Introduction

In Western democracies, advertising has been a central part of political campaigns for at least a hundred years, and political parties have been important customers for both advertising services and advertising space. It is much more uncommon for political parties to operate advertising companies, or even companies at all, that also have external commercial customers.

The Swedish advertising group Förenade ARE-Bolagen (“the ARE Group”; hereafter AREFootnote 1), which operated from 1947 to 1997 (when it merged with the French outdoor advertising group JCDecaux), was such a party-owned company. The Social Democratic Party, which governed Sweden—either alone or as a senior coalition partner—for forty-one of the fifty years that the company existed, was the majority owner.Footnote 2

ARE eventually became the largest outdoor media group in Sweden. In 1988, for example, ARE controlled 80 percent of the market for advertising in mass transit systems (buses, streetcars, bus stops, metro systems, etc.) and almost half of the market for outdoor advertising (public billboards, etc.); its main competitor, Wennergren-Williams (which later merged with Clear Channel), controlled most of the remainder of the market.Footnote 3 ARE was also one of the largest direct-mail companies in Sweden.

The purpose of this study is not only to make an empirical contribution on the rather peculiar history of ARE, a company that despite its strong position and importance within Sweden has previously not been the object of historical scrutiny, but also to contribute to the research on party-owned enterprises (sometimes called POEs, Parbus, or party-state capitalism; hereafter POEs)—a topic that has been virtually overlooked by business historians.Footnote 4

Commercial, profit-driven companies with external customersFootnote 5 owned by political parties are rare, especially in Europe and North America, and the literature on POEs, regardless of the field of research, has focused on companies in developing countries or emerging economies, such as Ethiopia, Eritrea, Malawi, Uganda, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Rwanda.Footnote 6 As scholars of POEs (e.g., Abegaz) have claimed that socialist parties tend to shy away from POEs and that they are phenomena primarily of low-income countries, a new case of a POE controlled by a socialist party in a developed country has value in itself.Footnote 7

In this paper, I find that the viability of ARE was due to the extraordinary length of time that the Social Democratic Party held power in Sweden. A POE such as ARE does not make economic sense if the owner expects to lose the next election. This explains not only why other political parties in Sweden never operated similar companies but also the virtual absence of POEs in other Western countries.

From ARE’s foundation in 1947, twenty-nine years passed without the Social Democratic Party being out of power. The kind of long and stable grasp of power necessary for POEs to emerge or grow is quite rare in the democratic world, with the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, the Liberal Party in Canada, and the Swedish Social Democratic Party being the notable exceptions.Footnote 8 Instead, party-controlled, cooperative (mutual) companies are the type of companies that show the closest resemblance to POEs. For long periods during the 1900s, the Swedish Social Democratic Party and organizations close to it also had interests in commercial activities that were often operated as cooperatives, including construction (BPA), insurance (Folksam), real estate (Riksbyggen), vacation travel (RESO), retail sales (KONSUM), oil refining and gas stations (OK Petroleum), and funeral services (Fonus).Footnote 9 The cooperatives and their business models differ from those of ARE in important respects. Rather than generating profits for the investors, cooperatives are usually established for a different purpose—providing access to goods, services, or financing at favorable terms for members.

ARE, on the other hand, was founded as a commercial venture intended to exploit an asset held by the Labour movement—access to advertising space in fairgrounds (Folkets Park) and community centers (Folkets hus) and, through labor unions, space on union billboards in factories. Later, ARE also exploited the political advantage of having preferential access to municipal outdoor advertising space and to space in mass transit systems.Footnote 10

The case in this study also helps us to better understand corporatist institutions. During most of ARE’s existence, which was roughly during the Cold War, Sweden was viewed as a corporatist country.Footnote 11 Party-owned companies can be described as a form of corporatist entities, especially when the owner party is the ruling party. Then, the company becomes a hybrid between a private and a state-owned enterprise. In this sense, party-owned companies are similar to businesses operated by the military for profit and to the benefit of (usually) the senior ranks of the officer corps (e.g., Milbus, a type of corporation that existed in countries such as Thailand, Pakistan, Egypt, and Turkey).Footnote 12 In the case of a Milbus, the armed forces represent the institution that provides the necessary stability and legitimacy; thus, a Milbus can exist where political stability is lacking.

In this paper, I will provide a narrative history of ARE covering the fifty years that the company operated. This contribution adds to the previous business history literature on the advertising industry and on the Swedish advertising industry, of which the latter only recently has become a subject of interest for business historians.Footnote 13

I will also connect the rise and fall of ARE to political development in Sweden and to the development of the advertising industry. Although ARE was shaped by a combination of factors that were specific for Sweden during the second half of the twentieth century, the insights into POEs, as I have indicated earlier, are of general interest. I will follow the tradition of scholars in political economy and view POEs as a special form of rent seeking.Footnote 14 However, neither the actual advertising—that is, the design of advertisements and ephemera—nor the cultural impact of advertising will be discussed in this paper.Footnote 15

This paper is based on extensive research conducted in three significant archive collections, namely, the Swedish Labour Movement Archive and Library (ARAB) in Huddinge, the Swedish National Archives in Stockholm, and the Centre for Business History in Stockholm, as well as two private collections, namely, Lars Nilsson’s private ARE archive in Stockholm and Bengt Öster’s personal collection in Arbrå. The archives of the Labour movement contain both the papers for ARE (including companies that merged with ARE) and the papers of the Swedish Social Democratic Party; the Centre for Business History holds the archives of JCDecaux; and the National Archives contain the papers of the Energy Savings Committee, a client of great economic significance for ARE from 1973 to 1982. With the exception of the Energy Savings Committee papers, none of the archival collections are complete. Together, however, they make it possible to draw a reasonably detailed picture of ARE from its foundation to the merger with JCDecaux.Footnote 16 The archival sources have been complemented by a number of oral-history interviews with people who either worked at ARE or had insight into the company in their roles as owner representatives or customers.Footnote 17

The paper is organized as follows. First, I provide a brief description of the development of the Swedish advertising industry during the second half of the twentieth century. This section is followed by a three-part narrative history of ARE, including its foundation and growth, its peak, and its decline and demise. The empirical parts are then followed by sections on governance, financial performance, and how the company was affected by having the Social Democratic Party as its owner. I also discuss the question of ARE as a POE. The paper ends with a concluding discussion.

Advertising in Sweden 1947–1997

When ARE (under the name “Folkreklam,” meaning “Advertising for the People”) was founded in 1947, the most important segments of the Swedish advertising industry were cartelized. The cartel had existed since 1923 and comprised companies active in print media advertising. At that time, advertisements in newspapers constituted the dominating advertising channel, because radio was a government monopoly and free from advertising (the same would apply to television after its introduction in 1957). The cartel was organized around an agreement between the Swedish Newspaper Publishers Association and the trade group representing adverting agencies, which required certification of advertising agencies. Certification was needed to place ads in newspapers on commission. The commission, usually 15 to 25 percent of the list price of the advertising space, was supposed to cover the costs of designing the ads; this made it unprofitable for advertisers not to use certified agencies, as the advertisers then had to pay for production costs in addition to advertising space costs; rebating was prohibited. This system, therefore, steered business to the cartel members. Advertising agencies could charge for special services such as artwork, but not for the design of ads, copy, or concepts. Entry was restricted by requiring new members to have an established customer base, to have leadership with previous industry experience and who were in good standing, and to post a financial guarantee. The number of certified agencies was initially capped at twelve. This restriction was dropped in 1925, but the number of certified agencies nevertheless did not exceed twelve until 1942.Footnote 18

Participating companies were prohibited from providing advertising services for channels other than print media, although some transgressions were allowed in practice. During the period when ARE operated as an advertising agency (1957–1992), there were four agencies that had more than one hundred employees: Svenska Telegrambyrån, Gumaelius, Ervaco, and SVEA, with the first two each having more than three hundred employees. Approximately 90 percent of the revenue of the advertising industry went to cartel firms (mostly to the big four).

Because outdoor and transit advertising was outside the scope of the cartel, ARE did not face competition from established advertising firms. Although ARE was primarily an outdoor advertising company, it should be noted that the creative advertising agency part (which operated under the names NU-reklam, ARE Idé, and ARE Annonsbyrå) was a medium-sized agency by Swedish standards, with between thirty-five and one hundred employees. ARE offered advertising services in a number of areas in addition to outdoor advertising, including direct mail, in-store displays, and cinema advertising. The cartel was found to be in violation of competition law in 1956, but it took until 1965 for the it to be disbanded.

The end of the cartel significantly changed the advertising industry. Even though the big four would survive for another ten to twenty years, the structure of the industry was fundamentally changed.Footnote 19 A number of new advertising agencies were founded and rapidly took significant market shares.

The cartel’s demise led to a sharp increase in the number of firms, from 50 in 1965 to 150 firms ten years later, with most being very small. The big four also lost their position; instead, new “creative” agencies took over.Footnote 20

The advertising companies also came to change their business model from relying on commissions from newspapers through brokered advertisements to charging clients by the hour. Specialized media brokers also took over the purchase of advertising space from the advertising agencies. ARE, however, continued to mediate outdoor and transit advertising space.

Following the end of the cartel, another significant change took place: the public sector began using advertising. The breakthrough for this was the campaign for righthand driving in 1967, which was the first major public information campaign in Sweden after World War II. Revenue from public sector contracts came to be of great importance, especially for the large advertising agencies that had dominated the industry during the cartel era. For the big four and for ARE, these clients served as compensation for the loss of commercial customers to the new creative advertising agencies.Footnote 21

Despite ARE’s dominant position in outdoor advertising, the company was never subject to action for uncompetitive behavior. The first comprehensive competition law was introduced in Sweden in 1953 and stated that the government could intervene in cases of harmful restrictions on competition. This was the law that was used against the advertising cartel, but it was not used against dominant companies. In 1983, a new competition law was enacted that included a provision on acquisition control, which allowed the government to intervene to stop mergers and acquisitions that would have particularly harmful effects on competition.Footnote 22 This statute was also not used against ARE.

A New Type of Advertising Agency—the Founding of Folkreklam

The company that would later become the ARE Group was created by an initiative of Sven Rydstedt, who in the late 1930s was running a small advertising agency called Rynå Reklam in Gothenburg. Rynå Reklam was not part of the advertising cartel and was thus shut out of print advertising.

During the municipal election in 1946, Rydstedt contacted the Social Democrat politician Sven Andersson (later party secretary, minister of defense, and foreign minister) to discuss campaign advertising. Rydstedt further proposed a new advertising venture to sell advertising space at venues controlled by the party and its affiliate organizations within the Labour movement. Andersson declined. Andersson claims that Rydstedt answered, “Then, I will simply go to the next political party and offer my services.”Footnote 23 The threat of Rynå Reklam working for political competitors caused Andersson to change his mind and commit to the project. Andersson brought Rydstedt’s idea to the president of the Swedish Community Centre Association (Folkets hus), Karl Kilbom, who in turn presented it to Ragnar Lundqvist of the Swedish Association of People’s Fairgrounds (Folkparkerna). Kilbom and Lundqvist agreed to join the venture and attempted—unsuccessfully–to recruit LO (the Swedish Trade Union Confederation) as a partner in the venture. Both Kilbom and Rydstedt had earlier been active communists, and Kilbom had even been sentenced to prison for unlawful intelligence activities during World War II, an issue that initially created problems for the company. Only after Social Democratic prime minister Tage Erlander had given his permission was it possible to proceed.Footnote 24

Early in January 1947, the Social Democratic Party eventually decided to take a 50 percent share in the planned corporation. The party contributed share capital of SEK 7,500. “It was decided to, no later than February 1, start […] Folkreklam, with advertising on bulletin boards, both outdoors and indoors, the latter at workplaces [such as factories].”Footnote 25 Representatives of the Social Democrats on the board of directors would be Anders Nilsson and Sven Andersson.Footnote 26 Rydstedt became the first president of Folkreklam—a position he would keep until 1962.

The early minutes from the board meetings bear witness to a company with high commercial ambitions and rapid growth. As early as just two months after the founding of the company, Rydstedt could report to the board that they had “144 sites ready with room for 1,244 advertising posters in 31 towns, the rest in smaller municipalities and larger villages—distributed over 84 fairgrounds, 47 community centres and 11 in town centres.”Footnote 27

In addition, they had negotiated contracts for factory advertising at eleven factories in Stockholm, comprising a total of twenty-four boards, and two in the town of Gävle.Footnote 28 The profits were expected to be high, as every billboard would provide revenue of SEK 2,400 per year.Footnote 29 Two weeks later, the number of advertising locations had increased to 144 and the number of factory billboards to 180.Footnote 30

The company also began negotiations with the City of Stockholm, and Folkreklam was offered the rights to approximately twenty advertising pillars at a price of SEK 750 per pillar per year—a price deemed to be too expensive.Footnote 31 Negotiations continued, and an agreement on twenty pillars at a price of SEK 600 each was reached later in 1947.Footnote 32 In September 1947, Folkreklam reported that they had the rights to 267 billboards, of which 39 were pillars, with room for a total of 1,608 advertising posters, distributed over 157 urban areas.Footnote 33

The contract with the City of Stockholm meant that the company had entered a new phase. Until then, Folkreklam had primarily obtained space for advertising posters in fairgrounds and similar venues controlled by the Labour movement, where there was no competition; now they entered a market in which they were in direct competition with other advertising companies.Footnote 34

Most likely, thoughts of a corresponding contract with the City of Gothenburg were included in the planning when the company was founded. Andersson had a background in the municipal politics of the Social Democrat-governed Gothenburg and would therefore have foreseen the potential for a takeover of the advertising space within the public transit system and elsewhere by the Labour movement. However, the first contract with a public transit system was entered into with the City of Stockholm. In 1948, Folkreklam concluded a contract with the Public Transport Authority in Stockholm, granting it exclusive rights to advertising on streetcars and buses.Footnote 35 The sale of advertisements, however, did not begin until 1949, and it was not until 1950 that any posters were physically placed.Footnote 36 It was a “fairly modest advertising supply; there were only inside objects in streetcars and busses.”Footnote 37 In 1949, Folkreklam managed to obtain the right to sell advertising space on suburban trains and in stations in and around Gothenburg.Footnote 38 The rights to advertising on the streetcars in Gothenburg itself were not obtained until 1959.Footnote 39

Folkreklam also expanded though mergers and acquisitions. The first of a long series of these began in 1948 with the acquisition of the display advertising company Hillers Dekorationsateljé.Footnote 40 Further expansion occurred in 1949 through the acquisition of AB Ute Reklam, an established outdoor advertising company. Ute Reklam was founded in 1892 and was thus one of the country’s oldest outdoor and transit advertising companies.Footnote 41 Through this acquisition, seventy additional advertising pillars in Stockholm became available to ARE.Footnote 42

Andersson described the early times as turbulent:

The problem during the early times was to hold back Rydstedt, who expanded at a pace that scared in particular Karl Kilbom, who was cautious with regard to business economics. Within a year, Folkreklam had become a company with approximately 100 employees and with big plans for the future. Several small businesses within the advertising domain were acquired. The whole thing looked adventurous, but there was no way [of] stopping Rydstedt. In spite of a scarcity of money, he kept the ship afloat and created a solid foundation for the largest advertising company within the Labour movement.Footnote 43

ARE’s advertising activities also expanded geographically. In 1952, a local office was opened in the city of Malmö, where the company had begun selling space on billboards and advertising pillars. During the mid-1950s, there was also a local office in the city of Norrköping.Footnote 44

Although the company continued to expand—organically and through acquisitions—its core business of outdoor and transit advertising, from the mid-1950s ARE began to operate outside these areas. An important milestone in the company’s development was reached in 1956 when it opened its own independent advertising agency, NU-reklam and begun offering creative advertising services.Footnote 45 In 1960, the company, which by then had undergone a name change to Förenade ARE-Bolagen (the United ARE Group), acquired a silk-screen printing company, which enabled it to print certain advertisements (e.g., those placed on buses) in-house. ARE obtained additional revenue by requiring customers to use its printing plant to print their posters. In 1962, the established outdoor advertising company Novaprint was acquired, and ARE thereby became the largest outdoor advertising company in the country.Footnote 46 This acquisition added 480 advertising poster sites to ARE’s inventory.

In 1963, the direct-mail company Ekonomidistribution was acquired from the Social Democratic youth organization Sveriges Socialdemokratiska Ungdomsförbund. After the acquisition, it became ARE Direktreklam and was the foundation for a business area that would later become one of ARE’s largest.Footnote 47

Rydstedt’s last year as president was 1962. Following that, he became editor-in-chief for the Social Democrat newspaper Ny Tid in Gothenburg. Party treasurer Ernst Nilsson became the new president.

In 1964, an important new step was taken through a contract with the City of Stockholm that gave ARE exclusive rights to advertising in the Stockholm metro. Advertising in the metro was nothing new; it had been present from the very start. However, the rights to advertising had been given by the City of Stockholm to a company of its own, an action that had created a certain amount of awkwardness within the Labour movement. Bengt Göransson claims that the decision not to let Folkreklam have the advertising rights in the new metro system was viewed as a “betrayal, motivated by partisan politics” by the City of Stockholm, which at the time had a center- right majority.Footnote 48 It is unclear to what extent party politics was behind the decision to handle metro advertising within the municipal government, but eventually, when the power had shifted to the Social Democrats, advertising rights were given to ARE.

In 1965, for the first time, ARE expanded outside Sweden with a Danish subsidiary, ARAS. This company obtained the rights to the advertisements in the public transportation system in Copenhagen. All acquisitions were made without borrowing and without paying the sellers in shares, indicating that cash flow was good from the outset.Footnote 49

The 1970s was a time of continued growth. The expansion of the public sector was accompanied by increased demand for advertising and information services.Footnote 50 In 1971, when party treasurer Allan Arvidsson took over as president, ARE had 350 employees.Footnote 51

ARE continued its expansion in outdoor advertising, and in 1971, it entered into a contract with the City of Stockholm department of roads and public transport concerning 120 “map cabinets” (lighted pillars).Footnote 52 In addition, it expanded the direct mail business by acquiring the direct-mail company Directus in 1972, thus becoming one of the largest direct-mail companies in Sweden. At this time, the Social Democratic Party acquired the brand Svenska Galliupinstitutet, and thus also an association to the international Gallup Association. The brand was later transferred to ARE, which used it for polling in the service of the party; there are no indications that Svenska Gallupinstitutet had external clients during this period.Footnote 53 Polling was never a significant source of revenue for ARE, but the inclusion of Svenska Gallupinstitutet serves as indication of the wide scope of businesses under ARE’s umbrella.

ARE further consolidated its position within mass transit advertising in 1973 by concluding five-year contracts for advertising on and in public transportation in Stockholm and Gothenburg and for the Stockholm metro system.

By this time, ARE had grown so large that it became a target of criticism. In 1975, the Swedish parliament criticized the Social Democrat Party for its ownership of the direct-mail company Directus. Parliament decided to “recommend” that the “ownership structure in the area of direct mail should not be connected to political parties.”Footnote 54 This recommendation did not lead to any action, however. The Liberal Party also noted that the Social Democratic government had treated direct mail more favorably than other forms of advertising in terms of data protection regulation and tax policy.Footnote 55

The next year, a widespread and fiery debate occurred in the media regarding whether the Social Democrats in Malmö city hall had favored ARE over other advertising companies when assigning advertising space.Footnote 56 ARE also lost previously held advertising spaces. In 1975, it was forced to terminate ARE Postaffischering, which had sold advertising space at post offices, as a result of the merger between Kreditbanken (a state-owned bank) and Postbanken (the banking branch of the government post office) that created PK-Banken. PK-Banken wanted to use the available commercial space for its own advertisements.Footnote 57

During this period, the company created a number of departments for all sorts of new types of advertising, including on taxicabs, on shelters and huts at bus stops and streetcar stops, in illuminated map cabinets, and on farm machinery. The profitability of these activities was questionable, however.Footnote 58

Peak and Decline

The 1980s, in many ways the company’s heyday, were a highly profitable decade for ARE. The company now totally dominated the market for transit advertising. In 1988, ARE controlled space on 2,300 buses, 325 streetcars, and 1,024 metro carriages, corresponding to a market share of 80 percent. In addition, it controlled the advertising space in all stations of the Stockholm metro “from large boards to decals on doors.”Footnote 59 At the same time, ARE had 4,500 objects (primarily billboards) spread over the entire country, was well as advertising space on 3,000 bus stops and streetcar stops in 12 cities and 70 advertising pillars in Stockholm.Footnote 60

The competitive situation then looked entirely different than it had only twenty years earlier. As late as the 1960s, there were at least fourteen outdoor or transit-based advertising companies in Sweden.Footnote 61 In 1980, only ARE, Bendex, Valles, and WW remained.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the advertising agency still had a strong position in terms of orders from public sector entities. ARE Idé 1 (the part of the company that handled the non- party-affiliated production of advertisements) had, according to the chairman of the board, Damberg, “been entrusted with a good part of the information activities of the public sector.”Footnote 62 Later, however, customers from within the Labour movement increasingly took over the creative activities. The internal activity reports show that it was customers who were part of the Labour movement who placed large orders. “The assignments from Lotteribyrån [the lottery run by the Social Democratic Party—another POE] increased in lockstep with the success of the lotteries. The Lotteribyrån was now the dominant customer and at times constituted half of the creative advertising agency work.”Footnote 63

At the same time, the 1980s were a period of adversity. In 1985, ARE lost the advertising in the public transport system in Copenhagen after a public tender process. However, it still controlled approximately 4,000 billboards in commercial centers in Danish cities and thus retained a strong position in Denmark.Footnote 64 The same year, ARE Idrottsreklam (sports advertising) experienced several setbacks. For one, the City of Stockholm decided that the rights to advertising at the football venues Söderstadion and Stockholms Stadion should be awarded to the Hammarby IF and Djurgårdens IF clubs. For another, the public television monopoly demanded the right to approve all advertising messages displayed in sports arenas.Footnote 65 A number of activities were also terminated, including the sale of advertising space on union billboards—one of the original services ARE offered.Footnote 66

There are probably several explanations for this decline. First, the strong grip that the company had over the public sector had begun to loosen. Second, new advertising agencies, such as Hall & Cederkvist, Garbergs, and Forsman & Bodenfors, part of the second creative revolution, had entered the market and competed with ARE.

This lack of competitiveness was reflected, among other places, in the hourly rates for the agency, indicating that ARE competed on price. In ARE’s annual report, it is mentioned that “the hourly rates charged by some ‘hot agencies’ are in the neighbourhood of 1,000 SEK per hour. At this time, our highest hourly rate is 480 SEK—a little under the average.”Footnote 67 At the same time, ARE had problems with quality in the company’s most important area of activity, outdoor advertising. An inspection in 1989 showed that 10 percent of the objects (i.e., the poster pillars or billboards) were flawed: they were incorrectly glued, damaged, needed paint, lacked name plates, or had similar problems.Footnote 68

With the exception of ARE’s last years of operation, the profitability was very good. In combination with owners who did not require any dividends and an extravagant culture within the advertising community, this meant that a considerable amount of money was spent on activities that may not have been strictly motivated by business considerations.

In the advertising business, companies constantly face the problem that after a few years, productive employees move to a competitor or start their own advertising business, often bringing customers with them from their previous employer. This problem, however, does not seem to have been severe for the ARE advertising agency. The employees remained for a long time, sometimes for decades. This loyalty might seem remarkable, because the salary levels at ARE were not particularly high (data on salaries have not been found, except for the year 1978, when they were below the average salaries of factory workers).Footnote 69

Two possible explanations for personnel choosing to remain at ARE for a long time can be proposed. First, the low salaries may have been compensated for by other benefits. ARE was generous with perks such as travel to study and sales travel to exotic places, as well as advertising courses and other education (sometimes during work hours, even if the courses were in non- work-related subjects), and provided generous expense accounts. Further, the stable customer base, and thus relatively secure employment, likely appeared attractive.

Second, personnel may have opted not to change employers or start their own businesses because the specific competency around the Labour movement that they held was not directly transferable to other agencies.

The End

At the beginning of the 1990s, the Social Democratic Party decided that it would no longer participate in commercial activities. The driving force behind this decision was party chairman Ingvar Carlsson (prime minister, 1986–1991 and 1994–1995), who expressed concern that the party’s involvement in commercial activities was too risky.Footnote 70 Carlsson’s opinion probably reflected a broader concern that, as the previous political advantages were gone, the reasons for continuing party ownership of commercial businesses were also gone.

Companies owned by the party or the labor union movement were largely sold, dismantled, or adapted to the open market and separated from their ties to the Labour movement. Several companies also went bankrupt.

The advantages that several of these companies had because of their close connection to a party that almost defined the state became severely curtailed because of new laws on public procurement in 1986 and 1994 and the change of power in 1991 when the Social Democratic Carlsson government was replaced by a center-right coalition led by Carl Bildt. Regardless of whether they were targeting private consumers or the public sector, the companies had a hard time retaining their market shares. Simultaneously, a change of values and attitudes among the population and increased competition caused the market conditions for companies within the Labour movement to deteriorate. Long gone were the days when Social Democratic voters could be assumed, out of loyalty to the Labour movement, to also buy their groceries at KONSUM stores, fill their fuel tanks at OK, and go on vacation with RESO.

For ARE, these difficulties initially meant that it chose to consolidate its creative advertising activities. In 1991, ARE Idé 1 and ARE Idé 2 merged into ARE Annonsbyrå AB, with Harald Ullman as president of the new company. Ullman had a long history within the Social Democratic Party and had been president of ARE Idé 2 since 1983; among other projects, he had been responsible for the party’s election campaign in 1985. At the beginning of the 1990s, the agency was one of the country’s largest, with a turnover of SEK 92 million and total commissions of approximately 25 million.

In 1990, ARE was contacted by the French advertising group JCDecaux, which wanted to buy the company. The sale did not occur at the time, but the companies cooperated regarding advertising space on street objects.Footnote 71

In 1993, Kjell Hemrell, a business executive and former management consultant who had previously managed restructuring of companies within the Swedish Cooperative movement and the conglomerate Nordstiernan, was appointed president with an explicit mandate to turn ARE into a pure transit and outdoor advertising company and dismantle other activities.

The previous year, ARE had reported a net loss of SEK 90 million. The reasons were largely costs attributable to failed international ventures. At the same time, large parts of ARE’s accumulated profits had been used to cover shortfalls among the A-pressen of the Labour movement, which produced liquidity problems for the company.

Hemrell sold or dismantled companies at a brisk pace. In 1993, the advertising agency was split into three parts, one in Stockholm, one in Gothenburg, and one in Malmö, and was sold to the directors. At the same time, both the printer Novaprint and Svenska Gallupinstitutet (a polling institute) were deregistered.Footnote 72

On March 7, 1997, the company was finally sold to JCDecaux for SEK 182.5 million.Footnote 73 The price for ARE at the time of sale may appear low, considering that the equity in 1990–91, when JCDecaux first wanted to buy the company, was approximately SEK 200 million and the turnover almost SEK 500 million.Footnote 74 Since that time, however, ARE had sold the advertising agency part of the business and liquidated or sold a number of smaller subsidiaries. The most important explanation for the decrease in the value of the group was that the owners during the 1990s had used ARE’s assets to cover losses within the newspaper and magazine empire of the party. In 1991, the Social Democratic Party transferred its shares in ARE, as well as its shares in the Labour movement newspapers and magazines, to the new company Media Invest.Footnote 75 Within as little as a year—at which time the newspapers were at the point of bankruptcy—ARE had paid out SEK 120 million. Contributing to the lower price was almost certainly the fact that ARE, when the Social Democratic Party’s position as the dominant party was in question, could no longer count on being the beneficiary of any political advantages.

Financial Development

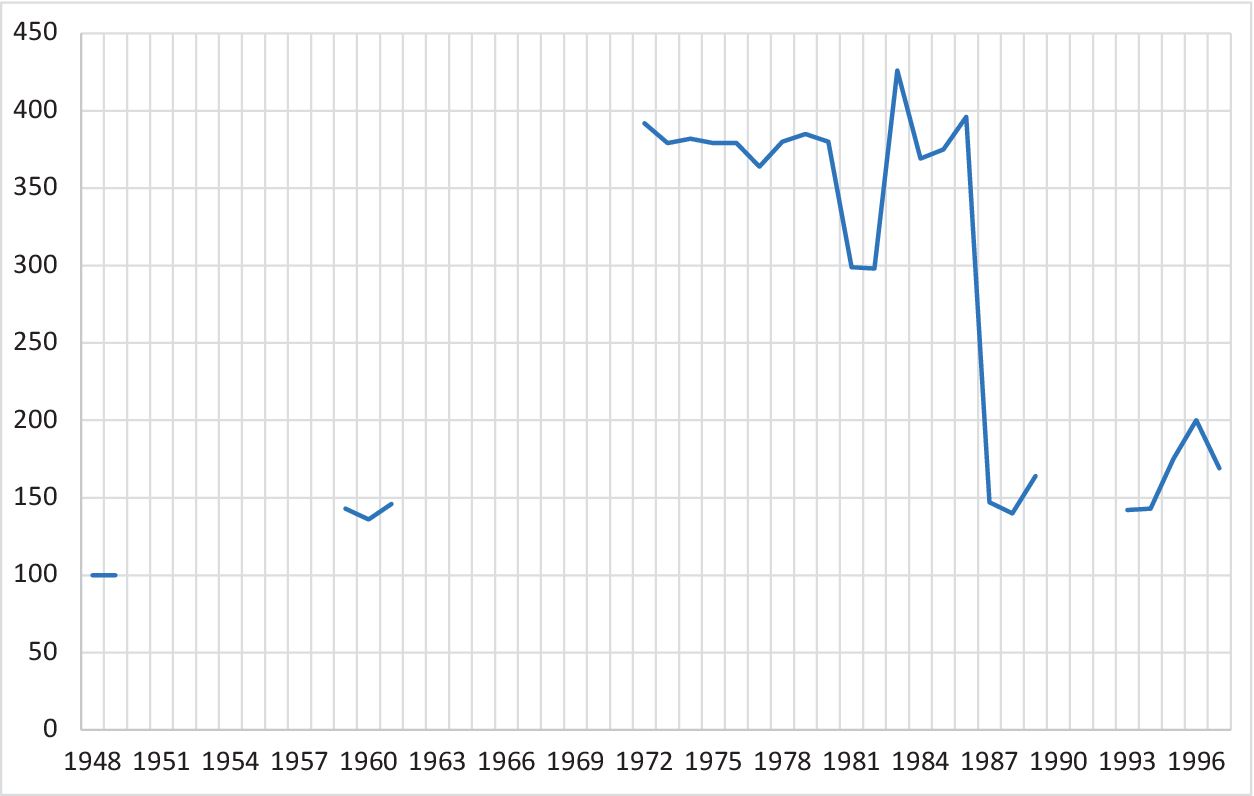

From the start, the company grew very quickly and after less than a year, it had one hundred employees (see Figure 1). At this time, the activities were more or less exclusively the sale and establishment of advertising boards and the painting and gluing of advertisements—not a very advanced type of work. During the 1950s and 1960s, the company expanded within the advertising agency arena and through major acquisitions of companies in the outdoor and direct mail areas. Thus, the number of employees grew rapidly, but numbers for the entire group are not available until 1971, at which time the group had 392 employees.

Figure 1 Number of employees of Folkrörelsernas Programaktiebolag/Folkreklam/Förenade ARE-bolagen, 1947–1997.

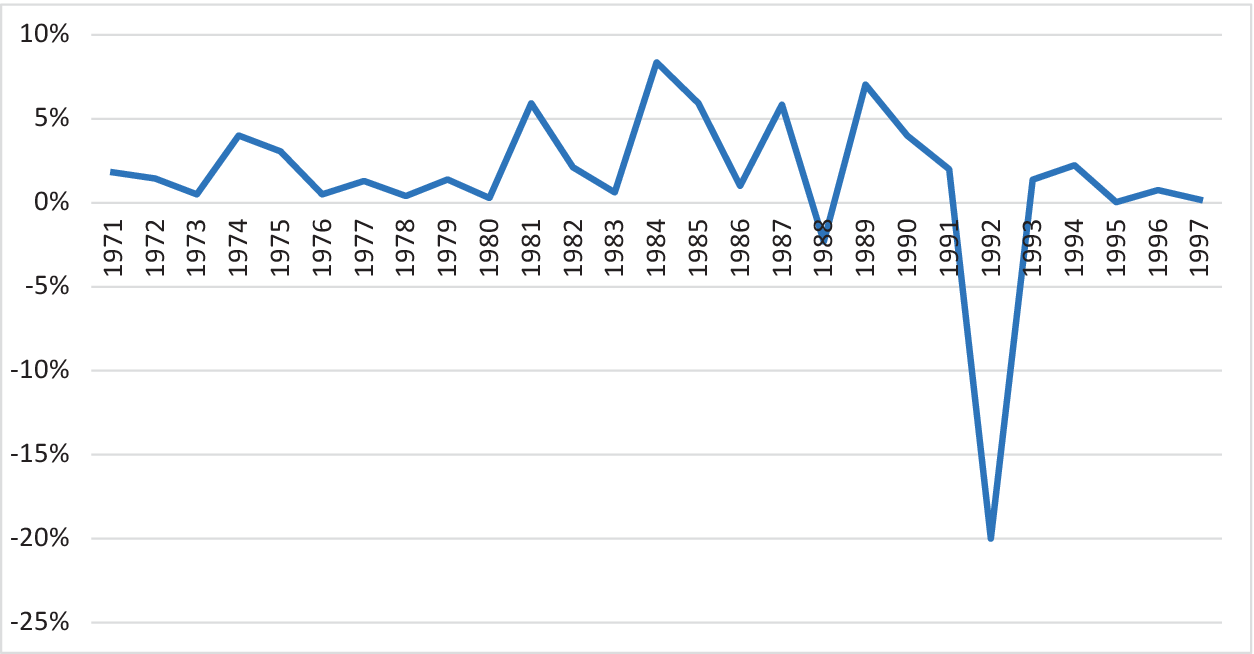

ARE’s maximum number of employees was 429 in 1983. The number of employees involved in advertising agency activities was fairly limited for a long time. In 1962, seventeen people were employed at NU-reklam (which at the time comprised all the agency activities), and in 1986, ARE Idé 1 had seventeen full-time employees in Stockholm and four in Gothenburg and ARE Idé 2 had twelve employees.Footnote 76 The number of employees increased until the mid-1980s; after that, the elimination of divisions reduced the number of employees. At the time of divestiture, the advertising agency business had approximately one hundred employees. The divisions that were sold or shut down do not seem to have affected the profitability, which was at its highest during this very period (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Net margin for the ARE Group, 1971–1997.

The development of profits, however, did not follow the same pattern as growth in number of employees. Net margin was at its highest in the early 1980s but decreased significantly at the end of the 1980s.

In 1988, the company showed its first small loss, which was followed by a major loss in 1992, a net margin of minus 20 percent; the loss was attributed to unsuccessful investments in outdoor advertising in Norway and Finland, and the SEK 120 million write-off due to the forced merger with the Social Democratic A-pressen media group.Footnote 77 The reported profits are probably understated, as the party regularly used ARE to cover party expenses; that is, ARE covered at least part of the costs for party congresses and did not charge the Social Democratic Party market prices for advertising.Footnote 78

The Relationship with the Social Democratic Party and the Impact of Party Ownership

During the entirety of the group’s existence, ARE was heavily reliant on clients from the Labour movement; this was particularly noticeable within the advertising agency part of the group. Dependence on a limited number of clients is nothing unique in the advertising industry. Many advertising agencies have one or several large customers with whom they have a long- standing relationship. The difference here was ARE’s largest customers were the owners, the Social Democratic Party, and organizations close to that party; thus, ARE could count on these customers not conceivably going elsewhere.

The connection to the Social Democratic Party also affected the structure of the company. The advertising agency activities were separated into two parts, ARE Idé 1 (earlier NU-reklam) and ARE Idé 2 (earlier ARE Film). ARE Idé 2 was totally focused on customers within the Labour movement and from time to time functioned as the de facto information department of the Social Democratic Party. During the election campaigns, the agency could more or less use the election budget as it saw fit, and the staff therefore had a very large influence over the party’s campaign efforts. ARE Idé 2 was also staffed almost exclusively with people active in the Social Democratic Party. Enn Kokk, who for many years was information manager of the Social Democratic Party, explains that it was an advantage that those who designed campaign advertisements understood the reasoning and culture of the party. This supposed advantage outweighed the outside perspective and the new ideas that the party could have obtained from an external agency, he claims.Footnote 79 Such a close relationship, however, has obvious negative sides. It was likely not possible for the party to select another agency for its election campaigns even if it was dissatisfied with the quality or creativity of work produced by ARE. Such a decision, even if it could have been defended from the perspective of creativity, would have damaged the economy of the agency (and thus indirectly the economy of the party). One further advantage in this context—even if it is unclear how much weight it was given—was that the Social Democrats, by having their own advertising agency, reduced the risk that information about the planning of election activities would leak. This extra level of security, in turn, made it possible for the party to involve the agency differently than it could have involved an independent commercial advertising agency.

Due to ARE’s dominant position, even competing political parties—the Conservative Party, the Liberal Party, and the Centre Party—were customers of ARE. Because these parties bought advertising space from ARE, the Social Democrats must have obtained firsthand information about how the other parties would distribute election resources and, indirectly, information on campaign strategy. A large investment in outdoor advertising in a certain municipality would, for example, indicate that the municipality had priority in the election planning of the party. In theory, the ARE’s dominant position in certain advertising markets also enabled the Social Democrats and the Labour movement to prevent their political adversaries from spreading their messages, because ARE could impede advertising that it considered unsuitable—or claim that the space was unavailable.Footnote 80 However, it has not been possible to find any examples of, for example, other political parties being formally prevented from spreading their messages; on the contrary, the other political parties were frequent customers of ARE. Controversies did occur, however. The Conservative Party—the main competitor to the Social Democratic Party—had just before the 1994 general election bought advertising space in the Stockholm metro from ARE. However, no posters were installed on the billboards. The reason—as stated by ARE in the media—was that the bill posters refused to show up for work, and due to the training needed to work in the metro system, no replacements could be found. This was viewed by the Conservative Party as sabotage of their election campaign.Footnote 81

The theoretical ability of ARE to restrict political opponents’ access to advertising space could be viewed in contrast to the official history of the company. When representatives of ARE wrote their own histories of the company, they highlighted the risk that organizations in the Labour movement would be excluded from commercial advertising boards as a contributing reason for the creation of the company. The company’s then-chairman of the board, Nils-Gösta Damberg, wrote in the annual report for 1980 that the reason Social Democrats needed to own advertising boards was they had been “more or less completely shut out” from “media” by corporations, and that ARE had “broken a monopoly.”Footnote 82

However, these reasons are never mentioned by Sven Andersson (the only one of the founders who has written about the creation of the company). Instead, Andersson highlights the business skills and vision of Sven Rydstedt. Through the fairgrounds and community centers, the Labour movement had access to unused advertising space placed in locations where many people gathered. Limited access to advertising boards is also not mentioned as a reason in the minutes of the founding or the minutes from the executive group of the Social Democratic Party, which made the decision to invest in the company. Instead, the minutes refer to a commercial venture that is based on utilizing the preferential access to advertising space that the Labour movement had.Footnote 83

The ambition right from the beginning was for ARE to become Sweden’s largest advertising company. “If you hang a billboard in every community centre [Folkets hus] and put an advertising pillar in every fairground [Folkets park], you get the country’s largest advertising company, and you can offer the most widespread advertising service that can be obtained in this country,” Rydstedt said, according to Andersson.Footnote 84

Just how important the connection to the dominant Social Democratic Party was for the development of the company is impossible to specify in detail, but an examination of its activities and list of customers indicates that this relationship was most likely a significant advantage. First, the acquisition of advertising space was a highly politicized process. The providers of advertising space, whether space inside or on buses and streetcars or sites to erect advertising pillars or billboards, were nearly exclusively cities and municipalities, county governments, or municipally owned or county-owned companies. Second, the government agencies, counties, and municipalities constituted an important fraction of the company’s customers. Here, the advantages of being owned by the Social Democrats were obvious, especially because of the access to certain advertising spaces. An independent firm would most likely have had a harder time obtaining the advertising space that was made available by the community centers and fairgrounds run by the Labour movement—even though it likely would have been possible. ARE also had access to the bulletin boards belonging to the labor unions in workplaces, which ARE called “Fabriksreklam” (factory advertising).Footnote 85

It was only for a few years at the end that publicly owned entities had to adhere to the law of public procurement; during most of the company’s existence, there were no impediments to Social Democratic managers of public entities or municipal councilors using the party’s own advertising agency when they needed an advertisement or advertising space.

Another advantage for ARE was that customers in the municipalities and public sector knew about it. Even if it was not said openly that ARE should be used as the advertising vendor by the municipalities, counties, or public authorities that were governed by Social Democrats, politicians often knew only about the ARE agency. This association was amplified by ARE in connection with Social Democratic Party activities such as Kommundagarna (municipal days; a gathering of elected municipal politicians), when it was given time and opportunity to present itself. The strong position of the company in outdoor advertising also contributed to the public sector buying its advertising services.Footnote 86

A complete list of clients is not available, but important clients during the period 1947–1963 are listed in the 1972 annual report. The list includes primarily clients from the public sector and from the Labour movement.Footnote 87 It should be noted that public sector advertising (with the exception of advertising by state owned companies) was very rare in Sweden before the late 1960s.Footnote 88 From the 1960s onward, some printed matter has been preserved that indicates that the creative production was performed largely for public entities and customers associated with the Labour movement.

Even though the owners rarely interfered with the daily operations, the president was always recruited from the Social Democratic Party organization. Therefore, the company leadership had considerable autonomy. Bertil Öster explained that the acquisition of a company, at least during Arvid Arvidsson’s time, did not involve the company board of directors; instead, Arvidsson and Öster handled such issues, sometimes after tips about suitable objects from various division managers.Footnote 89 Because the acquisitions were never financed by borrowing money and were always paid for in cash, no additional input was necessary. Any explicit strategy for how such development should be approached did not exist until Kjell Hemrell became president in 1993 and was given the task of streamlining the company to focus on outdoor advertising. This change was due to a specific directive from the owners. Additionally, the bailout in 1992 of A-pressen, the Social Democratic newspaper group, was the result of a directive from the owners.Footnote 90

Many who assumed high positions in the Social Democratic Party had previously worked for ARE or had been on its board of directors, including ARE cofounder Sven Andersson (later party secretary, minister of defense, minister of communications, and foreign minister); party secretary Sven Aspling; party treasurers Nils-Gösta Damberg, Allan Arvidsson, and Ernst Nilsson; and cabinet ministers Rune Molin, Sten Anderson, Ingela Thalén, and Thage G. Peterson (later also speaker of the parliament). To what extent ARE had functioned as a launching board within the party is not clear. In some cases, the time at ARE came early in someone’s career, for example, Ingela Thalén and Sven Andersson. In contrast, some board members, for example, Sven Aspling, Sten Andersson, and Rune Molin, were not appointed to the ARE board until they had reached senior positions within the Social Democratic Party.

The party treasurer traditionally had a seat on the board. This association was only to be expected, because ARE had great economic value to the party. Most often, the party treasurer was the chairman of the ARE board, but both Allan Arvidsson and Ernst Nilsson were presidents of the company.

ARE also had a special relationship with the Swedish war information organizations during the Cold War. Both the Swedish War Information Service and ARE were founded under the supervision of Sven Andersson, and a number of workers in the information service, such as Sören Thunell, Sven O. Andersson, Folke Allard, and Kjell Aggefors, among others, had previously held positions at ARE. In addition, personnel at ARE were assigned positions within the War Information Service in case of war, which gave the company a certain advantage as a group that had been selected and passed the security clearance process of the Department of Defence. This association was seen as a seal of quality that opened the door for new assignments.Footnote 91

Because Sweden is a small country, the close connections between the advertising agency belonging to the Labour movement and official and semi-official, often corporatist, entities can of course be explained by the fact that there simply was a very limited number of suitable and interested candidates for various positions. Another explanation is that these people were part of Sven Andersson’s personal network.

Advantages as a POE

A central question is how ARE managed to become one of the country’s leading advertising groups and completely dominate the outdoor advertising arena.

Several institutional factors were likely involved. Regarding the advertising agency activities, ARE’s success was probably mainly a matter of the power of the Social Democratic Party. Through the strong position of the party, the agency could obtain assignments not only from the various organizations and companies within the Labour movement but also from the public sector. These connections produced a stable revenue stream and reduced the cost of sales. Before the introduction of comprehensive public procurement laws, there was no requirement that services purchased by the public sector should be subject to competition, even if it was the practice to request bids from several vendors.Footnote 92 Using the party-owned advertising agency was likely the obvious choice for many Social Democratic politicians—not necessarily to favor the agency, but because ARE was the only agency they knew. At the same time, within the Labour movement, there was a consensus that if you had your own advertising agency, you should use it.Footnote 93

On the outdoor media side, the proximity to political power likely played an important role in obtaining advertising space. Because the owners of such space were primarily municipalities and municipally owned companies, political contacts plausibly both simplified the possibility of obtaining advertising space and affected the price paid for it. These benefits were likely greatest during the early years of the agency, because they gave the agency advantages that were otherwise given only to established advertising companies.

The combination of owning the medium, that is, the billboards, and producing the advertisements gave ARE the opportunity to increase its sales, as it was reasonable to offer the customers who wanted to buy advertising space help with the design of the advertisements.

Another factor was the prohibition against commercials on TV and radio, which theoretically was in force until TV4 was licensed to broadcast commercial TV with advertising through the terrestrial network in 1992, followed shortly by the deregulation of the radio and TV market in 1993.Footnote 94 Although TV3 had aired commercials to a Swedish audience via London since 1987, and the local radio station Radio Nova in Vagnhärad had broadcast commercials since 1990, an insignificant proportion of advertising budgets went to radio and TV before 1992–1993. However, with the opening of radio and television for commercial advertising, outdoor adverting expenditures fell both as a share of total advertising spending and in absolute terms.

It is, of course, difficult to determine the importance of each factor, but one indication is that the agency generated its first losses at the beginning of the 1990s, when conditions changed. At the beginning of the 1990s, the Social Democrats lost power both nationally and in many municipalities (including Stockholm and Gothenburg), and the new public procurement laws were passed in 1986 and 1994.Footnote 95

The loss of SEK 90 million in 1992 can, however, be attributed to the failed investments in outdoor advertising businesses in Finland and Norway and the bailout of the A-pressen media group. The latter should not be counted as a loss but rather as a form of dividend, because the party also controlled the A-pressen group. On the other hand, the international ventures highlight the main point made in this paper—ARE’s success was based on its ability to exploit political advantages connected to the power of the Swedish Social Democratic Party. The investment in outdoor advertising in other countries was intended to compensate for an expected decline in outdoor advertising in Sweden, but as ARE did not have any political advantages outside Sweden, these ventures failed miserably. The loss of political advantages probably affected the price paid by JCDecaux. Without the connection to the dominant party in Sweden, ARE was an ordinary outdoor media group that was not very well managed. As a result of the failed foreign ventures and the use of the company to cover losses made in other companies within the Labour movement, ARE had been emptied of most of its assets.

Concluding Discussion

An operation such as ARE would probably not have been possible without the Social Democratic Party as the owner. The company had available both a significant customer base in the business empire of the Labour movement and advertising space that other companies could not gain access to.

The fact that ARE owned the only advertising agency of importance outside the cartel covering the print advertising market until 1965 is likely explained by the availability of customers through the ownership link. This link may also have contributed to the dominant position of the company in the outdoor advertising market in the 1980s.

Preferential access to advertising space on municipal property and in public transport systems was likely the most important factor. For an outdoor advertising company, access to boards or pillars (or transit network sites) at advantageous rates is a critical success factor.

Even the company’s decline—and fall—was likely largely a result of the ownership connection. During the first twenty-nine years of the company’s existence, the Social Democrats were in office without interruption. During the last twenty-five years, they were in opposition for nine years. When the Social Democratic Party could no longer count on being the dominant party, the rationale for ARE disappeared. When requirements for the competitive procurement of public advertising contracts and the provision of advertising space became standard, another advantage disappeared. Changes in the adverting market—the opening of radio and television for commercial advertising—probably helped seal the deal.

Insights from the history of ARE may also be used to draw more general conclusions, primarily on the importance of a dominant hold of government power for parties that operate commercial businesses. Without stable access to political power, most of the advantages disappear, and the operation instead becomes risky. The company might weather a term with the owner-party out of power but cannot withstand repeated changes in government or a prolonged period in opposition.

The rarity of dominant parties in Western democracies could explain the limited number of successful POEs. The closest examples to the Swedish Social Democratic Party are probably the Japanese Liberal Democratic Party, which ruled without interruption from 1955 to 1993, and the Canadian Liberal Party, which, save for seven years (1957 to 1963) and 1979–1980, ruled from 1935 to 1984. POEs are instead phenomena predominantly found in countries without a democratic history. In Western Europe, party-controlled cooperative businesses are usually the type of companies that have the greatest similarities with POEs. However, these are much less dependent on connections to ruling parties, even if some of them also exploit political advantages (often explicit or implicit exceptions from competition laws). Milbus are also not found in Western democracies, but instead are usually found in countries where the military—in lieu of a dominant political party—provides the necessary political stability.

The fact that successful POEs are dependent on the owner being a dominant political power could also explain why, despite exactly the same legal and market conditions, no other Swedish political party has built an advertising empire of its own. They should have strong incentives to do so. ARE’s strong position in the outdoor advertising market and temporary monopoly in some mass transit systems forced the other parties to buy media space from ARE if they wanted to use billboard or transit advertising in their election campaigns. This not only allowed ARE to profit from the campaign spending of parties competing with the Social Democrats but also gave the Social Democratic Party advance notice of the opposition’s advertising strategy.Footnote 96 In addition, the Social Democratic Party could avoid revealing their own advertising strategies to outsiders.

Furthermore, the dependence on the ability to exploit political advantages could explain why the international ventures failed. POEs, like Milbus, are based on the existence of advantages that almost certainly do not exist outside the home country; this would also put a limit on potential growth. The case here, ARE, provides further support of the previous literature on POEs in developing and nondemocratic countries. It also shows that, contrary to previous findings (e.g., by Abegaz), POEs might also be possible in stable democratic countries rather than only in fragile economies.

Despite the losses in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, ARE was probably a very good investment for the Social Democratic Party. However, it is a success story that can hardly be repeated outside the institutional and political context prevailing in Sweden in the second half of the twentieth century. ARE’s rise and fall should also, first and foremost, be viewed as a reflection of this development.