English Language and Linguistics has reached volume 25. This kind of jubilee prompts reflection and we four current editors of the journal would like to take this opportunity to look back over its history a little, to consider how it has developed during its first quarter-century.

ELL's founding editors (Bas Aarts, David Denison and Richard Hogg) published an editors’ note in the first issue, back in 1997, setting out the plans for the journal. They wrote that ‘[t]he journal is concerned equally with the synchronic and the diachronic aspects of English language studies and will publish articles of the highest quality which make a substantial contribution to our understanding of the structure and development of the English language and which are informed by a knowledge and appreciation of linguistic theory.’ We hope and think that ELL remains true to these plans. We are entirely at the mercy of the authors submitting articles, of course (we do not give favour to any type of submission), but we are happy to say that a steady stream of work on both contemporary English and the history of the language has appeared in ELL's pages over the years, as we show below.

Things have, of course, changed somewhat. When ELL began, it published two issues per volume, with an average of 11 articles per year over the first five years of publication. This rose to three issues a year in 2007 (with an average of 18 articles published each year in the following five years) and four issues in 2019 (with 31 articles appearing in both 2019 and 2020). With the increase in the number of issues (and pages) in 2007, the practice of publishing Special Issues was regularised, and since then one issue a year has been thematic, gathering articles on a particular topic, edited by guest editors. We began issuing a ‘call for proposals’ for a year's Special Issue in 2015 to formalise this further and to make clear the process of how Special Issues are selected. Beginning in 2012, ELL was adopted as the official journal of the International Society for the Linguistics of English (ISLE). While this did not affect the publication practice of the journal, it is a nice recognition of its place at the heart of the English linguistics world.

While there has been some change, there has also been much stability at ELL. Some topics have been constant in articles appearing in the journal. If we compare both the first two years of ELL and its most recent two years, we can observe that articles appeared at both ends of ELL's first quarter-century, for example, on aspects of the mass/count noun distinction in contemporary English and on aspects of Middle English phonology. Indeed, while there have naturally been new topics appearing in ELL over the years, and also new approaches to linguistic analysis as frameworks to analyse data, a key observation in this piece (with one clear exception, to be addressed below) is that ELL has remained remarkably stable. The original recipe was good, and it is still good after these 25 years.

While ELL explicitly welcomes work on both historical and contemporary English, we wondered (when we began writing this piece) if there might have been a change in the proportions of the two types of research: has work on the history of English declined, for example? (It is not unusual to hear worries that work in historical linguistics is lessening.) This is not the case in ELL. Figure 1 shows the number of articles which address historical issues in the 24 preceding full years of publication, as a proportion of all the articles published in a year. While there has been natural fluctuation over the years, with some years overwhelmingly contemporary (e.g. 2013) and some overwhelmingly historical (e.g. 2017), the trend looks remarkably consistent. Over all 24 years together, the average is that 44.8 per cent of articles have a historical aspect. In the first volume, 38.5 per cent of articles were historical, while in the most recent volume the figure is 54.8 per cent, both figures hovering around the overall average.

Figure 1. Proportion of articles on historical topics in previous full years of publication in ELL

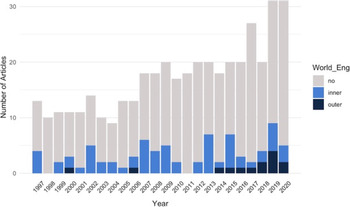

There are many other ways that we could consider the topics represented in ELL over the years, but we lack the space here to investigate this in fine detail. One further topic that we thought might be interesting is the extent to which the increasing interest in World Englishes has been reflected in the journal. As figure 2 shows, this is only very moderately the case. Articles addressing varieties of English in general, including dialectological and sociolinguistic studies, have always had a solid but modest presence in ELL (on average 20–30 per cent of articles per volume), but most of them have addressed inner-circle Englishes. Outer-circle Englishes have a regular presence only from 2014 onwards, ranging on a very modest level from one to four articles per volume.

Figure 2. Proportion of articles addressing varieties of English in previous full years of publication in ELL

To turn to a different aspect of content, ELL's founding editors announced in their editors’ note in the first issue that ‘[t]here will also be a major review section’. This is another area where there has been stability. The book review section has remained an important aspect of the journal throughout its history – indeed, we see ELL's review section as a crucial and distinctive aspect of the journal, spreading news of current research and research trends in a way that can be as important as the articles that appear in its pages. A review of 12 comparable journals in the field shows that ELL is the one with the highest number of reviews per issue and year. There were 13 book reviews in the first volume of ELL, and there were also, with remarkable (if coincidental) consistency, 13 book reviews in the latest full volume (ELL's 24th). This implies that monographs and edited books have retained a considerable importance in our field over the years, and show no sign of disappearing.

We conclude from the above that ELL has not changed fundamentally over its first quarter-century of publication in terms of its basic conception as a journal and in terms of the types of topics covered (at least, not in the ways that we have considered here). We were also, however, interested to analyse whether the authorship of the articles that have appeared in its pages has changed.

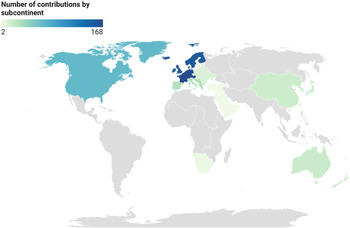

One obvious question to ask about ELL's authors is: where are they based? We considered this from two perspectives: overall (that is, if we take all the papers published up to this year, where have authors been based?), and diachronically (that is, have things changed in terms of geography over the years?). Over all complete previous volumes, ELL has published 413 articles, and their authors are spread over a wide range of countries where English is studied. Figure 3 shows the global distribution of authors in terms of subcontinental units.

Figure 3. Distribution of ELL authors around the world in terms of subcontinental units (based on university affiliation)

ELL has always had the strongest representation of authors from the UK and other parts of broadly northern Europe, as is clear in figure 3. This has remained unchanged over the years, as shown in figure 4, which gives the number of articles published in previous volumes, analysed in terms of the continents of authors’ universities (with Europe split into smaller areas, showing something of a rise in articles from central Europe). Contributions from authors in Australasia and Asia are of low frequency but steady, while the number of North American authors has declined by about one-third in the past decade, perhaps because publication in general linguistics journals is more the norm in North America. We are naturally keen to receive articles for review from anywhere in the world and we encourage submissions from those areas which have traditionally not been so frequently represented in the journal.

Figure 4. Number of articles by continent of authors’ universities in previous full years of publication in ELL

Another obvious variable to consider is the gender of authors (at least, to the extent that this can be judged according to authors’ names). We recognise that gender is more complex in reality than we treat it here, but in order to get an approximation of how things have been over the years, figure 5 shows the proportion of articles in previous full volumes of ELL which feature an author with a classically female first name. On this basis, authorship has always been fairly well balanced for gender in ELL, although there has been an overall increase of female contributors over the last 10 years, at levels consistently higher than 50 per cent, showing a progressive consolidation of the presence of women in the field of English linguistics.

Figure 5. Number of articles with female authors in previous full years of publication in ELL

We also wondered whether the number of authors per article might have changed over the years. There are reasons to think that this might be the case: it has been claimed that we are living through a ‘quantitative turn’ in linguistics, which may make our discipline more like the hard sciences, where multiple authorship is common. Figure 6 presents evidence on this question, showing the number of articles in each volume which are single-authored, have two authors, or have three or more authors. While there might be a slight increase in multiple authorship, once again, there has largely been stability in this area. The year 2020 shows an unusually high number of articles with three or more authors (19.4 per cent, which is notably higher than any other year, except perhaps 2013, with 15 per cent), and this may be the start of a trend, but 2019 was distinctly comparable with 1997, with 87.1 and 84.6 per cent single-authored articles respectively. It is clear that the single-author paradigm is still robust in our field, although there has also always been collaboration.

Figure 6. Proportion of articles in previous full years of publication in ELL, distinguished in terms of number of authors

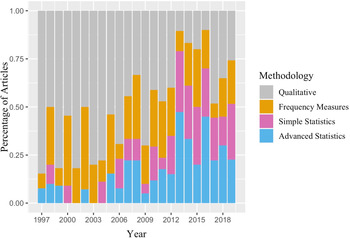

Finally in this piece, we consider whether there has been a quantitative turn in the field. We can confirm that there has. This is one area where there clearly has been change over the years in the articles appearing in ELL, as can be seen in figures 7 and 8. These figures categorise all articles published in ELL before 2020 in terms of their methodologies, based on four overarching types:

‘qualitative’ The article uses no quantitative methods. It is purely qualitative.

‘frequency’ The article reports descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, or relative frequency. The vast majority of these articles are corpus-based and report frequency counts.

‘simple’ The article compares tables or means without modelling, using Chi-squared tests, t-tests, Mann–Whitney tests, and similar methods.

‘advanced’ The article uses more complex statistical modelling (e.g. linear or logistic regression, mixed-effects models, random forests, variable rules analysis).

Figure 7. Proportion of all four methodological categories in previous full years of publication in ELL, to 2019

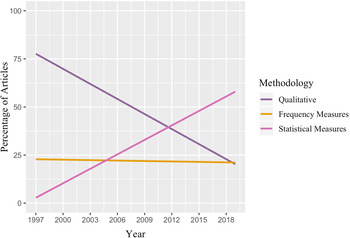

Figure 8. Linear regression lines for qualitative methodologies compared to frequency-based and statistical methodologies in previous full years of publication in ELL, to 2019

The bar graph in figure 7 shows the percentage of the total articles by year for these four categories. The proportion of qualitative articles per volume has strongly decreased (from some 75 to less than 25 per cent), and the proportions of articles using simple statistics and, even more strongly, advanced statistics have steadily increased (ending up between 25 and 30 per cent each), while the proportion of ‘frequency’-type articles has remained fairly stable (at a level slightly below the 25 per cent mark). The figures in the last three years imply that there might be a levelling-off in the change, but the overall impression is clear: the quantitative turn in English linguistics is real.

Figure 8 shows this unambiguously. Simple and advanced models have been collapsed into one category in this figure (‘statistical’), and are plotted against ‘frequency’ and ‘qualitative’ work to see how the use of statistical measures overall compares to articles reporting frequency counts and qualitative works.

English linguistics was the front-runner in developing corpora, annotation techniques and appropriate corpus-linguistic methodology, and the foundation of ELL in 1997 occurred at a time which can be characterised as the beginning and formative years of the quantitative turn in linguistics, which most likely explains this change. In line with this development, ELL appointed a statistics consultant in 2018 to ensure that advanced statistical methods are reviewed appropriately. We expect that such statistically informed work will retain the place that it has achieved in the pages of the journal, likely not completely replacing, but sitting alongside work from areas of the field where the use of statistics is not helpful. ELL remains very much open to research in all kinds of linguistic approaches.

To conclude, we are happy to report that ELL is in excellent health after 25 years. Much in the journal has remained relatively stable over the past quarter-century of publication, but it has steadily grown in size over the years, and has adapted to new methodologies. We are proud to work as editors for ELL. We are excited by the prospect that readers will continue to submit work of such high quality and we look forward to ever new advances in our understanding of the structure and development of English.