Introduction

Terms of endearment enjoy great popularity in all languages to express feelings such as affection and tenderness. The present paper concentrates on the use of these types of words in English. The Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary (henceforth the HTOED) serves as a valuable tool to identify the plethora of terms of endearment which became established in English over the centuries.

The present study is based on a lexicographical sample of 203 lexical items which are currently included in the HTOED. The HTOED project started as early as 1964 when the British historical linguist Michael Louis Samuels from Glasgow University suggested compiling a historical thesaurus based on the linguistic evidence of the OED, but arranging the data in a thematic network of semantically related words and phrases (Kay, Sylvester & Wotherspoon, Reference Kay, Sylvester, Wotherspoon, Kay and Sylvester2001: 173). Led by a team of linguists, comprising Christian Kay, Jane Roberts and Irené Wotherspoon, the HTOED had been compiled at Glasgow University for over 45 years, before it was published by Oxford University Press in 2009.

The HTOED arranges lexical items in the OED according to subject areas in chronological order. It consists of two volumes. The first volume constitutes the thesaurus, and the second volume consists of an index of most of the vocabulary items listed in the thesaurus. Its digital version can be searched via the OED Online. It is directly linked to the linguistic documentary evidence offered by the OED and makes it possible, for instance, to examine the entire sense extent of a particular word. Allan and Kay (Reference Allan, Kay, Kytö and Pahta2016: 222) draw attention to the fact that

The combination of HTOED with the more detailed information about individual words available in the OED makes a powerful tool for lexical analysis, especially when reinforced by the increased availability of historical online corpora large enough to enable lexical research by allowing further scrutiny of contexts [ . . . ]

In the present study, the different terms of endearment were retrieved from the HTOED in the summer of 2020. Apart from the HTOED, the rich documentary evidence in the OED Online was consulted, in order to get a comprehensive overview of the etymology, meaning and usage of the various terms of endearment in English. This has so far been neglected in existing studies.

Terms of endearment in the HTOED

The thematic categorization of the terms of endearment has been established as follows in the HTOED: ‘the mind > emotion > love > terms of endearment.’ As is apparent, the mind constitutes the overriding domain, which includes lexical entries related to emotions. Emotions also encompass a variety of subcategories, including love terms. The field of love, on the other hand, comprises terms of endearment apart from additional lexical domains.

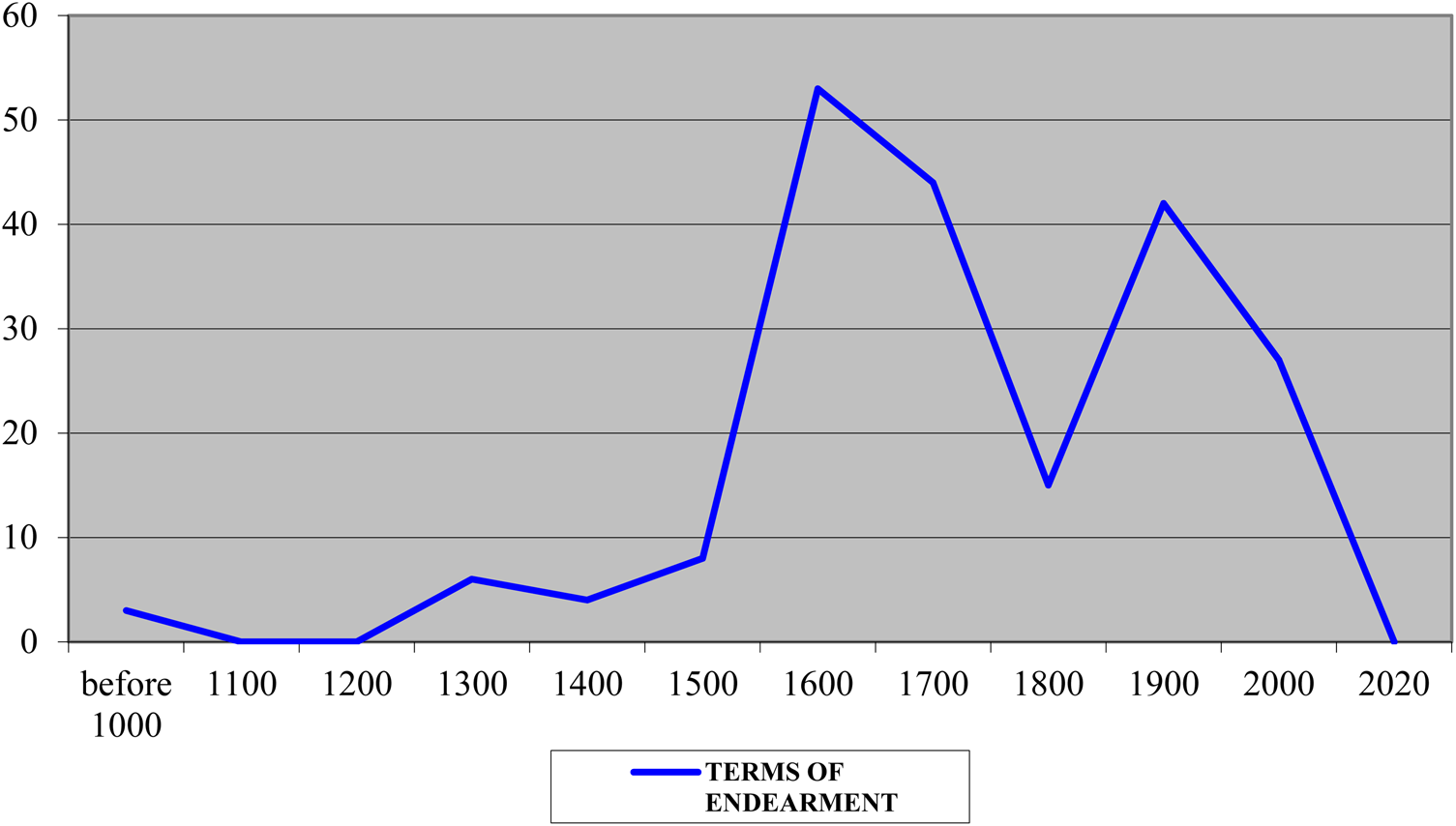

As mentioned before, the number of terms of endearment which can be found in the HTOED totals 203 lexical entries. The following list gives an overview of the numbers and proportions of the terms of endearment down the ages. Some illustrative examples of terms of endearment have been provided for each century (see Figure 1).

(1) Before 1000 (three lexical entries, i.e. 1.5%), e.g. darling (circa 888).

(2) 1201–1300 (six lexical entries, i.e. 3.0%), e.g. dear (circa 1230); sweetheart (circa 1290).

(3) 1301–1400 (four lexical entries, i.e. 2.0%), e.g. sweet (circa 1330); honey (circa 1375); dove (circa 1386).

(4) 1401–1500 (eight lexical entries, i.e. 3.9%), e.g. cinnamon (circa 1405); honeycomb (circa 1405); love (circa 1405); daisy (circa 1485); mate (circa 1500).

(5) 1501–1600 (53 lexical entries, i.e. 26.1%), e.g. honeysop (might have been first recorded in English in circa 1513); mouse (circa 1525); butting (about 1529); beautiful (1534); lad (1535); soul (circa 1538); heartikin (1540); mully (might have been first recorded in English in 1548); lamb (circa 1556); ding-ding/ding-dong (1564); golpol (1568); mopsy (1582); ladybird (1597); duck (1600); sparrow (circa 1600).

(6) 1601–1700 (44 lexical entries, i.e. 21.7%), e.g. honeysuckle (1613); pretty (1616); dear old thing (about 1625); frisco (about 1652); mon cher (1673); cherub (1680); deary (1681); lovey (1684); nug (1699).

(7) 1701–1800 (15 lexical entries, i.e. 7.4%), e.g. dovie/dovey (1769); sweetie (1778); lovey-dovey (1781); lovely (1791).

(8) 1801–1900 (42 lexical entries, i.e. 20.7%), e.g. ducky (1819); acushla (1825); chick-a-diddle (1826); honey child (1832); bubba (1841); honey-bunch (1874); bach (1889); diddums (1893); honey baby (1895); prawn (1895); hon (1896); so-and-so (1897); old crumpet (1900); pumpkin (1900).

(9) 1901–2000 (27 lexical entries, i.e. 13.3%), e.g. honey-bun (1902); Schatz (1907); old bean (1917); treasure (1920); old (tin of) fruit (1923); sport (1923); sugar (1930); baby cake (1949); bubele (1959); lamb-chop (1962); yaar (1963); John (1982).

Before 1201 there are hardly any terms of endearment in English. An exception is darling, which has been recorded in English since circa 888 (see OED2). Their numbers increased slightly from the 13th century onwards and were at large over the course of the 16th century. In the 17th and 19th centuries, too, a comparatively large number of terms of endearment are documented in the HTOED. An exception is the 18th century, where the numbers fall sharply. This trend continues in the 20th century, where a decrease in terms of endearment is manifest. In the 21st century, no terms of endearment have been so far included in the HTOED.

Figure 1. Graph showing lexical entries for terms of endearment by century in the HTOED

The HTOED is a rich resource which encompasses a plethora of terms of endearment. It includes terms that lovers use for each other (e.g. darling, sweetheart, treasure), names for the female partner, among them several terms from the animal kingdom which are used in a figurative meaning, such as dove, mouse, lamb and ladybird. There are also a number of (chiefly colloquial) expressions employed by men, such as lad and old bean, and terms of endearment for children (e.g. cherub, diddums, mopsy, chick-a-diddle). In addition, the HTOED lists affectionate forms of address for elderly persons, comprising terms confined to informal usage, such as dear old thing.

Needless to say, most terms of endearment show highly positive connotations, such as darling, honey, dear, love and the diminutive affectionates deary and lovey. Yet we also find some words among the HTOED entries that may occasionally have slightly negative implications. This holds for the common term sweetheart, for instance, which is in some cases used ironically or disparagingly, as the following usage examples included in the OED3 reveal:

– ‘1890 H. Caine Bondman iii. vi ‘Ot's the name of your ‘ickle boy?’ ‘Ah, I've got none, sweetheart. ‘’

– ‘1977 F. Parrish Fire in Barley viii. 82 Try harder, sweetheart, or I'll plug you in the guts.’

Similarly, the use of the term so-and-so does not exclusively have positive implications. It is either documented as a euphemistic form of insult for an individual or occasionally an object or, in a milder use, as a tender form of address. This is corroborated by the following example retrieved from the OED2:

– ‘1977 B. Pym Quartet in Autumn i. 9 “Hoping to get off early, lazy little so-and-so,” said Norman.’ (OED2)

Obviously, metaphorical uses may reflect specific characteristics which can be seen. When a person is named as a variety of animal because of a particular property, for instance, it seems to have something to do with a common feature or quality that is thought to associate the person and the animal. The different HTOED items contain several animal terms of endearment, such as dove, lamb, duck, sparrow, prawn and mouse (now archaic). Among the animal names, there are also terms to which hypocoristic suffixes (e.g. -y, -ie) were attached to form affectionate diminutives: dovie with its spelling variant dovey (also as post-modifying noun in lovey-dovey) and ducky. The metaphorical use of animal names for individuals could perhaps be partly due to the influence of Shakespeare's plays, which may have contributed, to some extent at least, to the spread of these types of words in English. In his plays, Shakespeare included a plethora of animal names in direct speech and descriptions of pecularities of his characters (see also Boehrer, Reference Boehrer2016). In fact, several metaphorical terms of endearment from the animal kingdom are recorded in the relevant meanings in Shakespeare. An example is dove, which occurs in the corresponding sense in Hamlet:

– ‘1604 W. Shakespeare Hamlet iv. v. 168 Fare you well my Doue.’ (OED2)

Further examples are lamb and ladybird, which are also documented as affectionate forms of address for a female sweetheart in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet:

– ‘1597 W. Shakespeare Romeo & Juliet i. iii. 3 What Lamb, what Ladie bird . . . Wher's this girle?’ (OED3)

From the linguistic data in the OED3 it becomes apparent that ladybird can also have negative implications. It may also be used as a depreciative term for ‘a kept mistress; a lewd or wanton woman; a prostitute’ (OED3). OED3 examples are:

– ‘1699 B. E. New Dict. Canting Crew Lady-birds, Light or Lewd Women.’

– ‘1881 A. Trumble Slang Dict. N. Y., London & Paris 20 Lady bird. A kept mistress.’

The OED3 tells its users that these senses are rarely attested in present-day English.

A number of affectionate terms represent transferred uses of names for flora and fauna. For examples, honeysuckle, originally denoting a variety of plant producing sweet-smelling flowers, and daisy, the name of a flower used as a term expressing admiration. The latter has become disused in English (see OED2).

Some culinary terms are used in a transferred or figurative use, functioning as tender forms of address. Examples are the common term pumpkin and lamb-chop. Of these, pumpkin originated in American English as an affectionate form of address (see OED3). As to lamb-chop, the use of the word in its literal culinary meaning is prevalent in English. Examples of its metaphorical use with reference to an individual are scarce. The latest OED2 quotation reflecting this sense dates from 1962:

– ‘1962 E. Lucia Klondike Kate ii. 40 Mrs Bettis was persistent and her daughter was quite a lamb chop, so he finally agreed.’

Most of the culinary terms which can function as terms of endearment are associated with sweetness, such as cinnamon, baby cake, sugar and honey. The use of honey (also abbreviated as hon in colloquial English) as a pre-modifying constituent in noun phrases and compounds is comparatively productive, to coin terms reflecting tender affection, such as honeycomb and honeysop, both of which are now only rarely used as terms of endearment in current English, honey-bunch, honey-bun, honey baby and honey child. Of these, honey baby was originally confined to American usage, as in:

– ‘1895 Trenton (New Jersey) Times 8 July 6/1 Kissin it to make it well, are ye? God bless lilley honey baby.’ (OED3)

According to the etymological information given in the OED3, honey child has its origins in Irish English. It is now mainly documented as a term for ‘[a] sweetheart, a darling’ (OED3) in regional Southern and African American English, where it primarily occurs as a type of address (initially predominantly to a child). OED3 examples are:

– ‘1976 Ebony Jr.! Dec. 42/1 “Let's sit down, Honey Child,” his grandma said in a choked voice, as she looked at his frightened face.’ (OED3)

– ‘2006 Guardian (Nexis) 11 Dec. 20 Honey child, I always knew you'd come to me one day.’ (OED3)

Some terms of endearment are confined to regional Englishes, such as acushla, a designation of a sweetheart in Irish usage. According to the OED3, it reflects the Irish form a chuisle, which may itself be a shortening a chuisle mo chroí/a chuisle mo chroidhe (now obsolete), which can be translated as ‘my heartbeat’, literally ‘pulse of my heart’. Additional examples of terms occurring in regional or national varieties of English are John, bach, bubba, sport and yaar. Of these, John is one of the very few examples of familiar forms of address which are derived from a proper noun. It serves as a general way of addressing any male individual in colloquial British English, e.g.:

– ‘1982 A. Sayle (title of song) “Ullo John! Gotta new motor?”’ (OED3)

Bach, literally meaning ‘little’, has its origins in Welsh. The term constitutes a common address in Wales and its neighbouring regions, and it often placed after a proper noun. Examples from the OED2 are:

– ‘1916 C. Evans Capel Sion iii. 40 “A wanton bitch you are.” “Dennis bach, don't say!”’

– ‘1961 E. Williams George vi. 75 Look in your book, Georgie bach.’

Bubba may constitute a hypocoristic variant of brother, and it occurs ‘as a nickname or familiar form of address for any boy or man, and as a title preceding a name’ (OED3) mostly in regional American English. In its usage as a friendly manner of addressing someone, typically among men who are not acquainted with each other, sport is mainly documented in New Zealand and Australian English. Examples from the OED3 are:

– ‘1975 R. Beilby Brown Land Crying 80 “Come on, sport,” the doorman was saying patiently. “You can't stop here. You've had a skinful.”’

– ‘2004 Age (Melbourne) (Nexis) 30 July 3 (headline) Us, like Yanks? Fair go, sport!’

Yaar is the only example among the HTOED entries that serves as a term of endearment in Indian English. The word is confined to colloquial usage, where it is used as a familiar form of addressing a friend or companion, e.g.:

– ‘1967 Shankar's Weekly (Delhi) 12 Nov. 22/3 A fetching comedy that the teen agers will like in America and the class which looks up to them in India will applaud as “Wah, yaar!”’ (OED3)

Yaar reflects the synonymous Urdu yār, which is itself derived from Persian.

Among the lexical entries there are also some substantiated adjectives used as pet names: beautiful, lovely, pretty (typically in my pretty/my pretties), sweet and the corresponding affectionate diminutive sweetie. Obviously, these nominal uses reflect the positive characteristics and properties of the designated person which were originally described by the corresponding adjectival forms.

In the collection of terms of endearment recorded in the HTOED, we can also find some words derived from foreign languages which can be categorized as direct loans, i.e. borrowings which show no or only slight assimilation (in pronunciation, spelling etc.) to the receiving language. Examples are mon cher, a borrowing from French which translates as ‘my dear’, and Schatz, a term of endearing address which goes back to German. A look at the linguistic documentary evidence included in the OED2 suggests that Schatz is confined to German-speaking contexts in English, as in:

– ‘1907 E. von Arnim Fräulein Schmidt xlii. 174 The trumpeter and his Schatz sat quietly in the kitchen.’ (OED2)

Its German source Schatz shows a wider semantic scope than the borrowing in English: it translates as ‘treasure.’ As to the English word treasure, it has been used as a term of endearment since 1920, i.e. some years after the first recorded use of the corresponding German borrowing:

– ‘1920 K. Mansfield Let. 31 Oct. (1977) 194 But, my treasure, my life is ours. You know it.’ (OED2)

However, the OED2 gives no indication as to whether the meaning of treasure could possibly have been influenced by the German. It thus may well be that the relevant change in meaning represents an independent semantic development within English. There is also bubele, a borrowing from Yiddish. It is restricted to Jewish usage, where it is used as an affectionate variety of address, typically with respect to ‘a child or elderly relative’ (OED3), e.g.:

– ‘1968 Naugatuck (Connecticut) Daily News 21 Nov. 3 If you think this is going to be a megilla from a yenta, listen, bubele.’ (OED3)

Its Yiddish source bubele is ultimately derived from bobe ‘grandmother’ (see OED3).

A number of terms of endearment have become rare or obsolete. Examples are heartikin, an affectionate diminutive which translates as ‘little heart’, mulling and its possible derivative mully, now rare terms for ‘a sweetheart’, as well as golpol, butting, nug, frisco, ding-dong and ding-ding, which are equally no longer or only rarely used as tender forms of address. The etymological origin of mulling, golpol, butting, nug, frisco, ding-dong and ding-ding is not clear according to the OED. Mulling might have been formed on the basis of the verb to mull ‘to fondle’ and the suffix -ling (see OED3). As to golpol, it might perhaps be related to the word gold-poll (see OED2), butting might have been coined on the basis of butt, a species of fish (see OED3), and nug may have been influenced by pug (now disused), a pet name for an individual or sometimes an animal. According to the OED3, pug was also used to specify a type of toy, such as a puppet. Frisco might be a pseudo-loan from Italian, literally meaning ‘frolic’ or ‘freak.’ The latest OED2 example of its usage as a tender form of address dates from about 1652. As to ding-dong and its spelling variant ding-ding, the OED2 lacks any explanation for the usage of these forms as types of endearing addresses. The latest usage examples of these terms as pet names date from the 17th century, e.g.:

– ‘1602 W. Clerk Withals's Dict. Eng. & Lat. 61 My ding-ding, my darling.’ (OED2)

Conclusion

From the present study it has turned out that the HTOED is a valuable source, including manifold terms of endearment, ranging from expressions that couples use to address each other and affectionate forms of address in particular for women, among them a considerable number of terms for animals used figuratively, to familiar forms of address used among men, affectionate forms of address for children and elderly individuals. In addition, the HTOED encompasses a variety of pet names which are confined to regional or national varieties of English, as well as borrowed lexical items which function as terms of endearment.

Most of the terms of endearment recorded in the HTOED seem to be in full use. The latest word in this sample of lexical items is the aforementioned John, which has been documented as a familiar form of address since 1982. No terms of endearment have been so far recorded since the 21st century. The decrease of these types of words in recent decades might point to the fact that nowadays, speakers of English might be less creative with respect to the coinage of terms of endearment than they used to be.

JULIA LANDMANN (née Schultz) works as a lecturer in linguistics at the English Department at Heidelberg University. She has authored a number of investigations which concentrate on different language contact situations and their linguistic outcomes, such as the impact of French, German, Spanish and Yiddish on English. Julia is currently preparing a study about the dynamic lexicon of the English language from a socio-cognitive perspective. Her research interests focus on language contact, lexicology, lexical semantics and cognitive linguistics. Email: [email protected]

JULIA LANDMANN (née Schultz) works as a lecturer in linguistics at the English Department at Heidelberg University. She has authored a number of investigations which concentrate on different language contact situations and their linguistic outcomes, such as the impact of French, German, Spanish and Yiddish on English. Julia is currently preparing a study about the dynamic lexicon of the English language from a socio-cognitive perspective. Her research interests focus on language contact, lexicology, lexical semantics and cognitive linguistics. Email: [email protected]