1 Introduction

Research on glottal replacement,Footnote 2 as in (1a–fFootnote 3), has demonstrated that it ‘is one of the most dramatic, wide-spread and rapid changes to have occurred in British English in recent times’ (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1999: 136).

- (1)

(a) One thing about the old post office, you were pre[ʔ]y well ki[t]ed ou[t]. (Jock, older male)

(b) It was be[t]er when we was at school. Aye, it really was be[ʔ]er. (Donald, older male)

(c) He's go[t] it all se[ʔ] up now as well. (Karl, middle-aged male)

(d) I was a bi[ʔ] annoyed a[t] i[ʔ]. (Rose, older female)

(e) Ha[t]ed high school, ha[ʔ]ed it. (Meadow, young female)

(f) A month la[ʔ]er, that's when all the jobs star[ʔ]ed ge[ʔ]ing cu[t]. (Kevin, young male)

Glottal replacement has become ubiquitous in the British Isles in the twenty-first century, with use attested in the southern counties of England and Wales (e.g. Tollfree Reference Tollfree1999; Mees & Collins Reference Mees and Collins1999; Straw & Patrick Reference Straw and Patrick2007), the north of England (Docherty et al. Reference Docherty, Foulkes, Milroy, Milroy and Walshaw1997; Docherty & Foulkes Reference Docherty and Foulkes1999; Mathisen Reference Mathisen1999; Stoddart, Upton & Widdowson Reference Stoddart, Upton and Widdowson1999; Llamas Reference Llamas2007; Richards Reference Richards2008; Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2012; Baranowski & Turton Reference Baranowski and Turton2014) and Scotland (Romaine & Reid Reference Romaine and Reid1976; Macaulay Reference Macaulay1977, Reference Macaulay1991; Reid Reference Reid and Trudgill1978; Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999) including the northeast (Marshall Reference Marshall2001), working-class speakers (Williams & Kerswill Reference Williams and Kerswill1999; Flynn Reference Flynn2012) and RP speakers (Fabricius Reference Fabricius2000; Tollfree Reference Tollfree1999), first language and second language speakers (Drummond Reference Drummond2011; Schleef Reference Schleef2013), and in both casual and careful speech (Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999); in both males and females (e.g. Williams & Kerswill Reference Williams and Kerswill1999; Mees & Collins Reference Mees and Collins1999). Glottal replacement may have started as a stereotype of urban speech (e.g. Milroy et al. Reference Milroy, Milroy, Hartley and Walshaw1994: 328) but such is its ubiquity that it is fast becoming a stereotype of British speech more generally.

Both the speed and spread of change across the UK have made glottal replacement something of a ‘poster child’ for studies of language variation. Thus while it might have been the case some twenty years ago that we did not ‘as yet have an idea of how [glottal replacement] operate[s] in different dialects in the British Isles’ (Milroy et al. Reference Milroy, Milroy, Hartley and Walshaw1994: 350), we now have much more information on the processes at work in the rise of this iconic variable. Despite this, some key questions remain surrounding the origins and subsequent development of the variable across time and space. Specifically, ‘whilst it would be tempting to view the spread of glottalization in late twentieth century English as a change originating in lower class London English’ (Beal Reference Beal2014: 166), with monogenetic roots spreading outwards to the rest of the UK, the historical record suggests that it may, in fact, have polygenetic roots. For example, in Andrésen's (Reference Andrésen1968) detailed historical study of the form, he cites Bell (Reference Bell1860) as noting the form in the west of Scotland as far back as the mid nineteenth century and also Sweet's (Reference Sweet1908) observation that it occurs at the beginning of the twentieth century in ‘some North English and Scotch dialects’. This leads Andrésen (Reference Andrésen1968: 18) to suggest that glottal replacement first appeared in the west of Scotland, and in particular, Glasgow, and subsequently spread to the east of Scotland and the far north of England some years later. Further south, SED evidence leads Trudgill (Reference Trudgill1999: 136) to suggest that it spread from Norwich to London and not vice versa. Thus we may have a shared outcome – rapid increase in use of [ʔ] across all dialects studied to date in the UK – but one which may arise from different roots. This is exemplified most strikingly by Stuart-Smith's (Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 201) study of glottal replacement in Glasgow where she finds ‘two distinct types of allophonic patterning, possibly reflecting the Scots/Scottish Standard English linguistic heritage of working class and middle class speakers respectively’. In other words, the same change via two different sources.

As highlighted by the above, ‘satisfactory accounts of the trajectory of the change must take into account its embedding in the local dialects of different regions and the history of those dialects’ (Milroy et al. Reference Milroy, Milroy, Hartley and Walshaw1994: 350). This may, in turn, elucidate the roots and subsequent development of the change from [t] to [ʔ]. In this article we contribute to our understanding of the trajectory of change through an in-depth analysis of a dialect spoken in the northeast periphery of Scotland, Buckie, an area which is distant both geographically and linguistically from the putative ‘home’ of glottal replacement in the west of Scotland. By examining the social and linguistic constraints across three generations of speakers, we will be able to shed light on where this variable came from and how and when the innovation took hold. This, in turn, will contribute to our understanding of how this iconic variable spreads across time and space.

2 Previous research

While the roots of glottal replacement as gleaned from the historical record may be subject to debate, what is clear is that it is extremely prevalent in the British Isles in the twenty-first century – all varieties studied to date demonstrate a sharp rise in this variant across the generations (e.g. Docherty & Foulkes Reference Docherty and Foulkes1999: 50; Flynn Reference Flynn2012: 294; Macaulay Reference Macaulay1977: 45; Marshall Reference Marshall2001: 54; Mathisen Reference Mathisen1999: 110; Stoddart, Upton & Widdowson Reference Stoddart, Upton and Widdowson1999: 75; Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 191). The progression of this variant across the social and linguistic spheres highlights both similarities and differences within and between the varieties studied, as detailed below.

2.1 Linguistic context

Perhaps not surprisingly, all studies show that the linguistic contexts in which the variable occurs have a significant influence on variant choice (Docherty et al. Reference Docherty, Foulkes, Milroy, Milroy and Walshaw1997: 294; Docherty & Foulkes Reference Docherty and Foulkes1999: 50; Drummond Reference Drummond2011: 292; Flynn Reference Flynn2012: 292), with a number of key findings emerging from previous research.

The majority of studies show that there are much lower rates of glottal replacement in word-medial, ambisyllabic contexts, as in (2a) and (2b), when compared to word-final contexts as in (2c) (e.g. Wells Reference Wells1997: 19–21; Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 192; Flynn Reference Flynn2012: 294; Fabricius Reference Fabricius2002: 120).

- (2)

(a) She's growing tatties and athing in her garden. (Moira, older female)

(b) She was just little and she was playing the piano, ken. (Natalie, middle-aged female)

(c) Ken five o'clock in the evening 'til nine o'clock at night. (Rachel, middle-aged female)

Within codas, three environments are typically compared: pre-consonantal (PreC) as in (3a), pre-vocalic (PreV) (3b) and pre-pausal (PreP) (3c).

- (3)

(a) And we did na get there 'til like half seven. (Beverley, young female)

(b) Aye we'd a lot of fun at Cullen Bay. (Lainey, middle-aged female)

(c) Oh nah, I've never been to it. (Keifer, young male)

A dominant constraint hierarchy for variable glottal replacement emerges in these coda environments across most studies conducted in more southern areas of the UK: PreC > PreP > PreV. This pattern is attested in London, both for the vernacular and RP (Tollfree Reference Tollfree1999: 171), Reading and Milton Keynes (Williams & Kerswill Reference Williams and Kerswill1999: 147) and Cardiff (Mees & Collins Reference Mees and Collins1999: 198). More northern varieties also exhibit this hierarchy: in Nottingham (Flynn Reference Flynn2012: 294), Derby (Docherty & Foulkes Reference Docherty and Foulkes1999: 50–1), Hull (Williams & Kerswill Reference Williams and Kerswill1999: 147) and Sandwell (Mathisen Reference Mathisen1999: 115). So widespread is this ordering of constraints that Straw & Patrick (Reference Straw and Patrick2007: 390) refer to it as the diffusion pattern, referring to both its geographical spread across different regions and also its spread through the different linguistic environments. This may suggest that glottal replacement is ‘diffusing as a package from a London epicenter’ (Milroy 2007: 164), but a number of ‘regional particularities’ are also noted which may point towards a polygenetic root (Schleef Reference Schleef2013: 203). This is particularly the case in Tyneside (Milroy et al. Reference Milroy, Milroy, Hartley and Walshaw1994: 341), where the hierarchy is PreC > PreV > V_V > PreP, and Scotland, where a number of different hierarchies are reported both between and within the same variety (see Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 194–5).Footnote 4

2.2 Social constraints

A complicated interplay between gender, class and style is evident in previous research (e.g. Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 194; Fabricius Reference Fabricius2000: 141). This interaction is exemplified in the apparently contradictory results for gender: in some communities, males lead the change (Macaulay Reference Macaulay1977: 45; Marshall Reference Marshall2001: 54; Kerswill Reference Kerswill, Britain and Cheshire2003: 230–1), in others, females are in the lead (Mathisen Reference Mathisen1999: 17; Kerswill Reference Kerswill, Britain and Cheshire2003: 230–1; Milroy et al. Reference Milroy, Milroy, Hartley and Walshaw1994: 341) and others still report no gender difference in the progress of the change (Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 199–200; Schleef Reference Schleef2013: 211).

Given that [ʔ] is the stigmatised form, the finding that males lead the change in many varieties is not surprising (e.g. Labov 2001: 293). Trickier to explain is the finding that middle-class females use higher rates of [ʔ] than middle-class males (e.g. Mees Reference Mees1987 – cited in Mees & Collins Reference Mees and Collins1999: 192; Watt & Milroy Reference Watt and Milroy1999: 30; Mathisen Reference Mathisen1999: 110). These findings have led Milroy et al. (Reference Milroy, Milroy, Hartley and Walshaw1994: 336–7) and Mees (Reference Mees1987) to suggest that women favour glottal replacement when it is associated with supralocal norms (as opposed to a local variant, as is the case for glottal reinforcement in Tyneside, for example). Further, a lack of gender differences can be explained by the stage of change, specifically the gender gap neutralizes as glottal replacement increases. This is demonstrated by Stuart-Smith's (Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 200) real-time comparison of Macaulay and Trevelyan's (Reference Macaulay1973) findings in Glasgow with her data from the 1990s, where the gender differences demonstrated in earlier stages of the change disappear in the later stages. Thus these apparently contradictory findings for gender are explained through reference to the local status of the variant and the stage of change within that community.

Situational context is further implicated in the rise of this variable, both in terms of the classic sociolinguistic treatment of style and also in terms of the effects of interlocutor. As glottal replacement has been described as one of the ‘most heavily stigmatized features of British English’ (Milroy et al. Reference Milroy, Milroy, Hartley and Walshaw1994: 4) and ‘widely regarded as ugly and also a lazy sound’ (Wells Reference Wells1982: 35), it is not surprising that studies often report higher rates of use with more informal styles (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1999: 132; Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 191). However, in step with its rapid spread, it may have ‘gone upmarket’ (Fabricius Reference Fabricius2002: 124) as it is increasingly diffusing to more formal styles in younger speakers (Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 199; Marshall Reference Marshall2001: 62). In addition, Trudgill (Reference Trudgill1986: 8) finds that interlocutors may also play a part in influencing rates of use.Footnote 5 In his study of Norwich (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1974) he found that his own rates of glottal replacement correlated with the rates of his interviewee, as demonstrated in figure 1. He suggests that this results from short-term accommodation (e.g. Giles 1973; Coupland 1984), but that such repeated short-term accommodation may in actual fact lead to long-term permanent change: ‘If a speaker accommodates frequently enough to a particular accent or dialect, I would go on to argue, then the accommodation may in time become permanent particularly if attitudinal factors are favourable’ (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986: 39). We examine the potential for interlocutor accommodation through our study's design (section 4.5) and the implications of this process in the spread and development of this feature (see section 5). Before doing so, we first describe the community from which the data are drawn.

Figure 1. Variable (t) rates by interlocutor (based on data from Trudgill Reference Trudgill1974)

3 Data and method

3.1 The community

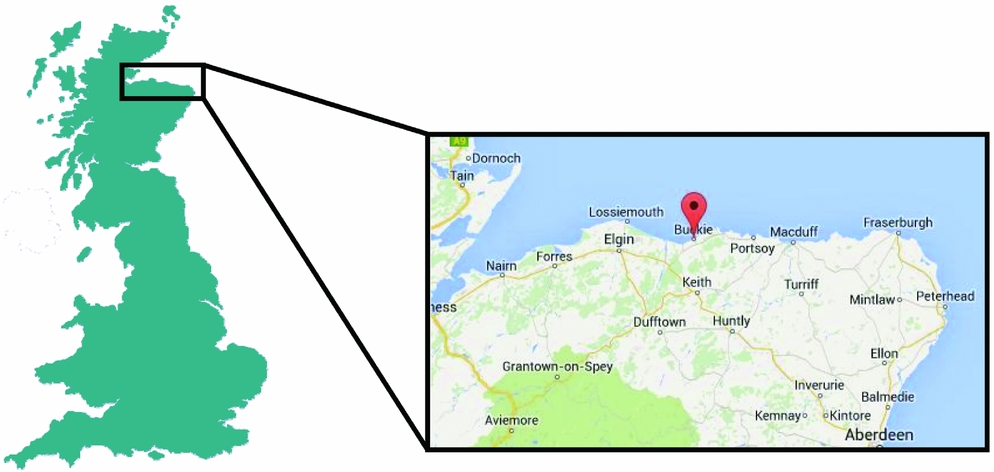

Buckie is a small fishing town situated on the north east coast of Scotland, 60 miles from Aberdeen (see figure 2).

Figure 2. The research site Buckie, Scotland (© Buckie, Moray. Map Data. Google Maps. Google, accessed 5 August 2015)

Due to economic independence as a result of the fishing industry, until recently the community was isolated geographically, socially and culturally from more mainstream norms. Thus Buckie is a classic ‘relic’ area, retaining linguistic forms from the history of English that have long disappeared in other more mainstream varieties. For instance, features such as the Northern Subject Rule, unshifted vowels and the voiceless labio-velar approximant [ʍ] in wh- forms are still in use (Smith Reference Smith2001a, Reference Smith2001b, Reference Smith, Kay, Horobin and Smith2004, Reference Smith, Kirk and Baoill2005). Despite this, glottal replacement is pervasive as indicated by a young male's use in (4):

(4) Um, it's if it happens again that's me to[ʔ]ally ou[ʔ] of football like. 'Cause i[ʔ]'ll keep happening. If I dinna rush into it too fast and just ge[ʔ] it properly sor[ʔ]ed I should be okay. I had physio and they telt me to stop it 'cause I've got to go back and see the orthopaedic. 'Cause something is not right with my scan, bu[ʔ] I'd say it's go[ʔ]en be[ʔ]er since I s- star[ʔ]ed doing the exercises more regularly, basically building up my quads round about the knee and just strengthen it a wee bi[ʔ]y.

3.2 The sample

The sample consists of 24 speakers, stratified by age and gender as shown in table 1, and they were recorded as part of a larger project One Speaker, Two Dialects: Bidialectalism Across the Generations in a Scottish Community (Smith Reference Smith2013–16). To control the sample as much as possible, participant selection is based on the following criteria: 1. both parents born and raised in the community; 2. where applicable, spouse from the community; 3. no more than one year spent away from the community; 4. no education beyond secondary school level.

Table 1. Sample stratified by age and gender

The speakers were recorded twice: first with a community ‘insider’ using classic sociolinguistic interview techniques (Labov Reference Labov, Baugh and Sherzer1984) and second with a community ‘outsider’ to assess the effects of addressee styleshifting (e.g. Bell Reference Bell1984). This design will enable us to examine in detail questions surrounding the role of situational context in governing use of glottal replacement (see section 4.5). Each interview was fully transcribed using Transcriber (Boudahmane, Manta, Antoine, Galliano & Barras Reference Boudahmane, Manta, Antoine, Galliano and Barras2008), creating a speech-to-orthography time-aligned corpus of approximately 1 million words (http://trans.sourceforge.net/en/presentation.php).

3.3 Analysis

As the focus of the present study is on the sociolinguistic correlates of glottal replacement rather than on its acoustic profile, we follow the majority of studies in conducting an auditory analysis of forms (see also Trudgill Reference Trudgill1974; Macaulay Reference Macaulay1977; Mees Reference Mees1987; Milroy et al. Reference Milroy, Milroy, Hartley and Walshaw1994; Mees & Collins Reference Mees and Collins1999; Mathisen Reference Mathisen1999; Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999; Tollfree Reference Tollfree1999; Williams & Kerswill Reference Williams and Kerswill1999; Marshall Reference Marshall2001; Fabricius Reference Fabricius2000; Straw & Patrick Reference Straw and Patrick2007; Llamas Reference Llamas2007; Drummond Reference Drummond2011; Flynn Reference Flynn2012; Schleef Reference Schleef2013; Baranowski & Turton Reference Baranowski and Turton2014).

In order to have sufficient data for statistical analysis, we extracted approx. 100 tokens per speaker per insider/outsider interview (200 tokens in total per speaker), starting at ten minutes into the interview to mitigate the Observer's Paradox (see Labov Reference Labov1972: 209). Ambiguous tokens, i.e. those which were difficult to distinguish auditorily, were discarded from the analysis. These accounted for less than 2 per cent of the overall instances. In accordance with type/token issues (Wolfram Reference Wolfram and Preston1993: 214), high-frequency items such as get, that, it etc. were capped at ten tokens per speaker interview. Tokens with a following non-sonorant consonant, as in (5a,b), were excluded (see also Macaulay Reference Macaulay1991: 33; Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 188; Flynn Reference Flynn2012: 276), due to the tendency for the [t] to assimilate to the following consonant (e.g. Holmes Reference Holmes1994: 441; Shockey Reference Shockey2003: 38).

- (5)

(a) You get it back in an hour. (Adam, middle-aged male)

(b) It's just, you name it, we've got it. (Karl, middle-aged male)

For the remaining data, we took a bottom-up approach, including all other contexts where glottal replacement was observed to occur in the dialect. These included ambisyllabic contexts (6) coda contexts (7), but also onset contexts (8). In the majority of dialects, glottal replacement is generally blocked in onset contexts; this includes both word-initial contexts (take, tear, tiger etc.) and also word-internal foot-initial contexts (attach, attend, guitar, sometimes, tattoo etc.) (e.g. Tollfree Reference Tollfree1999: 171). Not surprisingly, glottal replacement is also blocked in word-initial onset contexts in Buckie. However, our analysis of the data revealed that, for word-internal foot onset contexts (e.g. (8)), glottal replacement is permitted within a range of lexical items.Footnote 6 We therefore extended the variable context to include these environments. During the auditory coding, if a particular lexical item showed variable realisation, it was included within the final analysis Categorical items were excluded. As our analysis is limited to the lexical incidence within our specific corpus of data we cannot provide an exhaustive list of every item where this is permitted within the broader dialect (see further detail in sections 4.3 and 5).

(6) With the daugh[ʔ]ers being away fae home and all. (Joel, older male)

(7) But I did na really enjoy i[ʔ], I would na go back. (Lainey, middle-aged female)

(8) Then some[ʔ]imes the detectives used to come up. (Rhona, middle-aged female)

A total of 4,898 tokens were extracted from the data and then coded for a series of linguistic and social constraints in order to provide a detailed account of the patterning of the variable within the Buckie dialect, and to enable comparison with other varieties.

We first conducted a descriptive exploration of the data, which we used to inform our inferential analysis. In other words, we built the statistical model from the patterns observed in the descriptive data. This process is reflected through our presentation of the results where we begin with an outline of our factor-by-factor analysis of the data followed by multivariate modelling using RBrul (Johnson Reference Johnson2009) in order to test the relative contributions of these factors to the overall variability.

4 Results

4.1 Overall distributions

As noted in previous studies (e.g. Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 188; Straw & Patrick Reference Straw and Patrick2007: 395; Docherty et al. Reference Docherty, Foulkes, Milroy, Milroy and Walshaw1997: 293), a number of different variants can exist in the continuum between [t] and [ʔ]. In our data we identified five variants: [t] alveolar stop with full plosive release (9a); [ʔ] glottal stop (9b); [![]() ] variant with alveolar contact but no oral plosive release (9c); [tʰ] alveolar contact with strongly marked aspirated release (9d), [ɾ] voiced alveolar tap (9e):

] variant with alveolar contact but no oral plosive release (9c); [tʰ] alveolar contact with strongly marked aspirated release (9d), [ɾ] voiced alveolar tap (9e):

- (9)

(a) First drink I ever had was a bo[t]le of hooch. (Neil, young male)

(b) Every Sa[ʔ]urday night and every Monday night, (Jock, older male)

(c) The women all gu[

]ing fish down there but, (Owen, older male)

]ing fish down there but, (Owen, older male)(d) We dumped the whole lo[tʰ]. (Karl, middle-aged male)

(e) Like for[ɾ]y odd pound each for one ticket. (Meadow, young female)

Table 2 shows the overall distribution of these variants, where a full 97 per cent of the data are either [t] or [ʔ], with the remaining variants used very rarely at all. For this reason, we exclude the minority variants and concentrate on a binary distinction between [t] and [ʔ] (see also Drummond Reference Drummond2011; Fabricius Reference Fabricius2000, Reference Fabricius2002; Straw & Patrick Reference Straw and Patrick2007).

Table 2. Overall distribution of all variants

We now examine a series of factors which have been shown to have an important effect on glottal replacement in other varieties: age (as in generational change), linguistic context, gender and situational context. We first turn to the crucial question of change in apparent time.

4.2 Change in apparent time

As indicated in section 2, where data from different generations exist, all studies show an increase in the use of glottal replacement from one generation to the next (e.g. Docherty & Foulkes Reference Docherty and Foulkes1999: 50; Flynn Reference Flynn2012: 294; Macaulay Reference Macaulay1977: 45; Marshall Reference Marshall2001: 54; Mathisen Reference Mathisen1999: 110; Stoddart, Upton & Widdowson Reference Stoddart, Upton and Widdowson1999: 75; Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 191). Figure 3 shows the use of glottal replacement across the three different age cohorts in Buckie and shows a dramatic increase across the three generations – from 38 per cent in the older speakers, to 70 per cent in the middle-aged and a full 90 per cent in the younger speakers. Our initial observation – that glottal replacement is moving fast in this dialect – is fully borne out here.

Figure 3. Overall distribution of [ʔ] by age

While the effects of individual variation will be controlled for by entering speaker into the mixed-effects model as a random factor, it is instructive to first inspect these patterns at a descriptive level (e.g. Guy Reference Guy and Labov1980) to see if all speakers are participating in this fast-moving change. Figure 4 shows the individual rates of variability, where we order the speakers from low to high across each age cohort. The figure shows that all speakers exhibit variable use of glottal replacement. Moreover, interspeaker variability decreases across the generations. For instance, within the older cohort, the range of highest (Donald – 78 per cent) to lowest-rate user (Moira –12 per cent) is 66 per cent. This is compared to the middle-aged, which has a range of 44 per cent (Alex – 86 per cent; Lana – 42 per cent), and the young cohort, which has a range of 24 per cent (Keifer – 98 per cent; Meadow – 74 per cent). These results suggest that as glottal replacement increases everyone in the community participates in the change.

Figure 4. Glottal replacement by individual speaker

The above results indicate that despite being a classic relic area, Buckie looks just like all other dialects that have been studied to date, with a rapid rise in use of the non-standard form and all individuals participating in this change. Note too that two of the older speakers, Joel (71) and Donald (69), show very high rates – around 70 per cent of the time. This suggests that glottal replacement has been used in this peripheral geographic location for a number of generations. We return to the question of just how long glottal replacement has been present in the Buckie dialect in our discussion of its origins and development in section 5.

While the above shows how much speakers use [ʔ], we now turn to the question of where they use it, as this will be crucial in establishing similarities and differences with other dialects and help to inform the trajectory of change.

4.3 Linguistic constraints

As detailed in section 2.1, the linguistic patterning of glottal replacement differs across varieties. Both following phonetic context (Docherty & Foulkes Reference Docherty and Foulkes1999: 50–1; Tollfree Reference Tollfree1999: 171; Williams & Kerswill Reference Williams and Kerswill1999: 147; Flynn Reference Flynn2012: 294; Straw & Patrick Reference Straw and Patrick2007: 164) and word position (e.g. Wells Reference Wells1997: 19–20; Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 192; Fabricius Reference Fabricius2002: 120; Flynn Reference Flynn2012: 294) play a part in governing the variation. In order to capture the important interactions between syllabic position and following phonetic environment, and to account for the full variable context in the current data, we combined syllabic context and following environment within one elaborated category. This resulted in a total of 21 different contexts of use, as detailed in the table A1 in the Appendix. Although these categories provide a detailed descriptive analysis of the possible contexts for glottal replacement in Buckie, they are unwieldy in terms of statistical analysis. Further investigation of these 21 forms revealed a broader set of five categories as shown in table 3. Specifically, for coda contexts we follow previous analyses in dividing the data into Coda#Pause and Coda#Vowel (Coda#Consonant contexts are excluded – see section 3.3). For ambisyllabic contexts, we further divide the data into whether there was a following consonant or vowel. Finally, we include a range of syllable word-internal foot-onset contexts.

Table 3. Linguistic context by syllabic position and following phonetic environment

Figure 5 shows the results when the data are divided by linguistic context and reveals the following more to less hierarchy of use of [ʔ]: Ambi#Syl consonant (bottle)> Coda#Vowel (that is)> Ambi#Vowel (pretty)> Coda#Pause (I like that.)> onset (sometimes). Where comparison is possible, this hierarchy looks very different to other varieties, both quantitatively and qualitatively. For example, note the high rates of the non-standard variant in ambisyllabic contexts – previous research shows that this context is highly disfavoured in other varieties (e.g. Flynn Reference Flynn2012: 294; Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 198) – and the robust use of [ʔ] in onset positions, where many other dialects show only marginal use in this context. We return to these points in section 5.

Figure 5. Glottal replacement by syllable type and following phonetic context

How does this relatively unusual overall pattern travel across the linguistic system as [ʔ] becomes the dominant realisation of /t/ within the variable context? Specifically, is this constraint hierarchy replicated across each of the generations or is there disruption of constraints in the move from minority to majority variant? In his Nottingham data, Flynn (Reference Flynn2012: 294) shows that while the rates of glottal replacement increased, the constraints remained the same. Stuart-Smith (Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 198), on the other hand, finds both maintenance and reorganisation of constraints: the working-class speakers ‘show a systematic allophonic patterning in T-glottalling, which is being maintained by younger speakers’, but within the middle-class speakers, the youngest cohort shows a disruption of constraints and a move towards the more working-class patterns. Figure 6 shows the results by linguistic context across the three generations of speakers in Buckie and reveals that nearly every linguistic context increases across the age groups. Between the generations, there are a number of similarities in the linguistic patterning: the Ambi#Syl context exhibits high levels of the non-standard variant, while the Onset and Coda#Pause environments exhibit lower rates. However, there are some differences in the exact ordering between the different contexts of use which may indicate the developing profile of the change. In the wider comparison with other varieties, the differences are evident across all generations e.g. in the high use of ambi-syllabic contexts. We examine whether these findings are statistically significant in section 4.6 and what they may signal for the development of this feature in the community, and more generally in section 5.Footnote 8

Figure 6. Glottal replacement by age and linguistic context

In addition to linguistic constraints, integral to the spread of a form is its social evaluation within the community, and a number of social influences are reported in the rise of [ʔ]. We turn now to an examination of the role of social factors in the patterning and development of this feature in Buckie, and how these map onto previous findings.

4.4 Social constraints

As detailed in section 2.2, age, class, gender and style have a significant effect on the use of [ʔ]. We cannot test for the effect of class in these data, as our sample comes from working-class speakers only, but we can test for the remaining constraints. We start with gender and pose two questions arising from previous literature: (i) are the males in this working-class community leading the change as previous research has found, and (ii) is the gender effect neutralised as glottal replacement rises through the generations?

Figure 7 shows that both older and middle-aged speakers have a marked difference in their rates of [ʔ] according to gender. In line with previous research (Docherty & Foulkes Reference Docherty and Foulkes1999: 161; Kerswill Reference Kerswill, Britain and Cheshire2003: 232), the working-class males use higher rates of the non-standard form. However, as the change progresses, the gender differences neutralise, as indicated by the matching rates of glottal replacement between the young males and females. In short, the patterns in the Buckie data replicate those found in other studies: males > females and neutralization of gender differences in the progression of change from one variant to another. We will formally test these descriptive statistics in the interaction of age and gender in our multivariate analysis in section 4.6.

Figure 7. Glottal replacement by age and gender

4.5 Situational context

Recall the findings for style, where glottal replacement has higher rates in informal style, but is increasingly diffusing to more formal styles (Mees & Collins Reference Mees and Collins1999: 192; Trudgill Reference Trudgill1999: 132). As such it is said to be losing its stigma, especially among younger speakers. In the current analysis we do not have data which can test for style through formality in any direct way such as e.g. reading lists. What we do have, however, are data with different addressees: each participant was recorded with both a community insider and a community outsider (see section 3.2). The effect of addressee is well attested in sociolinguistic research (e.g. Bell Reference Bell1984). More specifically for the present research, Douglas-Cowie (Reference Douglas-Cowie and Trudgill1978) finds that speakers ‘code-switch’ to more standard variants when talking to a community ‘outsider’. Our own ongoing analyses indicate that when speakers in Buckie are in conversation with the community outsider, there is a shift to standard variants only with variables which are socially salient and/or stigmatised in the community (Smith & Holmes-Elliott Reference Smith and Holmes-Elliott2015). Given the traditional stigmatisation of glottal replacement, we might expect speakers to use lower rates of the glottal variant when in conversation with the community outsider.

To test the effects of addressee with this variable, figure 8 shows the use of [ʔ] by insider and outsider across the different age cohorts. The results demonstrate a slight difference according to addressee for the older speakers, but virtually no difference in the middle-aged or young speakers. Note too that for the older speakers, there are higher rates of [ʔ] when talking to the outsider. This is in stark contrast to Douglas-Cowie (Reference Douglas-Cowie and Trudgill1978) and our own findings for other socially salient variables, where the non-standard variant decreases in conversation with a community outsider. This pattern is further elaborated in figure 9, which shows addressee effect by individual speaker and reveals that the interviewer effects across individuals echo the aggregate effects but here we can see more subtle differences across the individuals. For the older cohort, four speakers have a sizeable difference between insider and outsider – Morven, Jock, Rose and Owen – with three of these four using higher rates of [ʔ] with the outsider. Thus only one speaker, Jock, shows the predicted direction – lower rates of the non-standard form with the community outsider. For the middle-aged speakers, there are less stark differences between insider/outsider, and for the younger, only one speaker – Meadow – shows any difference, with much higher rates when talking to the community outsider. Note that this speaker has the lowest rates of use in the younger cohort when talking to the community insider.

Figure 8. Glottal replacement by age and interviewer

Linguistic context may also be sensitive to situational context, and the interaction of these factors may provide further clues to the differing rates of use as shown in figure 9. Previous research shows that particular linguistic contexts are more likely to styleshift than others. For instance, in her study of RP, Fabricius (Reference Fabricius2002: 125) found that Coda#Pause and Coda#Vowel contexts showed marked styleshifting towards the standard realisation in more formal speech registers while Coda#Consonant contexts showed much less styleshifting.Footnote 9 These production results were mirrored by those from perceptual tests: speakers were more likely to rate glottal replacement negatively when it occurred before a vowel or a pause compared to pre-consonantal instances (Fabricius Reference Fabricius2002: 132).

Figure 9. Glottal replacement by individual speaker and interviewer

In order to examine the intersection of addressee and linguistic environment in these data, we cross-tabulated these factors across the three generations. These results are shown in figure 10.

Figure 10. Glottal replacement by age, linguistic context and interviewer

Figure 10 shows that onset contexts in the middle-aged and older speakers have higher rates with the outsider, but we note that these contexts have small Ns,Footnote 10 which precludes any strong conclusion based on this result. Aside from this, all contexts are in fact equal. These findings suggest that addressee does not interact with linguistic context. However, the question remains as to why some speakers show higher rates when they talk to the outsider. Recall Trudgill's findings that glottal replacement was correlated with addressee rates, and he hypothesised that this arose from accommodation (see section 2.2). To test for this possibility here, we examined the rates of glottal replacement in the two interviewers: the community insider and outsider. Figure 11 shows that the overall rates of glottal replacement are indeed higher in the speech of the outsider than the insider, thus there may be an effect of addressee in these data where speakers accommodate to the higher glottal replacement user. We return to why this might be the case in section 5.

Figure 11. Overall rates of glottal replacement by interviewer

In sum, for linguistic and social constraints on use of [ʔ] for /t/, the data demonstrate that:

1. There is rapid change in apparent time – from 38 to 90 per cent in the space of three generations.

2. Linguistic conditioning interacts with age, with differing ordering of constraints across the generations.

3. Gender effects were present in the older and middle-aged cohorts but these differences levelled within the young cohort.

4. There was some evidence of accommodation to interlocutor, particularly in the older cohort but not in any particular linguistic context.

Having examined each of the possible conditioning factors on glottal replacement – age, linguistic context, gender and interlocutor – we now model these using the mixed effects multivariate analysis program RBrul (Johnson Reference Johnson2009). Section 4.6 below details our procedure and our results.

4.6 Multivariate analysis

Our descriptive results present a number of observations that are relevant in the construction of our models. First, the aggregate results in apparent time demonstrated a rapid change across the generations, in other words a vigorous change in progress. Second, the descriptive statistics suggested that each of the linguistic and social factors interacted with age. For instance, the linguistic conditioning showed differences in the ordering of contexts between the generations, and for the social factors there appeared to be a levelling of constraints over time. To test the interaction between age and the linguistic and social factors more rigorously, we conducted our multivariate analysis using a series of models. First, we modelled all three generations together. In order to formally test the interaction of age and the other constraints, age was entered as an interaction term with each of the other factors: linguistic context, gender and interviewer. The model revealed that age interacts significantly with linguistic context (p < .001), which demonstrates that the hierarchies are significantly different across the generations.Footnote 11 Gender and interviewer were also shown to significantly constrain the variability as main effects and males showed significantly higher rates of glottal replacement than females; speakers used significantly higher rates of glottal replacement when talking to the outsider. To investigate the details of these interactions more closely, we then modelled the data separately for each age cohort.

Table 4. Mixed-effects logistic regression model of glottal replacement by age cohort

The results from these three models are shown in table 4, and these confirm the patterns visible in the by-factor analysis. First, linguistic context is highly significant for every age cohort. Moreover, the constraint hierarchy for each age cohort is different, as indicated through the more-to-less ordering of the log likelihoods for each category:

However, while there are differences in the detail, for each generation a two-way split is visible in the data: the Ambi#Syl, Coda#Vowel and Ambi#Vowel contexts show higher rates of glottal replacement, while Coda#Pause and Onset contexts have lower rates.

For the social constraints, the models also support the patterns visible in the descriptive results – a general levelling of the constraints. Males significantly favour the change in the older and middle-aged cohorts (p < .01 and p < .001), but gender does not significantly constrain the variation in the young cohort. The effect of interviewer is only significant for the older cohort, where speakers show significantly higher rates of glottal replacement when talking to the community outsider. Neither middle-aged nor young speakers showed any effect of interlocutor in these two contexts of use.

5 Discussion

In the Introduction we suggested that a rapid rise in an iconic British variable in one community could provide a window on key processes in the trajectory of [t] to [ʔ]. To uncover these processes, we conducted a series of analyses across social and linguistic constraints in order to shed light on where glottal replacement came from and where it was going.

A key issue is when and where glottal replacement is first attested, and when and where it subsequently spread. As indicated in section 1, the historical record suggests that glottal replacement has a long history in Scotland (e.g. Wright Reference Wright1905; Andrésen Reference Andrésen1968). Our results across apparent time showed that the rapid increase in glottal replacement is a relatively recent phenomenon in Buckie: compare 38 per cent overall in the oldest cohort to 90 per cent in the youngest cohort. However, the fact that the oldest generation used the form 38 per cent of the time overall suggests that this variant has been in Buckie for a number of generations. This time depth is given further support from the analysis by individual speakers: all speakers in the older cohort use glottal replacement. Further, two older males – Joel and Donald, both born in the 1940s – use the form over 70 per cent of the time.Footnote 12 As glottal replacement is said to have existed in the Glasgow area for at least 150 years (Andrésen Reference Andrésen1968: 18), the apparent-time analysis from this most peripheral of dialects suggests that it has been widespread for a significant time elsewhere in Scotland also.

In addition to time-stamping the spread of this form, key to the question of the origins of glottal replacement is where in the linguistic system it appears in different varieties. In our analysis we provided a detailed breakdown of the different linguistic contexts of use. Although there were differences in detail in hierarchies of use across the three generations, perhaps due to the ongoing change in this variety, a two-way split was evident in all three generations: Ambi#Syllabic-consonant (bottle), Coda#Vowel (that is), Ambi#Vowel (better) showed greater use of [ʔ] than both Coda#Pause (right) and onset (sometimes) environments. This linguistic conditioning looks quite different from other more southern dialects, where a PreC > PreP > PreV> V_V hierarchy predominates. Even in Glasgow, another Scots variety, Ambi#Syllabic contexts show the lowest rates (Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 194–5). Why might this be the case? As with many other linguistic variables, the historical record may provide further evidence for the initiation and spread of [ʔ]. Wright (Reference Wright1905: 29) states that in west-mid Scotland, Lothian and Edinburgh, ‘intervocalic t (tt) with 1 or r in the next syllable has become the glottal catch’. The linguistic environment that Wright singles out for glottal replacement may simply be the one that was most salient to his ear, but it is interesting that it includes a context that has the highest rates of use in the older and middle-aged speakers in these data (e.g. bottle). This suggests that this environment was the original entry point for glottal replacement in this dialect, with subsequent spread to other environments as the variant increased in use.Footnote 13 Thus glottal replacement in Buckie may not be the result of the spread of supralocal norms in the ‘diffusionist model’ (Straw & Patrick Reference Straw and Patrick2007: 390), but rather a more local root which subsequently spreads to other environments of use. The hierarchies shown in figure 6 may then be interpreted as traces of the past continuing into the present day, with these traces subsequently being lost in the younger generations as the variant exhibits higher and higher rates of use.

Word-internal onsets are equally interesting in terms of the trajectory of change and comparison with other dialects. This is one of the few contexts which resists glottal replacement in many varieties studied (Docherty et al. Reference Docherty, Foulkes, Milroy, Milroy and Walshaw1997: 290).Footnote 14 Even in Glasgow, Stuart-Smith (Reference Stuart-Smith1999: 194) reports ‘obligatory’ use of [ʔ] in prepausal, and frequent use in prevocalic and intervocalic contexts in working-class speech, but to the best of our knowledge, [ʔ] is not attested in word-internal onset positions. However, glottal replacement is permitted in this context within a number of traditional dialects such as Fife in eastern Scotland, where it is described as ‘quite normal’Footnote 15 (Leslie Reference Leslie1983, cited in Harris & Kaye Reference Harris and Kaye1990: 270). Once Buckie is included in this mix, this geographical mapping may further complicate the issue of origins and subsequent development of [ʔ]. If Andrésen's (Reference Andrésen1968: 18) statement is right, that glottal replacement first appeared in the west of Scotland and spread to the east of Scotland and the far north of England some years later, then why do Fife and Buckie use the variant in onset positions when Glasgow does not? The constraint hierarchies across the generations suggest that onsets are one of the last contexts to ‘succumb’ to glottal replacement as it has the lowest rates of use across all three generations. Note too that in the younger speakers this context lags behind compared to the increases in other environments. This suggests that onset contexts are most likely a later development in the spread of [ʔ] in these varieties, but how they arise remains unclear.

Whatever its origins, the phonetic details of word-internal onset positions may play a part in its lower rates of use. Tollfree (Reference Tollfree1999: 183) suggests that in general more prominent syllables tend to block glottal replacement. However, certain exceptions to this exist, namely the teen numerals (e.g. nineteen) and the lexical item sometimes. In Buckie we find a range of permissible onset environments for glottal replacement as in (10a–d):

- (10)

(a) And I mind some[ʔ]imes three ice creams vans in the street. (Lana, middle-aged female)

(b) That was at seven[ʔ]een year old. (Donald, older male)

(c) Black and white car[ʔ]oonii. (Sandy, middle-aged male)

(d) . . .in that rou[ʔ]ine. (Donald, older male)

While Buckie may permit a broader range of environments compared to most other dialects, it would appear that the specific patterning can still be linked to the relative prominence of the syllable in question. Gimson (Reference Gimson1965: 219) outlines a range of factors which may contribute to a sound's prominence and highlights that ‘certain English phonemes are particularly associated with unaccented situations’. Specifically, he observes that while the vowels /ə, ɪ, ʊ/ ‘may receive full accentual prominence, [they] have a high frequency of occurrence in unaccented syllables. The other English vowels may also occur in syllables which do not receive the primary accent but they may be associated in the speaker's and listener's minds with some degree of secondary accent.’ The relationship between prominence and quality may help to explain the patterning of this environment in Buckie. For instance, glottal replacement was not permitted following an unaccented syllable containing a typically unaccented vowel e.g. the /ɪ/ in guitar, but is permitted following an unaccented syllable containing a typically accented vowel e.g. the /u/ or /ɑ/ in routine or cartoon, etc. This is presumably because the second syllable in words like routine and cartoon is relatively less prominent than that of guitar. So while Buckie may be different from the majority of other dialects studied to date, the prominence hierarchy is still present. However, the exact threshold may be slightly higher than most dialects, as summarised below.

Majority of dialects:

Gui[ʔ]ar* > rou[ʔ]ine* > car[ʔ]oon* > some[ʔ]imes > nine[ʔ]een

Buckie:

Gui[ʔ]ar* > rou[ʔ]ine > car[ʔ]oon > some[ʔ]imes > nine[ʔ]een

Whether the trajectory of change in other dialects involves a spread of [ʔ] to include these environments is a question for future research, but for now we note Docherty et al.’s (Reference Docherty, Foulkes, Milroy, Milroy and Walshaw1997: 290) observation that particular contexts should not be ruled out as permitting glottal replacement even if they only do so very infrequently.

The Coda#Pause environment also provides an interesting comparison with other varieties. In the majority of studies, coda pause contexts favour glottal replacement in comparison to word medial contexts (see section 2.1). However, in Buckie, this context disfavours [ʔ] across all age groups. How can this be explained? In their study of Newcastle, Docherty & Foulkes (Reference Docherty and Foulkes1999: 62) find that glottal variants ‘are almost categorically prohibited in pre-pausal position’. Following Local, Kelly & Wells (Reference Local, Kelly and Wells1986: 416), they explain the rarity of glottal replacement in this environment as ‘best understood in relation to conversational structure or utterance structure’ where a non-glottalised released [t] signals the end of a conversational turn in Tyneside English (Docherty et al. Reference Docherty, Foulkes, Milroy, Milroy and Walshaw1997: 294). In other words, variant choice may be governed by pragmatic factors. To test whether the current data also show this constraint we divided the data into turn-internal pause versus turn-final pause contexts of use to see whether the latter had lower rates of [ʔ] in line with the data in Tyneside. Figure 12 shows the results.

Figure 12. Glottal replacement by age and pause type

Figure 12 suggests that there is no difference between pause and turn final contexts for any age group and further chi-square tests revealed there was no significant association between the type of pause and rates of glottal replacement across all age cohorts (older: p = .81; middle-aged: p = .59; young: p = .64). In this dialect, the constraint is simply pause, no matter what type. This may be one of the ‘regional particularities’ (Schleef Reference Schleef2013: 203) which differentiates the Buckie dialect from most others studied, where a pause is signalled by the now marked form in the dialect – a fully released [t].Footnote 16

While there are clear linguistic constraints on the use of [ʔ], our analysis revealed a number of social influences at work in the rise of this variant. The first important finding is that all individuals participate in the change (see figure 4). Moreover, there is evidence of ‘early adopters’ of the innovative form – Joel and Donald – who are differentiated at the earlier stages of change by their extremely high rates of [ʔ].Footnote 17 However, in the course of the rapid rise of this form there is a noted attenuation of within-group differences across the generations: in the older speakers, the difference between the lowest and highest users is 66 per cent, in the middle-aged 44 per cent but only 24 per cent for the youngest cohort. As the form increases in use, the differences between individuals decrease as the change progresses towards the end point of the s-shaped curve. At the same time, the wider social categories also undergo a levelling of differences, namely gender and addressee, as detailed below.

With respect to gender, previous research demonstrates that in working-class speech, males lead the change in the rise of the non-standard variant (see section 2.2). This is perhaps not surprising: the historical record suggests that for many decades this has been a highly stigmatised form, thus one to be avoided by females. However, previous research also suggests that as the change progresses, gender differences neutralise. This is exactly what we see in the current data, where the mixed-effects models in table 3 show a statistically significant effect for gender in the older and middle-aged cohort, but none for the younger age group.

A neutralisation of the insider/outsider constraint is also found over time: older speakers show a significant difference according to addressee, but the middle-aged and younger speakers do not. In addition, participants in the older cohort have higher rates of the non-standard variant when talking to the community outsider and this is true for individuals within this group. These results may pinpoint the generation of flux in the system: as glottal replacement has not as yet laid down a solid foundation in this older generation, it is more ‘unstable’ and thus more susceptible to other influences. One possible outcome of this is accommodation (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986: 39) as demonstrated by our results where certain speakers adjust their use to accommodate to the outsider's higher rates. We further hypothesise that as the rates of [ʔ] increase in the community, no such accommodation is warranted as speakers use [ʔ] as much or even more than the outsider. This is signalled by the largely flat lines across addressee, for example, most of the younger cohort. What this means more generally is that processes of accommodation to speakers and/or varieties may be implicated in the rise of glottal replacement in the manner described more generally by Trudgill (Reference Trudgill1986: 42): ‘the geographical diffusion of linguistic forms takes place, for the most part, when face-to-face interaction between speakers from different areas happens sufficiently frequently for accommodation to become permanent, and on a sufficiently large scale for considerable numbers of speakers to be involved.’

6 Conclusion

Traditionally, glottal replacement has been one of the most stigmatised variants in the British Isles. Despite this, its rise is unrivalled in terms of speed and scope of its spread. This in-depth analysis of one dialect aimed to shed light on the trajectory of change from new and vigorous to completed, and brings us full circle back to the original question of origins and development of glottal replacement more generally. Our analysis has shown that glottal replacement has been around in this peripheral dialect for at least three generations, and has spread rapidly in that time. The linguistic patterning that we have uncovered indicates that it is very unlikely that the source of [ʔ] is London or indeed Glasgow. It looks more akin to the patterns found in northeastern varieties such as Tyneside and Fife, although this is not to rule out the influence of other varieties in the spread of this form. In the end, our current understanding of the complexities of where glottal replacement arose, and how it subsequently spread, is perhaps best summed up by Trudgill (Reference Trudgill2008: 9) thus: ‘a relatively recent phenomenon, perhaps no more than 150 years old, with its origins in lower sociolects in London and/or Glasgow and/or East Anglia’. Analyses of other dialect areas may contribute further to our understanding of the ‘and/or’ in the trajectory of this iconic variable through time and space.

Appendix

Table A1. Fully articulated coding system for linguistic context