1 Introduction

The use of more than one modal auxiliary within a single verbal phrase (e.g. I might could do that or you will can help me) is a syntactic feature of non-standard English varieties in the British Isles, North America and elsewhere. Although double modals have been widely studied in the past seventy years, questions remain as to their syntactic behavior, semantics and history, as well as to the pragmatic contexts that favor their use, the inventory of possible double modal types and their geographic distribution in different English varieties. Double modals are of theoretical interest as they represent micro-syntactic variation that may shed light on the status of the verbal phrase: although several proposals have been made as to the constituency relations and phrase structure of double modal constructions (Boertien Reference Boertien, Montgomery and Bailey1986; Battistella Reference Battistella1995; Hasty Reference Hasty2012; see also Morin et al. Reference Morin, Desagulier and Grieve2020 for a discussion of double modals from the perspective of Construction Grammar), their ultimate status has not yet been conclusively resolved, and the semantic status of some double modals remains unclear. Pragmatically, most double modal types have been proposed to be restricted to specific contexts: they are used for ‘the negotiation of a speaker's wants or needs’ in polite, cautious conversation in order to mitigate face-threatening situations (Mishoe & Montgomery Reference Mishoe and Montgomery1994: 12; see also Montgomery Reference Montgomery, Montgomery and Nunnally1998; Schneider Reference Schneider2005; Hasty Reference Hasty2015).

The feature can also be adduced as evidence for different postulates about the evolution of English syntax (Nagle Reference Nagle, Aertsen and Jeffers1993; Fennell & Butters Reference Fennell, Butters and Schneider1996; Coupé & van Kemenade Reference Coupé, van Kemenade, Crisma and Longobardi2009): either as a fossilized relic of two-verb constructions, predating the grammaticalization of modals from full lexical verbs to auxiliaries, or as a feature that emerges as a result of grammaticalization in the Middle English period. Despite their status as a nonpareil object of theoretical interest, the inventory of possible double modal combinations and the extent of their use in regional varieties of English have not been well established by empirical studies. The feature is known to occur in speech in Scotland and northern England, and, to some extent, in Northern Ireland, but inventories of double modals differ between Southern US English and British Isles English varieties, a fact which poses challenges for a theory of simple transmission of the feature to Southern American English by Scots-Irish settlers (Schneider Reference Schneider2005; Zullo et al. Reference Zullo, Pfenninger and Schreier2021). Information about the feature's use in the Irish Republic is limited, and it has been little studied in the English Midlands, southern England or in Wales. Double modals have not been a focus of most previous studies of the dialect syntax of British Isles varieties of English based on corpus materials (e.g. Hernández, Kolbe & Schulz Reference Hernández, Kolbe and Schulz2011; Szmrecsanyi Reference Szmrecsanyi2013).

A principal difficulty in studying double modals in spoken English is their infrequency: like many syntactic features, they occur only rarely in spontaneous speech, even in varieties in which they are known to be used, and may also be subject to specific pragmatic constraints such as those noted above. The rareness of the feature means that much of the data in studies of double modals from the United States and from the British Isles consists of responses to acceptability judgment survey items or forms elicited in the context of interviews. In the UK and Ireland, double modal usage has been surveyed in northern England (McDonald & Beal Reference McDonald and Beal1987), Scotland (Brown & Millar Reference Brown and Millar1980; Miller & Brown Reference Miller and Brown1982; Brown Reference Brown, Trudgill and Chambers1991; Bour Reference Bour2014, Reference Bour2015; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Adger, Aitken, Heycock, Jamieson and Thoms2019: Morin Reference Morin, Baranzini and Saussure2021b) and Ireland (Montgomery & Nagle Reference Montgomery and Nagle1994; Montgomery Reference Montgomery2006; Hickey Reference Hickey2007), but only a few double modals are attested in corpora of transcribed speech (Beal Reference Beal2004: 127; Szmrecsanyi Reference Szmrecsanyi2013: 37), and recorded examples of naturalistic use are rare: for example, Brown & Millar report one recorded instance from interviews conducted in Scotland in the 1970s in the context of a project investigating modality (Reference Brown and Millar1980: 122), and the Scots Syntax Atlas (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Adger, Aitken, Heycock, Jamieson and Thoms2019) provides a single naturalistic recorded example.

Commenting on the data for northern England, Beal remarks that there are ‘huge gaps in the geographical coverage, which need to be filled by the collection of new data from cities such as Carlisle, Lancaster, Liverpool and Manchester, and the processing of data already collected elsewhere’ (Reference Beal2004: 139). The same could be said for other areas of England, for Ireland, for much of Scotland and for Wales.

This study attempts to provide a starting point for further research into double modal usage in the British Isles by documenting their naturalistic use in the Corpus of British Isles Spoken English (CoBISE; Coats Reference Coats, Berglund, Mela and Zwart2022b, Reference Coats, Busse, Dumrukcic and Kleiber2023), a collection of geolocated Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) transcripts of recordings uploaded to the channels of local government bodies in the UK and Ireland. The study assesses which double modal forms are in use in contemporary speech in council meetings in the UK and Ireland and assigns them to locations based on corpus metadata, using methods similar to those presented in Coats (Reference Coats2022a) for North America. The rest of the article is organized as follows: in the next section, a brief overview of some previous work on double modals in Britain and Ireland is provided, focusing primarily on the geographical distribution of the feature and the inventory of attested types. Section 3 describes the data for the study, from CoBISE, and the procedure used to identify two-modal sequences in the corpus and distinguish authentic double modals from various kinds of false positives. Section 4 presents the results for England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic in terms of frequencies of double modal types; exploratory maps showing frequency count, relative frequencies and a local autocorrelation statistic are also presented. In section 5, the findings are discussed and a preliminary interpretation undertaken; several caveats are noted. Section 6 summarizes the study and suggests some directions for future research.

2 Previous work

2.1 Scotland and northern England

A few older dialectological works document use of double modals in Scotland and England. Murray (Reference Murray1873) notes the forms will can and will ought. Wright's Dialect Dictionary (1898–1905) remarks on regional use of will can/’ll can in southern Scotland and northern England and wouldn't could in northern England (I: 502). Used to could (and phonetic variants) is attested by Wright in northern England and the Midlands, as well as in Oxfordshire, but not in Scotland (I: 502; VI: 333). Should ought and shouldn't ought are attested in Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire (IV: 365, V: 350). Double modal types with may or might, common in America, are not attested by Wright.

Brown & Millar (Reference Brown and Millar1980) report use of the double modal forms will can and will no can by an informant and provide the results of a survey of university students from Edinburgh: 86 percent of students were familiar with he'll no can, 35 percent with will can and 9 percent with the question form will he no can? (Reference Brown and Millar1980: 121). At least one informant had heard or used would could, used to could, might could or should ought to, but only the type won't can was used spontaneously in a recorded interview (Reference Brown and Millar1980: 122). Miller & Brown report that in Scotland, ‘only will and might can be the first member [of a double modal]’; in terms of frequency, will can is reported to be ‘very common’ in speech and might could ‘increasingly common’ (Reference Miller and Brown1982: 13). The forms might can, might should and might would are also attested.

Brown (Reference Brown, Trudgill and Chambers1991) reports on double modal usage in Hawick, Scotland: in addition to the forms listed by Brown & Millar (Reference Brown and Millar1980), the types should can, must can, should could, would could and must could are attested; would can and will could are reported to be possible. According to Brown, double modals exhibit tense congruency (i.e. will can or would could are possible, but not will could or would can) (Reference Brown, Trudgill and Chambers1991: 97). It is not clear if the large number of examples provided by Brown represent naturalistic usages or are constructed sentences based on expert knowledge.

Miller reports the forms ’ll can, might could, might can, would could, might should and might would to be used in Scotland (Reference Miller2004: 53). Melchers finds ’ll no can in Orkney (Reference Melchers2004: 40). Bour (Reference Bour2014, Reference Bour2015) reports on a survey-based investigation of double modals in the Scottish Borders region. In addition to previously reported forms such as will can, should can, would can and should could, some informants were familiar with non-canonical types such as may not could, may can, should ought to and mustn't could have (Reference Bour2015: 55–6). A survey conducted in Hawick by Morin (Reference Morin, Baranzini and Saussure2021b) found might can to have the highest rate of self-reported usage; may could and may should, not attested in most previous literature, were also familiar to some respondents.

Informants for the Scots Syntax Atlas (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Adger, Aitken, Heycock, Jamieson and Thoms2019)Footnote 2 rated their own use of seven short sentences containing double modals from 1 (‘I would never say that’) to 5 (‘I would definitely say that’).Footnote 3 Responses show that double modals are not commonly used, but are more frequent in the Scottish Borders region and in Dumfries and Galloway, compared to other parts of Scotland. In contrast to previous literature in which will can is reported to be the most common Scottish double modal type, the sentence with must can shows the highest average value in the survey. As far as corpus data are concerned, according to Corbett, no double modals are recorded in the spoken portion of the Scottish Corpus of Texts and Speech (Reference Corbett and Lawson2014: 270).Footnote 4

In northern England, double modals are used in Newcastle and Tyneside. McDonald & Beal report the forms might can, must can, will can, might could, must could and would could to be possible (Reference McDonald and Beal1987: 47). Studies based on acceptability judgments and self-reports of use suggest that use of the feature is in decline in Northumberland (Beal Reference Beal2004: 128). Fifteen percent of informants surveyed from the north of County Durham rated sentences containing double modals to be acceptable (McDonald Reference McDonald1981, as cited in Beal Reference Beal2004: 128). A survey of young people conducted in Northumberland found less than 10 percent of teenagers considered double modals to be acceptable (Beal Reference Beal2010: 38).

The feature is not well attested in corpora of northern English speech. A single double modal (wouldn't could) was recorded in a corpus of 300,000 words of transcribed speech collected in the 1970s from Tyneside and rural environs (McDonald & Beal Reference McDonald and Beal1987: 47). In the Newcastle Corpus of Tyneside English (NECTE; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Beal, Corrigan, Maguire, Moisl, Beal, Corrigan and Moisl2007), a 440,000-word corpus of interview transcripts from the 1960s–70s and the 1990s, one double modal is recorded (you'll probably not can remember; Beal Reference Beal2004: 127). No additional double modals can be found in the data for the updated version of the corpus, the Diachronic Electronic Corpus of Tyneside English (DECTE; Corrigan et al. Reference Corrigan, Buchstaller, Mearns and Moisl2012).

2.2 Ireland

Compared to Scotland and northern England, double modals are less extensively attested in Ireland. They are found mainly in speech from Northern Ireland, where they were brought by northern English and Scottish settlers at the time of the Ulster Plantation beginning in the seventeenth century (Montgomery & Nagle Reference Montgomery and Nagle1994; Hickey Reference Hickey2007; Corrigan Reference Corrigan2011). Gregg attests use of I'll no can stay in Ulster Scots (Reference Gregg and Wakelin1972: 131), and Montgomery & Nagle report the types might could, might should, should ought to, used to could, used to would and will can to be in use in Ulster English in the 1990s (Reference Montgomery and Nagle1994: 102). An informal survey of twenty informants from Belfast and County Antrim conducted in 1990 and 1991 showed that a few respondents were familiar with might could, might can and will can, but not with other double modal types (ibid.). Corrigan found no double modals in a 52,000-word database of transcribed personal narratives collected in the mid twentieth century in South Armagh, Northern Ireland (Reference Corrigan2000: 27). Hickey (Reference Hickey2007) found no naturalistic uses of double modals in recordings made from the 1980s to the 2000s in the Republic of Ireland, mainly in Dublin and Waterford. The Survey of Irish English Usage found that 7 percent of informants rated the sentence He might could come after all to be ‘no problem’ (Hickey Reference Hickey2004: 191).Footnote 5 Hickey remarks that double modals seem to be a feature that has been retained in North America, but which has ‘receded in Britain and Ireland’ (Reference Hickey2007: 391). A search for double modals in the ICE-Ireland corpus (Kallen & Kirk Reference Kallen and Kirk2007) returned one result, in a transcript from the category ‘broadcast discussions’ from Northern Ireland: I mean we'll may get into it in a moment or two. The codes in the corpus identify the speaker as an older male from County Down in Ulster.

2.3 Midlands, southern England and Wales

Except for the attestations of used to could in Wright (Reference Wright1898–1905) noted above, few double modal forms have been attested in speech from the Midlands, southern England or Wales. The sampler of the Freiburg English Dialects Corpus (Szmrecsanyi & Hernández Reference Szmrecsanyi and Hernández2007), a subset of the FRED corpus (Hernández Reference Hernández2006; Anderwald & Wagner Reference Anderwald and Wagner2007), contains a few double modals, including would could, would used to, used to might and used to could, from the Midlands and the southwest of England, regions whose dialects have not previously been reported to be associated with double modals.Footnote 6 As far as is known, the feature has not been attested in Welsh English (e.g. in Filppula Reference Filppula2004; Penhallurick Reference Penhallurick2004; Paulasto Reference Paulasto2006; Paulasto et al. Reference Paulasto, Penhallurick and Jones2020).

Many of the double modal usages reported in the studies above are included in the Multimo resource (Reed & Montgomery Reference Reed and Montgomery2016),Footnote 7 an online table that includes contextual information such as location, medium, sentence context and other details, if available. Multimo lists 168 double modal instances from England or Scotland. A number of these are from literary texts dating from the thirteenth to the twentieth century; the spoken attestations are mostly from the sources noted above as well as from personal communications to the resource's creators. Multimo does not include any entries that have been tagged with the locations Wales, Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland.

Morin et al. (Reference Morin, Desagulier and Grieve2020) and Morin (Reference Morin2021a) point out that double modals can be found in corpora collected from UK web texts and suggest looking for the feature in social media texts from Britain.

Overall, the data on double modal use in Britain and Ireland are heterogeneous: some types have been more systematically documented, especially in Scotland, but for the most part, the range of possible combinatorial types has not been extensively investigated, either by written surveys, face-to-face elicitation in interviews, or documentation in corpora, and there are few examples in the literature of naturalistic usages in speech. In general, double modals have not been studied in speech from the English Midlands, southern England or Wales, either by means of surveys or in corpora.

The present study addresses two main questions: first, where are double modals used in naturalistic speech in the British Isles? Are they encountered only in northern England, Scotland and Northern Ireland, as has been suggested by previous research? Second, what combinatorial types are used, and how prevalent are they? Naturalistic spoken language data from Britain and Ireland can shed light on these questions, demonstrating that a larger number of combinatorial types are used in a wider geographical context than has previously been reported.

3 Data and methods

The main data for analysis come from the Corpus of British Isles Spoken English (CoBISE), a 112-million-token corpus of 38,680 word-timed and part-of-speech-tagged ASR transcripts from 495 YouTube channels of local councils or other local government organizations in 453 locations in England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland (Coats Reference Coats, Berglund, Mela and Zwart2022b, Reference Coats, Busse, Dumrukcic and Kleiber2023).Footnote 8 Table 1 shows the breakdown by country for the corpus in terms of number of sampled locations, number of sampled videos, and aggregate transcript length as number of words and video duration.

Table 1. CoBISE size by subcorpus

Much of the content of the corpus consists of recordings of public meetings of local councils. In a typical council meeting, councilors will discuss various agenda items pertaining to (for example) local rules and ordinances, building proposals, budget considerations and spending, and a range of other local concerns. The speech in council meetings is somewhat more formal than in other interactive contexts of daily life, but from a pragmatic perspective, council meetings abound in contexts that favor the use of double modals: councilors are engaged in the negotiation of wants and needs and must cooperate in order to achieve the work of the council. The political necessity of cooperation tends to favor careful, polite and face-preserving speech.

Although the scope of this study does not allow a description of the contexts for all occurrences of double modals in the CoBISE transcripts, an example demonstrates the sort of careful, polite interaction in which the feature occurs. In a video entitled ‘Mortlake, Barnes Common and East Sheen Community Conversation’, uploaded to the YouTube channel of the London borough of Richmond upon Thames, a local resident expresses objections to proposed changes to local building codes designed to encourage more environmentally sensitive development such as a requirement for the construction of bicycle lanes, remarking that in Brighton, this created problems for car parking. A councilor in favor of the proposed changes responds very carefully and politely,Footnote 9 stating

I think you're absolutely right, sort of taking into account all of that stuff, but do you think… where I may slightly disagree… you would might… is that I do think, you know, particularly with what we've seen over the last few weeks, with, erm, campaigners such as Greta and, erm, you know, protests happening all over the world, including Afghanistan, you know, there's climate change protests happening in Afghanistan, we do have to take this issue seriously.

This type of careful, face-preserving disagreement is relatively frequent in council meetings, and represents the kind of pragmatic context in which double modals are likely to occur. In this example, the use of two epistemic modals could represent a more careful or tentative expression of epistemic possibility compared to use of a single modal auxiliary.

Although many of the transcripts in the corpus are of meetings, the content of individual channels varies according to council practices. Local government meetings in the UK are, in general, open to the public,Footnote 10 but there is no legislation mandating that they be recorded, or that recordings be made available online. Some UK councils use their YouTube channel to make video recordings of public meetings available, but others use their channels to upload videos of local news and events, public service announcements and reminders, or information about changes in local ordinances. Many YouTube channels of local councils in the UK contain both recordings of public meetings as well as additional video content of various types.

In the Republic of Ireland, the default legal situation is different – in contrast to the UK, there is no law stipulating that meetings of local government institutions must be open to the public – only that the minutes of meetings must be accessible.Footnote 11 This difference may, in part, explain why the YouTube channels of local councils in the Republic of Ireland mostly do not include recordings of governmental meetings. As of 2019, only 4 of the 31 local councils in Ireland either broadcast meetings through a streaming service or made recordings available.Footnote 12 The shift to online meetings brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic beginning in 2020 induced a few additional Irish local councils to make live streams or recordings of council meetings available to the public via YouTube or other platforms, but most of the Irish local council channels sampled in CoBISE contain primarily other types of content. The speech recorded in CoBISE is recent: the corpus includes transcripts of videos made during the time period spanning approximately 2000–21, but most of the content consists of recordings from the years 2017–21.

One drawback of YouTube ASR transcripts is that they contain no speaker metadata: demographic categories commonly used for sociolinguistic analyses, such as gender, age, educational level or ethnic background, are thus not available to the analyst in the raw transcripts without additional annotation work. Nevertheless, the transcripts in CoBISE, which are mostly of meetings, represent a relatively large body of careful conversational discourse and negotiation from a large number locales in the British Isles. They are therefore good material for looking into the prevalence and distribution of double modals.

3.1 Corpus search

The procedure used to search for and verify double modals in CoBISE was similar to that described in Coats (Reference Coats2022a): double modals were sought in the part-of-speech-tagged and word-timed corpus using regular expressions. Starting from thirteen modal or semi-modal forms (may, might, can, could, shall, should, will, would, must, ought to, oughta, used to and the abbreviated form ’ll), a regular expression was generated for all possible two-slot combinations, with the exception of repetitions (i.e. may might, may can, may could, etc., but not may may). In order to account for potential negations, past tense constructions and question forms, the expressions also captured sequences with intervening pronouns or negators and the auxiliary forms have and ’ve, as well as adverbs ending in -ly.

A script then used the 156 regular expressions generated in this way to search for double modals in the corpus and created a table with a row for each hit and columns for the country, channel name, two-modal sequence and text captured by the regular expression from the transcript, as well as a URL linked to the corresponding video at a time three seconds before the utterance. Then, a subset of the search hits was manually inspected in the corresponding videos to check if they were double modals or false positives.

3.2 Manual verification

Manual annotation consisted of clicking on the URLs in the table described above, listening to the speech and categorizing the sequence by adding an annotation code. The search hits fall into three basic categories: false positives, self-repairs and authentic double modals. False positives were classified as ASR errors (the algorithm had incorrectly transcribed a word), overlap errors (e.g. due to the overlap of two clauses in utterances like if I might, could I… or the overlap of two speakers), homonyms or homophones (e.g. Will can help you, where Will is a name, or wood can be taken, where wood has been incorrectly transcribed as would), errors due to unintelligible audio, or instances in which the video was no longer available on YouTube.

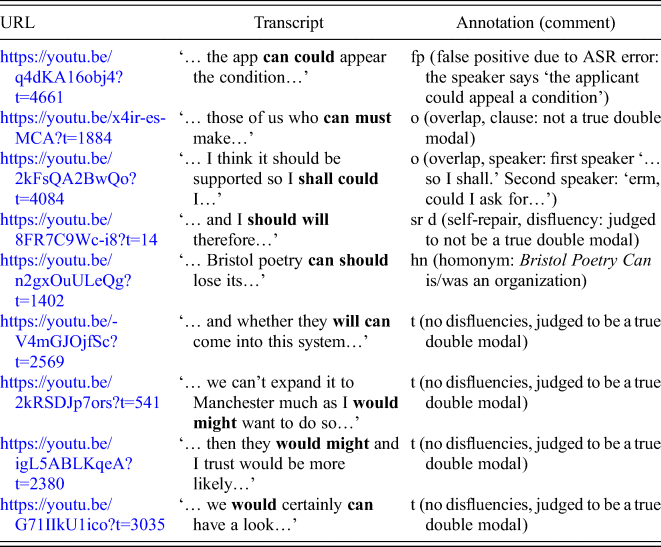

The annotation code sr (for ‘self-repair’) was applied to instances where a speaker noticeably corrected an utterance while articulating the two-modal sequence, for example, by cutting off a word prior to completion and beginning with a different modal form or by pausing noticeably between two modal forms and articulating the second form with emphasis. True double modals were identified on the basis of semantic and articulatory considerations: because corrections or self-repairs in speech are typically associated with disfluencies in terms of articulatory timing and prosody (Levelt Reference Levelt1983; Postma Reference Postma2000; Lickley Reference Lickley and Redford2015), two-modal sequences that did not fall into one of the categories described above, had no disfluencies, and were coherent in terms of semantic content and discourse context were judged to be authentic double modals. An asterisk was used to indicate authentic but questionable usages: utterances with two modals in sequence that were semantically coherent and exhibited only very slight disfluencies, such as minimal pauses. A few example annotations are provided in table 2.

Table 2. Example annotations

For additional details about the annotation scheme, see Coats (Reference Coats2022a), in which a similar procedure was employed.

The selection of videos for manual inspection was pseudo-random, but focused on videos more likely to represent authentic usages: transcripts in which two base modal forms occurred in sequence, with no intervening words. In total, 1,154 (22.5%) of the 5,119 search hits were checked and manually annotated with one or more of the codes.

4 Results

This section considers the authentic double modal combinations and their geographical distribution in the CoBISE data. In total, 187 double modal utterances in CoBISE were judged to be authentic or possibly authentic, based on the criteria noted above. This represents 16.2 percent of the utterances that were manually examined in the corresponding videos – most sequences of two modal verbs in the manually checked transcriptions were self-repairs (42.5%), overlaps (19.2%), homonyms or homophones (3.7%), ASR errors (27.6%) or video errors (1.5%).

4.1 Types by frequency

Table 3 shows the frequencies of ‘true’ double modal types in order of decreasing frequency, as well as for each type the number of search hits manually checked, the percentage of search hits manually checked, the number of hits judged to be true double modals and the percentage of checked hits judged to be true double modals. Types in boldface text are ‘non-canonical’: those not discussed (or only minimally) in the previous literature summarized above. Will and ’ll occurring as the first element in a double modal have been collapsed to a single type in tables 3–8.Footnote 13

Table 3. Double modal types

Table 4. Scotland double modal types

Table 5. England double modal types

Table 6. Wales double modal types

Table 7. Northern Ireland double modal types

Table 8. Republic of Ireland double modal types

The most frequent type in the data, somewhat surprisingly, is would might, a combination not previously commented upon in detail in reports of double modals in the British Isles. Will can (and ’ll can), known to be a traditional type in descriptions of double modals in Scotland, is the next most frequent overall, followed by will might; the next most frequent types, might may and would may, have not been discussed extensively in the existing literature. Overall, the data in table 3 suggest a tendency towards favoring double modals in which the first element is will or would, rather than types with the first-element forms might or could, which are more common in American speech.

In total, 44 different double modal types were judged to be authentic (48 if ’ll is considered distinct). The inventory of possible double modal forms in Britain and Ireland is thus considerably larger than has previously been documented: for example, Corrigan (Reference Corrigan2006) lists 10 possible double modals for the British Isles; Montgomery & Nagle list 10 distinct combinations for Scotland and 6 for Northern Ireland (Reference Montgomery and Nagle1994: 94, 104); and Brown lists 12 for Scotland (Reference Brown, Trudgill and Chambers1991: 75).Footnote 14 Even discounting hapaxes (types judged to be authentic only once), 25 combinations remain as naturalistic authentic usages, and more complete manual annotation of the 5,119 search hits in CoBISE would possibly find additional combinatorial types such as can must, attested by Brown (Reference Brown, Trudgill and Chambers1991) for Scotland but not attested among the examined search hits. The large inventory suggests that although double modals are infrequent and proscribed in standard speech, they exhibit a combinatorial propensity in the British Isles that is greater than has been previously estimated. The number of search hits is not sufficient to make robust inferences about regional patterns of use, but some tendencies can be noted.

4.2 Types by location

Of the types judged to be authentic double modal tokens, 103 were from England, 41 from Scotland, 21 from Wales, 13 from the Republic of Ireland and 9 from Northern Ireland. The manually verified data from Scotland include 25 different double modal types judged to be authentic usages (table 4). Will can is the most frequent type, followed by will might, would will and might may. Four types are attested twice, and 17 once.

The thirty distinct double modal types and their frequencies in transcripts from English channels are shown in table 5. Types with would and will or ’ll as the first element are the most common; could, can, may, must and should are also attested as the first element. Of the six forms reported to be part of the repertoire of Tyneside English (McDonald & Beal Reference McDonald and Beal1987: 47), four are attested in these data: might can, must can, will can and would could. Of the types reported in older sources, used to could and should ought, the latter is attested.

As far as is known, double modals have not previously been attested in Welsh English. Table 6 shows that the most frequent types judged to be authentic in transcripts from Wales, will/’ll can and would might, are also the most common types in Scotland and England.

Relatively few naturalistic double modals are found in transcripts from Northern Ireland (table 7): 9 were judged to be authentic usages. In addition, 8 hits in the Northern Irish subcorpus could not be examined manually because the source videos had been made private in the time between the download of the transcript material for the corpus (December 2019) and the manual verification (September 2021). The attested types have will/’ll or would as the first element; in addition, one instance of can will is attested. The Northern Ireland subcorpus is smaller than the other country-level subcorpora. More ASR transcript data from Northern Ireland may result in additional authentic double modals being found.

For the Republic of Ireland (table 8), 13 double modals were judged to be authentic or possibly authentic. The attested types are somewhat different from those found in the CoBISE data from Northern Ireland or Scotland: first-element might or would types are more common than types with will/’ll in the first position.

The text frequencies are not high enough to draw robust conclusions about local usage patterns for particular double modal types. It can, however, be noted that the more frequent types (would might, will/’ll can) seem not to be restricted to any particular region, but can be found in speech from all over the British Isles.

4.3 Corpus frequencies and maps

At country level, Scotland shows the highest overall relative frequency of double modals and England the lowest (table 9), a result in line with previous reports of the geographical distribution of the feature. The values, between 1.38 and 2.40 double modals per million words, are roughly comparable to those found for North American data, where at state/province level, relative frequencies of double modals have been found to range from zero, for several states and provinces, to a maximum of 5.86 per million words, in the US state of Alabama (Coats Reference Coats2022a).

Table 9. Overall frequency of double modals (per million words)

However, the rareness of the feature and the relatively small number of authentic double modals attested in the CoBISE data mean that the differences in relative frequencies at country level are not significant, according to standard statistical tests, with the exception of the difference between England and Scotland.Footnote 15 Methodological considerations may also affect the country-level comparison of relative frequencies: while the number of false positives in the annotated data (non-double modals incorrectly transcribed by ASR as double modals) is zero, due to the manual filtering of the search hits, there may be false negatives in the corpus (actual double modals transcribed incorrectly by ASR), which would not be captured by searches using regular expressions. Considering the fact that the YouTube ASR algorithm is likely to be more inaccurate for Scottish speakers (Tatman Reference Tatman2017), there could be proportionately more false negatives in the Scottish data than in the English data; hence, the relative frequency of double modals in Scottish transcripts may be underestimated. Quantifying the false negative rate, however, would require comparison of ASR transcripts with verified manual transcripts, and manually transcribing a large sample of corpus transcripts is an undertaking beyond the scope of this study (see, however, Coats Reference Coats, Busse, Dumrukcic and Kleiber2023, for a rough method to check for false negatives).

A cautious interpretation of the relative frequency data from the annotated transcripts would be that speakers in Scotland use more double modals, a finding in line with previous studies. More data, both in terms of overall number of transcripts and in terms of the range of speech situations reflected in the videos, from a greater variety of locations, as well as a set of manually transcribed videos allowing estimation of false negative rates, would be needed before the relative frequencies of double modals in Scotland, England, Wales and Ireland could be compared with some degree of certainty, and before the observed differences in relative frequencies could be considered robust.

The map in figure 1 depicts the number of manually annotated true double modals falling within the boundaries of administrative subregions in the UK and Ireland as relative frequencies per million words. Although the map suggests that double modals are more common in more northerly locations, the unequal sizes of the administrative areas make it difficult to perceive a spatial pattern, and some high relative frequencies, for example in the counties Meath, Westmeath, Roscommon, Sligo and Donegal in the Republic of Ireland, correspond to single occurrences of a double modal. It should also be noted that the geographical distribution may in part reflect the different composition of the channel subcorpora in terms of video types – as noted above, while council meetings may represent a suitable pragmatic context for the use of double modals, other types of transcripts, such as recorded speeches or informational news videos, do not.

Figure 1. Double modals by county, relative frequencies

One way to address outliers caused by small or unequal subsample sizes (i.e. the CoBISE channel sizes mapped to administrative regions) is to calculate for each administrative subunit a local spatial autocorrelation statistic based on an aggregate measure of nearby values. Spatial autocorrelation, which quantifies the tendency of values of a spatially distributed variable to exhibit similar values at nearby locations, can be used to identify local and regional patterns (Anselin et al. Reference Anselin, Kim, Syabri, Fischer and Getis2010). The local spatial autocorrelation statistic Getis-Ord![]() $\;G_i^\ast $ is a ratio: the weighted average of the values in neighboring locations divided by the sum of all values, then scaled as a Z-score. For a given location, determination of which locations are considered nearby can be made on the basis of polygon continuity (i.e. bordering administrative regions), distance within a certain cutoff threshold, the k nearest neighbors, or based on other functions, and there are also various methods for the calculation of the weighting function (see Getis Reference Getis, Fischer and Getis2010). In the exploratory analysis of spatial data, the calculation of a local autocorrelation statistic is used to identify ‘hot spots’ and ‘cold spots’, whereby the weighting function serves to smooth values of nearby locations.

$\;G_i^\ast $ is a ratio: the weighted average of the values in neighboring locations divided by the sum of all values, then scaled as a Z-score. For a given location, determination of which locations are considered nearby can be made on the basis of polygon continuity (i.e. bordering administrative regions), distance within a certain cutoff threshold, the k nearest neighbors, or based on other functions, and there are also various methods for the calculation of the weighting function (see Getis Reference Getis, Fischer and Getis2010). In the exploratory analysis of spatial data, the calculation of a local autocorrelation statistic is used to identify ‘hot spots’ and ‘cold spots’, whereby the weighting function serves to smooth values of nearby locations.

Figure 2 shows a map of Getis-Ord![]() $\;G_i^\ast $ values, calculated on the basis of relative frequencies of double modals, after removal of questionable tokens (i.e. those judged as ‘true’ but annotated with an asterisk during the manual inspection step). Now, a different picture emerges: the autocorrelation values largely correspond to previous reports on the frequency of double modals in the British Isles: relatively common in northernmost England and in Scotland, with the highest value found for the Scottish Borders, but with some attestations in the English Midlands and south. Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland exhibit lower values.

$\;G_i^\ast $ values, calculated on the basis of relative frequencies of double modals, after removal of questionable tokens (i.e. those judged as ‘true’ but annotated with an asterisk during the manual inspection step). Now, a different picture emerges: the autocorrelation values largely correspond to previous reports on the frequency of double modals in the British Isles: relatively common in northernmost England and in Scotland, with the highest value found for the Scottish Borders, but with some attestations in the English Midlands and south. Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland exhibit lower values.

Figure 2. ![]() $\;G_i^\ast \;$score (20-nearest-neighbors binary weights matrix, questionable assessments removed) by county

$\;G_i^\ast \;$score (20-nearest-neighbors binary weights matrix, questionable assessments removed) by county

Although these exploratory maps seem to support the patchwork of results from previous studies, due to the small number of confirmed double modals in the CoBISE data, they cannot be considered robust. The values of the Getis-Ord ![]() $\;G_i^\ast \;$test statistic for the individual counties and shires do not generally meet the standard level of significance at α=0.05, except for Northumberland, a few Scottish shires and two Irish counties.Footnote 16 In addition, the k-nearest-neighbors weights model, if it is to be conceived of as a model for communication patterns that underlies the spread of the feature, does not account for geographical features that impede communication, such as the Irish Sea. Nevertheless, mapping a spatial correlation statistic in an exploratory manner provides a result that can be reconciled with what is known from previous studies about the distribution of the feature.

$\;G_i^\ast \;$test statistic for the individual counties and shires do not generally meet the standard level of significance at α=0.05, except for Northumberland, a few Scottish shires and two Irish counties.Footnote 16 In addition, the k-nearest-neighbors weights model, if it is to be conceived of as a model for communication patterns that underlies the spread of the feature, does not account for geographical features that impede communication, such as the Irish Sea. Nevertheless, mapping a spatial correlation statistic in an exploratory manner provides a result that can be reconciled with what is known from previous studies about the distribution of the feature.

5 Discussion

5.1 Double modal inventory and frequency

The data presented in section 4.1 show that the double modal inventory of the British Isles is larger than has previously been documented. Types known from earlier descriptions of dialectal speech and dialect dictionaries, as well as those more comprehensively documented in surveys, research interviews and corpora of transcribed speech, are attested in CoBISE, but the data also show use of double modal types that have hitherto either not been the focus of research attention or not been documented at all.

One of the most interesting findings is would might, a form mostly absent from previous accounts of double modals in the British Isles, as the most common type. It is attested in the current data in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, but also shows a broad geographic distribution in North America, where it is not concentrated in the American Southeast, the region traditionally most strongly associated with double modal use – California has the highest number of attestations (Coats Reference Coats2022a). In terms of meanings, would might seems to be used to express epistemic possibility in the context of intrinsic volition or a hypothetical situation. Examination of the video segments from CoBISE in which would might occurs suggests meanings approximately equivalent to conditional or hypothetical statements further marked for epistemicity through the addition of an epistemic stance adverbial, along the lines of it would possibly or it would maybe. Would might in CoBISE occurs in utterances such as I would might like to make it clear; it would might need additional, other meetings; I'm not sure what the implications would might be, but they may not be too bad; that would might be my suggestion; we can't expand into Manchester, as much as I would might want to do so, and others. The many occurrences of this type in the data and lack of geographic restriction, when considered alongside the naturalistic usages documented from North America and the dearth of previous attestations, suggest that would might may be an emergent global double modal for the expression of careful epistemicity. As for the frequencies of other types, those with will or would as the first element are more common in CoBISE, in contrast to North America, where types with might as the first element dominate, a finding in line with previous reports on double modal inventories in the British Isles and America.

5.2 Geographical distribution

The prevailing view of previous research is that double modals in British and Irish speech are restricted to Scotland, the north of England (Northumberland and Tyneside) and Northern Ireland. Indeed, some studies find that double modals only occur in these regions (e.g. Beal Reference Beal2004: 127: ‘Whilst these double modal constructions are found in Scots and in some dialects of the southern USA, the only area of England in which they occur is Northumberland and Tyneside’). According to Hickey, double modals are ‘not found in the south of Ireland and only very rarely in the north nowadays’ (Reference Hickey and Kirkpatrick2010: 86; see also Reference Hickey2005a: 102).

This study, however, demonstrates that double modals are used in naturalistic speech in the British Isles from a wide variety of locales, including in regions where the feature has not previously been systematically investigated. The data from CoBISE show that double modals are, at least in the context of semi-formal government meetings or public events, in use in conversational contexts not only in Scotland, Northern England and Ulster, but also in the English Midlands and south, Wales, and the Republic of Ireland. A preliminary analysis of double modals in data from the Spoken British National Corpus 2014 (Spoken BNC2014; Love et al. Reference Love, Dembry, Hardie, Brezina, McEnery, McEnery, Love and Brezina2017; Brezina et al. Reference Brezina, Love, Aijmer, Brezina, Love and Aijmer2018) confirms the presence of double modals in southern and Midlands speech, as well as in Scotland and the English north, in informal conversation (cf. Morin Reference Morin2021a). A total of 57 authentic double modals were found in the Spoken BNC2014. This corresponds to a higher relative frequency than in the CoBISE data (5 pmw vs. 1.67 pmw). In contrast to CoBISE, the Spoken BNC2014 consists of recordings of informal conversations held in private contexts, mostly between friends and family members; it is reasonable to assume that the lack of formality of context favors more use of non-standard features such as double modals (cf. Miller & Brown Reference Miller and Brown1982: 13).

An additional piece of evidence comes from social media data, where preliminary findings show that in geolocated tweets, will can is used mainly in Scotland but also in the English Midlands and south and in Wales.Footnote 17

In light of this, a reconsideration of the conceptualization of double modal inventories and their association with specific regional varieties or local dialects seems appropriate: given enough data, one is likely to find at least one use for most double modal types in most locations. The double modal data from this study support Kortmann's observation that variation in dialect syntax typically has a wide areal reach and is ‘in many cases a matter of statistical frequency rather than the presence or absence of a feature’ (Reference Kortmann, Auer and Schmidt2010: 842). Rather than a model in which a given double modal combination is held to be either present or absent in a given variety, the data from this study support an account in which individual double modal types, although rare, are theoretically possible in most varieties of English used in the British Isles or elsewhere, a conceptualization also in line with recent dialect-corpus-based approaches to the study of regional variation (e.g. Nerbonne Reference Nerbonne2009; Szmrecsanyi Reference Szmrecsanyi2011, Reference Szmrecsanyi2013; Grieve Reference Grieve2016). Thus, although will can can be found in naturalistic speech from Kent and Essex, it is more likely to be encountered in conversational speech in the Scottish Lowlands; likewise, might could could be spontaneously produced in a conversation in Ireland or in London, but is more likely to occur in a conversation in Georgia or Alabama in the US. As noted above in section 4, however, the number of double modals in the CoBISE data and the size of the channel subcorpora are not sufficient to provide reliable information about the geographical distribution of particular types, and can only provide a general overview of the tendency for double modals to be geographically distributed. In line with previous accounts, they are more common in Scotland, the north of England and Northern Ireland.

5.3 Caveats

Several considerations pertaining to the nature of the corpus data and the procedures used to identify and verify double modals should be noted. First, as discussed in section 4.3, although manual verification can remove false positives, the method cannot account for false negatives. Considering the fact that some Scottish modal verb constructions include enclitic forms that do not directly correspond to standard English (e.g. wullna ‘will not’, cannae or canny ‘cannot’), the relative frequencies of double modals calculated for Scotland in section 4 may be underestimates.

Another consideration concerns the speakers in the videos that comprise the corpus transcripts. Although the recordings are mainly of meetings or other events organized by councils and other local governmental organizations, there is no way to determine the residency of all the speakers in the transcripts. It is likely that some speakers in the corpus are not locals of the areas represented by the councils whose channels have been sampled in the corpus, but rather were raised elsewhere and moved to those localities. Indeed, during the manual verification process, a few instances of Scottish- or Irish-accented speech in English council sessions were encountered. Nevertheless, given the nature of local government, it is likely that most speakers are local residents, and given the size of most of the channel subcorpora, their linguistic signal would predominate in the corpus. Ideally, however, a corpus in which demographic information was known about individual speakers would be more suitable for making inferences about regional varieties.

As noted in section 2, relatively few local councils in the Republic of Ireland upload recordings of council meetings to their YouTube channels, reflecting in part the different legal framework for public access to local government meetings in Ireland compared to the UK, but possibly also different attitudes towards public speech. One Irish council rejected a proposal to broadcast or record council meetings because it could encourage ‘grandstanding’ by council members, who, possibly enticed by the prospect of online fame, might change their behavior in order to appeal to a potentially large online viewership, instead of speaking in a presumably more down-to-earth and businesslike manner to fellow council members in a non-broadcast council session.Footnote 18 For the analysis of double modals presented in this study, the fact that Irish council YouTube channels may be more likely to contain scripted dialogue such as speeches or news videos, rather than recordings of interactions in the pragmatic contexts in which double modals have been proposed to be more likely (viz. ‘situations of caution and sensitivity’ where politeness is required, Montgomery Reference Montgomery, Montgomery and Nunnally1998: 96), means that the observed frequencies of double modals for Ireland may be underestimates. The examination of a larger number of transcripts, from a wider range of interactional types, would be necessary in order to further investigate this possibility.

The manual verification procedure used in this study relies on the judgment of a single annotator. Although the annotation criteria for the determination of true double modals (lack of prosodic marking, lack of semantic/discourse incoherence) were formal and not subject to arbitrary interpretation, a better approach, unfortunately not possible within the scope of this study, would be to use an annotator agreement measure for multiple annotators, ideally including persons familiar with local speech patterns in the subregions or regions of the sampled channels.

Despite these caveats, the evidence for diversity in the use of double modals in the British Isles seems strong, and it is hoped that the results presented here will be of interest as evidence in discussions of microsyntactic variation, modality in English and English language history, but also provide a new impetus for work along similar methodological lines that can help to document the use of infrequent features in English varieties.

6 Summary and conclusion

A large corpus of ASR transcripts of naturalistic speech from the UK and Ireland was used to identify instances of double modals using regular expressions and a manual verification procedure. The results show that double modals are more widely used in the British Isles than has previously been documented, both in terms of the size of the double modal inventory and the geographical distribution of the feature. Although raw relative frequency data for double modals do not show a clear regional patterning, a local spatial autocorrelation analysis based on a 20-nearest-neighbors spatial weights matrix, taking only unquestionable attestations into consideration, largely recapitulates the prevailing view that double modals are more commonly used in Scotland, the north of England and Northern Ireland. More data would be needed, however to confirm this tendency, as well as to ascertain the regional use of particular double modal types.

The type would might, the most frequent double modal in this study, may represent an emergent global double modal, based on its broad geographic distribution in these data and in data from North America, its absence from most earlier accounts of double modals and its likely meaning as an exponent of hypothetical epistemic possibility. The modal meaning of would might (and potentially of other combinatorial double modal types), in turn, may reflect complex ongoing changes in the semantics of the English modal auxiliaries, linked to processes of grammaticalization, that exemplify a shift towards increased epistemicity (Coates Reference Coates1983; Traugott Reference Traugott1989; Leech Reference Leech, Facchinetti, Palmer and Krug2003; Leech et al. Reference Leech, Hundt, Mair and Smith2009; Kranich & Gast Reference Kranich, Gast, Zamorano-Mansilla, Maíz, Domínguez and Martín de la Rosa2015). In the context of further research into double modals, it may be useful to compare the frequencies of different markers of epistemic possibility, volition, ability or obligation as single modal auxiliaries, double modals, adverbials, adverbials or other expressions (cf. Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003; Kranich & Gast Reference Kranich, Gast, Zamorano-Mansilla, Maíz, Domínguez and Martín de la Rosa2015) in a corpus where these elements have been disambiguated for modal meaning. The undertaking could represent a potential future use case for data from CoBISE.

Despite findings in recent decades that suggest double modals would be falling into disuse in parts of the British Isles, this study can show that the feature is, although rare, a relatively robust syntactic pattern in spoken language. The outlook for future investigations of double modals and modality in general in CoBISE and similar data sets is promising, given the size of the corpus and the likelihood that it contains a rich repository of expressions of modality, and in the future, continued improvements to ASR algorithms and growing access to streamed interactional data may enable more extensive investigations of naturalistic multiple modal use in the British Isles and beyond.