1 Introduction

This article explores the distribution of evidential adverbs in complement clauses that act as arguments of a complement-taking predicate. That the form of complement clauses is determined by the (semantics) of a complement-taking predicate has been well-established (Noonan Reference Noonan and Shopen2007). However, whether across languages the occurrence of elements occurring in the complement clause is then in turn determined by the constraints of the complement-taking predicate is still being explored. Haegeman (Reference Haegeman2006: 1664), Bastos et al. (Reference Bastos, Casseb-Galvão, Gonçalves, Dall'Aglio Hattnher, Hengeveld, Sousa and Vendrame2007) and Keizer (Reference Keizer, Keizer and Olbertz2018: 5; Reference Keizer2020: 7,13) all address the topic. While Bastos et al. (Reference Bastos, Casseb-Galvão, Gonçalves, Dall'Aglio Hattnher, Hengeveld, Sousa and Vendrame2007) show for Brazilian Portuguese that modifying modal expressions align with the constraints imposed by the complement-taking predicate, Keizer (Reference Keizer, Keizer and Olbertz2018) considers the occurrence of the English adverb frankly in complement clauses. When initially surveying occurrences of evidential adverbs in written news items for this study, it was noticed that evidential adverbs did not seem to be consistent in their alignment with the type of complement. The present article, therefore, focuses on evidential adverbs in complement clauses. It is argued that the distribution of evidential adverbs in complement clauses is determined not only by the nature of the complement clause but also by the nature of the evidential adverb, and the nature of the anchor of the evidential adverb. The first factor concerns the semantics of complement clauses acting as argument of a complement-taking predicate, the second is the type of source evoked by the evidential adverb, and the third is whether the anchor of the evidential adverb is the subject of the matrix clause or the current speaker.

The present study focuses on sentence adverbs, not on cases where the adverbs function as premodifiers of adjectives. The grammatical configuration under study is illustrated in (1) and (2) in which an evidential adverb modifies the verb in the complement clause, which acts as an argument of a complement-taking predicate. In all examples in the article, the complement-taking predicate and the evidential adverb are in bold.

(1) Deputy Supreme Court president Lord Mance said the present law ‘clearly needs radical reconsideration’ and that the opinion of the court … cannot be safely ignored. (GB 18-06-07)

In (1), the evidential adverb clearly, which modifies the verb need, appears in the complement clause of the complement-taking predicate say. The quotation marks show that the subject of the matrix clause is the anchor who is responsible for using the evidential adverb, as the adverb is part of the quote.

(2) Madden, a production assistant who worked at Miramax for a decade, told the Times that Weinstein allegedly ‘prodded her for massages at hotels’, a common theme among the sources the Times's reporters spoke with. (GB 18-01-10)

In (2), the quotation marks help us to see that Madden is not the anchor of the evidential adverb as the writer chooses not to include the evidential adverb allegedly in the quote. This means that the anchor is the current speaker.

The framework used for analysis in this article is Functional Discourse Grammar (FDG). FDG uses its categorial analysis to classify not only complements of complement-taking predicates but also various types of adverbs including evidential adverbs. For this reason, this article adopts the theory of FDG to examine the licensing patterns of complement-taking predicates, the constraints of complement clauses and the categories of evidential adverbs appearing in complement clauses. Furthermore, I refer to Noonan's (Reference Noonan and Shopen2007) list of complement-taking predicates, which creates a set of expectations for the form of the complement clause.

The hierarchical layered organisation of FDG will be used here firstly to present a classification of English evidential adverbs drawn up in Kemp (Reference Kemp2018). This work was based on the classification used by Hengeveld & Dall'Aglio Hattnher (Reference Hengeveld and Dall'Aglio Hattnher2015) to analyse grammatical evidentials in 64 native Brazilian languages. Secondly, FDG is applied to address the nature of the complement clause determined by the complement-taking predicate (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Lachlan Mackenzie2008; Keizer Reference Keizer2015). The FDG layers to which the complement clauses belong will be compared with the layer of the evidential adverbs they contain. This means, for instance, that an explanation can be provided for the licensing of the evidential adverb clearly in the complement clause of the verb of communication say in (1) and for the licensing of allegedly in the complement clause of tell in (2).

The third issue to be addressed in this article that has not been analysed within FDG but does appear to influence the distribution of evidential adverbs in complement clauses is the anchor of the evidential adverb, that is, the person who is responsible for expressing the source information. The anchor can either be an actor anchor, that is, the subject of an active matrix clause, as in (1), or of a passive matrix clause, or it can be a current speaker anchor, that is, the speaker/author of the text, as in (2).

The article is organised as follows. Section 2 provides the necessary theoretical background, including a brief presentation of FDG, and its treatment of evidentiality. Furthermore, the section discusses the FDG classification of complement clauses and expands on the notion of anchoring. Section 3 then formulates the predictions, which follow from the theory with respect to the licensing of different types of evidential adverbs in different types of complement clauses, and with respect to the different types of anchoring. Section 4 describes the corpus used and the methods applied. The results relating to the predictions are presented in sections 5 and 6. Finally, section 7 is dedicated to the summary and discussion and section 8 to the conclusions.

2 Theoretical background

This section provides the FDG tools chosen for the analysis. In section 2.1, I present a brief outline of FDG. Section 2.2 then goes into the classification of evidential adverbs, while section 2.3 presents the classification of complement clauses and complement-taking predicates. Lastly, section 2.4 discusses the notion of anchoring.

2.1 Functional Discourse Grammar

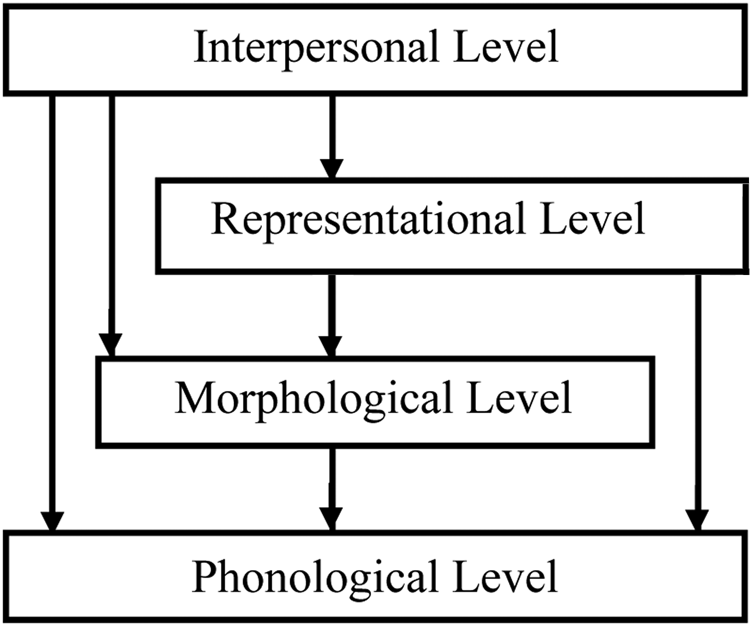

FDG is a theory that has at its core a grammatical component with interrelated levels, which are diagrammatically set out in figure 1. The levels run from the pragmatic Interpersonal Level at the top of the hierarchy, through the semantic Representational Level and the Morphosyntactic Level, to the lowest level, the Phonological Level. The two lower levels cover encoding while the two top levels, which concern us, comprise elements of formulation. The arrows in figure 1 show the direction of the scope relations. Each level in figure 1 comprises different hierarchically ordered layers, which are depicted in table 1 as separate cells, between which arrows show scope relations.

Figure 1. Levels in FDG (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Lachlan Mackenzie2008)

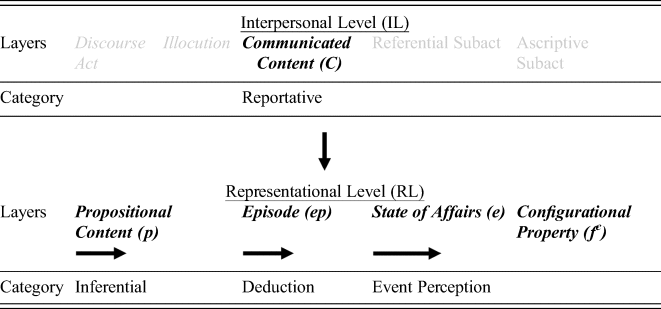

Table 1. Layers of the upper two levels of formulation in the FDG hierarchy

(from Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Lachlan Mackenzie2008)

In table 1, the names of the layers in black are those that concern us in this article, as the discussion below shows. This means that we are concerned with one layer, the Communicated Content, on the Interpersonal Level, which is the level of pragmatics, and four layers on the lower Representational Level, which is the semantic level. While the Communicated Content on the Interpersonal Level scopes over all layers on the Representational Level, the Propositional Content layer on the Representational Level scopes over all the lower layers on the same level. The scopal layers reflect the positions that the elements can take in a clause.

Elements that are classified in the FDG categories of concern in table 1 are exemplified in later sections of the article. Now I will briefly describe the layers of interest. On the Interpersonal Level, the Communicated Content is concerned with the message that the speaker wants to evoke in the addressee. On the Representational Level, the Propositional Content reflects mental constructs, while the Episode concerns a set of States of Affairs that involve the same time, space and participants. A State of Affairs is a single event or state, and is composed of elements of the Configurational Property such as a predicate and its arguments.

I will focus on the FDG categorisation of evidential adverbs in section 2.2 and that of the complement clauses of complement-taking predicates in section 2.3.

2.2 Evidential adverbs

Firstly, this section briefly discusses ways in which evidential adverbs have previously been categorised in the literature with respect to source of information (2.2.1), level of analysis (2.2.2) and their functional role (2.2.3). I then turn to the classification of evidential adverbs within FDG (2.2.4).

2.2.1 Source

In this subsection, I consider the broad and narrow views of evidentiality in the literature and cite authors who adopt these views. The broader view involves the pragmatic-interactional functions of evidentiality such as reliability and judgement, while the narrow view focuses on the semantic categorisation of types of evidential items.

Within his broader view of evidentiality, Chafe (Reference Chafe, Chafe and Nichols1986: 263), who writes on English, discusses attitudes to knowledge, while in his narrow view, he sees evidentiality as marking source of knowledge. Martínez Caro (Reference Martínez Caro2004: 188), who combines the broad and narrow views, sees evidential meaning as having a ‘double function’ of source of information together with an expression of a degree of reliability/certainty. Carretero & Zamorano-Mansilla (Reference Carretero, Zamorano-Mansilla, Marín-Arrese, Carretero, Hita and van der Auwera2014) discuss the relation between epistemic modals and evidentiality. Marín-Arrese, Hassler & Carretero (Reference Marín-Arrese, Hassler and Carretero2017: 1) adopt the broader view of evidentiality and consider speaker stance involving attitude or commitment to the conveyed information. However, Willet (Reference Willett1988: 55) points out that underlying both the broad and narrow views of evidentiality is an indication of where the conveyed information comes from.

Within the discussion of the narrow view of evidentiality, which mainly excludes discussion of epistemic meaning, linguists posit various semantic categorisations of evidential adverbs which reflect source of information. In his work on English, Guimier (Reference Guimier1986: 253–5) makes a distinction between the reportative, the inferential based on present knowledge and that based on perception. Guimier paraphrases the latter type of inferential as follows: ‘From what I could see, I inferred that …’ (Guimier Reference Guimier1986: 253). Willet (Reference Willett1988: 57) presents two main types of evidence: direct, which is attested, and indirect, which is reported and that which is inferred. Although Carretero, Marín-Arrese & Lavid-López (Reference Carretero, Marín-Arrese and Lavid-López2017) focus on the pragmatic-interactional function of evidential validity of English evidential adverbs, they do categorise adverbs into types of evidence: direct perceptual evidence, indirect-inferential evidence and indirect-reportative evidence. Nuyts (Reference Nuyts2017: 67) initially names three main categories of evidentiality: the direct or experienced evidentials, and two types of indirect evidential. The two indirect categories are: firstly, evidentials that are inferential, showing information arrived at either through logical reasoning from existing knowledge or from direct perception; and secondly, information through hearsay. Nuyts splits the three categories into two on the basis of whether they express attitude. Inferentials, he holds, are attitudinal while experienced and reported evidentials are not.

Aikhenvald (Reference Aikhenvald, Aikhenvald and Dixon2014: 12), who focuses on closed systems of grammatical evidentiality, splits the category involving logical reasoning into inference, based on perception, and assumption, based on existing knowledge. Similarly, although using different terms, Hengeveld & Dall'Aglio Hattnher (Reference Hengeveld and Dall'Aglio Hattnher2015) identify two types of logical reasoning in their analysis of grammatical evidential items of 64 native Brazilian languages. The present article and Kemp (Reference Kemp2018) adopt Hengeveld & Dall'Aglio Hattnher's four-way categorisation of evidentials to analyse English evidential adverbs. The FDG categories, which are presented in table 2 and discussed further in section 2.2.4, comprise the Reportative, the Inferential based on stored knowledge, the Deductive category involving a conclusion based on direct perception, and finally, Event perception reflecting direct perception of the immediate situation without inference.

Table 2. Features of different knowledge bases for FDG evidential categories

(from Kemp Reference Kemp2018: 745)

The top row of table 2 shows the FDG labels for the types of evidentiality. Below the labels are the sources of knowledge or knowledge bases involved. It can be read from the table that the category inference involves inference based on existing knowledge, while the category deduction involves inference based on direct perception.

2.2.2 Level of analysis

In Ernst (Reference Ernst2000, Reference Ernst2002) and Frey & Pittner (Reference Frey, Pittner and Doherty1999), the level of analysis of speaker-oriented adverbs is explicitly connected to the position that the adverb may take in the sentence and is analysed with respect to scope relations. This can be illustrated by Frey & Pittner's (Reference Frey, Pittner and Doherty1999) analysis of two non-evidential adverbs: the higher layer evaluative luckily and the lower layer modal probably.

(3)

(a) She luckily has probably got a job.

(b) *She probably has luckily got a job. (Frey & Pittner (Reference Frey, Pittner and Doherty1999: 19)

(3a, b) show how the position of the adverb in the sentence relates to the layer of the adverb. When the lower adverb precedes the higher one, the sentence is considered unacceptable (Frey & Pittner Reference Frey, Pittner and Doherty1999: 19).

In FDG, adverbs are analysed at various levels and layers, and the layers also relate to the position that elements take in the sentence. For instance, in FDG, the evaluative adverb luckily (3a) is a modifier of the Communicated Content on the higher Interpersonal Level, while probably, which expresses the propositional attitude of the speaker, is at the lower layer of the Propositional Content on the Representational Level. According to an FDG analysis, this means, too, that luckily can scope over the lower probably (3a) but not vice versa as seen in (3b).

Although Ernst (Reference Ernst2000, Reference Ernst2002) does not dwell on evidential adverbs, he does show that their linear position also reflects whether the adverb form is read as a higher adverb as in (4a), in which clearly is evidential, or as in (4b) where clearly is a lower adverb of manner.

(4)

(a) They clearly saw the sign.

(b) They saw the sign clearly. (Ernst Reference Ernst2000: 84; Reference Ernst2002: 43)

Carretero (Reference Carretero2019: 275, 304) studies -ly adverbs that have an evidential and a manner use: manifestly, noticeably, patently, visibly. She argues that an evidential and a manner meaning often coexist and, in these instances, the evidentiality of the adverb is held to be ‘a pragmatic implication of the meaning of manner’ (Carretero Reference Carretero2019: 275). In FDG's hierarchical structure, an adverb that can have an evidential or a manner reading in different contexts is analysed at different layers with the adverb conveying a manner meaning being on the lower layers of the Representational Level. As will be seen in table 5 of section 2.2.4, in FDG, different evidential adverbs are found at various layers depending on the source of the information.

2.2.3 Functional role: evidential adverbs and orientation

In their descriptive grammar, Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 620) include evidential adverbs in their category of content disjuncts, through which they hold that the speaker expresses a comment of conviction, doubt or value judgment with respect to the content of the clause. The work also adds that some -ed-based adverbs such as allegedly express the view of others (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 623n). Within a scopal theory approach, Ernst (Reference Ernst2000, Reference Ernst2002, Reference Ernst2020) categorises evidential adverbs as speaker-oriented adverbs, or rather as adverbs showing the view of the speaker, which he notes are adverbs mostly ending in -ly. Ernst (Reference Ernst2009: 536n) suggests that in some cases the term speaker-orientation may be too narrow for evidential adverbs such as obviously, as they may well involve subject-orientation or experiencer/point-of-view orientation. The reason why this article does not adopt terms describing orientation but prefers the notion of anchor is explained in section 2.4.

2.2.4 Evidentiality in FDG

FDG has four categories of evidentiality: reportativity, inference, deduction and event perception. Table 2 shows how these relate to one another. Each category draws on a different source, that is, a different knowledge base. The FDG evidential categories are reflected in the definition of evidentiality adopted here, which is an adapted version of De Haan's (Reference De Haan, Frajzyngier, Hodges and Rood2005: 380) definition of evidentiality.

Evidentiality asserts the existence of evidence, which could either be external to or in the speech situation or it could be the result of a cognitive process. (Kemp Reference Kemp2018: 744)

This definition follows the narrow view of evidentiality and does not admit of epistemic meaning in evidentiality.

The four FDG categories of evidentiality were identified and recorded in Hengeveld & Dall'Aglio Hattnher (Reference Hengeveld and Dall'Aglio Hattnher2015). The categories fall within the two highest levels of formulation of the FDG hierarchical organisation as can be seen in table 3, in which scope relations are indicated by arrows. The item before the arrow scopes over the item(s) after the arrow.

Table 3. Evidential categories mapped on to the Interpersonal Level (IL) and Representational Level (RL) (from Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Lachlan Mackenzie2008)

The two FDG levels in table 3 are collapsed in table 4 in which arrows show the scopal relations between the four evidential categories.

Table 4. Sketch of the scopal FDG hierarchy

As shown in the fourth column within the Interpersonal Level in table 3 and within the second column in table 4, only one evidential category, the reportative evidential, operates on the pragmatic Interpersonal Level, at the Layer of the Communicated Content. It scopes over the other three evidential categories at the Representational Level. There is also a scopal relation between the three relevant layers of the Representational Level as shown in table 4.

The position in the hierarchy of the reportative evidential category on the Interpersonal Level reflects the category's role in signalling the presentation of a message from elsewhere, for instance, a reported message from a previous conversation or document, which then forms a knowledge base to which the anchor has access. The adverbs of this layer that were analysed in Kemp (Reference Kemp2018) for their uses in main clauses are reportedly, purportedly, allegedly, supposedly, evidently, apparently.

On the Representational Level, we see three further evidential categories, which are labelled inference, deduction and event perception. The higher categories of inferential evidential -ly adverbs such as evidently, apparently, presumably, obviously, seemingly and clearly signal that content has arisen from a cognitive process based on existing knowledge. Deductive evidential adverbs such as apparently, obviously, seemingly, clearly and visibly signal that a message has arisen from a cognitive process triggered by direct perception. In the lowest evidential category of event perception, adverbs such as visibly reflect direct perception of an event or immediate situation without inferencing.

Table 5 shows the results of the classification of 11 frequent evidential adverbs occurring in main clauses into FDG categories in Kemp (Reference Kemp2018). Table 5 shows the four types of evidential adverb on four different FDG layers. In the FDG classification, there are no evidential adverbs on the layer of the Configurational property.

Table 5. FDG classification of evidential -ly adverbs in main clauses

(Kemp Reference Kemp2018: 759)

In column 1 are the evidential adverbs, which are part of this study. In row 2 are the types of FDG evidential categories. Reading table 5 horizontally, we see that while some evidential adverbs fall into just one evidential category, such as reportedly, others, such as evidently, can have a reportative reading and in other contexts be used as an inferential evidential adverb. Cells that are empty indicate that no occurrences of the 11 adverbs in the relevant evidential readings were attested in the data analysed.

2.3 Complementation and complement-taking predicates

This section firstly presents Noonan's categories of complement-taking predicates, which are translated into FDG categories. If the FDG evidential categories of the adverbs contained within the complement clauses of these predicates is licensed, this is called a match. If the complement clause does not license the adverb, the instance is called a mismatch. These labels allude to Noonan's use of the term ‘match’ to refer to the alignment of a complement with its predicate (Noonan Reference Noonan and Shopen2007: 101).

2.3.1 Complement-taking predicates (CTPs) and their complements

Noonan (Reference Noonan and Shopen2007: 52) describes complementation as ‘the syntactic situation that arises when a notional sentence or predication is an argument of a predicate’. The argument can be a finite clause, or a non-finite clause. Thus, the complement clauses analysed here are either finite clauses introduced by that or a zero complementiser or non-finite clauses.

In his discussion of the semantics of verbal complementation, Noonan (Reference Noonan and Shopen2007) points out that the type of complement clause is determined by the meaning of the complement-taking predicate. He states: ‘Complementation is basically a matter of matching a particular complement type to a particular complement-taking predicate’ (Noonan Reference Noonan and Shopen2007: 101). Similarly, Hengeveld & Mackenzie (Reference Hengeveld and Lachlan Mackenzie2008: 362) and Hengeveld et al. (Reference Hengeveld, de Souza, Braga and Vendrame2019) state that the semantics of complement-taking predicates licenses different clausal complements defined in terms of FDG layers. For instance, predicates expressing a propositional attitude take a Propositional Content as their complement, while predicates of direct perception take a State of Affairs as their complement. In work on stance adverbs, Keizer (Reference Keizer2020: 7) adds that complement-taking predicates have different selectional properties which determine the type of clausal complement they take, while the type of clausal complement constrains the type of adverb that can occur within it. The focus in this article is on discovering whether the constraints of the complement clause apply to evidential adverbs. It should be noted that authors classify complement-taking predicates differently into various narrower or broader categories. Various similar divisions can be found in Dik & Hengeveld (Reference Dik and Hengeveld1991: 234–7), Genee (Reference Genee1998), Noonan (Reference Noonan and Shopen2007) and Wurmbrand & Lohninger (Reference Wurmbrand, Lohninger, Hartmann and Wöllstein2019), inspired by Givón (Reference Givón1980). Hengeveld & Mackenzie (Reference Hengeveld and Lachlan Mackenzie2008: 362) have identified five types of complement clauses using the FDG scopal hierarchy, which is the classification adopted here, as it is also applied to the classification of evidential adverbs in this article. In table 6, Noonan's influential (Reference Noonan and Shopen2007) classification is compared to the one developed within FDG. In the left-hand column of table 6 are Noonan's labels for the various complement-taking predicates, while examples of English predicates are found in the middle column. To the right are the relevant FDG layers of the complements of the complement-taking predicates.

Table 6. Clausal complement types

2.3.2 Matching

The notion of matching is used for the alignment of the semantics or selectional criteria of a complement as determined by the complement-taking predicates with the semantics of an evidential adverb in that complement clause. The term mismatch is preferred to ‘lack of licensing’ as this would seem to involve infelicity while a mismatch of FDG categories may not always be infelicitous. A mismatch is the non-alignment of linguistic categories, which could imply that other mechanisms are at work.

From two studies, it does appear that matches occur most often. Bastos et al. (Reference Bastos, Casseb-Galvão, Gonçalves, Dall'Aglio Hattnher, Hengeveld, Sousa and Vendrame2007: 195) show that modifying modal expressions in complement clauses of complement-taking predicates pertain either to the layer required by the complement clause or to a lower layer, but never to a higher layer. Keizer (Reference Keizer2015: 210) discusses the use of various modifiers in complement clauses which correspond to the semantics of that complement. This article expects that an evidential adverb in a complement clause will align with the semantic category of the complement category as in (5).

(5) I assume that Jane presumably used the car. (author's example)

(6) ?I assume that Jane reportedly used the car. (author's example)

Thus, a verb that expresses a propositional attitude such as judge/assume in (5) embeds a complement clause that denotes a Propositional Content. Such a complement clause is predicted to license an evidential adverb of the same Propositional Content layer, such as presumably as in (5), or that of a lower level but not that of a higher level, such as reportedly as in (6).

Table 7 visualises a matching scheme for complement clauses and evidential adverbs within the FDG hierarchy. It allows us to read off predictions based on the scopal capacity of the layer of the clausal complement to determine the type of modifier that can be expected to occur in the complement clause. The expectation is that there will be no instances occurring in the shaded cells as these would be mismatches.

Table 7. Matches and mismatches (from Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Lachlan Mackenzie2008: 363; Bastos Reference Bastos, Casseb-Galvão, Gonçalves, Dall'Aglio Hattnher, Hengeveld, Sousa and Vendrame2007: 203)

Row 2 of table 7 shows the layers that pertain to complement clauses, while column 1 lists categories of evidential adverbs. An asterisk (*) or a plus sign (+) marks matches and indicates the selectional criteria of the complement clause. An asterisk marks that the complement clause and the evidential are at the same FDG layer, so it represents the highest possible match. A plus sign marks that the evidential adverb is at a lower layer than the complement clause. Thus, the Propositional Content layer of assume in (5) would intersect with the row of the inferential adverbs to which presumably belongs and would form a match. Example (6) would form an intersection of the Propositional Content column with the row of reportative adverb types, which is a grey-shaded cell indicating a mismatch. All predictions regarding evidential adverbs that can occur within the various clausal complement types can be read off table 7 in the same way.

There are two further predictions resulting from table 7 to be pointed out here. Firstly, as all evidential adverbs are either of the same layer or of a lower layer than the Communicative Content layer (C), there can only be matches between evidential adverbs and complement clauses at this layer. Secondly, as there are no evidential adverbs within the layer of the Configurational Property (see section 2.2.4), no matches with the category of this type of complement clause can be established.

2.4 Anchoring of evidential adverbs in complement clauses

As mentioned in section 2.2.3, we do not adopt the term speaker-orientation in relation to evidential adverbs. The difference between anchoring and speaker-orientation will be discussed first and then the difference between current speaker anchors and actor anchors.

Ernst (Reference Ernst2002: 104) does recognise that there is a difference between other speaker-oriented adverbs, such as the evaluative luckily, and evidential adverbs, but his analysis of the difference does not go further. What is expressed by the adverb luckily is the speaker's own evaluation with respect to a proposition and, therefore, the adverb is speaker-oriented. However, an evidential adverb expresses the relation of a proposition to the source of the information or knowledge base. The person who is responsible for using the evidential adverb to indicate the type of source involved is the anchor. We have seen that the anchor of an evidential adverb can be either the current speaker, as seen in example (2), or the actor of the matrix clause, as seen in (1). The actor anchor may be the subject of an active or of a passive matrix clause.

The distinction between the role of the current speaker and the actor of the matrix clause is found in other works. The notion, if not the label itself, is found in van der Leek (Reference Leek van der1989: 230–1) with respect to verbs of perception. In Keizer (Reference Keizer, Keizer and Olbertz2018: 74), an instance of frankly in the complement of an utterance predicate leads to a distinction being made between the reporting speaker and the reported speaker, which is mirrored by current speaker anchor and the actor anchor used here. Haegeman (Reference Haegeman2006: 1666) uses the term anchoring and suggests that ‘the upper layer of the left periphery’, which we are not considering here, is dependent on speaker anchoring.

The present article investigates not only the capacity of the complement clause of a complement-taking predicate, but also the influence of the type of evidential anchor in determining which type of evidential adverb can occur in the complement clause.

3 Predictions

Table 7 provides predictions for the co-occurrence of the five types of clausal complement and four types of evidential adverb. The predictions noted in section 2.3.2 are listed here. Predictions 1(a–c) concern matches between the categories of complement clauses and categories of evidential adverbs. Prediction 2 concerns the capacity of the current speaker anchor to override the constraints of the complement clause.

1.

(a) No evidential adverb will be of a higher layer than the complement which contains it.

(b) As there are no evidential adverbs at the layer of Configurational Property, no matches will occur with complement clauses of this layer.

(c) There can only be matches between evidential adverbs and complement clauses of the Communicative Content Layer as this layer contains all the other layers of concern.

2. Should there be no alignment between the evidential adverb and the complement clause, it is expected that the current speaker will be responsible for the evidential adverb and override the constraints of the complement clause. This means that in cases of a mismatch, the current speaker will be the anchor of the evidential adverb.

4 Material and methods

This section describes the data collection, which adverbs were searched and where the instances were accessed. Furthermore, this section recounts how the complement clauses were extracted and the present data subset finalised.

Firstly, the evidential adverbs in Quirk et al.'s (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 620) list of Content disjuncts were searched in the Oxford English Dictionary (2018) and Collins English Dictionary (2018) for frequency. To ensure sufficient instances of the occurrence of all the evidential adverbs in the dataset, it was necessary to search for adverbs with high frequency. The ten most frequent adverbs were selected both for Kemp Reference Kemp2018 and for this article. Visibly was added to the list to include an adverb of event perception. Other adverbs of perception, such as audibly, were too infrequent to be included in the research.

The data used for this study were gathered from the Great Britain (GB) section of the News on the Web (NOW), BYU Corpus (Davies Reference Davies2010–present). The GB section of the BYU comprises texts from various types of newspapers and magazines of the United Kingdom. However, non-UK newspapers slipped into the search results and were removed manually and replaced by new examples from the extracted data. The data were collected automatically from the corpus covering the period from 2010 to 30 June 2018. The first items that resulted from the corpus search for a particular adverb were extracted. Instances of the highly frequent adverbs were mostly dated 2018 or 2017.

Initially, 1,100 instances of each adverb were extracted from the NOW corpus. These were randomised for estimating the frequency of evidential adverbs in main clauses in the first 50 instances from UK newspapers (Kemp Reference Kemp2018). For this article, all the non-UK instances and double instances of the same date and source were removed from all the lists of adverbs, which in some cases meant removing up to 50 instances. Subsequently, the first 1,000 instances in each list were used to form the present dataset. However, only 833 instances of purportedly remained.

All instances in the dataset were searched to locate verbal complement clauses which were then extracted manually to form a data subset. This was judged to be the most secure method of extraction because of the different forms that complement clauses can take. They can be finite with or without a complementiser, or non-finite with a bare infinitive, a to-infinitive or an -ing form (Hengeveld et al. Reference Hengeveld, de Souza, Braga and Vendrame2019: 277).

A total of 101 complement clauses, all declaratives, which contain an evidential adverb, were identified, which is 0.9 per cent of all the instances in the dataset.Footnote 2 Examples in which the evidential adverb was set off from the complement clause by commas were excluded from the research. Because the data are written, we rely on the absence of commas to tell us that the adverb would, in speech, be prosodically integrated in the clause.

The data subset of complements of complement-taking predicates was first classified into five types of clausal complements based on FDG criteria for complement clauses (see table 6). The data subset was subsequently classified according to the four categories of evidential adverbs (see table 5), and finally for type of anchor. If the actor of the matrix clause was first person and the verb was in the present tense, the anchor was noted as a speaker-anchor. In determining anchor types, it was necessary to establish whether the evidential adverb had appeared in the original text as in (1) or had been inserted by the current speaker/writer in recording the information from a knowledge base as in (2). Furthermore, for the classification of anchor-type, it was sometimes necessary to read more context in the original source than that provided by the corpus interface.

5 Results and prediction 1

The results of the analysis pertaining to prediction 1, which concerns matches and mismatches, are presented in table 8. The numbers represent instances in the data subset occurring at the intersection of type of clausal complement, and type of evidential adverb. The empty cells show that no instances with these values were attested in the data subset. The grey shaded cells show where mismatches were found.

Table 8. Results

The columns in table 8 make clear that evidential adverbs in the data occur in all five categories of clausal complements of complement-taking predicates. The results show that prediction (1a) is partially met. In 70 cases, the prediction of matches between the category of evidential adverbs and that of the complement clauses is met whereas in 31 cases, there are mismatches. As predicted in (1b), because there are no evidential adverbs that belong to the Layer of the Configurational Property (fc) or a further lower layer, the complement clauses of the Configurational Property (fc) cannot result in matches. Also, as predicted in (1c) and seen in the second column of table 8, there are only matches in the column of the Communicated Content complement type.

Examples (1), (2), (7), (8) and (9) are matches in which the complement clause and the evidential adverb are at the same FDG layer. Examples (1) and (2) are examples of matches at the Communicative Content Layer of the Interpersonal Level, while examples (7), (8) and (9) illustrate matches on the Representational Level.

(7) We do know that Tesla and Elon Musk have seemingly made some U-turns regarding the actual construction of the Model Y since that first announcement. (GB 18-05-03)

In (7) there is a match with the clausal complement of the Propositional Content type (p) of the complement-taking predicate know and an inferential (p) adverb seemingly.

(8) I saw the game and noticed you obviously need a bit of work done. (GB 18-06-02)

Example (8) is a match between an episode type (ep) clausal complement of the predicate notice and an evidential adverb of deduction (ep) obviously.

(9) Ralfs was seen visibly shaking in the dock as His Honour Judge Peter Ralls QC sentenced him to two-years imprisonment, one-year for each offence. (GB 17-07-17)

Example (9) shows a match comprising a clausal complement of the event perception type (e) of the complement-taking predicate see with the evidential adverb of event perception (e) visibly.

6 Results and prediction 2

The co-occurrence of the anchor type, type of complement clause, and type of evidential adverb is discussed in this section based on the results in table 9.

Table 9. Results with the current speaker and actor anchor

Key: CSp is current speaker

6.1 Results table

The results in table 9 address prediction 2 given in section 3, which says that in the case of a mismatch, the current speaker will be the anchor of the evidential adverb in the complement clause. In addition to the number of instances of matches and mismatches shown in table 8, table 9 breaks down the result columns into two: the current speaker anchor (CSp) and the actor anchor (Actor). The numbers represent the instances that occur at the intersection of type of clausal complement, type of evidential adverb and type of anchor. The empty cells show that no instances with these values were attested in the data subset.

The results concerning mismatches, matches and anchor type are discussed below. Section 6.2 discusses the anchor type in mismatches, which occur only on the Representational Level, followed by a discussion in section 6.3 of the anchor type with matches and finally the ambiguity of anchor in section 6.4.

6.2 Mismatches and current speaker anchor

Table 9 shows that the dataset confirms the prediction that mismatches on the Representational Level, which are found in the shaded cells, have a current speaker anchor, which overrides the constraints of the complement clause. The 31 instances of mismatches occurring on the Representational Level involve clausal complements of the Propositional Layer, Episode Layer, the State of Affairs and the Layer of the Configurational Property. Examples (10), (11), (12) and (13) illustrate mismatches with a current speaker anchor at these layers.

Example (10) is a mismatch involving a complement clause of the predicate know expressing awareness, which is at the highest layer of the Representational Level, the Propositional Layer.

(10) ‘I know I'm supposedly worth £8m but somehow I've managed to find £50m in my piggybank and the EFL have seen that, so no problem’. (GB 18-05-24)

The complement clause of the complement-taking predicate know in the mismatch in (10) contains the reportative supposedly, which is an evidential adverb of the Communicated Content Layer on the Interpersonal Level. Here, the first person is potentially both an actor anchor and a current speaker anchor. It appears that the two anchors compete. However, the current speaker remains in control of what is said and therefore this instance is characterised as having a current speaker anchor

Example (11) is a mismatch with a complement clause of the Episode layer licensed by the predicate regret, which expresses an emotion.

(11) But Baroness Buscombe, who stood down as chairwoman of the watchdog last year, accused publisher News International of misleading her. ‘I regret that I was clearly misled by News International, that I accepted what they had told me’, she told the hearing. (GB 12-02-07)

In (11) the inferential adverb clearly is of a higher evidential category than the complement clause. Like (10), example (11) has a first-person pronoun as the subject of the complement-taking predicate and of the passive complement clause. This instance too is characterised as having a current speaker anchor.

Example (12) is a mismatch in a clausal complement of see on the layer of Event Perception with a higher reportative evidential adverb of the Communicated Content Layer.

(12) Homeowners Nigel and Ceri Ash, 58, say they were woken by the children's screams and ran into the bedroom to see Jenkins allegedly holding the knife above the baby girl. (GB 15-05-18)

A reading of (12) with an actor anchor of the reportative evidential adverb allegedly would be highly unlikely as the homeowners are recounting their own experience, not a reported experience. Therefore, it can be concluded that the current speaker anchor has inserted reportative allegedly into the complement clause

In the data subset, we find further mismatches in the lower FDG layers, as in (13), which recounts the reaction of television presenters. Visibly has a current speaker anchor as it is the teller and speaker who perceives Rice and Peston squirming.

(13) Coronation Street star Sally Dynevor and comedian Micky Flanagan get off entirely scot-free (in fact, they might as well not have turned up) this week, but TV presenter Anneka Rice and in particular Robert Peston are left visibly squirming. (GB 18-04-13)

Text (13) involves an evidential adverb of Event Perception (e) visibly used in a non-finite complement clause of the lower Configurational Property type (fc), which is an argument of the complement-taking predicate leave. Here, the speaker is recounting events and is the current speaker anchor.

6.3 Matches with actor or current speaker anchor

Unlike mismatches on the Representational Level discussed in section 6.2, which are all current speaker anchored, matches either have a current speaker anchor (CSp), or an actor anchor when the anchor is the subject of the complement-taking predicate. In table 9, we see that most of the category matches have a current speaker (CSp) as their anchor, a finding to which I return in the conclusion. First, I will discuss instances of matches with an actor anchor, and then matches with a current speaker anchor for which the decision on anchor type depended on context. Finally, we will see one instance of a match for which it was very difficult to determine the anchor.

6.3.1 Matches with an actor anchor

Instances of matches in table 9 with an actor anchor have quotation marks around the section of the complement clause with the evidential adverbs, such as (1), repeated here for convenience as (14).

(14) Deputy Supreme Court president Lord Mance said the present law ‘clearly needs radical reconsideration’ and that the opinion of the court … cannot be safely ignored. (GB18-06-07)

The quotation marks around Lord Mance's words in (14) indicate that Lord Mance, who is the subject of the complement-taking predicate, is not only the person who entertains the conclusion of the reasoning but also the person who records it, and he is, therefore, the actor anchor of the adverb clearly.

Similarly, we see in (15) and (16) that there is a section of the complement clause in quotation marks. These sections contain the words of the subject of the matrix clause who is responsible for the use of the evidential adverb and is therefore the actor anchor.

(15) Mexico's transport department said on its website that ‘during take-off (the plane) apparently suffered a problem and dived to the ground’. (GB 18-05-19)

(16) Another man, 27, from Barton Hill was arrested after police ‘spotted him apparently selling items to a known drug user on Unity Street in St Philips’. (GB 18-05-30)

In (15), there is a match at the same FDG layer: a reportative adverb, apparently, in a Communicated Content complement clause. Here, the transport department is the actor anchor. In (16), there is an adverb of deduction, apparently, in a complement clause of the Episode type. Here the police are the actor anchor.

6.3.2 Matches with a current speaker anchor

In some instances in the complement clause category of the Communicated Content, it was only possible to decide on the category of the evidential adverb and its anchor by referring to other material. Such an example is found in (17).

(17) The body of the unfortunate Mrs Emsley was found in a room full of rolls of wallpaper, to which she had apparently led her assailant. McKay reports that she had evidently bought up a large consignment and had been trying to find buyers for it, but he is mystified as to what role the paper played in the crime. (GB 17-09-06)

In (17), if McKay had seen a photo of the murder scene, the adverb evidently would have been one of deduction involving perception and conclusion. The anchor of the adverb would then have been McKay, the subject of the complement-taking predicate. However, in the book by McKay, referred to in the newspaper article, a police report is quoted stating that Mrs Emsley had bought up rolls of wallpaper. The current speaker and writer of the article in The Spectator is reporting on information in the police report in McKay's book and uses evidently as a reportative evidential adverb. The current speaker and writer of the article in The Spectator is, therefore, the anchor of evidently.

In matches, subjects of the matrix clause can be a proposition (18) or an inanimate referent (19).

(18) Both Prince George and Princess Charlotte are believed to have been born by a natural delivery, meaning the Duchess of Cambridge will presumably be planning to have a natural birth this time as well. (GB 18-04-23)

In (18) both the complement clause and the evidential adverb are of the same layer, that of the Propositional Content. Here, the current speaker is drawing the conclusion, and is the current speaker anchor of presumably.

In (19) there is a complement-taking predicate with an inanimate referent as subject with a current speaker anchor. The complement clause of the predicate show and the evidential adverb seemingly are both on the Episode Layer.

(19) Footage of how the installation was made also shows the activists seemingly luring the city's rats with McDonald's food, Trump's favourite. (GB 18-03-31)

6.4 Ambiguity of the anchor

Sometimes, as in (20), it is not possible to solve potential ambiguity in the anchor type by referring to further available material.

(20) Newsnight has previously reported that his successor, Kate Emms, was allegedly bullied by the Speaker – a claim Mr Bercow denies. (GB 18-05-02)

Both the evidential adverb, allegedly and the complement clause in (20) are of the Layer of Communicated content. Here, however, it is not possible to determine who the anchor of allegedly is. It could be the programme Newsnight, which is the subject of the matrix clause, or it could be the current speaker.

7 Summary and discussion

The aim of the article is to explore whether the semantics of the complement clause of a complement-taking predicate and the anchor of the adverb determine the type of evidential adverb occurring in that clause. The search for target clauses in the dataset of eleven evidential adverbs revealed very few instances. A total of 101 target clauses, which is 0.9 per cent of the dataset, were found within about 10,800 instances in the corpus of recent UK newspaper and magazine texts. The occurrences of evidential adverbs in this clause type are far fewer than those attested in main clauses (Kemp Reference Kemp2018). All the 101 sentences in the data subset contained complement clauses of a complement-taking predicate with evidential adverbs that inform the reader about the source or knowledge base from which the content of the complement clause came.

From the high proportion of matches in the data subset, it can be concluded that the type of evidential adverb occurring in a complement clause can to a large extent be predicted by the semantics of the complement clause of the complement-taking predicate. Matches occur with a current speaker anchor and with an actor anchor. From the results, it can be predicted that an evidential adverb with an actor anchor will align with the category of the complement clause and thus produce a match.

However, FDG category mismatches do occur in the data subset. All these mismatches have a current speaker anchor. As the constraints of the clausal complement on the evidential adverb in the complement clause do not hold in mismatches, it is concluded that the current speaker may override the licensing capacity of the complement clause. The current speaker can use an evidential adverb of a higher layer than that of the surrounding complement clause. The adverbs are then current speaker driven rather than complement clause determined.

Mismatches in the results of this analysis show that evidential adverbs in English do not act in the same way as modal modifiers of complement clauses as recorded for Brazilian Portuguese in Bastos et al. (Reference Bastos, Casseb-Galvão, Gonçalves, Dall'Aglio Hattnher, Hengeveld, Sousa and Vendrame2007), despite the FDG predictions for both languages being the same. In Bastos et al. (Reference Bastos, Casseb-Galvão, Gonçalves, Dall'Aglio Hattnher, Hengeveld, Sousa and Vendrame2007), none of the modifiers in the complement clauses pertains to FDG layers higher than that of the complement clause of the complement-taking predicate. In the present study, there are 31 examples of evidential adverbs that pertain to a layer higher than that licensed by the complement-taking predicate. From this perspective, the results are similar to those of Keizer (Reference Keizer, Keizer and Olbertz2018) in which a number of instances of the high layer illocutionary frankly occurred within complement clauses of a lower layer.

Keizer (Reference Keizer, Keizer and Olbertz2018) also discovered some mismatches, or as she calls them, ‘unexpected instances’, in complement clauses in which the target adverb occurred in quotations from other sources. Keizer's (Reference Keizer, Keizer and Olbertz2018) analysis viewed the quoted items as embedded Discourse Acts, which were then not limited by the constraints of the complement clause. In the present data subset, however, quotations in the complement clause occur with matches, not mismatches. I conclude that mismatches occur because the current speaker overrides the constraints of the complement clause. Further support for this argument is found in instances of mismatches with first-person pronoun subject in the matrix clause where there is potential competition between anchors (section 6.2), but the speaker wins out.

Furthermore, Keizer (Reference Keizer, Keizer and Olbertz2018) considers two cases of interpersonal frankly infelicitous because it was difficult to decipher who was being frank, and therefore difficult to understand. I do not consider any of the instances in the present data subset infelicitous but do think that the potential ambiguity of the anchor could discourage the use of the target configuration. This might well be the reason for there being so few examples in the data subset, which is written and typically edited. It should be noted that similar research into a genre such as casual UK spoken language, or a study focusing on evidential adverbs of lower frequency might render a different balance of results than that found here.

It should also be noted that rather than the predicted actor anchor, current speaker anchoring is the norm rather than the exception in the data. That mismatches are current speaker anchored illustrates the potential of the current speaker to determine the type of evidential adverb occurring in a complement clause. However, the absence of mismatches with actor anchoring serves to support the view that the complement-taking predicate does, indeed, have the capacity to determine the type of evidential adverb in the complement clause.

8 Conclusions

In this article we applied FDG to tease apart the influences on the choice of evidential adverb in complement clauses. In many cases but not all, the category of the evidential adverb with a current speaker anchor did align with the category of the complement clause, which is, in turn, determined by the complement-taking predicate. However, while there were mismatches between complement clauses and evidential adverbs with current speaker anchors, there were no mismatches with actor anchors. It can be concluded that it is not only the nature of the complement clause that determines which evidential adverb can be used in a clausal complement, but that in some instances the current speaker anchor can override the semantic restrictions of the complement clause. From the results of the analysis of the data, it can be confirmed that when there is an actor anchor, the evidential adverb will align with constraints of the complement clause.

It does appear from this work that it is not only the nature of the complement clause and the nature of the evidential adverb that determine the type of evidential adverb that occurs in a complement clause, but also the anchor of the evidential adverb. This shows us that the type of anchor has a role to play in accounting for the distribution of evidential adverbs in complement clauses of complement-taking predicates.