1 Introduction

Following an early focus on well-defined speech communities (e.g. Labov Reference Labov1966), later work in variationist sociolinguistics shifted towards studying the mobility of multilinguals and immigrants as a significant factor in language change (Horvath & Sankoff Reference Horvath and Sankoff1987; Kotsinas Reference Kotsinas1988; Rampton Reference Rampton1995). At the forefront of this focus on mobility has been research on the innovative speech practices associated with young people in multiethnic, multilingual friendship groups (Cheshire, Nortier & Adger Reference Cheshire, Nortier and Adger2015). A term coined by Clyne (Reference Clyne2000), multiethnolects have been identified across urban centres in Europe, including, but not limited to, Berlin (Wiese Reference Wiese2009), Oslo (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009), Copenhagen (Quist Reference Quist2005), and Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö (Bodén Reference Bodén, Quist and Svendsen2010; Kotsinas Reference Kotsinas1988) (although see Madsen Reference Madsen2011 and Rampton Reference Rampton2015 on issues with the focus on youth and ethnicity respectively); multiethnolects are typically argued to be in use both among young people from marginalised ethnic groups and among the societally dominant ethnic group.

In London, an extensive amount of research has led to the identification of Multicultural London English (MLE) (Fox Reference Fox2007, Reference Fox2015; Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox & Torgersen Reference Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox and Torgersen2011; Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill & Torgersen Reference Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill and Torgersen2013; Gates Reference Gates2019; Ilbury Reference Ilbury2019), with Cheshire et al. (Reference Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill and Torgersen2013: 65) describing MLE as ‘an ethnically neutral variable repertoire that contains a core of innovative phonetic, grammatical and discourse-pragmatic features’. It has been claimed by Cheshire et al. (Reference Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox and Torgersen2011) that MLE, following Labov's (Reference Labov1972) definition of the ‘vernacular’, may now be the new vernacular variety of English in London for a sizable portion of young people (see also Kircher & Fox Reference Kircher and Fox2021 on the use of MLE by speakers into their fifties) living in working-class, multiethnic inner-city neighbourhoods. Although the identification of similar features elsewhere in the UK – including Birmingham (Khan Reference Khan2006) and Manchester (Drummond Reference Drummond2016, Reference Drummond2018) – has led to calls for less region-specific terminology (Fox, Khan & Torgersen Reference Fox, Khan and Torgersen2011; Drummond Reference Drummond2016), young people undoubtedly remain at the centre of research on urban vernaculars, both in the UK and beyond. Notably, those studies that have focused on London have done so in areas of East London, with the generalisability of their findings as representative of London's adolescents, broadly construed, yet to be addressed.

Alongside objections to the region-specific identification of MLE, there are also broader objections to the term ‘multiethnolect’ among some sociolinguists working on adolescent speech in urban centres. The objection is principally centred on the way in which ethnicity is placed at the forefront, at the risk of homogenising or othering speakers of such varieties (Svendsen Reference Svendsen2015), and of overemphasising the relevance and systematicity of ethnicity in these speech styles (Madsen Reference Madsen2011). In London specifically, work by Gates (Reference Gates2019) suggests that earlier claims about the ethnic neutrality of MLE may not hold in certain contexts, namely those in which a usually dominant ethnic group is in the minority where the assertion of ethnic identity can take on more importance. For the sake of continuity with previous studies (Quist Reference Quist2008; Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox and Torgersen2011), the terms ‘multiethnolect’ and ‘Multicultural London English’ will be used in this article where relevant (e.g. when other authors have chosen to do so), though we have elected not to explicitly identify our participants as speakers of MLE, preferring instead to focus on a comparison between the use (and non-use) of certain epistemic phrases by adolescents in our dataset and those in other European cities and in other areas of London.

That the speech of adolescents has been privileged in multiethnolect research speaks to a number of factors that characterise the lives of young people, particularly in urban centres. More broadly in sociolinguistics, adolescents have been characterised by high levels of linguistic innovation (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2016), evidenced by adolescent peaks in changes in progress (Labov Reference Labov, Eckert and Rickford2001), which results in ‘studies of adolescents provid[ing] the latest insights into processes of variation and change’ (Kirkham & Moore Reference Kirkham, Moore, Chambers and Schilling2013: 280). The intense social context of adolescence, in which teenagers face isolation from adjacent age cohorts (no longer children, not quite adults) and pressure to form friendship groups within their cohort (Eckert Reference Eckert1989), leads, unsurprisingly, to a propensity for linguistic invention.

The pressurised nature of adolescent interaction and the subsequent pressure to form a social identity are reflected in the discourse-pragmatic features prevalent in adolescent speech, particularly pragmatic markers, which ‘express the relation or relevance of an utterance to the preceding utterance or to the context’ (Torgersen, Gabrielatos, Hoffmann & Fox Reference Torgersen, Gabrielatos, Hoffmann and Fox2011). Such markers index utterances to different discourse planes, including the ideational structure (ideas and propositions) and participant framework (the speaker–hearer relationship) (Schiffrin Reference Schiffrin1987), as well as social identities and stances (Ochs Reference Ochs, Gumperz and Levinson1996). In the race to define one's own social identity, adolescents make frequent use of such linguistic devices to structure social interaction.

We find increased use of such devices in sociolinguistic studies of adolescent discourse-pragmatic variation. For example, both Ito & Tagliamonte (Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003) and Fuchs (Reference Fuchs2017) find that adolescents in the UK lead in usage of intensifiers. Relatedly, Martínez & Pertejo (Reference Martínez and Pertejo2012: 791) find that ‘English teenagers not only tend to intensify language more often than adults, but they are also more emphatic in their expression.’ Intensifiers are also a common site of linguistic innovation. New intensifiers are unlikely to stick around for long, as they derive their impact from their novelty (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2016). As a result, speakers and particularly teenagers must occasionally reinvent them.

Similarly, young people frequently seek to mark epistemic stance, that is, the degree to which they are committed to the information they are providing to the discourse (Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003). In her study of adolescent males in London, Castell (Reference Castell2000) found her speakers’ speech to be dense with discourse markers such as you know and you know what I mean, which express epistemic modality. Across studies of a number of different European multiethnolects (Kotsinas Reference Kotsinas1988; Quist Reference Quist2008; Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009; Freywald, Mayr, Özçelik & Wiese Reference Freywald, Mayr, Özçelik and Wiese2011), one particular class of epistemic phrases has risen to the fore: swear-phrases.

In this article we report on the use of a set of related phrases used by adolescent speakers in the West London borough of Ealing, including (I) swear (down), wallah(i), on X's life and say swear/wallah/mums. We do this by reporting the quantitative distribution of such phrases across the adolescent speakers and by using discourse-analytical techniques typical in interactional sociolinguistics (Rampton Reference Rampton2010) to examine the context-specific functions of these phrases in specific extracts. Through this analysis, we find remarkable similarities between how these phrases are used in the English of adolescents in West London and how they have been borrowed into other West European languages.

By first examining the quantitative distribution of swear-phrases among a community of adolescents in London, we aim to reveal the type of orderly heterogeneity which discourse-pragmatic variables can show, despite their relative neglect in variationist sociolinguistics (Pichler Reference Pichler2013). In following this with a more detailed interactional analysis of occurrences of swear-phrases embedded in both interviews and naturally occurring conversations, we then move beyond simply looking at the social stratification of swear-phrases, towards an understanding of how speakers use such phrases to construct ‘shared and specific understandings of where they are within a social interaction’ (Heritage Reference Heritage, Fitch and Sanders2004: 104). This second analysis mirrors the approach of Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009) to wallah in Oslo. By combining these approaches, we provide a snapshot of the interactional function of swear-phrases by adolescents in Ealing, demonstrating remarkable cross-linguistic similarity to swear-phrases as used by similar adolescent peer groups in other major European cities.

While English swear-phrases have been attested in adolescent speech in areas of East London, in both the original MLE corpus (Kerswill, Cheshire, Fox & Torgersen Reference Kerswill, Cheshire, Fox and Torgersen2007, Reference Kerswill, Cheshire, Fox and Torgersen2010) and more recent 2019 data from Hackney (Ilbury Reference Ilbury2019),Footnote 2 the use of the Arabic-borrowed wallah(i) by British adolescents is, to our knowledge, as yet unattested in the sociolinguistics literature. Furthermore, while wallah(i) appears to be widespread across other European multiethnolects (Kotsinas Reference Kotsinas1988; Nortier Reference Nortier2001; Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009; Freywald et al. Reference Freywald, Mayr, Özçelik and Wiese2011; Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2015), based on our relatively limited data, its use in West London appears to be as yet (a) pragmatically restricted and (b) only licensed by Muslim speakers.

2 Epistemic phrases

Following Kärkkäinen (Reference Kärkkäinen2003: 1), we will define epistemicity as comprising ‘linguistic forms that show the speakers’ commitment to the status of the information that they are providing, most commonly their assessment of its reliability’ (see also Prieto & Borràs-Comes Reference Prieto and Borràs-Comes2018). The expression of epistemic stance can be assessed at different levels of interaction: at the level of the linguistic form chosen; at the level of the intonation unit; and at the level of the turn-taking structure. Speakers show a tendency to mark their epistemic stance at the beginnings of intonation units (Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003: 4). Importantly, and in a departure from semantic studies in which the truth of propositions is the focus, truth is not the primary issue when it comes to the analysis of epistemics at the interactional level (cf. Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2015). Rather, speakers are more concerned with showing how confident they feel in the truth or reliability of what they are telling (Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003: 18).

In a corpus of American speech, Kärkkäinen (Reference Kärkkäinen2003: 53) finds that the most common semantic meanings for expressions of epistemic stance in the data are, in descending order: reliability (of the information being expressed); belief (strength of the speaker's belief in what they are saying); hearsay evidence; mental construct e.g. I imagine, I thought; deduction; induction; sensory evidence. Reliability and belief are far and away the most common, followed by hearsay evidence.Footnote 3 Kärkkäinen (Reference Kärkkäinen2003: 54) observes that within the categories of reliability and belief, speakers ‘tend to express low rather than high reliability, and a weak rather than strong belief, and thus generally express a low degree of confidence’. The same epistemic phrase is capable of expressing either high confidence/reliability or low confidence/reliability, dependent on context. The phrase I think, Kärkkäinen (Reference Kärkkäinen2003) argues, can convey either strong conviction, or doubt. As we will show with our own data, the same is true of I swear.

Following Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2015), we take a form-based approach. Form-based approaches take as their starting point ‘either an individual lexical item or an underlying multi-word construction’ (Waters Reference Waters2016: 46). Taking wallah/wallahi as the starting point for our variable selection, a set of related constructions are analysed in this article, including wallah/wallahi and swear/I swear. We opted for this form-based approach over both the function- and position-based approaches because many discourse-pragmatic features serve multiple functions simultaneously at different levels of the discourse, and in many instances, there will be ambiguity as to which function prevails. In taking a form-based approach, we can compare phrases from different language varieties with the same underlying semantic meaning and compare their function across speakers from a multicultural community (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet Reference Eckert and McConnell-Ginet1992).

We therefore opted to include any phrases with an underlying semantic meaning of ‘I swear’ in our analysis. The first-person subject did not need to be present, and nor did the swearing verb – for example, on [my/your] mother's/mum's life was included, which sometimes appears with a first-person subject and the verb swear, i.e. I swear on my mum's life, but can also appear in the form on my mum's life or mum's life. Many of the constructions included in our analysis can also be found in the MLE corpus (see table 1). Throughout the analysis of our data in section 5 below, we will draw comparisons between the current, Ealing data and this older data from Hackney (the MLE corpus), as well as more recent 2019 data from Hackney (collected by Ilbury Reference Ilbury2019). This allows us to compare the functions that the different epistemic phrases have served at different points in time, in two different boroughs of London.

Table 1. Examples of epistemic phrases found in the MLE corpus

The epistemic phrase of the greatest interest in the current study is wallah. Wallah is an Arabic construction comprising the particle waw ‘by’, Allah and the genitive ending -i, which may variably be dropped, so that it can be pronounced either wallahi or wallah (Al-Khawaldeh Reference Al-Khawaldeh2018). Although wallahi is therefore the full form and is reportedly more common than the wallah variant (at least in Jordanian Arabic; Al-Khawaldeh Reference Al-Khawaldeh2018: 115), we will use wallah to refer to both the wallah and wallahi forms, in keeping with other studies of European multiethnolects (Quist Reference Quist2008; Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009; Freywald et al. Reference Freywald, Mayr, Özçelik and Wiese2011).

The earliest study of multiethnolects in Europe, Kotsinas (Reference Kotsinas1988), cited wallah as an example of an Arabic loanword that was used in Rinkeby Swedish. Since then, wallah has been attested in multiethnolectal speech in Danish (Quist Reference Quist2008), Norwegian (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009; Svendsen Reference Svendsen2015), Finnish (Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2015), German (Kallmeyer & Keim Reference Kallmeyer, Keim, Androutsopoulous and Georgakopoulou2003; Freywald et al. Reference Freywald, Mayr, Özçelik and Wiese2011) and Dutch (Nortier Reference Nortier2001). More recently, wallah has been noted in Toronto English (Denis Reference Denis2019), with younger Somalis in Toronto sometimes referred to as the ‘say-walahi’ generation by older Somalians (Ilmi Reference Ilmi2009). Notably, the use of wallah has not previously been analysed in a variety of British English.

Many of these studies converge in seeing wallah and related phrases as markers of a particular urban adolescent speech style: ‘Conversations among adolescents in multiethnic areas in Oslo seem to be characterized by the use of a set of discourse markers which emphasize the truth value of utterances, thus contributing to an extended degree of epistemic focus’ (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009: 221). Similarly, Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2015) sees the use of wallah and Finnish counterparts ma vannon (‘I swear’) and ma lupaan (‘I promise’) as defining such a speech style, suggesting that the multilingualism of speakers and communities has precipitated grammatical changes in the Finnish phrases (although see Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009).

Regarding the distribution of wallah across different speakers, Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009) finds that boys are its chief users, accounting for 119 out of 137 tokens (87%) in a recent corpus of Oslo youth speech. Of these 119 tokens, 111 are from boys with two parents born outside Norway. Meanwhile, in Helsinki, wallah is predominantly used by Muslim adolescents, by boys more than by girls, and by those with multiethnic friendship circles more than those with ethnically homogeneous friendship circles (Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2015). Finally, in Toronto, there is anecdotal evidence of wallah having become enregistered as Toronto Slang (Denis Reference Denis2021).

In interaction, wallah has been shown to function in a variety of ways. Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009) suggests that wallah is not treated by adolescents as a literal swear. A primary use of wallah appears to be intensification (Svendsen Reference Svendsen2015). When spoken with rising intonation, wallah can function as an intensifier to emphasize the importance of a particular statement (Quist Reference Quist2008). Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009: 228) suggests that, in argumentative contexts, ‘the emphasizer wolla Footnote 4 seems to upgrade an assertion or an assessment’, emphasizing that it ‘appears to be an efficient verbal device for winning an argument’ (see also Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2015).

Wallah can also play a role in the speaker's stance towards the whole interaction, not just their stance towards individual statements therein. Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2015: 183), for example, treats wallah as marking a particular storytelling ritual, suggesting that wallah and associated phrases can signpost a ‘sensational news’ genre. This genre is partly a collaborative creation: other participants must ratify the story as being newsworthy. The narrative will often be preceded by an introductory sequence (Routarinne Reference Routarinne and Tainio1997) in which the narrator offers a story, and the listeners promise to give up the floor for the duration of the telling. Yet the narrative is constructed in cooperation with the listeners. Lehtonen asserts that in her data, there is often an introductory sequence in which the narrator offers a story preface, and the listeners react. Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2015: 187) argues that wallah or its equivalent often appears at the onset of sensational news telling, and signals the narrator's stances towards the entire story, justifying the novelty and tellability of the events to be told, as well as communicating the narrator's responsibility for the story.

3 Data collection

The data used in this article was collected as part of a study on whether MLE features were in use in West London; please see Oxbury (Reference Oxbury2021) for more in-depth information on the field site and the participants. Basic demographic information from the participants is available in Appendix A. The data was collected from January to September 2017 at a youth centre situated in the West London borough of Ealing (see figure 1); this youth centre will henceforth be referred to using the pseudonym Deerpark Youth Centre. Ealing was originally chosen for this study due to the highly multilingual nature of the borough, with over 100 languages represented in addition to English, including high numbers of Polish, Punjabi, Somali and Arabic speakers (Mangara Reference Mangara2017).

Figure 1. Map of London with the borough of Ealing highlighted in pink (www.londoncouncils.gov.uk/node/30047)

The data collection involved a mixture of ethnographic participant observation, sociolinguistic interviews and self-recordings. Sociolinguistic interviews took place in a room in the youth centre, with one interviewer and two interviewees, following the method used by Cheshire et al. (Reference Cheshire, Kerswill, Fox and Torgersen2011). The interviews covered topics including race and ethnicity, including discrimination; fights; childhood; the local area and growing up in London; music; religion and superstition; future plans; language. For self-recordings, participants were given a H2n Zoom with a lavalier mic, which the majority opted to carry in their pockets or in their bag while they went about their day in the youth centre. The quantity and size of extracts has been reduced for this article; please see Oxbury (Reference Oxbury2021) for the full extracts and further, similar examples to those shown here.

4 Quantitative distribution of epistemic phrases in West London

In this section we present a distributional analysis of the use of epistemic phrases across participants. This analysis considers only the surface forms of the different features. For example, all tokens of I swear are grouped together irrespective of their pragmatic function (which we consider in section 5). We do not therefore distinguish in this section between those that indicate a speaker's strong conviction (in other words, high speaker conviction) or a speaker's doubt or uncertainty (low speaker conviction). Interview data and self-recorded data are analysed separately, as the use of epistemic phrases was expected to be inhibited in the interviews compared to self-recorded data (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009). In total, the interview data consists of 232,666 words from 18 speakers, while the self-recorded data comprises 18,228 words from 11 speakers (see Appendices B and C for breakdowns of the raw token numbers by speaker and by swear-phrase). Figure 2 shows different participants’ rates of use of the various epistemic phrases in the interview data.

Figure 2. Participants’ frequency of use of different epistemic phrases in the interviews

Notably, 12 out of 30 participants did not use any of these epistemic phrases in their sociolinguistic interviews, while the other 18 did so infrequently. All of the epistemic variants except for say mum's appear in the interview data. As was expected, the epistemic phrases are more frequent in the self-recorded data, despite the number of participants contributing self-recorded data being lower. Figure 3 shows the frequencies of the epistemic phrases for participants who contributed to the self-recordings.Footnote 5

Figure 3. Participants’ frequency of use of different epistemic phrases in the self-recordings

The major finding from the distributional analysis is that wallah and say wallah are only used by adolescents who identified as Muslim: Ahmed, Ali, Sami, Karim, Tariq, Khadir, Sqara, Ibrahim, Omar, ZR, Lola and Amanda. The exception is CB, who did not describe himself as Muslim but stated that his father was Muslim. Meanwhile, the other phrases with say (say mum's, say swear) are used by CB, Tariq and Ahmed, but also by Shantel, Chantelle and Raphael.

The distributional analysis found that overall, the epistemic phrases occur at higher rates in the self-recorded data compared to the interview data, as previously mentioned. When epistemic phrases did appear in the interview data, they were typically in situations where more than two interviewees were present and the interview had become a group discussion, and/or in ‘byplay’ (Goffman Reference Goffman1981: 134), when the interviewees directly addressed one another and the interviewer was momentarily excluded. This suggests that the use of epistemic phrases, especially the more innovative ones, is primarily an in-group phenomenon and is inhibited by the presence of an outsider. Notably, Ilbury (Reference Ilbury2019) observed a similar trend in his analysis of another MLE discourse-pragmatic feature, namely the man pronoun.

It was also found that wallah and say wallah are only used by Muslim young people in the current data. By contrast, Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009) found instances of adolescents with two Norwegian-born parents (though she does not specify their religion) using wallah. Similarly, Quist (Reference Quist2008) mentions ethnically Danish boys who are users of multiethnolect, presumably including wallah. The absence of such findings in our study would suggest that wallah and say wallah are not multiethnolectal features in our data, because unlike in the Norwegian and Danish data, their use does not appear to have spread to non-Muslim adolescents. Rather, they are better described as ethnolectal features. However, other say phrases – say on your mum's life and its contraction say mum's – show wider distribution, with use among non-Muslim identifying speakers; we will return to this in the discussion.

Interestingly, say swear is also attested in the 2019 Hackney data. The adolescent participants studied by Ilbury (Reference Ilbury2019) were predominantly Christian, rather than Muslim (personal communication), and wallah and say wallah are not found in his data. Taking the current data and the 2019 Hackney data together, we could conclude that, currently, wallah and say wallah tend to be used only in Muslim friendship groups, but that the related say phrases are used more widely by different adolescents in London; this is perhaps unsurprising given that swear-phrases and say phrases are attested in the 1994 British National Corpus Footnote 6 (BNC Consortium 2007).

5 Forms and functions of epistemic phrases in West London

We will now present examples of epistemic phrases found in the Deerpark data, examining their function and their position, e.g. whether they can stand alone, whether they must appear at the left periphery or at the right periphery of an utterance, what intonation contours they host. Regarding sentence position, Opsahl noted increased flexibility of position in her Oslo data, i.e. movement from the left periphery to utterance-final position or status as an independent utterance, citing this as a sign of grammaticalisation (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009: 237).

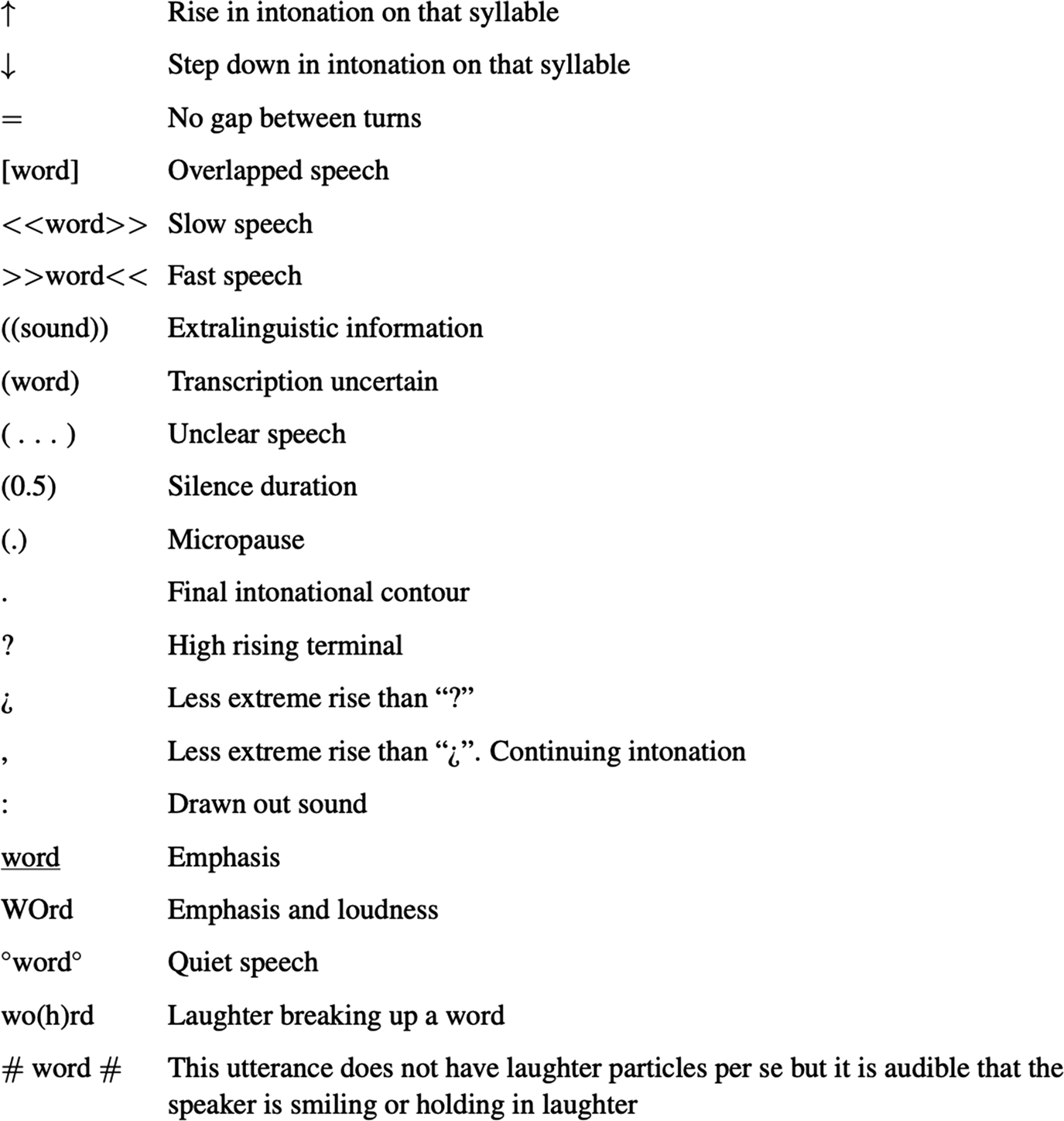

Examples from the current data have been transcribed in a way that chiefly adheres to Conversation Analytic transcription conventions, following the methodological approach taken by Sidnell (Reference Sidnell2010: ix) (see Appendix D). Our analysis also pays attention to intonation units (Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003: 9); intonation units are fundamental units of discourse production (Chafe Reference Chafe and Givón1979) that can span across multiple clauses (Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003). Our transcription separates speech into intonation units such that (except for example (10)) each line is a separate intonation unit seen as a stretch of speech uttered under a single intonation contour.

These phrases are primarily treated as epistemic phrases (Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003; Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2015), and there is a focus on whether they show high or low speaker commitment. At the same time, attention is paid to the discourse-structuring and interpersonal functions of these phrases, as have been described by previous research (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009; Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2015), and as such they are treated as multifunctional discourse-pragmatic features, having functions at several levels of the discourse simultaneously. In doing so, we follow Wiltschko, Denis & D'Arcy (Reference Wiltschko, Denis and D'Arcy2018) in separating out the principal function of this set of epistemic phrases (i.e. swearing commitment) from the function(s) of the form in context (e.g. marking newsworthy responses, attention getting, sequence closing etc.), which can be derived using other relevant linguistic components of context, including syntactic, prosodic, discourse and social contexts.

5.1 (I) Swear (down)

We begin with variations of the construction I swear. As Kärkkäinen (Reference Kärkkäinen2003) has shown with I think, I swear can signal either a high or a low degree of confidence. In our data, this can be seen in the following extracts. Firstly, in example (1), Sqara has told a story about how, during the Syrian uprising, he was chased, and someone shot at him. Speaker commitment is directly challenged in this instance: the interviewer observes that Sqara is smiling (and his laughter is audible in line 2) and asks one of his friends if Sqara is telling the truth. The interviewer thus expresses doubt about the truthfulness of Sqara's story. Sqara's two friends, Karim and Ahmed, both immediately answer in the affirmative, and Sqara uses I swear apparently to convince the interviewer of the truth of his story. In this way, I swear is used to index speaker commitment at a moment when speaker commitment is being challenged. I swear is used in conjunction with repetition of the phrase it's serious.

(1)

This contrasts with the uses of I swear in 2, 3 and 4, each of which index a low degree of speaker belief, or the unreliability of knowledge. In example (2), CB has just seen a friend, who he believed had been banned from attending the youth centre, enter the centre. I swear co-occurs with oh and shit: this utterance expresses surprise. The utterance as a whole can be taken as expressing doubt about the speaker's own prior knowledge, i.e. that the friend was banned, which does not fit with what he is seeing. In sum, I swear indicates incongruence between epistemicity and evidentiality: the speaker had a high degree of belief in one state of affairs, but new evidence suggests this knowledge to be unreliable. In this respect, I swear can be seen as part of a confirmation-seeking statement (Prieto & Borràs-Comes Reference Prieto and Borràs-Comes2018).

(2) CB: oh shit Sami >>I ↑swear you're << ↓banned

Example (3) also shows I swear being treated as part of a confirmation-seeking statement. After Lucy has uttered line 2, Jessica's response offers Jessica's own knowledge on the matter. Lucy has been explaining how Islam's teachings are contradictory to her own religious faith, Catholicism. Lucy utters the second intonational unit in line 1 with a high-rising terminal (Britain Reference Britain1992; Fletcher & Harrington Reference Fletcher and Harrington2001; Levon Reference Levon2016). In line 1, Lucy presents information that may be new to her recipients. Lucy expresses a lower degree of belief in her next statement, Muslims believe in more than one god: she utters this statement with a slight rise/continuing intonation as opposed to final intonation; after a pause, she follows it with I think.

(3)

Finally, in example (4), I swear co-occurs with innit, which in this instance appears to be used as a canonical neg-tag (Pichler Reference Pichler2016b). That Khadir's proposition they moved contradicts knowledge that has been proposed prior to this in the discourse is indicated by the particle though. There is a micropause in-between though and innit, such that innit can be seen as a turn increment (Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003: 30). The preferred response is confirmation, yet there is initially a pause of more than half a second, then Ali replies nah (line 2). Khadir reformulates the first pair part, which again includes the base proposition they moved, but this time, there are two items in the left periphery, I thought and the hearsay evidential you said, and on the proposition they moved there is a rising contour.

(4)

In contrast to (I) swear, uses of swear down were only found to increase speaker commitment, not decrease it, as is the case in examples from the MLE corpus (see Oxbury Reference Oxbury2021). In the current data, most of these involve the speaker managing others’ perception of themself or saving face in some way. In example (5), Tariq, Sami and the interviewer are discussing men's and women's roles in marriage. Tariq is apparently managing others’ perception of himself and trying to convince others that he is not sexist. Swear down here co-occurs with two other devices associated with emphasis: increased loudness in line 2, and repetition (of the statement I'm not being sexist). This accords with the use of swear down in the MLE corpus, which often appears in what might be described as ‘sensational news’ stories (Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2015), with speakers using the device to exaggerate particular aspects of their stories.

(5)

Other instances of swear down in our data functioned as news-marking response tokens similar to really or oh, inviting continuation by the previous speaker (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2003). Swear down often gets used when the interlocutor is in a position of greater knowledge than the speaker. In example (6), a group of boys have been talking about creative locations for shooting a music video. Raphael is talking about a place that he apparently heard Ben and another friend talking about as a potentially relevant location for shooting a video. Ben begins to explain where he means in line 1; Kai self-selects as respondent by back-channelling in line 2, suggesting that Ben has been addressing this explanation specifically to Kai. When Ben pauses at the end of line 1, Kai expresses interest by asking where, and Ben overlaps with Kai in his reply. At this point, line 5, Kai uses swear down for the first time. Both times that Kai utters swear down, it is in rapid speech and with question intonation.

Challenging epistemic status, however, is not prioritised as a meaning of swear down in this instance. Rather, it appears to be marking new information in what Ben has said – in the second instance, at line 12, swear down co-occurs with the change-of-state token oh (Heritage Reference Heritage, Maxwell Atkinson and Heritage1984). Both times, Ben treats Kai's use of swear down as an invitation to keep the floor and carry on telling. At line 6, Ben acknowledges the preceding turn with yeah (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2016). He then continues you see where um:, i.e. giving Kai more information to help him locate this house within the local area. Kai's swear down appears not to be interpreted by Ben as casting doubt on Ben's previous turn, but as a request for more information and/or an invitation to continue his telling. Indeed, Ben carries on supplying information that is relevant to Kai's direct question where in line 16. Both instances of swear down occur at a transition relevance place (TRP) and appear to act as an invitation to carry on holding the floor. Both instances occur after a brief but maximally informative and discourse-new utterance from Ben: west [place] in the first instance, and right next to it in the second.

(6)

Example (7) is slightly different in that the speaker who uses swear down is addressing an uninformative recipient. As in example (6), however, swear down is used here immediately after some requested information has been given: Omar asks where Sqara got his hair cut in line 1, and Sqara gives the relevant answer in line 2. Omar responds with swear down in line 4. Omar's use of swear down is not treated by Sqara as an invitation to tell more. This could possibly be because Omar's use of swear down does not have the question intonation that Kai uses in example (6). Omar follows his turn in line 4 with an information-seeking question; he does not leave any pause for Sqara to respond, so it may be that he also perceives his use of swear down as not mandating any explicit response.

(7)

No comparable tokens of swear down were found in the MLE corpus, in which swear down mostly occurs with the first-person pronoun I, and is generally in a declarative/narrative context, although swear is used with question intonation in the MLE corpus.

Two further related phrases were found, with the same functions, in both the current data and the MLE corpus, namely on X's life, a contraction of I swear on X's life, and I swear to God. On my mum's life/mother's life can show high speaker commitment. It gets used to contribute force to threats, as in example (8). On X's life also gets used when one party's past or future actions are at issue. For example, in example (9), Chantelle uses mother's life when attempting to persuade a youth worker that someone has cheated at pool by picking up the white ball.

(8) CB: On my mum's life Ima fuck you up

(9) Chantelle: mother's life he did, he picked up the white ball (ennit)

I swear to God, which would be the closest to the literal translation of wallah(i) into English in the data, appears infrequently in both datasets – there are only two tokens in the current data. Intriguingly, the most frequent user in the MLE corpus is a Somali teenager. In his interview, he and his friend have been talking about how they are afraid of going to Camden because of the Somalian boys up there. Omar tells a story about how he was once confronted by a man or boy in Camden in example (10). This form was also found in the 2019 Hackney data, along with I swear on the Holy Bible.

(10) Omar: the trust me man they're not just like they're not just Somalian they just a lot of our people [David: I know bruv] as well . but . you thinking like . I was Somalian I was never be hold by Somalian people cos I I am Somalian I look Somalian . but the thing was . I was just there .. I was just walking I swear to god I was just going to see my grandma … and all I find out all of a sudden it just all I find out was just someone kicked my bag and I was . as I looked back .. xxx just bigger than me like .. (MLE corpus; example from Oxbury Reference Oxbury2021)

5.2 Wallah

As found by Quist (Reference Quist2008) and Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009) in Danish and Norwegian respectively, the use of wallah(i) in our data can be understood as indexing high commitment by the speaker to their utterance. Example (11) shows wallah being used when the truth status of an utterance is challenged: Lola offers a story preface in lines 1–3 and Khadir challenges the truth of this story in a ‘bald on record’ way (Brown & Levinson Reference Brown and Levinson1987) by saying you're lying (line 5). Lola repeats her utterance from line 3 verbatim but prefaces it with wallah. Given that the only lexical difference between lines 3 and 6 is wallah, wallah may be seen as indexing epistemic stance and upgrading the truth status of the proposition in line 6.

(11)

Wallah is also known in other languages to serve interpersonal and discourse-structuring functions. Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2015) describes sensational news stories as being collaborative events: the events of the story will be highly implausible, and recipients must agree to suspend disbelief and give the speaker the floor for the duration of the telling. Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2015) gives examples of narratives that appear to be structured by I swear phrases, used at particular moments in the telling as stand-alone intonational phrases (IPs), maintaining the narrator's stance towards the story of the whole narrative, and justifying the newsworthiness and tellability of the events. Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2015) suggests that this means that at another level, wallah(i) acts as an index of genre, i.e. of the sensational news genre..

In example (12), Ali is recounting a time he once got arrested for climbing the scaffolding on the local town hall. Ali's utterances of wallahi show the overlap between wallah as discourse- and narrative-structuring, and wallah as used when the epistemic status of what the speaker has just said has been challenged (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009). The telling of Ali's story is both collaborative and combative at the same time.

To put this story in context, Khadir, Amanda and Lola (who are also present) have spent much of the interview teasing Ali, and he complies with the role they assign him. In an earlier narrative, the friends recount how when Ali first moved to the area, some other teenagers stole his sliders from his feet. In the current narrative, Ali presents himself in a more serious light. Amanda deflates some of the drama of the narrative by revealing that while Ali got arrested, his friend escaped (line 1). Ali needs to both hold the floor and complete telling his story, and also maintain face against his friends’ alternative version of events.

The moments at which Ali uses wallah are moments of high drama, and also moments when Ali's control over the floor and over his narration are threatened. Partway through the story, at line 1, Amanda teases Ali, saying so you let him go and let yourself get bagged? With his narrative and self-portrayal under threat, Ali uses wallah(i). Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2015) has described how in the telling of ‘sensational news stories’, two worlds are important: the world of the telling, in which the speaker is animator, author and principal simultaneously (Goffman Reference Goffman1981); and the story-world, in which the speaker is usually the main character. Ali's status at this point as both animator and author of his story, and as the central character in that narrative, is being threatened.

Ali's use of wallah(i) at line 6 can be seen as ‘attention getting’ (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2016) and also as intensifying (cf. Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009) in so far as it marks a moment of high drama in the story: events had become so scary that Diego was crying. This means that wallah is also showing high speaker commitment and attesting to the reliability of the speaker's version of events: Amanda has hinted at an alternative story in which Diego manages to get away, but Ali is not quick enough to escape; Ali's account, that Diego was scared, contradicts his friends’ version of events and wallah(i) perhaps prepares his recipients for an implausible turn in the story. This is indeed in line with Lehtonen's (Reference Lehtonen2015) description of wallah(i).

After his first use of wallah(i), Ali is able to carry on his story uninterrupted for the duration of lines 8–22. At line 22 there is a potential transition relevance place (TRP) and Amanda and Khadir both laugh – general extenders can signal the end of a turn (Cheshire Reference Cheshire2007). Ali again says wallah(i) and continues on the same topic. Similarly, at line 30, Ali reveals that he was caught by a dog, which appears to be met with disbelief by Khadir in line 31, and as Khadir starts laughing (line 32), Ali again says wallah before continuing. Both of these latter two instances of wallah are dialogic: they appear at moments when other speakers might be about to take the floor, and signal that there may be more of the story to come; they highlight particular moments in the story as being particularly dramatic, while also looking ahead to recipients’ potential disbelief in these moments. Khadir's responses in lines 24 and 31–32 are also in line with Lehtonen's (Reference Lehtonen2015) claim that wallah(i) indexes a narrative genre: Khadir's response weakly expresses disbelief in line 31, but his laughter and Amanda's in lines 23–24 show affiliation with the telling. It seems that what is wanted by the group of friends is a sensational story, and Ali's wallah indicates to the others that he is about to provide sensational news.

(12)

5.3 Say-phrases: say mum's, say wallah, say swear

A range of different functions were identified for the related set of phrases we are calling say-phrases. The semantic meaning of any of the phrases with say appears to be telling someone to swear the truth of something. This can be seen in example (13). Ahmed asks twice, in lines 1 and 3, where's the rizla?. Ahmed's reaction in line 7 when he finds out that CB does not have the rizla (cigarette) papers suggests that he was expecting CB to have the rizla. Ahmed's response to CB in line 4 is indeterminate between showing disbelief, i.e. challenging CB to tell the truth, and asking CB for confirmation of what he has just said, which he then gives in line 5. This use of say mums could be glossed as ‘Is it true?’ or ‘really?’, similar to how Quist (Reference Quist2008: 47) interprets Wallah? in Copenhagen multiethnolect. This extract also shows the co-occurrence of say mums with on my mum's life and say on my mum's life (line 7).

(13)

In a similar manner to swear down, say wallah can function as a news-marking response token. In example (14), Ibrahim and Omar have been explaining local postcode wars to the interviewer; a postcode war is a potentially violent rivalry between adolescents in different areas of the city. Omar says that one local gang got (killed) a person known to both Ibrahim and Omar. Ibrahim treats this as newsworthy by uttering say wallah with weakly rising intonation. Omar treats this as an invitation to continue in his next turn, he continues the topic and adds the additional information they're the ones that got me as well.

(14)

Similarly, example (15) shows say wallah being used when a potential story preface has been given. Both Sqara and Ahmed interpret the interviewer's question in line 1 as fishing for a story, with both casting around for a story to tell. Sqara's eventual answer in line 5, it was a dare, is a potential story preface. The interviewer's repetition of a dare at line 6, with weakly rising intonation, constitutes an invitation to continue. However, Sqara gives the minimal response yeah in line 7, which appears to be dispreferred. Ahmed indexes affiliation with two quiet laughter particles, but does not take the floor, while the interviewer replies okay, both conceding the floor to Sqara. Ahmed then says say wallah and Sqara replies wallah, and after a pause of almost one second, Ahmed in lines 12 and 14 gives his own story preface: he began smoking by smoking shisha. Ahmed's say wallah may be a simultaneously affiliative and more forceful invitation to Sqara to tell his narrative. Sqara replies wallah; this seems to be intended by Sqara as sequence closing, but is not necessarily treated as such by Ahmed, because a pause of 0.85 seconds follows. Then Ahmed self-selects but indicates a small topic shift by prefacing his turn with me, showing that the focus will be on him rather than on Sqara, and gives the preface to his own story.

(15)

The use of say wallah/wallah as an adjacency pair frequently functions as a sequence-closing act; this function has been described by Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009) as ‘routine practice’ (although see Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2015 on the use of adjacency pairs as an interactional ritual in Finnish). The sequence-closing function of wallah contrasts with the response-token function; the latter invites the speaker to continue the topic, while the former closes the topic.

In example (16) (partially repeated from example (4)), Khadir and Ali's use of say wallah and wallah in lines 9–10 appears to be an adjacency pair. Ali's immediate response of wallah, with some emphasis, in line 10 seems very close to what Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009: 229) describes – ‘an automatic minimal response’. This adjacency pair in lines 9–10 bookends the interaction and could even be said to be a framing device. After line 10, there is a pause and then the interviewer asks a follow-up question: as far as Ali and Khadir are concerned, the say wallah/wallah adjacency pair seems to have put the current interactional frame to bed. The interaction involves no obligations between participants: Ali has just provided a clarification, at request Khadir's request, about where a particular family known to both boys now lives. Once the clarification has been provided, the say wallah/wallah pair seems to mark the clarification activity as completed. After this extract finishes, there is a pause, and then the interviewer asks another question.

(16)

Returning to uses of say-phrases that invite response, such phrases can also attach to a proposition at the left periphery in order to request clarification on some specific piece of information. In example (17), Tariq uses say on mum's life to successfully initiate repair. The two boys have been talking about a racist incident they recently experienced. After Tariq has explained that most White people who have Black friends have permission to use the N-word, Sami contradicts him in line 1, saying he has never had permission. In line 2, Tariq uses say on mum's life at the left periphery, in such a way that the phrase appears to scope over the rest of his utterance. Even without say on mum's life at the left periphery, Tariq's partial repetition in line 2 of Sami's utterance in line 1 has the format of a ‘repeat’ or ‘understanding check’ type of other-initiated repair (Sidnell Reference Sidnell2010: 117). Yet Sami begins his next utterance in line 3 with on my mother's life, spoken with emphasis, suggesting that the epistemic phrase mum's life is treated as important by Sami. Sami then begins repeating his utterance from line 1 but stops and self-repairs, and a clarification sequence takes place.

(17)

From example (17), it was suggested that say wallah/mum's/swear can preface a clarification request and can scope over the proposition about which there is doubt. This is also the case in example (18), where say wallah is used to preface an ‘understanding check’ type of repair (Sidnell Reference Sidnell2010: 118). After hearing that Sqara's haircut cost ten pounds in line 1, Omar and Ibrahim seek clarification as to whether he got the haircut at eagle's or legal's, a likely misunderstanding of the name. After getting no response, Ibrahim then uses say wallah at the left periphery of an ‘understanding check’ type of other-initiated repair. Say wallah scopes over the proposition [that haircut cost] ten pound from eagle's.

(18)

5.4 Summary

To briefly summarise the data presented in this section, several of the swear-phrases identified in our data are highly multifunctional. Wallah, for example, can signal high commitment, sensational storytelling and sequence closing. These different functions can only be derived via an understanding of the linguistic context in which the form is used (Wiltschko et al. Reference Wiltschko, Denis and D'Arcy2018). In (11), only by viewing Lola's use of wallah in the wider discourse (and social) context can its function be understood as discourse-structuring. Similarly, only by considering the syntactic context of Ibrahim's use of say wallah at the left periphery, as well as the discourse context of interactional misunderstanding, can the function of say wallah in (18) be understood as a repair initiation. Finally, Ibrahim's use of say wallah in (14) can be differentiated from the use of the same form in (18) by analysing the use of weakly rising intonation, which indicates its function as a news-marking response. The functions of these swear-phrases are, therefore, predictable to a degree using such a qualitative analysis that includes information from other linguistic domains.

6 Discussion and conclusions

There are two important points of comparison that we can now return to in light of the data presented in the preceding two sections. The first is between our own data, collected in West London, and that of similar studies, which collected data on discourse-pragmatic variation in East London, namely the MLE corpus and the 2019 Hackney data. A number of commonalities were found, including the use in both areas of I swear, swear, swear down, on X life, I swear to god and say swear. In our data, they are used to varying degrees by participants of multiple ethnicities, suggesting that swear-phrases are a feature of the broader speech style of London adolescents. This isn't to say that such phrases are unique to London-based adolescents, however. Rather, they are likely to be a feature of youth vernaculars more generally.

On the other hand, a point of contrast between West and East London datasets is an absence in the East London data of Arabic-derived swear-phrases, including wallah(i) and say wallah, as well as the English phrases say on mum's life and its abbreviation, say mum's. Our data therefore represents the first in-depth analysis of wallah and related phrases in the speech of British adolescents. A functional contrast was also found in our data with respect to the previously attested English swear-phrases. While swear down can be seen in the MLE corpus as signalling high commitment, data from West London suggests it can also be used as a news-marking response token that invites continuation by the previous speaker (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2003).

The second point of comparison is between our data and that of other researchers who have found occurrences of wallah and related phrases in multiethnolects in other countries. As was also found in both Danish (Quist Reference Quist2008) and Norwegian (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009), uses of wallah in our data often serve to index high commitment on behalf of the speaker. As Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2015) also finds in Finnish, we observe that wallah can index a narrative genre associated with sensational stories. Finally, we observe parallels between the use of the adjacency pair say wallah/wallah as a routinised sequence-closing act in our data and the use of an equivalent pair in Danish data collected by Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009). There therefore appears to be some consistency with respect to how Arabic-derived epistemic phrases come to function in the speech of adolescents in urban centres. It may be that those languages in which wallah and related phrases have arisen lack an equivalent discourse-pragmatic feature with the same functions.

While our study shows remarkable similarities in the functional use of wallah in English in Ealing compared to in other European languages, the difference is in the stylistic status of wallah and who uses it. Both Quist (Reference Quist2008) and Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009) report the use of wallah by non-Muslim identifying adolescents in Denmark and Norway respectively. This is not the case in our data, with wallah and say wallah exclusively used by Muslim-identifying adolescents or adolescents of Muslim heritage. Phrases like swear and swear down seem to be used by all speakers; again, they are unlikely to be unique to London, but rather, a feature of adolescent speech in general. By contrast, on current evidence, Arabic-derived swear-phrases appear to be ethnically stratified.

In truth, however, the salient dimension in the data is some combination of religion and ethnicity, two undoubtedly related categories. What the users of wallah and say wallah have in common is that they either identified as Muslim or had parents that did. Previous work in East London by Fox (Reference Fox, Llamas and Watt2010) has suggested a degree of indirect influence of Muslim identity on sociophonetic variation in MLE. Fox observes a relationship between the social practices engaged in by her participants – in relation to drugs, car crime and anti-social behaviour – and their production of PRICE and FACE vowels, with participants engaged in these practices more likely to use the [ɐɪ] and [ɛɪ] variants, respectively. For some participants, aligning themselves strongly with their Muslim identities goes hand-in-hand with rejecting this subculture associated with street-related social practices, leading to an avoidance of those variants.

The effect in our data is more direct and is categorical. There is a complete absence of tokens of wallah by non-Arab and non-Muslim-identifying participants. This is perhaps unsurprising given that (a) we are dealing with a complete lexical item, rather than a gradient acoustic property, and (b) the lexical item in question is demonstrably linked to a particular religion, namely Islam, rather than the type of indirect relationship between a sociolinguistic variant and a religious identity described by Fox (Reference Fox, Llamas and Watt2010).

The different statuses of wallah in UK data, on the one hand, and Scandinavian data (Quist Reference Quist2008; Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009), on the other, may reflect the status of Muslims in those parts of the world and their respective influence on their contemporary youth cultures of those places. While elements of Jamaican/Caribbean cultures have long been influential on British youth cultures (Jones Reference Jones1988), perhaps reflected in the strong presence of Jamaican/Caribbean linguistic features identified in MLE, the same cannot be said of Arab/Muslim cultures. In contrast, Muslims in the UK have a history of being portrayed as uncivilised, religious fanatics (Shaheen Reference Shaheen2003), in direct opposition to Western culture (see Ahmed & Matthes Reference Ahmed and Matthes2017 for a meta-analysis). This might explain a reluctance on behalf of non-Arab adolescents to align themselves with Muslim culture through the use of phrases like wallah. Evidently, this is not the case for the small portion of non-Muslim users of wallah identified in Copenhagen (Quist Reference Quist2008) and Oslo (Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009), respectively.

Returning to the bigger picture, namely the particular relevance of epistemic markers to adolescents, we are cautious not to overstate the significance of our findings. Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009) suggests that as wallah rose to shibboleth status in Norwegian, this led to the innovation of an entire epistemic style in Norwegian teenage speech that included Norwegian phrases with similar semantic meanings (including jeg sverger ‘I swear’ and helt ærlig ‘quite honestly’); this style, she suggests, is characterised by an array of different epistemic discourse markers. We need to be careful in drawing conclusions built on such notions of causality, however, when talking about a significant relevance of epistemicity to a particular age cohort. We agree with Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2015: 181) when she states, ‘I would not seek an explanation that epistemicity as such should be more central to interaction among young people or multiethnic youth than it is in other people's discussions’ (translation by Google). Our dataset, like that of Opsahl (Reference Opsahl2009), has the drawback of offering only a synchronic snapshot of language.

Given the coexistence and seeming prominence of epistemic phrases in adolescent speech in urban centres across Europe (Quist Reference Quist2008; Opsahl Reference Opsahl2009; Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2015), however, we might be inclined to argue that teenagers will inevitably be looking for ways to take and hold the conversational floor, claim attention for what they are about to say, make their narratives maximally sensational and intensify expressions of their beliefs (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2016). In the social ‘hothouse’ that is adolescence (Eckert Reference Eckert1989), young people have a distinct need to convey their social identities via opinions and stories about themselves and others. In a situation of indirect language contact, such as in multicultural urban centres like London, they simply have more resources available to use for these functions, potentially leading to the type of linguistic innovation that has been seen as central to the study of adolescent speech.

Appendix

A. Deerpark participants

Table A1. Information on Deerpark participants. Residence: [1] = same postcode as the youth centre; [2] = Northwest London; [3] = London but outside Northwest London. Empty cells = information not given

B. Interview data – raw and normalised frequencies

Table A2. Participants’ total word counts in the interview data and normalised frequency of each epistemic phrase per thousand words, with raw token numbers in brackets

C. Self-recorded data – raw and normalised frequencies

Table A3. Participants’ total word counts in the self-recorded data and normalised frequency of each epistemic phrase per thousand words, with raw token numbers

D. Transcription conventions