Introduction

The consensus used to be that the supremacy of the archetypal Anglo-Saxon corporate legal form required little explanation. Many scholars considered its key elements (legal personality, delegated management, capital lock-in, permanence, transferable shares, limited liability, and shareholder primacy) to be economically indispensable and superior to alternative forms of business organization.Footnote 1 Yet some scholars argue that this economic, deterministic account is fundamentally flawed from a historical standpoint. They claim that, from the perspective of contemporaries living in the 1800s and even the 1900s, the rise to dominance of the business corporation was not inevitable in any sense.Footnote 2

Following the pioneering work of Lamoreaux and Rosenthal and colleagues, business historians have demonstrated that civil-law countries developed a wide menu of organizational forms that could provide more flexibility than, and were at least as favorable to economic development as, the corporation.Footnote 3 In doing so, these historians have managed to “put the corporation in its place,” as other organizational forms have been proven to provide unique advantages over the corporation under certain conditions.Footnote 4

One of these alternatives is the limited partnership. This type of partnership consists of one or more general partners who control the company and are subject to unlimited liability. Limited partners furnish capital and, provided they do not participate in the management of the company, enjoy the protection of limited liability. Some limited partnerships even issued tradable shares that enabled such businesses to raise capital from the broader public.Footnote 5

As a halfway stage between the regular partnership and the corporation, this business form offers some of the advantages of corporations but imposes comparably lower regulatory costs. Moreover, compared with corporate management, general partners with skin in the game—a core characteristic of the limited partnership—are also ceteris paribus more likely to eschew excessive risk-taking, sharing fully in whatever gains or losses were gained by their decisions.Footnote 6 Because of these advantages, limited partnerships provide entrepreneurs a seemingly functional alternative, explaining their well-documented incidence in many civil-law countries, particularly France well into the nineteenth century.Footnote 7 Even in common-law countries, where the form was traditionally believed to have been rarely utilized, a more recent contribution for early nineteenth-century New York has shown that a surprisingly large percentage of firms adopted the limited partnership, thereby contributing to a reappraisal of the historical importance of this organizational form.Footnote 8

Irrespective of historical significance, by the second half of the nineteenth century, the number of limited partnerships and their overall importance had rapidly diminished compared with corporations.Footnote 9 However, given that the limited partnership has received comparatively less scholarly attention, the reasons for this permanent decline have thus far not been studied in detail. For instance, Guinnane and colleagues have pointed out that the main disadvantage of the limited partnership was that silent partners had no say in how their investments were being used, leaving them open to exploitation by the general partner—but the authors do not explore this issue in much detail, never specifiying what this exploitation truly entails or the underlying factors driving it.Footnote 10 Lamoreaux provides more clarity by asserting that if limited partnerships were unusually successful, the general partners could extract excessive payments; still, she only briefly touches upon this issue.Footnote 11 Other scholars, including Freedeman, have explained this sudden decline as being due to a change in legislation that made the corporate form more accessible, but their analysis is focused solely on France.Footnote 12 By extension, we do not know if, and why, this decline also occurred in countries with a different legal system.

This paper makes use of the case of the Bank of Twente (Twentsche Bankvereeniging, hereafter TWBv), founded in 1861, to offer an alternative explanation for the decline of the limited partnership. What makes the case of TWBv so interesting is that, unlike its direct competitors (all of which were incorporated), the TWBv was not only a limited partnership until 1917, but also one of the largest and most important commercial banks in the Netherlands, demonstrating that the limited partnership should not be considered an inferior substitute for the corporate form.Footnote 13 TWBv was also one of the main antecedents of ABN AMRO, which (until it was split up and sold off in 2007) was the world’s sixteenth largest bank.Footnote 14 Its historical and present-day significance makes the advent of this bank a case worth looking into, but it also ensured that its historical records—that is, its paper trail—are easier to track down than those of smaller institutions.

Other than the work of Wijtvliet and van der Werf, little research has been conducted into the history of TWBv.Footnote 15 In contrast to van der Werf’s more overarching historical account, Wijtvliet paid a great deal of attention to the bank’s adoption of the corporate form in 1917. However, his interpretation of the facts leading up toward incorporation is somewhat teleological, framing as it does the adoption of the corporate form as an inevitable outcome toward modernity, with few implications for further research outside of the Netherlands. In contrast, the present article follows the narrative analysis approach, relying on an interpretative model embedded in the literature on the agency problem, to illustrate that the circumscribed use of a limited partnership was rooted in the organizational form having a flaw of its own that, under particular circumstances, created serious agency costs. As the bank grew, so did the agency costs, finally forcing the bank to incorporate.Footnote 16

An analytical narrative of the limited partnership can tell us much about the decline of the limited partnership form and the rise of the corporate form. In addition, a better understanding of limited partnerships deepens our understanding of the history of Dutch corporate governance from the mid-1850s to the early twentieth century. The Netherlands is a country notably missing in the literature on organizational forms. This is all the more surprising considering it is widely considered to be a forerunner in financial development and the birthplace of the corporate form.Footnote 17

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The second section looks at the founding history of the bank. The third section demonstrates that, as the bank grew in size, so did agency costs between general and silent partners. The fourth section focuses on the discussions preceding and ultimately resulting in the bank’s incorporation. The fifth section then provides an interpretation of this historical narrative based on economic theory, and the final section provides a concluding summary.

Adopting the Limited Partnership

Humble Beginnings: 1860s

TWBv originated in the eastern Twente region, the center of Dutch cotton manufacturing and allied engineering works. In 1835 B. W. Blijdenstein finished his legal studies and set up as a notary in Enschede. Adding money dealing to his practice, he gradually expanded that business until, by the mid-1850s, he had become more akin to a so-called cashier. Like most cashiers, Blijdenstein provided collecting and payment services and also dealt in coin, commercial paper, acceptances, and other short-term credit.Footnote 18 New opportunities opened for him when, in the spirit of growing liberalization and laissez-faire approach, the Dutch government ended the practical monopoly of trade with the Dutch East Indies of the Dutch Trading Company (Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij, or NHM), a large colonial trading company loosely modeled on the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC).Footnote 19 Textile manufacturers now needed to arrange and finance their exports themselves, but they often lacked the necessary means or experience to do so. By contrast, Amsterdam- and Rotterdam-based merchant banks lacked the specific know-how concerning and ties to the Twentsche textile industry, which opened a business opportunity for a bank rooted in the local economy.Footnote 20

Spotting this opportunity, Blijdenstein expanded his business. In 1858 he sent his son B. W. Blijdenstein (II) to London to start a firm buying bills for Twente clients.Footnote 21 In 1861 he launched the TWBv as a limited partnership with offices in Amsterdam, Enschede, and London. The bank’s main business consisted of facilitating the export business of the Twentsche textile manufacturers and traders to the Dutch East Indies by offering them consignment credit, providing them with advances, and dealing in bills.Footnote 22

Explaining the Choice of Organizational Form

Much of the existing literature has pointed out that in early nineteenth-century France, companies frequently adopted the limited partnership to escape the costlier governmental authorization associated with incorporation.Footnote 23 In the case of the Netherlands, this was no different.

The upheavals of the late eighteenth century and the occupation of the French had inaugurated a period of economic stagnation in the Netherlands lasting some fifty years. Recovery after the restoration of independence in 1813 proved relatively slow, until the mid-1820s. The lack of an economic impetus meant that most companies did not need to raise substantial amounts of capital.Footnote 24 Consequently, the vast majority of multi-owner firms were organized as ordinary partnerships. Tellingly, the business tax returns for 1826 list only sixteen corporations in Amsterdam.Footnote 25

By the early 1850s, the Dutch economy finally started to industrialize, led by engineering works, sugar refineries, and gas works in Amsterdam and Rotterdam and nascent industries such as the textile industry in Twente and Brabant.Footnote 26 Dutch economic growth, placing new financial, technological, and managerial requirements on traditional businesses, stimulated the increased employment of more complex business forms than the ordinary partnership.Footnote 27 In 1850 there were only approximately 140 corporations for the whole of the Netherlands. By the 1860s this had increased to approximately 300, by the 1880s to 550, and by the early 1900s to more than 3,300.Footnote 28 As in France, however, there were several instances of financial institutions that adopted the limited partnership.Footnote 29 This included the two biggest Amsterdam manufacturers at the time, an engineering company and a sugar refiner, which were both limited partnerships with tradable shares.Footnote 30

The basis of the Dutch legal system at the time was formed in 1811 when Napoleon first introduced the Code de Commerce. In the face of vociferous protest from the business community, the legislature adapted the system before finally accepting it in 1838.Footnote 31 The new commercial code of 1838 recognized three basic forms of business organization: the ordinary partnership (vennootschap onder firma in Dutch); limited partnership (commanditaire vennootschap in Dutch); and finally, the corporation (naamloze vennootschap in Dutch).Footnote 32 The first two were exempt from any bureaucratic procedures other than the registration of a deed of partnership with the local court. By contrast, a corporation required formal statutes drafted by a notary, approved by the Ministry of Justice, registered by the local Chamber of Commerce, and published in the Government Gazette (Staatscourant).Footnote 33

Setting up the TWBv as a limited partnership made sense, given the available options. It represented the middle ground between a regular partnership and incorporation, but it imposed less formal requirements. Indeed, previous scholars such as Wijtvliet have explained the bank’s choice of adopting this form as a means to escape higher regulatory costs associated with incorporation.Footnote 34 However, there were other, more idiosyncratic factors at play that explain this choice. The theoretical literature on the agency problem can help us better understand why TWBv adopted the limited partnership. The essence of this problem is the separation of management and ownership. In their seminal paper, Shleifer and Vishny provide a survey on corporate governance and assert that the agency problem might arise because a firm’s stakeholders assigned to manage the firm (the agent) might have conflicting interests with the owner of the firm (the principal).Footnote 35 This can lead managers to forsake their fiduciary duties to maximize their own personal benefits at the behest of the principal investors, particularly shareholders, and even expropriate them.Footnote 36

Ample research has shown that adopting an organizational form can offer legal protection from such managerial abuse and self-dealings.Footnote 37 At the time, the Dutch legal system allowed for three viable alternatives: the simple partnership, the limited partnership, and the corporate form. Blijdenstein’s budding international mercantile business needed more capital than a simple partnership could provide. Attracting outside investors by turning the business into a corporation stood little chance of success, given the firm’s relative obscurity. But with a limited partnership, Blijdenstein could draw his business associates—at the time primarily consisting of Twente’s textile manufacturing elite—into his bank, which was important to them, as its primary services facilitated their trade.Footnote 38 Limited liability protected their investments, and for this they were willing to abdicate their direct influence over the management of the firm.Footnote 39

Given the menu of organizational forms available in the Netherlands at the time, TWBv effectively had to choose between adopting the limited partnership or incorporation. According to relevant historical and legal research, the main differentiator between both forms is the general partner’s unlimited liability.Footnote 40 In theory, unlimited liability ensures that general partners have more skin in the game, making them ceteris paribus more likely to eschew excessive risk-taking than managers of a corporation.Footnote 41 Using more standard corporate governance terminology, it serves as a contingent, long-term incentive contract ex ante to align the interests of both set of partners.Footnote 42 In layman’s terms, the general partners’ personal liability reduces the silent partners’ monitoring costs and risks. Because the incentive effects of unlimited liability on the degree of risk-taking cannot readily be duplicated through creditor monitoring of corporate managers, this makes the limited partnership form appealing for external creditors.Footnote 43 This is especially the case in an inherently risky business such as banking.Footnote 44

As the bank’s manager, owner, and future general partner, B. W. Blijdenstein himself preferred the limited partnership over incorporation, because it imposed fewer regulatory costs.Footnote 45 Additionally, and arguably more importantly, it would consequently enshrine his control over the company—not only would a limited partnership remove silent partner voices from the management, it also provided more insulation from abdication, as silent partners could not readily get rid of Blijdenstein.Footnote 46 The former consequence was simply the price silent partners had to pay for limited liability, the latter was because removing the general partner would result in the partnership’s dissolution.Footnote 47 Blijdenstein, a juris doctor who specialized in contractual law and corporate law, showed an acute awareness of the aforementioned theoretical benefits of unlimited liability, pointing out the reduced monitoring costs as a means to persuade his fellow—and future—silent partners to invest.Footnote 48 Nevertheless, despite his best efforts, his initial attempt in 1858 to set up the TWBv as a limited partnership was not successful. However, three years later in 1861, he succeeded.Footnote 49

The Limits of the Limited Partnership

From Provincial Upstart to Metropolitan Leader: 1860s–1900s

When Blijdenstein died in 1866, his son B. W. Blijdenstein (II) succeeded him as general partner together with a close associate, J. H. Wennink. B. W. Blijdenstein (II) was thoroughly trained by his father, shared the same business acumen, and could draw on a valuable experience garnered as manager of the London branch. Under B. W. Blijdenstein (II) the bank started to branch out. In 1868 the firm H. Ledeboer & Co. was founded in Almelo. Similar to Enschede, it had a growing textile industry making it the perfect venturing point. Moreover, by expanding its operations to Almelo, TWBv attempted to contend the Rotterdamsche bank’s growing aspiration to enter this market. In the years following, the TWBv continued to expand. In 1878 de Jongh & Zoon, a stockbroker (i.e., commissionair) based in Rotterdam was acquired and was continued as the Wissel–en Effectenbank. In 1884 the Stichtse Bank was founded in Utrecht. In 1889 the TWBv acquired the cashier Bergsma & Dikkers located in Hengelo, and in 1893, the Bank voor Effecten–en Wisselzaken located in The Hague was established.Footnote 50

Apart from these domestic expansions, the TWBv also expanded abroad. It started with the establishment of Blijdenstein & Co. in London in 1859. In 1875 the British and Foreign Exchange and Investment Bank was acquired jointly with its subsidiary, Ancienne Maisson Leon & Dreher Comptoir de Change, located in Paris. In 1890 the TWBv continued its international expansion and founded the Gronauer Bankverein Ledeboer located in Granau. The purpose of this bank was to provide funding to the Westphalian textile industry. In this regard, the acquisition in 1897 of the Rheiner Bankverein Ledeboer located in Rheine and TWBv’s participation in the Westdeutsche Vereinbank located in Münster are also of note.Footnote 51

These branches were generally newly established firms, supported financially by Blijdenstein (II). Only seldom did TWBv fully acquire existing firms. Consequently, these branches were tied to the TWBv via a personal connection and were mostly independent. The managers of these firms, however, were held personally liable for all losses brought on by negligence, oversight, or other personal misbehavior. In return, they would share in the profits.Footnote 52 Anecdotal evidence for TWBv’s subsidiary Ledeboer & Co. suggests that this incentivized local management to properly manage their business and avoid unnecessary risks.Footnote 53 More importantly, it aligned the interests of these branch managers with those of central management and allowed the TWBv to have a widespread network of branches, almost a decade before its main rivals, the Bank of Rotterdam (Rotterdamsche Bank, hereafter RB) and the Bank of Amsterdam (Amsterdamsche Bank, hereafter AB), started branching out.Footnote 54

In tandem with its geographic expansion, the TWBv also expanded its business ventures. One of these was the Twentsche credit union (Twentsche Credietvereeniging, hereafter TWCv), an independent credit union within its fold operating similar to a mutual association with jointly liable members.Footnote 55 TWBv had set up the TWCv in 1871 in response to the growing success of the Amsterdamsche Credietvereeniging, founded in 1853, and the Geldersche Credietvereeniging, founded in 1866. The bank thereby sought to expand its circle of clients to attract the middle class while shifting the risk to its members.Footnote 56 It also began collecting deposits on a larger scale and became more actively involved in industry financing. Consequently, between the early 1860s and the late 1910s, the TWBv was the first Dutch commercial bank to steadily progress away from short-term mercantile financing toward serving a wider and more diverse customer base.Footnote 57

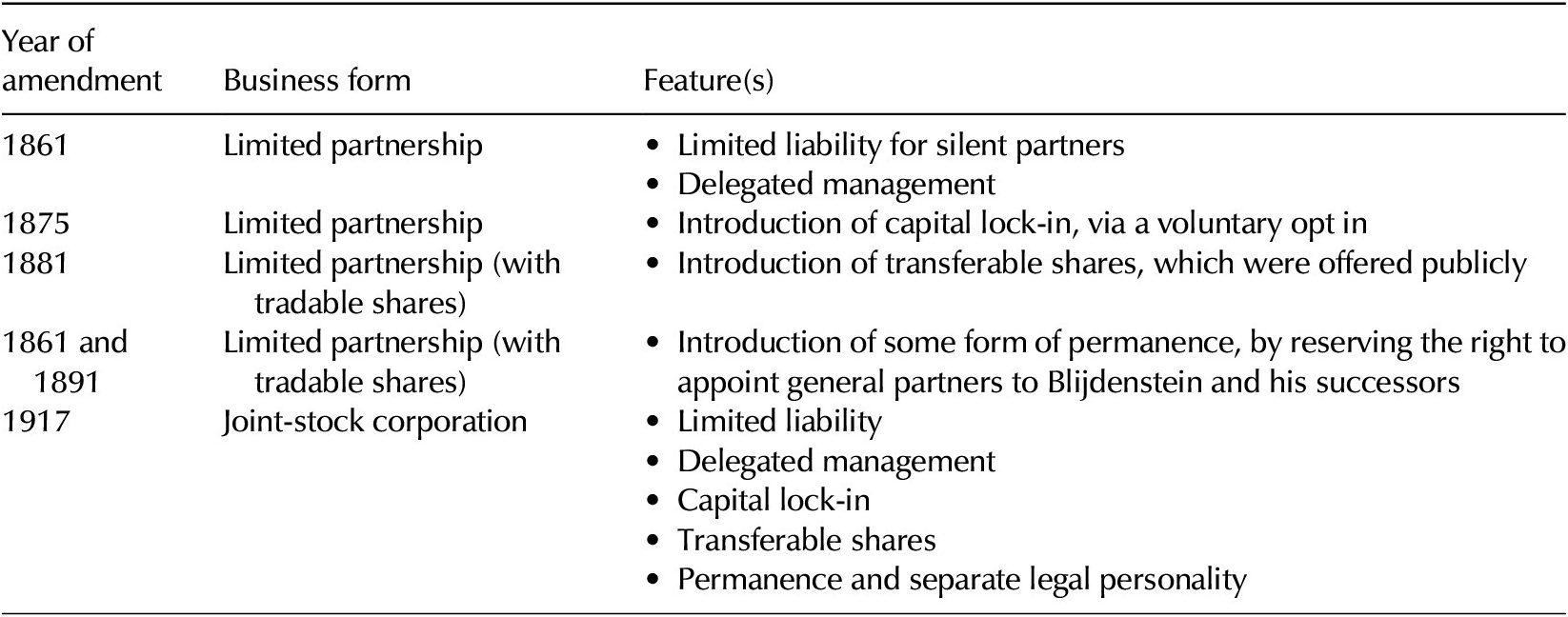

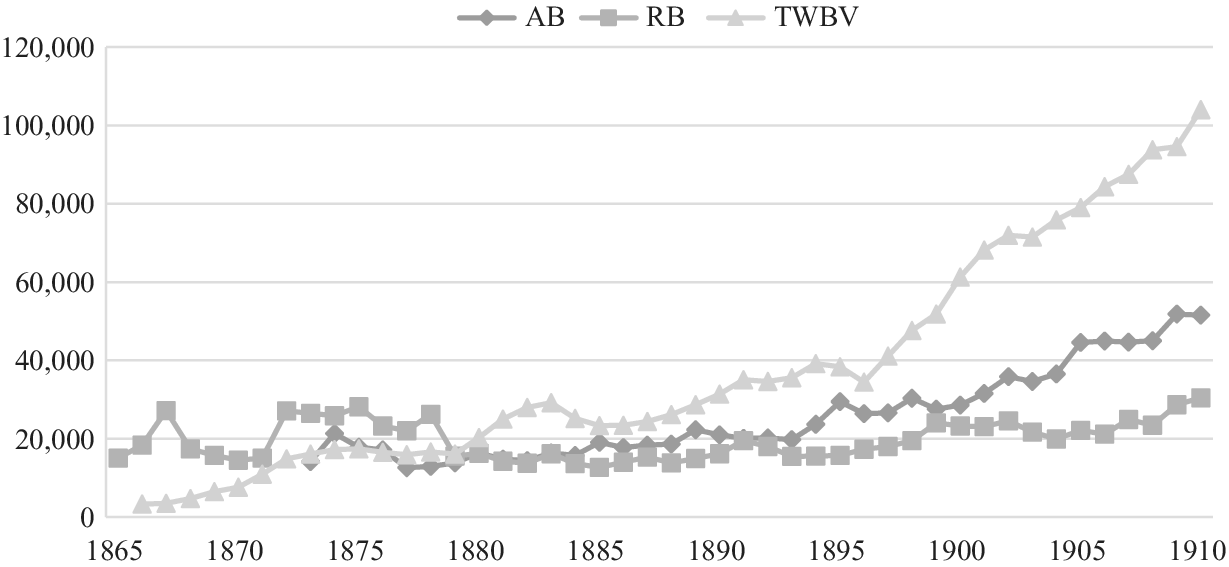

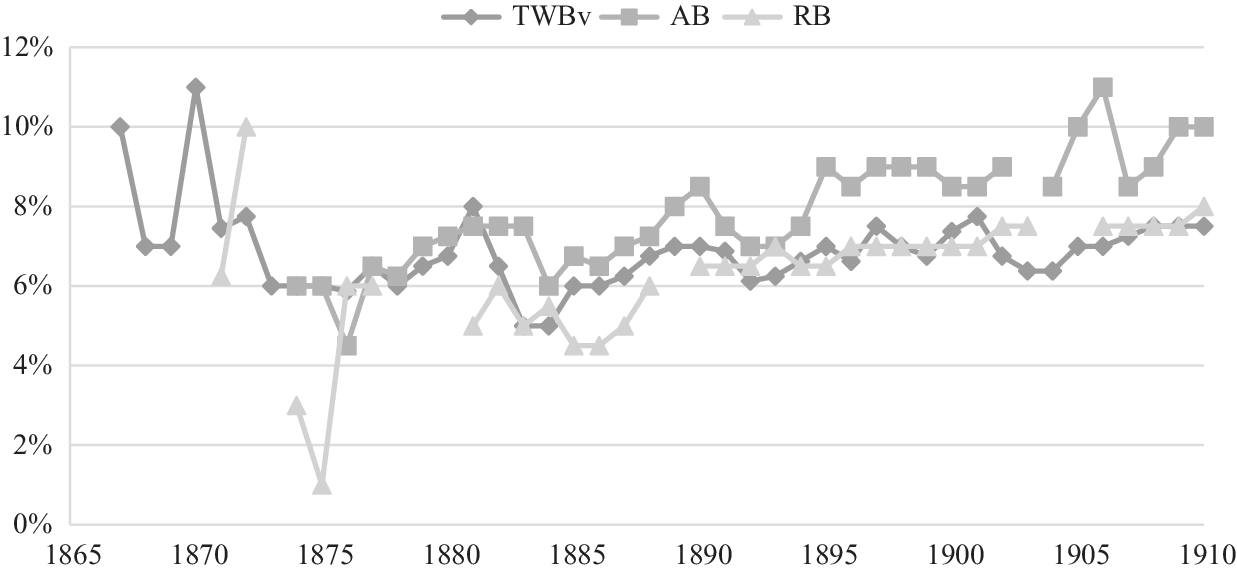

As a result, it became the largest and most profitable commercial bank in the Netherlands, as shown by the total assets and net profits of the three largest Dutch banks. This is illustrated by Figures 1 and 2. More precisely, Figure 1 indicates that by 1890, TWBv’s total asset size was almost equal to that of its direct competitors, the AB and the RB, combined. By 1910, the TWBv was almost twice as large as the AB and more than three times as large as the RB.Footnote 58 Figure 2 illustrates a similar pattern in terms of net profits.

Figure 1. Total assets of the three largest Dutch commercial banks (in 1,000 guilders, 1865–1909). AB, Amsterdamsche Bank; RB, Rotterdamsche Bank; TWBv, Twentsche Bankvereeniging.

Source: Annual reports of respective banks (1865–1910).

Figure 2. Net profits of the three largest commercial banks (in 1,000 guilders, 1865–1909). AB, Amsterdamsche Bank; RB, Rotterdamsche Bank; TWBv, Twentsche Bankvereeniging.

Source: Annual reports of respective banks (1865–1910).

Trial of Strength

The status of limited liability excluded the silent partners from running the business but neither the law nor the TWBv’s statutes gave further specifications as to the firm’s corporate governance apart from annual meetings and accounts. Therefore, the TWBv’s expansion turned into a trial of strength about how the partnership was supposed to work, leading to a series of adjustments to the original statutes. Over the years, this trial of strength raged over three main issues: the bank’s capital basis, corporate governance structure, and distribution of profits. Three phases can be discerned across the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s, respectively.

1860s–1870s

The limited partnership form provided the TWBv with a practical alternative to the corporate form, as it could theoretically bring unlimited amounts of money into the business from an unlimited number of outside investors who would all enjoy limited liability for their participation. Furthermore, it preserved the personal connection between B. W. Blijdenstein and his family members and close business associates whom he approached as investors and partners—be it silent ones—instead of merely shareholders.Footnote 59

In TWBv’s founding years, its statutes did not require the small group of silent partners to pay a fixed amount. Instead, each partner pledged 10,000 guilders as callable capital.Footnote 60 That sum proved to be insufficient almost immediately, prompting a first amendment of the company statutes in 1863. This gave silent partners the opportunity to deposit at least 10,000 guilders, withdrawable at three months’ notice, to which another 1866 amendment added deposits withdrawable at twelve months’ notice, allowing the silent partners to threaten the dissolution of an otherwise successful business by liquidating their investments. The following year, the bank’s constituency was widened by scrapping the 10,000 guilder minimum deposit and allowing investors outside Twente into the partnership.Footnote 61 These measures had the desired result. By 1868, the total number of silent partners exceeded seventy, with a joint participation of more than 750,000 guilders. The total value of all deposits by silent partners in the meantime had risen to more than 437,000 guilders.Footnote 62

With regard to corporate governance, few noteworthy amendments were made throughout this period. The statutes did little more than appoint B. W. Blijdenstein as general partner with the obligation to produce annual reports and convene general partnership meetings. Partners discussed proposals to change the statutes in these meetings and approved them with a two-thirds majority. The only subtle change came when Blijdenstein’s son B. W. Blijdenstein (II) joined him as general partner in 1861. The bank’s statutes were then amended, reserving the right to appoint general partners to Blijdenstein and his successors, effectively securing the family’s hold in perpetuity and foreshadowing future conflicts of interest between both sets of partners.

Finally, the efforts to widen the constituency of the limited partnership went hand in hand with changes to the distribution of profits. Initially, the silent partners received only some commercial benefits, such as a reduction of charges on discounting and handling other commercial paper.Footnote 63 This type of reward sufficed to persuade Blijdenstein’s Twente friends to back him with callable capital, but as the bank developed and needed more capital, remuneration had to change. During the 1860s, silent partners were first granted a favorable 7 percent interest on deposits. From 1866, silent partners received a dividend payment of 7 percent, then the general partners obtained 35,000 guilders, and any remaining profits were then split equally.Footnote 64

1870s–1880s

The successful amendments to increase the bank’s capital basis, however, failed to address a more fundamental legal limitation of limited partnerships: the lack of permanence. While the aforementioned right of appointment ensured some continuity by effectively securing the family’s hold in perpetuity, it did not protect fully against liquidation. Silent partners could still withdraw their guarantee and/or deposits and threaten an otherwise successful business with dissolution. This possibility inaugurated new changes in the rules governing the bank’s capital base aimed to prevent dissolution from happening.

In 1870–1871, the partners agreed on a first step toward locking in the silent partners’ capital. Henceforth, all capital pledged had to be paid up either in cash or as securities deposited with the bank, in return for formal share certificates classed respectively as A or B. A shareholder could trade both classes, but because both were registered shares (aandelen op naam) in practice, liquidity was low, as one could only sell them to an inner circle of closely associated businessmen.Footnote 65 The second step was taken in 1875, when the general partners and the silent partners agreed after some discussion to introduce a voluntary lock-in of capital for a period of five years. By 1876, a total of 178 silent partners had decided to fully or partly opt in for a total sum of almost 1.5 million guilders.Footnote 66

In return for this capital lock-in, silent partners pushed forward statutory amendments to formalize corporate governance. The interest of silent partners would henceforth be represented by a board of non-executive directors (raad van commissarissen) composed from their numbers. The board verified the annual accounts and advised the general partners about the admission of new silent partners.Footnote 67 In practice, the board’s influence over company affairs remained limited due to Blijdenstein (II)’s interference and hardly compensated the silent partners’ loss of control over their stakes through the 1870–1871 capital lock-in. To put it in more standard corporate governance terminology, it did not reduce the discretionary control rights of the general partner.Footnote 68

Parallel to the corporate governance issues, the partners argued about the distribution of profits. In 1871 Blijdenstein (II) proposed that, instead of reserving a dividend payment of 7 percent to the silent partners, all partners would share equally in the profits and receive a 4 percent dividend. Any remaining profits would then be split 45 percent to the silent partners and the general partner’s 45 percent to a reserve fund; the remaining 10 percent would serve as remuneration for the auditing committee.Footnote 69 This fund would serve to guarantee the silent partners their 4 percent dividend at all times and would also provide a buffer against losses, thereby lowering their risk exposure.Footnote 70 The silent partners were wary of accepting a cut in dividends from 7 percent to 4 percent. To persuade them, Blijdenstein (II) raised the dividend to 5 percent and offered to leave the silent partners’ risk-adjusted return unchanged by halving their exposure. Until then, the silent partners were only entitled to full dividend payouts if they had pledged an initial sum of 10,000 guilders and deposited another 10,000 guilders. That requirement was now dropped to give silent partners with a share of 10,000 guilders or fewer the same entitlement, while the general partner’s 45 percent share of remaining profits still went into the reserves. In 1875 the silent partners’ dividend rate was increased to 6 percent in return for their consent to a voluntary opt in of a minimum of 20 percent of their capital for five years. Footnote 71

1880s–1890s

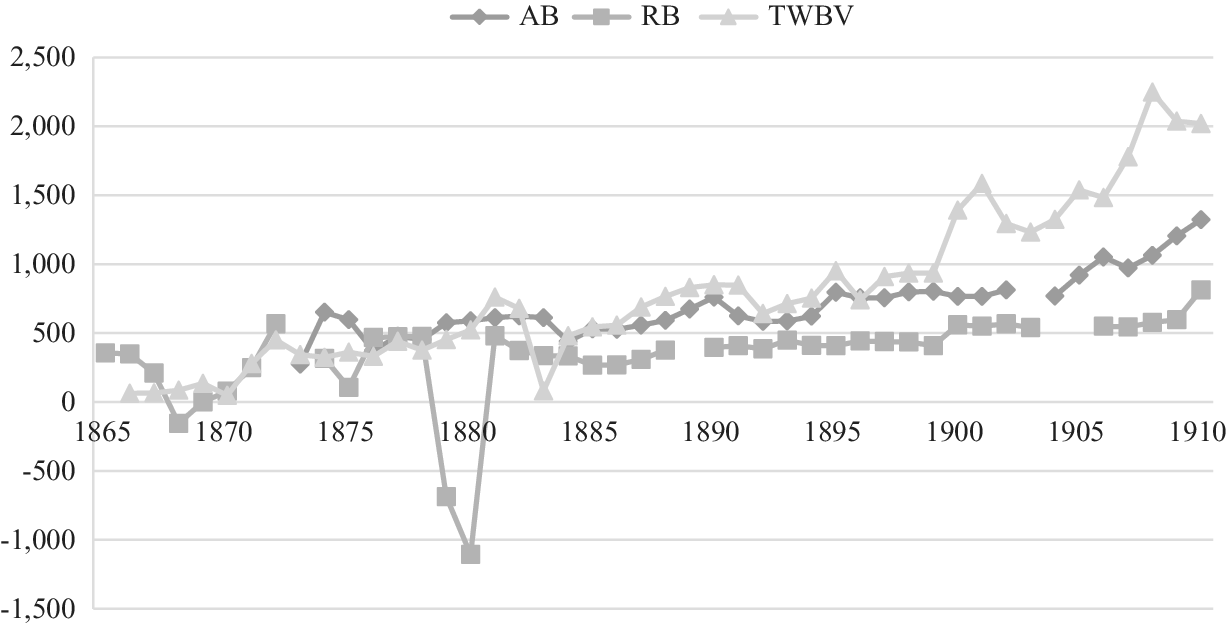

Via the 1870–1871 and the 1875–1876 reforms, the TWBv had managed to introduce registered shares to a relatively close circle. It had achieved this by making clever use of the flexibility provided by Dutch legislation to circumvent some of the main disadvantages of the limited partnership. It did not stop there. To further widen its capital base and open the partnership to external investors, the TWBv started issuing tradable shares on the Dutch capital markets, once more profiting from the laissez-faire regulatory regime at the time.Footnote 72 Two successful public offerings by the TWBv followed, one in 1881 raising 3.1 million guilders and another one in 1899 of 2 million. Publicly issuing tradable shares on the capital market allowed the TWBv to keep pace with its competitors, the AB and the RB, both of which were incorporated (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Liabilities of the three biggest Dutch banks (in million guilders, 1875–1910). AB, Amsterdamsche Bank; RB, Rotterdamsche Bank; TWBv, Twentsche Bankvereeniging.

Source: Annual reports of respective banks (1865–1910).

The TWBv de facto transformation into a limited partnership with tradable shares brought forward further changes to the corporate governance structure. In 1887 Blijdenstein (II) appointed an executive committee (raad van bestuur) consisting of H. Ledeboer, A. J. Brink, and A. Roelvink, like him fully liable and designated as his future successors, but technically not general partners.Footnote 73 The three were TWBv career men who enjoyed the silent partners’ confidence. However, the appointments might have been an opportunistic move on Blijdenstein (II)’s part to limit his exposure to the bank’s risk at a time when Dutch banking experienced some turbulence.Footnote 74 Four years later, after the turmoil has passed, B. W. Blijdenstein (II) revoked this decision and named his eldest son W. B. Blijdenstein (III) as his successor without consulting the silent partners. A few years later he consolidated the family’s hold on the bank by appointing his younger sons J. T. Blijdenstein (III) and T. W. Blijdenstein (III) to the executive committee, naming them as successors should Willem prove unable or unwilling to fulfill this task.Footnote 75

These decisions, taken without consulting the silent partners, resulted in vociferous complaints about Blijdenstein (II)’s nepotism and high-handedness. In response, Blijdenstein (II) boosted his personal stake from 300,000 guilders in 1895 to 1.5 million guilders on total shareholders’ equity approximating 11 million guilders by the early 1900s. Though downplaying this step as merely “occasional,” Blijdenstein (II) clearly meant to silence his critics by becoming the banks’ single largest shareholder, further entrenching his family’s control over the bank.Footnote 76

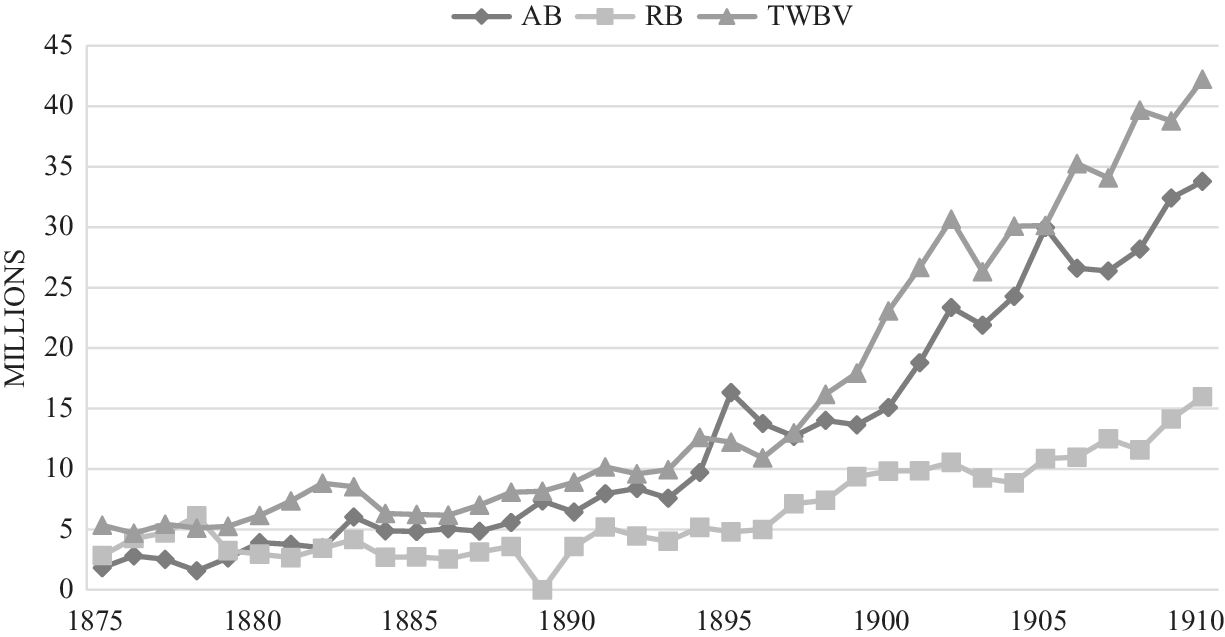

In parallel with B. W. Blijdenstein (II)’s efforts to increase his family’s grip on the bank, he also pushed for a redistribution of profits. First, the statutory defined lump sum paid to general partners was raised from 35,000 guilders to 50,000 guilders. Simultaneously, the silent partners’ dividend payouts were reduced from a guaranteed rate of 6 percent to 4 percent, topped up with an additional 2 percent conditional on profit levels. As payouts continued to fluctuate around 6 percent as before, the silent partners appear not to have lost out from this change at first sight, but appearances deceive. Figure 4 shows the dividend payouts to shareholders and silent partners of the three biggest commercial banks during the years 1865–1910. While TWB’s initial payouts were comparable to those of its rivals, they began lagging during the 1890s, even though for most of this period the TWB’s profits exceeded those of the RB and the AB by quite a margin (Figure 2). Bank reserves were comparable between the three banks, so if TWB’s payout rates were considerably lower, we can confidently assume that its general partner’s profit share far exceeded what the managers at the RB and the AB received. A closer analysis of the annual reports corroborates this fact. By the early 1900s, royalties (tantièmes) for the management of the RB and the AB fluctuated at around 60,000 and 120,000 guilders, respectively. At the same time, the general partners of TWBv received at least 210,000 guilders.Footnote 77

Figure 4. Dividend payout (in percent) at the three largest commercial banks (1865–1910). AB, Amsterdamsche Bank; RB, Rotterdamsche Bank; TWBv, Twentsche Bankvereeniging.

Source: Annual reports of respective banks (1865–1910).

The Long Road Toward Incorporation: 1900s–1920s

Tensions between B. W. Blijdenstein (II) and the silent partners reached their zenith by the early 1900s. Blijdenstein (II)’s most critical silent partners found an ally in Roelvink, second only to Blijdenstein (II) as the bank’s most influential manager. Roelvink was convinced that the TWBv needed to transform into a corporation if it was to face the challenges of modernization. In 1906 he presented a plan to adopt the corporate form, triggering a fierce discussion with Blijdenstein (II), who considered the proposal a takeover attempt by Roelvink, aimed at destroying his life’s work. The rivalry between the men was fierce. In one of Blijdenstein (II)’s letters to Roelvink, the former cynically uttered that due to this reform “the era of Adam Roelvink would commence,” even going as far as to state that “whilst he was alive, he would only accept the reform of the TWBv to a corporation, if it was but a façade.” Clearly, he had no intention of relinquishing control.Footnote 78

Even so, Blijdenstein (II) reluctantly agreed to appoint a committee tasked with exploring the possibility of adopting the corporate form. The committee, consisting solely of individuals favorable to Blijdenstein (II)’s demands, presented its result in early March 1907. It recommended the bank adopt the corporate form but failed to address the silent partners’ more substantial concerns, namely that the family kept control of the company and that shareholder influence remained limited at best.Footnote 79 Appalled by this blatant disregard of their interests, the silent partners rejected the proposal out of hand.Footnote 80 The ensuing mutual discontent halted any further progress toward a potential compromise.Footnote 81

The prolonged struggle over the bank’s reserve fund, introduced during the early 1870s and created from the general partners’ 45 percent surplus profits share, further reinforced this standoff.Footnote 82 Though Article 9 of the bank’s statutes did acknowledge that general partners owned that money by giving them a claim to a share in the reserves on Blijdenstein (II)’s death or retirement, they were otherwise required to leave it untouched.Footnote 83 In the debate following Roelvink’s 1906 proposal to adopt the corporate form, Blijdenstein (II) used his claim on the bank’s by now very considerable reserves to block incorporation. Roelvink had proposed creating a new reserve fund (B) fully owned by the bank to which surplus profits henceforth would be channeled. The original reserve fund (A) would remain part of the bank’s reserves but would gradually be whittled down by annual payouts to the general partners. Blijdenstein (II) flatly refused to accept this solution, asserting that the bank was not a corporation and should not operate like one.Footnote 84

The stalemate gradually came to an end following the retirement of B. W. Blijdenstein (II) in 1910.Footnote 85 Yet even in retirement Blijdenstein (II) obstructed the process toward incorporation until his death in 1914. Nevertheless, after prolonged negotiations, the TWBv at long last incorporated in 1917, roughly along the lines proposed by Roelvink a decade earlier. The silent partners became proper shareholders of an incorporated bank with all the associated shareholder rights, including a fully operational board of non-executive directors to represent their interests, the right to vote on important decisions during general shareholder meetings, and a more proportional share of the profits.Footnote 86

The Blijdensteins, however, extracted a high price for incorporation. Their share in the reserve fund would be left untouched until 1931, but they received shares worth 1.4 million guilders for goodwill, making them the largest shareholders. W. B. Blijdenstein (III), confirmed as managing director with his two brothers J. T. Blijdenstein (III) and T. W. Blijdenstein (III), received a lump sum of 350,000 guilders plus royalties valued at 125,000 guilders annually for a period of fifteen years.Footnote 87 The family lost the privilege to co-opt new members of the executive committee without shareholder consent, however, and those executives could now be voted out of office if they neglected their duties. Thus, the Blijdensteins’ influence remained strong after the adoption of the corporate form, but their grasp quickly diminished. By the mid-1920s, the old reserve fund had been partially amortized and W. B. Blijdenstein and J. T. Blijdenstein (III) had resigned from the bank’s executive committee.Footnote 88

Explaining Agency Costs and the Push Toward Incorporation

While the theoretical literature on the limited partnership is relatively scarce,Footnote 89 it is possible to rely on the extensive literature on the agency problem to understand better the roots of the trial of strength that intensified over the years.Footnote 90 Agency problems and associated agency costs result from the separation of ownership and control within an organization. They are characterized by opportunistic behaviour, including self-dealings and shirking. The asymmetric relationship between the principal and the agent can also lead to moral hazard. A moral hazard may occur when the risk-taking agent’s cost-benefit trade-off differs from that of the cost-bearing principal, particularly when the agent does not bear the full cost of that risk and is thus incentivized to take on excessive risks.Footnote 91

A rich body of theoretical and empirical literature, focusing mainly on the financial sector, has illustrated that increasing the agent’s skin in the game, either through increasing managerial equity ownership or unlimited liability, effectively reduces the moral hazard.Footnote 92 The limited partnership form, in which unlimited liability is imposed on the general partner, achieves just that. It can thus be expected to offer silent partners better protection against this particular agency cost than the corporate form. Anecdotal evidence does indeed suggest that B. W. Blijdenstein (II) was less prone to excessive risk-taking than his managerial counterparts.Footnote 93 Furthermore, earlier scholars have pointed out that his prudence might be one reason why TWBv weathered the financial turmoil of the 1880s better than its direct competitors.Footnote 94

Conversely, this advantage vis-à-vis the corporate form does not mean that the limited partnership is exempt from the agency problem. In fact, because it is legally stipulated that the limited partner will lose the limitation of liability if he or she intervenes in management, the general partner has (all things being equal) more discretionary control rights compared with the manager of a corporation.Footnote 95 Furthermore, because the limited partners have limited rights to participate in day-to-day operations and challenge and/or approve major decisions, one can expect a higher degree of information asymmetry between the general partner who manages the company and the limited partner who is unable to monitor these decisions properly. This default, one-sided allocation of authority in a limited partnership implies the prospect of agent abuse of discretion not only still exists, but may even be heightened vis-à-vis a corporation.Footnote 96

Such abuse of discretion can take many forms. Given that an inevitable consequence of unlimited liability is that an uninsured loss can amount to the general partner losing a substantial percentage of his personal wealth, a risk-averse general partner may avoid risky projects to prevent such a loss—even those projects that are in the silent partners’ best interests. More important, the general partner may also demand financial compensation that would offset the risk of such loss.Footnote 97 The latter might then inspire the general partner to preserve the one-sided allocation of authority for as long as possible, or at least keep it in the family. The case of TWBv adds empirical backing to these theoretical views and demonstrates that as the bank grew, the agency problem grew in tandem. It also underlines the importance of social capital as a means to limit this problem—if the social interconnections between the partners fade over time, the agency costs will increase.

TWBv’s initial statutes in the 1860s–1870s, reflected the close-knit world of Protestant Twente cotton manufacturers with overlapping family ties and consequently ensured a smooth running of the limited partnership. Silent partners felt they were fairly rewarded for their investments and perceived the remuneration of 35,000 guilders for Blijdenstein to be fair.

The 1870–1871 lock-in facilitated the partnership’s growth, but this came with a price. Silent partners in particular forwent a credible threat of a sudden and untimely dissolution of an otherwise successful business, reducing their ability to indirectly influence the decisions of the general partner.Footnote 98 This asymmetry between the general and silent partners was further aggravated by the fact that the existing social ties that existed between B. W. Blijdenstein (II) and his family members and close business associates had eroded over time. Many of the new investors came from outside Twente and were in no way related to Blijdenstein (II) and could not exert any social pressure.Footnote 99 Furthermore, as the bank now possessed a firm capital base, Blijdenstein (II) became less concerned with attracting new outside investors and more with assuring his own large profit take.Footnote 100 Blijdenstein (II)’s decision to reduce the silent partners guaranteed dividend rate from 7 percent to 4 percent can be seen in the light of his attempts to increase his own compensation at the expense of his investors.

As the bank’s constituency grew in the 1880s–1890s as a consequence of its decision to issue tradable shares, so did these agency costs. Having a powerless non-executive board might have sufficed for the closely related Twente crowd, but the rapidly rising number of outside shareholders disagreed and openly began criticizing general partner B. W. Blijdenstein (II)’s methods of conducting of business. The complaints gained all the more traction when Blijdenstein (II) decided to raise the statutory defined lump sum paid to general partners from 35,000 guilders to 50,000 guilders. In accordance with economic theory, Blijdenstein (II) insistently defended this increase by arguing that because he stood to lose everything, he was entitled to a proper remuneration, making use of his unlimited liability status to demand compensation that would offset his personal losses.Footnote 101

Clearly, his attempts to increase his remuneration in accordance with the greater exposure to potential losses following the bank’s growth were successful. According to van der Werf, Blijdenstein (II)’s yearly income had increased from 110,000 guilders in 1885 to almost 365,000 guilders by 1910. Simultaneously, he managed to grow his personal fortune from approximately 960,000 guilders to more than 3 million guilders.Footnote 102 Understandably, Blijdenstein (II) became increasingly resistant to relinquishing his family’s control over a lucrative business. The process to entrench his family’s grip over the bank started in 1861, when the Blijdensteins reserved the right to appoint future general partners. It culminated in the decision of B. W. Blijdenstein (II) to favor his younger sons J. T. Blijdenstein (III) and T. W. Blijdenstein (III) as his successors, over the silent partners’ preferred candidates. His reluctance to give more voice to the silent partners, despite earlier concessions, added further salt to the wound for the silent partners, who were already frustrated that so much of the bank’s profit was extracted by the general partner. The consequence of all of this was that from the perspective of the silent partners, the benefits of the limited partnership as means to reduce monitoring costs no longer outweighed the agency costs resulting from differences in risk preferences. Understandably they increasingly pushed for adopting the corporate form.

The decision to incorporate, however, was not a one-off decision, but the outcome of a long and difficult process centered around the rivalry between Blijdenstein (II) and Roelvink, which embodied the conflicts of interests between the general partners and the silent partners, respectively. Tensions continued to accrue until Blijdenstein (II)’s retirement and subsequent death in 1914.

More or less at the same time, competition in Dutch banking increased as takeovers by the RB triggered a concentration movement and a growing popularity of the German universal banking model.Footnote 103 The fact that the governmental procedures concerning incorporation were made more lenient after 1896 further contributed to the increase in corporations, as this made the form more easily accessible, and thus more desirable, even for smaller firms.Footnote 104 As a result, the number of corporations soared in the beginning of the twentieth century, reaching almost seven thousand by 1910 and more than fifteen thousand by the 1920s. As the popularity of corporations grew, partnerships became steadily less common, albeit they still accounted for the vast majority of both new and existing firms. In contrast, limited partnerships, already in decline after the introduction of the 1838 Code, all but disappeared. Their numbers fluctuated between fifty and one hundred throughout the entirety of this period.Footnote 105

Throughout these changing socioeconomic circumstances, the TWBv appeared to lose ground compared with its direct rivals, further prompting shareholder calls to push through reforms, most notably incorporation. Unlike their by now deceased father, Blijdenstein (II)’s sons were more inclined to support Roelvink’s plans to incorporate, willingly abdicating some of their control over the bank to enjoy the protection of limited liability.Footnote 106 This was considered necessary to ease the tensions between the sets of partners. To sum up, while voices in favor of incorporation were heard for over a decade, it was this reinforcing combination of endogenous factors related to surmounting agency costs and exogeneous factors related to the death of Blijdenstein (II) and the concentration movement in the Dutch banking sector that finally drove TWBv to incorporate in 1917.

Conclusion

In many countries, the limited partnership, was seen as a viable alternative to the corporation up until the first half of the nineteenth century. Afterward, the form quickly went into decline, losing out in favor of the corporation. Via an analytic narrative of TWBv founded in 1861, this paper adds to our understanding of the circumscribed use of the limited partnership in more recent times. By process-tracking the bank’s amendments to its company statutes throughout the 1860s–1890s, it was demonstrated how limited partnerships, unlike regular partnerships, could provide the capital lock-in and the liquidity of transferable market shares necessary to prompt large-scale investments.Footnote 107 Simply put, the limited partnership form did not inhibit TWBv from competing with rival commercial banks, in particular the AB and the RB, both of which were incorporated. Even so, by illustrating that TWBv and agency costs between general partners on the one side, and silent partners on the other, grew in tandem, this paper substantiated earlier explorations for the narrower use of the limited partnership as a business form when compared with the corporate form.

The limited partnership form should therefore not be considered to be an inferior substitute for the corporate form, utilized solely to avoid more stringent regulatory requirements, but rather one that offers certain net benefits to specific firms in specific circumstances. As this case demonstrated, the limited partnership reduces the general partner’s propensity for moral hazard, while incentivizing self-enrichment vis-à-vis a corporate manager. It follows that the benefits of the limited partnership best materialize for small to medium-sized firms in which both set of partners are personally connected and/or when the firm engages in intrinsically high-risk/high-reward activities. These context-specific benefits explain the form’s temporary success in the early nineteenth century, but also why some current-day enterprises—particularly venture capitalists—choose to adopt this form.Footnote 108

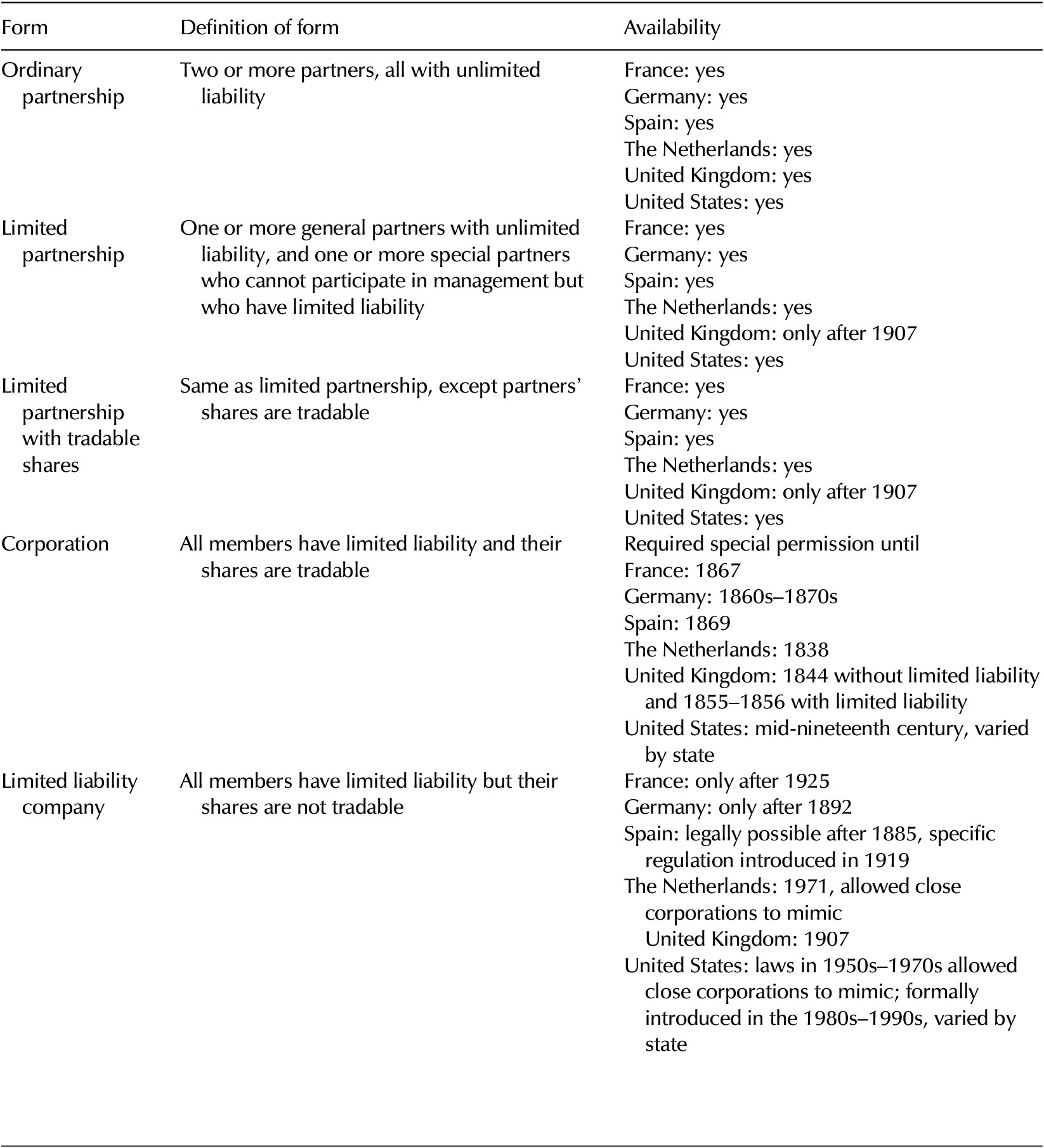

Appendix 1. The menu of organizational choices in France, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States

Appendix 2. Overview of the most noteworthy amendments to the business form