When Timor–Leste became the first new nation of the 21st century in 2002, one of the many decisions that needed to be made concerned language. Timor–Leste is a country of around one million people, with at least 16 indigenous languages and three foreign languages contributing to its multilingual character. For reasons related to its 400-year colonial history and the resistance to Indonesian occupation from 1975 to 1999, the new constitution declared that Portuguese would be one of two official languages, the other being the indigenous Tetun Dili. The choice of Portuguese rather than English was controversial, and criticised in some quarters, for it appeared to defy geographical location (e.g. Savage, Reference Savage2012). After all, Australia lies an hour's flight south of Timor–Leste, and English has been adopted as the working language of ASEAN, an organisation which the country has aspirations of joining. English is certainly the regional lingua franca, and very often referred to as the global lingua franca. Not, however, that the constitution was ignoring this reality. As well as naming Portuguese and Tetun as official languages, it named English and Bahasa Indonesia as working languages, and all indigenous languages as national languages. Thus the decisions around language in the constitution laid claims to identity and culture, as well as remaining open to global engagement in trade, technology, education and other contributors to modernisation.

Different views on the likely trajectories of the official and working languages have been expressed at different times. Tetun and Portuguese have both been strongly linked to expressions of Timorese identity (Kroon & Kurvers, Reference Kroon and Kurvers2020; Taylor–Leech, Reference Taylor–Leech2008, Reference Taylor–Leech2012), but the possibility has also been raised that English may start to displace Portuguese through a combination of such factors as an ongoing international anglophone presence in the country through the activities of the United Nations and NGOs, and a change in generational leadership of the country (which has not yet occurred). This paper, then, considers the extent to which English has established itself in the Timorese linguistic ecology two decades after independence. It does this by examining language use in print media and by considering three possibilities:

– The development of an identifiable Timorese English

– The influence of English on Tetun Dili

– The use of English for specific functions

Data sources

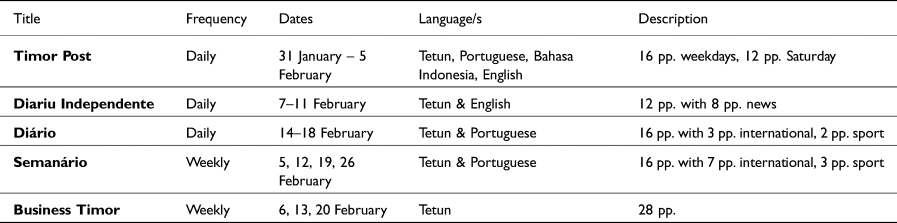

The data come from a corpus of five local newspapers published from late January through February 2022. Three of these were daily newspapers, the other two were published weekly. Four of the five were multilingual, with the dominant languages being Tetun and Portuguese. Details are shown in Table 1. For each daily newspaper, issues were collected for a full week with care taken not to have the same week represented by more than one publication. This was done to manage the possibility that an important event might unduly dominate the corpus and skew the results. For example, if the Australian Prime Minister had visited Timor–Leste during this time, it may have resulted in an unusually high use of English in the print media through the reporting of speeches and related activities, and the influence of media releases and foreign press presence. In the event, no such occurrences were apparent in the corpus, although the global COVID-19 pandemic was a recurring theme across the weeks.

Table 1. Newspapers analysed

These data sources would allow investigation of the three possibilities raised above by:

• Examining English language texts to identify distinguishing local features; in New Zealand English, for example, the presence of Māori words is the most distinctive feature (Deverson, Reference Deverson1991)

• Examining Tetun language texts to identify discernible English influence

• Considering the uses to which English is put in the newspapers

The data used places certain constraints on what is being reported here. These are written sources, so questions of phonology and prosody are beyond the scope of this inquiry. The primary focus, instead, is on the lexicon. Further, as newspapers are a relatively formal genre the characteristics of less formal language use are unlikely to be found. In what follows, the content of the newspapers is divided into three main categories: news, official notices, and advertisements. Each of these three main categories will be described in turn, before discussing the three possibilities for English in Timor–Leste raised earlier.

News reporting

The news category included local, regional, and international news, as well as sport, business, and the occasional feature or editorial. As can be gauged from Table 1, English was not widely used in news reporting in this corpus and, indeed, only had a regular presence in Diariu Independente, which each day carried a front page story explicitly labelled as being in English. Three of these five stories were clearly about events in the country, but none included identifiably Timorese terms beyond place names and the names of politicians.

The front page of each issue of Diariu Independente also displayed a dashboard with latest COVID-19 vaccination information, presented in English. In addition, one issue carried a page of news written in English, all sourced from the BBC. Similarly, in one issue of Timor Post there was a page in English; this was an opinion page, seemingly sourced online and with a Thai focus. When neither author nor topic are local, a local variety of English is not going to be used. In this limited presence of the language, there was nothing to mark it as being distinctively Timorese.

However, although extended use of English in news reporting was largely absent, the language was present in various ways. Taking one issue of the predominantly Tetun Business Timor as an example, the very name of the newspaper draws on English rather than using a Tetun, Portuguese, or even Bahasa Indonesia word for business. Elsewhere a heading declares Headline News, although other headings such as Opiniaun and Publisidade use Tetun. The cover of the issue is dominated by a photograph of two men shaking hands as they look into the camera after a signing ceremony which a large background sign in English clearly identifies as a handover ceremony between the Ministry of Public Works and the European Union. Reporting of this story embeds such English words as waste audit and handover into the Tetun text, just as, in other stories, English company names and job titles are slotted into Tetun, Tuir Managing Director of The Downstream Business Unit iha Timor-Gap being an example. The same practices are found in all the newspapers, with random examples being influencer (from Diario), comeback, and booster (both from the Timor Post). These words and phrases could be regarded as nonce borrowings, serving a one-time purpose but being unlikely to enter the lexicon.

Possibly the greatest concentration of English words and phrases came in two separate full page, Bahasa Indonesia feature articles carried in the Timor Post. The headline of the first included the phrase blessing in disguise and the article included such terms as double-antibody, hybrid immunity, and the description widespread but mild. The second spoke of The Fed and included the likes of civil unrest, tight money, dollar, and too low for too long, as well as the borrowing into Indonesian from English, investor.

Official notices

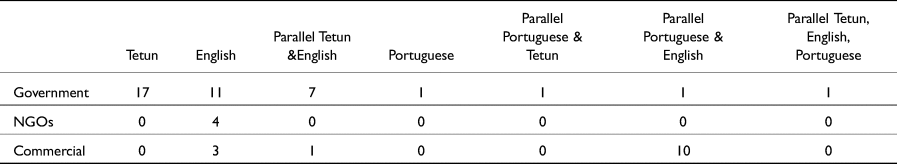

Despite its absence in news reporting, as discussed above, in all the newspapers extended use of English was present through the publication of official notices. These could be authored by government ministries and agencies, NGOs and embassies, and by commercial actors. Analysis showed clear preferences in code choice (see Table 2). Government ministries and agencies showed the greatest variety of practice with, by number, Tetun only, English only, balanced English and Tetun, and, with solitary examples of each, Portuguese, balanced Portuguese and Tetun, balanced Portuguese and English, and a balanced trilingual notice. The use of English here seemed surprising, but was restricted to calling for bids such as requests for quotations, a point that will be returned to later when the functions of English in Timor–Leste are discussed. By contrast with this variety of practice advertisements from NGOs and embassies were solely in English, and commercial actors displayed a strong preference for English, either on its own, or as balanced bilingual texts, with either Portuguese or Tetun. It should be noted that these claims do not take account of multilingual elements such as the use of Portuguese in addresses or German in an NGO name. In all the extended use of English in these notices there was, however, but perhaps unsurprisingly given their formal nature, nothing distinctively Timorese beyond the occasional place name.

Table 2. Languages used in official notices

Advertisements

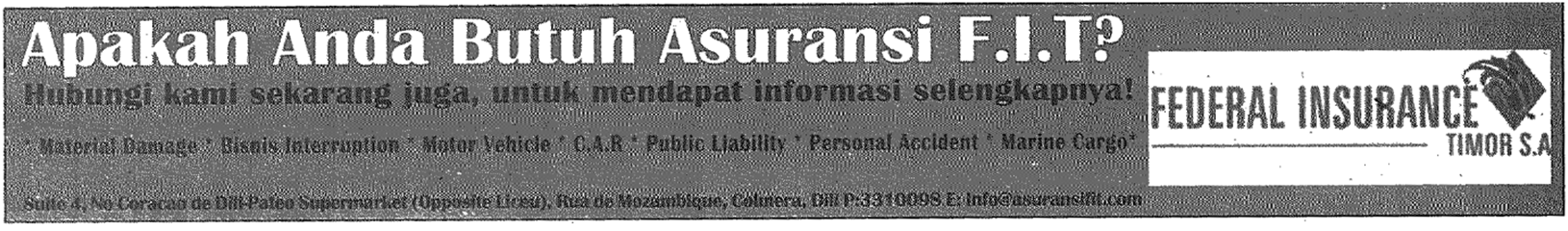

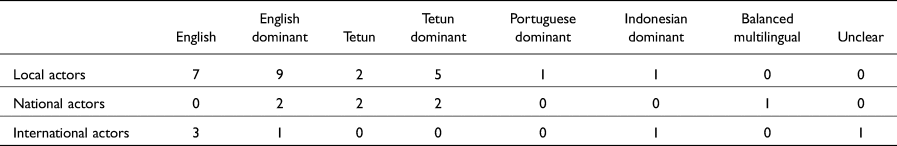

Thirty-eight unique advertisements were identified in the five newspapers, with both official languages and the two working languages (English and Indonesian) being found. Advertisements were inserted into the newspapers by local, national, and international actors which resulted in other languages being present through business names, such as the French logistics company Bolloré or the German haus in FoneHaus. Excluding these and the use of Portuguese in address lines, often difficult to read (Figure 1), there was a tendency for English to dominate in advertisements from international actors, Tetun for national, and English again for local businesses. It was striking that, with one exception, local businesses with Portuguese names chose to advertise in English. However, a minority of advertisements were monolingual, and none used solely Portuguese. Details can be seen in Table 3. Some of the diversity of language practice can be seen in Figure 1, an insurance advertisement, which catches the eye with the company name (English) and a question posed in Bahasa Indonesia beneath which is a further line in Indonesian. Details of the type of insurance available are provided on the third line, all in English apart from the Indonesian borrowing bisnis. Portuguese appears in the address at the bottom, but here too English makes an appearance with the words supermarket and opposite.

Figure 1. Federal Insurance advertisement Source: Semanário, 5 February 2022, p. 3

Table 3. Languages used in advertisements

A further example is shown in Figure 2, one of two different advertisements inserted by an Indonesian company. The product name and other information is provided in English, but further information mixes both Tetun (seguru, safe) and Portuguese (corderosa, pink, confortável, comfortable). This implies an expectation that readers will be able to negotiate between different languages with ease.

Figure 2. Pertamina advertisement Source: Timor Post, 31 January 2022, p. 1

To delve a little more deeply into the presence of English in advertisements, it is possible to examine two sub-categories that emerged in the dataset. The first is for telecommunication companies, three of which contributed five unique advertisements, and were the largest contributor to the national advertisers. All advertised in Tetun, although words and phrases of English origin, such as QR code, were occasionally used. These, along with words such as internet, may however have transcended their linguistic origins and could be regarded as belonging to an unmarked global lingua franca.

Among the local advertisers three restaurants contributed advertisements and all used English, regardless of the restaurant name. Two used solely English, the other used both Tetun and English. The English used in two of the three suggested they had not been professionally produced, or at least not by a proficient speaker, for they contained such non-native-like phrasings as For the love of fine food lover and spelling errors as in smooky and bleack, presumably for smoky and black.

A Timorese variety of English

Given this was a study of written language, any evidence of an emerging variety was expected to be lexical. Beyond personal and place names, this might appear as the names of flora and fauna, objects of material culture, or terms referring to such aspects of social culture as relationships and cultural practices. However there was nothing in this newspaper corpus to suggest the existence of an emerging variety. This is unsurprising for two reasons. First, the extended use of English was extremely limited in news reporting and mainly found in official notices which is a formal genre, in some cases shaped by legal requirements. Second, theories of new Englishes emerging in post-colonial settings (Schneider, Reference Schneider2003; Schneider, Reference Schneider2007) posit the existence of both indigenous and settler groups. In Timor–Leste there was no English-speaking settler society, and at this stage it is more likely that a new variety of Portuguese than of English will establish in this linguistic ecology (as has been discussed by de Almeida & de Albuquerque, Reference de Almeida and de Albuquerque2019). This is not to suggest that a Timorese variety of English will not emerge, but it may appear first as a spoken variety rather than in written language use. That is an area for future investigation.

English influence on Tetun

While official policy provides for Portuguese as the source language for new coinings in Tetun, and this is certainly standard practice, previous studies have cited examples where speakers have drawn on English. Sarmento (Reference Sarmento2013: 79) provided the example of envaironmentu having entered Tetun, from the English environment, rather than the officially preferred transliteration of Portuguese meio-ambiente. Macalister (Reference Macalister2012) cited the use of English ice cream in an otherwise Tetun hand-written sign in a shop window, and suggested that the graffito raskol may have been influenced by Papua New Guinea English. As previously-mentioned examples such as waste audit and influencer have suggested, there was ongoing evidence of English being used in otherwise Tetun texts in this corpus but, it is important to note, these were direct borrowings rather than being integrated into Tetun; they were, in other words, more like ice cream than envaironmentu. The important point, however, is that English is part of the linguistic repertoire of Tetun speakers.

Words that retain their English orthography are, of course, easier to identify than those that do not. After all, as Williams–van Klinken and Hajek (Reference Williams–van Klinken and Hajek2018: 619) pointed out, ‘the written registers of Portuguese, Indonesian and English share many features . . . [meaning] that all are potentially influencing Tetun in the same ways, making it harder to identify the specific source of an innovation in that language’. Lexically, for example, English and Portuguese share many homonyms, such as hotel, and even more words derived from the same root. In the Tetun ne'ebe hetan impaktu negativu husi pandemia COVID-19, as an example, the phrase impaktu negativu could conceivably be derived from Portuguese (impacto negativo), English (negative impact), or Indonesian (impak negatif). What is clear however is that Tetun syntax, not English, is determining word order. When English orthography and syntax is retained, as in the earlier example of waste audit, this typically occurs when news reporting is about NGOs or other Anglophone enterprises; a similar observation was made by Williams–van Klinken and Hajek (Reference Williams–van Klinken and Hajek2018, p. 627).

A final point to make is that the English lexical influence on Tetun may often be mediated via Bahasa Indonesia. The use of bisnis is a good example. Both Tetun negósiu and Portuguese negócio are also available, and used, but the presence of bisnis is a reminder that many Timorese – including journalists – were educated in Indonesian prior to independence, and that economic ties with Indonesia remain strong (as suggested by Figures 1 and 2).

Functions of English

The presence of English in advertisements and official notices suggests that the predominant domain in which English is used relates to economic activity. This was also noted in two studies of public signage in Dili (Macalister, Reference Macalister2012; Taylor–Leech, Reference Taylor–Leech2012) and speaks in part to where economic/spending power lies. There would appear to be an equation of English-speaking with affluence, as well as a recognition that many Anglophone businesses are operating in Timor–Leste; this would seem to explain the high use of English in official notices discussed earlier. Those responding to, for example, a request for quotation are as likely to be Anglophone businesses as not. However, English also appears to be being used for symbolic purposes. In Figure 2, for instance, the product name Bright Gas is connoting a sense of modernity and technological sophistication, whereas actual information is conveyed in other languages.

Claims have been made elsewhere of the importance of English language skills for employment, in such industries as petroleum and journalism (Newman, Reference Newman, Crandall and Bailey2018; Parahita, Monggilo & Wendratama, Reference Parahita, Monggilo and Wendratama2020) and for work in neighbouring Australia. Job advertisements were a rarity in this newspaper corpus, and the one identified, for an NGO, required applicants to possess excellent communication in English and Tetum whereas a sound level of Portuguese was only an advantage. The application had to be made in English, and the placement of this English language advertisement in a newspaper that carried the majority of its content in Tetun and Portuguese speaks to the instrumental value attached to the language in the Timorese context.

Conclusion

The picture that emerges from this examination of Timorese newspapers is of a dynamic, multilingual environment where English forms part of the local linguistic repertoire but is not evident as an emerging variety. Official language policy appears to be reflected in and determining the languages used for most of the content in the print media, but the texts with a particular audience in mind – official notices, advertisements – seem to be envisaging an English-speaking, and sometimes Indonesian-speaking, readership in addition to Tetun speakers. Whether the visibility of English will grow or shrink in the future, and whether a distinctive English variety is used for interpersonal communication between Timorese, remain areas of ongoing inquiry.

JOHN MACALISTER is Professor of Applied Linguistics at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. He began his academic career focusing on the interaction between English and the Māori language in NZ, and has been investigating the language situation in Timor–Leste for more than a decade. His most recent books are second editions of Language Curriculum Design and Teaching ESL/EFL Reading & Witing, both with Professor Paul Nation and published by Routledge. Email: [email protected]

JOHN MACALISTER is Professor of Applied Linguistics at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. He began his academic career focusing on the interaction between English and the Māori language in NZ, and has been investigating the language situation in Timor–Leste for more than a decade. His most recent books are second editions of Language Curriculum Design and Teaching ESL/EFL Reading & Witing, both with Professor Paul Nation and published by Routledge. Email: [email protected]

MELKY COSTA AKOYT is an English lecturer at the Dili Institute of Technology, Timor–Leste, with over five years of experience teaching English as a Foreign Language to Timorese students. He holds a master's degree in TESOL from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Melky currently serves as the English Program Coordinator at his institution. He is interested in language assessment, English for Academic Purposes, and teachers' training. Email: [email protected]

MELKY COSTA AKOYT is an English lecturer at the Dili Institute of Technology, Timor–Leste, with over five years of experience teaching English as a Foreign Language to Timorese students. He holds a master's degree in TESOL from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Melky currently serves as the English Program Coordinator at his institution. He is interested in language assessment, English for Academic Purposes, and teachers' training. Email: [email protected]