This is the 67th annual meeting of the Business History Conference, and also the 50th since the organization elected officers and made a presidential address part of the gathering. That latter milestone calls for at least some reflection about how much the world of business, the field of business history, and the BHC has changed since 1971. And so I am going to begin these remarks with some brief observations about interrelated transformations in each of these three domains.

But I will then shift my focus to a key dimension of continuity in business history – how we tend to organize research projects and our teaching. For all the novel questions that we now collectively pose, all the new methods that we have borrowed from cognate disciplines, and all of the many ways that this scholarly society now operates more ambitiously and inclusively, we still primarily do our most important work as sole proprietors, and occasionally as members of short-lived partnerships. In line with this year’s conference theme, “Collaboration in Business and Business History,” I’d like to invite you to consider the potential payoffs of expanding the contexts in which we work together, with colleagues from cognate fields, and with our students. A growing number of us are already moving in this direction, so we have a platform on which to build.

First, let’s cast our eyes back a full five decades. In 1971, a few of you were already engaged in historical scholarship, and perhaps even attended the 1971 BHC annual meeting. Some of you were in secondary school or at a university. More than half of you were not yet alive. In the first part of that year, I was five years old, having recently moved with my family from New York City to Louisville, Kentucky. That move, incidentally, was motivated by two intersecting changes then roiling the American business environment. Amid growing skepticism about the advantages of the conglomerate, a much smaller number of corporations needed legal counsel with expertise in overseeing mergers of unrelated companies. And with evidence mounting that tobacco use had devastating impacts on health, tobacco manufacturers redirected their in-house lawyers to focus on defending a burgeoning set of tobacco liability lawsuits.

Those two developments had significant implications for my family, since my father, Donald Balleisen, a corporate attorney whose previous firm, Penick & Ford, had been bought out by RJ Reynolds in the early 1960s, spent the next several years in New York City helping his new employer acquire other businesses. Toward the end of 1968, at least as my dad told the story, he learned that he had two choices – to move to Winston-Salem, where RJ Reynolds had its headquarters, and bone up on defense strategies for tobacco makers in product liability litigation, or find other employment. After a long set of inquiries made clear that amid a softening economy, there was little demand in New York for a corporate litigator who had significant experience in mergers & acquisitions but who also had reached his mid-forties, he was able to secure a partnership offer from a law firm in Louisville.

There were also some indications that the University of Louisville Law School might be interested in hiring my mother, Carolyn Balleisen, to teach tax law. After undergraduate studies at Brooklyn College and then Barnard College, she had graduated from Columbia Law School in 1952, and had worked in several capacities during the 1950s, including as a researcher for an American Law Institute project to propose revisions to federal taxation policy. But amid enormous cultural opposition to expanding career opportunities for female lawyers, she had struggled to land a permanent position in a law firm.Footnote 1 So my family moved; and so I grew up in a part of the urban American South just beginning to encounter the pangs of deindustrialization, and soon to undergo court-ordered desegregation, a process that I experienced firsthand in the early 1980s as a student at Louisville Central High School.

I mention this personal interlude partly because of the BHC tradition of presidents saying something about their biographies in their addresses, but mostly because it illustrates the basic point that shifts in the business world always have wide-ranging consequences, often not grasped fully (or at all) at the time. The last half-century has ushered in wrenching change that has reshaped all of our experiences as consumers, employees, and citizens. Those transformations have also influenced a significant fraction of our intellectual predilections and preoccupations, nudging members of this community toward some research agendas and away from others.

Just to remind you all of some of the most important developments – since 1971, societies across the globe have adapted to a host of dramatic technological innovations, including the green revolution in agriculture, the rapid growth of automated manufacturing, and often dizzying advances in computing and communications. Social movements premised on commitments to equality for previously disfavored groups have refashioned law and norms in an expanding number of countries, and so reconfigured the demography and culture of institutional life, including that of business. We have seen the acceleration of powerful ideological trends, such as the presumption of rational economic behavior and the lionization of markets as allocators of resources, as well as countervailing ideas emerging from new fields like behavioral economics. We have witnessed the completion of post-World War II decolonization, the collapse of the Soviet order, and the emergence of a second age of globalization, driven as much by financialization as by the remaking of transportation infrastructure, the construction of continental and international trade regimes, and the dramatic impacts of advances in computation and communications.Footnote 2

After several decades of relative stability in the lists of the world’s most valuable corporations, the last forty years have brought much more flux. Longstanding industrial giants have weakened and even disappeared, while newer firms at the forefront of information technology and distribution have accumulated profits and power. With each passing decade, an economic rebalancing away from the dominance of the United States and Western Europe has gathered pace, with firms, workers, and consumers in China and India the major beneficiaries. With every passing year, greater numbers of people across the globe express concerns about waxing environmental challenges, none greater than climate change. Those concerns have prompted increased attention from a number of multi-national businesses, as well as the growth of new public-private partnerships to address the challenges of sustainability. Other abiding worries include explosive growth in economic inequality and the reemergence of global financial instability. Each of these trends seem to be key drivers of the nationalism, populism, and outright authoritarianism that have gained so many footholds since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.Footnote 3

These interconnected transformations have both directly prompted extensive research undertakings by business historians and indirectly influenced a wider set of research agendas about the much deeper past. Addresses given by BHC presidents at annual meetings suggest the intellectual shadow cast by the dominant events and historical processes of the last half-century. Their topics over the past two decades have included the importance of understanding the accelerating processes of globalization,Footnote 4 the corporate incorporation of information technology into core functions,Footnote 5 the bases of creating sustainable profits (a key element of waxing economic inequality since the 1970s),Footnote 6 the value of exploring business failures (arguably an outgrowth of heightened financial instability),Footnote 7 the implications of gender as a category of analysis for business history,Footnote 8 and the significance of cultural, political, and policy responses to financial crises.Footnote 9 At the moment, as we all scour news reports for the unfolding dynamics and economic effects of the COVID-19 global pandemic, it is not hard to envisage that at some point in the next decade, we will see a BHC president focus on the connections among business, the environment, and public health, whether in the recent or more distant past, or rather, given the pandemic’s disruption of supply sources for so many goods, on the post-1980 construction of global value chains and just-in-time approaches to inventory management.

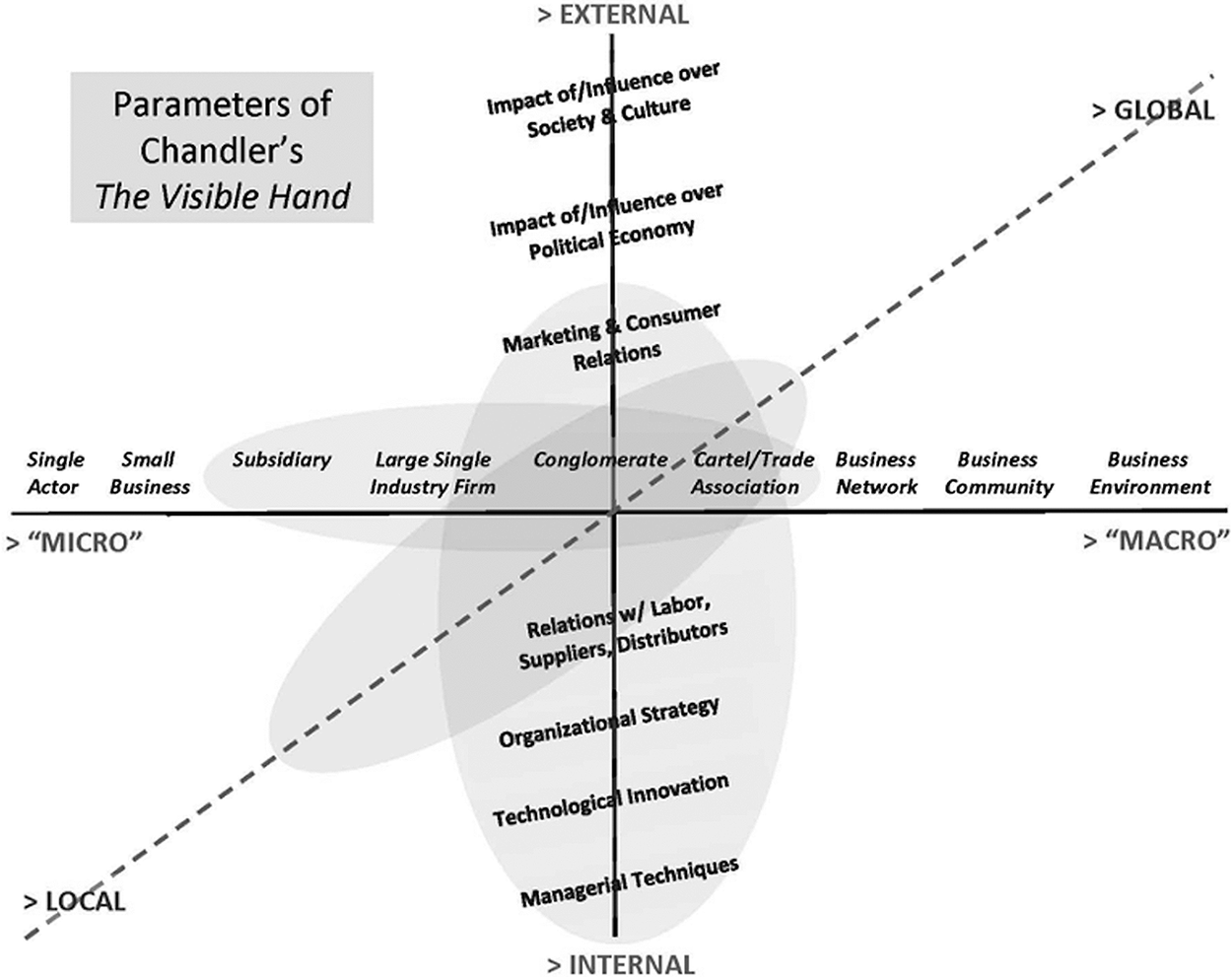

Here’s one way to conceptualize key shifts in our field over the past half-century. One can think about business history across three intersecting axes, regardless of the specific era in question (See figure 1). The first of these involves the scale of business activity, which extends from the most micro (an individual actor in some enterprise, or rather a small family firm), all the way to the most macro (the business environment of a society or the entire planet).

Figure 1 A Three-Dimensional Framework for Business History.

The second axis defines how a scholar conceives of “business” in relation to other domains of human interaction, and the nature of causal forces that impel change in business history. Here the continuum ranges from a more “internalist” view to a more “externalist” one. For business historians who adopt a more internalist posture, the key questions address the inner workings of firms, the ability of managers to use information about internal functions and modes of accounting to adjust firm direction, and the manner in which those enterprises relate to technological developments, markets, and other firms. Accordingly, the key methodological touchstone for these scholars often lies in economic analysis, since widespread changes in corporate strategy generally reflect perceptions about economic imperatives. Internalists sometimes also presume that broader social, cultural, and political forces typically have limited impact on firms, even if developments within the business world might have enormous consequences for society, culture, and politics.

For those who adopt more of an “externalist” view, many other questions deserve attention aside from how firms operate and how those operations change over time in response to technological innovations and economic conditions. These scholars often focus on the political, social, and cultural ramifications of business activity. Alternatively, they investigate the impact of policy, social dynamics, and cultural transformations on the structure and purposes of business enterprise, whether with regard to specific firms, business networks, or the business environment.

The third axis in this way of apportioning the conceptual space of business history identifies geographic reach. Does a scholar seek to understand business in an intensively local context, perhaps zeroing in on the experience of a specific entrepreneur or firm? Or does that business historian move out to a regional, national, continental, transoceanic, or even truly global view, whether to trace the connections of a firm or industry across space, or engage in comparative analysis?

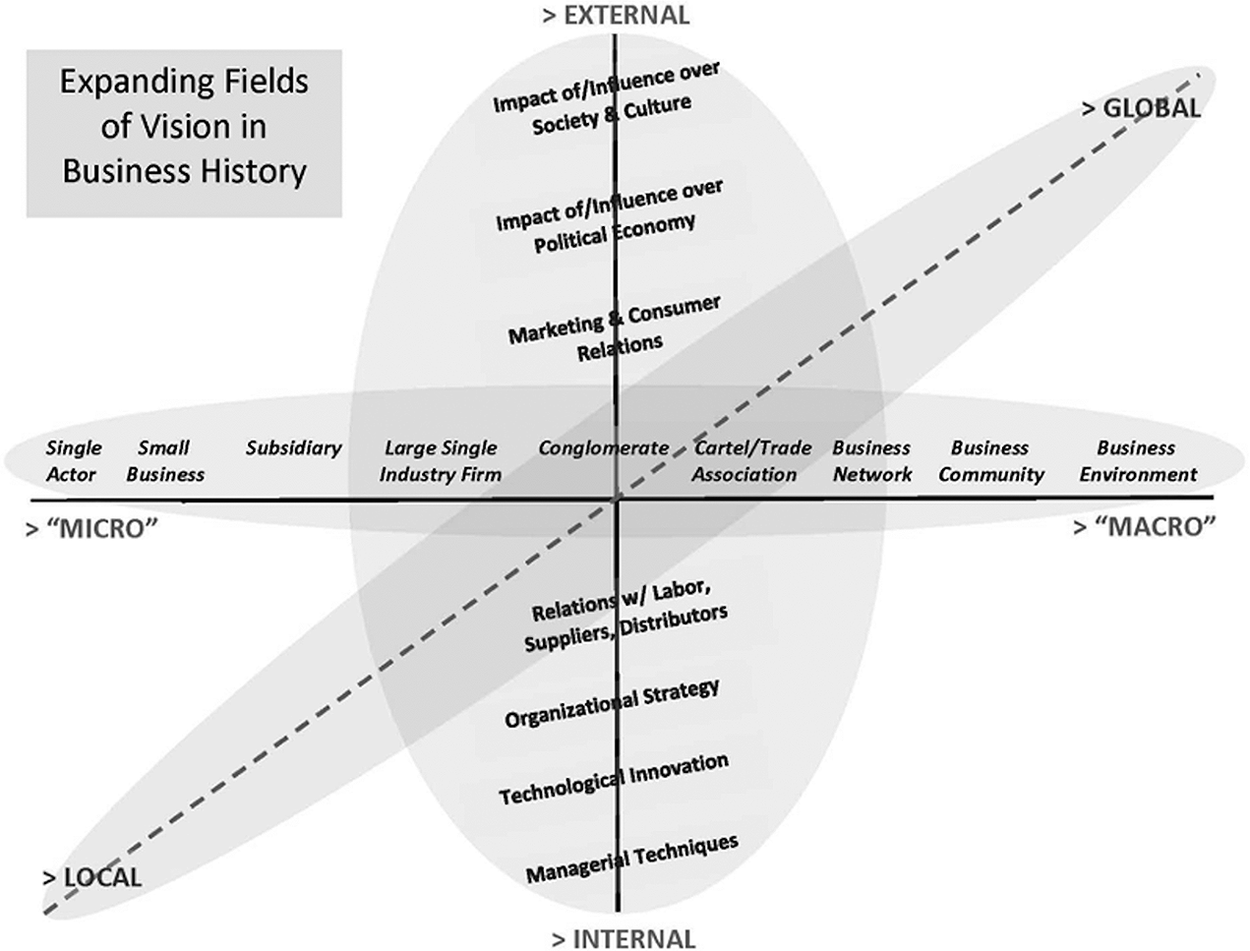

If we take Alfred Chandler’s scholarship as reflecting the dominant trends for business history in the 1970s, one might sketch the field’s key domains as depicted in Figure 2, with an analytical lens set toward internalist analysis of the largest industrial firms in the United States from the late nineteenth century through the first three-quarters of the twentieth. Chandler wished to understand the origins and evolution of the mammoth American corporations that occupied such a dominant economic position across the industrialized world by the mid-twentieth century. He thought such an inquiry demanded careful reconstruction of managerial innovation – particularly the organizational insights that allowed firms to learn from the mass of information that they could collect about their suppliers, their own manufacturing efforts, and their approaches to marketing and distribution, and then design an appropriate balance between decentralized freedom of action for business units and overarching strategic direction from corporate headquarters. Thus Chandler’s research had a national reach, concentrated on large firms (though including their interactions with divisions and subsidiaries, and extending to business associations like cartels that often preceded full-blown integration), and remained resolutely focused on managerial decision-making (though including relationships with suppliers and customers).

Figure 2 The Approach to Business History in Alfred Chandler’s The Visible Hand.

Chandler’s influential 1977 book, The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business, which had over 14,400 citations on Google Scholar as of March 2020, and adds a seemingly inexorable 60-80 citations a month, encapsulates this approach to business history. The index to The Visible Hand provides scores of entries for specific corporations that came to adopt complex, decentralized modes of management and the integration of supply, manufacturing, and distribution. But there are no entries for entire swaths of business-related public policies, such as antitrust or taxation; just a couple of references to World Wars I or II, which had such a profound impact on technological change and the shape of so many markets; and mentions of a few pages that discuss Europe, but none for South America, Africa, or Asia.

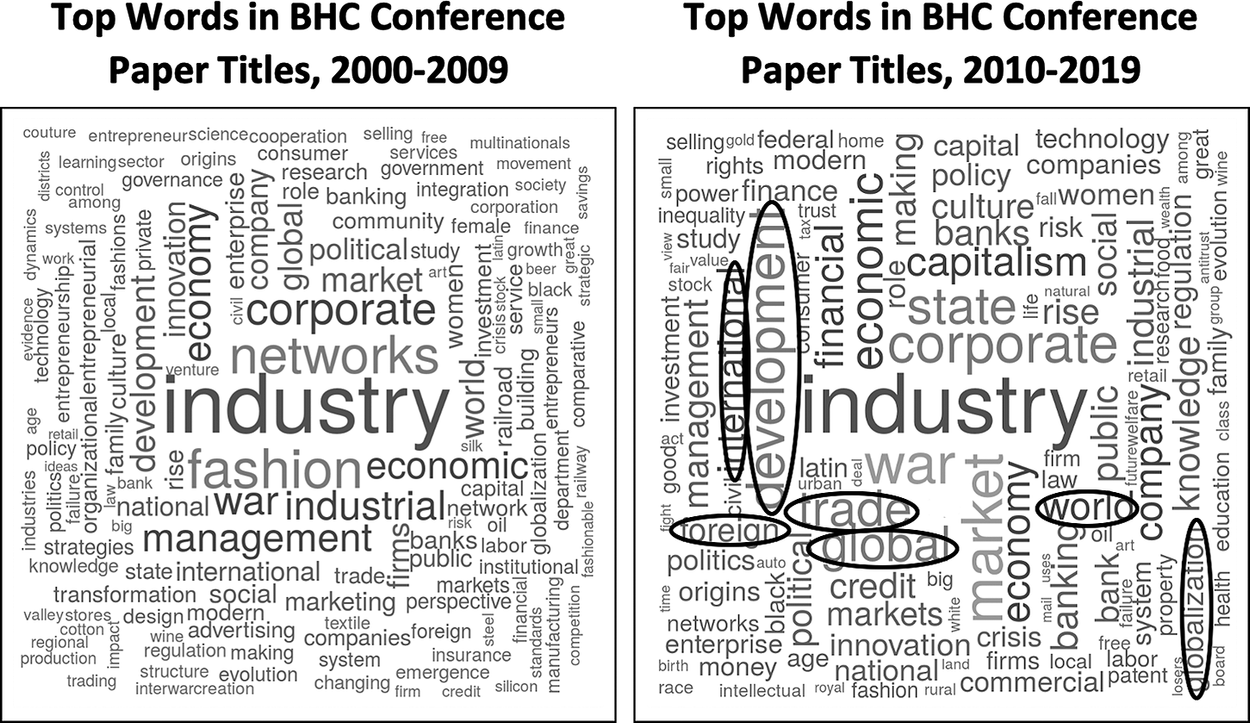

Of course, there was scholarship in business history during the 1970s and earlier that tackled other sorts of topics and problems. Indeed, in The Visible Hand Chandler provided some important analysis about smaller-scale and family-run firms up to 1860, the “traditional enterprise” that the modern industrial corporation would supplant after the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 10 But since the 1970s, a much greater number of business historians have ventured leftward and rightward along the “scale” axis, often investigating small and medium-sized businesses as well as business networks and even more diffuse but broader business environments. They have traversed up the vertical axis, more frequently examining the impacts of modern capitalism on the world beyond business, narrowly construed, as well as the role of political economy, society, and culture in constituting and transforming business enterprise, including state-owned and non-profit enterprise.Footnote 11 They have also extended their geographic reach, researching a much larger array of firms, whether operating locally or at a global scale, with a much larger fraction originating in what we now think of as the Global South.

This topical expansion (depicted in Figure 3) has left an appreciable footprint in BHC annual meeting programs. Since the BHC archives those programs on its website, one can scrape paper titles and input them into a database. After removal of a host of common “stopwords,” along with place names, chronologically based terms, and some other terms like “case” and “business” that offer little insight about analytical approach, one can generate word clouds that suggest collective thematic focus. Figure 4 provides a pair of such word clouds, the image on the left showing the most common thematic words in BHC conference paper titles from 2000-2009, and the image on the right showing the same over the subsequent decade.

Figure 3 The Expansion of Subjects in Business History since the 1970s.

Figure 4 Word Clouds of Most Common Terms in BHC Conference Papers, Aggregated over Decade Intervals.

One can see a powerful scholarly continuity here – lots of emphasis on corporate management and strategy in both decades. But during the most recent ten years, BHC conference participants have focused even more on the dynamics of globally-oriented business and economic development, more on the financial underpinnings of business communities and the history of financial crises, more on the role of the state in shaping the conditions for business activity and on the role of business in influencing the state, and more on the social and cultural dimensions of change in the business world. (See figures 5-8). For several decades, then, business history has become considerably more pluralistic, whether one considers the community’s motivating questions, methodological approaches, or subject matter.

Figure 5 Growth in focus on globalization in BHC Conference Papers, 2000-2019.

Figure 6 Growth in focus on finance and financial instability in BHC Conference Papers, 2000-2019.

Figure 7 Growth in Focus on Business-State Interactions in BHC Conference Papers, 2000-2019.

Figure 8 Growth in Focus on Social and Cultural Analyses in BHC Conference Papers, 2000-2019.

At the same time, one remains struck by the enduring paucity of scholarship among BHC-affiliated scholars that directly deploys the analytical lens of race. There are no shortage of important topics to consider, including: the significance of New World slavery as a mode of economic production and a shaper of business forms and culture; the enduring consequences of systemic racism for access to credit and business opportunities; the impact of racial solidarity on the formation of local business communities; the overhang of colonial structures on business networks throughout the Global South; the origins and impacts of efforts at redressing histories of racial injustice through anti-discrimination policies and efforts to promote diversity and inclusion within firms and other large institutions, like higher education. One can find each of these subjects in annual BHC meeting programs, business history journals, and business history monographs, as well as the scholarship of individuals receiving BHC prizes and commendations, especially in recent years.Footnote 12 Nonetheless, the collective footprint of this research, as indicated by Figure 8, remains noticeably small as a fraction of scholarship in business history. The historians exploring these themes have been much more likely to identify with other scholarly communities, such as the “History of Capitalism” group in the United States.Footnote 13 The recent instances of police violence toward black people, leading to the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many others, along with the remarkable social protests that they have generated across the United States and elsewhere, have highlighted the imperative of redoubled commitment to anti-racism in every walk of life. The BHC has much work to do on this score.

I would like to turn now to my second theme, laying out the case for more expansive engagement with collaborative research in business history. As a community, we have especially valued historical work carried out by individuals. There now have been twenty-six recipients or co-recipients of the Hagley Prize for the best book published in business history during the previous year, each written by a single author.Footnote 14 The BHC has now also awarded twelve Gomory Prizes for books that effectively probe “the effects of business enterprises on the economic conditions of the countries in which they operate.” Only one of the dozen awards has gone to a co-authored monograph.Footnote 15 Thumb through the volumes of business history journals, or more plausibly, these days, scan their digital tables of contents, and you will see primarily articles written by a single person.

Historians of business tend to go it alone, I think, for several reasons. Our introductions to historical research and writing, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, ask students to work on their own, and indeed often prohibit the sharing of key tasks. Opportunities for individual fellowships to support research and writing abound, even if they often are quite competitive. By contrast, there are far fewer channels to seek larger-scale grants, especially ones that specifically target business historians. For scholars working within the academy, and particularly within history departments in the United States, prevailing rubrics for assessing promotion cases also create powerful incentives to stay within the solitary lane. The path to tenure as a historian in a US university still runs through the peer-reviewed, single author monograph. The same goes for the road to full professor.Footnote 16

Business historians, of course, collaborate in many contexts, and have done so for decades. Every year the field produces a few edited volumes and a special journal issue or two that examine some cross-cutting theme. These undertakings reflect significant coordination, as an editor or co-editors secure funding, identify contributors, and often hold a conference for discussion and feedback on draft essays. Indeed, the University of Pennsylvania Press now frequently publishes edited volumes that emerge out of an annual fall conference at the Hagley Museum and Library in which participants examine some cultural lens on the business world.Footnote 17 Business historians also work together to organize and oversee monographic book series with academic presses, such as the Columbia University Press series on “Studies in the History of US Capitalism.”Footnote 18 At educational institutions with a particular commitment to business history, such as the Harvard Business School, the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, and the Copenhagen Business School, our colleagues run regular seminars and research centers that bring scholars together to discuss work-in-progress.Footnote 19 One can point as well to the collaborative website, “Organizational History Network,” that hosts a blog and furnishes a platform for disseminating scholarship about the history of organizations.Footnote 20

As with any scholarly society rooted at the juncture of the social sciences and the humanities, we have no more far-reaching and complex collaboration than the annual meeting. Every year, this undertaking requires scores of hours of work and coordination by the Program Committee, BHC officers and staff, Doctoral Colloquium faculty, trustees, and prize committees, as well as panel chairs and commentators. (And this year, because of the rapidly shifting policy responses to the novel coronavirus pandemic, there was an unusually demanding collective lift).

In the past twenty years, moreover, the frequency with which business historians collaborate around longer-term research endeavors has increased. Between 2000 and 2009, more than three of four articles published in the three main business history journals remained sole-authored; in Business History Review, that figure exceeded four in five, and in Enterprise & Society, nearly nine in ten. Business History selected a significantly higher fraction of multi-authored research – nearly 40%. During the most recent decade, each of these journals has published a significantly greater proportion of research undertaken and authored by more than one person. Between 2010 and 2019, the percentage of articles with more than one author increased to 17% in Enterprise & Society, 34% in Business History Review, and a full 50% in Business History. Aggregating the data, two in five articles had co-authors. In addition, the frequency of articles with more than two co-authors also more than doubled, from just 5% of all articles in the three journals in the 2000s, to 13% of all articles in the 2010s.

Intriguingly, there also been a noticeable change with regard to article-length collaborative research receiving commendation for excellence from the BHC. During the era of the Newcomen Prize, awarded from 1992 through 1999 to the best paper presented at the BHC annual meeting, only one of eight prizes went to a jointly written essay. And in the first dozen years of the current Scranton Prize for the best article in Enterprise & Society, every recipient was a single scholar. Since 2013, however, six of eight Scranton Prizes have gone to articles with co-authors.Footnote 21

One can also point to a number of multi-year research projects in business history that involve more expansive collaboration, incorporating multiple faculty members, sometimes postdocs, and often graduate students. At the Harvard Business School, for example, Geoffrey Jones and Tarun Khanna oversee the “Creating Emerging Markets” project. Jones implicitly articulated the case for this undertaking nearly two decades ago in his 2002 BHC presidential address, which called for much more attention to the role of firms in negotiating the evolving structure of transnational networks and global markets. “Creating Emerging Markets” seeks to redress the scantiness in many countries of archival holdings that provide evidence about the origin, evolution, and growth of key local businesses. Firms based in these societies have tended not to keep such records, and governmental archives often also provide spotty coverage at best. The solution to this problem has been a systematic attempt to conduct oral histories with entrepreneurs from the Global South.

Since 2007, and through a few different organizational models, Creating Emerging Markets has completed more than 140 interviews of business executives and business-affiliated non-governmental organizations (NGOs) from across Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Most interviewees reflect on several decades of experience, discussing the challenges that wider business environments posed and how they settled on entrepreneurial strategies to deal with those challenges. Transcripts of the interviews, along with biographical sketches and firm/organization overviews, are either posted online or available to researchers on request. The project has drawn on the networks, research, and interviewing skills of more than twenty Harvard faculty in HBS and across the university, as well as HBS postdocs and scholars based elsewhere.Footnote 22 It has also now provided the evidentiary backbone for comparative analysis that draws out common themes and strategies in the experience of Global South entrepreneurs, in every instance through co-authored writing. Topics here range from approaches to reputation-building, patterns in navigating business-state relations, and identification of executive communication styles (the latter deploying machine learning techniques of analyzing both text and facial expressions).Footnote 23

Creating Emerging Markets stands out in three interrelated respects – degree of ambition, longevity, and the capacity to draw on the resources of the Harvard Business School. But scholars elsewhere have tapped larger-scale grants, typically from government research agencies, to support multi-year, multi-scholar research in business history. A few illustrations suggest the sort of team-based research that is starting to become more common.

The “Trading Consequences” project ran from 2012 through 2015 with funding from British and Canadian public funding agencies, as well as an international funding consortium. This undertaking brought together economic geographers and a historian from two Canadian universities (York and Saskatchewan) with data scientists from two Scottish universities (St. Andrews and Edinburgh), and involved more than ten faculty as well as graduate students and undergraduates. The team scraped billions of words of text from newspapers, trade journals, and other digitized primary sources, and then applied text mining methods to trace the flows of over 2000 commodities into, across, and out of Canada. In addition to scholarly publications, mostly about text mining methods, the group has created a web interface that allows users to create visualizations that trace the evolution of spatial commodity flows from year to year.Footnote 24

In Switzerland, a smaller team led by historian Carlo Eduardo Altamura has begun a four-year project, “Business with the Devil? Assessing the Financial Dimensions of Authoritarian Regimes in Latin America, 1973-1985.” Altamura, along with a postdoctoral fellow and eventually a doctoral student, will be examining the role of international financial institutions and European banks in facilitating the economic agendas of military or otherwise undemocratic governments in countries such as Chile, Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico during the 1970s and 1980s. Funded by a long-term grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation, this team will be pursuing more traditional research methods, digging into newly opened European banking archives.Footnote 25

A final illustration comes from the United Kingdom, where a group of cultural studies scholars and historians from four separate universities have received significant financial support from the British Economic and Social Research Council to examine the evolution of financial advice over several centuries. Prompted by the economic and cultural fall-out from the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, this team is examining the genre of financial advice in the United Kingdom and North America from the South Sea Bubble through to the twenty-first century. In addition to a research agenda that focuses on analysis of texts produced at times of significant financial stress, these scholars have developed a MOOC, “Understanding Money: A History of Finance, Speculation, and the Stock Market,” and also curated a related set of educational resources for school teachers.Footnote 26

One could multiply such examples from current studies being funded by national research agencies in Japan, Germany, France, or Latin American countries. Collaborative research about the history of business, then, is on the rise. And it shows particular promise in the kind of research contexts that I have just described:

-

• exploration of entrepreneurial action, the transmission of business culture, or the influence of political economy on the business environment, especially across the boundaries of political sovereignty and language, where one cannot expect a single scholar to develop expertise in so many different contexts;

-

• the creation of crucial new sources of important evidence about one or another domain of business history through oral history projects, where teams are so well suited to selecting interviewees, completing background research, conducting interviews, and making the documentary record available; and

-

• the use of data science techniques to probe truly enormous masses of historical evidence, where business historians would do well to work closely with statisticians, computer scientists, and applied mathematicians.Footnote 27

These research arenas, I wish to highlight, also significantly overlap with the expansion of topics in business history that we have seen over the past two to three decades.

At the same time, we should remain mindful that collaborative research in business history has gained most purchase among scholars working in institutional contexts especially conducive to team-based research – that is, academics working in business schools or economics departments. Let’s return for a moment to multi-authored articles in the three major business history journals since 2000, and consider who engages in this sort of research.

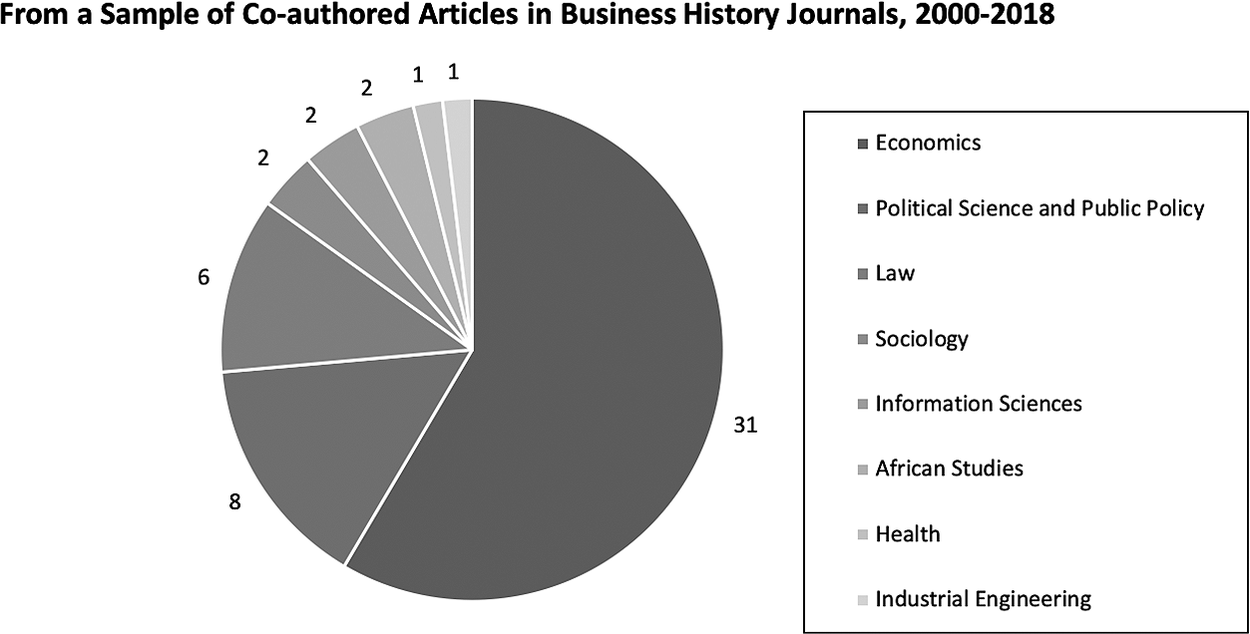

On the basis of a sample of those articles (jointly-authored essays published in 2002, 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018), just under 40% included at least one author with a faculty appointment in a history department, while nearly two-thirds had at least one author with a faculty position in a business school. This collection of more than 120 articles also included fifty-three authors whose training or appointments were outside of history and business. As Figure 9 illustrates, economists predominate here, joined by some political scientists and scholars of public policy, with a smattering of other disciplinary backgrounds.

Figure 9 Breakdown of Collaborative Authorship by Discipline, other than History or Business/Management.

I doubt these results come as a significant surprise to most business historians. Schools of management and economics departments have long recognized and encouraged collaborative research, far more so than typical history departments. Intriguingly, the overall group of authors in the sample included only six graduate students, five at the doctoral level – and only two history students, who worked as a pair on one essay. There were far more research fellows and postdocs included as co-authors, most often based in European universities.Footnote 28

The current pattern of collaboration in business history underscores the individualistic premises of how business historians in history departments tend to teach students at all levels, from the undergraduate survey to the doctoral seminar. Those of us who hold faculty appointments in history departments have primary responsibility for recruiting talented young people into our field. And we overwhelmingly still assign sole-authored historiographic essays and research papers in our graduate-level seminars. We no doubt do so in part because those were the assignments that we completed, but also because they serve important purposes. At all levels, we have clarity about how to assess that kind of student work, which does not raise the conundrum of how to tease out individual contributions to group endeavors. At the PhD level, we further assume students need to carve out their own intellectual niche. From that premise follows a host of other priorities – that graduate work in business history should hone each student’s capacity to construct a distinctive research agenda, undertake the long slog of archival and other investigation, and translate a massive array of evidence into a compelling analytical narrative.

This approach has a decades-long track record. For Ph.D. students who desire an academic career, it cultivates the sort of research output that has been crucial, again for decades, as a means of convincing search committees in history departments to take applications for tenure-track positions seriously, and then for compiling a compelling tenure dossier. But this way of training the next generation of business historians also places a powerful constraint on building a deeper, wider culture of collaborative research. It socializes doctoral students into building their own intellectual brand. At the same time, it keeps them from learning how to work effectively on projects with others – how to engage in constructive collective decision-making and mediate differences of opinion about research priorities or interpretation of findings; how to live up to one’s responsibilities for a joint undertaking; how to communicate well with collaborators who possess different methodological inclinations or epistemological assumptions. Sustained experience of this sort generates an ever more useful set of skills within academia, and stand out as essential to thriving in career trajectories outside the realm of higher education.Footnote 29

What then to do? My full list of suggestions would include rethinking tenure standards to give much more weight to collaborative research and reconstructing the slate of social science and humanities funding opportunities offered by foundations and government research agencies. Such changes would alter the core incentives confronted by scholars in our field, but face significant obstacles. For the moment, I’d like to focus on opportunities to bring more open open-ended, team-based inquiry into the classroom, for undergraduates and graduate students alike. Doing so, of course, raises significant challenges as well.

In light of the limited experience that most of us have with this pedagogical approach, many university-based business historians will need to figure out how to provide appropriate scaffolding for collaborative research assignments. How should one shape team formation? How might one identify students who possess varying technical skills and intellectual backgrounds, especially for research that lends itself to interdisciplinary methods? What’s the best approach to facilitate cooperative decision-making? To what extent should one set parameters for the choice of topics and methods, and guide the process of settling on organizing research questions and divvying up work responsibilities? How does one avoid the free rider problem that so often hamstrings curricular group projects? What is the best approach to mentoring teams as they pursue research and then conceptualize and create research outputs?

One obvious place to look for guidance with regard to these questions is the laboratory sciences. For decades, as business historians who focus on the evolution of research and development know well, scientific inquiry has proceeded on a collaborative basis. In addition to a faculty member who serves as a principle investigator, a productive university lab often incorporates postdocs, PhD students, and undergraduates. Younger members of the team spend time learning relevant investigative techniques and getting a handle on the lab’s broader research priorities before constructing their own experiments, which almost always connect to that wider agenda. Extensive informal interaction and mentoring occurs among lab members on a daily basis, but there are also regular (often weekly) meetings to discuss the implications of research findings, engage in collective trouble-shooting, and identify promising new experimental directions.

Over the past decade, moreover, a growing number of scientists and social scientists have begun investigating the social practices and organizational culture that foster especially effective scientific research, especially involving interdisciplinary inquiry. The dialogue among these scholars has increasingly occurred through the auspices of the International Network on the Science of Team Science (inSciTS), and has pinpointed some principles that likely have more general application beyond the sciences. Among the key themes:

-

1) Members of an interdisciplinary team need to take the time to find common language and translate more field-specific concepts.

-

2) Explicit articulation of roles and responsibilities improves accountability.

-

3) A dedicated project manager can provide crucial coordination of different activities, facilitate communication among team members, and sustain momentum, especially when the work of one group depends on inputs from another group.

-

4) In the case of more complicated research, a sub-team structure can often improve mentoring and furnish less experienced team members with a clearer sense of how to contribute.Footnote 30

At Duke University, we have also been working through such questions about organizing collaborative research for several years, especially through a university-wide program, Bass Connections, that funds and supports year-long interdisciplinary research projects. (Full disclosure – as Duke Vice Provost for Interdisciplinary Studies, I have responsibility for overseeing this program). Bass Connections project teams bring together faculty, graduate and professional students, and undergraduates, often in partnership with entities outside the University, such as community organizations, government agencies, or firms. Those teams spend at least a year working together on a research project framed by some significant societal problem or challenge. More recently, we have been focusing on how to help faculty develop more semester-long courses that incorporate collaborative research projects as a key component of student experience.Footnote 31 In essence, we have been experimenting with how to bring collaborative arrangements, which have become such a touchstone for corporations, other large organizations in the public and non-profit sectors, and smaller firms alike, into educational practices within academia.Footnote 32

A sketch of a specific research team can flesh out what such an endeavor entails – significant attention to logistics and team dynamics. During the 2019-20 academic year, I co-led a year-long project team, “American Predatory Lending and the Global Financial Crisis,” along with Lee Reiners of the Duke Law School, Joseph Smith, former North Carolina Commissioner of Banks, and Debbie Goldstein, who until recently was Vice-President of the Center for Responsible Lending, a policy organization based in Durham. Our team also consisted of thirteen undergraduates – with majors (or intended majors) that range from history, public policy, economics, philosophy, and sociology to statistics, computer science, and electrical and computer engineering – and five graduate and professional students, pursuing degrees in public policy, business administration, law, interdisciplinary data science, and history. With a few exceptions, the students participated for course credit. Most of the students were from Duke, but two were from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, and one PhD student from the City University of New York served as a consultant on oral history techniques. Figure 10 depicts most of our group during one of our weekly team meetings.

Figure 10 Most of Duke’s American Predatory Lending and the Global Financial Crisis Team. From left to right: Joseph Smith, Michael Cai, Callie Naughton, Kate Karstens, Hayley Lawrence, Ahana Sen, Kate Coulter, Cam Polo, Charlie Zong, Andrew Carlins, Sean Nguyen, Despina Chouliara, Jessie Xu, and Lee Reiners. Not pictured: Edward Balleisen, Debbie Goldstein, Erin Cully, Jett Hollister, Joe Edwards, and Maria Paz Rios.

Throughout the year, our team investigated the residential mortgage market in North Carolina during the run-up to the financial crisis. We organized this effort around a series of sub-teams, each with student leads (either a graduate or professional student alone, or paired with an advanced undergraduate). One sub-team has been analyzing a range of statistical datasets about mortgage activity in the 2000s, including the disposition of applications for different kinds of loans, loan delinquencies, and enforcement actions by the North Carolina government against mortgage brokers deemed to have violated relevant state regulations. A second sub-team has been preparing for and conducting oral histories with individuals who have helped to shape the state-level policy environment for residential mortgage-lending – chiefly former members of the state legislature who passed relevant statutes like the 1999 North Carolina Predatory Lending Act, representatives of the banking industry and consumer-focused NGOs, who helped to shape the legislation, and state-level regulators. A third sub-team has delved into the legislative framework for the residential mortgage market both at the national level and in North Carolina, producing a series of policy memos about key pieces of legislation.

As in formal work contexts, our collaboration constituted a process first and foremost. The year began with some general introductions to our subject matter – the evolution of American mortgage markets; the nature of available data on those markets in North Carolina; best practices in oral history interviewing – and so did not diverge too much from a typical course. But after the first month, sub-teams fashioned detailed project plans and began meeting separately each week to track progress on individual tasks and engage in trouble-shooting. (In the case of the oral history sub-team, key early activities included settling on some standard questions for different types of interviewees as well as an interview protocol, getting both approved by Duke’s Institutional Review Board, identifying likely targets for interviews, and developing expectations around pre-interview biographical research.) By the second half of the fall semester the sub-teams had transitioned into more research and analysis, with larger team meetings revolving around reports from the sub-teams and discussion of any issues about research priorities or methods. In the spring term, despite disruptions caused by COVID-19 and a transition to remote interaction, each sub-team was able to make good progress on their specific projects. Team meetings mostly involved presentations of work in progress and provision of feedback. With the ability to draw on the editorial capacities of sub-team leads and multiple faculty leads, we also instituted multiple levels of review before any oral history transcript, data visualization, or policy memo received the go-ahead for inclusion on a team website, which was designed and populated by yet another student sub-team. Interested readers can now find these outputs at http://predatorylending.duke.edu.

Our team will continue in the 2020-21 academic year, with a few returning and many new students who have equally diverse intellectual interests. In addition to digging in more deeply to regional variations in the North Carolina mortgage data, we intend, if we can, to expand our interviews to North Carolina mortgage brokers, real estate appraisers, and borrowers. Other goals include probing the market dynamics in other states like Florida and Arizona that experienced more pronounced housing booms and busts, conducting oral histories of policy protagonists in those states, doing text mining of our oral histories and possibly related public testimonies, producing overviews of the structural changes within the residential mortgage market since the 1980s, and developing a set of historically informed policy recommendations. I suspect that more traditional scholarly publications will also emerge from our efforts – in each case with multiple co-authors.

The specific configurations of this year-long research team will not work so easily in other universities. Duke has developed a robust infrastructure to facilitate such teams, including assistance with connecting faculty around team ideas, peer review of proposed teams, mechanisms for matching students to specific projects, onboarding of faculty leads, training for graduate student project managers, extensive resources about how to organize and grade collaborative research of this type, and much else besides, including funding to facilitate research.Footnote 33 But I urge my fellow business historians who have faculty positions to give some thought about how to build collaborative research into their core teaching responsibilities. Keep in mind that we have comparative advantage in thinking about the nature and evolution of organizational innovation, since we study and write about it in so many different historical contexts.

How might we fold a collaborative research project into an undergraduate course offering?Footnote 34 How might we design PhD seminars or historically-focused business school classes around truly collaborative projects, rather than just shared secondary readings or discussion of individual research paper drafts?Footnote 35 Where might we find opportunities to collaborate with students on intensive research that leads to co-authorship with them? With regard to this last query, any effort by historians to engage in sophisticated text mining or other techniques of data science will benefit greatly from interdisciplinary partnerships, and students, even undergraduates these days, have a great deal to offer us.

Collaborative research, of course, hardly constitutes a magic bullet for business history. Collaborations can and do fail, especially when participants do not see eye to eye about research direction, have not already developed strong working relationships so as to manage conflicts constructively, or have radically different levels of commitment to the project at hand. In Europe, the growing expectation that grant proposals will incorporate not just multiple collaborators, but also investigators from multiple countries, has sometimes occasioned frustration precisely because jerry-rigged proposals have a higher likelihood of running into these problems.Footnote 36 Individual research, moreover, still has much to recommend it, including the scope that it offers for truly innovative, iconoclastic inquiry. It will surely remain a key mode of scholarship within the field of business history, the discipline of history, and the wider social sciences.

I would be inclined to frame the issue before us as a question of intellectual portfolio construction. Does our field sufficiently foster collaborative inquiry as a component of our research and pedagogical practice? My answer to that question is that it does not. If enough of us with faculty positions think deeply about how to meld at least some of our teaching and research around a collaborative framework, I am convinced our field will greatly benefit. Collectively, we will have greater capacity to take advantage of larger-scale grant opportunities and tackle important research frontiers; we will recognize more opportunities to join forces with faculty from other disciplines; and we will be more effective in bringing our expertise to bear on debates that matter outside of our field. Our doctoral students will also widen their potential career trajectories, since employers in so many fields now prize the ability to work cohesively in a team. For a few decades now, business history has been steadily embracing a greater degree of collaborative inquiry; it’s time for us to put collective thinking and organizational endeavor toward accelerating that process.