1 Introduction

This article provides an examination of the degree to which authors of Early and Late Modern English medical texts epistemologically position themselves in relation to the key concepts they discuss in their writings. That is, to what extent do the authors of these texts link knowledge, their own and others’ sources of knowledge and their confidence in their assertions, to the matters which they discuss? Consider the following:

(1) Therefore, in a subject, where there is no heart, or even liver, that vein ought to communicate immediately with the aorta inferior. In this manner one conceives how this subject could do without a heart, the umbilical blood being a continuation of that from the arteries of the placenta, the uterus, and in short of the mother . . . (LMEMT, 1767_SC-PER-PT-Vol57_0001-0020: Claude Nicholas Le Cat, ‘A monstrous human Foetus . . .’, PT, vol. 57, p. 12)Footnote 2

In this passage, Le Cat is discussing the survival of a foetus that is missing a heart (among other vital organs and body parts), and through known facts about how normal embryos function, he infers how it's possible that this foetus would survive because the umbilical blood is a ‘continuation of that from the arteries . . .’, and he expresses his deduction through the phrase one conceives how. In other words, he signals that his stance towards his claims about the foetus’ survival is one of inference.

Since the status of knowledge itself came into play during changes in medicine from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, one can expect the linguistic manifestations of knowledge in medical writing to reflect the constant and shifting values given to knowledge and its sources during this period. The focus here will be on texts related to midwifery and human reproduction more generally, and the genres under examination are the scientific report (predecessor of the modern journal article) and the medical treatise (precursor to the textbook). Both these genres involve the transmission of knowledge, although the former generally involves communicating new knowledge to one's colleagues or fellow specialists, whereas the latter serves a more didactic function of knowledge instruction to those considered less knowledgeable by the author. These genres allow us to take a multifaceted, in-depth look at a specific field of medicine during a time when substantial changes were underway in the discipline, thus allowing us to see how writers’ linguistic and textual practices diverge from previous times as well as point the way forwards towards the present day. The findings can then be linked into the developments underway in medical writing more broadly, hence highlighting both discipline-specific and more general tendencies regarding the textual-linguistic realisation of epistemic stance. A bottom-up, corpus-driven (function-to-form) approach is taken to data collection and analysis, provided by the relevant subsections of the Early Modern English Medical Texts (EMEMT) and Late Modern English Medical Texts (LMEMT) corpora. This ensures that few presuppositions about both key themes in the texts, as well as the linguistic forms that signal epistemic stance (the author's relation to the status of the knowledge they communicate, i.e. (un)certainty, source of knowledge, etc.), are made about the period and genres under investigation. In addition, the use of lockwords – words that corpora have in common – and a focus on what stance expressions are used in the context of prominent lexical items, rather than a focus on the stance expressions themselves, have implications for the study of epistemic stance well beyond (historical) medical discourse, as it displays a novel way in which to locate and study stance expressions in both diachronic and synchronic contexts.

The article is organised as follows: section 2 provides the relevant sociohistorical background surrounding early and late modern medicine, particularly as it relates to midwifery, human reproduction and medical writing; section 3 outlines the parameters related to the linguistic expression of epistemic stance adopted in the current study; section 4 details the methods of data collection and analysis; results are discussed in section 5; and section 6 provides some final thoughts on what the study has revealed.

2 Medicine and medical writing in early and late modern England

Early modern medicine retained many of the hallmarks of medieval medicine, namely humoral theory as the basis of explaining human health and illness and a continuing reliance – in the tradition of medieval Scholasticism – on the authority of classical, learned authors such as Galen, Hippocrates and Avicenna. But already from Late Middle English, medical writing witnessed a vernacularisation boom, seeing Latin being gradually displaced as the sole language of learning (particularly in print) in favour of texts capable of reaching a broader, (literate) monolingual English audience (Pahta & Taavitsainen Reference Pahta and Taavitsainen2010). In addition, converging phenomena such as exploration, periodic outbreaks of the plague and the Reformation led to a gradual distrust in the purported infallibility of classical models of medicine and learning. Indeed, the Royal Society was founded in 1660 (chartered 1662) to pursue and promote the newer, more empirically based mode of discovery promoted by natural philosophers such as Francis Bacon and Robert Boyle (good historical overviews are provided in Siraisi Reference Siraisi1990; Grafton, Shelford & Siraisi Reference Grafton, Shelford and Siraisi1992; Shapin Reference Shapin1996; Wear Reference Wear2000; French Reference French2003; Cook Reference Cook, Park and Daston2006; Lindemann Reference Lindemann2010; Mikkeli & Marttila Reference Mikkeli and Marttila2010).

The practice of midwifery – women assisting women in normal childbirth (i.e. childbirth with no or only minor complications, not even considered a medical phenomenon until recently) – remained fairly unchanged throughout most of the early modern period, although the sixteenth century did witness the publication of the first vernacular midwifery treatises (Green Reference Green2008; Lindemann Reference Lindemann2010: 124–8). All sixteenth-century and most seventeenth-century treatises, however, were written either by (male) learned physicians who never once set foot in the birthing chamber, or by (male) surgeons who only intervened in a medical emergency, such as when a baby died in utero (Evenden Reference Evenden2000: 1–13). It was not until the seventeenth century that (female) midwives penned their own treatises, basing their discussions not on the writings of antiquity but on their own extensive experience as practising midwives. In the late seventeenth century, some male surgeons became increasingly involved in normal childbirth, sometimes even replacing the midwife entirely during the early stages of prenatal care. This coincided with the introduction of surgical instruments such as the forceps into the toolkit of the ‘man-midwife’. These two phenomena led to an ever-increasing male presence in prenatal care and normal birthing contexts, so much so that by the end of the eighteenth century, the medicalisation of normal childbirth was in full swing (Wilson Reference Wilson1995). Consequently, the eighteenth century witnessed a substantial increase in the publication of midwifery treatises penned by men who now had extensive first-hand experience in normal childbirth (Lieske Reference Lieske2007–9), guided by empirical scientific knowledge rather than the lesser-valued empathetic, experiential knowledge of female midwives (good overviews of midwifery in early modern England are provided by Fissell Reference Fissell2004; Hanson Reference Hanson2004: 16–50; Keller Reference Keller2007; King Reference King, Borsay and Hunter2012; Allison Reference Allison2021).

Whereas the scientific/medical treatise or manual – the precursor to the modern-day textbook – has been a hallmark of printed vernacular scientific writing since its inception, and it was not unknown to medieval scientific writing either, the scientific report (precursor to the modern-day journal article) found its genesis in the Royal Society's hallmark publication, the Philosophical Transactions (hereafter PT), first published in 1665. From the start, reports appearing in PT were reflective of the Society's orientation towards Baconian natural philosophy and its emphasis on empirical observation and discovery, whereas many of the early modern medical treatises reflect the enduring afterlife of medieval scholasticism with frequent references to the learned authors of antiquity and the Middle Ages (for a discussion of the competing ‘thought-styles’ of the period, see Bates Reference Bates and Bates1995, Crombie Reference Crombie1995 or Taavitsainen Reference Taavitsainen, Gotti and Dossena2001). Several of the contributions of PT had a medical focus, often reporting on observations of the human body, sicknesses, experiments on blood transfusion, or medical remedies. Although potential contributions to the PT underwent a process of editorial oversight and possible abridgement, there was no peer review in any modern sense of the concept; if a potential contribution fell within the remit of the Royal Society's interest, it was published (Atkinson Reference Atkinson1998: 33–50; see also Andrade Reference Andrade1965; Hall Reference Hall1971; Valle Reference Valle1999; Hiltunen Reference Hiltunen2010). The first comparable publication devoted exclusively to medical matters was what is labelled here as the Edinburgh Medical Journal (hereafter EMJ), first appearing in 1733, although this actually includes a number of publications emanating from the Edinburgh Medical Faculty, a centre of medical theory during the Scottish Enlightenment (Shapin Reference Shapin1974; Emerson Reference Emerson2004; Hiltunen Reference Hiltunen2019). Finally, the inclusion of medical material in the more general periodical The Gentleman's Magazine (hereafter GM) from 1731 reflects a further step in the vernacularisation of medical writing by focusing on a non-specialist audience, albeit an elite and male one (Porter Reference Porter1985; Taavitsainen Reference Taavitsainen2019; Taavitsainen & Whitt Reference Taavitsainen, Whitt and Brownlees2023). Even if not the most prominent topic, matters related to childbirth and human reproduction were discussed in all of the above publications.

Taken together, the reports found in periodicals and the treatises represent the diverse range of voices involved in midwifery and childbirth during the early and late modern periods: learned physicians, surgeons who intervened only in emergencies, and both female and male midwives. The scientific periodicals admittedly involve only the latter group, as well as other learned gentlemen who had a general interest in human reproduction and might have some relevant observations to report. Hence these two genres provide optimal material for tracing the epistemic stance in early and late modern midwifery, allowing us to examine not only any potential changes over time, but also what – if any – differences might exist among the various groups in question, or between different generic conventions. However, this study is unfortunately limited to printed material. There is little doubt that extensive handwritten material devoted to this topic – just as historically relevant to the field of midwifery and childbirth – existed during the early and late modern periods, but there is yet no corpus devoted to such material, which no doubt is more difficult to track down and probably scattered throughout various archives. The printed material represented here, on the other hand, exists in multiple copies and enjoyed a higher degree of dissemination (see, for example, Lieske Reference Lieske2007–9).

3 Language and knowledge in medical writing

One of the ever-present issues involved in changes in midwifery practice from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, or even in medicine and medical writing more broadly, is the status of knowledge: what types of knowledge are prioritised over other types? Whose knowledge is most valued and accepted? What sources of knowledge are the most reliable? Whereas scholastic medicine, as well as later texts written in the tradition of Scholasticism, placed a heavy value on the claims made by classical authors like Aristotle, Hippocrates and Galen, as well as sacred texts such as the Bible, the newer empirical models favoured first-hand observation and reasoning (Siraisi Reference Siraisi1990; Bates Reference Bates and Bates1995; Crombie Reference Crombie1995). In midwifery, the earliest authors of midwifery manuals (learned physicians and surgeons, all male) continued in the tradition of resorting to classical authorities as favoured sources of knowledge. Female midwives, on the other hand, placed a primacy on first-hand knowledge and experience (i.e. in being a woman and often in having given birth themselves) and the empathy this can encapsulate, whereas the ‘man-midwives’ placed value in the newer scientific knowledge of empiricism and the first-hand knowledge gained from practical experience (King Reference King and Marland1993; Wilson Reference Wilson1995; Lieske Reference Lieske2007–9).

The linguistic realisation of such epistemological values falls within the broad category of stance, a speaker or writer's expression of some (inter)subjective position taken in relation to the content of the proposition (for overviews of the notion of stance, see Thompson & Hunston Reference Thompson, Hunston, Hunston and Thompson2000; Englebretson Reference Englebretson2007b; Jaffe Reference Jaffe and Jaffe2009; Keisanen & Kärkkäinen Reference Keisanen, Kärkkäinen, Schneider and Barron2014; and most recently, Kaltenböck, López-Couso & Méndez-Naya Reference Kaltenböck, López-Couso and Méndez-Naya2020). Terms for the concept vary greatly throughout the literature, but those markers concerned with the status of knowledge can broadly be considered to constitute the category of epistemic stance. This generally involves, on the one hand, markers devoted to marking a speaker's certainty (or lack thereof) over whether a proposition is true or not, commonly known as epistemic modality; in addition, epistemic stance also covers items that allow speakers to express their source of information (report, hearsay, perception, inference), a phenomenon known as evidentiality. Simple expressions of knowledge or belief without recourse to certainty or source also constitute part of epistemic stance. Early typological work in the area often conflated these notions (Anderson Reference Anderson1986; Chafe Reference Chafe1986; Chafe & Nichols Reference Chafe and Nichols1986; Willett Reference Willett1988), although more recent work makes the distinction more clearly (especially Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2004, but also Palmer Reference Palmer2001 or Boye Reference Boye2012). Bednarek (Reference Bednarek2006) finds the term ‘epistemological positioning’ a suitable umbrella term to capture a range of linguistic expressions dealing with knowledge itself, sources of knowledge, and the (un)certainty with which claims are made, whereas van Dijk (Reference van Dijk2014) views all such expressions of knowledge through the lens of critical discourse analysis, reflecting broader sociocultural beliefs and ideologies as embedded in linguistic-textual-generic practices (see also Jaffe Reference Jaffe and Jaffe2009: 7). Linguistic studies of Early and Late Modern English medical writing have tended to focus on notions of evidentiality, as the types of and values associated with knowledge underwent tremendous change during this period; of course, conceptions of evidentiality have ranged from broad (Taavitsainen Reference Taavitsainen, Gotti and Dossena2001, Reference Taavitsainen, Jucker, Schreier and Hundt2009) definitions that include things like epistemic modality (see above) to those narrow approaches that exclude it (Whitt Reference Whitt2016a, Reference Whittb). There has also been some work on expressions of knowledge itself involving verbs such as know (Hiltunen & Tyrkkö Reference Hiltunen, Tyrkkö, Renouf and Kehoe2009, Reference Hiltunen and Tyrkkö2011), as well as on stance expressions (Gray, Biber & Hiltunen Reference Gray, Biber and Hiltunen2011; Hiltunen Reference Hiltunen2012; see also Bromhead Reference Bromhead2009). The current study adopts a broad approach to epistemic stance, similar to the work of Bednarek (Reference Bednarek2006), Landert (Reference Landert, Suhr, Nevalainen and Taavitsainen2019) and Grund (Reference Grund2021), involving general expressions of knowledge (including knowledge itself and related concepts like belief and assumption), (un)certainty surrounding knowledge (epistemic modality) and source of information (evidentiality).Footnote 3

To better contextualise how things worked during the early and late modern periods, consider the following examples:

(2) But that which seem'd most remarkable to me, and indeed occasioned me to take Notice of the Case, was, That the Child was very full of the Small Pox, so full, that the Midwife said, hardly a Pins head could be put between the Blisters . . . (LMEMT, 1712–1713_SC-PER_PT_Vol28_0165-0166.txt: W. Derham, ‘The Case of a Woman big with Child . . .’, PT, vol. 28 (1713), pp. 165–6)

(3) Where he inserts a very odd History of the force of Imagination in breeding Women, which is this: That a woman at Utrecht in such a condition, being surprised with the sight of a Negro, and so exceedingly frighten'd as to become speechless for the time, had a strong fancy she should bring forth a black child . . . (EMEMT, 1672_pt7_4098-5001.txt: Anonymous, ‘Johannis Swammerdami M. D. UTERI MULIEBRIS . . .’, PT, vol. 7 (1672), p. 5000)Footnote 4

(4) It happened that in the very same year that Swammerdam announced his discovery in the spawn of the frog, that a case was published in the Ephem. rerum. nat. curios. delivered to the society by a celebrated court-physician of those times Dr. Claudius, which exactly suited as a confirmation of Swammerdam's opinion.—A miller's wife was delivered of a little girl whose belly seemed of an unusual size . . . (LMEMT, 1792_SP-MW_Blumenbach_AnEssayOnGeneration.txt: Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, An essay on generation (1792), pp. 43–4)

In (2), Derham points to the fact that both physical attention (through ocular observation) and inference inform the proposition the Child was very full of the Small Pox; the verb seem'd and phrase take Notice of denotes both physical perception and more metaphorical mental attention (cf. Sweetser Reference Sweetser1990: 32–4). Further information (i.e. knowledge) is provided to Derham through a midwife's report (the Midwife said). So here we see that a combination of first-hand observation and inference couple with a second-hand report to inform the thematic content of the passage; in this instance, all cases of epistemic stance are of an evidential nature. Example (3) provides a particularly interesting scenario, for here, multiple types of knowledge (Report > Inference > Prediction) are involved in the simple proposition of a woman bring[ing] forth a black child. On the one hand, this is a prediction (indicated by should) on the part of the woman, which itself is based on an inference (had a strong fancy) – informed by her emotional reaction (surprise and fear) to seeing a person of African descent. Yet all of this falls within the broader textual scope of Swammerdam's account of the potential ‘force of Imagination in breeding Women’, indicated both by the phrase he inserts a very odd History and the cataphoric this, which marks all subsequent propositions – including their concomitant relations to knowledge – as falling within the scope of these reportative markers (see Boye Reference Boye2012 for a discussion of epistemicity and propositional scope).Footnote 5 In this instance, the epistemic stance consists of evidential (i.e. the author's) source marking as well as other parties’ relation to knowledge sources (non-evidential); that is, the pregnant woman's mental processes and information sources are also signalled in this passage. The connection between knowledge source and proposition is even less explicit in example (4), whereby a case was published . . . by . . . Dr. Claudius serves as the information source for the following story – consisting of a number of propositions – about the woes of a miller's wife giving birth to a baby girl (both of whom eventually die). However, aside from the sequencing of sentences in the text, and arguably the presence of the em dash, there are no overt linguistic markers that the propositions that comprise this story fall within the scope of Dr Claudius’ publication; in fact, there is an intervening proposition commenting on its confirmation of Swammerdam's assertions.

These examples raise a number of issues relating to the expression of epistemic meaning, both in general as well as in the context of early and late modern medical discourse. For one, they demonstrate that there is not necessarily a straightforward connection between singular linguistic forms and epistemic meaning. Although some verbs found above like seemed or said do explicitly signal an evidential meaning (marking the speaker's or writer's information source), other verbs such as take, have, insert and publish assume such a function only in their broader collocational, syntactic or discursive context, i.e. to take Notice of or had a strong fancy. However, almost all studies focusing on some form of epistemicity in scientific discourse to date – whether diachronically oriented or not, and regardless of whether taking a top-down or bottom-up approach (Pahta & Taavitsainen Reference Pahta and Taavitsainen2010: 563) – have ultimately homed in on particular word categories like modal verbs or grammatical constructions such as complement clauses (see, for example, Hyland Reference Hyland1998; Taavitsainen Reference Taavitsainen, Gotti and Dossena2001; Hiltunen & Tyrkkö Reference Hiltunen, Tyrkkö, Renouf and Kehoe2009, Reference Hiltunen and Tyrkkö2011; Gray, Biber & Hiltunen Reference Gray, Biber and Hiltunen2011; Hiltunen Reference Hiltunen2012; Whitt Reference Whitt2019). These studies have certainly made valuable contributions to the history of scientific discourse, but the more nuanced role played by particular phrases and collocations in the expression of epistemic meaning has generally been overlooked (even though Susan Hunston has long stressed the multifaceted nature of epistemic stance and the myriad forms it can take; see, e.g., Hunston & Sinclair Reference Hunston and Sinclair2000, Hunston Reference Hunston2007, Reference Hunston2011; see also Englebretson Reference Englebretson2007b, Jaffe Reference Jaffe and Jaffe2009). Two exceptions to this trend in historical stance research are the work of Grund (Reference Grund2012, Reference Grund, Jucker, Landert, Seiler and Studer-Joho2013, Reference Grund2017, Reference Grund2021) and Landert (Reference Landert, Suhr, Nevalainen and Taavitsainen2019), both of whom adopt a function-to-form approach (Taavitsainen & Jucker Reference Taavitsainen and Jucker2010: 16–18) to their data – seeking all relevant expressions of stance they can find, whatever form they may take. Neither Grund nor Landert, however, concentrate on medical discourse. The current study takes things a step further, starting not with stance markers themselves, but rather with the prominent (lexical) concepts under discussion and then seeing what, if any, epistemic stance expressions occur in these contexts (even Hunston's work begins with stance expressions themselves).

Another issue raised by example (3) and particularly example (4) is determining the relationship between the stance markers and the proposition(s) over which they scope. Discussion of the status of the proposition is a hallmark of work focusing on evidentiality and modality (see, for example, Anderson Reference Anderson1986; Chafe Reference Chafe1986; Palmer Reference Palmer2001), perhaps most extensively in Boye's (Reference Boye2010, Reference Boye2012) studies on the connection between epistemic meaning and propositional scope. However, these discussions appear restricted to scope within the immediate linguistic environment of the propositions in question (usually at the level of the sentence). Boye's main concern, for instance, is differentiating the proposition from ‘states-of-affairs’ (or verifiable/falsifiable facts from events that are said to occur),Footnote 6 and broader questions of scope on a textual scale – evidenced in examples (3) and (4) – lie beyond the confines of his discussion. Both Grund (Reference Grund2017, Reference Grund2021: 145ff.) and Whitt (Reference Whitt2018) have noted that work such as Boye's (Reference Boye2010, Reference Boye2012) tends to be based on decontextualised examples and they provide data that reveal more discursive-level scoping between epistemic stance markers and their respective propositions. Grund, in particular, conceives of the notion of pragmatic scope to cover such cases. This study continues in such a vein by examining the epistemic contexts, or space, occupied by key concepts (as manifested in lockwords) in Early and Late Modern English medical writing, within and beyond the propositions in which they are found. But whereas Grund focuses on the epistemic markers themselves, the current study begins with lexical items and then explores what sort of epistemic stance is expressed within their vicinity. Hence the term epistemic space rather than the adoption of Grund's concept of pragmatic scope.

Finally, Bednarek (Reference Bednarek2006: 639ff.) makes further distinctions with the cases of epistemic stance she investigates, all related to information source (evidentiality). For one, she distinguishes between the source and basis of the proposition, the former being the source of knowledge (to whom or what can the knowledge be attributed?) and the latter being the basis (or evidence) for the source's knowledge (perception, hearsay, inference, etc.). Thus in hardly a Pins head could be put between the Blisters from example (2), the source of this information is the midwife, and the basis of knowledge is her first-hand observation. This leads to Bednarek's other distinction, particularly germane for reported information: attribution versus averral, the latter indicating the writer's own words and the former pointing to someone other than the writer as information source. So in this instance, the author attributes the information to someone else rather than claiming that he himself is the ultimate source of knowledge. These distinctions allow a fine-grained analysis where evidential meaning is concerned, and they will be further discussed in section 5.2.

4 Data and methodology

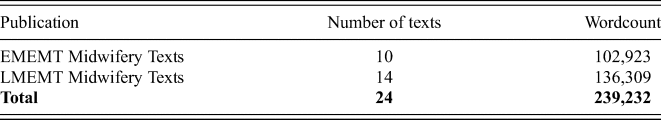

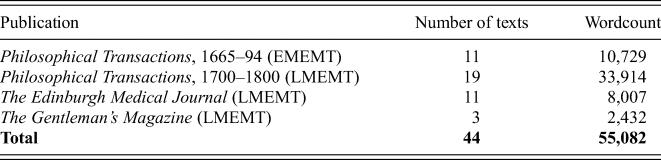

In order to create a corpus of midwifery treatises, on the one hand, and a corpus of periodicals on the other hand, data for this study were drawn from two larger corpora of medical writing: Early Modern English Medical Texts (EMEMT; Taavitsainen et al. Reference Taavitsainen, Pahta, Hiltunen, Mäkinen, Marttila, Ratia, Suhr and Tyrkkö2010), covering the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and Late Modern English Medical Texts (LMEMT; Taavitsainen et al. Reference Taavitsainen, Hiltunen, Lehto, Marttila, Pahta, Ratia, Suhr and Tyrkkö2019), covering the eighteenth century. In particular, the relevant EMEMT sections devoted to midwifery and children's diseases (Pahta & Ratia Reference Pahta and Ratia2010: 89–95), covering the treatises, and the PT (Hiltunen Reference Hiltunen2010), the only periodical in print during the seventeenth century, were explored; in addition, the LMEMT sections on midwifery (Pahta Reference Pahta2019), for treatises, and the PT/EMJ (Hiltunen Reference Hiltunen2019) and GM (Taavitsainen Reference Taavitsainen2019), for periodicals, were consulted. Both the EMEMT and LMEMT subcorpora devoted to the scientific periodicals were further searched to extract only the texts focusing on matters related to childbirth and human reproduction to create an ad hoc periodicals subcorpus. Information on the size (wordcount) and number of texts in each corpus can be found in tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Details on the Treatises corpus used in this study

Table 2. Details of the Periodicals corpus used in this study

The Treatises corpus is nearly four times the size of the Periodicals corpus, so where relevant, quantitative measures such as normalised frequencies and proportional figures will be provided.Footnote 7 For detailed bibliographic information on the texts found in the Treatises corpus, see Taavitsainen & Pahta (Reference Taavitsainen and Pahta2010: 291–343) for EMEMT texts and Taavitsainen & Hiltunen (Reference Taavitsainen and Hiltunen2019: 376–8) for LMEMT. For information on the particular texts found in the Periodicals corpus, see appendix 1.

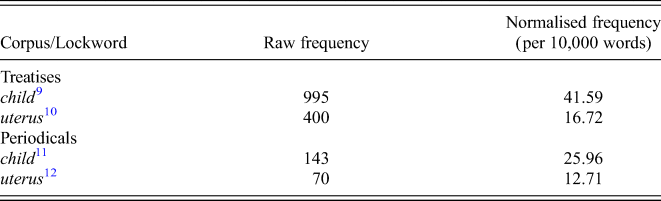

This article follows the ‘bottom-up’, specifically the function-to-form, approach to corpus studies (Taavitsainen & Jucker Reference Taavitsainen and Jucker2010: 16–18; Pahta & Taavitsainen Reference Pahta and Taavitsainen2010: 563), i.e. inductively approaching the data with as few preconceptions as possible and finding what forms are linguistically realised by a particular concept – epistemic stance in this instance. A wordlist was generated for each respective corpus using the WordSmith 8.0 concordancer (Scott Reference Scott2020). Then, in order to see what topics these two corpora had most in common, a keyword list was generated, and those lexical keywords with log ratio values closest to 0 were selected; these are known as lockwords, items that occur at relatively the same frequency in multiple corpora (see Baker Reference Baker2011 or Taylor Reference Taylor2013);Footnote 8 in this case, uterus (log ratio -0.37) and child (log ratio -0.58) were the two (lexical) items, or lexical lockwords, whose respective frequencies were most similar within both corpora. Table 3 presents the raw and normalised frequencies of the two lockwords in each of the corpora.

Table 3. Raw and normalised frequencies of the lockwords child and uterus in the corpora

Aside from child in the Treatises corpus, the dispersion rates for the EMEMT (see footnotes 9–12) show that these lockwords appear to be concentrated in only a small number of texts; the rate is noticeably higher in the LMEMT. These figures and the current focus are exclusively on the lexical item, rather than the lemma, found to be the lockword; other forms of the word (e.g. children, child's) were not examined. The function-to-form approach to epistemicity in scientific writing partly shares an affinity with the topic-driven approach adopted by philosophers of science interested in the status of knowledge (see, for example, Kuhn Reference Kuhn, Lakatos and Musgrave1970; Latour & Woolgar Reference Latour and Woolgar1979; Snyder Reference Snyder, Achinstein and Snyder1994; cf. Plappert Reference Plappert2017, Reference Plappert2019). That is, rather than being concerned with specific types of knowledge (and particular linguistic items), the current study commences with the most comparable keywords (lockwords) used – or topics discussed – in the two corpora and sees what sort of ‘epistemic space’ they occupy. That is, markers of epistemic stance are not searched for directly but are rather located in the immediate or near-immediate textual vicinity of the lockwords in question. A similar approach to speech descriptors in witness depositions from the Salem witch trials is taken by Grund (Reference Grund2017), who locates these speech descriptors in the immediate vicinity of overt markers of speech acts, while Landert (Reference Landert, Suhr, Nevalainen and Taavitsainen2019) – by initially searching for well-known stance markers – attempts to uncover lesser-known stance markers, knowing that such markers tend to cluster together in texts (as is also seen in the examples above).

Initially, a search for frequent clusters or collocates was conducted (following Plappert's (Reference Plappert2017, Reference Plappert2019) bottom-up approach to epistemic implicature), but this turned up only a number of low-frequency grammatical constructions (of the uterus, the child and), nothing comparable to the kinds of lexical clusters uncovered in Plappert's work (admittedly based on a much larger dataset). Therefore, a simple concordance was generated for each word and a close reading of the immediate linguistic context surrounding each word was conducted to search for epistemic markers; a range of roughly 500 characters within the KWIC (key word in context) line was deemed sufficient to capture a number of sentences (vis-à-vis propositions) preceding, including and following the keyword (cf. Landert Reference Landert, Suhr, Nevalainen and Taavitsainen2019). Consider the following example of child from Sarah Stone's midwifery treatise of 1737:

(5) The reason she gave me for it was, That all the Woman's Pains, instead of Bearing down, every Pain rose up the Child, and straiten'd her Belly, round her Navel, as tho’ it would have broke thro’. I laid my hand on her Belly, and it seem'd to me, that all the substance between the Child's Head and my hand, was not thicker than fine paper. The Woman told me, That after her Waters were gone, she never had one . . . (LMEMT, 1737_SP-MW_Stone_ACompletePracticeOfMidwifery.txt: Sarah Stone, A Complete Practice of Midwifery (1737), pp. 19–20)

The lockword child (underlined) is contained within the proposition every Pain rose up the child. This proposition, in turn, falls within the scope of a phrase indicating the content of the report (the reason she gave me for it was, that . . .), so here we see Stone utilising an evidential marker indicating that the proposition about pain and the movement of the child are sourced from the pregnant woman's own report. There are also other epistemic stance markers present here as well (would, seem'd, the Woman told me): the Woman told me involves a proposition that does not immediately concern the child here. On the other hand, would and seem'd do concern the very same child in question (consider, especially, the anaphoric it preceding would), albeit in neighbouring propositions. In this instance, the epistemic space surrounding child contains three stance markers: one reportative evidential (the reason . . .) with immediate propositional scope, plus one inferential (seem'd) and one contrafactual prediction (would) in neighbouring propositions with child still constituting part of the topical content of these propositions. Quantitative results, however, will be restricted to only single and double types of stance; triple epistemic marking, such as the Report > Inference > Prediction in example (3) above, is relatively infrequent and I want to avoid creating an unwieldly number of categories often resulting in five or fewer occurrences (cf. tables 6 and 7). Thus the above example (5) would be classed simply as a Report because that is the epistemic stance that is more proximal to the proposition concerning the lockword child; the other epistemic markers scope over neighbouring propositions.

Both Hunston (Reference Hunston2002) and Sinclair (Reference Sinclair2003) have noted the diminishing returns – as well as excessive mental strain – involved in analysing a large number of concordance lines (about 100 lines being sufficient for general patterns, 30 lines for detailed patterns to emerge). Since the current investigation relies on a detailed analysis of the immediate textual environment, i.e. 500 characters, of each instantiation of the lockwords, it was decided to take a representative sample of anything far in excess of 100; however, the analysis of 143 instances of child in the Periodicals was still tolerable. The Select Sample Size Calculator was used for these purposes, with a .05 margin of error, a .95 level of confidence and the likely sample proportion kept at .50.Footnote 13 So for the Treatises corpus, a sample of 197 (of 400) instances of uterus and 280 (of 995) cases of child formed the basis of analysis. Samples taken from individual texts were kept in proportion to the overall frequency of attested items in the corpus.Footnote 14 This still exceeds the recommendations of Hunston and Sinclair, but the extra time and effort (and screen breaks) simply had to be taken to ensure an analysis based on a representative amount of data.

I also distinguish between explicit (syntactic; see Boye Reference Boye2010, Reference Boye2012) and implicit (pragmatic; see Grund Reference Grund2021) scope, in an effort to examine as much epistemic space as possible, but also to account for the nuanced manner in which this space can be occupied. In the former, the relevant proposition must fall within the immediate sentential or syntactic environment of the epistemic stance marker, as is the case with the complement clauses (both with and without the that-complementiser) in examples (2) and (3). Other explicit linguistic markers that link some propositions with others, or certain parts of the text with other parts – as can be seen with the textual-cataphoric this in example (3) – also enable an explicit signalling of epistemic stance. However, when readers must rely on the conventions of text structure (like simple sentential sequencing) to infer that the stance marker scopes above and beyond its immediate syntactic or propositional context, as seen in the report indicated in example (4), the epistemic scope is considered pragmatic.

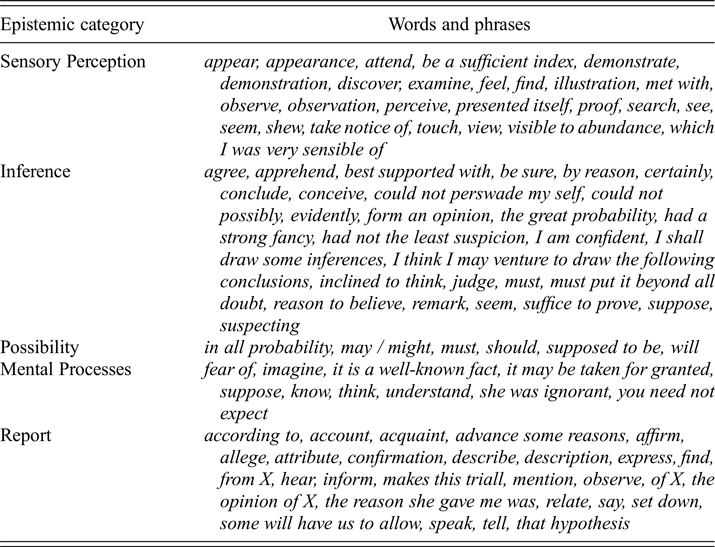

As for the categories of epistemic meaning, the bottom-up approach adopted in this study meant that no a priori categories were established before the data were analysed, but were rather established as part of the data analysis, albeit in line with categories already suggested in the literature on evidentiality and epistemic modality (Anderson Reference Anderson1986; Chafe Reference Chafe1986; Willett Reference Willett1988; Palmer Reference Palmer2001; Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2004; Bednarek Reference Bednarek2006; Boye Reference Boye2012), and on the history of scientific writing (Taavitsainen Reference Taavitsainen, Gotti and Dossena2001; Gray et al. Reference Gray, Biber and Hiltunen2011; Hiltunen & Tyrkkö Reference Hiltunen, Tyrkkö, Renouf and Kehoe2009, Reference Hiltunen and Tyrkkö2011; Whitt Reference Whitt2016a, Reference Whittb) and scientific knowledge (Kuhn Reference Kuhn, Lakatos and Musgrave1970; Latour & Woolgar Reference Latour and Woolgar1979; Snyder Reference Snyder, Achinstein and Snyder1994; Bates Reference Bates and Bates1995; Crombie Reference Crombie1995). They include Sensory Perception (visual or otherwise; see (6)), Inference (7), Possibility (8), Mental Processes (assumption, belief; see (9)) and Reports (10):

(6) But I found, on Examination, that her Womb was of no Bulk to contain a Child near its Time; and that its Neck, of an uncommon Hardness, was also clos'd so straitly, as to refuse the least Admission, even of a small Probe or knitting Needle. (LMEMT, 1722–1723_SC-PER_PT_Vol32_0387-0390.txt: Robert Houston, ‘An Account of an Extra-Uterine Foetus . . .’, PT, vol. 32 (1723), p. 387)

(7) If it was the Consequence of the violent Accidents which happen'd about the Time of the natural Birth, the Child then must have continued alive some considerable Time afterwards, during which these bony Excrescences were formed . . . (LMEMET, 1748_SC-PER_PT_Vol45_0131-0137.txt: James Mounsey, ‘An Abstract of the remarkable Case and Cure of a Woman . . .’, PT, vol. 45 (1748), pp. 136–7)

(8) . . . in this you must be cautious, for if you bind them too hard, it may cause an inflammation of the uterus. (LMEMT, 1795_SP-MW_Stephen_DomesticMidwife.txt: Margaret Stephen, Domestic Midwife (1795), p. 95)

(9) It is commonly believed to be muscular motion, and the fibres peculiar to the substance of the uterus are believed to be muscles. (LMEMT, 1794_SP-MW_Hunter_AnAnatomicalDescriptionOfTheHumanGravidUterus.txt: William Hunter, An Anatomical Description of the Human Gravid Uterus, and its Contents (1794), p. 26)

(10) Mr Portal remarks, that the cellular sheaths of those vessels are sometimes loaded with fat; and, in certain dropsies of the uterus, they are filled with water. (LMEMT, 1775_SC-PER_EMJ3_Vol3_0351-0358.txt: Anon., ‘Observations sur la Structure des Parties de la Génération de la Femme’, EMJ, vol. 3 (1775), p. 355)

Example (6) constitutes a marker of visual perception, and items signalling sensory perception are well known to signal evidentiality in certain contexts (Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2004; Whitt Reference Whitt2010; Grund Reference Grund2012, Reference Grund, Jucker, Landert, Seiler and Studer-Joho2013, Reference Grund2021),Footnote 15 although only visual and tactile perception appear in the current dataset. Authors sometimes signal they have arrived at a conclusion via inference in cases such as (7), whereas the claim is more tentative when a possibility or prediction is expressed, as in (8). The notions of certainty and possibility traditionally constitute the domain of epistemic modality (Palmer Reference Palmer2001; Boye Reference Boye2012), although here, markers of certainty or near certainty are classified as expressions of inference since they signal a conclusion is being drawn by the author, whereas a mere possibility is expressed in cases such as (8). There are also cases where authors indicate their information results from other mental processes such as assumption, belief or already existing knowledge, as in (9). Such a distinction between inferential and more general epistemic stance is also made by Grund (Reference Grund2021: 148ff.), and it is made here as well. Finally, when the information expressed by the relevant propositions is mediated through sources other than the author him/herself, as it is in (10), we find cases of reportative or quotative stance.

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Quantitative results

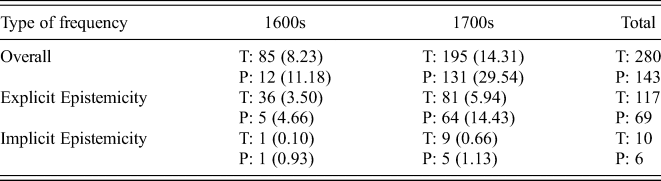

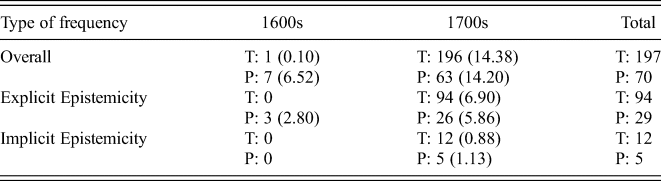

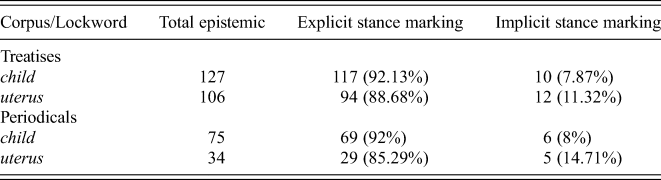

Tables 4 through 7 provide an overview of the quantitative behaviour of child and uterus in the two corpora. These figures reveal quite a bit of similarity in the data. Both the treatises and periodicals display a strong preference for explicit marking of epistemic stance (via syntactic scope); implicit (pragmatic) marking is a low-frequency phenomenon across all corpora and time periods, and it is nearly absent from all seventeenth-century data.Footnote 16

Table 4. Raw and normalised frequencies (per 10,000 words) of child in the Treatises (T) and Periodicals (P) corpora

Table 5. Raw and normalised frequencies (per 10,000 words) of uterus in the Treatises (T) and Periodicals (P) corpora

Table 6. Total number of hits of lockwords sampled plus proportion found to occur with epistemic stance markers in both corpora

Table 7. Proportion of explicit (syntactic) versus implicit (pragmatic) stance marking in both corpora

The proportion of epistemic marking – at least surrounding the two lockwords under investigation – also increases notably post-1700, although this can be at least partly explained by the fact that the eighteenth-century sample sizes are larger (constituting 56.98 per cent of the Treatises corpus and 80.52 per cent of the Periodicals corpus). It might also be due to the fact that, as discussed in section 2, it was only in the late seventeenth century that normal childbirth and reproduction moved from being an exclusively gynocentric affair to capturing the interest of medical men; this is especially clear with the figures for uterus, a more specialised term than the general child.

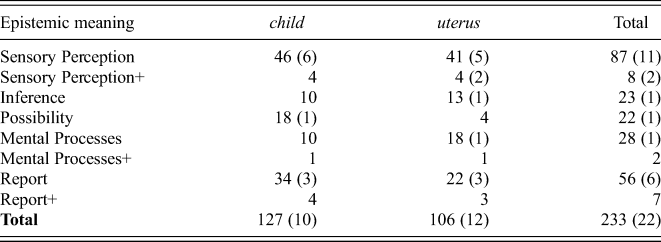

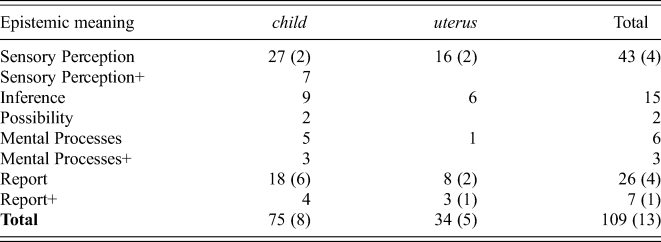

The types of epistemic meaning associated with each of the lockwords can be found in tables 8 and 9. Where multiple types of stance markers occur in the epistemic space of a single instantiation of the lockword, this is indicated by a ‘+’, although further distinctions (e.g. Report + Inference, Sensory Perception + Mental Process, etc.) are not made due to the very low frequency (< 5) of any particular combination.Footnote 17

Table 8. Epistemic meanings associated with child and uterus in the Treatises corpus

Table 9. Epistemic meanings associated with child and uterus in the Periodicals corpus

Again, the data reveal much similarity across the genres and time periods: in both corpora, sensory dominates as the type of epistemic stance surrounding the propositions containing child and uterus. Reporting of information from other sources – mediated knowledge – comes second in both corpora. Finally, markers of inference are the third most frequently appearing type of stance markers in the Periodicals corpus, whereas more general mental processes feature third in the Treatises corpus. Regarding PT, this at least partly confirms Atkinson's claim that the Royal Society placed primacy on knowledge or results acquired via ocular observation (Reference Atkinson1998: 23), although it should be noted that tactile perception – present in the current dataset as well, albeit to a lesser degree – also played a role in providing information to midwives and others involved with body-internal medicine (see Whitt Reference Whitt and Whitt2023). These results are also further confirmation of earlier studies on evidentiality in Early Modern English medical writing (Taavitsainen Reference Taavitsainen, Gotti and Dossena2001; Whitt Reference Whitt2016a, Reference Whittb), where it was discovered that expressions of first-hand knowledge (acquired via observation and mental processes such as inference) and the reports of others served as the primary evidential markers in the medical texts of the early modern period.

5.2 Further specifications of epistemicity

We will now take a closer look at the data, in part to differentiate the evidential uses, or those expressions indicating the writer's source of information from the non-evidential epistemic uses – generally an indication of someone other than the writer's knowledge or information source. This will also provide an opportunity to inspect the explicit vs implicit epistemic stance marking in a bit more detail. This combination of features allows us a multifaceted view of the semantics of epistemic stance, which is more extensive than previously discussed. The focus here is not narrowly on speaker/writer knowledge, without regard to how these speakers/writers use others’ knowledge in establishing their own epistemic stance, nor is the focus solely on items that exhibit only immediate syntactic scope over the propositions they modify (see Bednarek Reference Bednarek2006; Gray et al. Reference Gray, Biber and Hiltunen2011; Hiltunen & Tyrkkö Reference Hiltunen and Tyrkkö2011; Taavitsainen Reference Taavitsainen, Gotti and Dossena2001, Reference Taavitsainen, Jucker, Schreier and Hundt2009; Whitt Reference Whitt2016a, Reference Whittb). Instead, we will follow Bednarek (Reference Bednarek2006) in distinguishing between source and basis on the one hand, and attribution and averral on the other hand (see section 3). And although a precise account of the formal structure of these stance expressions falls beyond the purview of the current study, a list of the precise words and phrases involved in the signalling of epistemic meaning is presented in appendix 2.

Regarding sensory perception, most cases found in the current dataset involved the writer as source of the proposition – as well as the sensory act – by pointing to visual perception (and tactile, to a lesser degree) as the basis of knowledge. The observations of others were indicated less frequently, as were statements signalling generally perceivable phenomena without regard to any specific individual (i.e. no clear source). In the Periodicals corpus, observable attributes of child and uterus that serve as the basis of knowledge were also found. Some concrete examples best illustrate these trends:

(11) On the 12th, I saw him, and found his breathing bad, great stuffing, shrill voice, and a swelling externally on the superior part of the trachea. Pulse 140. Every thing looked ill. Steams, external fomentation, poultices, and several leeches were applied to the throat. 13th, the child greatly relieved, more chearful, and voice more natural. 14th, pulse much better, and the peculiarity of voice and the swelling almost gone. (LMEMT, 1765_SP-MW_Home_AnInquiryIntoTheNatureCauseAndCureOfTheCroup.txt: Francis Home, An inquiry into the nature, Cause, and Cure of the croup (1765), p. 13)

(12) On opening the body, the child and placenta were found in the cavity of the abdomen, entirely out of the uterus, which was of the size of a child's head of five years old, and was the round body which had been felt per vaginam. (LMEMT, 1787_SP-MW_Goldson_AnExtraordinaryCaseOfLaceratedVagina.txt: William Goldson, An extraordinary case of lacerated vagina, at the full period of gestation (1787), p. 47)

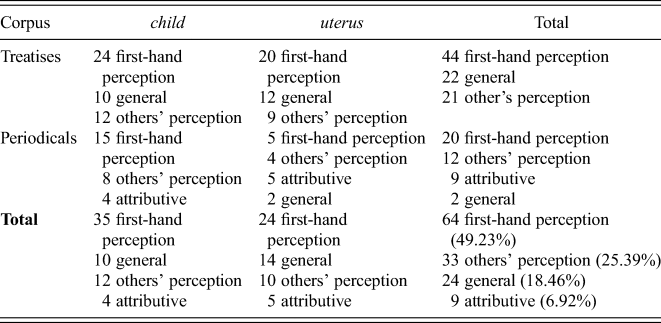

Example (11) is a straightforward case of evidentiality, whereby the author points to his own visual observation as their source of information. The child's state on August 13th (and 14th, in fact) is also due to the author's direct first-hand observation; however, this is made explicit only in previous propositions concerning the child's state on August 12th, but the pragmatic scope is fairly transparent due to the standard sequencing of the narrative: all of Home's comments about the child stem from his direct contact with and visual perception of the child (with auditory and tactile perception suggested here as well). Visual perception is also at play in example (12), but here, the author is simply reporting on what others perceived, rather than what he himself perceived, as his source of information. Generally perceivable phenomena are occasionally indicated as well (it will not be amiss to observe that),Footnote 18 and sometimes the perceived object serves as the stimulus necessary to make requisite observations about various attributes (the child demonstrates).Footnote 19 These distinctions show that evidential meaning involving the senses need not be immediately anchored in the speaker's/writer's act of perception, but in certain discursive contexts, others’ sensory perception can still serve as the basis (evidence) for a speaker or writer's knowledge (contra Whitt Reference Whitt2010). The precise breakdown of these uses can be found in table 10.

Table 10. Breakdown of the types of evidential meaning surrounding sensory perception in the two corpora

First-hand perception dominates throughout the data, while others’ perceptions serve as the author's source of knowledge as well. Information that is generally accessible via the senses occurs almost as frequently in the treatises, but it is all but absent in the periodicals. This is presumably due to the nature of the writings found in the periodicals: authors generally sought to emphasise their own findings in these publications, rather than reiterate the observations of others. Treatises, on the other hand, focused more on synthesising existing information rather than showcasing novel observations. Finally, the attributive use of sensory perception features in the Periodicals corpus as well, but it is absent in the Treatises, likely for the same reason: these perceived attributes constitute novel observations rather than existing knowledge.

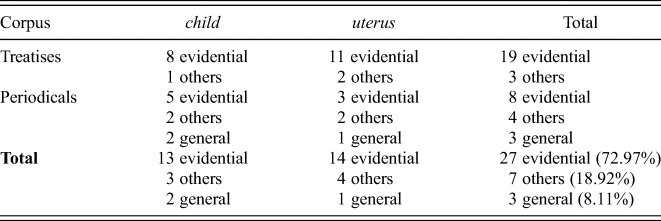

The same general trends apply to Inference. Evidentiality, with authors indicating their own acts of inferencing, is the most dominant type of marking (I conceive),Footnote 20 but there are also some references to the reasoning processes of others:

(13) This last labour, in which she was attended by the widow Mauger, a midwife of the same town, began with so considerable a discharge of water, that it was judged, not without reason, that her pregnancy was attended with a dropsy of the uterus. (LMEMT, 1767_SC-PER_PT_Vol57_0001-0020.txt: Claude Nicholas Le Cat, ‘A monstrous human Foetus, having neither Head, Heart, Lungs, Stomach, Spleen, Pancreas, Liver, nor Kidnies’, PT, vol. 57 (1767), p. 2)

Here, Le Cat ascribes these mental processes to someone other than himself, namely those who were present at the actual labour in question. Unlike with non-authorial sensory perception discussed above, one could argue a case such as this is non-evidential because the author is simply reporting on what others believe or have concluded rather than necessarily taking a position on the matter themselves. Even so, it is the author who chooses to deploy these epistemic markers in the first place, thereby indicating that a mental process (basis) of someone else (source) serves as the basis of their own knowledge. This may or may not constitute evidentiality in the strictest sense of the term, but it is certainly a case of epistemic stance because the author positions their claim – about a uterus, in this instance – in some sort of epistemic space where the inference process is both explicit and prominent. There are also a few indications of conclusions that anyone in possession of certain information should and would be able to make (X gives Reason to believe);Footnote 21 that is, the author indicates that the presence of certain facts should lead anyone (himself included) to arrive at a specified conclusion. As this involves the author's inference, it is unambiguously evidential. Table 11 illustrates that the quantitative trends are almost parallel in both corpora.

Table 11. Breakdown of the types of meaning surrounding inference in the two corpora

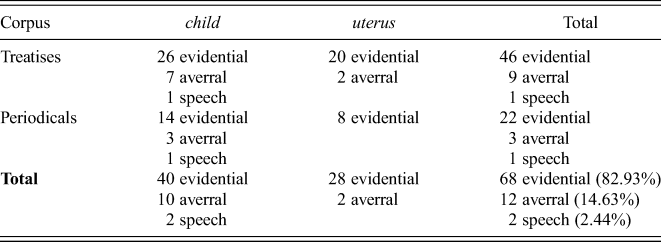

Evidentiality is also the most dominant epistemic use of cases of the Report category, that is, the authors point to someone else's work as their source of information (attribution).Footnote 22 Interestingly, similar formulations involving authors pointing to their own writings (averral; see Bednarek Reference Bednarek2006: 642ff.) – either elsewhere in the same text or to another text entirely – are also found in the data:

(14) And first of all, yong women commonly are with child rather of a boy then of a wench, because they be hoter then the elder women, which was obserued by Aristotle, who saith farther, that if an aged woman which neuer had children before, chance to conceiue, one may be sure it will be a wench. (EMEMT, 1612_Guillemeau_Childbirth.txt: Jacque Guillemeau, CHILD-BIRTH OR, THE HAPPY DELIVERIE OF VVOMEN (1612), p. 9)

(15) In the cases of Mrs. Wilkins, and the others which I have related as lacerations of the vagina, the hemorrhage was not very great, and the uterus was found contracted to the usual size it would have been . . . (LMEMT, 1787_SP-MW_Goldson_AnExtraordinaryCaseOfLaceratedVagina.txt: William Goldson, An extraordinary case of lacerated vagina, at the full period of gestation (1787), p. 73)

Example (14) is evidential, allowing the author to cite other texts as their information source. Interestingly, the attribution to a classical source (Aristotle) was found only in the seventeenth-century data; this is no doubt a continuation of the scholastic tradition, whereby the texts of antiquity were authoritative above any other information source, even direct observation (see Whitt Reference Whitt2016a, Reference Whittb; Taavitsainen Reference Taavitsainen and Whitt2018). There is a change of focus in (15), whereby Goldson points to himself as the source of information, discussed in greater detail elsewhere in his writings (which I have related). There are also a few rare cases where knowledge about child finds itself expressed in an actual conversational exchange. Table 12 provides the frequencies and distribution of these uses.

Table 12. Breakdown of the types of meaning surrounding reports in the two corpora

6 Final remarks

This study has provided an overview of epistemic space in Early Modern English texts on midwifery and childhood, as a representative snapshot of Early and Late Modern English medical writing more broadly. Evidential meaning is most prominent throughout the major categories of epistemic stance markers, although there are a number of other related meanings that involve the knowledge of someone other than the writer. By focusing on the most common items shared between two corpora (the lockwords child and uterus), this study has been able to uncover a wide range of epistemic meanings expressed in the early days of printed vernacular medical writing, as well as a range of already widely discussed items such as perception verbs and markers of inference (the full range of markers can be found in appendix 2). Despite their different functions (didactic vs informative), the treatises and periodicals display remarkably similar behaviour: both favour explicit (syntactic) marking of epistemic stance and generally favour the same types of epistemic meanings in regards to propositions involving the two lockwords under investigation.

Evidentiality dominates in both genres and with both lockwords, and aside from an increase in the general use of epistemic stance markers, no diachronic trends could be found. Previous research on Early Modern English medical writing (Taavitsainen Reference Taavitsainen, Gotti and Dossena2001, Reference Taavitsainen, Jucker, Schreier and Hundt2009, Reference Taavitsainen and Whitt2018; Hiltunen & Tyrkkö Reference Hiltunen, Tyrkkö, Renouf and Kehoe2009; Whitt Reference Whitt2016a) has uncovered diachronic developments regarding epistemicity during the period under investigation here. Perhaps by focusing only on specific forms, other forms of epistemic stance marking (particularly multi-word expressions) are missed (cf. Kohnen's Reference Kohnen, Fitzmaurice and Taavitsainen2007 concept of ‘hidden manifestations’). By starting with lockwords, one can uncover all forms of epistemic stance marking within range of particular key concepts, so maybe the diachronic change is not as stark or clear-cut as previously suggested. This investigation has also shown how such meaning can be pragmatically indicated or implied through scoping not restricted to the immediate syntactic context of the proposition in question (see also Grund Reference Grund2017, Reference Grund2021). Even though this phenomenon is nowhere near as frequent as the oft discussed explicit marking of epistemic stance, it does show how general textual conventions and the broader discourse context play just as significant a role as the immediate syntactic or sentential environment (as found, for example, with matrix clauses). Again, taking these uses into account might well paint a different picture of alleged changes in epistemic stance marking through time. This might also explain why few generic differences could be found; when one takes a full swathe of single- and multi-word epistemic stance markers into consideration, differences are perhaps not as stark as once believed.

An obvious drawback here is that an epistemic marker scoping over the proposition may occur much earlier in the discourse, well beyond what can be shown in a KWIC concordance line. Consider the following from Dr Douglas’ contribution to PT:

-

(16)

(a) I Lately opened the Body of a Woman, aged 27, who dyed the third day after Delivery, on which I made the following remarks.

(b) Having carried home this large Bag, with the Uterus appendant, cut off below the Orifice of the Meatus Urinarius, and viewed it at leisure, I observed . . . (LMEMT, 1706–1707_SC-PER_PT_Vol25_3217–2327: Dr. Douglas, ‘An Account of a Hydrops Ovarii’, PT, vol. 25 (1706–7), p. 2317 (a), p. 2320 (b))

Each of these statements either implicitly or explicitly suggests that ocular observation serves as Douglas’ source of knowledge, and both are followed by lengthy lists of the various observations made. However, the textual distance between these propositions and the mention of information source can range from a few sentences to several paragraphs. Yet these statements necessarily scope over each and every enumerated item (and the attendant propositions) on their respective lists. That is, almost every proposition appearing within these lists falls within the scope of visually acquired evidence on the part of Douglas. Such uses have not been picked up in the current study, partly due to the focus on lockwords rather than on the epistemic markers themselves; at the same time, the bottom-up approach employed here has allowed us to uncover a broader range of items and meanings possible than with conventional searches for ‘the usual suspects’ (Plappert Reference Plappert2017: 425; see also Landert Reference Landert, Suhr, Nevalainen and Taavitsainen2019). Such text- or discourse-level use of epistemic stance has remained fairly unaddressed in the literature on the subject, whether in more general typological overviews or those focused on scientific or medical writing in particular. The wide range of nuanced meanings expressed in broad categories such as perception and inference has also been explored.

This study has hopefully paved the way for further investigations along these lines, combining the bird's-eye view provided by corpus techniques with close reading and sociohistorical contextualisation. One obvious place to start would be to look at the particular syntactic configurations involving stance markers that tend to occur in the epistemic space of certain lockwords (such as complement clauses), thus establishing a ‘local grammar’ (Hunston & Sinclair Reference Hunston and Sinclair2000) of this space. And how similar or different are these grammars among different lockwords (and in different genres)? This study has hopefully served as first step into this new avenue of exploring medical writing, and epistemic stance more broadly.

Appendix 1

List of EMEMT and LMEMT texts used in the Periodicals corpus

The following list features the filenames of the specific EMEMT and LMEMT texts that comprise the ad hoc Periodicals corpus created for this study. As can be seen, the filename contains the year of publication, the abbreviation of the periodical (PT, EMJ or GM), the volume and page range of the contribution. Information concerning matters such as author and title can be found in the metadata of each file.

EMEMT (all PT)

1667_pt2_576-9

1668_pt3_663-4

1668_pt3_750-2

1669_pt4_969-70

1669_pt4_1043-7

1669_pt4_1047-50

1672_pt7_4098-5001

1693_pt17_817-24

1694_pt18_020-3

1694_pt18_103-4

1694_pt18_111-2

LMEMT

PT

1706–1707_SC-PER_PT_Vol25_2317-2327

1706–1707_SC-PER_PT_Vol25_2387-2392

1708–1709_SC-PER_PT_Vol26_0420-0423

1712–1713_SC-PER_PT_Vol28_0165-0166

1712–1713_SC-PER_PT_Vol28_0236-0237

1722–1723_SC-PER_PT_Vol32_0387-0390

1724–1725_SC-PER_PT_Vol33_0008-0015

1731–1732_SC-PER_PT_Vol37_0279-0284

1735–1736_SC-PER_PT_Vol39_0049-0053

1739–1741_SC-PER_PT_Vol41_0294-0307

1739–1741_SC-PER_PT_Vol41_0814-0819

1746_SC-PER_PT_Vol44_0617-0621

1748_SC-PER_PT_Vol45_0131-0137

1751_SC-PER_PT_Vol47_0092-0095

1755_SC-PER_PT_Vol49_0254-0264

1767_SC-PER_PT_Vol57_0001-0020

1770_SC-PER_PT_Vol60_0451-0453

1775_SC-PER_PT_Vol65_0311-0321

1781_SC-PER_PT_Vol71_0372-0373

EMJ

1747_SC-PER_EMJ1_Vol1_0269-0270

1747_SC-PER_EMJ1_Vol3_0220-0222

1756_SC-PER_EMJ2_Vol2_0338-0341

1774_SC-PER_EMJ3_Vol2_0072-0077

1774_SC-PER_EMJ3_Vol2_0077-0079

1774_SC-PER_EMJ3_Vol2_0300-0302

1775_SC-PER_EMJ3_Vol3_0351-0358

1779_SC-PER_EMJ3_Vol6_0217-0218

1779_SC-PER_EMJ3_Vol6_0258-0262

1781–1782_SC-PER_EMJ3_Vol8_0329-0332

1785_SC-PER_EMJ3_Vol10_0102-0107

GM

1743_GEN-PER_GM_Vol13_0484

1792_GEN-PER_GM_Vol62_0937

1792_GEN-PER_GM_Vol62_1024

Appendix 2

Words and phrases used in the expression of epistemic meaning