Introduction

Although Japanese design and cultural goods have enjoyed an excellent reputation throughout the world since the end of the twentieth century, fashion has not benefited from that general trend.Footnote 1 Except for Fast Retailing Co., the holding company of fast-fashion brand Uniqlo, the Japanese apparel industry presents a prominent lack of global competitiveness. According to the consultancy company Brand Finance, the 2017 global ranking of the top fifty most valuable fashion brands included only two from Japan (Uniqlo, in seventh, and Asics, in thirty-eighth).Footnote 2 Even in their domestic market, Japanese fashion brands are weak. Interbrand’s 2017 ranking of Japan’s top forty most valuable domestic brands lists only one from the fashion industry (ABC-Mart, in thirty-third).Footnote 3

Moreover, since the 1990s, the domestic Japanese market has seen Japanese apparel companies facing growing competition from foreign brands that have invested massively in developing a dense network of stores, both in the luxury segment (Chanel, Dior, Prada, etc.) and in fast fashion (mostly H&M and Zara).Footnote 4 Finally, one must stress the decline of the size of the Japanese apparel market (from 15.3 trillion yen in 1991 to 10.5 trillion yen in 2013), a result of the country’s aging population and a huge decrease in prices following deflation pressure and relocation of the production base to developing countries (import goods represented 36.1 percent of the domestic market in 1997 but 76.1 percent in 2013).Footnote 5 Under these conditions, Japanese apparel companies face a serious concern: they must move into the global market but lack brands that are strong enough for that expansion. Hence, companies that used to be highly competitive in the domestic market lose their competitiveness when they go abroad. This is an intriguing feature that requires analysis.

Most of the works in Japanese by economists and other social scientists argue that the difficulties confronting Japanese fashion companies result from a shrinking domestic market, weak brand management, and late engagement in online sales.Footnote 6 However, these explanations are rather descriptive; they note some facts that have led apparel companies to lose their competitiveness but do not explain why. Japanese researchers and companies do not differentiate between the apparel industry and the fashion industry, either. As we will detail in the next section, the first is an industry that produces clothes, whereas the second produces cultural value and image. This misunderstanding has led scholars to neglect the cultural side and overestimate the issues of production and technology.

As for international literature on Japanese fashion, largely works in sociology and cultural studies, researchers offer scant clues for properly understanding the dynamics of the apparel industry. Most of the scholarship is dominated by the paradigm of the uniqueness of Japanese fashion,Footnote 7 particularly an emphasis on the importance of street fashion. For example, Yuniya Kawamura maintains that “fashion is no longer controlled or guided by professionally trained designers but by the teens who have become the producers of fashion.”Footnote 8 During the 1980s and 1990s, some apparel companies and entrepreneurs, with the support of fashion magazines, took the opportunity to launch new brands and new styles that answered the demand for young customers.Footnote 9 Since the 1990s, Japanese street fashion has even become an export, particularly to South Korea and the United States.Footnote 10

A second feature of Japan would be what Kawamura calls “the structural weaknesses of fashion production.”Footnote 11 During the 1960s, Japan became an important market for Western fashion companies but only had the capability to produce domestic-oriented, culturally embedded fashion (street fashion). While the domestic apparel market was expanding, some Japanese orthodox designers moved to Europe, mainly to Paris, to pursue their careers; prominent examples include Kenzo Takada, Issey Miyake, Yoji Yamamoto, and Rei Kawakubo.Footnote 12 This has become the prevailing explanation of how Japanese fashion has developed and why Tokyo was unable to establish itself as a global fashion capital after World War II. For example, sociologist Frédéric Godart argues that Tokyo was an important market and exerted a broad influence on global fashion through street fashion—but that most of its designers made their careers in Paris: “This absorption of Japanese talents by Paris has strengthened the position of the French capital at the expense of Tokyo, but has not emptied the Japanese capital of its creative energy, particularly with regard to street fashion.”Footnote 13

There are, however, major shortcomings in this model. Fashion in Japan is far from being limited to street fashion. There are hundreds of independent designers, a broad fashion-media industry, a handful of trade associations, various retailers, and numerous apparel companies active in Japan, but Kawamura and her followers do not take those elements into consideration. The problem with these approaches, then, is that they focus only on a small and specific part of fashion in Japan, one that cannot contribute to an understanding of the decline and lack of global competitiveness of the country’s apparel industry. The ethnic approach toward Japanese clothing and fashion industry has led to misinterpretation.

A proper understanding of the declining Japanese apparel industry would benefit from insights in general works on competitiveness. The disappearing competitive advantage of Japanese manufacturing firms since the 1990s has attracted the attention of many scholars in management, international business, and business history. The management of technology approach provides a major model, arguing that a change in product architecture, characterized by the shift from the integral model to the module model,Footnote 14 together with the implementation of global value chains and the reorganization of production networks in East Asia,Footnote 15 explain this decline. Japanese manufacturing firms used to develop new products internally and were late to move to open innovation.Footnote 16 Another set of explanations focuses on the lack of marketing capability and the difficulties that Japanese manufacturers have had in properly understanding customer needs throughout the world.Footnote 17 Whereas these models contribute to an understanding of the decline of once globally competitive Japanese firms, they shed little light on the waning competitiveness of Japanese apparel companies.

The shift from a protected domestic market to the global market was the actual turning point in their decline, which means that attention should focus on this change. The industry study approach offers a valuable perspective for discussing the issues at hand.Footnote 18 It argues that a proper understanding of the evolution of the conditions of competitiveness should not be limited to an analysis on the firm level but should concentrate on the specificities of the given industry. From that standpoint, comprehending the conditions of competition on the domestic market—and examining why the shift toward the global market was so problematic—hinges on the defining characteristics of the Japanese apparel industry. This article argues that a major feature of the industry in question is the presence in Japan of a technology- and production-based fashion system, whereas the dominant model on the global market is a brand- and creation-based fashion system, as the following sections will detail. This difference results from the condition of the emergence of Western clothing in Japan after World War II. In his seminal work on the evolution of the post-World War II Japanese textile industry, Hiroyuki Itami demonstrated that the apparel companies in Japan emerged in close interaction with textile firms.Footnote 19 This distinct historical development has resulted in a fashion system not directly linked to creative activities, a pattern common in the French and European perspective. As section 2 will explain, the manufacture of Western clothes was a new industry. Its emergence did not result from technological and regulatory change, as it might in most new industries, but rather from a change in demand conditions and cultural values.Footnote 20

This article argues that a historical analysis and a business history–oriented approach are vital to a better understanding of the dynamics shaping the Japanese apparel industry. We focus here on the formative period of this industry: between 1945 and 1990. The main research questions we address are: Why do Japanese apparel companies not nurture strong brands? What are the causes of their lack of international competitiveness? How is fashion organized in Japan? To answer these questions, we apply the social science concept of the “fashion system” to the Japanese case.

The Fashion System

Since the 1960s, numerous scholars from a broad range of disciplines have considered fashion as a system, but very few have explored the question of what composes that system. In particular, many scholars in management, business history, and other social sciences use the term “fashion system” without defining it or even explaining how fashion can be understood as a system.Footnote 21 Therefore, it is usually not used as an analytical concept but as a mere synonym for “fashion business” or “fashion industry.”

One of the very rare scholars to have discussed the concept of “fashion system” is sociologist Yuniya Kawamura. She argued that “fashion is a system of institutions, organizations, groups, producers, events and practices, all of which contribute to the making of fashion, which is different from dress and clothing.”Footnote 22 Fashion is considered a cultural phenomenon supported by a system whose function is to legitimize creators and generate beliefs that hold fashion in regard. Business historian Regina Lee Blaszczyk used this idea of “fashion system” to emphasize the broad range of actors in the industry, particularly what she calls “intermediaries” between producers and consumers. However, neither Kawamura nor Blaszczyk explained the function of such a system from a perspective of business and profitability of firms.Footnote 23 Because fashion is a business, its organization as a system should also be discussed from this perspective.

Literature in management, political economy, and business history has broadly discussed the organization of business as a system, but not without contradictions and lack of clarity. Business has been considered a system at various levels. First, at the firm level, management scholars and consulting firms like McKinsey developed “business systems” (some of them also using the term “business models”) as tools for improving the management of companies. They comprise a set of actions and behaviors that managers should follow to conduct their company business successfully.Footnote 24 Second, in the context of research on varieties of capitalism, many scholars have argued that there were various national business systems around the world.Footnote 25 From this perspective, business systems consist of an ensemble of actors (firms, government, labor unions, etc.) and institutions (interfirm transactions, financial system, labor market, welfare, etc.) whose interactions differ between countries. Third, business systems can be observed at the level of industry and describe the nature of interfirm relations. For example, supply chains in the car industry,Footnote 26 commodity business by Japanese general trading companies,Footnote 27 or global value chains in the electronics industryFootnote 28 can be considered business systems. The main objective of such systems is to support the sustainability (stability and profitability) of enterprises that engage in them. Here, we use the business system approach from this third perspective. Fashion can indeed be considered a business system that includes a broad range of enterprises whose interactions ensure their sustainability.

Few scholars working on Western cases have conducted research on fashion as business systems that include designers, textile producers, retailers, and promoters. The organization science approach made it possible to emphasize the existence of slightly different models in France, Italy, and the United States.Footnote 29 The formation of the Italian fashion system has been a particular subject of study by business historians. Ivan Paris argued that the successful development of fashion in Italy during the 1960s relied not only on the presence of haute couture and creativity but especially on the interactions between companies engaged in textile, garment, leather goods, and accessories.Footnote 30 He thus maintains that the fashion system “combines vertical integration of sectors comparable in terms of production processes and horizontal integration of sectors that produce different kinds of goods.”Footnote 31 The most important role of this system is to reduce what he calls the “fashion risk,”Footnote 32 that is, a change in the tastes and needs of consumers. Cooperation between various actors within the Italian fashion system made it possible to offer a broad range of products and overcome this risk. As for Elisabetta Merlo, she has pursued this perspective with a study of cooperation between the largest textile company in Italia (Gruppo Finanziario Tessile) and fashion designer Biki to highlight that the proximity between two different kinds of enterprises supported the expansion of Italian fashion.Footnote 33

However, as we will demonstrate in this article, the function of fashion systems in the context of business systems is not simply to increase the flexibility of product development but also to ensure and increase the profitability of companies engaged in the system. The French fashion system is a case in point. During the first part of the twentieth century, most Paris-based haute couture companies suffered from low profitability due to their small size and narrow business model (high-quality handmade goods for a wealthy elite).Footnote 34 After World War II, and especially since the 1960s, haute couture companies started cooperating with other firms (perfume makers, retailers, confection companies, media companies, etc.) to build a sustainable model based on investing in brand making through haute couture creation and increasing profits through the sales of accessories and ready-to-wear items.Footnote 35 French semiologist Roland Barthes was one of the first to emphasize, during the 1960s, that media had a major influence on fashion and fashion consumption, although he did not discuss it from a perspective of business.Footnote 36 His work was later the basis for work by sociologist Yuniya Kawamura, who stressed the importance of institutions as intermediaries between producers and consumers in the fashion business.Footnote 37 Trade associations, the mass media, and events legitimize producers through various actions and consequently contribute to creating fashion as a cultural consumer good.Footnote 38

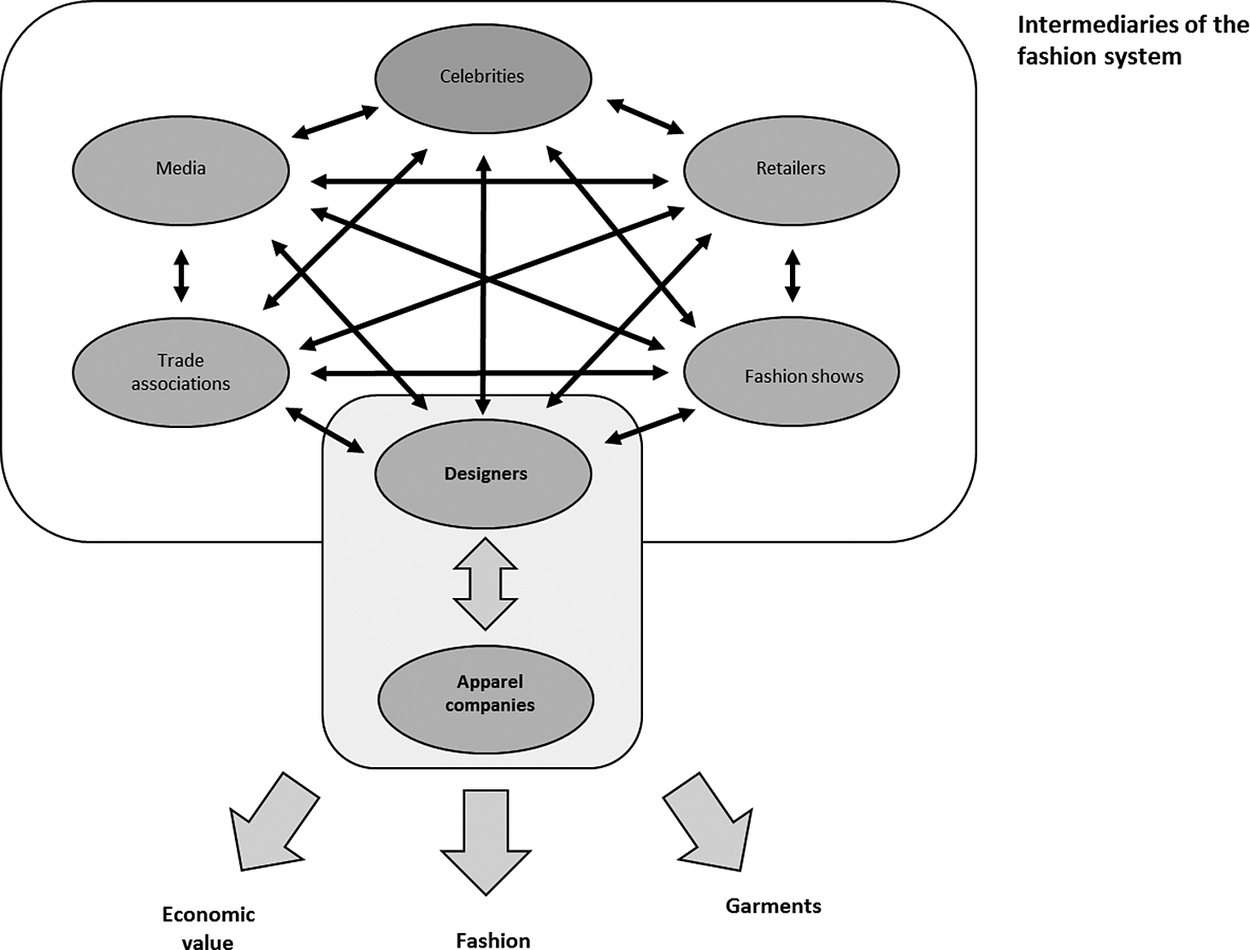

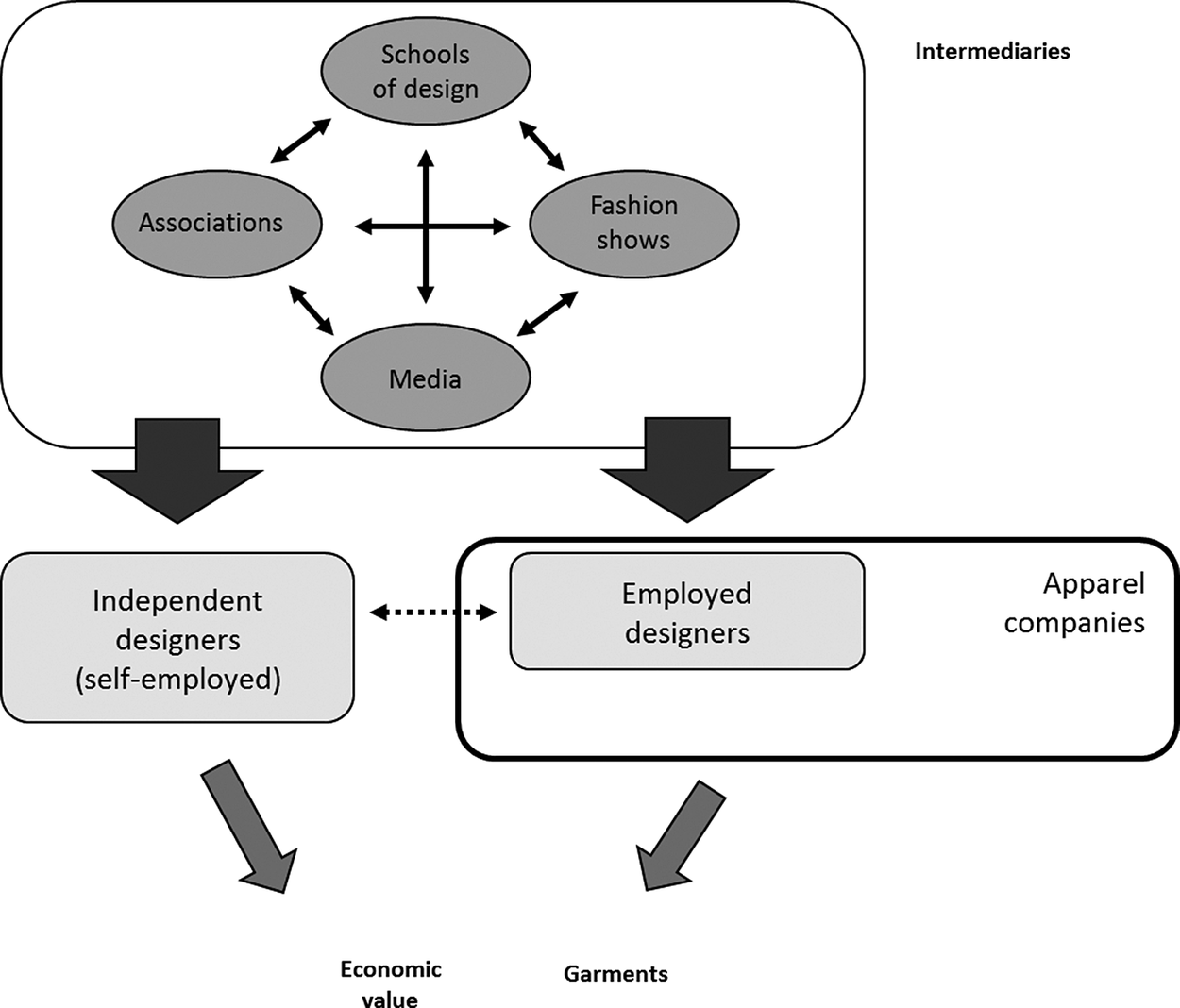

Figure 1 illustrates the fashion system in Western countries and its main elements (apparel manufacturers, designers, media, retailers, trade associations, fashion shows, and celebrities). The activities of these various actors, as well as their interactions, contribute to the production of fashion as a cultural value, the profitability of enterprises, and the sustainability of the overall business system. Apparel manufacturers make clothes but not fashion. They need the support of other actors that contribute to legitimize their designers, brands, and products as “fashion.”Footnote 39 For example, trade associations organize fairs and events during which apparel companies and designers meet and discuss topics like new color trends.Footnote 40 Retailers, be they department stores, shopping centers, or monobrand stores, offer a space to advertise products and have a deep impact on the construction of brand identity.Footnote 41 Fashion shows, usually organized by trade associations, are major events that give designers and apparel companies opportunities to communicate with consumers through fashion media.Footnote 42 Hence, a focus on the fashion system, rather than only on apparel manufacturers, is essential to a proper understanding of the industry in question.

Figure 1 Organization of the Western fashion system.

Source: Designed by the authors.

In the following sections, we analyze the emergence and development of this system in Japan between the end of World War II and the early 1990s. In particular, we focus on the interactions between the different elements of the Japanese fashion system and apparel companies in order to understand the specificity of how the interactions evolved. This article is comprised of three main sections. Section 2 discusses the development of the apparel industry itself after World War II, within the context of the westernization of consumption and the shift from Japanese to Western clothes. Section 3 focuses on the fashion system and its main actors. Section 4 goes back to apparel companies and analyzes their fashion strategies in relation to the findings from Section 3. Finally, the conclusion discusses the outcomes of this article and addresses research questions.

Making Western Clothes in Japan

The development of the Western clothing industry in Japan followed a path totally different from its counterparts in Europe and the United States. Western fashion saw a sudden, massive introduction into Japanese society and dramatically transformed traditional kimono fashion after World War II. In order to fully understand the formation of the Japanese fashion system, it is important to examine first the birth and growth of Western-style clothing companies in Japan alongside the development of department stores. This section covers how the Western clothing industry developed in Japan.

The Development of Clothing Companies

Historically, the Japanese apparel industry has been led by large spinning manufacturers that engaged as early as the last decades of the nineteenth century in the mastering of technology for mass production. This is one of the reasons for the emergence of an apparel industry based on production and technology.Footnote 43 The Japanese cotton-spinning industry was very competitive during the interwar period; Japan became the world’s largest cotton-fabric exporter by 1933, and exports of cotton products, mainly fabrics, were Japan’s largest export in 1934.Footnote 44 In the 1930s, an apparel industry, still essentially producing fabric for kimonos on the domestic market, took shape with three main types of businesses: large cotton-spinning manufacturers; small, highly interdependent companies that focused on a particular manufacturing process (e.g., dying, weaving, or finishing); and wholesalers, which linked the spinning manufacturers, small manufacturers, and retailers. Even after World War II, Japan’s quantities of textile exports once again became the world’s largest in 1951. However, the Japanese cotton-textile industry gradually declined during the period of high economic growth between 1954 and 1973, while the heavy and chemical industries, along with the electronics industry, developed considerably. The output levels and subsequently the volume of textile exports decreased after the trade conflict with the United States around 1970.Footnote 45

In contrast with large spinning manufacturers, weaving and clothing manufacturers were relatively small, as were wholesalers and retailers. For example, companies with fewer than five employees formed 45.7 percent of all clothing wholesalers in 1970 and 42.9 percent in 1976. Among retailers, that same rate was almost 80 percent in 1960 and about 75 percent in 1972.Footnote 46 Around 84 percent of all textile companies, meanwhile, had fewer than ten employees in 1965—and there was only one company with over one thousand employees; the textile sector then developed a strong tendency to include high proportions of small-scale companies: for instance, the percentage of textile companies with fewer than ten employees was 89 percent in 1970, 92 percent in 1975, and 93 percent in 1980.Footnote 47 Concentrated in clusters, these small-scale companies were flexible and able to respond to rapidly changing fashion trends, unlike spinning manufacturers.Footnote 48

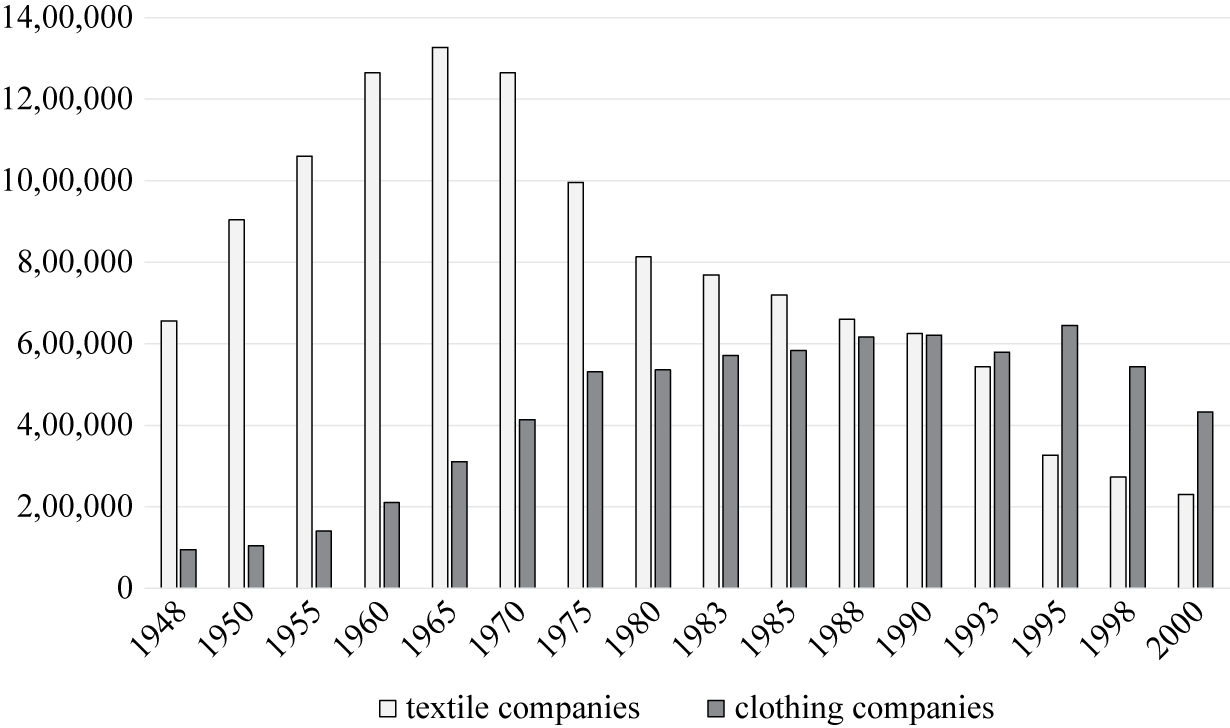

Yet the major feature of the Japanese textile industry during the decades following World War II was the growing importance of apparel makers and the decline of other manufacturers. Figure 2 perfectly captures the shift in balance between the textile industry and apparel industry. The number of employees of all textile companies, including those in silk reeling, spinning, twisting, weaving, knitting, dyeing, and printing, consistently declined in the second half of the twentieth century, dropping especially steeply from more than one million employees in 1965 and 1970 to 624,000 in 1990 and fewer than 230,000 in 2000. The number of employees per clothing company, on the other hand, increased consistently through the early 1990s, growing from 310,000 employees in 1965 to a peak of 644,000 in 1995. Total employment in clothing overcame employment in textiles in 1993.

Figure 2 Number of employees of all textile and clothing companies in Japan, 1948–2000.

Note: Data not available before 1948.

Source: Census of Manufacture (MITI).

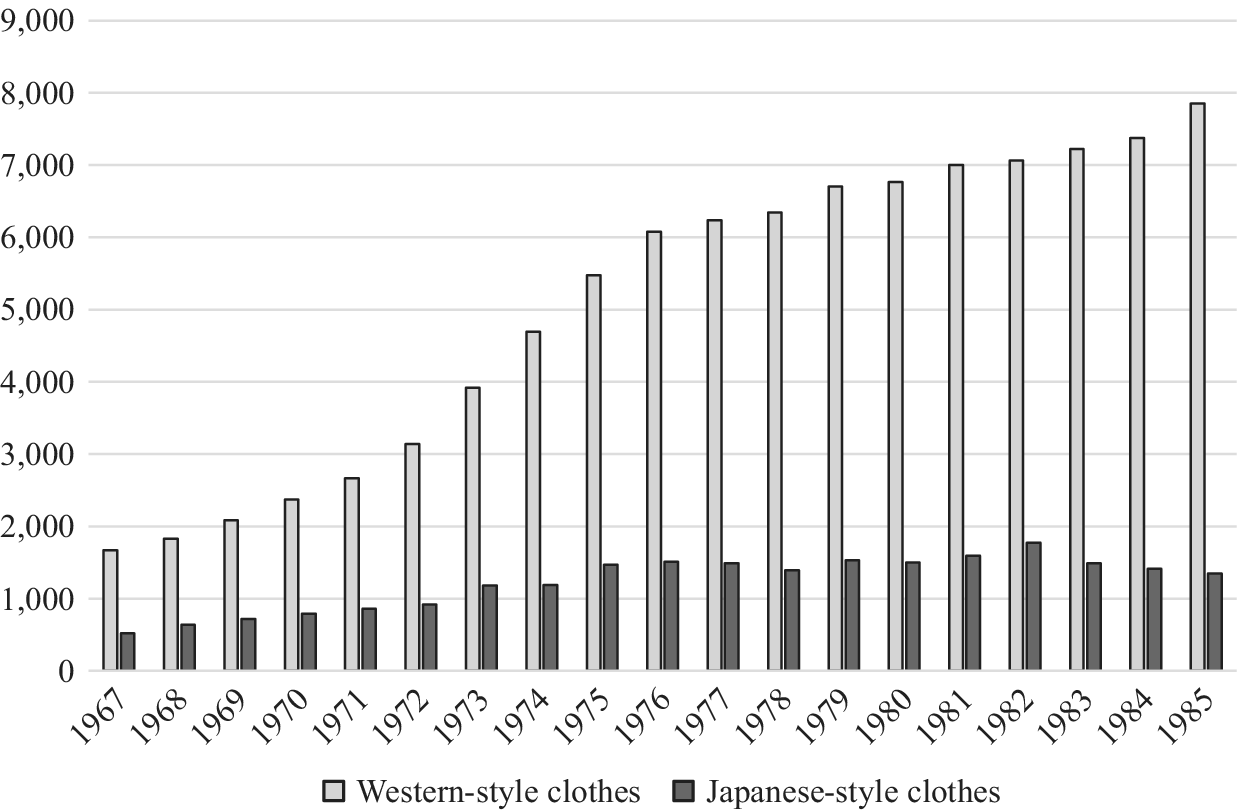

The growth of the apparel sector resulted from the fast-increasing popularity of Western fashion in Japan, along with the high economic growth and industrial development of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Figure 3 shows that Western-style clothes were the driving force for the consumption of garments in Japan from the second half of the 1960s to the mid-1980s. In 1967, they already represented 76.3 percent of workers’ expenses for clothes, which means that Japanese-style items had become a minority part of the larger fashion arena. The share of Western-style clothes expanded gradually during the following years, reaching 81.8 percent in 1980 and 85.4 percent in 1985. Between 1967 and 1985, spending on Western-style clothes multiplied by 4.7—as opposed to 2.6 times for Japanese-style clothes.

Figure 3 Annual averages of monthly workers’ household expenses on clothes.

Note: Data unavailable before 1967.

Source: Household Expenditure Survey.

Western garments were first introduced in the form of tailor-made clothes for the upper and upper-middle classes, whereas mass-market consumers began making their own Western-style clothes at home, shifting gradually to acquisition on the market. This new demand represented a huge business opportunity for numerous entrepreneurs. Consequently, the number of apparel companies and wholesalers increased dramatically. For example, in 1966, there were 5,858 women’s clothing manufacturers; that number increased to 10,254 in 1972 and 14,204 in 1976—more than doubling (2.5 times) over ten years. Women’s clothing wholesalers exhibited a similar trend. From 1966 to 1976, the number of women’s clothing wholesalers rose 1.9 times—from 2,593 to 5,044.Footnote 49

Not all these firms were small businesses, however. The largest company among the newcomers, Renown, was established in Osaka by Yasohachi Sasaki, a wholesaler who had dealt in imported products such as perfume, blankets, and ties since 1902. He then started to manufacture knitwear products in 1926 and sold them to department stores. During World War II, Renown sewed military clothes, experimenting with methods of mass production. After the war, it sold knitted vests and jumpers and expanded to ready-to-wear jackets and suits from 1957 onward. It experienced rapid growth in the 1970s, a decade during which Renown actively launched items in the menswear category, using the French actor Alain Delon as a model in advertising.Footnote 50

A second firm, Kashiyama, originated in 1927 in Osaka. The founder was Junzo Kashiyama, who was then a clerk at Mitsukoshi department store. Kashiyama also focused on wholesale. He imported perfume and sporting goods and produced sportswear before World War II, later launching his own ready-to-wear brands for menswear during the postwar recovery years. The company got American clothing from GIs (U.S. soldiers) and used reverse engineering to learn how to sew Western clothes. Kashiyama then sold its goods at department stores in the 1960s.Footnote 51

Another company, Sanyo Shokai, was established by Nobuyuki Yoshihara in 1942 in Tokyo as a manufacturing and wholesaling company for textiles and other industrial goods. In 1945, its business transformed into the wholesale production of raincoats for department stores. Through radio advertisements and a marketing strategy that tied up with films, Sanyo Shokai expanded its merchandise lineup to include coats and suits. The firm obtained a license to manufacture Burberry coats in Japan and started selling them in 1965 and, a few years later, it expanded their licensed products to not only Burberry goods but also other well-known brands’ products.Footnote 52

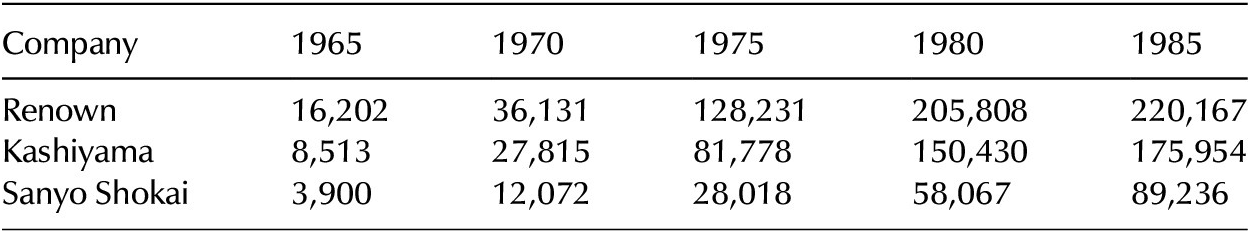

These three companies found their market for clothing through department stores, which had all the latest fashions at the time—a partnership that helped the companies increase their sales. For example, sales to department stores accounted for 70 percent of Renown’s total sales in 1955.Footnote 53 Fast-growing demand among department store customers fueled further increases, with ready-to-wear garments becoming common among every generation and income group during the 1970s. As shown in table 1, Renown’s sales in 1970 amounted to 36,131 million yen and increased to 205,808 million yen in 1980 (5.7 times over ten years); Kashiyama’s sales in 1970 totaled 27,815 million yen and increased to 150,430 million yen in 1980 (5.4 times); and Sanyo Shokai’s sales in 1970 came to 12,072 million yen, increasing to 58,067 million yen in 1980 (4.8 times). These new companies tapped the new market for ready-to-wear offerings along with department stores in Japan.

Table 1 Sales of the largest clothing companies, in millions of yen, 1965–1985

Source: Annual Securities Report, Renown, 1965, 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985; Annual Securities Report, Kashiyama, 1965, 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985; Annual Securities Report, Sanyo Shokai, 1965, 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985.

The Major Role of Department Stores

Department stores played a major role historically in the introduction of foreign luxury goods in Japan. Since the interwar years, they embodied modernity in new urban societies and offered a new form of material civilization to Japanese upper middle classes. In the 1950s and 1960s, they became important partners of French couturiers in bringing fashion to the Japanese market.Footnote 54 However, department stores were not only leading fashion retailers with a stronger focus on the higher-end market than other retailers but also big sales outlets for apparel manufacturers and wholesalers. In 1977, for example, they sold 29.4 percent of all the women’s clothing in Japan and 32.8 percent of children’s clothing; specialty stores accounted for 45.8 percent and 24.0 percent, respectively.Footnote 55 Department stores played a key role in the development of the apparel industry, particularly in three directions.

First, they transferred technology and skills related to the manufacturing of Western-style clothing to Japan. Japanese department stores also learned new methods for merchandising and producing ready-to-wear clothing from Western department stores in the 1950s. Representatives from Isetan, for example, visited Western department stores in 1951 and brought modern merchandise methods in the United States, along with the buyers’ manual of the National Retail Merchants Association, into Japanese stores.Footnote 56 Managers of other companies also visited Western department stores to understand their merchandise and copy their product displays. Back in Japan, they cooperated with apparel makers and launched new ready-to-wear clothing in the late 1950s.

Second, Japanese department stores, as the leading retailers at the time, contributed to the standardization of ready-to-wear clothing. At first, there was some confusion over different standards of small, medium, and large sizes of clothing among manufacturers and retailers, as they each adopted their own standards.Footnote 57 To avoid confusing customers, Isetan and two other department stores unified their standards based on data regarding their customers’ body sizes. These standards then spread to all other department stores and manufacturers as fixed Japanese clothing sizes.

Third, they stimulated customer demand for Western-style clothing with their marketing strategies and expanded the market. Mitsukoshi started holding Western-style fashion shows in 1950, and Takashimaya held a catwalk fashion show with its licensed Pierre Cardin prêt-à-porter products in 1960.Footnote 58 Because department stores attracted wealthy and fashion-conscious customers, they were the perfect places to introduce the latest Western fashion, including luxury fashion in the 1980s.Footnote 59 As a result of these initiatives, ready-to-wear clothing became suitable for mass production and mass sales, and its market expanded.

Once the sales of ready-to-wear items increased and led to the mass production of Western garments, department stores reorganized the classifications of their sales areas from product categories to brand concepts. At the time, stores divided their sales areas according to product category, with separate sections for skirts, shirts, trousers, and so on; each category contained a mix of products from several different manufacturers. Then, clothing manufacturers presented their own concepts for different kinds of clothing. For example, a particular shirt and pair of trousers were coordinated in line with the new concept of “urban casual.” Manufacturers thus adopted a certain image for presenting their products and were keen to foster customers who were loyal to their brand.Footnote 60

Moreover, partnerships between department stores and apparel companies led to the introduction of new types of store operations. Clothing manufacturers requested two major changes. First, they introduced new transaction systems, such as consignment sales and concession sales. Kashiyama first introduced this new strategy in 1953. With consignment sales, department stores accepted more stock from clothing manufacturers, but they did so on a sale or return basis—a setup that greatly reduced the associated risk. With concession sales, meanwhile, department stores offered portions of their sales floor to wholesalers and manufacturers and charged commissions according to their corresponding sales. As offers from clothing companies came in, department stores easily and rapidly expanded their merchandise and business without taking on the risk that came along with purchasing large quantities of stock. Clothing companies, too, rapidly increased their sales at the department stores.Footnote 61

Second, clothing manufacturers provided their own shop floor sales staff, on their own budget, for every department store branch. This alleviated the risk for department stores in terms of increased labor costs, which were necessary for managing the increased stock. Although apparel companies had to deal with the higher initial costs, they were then able to control their points of sale, get direct feedback from their customers, and collect valuable customer data that helped them to adapt their production operations.Footnote 62 The arrangement consequently worked out very well for them, as it did for department stores. This was a successful relationship between department stores and clothing manufacturers that developed along with the growing ready-to-wear clothing market between the 1950s and 1970s.

With the introduction of consignment and concession transactions, clothing companies built numerous product brands for different market segmentations and expanded their sales areas within department stores in the 1970s.Footnote 63 If a given clothing company had stuck with a single product brand, it would not have been able to expand its sales space at department store locations. However, by introducing a diverse mix of brands at a single store, it took much longer for a specific brand to reach a saturation point; this also meant that the company could construct a portfolio strategy. Renown, for example, provided its products through a single brand—“Renown”—in the 1960s but launched new brands one after another in the 1970s (e.g., Arnold Parmer, Koret, Adenda, and Simple Life), with consignment agreements for their own sales areas.Footnote 64 The apparel company World, founded in 1959, had only four total brands in the 1960s; it then proceeded to launch twenty new brands in the 1970s and sixty-nine others during the 1980s.Footnote 65 With that kind of variety, customers grew fond of particular brand names rather than company names, and department stores were easily able to expand brand lines and increase their own sales. Sales for clothing manufacturers therefore increased further as a result of their multibrand strategy for department stores.

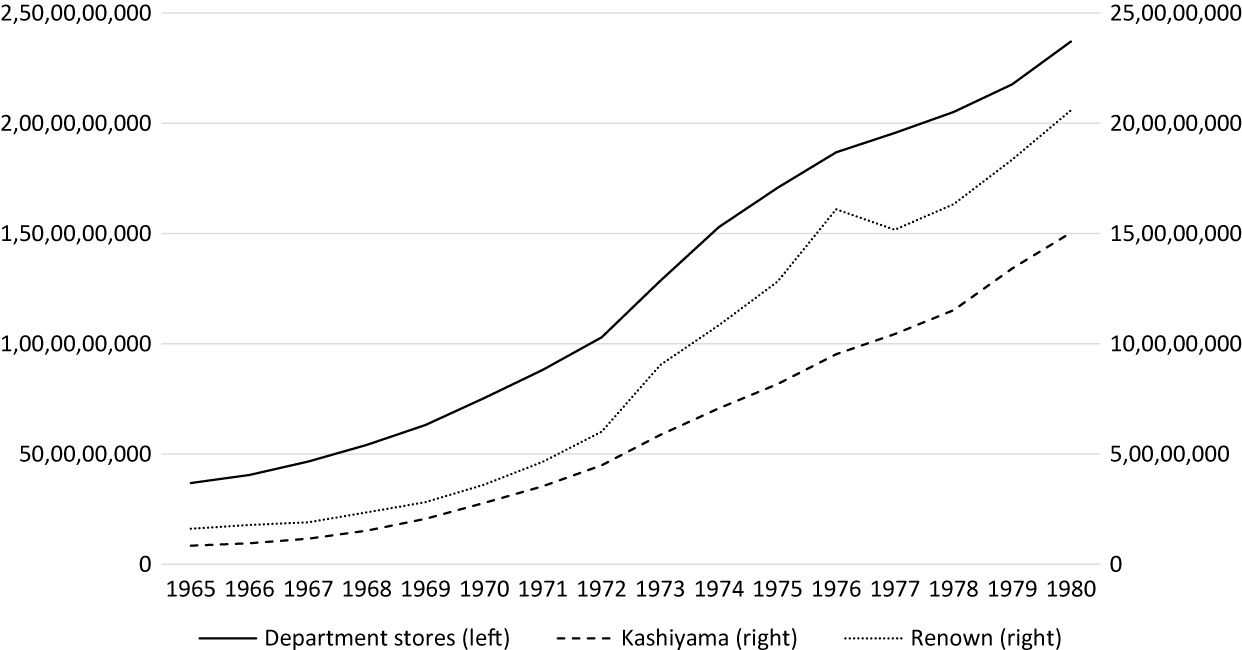

Consequently, the emergence and development of a Western clothing industry in Japan had roots in a particular relationship between apparel companies and department stores. Figure 4 shows that the total apparel sales by all department stores in Japan followed a similar growth trend to that of the gross sales at leading apparel companies Kashiyama and Renown. These two actors contributed significantly to the creation of fashion as a cultural good in Japan. They were not alone, however. The next section will discuss the position of other actors, particularly designers and fashion media, and their connections with apparel companies and department stores.

Figure 4 Total apparel sales of Japanese department stores and gross sales of Kashiyama and Renown, thousands of yen, 1965–1980.

Source: JDSA, Annual report of Japan Department Stores Association, 1981 and Annual Securities Report, Kashimaya and Renown, each year.

Emergence of New Intermediaries

While apparel companies and department stores cooperated to produce Western clothing, a broad range of new actors emerged and played a major role in the construction of a fashion system in Japan. Designers, media, and various trade associations developed interconnected actions and thereby contributed to the production of Japanese fashion.

Fashion Schools

In the 1970s, Japanese designers began enjoying worldwide renown for their creativity and talent. Kawamura demonstrated that these designers, most of them trained in Tokyo, became famous outside of their home country by participating in fashion shows in Paris and New York, some earning acceptance as “haute couture” in Paris (e.g., Kenzo Takada).Footnote 66 The fame that they gained abroad enabled them to establish themselves as respected fashion designers in Paris. Whereas scholars have detailed that process of career-making in previous studies, one must still discuss the impact of designers in the formation of a fashion system in Japan.

Designer schools played a major role as organizations that implemented and coordinated actions to connect designers with other actors in the fashion system. The Bunka Fashion College (Bunka Fukuso Gakuin, BFC), reopened in Tokyo in 1946, was the leading establishment for the diffusion of clothing knowledge and the training of designers. The institution’s roots go back to a small, in-store workshop at a clothing store. The workshop began training young women to make Western garments using sewing machines in 1919. It had close ties to the manufacturer Singer and established itself as a first mover in creating Western fashion in Japan during the interwar years, launching the country’s first fashion magazine—Soen—in 1936. Its objective was to promote the use and self-manufacture of Western clothing among the masses.Footnote 67 After World War II, the reopened BFC grew quickly as the Westernization of fashion took off. Many young women and housewives entered schools like BFC, aiming to learn how to produce clothes. In 1960, 75.5 percent of all households in Japan already had sewing machines.Footnote 68 However, people needed practical knowledge about how to use them properly; schools provided that vital instruction.

At the same time, BFC extended its activities from clothing to fashion. Since the early 1950s, for example, it organized fashion shows in Tokyo and other major cities like Nagoya, Osaka, and Kyoto. The college also engaged actively in fashion media. It relaunched Soen in 1946 and founded many of the first new fashion magazines in postwar Japan for a more segmented market, particularly High Fashion for wealthy people (1960) and Mrs. for young housewives (1961). Furthermore, BFC invited famous Western designers—like Christian Dior (1953), Howard Greer (1954), and Pierre Cardin (1958)— to give lectures and organize fashion shows. Another way the institution encouraged fashion in Japan was via the creation of several prizes for commendable design, including the Soen Prize (1957) and the Cardin High Fashion Prize, which occurred when Pierre Cardin was appointed emeritus professor of the school (1961). Finally, one must mention the setup of a division to train fashion models in 1953.

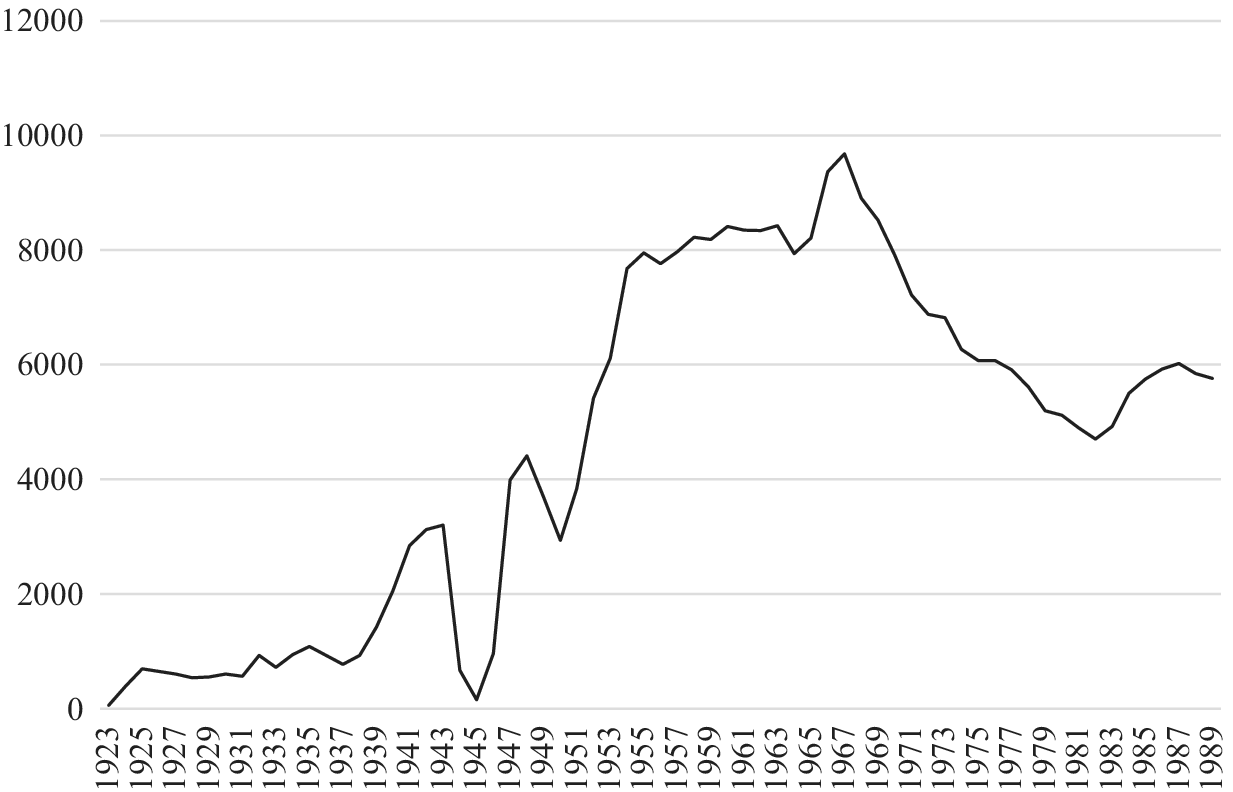

Consequently, the activities of BFC went far beyond the mere training of housewives and designers. It contributed greatly to the promotion of fashion and the construction of a fashion system in Japan during its formative years. BFC was not only involved in producing designers but also in broadening new styles of Western fashion, a process in which its students were instrumental. Figure 5 shows a rapid increase in the number of BFC students during the 1950s. BFC trained thousands of young girls (and boys from 1957 onward) in the various aspects of fashion. The number of students grew along with the demand for Western clothing. Once ready-to-wear fashion became popular, however, the number of students at BFC decreased in the 1970s, and the school refocused on designers.

Figure 5 Number of students at Bunka Fashion College, 1923–1989.

Source: Bunka fukuso gakuin kyoiku shi, Tokyo: Bunka fukuso gakuin, 1989, p. 22.

Among other schools, Dressmaker Gakuin followed a model similar to BFC. Founded in Tokyo in 1926 by Yoshiko Sugino, a fashion stylist and businesswoman, it introduced the idea of ready-made clothes for women, based on standardized sizes, during the interwar years.Footnote 69 Sugino and her students sewed and remade clothes for GIs during the postwar years, providing the learners with good opportunities to study Western clothing patterns, materials such as buttons and textiles, and stylebooks, as well as to foster continued growth into the future. The school reopened in 1946 and expanded into about seven hundred affiliated schools to teach sewing skills and provide instruction on dress patterns.Footnote 70 Later, Sugino also founded a publishing company, Kamakura Shobo, which launched fashion magazines like Dressmaking (1949) and Madam (1967), offering dress patterns that housewives could use for home sewing. In this way, Dressmaker Gakuin contributed to the spread of Western-clothing sewing in Japan, but it focused on tailor-made clothing in the higher-end market rather than ready-to-wear items, which became popular in the 1960s.Footnote 71 Another institution meriting mention is Kuwasawa Design School (Kuwasawa dezain kenkyujo), which fashion and design journalist Yoko Kuwasawa opened in Tokyo in 1954.Footnote 72 The size of its organization and scope of its engagement in the fashion system were far below those of BFC and Dressmaker Gakuin, however.

Moreover, the actions of designers in promoting a fashion system went beyond the school channel. Designers themselves set up organizations to advertise their work collectively. Several groups were founded in Tokyo. The first was the Nippon Designers Club (NDC), organized in 1948 by Shiro Kimura, the boss at Stock Shokai, a Western fashion shop in Ginza.Footnote 73 NDC gathered independent designers, artists, and people from schools. It organized fashion shows, the first one in 1949 in Tokyo, and the first professional fashion show in 1951.Footnote 74 However, people from apparel companies and businesses organized a competing group, the Japanese Designers Association (Nihon dezaina bunka kyokai, NDK), in 1954.Footnote 75 Design was considered a resource for the clothing industry, not an artistic activity. Therefore, the apparel industry wanted to exert control over designers. The first council of NDK was presided over by Bunzaburo Banno, a businessman active in trade with France.

However, independent designers, led by a few who had experienced success abroad (mostly in France), organized new groups to promote their creations through fashion shows. These groups were loosely structured and changed over time. One of the first was the Tokyo Collection Group (1964).Footnote 76 Ten years later, six designers in the ready-to-wear business formed the TD6 (Top Designer 6) group to present their collections in a joint arrangement twice a year.Footnote 77 This event became Tokyo Fashion Week, whose first edition came in 1975. The success of the event attracted new designers and led to the founding of the Tokyo Collection Office (1981) and the Council of Fashion Designers (1985), which oversee Tokyo Fashion Week. The participation of star designers like Issey Miyake, Kansai Yamamoto, and Hiroko Koshino transformed this biannual show into a major event for the fashion business. These designers also sold their products to department stores, which is where fashion-conscious customers bought the latest clothing.

Fashion Media

Next, the fashion media industry established itself as a major actor in the Japanese fashion system.Footnote 78 As we noted above, there were already a few magazines that existed during the interwar years and relaunched after the war. These magazines focused on the promotion of Western clothing toward housewives. During the 1950s, a new generation of media appeared with a new objective: contributing to the creation of fashion as a cultural value. About ten new magazines appeared in the years leading up to 1975. Designer schools, again, were among the first organizations to publish such magazines.

Publishing companies also engaged in this growing market after the war, Fujingaho being the largest of them. The firm, whose roots go back to the early twentieth century, launched Men’s Club (1955). Other general publishers include Magazine House, with An-an (1970) and Popeye (1976), and Shueisha, with Seventeen (1968) and Non-no (1971). Finally, in an exceptional case, the famous designer Hanae Mori launched her own magazine in 1975: Ryuko Tsushin. Footnote 79

The actions of fashion media transcended publishing, too. In 1952, four businessmen from the media industry, namely Isao Imaida (editor of magazines published by BFC), Tatsuo Maido (director of Fujingaho), Tadanobu Seto (from Nihon Orimono Shuppansha, founder of Vogue Japan in 1954), and Eitaro Hasegawa (founding director of Kamakura Shobo), gathered and organized the Fashion Editors Club of Japan (FECJ).Footnote 80 The organization, which still exists today, has promoted fashion since 1956 by giving awards to people responsible for contributions to the development of design in Japan.Footnote 81 FECJ introduced a foreign prize in 1994 and gave a special award to Uniqlo in 2001. It represents a classic example of how the fashion media industry legitimizes designers and creators.

After the 1970s, the rapid development of the fashion business in Japan attracted a growing number of publishers in the fashion-magazine market, with a strong trend toward segmentation. More than forty new titles hit bookshelves during the 1980s, and again more than fifty during the 1990s.Footnote 82 The sheer number of titles evinced a highly segmented market with hundreds of brand launches by apparel companies. Besides mass production and the diffusion of images and values linked to fashion, this period also saw general newspapers engage in fashion. They started organizing their own fashion shows and awards in the 1980s, for instance.Footnote 83 Asahi Shimbun was one of the first, holding a show in honor of Issey Miyake and Kenzo for its 110th anniversary in 1989. It also organized The Givenchy Show (1983), whereas Yomiuri Shimbun launched the Tokyo Pret-a-Porter Collection (1985) and Fuji Sankei Group the Dream Factory (1987). The Mainichi Shimbun, meanwhile, created the Mainichi Fashion Prize in 1983.Footnote 84 All were important steps toward fashion for the masses.

Trade Associations

Finally, a broad range of trade associations were founded in the textile industry after World War II and officially supported by the government.Footnote 85 Most did not engage in any activities beyond production and technological issues. Some of them, however, contributed to the emergence of a fashion system in postwar Japan. For example, the Japan Fashion Color Association (Nihon Ryukoshoku Kyokai, JAFCA), founded in 1953, joined its counterparts in France and Switzerland in forming the International Commission for Color (Intercolor) in 1963. The organization’s various events and meetings had a major impact on fashion forecasting through connections among designers, apparel and textile producers, and retailers.Footnote 86

Other examples include the opening of a Japanese branch in Tokyo by the International Wool Secretariat, an organization founded in 1937 by woolgrowers in the British Empire, in 1953Footnote 87 and the creation of the Nippon Uniform Center (NUC) in 1962.Footnote 88 The latter underlined the role of these sorts of associations in connecting actors in the fashion system. The NUC’s objective is to enable cooperation among different kinds of actors to develop uniforms for schools, companies, and other organizations. The chair of the first committee was Wajiro Kon (an anthropologist and architect, as well as a specialist in clothing design), and members included Makoto Urabe (a fashion critic in media and the director of the first Nobuo Nakamura show in Paris), Nobuo Nakamura (a designer), Yasuo Inamura (a professor of chemistry at the Tokyo Institute of Technology and a specialist in colors), Yoshisuke Kasai (the vice president of the Japanese Red Cross Society), Chie Koike (a designer), Kunio Hayashi (an independent fashion critic), Mitsuko Morooka (a designer) and Ayako Totsuka (an employee of JTB, which promotes tourism in Japan).

In addition, the Japan Apparel Industry Council, which was formally established in 1982 (despite launching their activities in 1979), was founded by large apparel companies such as Renown, Sanyo Shokai, and Kashiyama. It merged with the Tokyo Women’s Children’s Clothing Industry Association, Tokyo Men’s Apparel Industry Association, and Harajuku Apparel Conference and reorganized itself as the “Japan Apparel Fashion Industry Council” in 2001. This association has played a significant role in developing the apparel industry in Japan in terms of enhancing the technology level in the 1980s and 1990s and the lobbying activity since 1990s.Footnote 89

There were also associations without structural links to the textile industry but that still supported the development of fashion business. That was the case for model agencies, in particular, which provided young models for fashion shows and magazines. Shiro Kimura, founder of NDC, founded one of the first agencies—the Tokyo Fashion Model Club (TFMC)—in 1952.Footnote 90 The following year, Kinuko Ito, a twenty-one-year-old model and Japan’s representative at the Miss Universe contest that year, founded the Fashion Model Group along with several colleagues.Footnote 91

The Creation of New Fashion Outlets

Cooperating with department stores to produce Western clothing was not enough for the apparel industry to strengthen its position in the fashion system. Some designers and apparel companies tapped new sales channels: large shopping complexes in urban areas and train terminals where there was a concentration of different specialty fashion boutiques and no anchor tenants.

The first one was established in 1969 by Parco, a company belonging to the department store Seibu, at Ikebukuro station in Tokyo. Parco housed 170 up-and-coming specialty fashion boutiques and advertised itself to young consumers as the best place to shop for the newest fashion trends, rather than promoting certain individual shops onsite. The tenants of these boutiques were designers or companies that used them in the short term, depending on the success of their goods. This was a new business model for selling garments, as department stores and shopping malls usually have fixed tenants for their shops.Footnote 92 Following Ikebukuro Parco’s success, Shibuya Parco was launched in 1973. Next, in 1976, the East Japan Railway Company opened the Lumine fashion center in the Shinjuku Station building. The urban developer Mori Building founded Harajuku La Foret in 1978, and Tokyu Railway created the new Shibuya 109 building in 1979. These new shopping complexes made the areas of Shibuya and Harajuku the most fashionable shopping districts of Tokyo and Japan as a whole. They attracted fashion-conscious consumers from across the country—as well as Western scholars in fashion studies.

Within these buildings, young designers were able to develop their businesses by launching their own shops. They followed a very flexible production system with only a few core pieces. For example, the designers at La Foret included Takeo Kikuchi and Yoshie Inaba for Bigi and Comme Ça Du Mode, Mitsuhiro Matsuda for Nicole, and Yukiko Hanai, Junko Koshino, and Isamu Kaneko for Pink House. By giving these young designers a space in its building, La Foret benefited from their energy and enthusiasm for crafting new fashion. As these designers did not have the funds to establish their own shops individually, the setting of a fashion complex was an ideal platform for producing and showcasing their work.

The new fashion media also supported their growth. For example, An-an and Non-no, two leading fashion magazines in the 1970s, filled their pages with a bounty of images, combining different brands of tops, skirts, and trousers to create new and unique styles. These magazines echoed the sentiments of young designers who were proud to be different from the mainstream clothing industry, bringing their fresh perspectives to the market as designer brands. In these young designers’ shops, instead of using mannequins, sales assistants themselves wore the clothes they sold—a new type of marketing strategy at the time. In this way, fashion brands catering to consumers with distinctive fashion tastes developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s.Footnote 93

These fashion complexes also impacted Tokyo’s street fashion. Young people shopping in these new urban outlets influenced fashion boutiques through their purchases and tastes, rather than the opposite. In the 1960s and 1970s, street fashion in Tokyo was heavily influenced by American West Coast fashion, including jeans and suit-style outfits inspired by the fashions of Ivy League students.Footnote 94 However, in the 1990s, the new street fashion mostly came from teenagers, especially high school girls. Although they had to wear school uniforms, which were essentially all the same, they created their own fashion statements by doing things like wearing long, white, baggy knee socks that they pushed down their shins like leg warmers. Young students were the driving forces behind the movements of “costume play (cosplay),” in which people wear the outfits of their favorite animation characters, and “Gothic Lolita,” a style featuring Victorian dresses with pale skin and neat hair.Footnote 95

Fashion shopping complexes mainly focused on progressive customers, and the boutiques’ designers tended to be avant-garde. These designers moved their sales areas from shopping complexes into department stores to gain more customers, however, once the designers were able to stand on their own feet. In 1977, a total of 32 percent of the sales of all women’s outfits in Japan were made through department stores, which were the largest outlets in the market, although supermarkets had the largest sales of skirts.Footnote 96

Although department stores were the dominant outlet in clothing sales, one must note that the successes of fashion shopping complexes, especially those in Tokyo, attracted many newcomers. Some companies focused on the import of fashion goods from different brands from all over the world instead of hiring their own designers. For example, Beams established its first “select shop” in 1976.Footnote 97 Ships followed suit in 1977, as did United Arrows, which opened its first store in Shibuya in 1990.Footnote 98 These stores had less merchandise than established department stores, but their selections of products reflected their respective stores’ unique concept, taste, and positioning. The success of this strategy enabled these retailers to grow rapidly throughout the 1990s and beyond. Consequently, Japanese clothing outlets have diversified considerably since the 1970s.

The Fashion Strategy of Apparel Companies

Finally, one must also discuss the fashion strategies of apparel companies. Their cooperation with department stores enabled them to produce Western clothing—but their scope of action extended beyond the manufacture of clothes. They also contributed toward “producing” fashion. Although the companies have exhibited different individual fashion strategies and specificities, two main common features are evident.

First, most apparel companies internalized the design function. When major apparel companies such as Renown, Kashiyama, and Sanyo Shokai shifted from clothing wholesaling to apparel manufacturing, they trained their own designers by themselves to align with their new factory equipment. The design was one of the process flows for these companies, and designers were in charge of the process. They thus designed clothing just as designers at the automobile manufacturers and home electric companies did.Footnote 99 Cooperation with star designers who gained fame in Europe and the United States was very weak; most of the designers in that category established freelance careers upon returning to Tokyo and opened their own small companies, which was the case for designers who opened their first outlets at shopping complexes, as noted above.Footnote 100 One exception is the collaboration between the giant apparel company World and the designer Takeo Kikuchi. World began marketing Takeo Kikuchi–designed men’s clothes in 1984 and has since opened Takeo Kikuchi stores throughout Japan.Footnote 101 For most Japanese apparel companies, though, design is a business—not a creative activity. This approach led many young talented designers to leave apparel companies and pursue their careers independently. Examples include Nobuyuki Inoue, who left the lingerie maker Wacoal, Yutaka Hasegawa, a former employee of Itokin, and Kyoko Higa, who started her career at World. All of them went freelance after a few years at large apparel companies.Footnote 102

Second, apparel companies are characterized by a management approach dominated by a technological paradigm.Footnote 103 As design is not considered as a creative activity, the development of clothes follows a rationalized, science-based procedure. Product-development divisions at apparel companies are thus usually headed by engineers. The case of the Fashion Technology Group (FTG), founded in 1976 by two engineers from major producers of artificial fibers (Asahi Kasei and Teijin) and one engineer from the Osaka-based apparel wholesale company Chori, illustrates this paradigm. These three men organized the FTG in order to scientifically measure the future of fashion. They believed that mathematically processing a broad range of data on clothes (e.g., size, color, shape) and demographics (e.g., gender, age, income) would make it possible to design the right products. In 1980, the FTG included twelve members, mostly from companies in the upstream part of the clothing industry (five from artificial-fiber companies, two from weavers, and one from a dyer); there were only two members from apparel makers and two from fashion intermediaries (one fashion coordinator and one from the fashion media industry).Footnote 104

Consequently, for Japanese apparel companies, “fashion” is related to production and technology. The design of clothes is not a creative process but rather a purely material activity. This focus on technology is related to their highly segmented brand strategies. Meticulous market surveys make it possible to establish and distinguish customer needs with exacting precision and meet those demands with specific products and brands. In that sense, “fashion” is not a cultural value but a mere material good, synonymous with a “garment.” Several trade associations in the apparel industry call themselves “fashion associations” despite representing clothing manufacturers and distributors, like the Japan Fashion Apparel Industry Council.

Figure 6 illustrates the specificity of the Japanese fashion system, as compared with the Western fashion system introduced at the beginning of this article, and summarizes some of our findings. The role of the intermediaries in the fashion system (schools of design, associations, media, and fashion shows) is not to legitimize designers, brands, and enterprises in order to create fashion as a cultural value; rather, the intermediaries serve to support the transmission of technical knowledge concerning clothing. Hence, apparel companies and independent designers produce “clothes” rather than “fashion” in the Western sense.

Figure 6 The Japanese fashion system.

Source: Drafted by the authors

As section 2 explained, the modern fashion system took root in Western Europe after World War II to enable the sustainability and increase the profitability of apparel companies. The cooperation between apparel companies and department stores aimed at facilitating profit growth for both partners and building efficient supply chains, not at creating fashion. In this sense, “fashion” is not only related to the idea of a permanent change of style but also to the birth of strong brands that emerge from the system. However, despite having a long tradition of fashion consciousness since the Edo period, Japanese consumers have mostly given attention to the material characteristics of clothes (color, form, and fabric).Footnote 105 This feature persisted throughout the interwar and postwar years in the context of the Westernization of clothing and the birth of an apparel industry. Thus, whereas figure 1 shows the crucial role of designers among intermediaries and apparel companies in the Western setup, designers—whether independent or employed—work as people in charge of drawing the look and function in the Japanese system. They focus on creating garments and do not contribute significantly to building strong brands, unlike their Western counterparts. Consequently, brand management is considered an activity that must support the sales of all the various products manufactured for specific segments of the market, not a way to build a strong identity related to a broad range of goods, including accessories.

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated the emergence and formation of a Western clothing industry and fashion system in Japan between 1945 and 1990. By looking at a broad range of enterprises and actors, it has emphasized that the specificities of the Japanese fashion industry are far from the ethnic-based explanations that fashion scholars have traditionally offered. Street fashion and star designers in Paris are only anecdotal episodes, not full expressions of the industry’s true nature.

The Japanese fashion system must be understood first in the context of a cultural and industrial transplantation. Making Western clothes in Japan after World War II was a new activity that required new knowledge. Young women and housewives took classes at dressmaking schools and purchased fashion magazines to learn how to make Western clothes at home as well as acquire a sense of Western style. This process lasted the entire course of the 1950s and the 1960s. For enterprises, manufacturing and selling Western garments was also a challenge, which was very technological and industrial in nature at its beginning.

Since the 1970s, the growth of ready-to-wear production, driven by a new segment of apparel companies that mass-produced garments and distributed them through department stores and new sales outlets, led to the decline of handmade clothing by housewives. However, the productive and technological paradigm continued to dominate the apparel industry. Fashion was not (and still is not) considered a creative activity—it was a business based on complex and rational market analysis. The focus on the various needs and tastes of the population led apparel companies to adopt extreme segmentation strategies, making the Japanese apparel market home to a huge range of brands that, by extension, have a weak identity.

Consequently, the Japanese fashion system appeared and developed during the second part of the twentieth century on the basis of a technological and production paradigm. The interactions between the various enterprises and actors of the system had clear objectives: to enable the design, mass production, and consumption of Western clothes. Unlike fashion systems in France, Italy, or the United States, the goal was not to invest in creative activities in order to build strong brands and increase profits through ready-to-wear items and accessories. In Japan, apparel companies showed no interest in working on and codeveloping brands with star designers. Designers had to move to Paris or New York to boost their careers and usually ended up pursuing business back in Tokyo as independent small companies positioned in a niche market (creative fashion for wealthy people). Moreover, Japanese apparel companies did not—and could not—diversify toward cosmetics and accessories because of their different business models and the presence of entry barriers, which were profit-making divisions in Europe, due to their lack of fashion brands.

This difference in the nature of the fashion system explains the lack of strong fashion brands in Japan and the intrinsic weakness of the Japanese apparel industry in the global market. As long as the industry was domestically oriented in Japan, there was no problem—it still met customers’ expectations. When powerful Western brands began entering the Japanese market in the 1990s and sagging consumption in Japan forced apparel companies to shift their attention toward the global market, however, the industry’s inherent weaknesses led to a sharp drop-off in competitiveness among apparel companies.Footnote 106 In addition, the relationship between apparel companies and department stores has suffered in light of deflationary conditions dating to the 1990s and the resulting shifts in the macroeconomic situation, considering that it was difficult for them to get away from familiar surroundings.

The fast fashion brand Uniqlo, which was not analyzed in this article as it developed after 1990, is both an exception to and expression of this specific fashion system.Footnote 107 First, it is an exception, as it is the only Japanese brand able to compete in the global market of fast fashion. Its business model, based on the outsourcing of production, the building of a strong, single brand, and the extension of a monobrand store network through the mastering of IT technology, has put it in the same arena as world-class fast fashion brands such as H&M, The Gap, and Zara. Uniqlo is an expression of the Japanese fashion system, too, in the sense that it focuses much more on productive and technological issues than on branding, styling, and storytelling. The cooperation with large Japanese chemical companies such as Toray led to the development of new kinds of fibers and highly functional materials. Uniqlo CEO Tadashi Yanai often says that “Uniqlo is not a fashion company; it’s a technology company.”Footnote 108

The Japanese fashion system thus did not change deeply in its structure since forming after World War II, resulting from a technological- and production-based approach with roots going back to the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 109 Discussing how, why, and to what extent the initial conditions of fashion systems led them to evolve in a path-dependence approach (or not) goes beyond the scope of this article. This would, however, be a major topic for further research on fashion systems in both Japan and the West.

Consequently, this article offered a new interpretation of the Japanese apparel industry’s decline since the mid-1990s and its inability to maintain a competitive edge. The use of the “fashion system” as an analytical tool and the business history approach shed light on the true nature of the Japanese apparel industry. Fashion studies has been a vibrant field in the social sciences for more than two decades, and business historians can contribute to renewing debates and reexamining issues.Footnote 110