In addition to the good, the bad, and the neutral, there is an overlooked fourth category of absolute value. This category provides, I shall argue, a way to avoid a number of problematic conclusions in population ethics which are not only counter-intuitive but also morally repugnant. The possibility of this overlooked category enables a new variation of Total Utilitarianism, which avoids repugnance not only in the aggregation of the value of lives in populations but also in the aggregation of the value of different moments within a life. In this way, it delivers a population axiology without repugnance.

Before we begin, however, we need to introduce some terminology. A population is a set of all lives within a possible world. The well-being level of a life is the personal value for the person living it, and we assume that personal value is interpersonally measurable. Categories of absolute well-being correspond, accordingly, to categories of absolute personal value. So, for example,

A good (bad, neutral) well-being level is a well-being level such that a life at that level would be good (bad, neutral) for the person living it.Footnote 1

The most straightforward population axiology is perhaps Total Utilitarianism. Let the total value of a population X be

where w(l) is the well-being level of life l with zero representing the neutral well-being level. According to

Total Utilitarianism

A population X is at least good as a population Y if and only if the total value of X is at least as great as the total value of Y.

Total utilitarianism has a counter-intuitive implication known as the Repugnant Conclusion. The following is Derek Parfit’s canonical formulation:

The Repugnant Conclusion (canonical formulation)

For any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better, even though its members have lives that are barely worth living.Footnote 2

This conclusion is often put in terms of a comparison between an A population – a large population consisting of lives that are very good for the people who live them – and a Z population – an enormous population consisting of lives that are barely worth living. In the following diagram, the populations are represented by boxes, where the width represents the size of the population and the height represents the well-being level of the lives in the population. The dashed part of the Z box indicates that it can be thought of as having a much larger size (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The canonical formulation talks about lives that are ‘barely worth living’. This can plausibly be read in at least two ways.Footnote 3 On a first reading, these are lives at a well-being level only marginally higher than some bad well-being level. This reading would be

The Repugnant Conclusion (barely-not-bad version)

Each population consisting of lives at a very good well-being level is worse than some population consisting of lives at a well-being level that is just marginally higher than some bad well-being level.Footnote 4

On a second reading, these are lives at a well-being level that is just marginally higher than some well-being level that isn’t good. That reading would be

The Repugnant Conclusion (barely-good version)

Each population consisting of lives at a very good well-being level is worse than some population consisting of lives at a well-being level that is just marginally higher than some well-being level that is not good.

The difference between these two versions is of little importance if we assume

The Personal Absolute Trichotomy Thesis

For every well-being level, exactly one of the following holds: (i) it is a good well-being level, (ii) it is a bad well-being level, or (iii) it is a neutral well-being level.

That is, a life is good, bad, or neutral for the person living it. This is an instance of a more general view, which we can call

The Absolute Trichotomy Thesis

For every value bearer, exactly one of the following holds: (i) it is good, (ii) it is bad, or (iii) it is neutral.Footnote 5

While the Absolute Trichotomy Thesis is standard, we shall lift these assumptions later on.

1. Critical-Level Utilitarianism

Critical-Level Utilitarianism is a family of ethical theories which generalizes Total Utilitarianism. It does this by replacing total value with critical total value, which is relative to a certain critical well-being level. We calculate the critical total value of a population by first subtracting the critical level from the well-being level of each life in the population and then the critical total value is the sum total of these differences. Equivalently, in mathematical notation, we let the critical total value of a population X relative to a certain critical well-being level w be

where again w(l) is the well-being level of life l. This generalization makes it possible to avoid the Repugnant Conclusion. According to

Critical-Level Utilitarianism

A population X is better than (equally good as) a population Y if and only if the critical total value of X relative to the critical level w is greater than (equal to) the critical total value of Y relative to w.Footnote 6

To avoid the Repugnant Conclusion with this approach, we just need a critical level sufficiently higher than the neutral level so that it’s unrepugnant that a very large population where everyone has a level of well-being barely above the critical level is better than a smaller population where everyone has very high well-being. This gain, however, comes at a price: If the critical level is higher than the neutral level with some margin (so that it is also higher than at least one good well-being level), Critical-Level Utilitarianism entails

The Sadistic Conclusion

Each population consisting of lives at bad well-being levels is better than some population consisting of lives at good well-being levels.Footnote 7

The Sadistic Conclusion seems at least as repugnant as the Repugnant Conclusion. And the Sadistic Conclusion follows from Critical-Level Utilitarianism if there is a good well-being level below the critical level, because, if there is, one can make an arbitrarily bad population by increasing the size of a population in which everyone has this level of well-being. To see this, compare a mirrored, bad variant of the A population where everyone has a life that’s very bad for them, which we can call Bad A, and the Z population, which consists of lives at a good well-being level below the critical level (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Regardless of how bad Bad A is, we can make Z even worse by making it sufficiently large, because each life in Z reduces the value of Z by the same amount. So, to avoid the Sadistic Conclusion, we need a bad or almost neutral critical level. But, with a bad or almost neutral critical level, we again get the Repugnant Conclusion. Hence we are stuck with either the Repugnant Conclusion or the Sadistic Conclusion.

There are also mirrored variants of the Repugnant Conclusion and the Sadistic Conclusion. These variants are like mirror images, where ‘good’ has been replaced with ‘bad’, ‘bad’ with ‘good’, ‘better’ with ‘worse’, and ‘worse’ with ‘better’:

The Mirrored Repugnant Conclusion (barely-not-good version)

Each population consisting of lives at a very bad well-being level is better than some population consisting of lives at a well-being level that is marginally lower than a good well-being level.Footnote 8

The Mirrored Sadistic Conclusion

Each population consisting of lives at good well-being levels is worse than some population consisting of lives at bad well-being levels.

Unless the critical level is sufficiently lower than the neutral level, Critical-Level Utilitarianism entails the Mirrored Repugnant Conclusion. And, if the critical level is lower than the neutral level with some margin so that it is lower than at least one bad well-being level, then Critical-Level Utilitarianism entails the Mirrored Sadistic Conclusion. Therefore, for any version of Critical-Level Utilitarianism, either it entails the Mirrored Repugnant Conclusion or it entails the Mirrored Sadistic Conclusion. Hence any version of Critical-Level Utilitarianism entails at least two of the mirrored and non-mirrored variants of the Repugnant and Sadistic Conclusions. So, to avoid repugnance, we need to revise Total Utilitarianism in some other way.

2. Standard Critical-Range Utilitarianism

An alternative approach that can avoid all of these counter-intuitive implications is Critical-Range Utilitarianism. A basic assumption of both Total and Critical-Level Utilitarianism is that there is a single well-being level of neutral contributive value – that is, a single well-being level such that adding a life at that level leaves the value of the population unchanged. Critical-Range Utilitarianism drops this assumption. The basic idea is that there is a critical range of two or more well-being levels such that additions of lives at a well-being level in this range will, other things being equal, make the resulting population incomparable with the original population. According to

Critical-Range Utilitarianism

A population X is better than (equally good as) a population Y if and only if, for all well-being levels w in the critical range, the critical total value of X relative to w is greater than (equal to) the critical total value of Y relative to w.Footnote 9

On this view, one compares two populations X and Y by calculating, for each well-being level in the critical range, how Critical-Level Utilitarianism would evaluate X and Y if this well-being level were the critical level. If Critical-Level Utilitarianism would yield that X is better than Y regardless of which level in the critical range were the critical level, then X is better than Y. If, on the other hand, whether Critical-Level Utilitarianism would yield that X is better than Y depends on which level in the critical range were the critical level, then X and Y are incomparable, that is, X is not at least as good as Y and Y is not at least as good as X.

Critical-Range Utilitarianism avoids both the Repugnant Conclusion and the Mirrored Sadistic Conclusion if the upper bound of the critical range is sufficiently higher than the neutral level. And it avoids the Mirrored Repugnant Conclusion and the Sadistic Conclusion if the lower bound of the critical range is sufficiently lower than the neutral level. So, given a critical range with an upper bound sufficiently higher than the neutral level and a lower bound sufficiently lower than the neutral level, we avoid each of the Repugnant Conclusion, the Sadistic Conclusion, and their mirrored variants. We can call this kind of Critical-Range Utilitarianism

Standard Critical-Range Utilitarianism

Critical-Range Utilitarianism with a critical range that includes the neutral well-being level and a range of good and bad well-being levels.

While Standard Critical-Range Utilitarianism can avoid the Repugnant Conclusion and its mirrored variant, it still has some counter-intuitive implications. It entails two weakened variants of the Sadistic Conclusion and its mirrored variant. These weakened variants are just like the originals except that ‘better than’ has been replaced with ‘not worse than’ and ‘worse than’ with ‘not better than’:

The Weak Sadistic Conclusion

Each population consisting of lives at bad well-being levels is not worse than some population consisting of lives at good well-being levels.

The Weak Mirrored Sadistic Conclusion

Each population consisting of lives at good well-being levels is not better than some population consisting of lives at bad well-being levels.

It seems that any population consisting of lives at good well-being levels is better than any population consisting of lives at bad well-being levels. To see that Standard Critical-Range Utilitarianism entails the Weak Sadistic Conclusion, compare again the Bad A and Z, where Z consists of lives at a good well-being level in the critical range such that there is at least one higher level in the range (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

No matter which well-being level the lives in Bad A are at, we can make Z sufficiently large so that, for some well-being level in the critical range, the critical total value relative to that level is lesser for Z than for Bad A; and then Bad A isn’t worse than Z. Therefore, Standard Critical-Range Utilitarianism entails the Weak Sadistic Conclusion. And – by an analogous argument comparing A with a mirrored, bad variant of Z consisting of lives at a bad well-being level in the critical range such that the range includes at least one lower level – we have that Standard Critical-Range Utilitarianism entails the Weak Mirrored Sadistic Conclusion.

As Wlodek Rabinowicz points out, we get these weakened sadistic conclusions because we have given up

The Equivalence of Personal and Contributive Value

The addition of a life, other things being equal,

makes a population better if and only if the life is at a good well-being level,

makes a population worse if and only if the life is at a bad well-being level, and

leaves the value of the population unchanged if and only if the life is at a neutral well-being level.Footnote 10

One of the main attractions of Total Utilitarianism is that it satisfies this equivalence, which is how it avoids each of these sadistic conclusions. In addition to avoiding these sadistic conclusions, there’s a further reason why the equivalence of personal and contributive value is a desideratum: If this principle were false, we would need some other explanation for why a person’s life makes the world better (worse) than the straightforward one that that life is good (bad) for that person.

3. Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism

Critical-Range Utilitarianism is incompatible with the equivalence of personal and contributive value if there’s only one well-being level that is neither good nor bad. Even so, Critical-Range Utilitarianism could be compatible with this equivalence if multiple well-being levels were neither good nor bad.Footnote 11 The existence of two or more such levels is ruled out by the Personal Absolute Trichotomy Thesis and the more general Absolute Trichotomy Thesis.

These theses, however, are challenged by a recent development in the logic of value. There are reasons to believe that, in addition to good, bad, and neutral value bearers, there’s a fourth category of value bearers. These value bearers are undistinguished:

Something is undistinguished if and only if it is a value bearer and not good, not bad, and not neutral.Footnote 12

If we accept the possibility of value incomparability – which we must if we accept Critical-Range Utilitarianism – then it seems that something neutral could be incomparable with something else. Consider the following standard principles for the logic of value:Footnote 13

(1) If x is neutral, then: y is good if and only if y is better than x.

(2) If x is neutral, then: y is bad if and only if y is worse than x.

(3) If x is neutral, then: y is neutral if and only if y is equally good as x.

Then suppose that a first, neutral thing is incomparable with a second value bearer. By (1), the second value bearer cannot be good, because, if it were good, it would have been better than the first. By (2), it cannot be bad, because, if it were bad, it would have been worse than the first. And, by (3), it cannot be neutral, because, if it were neutral, it would have been equally good as the first. So the second value bearer must be undistinguished.Footnote 14 Hence

(4) If x is neutral, then: y is undistinguished if and only if y is incomparable with x.

Our characterization of something’s being undistinguished is mostly negative, in the sense that it mainly states what properties the thing lacks, that is, the thing’s not belonging to one of the other categories of absolute value. This lack of a more informative, positive characterization might come across as a weakness. But note that undistinguishedness is supposed to correspond to value incomparability, just like goodness corresponds to betterness, badness corresponds to worseness, and neutrality corresponds to equality in value in the manner outlined by (1)–(4).Footnote 15 So, given that value incomparability is characterized negatively, it seems that the corresponding absolute category should be so too.

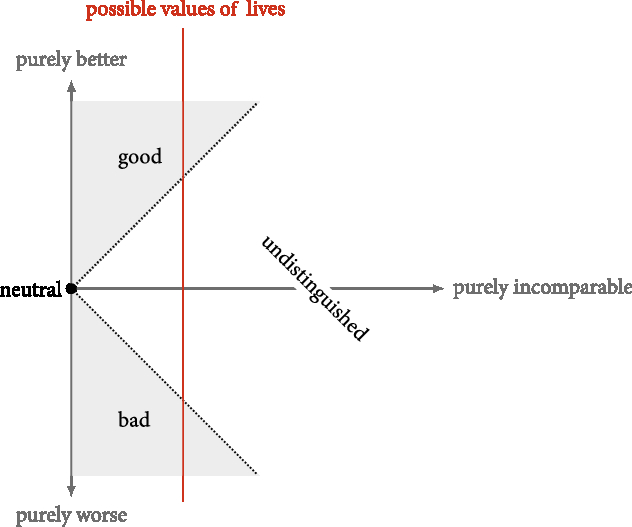

It may be objected that there it is still unsatisfactory that either of incomparability and undistinguishedness is characterized negatively. My arguments, however, do not depend on there being no positive characterization of undistinguishedness. While I won’t provide a positive characterization, some of the mystery of undistinguishedness can be cleared by looking at how incomparability functions in the overall structure of value. The standard picture of value without incomparability looks like this (Figure 4):

Figure 4.

On this picture, there is a single dimension of value, along which different points differ in goodness. All points along the goodness dimension are comparable. So, if there is incomparability, there has to be a further dimension (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Points along the new dimension that is orthogonal to the goodness dimension differ in undistinguishedness. Note that the pure value relations only cover points that only differ in one of the two dimensions. Let a point be better (worse) than another point if and only if it has more (less) pure goodness and the difference in pure goodness is greater than the difference in pure undistinguishedness. Let a point be equally good as another point if and only if it has the same amount of pure goodness and the same amount of pure undistinguishedness (that is, if it is the same point). And let a point be incomparable with another point if and only if the points differ in pure undistinguishedness and the difference in pure undistinguishedness is at least as great as the difference in pure goodness. We get the following kind of picture (Figure 6):Footnote 16

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

The neutral point is a point with no (positive or negative) goodness and no undistinguishedness. While the goodness dimension has a negative extension – that is, the range of badness – we do not need to assume (for the purposes of our discussion) that there is a negative extension of the undistinguishedness dimension.Footnote 17

By comparing points to the neutral point in this manner, we get the following picture of absolute value (Figure 7):

Given this fourth category of absolute value, we also have a fourth category of absolute well-being:

An undistinguished well-being level is a well-being level such that a life at that level would be undistinguished for the person living it.

The possibility of undistinguished well-being levels allows for a critical range consisting of well-being levels that are neither good nor bad.Footnote 18 One cannot have a critical range consisting of two or more neutral levels. Given completeness, if two well-being levels are distinct, it must be better for a person to have a life at one of these levels than to have a life at the other level. But, by (3), if both of these levels are neutral, it must be equally good for a person to have a life at either of these levels. Thus there cannot be two or more neutral well-being levels. There can, however, be multiple undistinguished well-being levels. The main difference between value incomparability and equality in value is that, if two things are equally good, any improvement (deterioration) of one of them would make it better (worse) than the other. If, on the other hand, two things are incomparable, there should be some improvement or deterioration of one of the things such that it wouldn’t make the thing better or worse than the other thing.Footnote 19 Analogously, the main difference between neutrality and undistinguishedness is that, if something is neutral, any improvement (deterioration) of that thing would make it good (bad). But, if something is undistinguished, there should be some improvement or deterioration that wouldn’t make it good or bad. So, even if something undistinguished is better than some other things, those other things might also be undistinguished. Hence, unlike a range of neutral well-being levels, there doesn’t seem to be anything inconsistent about a range of undistinguished well-being levels.

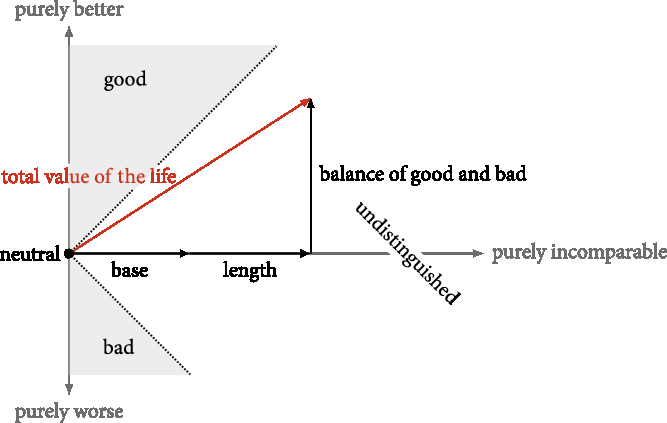

The idea is that all lives have a certain amount of undistinguishedness. In terms of a two-dimensional vector diagram of well-being levels, all possible lives would have a personal value that is shifted slightly to the right of the standard, complete well-being scale (Figure 8):

Figure 8.

This shift of the possible values of lives creates the undistinguished range of well-being levels between the good and bad well-being levels.Footnote 20

This possibility of an undistinguished range of well-being levels enables the following version of Critical-Range Utilitarianism:

Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism

A version of Critical-Range Utilitarianism where the well-being levels in the critical range are undistinguished, the levels above the range are good, and the levels below the range are bad.

Unlike Standard Critical-Range Utilitarianism, Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism avoids the Weak Sadistic Conclusion and its mirrored variant. Just like Total Utilitarianism, it avoids them because it satisfies the equivalence of personal and contributive value. And, given that the critical range is sufficiently wide, Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism also avoids the barely-not-bad version of the Repugnant Conclusion and the barely-not-good version of the Mirrored Repugnant Conclusion.

Rabinowicz has proposed a similar version of Critical-Range Utilitarianism with a critical range of personal value, which he argues can avoid the barely-not-bad version of the Repugnant Conclusion.Footnote 21 The main difference between Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism and Rabinowicz’s theory is the underlying theory of value. The two-dimensional theory of goodness and undistinguishedness provides an account of how there is a gap between the worst good lives and the best bad lives and why there is no neutral life. Rabinowicz’s version of the theory, on the other hand, allows that there could be neutral lives.Footnote 22 This difference will matter in the next section.

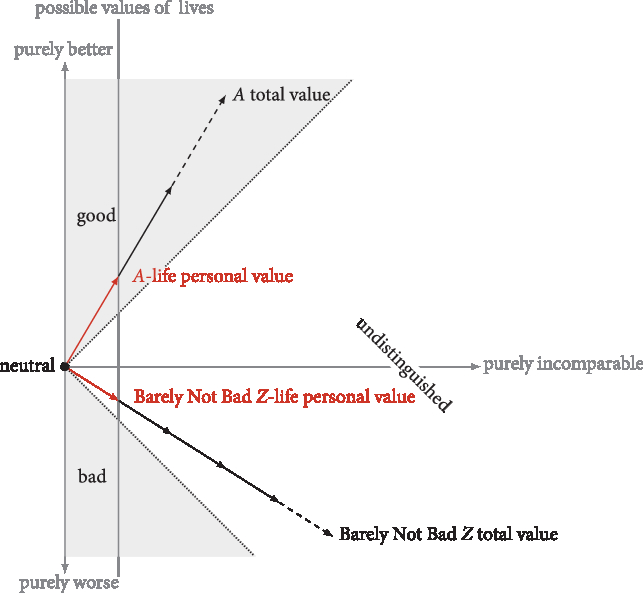

For an illustration of how Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism avoids the barely-not-bad version of the Repugnant Conclusion, consider the following two-dimensional vector diagram (Figure 9):

Figure 9.

Just like Total Utilitarianism, Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism evaluates populations by their total personal value. The difference is that Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism deals with two-dimensional personal value, so the value of each life can be represented by a two-dimensional vector (the two dimensions being goodness and undistinguishedness). We add up these vectors of personal value by vector summation – that is, forming a total vector by lining up the personal vectors one after another so that the first vector points to the tail of the next vector and so on; the total vector points to the end of this combined vector. Since the vectors for the good lives in A point mostly upwards and the vectors for the barely not bad lives in Barely Not Bad Z point mostly to the side, no vector sum of the latter could end up pointing to a point that’s above a vector sum of the former.

A nice feature of the vector-based approach is that it shows how the theory could be extended to cover risky prospects. Normal expected-utility theory rules out incomparability. But, given that the value of each population is represented by a vector, we can multiply the vector for the population in each possible outcome in a prospect with its probability and then add up these products with vector summation. The resulting vector is the expected value of the prospect. The product of vector and a probability is a vector with the same direction as the original vector but with a length equal to the original length times the probability.

Still, Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism entails the barely-good version of the Repugnant Conclusion. But this is not, I think, repugnant given that the critical range is sufficiently wide and consists of undistinguished well-being levels. Given an undistinguished range of well-being levels, the barely-good version of the Repugnant Conclusion can be illustrated by a comparison between the A population and a variant of the Z population, which we can call Barely Good Z, consisting of lives at a well-being level just marginally higher than some well-being level that isn’t good (Figure 10):

Figure 10.

Even though the lives in Barely Good Z are at a well-being level only marginally higher than a well-being level that isn’t good, they are still at a well-being level much higher than any bad well-being level, which makes the comparison less repugnant.

Another potential source of repugnance is that, even though Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism avoids the barely-not-bad version of the Repugnant Conclusion, it still entails a weakened variant of that version:

The Weak Repugnant Conclusion (barely-not-bad version)

Each population consisting of lives at a very good well-being level is not at least as good as some population consisting of lives at a well-being level that is just marginally higher than some bad well-being level.

To see that Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism entails the barely-not-bad version of the Weak Repugnant Conclusion, compare the A population with a variant of the Z population, which we can call Barely Not Bad Z, consisting of lives at a well-being level just marginally higher than a bad well-being level (Figure 11):

Figure 11.

No matter which well-being level the lives in A are at, we can make Barely Not Bad Z sufficiently large so that, for some level in the critical range, the critical total value relative to that level is greater for Barely Not Bad Z than for A; and then A isn’t at least as good as Barely Not Bad Z. Changing what needs to be changed, we can show by an analogous argument that Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism also entails

The Weak Mirrored Repugnant Conclusion (barely-not-good version)

Each population consisting of lives at a very bad well-being level is not at least as bad as some population consisting of lives at a well-being level that is just marginally lower than some good well-being level.

Regarding these weakened variants of the Repugnant Conclusion, Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism is in the same boat as Standard Critical-Range Utilitarianism. But the barely-not-bad version of the Weak Repugnant Conclusion and the barely-not-good version of its mirrored variant are not, I think, very repugnant given an undistinguished range. To see this, it might help to consider the absolute value of A and Barely Not Bad Z. Since A consists of a large number of lives at a very good well-being level, it should be overall (very) good; likewise, since Barely Not Bad Z consists of a large number of lives at an undistinguished well-being level, it should be overall (very) undistinguished.Footnote 23 (That something is very undistinguished means that its value is a long way from good, bad, and neutral.) It might seem strange that something good isn’t at least good as anything that is undistinguished and hence not good. But consider a neutral thing and an undistinguished thing. These two things must be incomparable. When two things are incomparable rather than equally good, there could be a small improvement to either of them that doesn’t make the improved thing at least as good as the other. So there could be some improvement of the neutral thing that isn’t at least as good as the thing that is undistinguished.Footnote 24 But the improvement of the neutral thing must, by (1), be good. Hence there could be something good that isn’t at least as good as something undistinguished. The idea behind undistinguishedness is that it is greedy in that it swallows a certain amount of goodness or badness, which is why a small improvement to one of two incomparable things need not make it better than the other.Footnote 25 So, if we just have that x is good and y is undistinguished, we cannot infer that x is at least as good as y. It seems that, logically, we can merely conclude that

(5) If x is good and y is undistinguished, then either x is better than y or x is incomparable with y.Footnote 26

Changing what needs to be changed, this argument also applies to the barely-not-good version of the Weak Mirrored Repugnant Conclusion.

4. Are there lives with neutral (or close to neutral) personal value?

So far, I have been assuming full comparability between lives – that is, for any two lives, the well-being level of one of these lives is at least as high as the well-being level of the other. By (1), (2), (3), and full comparability between lives, we have that, if there is a life at a neutral well-being level, then there is no life at an undistinguished well-being level. Moreover, if there are lives with neutral personal value, then there are plausibly minimally improved good lives and minimally worsened bad lives. And, if so, there are good lives that are only barely better than some bad lives, which would block the way Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism avoids the Repugnant Conclusion. Let us therefore examine the plausibility of there being lives with neutral personal value based on various accounts of neutral well-being. I shall argue that lives with neutral personal value are implausible on all of these accounts.

A first suggestion, by Broome, is based on temporal well-being, that is, how well off a person is at a time. Consider the following account of neutrality (goodness, and badness) for levels of temporal well-being, which we shall adopt:

A person p who is alive at time t is living at a neutral (good, bad) level of temporal well-being at t if and only if either

a life just like p’s life except that it ends just before t would have been equally good (better, worse) for p as (than) a life just like p ’s life except that it ends just after t or

a life just like p ’s life except that it started just before t would have been equally good (better, worse) for p as (than) a life just like p ’s life except that it started just after t.Footnote 27

Broome’s suggestion is then that

(6) A life is at a neutral well-being level if and only if it is at the same well-being level as a life which is at each time at a neutral level of temporal well-being.Footnote 28

One might wonder how a life could fail to be neutral if it’s always at a neutral level of temporal well-being. It seems that a life cannot be good or bad for the person living unless it is at some time at a good or bad level of temporal well-being. And one might wonder how a life could be undistinguished for the person living it if it is at all times at a neutral level of temporal well-being. Where would the undistinguishedness come from? The most plausible answer is, I think, that an atemporal component of any life is to be alive at least some point in time and that component is undistinguished for the person.Footnote 29 And, since being alive at least at some point in time is a component of any possible life, it has no effect on the comparative evaluations of lives. Hence it doesn’t conflict with the full comparability between lives. It can, however, have an effect on the absolute personal value of a life. It can outweigh certain amounts of personal goodness from moments at good levels of temporal well-being and against certain amounts of personal badness from moments at bad level of temporal well-being. And it makes a life that is always at a neutral level of temporal well-being overall undistinguished for the person living it. The contribution of the neutral temporal well-being in the life will be overall neutral. But, in combination with the undistinguished atemporal component, the life will be overall undistinguished.

Another natural suggestion is that

(7) A life is at a neutral well-being level if and only if it is at the same well-being level as a life without any good or bad well-being components.Footnote 30

Since it’s plausible that there could be lives without any good or bad things, there should be a neutral well-being level if (7) holds. Gustaf Arrhenius provides the following argument for (7):

This definition expresses, I think, the kind of conceptual connection we are looking for. Could one claim, for instance, that a life has negative welfare if it doesn’t involve any bad things at all? Could a life without any good things be good for the person living it? That seems implausible.Footnote 31

Given the Absolute Trichotomy Thesis, this argument is cogent. It seems that a life without good or bad things cannot be at a good or bad well-being level. And, given the standard trichotomy, the only remaining possibility is that it is at a neutral well-being level. But, without the standard trichotomy, there’s a further possibility, namely, that the life is at an undistinguished well-being level. It seems that a life without good or bad things may very well be at an undistinguished well-being level, especially if it includes things that are undistinguished. Hence the argument for (7) isn’t cogent unless we assume the Absolute Trichotomy Thesis, which would be to assume the point at issue. One might try to amend (7) by taking the neutral standard to be a life without any good, bad, or undistinguished well-being components. But, as mentioned in the discussion of (6), there is perhaps no possible life without any undistinguished well-being components.

A common proposal is that

(8) A life is at a neutral well-being level if and only if it is equally good for the person whose life it would have been as never having lived at all.Footnote 32

The standard objection to (8) is that, in order for two states to be equally good for some person, that person has to exist in both states and a person doesn’t exist in a state where they never have a life. Still, I would like to stress another problem. Even if it were possible to compare the personal value between one’s life and never having a life, it might still be that no life would be equally good for the person living it as never having lived at all. Perhaps each life is better, worse, or incomparable for the person living it than never having a life. And then, given (8), no life would be at a neutral well-being level.

We might instead try comparing lives with an arbitrarily short life:

(9) A life is at a neutral well-being level if and only if it is at the limit well-being level of a life l as the duration of l approaches zero.Footnote 33

The underlying assumption of (9) is that a life arbitrarily close to having no duration should be neutral for the person living it. This assumption can, I think, plausibly be rejected. Perhaps such lives are at an undistinguished well-being level or even at a bad well-being level because they are too short. As I suggested in the discussion of (6), there could be an atemporal component of any life that is undistinguished. So, even if the total temporal well-being would approach zero, the overall personal value of a minimally short life could still be undistinguished.

Another proposal is that

(10) A life is at a neutral well-being level if and only if it is at the same well-being level as a life of constant unconsciousness.Footnote 34

A first potential problem is that one might think that a life of unconsciousness would be bad. One might, analogously, prefer a quick death to being in a vegetative state for the rest of one’s life.

Another problem is that (10) conflicts with the sentience criterion of moral status, that is, the criterion that only sentient beings have morally relevant personal value. Even though, for example, a human animal might have a life during which it is always unconscious, that animal life wouldn’t be the life of a sentient being with moral status. Hence that animal life doesn’t have personal value for anyone or anything.

It may be objected that it is not clear why actual consciousness rather than the capacity for consciousness should matter. Don’t we matter ethically during unconscious sleep? Strictly, I think, we don’t. While we sleep, we only matter derivatively, because we will matter when or if we wake up. Having merely the capacity for consciousness only gives you the capacity for mattering; it does not by itself make you matter.

One might try to get around this problem by relying on degrees of consciousness:

(11) A life is at a neutral well-being level if and only if it is at the limit well-being level of a life l as the degree of consciousness of l approaches zero.

This proposal faces much the same problems as (9). Even if the total value of the conscious experiences in minimally conscious lives approach zero, there could still be an undistinguished component that is an essential to all lives, which would make the life overall undistinguished. (One additional worry is that continuous degrees of consciousness down to nothing would suggest that whether something is a life comes in degrees, which would challenge a central assumption of population ethics. I will not discuss this challenge in this paper, however. My approach requires that any positive degree of consciousness is sufficient for the life to have the undistinguished component.)

A further proposal is that

(12) A life is at a neutral well-being level if and only if it is at the same well-being level as a life such that, if that life were added to any population, the value of the new population would be the same, other things being equal.Footnote 35

It’s not clear, however, that there would be a neutral well-being level even given (12). On, for example, Critical-Range Utilitarianism, there’s no life such that its addition to a population wouldn’t affect the value of that population, other things being equal.

5. Dual Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism

So far, we have assumed full comparability between lives. This assumption, however, rules out that there’s a range of undistinguished temporal well-being, given (as seems plausible) that extending a life with a period of undistinguished temporal well-being would make the extended and the unextended lives incomparable. Many of the problems with the interpersonal aggregation of well-being of lives in a population also show up in the intrapersonal aggregation of temporal well-being. For example, if we – in a manner analogous to Total Utilitarianism – aggregate the temporal well-being of the moments in a life by their sum total, we get a personal counterpart to the Repugnant Conclusion:Footnote 36

The Personal Repugnant Conclusion (barely-not-bad version)

Each life at a very good well-being level would be at a lower well-being level than some life in which each moment is at a level of temporal well-being which is barely not bad.Footnote 37

Just like the standard Repugnant Conclusion, this personal counterpart is repugnant. And the other conclusions we found repugnant in our discussion of interpersonal aggregation have similarly repugnant personal counterparts. Since the problem with repugnance in intrapersonal aggregation seems analogous to that in interpersonal aggregation, it’s tempting to deal with these repugnant personal conclusions in the same way as their interpersonal counterparts. Yet the critical-range approach we used for interpersonal aggregation is blocked in the intrapersonal case by the assumption of full comparability between lives.

To resolve this problem, I propose that we give up the full comparability between lives and allow undistinguished levels of temporal well-being by summing not the well-being of lives but instead the well-being of moments in lives. We also give up that all good lives are better, and all bad lives worse, than all undistinguished lives; in accordance with (5), some good and some bad lives are incomparable with some undistinguished lives. We adopt Broome’s definitions for good, bad, and neutral temporal well-being, adding the following definition of undistinguished temporal well-being:

A person p who is alive at time t is living at an undistinguished level of temporal well-being at t if and only if either

a life just like p’s life except that it ends just before t would have been incomparable for p with a life just like p’s life except that it ends just after t or

a life just like p’s life except that it started just before t would have been incomparable for p with a life just like p’s life except that it started just after t.

We can understand levels of temporal well-being of a moment in terms of how things are for the individual at the time.Footnote 38 On a hedonistic account, levels of temporal well-being correspond to the hedonistic tone of the individual’s experiences at the time. It might be that, in between the pleasurable and the painful ranges of the hedonistic spectrum, there isn’t just a single point but a range. Sometimes, it seems to me, I’m in a state which is neither pleasurable nor painful, and then my hedonistic state improves or worsens slightly; yet my state is still neither pleasurable nor painful. This range of the hedonistic spectrum which is neither pleasurable nor painful could correspond to an undistinguished range of temporal well-being.

For a first tentative revision, we define a temporal critical personal value. One calculates the temporal critical personal value of a life relative to a certain critical level by first subtracting the critical level from the level of temporal well-being level for each moment in the life. Hence, in mathematical notation, we let the temporal critical personal value of a life l relative to a certain critical level of temporal well-being w be

Here, P(l) is the set of maximal periods of constant temporal well-being in life l, that is, the set of continuous and maximally extended periods of time such that the moments in l during the period are at same level of temporal well-being throughout; d(p) is the duration of period p; and w(p, l) is the level of temporal well-being of the moments during period p of constant temporal well-being in life l. One calculates the temporal critical total value of a population relative to a certain critical level by adding up the temporal critical personal value for each life in the population. In mathematical notation, we let the temporal critical total value of a population X relative to a certain critical level of temporal well-being w be

where again P(l) is the set of maximal periods of constant temporal well-being in life l, d(p) is the duration of period p, and w(p, l) is the level of temporal well-being of the moments during period p of constant temporal well-being in life l. Unlike the formula for critical total value, the formula for temporal critical total value doesn’t require full comparability between lives; it merely requires full comparability between moments – that is, for any two moments in any two lives, the level of temporal well-being of one of these moments is at least as high as the level of temporal well-being of the other.

Consider

Temporal Critical-Range Utilitarianism

A population X is better than (equally good as) a population Y if and only if, for all levels of temporal well-being w in the critical range, the temporal critical total value of X relative to w is greater than (equal to) the temporal critical total value of Y relative to w.

And consider, more specifically,

Temporal Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism

A version of Temporal Critical-Range Utilitarianism where the levels of temporal well-being in the critical range are undistinguished, the levels above the range are good, and the levels below the range are bad.

Yet this revision is still unsatisfactory. Temporal Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism entails another repugnant variant of the Repugnant Conclusion:

The Temporal Repugnant Conclusion

For any population, there is a better population consisting of lives that only last a few seconds and are at any time during those seconds at a level of temporal well-being which is barely good.Footnote 39

In terms of a two-dimensional vector diagram, the undistinguishedness in lives on Temporal Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism can be thought of as a vector that is proportional to the length of the life to which we add the balance of good and bad in the life to get the overall personal value of the life (Figure 12):

Figure 12.

As long as each moment in the life is at a good level of temporal well-being, the balance of good and bad will outweigh the undistinguishedness to make the life good overall. So a population consisting of very short lives constantly at a barely good level of temporal well-being can be arbitrarily good.

One might be tempted to dampen the repugnance of the Temporal Repugnant Conclusion by having a wide critical range for temporal well-being so that a barely good moment in a life is still much better than any bad moment. The trouble with this move is that there are short periods of my life that I think clearly made my life better, yet it is implausible that, for any population, there would be a better population consisting of lives with the same short duration and the same temporal well-being as one of these periods in my life.

The way to avoid the Temporal Repugnant Conclusion and repugnance in general is, I propose, to have two critical ranges – one for lives and one for moments in lives. We define a personal dual critical total value, for lives, and a dual critical total value, for moments in lives. One calculates the personal dual critical total value of a life relative to a certain critical level of temporal well-being and a certain critical level of well-being for lives by, first, subtracting the critical level of temporal well-being from the level of temporal well-being level for each moment in the life and, second, taking the sum total of these differences and subtracting the critical level of well-being for lives, and then the result is the personal dual critical total value.

The dual critical total value of a population relative to a certain critical level of temporal well-being and a certain critical level of well-being for lives is the sum total of personal dual critical total value of each life in the population relative to these critical levels. Equivalently, in mathematical notation, we let the personal dual critical total value of a life l relative to a certain critical level of temporal well-being wT and a certain critical level of well-being for lives wL be

where again P(l) is the set of maximal periods of constant temporal well-being in life l, d(p) is the duration of period p, and w(p, l) is the level of temporal well-being of the moments during period p of constant temporal well-being in life l.

We let the dual critical total value of a population X relative to a certain critical level of temporal well-being wT and a critical level of well-being for lives wL be the sum total of the personal dual critical total value of the lives in the population, that is,

$$\sum\limits_{l \in X} \Bigg(\sum\limits_{p \in P(l)} (w(p,l) - {w_T})d(p) - {w_L}\Bigg)$$

$$\sum\limits_{l \in X} \Bigg(\sum\limits_{p \in P(l)} (w(p,l) - {w_T})d(p) - {w_L}\Bigg)$$

Here, the inner summation aggregates the well-being of the moments in a single life, and the outer summation aggregates in turn the aggregated temporal well-being from each life in the population. Given that we have two critical levels – one for extensions of lives and one for additions of lives – we can vary both of these independently in two separate critical ranges and thus adopt the critical-range approach simultaneously for both intrapersonal and interpersonal aggregation as follows:

Dual Critical-Range Utilitarianism

A population X is better than (equally good as) a population Y if and only if, for all levels of temporal well-being wT in the critical range for moments and well-being levels for lives wL in the critical range for lives, the dual critical total value of X relative to wT and wL is greater than (equal to) the dual critical total value of Y relative to wT and wL .

We combine this view with a corresponding account of comparative and absolute personal value:Footnote 40

The Dual Critical-Range Account of Personal Value

A life x would be better (equally good) for the person living than a life y if and only if, for all levels of temporal well-being wT in the critical range for moments in lives and well-being levels for lives wL in the critical range for lives, the personal dual critical total value of x relative to wT and wL is greater than (equal to) the personal dual critical total value of y relative to wT and wL .

A life is good (bad, neutral) for the person living it if and only if, for all levels of temporal well-being wT in the critical range for moments and well-being levels for lives wL in the critical range for lives, the personal dual critical total value of that life is positive (negative, zero) relative to wT and wL .

A life is undistinguished for the person living it if and only if it is not good, not bad, and not neutral for the person living it.

Note that there can’t be a life that’s neutral for the person living it if there’s more than one level in the critical range for moments or the one for lives. The combination of Dual Critical-Range Utilitarianism and the dual critical-range account of personal value entails

Dual Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism

A version of Dual Critical-Range Utilitarianism where the levels in the critical ranges for lives and moments are undistinguished, the levels above the ranges are good, and the levels below the ranges are bad.

Translated to a two-dimensional vector diagram, these two critical ranges can be understood as a base amount of undistinguishedness that is added to the value of each life (corresponding to the range for lives) and an amount of further undistinguishedness proportional to the length of the life (corresponding to the range for moments in lives). In addition to these two undistinguished components, we then add the balance of good and bad to get the personal value of the life. To see how this blocks the Temporal Repugnant Conclusion, consider again the short life which at each moment is barely good (Figure 13):

Figure 13.

This life is no longer good overall even though each moment in the life is at a good level of temporal well-being. The added base component of undistinguishedness pushes the overall value further into the zone of undistinguishedness which swallows the slight surplus goodness and makes the life undistinguished overall.Footnote 41

These vectors of personal value of lives are then added up, like before, with vector summation to get the overall value of a population. In this manner, we still retain the Equivalence of Personal and Contributive Value. Hence Dual Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism avoids the standard and the weakened Sadistic Conclusion and their mirrored variants. Moreover, this approach does just as well as Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism in avoiding the repugnance in the aggregation of lives. Given that the critical range for lives is sufficiently wide, Dual Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism avoids the barely-not-bad version of the Repugnant Conclusion and the barely-not-good version of its mirrored variant. And we can give the same defence we gave for Dual Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism in Section 3 for why it isn’t repugnant that Dual Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism entails the barely-not-bad version of the Weak Repugnant Conclusion and the barely-not-good version of the Mirrored Weak Repugnant Conclusion. And the dual critical-range approach avoids the Temporal Repugnant Conclusion if the critical range for lives is sufficiently wide, because lives that only last a few seconds and are at each time during those seconds at a level of temporal well-being which is barely good then have an undistinguished personal and contributive value. Given that the critical range for moments is also sufficiently wide, we can by an analogous line of argument – changing what needs to be changed – show that the Dual Undistinguished Critical-Range Account of Personal Value avoids the personal counterparts to these problematic conclusions. Thus, in conclusion, the dual undistinguished critical-range approach can avoid repugnance in both interpersonal and intrapersonal aggregation. Hence we have a population axiology without repugnance.

It may be objected that Dual Undistinguished Critical-Range Utilitarianism still entails that any population of bad lives is incomparable with some population consisting of lives that are, at all times, at a good level of temporal well-being. Isn’t this repugnant? But note that this will only happen in cases when the population of lives with good well-being contains mostly very short lives. These lives also contain an atemporal component, which is undistinguished for the person whose life it is. This undistinguished component outweighs the small amount of goodness in these lives. Intuitively, it seems that lives that are very short with only a moderate amount of goodness in them are not good. Even though there is nothing bad about them, they are too short to be overall good. Yet existence of these lives does not seem morally indifferent, so they do not seem neutral. Given that we accept that these short lives are undistinguished, it should seem strange or repugnant that enough of them will result in a population that is so undistinguished that it is incomparable with a population consisting of many very bad lives. This is how undistinguishedness and incomparability intuitively works: They greedily swallow goodness and badness.

Author ORCID

Johan E. Gustafsson 0000-0002-9618-577X

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Per Algander, Gustaf Arrhenius, Ralf M. Bader, Richard Yetter Chappell, Tomi Francis, Mats Ingelström, Christopher Jay, Kacper Kowalczyk, Barry Lee, Derek Parfit, Mozaffar Qizilbash, Wlodek Rabinowicz, Korbinian Rueger, Marcel van Ackeren, and Tatjana Višak for valuable comments.

Financial support

Financial support from the Swedish foundation for humanities and social sciences is gratefully acknowledged.

Appendix: The Intuition of Neutrality

There is another puzzle in population ethics which concerns the so called ‘Intuition of Neutrality’. This is another area where the possibility of undistinguishedness may shed some light. Broome presents the intuition as follows:

Interpreted axiologically, in terms of goodness, the intuition is that, if a person is added to the population of the world, her addition has no positive or negative value in itself.Footnote 42

He continues

The only value it can have is the good or bad it brings to other people besides the person who is added. So if it brings neither good nor bad to those people, it is neutral.Footnote 43

Yet this last inference assumes the Absolute Trichotomy Thesis. Even if a life is intrinsically (instrumentally) neither good nor bad, it need not be intrinsically (instrumentally) neutral. Without the Absolute Trichotomy Thesis, we have the further possibility that the life is intrinsically undistinguished and hence that the life has an undistinguished contributory value. Additions to a population can bring not only goodness and badness but also undistinguishedness to the overall value of the population. This overlooked possibility can, I think, solve a puzzle Broome has raised for the interpretation of the Intuition of Neutrality.

But, before we move on to this puzzle, it seems that, for the intuition to be plausible, its scope needs be narrowed somewhat, because the addition of lives at very bad well-being levels seems clearly bad and (perhaps slightly less clearly) the addition of lives at very good well-being levels seems good. We shall therefore interpret the intuition as restricted to additions of lives at well-being levels in a certain range, which we shall call the neutrality range.Footnote 44

A first interpretation of the intuition is that the addition of a life at a well-being level in the neutrality range does not change the value of the population. This interpretation conflicts, however, with the principle of personal good and the transitivity of at least as good as. According to

The Principle of Personal Good

If exactly the same people have a life in population X as in population Y, then,

if X is equally good as Y for each person who has a life in X, then X is equally good as Y and,

if X is at least as good as Y for each person who has a life in X and X is better for some of these people, then X is better than Y.Footnote 45

To see the problem, compare the following populations, where every life is at a well-being level in the neutrality range (Figure A1):

Figure A1.

The letters inside the boxes represent the identity of the people in that population or sub-population. According to the equal-goodness interpretation of the Intuition of Neutrality, A is equally good as B, because the only difference between A and B is that the y people have been added to B at a well-being level in the neutrality range. According to the principle of personal good, C is better than B. Then, by the transitivity of at least as good as, C is better than A. But, according to the Intuition of Neutrality, C is better than A, because the only difference between A and C is that the y people have been added in C at a well-being level in the neutrality range. And we can run an analogous argument against A being equally good as C, changing what needs to be changed. So, if there are two or more well-being levels in the neutrality range, the Intuition of Neutrality is false on the equal-goodness interpretation.

A second interpretation of the intuition is that the addition of a life at a well-being level in the neutrality range makes the population incomparable in value to the original population before the addition. This interpretation avoids the last problem but faces another; compare the following populations, where again each life is at a well-being level in the neutrality range (Figure A2):Footnote 46

Figure A2.

We should grant that C is better than B, since C is both more equal and has a greater sum total of well-being than B. According to the incomparability interpretation of the Intuition of Neutrality, A is incomparable in value with B. Then, by the transitivity of better than, we have that A is not better than C. According to the principle of personal good, A is better than D. According to the incomparability interpretation of the Intuition of Neutrality, C is incomparable in value with D. Hence a move from A to D is bad. And a move from D to C is neutral, according to the Intuition of Neutrality. But a direct move from A to C is not bad. Broome finds this implausible. He argues

The net effect of one bad thing and one neutral thing should be bad. But according to our theory, it is not bad; it is neutral.Footnote 47

Hence

Incommensurateness is not neutrality as it intuitively should be. It is a sort of greedy neutrality, which is capable of swallowing up badness or goodness and neutralizing it.Footnote 48

Neutral changes are intuitively those that – barring any holistic effects due to organic unities – make no change to the value of the world. Assuming a weak form of separability between lives, we can rule out that A’s not being better than C is due to some holistic effect between the x lives and the y lives. Let a neutrality-range addition be an addition of a life at a well-being level in the neutrality range. Broome’s puzzle is that the following four claims cannot all be true:

(13) There is a neutrality range of at least two well-being levels, and neutrality-range additions make a population neither better nor worse.

[From the Intuition of Neutrality]

(14) If neutrality-range additions make a population neither better nor worse, then they are neutral.

(15) If (13), then it is not the case that some neutrality-range addition makes no change to the value of a population.

[The upshot of the objection from transitivity and the Principle of Personal Good]

(16) If neutrality-range additions are neutral, then it is not the case that neutrality-range additions make a population incomparable in value to the population without the addition.

[The upshot of the objection from greediness]

Broome’s preferred way out of the puzzle is to give up the Intuition of Neutrality – that is, (13) – even though he admits that he finds it compelling.Footnote 49

There is, however, another solution, namely, to give up (14). As we noted earlier, the Intuition of Neutrality is that neutrality-range additions are in themselves neither good nor bad. Broome’s assumption of (14) overlooks the possibility that these additions, even though they are neither good nor bad, are still not neutral. Without the assumption of the Absolute Trichotomy Thesis, there is a fourth possibility, namely, that neutrality-range additions are undistinguished. This fourth possibility is compatible with the Intuition of Neutrality, and it solves Broome’s puzzle. Since undistinguishedness is the monadic counterpart of value incomparability between value bearers, it makes sense that – barring holistic effects due to organic unities – changes that are undistinguished make the world incomparable in value to the world without that change. So, if neutrality-range additions are undistinguished, it is not puzzling that such additions make a population incomparable in value to the population without the addition. And, since neutrality-range additions that are undistinguished are not neutral, it is not puzzling that such additions can have the greedy effect of counting against goodness and badness.

Another way to reach the same conclusion is to consider the Intuition of Neutrality in combination with the intrinsic value of states of affairs. Suppose that we accept the Intuition of Neutrality and that h and l are well-being levels in the neutrality range, and that h is higher than l. And let Ah be the state of affairs Adam’s having a life at well-being level h, and let Al be the state of affairs Adam’s having a life at well-being level l. Intrinsically good states of affairs are those that, in Roderick M. Chisholm and Ernest Sosa’s phrase, ‘rate the universe a plus’; similarly, intrinsically bad states of affairs are those that ‘rate the universe a minus’.Footnote 50 Since neutrality-range additions in themselves neither make the world better nor worse, it seems that these two states rate the world neither a plus nor a minus. Hence Ah and Al are neither intrinsically good nor intrinsically bad. It seems clear, however, that Ah is intrinsically better than Al . But then, by (1), we have that Al is not intrinsically neutral, since, if Al were intrinsically neutral, anything that is intrinsically better than Al – such as Ah – would be intrinsically good. Hence Al is intrinsically not good, not bad, and not neutral; so it is intrinsically undistinguished. Thus the Intuition of Neutrality requires that some things are undistinguished.Footnote 51

Johan E. Gustafsson is a lecturer at University of Gothenburg, University of York, and Institute for Future Studies. He is currently at work on the book Money-Pump Arguments, which is forthcoming with Cambridge University Press.