Introduction

Recent research into the development of management education has challenged the interpretation of U.S. international influence on national institutions as regards educating and developing business managers after World War II. The extension of the geographic focus of research from the dominating U.S.–Western European perspective to including the development of management education in underdeveloped regions, some nowadays called “emerging markets,” such as Brazil, Mexico, Dubai, and India, has shown that there is a need to rethink the way we understand the global history of post–World War II management education.Footnote 1

We respond to the call for more research by exploring how new institutions for executive education developed from the 1950s to the 1970s, by analyzing four Latin American cases, one including six Central American nations, one in Peru, and two in Colombia.Footnote 2 We introduce two perspectives for this purpose. The first perspective involves focusing on the development of executive education, understood as short, intensive programs, typically from three to fifteen weeks long, meant for people intending to achieve higher management positions. Recruitment to executive programs is typically based on the participant’s position in corporate hierarchies, and not on any previous grades or entrance exams, and the programs award diplomas rather than degrees based on exams.Footnote 3 When the war ended, executive education was offered as a new educational concept in the United States, and soon it developed to a powerful key instrument for creating new institutions for management education in different parts of the world. In a postwar context, when U.S. capitalism was offered as a role model for economic development, executive education programs were increasingly offered in Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America, often as the first and only programs in business schools that later became graduate business schools. After the 1960s, executive education had become a global phenomenon as regards the development of managers aiming to reach higher management positions, and such programs were offered in more than 40 countries, including most Latin American countries.Footnote 4 The programs were typically grouped by the business schools as top management and middle management programs, depending on which part of the corporate hierarchy the participants aspired to.Footnote 5 In this article, we use the business schools’ own categorizations, but are aware that, for example, top management programs often enrolled participants who were far from any top management position.Footnote 6

The second perspective draws upon research that studies the development of management education and management theories in the context of Americanization and the Cold War.Footnote 7 In Latin America, executive education emerged within the geopolitical Cold War context of an unequal relationship between the United States and Latin America characterized by concepts such as business imperialism, developmentalism, decolonization, nationalism, military aid, anti-Communism, insurgent leftist movements, and military dictatorships. This was undoubtedly part of the Americanization process, which was critically studied during the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 8 In this article, we study three different U.S. institutions that contributed to spreading American ideas about executive education in Latin America: the U.S. government represented by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the Ford Foundation as representative for big U.S. foundations, and the Harvard Business School (HBS) and the Stanford Graduate School of Business (Stanford) as representatives for U.S. business schools. In some cases, these actors had different motives for, and views on, being involved in Latin America. Complementarily, we account for the differences in the roles played by local actors (elite networks, universities, and government) across contexts in developing executive education. These perspectives add a new dimension to the expanding literature on the history of management education in Latin America.Footnote 9

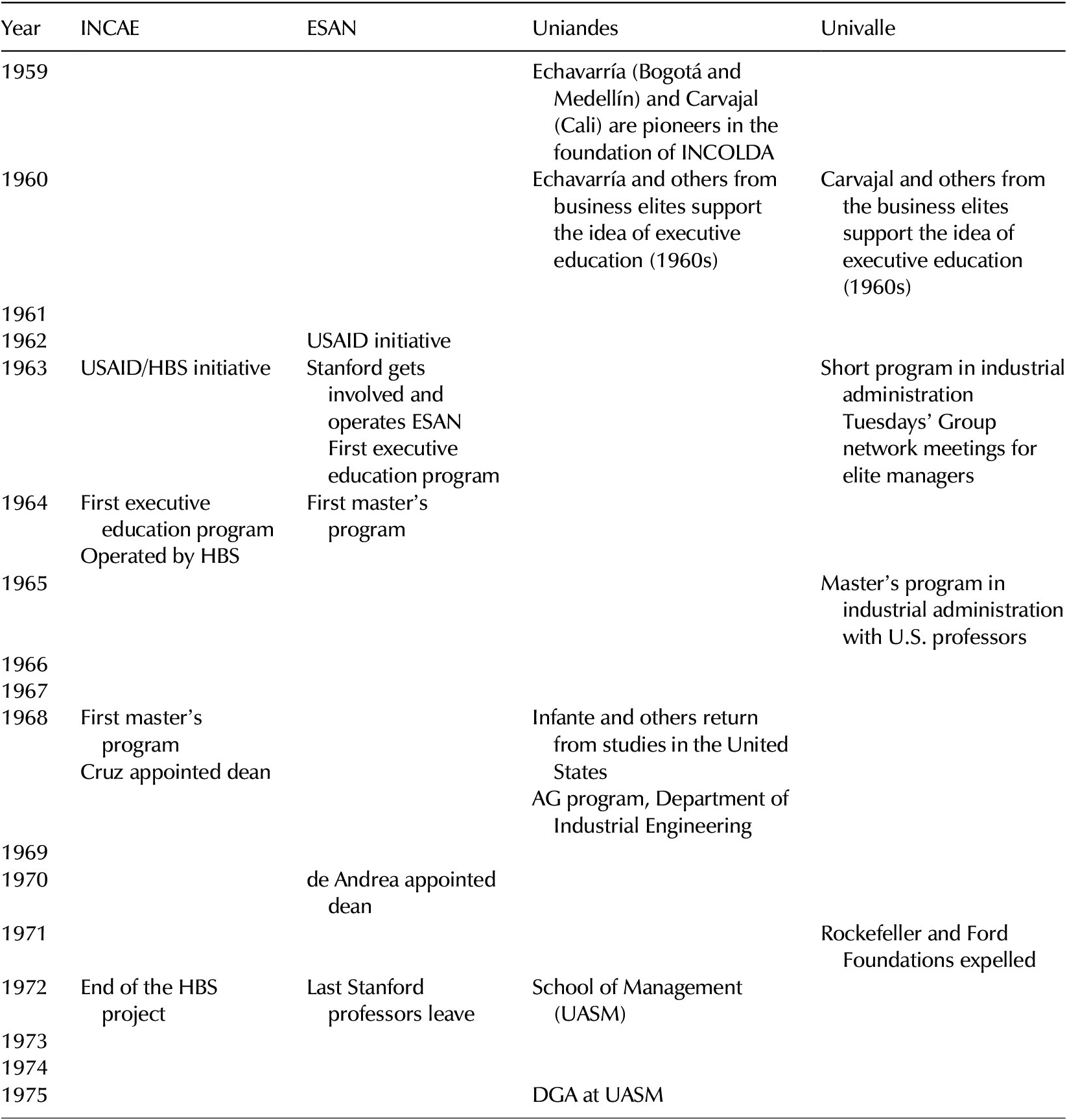

We explore four cases of developing executive education in Latin America, the creation of the Instituto Centroamericano de Administración de Empresas (INCAE) in Central America and the Escuela en Administración de Negocios para Graduados (ESAN) in Peru in 1963; and the development of executive education in two different settings in Colombia, the capital Bogota and the third largest city, Cali. We address the following questions: To what extent were new institutions that focused on executive education the result of an Americanization process, and to what extent did they resonate with the actors and initiatives that reflected different national contexts? These questions require an examination of the role of three key U.S. institutions—the U.S. government, the foundations, and the business schools—as well as local actors, and especially business communities, governmental institutions, and university systems.

Central America, Peru, and Colombia were chosen because they involved different balances between the influence of the United States and local actors. In Central America, HBS and USAID initiated INCAE with the purpose of operating in six countries under its first headquarters in Nicaragua (1964).Footnote 10 In practice, HBS operated the new school for many years by sending faculty members to INCAE.Footnote 11 In Peru, Stanford and USAID strongly supported the development of ESAN (1963), and representatives from Stanford operated the school for some years.Footnote 12 The strong position of HBS and Stanford in these two cases makes them good examples of how U.S. business schools were actively involved in the process. In Colombia, however, local actors played a much more active role in the institutional formation of executive education.

Regarding sources, we developed a research strategy that would allow us to achieve the aim of researching the complex interactions between different U.S. and local actors in different contexts manageable within the framework of an article. First, we visited the archives of the key U.S. institutions involved in the process. In addition to the Ford Foundation and USAID’s archives, we undertook research in the archives of HBS and Stanford, which prior information had suggested were highly relevant U.S. business schools (see Tables 1 and 2). We searched for all documents that matched the keywords “management” or “executive education” and the three geographic areas. The documents, which are stored in different archival series, including correspondence, minutes from meetings, grants, projects, and reports, were all studied in detail. The U.S. archives also included documents produced by local Latin American actors, and several of the founding documents of INCAE are available online.Footnote 13 Archival documents in Colombia were also studied.Footnote 14 Second, we included information from books, articles, and reports as secondary sources. Third, we checked and expanded on the information from the archives and secondary sources using interviews and personal communications.Footnote 15 The authors both conducted interviews with people who had held top management positions at Uniandes, Bogota, from the very beginning of executive education.Footnote 16 We also draw upon on long personal e-mail communication with one of the U.S. faculty members who worked at ESAN from 1972 to 1980 and later worked for the Ford Foundation.Footnote 17

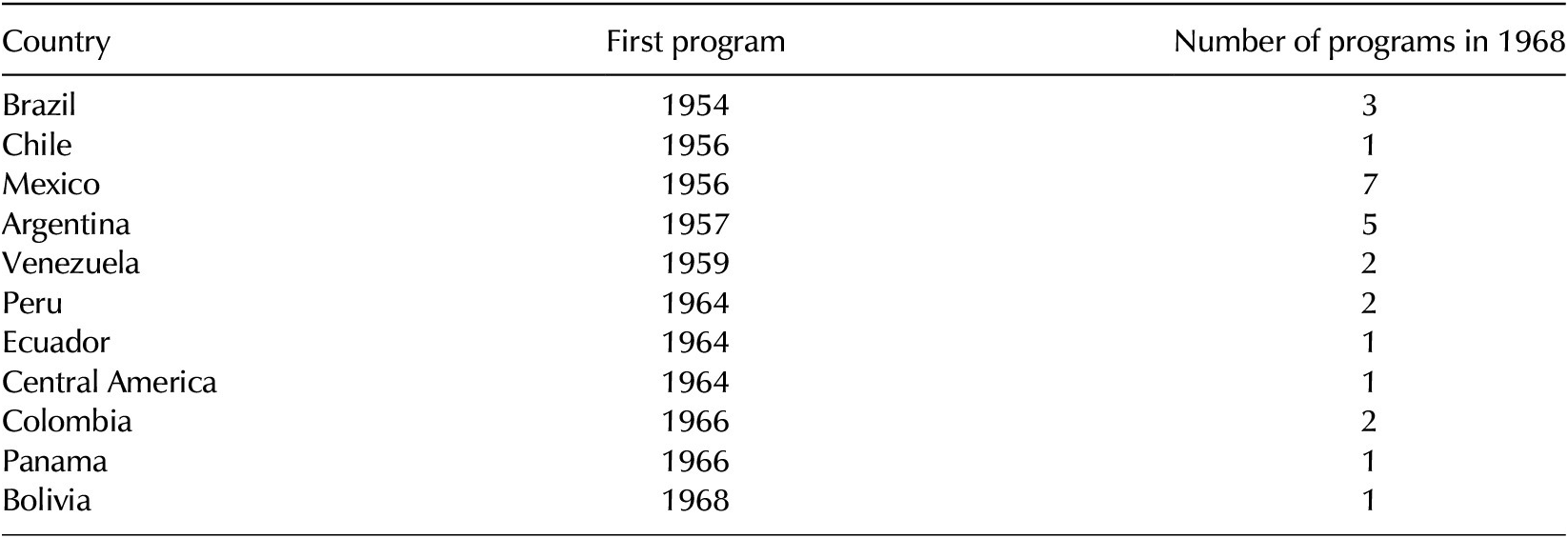

Table 1. Executive education programs in Latin America, 1968

Note: Executive education consists of programs in general management for people in, or close to, executive positions, lasting for at least three weeks, full-time (or equivalent).

Source: Based on an inventory of all known executive programs in the world in 1968, in McNulty, Training Managers.

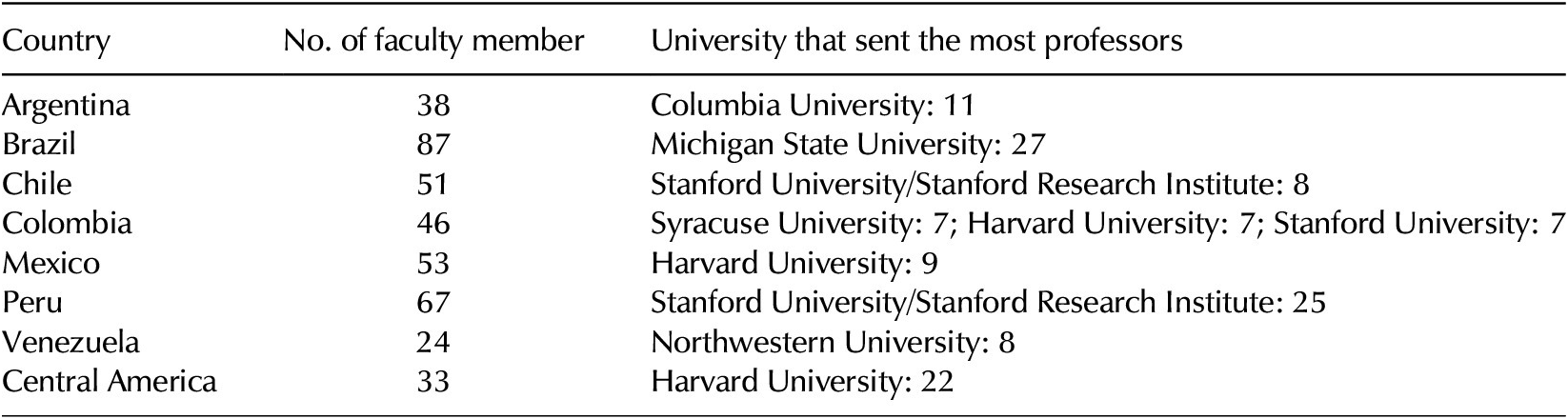

Table 2. Faculty members from U.S. universities who taught business administration in Latin American countries, 1945–1966

Note: The total number of professors and other academic experts in business administration from 88 U.S. universities/business schools visiting Latin America in this period was 357. Some visited more than one country. Fewer than 20 U.S. professors visited the other Latin American countries for purposes of teaching business administration.

Source: Towl and Hetherston, Bibliography.

We are aware that our sources may be biased. Archival sources are often organized to serve purposes other than those of researchers, and they can suffer from “silence,” such as the absence of key sources as a result of how archives have been collected, organized, and stored.Footnote 18 Especially in emerging markets, the archival situation has been characterized as unsatisfactory in terms of scope, availability, and organization compared with advanced economies, which involves creativity in the approach to sources.Footnote 19 Seasoned historians may find that such limitations are not insurmountable.Footnote 20 Due to the stronger role of U.S. business schools and USAID in pushing the idea of establishing INCAE and ESAN than in the Colombian cases, more local sources are used in the Colombian cases in this article. Rather than generalizing the Latin American history of executive education, we therefore explore selected contexts within a continent, without ignoring internal differences.

This article contributes to three discussions within the business history literature. First, it contributes to the literature on the history of management education, which has focused almost exclusively on the development of degree-granting activities within business schools, by researching the development of executive education.Footnote 21 Second, the article contributes to the literature on Americanization in management education by studying how three different types of actors—the U.S. government, U.S. foundations, and U.S. business schools—worked in parallel to increase the impact of American ideas on management education in Latin America. Third, the article contributes to the alternative business history literature, which argues that some of the generally shared knowledge in business history needs to be revised based on research into business in emerging markets.Footnote 22 Many Latin American countries experienced political and macroeconomic instability, perennial income inequality, and high levels of poverty, as well an increasingly interventionist, active U.S. policy based on modernization theories through institutions such as the Alliance for Progress.Footnote 23 These are just some of many factors that trigger a rethinking of perceptions and interpretations based on the dominant U.S.–European-centric perspective within this field.

The article is structured as follows. First, we discuss the concept of Americanization and the roles and policies of the U.S. actors involved in this process before we present the cases of INCAE and ESAN and the two Colombian cases Then, we draw our conclusions.

Americanization and the Latin American Context

From a global perspective, the growth of executive education after World War II was part of a broader phenomenon of American influence within organizations, management, and education. Research into the history of management education has characterized this phenomenon as an example of Americanization, understood as the process of transferring practices or models from the United States to other countries, involving processes of translation, selection, adoption, and/or hybridization in different national contexts.Footnote 24 Research into Latin America in particular characterizes these efforts as an expression of American imperialism, trying to impose models and ideas based on new modernization theories, and the assumption that the Latin American elite was anti-entrepreneurial.Footnote 25 The need for more research into the impact of Americanization in different contexts has been clearly addressed,Footnote 26 but there has been less focus on studying the complexity of the relationship between the different U.S. actors in the Americanization of management education: U.S. business schools, U.S. governmental institutions, and big U.S. foundations.

In many Latin American countries, U.S. business schools played an important role in developing business education in general, and executive education in particular. Twenty-six executive education programs were established in Latin American countries between 1954, when the Sao Paulo Business School launched its Executive Development Program, and 1968, often in close cooperation with U.S. business schools (see Table 1). Another example of U.S. influence is the large number of U.S. business school faculty members who visited Latin America to teach. A survey conducted in 1966 reported that 357 U.S. business school faculty members had visited a Latin American country to teach after World War II (see Table 2). The survey also indicates a high degree of specialization among the U.S. business schools, with some strongly represented in specific countries: Columbia University in Argentina, Michigan State University in Brazil, Stanford in Peru, and HBS in Central America.

In the broader context, HBS and Stanford represented different models of U.S. business education in the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote 27 Stanford was among the role models for developing business schools based on academic knowledge by introducing statistics, mathematics, organizational behavior, and economics into management education, whereas HBS represented a more practical model by defending case-based teaching. In executive education, HBS launched its Advanced Management Program in 1945 as a forum in which to discuss, reflect on, and be socialized into the management profession.Footnote 28 This also colored its global activities. In 1968, HBS’s external magazine summarized the international achievements of executive education, expressing a motive for international expansion:

The School has responded actively to global appeals to share what some have called the “management” revolution deriving from the steady advances in administrative skills achieved in the United States over the past half century.Footnote 29

Both Stanford and HBS developed their international networks proactively. In 1959, HBS’s new committee on the school’s international activity argued that HBS should prioritize cooperation with institutions in Latin America and India. India was mentioned because it was “the most important free country of Asia.”Footnote 30 The Ford Foundation had also decided to prioritize India.Footnote 31 Mexico was noted as the most important Latin American country, as there were already plans for cooperation with Instituto Mexicano de Administración de Negocios (IMAN), and the Ford Foundation was considering supporting this initiative.Footnote 32 The chairman of the committee, Lincoln Gordon, one of the first two professors of international business at HBS and later U.S. ambassador to Brazil, argued strongly for Mexico.Footnote 33 The other international business professor at HBS, Raymond Vernon, was sent to Mexico in 1960 to undertake research and explore the executive training market.Footnote 34

In 1958, HBS set up a one-year International Teacher Program (ITP) to train teachers from countries other than the United States to teach in their home countries. This program strengthened HBS’s networks in Latin America. By 1965, more than two hundred people had participated, of whom fifteen were from the Sao Paolo School of Business in Brazil, nine from INCAE in Central America, and five from the Catholic University of Valparaiso, Chile. The backgrounds of the participants varied. Few had a PhD, and many even lacked an MBA.Footnote 35 Stanford’s equivalent to HBS’s ITP was the International Center for the Advancement of Management Education (ICAME) program, a one-year program set up in 1962 to train candidates from developing countries to teach business administration. While HBS’s ITP focused on general management and case teaching, the ICAME program focused on specific disciplines. The first class (1963) gathered 38 candidates in finance from 30 countries, of whom Brazil and Colombia sent three each; Mexico and Chile, two each; and Argentina, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Peru, and Venezuela, one each.Footnote 36 Stanford offered a marketing class in 1963–64 and classes in the management of human relations and in production management in the following years.Footnote 37 From 1962 to 1967, the courses had 157 participants, of whom 68 were from Latin America.Footnote 38

The U.S. government’s support for educational projects in Latin America was motivated by the geopolitical context. In the postwar global landscape, having influence in Latin American countries, several of which were characterized by political and economic instability, became a major issue. The U.S. government strengthened diplomatic relations with several countries in the late 1950s under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, and in 1961, President John F. Kennedy launched a ten-year plan—the Alliance for Progress—with the declared aim of strengthening democracy and economic and social development in Latin America. The Alliance for Progress was propelled by the Cuban Revolution of 1959 and the concern for the spread of Communism through Central and South America.Footnote 39 In 1961, President Kennedy also reorganized U.S. foreign relations institutions and established USAID with a strong focus on Latin America.Footnote 40 Educational projects played a major role in USAID’s work; for example, 21 percent of the US$79 million budget for Latin America went to educational projects in 1965.Footnote 41 The focus of the USAID projects varied from one country to another, however, and to some extent reflected the way that USAID’s local missions defined the main challenges in each country. The projects covered all levels of the educational system, from primary education to university. Only a small minority mentioned business education in particular. A relatively small number of executive programs, often hidden in USAID’s list of projects as industry and mining projects, were supported.

The third key actor in the institutional complex that pushed U.S. business education, including executive education, to Latin America, was the Ford Foundation. In addition to supporting the scientification of U.S. business schools in the 1950s and 1960s, the foundation contributed to developing management education outside the United States with several grants.Footnote 42 For example, programs for training foreign teachers of business administration at HBS and Stanford were all financed by the Ford Foundation.Footnote 43 From the mid-1950s, the foundation increased the focus on Latin American countries, which coincided with the U.S. government’s increasing concern about the development of Central and South America.Footnote 44 The United States was also strongly represented in Latin America by multinational enterprises (MNEs) for a long period.Footnote 45 Studies of management education in Europe show that American MNEs in the 1950s and 1960s contributed to shape executive programs at two Swiss business schools, Institut pour l’Étude des Méthodes de Direction de l’Entreprise (IMEDE) and Centre d’Etudes Industrielles (CEI).Footnote 46 In our sources, the MNEs are mentioned unsystematically. Therefore, we refrained from studying the role of MNEs in this context and mention them as a topic for further studies.

We analyze the interaction between U.S. influence and indigenous influences, noting the political context of Latin America in creating institutions for executive education. We particularly consider the geopolitical tensions linked to phenomena such as the Cold War, U.S. foreign policy on Latin America, the Cuban Revolution, modernization theory ideas, and political instability. Beyond the surface of the process of interaction between the United States and local actors, we can see that the strength and character of the U.S. influence, the impact of different national actors, and the interplay among all the actors involved varied substantially from one context to another.

INCAE in Central America

On July 1, 1964, forty-four men and one woman met in Antigua, Guatemala, for a six-week Advanced Management Program offered for the first time by INCAE. INCAE was unique in that the new business school involved not only one, but six Central American countries. In the first group from 1964, there were ten participants from Guatemala, ten from Nicaragua, eight from El Salvador, eight from Panama, five from Honduras, and four from Costa Rica. The program was replicated in Panama and El Salvador in 1965 and in Costa Rica in 1966. In October 1966, INCAE established an office in Managua, Nicaragua, and started to build a campus in Managua.Footnote 47

INCAE was an U.S. initiative with USAID and HBS as the main actors. The purpose was to develop a business school covering Central America as one region. United States’ governmental organizations had been active in Central America since the 1950s to support management training and education. From 1955 to 1961, the United States sponsored 661 persons from Guatemala alone to go to the United States for education and training, of whom a minority were trained in management.Footnote 48 Some of these were selected by the Productivity Center in Guatemala, established in 1954 and supported by U.S. grants to offer management development courses.Footnote 49 In 1961, USAID’s office in Guatemala observed an “increased interest in industrial management training” in Central America and met this interest by supporting regional managers to participate in short programs for top and middle managers at the business schools of Columbia University, Harvard University, Pennsylvania State University, the University of Pittsburgh, and Syracuse University.Footnote 50 In 1962, USAID even planned to set up its own executive programs in Puerto Rico, Mexico, Guatemala, and Costa Rica, combining local sessions with visits to the United States.Footnote 51 In the same year, USAID recruited participants from Guatemala, Nicaragua, Colombia, and Ecuador to participate in an executive program at the Monterey Productivity Center in Mexico, taught by William Caldwell from Penn State.Footnote 52 USAID also supported a management training program for young leaders in Central America organized by Loyola University in New Orleans.Footnote 53 From 1964 to 1967, the Loyola program had four hundred participants, including sixty-six women, from Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and the Dominican Republic.Footnote 54

HBS was one of the business schools that received Central American managers for training before it became strongly involved in establishing INCAE.Footnote 55 While USAID provided the funding grant, HBS planned and operated INCAE in the founding period. The story of INCAE’s founding is the story of how HBS’s vision to train professional managers for top management positions went hand in hand with the U.S. government’s geopolitical ambitions. The Ford Foundation’s role was in this case more marginal, as it first became involved with a grant to INCAE in 1972 to undertake research into family planning management.Footnote 56

There was, indeed, close cooperation between HBS and the U.S. government, but there were also tensions. This is illustrated in two different narratives about the role of HBS in founding INCAE. The dominating narrative about the birth of INCAE emphasizes the geopolitical motive, and links it to President John F. Kennedy’s visit to San José, Costa Rica, in March 1963 for a conference with the presidents of Central America. Here he signaled a more active policy on Central America and the support for the idea of a common market for the region.Footnote 57 The narrative, as told by INCAE itself and in different publications, explains that Kennedy’s mission to San José “initiated the project.”Footnote 58 The narrative also says that the declaration at the meeting suggested the establishment of INCAE, even though INCAE was not mentioned by name. According to the declaration, the United States and the six Central American countries should:

strengthen as greatly as possible the regional Central American institutions so that they can play a fundamental role in the training of necessary personnel to bring to fruition the plans for integrating the Isthmus.Footnote 59

Finally, the narrative says that upon his return to Washington, Kennedy “drew on his Harvard ties to initiate the project.”Footnote 60 In April 1963, he contacted Dean Baker at HBS and asked him to establish a management program in Central America based on the Harvard model. At HBS, George Cabot Lodge was asked to explore the feasibility of a Central American management school.Footnote 61 Lodge told another story later, however, which does not reduce the importance of the Cold War perspective, but which illustrates the complexity of the process.Footnote 62 Lodge had joined HBS as a lecturer in February 1963, one month before Kennedy’s visit to San José, after an unsuccessful run for the U.S. Senate. He was hired for one year by the dean to explore what HBS could do in Latin America. Having worked for Kennedy’s administration as assistant secretary for international affairs to the secretary of labor, he had many friends in Washington. Among them was the economist Walt Rostow, one of the main advocates of the new modernization theories, and at that time the head of the State Department’s policy planning staff. Three weeks after Kennedy’s speech, Lodge went to Washington to talk to Rostow about Kennedy’s speech in San José. Rostow mentioned that HBS should be involved and that funding for HBS could be arranged through USAID. Lodge found this extremely interesting, but as he later wrote, “I knew that Dean Baker and our faculty would be concerned about government funding. The School’s other international ventures had been underwritten by foundations.”Footnote 63 It was likely that HBS would say no if Lodge proposed this, and therefore, he explained, “I asked Walt whether the invitation to undertake the project could come from the President.” What a bright idea! Lodge continued: “Walt allowed as to how his secretary was sick that day so I could use her typewriter to type whatever letter I would like President Kennedy to send, and he would see to it that it was signed. This I did. It said, in part:

My recent talks with the Presidents of the Central American nations reemphasized our mutual concern for the rapid development of human resources in this critical area. The participation of the Business School in a program to strengthen management would constitute a vital step toward sound regional integration, a major objective of the Alliance for Progress.Footnote 64

The U.S. government wanted HBS to be involved in Central America, but it is likely that HBS would have refused if Lodge had proposed this, because HBS was overloaded with other international activities in countries such as the Philippines, Japan, Turkey, and Switzerland.Footnote 65 Lodge neutralized this concern by writing a letter to be signed by Kennedy, unbeknownst to his colleagues at HBS. As Lodge wrote later, this was a success: “My bosses—Dean Baker, Senior Associate Dean George Lombard, and Harry Hansen—were excited by the letter.”Footnote 66 Lodge and Rostow’s secret typewriter coup eased the idea’s path to the dean’s office but did not convince all faculty members. It took several months of “heated discussions” before the faculty voted to support the INCAE initiative.Footnote 67 At that time, HBS had already asked two professors, Henry Arthur and Thomas C. Raymond, in addition to Lodge, to visit Central America. In April 1963, they met three businesspeople from each of the six countries in Guatemala City and started the process of establishing INCAE in cooperation with USAID.Footnote 68

INCAE was defined as “private, non-profit, multinational institution of higher education, dedicated to the study of management in Latin America.”Footnote 69 It had a regional focus, and contact with national governments was restricted to negotiations regarding legal acceptance for operating in each country. Before the founding, the U.S. delegation explored the possibilities of cooperation with some universities, but the universities were not interested, mainly due to HBS’s case teaching method. HBS’s participant-centered case methodology ran against traditional lecturer-centered pedagogy.Footnote 70 Also, the Americans were skeptical. Jack G. Mocatelli, with work experience at both HBS and USAID, referred to mistrust between the universities and the business communities in the region.Footnote 71 According to the Regional Organization for Central America and Panama (ROCAP), the relevant USAID unit for the project, INCAE was “the only method of developing managerial competence through private sector support,” considering “the existing lack of identity of purpose between private enterprise and government and between private enterprise and autonomous universities.”Footnote 72

To develop INCAE as a regional business school, HBS (supported by USAID) began to recruit people from the region for teaching and administrative positions. In 1963, four men and one woman from Central America were selected to participate in the one-year ITP at HBS to develop local faculty, and more were to participate in the coming next years.Footnote 73 However, the most important links to the regional communities were through networks with local businesspeople. In 1963, George C. Lodge organized a visit with nine HBS doctoral and MBA students to all six countries to write teaching cases and interview more than four hundred managers in each country. Through this trip, HBS established contact with businesspeople that INCEA later drew upon.Footnote 74 Professor Clark Wilson, HBS, was appointed the academic advisor in June 1966, and from January 1967, the first rector of INCAE. In this position he was supported by a board of six businessmen from each of the countries in the region, with Francisco de Sola from El Salvador as the chairperson. De Sola, or Don Chico as he was called, was chosen before INCAE was founded, because several U.S. business leaders with experience in the region had named him as an influential business leader with strong networks. Advised by de Sola, HBS contacted business leaders in the other countries to join the board.Footnote 75 The business networks were also sources for information regarding INCAE’s efforts to develop regional teaching cases. According to a summary of the activities during the first twelve years, 85 percent of faculty research time was spent on case development.Footnote 76

The strong position of HBS and USAID in designing INCAE is undisputable. However, representatives from the regional business communities had a strong impact concerning INCAE’s focus on executive education. In this matter, HBS and USAID emphasized different objectives mentioned in original project contract: (1) “continuing education for managerial personnel already in business” and (2) “graduate level management training.”Footnote 77 INCAE prioritized the first objective. One reason for this was that businesspeople in the region supported the idea of management education if this was done through shorter programs.Footnote 78 They rejected the idea of starting with an MBA, because the education process was too long.Footnote 79 This attitude was in line with HBS’s positive view on executive education as a tool to develop “high-level managers for leadership roles in the management of change”Footnote 80 in a context “where the old social order is breaking down with new, still obscure, forms taking its place.”Footnote 81 The argument was that there was an urgent need to train top business managers according to what HBS perceived as modern business administration principles.

In contrast to this view, ROCAP argued in favor of a permanent graduate business school. ROCAP made it clear that a successful transformation to a graduate business school was a precondition for funding from USAID. If there were no transformation, “the US should seriously reconsider the utility of proceeding with this project.”Footnote 82 The argument was geopolitical in nature. There were too few trained business management personnel in Central America, beyond managers who had taken short courses. ROCAP perceived the lack of well-educated professional managers as a serious problem for the development of a Central American common market and highlighted the importance of a graduate school “as even greater opportunities for participation in a broader Latin American integration movement materialize.”Footnote 83

Due to HBS’s strong belief in executive education and the support from local businesspeople, executive education secured a strong position at INCAE from the very beginning. However, in 1967, the emphasis shifted from executive education to the preparation of a permanent institute that would provide a two-year master’s program called Programa de Maestria en Administración de Empresas.Footnote 84 The following year, Ernesto Cruz from Nicaragua, with a PhD in political economy and government from Harvard University (1968), took over the leadership as rector and managed the school until 1980. By the time of Cruz’s appointment, twenty-three faculty members, twenty-two researchers, and eight administrative personnel from HBS had visited INCAE for periods of one to five months, and seventeen had been sent from INCAE to HBS for training.Footnote 85 In 1972, the advisory board of HBS professors had its last meeting, and the formal agreement between INCAE and HBS on developing INCAE ended.Footnote 86

ESAN

One year before INCAE launched its first executive program for Central America, twenty-seven managers met on August 15, 1963, for the first full-time four-week executive development program organized by the new institution, ESAN, in Lima. As INCAE was an HBS project, ESAN was a Stanford project.Footnote 87 “We ran ESAN,” Stanford professor Charles “Chuck” Horngren said.Footnote 88 As HBS operated and performed most of the teaching at INCAE in the first years, Stanford had the same function at ESAN. ESAN became a flagship in USAID’s narrative about its work in Latin America. It was repeatedly highlighted as a major success and was described as the first business school in Latin America that solely offered graduate programs.Footnote 89 This perception must be nuanced, because it was eight months after the first executive program before the first class of the graduate program met.Footnote 90 ESAN continued to offer executive education in Lima and other cities in the country parallel to the master’s program, Magister en Administración.

The initiative to establish ESAN came from USAID. In 1961, Robert Culbertson was appointed as the new director of USAID for Peru under the Alliance for Progress program. Before this appointment, he had been attached to the Ford Foundation, where he met the dean of the Stanford Graduate School of Business, Ernest Arbuckle, and learned about Stanford University’s activities in Latin America and the foundation’s grants to pursue international programs at the university. On arriving in Lima in January 1962, he met several businesspersons, including Norman King, director of the U.S.-owned mining company Cerro de Pasco Corporation, and Carlos Mariotti, director of Empresas Electricas. They both argued for the initiative to establish a new business school in Peru. These ideas prompted Culbertson to contact Arbuckle to find out whether Stanford would cooperate in Peru.Footnote 91 As in many other Latin American countries in the 1950s, the U.S. government had supported various projects in Peru. Some were International Cooperation Agency projects to assist with vocational education and management training.Footnote 92 The Alliance for Progress program now wanted to upscale these activities.Footnote 93 One result of the first contact with Stanford was that in 1962 USAID sent four faculty members from Stanford to Peru to write a report. This was the beginning of a process that led to the creation of ESAN, a private business school created through cooperation of Stanford, USAID, and the government of Peru.

The creation of ESAN also illustrates how U.S. MNEs in Latin America participated in forming the institutional setting for the internationalization of executive education. The first director of the Stanford committee to make a visit to Peru was Gail M. Oxley, the school’s director for overseas development from 1961 to 1965 and Stanford’s first professor in international business.Footnote 94 He knew Peru very well, as he had been vice president of W.R. Grace & Company’s South American operations. This was an industrial conglomerate founded in Peru 1854. In 1865, its headquarters moved to New York City but retained a strong focus on Latin America. Oxley, who entered Grace after graduation from Columbia Law School in 1940, played a leading role in organizing and managing the company’s activities in Bolivia and Peru. Before he moved to Stanford in 1961, he was responsible for twelve businesses, with twelve thousand employees, including sugar production, textile manufacturing, mining, transportation, and shipping. He was also the corporate secretary of Pan American Grace Airways.Footnote 95

The report from the Peru study group managed by Oxley and financed by USAID strongly recommended that Stanford should participate in the creation of a new business school in cooperation with USAID and the government of Peru. USAID first considered several alternatives to Stanford to operate the new business school, including Oklahoma State University.Footnote 96 After having decided to accept Stanford, USAID pushed the school hard to accept the invitation. As at HBS in the INCAE case, there was some resistance among faculty members, primarily because of fear for the security of those who would travel and the consequences for activities at the Stanford campus in Palo Alto, as the five-year contract would require twenty person-years at ESAN. Some also argued that the universities in Peru would not allow the development of a new independent business school. After five years, Stanford could demonstrate that a quarter of its faculty had traveled to Peru and taught at ESAN.Footnote 97

There were two striking differences between INCAE and ESAN. The first difference was in relation to business and national governments. Both INCAE and ESAN had ambitions to build strong networks with the local business communities. At ESAN, this aim was balanced with the need to develop close relations with the university system, which was neglected at INCAE. According to George R. Lindahl Jr., who had worked for ROCAP in Peru, it was a question of two different philosophies. In Peru, USAID/ROCAP decided to develop close relations with the university system and then invite the business community to cooperate “after we had something more than a pig in the poke to sell.” INCAE’s philosophy was to develop close relations with the local business community first and “not to proceed until private sector underwriting was first assured.”Footnote 98 The ESAN project took the initiative to develop relationships with local businesses, however. The Oxley committee had several interviews with local businesspersons, who strongly recommended that the business school should be independent of the public universities. Developing close relationships with business was important, but it was subordinate to the development of good relationships with the government and the university system. At INCAE, the development of business relations was superior to other aims. The result of these discussions was that ESAN formally stayed outside the university system and resisted political pressure to be formally connected to San Marcos University. On July 25, 1963, ESAN received a degree law confirming ESAN as an independent graduate school.Footnote 99 While all INCAE’s board members were businesspeople, representatives from universities and the national government joined the advisory board of ESAN together with representatives from business associations. This board, Patronato, had the authority to appoint a dean and approve the budget.Footnote 100

The other difference was ESAN’s profile as a graduate school, as opposed to the focus on executive education at INCAE. ESAN was already planned as a graduate school when USAID approached Stanford, whereas HBS focused on executive programs in the planning of INCAE from the very beginning, before USAID convinced the school to include a master’s program. ESAN’s first master’s program started in April 1964. Still, ESAN made an important contribution to the introduction of executive education in Peru. The first short management development program for middle managers was offered together with the Instituto Peruano de Administración de Empresas (IPAE) eight months before the first master’s class met. In the planning process of a new master’s program, the Peruvian government expressed that they accepted that ESAN added some activities that would attract local businesses at an early stage.Footnote 101 Together with the IPAE, Alan Coleman, Stanford, and Richard Keynor, USAID, planned a four-week middle management training program in March 1963 “as the first concrete activity of the new Graduate School of Business.”Footnote 102 All actors accepted that the new school could add a top management program later, based on the experiences of the middle management program.Footnote 103

After five years, ESAN had graduated 335 Peruvians with one-year MBA degrees. Some parts of the business community had begun to accept the new school, while others were skeptical and did not see why appointments to management positions should be based on formal management education. Companies with international activities were the most positive. Of the graduates from the first five years, 16 were employed by W.R. Grace & Company, the company where Oxley worked before moving to Stanford. In addition, the school had trained more than one thousand participants in short programs lasting from three weeks to three months.Footnote 104 Some of these courses had been offered outside the capital of Peru, in Paracas, Arequipa, and Chiclayo.Footnote 105 These results meant that USAID regarded ESAN as a success. When USAID summarized these achievements and evaluated them based on the importance of strong relations between the USA and Latin America in the global order, the conclusion was that ESAN was “one of the most successful AID sponsored projects [in Latin America].”Footnote 106

At this time, what was perceived as the Peruvianization of ESAN had begun.Footnote 107 After five years, the number of Stanford faculty teaching at ESAN was reduced from nine positions to five. There were six faculty members from Peru; three of them had been trained at Stanford. The financial support from USAID was reduced. It still covered 37 percent of the total budget, while the Peruvian government covered 25 percent, and tuition fees, 38 percent. The new dean, Gerald O. Wentworth, from Stanford like his predecessors Alan Coleman and Sterling Session, announced that he would be the last dean from Stanford. The board appointed a Peruvian professor, Orlando Olcese, the former rector of Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina (UNALM), the main agricultural university in Peru, and a respected businessman, to replace Wentworth as dean.Footnote 108 The takeover had to be postponed, however, when Olcese was appointed minister of agriculture, and he never did take up the dean position. In 1970, Tulio de Andrea, the former economics and finance minister (1967–68) and the president of the Industrial Bank of Peru, was appointed the first Peruvian dean of ESAN. He was also a successful businessman and Peru’s representative in the World Bank. Two years later, all U.S. full professors had left ESAN.Footnote 109

USAID and Stanford had been the two major U.S. actors in this first period of ESAN history, when executive education was established as part of ESAN’s activities. The Ford Foundation played a minor role, little more than connecting people in the initial phase, as it often did, due to the close relations between the foundation and representatives from the most prestigious universities, as well as governmental organizations.Footnote 110 After ESAN’s founding, the Ford Foundation followed the development of the new graduate school closely, for example by awarding a grant to the school in 1973 to consider how Peruvian firms could increase worker participation in management and ownership.Footnote 111 When the Ford Foundation summarized the achievements of ESAN in 1980, the report stated that ESAN had been established by “a group of Stanford professors, many of whom were being eased out of the university as Stanford Business School began its (successful) challenge to Harvard’s pre-eminence of the field.”Footnote 112

Colombia

In both Central America and Peru, there were local actors who supported the development of new business schools and the growth of executive education. It was, however, two U.S. business schools in alliance with USAID and to some extent supported by the Ford Foundation, that designed and pushed the idea forward. In Colombia, the balance between foreign and domestic actors was different. There were, indeed, important links with the United States, but the first executive programs were initiated by local actors. The U.S. context primarily served as a resource upon which the educational entrepreneurs, defined as persons who create new or innovate existing educational institutions, could draw.Footnote 113 Unlike in Peru and Central America, where U.S. business school faculty members primarily came to develop one specific business school, the American visitors came to Colombia primarily to teach in the three cities where there were initiatives to establish business and executive education: Cali, Medellín, and Bogotá. According to an overview from 1966, forty-six faculty members from twenty-one U.S. universities had taught business and management in Colombia between 1945 and 1966. Of these, Syracuse, Harvard, and Stanford sent seven each.Footnote 114

As large as this number of American visiting faculty may appear, no traces of them are to be found in further significant developments, except perhaps those coming from the three universities named. In Colombia, the channel with the strongest impact in transferring knowledge from the United States, was a pair of prominent members of the Colombian elite, Hernán Echavarría and Manuel Carvajal, the heads of two entrepreneurial families, together with a handful of young Colombians who traveled to the United States for graduate studies.Footnote 115 They all came back to Colombia in the 1960s with new ideas about management education, specifically executive education. It is important to note that, in contrast to the U.S. experience, entrepreneurial families and business groups have been key actors in the different phases of globalization since the late nineteenth century in emerging markets like Latin America.Footnote 116 In fact, owners were also managers with experience, and in-company training was a useful way to enter business management. The broader context was industrialization through the substitution of imports within a model of protectionist development, with the state playing a leading role.

Educational entrepreneurs were not circumscribed to the capital city (Bogotá), but there was an influx in the second and third largest Colombian cities (Medellín and Cali) of this “country of cities.” Similarities in their origin aside, their history varied from one institution to another. In Bogotá the first executive education courses were located in a private, elite, nondenominational university (Universidad de los Andes [Uniandes]), whereas they were in public/state universities in both Medellín (Universidad Nacional Medellin campus [UnalMedellín]), the pioneering center of industrialization in the early twentieth century, and Cali (Universidad del Valle [Univalle]), the core of the sugar industry since 1900 and seat of the North American MNEs that arrived in the late 1950s. Interestingly, at the time all offered five- or six-year professional degrees (in engineering, law, medicine, economics) but did not have graduate schools offering master’s or doctoral degrees. Courses in business and management were mostly offered by engineering and economics schools (e.g. in Uniandes). Management departments and schools did not come into existence until the 1960s in Univalle and UnalMedellín; Uniandes’s School of Management branched out as a different school from economics in 1972 and was based upon the faculty from the industrial engineering department.Footnote 117

The first case of executive education to be analyzed is the top management (Alta Gerencia, AG hereafter) program at Uniandes. Its first director, Arturo Infante, headed it until 1978, when AG moved from the School of Engineering to the School of Management. Infante had a BS (1961) in industrial engineering from a Colombian public regional university (Universidad Industrial de Santander [UIS]) and an MSc (1964) from Penn State. A year after completing his PhD in operations research at Stanford in 1967, he joined Uniandes’s Industrial Engineering Department and promptly became department head. This was the first position in his distinguished career as the university’s director of financial development (1968–1970), dean of the School of Management (1981–1983), and later Uniandes’s vice president and its president for a decade (1985–1995).Footnote 118 Like the other educational entrepreneurs, Infante was well connected to the local business elite.

The need to introduce management ideas, techniques, and professionals was gaining acceptance as playing a definite role in the modernization process within the business elite. Contrary to the idea of the Latin American elite embodying “anti-entrepreneurial values,” as trumpeted in some American academic quarters,Footnote 119 entrepreneurial leaders like Echavarría and Carvajal acted as role models who were strongly committed to promoting educational initiatives aimed at strengthening modern business management. These were not isolated projects but should be understood in the broader context of the quest for modernizing the Latin American university system. This was one of the programs of the Alliance for Progress, in this case following the recommendations of the Atcon report commissioned by the U.S. Department of State in 1963.Footnote 120 Uniandes’s quest for innovation, which had followed the U.S. rather than the European model since its inception, made it a sort of “donor’s pet” for the Ford Foundation in the 1960s and 1970s. It received grants to establish a School of Arts and Sciences, to consolidate the School of Engineering, and to create a Law School.Footnote 121

AG was based in a university that aimed to educate the country’s leadership. It enjoyed support from the university president’s office, where Infante was a staff member during the formative years of the program (1968–1970). Echavarría was one of the founders of Uniandes in 1948, former dean of the School of Economics, and an influential member of its board of trustees.Footnote 122 He had also strongly supported the foundation of the Instituto Colombiano de Administración (INCOLDA) in 1959, a business association initiative with sites in major Colombian cities aimed at providing practical management training in the modality of executive education. INCOLDA was also supported by the U.S. government, with the aim of developing “an ambitious program for broad management training in the major cities of Colombia.”Footnote 123 However, Colombian university programs in business, including executive education, did not attract substantial financial support from USAID.

Executive education at Uniandes was based at the Department of Industrial Engineering, and the School of Management was established as late as 1972, four years after the AG program was organized. When it came to the quantitative content disciplines, however, such as operational research, they had almost no impact. Infante himself said that he had worked to include psychology, organizational behavior, and organizational development in the program. AG was cross-disciplinary in its character, targeted a top executive audience, and reflected the enduring interest of the Industrial Engineering Department since its inception in the human and social side of business.Footnote 124 Among those who lectured in the first year were industrial engineers with MBA degrees, economists, a political scientist, lawyers, a psychiatrist, and a literary writer.Footnote 125 Particular care was taken with the selection of AG’s faculty from the start. A doctoral degree was less important than seniority and teaching skills.Footnote 126 Based on a cross-disciplinary approach, the program was conceived as innovative, aimed at leaders in business and society. It emphasized the discussion of the Colombian economic and political context. Its methodology purposefully facilitated networking. Participants were predominantly males, and parallel sessions on family development, women, and political issues were offered to the participants’ female partners. AG spared no expense in logistics.Footnote 127

A distinctive feature of this non-degree program was its length—12 months—which became an imprint of AG for its half century of existence. The methodology of the sessions rested upon participant learning that combined discussions, working in groups, case studies, and group dynamics that differed from the conventional passive, teacher-centered methodology.Footnote 128 Participants were carefully selected to represent not only entrepreneurs and top business executives, but also a sample of top public officials, including army and navy leaders, university officials, senior Uniandes faculty, and one or two politicians. There were also rising entrepreneurs, for whom AG served as a social mobility channel for integration into Bogotá’s closed elite.

The need for short-term executive programs increased after the inception of AG, and some were organized in both the School of EconomicsFootnote 129 and then in the newly created School of Management, which in 1973 organized a one-year, custom-tailored program in management for the executives of a local bank.Footnote 130 The increasing demand for executive education also signaled its potential as a source for funding the new school’s operations. As the experience of the School of Management for the next three decades would demonstrate, revenues from executive education became a pillar in its expansion and consolidation. In the words of one of its former deans, executive education became “the cash cow” for school funding.Footnote 131

In 1975, a unit for management development programs called Desarollo Gerencial Avanzado (DGA), was established separate from both the AG and MBA programs. Its first director, Héctor Prada, had been the founder and head of the Industrial Engineering Department (1965–1968) and finance and administrative director of Uniandes (1968–1971) and taught at AG.Footnote 132 From the beginning, DGA’s portfolio included short, open, specialized courses in several fields of management, as well as custom-tailored, in-company courses for the incumbents of middle management positions in large companies. They generally took place well away from Bogotá, such as in a sugar mill in the west of the country near Cali or in the country’s largest, state-owned steel company plant. One of the DGA’s director’s more difficult tasks was to get faculty interested in participating in these programs, especially those outside Bogotá. Faculty members did not have to teach in them as part of their regular duties; those who participated did it on a voluntary basis with the incentive of receiving additional remuneration.

The second case of executive education development took place in the mid-1960s at Univalle in Cali, the public regional university founded in 1945. A pioneering role was played by Manuel Carvajal, a prominent business and civic leader who had been minister of mines and oil, later minister of communications, and the first CEO of the state-owned oil company, and whom Infante knew well. As head of a wealthy entrepreneurial family, Carvajal was concerned about the lack of managerial training among the young descendants of his elite peers. Generally, they had been educated in the United States in engineering and technical fields and did not seem to have the skills required to manage their businesses. Moreover, they did not seem prepared to undertake leadership in local and regional matters in a decade when social conflict and developmental challenges were mounting in Cali and the Valley of Cauca region.Footnote 133

The local business elite supported several new initiatives in management education and training from the early 1960s. Carvajal was one of the business leaders who joined Echavarría in founding INCOLDA in 1959. Between 1961 and 1963, INCOLDA, in association with Univalle’s School of Electromechanical Engineering, offered a non-degree program in industrial administration. In 1964, an evening undergraduate program in administration was initially located at the Electromechanical Engineering School before it became part of the School of Economic Sciences in 1965. Another initiative was the Tuesdays’ Group (“Grupo de los Martes”), a group of nearly twenty members from Cali’s elite, established in 1963 with strong support from Carvajal to diagnose the situation in the region and the challenges it posed.Footnote 134 One of its members who would play a key role in management education at Univalle was Reinaldo Scarpetta, who held only a BA in industrial management from Georgia Tech but was an executive in his late twenties at a steel manufacturing company and INCOLDA director in Cali. A recent historical study on the role of the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations in Univalle depicts Scarpetta as having a “flair for self-promotion, and absolutely no interest in economics”Footnote 135 and being a man who was a “globe-trotting evangelist for business education and for businessmen themselves.”Footnote 136 After eighteen months of unsuccessful recruitment efforts by Univalle and the Rockefeller Foundation to find a dean for the School of Economic Sciences, Scarpetta was appointed in 1964. To showcase the interest in strengthening ties between the Tuesdays’ Group and the major local university, Scarpetta was given license by the company he led to work at Univalle and lead the remaking of the economics program, a major concern for the Rockefeller Foundation.

While Scarpetta was dean, Laurence de Ricke, a seasoned expert in U.S. business associations and think tanks and experienced in promoting “free enterprise,” arrived as the first U.S. visiting professor sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation. He became Scarpetta’s “chief sparring partner and collaborator” in the launch of an academic reform that included a graduate industrial management program, a curricular reform of the undergraduate economics program, and a research center.Footnote 137 Interestingly, according to a Ford Foundation report, de Ricke’s “vision of management as an applied social science resonated with the Ford Foundation.”Footnote 138 Roderick O’Connor, Scarpetta’s former teacher at Georgia Tech and his advisor when he became INCOLDA’s vice president in 1961, was also close to the incoming dean, and had a lasting influence as a consultant to Cali’s elite. O’Connor, a full professor of management at Georgia Tech, was commissioned to go to Univalle as visiting professor. There are disparate opinions about him. For some he was “a Renaissance man,”Footnote 139 also revered by members of Cali’s elite. An incisive comment by a Rockefeller Foundation official in the mid-1960s suggested that O’Connor “combines the American stereotype of the hardheaded businessman with the American stereotype of the evangelist.”Footnote 140 O’Connor obtained approval for a master’s in industrial administration, called the “Magister Especial” (ME), a program inspired by the Georgia Tech and MIT master’s in management programs.

Counting upon support from the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations, Dean Scarpetta moved promptly to recruit seven U.S. scholars and two Latin American (from Chile) scholars who were trained in the United States,Footnote 141 a heterogeneous group that reflected a variety of approaches in management as well as different U.S. business schools. They came from Stanford (Ezra Solomon, David E. Faville), HBS (Lodge), Georgia Tech (O’Connor), New York University (Peter Drucker), Northwestern (Hans Picker), Chicago (Sergio Muñoz), and MIT (Howard Johnson).Footnote 142 Their academic persuasions ranged from finance and quantitative management science approaches to social sciences, qualitative perspectives that nurtured general management, organizational studies, strategy, and marketing. Domestic faculty were rare and had just started going to the United States for graduate education under the aegis and support of the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations.

The ME lasted for eighteen months, and its distinctive feature was the composition of its thirty-six-member, inaugural class of 1965: they were all CEOs. Later, they were known for leading the “milagro del Valle” (the Cauca Valley miracle) during the second half of the 1960s.Footnote 143 After this one-of-a-kind inaugural class, the program evolved into the “Magister Regular” (regular master’s), more in tune with the rest of the university academic standards, although still looking for top-level participants.

Together with O’Connor, who forged a close friendship with Carvajal (“Don Manuel,” as he was respectfully referred to), prominent management guru Peter Drucker was a noted lecturer who ran a three-day seminar for the ME in 1964.Footnote 144 The ME program continued operating and targeting that specific market niche until the early 1970s, now within the Engineering School, a new academic space for the then-itinerant Department of Management. In parallel to the top ME echelons, INCOLDA ran evening programs aimed at middle managers and certificate courses. Overall, “nearly one thousand Colombian businessmen, public officials and trade union leaders had enrolled in the courses” during the 1964–1969 period.Footnote 145

In 1971, Univalle experienced violent student riots, as did public and private universities in Colombia, where the student movement was a key political force. Notably, the Alliance for Progress programs in Colombia, together with the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations, were targets of the protest, which contested the ongoing university reform in Latin America along the lines of the already mentioned Atcon report.Footnote 146 As a result of the riots in February 1971, where a student died and the army burst onto Univalle’s campus, which had been taken over by the students, the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations were expelled from Univalle in practice.Footnote 147 These events were a milestone for Univalle, whose president, Alfonso Ocampo, resigned as a result.Footnote 148 Ocampo, a medical doctor and an educational entrepreneur and member of Cali’s elite, received his graduate education at Harvard, Cornell, and Columbia and was very successful in establishing links with American foundations, especially the Rockefeller Foundation.Footnote 149 A consequence of the conflict was the definite split between Cali’s business elite and Univalle, which lasted almost half a century.Footnote 150 Instituto Colombiano de Estudios Superiores de Incolda (ICESI), a private university sponsored largely by the same elite that promoted the ME program, was founded in 1973. Ocampo was a champion of the initiative and was later its president for more than ten years (1984–1995).Footnote 151

Conclusions

The idea of training managers through executive education programs spread to Latin America in the first decades after World War II and peaked in the 1960s. This process was part of a general process of Americanization, which in the case of Latin America included sponsoring a series of “modernization” reforms aimed at forming the developmental state. The processes included the reform of the university system and, as part of this, spreading management education. The idea of executive education was also spread through programs on industrialization-led economic development. The geopolitical overtones of the process, amid the Cold War and the 1959 Cuban Revolution, need to be considered. They were related to the U.S. ideal of “exporting progress” that backed the Marshall Plan for a recovering Europe after the war and, in tune with the broader idea of the role of educating managerial hierarchies, was a key component of managerial capitalism.

Our study of four cases about developing executive education in Latin American contexts shows variations regarding what Americanization means. The most striking difference is the strong position of U.S. actors in the Central American and Peruvian cases in contrast to the active role of local actors in the Colombian cases (see Table 3). We are aware of the limitations related to studying four cases within a large continent filled with political, cultural, and economic contrasts in the period we have studied; however, we can also see that our approach has advantages compared with studying only one country, which so far has dominated historical research on management education in Latin America. It enables us to address new topics for more detailed research, such as the relationship between the new educational institutions and political and ideological conflicts. Most of all, the study enables us to highlight three findings.

Table 3. The founding and the context of the first executive education programs at INCAE, ESAN, Uniades, and Univalle

First, the cases show differences in efforts and achievements among the U.S. actors in this process. American business schools played an important role in all cases; however, while HBS and Stanford were actively imposing their models in the Central American and Peruvian contexts, U.S. business schools served more as a resource upon which local initiatives drew in Colombia. USAID also played an active role, especially in the first two cases. The efforts to establish INCAE were undoubtedly linked to the closeness in time and space of the Cuban Revolution. United States’ foundations were present in several countries in this process. The Peruvian case illustrates that the Ford Foundation had a function beyond funding by acting as a networking unit to connect USAID’s political initiative to Stanford. In Colombia, the Rockefeller Foundation was involved in Cali, which illustrates general observations that many of the foundation’s activities to support management education and development initiatives are difficult to trace, as they were minor parts of larger projects for industrial development. This invites more microstudies to unpack the multiple functions of the foundations’ international projects. The Peruvian case also shows that American MNEs played a key role in establishing a new business school, ESAN, and introducing executive education as a key activity. The role of the MNEs is also a topic that needs further research. One unstudied question is whether their ideas on topics such as the defense of “free enterprise,” foreign investment and management as a universal technique, had any impact on the programs. The references to INCAE as a “multinational institution of higher education” indicate that the strong postwar growth of MNEs had an impact on the conceptualization of new business schools such as INCAE.Footnote 152

Second, the role of local actors in relation to the United States varied in the different countries. While representatives of the business elites in Colombia were active in connecting to American experiences in management education and developing the programs, the process was the opposite in Central America. There, representatives from HBS and USAID, which operated the schools, searched for local business support and established boards of trustees with local representatives. The resistance of the local business community to the idea of lengthy education had an impact on INCAES’s strong focus on executive education and late introduction of graduate degree programs. While HBS in Central America initiated and conducted projects to write local teaching cases, local business actors at Uniandes in Colombia were decisive in pushing the idea of developing local research capability. This led, among other things, to developing teaching materials for executive education and other programs grounded in the domestic reality.Footnote 153

Finally, the relationships between local actors also varied. One dimension that needs further research is the relationship between government and the business community regarding the perception of relevant education for management in general, and for senior managers particularly. In Central America, the United States’ need to establish a closely linked institution based on the Pan-American idea in the context of the Cold War and the fear of the nearby Cuban Revolution spreading was so strong that the governments in the six countries were held at arm’s length. This fitted HBS’s skepticism about cooperating with state universities with low academic reputations. In Peru, however, the government was a more active partner in the formation of ESAN, but the degree of integration between ESAN and the national university system was weak. The executive programs also supported the development of the universities in Colombia, but primarily private universities such as Uniandes, a university established for educating progressive and entrepreneurial actors within the elite. The vicissitudes in the case of a state university (Univalle) are better understood if executive education is seen in the context of local elites striving for a leading role in state and regional development.

This article offers a new empirical field for studying the development of executive education in an emerging market region. First, it contributes to the history of management education in looking beyond the North Atlantic. Second, encompassing underdeveloped, emerging markets enriches the understanding of the Americanization of management education and leaves no doubt about its political economy overtones. Third, studying the development of executive education in emerging markets aligns with the tenets of alternative business history. Our findings may inspire more research not only into executive education in Latin America, but also into U.S. influence on management education in general, and executive education particularly, on other continents. More generally, such studies have the potential to become part of the agenda of the growing “alternative” business history claiming that the history of business in emerging markets is not a carbon copy of the business history of developed countries.Footnote 154 In this context, our study illustrates both common patterns and inter- and intra-country differences regarding the dissemination and singularities of the professionalization of management in Latin America. This took place on a scale and within a scope substantially different from those of the U.S. experience.