We can understand what the feasts of saints (‘natalitia sanctorum’) are from one responsory that is sung on the feast of blessed Stephen. The responsory says, ‘Yesterday the Lord was born on earth, that Stephen might be born in heaven.’ The feasts of saints reveal the births by which they are born into the fellowship of the nine orders of angels and into the fellowship of the holy fathers of the natural law, the law of the letter and the New Testament.

– Amalar, Liber officialis 4.35In his influential treatise on the liturgy, Amalar (†850–2) offered what at first appears to be a routine explanation of the term natalitium (lit. birthday). It denoted the annual commemoration of a saint’s death because it marked his or her birth into eternal life.Footnote 1 No one illustrated this dual meaning better than Stephen, the celebration of whose feast on the day after Jesus’s Nativity reflected his status as the first martyr (or protomartyr) after Christ.Footnote 2 The responsory quoted by Amalar, Hesterna die, strengthens this argument by positing a causal relationship between Jesus’s literal birth and Stephen’s figurative one.Footnote 3 Yet its quotation is significant for another reason. In Amalar’s day, the great majority of plainsong for the Divine Office – antiphons and responsories – set extracts from the Bible, while a sizable minority of them drew from hagiographic texts. The lyrics of Hesterna die, by contrast, derive from a sermon by Augustine (†430).Footnote 4 As was typical of medieval commentators, Amalar quoted liberally from the works of the Church Fathers, and Augustine was one of his preferred authors. For example, the subsequent chapter in the Liber officialis features a lengthy and acknowledged quotation from Augustine’s commentary on the Gospel of John.Footnote 5 Amalar’s discussion of the term natalitia is thus notable not because it enlists the words of a patristic author but because it does so indirectly, through plainchant, rather than by direct reference to the original literary source.Footnote 6

By the ninth century, the writings of the Church Fathers had left an indelible imprint on the Divine Office. In the Latin West, monastic communities had recited patristic sermons and commentaries as lessons at the night office for at least three hundred years. The Rule of St Benedict provides the earliest evidence for this practice with its instructions for the celebration of matins on weekdays: ‘let books of divine authority, both of the Old and of the New Testaments, be read during the vigils, but also expositions of them, which were made by renowned and orthodox catholic fathers.’Footnote 7 The final caveat reflects the intellectual climate of the time, when the works of fourth- and fifth-century authors such as Augustine came to be regarded as canonical and were frequently edited, revised and recycled.Footnote 8 The use of patristic texts at matins was not limited to the lessons, which were recited to simple tones by single readers, or lectors.Footnote 9 On the contrary, it extended to the antiphons and responsories sung to more or less ornate melodies by soloists and the full choir, a fact acknowledged but little studied in modern scholarship.Footnote 10 But that one of these chants, Hesterna die, drew the attention of the preeminent liturgist of the Carolingian period suggests that they merit further scrutiny. How and why did medieval lyricists select and adapt patristic sources for liturgical performance at the night office? What meanings might the resulting antiphons and responsories have conveyed when sung alongside the sermons and commentaries recited as lessons?

Following Amalar’s lead, this article seeks answers to these questions with an examination of matins on Stephen’s feast. The oldest chants proper to that occasion were the antiphons and responsories that had originated in Rome and were transmitted north to Francia in the eighth and early ninth centuries. Six of these chants, including Hesterna die, set extracts from two related sermons, one, as previously noted, by Augustine and the other by Fulgentius of Ruspe (†533) (Table 2 below). The extent of the verbal debts and their theological significance have gone unrecognised until now. The analysis of the Roman plainsong for Stephen presented below is exclusively literary in character in so far as it is concerned with the verbal rather than musical texts of the chants. It builds on a small but significant musicological literature on the verbal adjustments made by Roman lyricists to the biblical extracts that they set to plainsong.Footnote 11 Such modifications, this research demonstrates, typically served to abbreviate the extract, clarify its literal meaning or otherwise adapt it for a melodic setting. By expanding the field of inquiry to chants whose lyrics derive from non-biblical sources, this article shows how verbal adjustments could also advance theological arguments.Footnote 12 And by further illuminating the working methods of Roman lyricists, it presents conclusions relevant to musicologists and liturgical historians alike.

Table 2 Matins and lauds on the feast of St Stephen. Chants derive from V-CVbav San Pietro B79, fols. 31r–33r and lessons from V-CVbav San Pietro C105, fols. 91v–96v. Concordances are from the Tonary of Metz (ed. Lipphardt), F-Pn lat. 17436, fols. 38v–39r and F-AI 44, fol. 66r–v.

To explicate the diverse relationships of plainsong to its patristic sources, we must first account for the lessons at the night office. This article begins by tracing the development of the readings for Stephen from the seventh through the ninth centuries on the basis of service books known as homiliaries. These are multi-author collections of sermons and commentaries recited at the night office and are thus organised according to the liturgical year.Footnote 13 In recent decades, musicologists have explored the role of such texts in the creation of medieval plainsong and have elucidated the exegetical quality of the medieval liturgy itself.Footnote 14 Yet we have largely ignored one of the key ways in which sermons and commentaries of the Church Fathers circulated in the Middle Ages, i.e., by virtue of their inclusion in homiliaries. These books can signal shifting preferences for certain patristic authors and can thus show how the theological understanding of individual feasts changed over time.Footnote 15 As demonstrated below, the older, Roman homiliary presents Augustine as the pre-eminent authority on Stephen, hardly surprising given that he did more than any other author to shape the canonical portrait of that saint in the Latin West. The newer, Carolingian homiliary, by contrast, excluded Augustine in favour of Fulgentius, who thus became the patristic author most identified with Stephen’s feast in the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, Augustinian echoes continued to reverberate in the Roman plainchant sung at the night office on Stephen’s feast.

St Stephen in the Roman Homiliary

The earliest witnesses to the matins lessons recited on Stephen’s feast are four homiliaries from central and northern Italy. Three date from the eighth century, while the fourth, V-CVbav San Pietro C105, was copied for St Peter’s in Rome in the tenth. All four homiliaries are believed to descend independently from a now-lost archetype (henceforth the ‘Roman homiliary’) compiled in the mid-seventh century for the monasteries serving the Vatican Basilica.Footnote 16 One of the first service books of its kind, the Roman homiliary was an anthology of biblical excerpts and patristic sermons from which the monks of St Peter’s could pick and choose. It offered its users wide latitude in another way: it does not divide texts into lessons, leaving the community – most likely its abbot, cantor or librarian – to decide where to end one reading and to begin another.Footnote 17 Unlike two later types of service book, the office lectionary and breviary (on which more below), the homiliary indicates not what the monks of St Peter’s recited at matins on a particular day but rather the range of options available to them.

The most notable aspect of the provisions for Stephen’s feast in the Roman homiliary is the inclusion of scripture (Table 1). True, the Rule of St Benedict prescribed the recitation of both scripture and commentary at the night office, but this directive applied to weekdays, not Sundays or feast days. Of the eleven saints’ feasts represented in the Roman homiliary, the only ones to receive a biblical pericope are those belonging to the Christmas Triduum (i.e., the three days after the Nativity), Stephen, John the Evangelist and Holy Innocents.Footnote 19 This underscored the affinity of each feast with Christmas, to which the Roman homiliary assigned three excerpts from Isaiah that remain the standard in modern editions of the Roman breviary.Footnote 20

Table 1 Provisions for the feast of St Stephen in the Roman and Carolingian Homiliaries.Footnote 18

The pericope assigned to Stephen’s feast, Acts 6:8–8:4 (henceforth the ‘Stephen pericope’), is itself unique for being the only account of Christian martyrdom in the Bible.Footnote 21 Here Luke narrates the key events of the saint’s life and death: his evangelisation and miracle working among the people; his speech before the high court of the Jewish elders, the Sanhedrin, in which he defended himself against charges of blaspheming the Law and the Temple; his stoning by an angry mob of Jews outside Jerusalem; and Saul’s persecution of the Church after his death. Significantly, the pericope excludes Luke’s report of Stephen’s selection as one of the seven deacons (Acts 6:1–7), presumably because his assigned role as table server had nothing to do with his actual one as missionary, thaumaturge and martyr.Footnote 22 The pericope offered an unimpeachable historical record that contrasted with subsequent accounts of Christian martyrdom, which were extra-biblical and thus subject to doubt. As Augustine noted in a sermon preached on Stephen’s feast approximately three hundred years after the writing of Luke’s account:

This is the first special privilege of the first martyr, that has to be drawn to your graces’ attention; while we can scarcely lay hands on the stories of other martyrs, to be able to have them read as we celebrate their feasts, the passion of this one is to be found in a canonical book. The Acts of the Apostles is a book from the canon of scripture.Footnote 23

The very existence of the Stephen pericope was one of many indications of Stephen’s pre-eminence as the first martyr after Christ.

Augustine looms large in the seven sermons assigned to Stephen’s feast in the Roman homiliary. A rubric distinguishes these patristic texts from the preceding pericope: ‘here begin the sermons of the bishop, St Augustine, on the feast of St Stephen the first martyr.’Footnote 24 This too parallels the provisions for Christmas, the first four sermons for which are similarly ascribed to Augustine.Footnote 25 It also contrasts with the two sermons assigned to John the Evangelist and the four to Holy Innocents, which carry no inscription in the Roman homiliary.Footnote 26 Working from other medieval and early modern sources, nineteenth- and twentieth-century editors judged only two of the sermons for Stephen to be authentic works of Augustine (Table 1). An additional two they securely credited to Fulgentius and Caesarius of Arles (†542); the remaining three they viewed as spurious works doubtfully ascribed to Augustine or Maximus of Turin (†408–23 or †465).Footnote 27 As is typical of the Roman homiliary, two of the sermons are composites or patchworks combining longer, authentic texts with shorter, pseudonymous ones. Although the provisions for Stephen in the Roman homiliary are notably heterogenous judging by modern standards of textual criticism, they clearly privilege Augustine. In keeping with the initial rubric, four of the seven sermons were either written by him or were believed to have been so.

The prominence of Augustine’s sermons for Stephen in the Roman homiliary reflects not only the author’s influence on the Latin Middle Ages in general but also his role in shaping subsequent perceptions of this saint in particular. Its scriptural basis notwithstanding, Stephen’s cult was neither widespread nor popular in the Latin West prior to the discovery of his relics in Jerusalem in 415.Footnote 28 Tertullian († after 220), Cyprian of Carthage (†258), Hilary of Poitiers († c. 367) and Ambrose (†397) had mentioned Stephen in their treatises and letters.Footnote 29 So too had Eusebius (†339–40) in his Ecclesiastical History, translated from Greek into Latin by Rufinus of Aquileia in 401.Footnote 30 Nevertheless, Augustine was the first Latin writer known to have dedicated entire sermons to that saint. Long a sceptic of martyr cults and the miracles ascribed to them, he became an enthusiastic proponent of Stephen’s cult owing to the acquisition of the saint’s relics for his bishopric of Hippo Regius around 415.Footnote 31 In the following decade, Augustine delivered at least five sermons on Stephen’s life and death as well as five on the saint’s post-mortem miracles.Footnote 32 While preaching to this flock, he celebrated and encouraged the devotion spurred by the discovery of Stephen’s relics in the Holy Land and their arrival in North Africa. In one of his two authentic sermons in the Roman homiliary, he declared, ‘such a small quantity of dust has assembled such a big congregation here; the ashes cannot be seen; the favours are visibly evident.’Footnote 33 The pride of place occupied by Augustine in the provisions for Stephen in the Roman homiliary befits his role as the first Latin homilist known to have preached on the protomartyr.

Augustine’s sermons on Stephen make a coherent argument for the latter’s sanctity based on his singular relationship with Christ. Illustrative of the author’s Christocentric view of martyrdom in general, this perspective finds expression in an elegant rhetorical conceit with which he begins two sermons not included in the Roman homiliary.Footnote 34 Sermo 314 opens with five paired phrases that aim to capture the attention of his congregation much like the exordium of (or introduction to) a classical oration. Each pair compares Stephen’s feast with Jesus’s nativity, underscoring the likeness of the protomartyr to Christ with antithesis, a rhetorical figure that Augustine frequently employed in his sermons.Footnote 35 The first pair of phrases establishes the parallel structure to which the subsequent ones loosely adhere: ‘yesterday we celebrated the Lord’s birthday; today we are celebrating the birthday of his servant.’ The fourth pair marks the culmination of Augustine’s theological argument: ‘what we celebrated on the Lord’s birthday was his becoming like us; what we are celebrating on his servant’s birthday is his becoming as close as possible to Christ’.Footnote 36 Sermo 319B begins with a similar exordium, which, as noted above, is the literary source of the matins responsory Hesterna die: ‘Yesterday the Lord was born on earth, that Stephen might be born in heaven.’Footnote 37 Once again Augustine describes Stephen as a servant of Jesus – a frequent refrain in his sermons on the protomartyr – but he does not articulate the former’s imitation of the latter explicitly as he does in sermo 314.Footnote 38 Instead, the author makes that point implicitly through his liberal use (once again) of antithesis: even as the paired phrases ostensibly identify the differences between Stephen and Christ, their parallelism in fact emphasises their similarities.

The Roman homiliary demonstrates the appeal that this rhetorical strategy held for subsequent authors and the compilers of the homiliary (Table 1). Its second sermon for Stephen, Fulgentius’s sermo 3, opens with an exordium redolent of Augustine’s sermones 314 and 319B. It is longer than the earlier ones, comprising nine paired phrases. It also sharpens the antithesis with pervasive parallel syntax and imperfect rhymes: the beginning of nearly every phrase alternates between the words ‘hesterna die’ or ‘heri’ (yesterday) and ‘hodie’ (today); or ‘ille’ (that one, i.e., Jesus) and ‘iste’ (this one, i.e., Stephen). As in Augustine’s sermo 314, the first pair establishes the model: ‘Dearest brothers, yesterday we celebrated the birth in time of our king; today we celebrate the triumphal passion of a soldier.’Footnote 39 In its original form, the third sermon in the Roman homiliary, Caesarius’s sermo 219, did not begin with such an exordium; however, here it is supplied with a pseudonymous introduction that does. The latter opens with two paired phrases, the first of which echoes the initial phrases of Augustine’s sermones 314 and 319B as well as Fulgentius’s sermo 3: ‘Yesterday, we had the birthday of our lord saviour; today, we venerate with the greatest devotion the passion of the holy martyr, Stephen.’Footnote 40 By affixing the pseudonymous introduction to Caesarius’s sermo 219, the compilers of the Roman homiliary created a verbal and rhetorical connection with the preceding sermon by Fulgentius. Indeed, thematic resonances between the two strengthen the impression that they were intended to form a pair (on which more below). The exordium of neither sermon explicitly states that Stephen’s sanctity derived from his emulation of Jesus as does Augustine in his sermo 314. But here too the repeated antithesis between December 25 and December 26 – between ‘yesterday’ and ‘today’ – serves as a rhetorical shorthand for precisely that argument.

The provisions for Stephen in the Roman homiliary illustrate another aspect of Augustine’s Christocentric perspective. As portrayed by Luke, the saint is a hard-nosed rhetorician whose speech before the Sanhedrin culminates in a scathing indictment: ‘you stiffnecked and uncircumcised in heart and ears, you always resist the Holy Ghost. As your fathers did, so do you also’ (Acts 7:51). Yet Stephen famously ends his life with forgiveness towards the Jews who stone him: ‘and falling on his knees he cried with a loud voice, saying: “Lord, lay not this sin to their charge”’ (Acts 7:59). This dying prayer accentuates the contrast between Stephen and his persecutors, whom Luke vilifies as a murderous band driven half mad by his denunciation of them.Footnote 41 Eusebius recognised its significance, noting that the prayer made Stephen the perfect martyr, a model of compassion for those who came after him.Footnote 42 But Augustine explores its significance more deeply. In his final authentic sermon in the Roman homiliary, he observes that Stephen’s prayer finds a direct antecedent in Jesus’s plea from the Cross: ‘father, forgive them, for they know not what they do’ (Lk 23:34). Stephen’s final words do not simply reveal his own perfection, as they do for Eusebius, but mark the culmination of a life lived in imitation of Christ. ‘Like a good sheep’, Augustine concludes, ‘he followed in the footsteps of his shepherd.’Footnote 43

Elsewhere in the Roman homiliary Augustine develops even further the theme of imitatio Christi in relation to the dying prayer. Near the beginning of sermo 317, he cites Jesus’s famous admonition for the Sermon on the Mount: ‘Love your enemies: do good to them that hate you: and pray for them that persecute and calumniate you’ (Mt 5:44). If we find this precept too difficult to follow, Augustine notes, we need only look for inspiration to our ‘fellow servant’ (conservus), Stephen, who, with his love for his persecutors, imitated Christ despite having been born into sin.Footnote 44 The imperative to love one’s enemies becomes the central theme of the sermon ascribed to Augustine that begins the provisions for the protomartyr in the Roman homiliary. Sermo 382 construes Stephen’s prayer as a conscious, calculated act of emulation of Mt 5:44. It deftly relates his plea to an ostensibly unrelated aspect of the saint’s biography that was omitted from the Stephen pericope, i.e., his ecclesiastical office: ‘he was a deacon, he read the Gospels, which you read or hear as well. There he found it written, “Love your enemies.” This he learned by reading and perfected by doing.’Footnote 45 In both the authentic and pseudonymous sermons in the Roman homiliary, then, Stephen’s love for his persecutors emerges as the lynchpin in Augustine’s Christocentric portrait of the protomartyr.

Once again, Fulgentius’s and Caesarius’s sermons in the homiliary illustrate the appeal of Augustine’s views to subsequent patristic authors. From the opening, above-quoted sentence of his sermo 3, Fulgentius casts Stephen as a soldier of Christ (miles Christi), a common epithet in liturgical Latin whose significance can easily be overlooked.Footnote 46 With his use of other military terms, the homilist develops the metaphor of the martyr as a soldier who emerges triumphant on the battlefield. Most importantly, Fulgentius asserts that Jesus ‘bestowed a great gift (“magnum donativum”) upon his soldiers, with which He not only copiously enriched them but also invincibly strengthened them for combat.’Footnote 47 ‘Donativum’ lends the passage imperial lustre, denoting a formal gift bestowed by Roman emperors upon each of their soldiers on a special occasion such as a victory in battle.Footnote 48 Fulgentius immediately identifies the gift as caritas (love or charity), a quality not normally associated with battle-hardened soldiers but one that he folds into his military vocabulary by describing it as the weapon with which Stephen defended himself from his persecutors. Fulgentius devotes the remainder of his sermon to the saint’s caritas, repeating the term no fewer than twenty-eight times. He identifies it as the key to Stephen’s sanctity and the quality most worthy of imitation: ‘Charity is therefore the fount and origin of goodness: an extraordinary defence, the way which leads to heaven.’Footnote 49 Caesarius’s sermo 219 develops this theme even further, thus strengthening the impression that the compilers of the Roman homiliary intended it to form a pair with Fulgentius’s sermo 3. Urging his flock to emulate not only ‘the faith of such great a teacher’ but also ‘the charity of such an illustrious martyr’, Caesarius devotes most of his sermon to a discussion of how Christians can practice charity in their daily lives.Footnote 50 Neither sermo 3 nor sermo 219 portray Stephen’s love for his persecutors as an imitation of Christ; however, their overriding emphasis on caritas shows, yet again, how the Roman homiliary was a vehicle for Augustine’s Christological perspective on the protomartyr.

The predominance of Augustine in the Roman homiliary did not guarantee that his depiction of a caring, compassionate Stephen translated into liturgical practice. This book was an anthology, and thus the themes that reverberated at the night office depended on the sermons its users selected for recitation. Were they to choose Pseudo-Maximus’s sermo 29, which portrays the protomartyr as a more assertive, indeed combative figure, a far different portrait of Stephen would emerge in liturgical performance. Yet we know how at least one community used the Roman homiliary. Its tenth-century descendent, V-CVbav San Pietro C105, which was compiled for the Vatican Basilica, features interlinear and marginal notes indicating which sermons were recited and how they were divided into lessons. Judging from the handwriting, these annotations may be nearly as old as the main text. They specify that on Stephen’s feast, the monks of St Peter’s recited the Stephen pericope as the first, second and third lessons and Pseudo-Augustine’s sermo 382 as the fourth, fifth and sixth. On his octave, they recited Fulgentius’s sermo 3 as the first six lessons. On both days, they drew the seventh, eighth and ninth lessons from sermons on the Nativity, as was their custom on saints’ feasts during Christmastide.Footnote 51 This selection of sermons ensured that the Augustinian portrait of Stephen translated into liturgical practice. But it also illuminates the work of Roman lyricists who supplied the proper antiphons and responsories for the night office on the protomartyr’s feast.

The Roman Night Office for St Stephen

The most important witness to the sung portions of the Divine Office at St Peter’s is the twelfth-century antiphoner V-CVbav San Pietro B79. Compiled for the secular canonry that replaced the monasteries serving the Vatican Basilica, it prescribed the celebration of saints’ feasts during Christmastide in the following way.Footnote 52 The chants of lauds, terce and none were proper to the saint, those of prime, sext and vespers to Christmas. The canons similarly divided the night office, with the first and second nocturns given to the saint and the third to the Nativity.Footnote 53 In Stephen’s case, moreover, the antiphons for the second nocturn of matins derived from the Common of Multiple Martyrs.Footnote 54 Finally, as Amalar discovered when he visited the Eternal City in 831, the Romans celebrated matins and lauds without a break, i.e., as a single, continuous office.Footnote 55 Table 2 thus includes the proper chants for both canonical hours. The Vatican antiphoner supplies more chants than necessary with seven (rather than six) responsories for matins and two additional antiphons for the Benedictus at lauds.Footnote 56

The verbal (though not necessarily musical) texts of these chants are far older than V-CVbav San Pietro B79 itself.Footnote 57 In his study of the Mass Proper, Walter Frere established the principle that ‘fixity means antiquity’. Thus, a chant with a stable liturgical assignment can be presumed to be relatively old.Footnote 58 Judged by this standard and as demonstrated below, at least two chronological layers of Roman plainsong can be discerned in the provisions for St Stephen in the Vatican antiphoner. The oldest comprises the responsories, which predated and were part of the initial transmission of the cantus romanus to Francia under Pippin III (r. 751–68). The newest includes the matins antiphons, which originated in the second half of the eighth or early ninth century. These chants were sent north during or shortly after the reign of Charlemagne (r. 768–814).Footnote 59 The dating of the lauds antiphons is less certain, but they were perhaps as old as the responsories.

The liturgical stability of the seven responsories provides strong evidence for their antiquity. Five are transmitted in all twelve sources of René Hesbert’s CAO and a sixth in eleven.Footnote 60 Likewise suggestive are the concordances between V-CVbav San Pietro B79 and the three earliest sources for the chants of the Divine Office. The first is the Tonary of Metz, an inventory of antiphons and responsories arranged according to modal assignment.Footnote 61 The second and third are the oldest extant antiphoners: F-Pn lat. 17436 (northeast Francia, c. 870; the ‘Antiphoner of Compiègne’) and F-AI 44 (Albi, c. 890).Footnote 62 The Metz Tonary lists four responsories proper to Stephen’s feast, two of which, as shown in Table 2, are in the Vatican antiphoner.Footnote 63 The similarities between F-Pn lat. 17436 and V-CVbav San Pietro B79 are closer still. The Compiègne antiphoner transmits all seven responsories in Vatican antiphoner in a nearly identical order. The only major difference involves the fourth responsory, which features a different verse in the two manuscripts.Footnote 64 F-AI 44 exhibits looser affinities with V-CVbav San Pietro B79: it preserves six of the seven responsories in V-CVbav San Pietro B79 but in a different order and, in three instances, with different verses. Taken together, the circulation of the seven responsories in the CAO sources as well as the ninth-century tonary and antiphoners strongly suggests that they belong to the initial Frankish recension of Roman plainsong in the 750s and 60s.

The transmission the antiphons for matins and lauds is more varied. Hesterna die (M-A1), Qui enim corpori (M-A2) and Praesepis angustia (M-A3) form a trio owing to their verbal debts to two related sermons by Augustine and Fulgentius (on which more below). Their literary affinities suggest they were created as a unit, as does their widespread circulation in antiphoners and breviaries of the eleventh through fifteenth centuries, which typically position them as the first, second and third antiphons for matins as in V-CVbav San Pietro B79.Footnote 65 But their near-total absence from the earlier, ninth-century sources suggests these chants may have been relatively recent additions to Stephen’s liturgy. The Tonary of Metz includes M-A3 but not M-A1 or M-A2; neither F-Pn lat. 17436 nor F-AI 44 provide any matins antiphons proper to Stephen’s feast.Footnote 66 The eight antiphons for lauds, by contrast, are better attested: six of them appear in F-Pn lat. 17436, four in F-AI 44 and three in the Tonary of Metz (Table 2).Footnote 67 If fixity indeed means antiquity, they were older than the antiphons for matins and perhaps as ancient as the responsories.

Once again, Amalar proves to be a helpful guide, providing additional evidence for the stratification of this plainsong for St Stephen. In the commentary on a revised, now-lost antiphoner that he compiled in or shortly after 831, he identifies two principal sources for his work.Footnote 68 The first was an antiphoner from Metz, which preserved the cantus romanus as it had been adopted under Bishop Chrodegang (†766) and which Amalar regarded as his native tradition. The second was a Roman antiphoner, at least part of which reflected the state of the Divine Office during the pontificate of Hadrian I (772–95).Footnote 69 Twice he notes that the Roman source contained antiphons and responsories proper to saints’ feasts that were missing from his Messine source. These chants Amalar regarded as unimpeachably Roman in origin and thus worthy of inclusion in his revised antiphoner.Footnote 70 They must have been the work of Roman lyricists active after the initial transmission of Roman plainsong north to Metz in the 750s or 60s.

The creation of new office chants for the Sanctorale provides the context for Amalar’s elliptical description of matins on Stephen’s feast, one that requires a good deal of inference to interpret:

The antiphons that we are accustomed to sing at the night office on the feasts of the saints begin with the antiphon, ‘His will was in the law of the Lord, day and night.’ I believe that these have been excluded by moderns from the multitude of antiphons that I have copied from the Roman antiphoner into ours. If someone wants to read them, they will find them laid out not from the beginning, as they are sung by us.Footnote 71

Amalar starts by identifying a set of antiphons beginning with In lege domini, which, he suggests, were sung on saints’ feasts at Metz according to the older Roman tradition. As preserved in later sources such as V-CVbav San Pietro B79, the lyrics of these chants derive from the psalms with which they are paired. They are not proper to any single feast and thus appear near the end of antiphoners and breviaries as part of the Common of One Martyr.Footnote 72 This is precisely the arrangement Amalar seems to envision. He notes that his contemporaries now eschew In lege domini in favour of the proper antiphons that, as he explained in his prologue, he has adopted from the newer Roman tradition. These newer chants, one might add, surely included the aforementioned trio of matins antiphons: Hesterna die, Qui enim corpori and Praesepis angustia. Having been displaced by these proper chants, In lege domini appears not near the beginning of Amalar’s revised antiphoner, among the provisions for Stephen’s feast, but, by implication, near the end with the Commune Sanctorum.

Having discussed the antiphons for the night office on Stephen’s feast in a relatively oblique manner, Amalar proceeds to address the responsories more directly and succinctly:

I have ordered the responsories according to logic of the story and the order of [Stephen’s] deeds. Where I have changed the words in accordance with the Roman antiphoner, I have placed an R in the margin of the same page.Footnote 73

This passage allows for three conclusions, the first and second of which are corroborated by literary analysis in the subsequent section of this article. First, the responsories draw their lyrics from the account of Stephen’s heroic ‘deeds’, i.e., the Stephen pericope. Second, acting on his own initiative, Amalar arranged the responsories in narrative order, an indication that they had not been so organised in the antiphoner from Rome.Footnote 74 Third, and most important, he notes variant readings in the responsory lyrics in his Roman source, implying that it transmitted the same selection of responsories as the one from Metz. If so, these chants belonged to the old Romano-Messine tradition and thus predated the proper antiphons for Stephen’s feast. In its totality, then, Amalar’s commentary both strengthens and nuances the hypothesis that V-CVbav San Pietro B79 preserves at least two major chronological layers of Roman plainsong for the protomartyr: the matins responsories belonged to the first transmission of the cantus romanus to Francia in the 750s or 60s, while the matins antiphons postdated it. The dating of the antiphons for lauds, which Amalar does not discuss, remains more mysterious, but they may have been as old as the responsories.

Together with the homiliary, V-CVbav San Pietro C105, the Vatican antiphoner thus facilitates the reconstruction of the readings and chants of the night office as celebrated at St Peter’s on the Stephen’s feast in the early Middle Ages. The development of the four monasteries at the Vatican may have shaped the creation of the lessons, antiphons and responsories. Two of these religious communities were dedicated to the protomartyr, the older of which was known as St Stephen Major. First documented during the pontificate of Gregory III (731–41), it was reformed by Pope Hadrian I (772–95) owing to the alleged carelessness with which its members celebrated the liturgy. The newer one, St Stephen Minor, was the final monastery established at St Peter’s. It was founded by Pope Stephen II (752–7), who, much like Hadrian later in the century, sought to revitalise the Divine Office at St Peter’s and throughout Rome.Footnote 75 The presence of first one and later two monasteries dedicated to Stephen gave Roman liturgists and lyricists every incentive to fashion readings and chants for the night office on his feast with particular care. Moreover, the reform of St Stephen Major or the foundation of St Stephen Minor by the protomartyr’s papal namesake may well have prompted the creation of the proper antiphons, which, as noted above, probably date from this same period. But whatever the impetus for these later chants, their chronological distinction from the responsories finds expression in the different ways in which these two genres relate to the biblical and patristic texts recited as lessons on Stephen’s feast.

The Matins Lessons and Responsories

The lessons for St Stephen in the descendant to the seventh-century Roman homiliary, V-CVbav San Pietro C105, illustrate the care one would expect at a church served by two monasteries dedicated to the protomartyr. Religious communities took various approaches to the division of biblical, patristic or hagiographic texts into liturgical readings. One was to parse these texts into lessons of roughly equal length irrespective of their internal organization.Footnote 76 Another was to prioritise the narrative and rhetorical structure of the text, as evidenced in the division of the Stephen pericope and Pseudo-Augustine’s sermo 382 in the Vatican homiliary.Footnote 77 The pericope is parsed into three readings of unequal length: M-Lx1 (c. 190 words) begins with the saint’s evangelizing and miracle working and ends with his appearance before the Sanhedrin; M-Lx2 (c. 900 words) comprises his speech countering accusations of blaspheming the Law and the Temple; and M-Lx3 (c. 170 words) recounts his martyrdom and burial. The division of sermo 382 follows an equally discernible logic. In keeping with the central theme of the sermon – Stephen’s imitation of Christ through his compassion for his persecutors – M-Lx4 and M-Lx5 (c. 240 and 200 words) end with the quotation of Jesus’s admonition ‘Love your enemies’ (Mt 5:44) and his dying prayer (Lk 23:34) respectively. V-CVbav San Pietro C105 does not indicate the conclusion of M-Lx6. Following the logic of the previous two lessons, it may have ended as early as the quotation of Stephen’s dying prayer (Acts 7:59), thereby resulting in a relatively short reading of c. 150 words. At the other extreme, it perhaps extended as far as the conclusion of the sermon, yielding a longer reading of c. 650 words.

As preserved in V-CVbav San Pietro B79, the matins responsories are broadly reminiscent of the provisions for Stephen in the Roman homiliary and, by extension, V-CVbav San Pietro C105. Judging from their stability in liturgical assignment across medieval sources (fixity means antiquity) and from Amalar’s testimony, these are the oldest of the proper chants assigned to the protomartyr’s feast. Having been transmitted north from Rome to Metz in the 750s or 60s, they may have not long post-dated the original homiliary, which dates from the seventh century. The literary source for the majority of responsories is the most obvious connection between the two: six of these seven chants quote or paraphrase the Stephen pericope and two (M-R4 and M-V6) incorporate its incipit, Stephanus autem plenus gratia (Table 2). The lyrics of five of seven responsories derive from Luke’s account of Stephen’s martyrdom (Acts 7:55–9). They thus mirror the sermons in the homiliary, including Pseudo-Augustine’s sermo 382, which likewise focus on Stephen’s death to the near exclusion of the other events narrated in the pericope. Conversely, none of these chants tell of Stephen’s ordination as a deacon (Acts 6:1–7), which accords with the exclusion of this part of Luke’s narrative from the reading. Yet these general affinities do not extend to individual pairs of lessons and responsories. In offices compiled during the central or late Middle Ages, the lyrics of a responsory often echo or comment on the preceding lesson in keeping with the role of the chant as a musical postlude to reading.Footnote 78 This is not the case in these earlier, Roman responsories for Stephen. These chants are not arranged in narrative order, which Amalar considered an oversight to be corrected, and only one (M-R3/V3) derives its verbal text from its lesson.

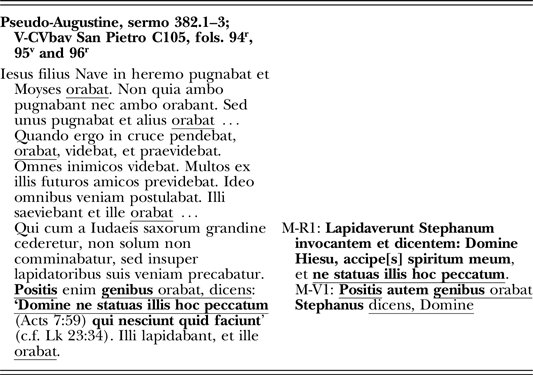

Two responsories echo with particular force patristic sermons associated with Augustine. The first, Lapidaverunt Stephanum (M-R1/V1), draws its text from Acts 7:58–9, thereby signalling the overriding concern of the entire set of responsories with his martyrdom (Table 3):

[M-R1:] They stoned Stephen [while he was] invoking and saying, ‘Lord Jesus, accept my spirit and lay not this sin at their charge.’ [M-V1:] And falling to his knees, Stephen prayed, saying: [M-R1:] ‘Lord [Jesus, receive my spirit and lay not this sin at their charge.]’

Table 3 Pseudo-Augustine, sermo 382.1–3 and Lapidaverunt Stephanum (M-R1/V1). Underlining indicates key words common to the sermon and the chant. Bold text indicates text from the VL or Vulgate. Text in brackets indicate variants in F-Pn lat. 17436.

Following Augustine, the sermons in the Roman homiliary repeatedly cite Stephen’s compassion for his persecutors as the prime expression of his imitation of Christ, more important even than his martyrdom itself. According to Luke, Stephen makes two distinct petitions, one on behalf of himself while standing (‘accept my spirit’) and another for the Jews while kneeling (‘lay not this sin at their charge’). By contrast, M-R1 elides the two pleas into a single utterance. His words obtain additional prominence by virtue of their position in the second half of the respond, or repetendum, which is repeated after the verse. Hence Stephen’s dying prayer is sung twice. Occupying pride of place at the beginning of the series of responsories, M-R1 thus reinforces the Christocentric portrait of Stephen developed by Augustine.

Nevertheless, the lyrics of M-V1 differ from its scriptural source in a way that raises deeper questions. Acts 7:59 describes Stephen’s final plea as a dramatic exclamation – ‘he cried with a loud voice’ (‘clamavit voce magna’) – but the responsory verse employs a more subdued verb of speaking – ‘he prayed’ (‘orabat’). This discrepancy cannot be explained as the type of small lyrical adjustment typical of Roman plainsong, e.g., the deletion of conjunctions such as ‘autem’, which, in this case, is actually preserved (i.e., ‘positis autem genibus’).Footnote 79 Alternatively, the substitution of ‘orabat’ for ‘clamavit magna voce’ might be thought to be the result of the derivation of the responsory text from the Vetus latina (henceforth VL), the Latin translations from the Greek Bible that predated Jerome’s Vulgate. This is common among Roman chants for the Mass and Divine Office and is often taken as a sign of their antiquity.Footnote 80 M-R1 is a case in point: its reading ‘accept my spirit’ (‘accipe’) accords with the VL rather than the Vulgate, which features ‘receive my spirit’ (‘suscipe’).Footnote 81 But the two translations of Acts are unanimous in their use of ‘clamavit’ as the verb of speaking for Stephen’s dying prayer. Whence did ‘orabat’ come and what, if anything, is its significance?

The sermon recited as the fourth, fifth and sixth lessons at matins provides an explanation for this discrepancy between the chant and its scriptural source. The main theme of Pseudo-Augustine’s sermo 382, as noted above, is that the protomartyr’s expression of charity for the Jews was the key element in his imitation of Christ. Alone among the sermons, it cites Moses as a model for Stephen’s compassion, an apt comparison given the considerable attention that Stephen devoted to the Old Testament prophet in his speech before the Sanhedrin (Acts 7:20–44).Footnote 82 As shown above in Table 3, sermo 382 begins with an allusion to Moses’s petition on behalf of the Israelites to God, whom they angered with their false idols (Ex 32:11–14). It contrasts Moses with his military commander, Joshua (Jesus, son of Nave), ending with one of Augustine’s favourite rhetorical figures, anthesis: ‘But one fought, the other prayed (“orabat”).’ The sermon proceeds to the New Testament exemplum, Christ’s dying prayer (Lk 23:34), which marks the conclusion of M-Lx5 in the Vatican homiliary. Once again, Pseudo-Augustine employs ‘orare’ in the imperfect tense, the second time in a pair of antithetical phrases that parallel those quoted just above: ‘Those men raged, this one prayed.’ Finally, sermo 382 arrives at Stephen’s last words, underscoring the central argument by combining his dying prayer with that of Jesus into a single petition: ‘Lord, lay not this sin at the charge of those who know not what they do.’Footnote 83 Moreover, it replaces ‘clamavit voce magna’ with ‘orabat’ as the verb of speaking as likewise occurs in M-V1. This section of the sermon ends with a familiar rhetorical flourish: ‘Those men hurled stones, this one prayed.’ The discrepancy between sermo 382 and scripture – both the VL and Vulgate – was surely an intentional change designed to extend the verbal and rhetorical parallels from Moses and Christ to Stephen. This in turn reinforces the Augustinian portrait of the saint as kind and compassionate, one who not simply cried but prayed on behalf of his persecutors. In all likelihood, the variant, ‘orabat’, in M-V1 thus derives from the sermon. Its inclusion in the initial responsory lends greater weight to the argument developed by pseudo-Augustine regarding Stephen’s sanctity. Furthermore, it provides preliminary evidence for a significant discovery explored more deeply below: Roman lyricists set scripture not only directly but also as it was quoted and modified in patristic texts such as sermo 382.

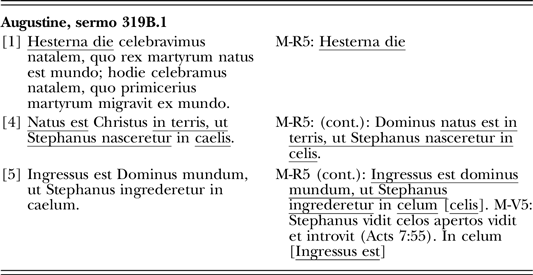

If M-R1 supports the case for Stephen’s sanctity with a key word such as ‘orabat’, another responsory does so with its rhetoric. As noted at the beginning of this article and shown in Table 4, Hesterna die (M-R5) draws much of its text from a sermon not included in the Roman homiliary, namely Augustine’s sermo 319B.Footnote 84 This was one of two sermons in which Augustine develops the rhetorical strategy that undergirds his Christocentric portrait of Stephen. It begins with an exordium comprising eight pairs of parallel phrases that contrast Jesus’s Nativity with the protomartyr’s feast. Augustine’s rhetorical gambit undoubtedly appealed to Roman lyricists because it provided balanced phrases and subphrases suitable for melodic setting as a responsory. The respond combines the first two words of sermo 319B with the fourth and fifth pairs of antithetical phrases:

[M-R5:] Yesterday the Lord was born on earth, that Stephen might be born in heaven. The Lord entered the world, that Stephen might enter into heaven. [M-V5:] Stephen saw the heavens opened; he saw and entered [M-R5:] into heaven.

Table 4 Augustine, sermo 319B.1 and Hesterna die (M-R5/V5). Underlining indicates key words common to the sermon and the chant. Numbers in brackets denote pairs of antithetical phrases. Text in brackets indicate variants in F-Pn lat. 17436.

Two lyrical adjustments accentuate the parallelism of the first phrase with the second and third, once again suggesting a concern with verbal and musical balance: the replacement of ‘Christus’ with ‘Dominus’ and the transposition of word order placing the subjects (the Lord and Stephen) first.Footnote 85

The selection of the fourth and fifth pairs of phrases betrays the lyricists’ theological priorities as well as their musical ones. With their repeated contrast between earth (terrae or mundus) and heaven (caelum), these alone among the eight pairs in the exordium juxtapose this world and the next. The responsory verse suggests that this was indeed key to their appeal. M-V5 refers to the miraculous vision that Stephen experienced before his martyrdom, paraphrasing the saint’s words ‘Behold: I see the heavens (“caelos”) opened’ (Acts 7:55). The structure of Hesterna die highlights the verbal resonance between the quotation from the sermon and the paraphrase of scripture. In V-CVbav San Pietro B79, the repetendum is unusually short, comprising only two words rather than the entire second half of the respond as is the case in F-Pn lat. 17436. The elision of the verse with this repetendum creates a quasi-parallel structure: Stephen saw heaven (‘celos’) and entered it (‘celum’). With its artful manipulation of sermon and scripture, Hesterna die, amplifies the force of Augustine’s rhetoric and, by extension, his portrait of Stephen as the pre-eminent imitator of Christ.

The foregoing analysis of the matins lessons and responsories yield five conclusions about the relationship of the earliest Roman plainsong for Stephen’s night office to the Roman homiliary. First, the texts from the homiliary that the monks of St Peter’s chose to recite on Stephen’s feast – the Stephen pericope and Ps.-Augustine’s sermo 382 – were the literary sources of most of the responsories. Second, the homiliary did not limit the choices of Roman lyricists, who drew on a sermon not included in that anthology, Augustine’s sermo 319B. Third, the responsories exhibit a range of verbal debts and reminiscences, from verbatim quotation of scripture to selective reworking of disparate phrases to the inclusion of single key words. Fourth, plainsong that ostensibly sets scripture may in fact be quoting or paraphrasing a patristic sermon that quotes or paraphrases the Bible. Fifth and finally, the matins responsories reflect and reinforce the Augustinian portrait of Stephen as a compassionate imitator of Christ, a portrait that dominated the Roman homiliary. So too do the matins antiphons, albeit by virtue of their direct dependence on another patristic author represented in the homiliary.

The Matins Antiphons

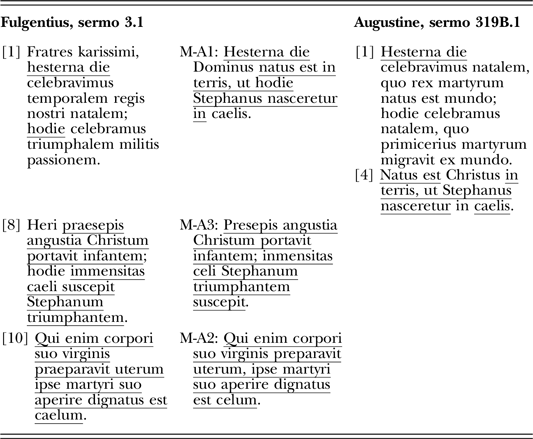

Comprising a newer chronological layer that postdates the mid-eighth century, the trio of antiphons for the night office evinces ties with Fulgentius’s sermo 3, the second sermon for Stephen in the Roman homiliary and one assigned to his octave in V-CVbav San Pietro C105 (Table 5). Hesterna die (M-A1) quotes the fourth pair of phrases from the exordium of Augustine’s sermo 319B and is thus nearly identical to the first half of M-R1. Yet the addition of ‘hodie’ in the verbal text of the antiphon signals a connection with Fulgentius’s sermo 3.1 The text incipit of this sermon, ‘Fratres karissimi, hesterna die celebravimus’, echoes that of Augustine’s sermo 319B. Moreover, it features an exordium reminiscent of Augustine’s sermones 314 and 319B, one whose standardised syntax accentuates the antithesis. In the first pair of phrases, the alternation of ‘hesterna die’ (yesterday) and ‘hodie’ (today) balance the imperfectly rhyming phrases (‘natalem’, ‘passionem’) as they do in the modified version of Augustine’s text in the first antiphon (‘terris’, ‘caelis’).

Table 5 Fulgentius, sermo 3.1, Augustine, sermo 319B.1 and three matins antiphons. Underlining indicates key words common to the sermon(s) and the chant. Numbers in brackets denote pairs of antithetical phrases.

M-A2 and M-A3 strengthen the suspicion that Fulgentius’s sermon inspired the inclusion of ‘hodie’ in M-A1.Footnote 86 These set the tenth and eighth pairs of phrases from its exordium with only one adjustment: the omission of ‘heri’ (yesterday) and ‘hodie’ from the eighth pair. As with the responsory, Hesterna die, these excerpts were likely chosen because they were two of only three pairs from Fulgentius’s exordium to cite the saint’s admission to paradise.Footnote 87 M-A2 proclaims, ‘this one deigned to open heaven (“celum”) for his martyr’ and M-A3 notes, ‘the boundless heaven (“celi”) received Stephen triumphantly.’Footnote 88 The second and third antiphons thus form a trio with the first, which similarly ends, ‘that Stephen might enter into heaven (“caelis”).’ By virtue of their antithetical structure, these three chants adopt Augustine’s rhetorical strategy and make the implicit argument for the protomartyr’s sanctity based on his emulation of Christ. Moreover, the affinities between them suggest that they were composed together – most likely in Rome after the mid-eighth century – and explain why they were transmitted as a unit in later antiphoners such as V-CVbav San Pietro B79.Footnote 89

The Psalm Antiphons for Lauds

The careful planning evident in the three antiphons for matins finds alternative expression in the psalm antiphons assigned to the subsequent hour of lauds in V-CVbav San Pietro B79. To reiterate, the relative stability of their liturgical assignment and their inclusion in ninth-century sources suggests these chants were older than the matins antiphons – they were perhaps as ancient as the responsories. Yet the lauds antiphons employ distinct strategies of literary borrowing, suggesting that they too were composed together as a unit. As summarised in Tables 6 and 7 and demonstrated below, they reveal hitherto unrecognised ties to Augustine’s sermo 319B, the exordium of which was the source for M-A1 and M-R5. Adhesit anima mea (L-A3) and Saule, quid me persequires (L-A5) set excerpts from Ps. 62 and Acts 9 with modifications that reveal their immediate literary source to be the sermon rather than the Bible. Lapidaverunt Stephanum (L-A1) draws its lyrics directly from Acts 7:58–9, while Lapides torrentis (L-2) and Stephanus servus Dei (L-A3) set texts for which no literary source is currently known; however, when sung alongside L-A3 and L-A5, these three chants likewise appear to have been inspired by sermo 319B. But elucidating the relationship of the psalm antiphons for lauds with sermo 319B requires a discussion of the second through fifth sections of the sermon itself.

Table 6 Augustine, sermo 319B.2–3 and four psalm antiphons for lauds. Underlining indicates key words common to the sermon and the chant. Text in brackets indicates variants in F-Pn lat. 17436. Bold indicates text from the VL.Footnote 90

Table 7 Augustine, sermo 319B.4, Ps.-Augustine, sermo 382.4 and a lauds antiphon. Underlining indicates key words common to the sermons and the chant. Text in brackets indicates variants in F-Pn lat. 17436. Bold indicates text from the VL.Footnote 92

In sermo 319B.2–5, Augustine explicates the theological significance of Stephen’s dying prayer by imbedding ‘real’ speech reported in scripture into imaginary dialogues of his own making, a literary technique that he deployed frequently in his sermons.Footnote 93 Near the end of sermo 319B.2, as shown in Table 6, the author quotes Acts 7:58, ‘they stoned Stephen [while he was] invoking and saying’. As expected, the saint makes his plea, ‘Lord Jesus, receive my spirit’, but not before uttering a pastiche of two verses from Ps. 62 with a reference to the instrument of his martyrdom added for good measure: ‘my soul hath stuck close to thee since my flesh is stoned for thee’.Footnote 94 In his commentary on Ps. 62, Augustine reveals why he chose these particular verses. He asks a rhetorical question: what is the glue that binds the soul to God? The answer is love (caritas), the very quality central to Stephen’s imitation of Christ.Footnote 95 In sermo 319B.3, Augustine has Stephen express that same compassion with his dying prayer: ‘Lord, lay not this sin at their charge’ (Acts 7:59). Once again, the author imbeds these words in an invented dialogue, which culminates in a declaration from Stephen illustrating the author’s predilection for calling him a servant of Christ: ‘You are the Lord, I am the servant. You are the Word, I am the disciple of the Word.’

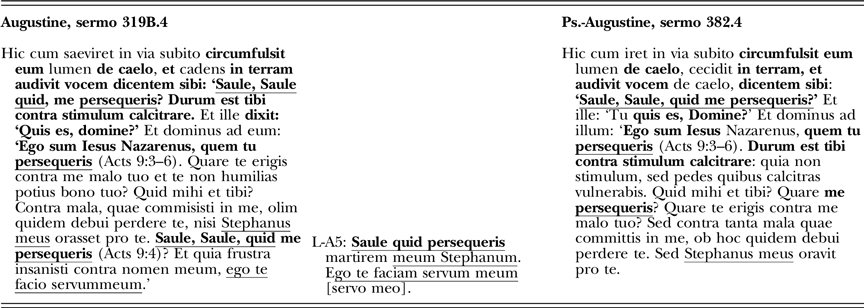

In sermo 319B.4–5, attention shifts to St Paul, who, as the young man named Saul, was a witness to Stephen’s martyrdom (Acts 7:57) (Table 7). The Stephen pericope concludes with Acts 8:1–4, which dovetails the saint’s funeral with Saul’s persecution of the Church. This marks the conclusion of the ‘Jerusalem section’ in Luke’s narrative: henceforth, the Apostles will extend their mission into Judea and Samaria and, with Paul after his conversion, beyond. Stephen in turn emerges as a transitional figure linking Jesus and Paul in a ‘linear chain of success’.Footnote 96 Augustine highlights this lineage in three of his authentic sermons, none of which are anthologised in the Roman homiliary: sermones 316.4–5, 317.6 and 319B.4–5. They employ the same argumentation, rhetoric and imagery, which in turn are adopted wholesale in the pseudonymous sermon recited on Stephen’s feast at St Peter’s: sermo 382.4.Footnote 97 The hitherto unrecognised similarities between sermones 319B.4–5 and 382.4 are particularly close and suggest that the latter was modelled on the former. All four sermons claim that Saul was not merely a witness to but an active participant in the protomartyr’s stoning.Footnote 98 All four attribute Saul’s conversion to the protomartyr’s dying prayer. For instance, sermo 319B.4 begins with an exhortation that sermo 382.4 appropriates almost verbatim: ‘For to learn of your sanctity, how powerful was the prayer of St Stephen, return with us to that young persecutor by the name of Saul.’Footnote 99 The two sermons proceed to dramatize Saul’s encounter with Christ on the road to Damascus with imaginary dialogues that resemble one another. In sermo 319B.4, Jesus asks his famous question, ‘Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me’ (Acts 9:4), not once but twice. He precedes the question by explaining that He would not have saved Saul absent Stephen’s prayer (Table 7). He follows it by echoing Stephen’s declaration of servitude: ‘since you rage in vain against my name, I shall make you my servant.’Footnote 100 With its real and invented dialogues, sermo 319B.2–4 thus provides a dramatic illustration of both the meaning and consequence of Stephen’s love for his persecutors.

Sermo 319B.2–5 was in turn a template for the creation and arrangement of the psalm antiphons for lauds in V-CVbav San Pietro B79. The first four antiphons centre on Stephen’s martyrdom, as does the second and third sections of the sermon (Table 6). Lapidaverunt Stephanum (L-A1) draws its lyrics from Acts 7:58–9 and sets the saint’s dying prayer, mirroring the quotation of those verses by Augustine. It features several adjustments to its scriptural source characteristic of Roman antiphons. The insertion of the demonstrative pronoun, ‘ipse’ (he himself or that one) sharpens the distinction between Stephen and his persecutors: they had stoned him but he called out to God. The insertion of ‘dominus’, once in the accusative and once again in the vocative, clarifies to whom Stephen prayed.Footnote 101 By contrast, Lapides torrentis (L-A2) features what is evidently an original text, which provides a graphic description of the stones cited in the sermon and alludes to Stephen’s emergence as a model of Christian conduct in his own right: ‘The stones of the torrent were sweet to him. All righteous souls follow him.’ Thus far, the resonances between sermo 319B.2–5 and antiphons could easily be dismissed as the result of a common scriptural source, namely Acts 7:56–9. Yet Adhesit anima mea (L-A3) reveals a stronger connection. The lyrics of this antiphon have been mistaken for a conflation of the second and ninth verses of Ps. 62, which is indeed the third psalm of lauds on the feasts of martyrs such as Stephen and with which Adhesit anima mea is paired in the Vatican antiphoner.Footnote 102 As shown in Table 6, L-A3 in fact sets Augustine’s invented dialogue, with ‘caro mea’ and ‘lapidata est’ transposed and the text incipit of the psalm, ‘Deus meus’, added to the end.Footnote 103 Finally, the lyrics of Stephanus servus Dei (L-A4) do not derive from sermo 319B, but their description of Stephen as a ‘servant of God’ nonetheless echoes the saint’s imagined declaration, ‘You are the Lord, I am the servant’ in the sermon.Footnote 104

The relationship of the fifth and final psalm antiphon for lauds to its patristic sources is more complex. Recall that Augustine’s sermo 319B.4–5 is an analysis of the ties that bind Saul to Stephen, one from which Pseudo-Augustine’s sermo 382.4 draws liberally. Table 7 illustrates the verbal debts of the pseudonymous sermon to the authentic one as they pertain to the invented dialogue that Augustine weaves around Saul’s encounter with Jesus on road to Damascus. The lyrics of Saule quid persequeris (L-A5) rework His famous question, ‘Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me’ (Acts 9:4): ‘Saul, why persecutest thou my martyr, Stephen. I shall make you my servant.’ Much like L-A3, this antiphon is easily mistaken for a paraphrase of scripture.Footnote 105 But its final phrase, ‘ego te faciam servum meum’, reveals its direct literary source to be Augustine’s invented dialogue in sermo 319B.4 rather than Luke’s canonical account in Acts 9:4. As a result, L-A5 also echoes sermo 382.4, albeit more faintly, owing to the shared dependence of the chant and sermon on sermo 319B.4. The chant’s resonance with the pseudonymous sermon may have been more perceptible to the monks of St Peter’s chanting lauds on Stephen’s feast. They had just recited at least part of sermo 382 at the second nocturn of matins and may have extended the sixth lesson through its treatment Saul (Table 2).

L-A5 marks the culmination of five psalm antiphons for lauds that articulate key aspects of Augustine’s argument for Stephen’s sanctity. By replacing Jesus with Stephen as the object of Saul’s persecution – ‘Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me’ becomes ‘Saul, why persecutest thou my martyr’ – L-A5 reinforces Augustine’s depiction of Saul as an active participant in Stephen’s murder. As in the sermon so too in the antiphon, Christ’s designation of Saul as ‘servum meum’ echoes Stephen’s role as the original ‘servus Dei’. This verbal reminiscence underscores Saul’s transformation into a virtuous successor to Stephen, one of the righteous souls named in Lapides torrentis (L-A2). Collectively, then, the psalm antiphons for lauds make the same argument as sermo 319B.2–4: the conversion of Saul marked the most dramatic result of Stephen’s love for his persecutors as expressed in his dying prayer.

Of all the plainsong for the combined Roman office of matins and lauds on the feast of St Stephen, the five psalm antiphons for lauds exhibit perhaps the most complex relationship to their biblical and patristic sources. Compare Lapidaverunt Stephanum (M-R1), which belongs to the oldest chronological layer of office chants for the protomartyr. It ostensibly derives its lyrics directly from Acts 7:58–9 in its setting of Stephen’s dying prayer; however, a single word, ‘orabat’, reveals a deeper verbal and theological debt to Pseudo-Augustine’s sermo 382. The psalm antiphons for lauds, which may be as old as the responsories, develop this technique of quoting or paraphrasing scripture not directly but through patristic sermons. With Adhesit anima mea (L-A3) and Saule quid persequeris (L-A5), Roman lyricists reworked Augustine’s imagined dialogues and, in so doing, wove together the words of the Psalmist and Luke with a measure of literary invention worthy of that Church Father. In so doing, they put the finishing touches on the Augustinian portrait of Stephen developed across the entire night office.

The preceding analyses of the lessons, responsories and antiphons in turn raise an additional question: who would have heard and understood such multifarious ties between medieval plainsong and patristic sermons besides the lyricists themselves? The sermons are artefacts of public preaching and thus record the efforts of early bishops such as Augustine, Fulgentius and Caesarius to edify and educate their lay congregants.Footnote 106 These texts repeatedly refer to their original audience, most prominently in their appeals to the homilist’s ‘fratres’, a term that refers to both laymen and women (i.e., brothers and sisters).Footnote 107 Nevertheless, the repurposing of the sermons as matins lessons transported them into a more private, exclusive setting: celebrated in the early hours of the morning before dawn, the night office was largely the purview of the religious communities responsible for the celebration of the liturgy.Footnote 108 Moreover, most of the verbal debts and reminiscences identified above were so subtle that they would have eluded the perception of all but the most erudite of laymen and women. Hence the Augustinian portrait of Stephen that reverberated at matins on the protomartyr’s feast was one directed towards those responsible for celebrating that office, most immediately the monks of St Peter’s. Yet this portrayal would not go unchallenged with the Carolingian revisions to the office liturgy in the late eighth and ninth centuries.

The Carolingian Revisions

The chief vehicle for the Carolingian revisions to the Divine Office writ large was the homiliary compiled by Paul the Deacon at the behest of Charlemagne in the 780s or 90s.Footnote 109 In the prefatory letter known as the Epistola generalis, the Emperor wrote of the efforts of his father, Pippin, to establish the singing of Roman plainsong throughout his realm. To this Charlemagne added his own ambitious project:

Because we found the readings compiled for the night office by the fruitless labour (albeit right intention) of some to be less than suitable – readings that were appointed without including the names of their authors and that were strewn with infinite rounds of textual corruption – we suffered not in our days that dissonant solecisms should resound in the divine readings during the sacred offices, and we bent our mind to reform the course of the same readings into something better. The polishing of that work we enjoined to Paul the Deacon, our dear little client … [who] reading over the tracts and sermons of diverse Catholic Fathers, and selecting what was best, has offered us readings without textual corruptions, bringing them together into two volumes through the circle of the whole year and fit for each distinct feast.Footnote 110

Armed with Charlemagne’s imprimatur, Paul’s homiliary proved to be widely influential, rivalling the Roman homiliary in its popularity: no fewer than fifty-eight complete copies of its winter or summer volumes survive from the ninth and tenth century alone. These books are highly varied in their size, format and contents: religious communities often adapted Paul’s work for their own use by adding, omitting or rearranging material. Nevertheless, these and later witnesses facilitate the reconstruction of his original, which, in its selection of texts and organizational scheme, set the standard for the celebration of the night office for many religious communities.Footnote 111

Paul’s homiliary marked a break with its Roman antecedent in four major respects. In response to his patron’s complaint that earlier homiliaries omitted the names of authors, Paul included attributions for most (though not all) of the sermons and commentaries in his collection. And, following Charlemagne’s charge, he cast a wide net, drawing on authors who had obtained little or no representation in the Roman homiliary. The most notable additions were Gregory the Great (†604) and Bede (†735), whose extracts total eighty-six and greatly outnumber those attributed to Augustine (twenty), Fulgentius (four) and Caesarius (two). Moreover, Paul’s homiliary was not an anthology from which its users were to pick and choose. Instead, it often furnished the precise number of texts to be recited on a given occasion. But Paul’s most significant innovation was his inclusion of a homily or commentary on the Gospel pericope recited at Mass on each Sunday and feast. This brought his homiliary into alignment with the Mass lectionary and thus created a greater degree of consistency across the Mass and Divine Office.Footnote 112

The provisions for Stephen’s feast in the Carolingian homiliary illustrate these four innovations. As shown above in Table 1, this book contains half as many texts as the Roman homiliary, presumably because Paul the Deacon intended all of them to be recited at the night office. He achieved this reduced complement in part by omitting the Stephen pericope, thereby excluding from the night office the account of the protomartyr’s life and death and thus the literary source for the majority of Roman antiphons and responsories. Paul also dispensed with five of the seven sermons from the Roman homiliary, including all the Augustinian and pseudo-Augustinian texts, obscuring the role of Augustine in shaping the received portrait of the protomartyr. In place of the pericope and sermons, Paul added two texts, neither of which have much to do with the specifics of the protomartyr’s biography. The first was two chapters from Augustine’s City of God, which document miracles ascribed to Stephen’s relics in north Africa. The second was Jerome’s commentary on Mt 23:34–9, the Gospel pericope assigned to Stephen’s feast according to Roman tradition.Footnote 113 Here Christ foretold that the scribes and Pharisees would persecute and kill the prophets who would come after Him. Finally, all four texts assigned to Stephen’s feast carry an attribution, although Paul’s crediting of sermo 219 to Maximus rather than Caesarius is now considered spurious.Footnote 114

Yet the Roman elements that Paul the Deacon retained were just as significant as those he replaced. In the Roman homiliary, the sermons of Fulgentius and Caesarius formed a duo: both feature an exordium of paired, antithetical phrases reminiscent of Augustine’s sermones 314 and 319B; both develop the latter author’s portrait of Stephen as exceptionally compassionate. In the Carolingian homiliary they likewise appear consecutively, occupying pride of place at the beginning of the provisions for the saint. Paul nonetheless obscured their relationship with their Augustinian models in two ways. First, Fulgentius’s sermo 3 begins in a different manner – ‘Heri celebravimus’ rather than ‘Fratres karissimi hesterna die celebravimus’ – and thus echoes less clearly the incipits of Augustine’s sermones 314 and 319B: ‘Hesterna die celebravimus’. Second, Caesarius’s sermo 219 appears without its pseudonymous introduction and thus without its exordium evocative of both Augustine’s and Fulgentius’s sermons. The retention of and revisions to the sermons by Fulgentius and Caesarius recall Charlemagne’s charge that Paul cull the best from older models and present them free from errors. Paul may have regarded the Roman incipit of sermo 3 and introduction to sermo 219 as spurious, as do modern editors. Yet whatever his reasons for these modifications, their effect was to further efface the Augustinian tenor of the sermons for Stephen.

Two chants reveal the impact of the Carolingian homiliary on the sung portions of the Divine Office in the late eighth or ninth century. The oldest surviving source for both of them is F-AI 44, the aforementioned antiphoner from Albi of c. 890. The first is Ierusalem, Ierusalem, the last of six possible Gospel antiphons for lauds on Stephen’s feast.Footnote 115 It is exceptional among the office plainchant for the protomartyr by virtue of its lyrics, which do not derive from the Stephen pericope or related sermons. Instead, it sets Jesus’s reproach to the scribes and Pharisees from the Gospel pericope at Mass: ‘O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, thou that killest the prophets and stonest them that are sent unto thee’ (Mt 23:37). This antiphon is preserved in V-CVbav San Pietro B79 (Table 2) but is unlikely to have originated in Rome, where commentaries on the Gospel were not recited at matins. Moreover, the relatively narrow and unstable transmission of Ierusalem, Ierusalem strengthens the suspicion that it was a Frankish addition to Stephen’s liturgy. It survives in only two sources in CAO and an additional eleven in the Cantus Index. These manuscripts transmit its text with at least three distinct melodies categorised variously as Mode 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 or 8.Footnote 116 Guided once again by the principle that fixity means antiquity, Ierusalem, Ierusalem appears to be even newer than the matins antiphons transmitted from Rome to Francia after the mid-eighth century. Conversely, it dates from no later than c. 890 because of its presence in F-AI 44. The literary and manuscript evidence thus supports the following hypothesis: Ierusalem, Ierusalem is the work of a late ninth- or tenth-century Frankish lyricist inspired by the inclusion of commentaries on the Gospel in Paul’s revised homiliary. The chant was later adopted at St Peter’s, as shown by its inclusion the Vatican antiphoner.Footnote 117 The northward pattern of transmission from Rome to Francia typical of plainsong in the eighth and early ninth centuries was evidently reversed through the influence, in this case, of Paul the Deacon.Footnote 118

The second chant to illustrate the effect of the Carolingian homiliary on Stephen’s office liturgy is the matins responsory, Hesterna die. The respond was an unimpeachably Roman plainsong, one quoted by Amalar in his Liber officialis and whose lyrics derived from the exordium of Augustine’s sermo 319B. In the Vatican and Compiègne antiphoners, as shown previously, it is paired with a verse, Stephanus vidit celos, which paraphrases Acts 7:55 and, in so doing, reinforces the rhetoric of text of the respond. In F-AI 44, by contrast, Hesterna die features an alternative verse, Heri enim rex, which sets the first half of the second pair of antithetical phrases from the exordium of Fulgentius’s sermo 3: ‘Yesterday indeed our King, clothed in a robe of flesh, was pleased to visit the earth from the temple of the Virgin’s womb.’Footnote 119 Heri enim rex thus achieves greater uniformity in literary style with the respond, for both showcase antithesis; however, it dispenses with the rhetorical interplay between patristic and biblical text created by the biblical verse Stephanus vidit celos. Both verses circulated widely in the central and late Middle Ages, and thus manuscript transmission does not provide clear evidence for which one came first.Footnote 120 The most plausible scenario is that Stephanus vidit celos is the original Roman verse, which makes intuitive sense given its presence in the Vatican antiphoner. Developing this hypothesis further, Heri enim rex is an alternative verse fashioned by a Frankish lyricist in response to Paul’s retention of Fulgentius’s sermo 3 as only one of two sermons for Stephen.

The Carolingian homiliary would in turn set the standard for the celebration of the night office on Stephen’s feast for religious communities throughout the Middle Ages. From the late tenth century, two new types of service books came to replace homiliaries. The first was the office lectionary, which indicated the precise division of matins lessons by text incipit and explicit; the second was the breviary, which provided the lessons in their entirety alongside the sung items of the Divine Office.Footnote 121 As prescribed in these two types of sources, the selection of biblical and patristic texts for the night office and their division into lessons was highly localised, varying over time and place.Footnote 122 Three cases illustrate the impact of Paul’s revisions. First, the Cluniac lectionary represented a blending of Roman and Carolingian traditions. Judging from copies from the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, the lessons of the first nocturn derived from the Stephen pericope, those of the second from Fulgentius’s sermo 3 and those of the third from Jerome’s commentary on Mt 23:34–9.Footnote 123 Secondly, the Franciscan breviary adhered to the same scheme, while drastically curtailing the biblical pericope by omitting Acts 7:9–8:4.Footnote 124 Thirdly, the Sarum breviary dispensed with the pericope entirely, devoting the first and second nocturns to Fulgentius’s sermon and the final one to a commentary on the Gospel.Footnote 125 The differences between the Cluniac, Franciscan and Sarum books notwithstanding, all three sources show how deeply ingrained Paul’s practice of devoting the third nocturn to a homily or commentary on the Gospel had become.Footnote 126 They also suggest that Paul’s retention of Fulgentius’s sermo 3 made this text widely regarded as an indispensable source for lessons at the night office on Stephen’s feast.

Conclusion

The predominance of Fulgentius’s sermo 3 in later medieval sources for Stephen’s office liturgy obscures an older, more complicated history that has emerged through a study of the seventh-century Roman homiliary and its successors. This anthology offered its users a wealth of patristic sermons from which to choose and the freedom to divide these texts into matins lessons as they liked. Its provisions for Stephen are predominantly Augustinian, not merely because the majority were written by or attributed to Augustine. More significantly, they deploy arguments for the protomartyr’s sanctity first developed by that author, ones based on Stephen’s singular relationship with Christ as cemented in his dying prayer for his persecutors. The eleventh-century descendent of the Roman homiliary, V-CVbav San Pietro C105, shows how this depiction of Stephen as a compassionate, loving saint translated into liturgical practice. The resident canons of St Peter’s in Rome selected the Stephen pericope and a Pseudo-Augustine’s sermo 382, dividing the latter in a way that emphasised Augustine’s Christological portrait. The homiliary of Paul the Deacon in turn obscured that author’s role in shaping medieval perceptions of the protomartyr, giving pride of place instead to Fulgentius and thereby setting the standard for liturgical practice and liturgical commentary thereafter. As the Roman and Carolingian homiliaries show, the selecting and editing of patristic texts for recitation at matins was a creative endeavour that could shape or reshape our understanding of a figure as foundational to Christianity as its first martyr.

Tracing the relationship between patristic sermons and medieval plainsong for the night office on Stephen’s feast in turn takes us into the workshops of Roman and Frankish lyricists. Herein lies the musicological significance of this article. Comprising at least two chronological layers, the Roman responsories and antiphons in V-CVbav San Pietro B79 exhibit a range of connections with biblical and patristic texts, not all of which were recited at matins. These include extended, verbatim quotations as well as isolated key words drawn from Augustine’s and Fulgentius’s sermons. Moreover, several antiphons whose lyrics appear, at first glance, to come directly from scripture are, on closer inspection, paraphrases of Augustine’s invented dialogues, which are themselves based on Luke’s narrative in Acts. In such cases, Roman lyricists were reading the Bible through (not simply alongside) the words of Augustine. The antiphon Ierusalem, Ierusalem and responsory verse Heri enim rex in turn show how Frankish lyricists responded to the shifting priorities in Paul the Deacon’s homiliary. Yet the Roman antiphons and responsories continued to circulate widely through the Middle Ages and beyond, even as the pericope and sermons that inspired them fell out of liturgical use. In all its aforementioned cases of literary borrowing, this Roman plainsong reinforces and develops the Augustinian portrait of the saint articulated in the lessons alongside which the chants were created: Stephen was not simply a fearless martyr but also a compassionate orator who prayed for his persecutors as had Jesus on the Cross.