census 2012). Wolf-pack polygons are from Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources files, buffered by 5 km to capture common extraterritorial movements.

Given that four years passed between our surveys, we had imperfect control over the interventions (policy or otherwise) that might have caused changes in our panelists. Our survey questionnaire items focused on the public hunting and trapping season, given this policy intervention was prominent in the news following the legislative mandate for the inaugural wolf hunt. We expected the wolf hunt to be a key influence on attitude change relating to wolves and wolf policy.

METHODS

Sampling

From 2001 to 2009, Wisconsin state residents were surveyed using three mail-back, self-administered questionnaires (Naughton-Treves et al. Reference Naughton-Treves, Grossberg and Treves2003; Treves et al. Reference Treves, Jurewicz, Naughton-Treves and Wilcove2009, Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013). In 2013, members of our team surveyed previously-sampled Wisconsin residents, detailed in Naughton-Treves et al. Reference Naughton-Treves, Grossberg and Treves2003, Treves et al. Reference Treves, Jurewicz, Naughton-Treves and Wilcove2009, and Treves et al. Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013 (Table 1). One panel of respondents was first sampled in 2001, another panel in 2004, and only those members of both panels who lived in wolf range were resampled in 2009. The 2001 panel lived within wolf range and was shown to have had high exposure to wolves. The 2001 panel's initial 528 members were comprised of 67 landowners with past, verified wolf attacks on domestic animals and 312 landowners from the same counties selected randomly from commercially available address lists; 48 bear hunters with verified wolf attacks on their hunting dogs and 101 members of the Wisconsin Bear Hunters Association selected at random (Naughton-Treves et al. Reference Naughton-Treves, Grossberg and Treves2003). The 2004 panel was shown to have had lower exposure to wolves in comparison to the 2001 panel. The 2004 panel's initial 1364 members were selected randomly from commercial address lists of three urban and three rural postal codes. Half the postal codes were in wolf range and half outside. In 2009, all past members of the 2001 panel, and the 687 members of the 2004 panel who had residential addresses in wolf range (three postal codes: Butternut, Owen, and Wausau) were resampled (Treves et al. Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013).

Table 1 Longitudinal data collected from Wisconsin survey panels: 2001–2013. Data and methods described in Naughton et al. (Reference Naughton-Treves, Grossberg and Treves2003) and Treves et al. (Reference Treves, Jurewicz, Naughton-Treves and Wilcove2009). See Methods for definition of high exposure.

In April 2013, we resampled all 736 respondents from Treves et al. Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013 (last surveyed in 2009), known as the wolf range panel, in addition to all 575 respondents from the 2004 survey who lived outside of wolf range (three postal codes: Madison, Sister Bay, and Fond du lac; Treves et al. Reference Treves, Jurewicz, Naughton-Treves and Wilcove2009; see Hogberg Reference Hogberg2014 for survey results outside of wolf range). We mailed questionnaires (see Supplementary material) to previous respondents living in wolf range, including a cover letter, incentive payment of US$ 2, and a postage-paid mail-back envelope. We sent reminder postcards two weeks later. We then conducted longitudinal analyses for respondents who had been measured in 2009.

We defined hunters as respondents who reported having hunted ‘in the past two years’ (n = 342) or having ‘regularly hunted at any other time in life’ (an additional 94 respondents). The wolf range panel was unrepresentative of Wisconsin residents in two ways. The sample contained a high percentage of hunters (81%) and significantly more men (86%) than are representative of the region within the state. This is due to the designs of the 2001 and 2004 panels. The 2001 panel was designed to over-represent bear hunters and people with verified losses to wolves (22%). The 2004 panel was biased toward males because commercially available address lists generally provided a male head of household (Treves et al. Reference Treves, Jurewicz, Naughton-Treves and Wilcove2009). Although this sample is not representative, our sampling approach allowed us to report specifically on the attitudes toward wolves and wolf policy of a group with strong views of wolves. These are key interest groups when considering direct individual behaviour toward wolves, or indirect political action toward wolf policy and state management of wolves (Naughton-Treves et al. Reference Naughton-Treves, Grossberg and Treves2003, Treves et al. Reference Treves, Jurewicz, Naughton-Treves and Wilcove2009).

Responses

In 2013, we received 538 responses from the wolf range panel. Twenty-four questionnaires (3.2%) were returned unanswered, 174 (23.6%) were not returned, and 538 (73%) were returned with data. Only one of the 538 surveys had identity codes removed, and 71 (13.2%) did not match sex and age of the original respondent, for a total of 72 (13.4%) ‘unintended’ recipients in 2013. Overall response rate was 84% when we discounted undeliverable and unintended recipients (538 / [736 – 24 – 72]).

We measured change in attitudes over time within the wolf range panel. We employed both longitudinal methods with residents who had been asked the same questions in 2009 and cross-sectional methods for new questions. Longitudinal studies allow for analysis of change within individual responses over time, and reduce common method variance bias in comparison to cross-sectional studies (Donaldson & Grant-Vallone Reference Donaldson and Grant-Vallone2002; Rindfleisch et al. Reference Rindfleisch, Malter, Ganeson and Moorman2008).

Operationalizing tolerance

In 2009 and 2013, we posed nine statements assessing beliefs, emotions, and behavioural intentions toward wolves and wolf management. We asked respondents to choose one of five responses on an ordinal scale and assigned corresponding scores for quantitative analysis: strongly agree (1), agree (2), neutral (3), disagree (4), strongly disagree (5). We included four negative and five positive statements that reflected beliefs, emotions, or intentions. Two statements related to beliefs about wolves and deer, two about wolf ecology generally, two about hunting wolves, two about wolf-related emotions, and one related to wolf harm to domestic animals and related management preferences (for exact wording, see Table 2). We combined these nine statements arithmetically into a collective multi-item variable, which we refer to as the tolerance construct, similar to the scaled tolerance construct used in Treves et al. (Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013), albeit using more items. Following Manfredo and Dayer (Reference Manfredo and Dayer2004), we do not assume tolerance implies an action or behaviour. Following Treves et al. (Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013), the operational construct does not imply behaviour supportive of wolves or opposed to wolves, but it does reflect attitudes and behavioural intentions that might predict behaviour if a respondent had the opportunity to act (following Ajzen Reference Ajzen1991’s theory of planned behaviour). It is convenient to refer to a single concept in constructing a multi-item scale variable, and referring to its direction, thus tolerance and intolerance are used and widely understood as opposites (Vynne Reference Vynne2009; Karlsson & Sjöström Reference Karlsson and Sjöström2011; Slagle et al. Reference Slagle, Zajac, Bruskotter, Wilson and Prange2013; Bruskotter & Wilson Reference Bruskotter and Wilson2014).

Table 2 Responses in 2013 and changes in responses since 2009 to multi-item tolerance variable among residents of wolf range (Wisconsin, USA). Agree and disagree responses also include strongly agree and strongly disagree responses, respectively. Significance: *p = 0.042, **p < 0.0001.

Our hypothesis was that attitudes toward wolves among residents in wolf range would have changed since 2009. To test this, we calculated changes in responses to the nine statements within the tolerance construct. We subtracted 2013 response scores (scale of 1 to 5) from 2009 response scores for each statement to determine individual change values. For the negative statements, we converted response scores to negative values. We then summed the change values for each statement to determine total change in tolerance to the multi-item variable per respondent. Positive values of change indicated higher tolerance over time and negative values indicated lower tolerance over time (Fig. 2). The maximum change value from tolerant in 2009 to intolerant in 2013 was negative thirty-six, representing the shift from strongly agree to strongly disagree with five positive statements (1 – 5 = –4; –4 × 5 = –20) in addition to the shift from strongly disagree to strongly agree with four negative statements (–5 – (– 1) = – 4; –4 × 4 = – 16). The maximum change value from intolerant in 2009 to tolerant in 2013 was also thirty-six, representing the shift from strongly disagree to strongly agree with five positive statements (5 – 1 = 4; 4 × 5 = 20) in addition to the shift from strongly agree to strongly disagree with four negative statements (–1 – (–5) = 4; 4 × 4 = 16).

Figure 2 Calculations to determine changes in response to the multi-item variable (tolerance construct) between 2009 and 2013.

We tested internal reliability of the nine items in our tolerance construct using Cronbach's Alpha. Within the nine-item construct, we tested for hunter bias, non-response bias, and gender bias using a two-sample Student's t-test assuming unequal variances. We used a one-sample, two-sided Student's t-test for change within individual responses from 2009 to 2013. We also applied this test to each of the nine statements to discern which statements revealed the largest changes across individuals. Additionally, to evaluate if our bounded five-point response scales had biased estimates of change, we examined statements that showed significant change over time. We evaluated the amount of underestimation by subtracting the extreme positive responses (strongly agree or strongly disagree with a positive or negative statement, respectively) from the extreme positive responses (strongly agree or strongly disagree with a negative or positive statement, respectively).

In addition, we estimated self-reported change in tolerance. We asked respondents to report their tolerance in two slightly different grammatical forms. First, in 2009, we posed the statement, ‘My tolerance for wolves would increase if people could hunt them,’ and then, in 2013, we posed the statement, ‘My tolerance for wolves has increased since people can hunt them’. Given the hunting and trapping season opened in 2012, we were forced to change the wording between 2009 and 2013. We assumed the two questions measured very similar attitudes, therefore we subtracted the response in 2009 from that in 2013 using the same scoring as in the tolerance construct (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree). The scale was from negative four (towards disagreement); (1–5) to four (towards agreement); (5–1). We subtracted the response in 2013 from that in 2009 to measure change, where negative values indicated a decrease in agreement, and positive values indicated an increase in agreement over time, and applied a one-sample, two-sided Student's t-test for change in individual response from 2009 to 2013. We used JMP software for all statistical analyses (SAS Institute 2010).

RESULTS

Wolf range panel characteristics

Eighty-one per cent of resampled wolf range respondents were hunters (respondents who reported having hunted ‘in the past two years’ or having ‘regularly hunted at any other time in life’); (89% of males, and 37% of females). Eighty-six per cent of respondents were male, and the average age was 55 years old. Results from the 2013 questionnaire indicate the majority (66%) of wolf range respondents strongly approved of the legislative decision to open the 2012–2013 wolf hunting and trapping season, followed by 13% who somewhat approved, 9% who were neutral or did not know, 5% who somewhat disapproved, and 7% who strongly disapproved (n = 454).

Tolerance hypothesis

We predicted that tolerance for wolves changed among residents of wolf range. We found significant change since 2009 within individual responses to the tolerance construct (n = 410, t = –6.2, p < 0.0001), which signified a decline in tolerance (Fig. 3). Tolerance decreased since wolf range respondents were previously sampled in 2009 with an average shift toward intolerance of –1.66. When split into subgroups with varying levels of approval for the legislative decision to hold the 2012–2013 harvest, we found there was a significant decline in tolerance over time among those that strongly or somewhat approved of the decision to hold the harvest (80% of total sample, n = 398); (n = 52, t = –2.18, p = 0.034; n = 264, t = –8.32, p < 0.0001, respectively). We found no significant change in tolerance occurred among those that were neutral, somewhat, or strongly disapproved of the decision to hold the 2012–2013 harvest (n = 27, t = –0.88, p = 0.39; n = 24, t = 0.77, p = 0.45; n = 28, t = 1.48, p = 0.15, respectively). Our nine survey questions were internally reliable (five positive and four negative statements, Cronbach's alpha = 0.906 in 2013 and 0.907 in 2009). We found moderate consistency in predicting individual change in response to the nine statements, indicating that some questions showed more or less change than others (Table 2) (Cronbach's alpha, as applied to change values from 2009 to 2013 = 0.69).

Figure 3 Change in tolerance construct among residents of wolf range, Wisconsin, USA, 2009 to 2013. Negative values indicate shift towards intolerance over time (scale = +36 to –36); (mean = –1.66n = 410, t = –6.2, p < 0.0001).

Respondents we defined as hunters within wolf range showed significantly lower tolerance for wolves since 2009 (n = 327, t = –6.45, p < 0.0001). We found no difference between hunters and non-hunters within wolf range for change in the tolerance construct (t = 1.03, df = 406, p = 0.302). Both groups showed a similar decline in tolerance over time.

Our wolf range respondents in 2013 did not significantly differ from our non-respondents in their answers to the nine-item tolerance construct posed in 2009 (t = –0.44, df = 354.62, p = 0.66).

We calculated net shift in response from 2009 to 2013 by subtracting the percentage of responses shifted toward agreement with a statement from that of responses shifted toward disagreement with a statement (Table 2). Four items showed significant changes within individuals from 2009 to 2013 among wolf range residents; there was a 35% net shift toward agreement with the statement ‘Killing wolves is the only way to stop them from threatening farm animals and pets’ (n = 410, t = –9.01, p < 0.0001); a 17% net shift toward agreement with the statement ‘I think Wisconsin's growing wolf population threatens deer hunting opportunities’ (n = 410, t = –5.14, p < 0.0001); a 45% net shift toward disagreement with the statement ‘We should let nature determine the number of wolves’ (n = 410, t = –10.73, p < 0.0001); and a 12% net shift toward disagreement with the statement, ‘I would oppose all hunting of wolves’ (n = 410, t = –2.4, p = 0.042).

To evaluate if our five-point response scales had biased estimates of change, we examined the four statements that showed significant change over time and determined if the scale limited respondents who wished to select a more extreme response. In 2013, we found the extreme negative responses outnumbered the extreme positive responses by 29–53%. Therefore, we may have underestimated the decline in tolerance reported above.

Bias

We found a significant difference between males and females within wolf range in terms of change in tolerance (t = 2.34, df = 57.05, p = 0.02). Mean change in tolerance for males was –1.9 (decrease in tolerance, n = 361, t = –6.72, p < 0.0001). Mean change in tolerance for females was +0.17, effectively zero (no change in tolerance, n = 47, t = 0.2, p = 0.84).

Self-reporting of tolerance

In 2013, when asked to report change in tolerance since the wolf hunt, 36% of resampled wolf range residents agreed with the statement, ‘My tolerance for Wisconsin wolves has increased since people can hunt them.’ 27% of wolf range residents reported being neutral, and 37% disagreed with the statement (n = 406). When compared to the same individuals’ prior responses to the similar 2009 statement, ‘My tolerance for Wisconsin wolves would increase if people could hunt them’, we found a net shift (20%) toward disagreement. Wolf range respondents shifted an average of –0.51 on a scale of –4 to +4, indicating lower tolerance (n = 406, t = –6.74, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4).

Figure 4 Change between 2009 and 2013 in self-reported tolerance measured with two different statements: ‘My tolerance for wolves would increase if people could hunt them’ (2009), and ‘My tolerance for wolves has increased since people can hunt them’ (2013). See Methods for estimation of change. There is a net shift of 20% towards disagreement over time (scale = +4 to –4); (mean = –0.51, n = 406, t = –6.74, p < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Understanding longitudinal changes in attitudes toward large carnivores is a vital step in assessing public opinion regarding new policies for managing controversial species. Contrary to the prediction that a wolf hunt has the potential to increase tolerance for a carnivore species (Ericsson & Heberlein Reference Ericsson and Heberlein2003; Treves Reference Treves2009), we found no evidence that individual tolerance for wolves among wolf range residents increased in the year following the inaugural 2012 wolf hunting and trapping season. Although a majority approved of the legislative decision to hold the wolf hunt, we measured a general reduction in tolerance over time among male respondents who were hunters in wolf range since 2009. This result is consistent with previous research in Wisconsin, indicating a trend toward declining tolerance for wolves and increased support for lethal control (Treves et al. Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013).

Conversely, our sample of female respondents within wolf range (n = 47) showed no significant change in tolerance. Women and men have been shown to perceive risk differently with regard to livestock loss and resource competition, and they also vary in their support for wildlife interventions, such as non-lethal deterrents and lethal control (Gore & Kahler Reference Gore and Kahler2012). Women are generally more likely to express fear of large carnivores, but are also more likely to disapprove of killing threatening carnivores (Zinn & Pierce Reference Zinn and Pierce2002; Kellert Reference Kellert1997). More broadly, in their survey of thousands of residents across the western USA, Teel & Manfredo (Reference Teel and Manfredo2009) determined that, relative to other sociodemographic variables, gender is an exceptionally strong predictor of wildlife value orientation. These results underscore the importance of including women in wildlife policy formulation and the need for further study of women's perceptions and attitudes toward wolves and other large carnivores.

We found significant changes in responses to four questions within the tolerance construct (Table 2). Wolf range residents increasingly agreed that wolves should be managed, in part by lethal control of wolves implicated in depredations, and they believed that the wolf population competed with humans for deer in Wisconsin. Support for lethal control was consistent with approval for the decision to implement the wolf hunt. Our findings are similar to those from a study of the same panel before the wolf hunt. Namely, respondents’ approval for public hunting, trapping, and legal lethal control were associated with decreased tolerance for wolves (Treves et al. Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013). In other words, there is no clear indication as of yet that hunters newly permitted to hunt wolves will hold more positive attitudes toward wolves, much less feel a sense of stewardship for the species.

Holsman (Reference Holsman2000) proposed that individual differences among recreationists including hunters may better predict intent to steward wildlife than does participation in hunting itself. One of the key individual differences to consider in the context of wolf hunting includes motivations for hunting. In order to understand the long-term potential for hunter stewardship as an effect of the wolf hunt, future research should focus on the motivations and behaviours of hunters (Treves Reference Treves2009). Primary motivations for wolf hunting and trapping are likely to shape hunters’ preferred population levels and management policies. Hunters that are motivated by the recreational value of the hunt (such as the challenge of the hunt, skills and methods training, or time spent outdoors), may in time move towards more positive attitudes and eventually stewardship of the species’ population. However, wolf hunters that are motivated to participate in the hunt by fear or hostility would likely be less inclined to steward large carnivore populations.

Further investigation of risk perception versus the realized occurrence of carnivore conflict among people living in wolf range may inform wildlife management policies and outreach to the public about the actual risks of wolves in their communities. Because our study found that wolf range respondents increasingly believed that killing wolves is the only way to stop them from threatening animals and pets, future research could also explore attitudes toward other non-lethal means of reducing depredation from wolves, such as anti-predator fencing, strobe light/siren devices, and livestock guarding animals (Shivik et al. Reference Shivik, Treves and Callahan2003).

Since a plurality of our respondents believed that a growing wolf population threatened deer hunting opportunities, future research should explore attitudes toward strategies other than a public harvest that may reduce this perceived threat to deer hunting in wolf range. We urge managers not only to focus on risks and conflict in public communication, but also include benefits of carnivore conservation (for example ecosystem health, or aesthetic value of viewing wildlife). Such a communication strategy proved influential in improving individual attitudes toward black bear conservation in Ohio (Slagle et al. Reference Slagle, Zajac, Bruskotter, Wilson and Prange2013).

While studies have shown the correlates of positive attitudes toward large carnivores (such as distance from wolf territory, proximity to urban populations, less exposure/experience with wolves, reduction of damage caused by large carnivores, or trust for management authority; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Ericsson and Heberlein2002; Kansky & Knight Reference Kansky and Knight2014; Olsen et al. Reference Olson, Stenglein, Shelley, Rissman, Browne-Nuñez, Voyle, Wydeven and Van Deelen2014), further study is required to understand which factors are most successful in driving positive change. Experiments (for example controlled, before-and-after or longitudinal) will reveal which interventions can actually change tolerance (Slagle et al. Reference Slagle, Zajac, Bruskotter, Wilson and Prange2013) and whether these last over time.

We found a net (20%) shift toward disagreement with the statement, ‘My tolerance for Wisconsin wolves has increased since people can hunt them’ from 2009 to 2013. We offer three possible explanations for this finding. (1) Although respondents in 2009 anticipated their tolerance for wolves would increase if people could hunt them, by 2013 they were dissatisfied and it affected their self-assessed tolerance for wolves. For example, wolf range residents may have wanted declines in human-wolf conflict, a greater or lesser reduction in the wolf population, more or fewer hunting permits issued, or other events or effects to take place. (2) There may have been a cognitive bias, where respondents were ‘voting’ for a wolf hunt in 2009, namely hoping by agreeing they might prompt its implementation. Support for the decision to hold a wolf hunt is consistent with this hypothesis (majority within wolf range). By 2013, our respondents may no longer have felt the need to voice encouragement. (3) Cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger Reference Festinger1957; Olson & Stone Reference Olson, Stone, Albarracin, Johnson and Zanna2005) posits that people seek consistency in their attitudes and beliefs. Perhaps our respondents in 2009 thought they would become more tolerant of wolves if there were a public hunt but, in 2013, they avoided dissonance by consistently selecting choices that justify reducing wolf populations.

In 2013, some wolf range residents self-reported an increase in their tolerance since people have been allowed to hunt wolves (36%). These self-reports were inconsistent with the trend of declining tolerance that we measured, and show disagreement between self-reports of tolerance versus our multi-item construct of tolerance. Self-reports of tolerance that conflict with measurements of tolerance emphasize the need for longitudinal measures over cross-sectional measures, especially if different questionnaire items are compared across studies. Moreover, the majority of respondents did not report their tolerance had increased or changed since the wolf hunt. We cannot discern whether respondents were unaware of the changes we detected in their own prior responses, or if our self-report question measured something other than change in tolerance.

One limitation of this longitudinal study is that we did not ask respondents to identify as tribal or non-tribal residents. Most tribal residents in the state live within wolf range, and previous research found that Native Americans in Wisconsin had significantly more positive attitudes toward wolves and were less supportive of having a public hunt than non-tribal respondents in previous surveys (Shelley et al. Reference Shelley, Treves and Naughton2011). The wolf plays a prominent role in the creation story of the Ojibwe in northern Wisconsin, and their destinies are said to be intertwined such that what happens to one shall happen to the other (Benton-Banai Reference Benton-Banai1939). Future research should include the perspectives of Native Americans to achieve a more inclusive understanding of shifting public opinion of hunting and trapping seasons, along with other sociological phenomena.

Another limitation of this study stems from the diversity of methods with which researchers define and operationalize tolerance. While our study defines this as a composite measure of attitudes, beliefs, emotions, and behavioural intentions, there is yet no standard method for defining or measuring tolerance. As such, individual statements within the multi-item construct may be interpreted differently by different respondents and observers to signify changes in attitudes other than tolerance. For example, we include two questions related specifically to the circumstances and methods under which respondents approve or disapprove of hunting wolves. These two statements can directly inform approval for the hunt, or otherwise provide information about behavioural intentions towards wolves, thus informing tolerance, or lack thereof for the species.

There are several factors that may have contributed to the observed decline in tolerance for wolves among men living in Wisconsin's wolf range. These factors include: a combination of direct, perceived, and anticipated conflict with wolves in the communities of northern and central Wisconsin, the controversial changes in wolf management during the sampling interval for this study, including the oscillating political status of wolves (relisting and delisting from the Endangered Species Act; Olson et al. Reference Olson, Stenglein, Shelley, Rissman, Browne-Nuñez, Voyle, Wydeven and Van Deelen2014), resumption of lethal control (Treves et al. Reference Treves, Naughton-Treves and Shelley2013), and notably the declaration and implementation of the wolf hunt. Further, the context of the implementation of the wolf hunt (a government-mandated decision) may have had an effect on attitudes. The WDNR allowed for public input on wolf management, including a possible hunt, from 1999–2012 (Treves Reference Treves2008). The legislature then accelerated the process by signing into law Wisconsin Act 169, a mandate to establish the public hunting and trapping season along with emergency rule-making procedures to initiate the wolf hunt by 15 October 2012. The emergency rule-making and widely-publicized controversies over public consultation in developing the specific rules of the new hunt (Durkin Reference Durkin2013; Rowen Reference Rowen2013) could have influenced people's attitudes toward wolves, wolf policy, and management authorities.

In summary, the inaugural wolf hunting and trapping programme in Wisconsin did not reverse the trend of declining tolerance for wolves among male residents (predominantly hunters) who live within the species’ range. While this study focused on longitudinal change in attitudes toward wolves and wolf policy among males, hunters, and people living within wolf range, it is important to consider to what extent policy should respond to a broader range of stakeholder groups (Teel & Manfredo Reference Teel and Manfredo2009). Additionally, with an average age of 55 years old within our sample population, we note that our study focuses on an older generation of Wisconsin residents, and declining tolerance within this group may have been associated with a cohort effect that could have influenced their attitudes towards wolves and wolf policy. Future studies should be broader in scope to determine the views of a wider section of society, including women, Native American and other ethnicities, non-hunters, people living outside of wolf range, and younger generations.

Although studies suggest that empowerment through local participation in predator hunts may be an important aspect of reaching a goal of social acceptance (Heberlein & Ericsson Reference Heberlein and Ericsson2008; Kaltenborn et al. Reference Kaltenborn, Andersen and Linnell2013), Wisconsin did not experience these positive effects following the first wolf hunt. The WDNR has since administered two successive wolf hunting and trapping seasons, but the effects on tolerance are unknown. In December 2014, the federal government relisted wolves as an endangered species in Wisconsin and neighbouring states (US District Court for the District of Columbia 2014), effectively discontinuing the wolf hunt and lethal control. Federal legislators have challenged this relisting already. As future wolf policy is debated, caution is warranted when justifying public wolf hunts to raise tolerance for this controversial species.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and University of Wisconsin-Madison for their support. Thank you to M. Rabenhorst (Figure 1), C. Williamson, C. Browne-Nuñez, V. Shelley and the Carnivore Coexistence Laboratory, D. MacFarland, T. Heberlein, K. Martin, E. Jones, A. Wydeven, R. Jurewicz, J. Peugh, P. David, J. Naughton, D. Scheufele, T. Mohan, R. Laufenberg, D. Laufenberg, K. Ankenbaur, N. Goldstein, M. Robinson, Wisconsin Bear Hunters Association, and Wisconsin Cattlemen's Association.

This work was partially supported by UW-Extension and the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences at UW-Madison, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service (AT, grant number, F12AP00839). This research received no other specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S037689291500017X.