Introduction

Southern Ireland exited the United Kingdom with the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922. A majority of the population had expressed support for secession when the previously marginal republican party Sinn Féin secured 73 of the 105 Irish seats in the UK general election of 1918. By identifying the leading business firms of the Free State area and the political allegiances of their owners and proprietors, this paper shows that the bulk of the business elite of the time strongly favored retention of the status quo. The paper thus contributes to the study of how business owners and businesses of varying characteristics perceive their interests to be affected by political separation. There has been little research on this issue in the field of business history, though there is an extensive literature on the economics of separation, and the field of international political economy is also germane to the topic.Footnote 1

The situation in Ireland was complicated by the fact that the political fault line between unionism and nationalism overlapped to a large extent with ethno-religious identity as well as with geography and economic structure. The bulk of the island’s industry was located in the northern province of Ulster, which had a majority Protestant unionist population. Northern Ireland, which comprised six of the nine counties of Ulster, came into being when the island was partitioned in 1921 and remains to this day part of the United Kingdom. The Free State area, by contrast, was predominantly agricultural in structure and Catholic in religion. Careful analysis has found the pre-partition business establishment on the island of Ireland to have been “overwhelmingly Protestant.”Footnote 2 The composition of the business establishment in the Free State area has been less precisely identified up to this point, though the literature suggests that it too was predominantly Protestant.Footnote 3 There was a less than perfect overlap between Protestantism and unionism, however. While the present paper confirms that the majority of substantial Free State–area business owners were both unionist and Protestant, it finds small minorities of Catholic nationalists, Protestant nationalists, and Catholic unionists among the group.

The gulf between the business establishment and the majority population in the Free State area is the focus of the present paper. There were similar (and frequently much more complex) divisions in many of the other newly established states of the interwar period.Footnote 4 This was not the case in Northern Ireland where, though there was a substantial nationalist minority, the business establishment and the majority population were ad idem in their religious and political allegiances.Footnote 5

The paper goes on to explore the divergence in perspectives between the Free State–area business community and the majority population on the implications of Home Rule and secession and examines the policy and performance of the new state over its early decades in light of the concerns expressed by the business community at the time. It tracks what became of the leading unionist firms of the day and charts the legacy and eventual disappearance of the sectarian divisions then prevalent in Irish business life.

Ethno-religious polarization of the type that characterized the state for much of its existence is known to be detrimental to economic growth.Footnote 6 European Economic Community (EEC) membership from 1973 has been credited empirically with unleashing Ireland’s growth potential by reducing the country’s dependence on the UK economy.Footnote 7 The residue of sectarian divisions in the former Free State area (by now the Republic of Ireland) also finally disappeared around this time.Footnote 8 The growth consequences of this particular aspect of the Irish experience have yet to be explored empirically.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section provides a brief historical overview and is followed by a discussion of the process by which the leading firms of the era are identified. The results of the identification process are then presented. Following sections discuss in turn the major areas of disagreement over exiting the United Kingdom and developments in economic policy and business life post-independence. A final section offers concluding comments.

Historical Overview

The Irish Free State upon its establishment in 1922 was one of the least industrialized countries in western Europe.Footnote 9 Northern Ireland had a higher level of income per head and contained the bulk of the island’s industry, though it had a population less than half that of the South.Footnote 10 There were differences too in the ethno-religious composition of the populations, with a Protestant majority in the future Northern Ireland and a far larger Catholic majority across the entire island.

The origins and significance of the sectarian divide are succinctly summarized in an official publication of the Northern Irish government, which notes that the displacement of the native [Catholic] population by English and Scottish settlers from the 1600s

undoubtedly operated to introduce bitter animosities, since the incoming colonists differed both in religion and nationality from the original inhabitants, and, in addition, were regarded with all the odium attaching to supplanters.Footnote 11

Ireland had been integrated politically and economically into the United Kingdom in the early nineteenth century and Protestants, who remained wealthier on average, were for the most part strongly committed to the status quo. The largely Catholic nationalist population, by contrast, had long favored a form of devolved government known as Home Rule but was radicalized by a series of missteps by government in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising.Footnote 12 A showdown was inevitable when the previously obscure Sinn Féin party, whose leadership was openly aligned with the armed paramilitary group that would come to be known as the Irish Republican Army, secured a large majority of the Irish seats in the UK general election of 1918.Footnote 13 Britain, having just emerged victorious from a war that had seen other European empires collapse—and with India and other restless colonies looking on—was not prepared to accede to the demand for an independent Irish Republic. A period of guerrilla warfare ensued, the island was partitioned and, following the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, the Irish Free State was established with a status equal to that of Canada and the other British Commonwealth dominions.

The experiences of the two parts of Ireland had differed sharply over the course of the nineteenth century. The area that would comprise the future Northern Ireland had industrialized, and the emergence of its export-oriented linen and ship-building industries, supported by a strong engineering sector, had combined with the ethno-religious factor to ensure majority support for the Union.Footnote 14 Southern Ireland’s extensive cottage textiles sector, by contrast, had collapsed, and the region had become specialized as a “colonial” supplier of agricultural output to the British market.Footnote 15 Though modern economic historians are skeptical that tariffs could have affected the outcome, nationalist thinking became increasingly protectionist over time.Footnote 16

Big business in the Northern Ireland area was unequivocally unionist.Footnote 17 Southern Irish “big business” has also been presumed to have been antagonistic to Home Rule, though its composition has not been rigorously established until now.Footnote 18 The Dublin Chamber of Commerce had stated in 1892 that though “as a corporate body we have no politics,”

we are essentially a unionist chamber […] because in defending the union we are defending the commercial interests with which we are identified.Footnote 19

As attitudes became increasingly polarized from the 1890s, however, the desire of the chambers of commerce to avoid fracturing along political and religious lines made them increasingly hesitant to express themselves with such clarity.

Research Process and Data Sources

Two alternative methods have been employed by researchers seeking to establish the most significant firms of a particular era. One method employs as its metric some measure of stock market capitalization.Footnote 20 Confining the analysis to listed firms would be particularly problematic for the Free State area, however; first, because external firms, which are unlikely to be listed on local stock markets, tend to play a more significant role in smaller less-advanced economies; and second, because family ownership has been, and remains to this day, the dominant pattern among large domestic businesses in what is now the Republic of Ireland.Footnote 21 The other method, which is employed here, focuses on workforce size.Footnote 22 As this would exclude capital-intensive sectors such as distilling, however, this paper also seeks to identify the most significant employers in each individual industry.

There is no single data source that provides the necessary information on firm size. Shaw describes the Red Book of Commerce, a contemporary commercial directory, as “the single most valuable source” for her list of large UK manufacturing employers of 1907.Footnote 23 Ó Gráda employs a list of around 270 Irish manufacturing exporters prepared by the (Irish) Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction in 1911 to study the pattern of industrial location, presuming that these represent “the bulk of going concerns at the time.”Footnote 24 Entries for Southern Ireland in the Red Book are sparse, however, while a substantial number of the large employers unearthed here do not appear on the list employed by Ó Gráda.

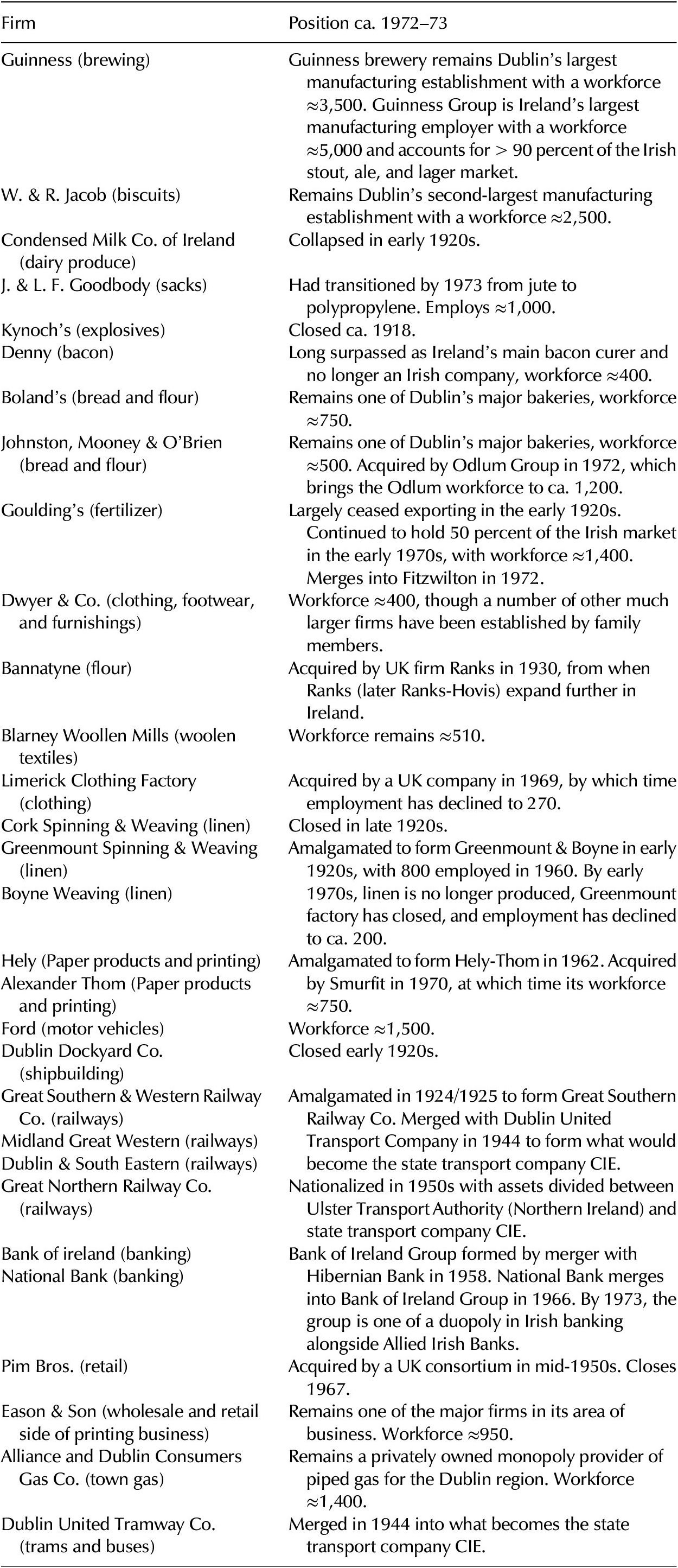

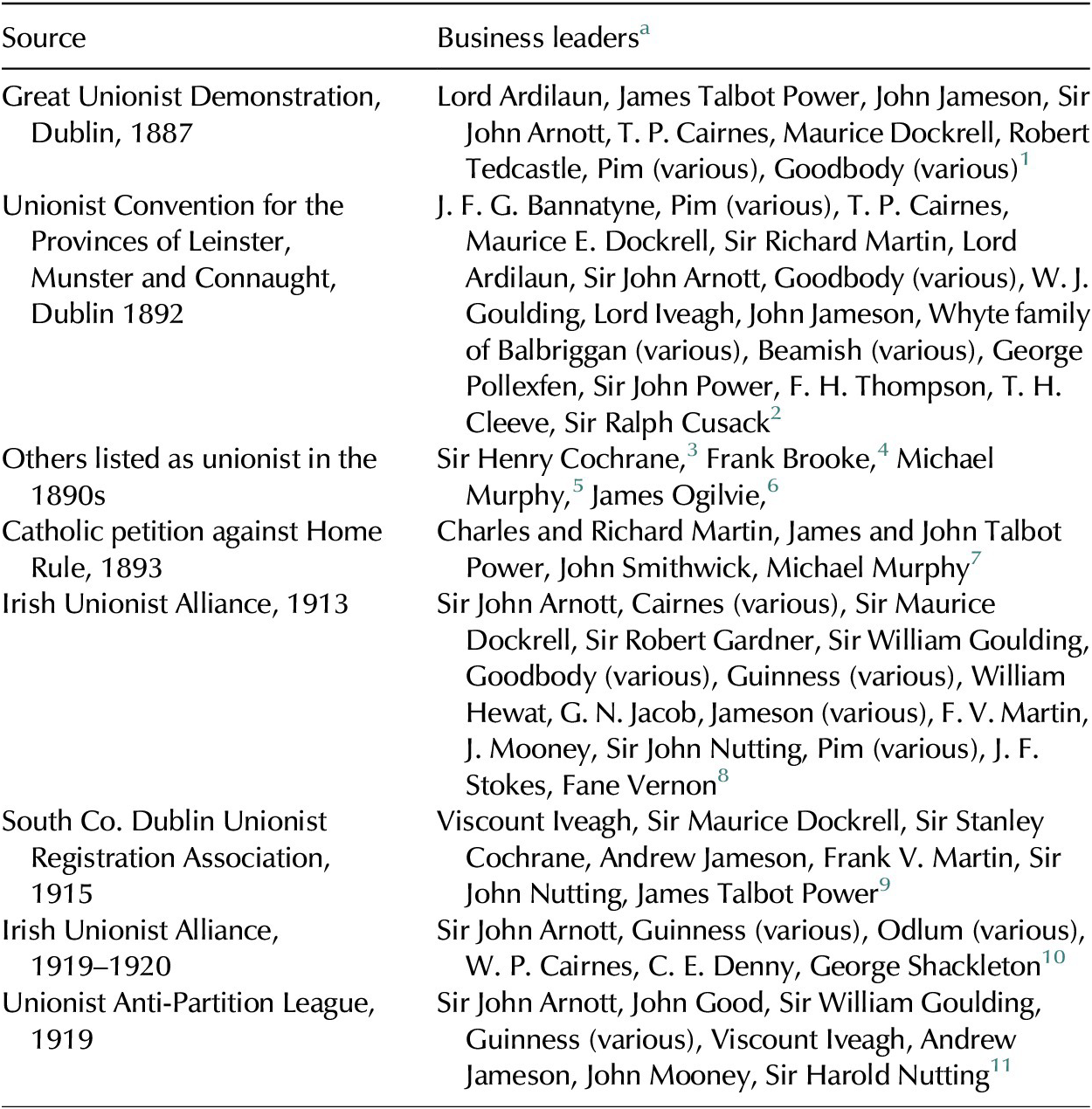

The research process began with the construction of a “long list” of candidate firms based on these and other such documents along with a broad range of academic studies and newspaper reports, with component lists compiled for each of the sectoral categories employed in the first (1926) Free State Census of Industrial Production. Stock market listings played a greater role in the case of nonindustrial sectors for which the data are less codified. The railway companies and banks dominated the stock market of the time. As ownership of these segments was more dispersed than in the case of manufacturing, the focus of attention in these cases is on the political allegiances of the chairs of the boards of directors, who tended to remain in position for periods of up to several decades. Workforce numbers are derived for the most part from contemporary newspaper reports and are then used to isolate the largest firms on the long lists. Those employing five hundred or more in the period to independence are listed in Table 1.Footnote 25 Evidence as to the political affiliations of owners and proprietors is drawn from the diverse sources reported in Appendix 1, while religious affiliation generally comes from the online population censuses of 1901 and 1911.

Table 1 Firms in Southern Ireland Employing Five Hundred or More in the Decades to Independence

The Leading Southern Business Firms and the Political Allegiances of Their Proprietors

That the industrial elite even in Southern Ireland was converging in wealth and influence on the traditional ascendancy class by the early twentieth century was reflected in the leadership of pre-independence southern unionism, of which Lord Midleton and the banker and distiller Andrew Jameson were the principal spokesmen, and in the history of the Guinness brewing family, two of whose members—Lords Ardilaun and Iveagh—had been raised to the peerage.Footnote 26

Guinness was by far the most substantial manufacturer in what would become the Irish Free State. Fewer than two dozen southern manufacturing firms employed a workforce of five hundred or more in 1929.Footnote 27 The Guinness brewery employed around four thousand in the decade to independence. Lords Ardilaun and Iveagh were conservative unionists, and two of Iveagh’s sons sat on the Tory benches at Westminster.Footnote 28 Around half of the other breweries, all tiny in comparison, were also unionist owned.Footnote 29 The Quaker biscuit company W. & R. Jacob was another major employer, with a 1914 workforce of around three thousand in Dublin and a further several hundred at its recently established branch plant near Liverpool. The chairman and managing director, George Newson Jacob, was a member of the Dublin Unionist Association and one of a group of businessmen to issue a critique of the economics of Home Rule in 1913.Footnote 30

Irish whiskey had been outcompeted by Scotch by the early twentieth century, and the industry would remain in the doldrums for many decades. Of the four remaining major southern producers, the Dublin Distillers Company—an amalgamation of firms of diverse origins—was ailing and would largely cease production in the 1920s.Footnote 31 Of the other three, only Cork Distilleries was in Catholic nationalist ownership. The chairman of Jameson, Presbyterian unionist Andrew Jameson, also served as governor and director of the Bank of Ireland.Footnote 32 Power’s was owned by a Catholic unionist family, the Talbot Powers. Jute was another sector to have emerged amid the deindustrialization of the nineteenth century.Footnote 33 The industry was dominated by the Quaker firm J. and L. F. Goodbody, which employed close to one thousand. Goodbody family members were prominent across a range of professional and business sectors and served on most of the unionist committees of the era.

Other large exporting firms included the Condensed Milk Company of Ireland, chemicals firm Kynoch’s, bacon curer Henry Denny & Sons, and fertilizer producer Goulding’s. The Condensed Milk Company was by far the largest of the private creameries to survive the emergence and expansion of the cooperative creameries from the 1890s. By the early 1920s, it was estimated to process one-thirtieth of the entire dairy produce of Southern Ireland.Footnote 34 The company prospered during World War I but collapsed with the sharp decline in agricultural product prices that followed. With a workforce of several thousand across Munster, it was controlled from its Limerick City base by the “strongly unionist” businessman Sir Thomas Henry Cleeve.Footnote 35 The Cleeves were members of the Church of Ireland, the major Protestant denomination in the South.

The leading foreign-owned manufacturing company before Ford’s commencement of operations in Cork city in 1919 was Birmingham firm Kynoch’s. Kynoch’s was owned by Arthur Chamberlain, brother of the prominent British Liberal Unionist MP who had split with Gladstone upon the latter’s conversion to Home Rule. Around three thousand jobs were lost when its cordite, explosives, and chemicals plant at Arklow closed in 1918. Denny & Sons was one of the most significant firms in the UK bacon trade and a major supplier to the wartime British military.Footnote 36 It employed around five hundred in peacetime, and perhaps substantially more in 1914 to 1918.Footnote 37 The chairman, Charles Edmond Denny, served on the General Council of the Irish Unionist Alliance. Goulding’s, by far the largest fertilizer producer, employed some 1,200 in its nine Irish plants in 1912, six of which were in the area that would become the Irish Free State.Footnote 38 Sir William Goulding was a leading southern unionist, and his brother, Lord Wargrave, sat as a Unionist member of the House of Commons until raised to a peerage in 1922.Footnote 39

Other than the long-established Blarney Woollen Mills of Martin Mahony & Brothers, all of the substantial export-oriented textile and clothing companies were also under Protestant unionist control. Limerick Clothing, established by Scottish expatriate Peter Tait, had developed an international reputation as a producer of military uniforms in the 1800s. Tait went bankrupt when a consignment of Alabama cotton bartered for Confederate uniforms was seized by Union forces during the American civil war and the company was taken over in the 1890s by a group of Limerick businessmen, the most prominent of whom was the unionist milling magnate J. F. G. Bannatyne.Footnote 40 Though much diminished in size compared to its earlier incarnation, it continued to employ more than six hundred during World War I.

There were two major hosiery firms in Balbriggan in north Dublin: Smyth & Company, which was owned by local Church of Ireland unionist family the Whytes, and the Sea Banks hosiery facility of English firm Deeds, Templar & Company, which was destroyed when Balbriggan was ransacked by British forces in 1920.Footnote 41 Each employed around four hundred, though most were outworkers.Footnote 42 The largest southern linen firm, Cork Spinning & Weaving, was owned by the Presbyterian unionist family the Ogilvies and employed around one thousand. Greenmount Spinning & Weaving of Dublin and Boyne Weaving of Drogheda were slightly smaller. Greenmount was owned by the Pims, a Quaker unionist family, and Boyne Weaving by an Ulster Presbyterian who may have been among a group of Protestant Home Rulers.Footnote 43 Smaller firms in the sector, some under Catholic ownership, were fearful of the disruption of the linen supply chain that partition would entail and viewed the establishment of the Free State with disquiet.

Domestically oriented sectors hosted a number of significant Catholic nationalist firms, including the wholesale drapery, general furnishings, and footwear operations of the Cork firm Dwyer & Company. Even in these sectors, however, most of the large firms were under unionist ownership. Within manufacturing, breadmaking, woolen and worsted textiles, and leather stood out as the only segments in which the largest firms were predominantly Catholic and nationalist.Footnote 44

Flour milling was dominated by the Limerick-based Bannatyne group, in which the Goodbody family built up a controlling stake from the 1890s. Employment in Bannatyne and its subsidiaries is likely to have exceeded seven hundred in this period.Footnote 45 Other unionist flour millers included the Church of Ireland families the Odlums and the Pollexfens (maternal family of the poet W. B. Yeats). Two of the four industrial-scale bread producers—Johnston, Mooney & O’Brien and F. H. Thompson—were Protestant and unionist; the other two—Boland’s and Kennedy’s—were under Catholic nationalist ownership. Johnston, Mooney & O’Brien and Boland’s were the largest and of broadly similar size.Footnote 46 John Mooney, principal of the former, was a leading local unionist politician, the largest shareholder in the company was Sir Robert Gardner (on whom more later), and the long-term chairman was a member of the Pim family.Footnote 47 Most of the sugar confectionery and jam producers were Protestant owned, as was the case also in sectors cognate to brewing, where the influence of Guinness loomed large. One of the most significant maltsters was John H. Bennett & Company, with which Guinness worked closely in developing new strains of barley. The Bennetts, like the Guinnesses, were Church of Ireland unionists.Footnote 48 E. & J. Burke had been established in business by their Guinness cousins as the brewery’s export bottlers, and by 1892 their Liverpool house, under the management of Sir John Nutting, was said to be the most important bottling establishment in the world.Footnote 49 Nutting, who had shortly afterward become sole proprietor, was a prominent unionist, as was Sir Henry Cochrane, proprietor of the largest mineral water producer, Cantrell & Cochrane. Other than the industrial bakers, these firms all employed well under five hundred, as did the leading local tobacco manufacturers, Goodbody’s and the Catholic nationalist firm Carroll’s of Dundalk. While footwear was largely imported and the sector hosted no substantial firms, paper products and printing enjoyed a degree of natural protection, and the two most substantial firms in these segments, Hely’s and Alexander Thom & Company, each employed around five hundred. Thom’s was chaired by a member of the Pim family, and successive managing directors took an active part in unionist politics. There is evidence too of the Hely family’s support of conservative unionist causes.Footnote 50 Printer and bookseller Eason’s also employed five hundred or more in the Free State Area, one hundred or so in their print works, and the remainder in the wholesale and retail side of the business. Though Presbyterian and private in their politics, the Easons were nationalist in their sympathies.Footnote 51

The largest employer in metals and engineering in 1920 was the recently established Henry Ford & Son, which would shortly afterward be integrated into the Ford Motor Company. Ford’s decision to open an Irish operation had been made when Home Rule was anticipated. The establishment of the Free State was damaging to the company as the McKenna tariffs were levied on its trade with Britain and Northern Ireland.Footnote 52 The other large employer in the sector was the Dublin Dockyard Company, under the control of Scottish-born Presbyterian John Smellie. It employed around one thousand in 1919, shortly before its closure. The largest Catholic nationalist firm in the sector was Phillip Pierce & Company of Wexford, whose agricultural machinery and cycle factory, the Mill Road Ironworks, employed some three to four hundred in 1911.Footnote 53

The Dublin Dockyard Company provides an example of the danger of conflating religion and political allegiance. Though the company was controlled by an exclusively Protestant board of British-born engineers, Smellie was among a group of Protestant Home Rulers within the business community, along with various members of the Quaker flour-milling family the Shackletons (though the proprietor of the Anna Liffey mill, George Shackleton, was a committee member of the Irish Unionist Alliance), the Unitarian proprietors of the largest brush-making firm I.S. Varian & Company, bacon curers Shaw of Limerick, and the proprietor of the largest southern jam and confectionery producer, Robert Woods.Footnote 54 Families other than the Shackletons also showed signs of division within their ranks. Though the Kilkenny brewers, the Smithwicks, were a well-known nationalist family—one had been a leading Repealer with Daniel O’Connell, another a Home Rule MP—John Smithwick, principal of the firm, was a signatory to the 1893 Catholic petition against Home Rule, as indeed was O’Connell’s younger son, owner of the Phoenix Brewery in Dublin.Footnote 55

The railway companies and the banks accounted for the vast bulk of stock market capital at the time.Footnote 56 Great Southern and Western Rail was the largest private-sector employer outside Ulster. Its 1913 workforce of around nine thousand was close to that of either of the massive Belfast shipyards, the largest industrial enterprises in the country.Footnote 57 The rail transport sector had long been accused of anti-Catholic bias, though the Society for the Protection of Protestant Interests maintained that differences in educational attainment were the most likely explanation for the sectarian wage differentials that had been uncovered.Footnote 58 The long-term chairman of the Great Southern was Sir William Goulding, who, along with the Arnotts, owners of a range of businesses including the Irish Times newspaper, would later be criticized by Presbyterian bookseller J. C. M. Eason for the reluctance they displayed in reconciling to the new political dispensation.Footnote 59 The second-largest rail company was the Great Northern, whose lines ran from Dublin to Belfast and across the future Northern Ireland. It employed more than five thousand in 1913 and almost three thousand in the Free State alone in 1925. Its long-term chairman, Fane Vernon, was a member of the executive committee of the Irish Unionist Alliance.Footnote 60 The Midland Great Western and the Dublin & South Eastern were the other railway companies of significance. Both had also long been chaired by unionists.Footnote 61 When Frank Brooke, chairman and managing director of the latter, was assassinated during the War of Independence he was followed as chairman (perhaps in anticipation of a change in the political dispensation) by Sir Thomas Esmonde, a Catholic and former Nationalist MP.Footnote 62

There were nine banks operating in the Free State area. Of these, the Bank of Ireland, the Provincial, the Royal, and the three Belfast-headquartered institutions were unionist in ethos. The remaining three—the National, the Hibernian, and the Munster & Leinster Bank—were viewed as broadly nationalist in outlook.Footnote 63 Both the president and secretary of the Institute of Chartered Accountants were Protestant, as were most of the council and all of the partners of the dominant firms, Craig Gardner and Stokes Brothers & Pim.Footnote 64 Robert Stokes and Sir Robert Gardner were among the 150 southern business leaders to criticize the Home Rule Bill in 1913.Footnote 65

Of the seven major Dublin department stores of the era, only Clery’s was under Catholic nationalist control.Footnote 66 Pim Brothers’ drapery and furniture store, which had a workforce of six hundred in 1894, appears to have been the largest.Footnote 67 Builders’ providers remained strongly Protestant dominated up to the 1960s.Footnote 68 By the end of the nineteenth century, Brooks Thomas and Dockrell’s had emerged as the leading firms in the sector.Footnote 69 Maurice Brooks, founder of the former and a member of the Church of Ireland, was succeeded as chairman at his death in 1905 by his son-in-law, Richard Gamble, a member of the City of Dublin Unionist Association.Footnote 70 Sir Maurice Dockrell, Brooks’s nephew, would serve as one of the few Unionist MPs elected for a Southern Irish constituency in 1918. Leading firms in cognate sectors included the Dublin timber firm T. & C. Martin, whose proprietors were Catholic unionists.Footnote 71 The principals of J. & P. Good, one of the largest building contractors, and of Heitons and Tedcastle McCormick, the largest coal-distribution companies, were prominent unionists, as were the Findlaters, owners of a range of businesses including a chain of retail stores.Footnote 72 The Findlaters, Tedcastles, Heitons, and Hewats (who took control of Heitons upon the founder’s death) were expatriate Scottish Presbyterians.

The Alliance and Dublin Consumers Gas Company and the Dublin United Tramway Company were among the few large businesses not to conform to the general pattern unearthed. The gas company was a quasi-regulated monopoly provider of public lighting. Its origins as an 1866 amalgamation of existing gas companies left a legacy of political diversity on its board. It was chaired until 1914 by William F. Cotton, a Home Rule MP, who was succeeded in the role by John Murphy, a member of a leading Catholic unionist shipping family.Footnote 73 The Gas Company employed at least 750 and perhaps substantially more in 1917.Footnote 74 The Dublin United Tramway Company was part of the business empire of the leading Catholic nationalist industrialist of the day, William Martin Murphy. Murphy was also proprietor of the best-selling newspaper group, the Irish Independent, and part owner of Dublin department store Clery’s. His various enterprises are likely to have employed a workforce of at least 1,500 in the late 1910s.Footnote 75

Table 1 shows, in summary, that of the forty-five thousand workers in the firms listed, thirty-six thousand—some 80 percent of the total—were employed in Protestant unionist-controlled businesses. A Southern unionist, writing in 1912, suggested that few among the large employers “are in a position to help the Unionist cause effectively, for they have to deal with strike makers and possible boycotters.”Footnote 76 Even much smaller unionist employers made no effort to hide their political allegiances, however, while the first strike in the Guinness brewery’s history was in 1974.Footnote 77 Though Jacob’s, the unionist-owned biscuit manufacturer, was centrally involved in the bitter industrial relations dispute of 1913, union leader James Larkin’s main antagonist was Catholic nationalist industrialist William Martin Murphy. The unionist claim does not appear therefore to stand up to scrutiny. That all of the large firms would have had predominantly Catholic nationalist workforces may have shielded them from boycott: attacks on Goodbody properties ceased when the family warned that their operations might be closed down.Footnote 78 Boycotts could be more effectively directed against retailers and distributors, and fear of antagonizing nationalist customers is understood to have conditioned the behavior of the retail banks.Footnote 79 In the case of manufacturing, the boycott was a blunter instrument. It proved impossible, for example, to discriminate other than by geography in the 1920–1922 nationalist boycott of Belfast goods, and though the prime minister of the newly devolved Northern Ireland government believed that “a boycott of stout would be impossible,” handbills advocating a counter-boycott urged the local population to “cease purchasing all southern goods,” including stout, whiskey, and biscuits, which were produced almost exclusively by Southern unionist firms.Footnote 80

Religion and politics aside, the data in Table 1 also tell us something of the degree of concentration in southern industry, though the analysis in this case is confined to manufacturing because of the availability of an appropriate denominator.Footnote 81 The top twenty employers accounted for around twenty-four thousand jobs, or some 35 percent of the Free State–area manufacturing workforce, while the top twenty in Britain employed around three hundred thousand, some 6 percent of the equivalent workforce, and the top one hundred only around 13 percent.Footnote 82

Unionist and Nationalist Views on the Union, Home Rule, and Secession

Nationalists and unionists differed in their assessments of the economic consequences of the Union. Nationalists came to blame southern deindustrialization on the economic integration of the period, while the inadequate response to the Great Famine of the 1840s was ascribed to a distant and uncaring government. Though some unionists accepted that the arrangement may not have worked perfectly in the past, they pointed to the numerous benefits that the Union had delivered since 1890 as part of a policy that came to be known as “killing Home Rule with kindness.” These included extensive land redistribution, democratic local government, improvements to education, and the establishment of bodies such as the Congested Districts Board and the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction. A generous old-age pension had also been introduced and subsidies granted to the post office, housing, and agriculture.Footnote 83

Elements of self-interest were inextricably intertwined with differences in judgment as to the consequences of any change to the status quo. The Irish stock market, however, had fallen on occasion since the 1880s with news of progress on the passage through Westminster of one or another of the Home Rule Bills of the time.Footnote 84 Hence there was an empirical basis to the 1913 warning by 150 “Tory business leaders” that Home Rule would raise the cost of finance and drive capital and industry from the country.Footnote 85

The costs and benefits of prospective trade protection were a major point of divergence, as Edward Carson, the Dublin-born leader of northern unionism, made clear when he warned in 1921 that concerns over the potential industrial consequences of fiscal autonomy meant that Ulster “would not agree to it.”Footnote 86 As pointed out earlier, the Northern Ireland area was much more heavily industrialized than the South. It was also substantially more export oriented.Footnote 87 Similar fears had also been expressed by southern unionists, however, at a meeting chaired by Lord Ardilaun in 1911.Footnote 88 The chairman of the convention established by the British in 1917 to try to secure agreement on an all-Ireland Home Rule solution noted that “the difficulties of the Irish Convention may be summed up in two words—Ulster and Customs.”Footnote 89 Britain conceded fiscal autonomy to the prospective new Irish Free State only toward the end of the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations of 1921.Footnote 90

Unionists differed from the majority of nationalists in their commitment to the imperial project. The 1917 proposal by Southern unionists that customs revenue be retained by Westminster as a contribution to war debt and defense would have achieved other of their aims as well, however, including ensuring continued representation in the imperial parliament.Footnote 91 In an apparent conciliatory response to nationalists, they made the unorthodox suggestion that control of excise be separated from customs and delegated to any prospective new Irish parliament: by a happy coincidence this would have protected the Irish brewing and distilling industries from the temperance-oriented British parliamentarians of the era.Footnote 92

Irish unionists were fearful of possible expropriation by a radical, vengeful, or sectarian Dublin parliament.Footnote 93 They also feared the enactment of “hasty legislative proposals at the expense of the 350,000 loyalists who will be practically unrepresented but who pay most of the taxes.”Footnote 94 They professed themselves skeptical of nationalist competence on fiscal matters, as evidenced by Lord Midleton’s complaint to Churchill in 1922 that

the people are exceedingly ignorant [and] morally cowards… Greatest extravagancies will probably be proposed and the proceedings [in the Free State parliament] show you how the government are likely to have their hands forced.Footnote 95

That Ireland was overtaxed had long been an article of nationalist faith. Though supported by the findings of a British parliamentary committee of the 1890s, a follow-up report of 1912 found that the balance between expenditures and revenues had since been reversed.Footnote 96 The old-age pension was the subject of particular comment. The recent UK Pensions Act had been designed with the industrial population of Great Britain in mind, though the same rates were payable in Ireland under the unified system of administration. The 1912 report regarded it as “absolutely certain” that an act designed by an Irish Parliament “would not have been of such a costly character as to absorb at one stroke nearly one-third of the total revenue of the country.”Footnote 97

Most on the nationalist side appear to have assumed that self-government would rapidly bring prosperity. Tom Kettle, one-time Home Rule MP and first professor of national economics at University College Dublin, argued that much of the fiscal burden was the result of past misgovernment.Footnote 98 Arthur Griffith, the founder of Sinn Féin, saw no reason why the island could not provide a living for a population of 15 million.Footnote 99 Erskine Childers was almost alone among those on the nationalist side to recognize explicitly the financial difficulties that might have to be faced, particularly with respect to the adjustment to pensions that he felt would be required.Footnote 100

Southern unionists also raised economic concerns over partition when it emerged as part of the policy agenda. A customs frontier between the two parts of Ireland would undoubtedly cause disruption. A report from Belfast to London immediately before the establishment of the customs frontier noted that “Dublin sends large consignments of Guinness’s stout and porter, as well as spirits, mineral waters, tobacco, matches, biscuits, confectionary and provisions into Northern Ireland.”Footnote 101 The Southern linen supply chain was particularly vulnerable, as noted in a newspaper report from 1923 that pointed out that the linen trade in the South

is almost entirely dependent on the North for its supplies. Goods are also sent backwards and forwards across the border for dyeing, bleaching, etc., and if these movements are to be made more difficult and expensive it will certainly mean that an already hard-hit industry cannot be carried on.Footnote 102

The Dublin Chamber of Commerce had warned that partition would exacerbate the lack of economic expertise by depriving the prospective southern parliament “of the steadying influence and business training of the men of Ulster.”Footnote 103 It also expressed concern at the costliness of the further duplication of administrative machinery that partition would entail.Footnote 104

Developments in Economic and Business Life Post-independence

The first decade of independence proved much less traumatic for the former unionist business community than had been feared. One of the first acts of the Provisional Government was to appoint the Bank of Ireland as its financial agent in 1922. The new government prioritized stability, and the support of former unionists swung behind it when civil war broke out in 1922–23 over the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The informal partnership established between William Martin Murphy, Presbyterian Charles Eason, and Quaker George Jacob during the bitter Dublin lockout of 1913 helped to stabilize business sentiment.Footnote 105 So too did the appointment by government of a number of former unionists, including Andrew Jameson, to the upper chamber of the new parliament, and the presence of brewer Richard Beamish, building contractor John Good, and coal distributor William Hewat among the four business representatives elected to the lower chamber in 1923.

Though it had been widely assumed that the Free State would be protectionist from the outset, only modest trade barriers were imposed in the first decade of independence, as had been predicted by William Martin Murphy, among others, in 1917.Footnote 106 Export-oriented agriculture, in the view of the Free State Fiscal Inquiry Committee of 1923, “must be considered as of paramount importance.”Footnote 107 Trade and banking interests had also been fearful that independence might lead to a severing of the currency link with sterling. By the time a decision on currency matters came to be made in 1927, hyperinflation had led to the collapse of a number of continental currencies and “hostility toward inflation [had become] the leitmotif of economic policy across Europe.”Footnote 108 The one-to-one link with sterling was retained and would survive for a further fifty years.Footnote 109

Unionist concerns that the new state might prove financially irresponsible were definitively laid to rest. The state was born into fiscal crisis. Compensation for property losses and expenditure on the army absorbed almost three-quarters of government revenue in 1924.Footnote 110 The pension rate inherited from British rule would have had to have been cut by at least one-third were a relationship to national income equal to that in Britain to be established. A cut of one-tenth was imposed in preparation for the launch of the first national loan, when establishing the creditworthiness of the new state was a priority.Footnote 111 The cut in the pension rate is widely understood to have been a factor in the government’s defeat in the general election of 1932.Footnote 112

As for the alternative of raising income tax, here too the government was constrained. It was believed that if economics lay at the core of the North–South divide, then low taxation might make a united Ireland more attractive to northern unionists.Footnote 113 A further constraint was the danger of capital flight: “Some of those who paid large amounts in income tax were out of sympathy with the new regime and transferred their domicile to Great Britain.”Footnote 114 By 1928 the Irish tax rate had been reduced below that of the United Kingdom and would remain lower under the more radical Fianna Fáil administrations that held office from 1932.Footnote 115

The business elite did not have everything its own way, of course, even in the 1920s. The auditing contracts for major new state companies were largely directed to emerging Catholic firms rather than to the traditional accounting duopoly, and there were disagreements over railway amalgamation and electricity generation, with some developments pertaining to the latter criticized by business interests and the Irish Times as “socialist” and “confiscatory.”Footnote 116 Significantly, the Free State did not follow the United Kingdom in abolishing the corporation profits tax in 1924.Footnote 117 Objections to these measures were generally led by parliamentarians of the former unionist camp.

Though relations between the business establishment and the Fianna Fáil governments of the 1930s were more fraught, private sector attitudes toward protection had begun to change with the onset of the Great Depression, which preceded Fianna Fáil’s accession to power.Footnote 118 Goodbody Jute welcomed the protection it received from the encroachment of cheap imports from Calcutta, and expansion of the domestic sugar industry provided a new source of demand for its sacks and twines. The Southern linen industry, which had been threatened by the erection of a customs frontier with Northern Ireland, lobbied for the imposition of a tariff on imports.Footnote 119 The department stores expanded their manufacturing businesses behind the tariff wall: Arnott’s “thanked God and the government’s economic nationalism of the 1930s for the development of new knitting and making-up industries.”Footnote 120 The timber firms and builders’ providers benefited from the expansion in housing construction initiated in Ireland (as in Britain) during the Depression. Guinness and Jacob’s protected themselves by building or extending factories in England.

As to the impact of independence on economic growth, though relatively little convergence on UK living standards was achieved over the half-century to EEC membership Pollard suggests that Ireland’s problems, rather than stemming from independence, “were more akin to those of the major non-industrialized regions inside advanced countries, like the Italian South, Corsica, and the French South-West.”Footnote 121 Northern Ireland, which remained part of the United Kingdom, also underperformed.Footnote 122

Many of the long-established firms, though they had become less export oriented over the protectionist era, remained on the list of the “fifty largest Irish industrial companies” published in 1966.Footnote 123 The position at EEC accession in 1973 of each of the largest companies of the pre-independence era is detailed in Appendix 2. Though there were, of course, a diverse array of experiences, Goulding’s remained by far the largest fertilizer company, the Odlum Group vied with Ranks-Hovis (which had taken over Bannatyne in 1930) as the largest integrated bread and flour-milling operation, Guinness and Jacob’s were respectively the largest and second-largest manufacturing establishments in Dublin, and the Guinness Group was the largest manufacturing employer in the country.

Sectarian divisions in the workplace had diminished by the 1960s but had not yet disappeared.Footnote 124 Bowen reported that among a small survey group of south Dublin Protestants, most who had entered the labor market before 1955 had found their first positions in workplaces where the majority of their coworkers were Protestant.Footnote 125 Developments external to the firms ensured that this could not persist indefinitely. As Lyons writes of the Bank of Ireland:

An increasingly Catholic representation on the Court of Directors and the recruitment of a predominantly Catholic staff would … have become inevitable with the striking decline of the Protestant population in the decades after independence.Footnote 126

Not all of the imbalances in recruitment and management were ascribable to sectarianism, as Cullen observes in his study of Eason’s:

Staff were recruited from the immediate circle of the principal, and since many recruits were accepted on the recommendation of the senior people in the firm, continued recruitment tended to be slanted in that direction.Footnote 127

Eason’s first appointed a Catholic to its board in 1947. Craig Gardner appointed its first Catholic partner in 1944. Until the 1960s at least, however, many firms continued to be known to the public as either Protestant or Catholic.Footnote 128 Businessman Michael Smurfit reports that Catholic firms such as his could find it difficult to make sales to Protestant companies, in many of which Catholics could never join the management team, “no matter how good they were at their job or how considerable the contribution that they could make.”Footnote 129

The liberalization of trade and ownership restrictions from the late 1950s triggered a wave of mergers and acquisitions that paid no heed to the religious associations of earlier times.Footnote 130 The earliest developments took place in banking. To avoid the threat of foreign takeover, Bank of Ireland merged with the Hibernian Bank in 1958, a development that “would have astounded the Hibernian’s founders [owing to] the political and religious preferences” of the former.Footnote 131 The National Bank, another of the traditionally Catholic nationalist banks, joined the group in 1966. A similar fusion of traditions occurred with the formation of Allied Irish Banks later that year through the merger of the remaining southern banks. Stokes Brothers & Pim merged with the Catholic firm Kennedy Crowley in 1972 to form the largest accountancy group in the state. The entrance of an American firm into the milk distribution business in 1964 triggered the merger of rival Catholic and Protestant distributors. Jacob’s and Boland’s Biscuits merged in 1966, as did Jameson, Power’s, and Cork Distilleries. Smurfit acquired the previously merged Hely’s and Alexander Thom in 1970. The old Protestant unionist firms Goulding’s and Dockrell’s were acquired by Catholic entrepreneur Tony O’Reilly in the early 1970s. Guinness bought up most of the remaining Irish brewers.Footnote 132

Liberalization too brought an increased focus on the importance of education, as represented by the publication of the landmark report Investment in Education in 1965.Footnote 133 Education in Ireland up to that point has been described as designed to reproduce “a certain social type, pious, familial, loyal to the native acres, culturally ingrown and obedient to clerical guidance in matters moral and intellectual.”Footnote 134 This report by contrast, and others that followed in its wake, emphasized education as the means by which society invested in itself and prepared for the future. A major restructuring of the system was initiated and throughput expanded substantially. Educational credentials had formed a significant component of the criteria for public-sector recruitment since the foundation of the state: personal connections became relatively less significant from this time as a route through which new staff were recruited in the private sector.Footnote 135

Concluding Comments

The paper has addressed questions as to the composition of the Southern Irish business establishment in the decades to the foundation of the Free State in 1922, the views of the business elite on the issues pertaining to Home Rule and secession, and the post-independence legacy of the divisions of the time between the business elite and the broader population. The substantial bulk of the significant firms are found to have been under Protestant unionist ownership and control. Though unionism largely overlapped with Protestantism, the business establishment also included small minorities of Protestant Home Rulers, Catholic unionists, and Catholic nationalists. Only in certain narrow segments did Catholic nationalists predominate.

Nationalists and unionists subscribed to different interpretations of the historical consequences of political and economic union within the United Kingdom. They also espoused different views as to the likely consequences of secession. Kennedy finds the debate between the two sides to have diminished in sophistication since the 1890s, as “the imminence of the realization of the nationalist dream made close analysis less of a necessity.”Footnote 136 The fears of the unionist business community proved over the decades to have been largely unfounded. Only very modest tariffs were introduced in the 1920s because, earlier nationalist rhetoric notwithstanding, this was the policy deemed by government to be in the national interest at the time. The shift to protectionism in the 1930s was part of a worldwide phenomenon. Many of the former unionist firms welcomed it in the context of the Great Depression, while the largest exporters avoided foreign trade barriers by engaging in tariff-jumping foreign direct investment. Macroeconomic discipline was maintained.

Paradoxically, while protectionism led to a large increase in the number of firms under Catholic nationalist ownership, it facilitated the survival of traditional business practices. The erosion of the sectarian divide in Irish business life accelerated dramatically with the opening up of the economy from the late 1950s. By the time of EEC entry, the era of tightly controlled family businesses was largely at an end, denominationally distinct workplaces had all but disappeared, many of the traditionally Protestant and Catholic firms had merged, and educational credentials were coming to displace personal connections as the main route through which new staff were recruited in the Irish business sector.

Appendix 1 Selected Sources on Unionist Affiliations

Appendix 2 History to EEC accession (1973) of the largest firms of the pre-independence era