Introduction

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the City of London (hereafter the City) emerged as a center of world commerce and finance.Footnote 1 The City’s rise to preeminence was connected to the expansion of the British empire over the same period. London was the empire’s political, economic, and cultural hub, providing much of the energy and capital driving British trade and colonization, and benefitting from the wealth and knowledge pouring in from overseas. The transatlantic trade in captive Africans and the exploitation of enslaved African people on plantations in the Caribbean was central to the prosperity of the eighteenth-century empire, and the City played a significant and formative role in Britain’s emergence as a leading European slaving power. London merchants helped to finance the first recorded English slave trading voyages undertaken by the privateer John Hawkins from 1562–69 and, by the 1640s and 1650s, merchants in the City were financing the development of a sugar plantation economy in Barbados and supplying the island with enslaved African labor.Footnote 2 Thereafter, London became a prominent port town in the import and reexport of tropical commodities produced by enslaved African people in the British Caribbean.Footnote 3

London was the center of the seventeenth-century British slave trade. The Royal African Company (founded 1660, reincorporated 1672) drew much of its capital from aristocrats and the “middling sort” living in the City and its environs, and trafficked approximately 150,000 captives across the Atlantic between the 1670s and 1720s.Footnote 4 The locus of the British slave trade shifted to Bristol and Liverpool during the 1720s, but the financial services industry in the City still helped to provide the long credit and marine insurance that underpinned the prodigious expansion in Britain’s trafficking of African captives after 1730.Footnote 5 Equally important was London’s role in plantation finance. West India merchant houses specializing in the trade in slave-grown commodities also acted as bankers for Caribbean planters, extending loans secured on plantations and enslaved people.Footnote 6 London’s longstanding and multifaceted commercial and financial role in the slave and plantation trades meant that, by the nineteenth century, individuals and institutions in the City had developed dense and intricate transatlantic networks that connected them with merchants and planters in the British outports and the Caribbean. At the time of abolition in the 1830s, new colonies with slave-based economies that had entered the empire more recently—including Guiana, Trinidad, St Lucia, Mauritius, and the Cape of Good Hope (hereafter the Cape)—were in the process of being integrated into these networks by City merchants and bankers.Footnote 7

There is mounting interest among historians in the role of transatlantic slavery in the making of the City of London. In Capitalism and Slavery (1944), Eric Williams was the first to highlight the role of the slave trade and plantations business in stimulating the City’s banking and insurance industries. The empirical basis for Williams’ analysis was developed and his arguments were further refined by Joseph Inikori in 2002.Footnote 8 However, for decades this research was neglected by historians of London and its institutions.Footnote 9 For instance, in the historiography of the Bank of England (hereafter the Bank), the importance of slavery has, until recently, either been disavowed or sidelined.Footnote 10 Since 2008, innovative research by Nicholas Draper has made important strides towards rectifying this imbalance. He has shown how profits derived from slavery contributed materially to the development of London’s port infrastructure through subscriptions to the West India and London Docks companies, substantiating the argument that the slavery economy was fully integrated into the City’s commercial and financial structure by the turn of the nineteenth century. Draper has also used the 1837–38 Parliamentary Return and the richly detailed records of the Slave Compensation Commission to carry out an analysis of British slave ownership in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, revealing that over 150 London merchants and 30 City banks appear in the Slave Compensation records as both principals and agents.Footnote 11 Subsequent empirical work completed by members of the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery (LBS) at University College London, led by Catherine Hall, has further developed this research on the recipients of slavery compensation in 1835, shedding light on the social depth of slave ownership, the widespread geographical distribution of slave owners across Britain, and the various outlets in which the compensation money was reinvested.Footnote 12

In response to the racial justice protests of 2020—when activists, journalists, and historians drew upon LBS’s online database to force a public reckoning on the history and legacies of British connections to slavery—there has been a flurry of institutional studies interrogating historic links to slavery, including among banks, law firms, insurance markets, and livery companies in London.Footnote 13 In the past four years, these studies have collectively reexamined the City’s business archives, unearthing new and underutilized source material which has helped to deepen our empirical basis for interpreting the depth and extent of the relationship between the City and slavery. That we are entering a new paradigm in our understanding of how embedded the transatlantic slave economy was within the City’s financial sector and business community is perhaps best demonstrated by Maxine Berg and Pat Hudson’s 2023 synthesis of the latest research on slavery and the industrial revolution, which includes an important chapter on London’s financial services industry.Footnote 14 Recent research has heralded the emergence of a new consensus that slavery was a constitutive element in the City’s development as a center of financial capitalism.

This article contributes to this burgeoning literature by exploring how British firms—especially those in the City of London—profited from the unique business opportunity that arose through the payment of compensation to slave owners in 1835–46 by functioning as intermediaries in the collection of awards from the Bank. Draper’s research has revealed how London merchant houses and banks benefitted materially from the compensation process in their capacity as slave owners and mortgagees; in other words, as the principals in compensation awards.Footnote 15 However, the depth and extent of their role as intermediaries in the collection of awards have never been studied systematically.

A new dataset with 18,930 observations—derived from a transcription and analysis of the compensation accounts and stock ledgers in the Bank’s Archive—is deployed in this article to establish that a cohort of 27 “compensation agents” handled approximately two-thirds of the transactions associated with £5 million paid in compensation as government stock (3.5% Reduced Annuities) to slave owners in Barbados, Mauritius, the Cape of Good Hope, and the Virgin Islands. Archival material pertaining to the payment and collection of slavery compensation survives in the Bank’s Archive because the Bank was an integral part of the administrative process that underpinned the compensation scheme. These ledgers and account books have, however, previously been underused by historians studying the nineteenth-century City and slavery compensation.Footnote 16 Analysis of the collective biographies of the compensation agents and their economic behavior has been enriched through research at The National Archives UK in the payment books, correspondence, and minutes of the Slave Compensation Commission and National Debt Office—two government departments involved in the arbitration and payment of compensation claims—as well as in the Parliamentary legislation for slavery compensation, colonial newspapers, the ledgers of the firm Henckell, Du Buisson & Co. at The London Archives, and the UCL Legacies of British Slavery database.

Identifying and analyzing the operations of the “compensation agency business” during the 1830s contributes to our broader understanding of the economic and financial role of transatlantic slavery in British history. It highlights how significant the City’s financial capacity, infrastructure, and business community was in delivering the efficient payment of slavery compensation, and recovers the important intermediary role played by City merchants, bankers, and jobbers in the collection and distribution of compensation awards. It also shows how the financial apparatus of the City—especially the London Stock Exchange—was vital in quickly liquidating the stock used in the compensation process and making it available for reinvestment. These findings help to reinscribe the payment of slavery compensation into the business and financial history of nineteenth-century Britain, where themes of slavery and empire have been neglected.Footnote 17 They also underscore the need to understand the slavery compensation process as contemporaries did: as an important moment in the history of the City and its financial markets.

What follows begins by providing contextual background on the financial and economic dimensions of the compensation scheme, and the administrative process through which claims were adjudicated and paid. This analysis demonstrates how the British state was heavily reliant on private banks in the City to raise the money needed to indemnify slave owners after the abolition of slavery in 1833, and that the Bank was a vital cog in the complex administrative machine tasked with managing the compensation process. This section also explores the local economic, social, environmental, and geographical factors that influenced patterns of slave ownership in the colonies that were paid compensation out of the £5 million in 3.5% Reduced Annuities. In doing so, it highlights the significant place of Mauritius in the southwest Indian Ocean to the history of slavery in the British empire and the compensation process (the island was allocated £2,112,631 in compensation for 68,613 enslaved people), helping to rectify an imbalance in the historiography of British slavery, which is mostly focused on the Caribbean and the Atlantic world.Footnote 18

The second section explores how the City’s financial capacity and the dense web of networks that linked London businesses with slave-based economies across the British empire were vital in facilitating the rapid payment and collection of slavery compensation between 1835 and 1846. It establishes that merchants and bankers in the City, the outports, and the colonies drew upon their preexisting business relationships with slave owners and competed against one another in the compensation agency business, seeking to profit from the business opportunity presented by the moment of compensation. An analysis of the compensation agents’ economic behavior reveals there were three distinct models for the collection of compensation, but that it was large-scale discount operations, usually carried out by City merchants and banks in collaboration with local colonial merchant firms, that was the key to securing a competitive advantage in handling claims. The section ends by considering the factors that explain why so few slave owners traveled to London to collect their compensation awards from the Bank on their “own account.”

The article’s final section demonstrates how compensation that was paid as government stock was quickly sold on the London Stock Exchange. By 1844, almost none was held by those who had collected it, or by those to whom it had been awarded, meaning that compensation awards made in stock were quickly converted into cash. It was sold to jobbers working on the stock exchange, specialists in making a market for people looking to buy and sell stock. As major dealers in government stock, jobbers were therefore another intermediary group in the City who profited from the compensation process. They earned money from the bid-ask spread—the difference between the prices they quoted for the purchase and sale of a particular stock—every time the £5 million in Reduced Annuities created by the compensation legislation was bought and sold.Footnote 19 This analysis of the rapid liquidation of the compensation stock via jobbers sheds new light on how the compensation funds were mobilized for reinvestment in other outlets in Britain and overseas.Footnote 20

Parliament, the City of London, and the Payment of Slavery Compensation

On August 28, 1833, Parliament passed legislation that abolished slavery within the British empire, emancipating more than 760,000 enslaved Africans in the following year. As part of the compromise that helped to secure abolition, the British government agreed on a compensation package for slave owners. A sum of £20 million was allocated and from 1835-46 payments were made to slave owners for the loss of their “property.” Slave owners were also allowed to benefit from an exploitative system of apprenticeship, which saw newly freed men, women, and children continue to labor for their former owners without pay for up to a further six years. Full emancipation was thus only achieved after the end of the apprenticeship system in 1838.Footnote 21

Between 1833 and 1841, six Acts of Parliament were passed concerning the payment of £20 million in slavery compensation.Footnote 22 This was an unprecedented sum to add to the national debt outside of wartime, representing approximately 5 percent of Gross National Product and 40 percent of the Treasury’s annual income from taxation.Footnote 23 The British state was dependent on the financial capacity of the City to raise the money needed to indemnify slaveowners and, as the government’s banker, the Bank helped to administer the compensation funds. Out of a total of £20 million paid in compensation, the government raised £15 million of this sum in cash through a public loan contracted in August 1835 with a syndicate of City bankers and financiers led by Nathan Mayer Rothschild and Moses Montefiore (known to contemporaries as the West India Loan). This was a major financial transaction and was understood at the time to be an important moment in the history of the City. Not since the “Dead-weight annuity” in 1822 had the British government conducted any large-scale public borrowing. Consequently, the West India Loan precipitated enormous excitement in the City; in the spring and summer of 1835, there were regular articles in newspapers such as the Morning Herald speculating on the size of the loan and discussing its impact on the City’s money market.Footnote 24

The outstanding balance of £5 million was found by creating an equivalent value ex nihilo of an existing government stock of £3:10s Reduced Annuities (3.5% Reduced Annuities). Moreover, approximately one-third of the money raised through the West India Loan was invested in another government stock known as 3% Consolidated Annuities (3% Consols).Footnote 25 These funds were used to pay litigated compensation claims that were being formally contested between multiple claimants. Litigated claims arose due to legal challenges by counter-claimants—usually relating to disputes over the priority of mortgages and unpaid purchase money—and were quickly settled by the Compensation Commissioners and disposed of within a brief period. Litigated claims that were subject to preexisting suits in the Court of Chancery and the colonial courts (“List E” claims) were also held in stock, but the protracted legal process meant they took much longer to adjudicate and pay out.

The procedure that led to a compensation award was dependent on complex layers of bureaucracy in both the colonies and the metropole.Footnote 26 The records in the Bank’s Archive underpinning this study were created because the compensation legislation passed by Parliament directed that all compensation awards were to pass through newly created compensation accounts in the books of the Bank. The Bank thus supported the British government in administering the payment of slavery compensation.Footnote 27 As soon as the compensation scheme started paying out in October 1835, slave owners in major Caribbean colonies such as Jamaica and British Guiana promptly began to receive awards in cash raised through the West India Loan. These could be collected as Bank of England notes and were processed by clerks in the Bank’s Cashier’s Office. However, some other colonies were on a slower timetable for compensation. This was because of delays in the ratification of the 1833 Abolition Act by the colonial legislatures in Barbados and the Virgin Islands and the government’s decision to postpone when the provisions of the Act would come into force in Mauritius and the Cape due to their distance from London.Footnote 28 Awards for slave owners in these colonies were thus mediated by the Compensation Commissioners slightly later in 1836–7 and paid out using the £5 million that had recently been created in 3.5% Reduced Annuities. These compensation awards could also be collected by attending the Bank but, unlike awards made in cash, were processed by clerks in the Bank’s Stock Office (a separate department of the Bank) and paid through the transfer of Reduced Annuities to individual stock accounts in the names of those who had collected it. The legislation took account of prevailing market prices and so the nominal value of the stock payments was higher than the actual amounts of the claims.Footnote 29 This ensured that slave owners in Barbados, Mauritius, the Cape, and the Virgin Islands did not receive “unfair” treatment from the government through being paid in stock as opposed to cash.

To analyze the role of City merchants, bankers, and jobbers as intermediaries in the compensation process, this article undertakes a detailed analysis of the £5 million that was paid in 3.5% Reduced Annuities out of the Barbados Compensation Account and the Slave Compensation Account at the Bank.Footnote 30 The creation of the Barbados Compensation Account was directed in legislation passed on August 31, 1835, with a total of £1,734,353 in 3.5% Reduced Annuities allocated as compensation for 82,807 enslaved African people in Barbados.Footnote 31 The Slave Compensation Account is first mentioned in new legislation passed on August 17, 1836, with £3,437,270 invested in the same stock to enable the payment of compensation to owners of enslaved African people in the colonies of Mauritius, the Cape, and the Virgin Islands.Footnote 32 Approximately £2,112,631 of this sum was allocated to Mauritius in compensation for 68,613 enslaved, £1,247,401 to the Cape for 38,427 enslaved, and £72,940 to the Virgin Islands for 5,192 enslaved.Footnote 33

Both accounts were opened in the books of the Bank with credit payments matching the sums specified in the legislation exactly, and debits rapidly began flowing out of the accounts as compensation payments. By July 1836, just three months after the Barbados Account was first opened, over 90 percent of the Reduced Annuities had been withdrawn. Payments were made from the Slave Compensation Account on a slightly slower timescale: after 10 months, in August 1837, 50 percent of the total value had been paid out. Awards contested by counter-claimants were held in trust in separate “litigated” compensation accounts. These litigated accounts appear in the Bank’s stock ledgers in the name of the Accountant General of the Court of Chancery.Footnote 34

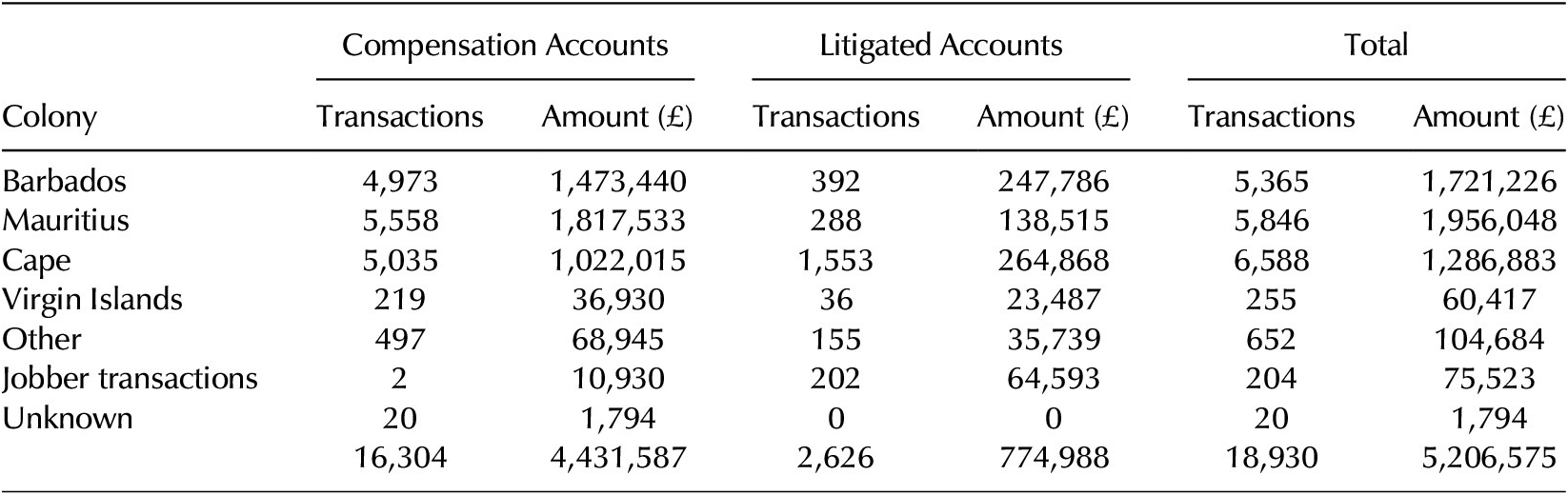

The monetary value in the Barbados Compensation Account and Slave Compensation Account constitutes the entirety of the £5 million allocated in 3.5% Reduced Annuities. We have transcribed the two accounts in full and, for completeness, have also transcribed the associated litigated accounts (see Table 1).Footnote 35 These four accounts are shown as entirely separate in the Bank’s books, but for ease of analysis and brevity of discussion, we have undertaken some aggregation in our results.

Table 1. 3.5% Reduced Annuities compensation accounts managed by the Bank of England

Source: TNA, NDO 4/32, pp. 341–348, “An Act to carry into further Execution …,” August 31, 1835; TNA, NDO 4/32, pp. 877–883, “An Act … for completing the full Payment of such Compensation,” August 17, 1836; BoE, AC27/7297, f. 4130½ & AC27/7306, f. 4213½.

Our dataset contains 18,930 transactions totaling £5,206,575, with 799 unique account names collecting compensation awards in 3.5% Reduced Annuities. Table 2 shows the breakdown of these data by colony. More stock was paid out of the accounts by value than the £5 million that had originally been allocated in the legislation. This is because, beginning from the date of emancipation, compensation awards accumulated interest, and the stock that was collected from the Bank comprised both the principal award and interest.Footnote 36 The higher value is also explained by the fact the Slave Compensation Account underwent a major operational change on December 23, 1837, when new legislation was passed that enabled compensation payments to be withdrawn from the Account to compensate owners of enslaved African people in any colony. By late 1837 the Compensation Commissioners were running out of the £15 million in cash raised through the West India Loan, and to expedite the completion of the compensation process the government decided to allow payment of the remaining awards in government stock using the Slave Compensation Account.Footnote 37 These are included in the “other” colony category: roughly half of that total of £104,684 was for slave owners in Jamaica.Footnote 38 The jobber transactions are almost entirely related to stock market activity undertaken for the Accountant General by his broker. Finally, there are 20 “unknown” transactions worth £1,794 which we have not yet been able to associate with a specific colony.

Table 2. Breakdown of the £5 million paid in 3.5% Reduced Annuities by colony

Source: BoE, AC27/7297, ff. 4130–4185; AC27/7306, ff. 4213–4292, 4197–4209.

Variations in these data are explained by local economic, social, environmental, and geographical factors in the colonies, which influenced patterns of slave ownership. Mauritius and Barbados, two islands with a tropical climate conducive to plantation agriculture based around sugar and coffee production, received the bulk of the compensation paid in Reduced Annuities because large-scale plantation economies required the labor of thousands of enslaved African people. There were 5,365 compensation awards paid out of the accounts for 82,807 enslaved people in Barbados, and 5,846 awards for 68,613 people enslaved in Mauritius. The Virgin Islands was also developed as a plantation economy by the British but, as an archipelago in the Caribbean Sea consisting of 50 small islands, sugar production was always marginal in this colony and concentrated in Tortola and the other main islands. The small island geography of the Virgin Islands therefore shaped the pattern of small-scale slave ownership there, with 5,192 African people enslaved in the colony at the time of abolition. This explains why there were only 255 awards withdrawn from the compensation accounts that pertain to the Virgin Islands.Footnote 39

Unlike the other colonies that received compensation awards in government stock, the Cape did not have a large-scale plantation economy. This was due to climatic and environmental factors which meant that southern Africa was not a favorable location for the cultivation of tropical commodities. The Cape was instead a settler colony with an economy geared towards the widespread use of enslaved workers in commercial wheat farming, wine cultivation, and ranching. The mixed economy of the Cape resulted in a more diffuse pattern of slave ownership, with small numbers of enslaved people spread across multiple different owners.Footnote 40 The considerable number of different individuals in the Cape who claimed compensation for small numbers of enslaved people helps to explain the distinctive features of the compensation awards made for the Cape. For example, the large numbers of small-scale slave owners, each of whom would have submitted a unique compensation claim, clarifies why the Cape is the colony with the greatest number of transactions (6,588) withdrawn from the Bank’s compensation accounts for Reduced Annuities, despite the total number of people enslaved in this colony (38,427) being far fewer than Barbados or Mauritius. It is also notable how there are significantly more contested compensation claims for the Cape when compared to the other colonies: 24 percent of claims for the Cape were contested and paid out of a litigated account, compared to just 7 percent for Barbados, 5 percent for Mauritius, and 14 percent for the Virgin Islands. This is probably also explained by the diffuse pattern of slave ownership and the use of enslaved workers in a variety of different occupations in the Cape’s mixed economy, which gave rise to a situation where it was more frequent for different individuals to claim a legal interest in the same groups of enslaved people, leading to a greater number of contested compensation claims that were ultimately paid out of a litigated account.

The mean of an individual transaction was £272, but this hides a wide spread of values. Nearly 90 percent of all awards were less than £500 and around half were less than £100, suggesting there were many small-scale slave owners resident in these colonies.Footnote 41 At the other end of the scale, there were some large individual transactions, with 89 awards over £5,000 that went mostly to owners of substantial plantations. On August 23, 1837, Archibald William Blane collected the largest single compensation award made in Reduced Annuities (worth £14,466) as the attorney of Charles Millien for the 474 people he enslaved on a plantation in Mauritius.Footnote 42 Almost all the individual awards over £5,000 are for compensation awarded to Mauritian and Barbadian slave owners: there are none relating to the Cape, and just one for the Virgin Islands. This again largely reflects local patterns in the structure of slaveholding in the colonies covered by the accounts. To reiterate, slave ownership in the Cape was widespread but small-scale, whereas, in Mauritius and Barbados, the general tendency was for the enslaved to be concentrated on larger agricultural units geared towards the production of cash crops, causing a greater frequency of single compensation awards with a high value. Also important was the decision made by the Compensation Commissioners to divide the £20 million unequally across the various colonies according to differing local economic conditions. An individual enslaved person in the newer and more productive plantation colonies like Guiana, Trinidad, and Mauritius was thus accorded a higher value when compared to the older colonies such as Barbados and Jamaica where economic productivity was lower due to soil exhaustion. The fact that according to the “inter-colonial apportionment” drawn up by the Compensation Commissioners in July 1835, the average value of an individual enslaved person in Mauritius was calculated at £69 14s 3d compared to £47 1s 3½d in Barbados meant the largest compensation awards collected from the accounts were far more likely to relate to Mauritius than elsewhere.Footnote 43

The Compensation Agents

Our results show there are 799 account names in the Bank’s ledgers for 3.5% Reduced Annuities, the majority of whom were individuals collecting compensation awards in the capacity of agent.Footnote 44 Table 3 groups the individual accounts by number of transactions and summarizes the total payments. The most striking feature is that there are 10 individuals who each handled over 500 transactions. Their 9,679 transactions amounted to £2.49 million, nearly half of the total value in the accounts. There are also 17 individuals who each collected between 100 and 499 transactions: 4,064 transactions in total worth nearly £1.1 million. These 27 large compensation agents—who together handled 13,743 transactions worth nearly £3.6 million or two-thirds of the total value in the accounts—all appear to have been partners (often junior partners) in banks and merchant houses that had longstanding financial and commercial ties with at least one of the colonies awarded compensation in government stock. For instance, Robert Barclay Jr., junior partner in his father’s Mauritian sugar trading business Barclay Brothers & Co., was the largest individual agent by value, collecting £516,831.Footnote 45

Table 3. Account names arranged into cohorts by number of transactions

Source: BoE, AC27/7297, ff. 4130–4185; AC27/7306, ff. 4213–4292, 4197–4209.

The key role played by the City’s merchant and banking firms in the collection of slavery compensation resulted from Parliament’s decision to adjudicate and pay all awards in London, rather than in the colonies. That choice favored slave owners based in Britain and was therefore probably a political concession to the West India Interest, a powerful lobby of absentee planters and merchants that had resisted emancipation and campaigned in favor of compensation.Footnote 46 Yet Parliament’s decision posed a problem for the tens of thousands of resident slave owners living overseas in the Caribbean, Mauritius, and the Cape. There was a high transaction cost for resident slave owners to make the expensive and lengthy journey to London to collect their compensation. Moreover, for awards made through a transfer of government stock, there was the added complication that some slave owners who lived overseas would have had limited knowledge of how the London stock market operated and thus how they could convert their stock into cash using a broker and collect their dividends (which had to be done at the Bank).

Consequently, because it was necessary for someone to physically collect compensation payments by attending the Bank, market forces determined that resident slave owners regularly gave merchants and bankers legal authorization to collect their compensation. Some merchant houses and banks collected large numbers of awards in aggregate and therefore made major profits through commission, discount, and lending activities associated with the compensation agency business. The widespread role of agents in the collection of awards does not seem to have been anticipated by the politicians in Parliament who had designed the scheme for compensated emancipation. It is not mentioned in the compensation legislation, and the government’s decision to print thousands of standardized pro forma for powers of attorney and distribute them widely in Britain and the colonies was made after the compensation scheme opened in October 1835.Footnote 47

Table 4 presents the 27 largest individual compensation agents with more than 100 transactions, as well as a joint account in the names of the Cape Town wine merchants Roelof Abraham Zeederberg Jr. and Robert Eagar that also falls into the category of collecting more than 100 awards. There is a general trend towards specialization among the large agents, with 21 collecting compensation for slave owners in just one colony. This suggests the largest compensation agents tended to specialize in collecting compensation for colonies with which they had preexisting connections. This is because longstanding business and personal networks with colonial merchants and planters provided some City merchant houses and banks with immediate access to a slave-owning client base, giving them a competitive advantage in the market for handling compensation awards. The exceptions that prove the rule are David Charles Guthrie and Sir John Rae Reid, both of whom were partners in major London-based merchant firms—Chalmers, Guthrie & Co. and Reid, Irving & Co.—that had general overseas business interests. Their extensive commercial networks connected them to slave owners and colonial merchants across multiple colonies, even those that were geographically far apart (e.g., David Charles Guthrie who handled awards for both Barbados and the Cape).

Table 4. Specialization of the “large compensation agents” by colony

Source: BoE, AC27/7297, ff. 4130–4185; AC27/7306, ff. 4213–4292, 4197–4209.

Some of the large compensation agents also had family members or business partners who served in colonial administration or the local compensation commissions in the colonies; administrative bodies tasked with determining the number of enslaved people to which slaveholders and mortgagees had a legal claim. This would have given these merchants an added advantage in the compensation agency business, as it provided opportunities to expand their client base by facilitating close and regular contact with the slave owners submitting compensation claims. For example, James Blyth was a merchant in Mauritius who served on the local compensation commission adjudicating claims for that colony in the mid-1830s, while his brother and business partner Henry David Blyth was based in London and appears as a large agent in our analysis, handling 1,302 compensation awards worth £336,898 on behalf of Mauritian planters.Footnote 48

The large agents’ extensive commercial and financial interests in the Caribbean, Mauritius, and the Cape in the years prior to emancipation meant they often had a direct stake in slave ownership, either as mortgagees or owners. It was most common for the large agents to appear in the compensation records as principals for awards of small value. For instance, John Price Simpson was part of the merchant house Simpson Brothers & Co., which had headquarters in London and the Cape. Simpson collected 696 claims worth £137,799 for Cape slave owners. He was also a direct beneficiary of the compensation process as a small-scale awardee for seven enslaved people he owned in the Cape and, like other wine merchants based in the Cape, his firm was a creditor of slave owners and held several mortgages secured on enslaved people.Footnote 49 A select group of compensation agents—Thomas Lee, John Daniel, John Watson Borradaile, Sir John Rae Reid, John Irving Jr., and George Reid—had a more substantial direct interest in slave ownership than was typical, and they appear in the compensation records as large-scale awardees. This was because their merchant and banking firms had extensive and longstanding involvement in plantation finance in the Caribbean. Consequently, they claimed compensation as principals, either because they held mortgages secured on plantations and enslaved African people or because they had already come into possession of Caribbean estates after slave owners had defaulted on their loans. For example, Sir John Rae Reid collected 936 awards in 3.5% Reduced Annuities worth £310,633 for Mauritius, the Virgin Islands, and Jamaica. With the other partners in Reid, Irving & Co., he was also the direct recipient of £17,894 in compensation for the six plantations and 1,229 enslaved African people his firm owned in the Virgin Islands. Reid was also successful in securing compensation for his other slaveholding interests as a mortgagee and owner in Jamaica, St. Kitts, Trinidad, and British Guiana.Footnote 50

The records reveal that agents used three different models for the collection of compensation. First, was an “agency” model, where slave owners issued powers of attorney to a merchant firm, a partner in the company attended the Bank in the capacity of compensation agent to collect the award and then posted the cash balance to the slave owner’s account in their own firm’s ledgers, minus a commission charge. The proceeds of the award were then remitted to the slave owner, either in specie or through a bill of exchange. Second, was an “advance” model, where a merchant firm advanced the full value of the award to the slave owner at interest (with the power of attorney enabling the collection of the compensation award functioning as security), before arranging for the collection of the stock from the Bank. The merchant then kept the award money and benefitted from the accumulated interest on these advances. Third, was a “discount” model, which involved a merchant house buying up the entitlement to compensation claims by immediately giving a slave owner cash or merchandise equal to the value of their award minus a discount (the commission fee). They then used the power of attorney to collect the compensation at the Bank and kept the proceeds of the award for themselves.

The evidence suggests the “advance” and “discount” models were those used most frequently by the large compensation agents. The large agents therefore often purchased as principals the entitlement to compensation awards, meaning that rather than performing a straightforward agency role they were acting in more of an entrepreneurial fashion. A precondition for carrying out this business strategy on a substantial scale was that the merchant house required the financial capacity necessary to either quickly buy up large numbers of awards or have significant sums out in advance for several months. Those who implemented these strategies successfully were thus most commonly colonial merchants or the factors of British merchant houses who were able to draw upon the extensive financial resources of London-based merchants and bankers (either because they were partners in the same firm or had an existing business relationship). The large London-based compensation agents and their collaborators in the colonies quickly recognized that buying up the entitlement to collect large numbers of compensation awards was the most effective way to outcompete other firms and corner the market. The numerous advertisements published in colonial newspapers by merchant firms—through which they sought to publicize to prospective slave-owning clients the services they offered in collecting compensation—stand as a testament to the competitive market the larger agents were operating in. On December 5, 1835, there were four such notices published in the Barbados Mercury and Bridgetown Gazette, while on June 10, 1836, there were eight notices posted by different firms in the Cape of Good Hope Government Gazette. Footnote 51

Commercial networks linking local merchants in the colonies with merchant houses and banks in the City were crucial in securing a competitive advantage in the compensation agency business. The local merchant in a colonial port town gathered slave-owning clients with outstanding compensation claims and oversaw the completion of the powers of attorney, while the City firm provided the financial resources needed to utilize the “discount” and “advance” models and arranged for the final collection of the award from the Bank. A good example is the Bridgetown merchant house E. B. & J. B. Haly, which was the first business in Barbados to identify that handling compensation awards was a unique and profitable opportunity. They posted an advertisement in the Bridgetown Gazette on August 25, 1835 (just ten days after news first reached Barbados from London about how the compensation process would work) explaining that they were willing to “undertake through their Agents at London to collect claims on the [compensation] Fund, and will account to the parties who may favor them with such business, either at that City or in this Colony.” They also highlighted how, following the completion of the relevant powers of attorney, “advances in Merchandize will be made to Claimants.”Footnote 52

The London agent mentioned in Haly’s advertisement was the commission merchandising firm Chalmers, Guthrie & Co., based in the City at 9 Idol Lane. On December 18, 1835, David Charles Guthrie, the sole surviving partner in the firm, wrote to the Compensation Commissioners to complain about what he thought was a major delay in the adjudication of claims. His desire for urgency was because his merchant house currently held 200 compensation claims worth £18,642 for Barbados. Guthrie’s correspondents in the colony (the Haly firm) had drawn bills upon Chalmers & Guthrie “for a great part” and requested that specie be sent to Barbados to “replace immediately the funds they have advanced to claimants.” Guthrie was reluctant to accept the bills and ship the money until he had received assurances that the claims would be awarded and paid by the government in a timely manner.Footnote 53 The Barbados Compensation Account did not begin paying out until April 1836, meaning E. B. & J. B. Haly’s risk-taking strategy to gain a competitive advantage in the market for handling compensation claims caused them to lie under heavy advances to Barbadian planters for up to nine months. Overall, David Charles Guthrie handled 712 compensation awards worth £139,328 for awardees in both Barbados and the Cape.

John Montefiore & Co., a Barbadian merchant house specializing in the sale of consumer goods to planters and the provision of shipping services, also provided both “discount” and “advance” services for the collection of compensation. The firm published a notice in the Barbados Mercury on October 10, 1835, to “beg to inform all concerned that they continue to make advances on the Compensation Claims, or to buy out the interest of parties disposed to sell.”Footnote 54 This advertising strategy was clearly successful—John Montefiore collected 392 awards worth £35,659—although these numbers and the fact he traveled to London himself to collect the awards from the Bank suggest he was not working in partnership with a City merchant house or bank, meaning he only had the financial capacity to handle the claims of small-scale slave owners with low-value awards. In contrast, Thomas Lee, senior partner in the Liverpool and Bridgetown merchant house Thomas Lee, Haynes & Co., collected 447 awards that were worth the much larger sum of £189,105. Lee’s ability to handle high-value awards was because his West India commission merchandising firm had the financial resources to make larger advances and was already connected to substantial planters in Barbadian society (also explaining why he did not feel the need to advertise his services in Barbadian newspapers). For instance, in a letter to the Compensation Commissioners dated January 23, 1836, Thomas Lee mentioned that his merchant house was already “the holders of upwards of two hundred powers of attorney for the collection of compensation money for various proprietors in Barbados, and that we were under heavy advances to many of them.”Footnote 55

Large agents specializing in the collection of compensation for the Cape of Good Hope and Mauritius adopted the same business strategies as their counterparts in Barbados. The Cape Town wine merchants R. A. Zeederberg Senior and Home, Eagar, & Co. directly addressed “CLAIMANTS ON COMPENSATION” in their advertisement published in the Cape of Good Hope Government Gazette on June 10, 1836, detailing how the junior partners in their firms were “intending shortly to proceed to England” and therefore “offer[ed] their services to those having Claims for Compensation Money, to receive the amounts due to them, and transmit them to the colony.” Besides offering a straightforward agency service, they also proposed to “make fair advances to any who may require it.”Footnote 56 Their advertising efforts were successful. Roelof Abraham Zeederberg Jr. and Robert Eagar collected 491 awards as joint partners, drawing £143,097 from the compensation stock accounts. They also collected significant sums when not working in partnership: Robert Eagar, for instance, was involved in 509 transactions by himself worth £138,585. The Mauritian merchant house Thomas Blyth, Sons & Co. also used the “advance” and “discount” models. Amid the rush to secure the business of handling compensation claims for Mauritian slave owners in the mid-1830s, the firm’s representative in Mauritius James Blyth wrote to his brother Henry David Blyth in London to ask him to send hard cash in a fast-sailing vessel. This would allow their company to make immediate advances in specie to slave owners and thereby secure a competitive advantage in the compensation agency business over other island firms, who were only able to offer advances in commodity currencies such as sugar and coffee which was less desirable for planters.Footnote 57

The merchant Thomas Du Buisson—who collected 141 compensation awards in stock worth £65,685 for Mauritius between November 1836 and August 1842—was a partner in the merchant house Henckell, Du Buisson & Co., based at 18 Laurence Pountney Lane in the City. The firm’s ledgers survive at The London Archives for the period 1831–40, enabling detailed analysis of a large compensation agent’s behavior.Footnote 58 Du Buisson was a merchant of Huguenot extraction, who by 1790 had formed a business partnership with his brother-in-law James Henckell. Henckell had owned the lease to Adkins mill in Wandsworth, London since 1777, which he redeveloped as an iron manufactory, increasing its productive output through water engineering works. Henckell & Du Buisson profited from contracts to supply the government with heavy ordnance during the Napoleonic Wars and from the sale of wrought iron products to domestic and colonial markets.Footnote 59 By the 1830s, Du Buisson was the sole surviving partner in the firm, and, rather than ironmongery, the firm now specialized in commission merchandising and the provision of marine insurance and other shipping services to British and French merchants involved in Eastern trade. It was because Du Buisson was based in the City and had preexisting commercial networks linking him with colonial merchants based in Mauritius that he became involved in the compensation agency business.

All three models for the collection of compensation appear in the ledgers of Henckell & Du Buisson. Beginning in 1836, new accounts were opened in the names of slave-owning clients receiving compensation awards. It is common to see three separate entries on the credit side of the slave owners’ accounts in the ledgers: the principal compensation award, the accumulated interest, and the half-yearly dividends on the 3.5 percent stock. All these transactions were credited “by cash,” reflecting the fact that the stock had been sold to jobbers and converted into cash by Du Buisson before being posted to the slave owner’s account. On the debit side of the slave owner’s account in the ledgers, there are commonly two entries: the commission fee and the transaction remitting the remainder of the compensation award to the slave owner either in cash or using a bill of exchange. The standard commission fee charged by Du Buisson for the collection of compensation awards was 7 percent. The largest single sum Du Buisson generated through commission was £581 15s 7d for collecting Paul Froberville’s compensation award worth £8,250 12s 9d for the 252 people he enslaved in Mauritius.Footnote 60 The money taken “for commission and charges” was reinvested directly into the general stock of the company, helping to finance its future operations.

The ledgers show how discount activities underpinned Du Buisson’s “success” in the compensation agency business. 85 percent of the awards he handled were through his role as a London partner for five different merchant firms in Mauritius that were buying up compensation awards at a discount.Footnote 61 The Port Louis merchant houses P. Froberville, Griffiths & Co., and R. Plantin & Co., with whom Du Buisson had a longstanding commercial relationship in shipping and marine insurance, were his main collaborators in the compensation agency business, assigning him 40 and 29 awards, respectively. In such cases, the 7 percent commission fee was shared equally (3.5 percent each) between the two firms, and the proceeds of the compensation award would be transferred to the Mauritian merchant’s business account within Henckell & Du Buisson’s ledgers. Overall, Henckell & Du Buisson generated modest profits in the range of £2,298—£4,598 from the compensation agency business: a valuable side-earner for this firm.

In general, profits from handling compensation claims—through either commission, discount, or interest on advances—fell within the range of 2–10 percent and varied depending on the terms set by the merchant house or bank, the colony, and the model for collection used.Footnote 62 The lower end of this range tends to only appear in the sources when the commission fee for collecting compensation was divided between a colonial merchant house and a City firm. The largest agents made substantial profits from the compensation agency business due to the large number of transactions they were involved with in aggregate. For instance, Henry David Blyth, a partner in the Mauritian sugar trading firm Thomas Blyth, Sons & Co. and one of the most prolific compensation agents, collected 1,302 awards worth £336,898 on behalf of Mauritian planters, which generated profits worth £25,000 in commission fees (equivalent to 7.4 percent).Footnote 63

Some colonial administrators viewed the discount and advance activities of the large agents as an exploitative strategy, which predatory merchants were using to take advantage of small-scale slave owners at a time when they were especially vulnerable due to the social and economic dislocation caused by emancipation. For example, the Lieutenant-Governor of Guiana published an official notice in November 1835 expressing concern that “extensive purchases have been made…of the Claims of individuals entitled to participate in the Compensation Fund,” and that by “availing themselves of the ignorance and unfounded alarm of the smaller and poorer proprietors” some merchant firms had “in many instances bought up such Claims at a most enormous discount.”Footnote 64 Similar comments were made regarding other colonies, including the Cape and Mauritius, where a discourse became firmly embedded that slavery compensation benefitted only British merchants due to their role as mortgagees and their profiteering from discount operations. High transaction costs resulting from the government’s decision to pay compensation in London and asymmetric knowledge between merchants and resident planters about how the compensation process worked had created a business opportunity that mercantile intermediaries were exploiting for profit by buying up compensation claims at a steep discount. In the pressured and uncertain context of emancipation in the mid-1830s, it appears resident slave owners’ economic behavior was shaped by their anxiety to receive cash or commodity currency immediately via the “discount” model, rather than waiting for months to obtain the proceeds of their compensation award through the “agency” model (despite the possibility that this might save on commission fees). Further research is needed to determine the extent to which the decision taken by many resident slave owners to sell their awards at a discount to compensation agents led to worse economic and social outcomes over the long term when compared to those slave owners who opted for the “agency” model or had the capacity to travel to London to collect their awards themselves.

There are also 334 middle-ranking compensation agents in Table 3 (above) who each handled between 2 and 99 compensation awards. These middle-ranking agents were together involved in 4,043 transactions worth £1,184,325. This cohort includes some major bankers, merchants, and insurance brokers such as Thomas Baring (29 awards for Mauritius worth £14,324), Walter Hawkins (42 awards for the Cape worth £7,881), and Hananel De Castro (68 awards for Barbados worth £5,249). Unlike those in the category of large compensation agents, who were exclusively merchants and bankers, there were other types of professionals who collected between 2 and 99 awards, including accountants, lawyers, medical doctors, reverends, army and naval agents, and planters. While most people in this cohort were not major competitors in the market for handling compensation awards as agents, it is still likely that many of these professionals charged commission fees for providing an agency service.

The diversity in the occupations and social backgrounds of the middle-ranking agents underscores how there was social depth to involvement in the compensation agency business. This is best demonstrated by the seven women who appear as compensation agents in this cohort. Important research has been completed in recent years on the role of women as slave owners in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, meaning it was not entirely surprising to discover instances of women attending the Bank to collect slavery compensation.Footnote 65 Take Elizabeth Christina Rowles “of Cape Town,” for example, who in 1837 traveled from southern Africa to London to collect 14 compensation awards worth £4,422 between July 25 and August 3, 1837. She collected a further five claims totaling £958 from the litigated account the following year. Rowles was herself a small-scale slave owner in the Cape and an awardee of compensation for four enslaved people, and thus some of the awards she collected were for herself as principal.Footnote 66

Finally, 341 unique individuals appear fleetingly in the Bank’s compensation accounts because they were involved in just a single transaction. Collectively, they withdrew £118,679 in compensation awards. We originally hypothesized these were most likely slave owners who collected their compensation as principals. However, the majority were performing an agency function on behalf of slave-owning clients. Unlike the compensation agents who handled large numbers of claims, it is evident that the 341 small agents involved in the collection of just a single compensation award as an attorney were not competing in the compensation agency business and seeking to profit via commission fees. Instead, they were most likely carrying out a legal function as a trustee or executor or performing a favor for a family member, friend, or business associate. For instance, on January 6, 1836, William Alleyne Culpepper wrote to the Compensation Commissioners requesting a power of attorney so that he could collect an award on behalf of Henry Sealy of Barbados, who was “at present riding in Madeira [and therefore] requested me to receive the Compensation to which he is intitled.” On May 21, a little over four months later, Culpepper collected Sealy’s award from the Bank as an agent, the only occasion he appears in the Bank’s compensation accounts.Footnote 67

Our analysis thus shows that for the £5 million of compensation paid in Reduced Annuities, most slave owners relied on the services of compensation agents in the City to collect their awards from the Bank, irrespective of whether they were large or small slave owners, resident in the colonies or living in Britain as absentees. Very few slave owners in Barbados, Mauritius, the Cape, and the Virgin Islands collected their own compensation. For the uncontested awards paid out of the “standard” compensation accounts, there are only 193 transactions (1.2 percent of the total) worth £187,566 (4.2 percent of the total) that were collected by a principal on their “own account.” The same pattern is present in the contested awards paid out of the litigated accounts. A little over half of the own account collections for uncontested awards pertain to Barbados (101 transactions). This likely reflects the higher rates of absenteeism among Barbadian planters when compared to the predominantly resident slave owners in Mauritius and the Cape. It would have been more convenient for Barbadian proprietors who already lived in Britain to collect their compensation from the Bank. Even still, what the quantitative evidence for the low frequency of own account collection suggests is that traveling to London for the sole purpose of collecting compensation was, on the whole, an inconvenience for many absentee planters living a rentier lifestyle in regional areas of Britain, especially if they already had a longstanding business relationship in the sugar trade with a London banker or merchant who could easily collect compensation awards for them.

There is a considerable spread in the value of the awards being collected by principals on their own account: the largest sum was £8,622 and the smallest just £1. Nevertheless, one-quarter of these own account collections were for sums greater than £1,000, and a key principle underlying the decision of some large slave owners to collect their own compensation awards was to avoid paying commission fees to an agent. This rationale was articulated by William Hinds Prescod, the largest slave owner in Barbados in the 1830s, who wrote to the Compensation Commissioners in Whitehall in March 1836 to explain his desire to collect his compensation personally because he was “anxious to save the large amount I shall have to pay (if it be received by my usual agents) by way of commission.”Footnote 68 The Liverpool merchant and Barbadian plantation owner Richard Haynes expressed similar concerns in a letter of February 23, 1836, explaining how he wanted his compensation awards to “pass through as few hands as possible to avoid all unnecessary charges for commissions.” Haynes ended up adopting this approach. Three months later, on May 19, 1836, he appears in the Bank’s ledgers collecting all four of his compensation awards on his own account, including £5,005 for the 221 African people he enslaved on the New Castle estate and £2,281 for 95 enslaved people on the Bissex Hill plantation in Barbados.Footnote 69

While this article’s focus is on compensation paid in government stock, preliminary analysis of the National Debt Office payment books at the UK National Archives shows that own account collection was also minimal in colonies that were paid in cash raised through the West India Loan. This means our findings about the role and importance of compensation agents almost certainly hold across the entire process. For example, despite having a high proportion of absentee planters, in Guiana, we estimate that over 90 percent of awards were collected by agents. The same pattern prevails in Grenada, while for St Lucia the figure is over 98 percent.Footnote 70 Indeed, as well as collecting awards for Mauritius that were paid in stock, Thomas Du Buisson also collaborated with local merchants in St Lucia to collect 39 cash awards for that island worth £15,429, suggesting that he specialized in handling the compensation claims of Francophone slave owners in these two former French colonies.Footnote 71 That London-based agents were active in collecting awards paid in cash as well as stock should not be a surprise given that the same issues of transaction costs, geography, and asymmetric knowledge also applied to slave owners in these colonies.

Jobbers and the London Stock Exchange

Ultimately, very few people who collected compensation awards paid in Reduced Annuities held onto the stock for long periods, nor was it common for them to transfer ownership of the stock to their slave-owning clients. There are just 36 account names who received slavery compensation paid in 3.5% Reduced Annuities and still held investments in this stock when it was converted to New 3.25% Annuities in 1844. The value of the remaining investments held by these account names in the stock was small, with just £66,151 being converted into New 3.25% Annuities in 1844, which is less than 1 percent of the total conversion of £66,883,844.Footnote 72 Everyone else sold off the stock they had received as compensation awards remarkably quickly.

At first glance, the decision to immediately liquidate compensation awards paid in government stock is surprising. Wealthy slave owners (both resident and absentee) and West India merchants were heavily invested in the British stock market during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and were therefore familiar with the steady returns and low risk involved with owning government stock. For example, in 1764–67 Edwin Lascelles held £27,900 of 3% Consols, and between 1792–98 Henry Dawkins and Samuel Long jointly owned £45,000 in the same stock.Footnote 73 The reason why compensation awards made in Reduced Annuities were quickly converted into cash presumably reflects a desire for immediate liquidity, among both the slave owners who were the principals and the merchants and bankers acting as their agents. In the crisis years following emancipation slave owners were not looking for long-term investments in the stock market, but instead urgently required working capital to keep their plantations in operation through the purchase of indentured labor and the settling of debts with creditors. City merchants and bankers acting as compensation agents would have also needed cash, especially if they had made heavy use of the “discount” model and had to cover their advances to slave owners and colonial merchants. Moreover, the interest rate gap between Britain and the colonies (interest rates in the Caribbean generally fluctuated between 5 and 8 percent) would have allowed merchants to make greater returns by loaning capital out in the colonies when compared to having large sums locked up in stock with a 3.5 percent yield.Footnote 74 Converting the government stock into cash also mobilized the capital for reinvestment in other outlets in both Britain and overseas which offered returns far exceeding that of 3.5 percent stock, such as the boom in British railway company shares in 1835–36 and loans to the U.S state.Footnote 75 Significantly, the rapid liquidation of the compensation stock, and the profits generated through commission by compensation agents, made funds available for reinvestment into settler colonial enterprise, contributing to a broader imperial restructure in 1832–38, which saw a renewed surge of colonial expansion away from the Caribbean and towards the Australian colonies and New Zealand.Footnote 76

Networks within the City’s square mile that linked merchants and bankers with jobbers working on the London Stock Exchange were vital to the mobilization of the slavery compensation awarded as stock. The most widespread practice was for compensation agents to sell the stock on the open market to jobbers within a couple of days of collection. Jobbers were a small group on the stock exchange who specialized in making a market for brokers and agents looking to buy and sell stock on behalf of the public. As market-makers, jobbers profited from the bid-ask spread: the difference between the prices they quoted for the purchase and sale of a particular stock.Footnote 77 The slavery compensation process created £5 million in new 3.5% Reduced Annuities, which our analysis shows quickly entered the open market by passing through jobbers’ account books. This means jobbers were another group in the City who profited from the compensation process as intermediaries. The jobber John Francis Maubert purchased and sold a significant amount of the new Reduced Annuities awarded as slavery compensation. In May 1836, the peak month for withdrawals from the Barbados Compensation Account with £842,114 paid out, Maubert purchased £374,378 of this new stock (44.5 percent of the total). In August 1837, the peak month for payments out of the Slave Compensation Account, Maubert purchased £116,162 of the new stock (28.6 percent of the total of £406,781).Footnote 78

Maubert’s jobber’s account shows there were clearly “business as usual” transactions that continued throughout the years when compensation was being paid. But it is also evident that the business of buying and selling the new stock created through the compensation process stimulated market activity for jobbers who dealt in Reduced Annuities, and would consequently have increased their profits. For instance, in 1835, before compensation in government stock had begun to be paid, Maubert’s yearly purchases of 3.5% Reduced Annuities stood at £817,000. From 1836–37, the busiest years for the withdrawal of awards from the Bank’s compensation stock accounts, his annual purchases more than doubled to £1.91 million in 1836 and £1.72 million in 1837. Maubert’s market activity in the stock remained high in 1838 with £1.3 million purchased, before decreasing to the more typical annual sum of £532,000 in 1839 once the bulk of slavery compensation awards had been collected.Footnote 79 Andrew Odlyzko has calculated that the bid-ask spread for jobbers trading in Reduced Annuities between 1845–53 was typically between £0.125 and £0.25 and that, over this period, there was an annual turnover of £22 million in Consolidated Annuities—the largest British government stock—generating gross profits of £25,000 collectively for jobbers.Footnote 80 This suggests that when the newly created £5 million in slavery compensation was bought and sold on the London Stock Exchange for the first time it would have generated between £6,500 and £13,000 collectively for jobbers, and further profits every time this stock was bought and sold in the future. When placed into context using Odlyzko’s figures, these profits were clearly not insignificant for jobbers.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the compensation ledgers in the Bank’s Archive sheds new light on the City’s role in delivering the payment of slavery compensation. It underscores how the moment of compensation—especially the period 1835–38 when the West India Loan was raised and the bulk of the awards were paid—was significant in the history of the City and its business community. The City’s financial and administrative capacity shaped the distinctive approach Britain took to compensated emancipation.Footnote 81 Parliament drew upon the City’s financial resources to raise the West India Loan in 1835–36, relying on a private syndicate of City bankers to source the £15 million in cash needed to indemnify slave owners. The government also instructed the Bank—a major City institution—to administer the final stages of the payment process; every slave owner (or their agent) had to attend either the Bank’s Cashier’s Office or Stock Office to collect their compensation award.

What the British government does not seem to have fully anticipated, however, was how important intermediaries in the City would be in the collection and distribution of compensation awards. Merchants and bankers in the City, the outports, and the colonies observed that there was a high transaction cost for slave owners to travel to the Bank to collect their awards and therefore sought to profit from the unique business opportunity arising from the moment of compensation. The largest compensation agents were partners in major City banks and merchant firms. They cornered the market in handling compensation claims by collaborating with colonial merchant houses and using their financial resources to carry out extensive discount operations. The large agents also secured a competitive advantage in the compensation agency business by drawing upon their existing networks with resident slave owners in the colonies and absentees in Britain and, in the case of awards made in government stock, exploited the asymmetric knowledge between principal and agent about how the London stock market worked. The large number of transactions some of the major compensation agents were involved with in aggregate allowed several individuals and firms to realize substantial profits, highlighting how transatlantic slavery needs to be integrated more firmly into the historiography of business and financial history in nineteenth-century Britain.

The scale of the £20 million paid as slavery compensation and the fact it was disposed of over such a short period suggests the profits generated by merchants and bankers in the City through the compensation process—both as the principals of awards and through commissions made as intermediaries in the collection of awards—could have had a material impact on individual businesses.Footnote 82 However, further research is needed to substantiate this point, and also to explore the important question of whether the payment of slavery compensation had a systemic and lasting impact on the City’s financial services sector, either in the way that it operated or in the firms that were at its heart. Our analysis reveals that the bulk of awards paid in Reduced Annuities (and almost certainly those paid in cash as well) were handled by intermediaries in the City, suggesting opportunities for “mercantile interception” of compensation awards by merchants and bankers who were lenders to slave owners were far greater than has been appreciated in recent literature on the compensation process.Footnote 83 The extensive involvement of compensation agents in the collection of awards therefore has ramifications for our understanding of the impact of abolition in the colonies. The fact most compensation payments passed through the books of British merchants and bankers would have restricted the possibilities for indebted slave owners across the British empire to escape from their creditors in the City, accentuating the financial stringencies experienced by planters in the Caribbean in the wake of emancipation.

The new stock created through the compensation process was quickly converted into cash by selling it to jobbers on the London Stock Exchange. This highlights how the City’s financial infrastructure was vital to the rapid sale of the compensation stock, mobilizing it for reinvestment in various outlets in Britain and overseas. Jobbers profited from the bid-ask spread when the stock was bought and sold, and future research may reveal that the compensation process accelerated the growth of the City’s jobbing system. The fact the Reduced Annuities were quickly sold also highlights how none of the compensation awards made in stock could still have been held in accounts owned by the direct descendants of slave owners in 2015, the year when the gilts associated with the government debt taken on in the 1830s to pay for slavery compensation were refinanced. The discovery that the compensation stock was quickly absorbed into the wider stock market underscores how the compensation process embedded the system of transatlantic slavery deeply within the British financial system, solidifying the long-lasting connection between the City and slavery which had first developed in the sixteenth century. Ironically, this strengthening of the link between the British financial system and the enslavement of Africans occurred at the very moment when the system of slavery was in the process of being abolished.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Andrew Popp and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. We are also grateful to colleagues in the Bank for comments on various versions of this paper. Staff at the Bank of England Archive, The National Archives, and The London Archives were very helpful in making material available. The dataset could not have been compiled without the assistance of a group of volunteers who helped with the transcription.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/eso.2025.1.