In the final months of 1933, as the amendment to repeal Prohibition came within striking distance of ratification, wine merchants and winemakers around the world greeted Prohibition’s imminent demise with great expectations. Anticipating frenzied buying, stimulated by pent-up demand, entrepreneurs rushed into the wine business, swelling the ranks of California vintners from 130 still in operation at the close of Prohibition to over 800. Footnote 1 Across the Atlantic, French winemakers, plagued by oversupply, reveled in the possibility that American consumers, with their “supposed capacity for unlimited alcoholic consumption,” might rejuvenate “the failing French wine industry.” Footnote 2 In the United States, drinking reformers—the new champions of moderation—also had high hopes for wine. Eager to wean Americans from their liquor-loving ways, some wine enthusiasts hoped that Americans’ love of novelty would spark a wine boom and transform the United States into a republic of civilized wine drinkers. Footnote 3 As it happened, however, Esquire columnist Frederick Van Ryn came much closer to the mark when he predicted that wine would struggle to find a mass market. “A generation accustomed to the one-hundred-and-one-gun salute of a battery of cocktails before dinner,” Van Ryn prognosticated, would realize that “hard liquors do not mix with their softer colleagues” and would quickly abandon the effort to master the “fine art” of drinking wine. Footnote 4 The title of Van Ryn’s essay—“There’s No Repealing Tastes”—encapsulated the depths of wine’s mass-marketing challenge.

For nearly three decades after the repeal of Prohibition, getting American consumers to buy American wines proved an uphill climb. Instead of greeting wine as an enticing novelty, many white Americans regarded wine as a stigmatized commodity—a foreign beverage consumed either by wealthy aristocrats or untutored immigrants. As Wines and Vines explained, Americans typically associated wine with “luxurious living—or something that people from the old country mistakenly believed ‘good for the blood and good for the appetite’ . . . One was beyond the purse and perhaps knowledge of the Smith and Jones families, the other disdained with slight contempt.” Footnote 5 American preferences for sweet and potent wines over table wines enjoyed with meals compounded the challenge of creating a post-Prohibition tradition of wining and dining. When sales of table wines (wines with an alcohol content of 12 percent to 14 percent by volume) finally surpassed fortified dessert wines (wines with an alcohol content of 18 percent to 20 percent) in 1967, wine marketers hailed that shift in consumer preferences as the beginnings of the “wine revolution.” Over the next decade, table wine consumption in the United States increased three fold, from 87 million gallons to 261 millions gallons, while dessert wines fell from 79 million to 60.5 million gallons. Footnote 6

This article seeks to complicate our understanding of the wine revolution by exploring how wine merchandisers planted the seeds for the dramatic shift toward table wines in the 1940s and 1950s. Traditionally, historians and wine market analysts have attributed the wine revolution to rising affluence and foreign travel, to the demographic surge of baby boomers reaching drinking age, and to a middle-class culture of culinary adventurism fostered by growing interest in ethnic foods and Julia Child’s 1961 cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, and TV show. Above all, such interpretations invariably stress the “quality revolution”—fostered by the planting of superior grape varieties and the interventions of University of California enologists—as the main driver of changing consumer tastes. Footnote 7 Historians have diverged more sharply over the precise social underpinnings of the wine revolution. Citing a 1972 Arthur D. Little study, James Lapsley interpreted the shift to table wine partly as a “rejection of the ‘gray flannel suit’ values of 1950s corporate America” and the “raucous ‘cocktail party.’” Footnote 8 Somewhat similarly, Donna Gabaccia argued that the converging tastes of hippies and yuppies paved wine’s path to the mainstream. Footnote 9 David Strauss credited a different cultural avant-garde, led by Gourmet magazine and various wine and food societies, for “setting the table for Julia Child” and the wine revolution. Footnote 10

While such interpretations capture some of the social and cultural dynamics that fueled the wine revolution, they focus too narrowly on the groups that resided on the fringes and the upper ends of the middle class—the bohemians, hippies, gourmets, and upper-middle-class professionals—and miss how wine merchandisers and mass marketers steered a path between the highbrow sophisticates and the countercultural rebels to vie for a broader middle-class demographic. To fully understand the process by which wine came to the dining table, it is important to analyze the 1940s and 1950s, when California wine promoters pinned their hopes on a different group of consumers—neither bohemians nor gourmets. Wine promoters’ earlier endeavors to build a mass market have garnered less scholarly attention partly because, at first glance, the modest 8 percent growth in per capita wine consumption in the 1950s seemed to affirm the limited effectiveness of promoters’ campaigns. However, when adjusted to register consumption solely by adults over the age of twenty-one—a crucial mathematical correction in the midst of a baby boom—the statistics tell a different story. From 1948 through 1960, adult consumption of all wine types increased by 17 percent (from 1.28 gallons to 1.5 gallons per capita) while adult consumption of table wines jumped an impressive 69 percent (from 0.29 to 0.49 gallons per adult). Consumption of table wine continued to accelerate, reaching 0.75 gallons per capita in 1967 and double that again by 1975. Footnote 11

The initial postwar surge in wine consumption coincided with the California wine industry’s collectively funded nationwide campaign to divest wine of its associations with foreignness and earn wine a welcome place in restaurants and homes. Initially, wine promoters—many of them self-styled drinking etiquette counselors and leaders of the newly formed gourmet dining societies—attempted to enhance wine’s respectability by instructing readers about proper serving glasses and serving temperatures and proper food and wine pairings. When these highbrow approaches backfired in the mid- to late 1930s, wine marketers and merchandisers struck a more populist tone, urging restaurateurs to set their sights not on the upper crust who ordered Chateaubriand, but on the average customers who ordered “Shrimp Cocktail or Tomato Juice, … Steak and French Fried Potatoes—Chicken or Turkey—a piece of pie and a cup of coffee.” Footnote 12 By the early 1940s, California wine promoters had come to view wine marketing as a kind of Americanization campaign aimed at integrating wine within familiar rituals of dining out and home entertaining. They understood well what anthropologists have long known: that acquiring a taste for unfamiliar foods—especially ones with foreign origins—often involves a process of refashioning their uses, forms, and meanings in ways that echo and subtly modify preexisting food and dining practices. As recent scholarship attests, in fact, acquiring a taste for foreign foods may not even require the experience of sensual pleasure if the social pleasures associated with certain foods and beverages override their perceived sensual deficits. Foods of foreign origin like McDonald’s hamburgers in Russia and China eventually become the food pleasures of local choice as consumers—egged on by savvy marketing and merchandising—learn to adapt such foods to their own needs, values, and social rituals. Footnote 13

This article aims to deepen our understanding of how wine promoters’ marketing missteps and course corrections eventually enabled postwar American consumers to endow wine with new meanings. A commodity previously marked as either too highbrow or too lowbrow, wine gradually lost its foreignness as merchandisers learned to sell the glamour of wine without the demands of connoisseurship and adapted wine to the rituals and norms of American cocktail culture. Instead of setting their sights on urban sophisticates, the Wine Advisory Board, which oversaw the California wine industry’s collective advertising campaign, aimed for young married couples and budget-conscious new homeowners—the most recent entrants into the middle class. Footnote 14 Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, wine marketers worked to both surmount and accommodate existing alcoholic beverage preferences, sometimes by casting wine as a base for cocktails and at other times by casting wine as the budget-friendly alternative to them. They advanced and built on postwar trends that integrated wine in home cooking and casual home entertaining—with the promise of delivering pizzazz without the fuss. These more populist marketing appeals, I argue, sowed the seeds of the “wine revolution” not in bohemian enclaves and gourmet dining societies but in middle-class suburbia, where wine found its way to the American dinner table via the cocktail glass, the casserole dish, and the backyard barbecue.

Obstacles to the Development of a Wine Culture in the United States

Although the United States had never boasted a strong wine-drinking tradition, the legacies of Prohibition compounded the difficulty of creating a mass market for American wine. Only a few veteran winemakers had continued to practice their craft by making sacramental wines during Prohibition and the resultant deterioration of winemaking expertise and production facilities hampered the industry’s reconstruction. The Volstead Act, the enabling legislation for national Prohibition, had also set in motion a series of business calculations that degraded the quality of wine for decades after Prohibition’s demise. The act’s provision permitting the manufacture of “nonintoxicating cider and fruit juices” for home use encouraged vineyardists to plant grape varieties that could withstand the rigors of a long transcontinental journey to Chicago, New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, where immigrant and ethnic buyers eagerly sought grapes for home winemaking. The favored grape varieties were not the fine Riesling, Pinot, and Cabernet grapes that produced good table wines, but hardy, thick-skinned shipping grapes like Alicante Bouschet and table and raisin grapes like Muscat and Malaga, which produced inferior wine. Carignane and Zinfandel (both red wine grapes) sometimes found their way into buyers’ trucks, but the grape that won home winemakers’ hearts and soon took over large swaths of California’s San Joaquin Valley and Livermore Valley was the Alicante Bouschet, a grape so rich in color that some winemakers who added sugar and water to the mass remaining after the first pressing could reportedly get 600 gallons to 700 gallons of red wine from a single ton—significantly more than the 150 gallons yielded from ordinary winemaking methods. Footnote 15

The Volstead Act’s fermented fruit juice exemption set in motion a series of business calculations that degraded the quality of wine for decades after Prohibition’s demise. When the shipping grapes and table and raisin grapes favored by East Coast buyers began fetching outrageously high prices, speculators set off a frenzy of vineyard planting in California and across the nation. Footnote 16 Growers dedicated the new acreage to inferior table and raisin grapes and proved reluctant after Prohibition to replant superior wine grapes because the fine varieties yielded less per acre and cost more to cultivate. Throughout the 1930s, roughly equal portions of wine grapes and table and raisin grapes landed in the crushers, assuring, at best, mediocre wines. Footnote 17

Although the Volstead Act’s fermented fruit juice exemption helped to make wine more popular during Prohibition than before, the practice of home winemaking and the entry of highly sweet sacramental wine into bootleg channels created several long-term headaches for the resurrected wine industry. Prohibition accustomed American consumers to wines that had more residual sugar and alcohol (18 percent to 20 percent by volume) than table wine, and these tastes proved remarkably resistant to change. Prohibition-era home winemakers encouraged this trend away from lower-alcohol table wines by adding sugar during fermentation to boost potency and volume. Sweet wines like Angelica, Muscat, and Tokay—all fortified to 18 percent alcohol—also dominated the sacramental wine market, which, thanks to weak oversight, stretched well beyond the perimeters of Catholic churches and Jewish synagogues. Footnote 18 Popularly derided as “basement rotgut,” “red ink,” and “dago red,” the wine that flowed into the black market became inextricably linked in the American imagination with bootleggers, immigrants, and skid row derelicts. Wine marketers viewed wine as a particularly tough sell for the younger generation, which had consumed large quantities of bootleg “red ink”—“not by choice but because it was cheap.” Assuming the quality of bootleg wine to be typical wine, the younger generation “would not think of buying wine,” H. F. Stoll Jr. predicted, “now that legal beer and hard liquor [could] be bought.” Footnote 19

Prohibition also dealt a huge blow to the tradition of dining with wine. Although some cosmopolitans who ventured into any Little Italy in search of “booze” developed a fondness for spaghetti and the red wine they sipped surreptitiously from coffee cups, many of the higher-echelon restaurants either shuttered their doors or limped along in the absence of alcohol revenues. Footnote 20 Prohibition further eroded wine’s place in the middle-class home “by making cooking with wine taboo in public and expensive in private.” “The recipes for French dishes which survived in middle-class cookbooks,” historian Harvey Levenstein has written, “became charades of their former selves: wineless ‘Chicken Bordelaise,’ and Chicken Marengo which was merely chicken in tomato sauce.” Footnote 21 Jessica McLachlin, a staff writer for the Wine Institute, a trade association representing California’s vintners, lamented in 1934 that a “lost generation” had “forgotten the delights of dining with wine.” Footnote 22

Tastemakers eager to enhance wine’s respectability also dampened early enthusiasm for wine. In 1933 and 1934, self-styled drinking reformers churned out dozens of drinking guidebooks offering to instruct readers on the importance of correct wine and food pairings and the proper etiquette of serving different types of alcoholic beverages in the home. Addressed primarily to middle-class women, the guidebooks amplified women’s importance as the guardians of temperate pleasure-seeking by transforming drinking from a simple pleasure into a complicated ritual of gentility, fraught with potential for “grievous error.” Footnote 23 Press coverage of the international Wine and Food Society chapters that had sprouted in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, New Orleans, Chicago, and Boston further damaged wine’s prospects of developing mass-market appeal. By the mid- to late 1930s, just as the emerging “gourmet movement” had barely gotten off the ground, a full-scale revolt against pretentious wine etiquette and wine connoisseurship was already underway. Unflattering reports in city newspapers mocked the elitism and ostentation of Wine and Food Society dinners, with their formal dress codes; restricted membership (no women and ethnic minorities allowed); and elaborate multicourse meals, featuring different wines (usually French) with each course. Staged in the midst of widespread hunger during the Great Depression, gourmet dining society events struck reporters as sad testaments to the excesses of out-of-touch high society elites. Footnote 24

The restaurant trade press was just as scornful. “Wine has been the subject of so much hokum since repeal that all but the hardier souls have been frightened away,” noted Frederick Anderson. “If I believed all I have read I would think I must have five wines with every meal” and “that unless I could remember the best years … I should not dare to order claret.” Footnote 25 Wine sales at Childs Restaurants, a popular middle-class chain, fell after an initial post-repeal boom owing partly to low wine quality, but the head of Childs’ liquor department also blamed wine-dealers for making “the serving of wine too complicated and elaborate for hostesses.” Footnote 26

Some promoters of American wines tried to turn the Depression-era backlash against pretentious wine rituals to their advantage by casting connoisseurs as “un-American” snobs who favored expensive European wines over their humbler American counterparts. Although imported wines never constituted more than 5 percent of the U.S. wine market in the 1930s, thanks to a hefty protective tariff of $1.25 on each gallon, imported wines, especially those from France and Italy, enjoyed far greater prominence on upscale restaurant menus than American wines. Footnote 27 In a column for Restaurant Management, Mrs. J. Molera, the Edgewater Beach Hotel’s wine manager, called on waitstaff to proudly recommend American wines, which admittedly were not “GREAT wines,” but were nonetheless better suited to the simple fare of chicken or “Steak and French Fried Potatoes” typically found in American restaurants. Molera’s column aimed to make wine drinking a test of patriotic loyalty and populist virtue: “WHEN YOU DRINK AMERICAN YOU BUY AMERICAN.” To insist on drinking only great imported wines, Molera contended, “would be like telling people that they are ignorant and commonplace if they enjoy a simple melody or ballad—and that they should hear only the works of great composers.” Footnote 28 Consumers who answered Molera’s call to “buy American” out of patriotic duty soon found themselves doing so by necessity, thanks to the sharp decline of European wine imports during World War II.

Even when the channels of trade reopened after the war, however, the threat presented by imported European wines paled next to the challenge of surmounting the biggest hurdle to American wine’s mass-market appeal: Americans’ strong preference for whiskey and spirits-based cocktails. Wine promoters might have blamed sluggish wine sales on the Depression, but economic misfortune had not diminished consumer demand for spirits. In 1937, in the midst of a recessionary downturn, Childs Restaurants reported a 15 percent increase in liquor sales. Footnote 29 Even among groups that wine promoters imagined as their most promising prospects, the preference for liquor was overwhelming. In its quest to become known as a “sherry house,” the Hotel Carlyle in New York City recommended fine sherries, particularly to women guests, but garnered few takers. “Even the women still seem to prefer the more potent drinks,” manager Harold Bock conceded. “The dry Martini is our best seller, … closely followed by Scotch highballs. Old Fashioneds are a close third.” Footnote 30 Consumer preferences for liquor over wine continued well into the postwar years. In 1949, Restaurant Management’s beverage columnist Bert Dale observed that customers really wanted a drink that packed a punch: “Don’t fool yourself that most people drink for any reason other than that they want to feel the result.” Footnote 31

Americans’ strong preference for distilled spirits also dampened restaurateurs’ enthusiasm for reviving a tradition of wining and dining. Slow to embrace the notion that wine could generate profits, many restaurateurs preferred the immediate higher profits on liquor sales to the less certain long-term gains from teaching diners to enjoy wine with meals. As Otto Baumgarten, manager of the Restaurant Crillon in New York City, observed, “Hard liquors show a better percentage than wines. The less wine and the more hard liquor sold, the better profits the wine steward can show.” Footnote 32 Even if hotels and restaurants doubled wine’s wholesale price, wine profits still paled next to what a good bartender could squeeze out of cocktails. “A $2.50 bottle of gin and a few pennies’ worth of vermouth,” the Atlantic Monthly explained, could “be diluted into $15 worth of Martinis.” Footnote 33 Other restaurateurs heralded predinner cocktails for stimulating a taste for luxury and greater spending in the dining room. According to D. T. Touhig, head of Childs liquor department, “a beef stew might satisfy a customer who hadn’t ordered a cocktail,” but “only a charcoal-broiled steak on a dinner complete from soup to demitasse will satisfy a customer who has whetted his appetite with a Manhattan or a Martini.” Footnote 34

The culinary conservatism of many restaurant menus and restaurant-goers also created obstacles to robust restaurant wine sales. While wine could have harmonized well with typical American restaurant dishes—broiled steak and lamb chops, roast chicken, fries and mashed potatoes, canned peas or frozen vegetables—Americans contentedly paired the “tasteless, colorless” fare, as novelist John Steinbeck described it, with coffee and soda. Footnote 35 Margrit Biever Mondavi recalled that when she and her first husband, a military man, were stationed in Spokane, Washington, during the 1950s: “Everybody started with a cocktail for the first course and then drank mugs of coffee with the rest of the dinner. (There was even a judging of which coffee went best with which pork chop!).” Footnote 36 Apart from restaurant-goers in San Francisco, New York, New Orleans, and other great food cities that boasted Wine and Food Societies, “interest in fine dining” after repeal, Levenstein observes, faded, even among the upper class. Footnote 37 Increasingly, “the titillation [of dining out] came not from trying new and different foods but from new and exotic locales.” Footnote 38

American wine promoters faced numerous obstacles in their quest to make wining and dining a key component of how middle-class Americans defined and experienced the good life. The consumer backlash against low wine quality and fussy wine etiquette, the greater allure of liquor and liquor profits, and an American restaurant culture that prized cleanliness and ambience over food quality and exotic tastes all circumscribed wine’s path to mainstream acceptance. As a commodity heavily marked by its foreignness, wine had also yet to overcome its image as the beverage favored by skid row bums and immigrants. By the late 1930s, as the prospect of creating a republic of wine drinkers looked increasingly dim, wine merchandisers began to identify new cultural pathways—initially laid down by American cocktail culture—to make wine more translatable and more enticing to the masses.

Wine Cocktails: Charting the Path of Least Resistance

Despite middle-class consumers’ pride in their cosmopolitan tastes, Americans’ “culinary horizons” only expanded so far in the mid-twentieth century. Footnote 39 When middle-class diners patronized ethnic restaurants, they still expected them “to provide familiar American foods alongside exotic new cuisines.” Footnote 40 Moreover, Americans, like most other peoples, rarely adopted new food tastes wholesale. When Americans embraced foreign foods, they did so in modified forms, often “unrecognizable … to people from the purported countries of origin.” Footnote 41 Americanized versions typically toned down the spicing, added the new flavors “as ‘sauces’ for their still-familiar ‘core’ foods,” and “domesticated [the new foods] with familiar markers such as ketchup or mustard.” Footnote 42 Such modifications expressed the competing impulses that guide food choices—the desire for variety and the exotic, on the one hand, and the desire “for the reassuringly familiar,” on the other. Footnote 43 What native-born American restaurant-goers wanted, historian Audrey Russek has written, was “a kind of packaged authenticity, a cultural reproduction that was different enough to feel foreign, but familiar enough to be non-threatening.” Footnote 44

Matters of status and distinction also determine how different cultures and classes decide which new food tastes are worthy of adopting and how they should be incorporated into established food traditions. Dominant groups have overcome their wariness of foods associated with subordinate groups by incorporating the new foods into higher-status dishes and consuming them in elite settings. Curry from India, for example, lost its negative colonial associations when Britons in the metropole added it to high-status foods such as beef, shrimp, and lobster. Footnote 45 To win mass appeal, wine needed to undergo a similar makeover. Wine promoters needed to divorce the beverage from its negative associations with foreignness—from both its lower-class associations with immigrants and its upper-class associations with fussy etiquette. Promoters also needed to appeal to Americans’ competing yearnings for the exotic and the familiar. In cocktails, they found a promising answer to their marketing dilemma.

By the late 1930s and early 1940s, some wine promoters concluded that wine stood a better chance of gaining mass-market traction as a cocktail than as a mealtime beverage because such merchandising could trade on Americans’ greater familiarity with cocktails as well as the cocktail’s greater prestige within the hierarchy of alcoholic beverages. During World War II, when California vintners launched their Wine Drive for America, a collectively funded marketing campaign, the industry continued to promote wine as a mealtime beverage, but they also touted wine’s versatility in cooking and entertaining. The Wine Advisory Board, a fifteen-member panel appointed by California’s director of agriculture, oversaw the campaign and enlisted the Wine Institute and the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency to develop ads and merchandising aids. The initial outlay of $2 million was quite modest next to the $7.5 million brewers spent on advertising in 1939 and the $16.5 million spent by distillers, but it funded advertisements on billboards and in monthly magazines, educational pamphlets, menu stickers, restaurant table cards, and recipe booklets. Footnote 46 The Wine Advisory Board produced booklets on serving wine and cooking with wine, and it furnished recipes for summer wine coolers (made with wine and seltzer water) and hot spiced winter wine punches.

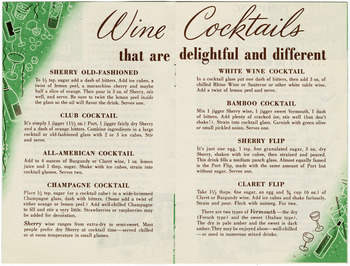

The idea of wine cocktails attempted to answer drinkers’ paradoxical yearnings for novelty and familiarity by situating wine in the more customary setting of the cocktail hour. The simplest wine cocktail—the wine spritzer made with wine and seltzer or wine and ginger ale—promised ease of preparation and the familiar sensations of effervescence that many Americans enjoyed in their soft drinks and highballs. Consumers who desired more exotic cocktail fare, something that required a bit more cocktail-making prowess, could turn to Wine for Party Time, a Wine Advisory Board pamphlet produced in the 1950s that provided recipes for a host of heavily sugared wine punches and mixed drinks made with every type of wine: sherry, port, champagne, red, and white. The mixed drinks preserved the rituals of cocktail making, usually calling for a dash of bitters, a teaspoon of sugar, careful chilling and straining, and precise instructions on whether the drink should be shaken or stirred. No recipe was complete without the addition of a garnish or aromatic; the lemon twists, maraschino cherries, green olives, and pickled onions that made their way into classic cocktail recipes found their way into the Wine Advisory Board’s version of a Sherry Old-Fashioned, Club Cocktail, and All-American Cocktail. Wine for Party Time (Figure 1) ever so gently attempted to steer drinkers to wines in their purer form—“perhaps you have already discovered that many wines make perfect party drinks just as they come from the bottle”—but its main mission was clear: to entice wine-resistant consumers to sample wine and perhaps learn to like it in its more sweetened cocktail form (Figure 2). Footnote 47

Figure 1 Wine Advisory Board pamphlet, c.1950s.

Note: Courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Figure 2 Wine Advisory Board pamphlet, c.1950s.

Note: Courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

The Wine Advisory Board’s wine cocktails strategy aimed not just to court new consumers but also to appease wine producers who did the bulk of their business in fortified sweet wines like sherry and port. To maintain broad support for the collectively funded Wine Advisory Board campaign, which levied mandatory fees on all California wineries—after two-thirds assented to the fees—the Wine Advisory Board could not afford to alienate key segments of the industry by solely promoting wine as a mealtime beverage. The large Central Valley wineries and growers, whose livelihoods depended on a thriving market for fortified sweet wines, had periodically attempted to thwart renewal of the Wine Advisory Board because they thought its promotion of table wine was wasting their money. Footnote 48 The persistent plugging of sweet wines in Wine for Party Time aimed to secure the interest of consumers and the continued loyalty of skittish sweet wine producers.

The restaurant and hospitality trades also recognized the upside of grafting wine onto cocktail culture. During the postwar years, a good deal of the enthusiasm for wine cocktails among restaurateurs and barkeeps was purely pragmatic. In states that outlawed on-premise liquor sales but permitted on-premise wine and beer sales, wine cocktails made a virtue of necessity and became an increasingly popular alternative to the traditional mixed drink. In such states, cocktails made with gin, whiskey, or rum could be consumed in the privacy of one’s home with liquor purchased from the state-run liquor store (or the local moonshiner) but not in a restaurant, bar, or tavern. The Hotel Dempsey, in Macon, Georgia, surmounted that regulatory obstacle by offering patrons wine cocktails made with 2.5 ounces of wine (customers’ choice of type), half a barspoon of sugar, and a quarter-ounce of lemon juice, topped off with shaved ice and sparkling water. Served in an eight-ounce highball, the Hotel Dempsey’s wineades accounted for half of the hotel’s beverage business. Footnote 49

When restaurateurs grafted wine onto cocktail culture, they not only recast wineades and wine spritzers as yet another variation of the mixed drink but they also adapted the rituals of serving wine to the rituals of serving cocktails. Some restaurants stimulated mixed drink sales by deploying mobile portable bars, which allowed “waitstaff to mix drinks tableside,” giving “table patrons every advantage of a bar stool.” Footnote 50 The Robin Hood Room at the Hotel Dyckman in Minneapolis repurposed the portable bar as a portable wine table, from which waiters would offer patrons a complimentary glass of wine. When the waiters later returned with the rolling wine table, wine sales usually followed. Footnote 51 The portable wine table mimicked the experience of ordering from a bar while also helping patrons to conceive of wine as a beverage to enjoy at the table with meals (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Portable wine bar, Hotel Dyckman, Minneapolis, 1949.

In the short run, borrowing the rituals and naming practices of cocktail culture to help translate wine to the masses probably did more to reinforce Americans’ attachment to cocktails than it did to encourage wining and dining as a temperate alternative to it. Restaurateurs profited most by allowing wine to ride the cocktail’s coattails into the dining room. Some even designed menus and wine tips specifically with the cocktail-drinking set in mind. Frederick Anderson’s “Wining and Dining” column in Restaurant Management recommended that menus offer wine recommendations based on the types of cocktails patrons ordered before dinner. Diners who had already consumed “several cocktails,” Anderson noted, would greatly appreciate a note on the menu that suggested, “If you have had an Old-Fashioned you’ll enjoy a bottle of Moselle with dinner. ... This could be carried further with suggestions for wines that are friendly to Martinis and Manhattans.” Although Anderson conceived such menu notes as “merely another way of bringing wine to people’s attention,” Footnote 52 they also underscored wine’s subordinate status within the hierarchy of alcoholic beverages. In Anderson’s view, wine best served restaurants’ bottom line as an adjunct to cocktails. Rather than bother patrons with tips on wine and food pairings, Anderson offered tips on which wines paired best with which liquors. Footnote 53

Neither the gourmet dining societies nor the drinking reformers who hoped that a culture of moderate wine drinking would eventually displace cocktail culture could have been pleased that the cocktail paved the new cultural pathway to wine. In fact, several gourmet dining societies prohibited cocktails before dinner because, as one member put it, gourmets were “high-minded temperate advocates of haute cuisine as the highest expression of civilization and culture.” Footnote 54 Increasingly, however, the American tradition of wining and dining came to mean cocktails before wines with dinner. Even Gourmet magazine, which relied heavily on whiskey advertising revenues, “reshaped gourmet dining to accommodate Americans’ liking for the cocktail” and “publish[ed] equal numbers of articles on wine and cocktails.” Footnote 55 Tourist guidebooks also affirmed the marriage of wine and cocktails in fine dining establishments. In her 1939 guide to New York, written for the “woman vacationist,” Marjorie Hillis mentioned wine only once in the chapter titled “Cocktails, Dinner, and No Escort” when describing a lavish “gourmet” meal enjoyed by two female diners at the French restaurant Lafayette. Starting with dry Martinis, “unsurpassed for stimulating the appetite,” the diners next ate clear consommé, with a dry sherry; then for the main course enjoyed grilled pompano, new potatoes, and peas, with a Pouilly Fuisse 1929; followed by salad and cheese; and finally Pots au Crème for dessert, with coffee. Footnote 56 Stretched over a leisurely meal, the dry Martini, glass of sherry, and bottle of wine for two may not have left the diners three sheets to the wind, but it certainly put the culture of moderation to the test.

Suburban Wine Drinkers and the California Way of Living

As a mass-marketing strategy, the idea of promoting wine as a base for cocktails offered much in the way of short-term stimulus but little promise of long-terms gains. The novel, yet reassuringly familiar, wine cocktails undoubtedly encouraged more Americans to sample wine and, for some consumers, they may have provided a stepping-stone to enjoying wine with meals. Wine cocktails, however, stood little chance of acquiring the social cachet of Martinis, Manhattans, and whiskey highballs, and they created a fairly flimsy base from which to build a mass market for table wine. Not only did dessert wines and wine cocktails have numerous beverage competitors, but marketing experts also doubted that drinkers who gravitated to the sweet wines and sweet wine cocktails would ever become loyal table wine consumers. Such drinkers were simply too easily lured to other beverages by the shifting dictates of drinking fashions. The industry’s best hope for future growth and stability, marketing experts surmised, instead lay in cultivating new generations of table wine drinkers who enjoyed wine with dinner, and once so converted to wine’s mealtime pleasures, found no adequate substitutes in other alcoholic beverages. Footnote 57 To secure a loyal base of continual users, wine promoters still had to entice consumers to take their seats around the dinner table.

During World War II, Wine Advisory Board ads promoted wine as the mealtime beverage that could cheer war-weary souls and the secret ingredient that could rescue drab wartime meals and turn low ration-point variety meats into company fare. Although the war did not produce the wine boom vintners had hoped for, it laid the groundwork for postwar transformations in hospitality and food culture. Suburbanization and mass home ownership in the late 1940s and early 1950s gradually brought the prospective wine consumer into sharper focus. In 1949, only 21 percent of Americans drank wine every week, 17 percent abstained for religious and moral reasons, and the remaining 62 percent—the main targets of the Wine Advisory Board’s campaign—included Americans who drank wine a paltry three times a year (34 percent) and those who drank no wine at all but consumed other types of alcoholic beverages (28 percent). Footnote 58 J. Walter Thompson, the advertising agency that handled the Wine Advisory Board account, identified wine’s most promising prospects among the recent entrants into the middle class—the “young marrieds” with new families “whose living patterns and habits are only now taking shape.” Footnote 59 These were the young families who settled the rapidly expanding suburbs, populated by ethnically diverse but racially exclusive whites. Some of these “young marrieds” would have included descendants of Southern and Eastern European immigrants who regularly consumed wine with meals, but these were not among the 62 percent targeted by the campaign. J. Walter Thompson trained its sights on households that enjoyed comfortable but modest incomes—households headed by men making their way up the corporate ladder, just starting a small business or professional career, or holding down a well-paying blue-collar job. Many new suburbanites left behind extended families in the city, making these “young marrieds” both more open to and more anxious about the new forms of sociability and the new measures of social distinction that governed suburbia. It was precisely this mix of openness and anxious striving that, in some marketers’ estimation, made the newly middle class such good prospects for wine.

The postwar baby boom and the mass migration to the suburbs unsettled patterns of leisure and drinking by making the home the primary site of alcohol consumption for much of the middle class. As suburbanites spent more of their disposable income on home appliances, second cars, and their growing families, the allure of urban nightlife gave way to the home-centered appeals of television and backyard barbeques. Television transferred the primary site for spectator amusements “from the public space of the movie theater,” sports arena, and concert stage “to the private space of the home,” allowing viewers to experience the thrills of urban culture without its hassles or dangers. Footnote 60 Suburbanization also relocated the “cocktail hour” from the public bar and lounge to the kitchen, living room, and patio, where many husbands and wives enjoyed the ritual of drinks before dinner. The growing importance of alcohol to home-centered recreation meant that suburbanites had to master the art of preparing cocktails and the social proprieties of serving different types of alcoholic beverages to affirm their membership in the middle class. Consumers’ interest in the question of what drinks to serve was not new—advertisers and tastemakers had been supplying answers and suggestions since the repeal of Prohibition—but the changing postwar landscape amplified that interest as the primacy of home-centered recreation turned more and more Americans into their own private bartenders. Footnote 61

Although the surviving J. Walter Thompson account files for the Wine Advisory Board provide little in the way of hard market research data, related market research studies from the postwar era identified the “recent middle class” as a group prone to status anxiety and an ideal target for advertising messages that promised to assuage their social insecurities and bolster their cultural capital. Footnote 62 Ernest Dichter, the pioneering market researcher who used Freudian psychoanalytic concepts to understand consumer behavior, conducted dozens of motivational research studies for alcoholic beverage producers during the 1950s. Based on in-depth interviews with consumers, these studies included a handful of reports for companies that sold table wine and sherry. Read together, Dichter’s market research on various alcoholic beverages provides a revealing glimpse into the anxieties and aspirations that guided beverage choices, especially among middle-class consumers. Dichter’s study for Heublein’s prepared cocktail mixes, for example, suggested that insecurity about serving cocktails rated about as high among members of the recent middle class, as did insecurity about selecting the right wine for the right occasion. As one respondent shared, “I may not be an experienced cocktail maker, but I’m experienced in drinking them, and I know a bad one when I taste it. … If I don’t make cocktails well, what is there to show off with in my drinks?” Footnote 63 Here was a drinker who possessed enough cultural capital to know the difference between a good cocktail and a bad one but not quite enough to carry off the host’s drink-making duties with confidence and panache.

Wine stimulated even more pervasive fears of incompetence because few consumers had much experience with wine and many assumed that considerable expertise was required to enjoy wine. Dichter theorized that many Americans rejected wine drinking because their ignorance about wine amplified their social insecurities and prejudice against the types of people they presumed to be wine drinkers. Footnote 64 In Dichter’s Reference Dichter1952 studies for Cresta Blanca sherry, based on interviews with San Franciscans, New Yorkers, and Los Angelinos, many respondents could not envision themselves drinking wine because they perceived wine drinkers as people who occupied “either extreme of the social ladder.” Whether caricatured by survey respondents as “effeminate men,” “pseudo-sophisticates,” wealthy “aristocrats,” or “poor” unfortunates who drank wine “indiscriminately,” wine drinkers, in one way or another, stood outside the cultural mainstream of American life. Footnote 65 Although Dichter’s test subjects associated table wine drinkers most strongly with sophisticated elites, many of them struggled to reconcile such perceptions with the reality that working-class Europeans and peasants also preferred dry wines. “At first thought,” Dichter wrote, “it would seem that those wines which are identified with untutored peasants could not possibly be frightening to consumers in their choice of wine. It is, though, the very social distance between the middle-classed American and the European peasant which makes dry wines seem foreign and incomprehensible.” Footnote 66 Wine’s foreignness did not invariably elicit hostile attitudes toward wine drinkers. As one respondent observed, “I have very romantic ideas about what kind of people drink wine. Gay, Bohemian, foreign people. I mean that to be complimentary. I’m envious, but it isn’t like me.” Footnote 67

The Wine Advisory Board had long recognized the paradoxical nature of wine’s principle marketing problem: consumers perceived wine as simultaneously too highbrow and too lowbrow. Dichter’s findings, however, suggested that tastemakers and etiquette mavens had undercut wine’s mass-market appeal by overplaying wine’s respectability (the perceived remedy to wine’s reputation as “dago red” and the beverage of skid row). Americans, he wrote, “have been so oversold on the foreign nature of wine and the foreign customs … which govern its serving, that they have given up the attempt to develop their own kind of enjoyment of wine.” Footnote 68 If the wine industry wanted to sell table wines to the masses, Dichter concluded, they would have to destroy the “connoisseur ‘stigma’” and reassure consumers “that they do not have to learn an elaborate protocol before they may serve and enjoy dry wines.” Footnote 69

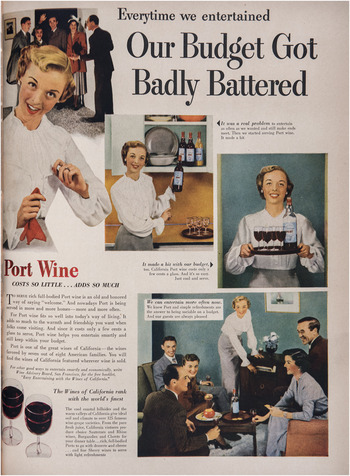

The Wine Advisory Board’s advertising campaign in the late 1940s and early 1950s appeared to share Dichter’s assessments of wine’s biggest marketing problems and marketing opportunities. It struck a decisively populist note in going after young married couples and the emergent middle-class suburbanites—the very groups that, as Dichter would have it, yearned for affirmation of their class status but feared public exposure of their wine ignorance and cocktail-making incompetence. A series of ads from 1949 made wine approachable by stressing its affordability—a message well pitched to young families with mortgages to pay and more mouths to feed. The ads presented California port, sherry, and burgundy as wines for budget-conscious housewives who wanted to entertain in style without busting their budget to maintain a well-stocked liquor cabinet (Figure 4). In one ad, a couple who once “felt like hiding” when the doorbell rang “because having company just ruined our budget,” now happily welcomed guests with California sherry—a wine that “costs so little” but “adds so much.” Footnote 70 Served with “something simple—appetizers, sandwiches, cakes or cookies,” sherry was a “real hit” with guests, according to the ad, and a budget saver to boot. Footnote 71 The Wine Advisory Board ads for port, sherry, and burgundy made an implicit play for both the anxious cocktail-maker and the anxious wine server by assuring hosts and hostesses that wines required no extra fuss—“just cool and serve.” Footnote 72 The ads attempted to persuade thrift-conscious consumers, who likely considered dinner with wine the preserve of the wealthy, that savvy homemakers—ones clever enough to choose “a cheaper cut of meat” and use the savings to buy a “perfectly wonderful” California burgundy—could invite guests to a festive dinner without fear of “breaking [the family] budget.” Footnote 73

Figure 4 Wine Advisory Board ad, Life Magazine, 1949.

Such ads deftly incorporated wine into the social world of the newly middle class, a group that continued to practice thriftiness—a legacy of Depression-era and wartime frugality—but also enjoyed extending hospitality to friends, neighbors, and family. Associating wine with such solid middle-class virtues—thrift, good hospitality, and neighborliness—helped to strip wine of its aristocratic stigma and refashion wine drinking as an emblem of the middle-class good life. The next step was to persuade consumers that this seemingly foreign beverage belonged as much to the American food landscape as did hamburgers, roast beef, and baked beans. In the early 1950s, the Wine Advisory Board attempted to do just that in a new series of ads that presented wine as the essence of the “California Way of Entertaining” (Figure 5). Highlighting wine’s respectability and accessibility, the ads stripped wine of all pretense and worrisome etiquette by situating it in the informal setting of California potlucks and buffet dinners featuring all-American fare (baked beans, hamburgers, fried chicken, lettuce and tomato salads, cold cuts, and casseroles). The “California Way” ads also sometimes featured Burgundy with spaghetti and meatballs, the pseudo-Italian dish that ranked among many postwar Americans’ beloved comfort foods. Footnote 74 Promising “less fuss … more fun,” Footnote 75 entertaining the California way made minimal demands on the hosting couple: “You just serve some ‘potluck,’” open a “cool bottle of wine” for the guests, and add some wine to the dishes to make “even the plainest things taste extra-special.” Footnote 76 The Wine Advisory Board cleverly turned the problem of wine anxiety on its head. Instead of figuring wine as the beverage that aroused social insecurities, the Wine Advisory Board cast wine as the beverage that would ease the burdens of home entertaining. “Good things happen when you cool and serve wine,” one such ad promised. Footnote 77 “You make guests feel honored. You make the dinner taste extra good. And you add the color and sparkle that gives simple entertaining an air of glamour.” Footnote 78

Figure 5 Wine Advisory Board ad, Life Magazine, 1951.

Significantly, the novelty being sold in these ads was not a foreign beverage but the “California Way.” Since the days of the Gold Rush, many Americans had looked to California as the place where dreams come true. In the following decades, boosterism by real estate developers, railroad companies, and Hollywood movie studios lured Americans to the Golden State. The postwar years saw an explosion of media interest in California as the state underwent remarkable economic growth, fueled by suburbanization, the baby boom, the expansion of the defense industry, and public investment in state universities and the interstate highway system. Nationwide, postwar homebuilders and advertisers popularized California’s iconic suburban ranch house, with its expansive patios and large windows that invited the outdoors in. Magazine stories celebrated California’s style of informal indoor-outdoor living, tantalizing readers with their portraits of white middle-class suburbanites at play. Whether tending their garden, enjoying their swimming pool and backyard barbeque, or dining al fresco on the patio, Californians seemed to most perfectly embody postwar dreams of the good life. Footnote 79 Genevieve Callahan’s The New California Cook Book: For Casual Living All Over the World, published in 1946, heralded the California way of life as “a blending of comfort and style, casualness and care, functionalism and fun.” It was a way of life, Callahan wrote, that explained why “we Californians like to eat so many of our meals under the skies; why we are constantly figuring ways to cut down kitchen time indoors to give us more time outside; why we like to substitute informality for formality, imagination for elaboration, flavor for fussiness.” Footnote 80

The Wine Advisory Board ads capitalized on such familiar fantasies of the good life and fed them back to readers—only this time the California dream gave wine a starring role. The colored drawings that illustrated the ads invited readers to experience California’s famed indoor-outdoor living by using the framing device of a picture window that allowed readers to simultaneously glimpse the interior and exterior of a California ranch home. In one such ad, two casually dressed married couples—the men wearing sports jackets (one without a tie), the women wearing skirts and sleeveless tops—served themselves wine and cold cuts from the checkerboard-cloth-covered buffet table in the living room, which opened onto a large outdoor patio. By situating wine in a familiar landscape of consumer desire, such images allowed ad readers to know and digest the foreign as something that was simultaneously glamorous yet mundane. The ads made California wine as much at home in middle-class suburbia as was the architecture of the California ranch home. In so doing, the Wine Advisory Board enabled consumers to divest wine of its highbrow mystique and its skid row aura and embrace wine as a beverage that belonged in their homes, at their parties, and on their dinner tables.

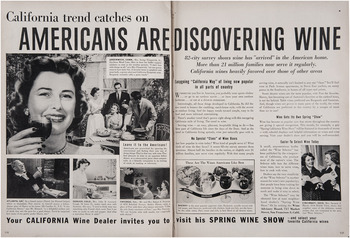

The new strategy of linking wine to a glamorized California regional identity—and by extension to middle-class suburbia writ large—helped to expand wine’s national reach. In 1953, three years after launching the “California Way” ad campaign, the Wine Advisory Board proclaimed the “California trend catches on—Americans Are Discovering Wine” in a two-page spread in Life, McCall’s, and Collier’s magazines (Figure 6). Presented in a news-story format, the ad cited an 82-city survey—conducted by J. Walter Thompson, which found that “almost half the families in the nation, or slightly over 21 million families, now serve wine regularly”—to bolster its claim that wine drinking was no longer bounded by class or even by region. Footnote 81 “You’ll find wine in Park Avenue apartments, in Down East parlors, on sunny patios in the Southwest, in homes of all types and classes.” The ad attributed wine’s growing mass appeal to the widespread popularity of the “easygoing ‘California Way’ of living.” In the Wine Advisory Board’s view, consumers who chose to do things the California Way were, in essence, choosing to shun convention and do things the American way:

Leave it to the Americans! Americans are proverbial for ignoring the conventional and finding their own way of doing things. They’re that way with wine. They find pleasure in wine as an appetizer before dinner, as a conversation piece when company calls, as a friendly companion to an evening of cards, or reading, or television. Footnote 82

Figure 6 Wine Advisory Board Ad, Life Magazine, 1953.

To make such claims convincing, the ad replaced the colored drawings in the earlier California Way ads with photographs of real Americans consuming wine in their homes and, perhaps to underscore that serving wine to guests was no cause for embarrassment, the ad printed the full names and street addresses of their testimonial givers. A small photo insert showed Mr. and Mrs. Robert E. Peterson, of Skokie, Illinois, enjoying a glass of port while watching their after-dinner television. Next to the Petersons was a photograph of Mrs. John Gerrard-Gough pouring Sauterne into her lamb stew cooking on the kitchen stove. Having once thought “wine was something only French chefs used,” Mrs. Gerrard-Gough attested that she now used wine “as easily as salt and pepper.” Footnote 83

The ad’s populist tone was striking: here were consumers who “ignored the conventional,” refused to “fuss,” and gave no more thought to using wine to flavor stews than they would to using salt and pepper. Americans were “discovering wine” not because they were interested in emulating French chefs or mastering aristocratic wine protocols but because they had found ways to incorporate wine unceremoniously into the daily rituals of American leisure: card playing, TV watching, book reading, and dining al fresco.

The egalitarian marketing appeals that aimed to enhance California wine’s mass-market allure buttressed related postwar trends in home cooking and home entertaining. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, some cooking trends catered to upper-middle-class professionals with gourmet culinary sensibilities. Magazine stories about couples who “cooked with wine, tossed big green salads in wooden bowls they never washed, and served their guests casual yet dramatic dishes” became “a staple of gracious-living journalism.” Footnote 84 The postwar boom in cookbook publishing also inspired adventurous home cooks to experiment with new herbs and spices; to flavor soups and stews with wine; and to try their hand at ethnic-inspired dishes like paella, chow mein, tamale pie, and lamb curry. Even as cookbook authors and food columnists exhorted home cooks to explore new culinary horizons, they offered shortcuts and affordable substitutes that promised to deliver gourmet results without the expense or the fuss. The postwar food industry enlisted the aid of home economists and food columnists to craft recipes that transformed dishes made almost entirely from canned goods into party food through the addition of wine to the sauce, sherry to the bottled shrimp bisque, or curry powder to the chicken casserole. Footnote 85 This simple technique of “glamorizing” dishes with alcohol and exotic spices enabled homemakers with modest budgets of time and money to experiment with genteel cultural styles on their own terms: homemakers could acquire some of the trappings of gracious living, even as they contentedly cast aside gourmet demands for culinary perfection and authenticity. The Wine Institute helped to popularize the practice of “glamorizing” food by sending recipes for wine-enhanced dishes to home economists such as Mary Meade, who reprinted one for Chicken Cream Hash in her Chicago Tribune column. Footnote 86

Wine marketers and cookbook authors also courted wine neophytes by substituting subtle mockery of genteel pretensions for didactic instruction in the art of gracious living. Peg Bracken’s The I Hate to Cook Book, published in Reference Bracken1960, advised reluctant cooks and hostesses to keep it simple by making good use of convenience foods and enlivening dishes with generous doses of wine. Her crab bisque called not just for a spoonful of sherry but for three-quarters of a cup. Selling more than three million copies, The I Hate to Cook Book owed much of its appeal, Laura Shapiro argues, to Bracken’s “deft disparaging” of intimidating culinary lingo. If pressed to converse with “women who love to cook,” Bracken advised, “don’t say ‘onions.’ Say ‘shallots,’ even though you wouldn’t know one if you saw one. This gives standing to a recipe that otherwise wouldn’t have much.” Footnote 87 Similarly, the Wine Advisory Board demystified wine by disentangling it from the rhetoric and rituals of wine connoisseurship. Wine Advisory Board ads distilled wine instruction to the bare minimum: “Enjoy the [wine] you like best, without waiting for special occasions or bothering about the formalities of what wines to serve with certain foods.” Footnote 88 The Wine Advisory Board’s Wine Cook Book, a thirty-page pamphlet with recipes for wine-infused soups, seafood/meat/chicken dishes, vegetables, and desserts, struck a similarly populist note. “Stemmed wine glasses are pretty if you happen to have them. But any tumbler from the dime store is a wine glass—a very acceptable one, too.” Footnote 89 In essence, wine belonged on every American table, whether housewives shopped at Woolworth’s or Saks Fifth Avenue. The Wine Cook Book advised readers to forgo mastering esoteric knowledge of vintage years because in California every year was a vintage year. “Let epicures stroke their beards and grow ecstatic over ‘vintage years.’ They mark the every-so-often good vintages of Europe—the numbered years when the grapes thrive. In California’s uniform climate the grapes grow luscious every year.” Footnote 90

The Wine Advisory Board’s campaign of demystification had to strike the right balance between appealing to middle-class patrons’ populist disdain for wine rituals while simultaneously satisfying their middlebrow yearnings for cultural literacy. Leaving middle-class consumers without any guidelines—just the assertion to drink “the wine you like best”—would have likely generated as much anxiety as having too many rules. The key was to help middle-class consumers acquire enough cultural capital to select wine and order it in a restaurant without fear of embarrassment. The Wine Advisory Board ads continued a pared-down wine education strategy, choosing to focus on only four types of wines—sherry, port, sauterne, and burgundy—but consumers eager for more suggestions of appropriate food and wine pairings could order a free copy of the Wine Advisory Board’s “California Wine Selector,” an accordion-fold leaflet that described eight popular wines (sherry, port, burgundy, muscatel, champagne, claret, vermouth, sauterne) and the types of foods they complemented. The reverse side featured recipes for twelve wine dishes. Wine neophytes could carry the leaflet with them into supermarkets and liquor stores and use it as a quick cheat sheet to eliminate the guesswork of selecting an appropriate wine. Within months of its 1952 debut, retailers had moved 6.8 million copies of the leaflet through point-of-sale giveaways. Footnote 91

The Wine Advisory Board also produced more than a dozen cooking-with-wine pamphlets in the 1950s, including ones devoted specifically to chicken/turkey/fish dishes, desserts, and cheese. Footnote 92 They became a crucial part of the wine-merchandising infrastructure because they enabled a variety of food manufacturers, through tie-in promotions, to buttress the Wine Advisory Board’s populist message that wine could enhance the foods Americans loved and regularly purchased. According to the Western States Meat Packers Association, Wine Advisory Board recipes for wine-infused meat dishes “went like hotcakes” during the wine industry’s Wine-with-Meat campaigns in supermarkets, conducted in partnership with the Meat Institute and western Meat Packers Association—a sure sign of consumer interest in learning the culinary tricks-of-the-trade that could “make their meat dollar go further” and transform less popular meats into appetizing fare. Footnote 93 Although the booklet included recipes for standard meat cuts—ham baked in muscatel with peach halves, burgundy pot roast, and burgundy pork chops with spicy prunes—other recipes promised to enhance canned meats, cheaper cuts, and leftovers, usually with a novel ethnic spin. Adventurous cooks could find recipes for curried lamb shanks, North Beach Meat Balls, braised liver in white wine, and Turkey a La Queen (a casserole made with sherry, cheddar cheese, and mushrooms). Footnote 94 In 1955, the Wine Advisory Board reported that tie-in promotions with cheese and meat producers had generated a “startling” increase in consumer requests for the wine recipe booklets. Footnote 95

An even more significant and enduring merchandising innovation was the invention of the informative back label on wine bottles in 1951. Inglenook (a premium winery in Napa Valley) and Almaden-Madrone Vineyards (a premium winery in California’s Santa Clara Valley) introduced the back label nearly simultaneously. Charles Krug, another Napa Valley premium winery, followed suit in 1956. The informative back label sought to attract amateurs and connoisseurs alike by providing shoppers with concrete information about the grape variety and the foods that went with the wine. As Sales Management reported, “The label idea was so obviously what the mysterious wine bottle needed to help sales people and consumers to approach it with confidence, that it was quickly adopted by vintners who felt that their wines could speak for themselves if understandable language was used.” Frank Schoonmaker, who started his career as a wine importer and subsequently became director of sales and production at Almaden-Madrone, adopted the back label in hopes of banishing the “wine hokum” that, in his view, had pushed “the average American to say, ‘To hell with it!’—and call for a Scotch and soda.” Footnote 96

The campaign to demystify and Americanize wine shared some of the same democratizing impulses that enabled middle-class consumers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to transform dining out from the exclusive privilege of the wealthy into a common middle-class pastime. As historian Andrew Haley has shown, middle-class diners “challenged nineteenth-century elite ideas that French cuisine was the only cuisine of merit” and instead touted their own appreciation for ethnic dining and culinary diversity as evidence of their superior cosmopolitan tastes. Middle-class diners successfully “challenged the aristocrats’ monopoly of dining culture” by pressuring restaurateurs to abandon ostentatious multicourse dinners, simplify menus, lower prices, “ban the French-language menu and replace French cuisine with cosmopolitan fare.” Footnote 97

The Wine Advisory Board similarly pressured restaurateurs to price wine for popular appeal (under 25 percent of food costs) and to simplify wine menus by grouping wines according to their use: “appetizer, white dinner, red dinner, dessert and sparkling wines.” Footnote 98 Almaden-Madrone winery, under Schoonmakers’s direction, contributed to the populist turn in restaurant wine merchandising by introducing the fifty-cent “pony,” a bright green, decanter-shaped bottle that held an individual serving equivalent to two glasses of wine. The pony enabled restaurateurs to overcome diners’ reluctance to spend more than a dollar for wine and the waitstaffs’ reluctance to fumble with corkscrews. Footnote 99 Other restaurateurs advanced the Wine Advisory Board’s campaign of demystification by taking good-humored digs at wine connoisseurs and European wine drinking practices. A footnote on the back of one proprietor’s wine list read: “Connoisseurs say that all food tastes better when wine is taken with it. In many countries in Europe, the people use water only for washing. We don’t advise going that far—but we do say that a good wine will make a good dinner even better—and we handle only good wines!” Footnote 100

Even as populist wine merchandising sought to create a distinctly American wine drinking tradition, one that adapted European traditions of drinking wine with meals but rejected connoisseurship as an aristocratic affectation, American winemakers stubbornly clung to the practice of borrowing European place names and appellations (Burgundy, Rhine, Chablis, Port, Sherry). Much to the dismay of European winemakers, who resented Americans’ usurpations of their prized appellations, California and New York winemakers long resisted adopting American regional and varietal designations partly because they regarded such terms as “generic” and were reluctant to sacrifice the Old World cachet that European names commanded. Footnote 101 The postwar growth in imported table wines, though still only 10.6 percent of the total U.S. table wine consumption by 1960, may have reinforced vintners’ reluctance to abandon European wine names. American buyers of imported table wines, however, represented an elite segment of the wine market, consisting mainly of luxury hotels and restaurants and connoisseurs who kept their own cellars. Footnote 102 They were not the mass-market prospects at whom the Wine Advisory Board was aiming most of its promotional firepower, even if they were the types of customers that California’s premium vintners longed to allure.

In the short run, the most important contest for American wine’s supremacy on the restaurant dining table was not the battle between American wines and European imports but the battle between wine and far more ordinary mealtime beverages. Wine’s real enemies, American Restaurant Management proclaimed, were “the coffee pot and the water tap.” The 400 Restaurant, on Fifth Avenue in New York City, priced wine by the glass because that “unit of sale … match[ed] coffee by the cup,” and best met existing consumer expectations for a mealtime beverage. Footnote 103 Ted’s Grill in Santa Monica went even further to establish a cultural equivalency between wine and coffee by selling them for the same price. Footnote 104 The Wine Advisory Board also encouraged restaurateurs to elevate wine’s mealtime presence by setting their tables with wine glasses (in addition to the customary water glasses or coffee cups) and placing an “unopened half bottle of wine on each table,” with a bottle topper that read, “Ask your waiter to serve this bottle.” Footnote 105 Restaurant trade journals reported remarkable success with the merchandising strategy. At Rubin’s Restaurant in Tampa, Florida, wine sales increased by 300 percent after the restaurant started placing individual six-ounce splits on the table, priced at sixty cents. Footnote 106 By claiming a place on the table, where customers ordinarily encountered condiments and seasonings, the wine glasses and the unopened wine bottle symbolically affirmed wine’s mealtime role as a complement to the food on the plate. In making space for wine among the condiments and the seasonings, restaurateurs took a decisive step toward making a home for wine in the American meal.

Despite these successful merchandising innovations, competitive rivalries and competing visions of how to build a mass market sometimes undercut the industry’s collective efforts to promote wine as a mealtime beverage. While some vintners saw the industry’s long-term future in table wines and worked to lure consumers to the dining table, others pursued the path of least resistance by adapting wine merchandising and product development to existing consumer preferences for sodas and more potent forms of alcohol. The winning displays in the Wine Advisory Board’s dealer contests from 1952 and 1954 reflected these competing visions of wine’s best path to mass-market success. The dealer contests awarded prizes to restaurants, package and grocery stores, dealers, and hotels for innovative merchandising displays that invited consumers to “discover the pleasures of wine” during October’s National Wine Week. In 1952, when veteran winemaker Edmund Rossi, a long-time table wine advocate, headed the prize committee, the grand prize went to Brandywine Liquors of Wilmington, Delaware, for its promotion of American wine as “The Best ‘DRESSING’ for your Thanksgiving Dinner.” The runners-up all linked wine to food—one tied wine in with the National Cheese Festival and Borden’s cheese advertisements, another built a wine and meat display, and yet another urged housewives to serve their guests fruitcake and port at Thanksgiving and Christmas. Footnote 107 In 1954, when Ernest Gallo managed the contest, the outcome was strikingly different. The grand prize in the wholesaler’s division went to Harry Bleiweiss, an enterprising Gallo sales manager who had installed 213 displays in 174 retail stores and introduced a new wine cocktail made from lemon juice and California White Port, Gallo’s flagship wine. Footnote 108 The winning drink eventually debuted on the national market in 1957 as Thunderbird, one of the first bottled wine cocktails.

Thunderbird’s invention reveals much about how Gallo conceived of the American mass market. He crafted wines that met the mass market where he found it: in African American inner-city neighborhoods, where consumers had long mixed their own cocktails by adding lemon juice to white port. On sales calls, Bleiweiss and Albion Fenderson, Gallo’s sales and advertising director, had “noticed that liquor stores in predominantly black communities routinely kept bottles of lemon juice or packets of lemon Kool-Aid next to their white port bottles” because their customers liked to mix them. Bleiweiss lighted on the idea of packaging the mixture in one bottle, and Ernest Gallo enthusiastically assented after a preliminary taste test convinced him that “those black guys are pretty good winemakers!” Gallo’s white port, a sweet wine made from Thompson seedless, Malaga, Muscat, and French Colombard grapes, was, if anything, too sweet, so the addition of lemon juice corrected the sugar–acid balance. With Thunderbird, Gallo now had a new use for white port and a new product that could absorb the ever-abundant supply of cheap Thompson seedless grapes. Footnote 109

Thunderbird’s official debut followed closely on the heels of Italian Swiss Colony’s “Silver Satin,” another citrus-flavored white port, and together they launched the new field of “pop wines,” or specialty flavored wines. This new spin on the wine cocktail captured a very different segment of the mass market than the white middle-class suburbanites the Wine Advisory Board had sought to interest with its recipes for wine spritzers, sherry Old Fashioneds, and wine club cocktails. The new flavored wines won favor among African Americans and novice college-aged drinkers looking for something sweet but potent. The street branding of Thunderbird, a beverage that shared its name with the racy Ford sports car and was priced at sixty cents a quart, made its primary intended audience clear. Not only did the “hot rod” name assure buyers that Thunderbird packed a punch—and that it did at 21 percent alcohol by volume—but Gallo “test-marketed and distributed Thunderbird in all the key black stores in Los Angeles, Houston, Shreveport, and New York City” and “arranged for street-sampling” in black bars. Gallo salesmen reportedly even threw a few empties in the gutters to boost awareness of the new flavored wine. Footnote 110 Although Gallo employed the elegant stage and screen actor James Mason to vouch for Thunderbird in television commercials and ran magazine ads that cast Thunderbird as a sophisticated aperitif for white middle-class ladies, Thunderbird’s name, its cheap price, and its strong presence in black urban markets marked Thunderbird as a ghetto wine.

Thunderbird’s roaring success lifted Ernest Gallo to his long-coveted position as the nation’s number one volume winemaker—a distinction he won, ironically, not by translating his own Italian-American tradition of drinking wine with meals to the mass market but instead by embracing an entirely different ethnic tradition: the African American custom of mixing white port with citrus juice. For that, he won the enmity of some winemakers who saw Thunderbird as a blow to wine’s hard-fought quest to overturn its image as the beverage of skid row. Others credited Ernest Gallo with broadening the base of prospective table wine consumers. As Eric Larrabee, a table wine lover, wrote in his 1959 profile of the California wine industry, “Gallo and other volume wine-makers have been trying to by-pass the whole annoying problem of selling wine as wine by selling it as though it were something else—new beverages that are clear, slightly syrupy, flavored with herbs and citrous [sic] extracts, and bearing such names as Thunderbird, White Magic, Roma Rocket, and Silver Satin. Gagging slightly, I salute his efforts.” Footnote 111 Larrabee could guardedly praise Thunderbird without fear of tarnishing wine’s reputation because flavored wines were, as he put it, “something else”—different enough to maintain reputational distinctions but similar enough to perhaps ease consumers’ way to the table wines he preferred.

Conclusion

Larrabee’s tribute to Gallo, Guild, and Italian Swiss Colony for grasping how to sell wine not as wine but “as though it were something else” cut to the core of the marketing dilemma that had plagued American wine makers since the repeal of Prohibition: how to create a mass market for a beverage that struck many Americans as simply too foreign. Whether vilified for its associations with luxurious living, immigrant drinking customs, or skid row drunkards, wine proved a tough sell, especially among middle-class consumers who favored spirits and cocktails. To win over such consumers, the wine industry refashioned wine into more familiar forms and promoted wine’s glamour without the demands of connoisseurship. By marketing wine as a base for cocktails, a flavorful addition to classic American dishes, and the thrifty housewife’s secret to fuss-free hospitality, the Wine Institute and Wine Advisory Board attempted to strip wine of its foreignness and make wine at home within the dominant postwar visions of the middle-class good life.

By the end of the 1950s, those marketing strategies appeared to be paying substantial dividends. From 1948 through 1960, adult consumption of all wine types had increased by 17 percent (from 1.28 to 1.5 gallons per capita). Especially notable was the substantial growth in adult table wine consumption—a 69 percent increase between 1948 and 1960—with the most impressive gains occurring in the state that pioneered the “California Way of Entertaining.” Footnote 112 In 1960, Californians consumed nearly as much table wine as dessert wine—a huge gain from 1945, when Californians drank 2.5 gallons of dessert wine for every gallon of table wine. The latter ratio prevailed in much of the nation until 1967, when table wines finally overtook dessert wines. Footnote 113

How much of these gains can be attributed to the advertising and mass-merchandising campaigns organized by the Wine Institute and the Wine Advisory Board is open to debate. Brand advertising by the largest volume producers—Roma, Gallo, Petri, and Italian Swiss Colony—undoubtedly helped to boost wine sales. So, too, did the growth of wine tourism during the 1950s, which drew more than 250,000 visitors annually to the California wineries mapped on the Wine Institute’s tour brochures. Footnote 114 The separate public relations campaigns of California’s premium wineries, which staged comparative tastings of European and California wines during the 1950s, also brought greater renown to California premium wines—the coastal wines made from superior grape varieties. The California wines won the blind-taste contests half the time. Footnote 115 Given that premium wine makers produced at best 5 percent of the state’s table wine, however, such positive publicity could only account for a portion of the steady growth in wine sales. By 1961, California’s Big Three volume producers still produced more than 60 percent of all California wines sold nationally. Footnote 116

What the Wine Advisory Board and Wine Institute helped accomplish cannot be measured by statistics alone. In his market research studies from the mid-1950s, Ernest Dichter attributed wine’s “new popularity” in restaurants and homes to the “demand for new taste experiences” and the new “wine thirst” sparked by travels in Europe, but he particularly lauded the Wine Advisory Board’s move to “soft-pedal” the “connoisseur appeals” that had previously “intimidated potential wine drinkers.” Footnote 117 Dichter might have also noted that the populist turn in wine promotion worked hand in hand with parallel trends in home cooking that fostered a greater sense of culinary adventurism. The Wine Advisory Board and the Wine Institute were hardly passive beneficiaries of such food trends. Rather, they actively enlisted the aid of “fashion intermediaries”—home economists, cheese manufacturers, and meat trade associations—to encourage homemakers to cook with wine and serve it at mealtime. Footnote 118 Together, these groups helped sow the seeds of the table “wine revolution” in the 1940s and 1950s by connecting the pleasures of American wine to the pleasures of suburban living and the informality of the “California Way.” Those efforts brought table wine to the American middle class by way of the suburban ranch house and patio dining, the informative back label, the “glamorized” wine-infused casserole, and the new restaurant practice of ordering wine by the glass—all innovations of wartime cookery and postwar merchandising. The spread of gourmet culinary sensibilities certainly explained some of wine’s growing cultural appeal, but a populist counternarrative that positioned wine as the beverage that could deliver pizzazz without the fuss or the expense helped resistant middle-class consumers welcome wine into their rituals of cooking, dining, and home entertaining.