1. Introduction

Colloquial Singapore English (CSE, commonly known as Singlish) is a linguistic variety used in Singapore, a Southeast Asian nation home to three major ethnic groups: the Chinese (74.35% of the citizen and permanent resident population), the Malays (13.43%), and the Indians (9%) (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2019). It is one of the best known post-colonial varieties of English and has been documented since the emergence of the field of world Englishes (e.g., Greenbaum, Reference Greenbaum1988; Richards & Tay, Reference Richards, Tay and Crewe1977). Linguistically, the grammar and lexicon of CSE are systematically imported from other non-English languages used in the island nation (Leimgruber, Reference Leimgruber2011). From a creolist perspective, it can be viewed as an English-lexifier creole that contains influences from Sinitic languages such as Hokkien, Cantonese and Mandarin, as well as Malay, Tamil and other varieties in the Singapore language ecology (McWhorter, Reference McWhorter2007; Platt, Reference Platt1975). Several distinct features across various levels of language have been investigated in CSE, including phonetics (Starr & Balasubramaniam, Reference Starr and Balasubramaniam2019), morphosyntax (Bao, Reference Bao2010; Bao & Wee, Reference Bao and Wee1999), semantics (Hiramoto & Sato, Reference Hiramoto and Sato2012), and pragmatics (Hiramoto, Reference Hiramoto2012; Leimgruber, Reference Leimgruber2016; Lim, Reference Lim2007).

In this paper, we investigate a feature of CSE that has received relatively little attention in the literature – the question marker is it. We first demonstrate how is it is used in standardized English (Section 2), before relaying previous insights and our initial observations regarding the use of is it in CSE (Section 3). From there, we state our goals, hypotheses and methodology (Section 4). This is followed by an analysis of CSE is it (Section 5) and a general summative discussion of is it and its development (Section 6). We conclude the paper in Section 7.

2. Standardized English is it

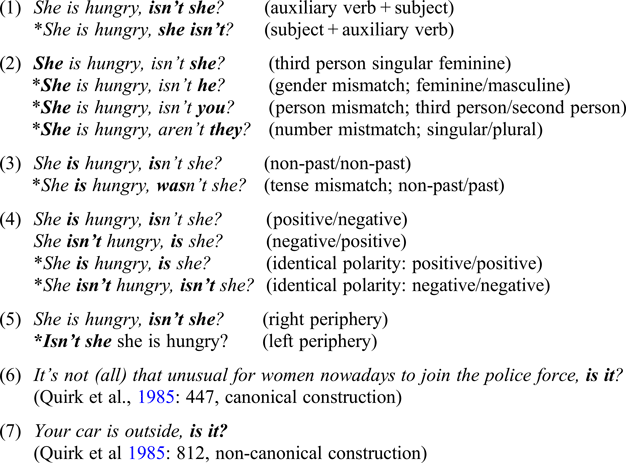

In standardized English yes-no questions, is it – as a single constituent or linguistic unit – seems to only function as a question tag. It takes one of two forms: canonical tags and non-canonical tags. Canonical tags are expected to conform to structural rules (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 810). First, they should comprise an auxiliary verb and subject, in that order.

Second, the subject/expletive of the tag must be a pronoun that is, by default, identical to the subject/expletive of the statement and that matches it in gender, person, and number.

The verb also must be of the same tense as the verb of the main clause.

Third, if the statement is negative, the tag should be positive, and vice versa.

Finally, the tag should be appended to the right periphery of the statement.

For example, in (6), the tag is it is characterized as canonical because not only does it consist of an auxiliary verb and subject in the correct order, the expletive, it, in the tag is identical to the expletive pronoun in the preceding statement. Further, the tag appears in the positive – the reverse of the preceding negative statement. And finally, the tag appears at the right end of the sentence.

Non-canonical tags, on the other hand, do not always need to have the auxiliary verb and subject/expletive (e.g., is . . . right?). They also might not follow the polarity rule (e.g., is . . . is it?). The is it tag in (7), for example, is classified as non-canonical because the statement and tag do not agree in polarity, even if all other conditions of a canonical tag are fulfilled.

Despite their differences, both canonical and non-canonical tags in English yes-no questions always appear clause-finally (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 810). Functionally, both tags are also used to express a verification function; however, non-canonical tags have additional functions that distinguish them from canonical tags (Columbus, Reference Columbus, Gries, Wulff and Davies2010). For instance, the use of the non-canonical tag yeah in British English is not only used for verification, but also to acknowledge the listener without meaning to elicit a response, among other functions (Columbus, Reference Columbus, Gries, Wulff and Davies2010).

A summary of the similarities and differences between the canonical tag and the non-canonical tag can be found in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison between canonical vs. non-canonical tags (✓= yes; ? = not necessarily)

3. What we know so far about CSE is it

Is it in CSE has been characterized by scholars as an invariant tag question, appended at the end of the question (Leimgruber, Reference Leimgruber2011; Wong, Reference Wong2014). Functionally, it differs from standardized English in that CSE is it does not imply that the speaker expects agreement, i.e., CSE speakers rarely use it to invite the listener to express their opinion (Wong, Reference Wong2014). Apart from functional differences, CSE is it is also structurally different from standardized English is it, based on data from the Singapore component of the International Corpus of English (ICE–SIN), a local corpus that was made available in 2002 as part of a global initiative with the goal of collecting material for comparative studies of English worldwide (Nelson, Reference Nelson2002). First, unlike standardized English where canonical tags (henceforth, polarity tags) are more commonly used (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 812), such usage is rare in CSE: only one out of 59 (1.69%) instances of the polarity tag is it found in ICE–SIN can be described as canonical (8).

Instead, non-canonical tags (henceforth, non-polarity tags) are widespread in CSE, taking up 91.5%, or 54 out of 59 instances of is it found in ICE–SIN. An example is shown in (9).

Third, based on observations from the ICE–SIN data and the authors’ observations of CSE, there seems to be a novel use of is it – that of a clause-initial yes/no question marker (henceforth, clause-initial is it).

The is it in both (10) and (11) does not function as a question tag because it is not syntactically located at the end of the clause. The is it observed also does not seem to be the result of a subject-auxiliary inversion operation, where the auxiliary syntactically moves from the preverbal position to the clause-initial position before the subject. This is because the it in is it is not the subject of the sentence e.g., in (11) – you is. Is it here instead functions as a single constituent that can be treated as an analog to the interrogative do-support construction (e.g., Do you think . . . vs. Is it you think…). This is a potential innovation in CSE that appears to be uncommon in the corpus (6.77%; four out of 59) but ubiquitous based on our anecdotal observations.

This preliminary investigation has uncovered two key observations. First, the distribution of polarity vs non-polarity is it question tags in CSE seems to be very different from standardized English – while the canonical tag is more frequently used in standardized English (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985), the situation is reversed in CSE where the non-polarity tag is more common. Second, there appears to be another as-of-yet unnoticed use of is it in CSE, where is it is found in clause-initial position. In the following sections, we empirically test these two observations using data from a newly compiled corpus, to see if they hold more generally of the CSE-using population. We also seek to identify the linguistic and social conditions that may play a role in CSE speakers’ use of is it.

4. Goals, hypotheses, methodology

In this paper, building on our anecdotal observations and findings in our preliminary corpus analyses, we first aim to establish the distribution of question-marking constituent is it in contemporary CSE. To fulfill this goal, we draw on the first version of the 3.6 million-word Corpus of Singapore English Messaging (CoSEM), compiled at the National University of Singapore (Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales, Hiramoto, Leimgruber and Lim2021). CoSEM is a sociolinguistic corpus of online text messaging data collected between 2016 and 2021. Each utterance in CoSEM is tagged with the following social metadata: sex (male and female), age (18 to 69), raceFootnote 1 (e.g., Chinese, Malay, Indian), and nationality (e.g., Singaporean, Malaysian). CoSEM comprises finger speech – or speech that is ‘less like the written language’ (Faulkner & Culwin, Reference Faulkner and Culwin2005: 182; McWhorter, Reference McWhorter2013), providing a novel approach to studying how CSE speakers use is it in a conversational context. Second, we aim to identify the linguistic, social, and orthographical conditions under which these question-marking variants are used; specifically, we adopt a statistical approach toward analyzing variation. From our results, we hope to shed some light on the development of is it in CSE.

Hinging on our initial observations, we hypothesize that the non-polarity is it and clause-initial is it constructions will be more frequently used compared to the polarity is it. We also hypothesize that pragmatic factors such as affect and rhetoricity will influence a speaker's choice of the is it variant, given studies reporting associations between pragmatic function and linguistic variables (Pratt, Reference Pratt2021; Siemund, Reference Siemund2018; Wong, Reference Wong2014). Specifically, based on our preliminary work and consultation with native CSE speakers in 2018, we hypothesize speakers will be more likely to use clause-initial is it if they are indexing ‘playful’ and ‘mocking’ affects and if they do not expect an answer from the addressee (i.e., in a ‘rhetorical’ context). We expect speakers to display an increased use of non-polarity tag is it in contexts that are not ‘playful’, ‘mocking’, and/or rhetorical.

We also hypothesize that certain variants will be used by certain speaker groups more than others. In general, we hypothesize that age, nationality, gender, and race will condition the use of CSE is it, as these factors have been found to correlate with other features of CSE (Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales, Hiramoto, Leimgruber and Lim2021; Leimgruber et al., Reference Leimgruber, Lim, Gonzales and Hiramoto2020). We did not find correlations between orthographical choice (e.g., is it, isit, izzit, issit) and the use of polarity and innovative is it in the preliminary data, so we hypothesize that orthography will not systematically condition is it use. A significant part of the variation in the use of orthographical variants will be attributed to factors such as individual preferences or habits regarding spelling conventions.

To prepare the data for analysis, we collected all tokens of is it in CoSEM before filtering out irrelevant instances such as singleton uses (e.g., Is it?) as well as instances involving auxiliary inversion (e.g., Is it dead?). After the initial selection process, there were a total of 1902 instances of CSE is it in the database. We then calculated the raw and relative frequency distributions of the different types of is it constructions (polarity, non-polarity, clause-initial). We fit a series of generalized linear regression models with logistic link function on our dataset in the R environment (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015; Kuznetsova, Brockhoff & Christhensen, Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christhensen2019; R Core Team, 2013), to test for the effect of these factors on one's likelihood to use a certain variant.

To test our hypotheses on the potential correlations between orthographic choice and is it use, we considered two salient orthographical features: the use of concatenationFootnote 2 and consonant choice. Concatenation refers to the absence of a character space between is and it, while consonant choice boils down to whether the CSE speaker uses s (e.g., is it, issit) or z (e.g., iz it, izit). Examples are presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Examples of orthographical variants

We included these two mutually exclusive binary variables in our modeling of CSE is it whenever possible.

To test our hypotheses on the conditioning effect of social factors on is it production, we analyzed the data in relation to the embedded social information of each utterance. Particularly, we analyze four variables – age, race, nationality and sex – by including them as potential predictors in our is it models. Age was included as a continuous variable (range = 18 to 69). Race, nationality and sex were included as binary categorical variables (i.e., Chinese vs. non-Chinese, Singaporean vs. non-Singaporean, male vs. female; see Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales, Hiramoto, Leimgruber and Lim2021 for more information regarding the social variables in CoSEM data). Through modeling, we attempt to find (statistically significant) correlations between particular social classes and variation in the use of is it.

To test our hypotheses on the effect of rhetoricity and affect, we asked three native speakers of CSE to provide judgements on the 1902 utterances containing is it. We asked them to code the data based on rhetoricity (i.e., whether an utterance is a rhetorical question) and affect (i.e., whether the utterance has certain affects attached to it). To facilitate their coding, the native speaker coders consulted the preceding and succeeding utterances for contextual clues. They were then instructed to code utterances in a binary format (i.e., ‘1’ for present, ‘0’ for absent). The coders were all Linguistics-major university students and they have been trained by the authors to ensure that their coding is as accurate as possible.

For rhetoricity, the native-speaker coders examined the utterances after the question containing is it. If a yes or no response immediately succeeds this statement, the question is coded as non-rhetorical (12a). Otherwise, it is coded as rhetorical (12b).

For affect, the coders examined the utterances surrounding the is it question to determine whether it has a ‘mocking’ or ‘playful’ affect. Although both affective meanings overlap, we distinguish between these two as follows. A question is coded as ‘mocking’ if it is deemed to be used by the speaker to make fun of someone or something in an ‘unpleasant’ way. A question is coded as ‘playful’ (or ‘jocular’) if it is judged to express lightheartedness intended for one's own or others’ amusement rather than be taken seriously. These two affective meanings were regarded as not mutually exclusive – a question can be just ‘playful’, just ‘mocking’, neither ‘playful’ nor ‘mocking’ or both, as illustrated in (13).

Note that only the preceding and succeeding utterances were considered when the coders made their judgments. This can potentially skew the results. For instance, in the case of making judgments for rhetoricity, the yes/no response may appear in utterances much later than the one immediately succeeding (e.g., the responder could be interrupted by another interlocutor in the group chat). In the case of affect, the coder might code an utterance as ‘non-playful’ even if the utterance is, due to the lack of evidence in the preceding and/or succeeding utterances. However, we decided to use this approach to simplify the coding process, with the intention to code more data. We hope that the quantity of data will compensate for any potential noise.

5. Findings and results

5.1 General distribution

We find all three types of is it constructions in CoSEM: polarity tag is it (14), non-polarity tag is it (15), and clause-initial is it (16):

Apart from the three aforementioned variants, we also find is it in embedded interrogatives without a complementizer (17), where is it seems to be analog to whether or not or if it is. This construction falls beyond the scope of our investigation of question marking, as sentences with this construction cannot be interpreted as yes/no questions, unlike the other sentences. We hope to examine it further in the future.

Table 3 summarizes the distributions of is it constructions in CoSEM.

Table 3: Distribution of is it constructions in CoSEM

Overall, we found several variants of CSE is it constructions. We now proceed to investigate whether age, sex, race, nationality, rhetoricity, and affect condition the use of these variants. Due to the relatively small number of tokens, we decided to use all the tokens for the analysis of variation. This meant not being able to control for sample size or proportion differences between social groups (e.g., discarding tokens belonging to one group to ensure balance): age groups (below 30 = 99%, above 30 = 1%), sex groups (male = 41%, female = 59%), racial groups (Chinese = 80%, non-Chinese 20%), nationality groups (Singaporean = 94%, non-Singaporean 6%). Although a balanced dataset is the gold standard, our unbalanced dataset should not pose too much of a problem for our analysis, as the statistical tests we employed account for it. Sample size is considered alongside magnitude of difference and variability in the data when deciding whether a correlation/effect is statistically significant (see Winter, Reference Winter2020: 159 for an in-depth discussion); that is, sample size is taken into account in our measure of (effect) confidence – the p-value.

5.2 Polarity vs. non-polarity

To determine the factors that influence CSE speakers’ choice of tags, we attempted to model the likelihood of using the non-polarity tag over the polarity variant using social factors. However, because of the lack of data for polarity questions (n = 3, see Table 2), we were not able to create a model nor were we able to comment on the development of is it in the context of polarity. The dominance of non-polarity tags over polarity tags in our data indicates that the use of non-polarity tags in CSE is stable.

5.3 Question tags vs. clause-initial is it

To determine the factors that influence CSE speakers’ choice of is it question marker, we modeled the likelihood of a CSE speakers’ use of clause-initial is it over the use of is it tags. We used the manually coded rhetoricity, affect, and orthographic choice factors in addition to the social factors mentioned earlier. We wanted to control for potential individual effects (individual variation) by modeling in random intercepts for participant/interlocutor. This was, however, not possible because there were insufficient is it questions per individual in the corpus. The resulting model showed an effect of rhetoricity, playful affect, age, and nationality on the likelihood to use clause-initial is it (Table 4). There was no evidence of mocking affect, race, sex, and choice of orthographical variants (i.e., concatenated/non-concatenated, s-/z-variants) correlating with the likelihood of using the innovative marker over question tags.

Table 4: Logistic regression results – likelihood to use the innovative marker over question tags (observations = 1,892, R2 = 0.049, no random effects, multi-level categorical variables coded using Weighted Helmert coding conventions, reference levels and statistically significant p-values in boldface, α = 0.05)

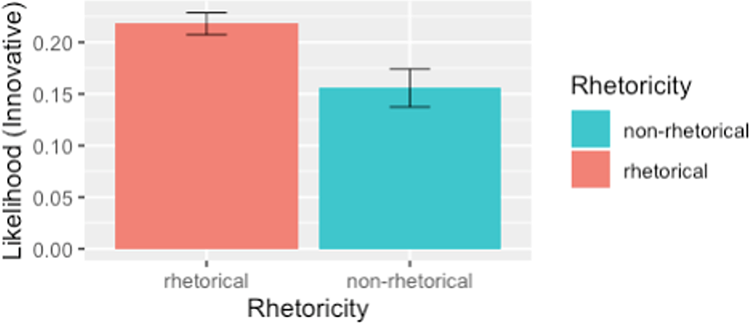

CSE speakers were more likely to use clause-initial is it in a rhetorical question (mean = 0.216, SD = 0.411, n = 1,510) compared to a non-rhetorical question that has a yes, no, or maybe response (mean = 0.149, SD = 0.357, n = 382) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of rhetoricity on likelihood to choose clause-initial is it

Speakers were also more likely to use clause-initial is it in contexts where they are being playful (mean = 0.386, SD = 0.488, n = 207) (18 and Figure 2) and were less likely to use it in other contexts (mean = 0.179, SD = 0.38, n = 1,685). Overall, it appears that CSE speakers use the innovative is it in playful, rhetorical yes-no questions.

(18) LOL IZZIT U CHECKING WHO GONNA BE THERE SO U CAN SEE IF U SHOULD HANKYPANKY

‘Lol. Are you checking who is going to be there so you can see whether you should hanky-panky?’

<COSEM:18CF50–9557–21CHF–2016>

Figure 2. Effect of playful affect on likelihood to choose clause-initial is it

Younger speakers tended to use clause-initial is it more compared to older speakers (Figure 3). One possible reason why this pattern surfaced is because of a potential change-in-progress led by the youth. Younger speakers may be innovating the conventionalized question marker – the non-polarity tag is it – for reasons such as distinguishing themselves from older speakers, etc. This claim is not far-fetched, as prior sociolinguistic research investigating language change has often reported younger speakers – the ‘movers and shakers in the community’ and ‘people with energy and enterprise’ – innovating language for various reasons like countering adult norms (Maclagan, Gordon & Lewis. Reference Maclagan, Gordon and Lewis1999: 19).

Figure 3. Effect of age on likelihood to choose innovative marker

Apart from younger speakers, Singaporean CSE speakers were more likely to use clause-initial is it (mean = 0.212, SD = 0.408, n = 1,785) compared to non-Singaporeans (e.g., Chinese from the People's Republic of China, Filipino, Taiwanese, see full list in Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales, Hiramoto, Leimgruber and Lim2021) (mean = 0.0467, SD = 0.212, n = 107) (Figure 4). This is perhaps because the construction is linked to the Singaporean identity. Singaporean speakers may have used more clause-initial is it constructions compared to non-polarity tag is it to stress their Singaporean-ness. Some evidence of this can be found in our consultation with three native CSE speakers, who identified the construction as a Singaporean feature. The correlation between the clause-initial is it construction and the Singaporean group provides strong evidence that the fronted construction is a local Singaporean innovation, and not an innovation introduced by non-Singaporeans.

Figure 4. Effect of nationality on likelihood to choose innovative marker

Our inability to find evidence of a racial contrast (Chinese vs. non-Chinese) relating to the likelihood of the use of clause-initial is it suggests that the construction is uniformly used across all racial groups in Singapore, of which the Chinese, Malays and Indians are the major ones. It is highly likely that the novel CSE is it emerged out of contact between English and the Sinitic substrate languages used by Chinese-dominant speakers of CSE (e.g., Mandarin-dominant speakers) (see Section 6.2). We hypothesize that the feature first became popular among the Chinese CSE-speaking population before it spread to (and stabilized within) the non-Chinese CSE-speaking groups. A potential reason could be because CSE is it closely resembles the standardized English tag question is it, both in terms of form and function.

In summary, we provided evidence that the use of is it in CSE is distinct from the use of is it in standardized English: the use of both non-polarity is it as well as clause-initial is it as default question markers is robust and stable in CSE but not in standardized English. We have also shown that the variation in the use of these question markers is systematically conditioned by rhetoricity, playful affect, age, and nationality. However, we have not found evidence that mocking affect, sex, race, and orthographical choice conditioned this variation.

6. General discussion

At the outset of this paper, we sought to identify the distribution of the is it question marking variants in CSE. We found that CSE speakers used clause-initial is it and non-polarity tags alongside polarity ones, with a significant preference for non-polarity tags, in contrast to standardized English. Another objective was to answer the question of whether the is it variants in CSE are conditioned by linguistic, orthographic, and social factors. Given the data used for this study, we were not able to find evidence of linguistic or social conditions affecting the use of a non-polarity construction over a polarity one. We were, however, able to identify correlations between the use of clause-initial is it and certain pragmatic factors, such as rhetoricity and playfulness. In addition, our results showed that certain social groups tend to use it more than others. A summary of what has been discussed in the previous sections and how they relate to our hypotheses can be found in Table 5.

Table 5: Summary of results (gray text = no evidence of effect, contradicting hypotheses)

Obviously, several of our predictions were not confirmed: several factors (e.g., mocking affect) that were hypothesized to have an effect on a CSE speaker's likelihood of using a particular variant of the is it construction turned out not to have one. These factors are represented in gray in Table 5. In any case, we were able to account for at least some of the variation occurring with CSE is it. We pinpointed some pragmatic and sociolinguistic factors that condition CSE is it use, consequently making it possible for us to comment on its systematicity, as well as speculate its development.

6.1 The systematicity and distinctiveness of CSE is it

Based on the patterns of variation in the use of CSE is it presented earlier, we propose the following structural conventions: in CSE, the polarity tag is rarely used to elicit a yes-no response. Instead, one uses the non-polarity tag – the default is it question marker. If a speaker wishes to be playful or hopes not to get a response, as in a rhetorical question, they typically use clause-initial is it (Table 6).

Table 6: Proposed structural conventions in CSE is it

These conventions are notably different from the conventions of standardized English, which by default use the polarity tag. In CSE, the non-polarity tag is used as the default yes-no question marker in CSE. Another structural convention that distinguishes CSE from standardized English is the use of the clause-initial is it question marker, which is not found in standardized English. Given the use of this construction alongside the tag construction, CSE is it seems to have developed from a canonical question tag to a general yes-no question marker.

6.2 The development of CSE is it

Based on the effects of the social factors identified in the model, we are also able to comment on the development of CSE is it. To recapitulate, we found an age effect for the innovation: the clause-initial is it is associated with the youth. This suggests that younger speakers were the ones who started and spread the innovative clause-initial is it construction. The order in which innovations entered CSE can be deduced by looking at the age-grading results using the apparent time model (Sankoff, Reference Sankoff and Brown2006) as well as our findings from comparing various corpora.

Using British English, arguably the source variety of CSE, as a point of comparison, we propose that the variety of Singapore English in the early post-colonial period recognized both polarity and non-polarity tag constructions. It most likely had the polarity tag as the ‘unmarked’ or default variant and the non-polarity tag as the ‘marked’ or conditioned variant. From the distributional differences between the British English (early CSE) and 1990s CSE, represented by ICE–SIN data, we argue that the polarity vs. non-polarity distribution shifted over time, perhaps before the 1990s. Instead of only being used in specific conditions, the non-polarity variant was generalized to all is it constructions. That is, CSE speakers using is it constructions eventually used the non-polarity is it tag almost exclusively.

However, the use of the non-polarity tag as the default is it question marker seems to be undergoing a process of change again recently. Based on findings from CoSEM, clause-initial is it emerges as a competing variant: a conditioned variant that tends to be used more in rhetorical, playful contexts, and by younger Singaporeans. If this pattern of change holds, ceteris paribus, it is very likely that the recent fronted is it innovation would take over the non-polarity tag as the general is it question marker, especially since the marker is found to be an index of Singaporean identity. There is already evidence of this in present day CSE: there are some cases where the fronted innovation is used in non-playful, non-rhetorical contexts, as seen in (19), (20), and (21):

We summarize the developmental trajectory of CSE is it in Table 7.

Table 7: Proposed developmental trajectory (distribution and conditions)

Currently, we do not have definitive evidence of what specifically motivated these changes. One possibility is internal change or language drift. The distributional changes could have occurred without any external influence. A more likely catalyst is language contact. It is possible that the distribution shifted due to the influence of languages spoken alongside CSE, such as Mandarin, although more evidence is needed to substantiate this claim. Part of the Mandarin yes-no question forming system (i.e., the clause-initial A-not-A construction, Table 8) might have been transferred to CSE. While the clause-medial strategy seems to have not been selected by CSE speakers, as evidenced by the lack of clause-medial is it (e.g., *You isit like her?) constructions in the corpus, the clause-final and clause-initial strategies seem to have been transferred to CSE, as indicated by the robustness of these strategies in CSE. The account involving Mandarin influence is justified as Mandarin is a dominant language (if not the most dominant non-English language) in Singapore. Mandarin is promoted as the lingua franca of Chinese Singaporeans (see e.g., Lim, Chen & Hiramoto, Reference Lim, Chen and Hiramoto2021), who form the majority of the Singaporean population (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2019).

Table 8: Comparison of yes-no question-forming strategies between CSE, Mandarin and standardized English (question: ‘Do you like her?’)

In summary, we have identified a potential contact-induced innovation in CSE: clause-initial is it. We argue that this innovation is a recent one, introduced by younger Singaporean CSE speakers. A likely reason for the proliferation of clause-initial is it is its ability to function as a salient marker of a youthful, Singlish-speaking, Singaporean identity, similar to how, for example, question tags like msibá ‘is it not’ in Lánnang-uè spoken in the Philippines are emblematic of the relatively young, hybrid Lannang identity (Gonzales, Reference Gonzales2017; Gonzales, Reference Gonzales2021). As of this point, we have yet to come across evidence that would allow us to definitively attribute the emergence of this innovation to any one particular factor (or set of factors); however, a language contact account that involves Mandarin seems very likely.

7. Conclusion

Drawing on CoSEM, a 3.6-million-word corpus of CSE finger speech, we investigated the use of is it in contemporary CSE. Apart from wanting to establish the distribution of is it use in CSE, we also wanted to determine the conditions on which CSE users utilize different is it constructions. By analyzing the frequency distributions and statistically modeling the likelihood of CSE users’ choice of is it variants, we were able to shed some light on how CSE users construct is it questions.

CSE speakers seemingly use different strategies (e.g., polarity tag, non-polarity tag, clause-initial is it) to relay the same thought, but a closer look at the variation reveals that CSE speakers have specific conventions for structuring yes-no questions involving is it. Specifically, we found that CSE speakers use two is it question constructions: (1) clause-final is it (non-polarity question tag is it) for non-rhetorical or non-playful questions, and (2) clause-initial is it for rhetorical, playful questions. We also found that the first construction is associated with older Singaporean speakers whereas the second is used robustly by younger speakers and speakers who identify as Singaporean. There was no evidence of sex, race, orthography, or mocking affect conditioning the choice of construction or strategy.

These (socio)linguistic conventions, like conventions in other languages, are not static. They can change. For instance, although most CSE speakers follow the conventions listed above, we identified instances where some speakers (younger speakers) are generalizing the use of clause-initial is it such that it is used even in non-playful or non-rhetorical contexts, suggesting that there is ongoing change in progress.

Currently, we do not have sufficient evidence to definitively pinpoint the catalysts for change and/or variation in the use of CSE is it variants. However, an account involving language contact where Mandarin is a primary contributor seems very likely, based on a comparison of structures between CSE, Mandarin and English. Overall, by analyzing variation in CSE is it use, we were able to identify linguistic conventions, observe correlations between social groups and particular is it variants (sociolinguistic conventions), and comment on the development of the is it question-marking system in CSE.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledges the support provided for this project by Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund Tier 1 under WBS R-103-000-167-115 as well as Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research (Conference) Fund Tier 1 under R-103-000-174-115. We also thank class members of EL3211: Language in Contact and of EL3551: Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP) at the National University of Singapore. We'd also like to show our sincere gratitude to our research assistants for this paper, Vincent Pak and Lauren Yeo. Last but not least, we are immensely grateful to Andrew Moody and two anonymous reviewers' comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

WILKINSON DANIEL WONG GONZALES is an Assistant Professor at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Department of English). His research interests include World Englishes, sociolinguistics, language variation and change, language contact, and language documentation. Email: [email protected]

WILKINSON DANIEL WONG GONZALES is an Assistant Professor at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Department of English). His research interests include World Englishes, sociolinguistics, language variation and change, language contact, and language documentation. Email: [email protected]

MIE HIRAMOTO is an Associate Professor in the Department of English, Linguistics and Theatre Studies at National University of Singapore. Her research interests are sociolinguistics and linguistic anthropology, in particular, contact linguistics as well as language, gender, and sexuality. Email: [email protected]

MIE HIRAMOTO is an Associate Professor in the Department of English, Linguistics and Theatre Studies at National University of Singapore. Her research interests are sociolinguistics and linguistic anthropology, in particular, contact linguistics as well as language, gender, and sexuality. Email: [email protected]

JAKOB R. E. LEIMGRUBER is Professor at the University of Regensburg, Germany. His research focusses on world Englishes and on English in multilingual contexts. He is the author of Singapore English: Structure, Variation, and Usage (2013) and Language Planning and Policy in Quebec: A Comparative Perspective (2019). Email: [email protected]

JAKOB R. E. LEIMGRUBER is Professor at the University of Regensburg, Germany. His research focusses on world Englishes and on English in multilingual contexts. He is the author of Singapore English: Structure, Variation, and Usage (2013) and Language Planning and Policy in Quebec: A Comparative Perspective (2019). Email: [email protected]

JUN JIE LIM is a PhD student in linguistics at the University of California San Diego. His research interests are syntax and its interfaces, variation and change, and fieldwork. His current work focuses on Khalkha Mongolian and Singlish. Email: [email protected]

JUN JIE LIM is a PhD student in linguistics at the University of California San Diego. His research interests are syntax and its interfaces, variation and change, and fieldwork. His current work focuses on Khalkha Mongolian and Singlish. Email: [email protected]