1 Introduction

The subject of negation in English has attracted the attention of scholars from a number of different disciplines, ranging from linguistics to philosophy (Labov Reference Labov1972; Horn Reference Horn and Cole1978, Reference Horn1989; Tottie Reference Tottie1983, Reference Tottie and Kastovsky1991a, Reference Tottie1991b, Reference Tottie and Kastovsky1994; Palacios Martínez Reference Martínez and Ignacio1995, Reference Martínez and Ignacio2003, Reference Martínez and Ignacio2010a, Reference Martínez and Ignacio2010b; Biber et al. Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999; Fischer Reference Fischer, van Ostade, Tottie and van der Wurff1999; Smith Reference Smith2001; Moscati Reference Moscati2010; Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2010, among others). Rohdenburg's (Reference Rohdenburg1995, Reference Rohdenburg, Dalton-Puffer, Ritt, Schendl and Kastovsky2006, Reference Rohdenburg, Höglund, Rickman, Rudanko and Havu2015, Reference Rohdenburg, Kaunisto, Höglund and Rickman2018) work on complexity examines its role in subordinate clauses. His research looks at the different structural features that appear to add complexity to a construction, such as negation, passive voice and the presence of intervening material, illustrating how their inclusion in a sentence can influence the speaker's choice between competing patterns by triggering the use of the most explicit ones (Complexity Principle; Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg1995, Reference Rohdenburg, Dalton-Puffer, Ritt, Schendl and Kastovsky2006). He also argues that not-negation and some types of no-negation (e.g. never) have a similar influence on this choice (Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg, Höglund, Rickman, Rudanko and Havu2015: 103). Taking the example of the verb vow, he finds that both not-negation and the negative marker never ‘increase substantially the proportions of the finite option’, but with different strengths, since not-negation has a stronger effect than never (Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg, Höglund, Rickman, Rudanko and Havu2015: 104).

Studies on negation in English focus mainly on British and American English, thus excluding the many non-native L2 varieties of World Englishes (WEs). These varieties have been shown to exhibit a preference for finite patterns as part of their tendency to use more transparent and isomorphic structures (Schneider Reference Schneider, Nevalainen and Traugott2012; Steger & Schneider Reference Steger, Schneider, Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi2012; Romasanta Reference Romasanta2017). In a recent study on the verb regret (Romasanta Reference Romasanta, Parviainen, Kaunisto and Pahta2019a), L2 varieties of English (in particular Hong Kong English and Nigerian English) were found to favor finite that/zero-complement clauses over nonfinite (S) -ing clauses, with different intra-linguistic factors showing a significant effect on the alternation, such as subject coreferentiality, animacy of the subject in the complement clause, temporal relation and length of the complement clause (see examples (1) and (2), respectively).Footnote 2 In the same study, an analysis of the possible semantic and syntactic reasons for this preference showed that the presence of a negative marker in the complement clause was a predictor for the use of finite patterns. Therefore, the aim of the current study is to explore further the effect of negation and the presence of negative markers on complement alternation.

(1) He regretted that the President does not understand the magnanimity of the national situation. (GloWbE-TZ)

(2) although we regret her not coming to Asia-Pacific,… (GloWbE-LK)

Specifically, this article will consider the influence of negation on the choice between the two possible, semantically synonymous complement clauses for the verb regret, finite that- and zero-complement clauses and nonfinite (S) -ing participle clauses.Footnote 3 The data include tokens from L1 and L2 varieties and are taken from the Corpus of Global Web-Based English (GloWbE, Davies Reference Davies2013). The reason for analyzing and comparing data from both L1 and L2 varieties is the well-documented sensitivity of L2s to cognitive complexity, as varieties formed in situations of language contact and as a result of second-language acquisition processes (Thomason Reference Thomason2008; Schneider Reference Schneider, Nevalainen and Traugott2012, Reference Schneider, Schreier and Hundt2013, Reference Schneider2018; Steger & Schneider Reference Steger, Schneider, Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi2012).

Based on Rohdenburg's (Reference Rohdenburg, Dalton-Puffer, Ritt, Schendl and Kastovsky2006, Reference Rohdenburg, Höglund, Rickman, Rudanko and Havu2015) findings on the relationship between negation and complexity, the hypotheses to be tested in the present study are as follows:

i. The presence of a negative particle (either not-negation or no-negation) in the complement clause favors the use of more explicit options. In the case of the verb regret, the more explicit options are: (a) finite complement clauses over nonfinite ones, i.e. the use of that/zero-complement clauses over (S) -ing clauses, see examples (1) and (2) above; and (b) the use of the complementizer that over zero within finite clauses, as in (3) and (4) below;

(3) I regret that I was never able to meet Michael Latham. (GloWbE-MY)

(4) We regret no personal correspondence can be entered into. (GloWbE-ZA)

ii. This tendency will be stronger in L2 varieties of English, owing to their sensitivity to cognitive complexity;

iii. Not-negation and no-negation will have different effect strengths, with not-negation producing a stronger effect on the preference for more explicit options, as in (5) and (6).

(5) I regret that I didn't do this earlier … (GloWbE-US)

(6) He told he was regretting having done nothing for others … (GloWbE-IN)

The article is divided into five sections. This introduction is followed in section 2 by a brief account of other research on the verb regret and the subject of negation, and in section 3 by a description of the methodology used. The results presented in section 4 begin with an overview of the distribution of the different complementation patterns, before examining the effect of negation as a general constraint (section 4.1) and the effect of not- and no-negation (section 4.2). Section 5 provides a summary of the main conclusions of the study.

2 regret, negation and the Complexity Principle

2.1 The verb regret

Cuyckens, D'hoedt & Szmrecsanyi's (Reference Cuyckens, D'hoedt, Szmrecsanyi and Hundt2014) study of complement distribution in relation to regret, remember and forget in Late Modern English shows that regret may be followed by finite or nonfinite complement clauses. Their analysis examines changes in complement choice over time and the possible predictors responsible, including the type of subject of the main clause, the type of subject of the complement clause, the voice of the complement clause and the verbal meaning of the complement clause. The possible influence of negation on complement pattern choice is not considered, however.

Romasanta's (Reference Romasanta, Parviainen, Kaunisto and Pahta2019a) study of the complementation of the verb regret in four varieties of English (American English, British English, Hong Kong English and Nigerian English) uses a binary logistic regression model to test a series of semantic and syntactic predictors and shows that the choice between finite clauses and -ing clauses is influenced by the animacy of the subject in the complement clause, coreferentiality between the subjects of the main and complement clauses, the temporal relation between the two clauses and the presence of a negative marker. Since negation turns out to be a significant predictor in this alternation, the next section takes a closer look at the different negative markers with the aim of identifying potential differences between them as predictors of complement clause alternation across a wider range of varieties of English.

2.2 Negation

Most research on negation focuses on issues such as negative raising (as in I don't think he's coming; see, for example, Horn Reference Horn and Cole1978, Reference Horn1989; Fischer Reference Fischer, van Ostade, Tottie and van der Wurff1999; Moscati Reference Moscati2010), negative concord or multiple negation (as in I haven't got no money; Labov Reference Labov1972; Weldon Reference Weldon1994; Smith Reference Smith2001; Palacios Martínez Reference Tottie2003, Reference Martínez and Ignacio2010a), negative particle ain't (Anderwald Reference Anderwald2002; Walker Reference Walker2005; Palacios Martínez Reference Martínez and Ignacio2010b), and frequency in speech and writing (Biber Reference Biber1988; Tottie Reference Tottie1991b; Palacios Martínez Reference Martínez and Ignacio1995; Biber et al. Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999; Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2010). The evolution of the different negative markers in the history of English is also a fertile topic of research and is often viewed as an example of ‘Jespersen's Cycle’ (as coined by Dahl Reference Dahl1979).

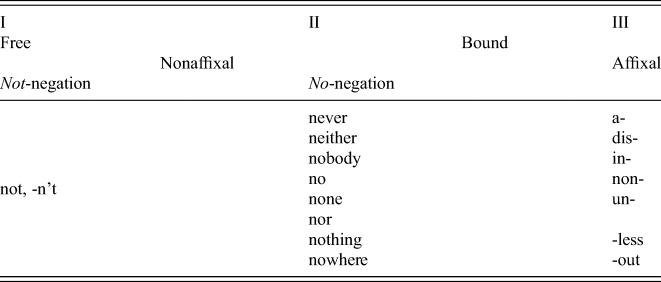

Tottie (Reference Tottie1991b: 8) offers a useful classification of these different forms of negation, reproduced in table 1. Column I shows the free nonaffixal adverb not and its reduced form -n't, while column II contains bound nonaffixal negative items which are formed with the no longer productive element n- and constitute a closed class. Column III contains bound affixal morphemes, which are productive and form an open class. This article will focus on utterances containing nonaffixal negative forms, to compare examples of not-negation using the adverb not/n't with examples of no-negation using the element n- (e.g. He does not have any money versus He has no money, and He did not do anything versus He did nothing).

Table 1. Classification of intrasentential negative expressions in English (reproduced from Tottie Reference Tottie1991b: 8)

2.3 The Complexity Principle

Tottie has carried out numerous studies on variation between not-negation and no-negation (Tottie Reference Tottie1983, Reference Tottie and Kastovsky1991a, Reference Tottie1991b, Reference Tottie and Kastovsky1994), concluding that not-negation is especially present in speech, while no-negation is favored in writing. Rohdenburg (Reference Rohdenburg, Höglund, Rickman, Rudanko and Havu2015) is, to the best of my knowledge, the only study to focus exclusively on negation as a complexity factor in different types of subordinate clauses (e.g. finite and nonfinite clauses, marked and unmarked infinitives, marked infinitives and pseudo-coordinated structures involving the verb stem try, modal verb + infinitive versus subjunctive, marked infinitives and gerunds, and prepositional gerunds and directly linked gerunds). According to his findings, ‘some forms of no-negation exhibit a similar influence on the choice of clausal variants to that of not-negation’ (Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg, Höglund, Rickman, Rudanko and Havu2015: 103). One example of this is the use of finite and nonfinite clauses with vow, in which the presence of negation favors the use of finite complements, regardless of the type of negative marker (though not-negation seems to have a stronger effect than never).

As already mentioned, the presence of a negative particle within a subordinate or complement clause makes it a ‘cognitively more complex environment’ (Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg1995, Reference Rohdenburg, Dalton-Puffer, Ritt, Schendl and Kastovsky2006, Reference Rohdenburg, Kaunisto, Höglund and Rickman2018). Rohdenburg's Complexity Principle states that:

in the case of more or less explicit constructional options, the more explicit one(s) will tend to be preferred in cognitively more complex environments (Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg1995, Reference Rohdenburg, Dalton-Puffer, Ritt, Schendl and Kastovsky2006: 147)

In the English clausal complementation system, a negative marker (which adds complexity to the structure) favors finite complement clauses when there is a choice between a finite and a nonfinite clause expressing the same meaning, as in example (7) (see Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg1995, Reference Rohdenburg, Dalton-Puffer, Ritt, Schendl and Kastovsky2006). On the other hand, within finite complement clauses, negative markers favor clauses with an explicit complementizer (example (8)):Footnote 4

-

(7)

(a) They regretted not having come oftener to the school. (GloWbE-US)

(b) They regretted that they did not come oftener to the school.

-

(8)

(a) I confess I regret that we had not been able to obtain their previous consent; (GloWbE-GB)

(b) I confess I regret ∅ we had not been able to obtain their previous consent;

The Complexity Principle, which partly explains the preference for more explicit patterns, fits with the general tendency in World Englishes (WEs) towards transparency, also referred to as isomorphism or iconicity (Thomason Reference Thomason2008; Schneider Reference Schneider, Nevalainen and Traugott2012, Reference Schneider, Schreier and Hundt2013, Reference Schneider, Schreier and Hundt2018; Steger & Schneider Reference Steger, Schneider, Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi2012). Transparency is observed here in the preference for finite over nonfinite structures, since finite clauses are more explicit, in that they are marked for tense, agreement and modality (Givón Reference Givón and Haiman1985: 200; Steger & Schneider Reference Steger, Schneider, Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi2012: 165). Increased transparency in World Englishes is the result of a series of cognitive processes involved in the situations of language contact and Second Language Acquisition (SLA) in which these varieties of English emerge and develop. It is to be expected, therefore, that the factors that make environments cognitively more complex (negation, passivization, relativization, extractions, and so on) should have a stronger effect in these varieties of English.

3 Methodology

The corpus used for this study is the GloWbE corpus of Global Web-Based English by Mark Davies (Reference Davies2013), which comprises 1.9 million words from the internet obtained between 2012 and 2013.Footnote 5 The corpus includes data from both websites and blogs from 20 different countries (United States, Canada, Great Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Hong Kong, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and Jamaica).Footnote 6 This study examines the effect of negation in two L1 varieties (British English and American English) and all 14 L2 varieties sampled in GloWbE.

The verb regret was chosen because it exhibits free variation between finite that/zero forms and nonfinite (S) -ing with anterior and simultaneous meanings. The search query used to find all examples of the verb regret was regret*_v*. This search retrieved a number of false positives and invalid examples, which were discarded (for more details, see Romasanta Reference Romasanta2017). A precision and recall analysis was performed to test the accuracy of the data obtained, the results of which were very positive, with values of over 90 percent in almost all varieties, with the exception of BrE (89.2% recall; Romasanta Reference Romasanta2019b).

To offset the excessively high number of items obtained for L1 varieties (British English and American English), a random sample of 2,000 items was selected for each. For L2 varieties, all items identified were included in the analysis.

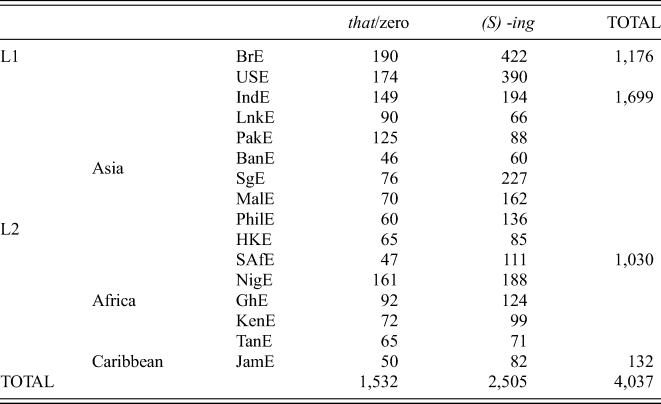

After manual pruning of the examples and their classification in terms of complementation type (that/zero and (S) -ing), temporal relation (anterior or simultaneous) and variety yielded 4,037 examples of the verb regret, with free alternation between finite clauses and -ing clauses with no difference in meaning (see table 2).

Table 2. Number of examples showing alternation between that/zero-complement clauses and (S) -ing clauses with the same meaning in GloWbE

The data were then manually coded as follows:

(a) polarity: affirmative or negative

(b) negative marker: not, -n't, never, neither, nobody, no, none, nor, nothing, nowhere

(c) negation: not-negationFootnote 7 or no-negation

4 Results and discussion

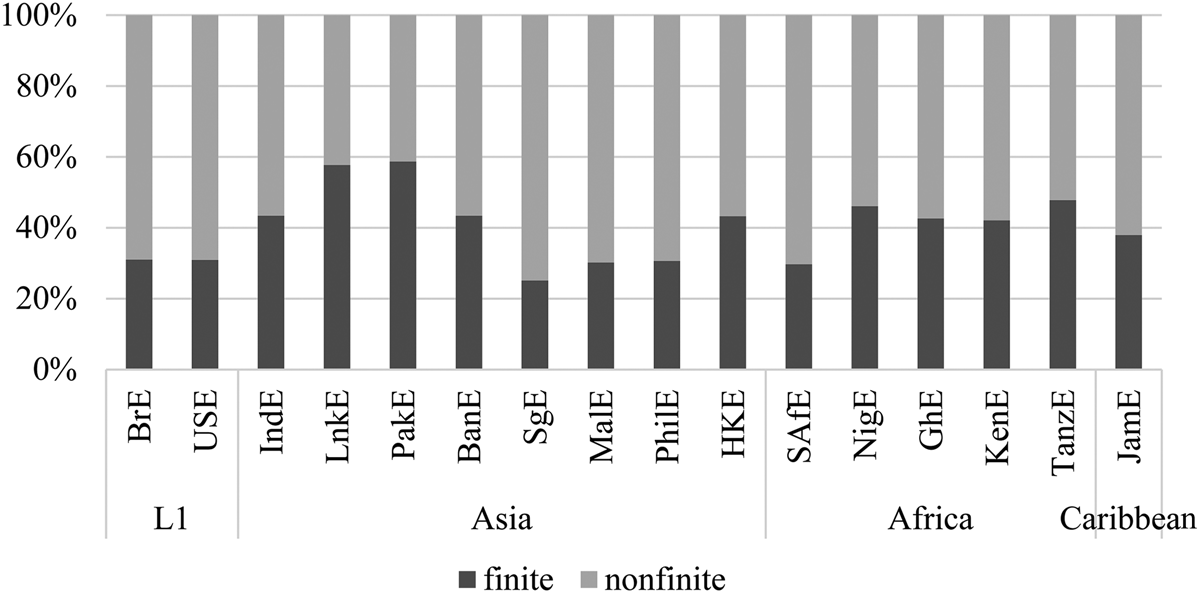

An initial analysis of the distribution of the complementation patterns that allow alternation with the verb regret (see figure 1) reveals a preference for -ing clauses in almost all varieties, the only exceptions being Sri Lanka (LnkE) and Pakistan (PakE). Singapore (SgE), Malaysia (MalE), Philippines (PhilE) and South Africa (SafE) show a similar distribution to that of the L1s (USE and BrE), with around 69 percent -ing clauses. SgE is the variety with the highest proportion of -ing clauses (74.9%), followed by SafE (70.3%), MalE (69.8%) and PhilE (69.4%). All the other varieties show a stronger preference for finite clauses, namely IndE (43.4%), BanE (43.4%), HKE (43.3%), NigE (46.1%), GhE (42.6%), KenE (42.1%), TanzE (47.8%) and JamE (37.9%), as compared to the L1s (31%). These results are largely in line with Steger & Schneider's (Reference Steger, Schneider, Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi2012) findings concerning the preference of L2 varieties for finite patterns as compared to L1 varieties. In the current study, such a preference was found to be true for 10 out of the 14 L2 varieties, the exceptions being the varieties spoken in Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines and South Africa, as already noted.

Figure 1. Distribution of complementation patterns in all varieties of English

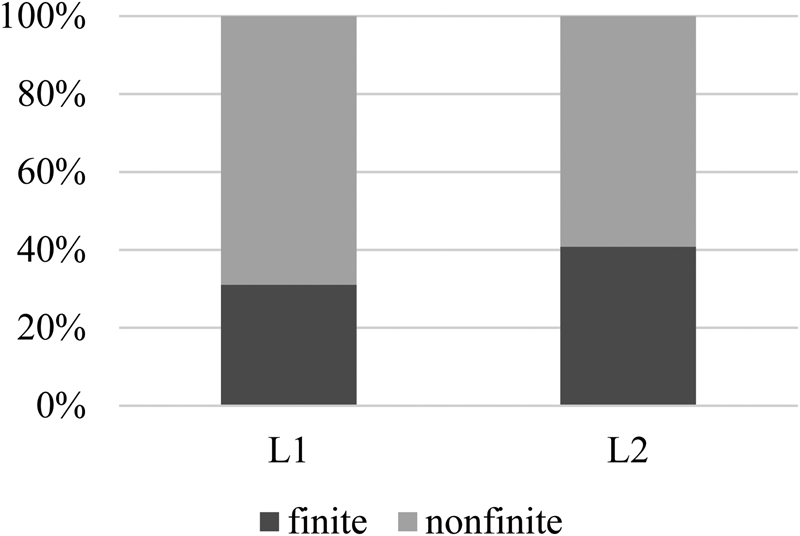

Figure 2 illustrates the difference in distribution of complementation patterns between L1 and L2 varieties, revealing a much weaker tendency to use finite clauses in L1 varieties (31%) than in L2 varieties (40.8%). The distribution of finite clauses and -ing clauses shows a significant difference between L1 and L2 varieties (p < .0001, d.f. = 1, N = 4,037).

Figure 2. Distribution of complementation patterns in L1 and L2 varieties of English

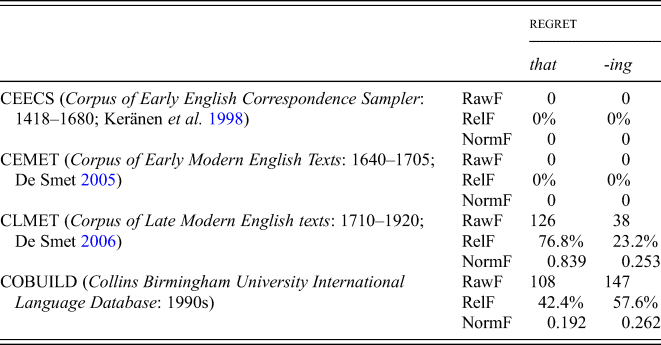

The difference in distribution between L1 and L2 varieties of English has a number of possible explanations, including the cognitive processes involved in the language contact and second language acquisition situations in which these varieties develop (Steger & Schneider Reference Steger, Schneider, Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi2012), and the influence of substrate languages (Romasanta Reference Romasanta2017). Other possible factors include the historical development of the complementation profile of the verb regret (Romasanta Reference Romasanta, Parviainen, Kaunisto and Pahta2019a), or even ‘colonial lag’ (Marckwardt Reference Marckwardt1958), also known by the more neutral term ‘extraterritorial conservatism’ (suggested by Hundt Reference Hundt, Rohdenburg and Schlüter2009). Distribution patterns in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British English, the period in which the British colonies were established, show a clear preference for that-complement clauses, and this remains the case in present-day L2 varieties of English (see table 3).

Table 3. Evolution of the complementation profile of the verb regret in the history of English (adapted from Heyvaert & Cuyckens Reference Heyvaert, Cuyckens, Winters, Tissari and Allan2010: 141)

The historical development of the verb regret does not account for the internal variation found between different L2s, however. The explanation may lie in the evolutionary perspective offered by Schneider's (Reference Schneider2003, Reference Schneider2007) Dynamic Model of postcolonial Englishes. This evolution offers three possible interpretations: (i) the more advanced the variety is, the more endonormative and distinct it will be from the input variety (i.e. British English or American English); (ii) the less advanced the variety is, the more exonormative and similar it will be to the original variety; and (iii) the more advanced the variety is, the weaker its tendency towards transparency and isomorphism will be, which may in turn make it more similar to the input variety. Malaysian English, for example, which is said to be in an early stage of evolution (Phase 2 of Schneider's Dynamic Model: exonormative stabilization), has a similar distribution to that of the input L1s; that is, a very strong tendency for -ing clauses (interpretation (ii)). At the other end of the evolutionary scale, the distribution of finite and nonfinite patterns in South African English (phase 4: endonormative stabilization) is also similar to that of the L1 varieties (interpretation (iii)). Surprisingly, none of the more advanced varieties studied here matches interpretation (i). The only two varieties that could be considered a partial match are Nigerian English and Ghanaian English, which are said to be between phases 3 (nativization) and 4 (endonormative stabilization). These are the only two varieties that are relatively advanced and yet distinct from the L1, in that they show a weaker tendency to use -ing clauses (53.9% and 57.4% respectively) compared to native varieties of English (approximately 69%).

Language variation and language change in World Englishes (as in other languages) are subject to a complex interplay of internal and external factors, the impact of which is varied and unpredictable across the different varieties. In the remainder of this article, I will focus on the effect of one of these factors, negation, on complement choice.

4.1 Affirmative versus negative complement clauses

This section focuses on the effect of negation as a predictor of complement choice based on the higher cognitive complexity of negative clauses. Section 4.1.1 examines the effect of negation on the choice between -ing and finite clauses, while section 4.1.2 deals with its role in the choice between finite that- and zero-complement clauses.

4.1.1 Alternation between nonfinite (S) -ing and finite that/zero-complement clauses

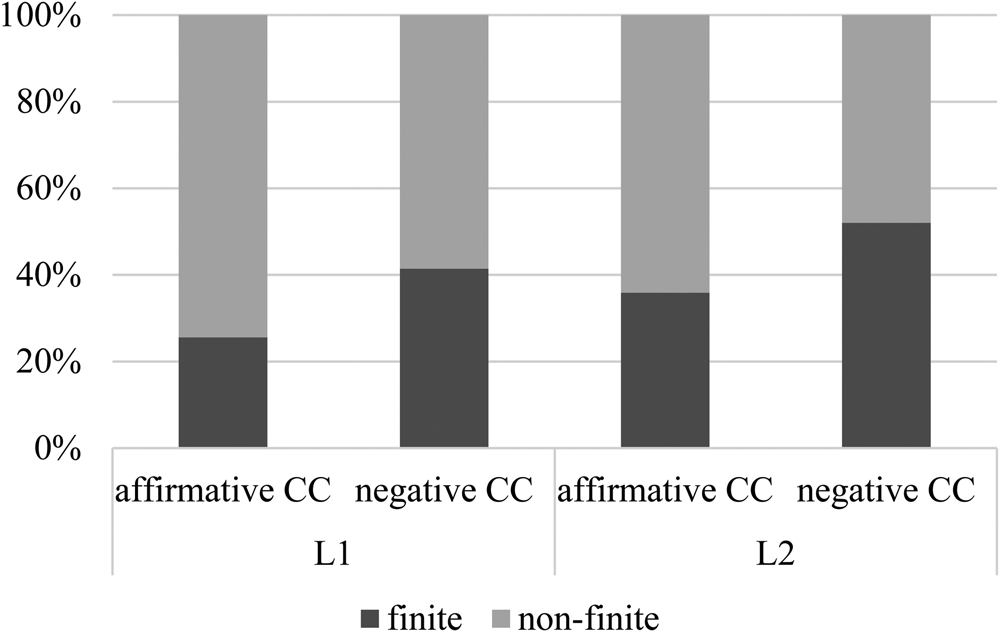

Figure 3 shows the distribution of -ing and finite clauses in L1 and L2 varieties of English. The two columns on the left represent the use of complementation in L1 varieties and the two columns on the right represent the use of complementation in L2 varieties.

Figure 3. Distribution of -ing clauses versus finite complement clauses in affirmative and negative clauses in L1 and L2 varieties of English

The results indicate a slightly stronger tendency to use finite clauses when the complement clause is negative, in both L1 and L2 varieties. By contrast, when the complement clause is affirmative, the use of finite patterns is relatively less frequent. The analysis also shows an average difference of 10 percent between L1 and L2 (L1 69%, L2 59%). In relation to negative complement clauses, the proportion of finite clauses is 59% in L1s and 48% in L2s.

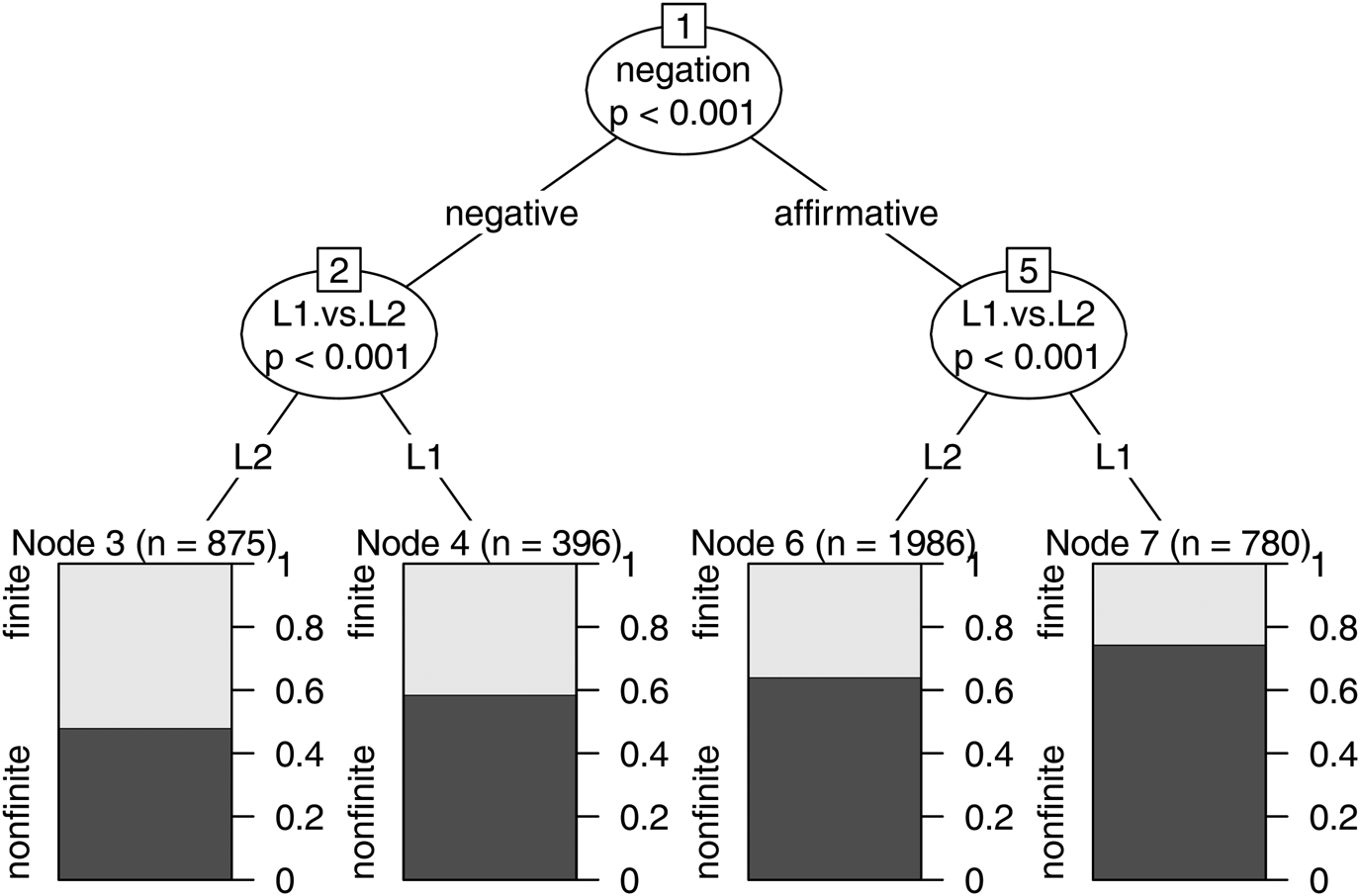

Conditional inference trees were used to examine the effect of variety group and negation as predictors of complement choice.Footnote 8 The theory and mechanics of this explanatory technique are summarized in Bernaisch, Gries & Mukherjee (Reference Bernaisch, Gries and Mukherjee2014: 14) as follows:

Conditional inference trees are a recursive partitioning approach towards classification and regression that attempts to classify/compute predicted outcomes/values on the basis of multiple binary splits of the data. Less technically, a data set is recursively inspected to determine according to which (categorical or numeric) independent variable the data should be split up into two groups to classify/predict best the known outcomes of the dependent variable … This process of splitting the data up is repeated until no further split that would still sufficiently increase the predictive accuracy can be made, and the final result is a flowchart-like decision tree.

A conditional inference tree was fitted using the function ctree() in the party package for each analysis (Hothorn, Hornik & Zeileis Reference Hothorn, Hornik and Zeileis2006). Of the two predictors tested (variety group and negation), negation was found to have a stronger effect on the alternation (see figure 4). When the complement clause is negative, the left of the tree shows a slightly stronger tendency to select finite clauses. The influence of variety group is also significant, with L2 varieties displaying a stronger tendency to select finite clauses than L1s (node 3, approx. 50% vs. node 4, approx. 40%). These findings support the first hypothesis and part of the second: the presence of a negative marker in the complement clause favors the choice of finite complement clauses, and this tendency is stronger in L2 varieties.

Figure 4. Conditional inference tree of -ing clauses versus finite complement clauses in affirmative and negative clauses in L1 and L2 varieties of English

The right-hand side of the tree, which shows the data for affirmative complement clauses, once again reveals a stronger preference for finite complement clauses among L2 varieties (L2 40%, L1 30%; see example (9) below) and a significant difference between the two variety groups. This may indicate the influence of other syntactic and semantic factors (probably specific to L2) on the variation.

(9) We are pleased with the progress made in these two areas, but regret that it was not possible to adopt the two remaining texts on Preventive Diplomacy and Peacemaking; (GloWbE-JM)

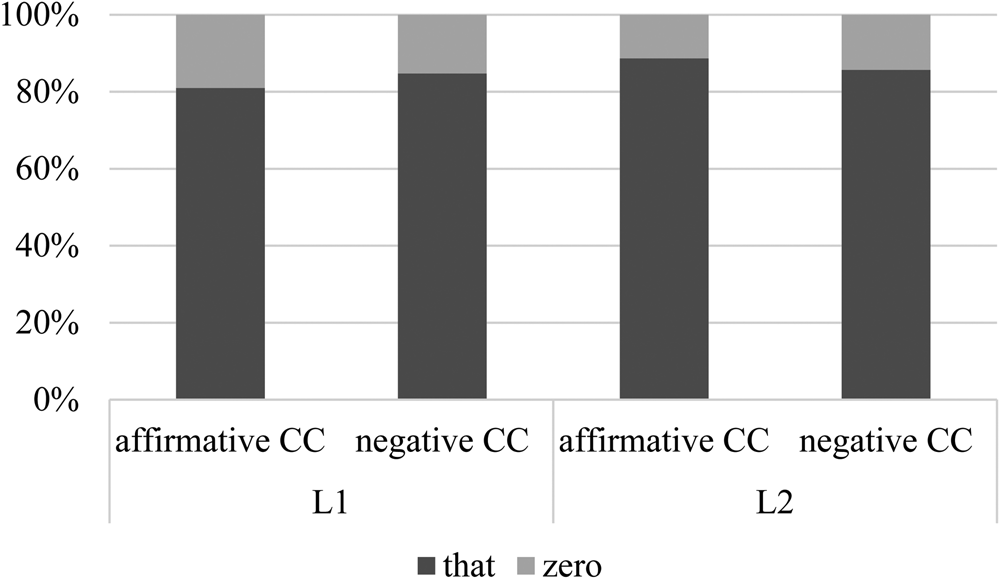

4.1.2 Alternation between finite complement clauses with and without complementizer

The data for the alternation between that- and zero-complement clauses (see figure 5) shows that that-complement clauses are predominant in all environments and across both groups of varieties of English. In L1 varieties, there is a slightly higher tendency towards that-clauses when there is a negative marker in the complement clause, while in L2 varieties the preference is for zero-complement clauses.

Figure 5. Distribution of finite complement clauses in affirmative and negative clauses in L1 and L2 varieties of English

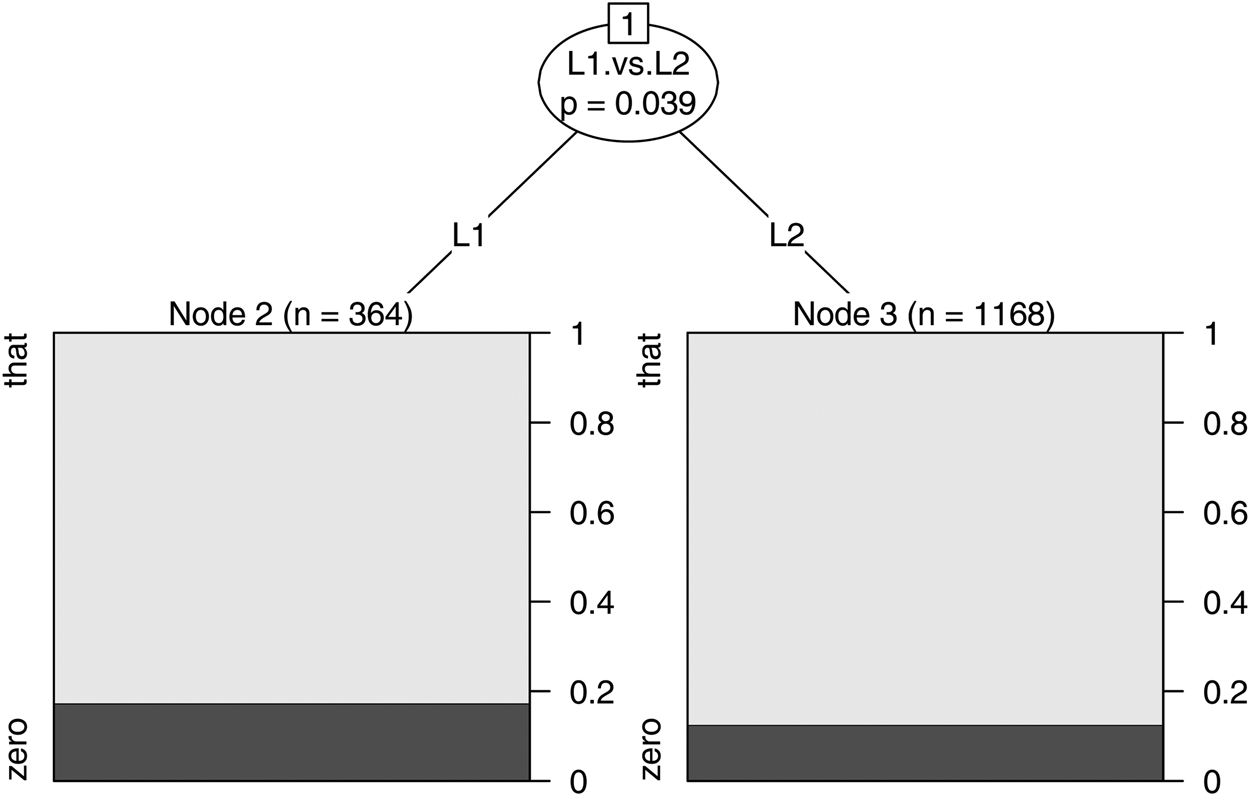

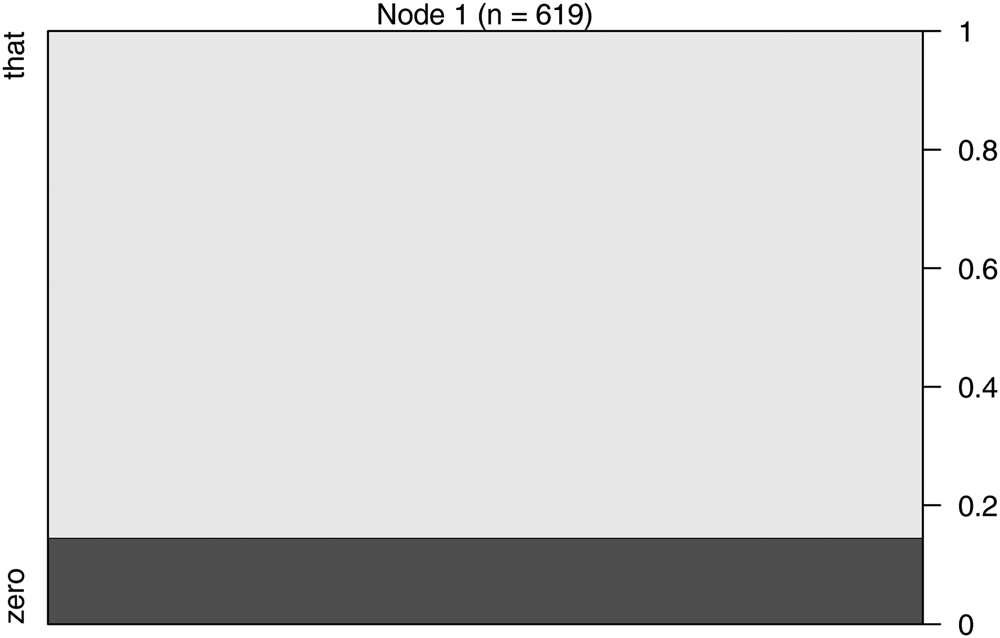

The conditional inference tree for the alternation between that- and zero-complement clauses with negation (see figure 6) confirms that the effect of negation is not significant. In this variation, only the differences between native and non-native varieties of English are significant. L2 varieties of English (the right half of the tree; node 3) show a stronger preference for the use of the complementizer that but negation is not an explanatory factor for this difference.

Figure 6. Conditional inference tree of finite complement clauses in affirmative and negative clauses in L1 and L2 varieties of English

The analysis reported in this section confirms that the presence of a negative marker in the complement clause increases the probability of finite clauses. This is in keeping with Rohdenburg's Complexity Principle (Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg1995, Reference Rohdenburg, Dalton-Puffer, Ritt, Schendl and Kastovsky2006) that more explicit options tend to be preferred in cognitively complex environments. The analysis also shows that the effect of negation in this alternation is stronger in L2 varieties. However, in the alternation between that- and zero-complement clauses, negation was not found to be a significant factor. The first and second hypotheses of the study are thus only partially confirmed. While negation increases the tendency to use that/zero-clauses and more strongly in the L2 varieties, negation does not play a role in the alternation between that- and zero-complements.Footnote 9

4.2 Not-negation versus no-negation

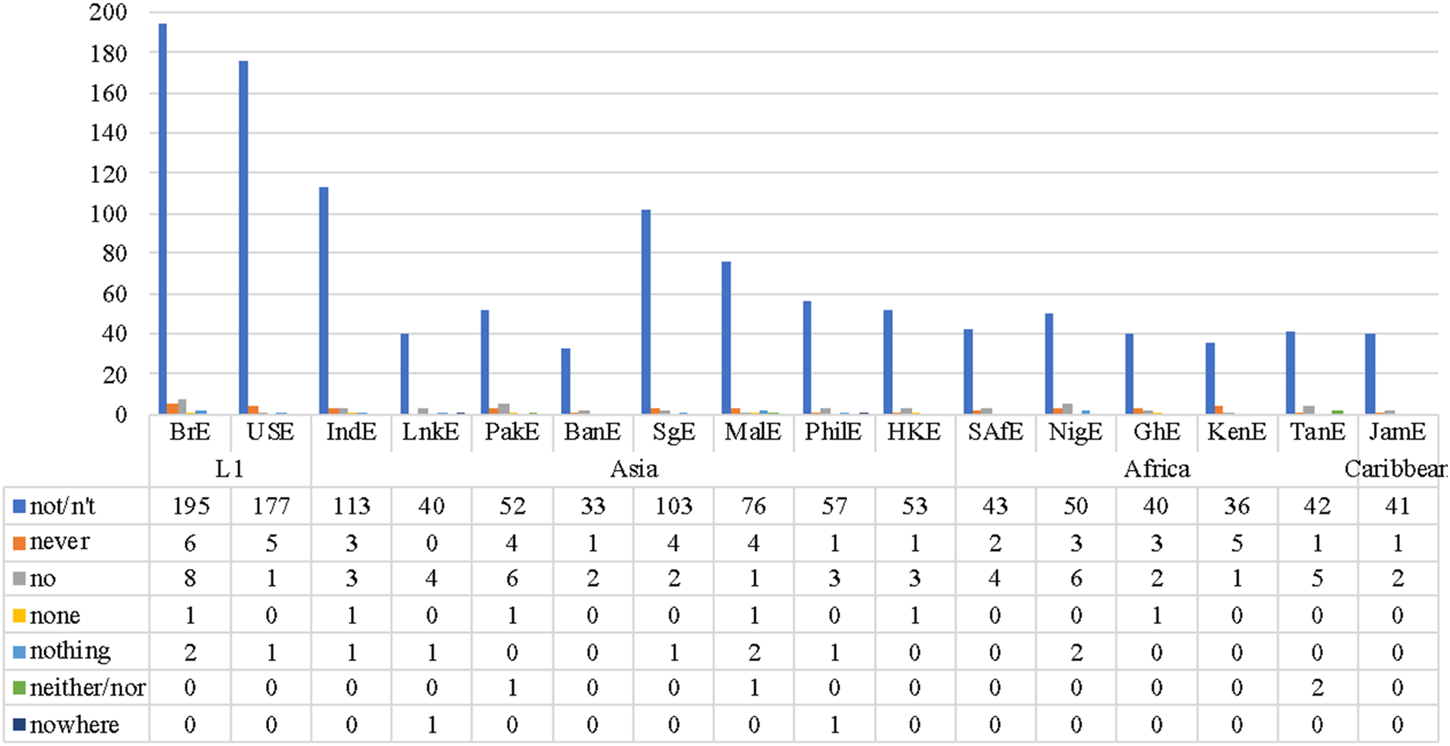

This section focuses on the effects of not- and no-negation on complement choice. Figures 7 and 8 offer an initial overview of the use of not-negation and no-negation in the complement clause with the verb regret. Figure 7 shows the raw data for all the negative markers found: not/-n't (see examples in (10) below), never (11), nothing (12), no (13), nowhere (14), none (15) and neither/nor (16).

-

(10)

(a) Vic regrets not going to Italy. (GloWbE-TZ)

(b) I only regret that you didn't do this ten years ago. (GloWbE-SG)

-

(11) I only regretted never hearing what you really thought of me. (GloWbE-PK)

-

(12) Mrs Bandaranaike may well regret that she did nothing overtly in terms of her husband's role in government. (GloWbE-LK)

-

(13) He regretted that the upper class saw no reason why people should complain about the idea but the masses … (GloWbE-NG)

-

(14) I greatly regret that I can nowhere put my hand upon the authorized report of the Mission … (GloWbE-LK)

-

(15) Earl of Suffolk regretted that none of the former ministry who were present, had chosen to speak in the debate. (GloWbE-HK)

-

(16) DAP regrets that Hon Choon Khim has neither defended the Chinese primary school board of director nor his own MCA leader from being attacked … (GloWbE-MY)

Figure 7. Negative markers in different varieties of English

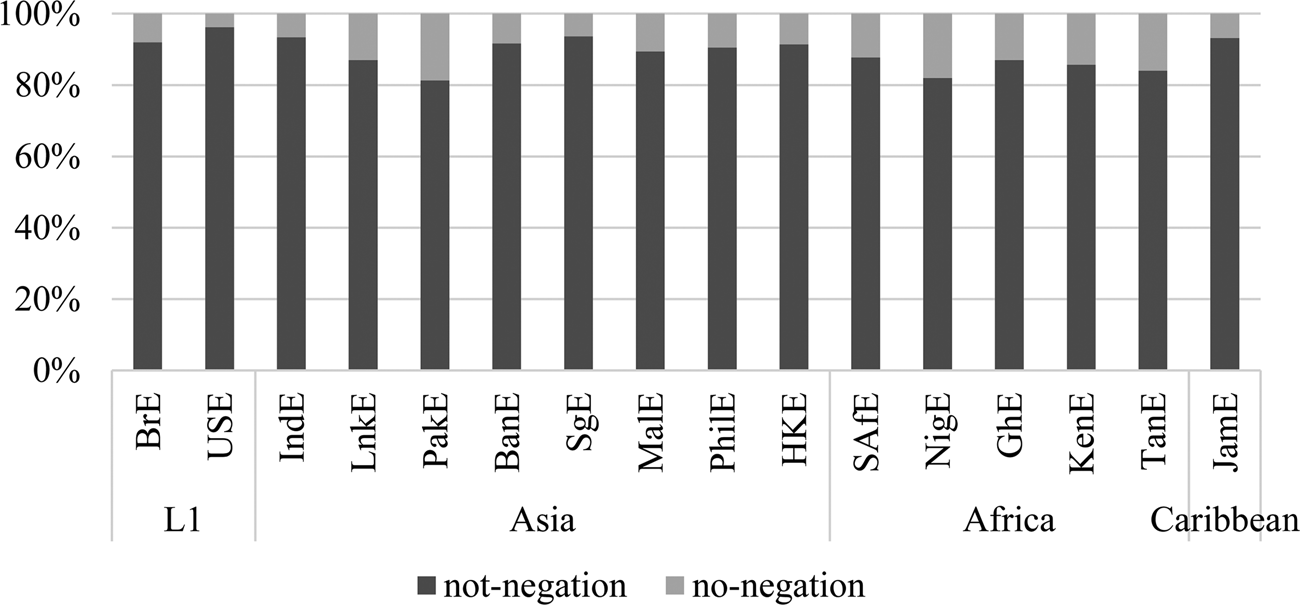

Figure 8. Variation between not-negation and no-negation in different varieties of English

The preference for not and its reduced form -n't across all varieties is conspicuous, while the use of the other forms of negation varies. The two most frequent negative markers after not/-n't are never and no, which occur at least once in all of the varieties analyzed, in contrast to none, nothing, neither/nor and nowhere, which are rarely used (see figure 7).

Figure 8 groups the data from figure 7 into two categories, not-negation and no-negation, together with their relative frequencies. The frequency of not-negation is more than 80 percent in all varieties, and is highest in the L1 varieties (USE 96.2%, BrE 92%). No-negation occurs most frequently in Pakistani English and Nigerian English, with 18.8% and 18% respectively.

The next part of the analysis examines the extent to which not- and no-negation affect the alternation between -ing and finite clauses (section 4.2.1), and the alternation between finite complement clauses with and without the complementizer that (section 4.2.2).

4.2.1 Alternation between nonfinite (S) -ing and finite that/zero-complement clauses

Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of -ing clauses versus finite clauses with not-negation and no-negation. Both types of negation exhibit a higher-than-average proportion of finite clauses in all varieties and the effect of no-negation is stronger than not-negation. Looking at the effects of each type of negation in more detail, we find that the preference for finite complement clauses with no-negation is conspicuous in both groups of varieties (83.3% in L1 varieties and 84.2% in L2 varieties) and stronger in L1 varieties.

Figure 9. Distribution of -ing clauses versus finite complement clauses with not-negation and no-negation in L1 and L2 varieties of English

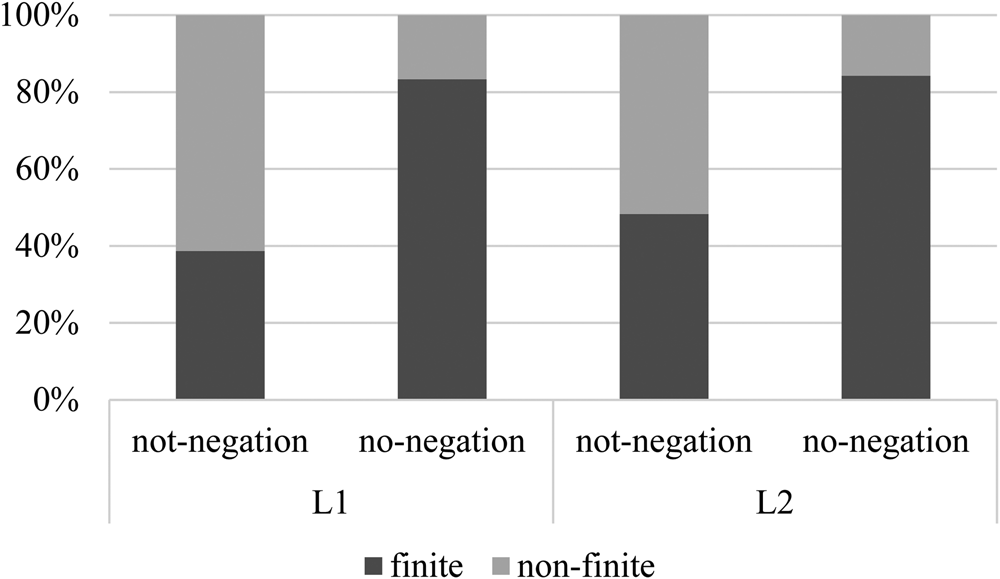

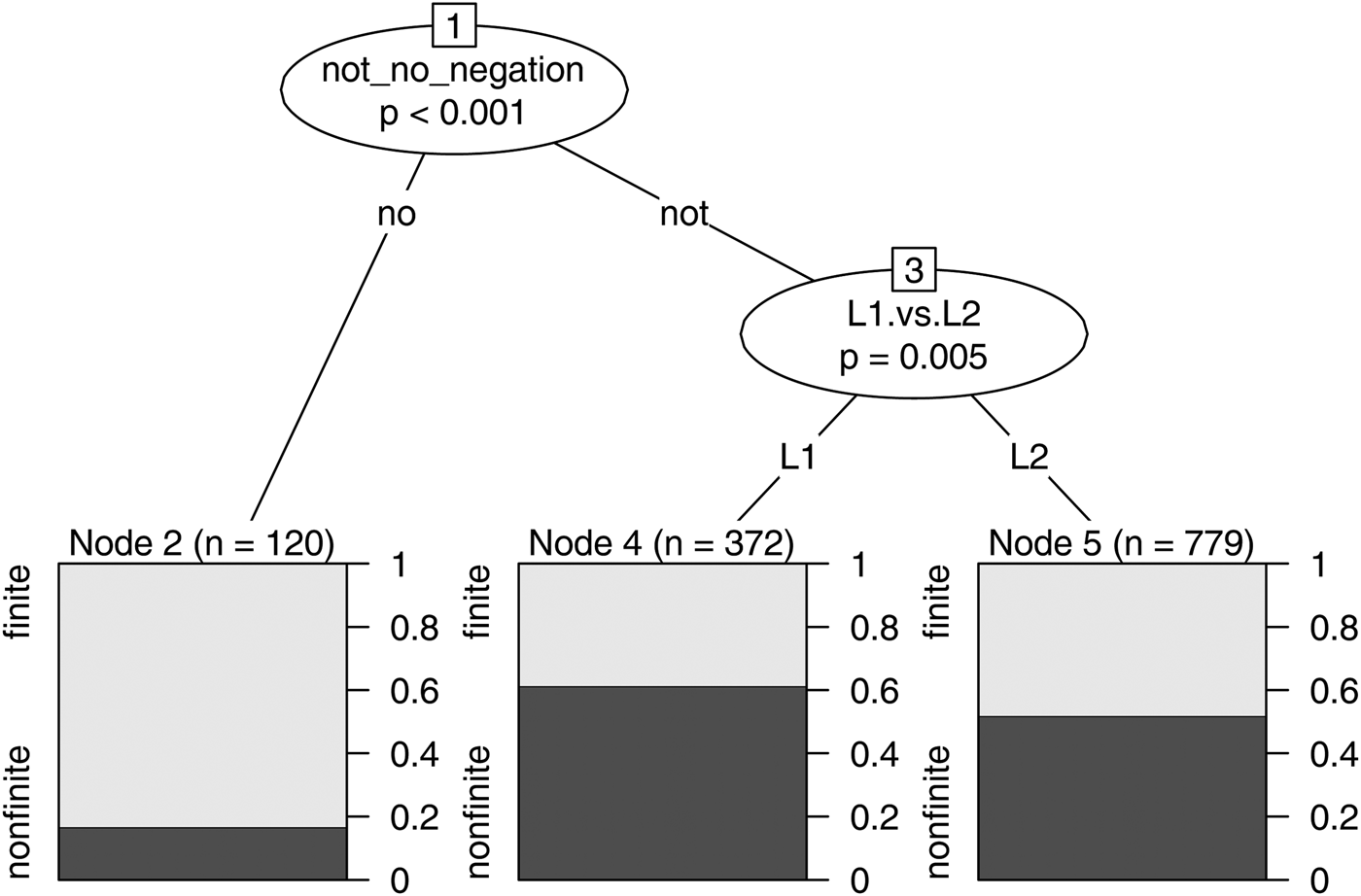

Figure 10 is the conditional inference tree for the alternation between -ing clauses and finite complement clauses, where the major predictor is negation. On the left-hand side of the figure, node 2 shows a clear preference for finite complement clauses in 80 percent of occurrences of no-negation, and no significant difference between native and non-native varieties of English. On the other hand, node 3, on the right-hand side of the figure, shows a significant difference between L1 and L2 varieties in relation to not-negation, with the use of finite clauses in L2s significantly higher (10 percent) than in L1s. The results show that no-negation has a stronger effect on the choice of finite complement clauses than not-negation. This may be accounted for in terms of frequency, since highly frequent items or constructions are less cognitively complex and therefore require less processing capacity (Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg, Rohdenburg and Mondorf2003: 220; Reference Rohdenburg2016: 475).

Figure 10. Conditional inference tree of -ing clauses versus finite complement clauses with not-negation and no-negation in L1 and L2 varieties of English

As observed in section 4.2 regarding the distribution of the two types of negation (see figures 7 and 8 above), not-negation is noticeably more frequent than no-negation. The high frequency of not-negation may lower its cognitive complexity, which would decrease the need for finite complement clauses, i.e. the more explicit option. By contrast, no-negation is expected to be cognitively more complex owing to its lower frequency, which makes it necessary to use the more explicit option (i.e. finite complement clauses). However, Rohdenburg (Reference Rohdenburg, Höglund, Rickman, Rudanko and Havu2015) reports on research by Hagemeier (Reference Hagemeier2006) on directive verbs where it is found that no-negation (presumably less frequent than not-negation) is also less likely than not-negation to select the more explicit should + to-infinive construction over the less explicit subjunctive. In other words, at this stage in our knowledge, we cannot draw any firm conclusions concerning the relationship between not-negation and all or individual types of no-negation.Footnote 10

4.2.2 Alternation between finite complement clauses with and without complementizer

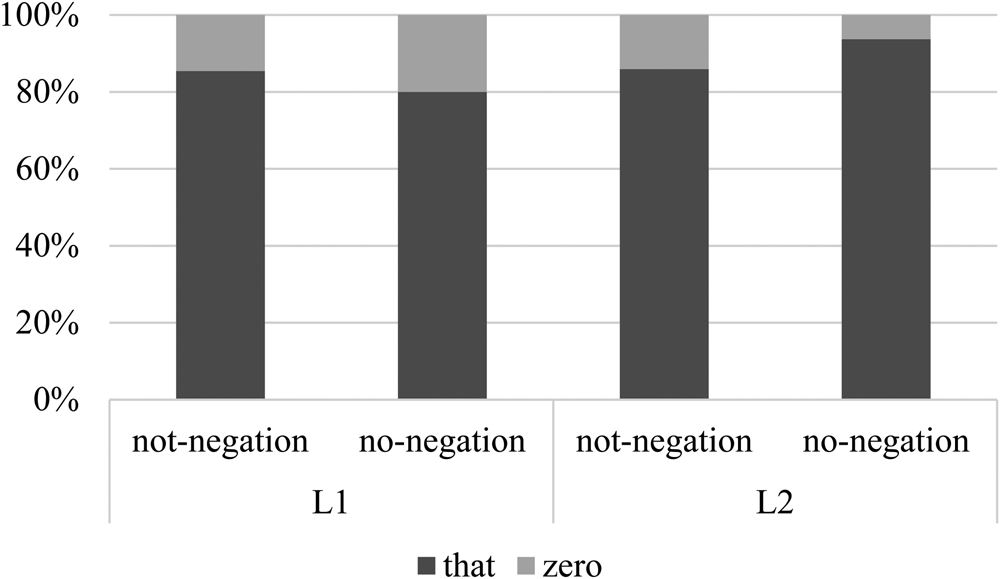

In the alternation between finite complement clauses, the preference is always for the use of the complementizer that, for both types of negation and in both variety groups (see figure 11). On closer analysis, minor differences are revealed between varieties and types of negation. Starting with the L1 varieties, the left-hand side of the figure shows a slightly stronger preference in not-negation for the use of the complementizer that, while with no-negation the tendency is towards zero-complement clauses. In L2 varieties, the reverse is true: no-negation favors that-clauses, while not-negation favors zero-complement clauses.

Figure 11. Distribution of finite complement clauses with not-negation and no-negation in L1 and L2 varieties of English

Figure 12 is the conditional inference tree for this alternation between that- and zero-complement clauses. The result is a bar plot containing the frequencies of that- and zero-complement clauses in which neither of the factors has a significant effect on choice.

Figure 12. Conditional inference tree of finite complement clauses with not-negation and no-negation in L1 and L2 varieties of English

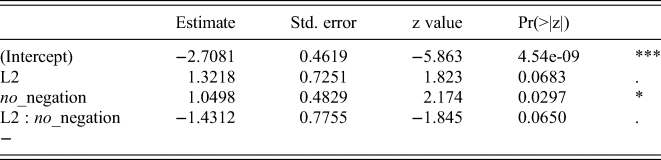

As Gries (Reference Gries2020: 623) has warned, these tree-based models may ‘fail to identify the correct predictors-response relation(s) in the data’; in other words, interactions between factors are not predicted accurately by the inference tree. To offset this risk of misprediction, the data set was checked for interactions using a binary logistic regression model using the glm() function in the rms package (see table 4). The response variable is binary, distinguishing between that- and zero-complement clauses, and predicted estimates are for that-complement clauses. The interaction between the two factors, negation and variety group (L2:no_negation), has a minimal effect on the choice, with p < .1. However, the results also show that when the interaction is included in the model, the factor type of negation (no_negation in the table) has a significant effect, with no-negation increasing the preference for the use of the complementizer that, with p < .05. Once again, this may be explained in terms of frequency. The high frequency of not-negation mentioned in section 4.2 (see figures 7 and 8) lowers its cognitive complexity, which in turn decreases the need for the more explicit complementizer that. On the other hand, the low frequency of no-negation might make this construction cognitively more complex, thus triggering the need for the more explicit option.

Table 4. Binary logistic regression model of finite complement clauses with not-negation and no-negation in L1 and L2 varieties of English

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘.’ 1

To sum up this section, the preferred type of negation across all varieties is not-negation (figures 7 and 8). For no-negation, the use of the different markers varies, with never and no proving most popular. Regarding the choice between finite complement clauses and -ing clauses, both types of negation show a greater tendency to use finite clauses, and no-negation does so more strongly than not-negation. This finding contradicts the third hypothesis of the study, which predicted that not-negation would have a stronger effect than no-negation. Moreover, while the differences between L1 and L2 varieties in relation to no-negation are not statistically significant, with not-negation, L2 varieties of English show a stronger tendency towards finite complement clauses. Regarding the factors affecting alternation between that- and zero-complement clauses, only negation was found to be significant, with no-negation showing a stronger tendency in favor of the complementizer that, again in contradiction of the third hypothesis.

5 Conclusion

This article has focused on the effect of negation on the complementation system of the verb regret in different L1 varieties of English (British and American English) and L2 varieties (India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Hong Kong, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and Jamaica) as represented in GloWbE. Complement clause variability with this verb is between finite that/zero-complement clauses and nonfinite (S) -ing clauses, and internal preferences in finite complement clauses in favor of and against the complementizer that.

The first hypothesis, which predicted that the presence of a negative particle (not-negation or no-negation) in the complement clause would favor, firstly, the use of finite complement clauses over nonfinite complement clauses, and secondly, the use of that over zero in finite complement clauses, has been partially confirmed. The analysis in section 4.1.1 shows that the presence of a negative marker in the complement clause triggers the use of a finite complement clause over -ing clauses. This is in accordance with Rohdenburg's Complexity Principle (Reference Rohdenburg1995, Reference Rohdenburg, Dalton-Puffer, Ritt, Schendl and Kastovsky2006), in that when negation is present in the complement clause, it adds complexity to the sentence and consequently increases the tendency towards the more explicit option. However, section 4.1.2 shows that the presence of a negative marker does not have a significant effect on the alternation between the use of that- and zero-complement clauses, though the use of the complementizer provides greater isomorphism in situations of cognitive complexity.

The second hypothesis, which posited that the preference for more explicit patterns would be stronger in L2s as a result of their tendency to use more transparent and isomorphic structures (Thomason Reference Thomason2008; Schneider Reference Schneider, Nevalainen and Traugott2012, Reference Schneider, Schreier and Hundt2013, Reference Schneider, Schreier and Hundt2018; Steger & Schneider Reference Steger, Schneider, Kortmann and Szmrecsanyi2012), was also partially confirmed, insofar as L2 varieties of English show a stronger preference for finite over -ing complement clauses owing to the presence of a negative particle in the complement clause (section 4.1.1). However, as regards alternation between finite patterns with and without a complementizer (section 4.1.2), the presence of a negative particle in the complement clause was not found to be a determining factor in the stronger preference for the complementizer that in L2 varieties, indicating that variation may be due to alternative semantic or syntactic factors.

The third and final hypothesis, that not-negation would have a stronger effect than no-negation, was not confirmed. Both types of negation were found to favor finite patterns (see section 4.2.1), with no-negation exhibiting a stronger tendency in this regard than not-negation. In terms of alternation between that- and zero-complement clauses, no-negation was also shown to be more likely to trigger the use of the complementizer that (section 4.2.2). This may be attributable to the frequency of use of each type of negation, since highly frequent constructions are cognitively less complex, while less frequent constructions are cognitively more complex (Rohdenburg Reference Rohdenburg, Rohdenburg and Mondorf2003: 220, Reference Rohdenburg2016: 475). In the case of the verb regret, no-negation is less frequent, which makes it a more complex construction requiring the use of more explicit options. Within the alternation between finite and -ing clauses, finite complement clauses represent the more explicit option, while within the alternation between that- and zero-complement clauses, that-complement clauses are more explicit than their zero-complement counterpart. However, as already noted, research on directive verbs shows the contrary tendency, with not-negation selecting the more explicit construction, which makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the relationship between not-negation and all or individual types of no-negation.

To conclude, the findings of this study confirm the role of negation as a predictor of complement clause choice after the verb regret, as has been demonstrated elsewhere for other complexity factors, such as passivization and extractions. The study also shows differences between the behavior of L1 and L2 varieties arising from L2 use of linguistic resources to increase isomorphism, transparency and explicitness in situations of complexity. Continued research into the effect of complexity factors on complementation will certainly find L2s a rich testing ground and source of data for new theories and methodologies in this area.