Introduction

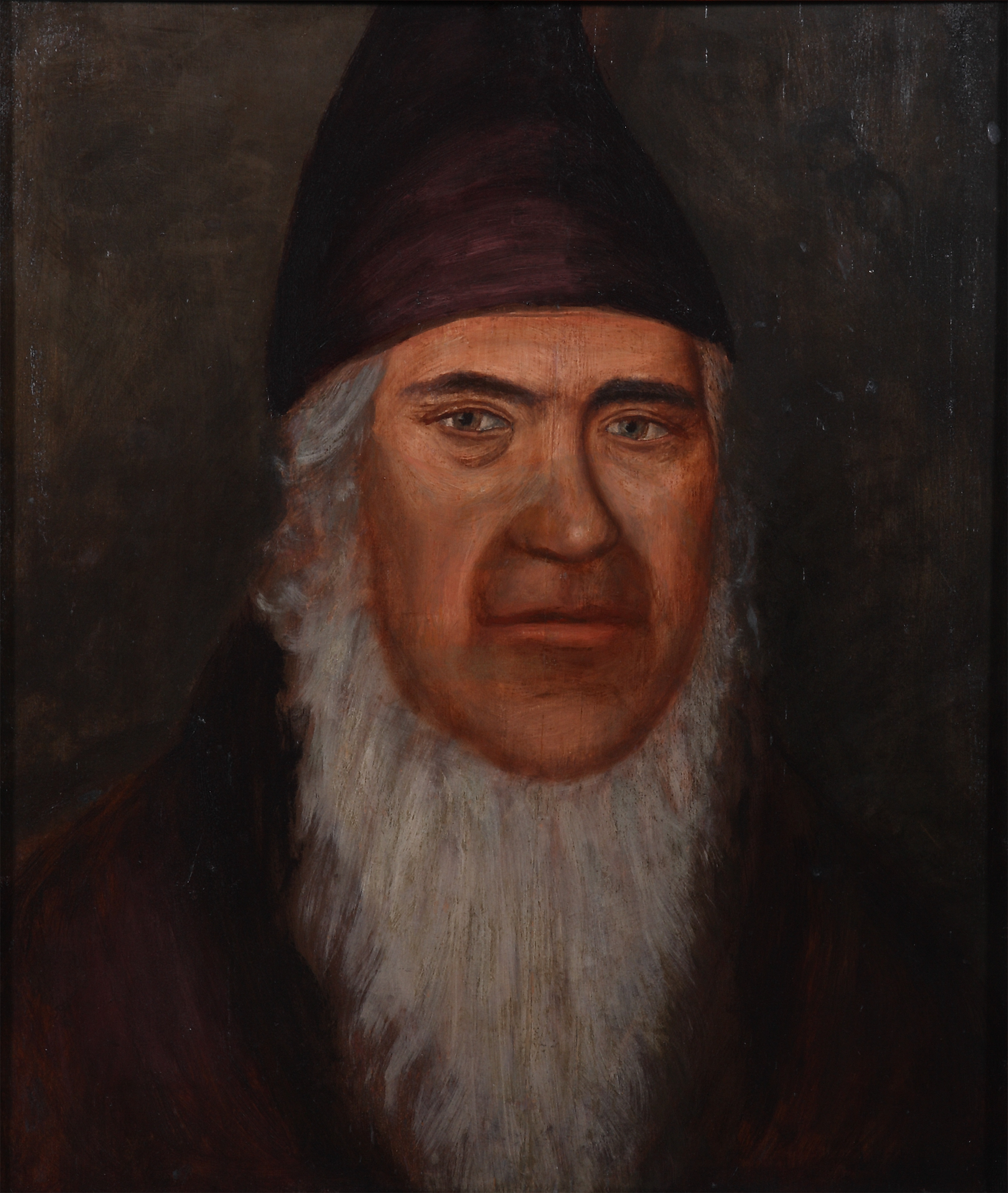

George Rapp (Figure 1) surveyed the fields surrounding Harmonie, Indiana, with pride. Well-tilled and fruitful, they were not only sustaining his society, but also producing a healthy export profit. As his gaze panned, he caught sight of Harmonie’s hotel/tavern, well-known for the simple, yet warm hospitality it extended to travelers and curious visitors. Within the town, streets were laid out in an organized, tree-lined fashion. Solid, practical, comfortable homes surrounded the town’s center: the church. Not far away, cotton, flour, and woolen mills reflected the industry for which Harmonie was famous.Footnote 1 By the 1820s, visitors and commentators from all over the Atlantic world discussed the amazing productivity of Rapp’s Harmony Society and its communal, capitalist organization.Footnote 2

Figure 1 George Rapp.

Founded in 1805 by immigrants from Württemberg to Butler County in western Pennsylvania (near Pittsburgh), Harmonie was a Lutheran Pietist community that developed successful agriculture and textile manufacturing, all while eschewing private property. Feeling crowded by increased settlement, in 1814 the Harmony Society moved to southwestern Indiana. Hoping to connect to domestic and international markets via the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, the Society found instead an underdeveloped economic system, further destabilized by the Panic of 1819. Additionally, Harmony found that its relative prosperity during the Panic generated intense resentment among its neighbors, leading the Society to purchase a cannon for the granary, which could function as a fort. Rioters, concerned with the economic and political clout of Harmony, threatened its economic agenda. Disgruntled members of the community were abandoning the Society, demanding recompense for their work. Harmony’s business avatar, Rapp & Associates, struggled to make its customers pay their debts. By 1824, it was all too much, and Harmony moved back to western Pennsylvania, less than twenty miles from its original location. Harmony’s move back eastward revealed the tensions within and without the Society as it attempted to reconcile religion, communalism, and capitalism during an era when the new United States was confronting an expanding, transforming economy.

Religious belief and practice lay at the heart of this tension. Harmony was two things at once: an intensely religious community and a business enterprise. Grossly understudied, work on Harmony has focused on its peculiar religious beliefs and eccentric leadership, failing to appreciate how the Society functioned as a wildly successful business: Rapp & Associates. Partly this is because the religious utopias of the early nineteenth-century United States are often presented as “alternative,” aberrant, or reactionary visions of capitalism.Footnote 3 Such presentism imposes teleological order and certainty on the United States’ so-called market revolution, producing a story of how “capitalism ‘took command’ in nineteenth century America.”Footnote 4 In this narrative, communal capitalism did not offer serious answers to the question of how to construct a moral economic community.

The example of the Harmonists, whose communal capitalist community lasted almost a century, provides a resounding rebuttal to this narrative. They were the most materially successful communal capitalists in the first half of the nineteenth century, providing the model for the proliferation of similar groups, both secular and religious, including the Hutterites, Owenites, Mormons, Shakers, and Zoarites. Despite its fame throughout the nineteenth-century Americas and Europe, Harmony continues to fly under the radar of early American scholarship and is completely absent from America’s cultural memory.Footnote 5 Chris Jennings’s Paradise Now: The Story of American Utopianism is an example of a recently published work aimed at a broad audience that should have included Harmony in its narrative. Despite picking “five representative movements,” Jennings did not select Harmony. With the exception of the Shakers, whom he erroneously claims were the inspiration for the other four communes he chronicles, all the sects he studied existed for the briefest of moments in the nineteenth century.Footnote 6 Similarly, a 2019 op-ed in The Wall Street Journal stated that of some 40–50 communal societies founded in the nineteenth century, “all collapsed quickly” after two-year median lifespans.Footnote 7

Historians have famously sought out links between the United States’ early national period religious movements and the proliferation of capitalist systems, endeavoring to construct a narrative that explains a period of intense revivalism, political democratization, economic expansion, and social transformation.Footnote 8 Despite debates over the usefulness of metanarratives and categories, a near hegemonic narrative presently suggests that a “market/communication/ transportation revolution” caused the churching of the United States through the revivals of the Second Great Awakening, elevating broadly middle class Protestant values and mores into cultural dominance. Some might object to this characterization as an oversimplification of how scholars understand nineteenth-century America. However, despite some helpful correctives, the assumption that material factors led to an explosion in religiosity persists. Not only does this materialist approach fail to take religious belief seriously, but it fails to adequately explain the emergence and fuller vision of Christian communal capitalism.

The Harmony Society corrects this narrative in three ways. First, the Harmony Society’s primary reason for existence was not economic, but religious. As this article will explore, its vision of economics was one of a “divine economy” that would serve humanity in Christ’s new millennial kingdom. Birthed by a Pietist frustration with the Lutheran church, the Harmonists imported their religious and economic ideas to Pennsylvania and Indiana, the latter newly “opened” to settlement, thanks to the violent dispossession of indigenous peoples. Second, business enterprises with religious identities such as Rapp & Associates were shaping the United States’ economy in profound ways. This article explores this through Harmony’s relationships with its neighbors, customers, and local, state, and federal governments. Third, Harmony illuminates Pietism’s contributions to American culture. As the “third stream” of American theology, along with Calvinism and Arminianism, Pietism is comparatively understudied even though its focus on spiritual purity continues to inform the attitudes of conservative Protestants toward American culture in the twenty-first century. Ultimately, the example of Harmony helps us understand how religion shaped the US economy during the early national period.

This article begins with background on the migration of over eight hundred Harmonists from Württemberg to “Harmonie” in western Pennsylvania from 1803 to 1805, providing an overview of their religious views and how these shaped their economic ideas and activity. Next, the focus shifts to explaining how communal capitalism played out internally at Harmony’s first two sites in Pennsylvania and Indiana. Harmonists struggled and slowly grew in size and business at the Pennsylvania site from 1804 to 1815, before moving to southwest Indiana in stages, from 1814 to 1815. After ten years of confronting numerous obstacles in Indiana they sold the second Harmonie (in 1824) and moved back to western Pennsylvania during 1824–1825, where they established their third site, Economie. The manner of governance, labor organization, family structures, and property sharing are all integral to this part of the Harmony story. Equally fascinating is how Harmony dealt with its neighbors and customers, in other words, the marketplace. A focus on these external relationships forms the article’s third segment. In fact, during its time in Indiana, Harmony was involved in local, state, and federal politics to a degree that alarmed its neighbors. If this seemingly contradictory attitude toward the broader state surprises some readers, that only serves to underscore how scholars have misunderstood and overlooked the complex nature of Christian communal capitalism.

Religious Views: Pietism, Eschatology, and Self-Will

Pietism is central to understanding the religion of the Harmony Society.Footnote 9 Lutheran Pietism emerged from seventeenth-century religious revivals led by Philipp Jakob Spener, who himself culminated a hundred-year-old movement initiated by John Arndt (1555–1621).Footnote 10 Spener’s movement called for a grassroots effort to reform the Lutheran Church and transform individuals’ hearts through the process of sanctification (becoming more like Christ) and was particularly influential in shaping the Pietism of Württemberg, George Rapp’s hometown.Footnote 11 Eventually the movement spread to England, where it influenced the Wesleys, and to North America, where it was a part of the Great Awakening of the 1730–40s.Footnote 12

Pietism is not only a set of theological doctrines, but also is characterized by a specific posture toward one’s spiritual and secular communities. Foremost, the Pietist strives for holiness or sanctification in all aspects of life, to include her or his vocation and economic relationships. By living a thoroughly perfected life, Pietists strive to demonstrate to their larger church denomination, state government, and culture what an orthodox, sincere, Christian life looks like. Pietists stress a “personally meaningful relationship of the individual to God,” emphasizing perfectionism or sanctification, intense Biblicism, and an oppositional posture toward the larger society, government, and the institutional church.Footnote 13 The more extreme outcome for Pietists such as George Rapp was separation from the Lutheran Church. As the Harmonists came into increasing conflict with the established Lutheran Church over doctrine, education, military service, sacraments, and spiritual authority, spiritual separation and physical immigration to America seemed like the best solution for all concerned.Footnote 14 Pietism influenced nearly everyone in colonial America, as both Puritan Calvinists and Wesleyan Arminians reflected the influence of Pietism, as well as colonial era religious minorities such as the Dutch Reformed, Mennonites, Moravians, various German sects, and the Brethren.Footnote 15

Inspired by the communal ethos of early Christ followers, Rapp interpreted two New Testament passages to mean that the first-century church forsook private property. These passages were Acts 2:44–45—“And all that believed were together, and had all things common; And sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need”—and Acts 4:32–35:

And the multitude of them that believed were of one heart and of one soul: neither said any of them that ought of the things which he possessed was his own; but they had all things common. And with great power gave the apostles witness of the resurrection of the Lord Jesus: and great grace was upon them all. Neither was there any among them that lacked: for as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them, and brought the prices of the things that were sold, and laid them down at the apostles’ feet: and distribution was made unto every man according as he had need.Footnote 16

This description of the early community of Christ followers formed the theological foundation of most Christian communal capitalist societies, including notably the Mormons, in which all property was seen as the Lord’s and was to be for the “benefit of all the people.”Footnote 17 A more complete summary of beliefs reveals a key component of radical Pietists separatists such as the Harmonists: a belief that the world was headed for imminent catastrophe, and only the true church would survive the looming destruction. Economic upheaval, the disintegration of the village social structure in Germany, and the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars only seemed to reinforce the imperative for true believers to separate from the institutions of an unraveling world.Footnote 18

Underpinning this sense of impending doom was the certainty with which Rapp told his followers that they were fulfilling biblical prophecy, a conclusion he derived from Revelation 12:1–6. This passage paints a scene in which a pregnant woman (“clothed with the sun”) flees a vicious dragon by escaping into the wilderness, where God will have prepared a safe haven for the “Sunwoman” and her child. Harmonists, hardly unique among Pietists in identifying their community with this woman of Revelation, were convinced this apocalyptic imagery prophesied how God would preserve them in the United States as a remnant to enjoy the coming millennial kingdom of Christ.Footnote 19 This picture of deliverance was powerful for pious believers, perhaps none more so than for the many pregnant Harmonists who made the arduous voyage across the Atlantic, including at least four who gave birth en route in 1805.Footnote 20

Upon arriving in North America, one of the most urgent issues was financial: how to pay for the land Rapp purchased on behalf of the Society. Rapp himself did not possess assets to pay the one-third down payment ($3,405.91), and in a prelude to how the Society would handle its members’ wealth, Rapp billed each of his followers according to his means. Some paid for twenty acres, some fifty, others over one hundred, while the most destitute paid nothing at all.Footnote 21 Whereas other Protestants had little trouble reconciling their faith and the acquisitive nature and excesses of the emerging market economy, Rapp found them in conflict with the teachings of Christ. This view of personal property rested on two foundations: first, on how the aforementioned first-century church handled personal property, and second, on the group’s theology of self-will.

Rapp’s theology of self-will was straightforward: the annihilation of one’s self-will was essential to become like Christ. Rapp absorbed this principle through the teachings of German eighteenth-century revivalist Gerhard Tersteegen, who argued that egoism undermined the process of sanctification and inhibited one’s relationship with God. Consequently, the answer for Tersteegen was radical action: One must deny all that was most important to the individual—“honor and reputation, money, property, house and home, friends and relatives”—in order to find true communion with God.Footnote 22

Even as Rapp was establishing communalism as a founding principle of the Society, he was also shaping Harmony so that it resembled a corporation, despite its failure to achieve formal incorporation from Pennsylvania. From the beginning, he conducted business transactions under the auspices of “Rapp & Associates” vice “Harmony Society.”Footnote 23 Rapp’s eschatology (view of the end times) is key to understanding how and why he fused a corporate structure onto a communal society. Harmonists believed the new millennium was at hand, which would usher in a new age when “God’s economy” would reign supreme. Theirs was both an attempt to create a “divine economy” and cultivate the perfectionism they believed would hasten the return of Christ.Footnote 24 Outsiders consistently struggled to comprehend this union of religion and business, incredulous that they could coexist in “harmony.” Instead, critics countered with the accusation that Harmony was far from a holy utopia, but in fact was dominated by “avarice, envy, hatred, disunity and even the most disgraceful vice of grasping for yourself the property of others.…”Footnote 25

Understanding the basics of Pietism—how it often impelled Protestants to hold themselves at a distance from the surrounding culture in an attempt to promote holiness and godliness—is essential to understanding the Harmonists’ internal and external tensions with the expanding market economy. Their expression of Pietism meant the Harmonists did their best to keep some aspects of the market (“corruptions” of private property and culture) at arm’s length, even moving farther into isolation in the West to preserve the purity of the community. This was a direct result of their understanding of what God primarily wanted from people: holiness or piety in all aspects of one’s life, including one’s vocational and economic relationships.Footnote 26

Internal Relationships: Governance, Family, Labor, Property

George Rapp and three other associates disembarked the Canton on October 7, 1803, in Philadelphia. Their purpose—find a spot in America suitable for the emigration of Rapp’s followers, some 150 families.Footnote 27 Rapp was immediately impressed with the quality of the land in the Middle Atlantic states, the character of the people, the tradition of religious freedom, the abundance of food, and the varied financial opportunities. He quickly abandoned his previous fixation on Louisiana and concentrated on securing property for the Society in Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland, or Ohio.Footnote 28

Rapp was particularly smitten with the lands of Ohio, calling on President Thomas Jefferson on July 12, 1804, in a failed effort to purchase forty thousand acres on the Muskingum River. Despite Jefferson’s desire to accommodate the migrants, Rapp’s request went unrealized for insufficient cash. Rapp petitioned Congress to have the time of payment extended on a tract of land in the Indiana Territory. The Senate passed a bill to sell a township near Vincennes, but it was defeated in the House by the Speaker’s tiebreaking vote.Footnote 29 Rapp faced pressure to find a spot to build his community, as three hundred of Rapp’s society onboard the Aurora landed in Baltimore on July 4, 1804.Footnote 30 Subsequent ships bringing hundreds more arrived throughout the fall of 1804, who along with other German separatists settled in several locations across Ohio and Pennsylvania, some forming rival communities to Harmony.Footnote 31 Finally, on October 17, a colorful German-American, D. B. Miller, persuaded Rapp to purchase from him 5,700 acres in Butler County, Pennsylvania (about twenty-five miles north of Pittsburgh). George Rapp could finally begin the project of building his first Sunwoman utopia on the banks of the Connoquenessing Creek: Harmonie.Footnote 32

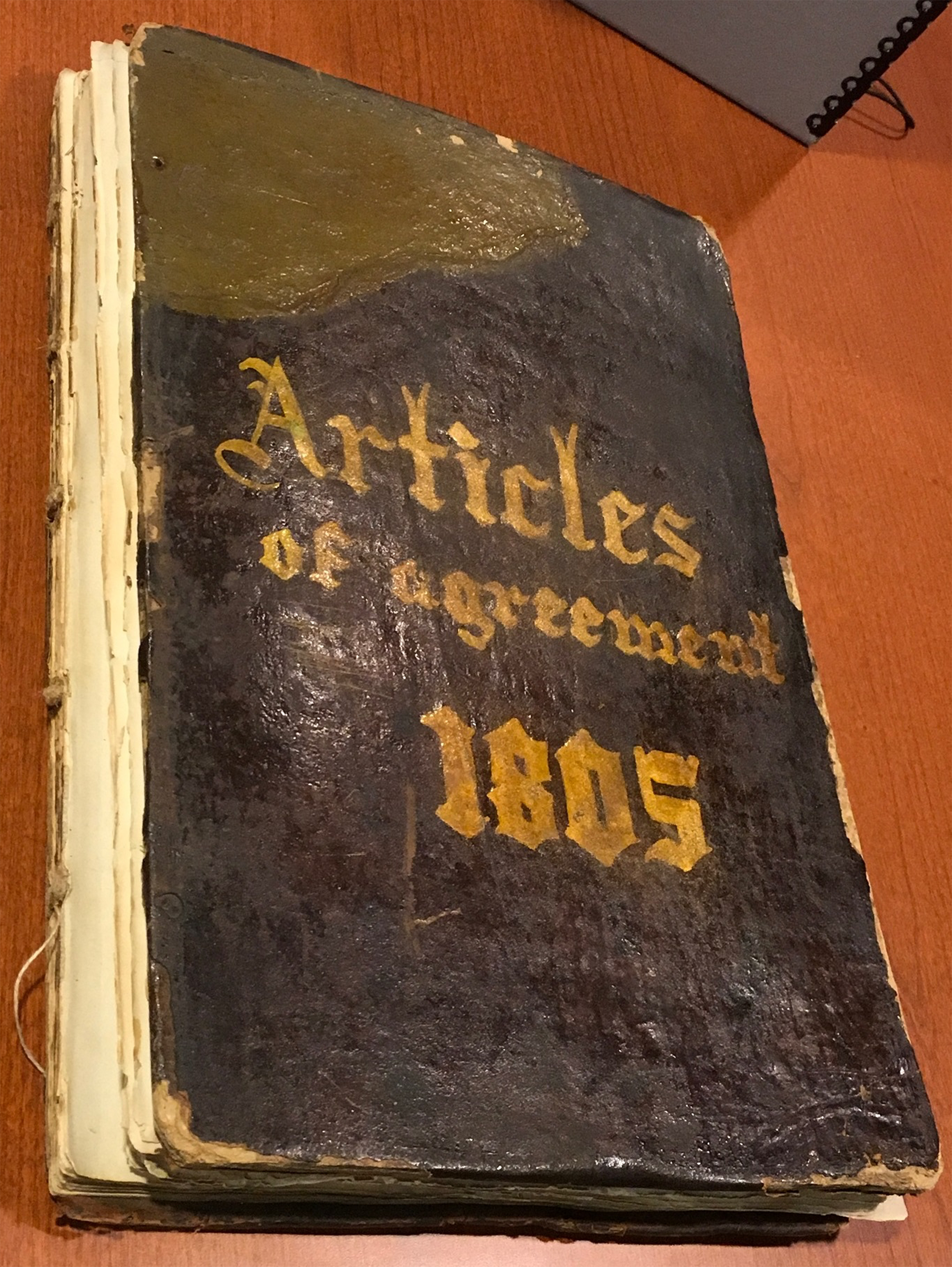

The emerging democratic and individualistic dynamics of early nineteenth-century America were especially troubling to Rapp because they were in tension with both his concept of the first-century church’s approach to private property and his theology of self-will. Consequently, the first article of the Harmony Society’s February 15, 1805, Articles of Association (Figure 2) stipulated that members of the Society would “Deliver up, renounce, and transfer all our estate and property consisting of cash, land, cattle, or whatever else it may be, to George Rapp and his Society in Harmonie, Butler County, Pennsylvania, as a free gift or donation, for the benefit and use of the congregation there, and bind ourselves on our part, as well as on the part of our heirs and descendants, to make free renunciation thereof, and to leave the same at the disposal of the superintendents of the congregation, as if we never had nor possessed the same.” (The articles of 1805 were probably modified later to include a provision for the return of personal property if one were to leave the Society, an element missing from the Articles submitted two years later to the Pennsylvania legislature on December 15, 1807, in the Society’s request for incorporation.)Footnote 33 The second article continued the communal spirit of the first:

George Rapp and his Society promise to supply the subscribers jointly and severally with all the necessaries of life, as lodging, meat, drink, and clothing, etc., and not only during their healthful days, but also when one or several of them should become sick or otherwise unfit for labor, they shall have and enjoy the same care and maintenance as before; and if, after a short or long period, the father or mother of a family should die, or be otherwise separated from the community and leave a family behind, none of those left behind shall be left widows or orphans, but receive and enjoy the same rights and care as long as they live or remain in the congregation, as well in sick as healthful days, the same as before, or as their circumstances or needs may require.Footnote 34

The communal provisions for individuals’ welfare and the promise of care as one aged and became less productive economically was significant in an era with few safety nets. In part, it reflected Rapp’s belief that society was unraveling and that true believers had a duty to care for all within their community. Referencing New Testament prophesies found in Mathew 24:2, Mark 13:2, and Luke 21:6, Rapp wrote, “You will know what faith can do when there is grace, as not one stone remained upon the other of Solomon’s temple, according to the word of Jesus, much less will there remain any of Babel’s temple, but all must fall which is called property, within and without throughout, Christ had nothing except that he served his brethren. So naked, so poor, so deprived of all things inwardly and outwardly the church of Christ must stand … so that no one likes to possess or hold on to anything that is his own.…”Footnote 35 Here, Rapp pinned the ills of early nineteenth-century society on private property and connected its elimination with true, purified communion. One can almost imagine Rapp railing against the corrosiveness of the speculative, individualistic capitalism advanced by financiers such as Andrew Dexter Jr.Footnote 36

Figure 2 Original Articles of Agreement (or Association).

More than a chief proprietor, George Rapp was a Christian “economist-philosopher,” responsible for all spheres of life in his commune: political, business, and spiritual.Footnote 37 Rapp & Associates reflected this, functioning as a corporation embedded into Winfred Barr Rosenberg’s definition of a “moral economy,” exhibiting the following:

-

1. The subordination of the individual to community norms

-

2. An internal system of exchange governed by “need” rather than profit and insulated from external exchanges

-

3. The absence of contracts and private property within the SocietyFootnote 38

A fourth characteristic of moral economies partially fits Harmony: a process of collective decision-making. In Harmony, George and his adopted son Frederick made all of the decisions, with communal assent, so it was similar to a moral economy from the perspective of an absence of individual decision-making. Collectively, these principles define Christian communal capitalism: a communal society organized along the lines of a traditional business, integrated into the market economy but distinguished by an absence of private property and the centrality of religion to its most basic organizational and philosophical principles. As George Rapp explained in his Thoughts on the Destiny of Man, communal life could never work apart from a spiritual motivation and foundation:

This can be rendered practicable, only by the sublime spirit of Christianity, which must influence the conduct of a large majority of the members, or nothing of the kind can ever be accomplished. The human heart must be warmed by the religion of Jesus Christ, exalted to its God, and transformed into his image, before it can be qualified for the pure enjoyments of that brotherly union, where the true principles of religion, and the prudent regulations of industry and economy, by their united influence, produce a heaven upon earth—A true HARMONY. Footnote 39

As we will see, Rapp’s certitude regarding the centrality of Christianity to the success of communal capitalist societies was consistently discounted by early nineteenth-century secularists, such as Robert Owen, who sought to extricate Harmony’s communal principles and industriousness from its religious dogma.

George Rapp was not only a chief proprietor and economic-philosopher, but also a patriarch in the Old Testament sense. Despite his stated goal of harmony and spiritual piety, Rapp’s powerful personality and autocratic tendencies made many enemies, especially as patriarchal norms gave way to the democracy and paternalism of the early republic United States.Footnote 40 As a disgruntled former member, Jacob Eckensperger, wrote to his Harmonist brother Friederich, “… I would rather live among the Indians, there I would not see such horrors as among you.…”Footnote 41 Accused of bullying, greed, and theft, Rapp was often at the center of the controversy over the Harmony Society.Footnote 42 As the chief proprietor, he autocratically determined the shape and character of the workforce, evicting those who did not adhere to his theology, religious discipline, or work ethic. Butler County records refer to a “riot” in 1807 when George and Frederick Rapp tried to evict some members of the Society and the individuals in question resisted.Footnote 43 He also consistently pursued his debtors in court. Christian mercy and grace rarely described the business principles and leadership of George Rapp.Footnote 44 Tragically, families struggled with Rapp’s psychological power, as parents separated and children mourned the breakup of their families in language that paints the Harmony Society in an unpleasant, even cultish light.Footnote 45

Nor did grace and mercy describe the business character of George Rapp’s chief business partner and adopted son, Frederick Rapp. Early on, it was clear that of the two men, Frederick possessed superior business acumen, and his role as Society treasurer soon expanded to operational head of Rapp & Associates. Whereas George was the unquestioned spiritual leader of the community, Frederick attended to the minutia of running the day-to-day business of Rapp & Associates, from ordering supplies, to collecting debts, and developing new ventures. Frederick quickly evolved into a businessman who aggressively built the Society into an efficient business enterprise through hard bargaining. Despite the pious nature of the commune, he was not afraid to employ power plays and tough bargaining tactics, including lawsuits, to advance Harmony’s economic position.Footnote 46

Harmony’s communal capitalist system quickly proved productive. Within five years, the Harmonists, now numbering 140 families, had built over 50 log homes, a 220 foot bridge, two barns, two gristmills (one with a three-quarter mile race), an inn/tavern, two oil mills, a tannery and dryer’s shop, two brick storehouses, two sawmills, a brewery, a fulling mill, a bee house, a large brick wine cellar, and a hump mill. In a symbolic union of religion and business, the upstairs of the church doubled as a granary capable of storing several thousand bushels of grain.Footnote 47 Not surprisingly, Rapp & Associates initially focused on agriculture, exporting corn, potatoes, wheat, whiskey, and wine, augmented by the contract work of its skilled laborers. Tradesmen included twelve shoemakers, six tailors, twelve weavers, three wheelwrights, five coopers, six blacksmiths, two nail smiths, three rope makers, ten carpenters, four cabinet makers, two saddlers, two wagon makers, twelve masons, two potters, one soap boiler, one hatter, one doctor, and one apothecary. Hiring out these tradesmen was an important early source of income, bringing Rapp & Associates $3,013 of income in 1809 and $5,921 in 1811—no small percentage of its total revenue. For context, wine and whiskey production only yielded $670 in 1808, so the hiring out income was certainly significant.Footnote 48 The output of the tradesmen was also vitally important in the cash-poor early nineteenth century, as Rapp used it to trade for commodities such as iron and gudgeons (cylindrical hinge devices used to hang shutters, among other applications).Footnote 49 In fact, by 1809, Rapp & Associates was proving increasingly profitable in these ventures, although the decision to produce whiskey garnered predictable criticism, as some outsiders concluded the Harmonists were “going down stream with the corrupted world, in order to get rich soon.”Footnote 50 However, whiskey was an important bartering item in western Pennsylvania and its manufacture continued.Footnote 51

Guests of Harmony often remarked on Rapp & Associates’ workforce, wondering how it encouraged industriousness, despite the prohibition on private property. As a curious New Englander, Samuel Worchester, put it to Frederick, “Many among us, who think a Society established upon principles analogous to those of the Harmonists, would be useful and delightful, if possible, believe also that a prohibition of individual and exclusive property would operate as an inherent and irrestitable [sic] principle of disorder & decay; and consequently, that all schemes, which act upon such a prohibition must be visionary and impractible [sic].… I am at a loss to know what necessity you find of stimulating its members to exertion.…”Footnote 52 Below Frederick, superintendents directed artisans, factory workers, and farmers. Family units lived in a simple house on an acre lot. Families maintained their own milk cows, hogs, and poultry, while the Society furnished all else. The output of a family’s labor, excepting that involving one’s livestock, went into the Society’s common economy.Footnote 53 Frederick stressed the community’s solidarity and unity because, according to Frederick, as “the interest of each lies in the whole,” each worked “according to ability.”Footnote 54 He also stressed spiritual and religious factors, agreeing with Worchester that self-interest plagued humans, a manifestation of humanity’s Fall (Genesis 3). Frederick argued that the key to Harmony’s successful transition to communal living was a desire to care for one’s brothers and sisters and for the good of the community, an attitude that could only be fostered by “the Religion of Jesus, which teaches to renounce and do without whatever may cause a hindrance, to obstain [sic] from what is only a habit and no necessary of Life and deny self to be usefull [sic] for others … all Schemes to form Societies similar to Harmonie without practicing the Religion of Jesus and prohibiting indivitual [sic] property have gone to wreck.”Footnote 55

Religious belief also informed Harmony’s overarching attitude toward work. Frederick argued that before the Fall the nature of men and women was “activity”, that “this primitive Instinct exists yet in the essence of Man, and (becomes predominant) as soon as the inner feeling Mediately [sic] or immediately are unfolded through the Light of truth, then this Stimulus for activity and Social life awakes with it.…”Footnote 56 Not only was work written into humanity’s fabric, the Society earnestly believed in the eternal significance and urgency of its holy endeavor. The Harmonists believed their work was ushering in the kingdom of God and would form the foundation of Christ’s millennial rule. This created an acute sense of eternal significance and a strong sense of urgency. On the other hand, Frederick allowed that if a member did not have this set as his or her “chief object,” then he or she would find submission to his or her superintendent very difficult.Footnote 57

There was no prescribed workday, although outsiders commented that laborers worked long and hard at Harmonie. Despite visitors’ wonder at the work ethic of Harmonists, members of the Society contended, “they did not work hard, but were always working at their leisure & just as they liked it.”Footnote 58 Likewise, there was no limit to sick days. On the other hand, Rapp & Associates did not pay wages.Footnote 59 Men and women spoke Swabian, wore simple, homespun, uniform clothing, and shared work in the field. J. S. Buckingham, a member of the British Parliament, visited the Society in 1840 and provided a detailed record of Rapp & Associates’ workforce, observing their “ordinary” dress of gray trousers, hats, and coats, accented by lilac or brown waistcoats. The women wore dark colored, lightweight, coarse, woolen, long-sleeve gowns with a silk or cotton handkerchief over the shoulders, complete with white or checked apron and a black (working) or white (Sundays, evenings) hat. “Simplicity, neatness, comfort, and economy” also characterized their grooming habits, which for men meant beards with shaved cheeks and lips and long, white locks among the elderly. Women parted their hair in the middle, pulling it tight underneath their hats.Footnote 60 Frugality, simplicity, and tradition dominated the Harmonists’ habits and manners. Isolation from the cultural trends of the US early national period reinforced the Harmonist tendency to preserve the cultural norms of late eighteenth-century rural Württemberg.

Women working in the fields dismayed American geologist and ethnologist Henry Schoolcraft, who thought such work inappropriate for young girls and women. Others found such arrangements enlightened. Robert Owen’s friend Donald MacDonald applauded how genders mingled in Harmonie’s fields.Footnote 61 Despite his reservations about the employment of women, Schoolcraft described Harmonie’s labor system as a masterful division of labor in which “every individual is taught that he can perform but a single operation.” Schoolcraft suspected this was the key to Rapp & Associates’ efficiency and innovation, because “no time is lost by changing from one species of work to another: the operator becomes perfect in his art, and if he possess any ingenuity, will contrive some improved process to abridge or facilitate his labor.”Footnote 62

It was not all work for the Harmonists. Visitors also remarked upon how singing was an important part of the cultural life of Harmonie, and the Rapps seemed to take special pride in the end of the workday singing when they showed off the Society to outsiders.Footnote 63 Order, discipline, efficiency, joyful singing—it all added up to the capitalist’s dream workforce. Of course, presiding over all of this, and the ultimate source of labor discipline, was George Rapp, who both Frederick and visitors described as an all-powerful “king-priest” of the community in the order of Melchizedek.Footnote 64 Visitors often did not see or comprehend the darker side of this patriarchal authority structure.

Much of this criticism derived from the character of George Rapp himself, powerful in personality and stature. There was no question who was in charge at Harmonie. Like a twenty-first-century Silicon Valley CEO, critics accused Rapp of bullying, greed, megalomania, and even fraud.Footnote 65 In an otherwise complimentary account of a visit to the Society in 1831, Moravian botanist David von Scheweinitz described George’s rule as absolute, and that he “speaks in a rough and commanding tone with everybody.”Footnote 66 Rapp’s imposing stature of over six feet further reinforced his dominant personality, described by a visitor as projecting an “erect and robust” frame, “ruddy” complexion, framed by long white hair and beard. Even late in life he still struck people as “the most vigorous and most venerable man at eighty-four that could be seen or conceived.”Footnote 67

Internal friction transcended Rapp’s personality. Initially, dissent over the imposition of a communal structure at Harmonie induced some followers to break with Rapp and form a rival settlement at Columbiana, Ohio, where they maintained individual property rights.Footnote 68 The remnant only gradually embraced the spirit of communalism, despite the presence of many poor and destitute members.Footnote 69 Rapp struggled to tame the pride of the largest contributors to Harmony’s common treasury, so much that when the group migrated to Indiana, he had the records destroyed.Footnote 70 Many individuals decided communal living was not all it was cracked up to be, and after departing Harmony, they sued to recoup their initial contributions to the communal treasury.Footnote 71 As one critic succinctly put it, Rapp preached a doctrine that “stinks.”Footnote 72 In return, George Rapp grumbled about families that “wanted a comfortable living,” including meat, which was scarce in Harmony’s trying initial years.Footnote 73

Departing members routinely demanded the funds they contributed upon entering Harmony, which in the early years Rapp could not pay, even when he was so inclined. Frederick acknowledged in 1822 that “poor” members were supposed to receive a donation upon leaving, but the actual implementation of this was inconsistent and controversial. For one family that departed over its want of a more “comfortable” lifestyle, George was able to repay the family thanks to a loan from a friend, something George attributed to divine deliverance.Footnote 74 Often with little other recourse, departing families sued to recoup their initial contributions to the communal treasury and unpaid wages for their years of work on behalf of Rapp & Associates.Footnote 75 The legal disputes sometimes lasted years. Consequently, the Rapps became much more careful in admitting new members because they felt too many people “deceived” them into believing they could adhere to their way of life, only to find “the path to follow Jesus too narrow.”Footnote 76 Not only was the prospect of reimbursing departing members a problem, but Frederick lamented the loss of productive, skilled workers and time required to train their replacements.

External Relationships: Neighbors, Customers, Local, State, and Federal Government

The year 1810 was significant because it marked Rapp & Associates’ entry into the textile market, with the purchase of Merino sheep (from Italy) and construction of a wool factory that, when completed, contained a wool-carding machine, six spinning jennies, and sixteen looms for the production of wool cloth.Footnote 77 In addition to milling its own wool, in less than two years, regional herdsmen were petitioning the Society to process their wool.Footnote 78 Frederick was demonstrating his growing expertise in evaluating the quality of wool, while purchasing a cotton-carding machine to expand production into that fabric as well. The carding machine was a source of much frustration. Frederick spent most of 1812 trying to acquire the carding machine—it was shipped to Harmonie in November of 1812. However, the Society struggled to bring it online, finally succeeding the following June.Footnote 79 Accordingly, the Rapps showed increasing concern with their access to the market, specifically the all-important postal routes. The Rapps understood that the postal service was vitally important to Rapp & Associates’ economic success, hence their request that the postmaster general establish a post office in Harmonie and incorporate the new village into existing postal routes. The Rapps also petitioned for the removal of their regional postmaster over assertions he was not fulfilling his duties properly.Footnote 80

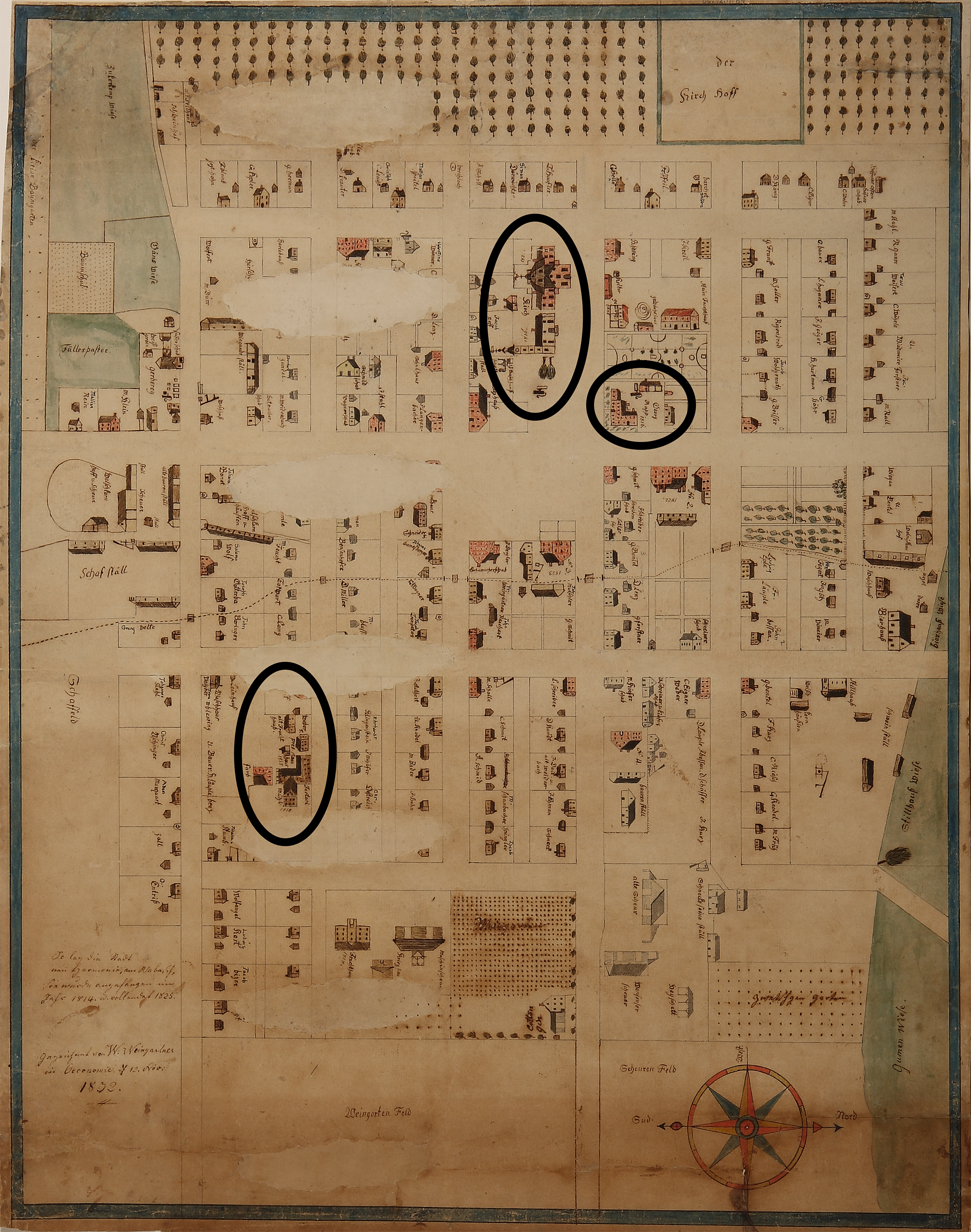

By 1811, Harmonie, Pennsylvania, consisted of approximately 9,000 acres (2,500 cultivated), 800 persons (100 of which were farmers), and Rapp & Associates had dramatically increased its net worth from approximately $20,000 to $220,000, a sum that attracted attention on both sides of the Atlantic thanks to Scottish mapmaker John Melish’s widely read account.Footnote 81 The material success of Rapp & Associates was reflected by the Rapps’ large, attractive homes (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3 Goerge Rapp’s home (1808), Harmonie, PA

Figure 4 Frederick Rapp’s home (1811), Harmonie, PA

However, George and Frederick were discovering that further expansion was difficult. Early attempts to market their wool cloth in Baltimore met with resistance, as merchants deemed Rapp & Associates’ product too expensive and not of the right type to be competitive with competing wool textiles.Footnote 82 Rapp & Associates’ woolens were more successful in Philadelphia, at least when its colors conformed to current fashion. For example, in 1812, bright green was not in style and Rapp’s agent, Godfrey Haga, recommended darker green as being more “fashionable.”Footnote 83 The proximity to Pittsburgh made it a natural destination for Rapp & Associates’ manufactures, iron as well as textiles.Footnote 84 Frederick continued to engage the more resistant markets, such as Baltimore’s textile and whiskey markets, protesting that Rapp & Associates’ textiles had acquired “such a good renown … that it was sold till now as fast as we been able to make it.”Footnote 85 By fall 1813, even Pennsylvania’s governor was joining the ranks of those who admired how Harmony combined “practical Christianity” and “flourishing manufacturers.”Footnote 86 Frederick used the growing notoriety of Rapp & Associates to establish relationships with other early nineteenth-century businessmen, such as the Du Ponts, who referred to Frederick Rapp as “owner of the Cloth Factory at Harmony.”Footnote 87 As a sign of the growing reputation of Rapp & Associates’ textile industry, Frederick fielded an increasing number of requests to buy his sheep and process the region’s wool from as far away as Kentucky.Footnote 88

The acclaim of Pennsylvania’s governor represented a dramatic turnaround for Harmony’s public image. Suspicion and alarm had greeted their arrival in the western part of the state in 1804. Attempting to legally secure their communal and economic endeavors, the Rapps submitted a request for incorporation in 1807. The Pennsylvania Legislature reacted with alarm. Noting that the prohibition on property ownership was potentially in violation of federal and state constitutions, a committee report concluded that granting incorporation to the Harmonists would be “extremely impolitic, inasmuch as it would tend to damp and discourage that spirit of individual exertion and enterprize [sic], that self-dependence, that conscious dignity and consequence, which each individual should attach to himself in a free republic.”Footnote 89 Harmony’s request never made it to a vote, and neither Harmony nor Rapp & Associates was ever incorporated.

The first hint of a westward move appears in reports George Rapp sent to Frederick dating to April 1814, as the Rapps weighed what they felt were their declining economic prospects in western Pennsylvania.Footnote 90 George was on a trip investigating new sites for the Society, because as Frederick wrote two years later in reflection, western Pennsylvania had grown crowded with “quite a few inhabitants and no more land could be purchased except at very high prices.… The climate was not quite suitable to us because the winter was somewhat too long which made the raising of sheep and viniculture somewhat difficult.…”Footnote 91 Additionally, Frederick did not like how Harmonie, Pennsylvania, was located twelve miles from navigable waters. Critics mused that the real issue was that George Rapp feared losing control of his followers as the surrounding population increased.Footnote 92 By May 9, 1814, after touring sites in Ohio and Kentucky and not finding any that fully satisfied, George and his team of two other Harmonists finally executed a series of purchases for land on the banks of the Wabash River that would become the Society’s spacious new commune in the Indiana Territory. The second Harmonie was approximately twenty-five miles northwest of the newly founded village of Evansville (in the southwest corner of Indiana). Initially, the purchase was for 2,435 acres, although within one year, the new settlement encompassed 17,000 acres. By July 1816, the second Harmonie encompassed over 20,000 acres.Footnote 93

Even as the Society was selling Harmonie, Pennsylvania, and moving its nearly eight hundred commune members westward, the Rapps planned an expansion of their burgeoning industrial production. (Harmonie eventually sold for $100,000, although the Society never realized the full amount. It was an especially difficult time to collect payment, as money was scarce thanks to the disruption of the War of 1812.)Footnote 94 According to Frederick, the determining factor in selecting the new location was a place where “culture, trade, and situation would offer more advantages for factories of various type.”Footnote 95 George assured Frederick that the Wabash River would afford them newfound access to New Orleans, and from there to ports in the West Indies, England, and Europe. A companion with George on the advance scouting mission, John L. Baker, a founding member of the original settlement in Pennsylvania, also stressed the nearby coal banks and potential for waterworks, wood for building, and the need to buy up as much land as possible before the Society’s advertised move caused the local land prices to rise prohibitively.Footnote 96 Frederick responded that they should buy land on the other side of the Wabash (Illinois Territory) in order to “have the command of the River.”Footnote 97 He was certainly not moving from western Pennsylvania to abandon the market. If anything, the Rapps were simply doing something other early Americans were considering: taking advantage of the ongoing displacement of indigenous peoples in the Northwest Territories to make money.Footnote 98

After opening a store (licensed by the Indiana Territory in December 1814), the Rapps focused again on linking Harmonie to the federal postal service and rerouting water sources to serve the new commune’s industry.Footnote 99 There was a sense of urgency as current customers were still looking to Rapp & Associates for their textile needs even while it was nowhere near ready to resume production.Footnote 100 Congress helped by altering the Vincennes to Shawneetown postal route so that it passed through Harmonie (April 20, 1816) and established a post office at Harmonie which opened in early September, 1816.Footnote 101 Although by March 1815, the new settlement had built log homes for every family, tilled over eight hundred acres, including orchards and vineyards, resumed alcohol distillation, and started construction of a sawmill, Rapp & Associates was still far from resuming its textile manufacturing. Compounding things was the seasonal unpredictability of neighboring creeks, which drove Frederick to purchase a steam engine from Pittsburgh to power Harmonie’s mills. Taking delivery of the engine (and getting it working) was a struggle, and the delay caused financial loss as Rapp & Associates continued to struggle in bringing its textile production back on line. River ice impeded initial delivery of the steam engine. Then when replacement pieces for the carding machine were not included on the boat carrying the steam engine, Frederick resigned himself to another four to six weeks of the carding machine sitting idle. Even this proved to be false optimism, as the engine did not become operational until mid-May 1816, limiting Rapp & Associates to finishing cloth left over from the stock brought from the original Harmonie.Footnote 102

In fact, just getting a letter to and from southwestern Indiana was often surprisingly slow, especially in the winter, as Frederick’s associates discovered when a letter he mailed on January 6 did not arrive in Pittsburgh until February 9.Footnote 103 Five weeks, the standard time frame for a letter to travel from Harmonie to points in Pennsylvania, was fast compared to the saga of the letter he sent another associate on January 17, which did not arrive at its destination in western Pennsylvanian until April 22.Footnote 104 Unprofessional postmasters and letter carriers only exacerbated the situation. For example, two postal carriers on the route between Harmonie and Corydon were fired for incompetence. During this time, Frederick complained that the St. Louis postmaster was similarly inefficient.Footnote 105 By 1822, Frederick had grown so sick of the poor mail service that he petitioned Indiana’s governor to intervene, writing “… the injury occasioned through neglect of Postmasters & Mail carriers in this Western District is very great to its inhabitants and particularly to those engaged in Mercantile business is so obvious, that perhaps it may not have escaped your attention before now.”Footnote 106 For businessmen such as Frederick, timely postal service was of utmost importance in the expanding market economy. This commercial imperative animated Frederick’s complaint to Governor Jonathan Jennings: “Not long since I recd. Two Letters at different times from Cincinnati (Ohio) one four-and the other five Month on the Way coming, Each containing urging matters of great importance … at present we have been for three Weeks without a Mail from Corydon, and are thereby debarred of every Necessary Commercial advise from the East.…”Footnote 107

In addition to communication problems, the landscape of credit in the western territories was vastly inferior. The Harmonists left a state in Pennsylvania that by 1830 possessed nine times the bank money per capita and fourteen times the bank credit as Indiana could claim.Footnote 108 Unsurprisingly, Frederick’s business correspondence is replete with frustration over the confusing, unreliable, and occasionally nefarious currency landscape of the West, which probably led him to become a stockholder in the Bank of Vincennes, which became the State Bank of Indiana in January 1817.Footnote 109 Attempting to stabilize the local credit system, Frederick was also heavily involved in organizing local branches of the state bank, including the Farmers’ Bank of Harmony. The branch banks at Posey and Gibson Counties (which Harmony overlapped) were both authorized $10,000 of capital stock, and Frederick was named director of the Posey branch.Footnote 110 This is just one of many examples of how the Pietists of Harmonie enmeshed themselves into the market economy, even as they fought to maintain their purity through cultural isolation.

Frederick’s involvement in the state banking system is particularly interesting given the Society’s misgivings toward lending and interest. In a December 3, 1821, letter, Frederick declined to extend a loan to the founder of Vandalia, Illinois, explaining the practice was “against our Rule.”Footnote 111 In another instance, Frederick refused a loan to the Governor of Indiana, even though just days before Frederick himself proposed to loan the State of Indiana his stock in the Bank of Vincennes. This was quite a scheme, as Frederick’s proposal was to loan back to the state its own bank’s stock in payment of debt owed the state bank! The terms of the loan were ultimately beneficial to Rapp & Associates because it recouped $4,000 worth of worthless bank stock in exchange for a loan to the State of Indiana, while erasing debt. Clearly, this loan was all about recovering Rapp & Associates’ losses from the failure of the disastrous Bank of Vincennes, more than concern for the bank’s stability.Footnote 112 A few years later, Rapp & Associates was again lending $5,000 to the state at nearly 15 percent interest.Footnote 113

Rapp & Associates loaned money to public institutions, just not private individuals. Even close business associates, relatives of George Rapp, and longtime friends of the Society need not apply. (The one exception seems to be a loan to the Society’s lead lawyer, Walter Forward. The fact that it occurred after Frederick died was probably not coincidental. After Frederick’s death, R. L. Baker recorded a loan of $1,000 to Forward, made during the Panic of 1837.)Footnote 114 Eventually, Frederick even dispensed with Rapp & Associates’ practice during its Indiana days of extending credit to its business partners.Footnote 115 The practice of institutional loaning was not just a necessary product of the financial landscape of Indiana, but continued after the Society’s eventual move back east, such as when Rapp & Associates loaned the city of Pittsburgh $20,000 and the city of Wheeling $2,000.Footnote 116 Frederick offered a business rationale behind Rapp & Associates’ lending policy: It preferred to reinvest its capital into the Society and its business operations, rather than loaning it out to interested individuals, especially given the poor state of the economy in the 1820s.Footnote 117 Harmony’s interest in the economic well-being of its community was limited by its eschatology, which saw little benefit in helping its neighbors because they would not survive to see the new millennium. Instead, these investments served Harmony’s mission in building the foundation of the new “divine economy.” Consequently, it needed to be as robust and well positioned as possible to make its way in the remade earth to come. Of course, this indifference toward Harmony’s materially struggling neighbors led to friction and played a significant role in the Rapps’ decision to move the Society back to western Pennsylvania.

The practice of lending to cities and states was not the only surprising way in which Harmony inserted itself into the emerging institutional framework of the early republic United States. In 1816, the Indiana Territory called for a constitutional convention, and Frederick was elected as one of forty-one delegates, representing Gibson County.Footnote 118 His role at the convention included serving on the “committee relative to the executive department” and “committee relative to the militia”—the latter ironic, considering Harmony frequently paid a territorial exemption tax to excuse the male members of the Society (between eighteen and forty-five years) from military service, which they opposed on religious grounds.Footnote 119 Frederick also played an important role in picking the site of Indiana’s new capital city, serving on the board of commissioners that ultimately selected Indianapolis.Footnote 120 This foray into politics was not an exception, but a consistent trait of Harmony in both Pennsylvania and Indiana. The Society was active in voting, to the point that its neighbors complained of block voting: Harmonists typically voted how the Rapps instructed. The common denominator, like its policy on lending, was economic. If the Rapps saw an opportunity to shape their regional economy to their advantage, they seized it. Accordingly, they were reliable supporters of the “American System” of national banking, tariffs, and internal improvements. Conversely, they were ardent and vocal opponents of Andrew Jackson’s economic policies.

While Frederick was absent at the Indiana state convention, Harmonie received the first of many curious visitors searching for a way to reconcile republican values with successful manufacturing. This time it was the oldest such society in America, the Shakers, who had established a settlement in 1810 called West Union, near Vincennes.Footnote 121 The Shakers were only the first of many pilgrimages to Harmonie in the Indiana Territory to learn how the Rapps were fusing industry, charity, equality, and spirituality in the wilderness. Those who could not visit in person attempted to satisfy their curiosity by correspondence.Footnote 122 As historians such as John Kasson have pointed out, many early Americans embraced technology and the market economy, but searched for a way to avoid the squalor of Britain’s industrial cities. Lowell, Paterson, and Pawtucket are the places that figure prominently in the standard narrative about the attempts to establish industrial order in early America, a historiography that neglects the alternative example of the two Harmonies, and the third site, Economie.Footnote 123 Kasson argues persuasively that towns such as Lowell were an attempt to purify industry and make it morally acceptable to skeptical Americans. Similarly, the Harmonists sought this goal, albeit through a Pietistic approach.Footnote 124

For many early nineteenth-century Americans, Harmonie offered a viable model for industry and society. Economist and publisher Mathew Carey wrote in one of several publications that raised Harmony’s profile in England and America, “The settlement of Harmony … is probably the only settlement ever made in America, in which from the outset agriculture and manufacture preceded hand-in-hand together.”Footnote 125 Similarly, the curious merchant John Bedford wrote in 1816, one year prior to entering into business with Rapp & Associates, “I have examined with admiration … the product of the ingenuity and industry of your society on the Wabash … the equal perfection at least, exists among your society, in other branches of mechanical industry & the usefull [sic] arts.” Bedford hoped and prayed that “they may diverge and be diffused throughout our land, contributing to & securing, with accumulating force, our national independence and individual comfort & happiness.”Footnote 126 What these visitors described matches what one historian has termed “peasant republicanism,” which grew out of Pietism and was characterized by “reciprocal relationships and localized mutual obligations” and “a delicate balance of obedience and vigilance.”Footnote 127

What Bedford and other visitors found upon visiting was that by spring 1817, George Rapp resided in the “best” brick home in Indiana, and Harmonie had resumed manufacturing both wool and cotton textiles.Footnote 128 As Tamara Plakins Thornton demonstrates, early nineteenth-century economic tourists valued aesthetics, and visitors to Harmonie marveled at its order, cleanliness, and construction of its “pretty little town,” noting as well that George Rapp and his closest advisors seemed to live better than his followers did.Footnote 129 This reveals one prominent characteristic of the Society’s communalism: inequality of dwelling places. Frederick and some of the previously wealthy members of Harmony lived in much nicer homes than those of the ordinary members. Old Economy Village, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission’s caretaker of the Harmony records, explains this discrepancy by comparing the Rapps to other leaders of their era and concludes they were living simply in comparison and that the other inhabitants of Harmonie expected their leaders to have a higher standard of living.Footnote 130 The reality was that visitors sometimes discovered the material equality at Harmonie was not what they had expected.

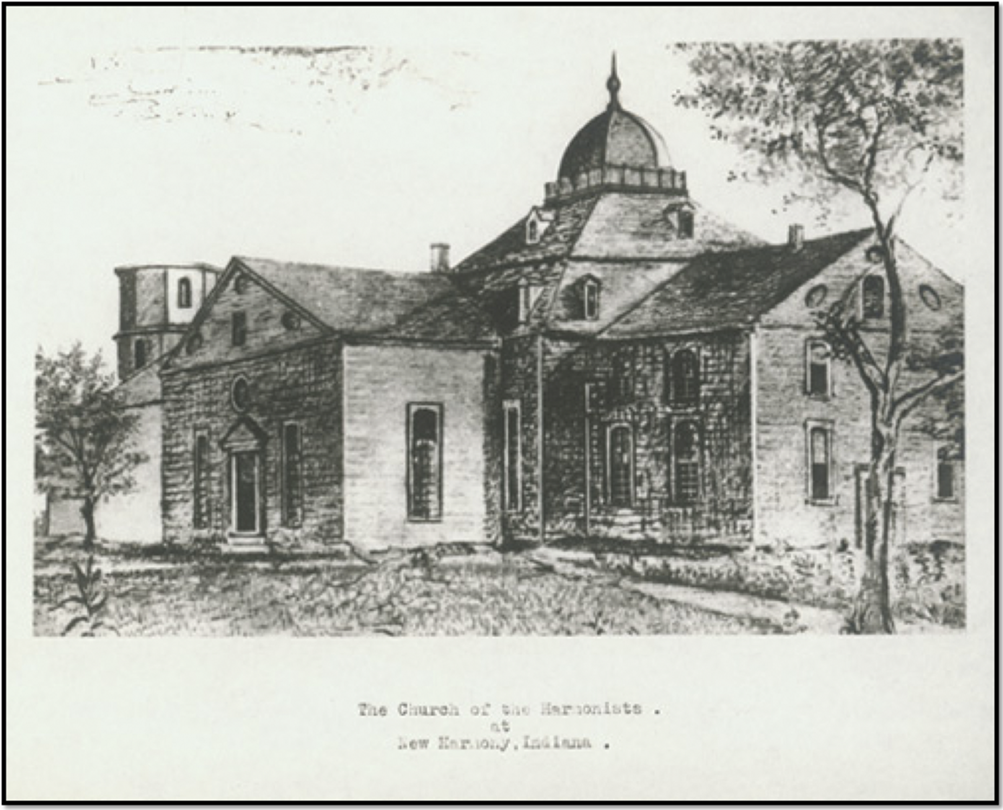

Visitors appreciated Harmonie’s order. Surrounded by the Society’s cornfields, the village, estimated at 600 yards long and 400–500 yards wide, was organized along two main north/south (Mount Vernon to St. Louis) and east/west (Shawneetown to Vincennes) running streets that shaped the community into a series of squares, formed by two additional north/south and four other east/west parallel streets (Figure 5).Footnote 131 Symbolically, two churches sat at the center of Harmonie (Figures 6 and 7), the larger brick Greek cross structure alongside the first, wooden church that proved too small and hot as the size of the Society grew during its time in Indiana. (Reflecting the Society’s embrace of alcohol, the second church possessed two wine cellars.)Footnote 132 As a traveling companion of Robert Owen described, taken in whole, Harmonie’s aesthetics served to bolster the argument for the superiority of communal life, particularly for “a traveler just emerging from a forest where little or no improvement has taken place, and remembering the many days he has spent in wandering through a thinly peopled & badly cultivated country.…” Once Harmonie came into view, the eye-pleasing panorama of a “flourishing village, and picturesque river winding through a magnificent forest, is highly gratifying,” sparking an intense curiosity in the visitor as to what ideology underpinned such an orderly, industrious community of people.Footnote 134

Figure 5 Harmonie, IN, sketched by W. Weingartner (c. 1825).

Figure 6 The second church at Harmonie, IN. Sketched by Charles Alexandre Lesueur.

Figure 7 Greek Cross Church Plan (undated).

It was not just the order and beauty of Harmonie that struck visitors. The Society’s technology always impressed its guests, particularly its thirty-horsepower steam engine which carded, combed, and cleaned the wool before spinning on a machine run by children.Footnote 135 The engine then powered the weaving and cutting processes. An eight-horse-driven threshing machine was equally imposing, also operated by children. The Society operated a horsepowered cotton gin as well.Footnote 136 (Harmony was often a dumping ground for orphans, but rather than hire them out, as outsiders frequently propositioned Rapp & Associates, Harmony instead trained them in a trade and put them to work within the Society.Footnote 137) To deal with wool-processing demands, in 1818 Frederick purchased two weaving looms (to produce stockings) from Frankfurt, Germany, and explored construction of a steamboat for trade with New Orleans.Footnote 138 Previously, at the first Harmonie, Frederick constructed a first-of-its-kind sheering machine, one that was the envy of other manufacturers.Footnote 139 He also obtained a fire engine and purchased a significant share in the nearby Bassenheim Furnace and Iron Works.Footnote 140 The marriage of technology, agriculture, cleanliness, and order always enchanted visitors, such as German nobleman Ferdinand Ernst, patron of Ludwig von Beethoven, who declared Harmonie, Indiana, “the most beautiful city of western America.”Footnote 141

Visitors such as Ernst, who visited Harmonie during the Panic of 1819, were able to measure how Christian communal capitalism weathered economic crisis, mitigating what Cathy Matson has termed “the ambiguities of risk” in the early republic.Footnote 142 Driven by a combination of land and currency speculation, the rapid expansion of credit by central, state, and local banks, and exacerbated by the Bank of the United States’ decision to restrict credit and Britain’s ban on US trade with the Caribbean, countless farmers, businessmen, and merchants, experienced economic ruin. Locally, Frederick struggled with the lack of circulating currency, and specifically worried about the health of the Bank of Vincennes. As it collapsed, he used his status as a director to secure outstanding debts owed the Society from the Bank’s debtors before the US Treasury could seize the Bank’s assets.Footnote 143 By summer 1821, the market was still depressed, constrained by the currency crisis of the West and exacerbated by abnormally low water levels, which collectively made trade extremely difficult.Footnote 144

Ernst and other visitors during the Panic found Harmony experienced comparatively little pain during economic depression, apart from falling prices for its agricultural and manufacturing products and difficulty paying debts due to the failure of many of its business associates and customers to pay debts owed to Rapp & Associates (both due to lack of circulating currency). Throughout the crisis, Rapp & Associates continued to operate two water-powered sawmills, two grinding mills (one water, one steam), one oil mill, one hemp mill, four wool carding machines, two cotton carding machines, four hundred wool spindles, 120 cotton spindles, four shearing machines, eleven weaving looms (wool and cotton), and four stocking weaver looms.Footnote 145 It was by far the most impressive industrial center in the western U. S. By pooling resources, reinvesting Rapp & Associates’ profits into the Society, and avoiding risky financial deals and loans, the Harmony model offered an alternative to the speculative, individualistic capitalism characterized by figures such as Andrew Dexter Jr.Footnote 146 Here the religious views of the community expressed themselves economically, as the Rapps took a long view, with the new millennium at the forefront of their planning, not the individualistic get-rich-quick schemes that led to many of the cautionary tales of the early American capitalist system. Despite the downturn in business, no one was starving, Rapp & Associates was not reduced to selling assets to cover debts, and there was no unemployment, unlike many other places in America in 1819.Footnote 147 Harmony’s communal capitalist model certainly offered undeniable advantages in times of economic crisis, even as Frederick stressed how hard the depression hit the western states and territories.Footnote 148

Conclusion: Christianity, Communalism, and Capitalism

The beginning of Harmony’s end in Indiana came unremarkably, in the form of a letter of inquiry from the Welsh industrialist, social theorist, and utopian, Robert Owen. Owen’s awareness of the Harmony Society demonstrates the notoriety it had acquired by the 1820s. Owen was specifically interested in how it addressed the “practical inconveniences which arise from changes to society from a state of private to public property.…”Footnote 149 It was supremely ironic that Owen was seeking wisdom from a religious group, considering he viewed religion as “absurd and irrational” and, along with marriage and private property, “the only Demon, or Devil, that ever has, or most likely, ever will torment the human race.”Footnote 150 Owen celebrated human reason, a “mental revolution,” and an optimism that once evils such as religion were discarded, the true grandeur of the human soul would express itself, spreading happiness from “Community to Community, from State to State, and from Continent to Continent.”Footnote 151 Despite his disdain for the religious and social organization of the Society, Owen’s son claimed that Harmony fascinated his father because “their experiment was a marvelous success in a pecuniary point of view.” He marveled that the Society went from poverty “in twenty-one years (to wit, in 1825) a fair estimate gave them two thousand dollars for each person, -man, woman, and child; probably ten times the average wealth throughout the United States.…”Footnote 152

At the same time, the location of their second commune was giving the Rapps buyers’ remorse. Although the climate of southern Indiana was better than western Pennsylvania for some types of agriculture, it was not better for viniculture, and Frederick increasingly complained of the lack of market access in Indiana.Footnote 153 Both he and George had come to realize that Rapp & Associates needed a site located on a major river such as the Ohio, and near to a large city such as Pittsburgh, in order to participate more effectively in the East Coast’s textile marketplace.Footnote 154 Whereas George was willing to admit this privately to Frederick, in public he was more opaque on the motivations for the move, particularly in his discussions with Robert Owen over the sale of Harmonie. To the latter, George avoided material explanations and emphasized the spiritual, asserting that divine revelation had foretold and directed him to lead the move back to Pennsylvania. The most he would divulge was that the climate was not well suited to their Society, and that they tended to move every ten years to keep life fresh and challenging. As the Owen party journeyed to Harmonie, two of his entourage recorded that the public suspected instead that the Society was moving back east because Harmonie was “unhealthy” land.Footnote 155 On May 4, 1824, the Society purchased a new plot of land approximately eighteen miles from Pittsburgh (ironically, only fifteen miles from the original Harmonie).Footnote 156 The Society began planning its move, even before completing the sale of Harmonie to Robert Owen.Footnote 157

This irony—that Harmony moved from western Pennsylvania to seek a fortune in the West, only to return to western Pennsylvania—is one of the more intriguing parts of the Harmony story. Harmony’s move did not avoid the tensions encroaching upon them at the original Harmonie, as the Society experienced as much conflict living with its neighbors in Indiana as it had in western Pennsylvania. Likewise, the idea that Rapp & Associates could continue to engage the market more effectively in the West quickly proved erroneous. Harmony was ahead of its time, moving to Indiana before the construction of a more complete transportation infrastructure, and then moving away just as these “internal improvements” were beginning to materialize (such as the Erie Canal, finished in 1825). Out in Indiana, Rapp & Associates experienced the worst of the market in terms of lack of infrastructure and a horrendous credit and banking landscape. Spiritual reasoning aside, the state of the early national period economy in the early 1820s western United States made the decision for the Rapps quite easy. If they were to achieve their divine financial goals, they would have to move back east.

Even though the Rapps were frustrated with their Indiana location, accounts of visitors had stirred the interest of secularist utopians such as the aforementioned Robert Owen and his feminist friend, Francis Wright. Owen had big plans for Harmonie—it was central to his plans to reshape American society radically along the lines of his vision of secular communalism.Footnote 158 The influence of Hamony on Owen is evidenced not only in Owen’s name for his Indiana commune, “New Harmony,” but also in the naming of Owen’s second and last community in Hampshire, England, “Harmony Hall.” Frederick similarly provided Wright counsel on how to get her free love, emancipationist utopia, Nashoba, off the ground.Footnote 159 Privately, George Rapp scoffed at the naivete of secularist utopians, even as he provided them earnest advice. It was unthinkable to the Harmonists that a communal capitalist model could succeed divorced from its religious character, which was the central point of the Harmony mission in the first place. As George declared to Liverpool merchant and friend of Owen, John Finch, “The only binding principle in Communities is religion, and that Communities cannot prosper without it.”Footnote 160 After reading Owen’s declaration of the need to free humans from the chains of religion, Frederick wrote that Owen was a fool because he could not overcome the consequences of human fallibility, entrenched since the Fall of Adam, “Do we not know from history and from God’s revelation in the Bible, as well as from our own experiences, that our first parents lost their balance … although many by far greater men arose than 100 Owens, and they all were not in a position to restore the original balance.”Footnote 161 Communal societies asked people to do things that apart from divine intervention, were just not within the realm of human capabilities. A close confidant to George summarized his opinion of Owen’s assumptions, “… George Rapp thinks that whoever attempts to bend men into a community of interests upon any other grounds but a strong religious feeling, will not succeed. It is religion gives peace here … and keeps the mind clear and steady.” He argued that the eternal destiny of believers allowed Christian communal capitalists “to make sacrifices in this life, because they consider them as seeds sown to fruit hereafter in the life to come.”Footnote 162

George and Frederick Rapp were no mere spiritual leaders of a group of utopian, Pietistic separatists, but industrial and manufacturing entrepreneurs. The members of Harmony were no mere gullible acolytes, but an efficient, skilled labor force. Together they made an incredible mark on the early United States’ expanding market economy. In 1814, the Baltimore Niles’ Weekly Register already described the Harmonists as “among the most persevering and industrious people in the world, and have all things in common. They now have mills and manufactories of many kinds.… They make broad cloths, cassimeres, flannels, paper hangings, whiskey, wine, flour, flaxseed-oil, leather, nails, iron-mongery, etc.!! and have a warehouse in Pittsburg [sic].…”Footnote 163 As founders of one of the earliest and most materially successful of the numerous nineteenth-century American communal capitalist utopias, they provided a model for others, such as the Shakers, Zoarites, Owenites, Mormons, and Hutterites. Across the Atlantic Ocean, Frederick Engels testified to the power of Harmony’s model, suggesting, “The success enjoyed by the Shakers, Harmonists, and Separatists … have caused many other people in America to undertake similar experiments in recent years.… However, it is not just in America, but in England too.”Footnote 164 Long after many utopian societies disbanded in failure, the economic success of Harmony allowed the Society to endure to the close of the nineteenth century.

Ultimately, the Harmony Society is a case study in how Lutheran Pietists attempted to purify the United States’ emerging capitalist order. Their Christian communal capitalism forsook wages and private property, yet regularly engaged in many of the other trappings of the market: stocks, bonds, leases, mortgages, patents, trademarks, licenses, litigation, and contracts.Footnote 165 Rapp & Associates boasted a skilled, hardworking workforce. Its market-savvy executives made astute business decisions and resisted the urge to overextend. Factories and machines increased industrial efficiency. The belief that Harmony was a divinely inspired construct imbued its members with a certainty, contentment, and sense of purpose that knit the community together and helped it weather internal and external crises.

At the same time, under the surface, the underlying tension of Harmony’s communal capitalism burbled. George Rapp’s power as spiritual and business leader was absolute. Harmonists who disagreed with him had to leave, often ripping apart families and tying up the litigants for years. Not all of Rapp’s decisions worked, either. Moving west was a risky business decision he was forced to repudiate by moving a second time and replanting near their original site. The Harmonists’ name for their third commune, “Economie,” reveals something of the way in which the Harmonists’ Pietism intertwined with their market activities, for Harmony was both a material and spiritual economy. Consequently, by the 1830s, Economie, Pennsylvania, was both the site of a quirky, wealthy religious commune and a wildly successful factory town.

Much work remains to more fully understand Lutheran Pietism’s contributions to the early American marketplace. Despite having influenced the other two streams of early American religion, Puritan Calvinism and Wesleyan Arminianism, Pietism continues to elude the attention of historians of American business.Footnote 166 The literature on Puritan Calvinism and the market is enormous and well established.Footnote 167 Likewise, Wesleyan Arminianism’s ascendency and eclipse of Calvinism in the early national period is increasingly well-trod territory.Footnote 168 In comparison, Lutheran Pietism often serves as a forgotten side tale, even though Franklin H. Littell argues that along with puritanism and utopian socialism, Pietism is one of the three most important sources of “intentional community” in American history.Footnote 169 Further investigation will not only better illuminate the economic lives of non-English-speaking American immigrants in the early national period, but also help us better understand the varied forms of nineteenth-century capitalism of the Atlantic world.