1 Introduction

In English, there are a variety of causal adjunct phrases such as because of, as a result of, on account of, owing to and in spite of. It was reported recently (Carey Reference Carey2013; Schnoebelen Reference Schnoebelen2014; Kanetani Reference Kanetani2015, Reference Kanetani2016, Reference Kanetani2019; Bohmann Reference Bohmann and Squires2016; Bergs Reference Bergs, Seoane, Acuña-Fariña and Palacios-Martínez2018; etc.) that a new structure, because X, can be found in colloquial registers, such as conversations and blogs, along with because of NP. Nominals are not the only category employed in the complement, and because now introduces adjectives, adverbs and even verbs. In this article, I delve into the reasoning behind the innovative use of this causal expression, which, in fact, dates to at least the seventeenth century; a survey has also been conducted on other causal adjuncts to determine whether the same kind of innovation can be observed with regard to them. While conducting the survey, it was observed that the innovative usage demonstrated in because X can also be observed in in case X. The X category appears to have been extended in this case as well.

We will survey several causal adjuncts that show different levels of token frequency, such as as a result of, in spite of and owing to. The truncation of the final preposition is demonstrated in all the adjunct phrases in the survey, yet the category of the complement is essentially restricted to nominals and gerunds in the case of other causal phrases. We will also examine the factors segregating the two groups of adjuncts, namely because/in case X and other causal adjuncts.

The structure of the article is as follows: section 2 deals with the nature of the cause–effect coherence relation and the process of deriving the new structure of because X. Simultaneously, in this section, we delve into the problem of the origin of the phrase occupying the X slot, which is considered an AP complement by Bergs (Reference Bergs, Seoane, Acuña-Fariña and Palacios-Martínez2018). With data from the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and some additional corpora, I claim that the usage began with NP complements and later extended to APs and other types of complements. Section 3 includes observations of the same kind of category extension in in case X and the common ground that this phrase shares with its predecessor, because X. In section 4, I examine five causal adverbial phrases (in spite of, by virtue of, owing to, on account of and as a result of) and examine the difference between two groups of adjuncts, one that extends its complement types and one that does not. Section 5 is a summary of the entire argument.

2 Causal relation and because X

2.1 Coherence relation of cause–effect

The standard usage of because is twofold: it is either employed as a subordinate conjunction, taking a clause as its complement, or as part of the adjunct phrase because of, taking an NP as its complement (Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners, Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, etc.). Recently, a third usage has become a matter of great concern, especially in the colloquial and informal registers of conversations and blogs, namely, because X, as exemplified in (1)–(2).

(1) I cannot go out today because homework. (Kanetani Reference Kanetani2015: 63)

(2) A: I definitely kind of viewed him as a suspect.

B: Why?

A: Well, because motive. (Carey Reference Carey2013)

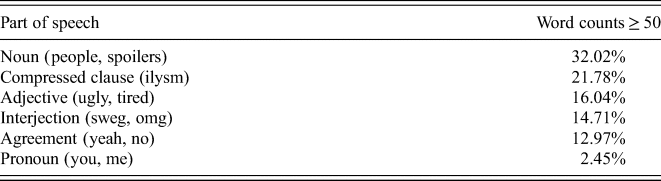

The nominal complements of because in (1)–(2) are not accompanied by determiners. They are bare nouns and do not constitute noun phrases (this does not mean that NPs are not selected in the complement of because, as exemplified in (9c–e)). However, nouns are not the only category found in the complement of because. According to Schnoebelen (Reference Schnoebelen2014), the distribution of complements can be summarized as in table 1.

Table 1. Distribution of because X (Schnoebelen Reference Schnoebelen2014)

In addition to the categories listed in the table, even some instances of adverbs and verbs are reported in Schnoebelen (Reference Schnoebelen2014), such as because seriously, because obviously, because stop, because want and because sleep (although these verbs may be considered instances of nominal expressions, as suggested by Schnoebelen).

Key to understanding this phenomenon are the coherence restrictions proposed by Kehler (Reference Kehler2002, Reference Kehler and Truswell2019). He presented three types of coherence relations, that is, resemblance, cause–effect and contiguity. The second type of relation, cause–effect, is crucially important in this context. The relevant restrictions for this coherence relation are given below:

(3) Kehler's restrictions on cause–effect coherence

(a) Result: P → Q (e.g. and as a result, therefore)

George is a politician, and therefore he's dishonest.

(b) Explanation: Q → P (e.g. because)

George is dishonest because he's a politician.

(c) Violated Expectation: P → ~Q (e.g. but)

George is a politician, but he's honest.

(d) Denial of Preventer: Q → ~P (e.g. even though, despite)Footnote 2

George is honest, even though he's a politician.

(Kehler Reference Kehler2002: 20–1)

P stands for the proposition of the first clause, and Q for that of the second clause. As is clear from the restrictions, cause–effect relations are maintained between propositions. Subordinators like because or though connect clauses; therefore, they are typical examples of cause–effect connectors.

However, we also observe causal adverbial phrases taking NP complements instead of clauses. In these cases, the complements are expected to designate propositional contents. To fulfill this requirement, several strategies are needed: the use of gerundive clauses, NP + relative clauses/participial clauses/infinitival clauses, etc.

To demonstrate the use of such strategies, we examine the phrase in the face of, which is ambiguous regarding locational, causal and concessional interpretations. In the locational interpretation, the complement of this phrase tends to be simple in structure. In contrast, when it is used in the causal or concessional reading (namely, in the coherence relation of cause–effect), we can easily find examples in which complement nominals are modified by relative, participial, infinitival or content clauses. The examples are taken from the British National Corpus (BNC).

(4)

(a) It was like throwing heresy in the face of a sacred cow. (BNC AN9)[LOCATION]

(b) Edward Heath's attempts to commit the party to something more dynamic … collapsed in the face of a corporate culture which had become used to having things its own way under a succession of both Conservative and Labour governments. (BNC ADV) [NP + relative clause][CAUSE]

(c) Mr Arafat is seeking to reunite the organisation in the face of criticism that his associates are corrupt and inefficient and that his decision to join the US-brokered Middle East peace talks has led the Palestinian cause into an impasse. (BNC AJM) [NP + content clause][CONCESSION]

The difference found in the structure of the complements attests to the fact that cause–effect relations are observed between propositions.

It is not always the case that a cause–effect relation is necessarily realized by propositional contents expressed in clause-like constituents, however. In some cases, simple noun phrases may occur in the complements of causal adjuncts. These noun phrases work as reference points (Langacker Reference Langacker1993) for the contextually plausible proposition lurking behind the linguistic expressions. We will now turn to an examination of these types of expressions.

Here we are concerned with the distribution of complements coming after the causal adverbial phrase because of, which appears 17,559 times in the BNC (the total yield of the search strings because_of [17,438] and because of [121]). Taking 500 random instances from the database, I classified the complements into four types: event nominals designating some event or state brought about by a change of state; action nominals referring to some agentive act of participants; clauses designating fully propositional contents; and others. Table 2 shows the breakdown and examples of each category (when the complements consisted of more than one nominal expression, I sorted them by the type of the first complement).

Table 2. Distribution of the complements of because of (adapted from Okada Reference Okada2013: 174–5)

More than half of the occurrences consist of nominals somehow designating an event or action (action/event nominals). These are the types of complements whose expansion into propositional content is relatively easy because the nature of the relevant action or event is explicitly designated by the head nouns. Even the clauses, all of which are wh-questions, sometimes occur in the complement. They designate open propositions, so they are counted as instances of propositional contents.

Apart from these types of complements, slightly fewer than half of the occurrences are realized by other nominals. The first group in this category consists of nominals designating the attributes of some participant in the discourse, which is most likely to be extended to a propositional content of having the attribute of X, and nominals designating measures taken by some participant, which is likely to be extended to resorting to the measures of X. Examples are provided below:

(5)

(a) Indeed we know that they valued the material (rhinoceros horn) in part for its

supposed aphrodisiac properties and in part because of its sensitivity to mercury (=its having sensitivity to mercury), which helped to insure against drinking

poisoned wine. (BNC FBA) [ATTRIBUTES]

(b) Because of her coalition-building skills (=her resorting to coalition-building

skills), she led successful change projects that in turn brought her recognition and early promotions. (BNC FAH) [MEASURES]

The second group consists of nominals referring to entities. These nominals are likely to be interpreted as the existence/advent/function of X.

(6)

(a) I'm, I'm sorry if it was too difficult to, to follow, either because of the microphones (=malfunction of the microphones) or … (BNC JNJ)

(b) The Cotmanhay Open on the Erewash Canal had to be called off because of ice. (=bad conditions caused by ice on the water) (BNC A6R)

The last group of nominals in the classification includes pronouns, demonstratives and names. Demonstratives (this/that) can refer to a proposition in the preceding context, so they may be regarded as propositional by nature. On the other hand, personal pronouns and names are essentially used to refer to things or people. When they are employed in the complement of because of and are expected to evoke propositional content, they refer to some participants involved in the proposition, and they work as a reference point for evoking that proposition. An example of the use of a proper name in the complement of because of is presented below:

(7) Frankie tried his best not to like them because he knew they were only pretending to be nice. He would be poisoned if he accepted food or sweets from them … Sweetheart knew about these things. She constantly needed to caution him about the many dangers he was either too young or too stupid to recognize for himself … Because of Frankie she had graciously rejected the opportunity of a lifetime. (BNC ACW)

Here, Frankie in the complement of because of evokes propositional content such as Frankie needing protection. Even linguistically simple names can evoke a cause for the effect described in the main clause. We require ample contextual support to assume the proper content of the proposition in question. Therefore, the number of relevant instances is rather small; nevertheless, it is not impossible to use pronouns and names in this way.

2.2 The formation of because X

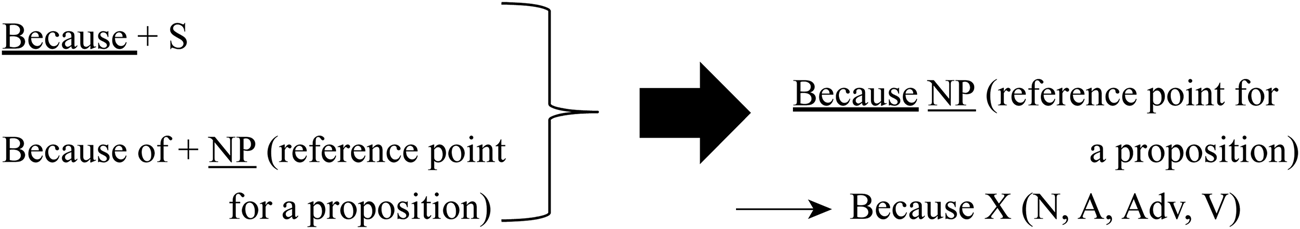

In this section, we will examine the innovative usage of because X. When examining the new form because X, attention should be paid to the basic usage of because; it can take a clause as its complement when used as a subordinator or it can take an NP when used as an adverbial causal adjunct with the assistance of the preposition of. The NP complement, as was claimed in the preceding section, is a reference point for the contextually activated proposition, which is the cause of the effect exhibited in the main clause of the relevant sentence. These two structures can be assumed as the input for the innovative construction; namely, parts of the inputs are combined to form the new structure. This is an instance of formal blending in the sense of Turner & Fauconnier (Reference Turner and Fauconnier1995) and Barlow (Reference Barlow2000).

The unification of the input can yield two possible outputs: because + NP or because of + S. As for the latter output, because of + S, its equivalents are already used frequently in the forms because of + head N + restricting elements like relative/participial/ infinitival clauses, as in (8).

(8)

(a) It is not an acceptable long-term rate, because of the damage it does to industry and homeowners. (BNC A3T) [NP + relative clause]

(b) Anglian Water Authority refused to attend the meeting of residents in Oakham because of rules preventing them discussing matters that might depress the share price during privatization, … (BNC A92) [NP + participial clause]

In the register of texts on the web, where briefness of expression is a typical characteristic, as exemplified by the use of compressed clauses (ilysm, idc, idk, etc.) or phonetic equivalents (u for you, 4 for for, ppl for people, etc.), because NP (subordinator + NP) meets the need of the registers. This phrase is now acknowledged as a conspicuous feature of texts on the web. This was illustrated by the fact that because was selected as the ‘Word of the year 2013’ by the American Dialect Society (ADS): ‘(T)he very old word because exploded with new grammatical possibilities in informal online use’ (www.americandialect.org/because-is-the-2013-word-of-the-year).

The important point to note is that the NP is a reference point for a proposition, so the S in the complement of because and the NP in the complement of because of are pragmatically equivalent in that they either syntactically designate, or conceptually evoke, propositional contents. This equivalence allows the mixture of the input demonstrated in figure 1.

Figure 1. Formation of because X

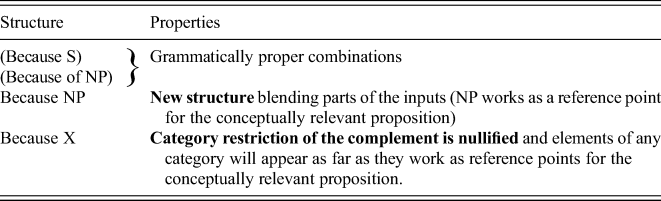

Another point that must be noted is that, in the new structure because NP (subordinator + NP), the category restriction of the complement is nullified because the restrictor of is missing. Now that the category restrictor is absent, there is no reason to limit the reference point to noun phrases. As far as the linguistic expression works as a reference point, items of any lexical category can occupy the complement position. The lack of category restrictors and the loose connection between a reference point and its target allows a wide range of complements that have various types of conceptual relations with the evoked propositions. The new blended structure ‘can be developed, once it is set up, on its own terms’ (Turner & Fauconnier Reference Turner and Fauconnier1995: 202). The stages of development of because X are summarized in the table below; this topic will be further explored in the next subsection.

Table 3. The development of because X

The variety of the complements and their varied relations to the evoked propositions are demonstrated by the instances in (9). (9c–e) are taken from the Corpus of Global Web-based English (GloWbE; Davies Reference Davies2013a). The GloWbE (1.9 billion words) consists of data gathered in December 2012 from the web pages of twenty countries (the United States, Great Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, India, Pakistan, South Africa, Nigeria, etc.), and about 60 percent of the data came from blogs (for data from corpora, tags have been added at the end of the source information of the examples to show the genre of the sources where the information is available, such as general, blog, news, fiction, magazine, etc.). Here we essentially concentrate on nominal complements, but the variation of the evoked propositions and the role of the complements in the propositions clearly show the nature of the reference points.

(9)

(a) I cannot go out today because homework. (=(1))

(b) A: I definitely kind of viewed him as a suspect. (=(2))

B: Why?

A: Well, because motive.

(c) I've suggested to couples that they agree not to break up a relationship because a fight. It's very important to have a safe space for fighting. (GloWbE Canada: general)

(d) The Queens [sic] father was not supposed to be king until Edward his senior brother abdicated the throne, all because a woman. (GloWbE Great Britain: blog)

(e) That continued in Italy up through the 1950s. those [sic)] who go to concerts voluntarily agree to the set of rules of etiquette but i think many many choose not to participate in live classical concerts because the rules. (GloWbE United States: general)

Specifying the evoked propositions behind the complements shows that the complements occupy different positions and roles in the relevant propositions, so no uniform treatment would be possible for capturing the relation between the vehicle (complement nominals) and the target (evoked propositions). In (9a), the recovered proposition would be (I have) homework; in (9b), it would be (he has a) motive. The example in (9c) can be expanded to (they have) a fight, that in (9d) to (Edward was in love with) a woman, and that in (9e) to (they must follow) the rules. The forms of the propositions are varied, and the positions of the complements in the recovered propositions are also varied. The only common feature of the examples in (9) would be the role of a reference point assumed by the complement nominals.

In the cases of (5)–(7), because of employs a complement functioning as a reference point for the relevant causal proposition. The same observation applies to the complement of because X. The difference lies in the fact that, with the truncation of the preposition of, elements of any category can occur in the complement of this new phrase.

2.3 The historical development of because X

It is not easy to ascertain when and how a new structure was generated. Bergs (Reference Bergs, Seoane, Acuña-Fariña and Palacios-Martínez2018) claimed that the new structure because X began with adjective complements after conducting a partial search of the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA; Davies Reference Davies2010–), which consists of 400 million words, yet, as far as I have been able to infer based on a search of the relevant data, it appears that the structure because X began with NP complements, as presented in figure 1. Additional data from the OED, COHA and GloWbE will be presented to demonstrate the origin of this phrase.

First, we must examine the data presented by Bergs (Reference Bergs, Seoane, Acuña-Fariña and Palacios-Martínez2018).

(10)

(a) be sure that there is a canker somewhere, and a canker not the less deeply

corroding because [it is] concealed. (Charlotte Brönte, Shirley 1849)

(b) This would at least be honest, though I think it would be unwise, because [it is] unnecessary. BETTER TO GIVE EVERYBODY A FAIR CHANCE. (COHA 1820)

(c) And a Bostonian, appeals to history, and shows that Boston is first, because [it is the] oldest. (COHA 1823) (Bergs Reference Bergs, Seoane, Acuña-Fariña and Palacios-Martínez2018: 44-5)

A salient point in these examples is that the deleted subject of the because-clause is identical to the subject of the main clause, and supplementing it with a copular verb is adequate to recover the full-fledged proposition behind the string of because +adjective (or past participle). (In the case of (10c), sparing the definite article from the target of omission damages the rhythm of the phrase, as my informants suggested.) This situation reminds us of the regular deletion process evident in many subordinators, as illustrated in (11).

(11)

(a) Although no longer a minister, she continued to exercise great power.

(b) Once away from home, she quickly learned to fend for herself.

(c) He can be very dangerous when drunk.

(d) While in Paris, I visited Uncle Leonard. (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1267)

Considering (11), the examples in (10) do not appear at all innovative. Rather, they only conform to the regular deletion process observed widely in subordinate clauses. This is completely different from the free selection of reference points evident in (9). We must segregate the regular ellipsis verified at least as early as the end of the sixteenth century in the OED, as in (12), from the free variation of complements to locate when and how the innovative usage of our phrase of concern began.

(12)

(a) 1591 While [they were] in ambushment close they lay on land.

(b) 1611 Quhil in this weak estait, all meanes I soght To be aweng'd on him.

(While [I was] in this weak state, all means I sought to be avenged on him.)

(c) 1643 God … takes his opportunity, (for we are best, when [we are] at worst).

(from the OED)

In parallel with (12), the omission of ‘subject + copula’ was observed around the end of the sixteenth century in the case of the subordinator because as far as the citations in the OED are concerned.Footnote 3

(13)

(a) 1586 Waiwardly proud; and therefore bold, because extreamely faultie.Footnote 4

(b) 1592 Great houses long since built Lye destitute and wast, because inhabited

by Nobody.

(c) 1596 He is likewise called Sathan, because an aduersary: . . and Belial,

because yoakles [yokeless]. (from the OED)

As shown in (13), the complements that follow the omitted ‘subject + copula’ are not only adjectival (participial) but also nominal. The example in (13c) is a good case of a noun and an adjective being employed as the complements of because within the same sentence. Both nouns and adjectives are qualified as predicates following copular verbs; in that sense, there is no difference between the two lexical categories. Therefore, it is difficult to determine which category was first used in the history of this regular deletion process.

Incidentally, main-clause subjects are not the only candidates for omitted subjects of because-clauses. Sometimes, main clause objects are selected as the target of deletion in the subordinate clause, as in (14).

(14)

(a) 1598 One thinkes it misbeseeming the Author because a Poem, another

vnlawfull in it selfe because a Satyre.

(b) 1641 I finde … some others unpriested by Councells because ordained by

Presbyters alone. (from the OED)

What is most revealing in the citations of the OED is that all the adjectival complements (including adjectives, present participles and past participles) can be analyzed as regular ellipses of a subject, identical to the subject (or object) of the main clause, and a copula.

Regarding the breakdown of complement types, there are 177 instances of regular deletions in which the deleted subject is identical to the subject of the main clause (85 past participles, 58 adjectives, 19 nominals, 10 present participles, 4 prepositions and 1 adverb) and 19 instances in which the deleted subject is identical to the object of the main clause (13 past participles, 3 adjectives, 2 present participles and 1 nominal).

Apart from these, there are 18 cases in which the complement (either adjectival (13) or adverbial (5)) occupies the position of a conjunct in a coordinate phrase modifying nominals, adjectives or verbs, as in (15).

(15)

(a) 1879 If it be soft, broken granite … will prove [a useless because an

unendurable surface]. (adjectival coordination)

(a´) ⇒If it be soft, broken granite … will prove a useless surface because [it is] an

unendurable surface.

(b) 1678 This they do [most slow Because most choicely]. (adverbial coordination)

(b´) ⇒This they do most slow because [this they do] most choicely.

As represented in (15a´, b´), these instances are easily expanded into full-fledged propositions by adding a subject (present in the main clause) and either a copula (in the case of adjectival coordination) or a verb phrase of the main clause (in the case of adverbial coordination). Therefore, these examples can be considered subcases of the regular deletion type in which the deletion is regulated and recoverable from the immediate context.

Regarding complements that are not regulated by the regular deletion process in subordinate clauses, they are evident in examples with NP complements at least as early as the seventeenth century.

(16)

(a) 1622 Shall I wasting in Dispaire, Dye because a Womans faire?

(b) 1655 And now was not Waltham highly honoured … when amongst those

fourteen [Commissioners], two were her Gremials, the forenamed Nicholas

living in Waltham, and this John, having his name thence, because birth

therein.

(c) 1665 I … think my Tuesday letter was miscarried, because no Answer to it.

(from the OED)

In fact, there are two additional examples listed earlier in the OED that were excluded from the set of relevant data, as presented in (17).

(17)

(a) 1384–5 ‘Of faldgabul [rent paid for a fold] nothing, because no fold. Of wodewexen [woodwaxen/dyer's-broom] nothing, because it was depastured by the Lord's sheep. Of pasture in le Coumb, whereof 7s is customably rendered to the lord, nothing, for the cause aforesaid …’

(b) 1483 We wold haue … drowned yow by cause your dissolute & oute of tyme ianglyng [your dissolute and unreasonable jangling].

The first sentence of (17a) is the oldest citation of because X in the OED. It is found in a passage by John Bolt, Reeve of Wynttenham, in the Accounts of the Obedientiars of Abingdon Abbey. This is part of the appendix to the Accounts published in 1892 by the Camden Society (https://archive.org/details/accountsofobedie00abin/page/143/mode/2up). The OED lists the citation as an example from the late fourteenth century, but the text has obviously been modernized by the editors (for example, the verb ‘depasture’ is not included among the entries of the Middle English Dictionary, and its oldest recorded use is in 1586 in the OED). As for (17b), scribal variations can be observed. This passage is part of the article ‘Here Follows the Assumption of the Glorious Virgin Our Lady St. Mary’ in The Golden Legend (vol. 4) by William Caxton. In the texts provided by Fordham University (https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/goldenlegend/GoldenLegend-Volume4.asp) and Intratext.com (www.intratext.com/IXT/ENG1293/_P5Z.HTM), the preposition of is added immediately after because. Editorial adjustments and textual variations are inevitable problems in data searches of older texts, hence these examples have not been used as evidence of the history of because X in this article.

Returning to (16), according to Lenker (Reference Lenker2010: 165), ‘Only after 1750, because finally replaces for and becomes the all-purpose connector of Present Day English’. Therefore, because did not appear to be a major connecting device before that time. However, in the OED, both because (that) +S and because of +NP can be found as early as the fourteenth century; thus, by the time the examples in (16) were written, both of the input structures for the blending process were already available irrespective of the token frequency of the input.

The first instance of an apparently bare nominal in the complement position is (18), which is part of a piece of prose by Andrew Marvell (The Rehearsal Transprosed). I could not find any other instance of bare nominal use in the citations of the OED, and it is questionable whether it is plausible to count this as a proper example because of its metalinguistic usage. In the context of metalinguistic correction, part of a phrase can be isolated and combined with a negator, as in The Army's accident rate had gone down, not up (COHA 1943). (The following complement of soape-bubbles in combination with the head noun also yields a phrasal constituent.)

(18) 1673 From the manufacture – he will criticise because not orifacture – of

soape-bubbles. (from the OED)

Although the number of occurrences is very small (8 instances, counting (18) and discounting (17)), complement selection that is not regulated by the regular deletion process is found only in NP complements in the OED.Footnote 5

Progressing to the data in the COHA and GloWbE, I conducted a partial survey of the relevant data. Since because is the most frequently used causal subordinator (Lenker Reference Lenker2010: 134), a huge amount of effort is required to glean relevant examples (as in table 4). In the COHA, I searched up to the 500th hit of the search strings because [j*] and because [n*] (because immediately followed by adjectives and nouns); I also searched the string of because an to make a partial survey of NP complements beginning with a determiner.Footnote 6 The data search began on 20 August and ended on 15 September 2019.

The result shows that the same observation holds in the COHA (as far as the limited range of search is concerned) as in the OED. There are at least 201 instances of regular deletion processes with adjective complements (deleted subjects are identical to the subjects of main clauses in 136 instances, the objects of main clauses in 12 instances, and the oblique objects in 5 instances, with the other 48 being cases of coordination, as in (15a)). In the case of nominal complements, there are 10 instances in which the deleted subject is identical to the subject of the main clause and 1 consisting of the same construction with the oblique object of the main clause.

The number of relevant examples is, again, small in the category of nominals, in comparison to that of adjectives, but the important point to note is that instances of unregulated complements are, again, verified only among nominals (15 instances in total, with 2 in the nineteenth, 11 in the twentieth and 2 in the twenty-first century).Footnote 7

(19)

(a) In the constitution of the judiciary department in particular, it might be inexpedient to insist rigorously on the principle: first, because peculiar qualifications being essential in the members, the primary consideration ought to be to select that mode of choice which best secures these qualifications … (COHA 1817: non-fiction)

(b) Orders for the buying and selling of gold by private persons converge upon

London because London 13 the greatest free market, for gold.

(COHA 1938: news)

Next, in the GloWbE (accessed from 16 to 24 September 2019) I found adjectival complements in the database beyond the range of the regular deletion process in addition to nominal ones. Regarding adjective complements, I only searched the string because [j*] ./,/;/: which returned 458 instances in which these complements were somehow separated from the co-text by punctuation marks. As expected, several cases with the regular deletion process were found (coordinate uses, as in (15a), included). In addition, there were some instances in which the regular deletion process did not apply.

(20)

(a) We always prided ourselves on performing live, records never lived up to the

band live and it's one of those things where you had to see it, to get the full jist

of it. That's why bands like INXS and AC/DC broke through, because of that

work ethic and because [they performed] live, they were unbelievable. (GloWbE Australia: blog)

(b) Because [we were] thirsty, God created water; because [we were in] the

darkness, God created the fire; because I need a friend, so God sent you here for

me, … (GloWbE Hong Kong: blog)

Regarding nominal complements, the yield of the search string because [n*] (295 instances) was adequate for gathering cases of free selection of complements. I have only listed a portion of the nominals used in the context specified by the search string.

(21) because science/ reasons/ comedy/ school/ politics/ socialism/ statistics/

privilege/ racism/ rain/ management/ unawareness/ religion/ sadness/ bankruptcy/

agony/ family/ fascism/ innocence/ deficit/ obesity/ Olympics/ paradoxes …

The list in (21) illustrates that bare nominals were productively employed in the register of web-based English quite recently, and the transition from (16) to (19) to (21) also shows that bare nominals were used in the later stage of the development of because X. At first, the nominals were essentially combined with some modifier and/or determiner, comprising phrasal constituents. The data also show that adjective complements that are not controlled by the regular deletion process are recent innovations. Much time passed before the free selection of complements extended from nominals (the most frequent type in table 1) to the second-most frequent lexical category of adjectives (disregarding the compressed clauses in table 1). This late extension illustrates that the category-free variation in because X is relatively new. Because X was limited to nominal expressions for several centuries when examples of regular deletion processes were discounted.

3 In case X

Next, we move on to examining new innovations following the example of because X, namely, in case X, a phrase that seems to have been gaining popularity recently. In case X also has two input structures, namely, in case S and in case of NP. The mixture of the inputs is not employed in the standard usage of English. Therefore, the GloWbE and Corpus of News on the Web (NOW; Davies Reference Davies2013b) were studied in an effort to gather a corpus of English expressions used on the internet.

The NOW (consisting of 6.2 billion words as of May 2018) consists of English expressions in web-based newspapers and magazines from 2010 to the present, and it also contains data from the same twenty countries as the GloWbE. The specific change with which we are concerned is happening in many parts of the English-speaking world, and it is almost exclusively found in informal registers.

According to Bohmann (Reference Bohmann and Squires2016: 170), ‘[t]he assumption that the two most central varieties in the world system of Englishes (the USA and the UK) might be leading the innovative development in because-complementation is not borne out’ and ‘[i]t seems that this area (South and Southeast Asia) is a particularly productive locale for because X’. In order to get an overview of the current state of this new change, the data search must be extended beyond the border of Kachru's ‘inner circle’ (Bolton Reference Bolton, Kachru, Yamuna and Nelson2006: 292). Thus, the GloWbE and NOW are, I believe, a good combination of databases for this research at present. The search for in case X began on 3 April and ended on 11 May 2018.

First, we list some instances of in case X.Footnote 8

(22) in case NP/gerund (53 tokens found)

(a) In case your wondering, the one nugget of general knowledge Kajen did have was that Ursus Maritimus is the scientific name for a polar bear. (NOW Great Britain)

(b) Log files are very important from Exchange Server database perspective. It helps in recovering data in case corruption in EDB file. (NOW Canada)

(c) The prime objective of road safety drive was to ensure timely and prompt response by drivers in case fire after an accident before the arrival of emergency services. (NOW Pakistan)

(d) ‘By the same provision, the council has got incidental, subsidiary and implied power to suspend and cancel enrolment in case violation or misconduct’, the judge said. (NOW India)

(23) in case ADVERB/polarity items (25 tokens found)

(a) By now the marginalization of women in larger left struggles should be hackneyed information, but in case not, here is a broad stroke to remind you …

(GloWbE United States: general)

(b) Please check whether you have entered the correct code, account number and/or name. In case yes, the name may not be matching as per the record in epfo. In such case the member has to contact the concerned epfo office. (GloWbE India: general)

(c) Persons claiming to be the owners of these plots have been urged to immediately contact the Urban Planning Specialist, LDA, if they possess ownership documents of any of these plots. LDA will sale these plots through open auction and no excuse will be entertained afterwards, in case otherwise. (NOW Pakistan)

Based on the data in (22), it may appear to be a simple truncation of the preposition of. However, (23) shows that the truncation analysis does not work because the complements in these examples do not belong to the lexical categories selected by prepositions.

(24) in case VERB/participle (10 tokens found)

(a) In case forget words and phrases about the point don't end up being anxiety and perplexed. (GloWbE Great Britain: blog)

(b) if im [sic] her, i would just continue enjoying life. Maybe hire two bodyguards in case get harassed by crazy public … (GloWbE Singapore: general)

(c) you should also buy things for the dog to play and in case need to go potty when your [sic] not at home. (GloWbE Great Britain: general)

(d) Musk tweeted early Saturday that he was working with a team from his Space X rocket company to build a ‘tiny kid-size submarine’ to transport the children. But Saturday night, he tweeted that the cave was now closed for the rescue by divers. ‘Will continue testing in LA in case needed later or somewhere else in the future’, he wrote. (NOW United States)

As for (24a–b), it would be reasonable to assume that the subject arguments are simply omitted, namely, you in (24a) and i in (24b). However, (24c) is not a case of simple omission of the subject because the subject should be your dog, which would trigger the inflection of the complement verb into needs. The in case phrase in (24d) may be extended to in case (the submarine is) needed. The deleted subject in this example is only recoverable from outside the sentence in question.

(25) in case ADJECTIVE (4 tokens found)Footnote 9

(a) Earthquake is unpredictable. Up to date, no human knowledge and invention is able to predict when it will happen. Scientists believed that animals are able to … but no solid proof as far as my knowledge concerns. In case true, the communication between human and animals is another hard puzzle. (GloWbE Philippines: blog)

(b) Arms are to be kept against the barrier whilst one gradually slides them upwards on top of the head, in case doable; if not, to a height that one is comfortable with.

(GloWbE India: general)

The evoked proposition of (25a) would be in case it (that animals can predict when an earthquake will happen) is true. In (25b), an appropriate proposition that could be evoked from the context would be in case the movement is doable. The missing subjects are not present as arguments in the main clauses.

The most frequent of all these deviant expressions with in case is in case your wondering, which appears 36 times in the present database. This phrase is phonetically equivalent to the clause you're wondering. We also find multiple occurrences of in case not/yes in the database. However, these phrases do not appear in the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies Reference Davies2008–) (as of 10 July 2018).

As for in case X, no instance was found in the OED.Footnote 10 Very few instances were found in the BNC, COCA and COHA (as of 20 August 2018). In case not appears twice in the BNC. In case + nominal complement appears in three instances: in case a crash (COCA, COHA), just in case Santa Claus (COCA) and in case mutiny (COHA). All of them were rejected by four native speakers who considered them improper usage. The COHA includes two instances (of the same structure in the same text) in which a past participle follows: in case refused to be paid upon the lawfiil demand of the ensuing Governour, which is a citation from an article written in Plymouth in 1633. While in case X occasionally appears in these databases, the number of instances is extremely small. This seems to indicate that in case X is a later development than because X.

The category variation found in in case X in (22)–(25) is very much like the variation observed in because X. The similar feature of the two new structures, in contrast to other causal adjuncts, is that they both have two underlying input structures. As will be demonstrated in the next section, other causal adjuncts also truncate the final prepositions in colloquial registers, but they do not seem to go beyond the bounds of simple truncation. Their complements are essentially restricted to noun phrases and gerunds. The important thing to note in this regard is that they do not have corresponding input structures to generate a new one formed by subordinator + X.

4 Other causal adjunct phrases

4.1 Frequency of occurrence

Aside from because of and in case of, we have several causal adjunct phrases to examine. We will determine whether the same kind of new usage is evident regarding such phrases. Beforehand, we need to check the token frequency of causal phrases in the BNC, COCA, GloWbE and NOW (as of 6 August 2018). The result is shown in table 4 in section 2.3.

Table 4. Token frequency of causal adjunct phrases

The adverbial phrases in the table are listed in the English Thesaurus of Lexico.com as synonyms of because of and in spite of. Adverbials of cause and concession are listed in the table, but some of the entries in the dictionary do not appear in it. Thanks to appears in many constructions (give/say thanks to~, many thanks to~, no thanks to~, express one's thanks to~, etc.), and it is difficult to filter out the frequency of the causal adjunct usage. Moreover, thanks X (a truncated version of thanks to) contains many cases in which X is counted as a vocative phrase rather than a complement, especially when X is a proper name. The segregation of the two uses is extremely difficult, so I decided to exclude this phrase from this research. As for phrases like in the face of, in the wake of, due to, for all and regardless of, they are used not only in the causal interpretation but also in some other readings, such as location or temporal order, meaning that filtering out the causal reading is, again, extremely difficult. Despite and notwithstanding are not counted either because they do not have alternative versions of truncation from the start. I only picked out causal phrases that consisted of more than two words, ended in a preposition, and had an unambiguous causal usage.

If frequency of use is the driving force of the new construction (Hopper & Traugott Reference Hopper and Traugott2003; Bybee Reference Bybee2007) omitting of from because of, a change should appear in as a result of or in spite of earlier than in case of because these two phrases are more frequently used in all four corpora. However, the two frequently used phrases in question do not show the same kind of innovation as far as the relevant corpora are concerned. I conducted a survey of the GloWbE and NOW (from 2 March to 13 September 2018) with regard to three causal adjuncts that have closer token frequency to in case of, namely, by virtue of, owing to and on account of, in addition to the two more frequently used phrases mentioned earlier. All five phrases have alternative versions in which the final prepositions are truncated, but their complements are not expanded to include elements of categories other than nominals.

For instance, in regard to in spite of, I searched the strings in spite [n*] (noun), in spite [v*] (verb), in spite [j*] (adjective) and in spite [r*] (adverb) in the two corpora; I also checked the complement nominals with articles by searching the string in spite a/an/the. The same procedure was conducted with all five adjunct phrases in question.Footnote 11

The database that was consulted contained many typographical and grammatical errors, so there are some sporadic exceptions in which elements of other categories are located in the complement of truncated adverbial phrases, but they are very likely to be deviant not only in the selection of the complements but also in other respects. In my experience, it was extremely difficult to find an example in which the surrounding text was without serious faults and the only conspicuous deviance found pertained to the selection of the complement of truncated causal adjuncts.Footnote 12

For instance, I could not find strings such as as a result yes, in spite no, owing happy or on account do the best in the database. It is intriguing that this change is widely evident in because and is now also beginning to be found in in case, yet it is excluded from more frequently used phrases, such as as a result of and in spite of. The existence of the underlying input structures is the key to differentiating between the two groups of phrases.

As a caveat to the discussion in this subsection, it may be possible to assume that because X and in case X are derived through omission of elements from a sentential complement and that the new structure is verified only in these two expressions because other causal phrases do not have an input structure taking a sentential complement from the beginning. One of the problems with this stance is that we must explain why nominals are predominantly selected as remnants rather than verbs or other categories. Verbs should be more frequently selected as the remnants because the type of event or action involved in the deleted proposition is determined by the predicate rather than by its arguments. The historical development presented in section 2.3 also requires explanation. Why is it the case that the output of sentential deletion was limited to the NP category for centuries? It is also necessary to explain how to derive the structures in (9), which cannot be derived from the regular deletion format in subordinate clauses, as in (11). We must formalize the deletion rule producing because X from clausal complements, but this is not an easy task in the presence of this extremely broad range of remnants. An additional problem is that the truncation of prepositions is not limited to because of and in case of but to other causal adjuncts as well. It seems reasonable to deal with the problem in relation to the truncation of prepositions.

4.2 Simple truncation of prepositions

As suggested in the preceding subsection, all five adjunct phrases have variants in which the final prepositions are simply truncated. For instance, the search string in spite a/an/the in the NOW (as of 25 April 2018) yields a total of 238 instances of of deletion. The breakdown of instances is as follows: Nigeria, 141; India, 22; the Philippines, 15; Ghana, 10; Pakistan, 8; Kenya, 7; Canada, 6; the United States, 5; Jamaica, 4; South Africa, Sri Lanka, Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand, 3; Singapore and Malaysia, 2; and Ireland, 1. This shows a skewed distribution; at the same time, the truncation is not limited to a specific region of the English-speaking world.

Here, we present instances of truncation regarding the four phrases under scrutiny (except as a result, which will be dealt with in detail in the following subsection). However, only one example for each of the phrases is listed due to space limitations.

(26)

(a) It reflects a strong labor market in spite a slowdown in economic expansion. (NOW New Zealand)Footnote 13

(b) The USA climb one place to 15th despite the defeat, albeit only by virtue the fact that Georgia suffered a last gasp 25-22 loss to Japan in the first meeting between the two sides on Georgian soil. (GloWbE New Zealand: blog)

(c) On the other hand much of Tuvalu will soon be underwater owing global warming, … (GloWbE New Zealand: general)

(d) It's regrettable in the last day or two, you know, I've been on the receiving end of some very strong personal attacks on account the work I'm doing on poker machine reform. (NOW Australia)Footnote 14

4.3 As a result (of)

As a result of exhibits high token frequency as a causal adjunct. What is most revealing regarding this phrase is that the string as a result is used in two ways, and the usages designate the opposite causal relations between the relevant propositions.

The first usage is the simple truncation of the final preposition, just as in the other four causal phrases. The breakdown of the instances in the present database is as follows: Nigeria, 58; the United States, 30; Great Britain, 26; Ireland, 20; South Africa, 18; Canada, 17; Australia, 16; Kenya, 12; Ghana, 11; New Zealand, 8; Sri Lanka and Malaysia, 5; Pakistan, India and Tanzania, 4; Hong Kong and the Philippines, 2; and Singapore, Bangladesh and Jamaica, 1. An example is given in (27).

The other usage of as a result is as a conjunctive adverbial phrase, which is most likely to be used in the sequence and as a result. In this usage, no element is omitted. An example is provided in (28).Footnote 15

(27) Hurley, from Cole Harbour, who was involved in coaching high school and minor sports, died as a result a collision with a pickup truck while he was cycling in July 2016. (NOW Canada)

(28) Airports carry out a significant amount of work to mitigate the risks of bird strikes, as a result serious incidents are fortunately very rare. (NOW Great Britain)

The interesting feature of these two usages is that the causal relations between the propositions are reversed. As a result (of) takes the cause of the causal relation as its complement, and the effect is expressed in the main clause, whereas the conjunctive phrase (and) as a result selects the effect of the causal relation as its subsequent.

The ambiguity of the causal relations expressed by the same linguistic expression can work against the development of the new usage of truncation. The conjunctive usage of (and) as a result is far more frequent than the other option, yet another way of looking at the situation is that the truncation is so prevalent in the specific registers that, even in cases in which the truncation leads to ambiguity in the new string, of is sometimes deleted. This phenomenon can be considered evidence of the productivity of the truncation process.

In parallel, a survey of as a consequence, another causal phrase similar in meaning to as a result, showed that most of the occurrences are conjunctive, with very few exceptions of truncation of of, as in (29).

(29) The death of a university worker as a consequence student protests received passing coverage compared with images of topless women protestors or tear-gassed students. (NOW South Africa)

In addition to as a consequence N, the truncation of the final preposition before a nominal complement is also observed with other adjunct phrases listed in table 4, except by dint of. The truncation process of the final preposition of causal adjunct phrases is highly productive. At the same time, why the widely seen truncation process does not yet lead to the next stage of category-free complement selection in these causal adjuncts, if we do not take into consideration the derivation process presented in figure 1, remains a mystery.

5 Summary

It does not appear that frequency of use is the driving force of this new structure because the new usage of category-free complement selection is observed in because X and in case X, skipping the intermediate phrases in token frequency. The important feature of this new change is the existence of underlying input structures taking NP complements and sentential complements.

During our discussion, we touched on the historical development of because X. The category-free selection of complements, unique to the innovative usage, can be traced to NP complements, buttressing the derivation process presented in figure 1. The plausibility of this derivation process explains the apparently disproportional skewing of the category selection observed in because X and in case X.

That said, the number of cases in which in case X is evident is still extremely small, and such usage may be considered a simple mistake on the part of speakers/writers. The important point to note, however, is that if such instances were mere mistakes, the same type of mistakes would be found more easily in frequently used causal phrases, such as as a result of or in spite of, which does not seem to be the case. The occurrence of mistakes in some specific contexts (but not in others) is telling, and there must be a reason for the unexpectedly uneven distribution of these mistakes. Mistakes can also change the linguistic norms of the future. As Bally (Reference Bally1952: 32) once said, ‘c'est la langue de demain qui se prépare dans une foule d'incorrections’ (it is the language of tomorrow that prepares itself in a mass of errors).

Truncated phrases like as a result X, in spite X and on account X also contain reference points in the complement, and it may be possible for them to loosen the category restriction of the complement analogically at any moment. As of now, however, this does not seem to be the case, and the difference seems to lie in the absence of underlying input structures in the case of the causal adjunct phrases that have been mentioned.

This change may have occurred as a case of mutation. Even if someone began to use this kind of phrase playfully (as Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 115) put it, ‘change starts in a relatively small corner of the system’), it has since gained precedence, and this construction must have had its own fertile ground. Otherwise, the new forms (or at least because X) would not have become entrenched in language (Langacker Reference Langacker2000: 3, Tomasello Reference Tomasello2003: 300). The emergence of these forms is not without reason.