A borrowed melody in a polyphonic Mass Ordinary setting is fundamental to the identity of that composition. Masses are often labelled in manuscripts and prints by that melody and pre-existing melodies often dictated the liturgical and performance contexts of a given mass. Due to the borrowed melody in Josquin’s Missa Pange lingua, the existing literature on this work associates it with the Catholic liturgical context of that melody: Corpus Christi, Eucharistic votive masses and other forms of devotion to the Blessed Sacrament.Footnote 1 The Pange lingua hymn itself is also intrinsically Catholic: Thomas Aquinas (1225–74) used the incipit and melody of an earlier hymn by Venantius Fortunatus (c. 535–610) to create a Vespers hymn for Corpus Christi.Footnote 2 This feast developed in the midst of a new theological understanding of the Eucharist defined as transubstantiation – a dogma unique to the Catholic Church that uses Aristotelian-based reasoning to explain how the bread and wine change in substance at the moment of consecration to become the body and blood of Christ, but the physical properties or ‘accidents’ remain. Several early sources of the Missa Pange lingua confirm its association with the Eucharist through iconography and the title Missa de venerabili sacramento, but these manuscripts are outnumbered by sources from the mid- to later sixteenth century that come from an institution that was in direct opposition to nearly everything associated with Pange lingua: the Lutheran church.Footnote 3

The intention of this study is not to de-emphasise the connection between the Missa Pange lingua and its borrowed melody or the initial Catholic identity of the mass. Rather, the Lutheran identity of the Missa Pange lingua provides a deeper understanding of how this work was initially received. By tracing the mass through extant sources from its initial circulation among Catholics to a solidified place in the Latin repertory of the Lutheran church, I will argue that this mass, previously confined to its Catholic roots and performance context in musicological studies, should also be considered a Lutheran work. If a mass with such polemical overtones – Luther associated Corpus Christi with hypocrisy and promiscuity – was able to be repurposed by Lutherans, then perhaps other Renaissance compositions should be re-evaluated for potential bi-confessional identities.

The substantial Lutheran engagement with the Missa Pange lingua transcends established facts common to sixteenth-century music narratives: the mass was a technically accessible work composed in the late style of Josquin des Prez, Martin Luther’s favourite composer, who experienced a posthumous ‘Renaissance’ in Germany.Footnote 4 Reformation studies focused on imagery and ritual consistently demonstrate that aesthetics was only one of many factors when reformers decided whether a Catholic object or ritual should be retained or abandoned.Footnote 5 For instance, the teachings of several Protestant leaders on the evils of idolatry resulted in acts of iconoclasm throughout Europe.Footnote 6 This destruction of art works was motivated by theological sentiment rather than aesthetic preferences; Protestants did not break statues because they preferred a different artistic style. Furthermore, a growing body of Reformation scholarship across humanities disciplines demonstrates that confessional boundaries between Catholicism, Lutheranism and Calvinism were less distinct than previously thought.Footnote 7 The ritual and theological contexts of the Missa Pange lingua reveal a blurred but indeed distinct border between the Catholic and Lutheran confessions.

As a polyphonic Latin Mass Ordinary setting, the Missa Pange lingua easily fits into the early Lutheran liturgy. Martin Luther had many criticisms of the Catholic liturgy but found value in the Latin Mass Ordinary texts.Footnote 8 In the preface to the Deutsche Messe, published in 1526 following his Latin Formula missae in 1523, Luther articulated his desire for the vernacular liturgy to exist alongside the Latin rather than replace it.Footnote 9 The Kirchenordnungen (church orders) for newly formed Lutheran communities confirm that Luther’s followers shared this sentiment and prescribed the singing of the Mass Ordinary texts in Latin, German and occasionally both languages in succession.Footnote 10 As a composition associated with Corpus Christi and Eucharistic veneration, the Missa Pange lingua initially appears to have had almost no place in Lutheran devotional life and represents one of the most polemical issues of the Reformation. However, closer examination of Martin Luther’s Eucharistic beliefs reveals a theology much closer to Catholic dogma than those of other Reformers, but not completely in accordance with the Roman Church. Luther believed that Christ was physically – not spiritually – present in the consecrated bread and wine: he often cited the Gospel account of the Last Supper in which Christ says ‘this is my body’ rather than ‘this represents my body’.Footnote 11

In the realm of sixteenth-century source analysis, Lutherans contributed to a unique dissemination pattern surrounding the Missa Pange lingua. While the mass appears in two important prints associated with the German Josquin Renaissance, it is the only Mass Ordinary firmly attributed to Josquin not included in Ottaviano Petrucci’s three volumes of Josquin masses.Footnote 12 In fact, the work is not found in printed form until the Missae tredecim in 1539. Although this print plays a significant role in the German circulation of the Missa Pange lingua, the lack of early printed sources – particularly from Petrucci and Andrea Antico – implies a different circulation pattern from other Josquin masses. Furthermore, the Missa Pange lingua survives in an unusual number of manuscript sources that post-date Missae tredecim, two of which are indicative of an eastern extension of the German Josquin Renaissance in the Czecho-Slovak region.

Finally, a focused study on the two confessional identities of Missa Pange lingua is warranted in the realm of Josquin scholarship. Amidst the watershed of Josquin authenticity studies from the last several decades, the Missa Pange lingua has enjoyed one of the most secure positions in Josquin’s oeuvre.Footnote 13 In a seminal essay on Josquin reception, Jessie Ann Owens offers the following observation:

[T]he patterns of dissemination of [Josquin’s] music and the records of the actual repertories performed in a given time and place reveal that the Josquin we know from the modern edition was not the Josquin experienced in various parts of Europe. . . . [T]o understand his place in history requires replacing the composite picture of modern historiography with a series of images specific to particular times and places.Footnote 14

The German reception history of the Missa Pange lingua provides two contrasting, yet intriguing, ‘images’ of Josquin: the ordained priest who composed a mass for Corpus Christi and Eucharistic votive masses, and Martin Luther’s ‘Noten Meister’, who posthumously supplied music for the faith communities that broke away from the Roman Church that he had served for most of his life.

A CATHOLIC MASS FOR A MEDIEVAL CULT

The Missa Pange lingua is regarded as one of Josquin’s last works due to its omission from Ottaviano Petrucci’s three Josquin mass volumes, particularly the final one published in 1514. While the mass is usually dated sometime after 1514 as a consequence, David Fallows recently suggested a slightly earlier composition date of approximately 1510.Footnote 15 His reasoning is based on seven early Missa Pange lingua sources that date from around 1515 and have secure provenances far from Condé, where Josquin spent the final years of his life (1504–21) and probably composed the Missa Pange lingua (see Table 1).Footnote 16 The Catholic provenances of the complete sources that Fallows identifies, along with additional early sources from the Petrus Alamire workshop at the Habsburg-Burgundian court, confirm the liturgical context given to the mass in most modern scholarship: a setting of the Ordinary text for a Catholic Mass, particularly one for Corpus Christi or some other occasion with a special emphasis on the Eucharist.

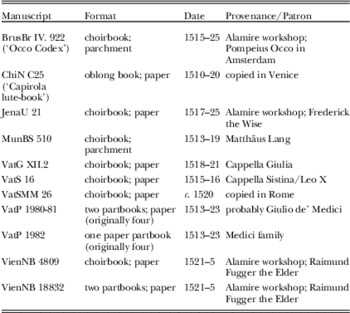

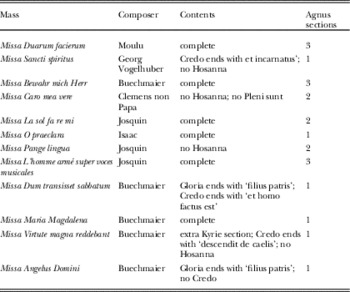

Table 1 Early Missa Pange lingua sources

As Western Christian teaching on the Eucharist became more concrete with the establishment of transubstantiation as doctrine at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, the devout took a greater interest in the sacrament. The Elevation of the Host became the highlight of every Mass, and people began reporting Eucharistic miracles such as bleeding and inexplicably mobile Hosts. Simply gazing at a consecrated Host became immensely popular and resulted in the development of Benediction services, periods of adoration during which a Host was displayed in a monstrance, and outdoor processions with a Host.Footnote 17 Corpus Christi was part of this rapidly growing Eucharistic cult and quickly became a major solemnity. The feast was first celebrated in 1246 in the diocese of Liège after a beguine there named Juliana had a vision consisting of a full moon with a dark blemish; she interpreted the dark blemish as a symbol for a new feast that Christ wanted the Church to celebrate.Footnote 18 The idea of a joyful feast dedicated to the Eucharist, as opposed to the sombre commemoration of the Last Supper on Holy Thursday, spread throughout Europe, and in 1389 Pope Urban VI placed Corpus Christi on the same level as Christmas, Easter, Pentecost and the Assumption by granting indulgences and suspending interdicts on the feast day.Footnote 19

There are three early versions of the Corpus Christi liturgy; Juliana and her confessor wrote the first, and Thomas Aquinas wrote the other two. Pange lingua was a Vespers hymn from the second Aquinas liturgy, which became the official Corpus Christi liturgy for the Roman Church. Aquinas’s Pange lingua quickly acquired other functions beyond Vespers in connection with the emphasis placed on seeing a consecrated Host. Pange lingua and other items from the Corpus Christi liturgy like the sequence Lauda Sion became the music performed during the various processions with the Host and Benediction services.Footnote 20 Eucharistic votive masses also developed out of this effort to extend the moment of Elevation when people could gaze upon the real presence of Christ under the physical form of bread. A unique feature of these votive masses is that a consecrated Host was displayed on an altar throughout the duration of the service. They usually occurred on Thursdays at a side altar and were endowed by the local Corpus Christi fraternity. Although Eucharistic votive masses developed relatively late in the medieval votive mass tradition, they were popular in both the Germanic region and the Low Countries by the turn of the sixteenth century.Footnote 21 Certainly the Missa Pange lingua would have been appropriate for votive masses for the Eucharist along with masses in conjunction with Corpus Christi.

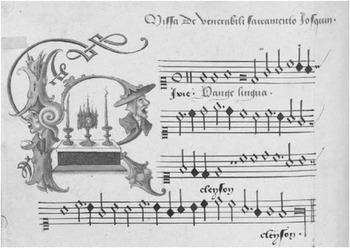

The three Alamire choirbooks with complete versions of the Missa Pange lingua explicitly convey a connection to Eucharistic votive masses.Footnote 22 The mass is labelled ‘Missa de venerabili sacramento’ in JenaU 21 and VienNB 4809, where it was given a prominent position as the opening mass. It is labelled ‘Missa Pange lingua’ in the Occo Codex (BrusBR IV. 922), but that is probably due to the presence of a second ‘mass of the venerable sacrament’, Hotinet Barra’s Missa Ecce panis angelorum, in the manuscript. The Missa Pange lingua is also accompanied by Eucharistic iconography in all three manuscripts: a monstrance and chalice in the Occo Codex, an angel holding a monstrance in JenaU 21 (Figure 1), and a monstrance on an altar in VienNB 4809 (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Jena, Thüringer Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, MS 21, fol. 1v

Figure 2 Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, MS 4809, fol. 1v

While VienNB 4809 was prepared for Raimund Fugger the Elder and probably remained in his private music collection, the other two choirbooks went to patrons who could have facilitated the performance of the Missa Pange lingua in its intended liturgical context. The Occo Codex was commissioned by the Dutch merchant Pompeius Occo (1480–1537) for the Heilige Stede (holy place) chapel in Amsterdam, where Occo served as church warden from 1513 until 1518.Footnote 23 The chapel was built on the site of a Eucharistic miracle that occurred in 1347, in which a Host continuously returned to that location. Occo apparently requested repertory focused on the Eucharist when he commissioned the choirbook, as it contains several settings of texts from the Corpus Christi liturgy such as O salutaris hostia and Tantum ergo, the fifth verse of Pange lingua.

JenaU 21 was used either at the Elector Frederick the Wise’s Castle Church in Wittenberg or by his own court choir, although there are no personal indicators such as a coat of arms closely connecting the manuscript to Frederick himself.Footnote 24 Eucharistic votive masses were celebrated in the Castle Church following Martin Luther’s release of the 95 theses in 1517 and leading up to the years when JenaU 21 was produced. The Verzeichnis aller Chorlichen Ambt in Aller Heyligen Stifftkyrchen zw Wittenberg, compiled around 1520, lists all the choral Masses and Offices throughout the liturgical year, including a weekly Corpus Christi Mass that was celebrated every Thursday.Footnote 25 Much less is known about the musical and liturgical scene at Frederick’s court, but his secretary Georg Spalatin recorded that Frederick heard Mass almost every day and took his Hofkapelle on at least some of his journeys.Footnote 26

VatS 16 and the other Vatican sources do not contain any Eucharistic iconography, but the Missa Pange lingua could have been performed during a Eucharist-centred liturgy such as the Mass for Corpus Christi. In sixteenth-century Rome, the feast was important enough to require the presence of the entire papal chapel, including the Pope.Footnote 27 Four of the five Vatican Missa Pange lingua sources are associated with a member of the Medici family. Claudius Gellandi copied VatS 16 for the Sistine Chapel choir of Pope Leo X (r. 1513–21), a music connoisseur who owned several Alamire manuscripts and has been criticised by both contemporaries and modern historians for neglecting the growing problem of the Reformation in favour of other concerns at the Vatican, including the cultivation of music and the arts.Footnote 28 The Missa Pange lingua is also found in VatG XII.2, a manuscript copied for the Cappella Giulia, and in two sets of partbooks that bear the Medici coat of arms.Footnote 29 The fifth and final Vatican source, VatSM 26, was probably used at Santa Maria Maggiore and may have been copied by a scribe from the French region.Footnote 30 The Vatican Missa Pange lingua sources contain mostly masses but also some motets and other liturgical pieces. This repertory, together with the physical characteristics of these sources, suggests they were utilitarian as opposed to being presentation or display manuscripts.

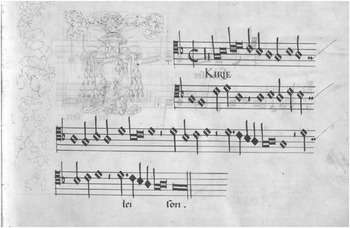

The Missa Pange lingua was probably not performed at all from MunBS 510 because the choirbook was never finished. It is dedicated to the cardinal Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg (1469–1540), whose portrait and coat of arms on the opening folios are only sketched. In addition to the unpainted miniatures, there are empty spaces where initials should be at the beginnings of the subsequent masses. Close study of the script reveals an increasing sense of urgency in the later masses, as if a scribe were hurrying to complete the manuscript for some reason, possibly so a painter could begin work on the opening pages. The sketched coat of arms (Figure 3) lacks the processional cross of an archbishop or papal legate, a detail that indicates the choirbook pre-dates Lang’s promotion to archbishop of Salzburg in June 1519.Footnote 31 Martin Bente originally associated the choirbook with the Bavarian ducal chapel, but, especially considering recent doubts on this claim raised by Birgit Lodes, the unfinished state of MunBS 510 suggests a connection to Maximilian I.Footnote 32 Throughout his political career, the emperor sought to enhance his reputation and legacy through the arts by dedicating projects to family and political colleagues, but often these endeavours remained unfinished, particularly around the time of his death in January 1519.Footnote 33

Figure 3 Lang coat of arms in Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS 510, fol. 2r

While powerful political figures in Rome and elsewhere were enjoying the Missa Pange lingua and exchanging choirbooks amongst themselves, a young Martin Luther was becoming increasingly sceptical of various practices within the Roman Church, including the cult of the Eucharist that was flourishing in Germany. During a Corpus Christi procession in Eisleben in 1515, Luther experienced a frightening epiphany that may have shaped his perception of processions and the feast. Upon seeing the consecrated Host carried by his mentor Johann Staupitz, Luther was overcome by a vision of Christ as judge, an image that would permeate his thoughts and provoke questions concerning such phenomena as the achievement of salvation by grace or works.Footnote 34 Luther later voiced his disapproval of excessive Eucharistic veneration because he believed the Blessed Sacrament was too sacred to be constantly on display and paraded through the streets. After returning to Wittenberg from the Wartburg Castle in 1522, Luther strongly criticised Corpus Christi and its procession, which undoubtedly led to the omission of Corpus Christi in Wittenberg beginning in 1524.

In a sermon delivered in Kemberg on Trinity Sunday in 1524, Luther spoke against Corpus Christi in both Latin and German, describing the feast as a great disgrace (ignominia magna) that resulted in the evil commercialisation (boslich gehandlet) of the Blessed Sacrament.Footnote 35 He noted that while Kemberg would still observe Corpus Christi the following week, the feast had been discontinued in Wittenberg. The church leaders there chose to ‘hide’ or ‘conceal’ the Host rather than process with it through town, as was customary in German communities on Corpus Christi. Luther associated excessive public veneration of the Eucharist with public fornication (scortator publicus) and stated that a Scripture reading was better than ten feast days.Footnote 36 In the coming decades, other Lutheran communities removed Corpus Christi from their liturgical calendars as they established worship practices.Footnote 37 Given the widespread abolition of Corpus Christi in conjunction with Martin Luther’s condemnation of both the feast and endowed votive masses, Lutherans could easily have omitted the Missa Pange lingua from their musical repertories, despite its technical accessibility and authorship by Josquin.

THE ‘RENAISSANCE’ OF THE MISSA PANGE LINGUA IN LUTHERAN NUREMBERG

In addition to an association with seemingly polemical liturgical practices and theology, the Missa Pange lingua faced another challenge in terms of further circulation. While many other masses attributed to Josquin enjoyed widespread distribution courtesy of Petrucci and other Italian printers, the Missa Pange lingua did not appear in print until 1539. In that year, a Nuremberg bookseller named Johannes Ott included the mass in his anthology of thirteen Mass Ordinary settings entitled Missae tredecim quatuor vocum (see Table 3 below for a complete contents list).Footnote 38 Inclusion in Ott’s print allowed the Missa Pange lingua to become part of the German Josquin Renaissance; furthermore, the mass experienced its own rebirth within that larger phenomenon.

The lack of earlier printed Missa Pange lingua sources makes the presence of the mass in Missae tredecim all the more crucial in the further circulation in the sixteenth century following Josquin’s death. A copy of the work landed in the hands of a printer and, as a result, it could finally be distributed throughout Europe – twenty-five years after Petrucci’s third Josquin mass anthology. The print debut of the Missa Pange lingua is even more remarkable, considering Johannes Ott’s profession. He worked in the publishing and bookselling industry – he was not a singer at a church or political court where he would have had constant contact with other singers and composers.Footnote 39 Unlike professional musicians who travelled extensively and had many opportunities to obtain music, Ott’s avenues for music exchange were relatively limited. How, then, did Ott obtain the repertory published in Missae tredecim and his other volumes of Latin polyphony?

The Missa Pange lingua probably reached Johannes Ott through an underground Lutheran network that extended from Bavaria to Wittenberg and included two Lutherans in Nuremberg who were attempting to restore Latin polyphony in their churches. Hieronymous Baumgartner (1498–1565) became the first Kirchenpfleger (church administrator) of Nuremberg in 1533, and Veit Dietrich (1506–49) was a Nuremberg native who accepted a position as preacher at St. Sebald in December 1535 after studying in Wittenberg and serving as Martin Luther’s secretary.Footnote 40 Although no direct evidence of dealings between the church leaders and printers in Nuremberg survives, Baumgartner and Dietrich probably knew they could turn to Ott, Petreius, or the printer Hieronymus Formschneider for any music printing needs.

Following Nuremberg’s official conversion to Lutheranism in 1525, church leaders replaced Latin polyphony with vernacular hymns.Footnote 41 However, the dominance of vernacular liturgical music in Nuremberg would not last for long – it could not, given the positive stance on Latin sacred music taken by both Luther and Philipp Melanchthon, who were influential in shaping Lutheran practices in Nuremberg.Footnote 42 Dietrich and Baumgartner recognised the need for traditional liturgical music and used their leadership positions to mount a restoration of Latin polyphony in Nuremberg. Their efforts coincide with several printed anthologies of Latin polyphony published in Nuremberg between 1537 and 1539, when both Ott and Petreius suddenly turned from printing secular music and focused on older liturgical repertory (Table 2). Veit Dietrich was almost certainly involved with the production of Novum et insigne opus musicum in some capacity, as he received a copy immediately after publication and presented it to his deacons at St. Sebald.Footnote 43

Table 2 Latin polyphony printed by Ott and Petreius, 1537–1539

Unlike Johannes Ott, Dietrich and Baumgartner had the connections to obtain older Latin liturgical music – including the Missa Pange lingua – from Wittenberg and Munich. Both church leaders corresponded with their counterparts in Wittenberg, and Baumgartner maintained a friendship with Ludwig Senfl, who worked for the Catholic Bavarian ducal court after being dismissed from the Imperial court in 1520. Senfl and Lutherans in Saxony and Prussia used Baumgartner as an intermediary to exchange letters, gifts and music.Footnote 44 The Nuremberg churchmen delivered at least one Johannes Ott publication to Saxony, as Dietrich gave Martin Luther a copy of the Magnificat octo tonorum, an anthology of Senfl’s Magnificats published in 1537.Footnote 45

Connections exist between Ludwig Senfl and most of the Latin repertory that Ott printed. In addition to the Magnificat Octo Tonorum, Schlagel names Senfl’s Liber selectarum cantionum and sources that were ‘very closely’ related to the Bavarian court, as were also two of Ott’s sources for the motets found in Novum et insigne opus musicum.Footnote 46 Ott also had plans to publish Heinrich Isaac’s polyphonic Mass Propers (in the possession of Senfl, a student of Isaac) but died before he was able to do so.Footnote 47 Given Senfl’s involvement with all other Latin polyphony collections published by Ott, it is plausible that he also supplied at least a few of the thirteen masses in Missae tredecim. Senfl had access to at least one copy of the Missa Pange lingua with MunBS 510, the unfinished choirbook for Cardinal Lang.Footnote 48 The Nuremberg Lutherans also could have obtained a copy of the Missa Pange lingua from Wittenberg, as it is one of eight Missae tredecim masses preserved among the Electoral Library choirbooks.

Comparative analysis between the Missa Pange lingua readings in Missae tredecim and the earlier extant sources does not yield a precise connection between a specific earlier manuscript and Ott’s edition, but an indirect relationship exists between Missae tredecim and the earlier pool of sources that includes JenaU 21 and MunBS 510.Footnote 49 Moreover, Ott seems to have consulted manuscripts rather than printed exemplars when editing Missae tredecim, which could account for the lack of a direct relationship due to inevitable variants that occur as a result of the transfer from manuscript to print.Footnote 50 In a comparison of Missae tredecim and Liber quindecim missarum, Schlagel observes that while Petreius relied on earlier printed sources (namely Petrucci’s first volume of Josquin masses) when editing his polyphonic mass anthology, Ott ‘seems to have been unaware of, or lacked access to, or purposely eschewed, printed editions’.Footnote 51

According to Ott’s dedicatory preface of Missae tredecim, his motivation for publishing the Missa Pange lingua (and the other masses) was driven primarily by aesthetics and a desire to preserve the works of revered past composers.Footnote 52 Ott does mention the liturgy near the end of the preface and indirectly expresses his desire for Latin polyphony to return to the Nuremberg churches: he hopes the Nuremberg city council will embrace his current endeavour, as the pieces were appropriate not only for leisure activities but also for ‘adorning the sacred’.Footnote 53 It is not surprising that Ott avoided discussing issues of liturgy and doctrine in his preface addressed to the city council. For both marketing and diplomatic purposes, it was in his best interest to present Missae tredecim as a neutral product in terms of confession.Footnote 54

Nevertheless, Missae tredecim marks a significant turning point in the confessional orientation of the Missa Pange lingua; Ott probably obtained the mass through a network of Lutheran leaders, printed it in a Lutheran city and dedicated the edition to a Lutheran town council. It is also through Missae tredecim that the Missa Pange lingua became a commercial product rather than a private gift exchanged between family members and political colleagues.Footnote 55 The Missae tredecim allowed the work to cross a confessional boundary and acquire new performance contexts in early Lutheran communities, where both seasoned aristocrats and young school children could experience the mass.

There are nineteen extant exemplars of Missae tredecim (along with four other documented exemplars that are currently lost) scattered throughout Europe.Footnote 56 The known copies of Missae tredecim (a complete listing is provided in the appendix) reveal that the Missa Pange lingua reached nearly every region of Germany and, although Ott did not attach a confessional label to the book, the publication was primarily popular among Lutherans.Footnote 57 Several exemplars can be traced to Lutheran Gymnasiums, where students probably performed the masses during music classes, liturgical services, or recreational time. Two copies from the Regensburg Gymnasium Poeticum are currently at the Regensburg Bischöfliche Zentralbibliothek, and the Zerbst exemplar is held today at the Gymnasium Francisceum where it was originally used.Footnote 58 Other Missae tredecim copies that were probably used in Lutheran schools include the Heilbronn, Rostock and Zwickau exemplars, along with a documented copy from the Thomaskirche in Leipzig that is currently lost.Footnote 59

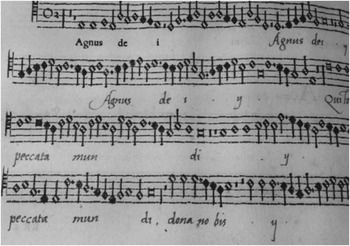

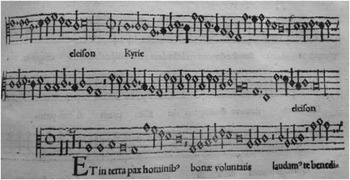

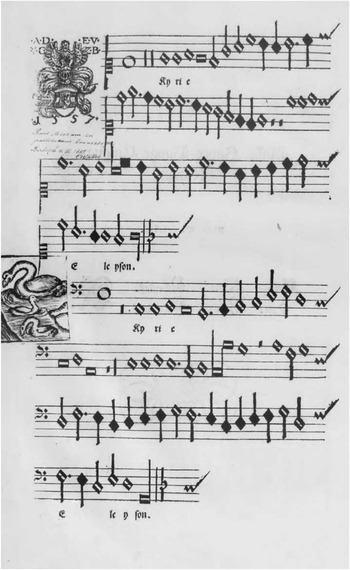

The handwritten markings in Missae tredecim exemplars offer insight into where the owners might have used the edition and which masses they performed. A closer examination of the handwritten annotations in conjunction with the provenances of two Missae tredecim exemplars held at the Kassel Universitätsbibliothek and the Heilbronn Stadtarchiv provides convincing evidence that Lutherans used the masses in this print – including the Missa Pange lingua – for both liturgical and pedagogical purposes. The exemplar from the Kassel Universitätsbibliothek almost certainly came from the Hofkapelle of Philipp der Großmütige (1504–67); it is listed in a 1613 inventory of his chapel repertory, along with the Rhau and Petreius editions found in the same bound volume.Footnote 60 In the final Agnus Dei of the Missa Pange lingua, the entire text is written by hand underneath the notes (Figure 4), a few notes are corrected in the cadence of the final Agnus of the Missa O gloriosa, and there is one annotation that suggests liturgical use: the Credo of the Missa Sub tuum praesidium contains a handwritten caesura after the phrase ‘descendit de coelis’ in each partbook (Figure 5). In Lutheran sources that contain polyphonic masses, including RegB C 100, a Missa Pange lingua source discussed below, the Credo movements sometimes end before the ‘Et incarnatus’ section. Liturgical instructions in multiple Lutheran Kirchenordnungen specify that during a Sunday service the Creed would be sung first in Latin by the choir and then the congregation would sing it in German, usually in the form of the chorale Wir glauben all in einem Gott. An abbreviation of the Latin Credo is not articulated in the Kirchenordnungen, but such a decision would make sense given the length of the polyphonic Credos and the Lutherans’ flexible approach towards liturgy.Footnote 61

Figure 4 Agnus Dei III, Missa Pange lingua, Tenor partbook, 4o Mus. 63 b kk2v, Universitätsbibliothek Kassel, Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel. Photo: Author

Figure 5 Credo, Missa Sub tuum praesidium, Tenor partbook, 4o Mus. 63 b, NN Universitätsbibliothek Kassel, Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel. Photo: Author

The Heilbronn Missae tredecim, bound with a copy of Novum et insigne opus musicum II, was probably bequeathed to the Heilbronn Gymnasium and used between the years 1576 and 1612.Footnote 62 An important indicator of liturgical use is the one-page insert found at the beginning of each partbook (Figure 6). These pages contain handwritten polyphonic responses to the Preface in both Latin (‘et cum spiritu tuo’) and German (‘und mit deinem geist’).Footnote 63 This exemplar contains several practical handwritten annotations that were intended to aid singers during a rehearsal or church service.Footnote 64 Several masses have tiny numbers written above groups of rests that indicate how many beats the singer should pause before beginning the next phrase. There are rest numbers in the Missa Pange lingua (Figure 7) and mensuration signs are added before the ‘et vitam venturi’ section at the end of the Credo.

Figure 6 Preface insert in tenor partbook, Heilbronn Stadtarchiv. Photo: Author

Figure 7 Kyrie and Gloria, Missa Pange lingua, Contratenor partbook, Heilbronn Stadtarchiv. Photo: Author

Whereas multiple Lutheran communities owned Missae tredecim exemplars, there is no direct evidence that the figure most central to the Lutheran movement – Martin Luther himself – possessed a copy of the publication. However, Luther’s physician provides an invaluable account of the theologian and amateur musician singing from similar music prints in a recreational setting and making handwritten corrections to the prints. The oft-cited passage written by Matthäus Ratzeberger reads: ‘Luther was also accustomed immediately after the evening meal to fetch from his study his partbooks and with his table companions, who delighted in music, made music together with them.’ Ratzeberger continues: ‘It is noteworthy that from time to time when he [Luther] found false notation in a new song [they were singing], he immediately took it away and saw that it was correctly set and rectified.’Footnote 65 Luther himself may or may not have sung from Missae tredecim, but copies of the edition can be traced to two of Luther’s political colleagues. Duke Albrecht of Prussia obtained at least one copy of Missae tredecim along with the two Novum et insigne opus musicum volumes, the Magnificat octo tonorum, and Petreius’s Liber quindecim missarum and Trium vocum cantiones.Footnote 66 The Missae tredecim exemplar currently held at the Jena Thüringer Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek was probably purchased for the library of Elector Johann Friedrich (1503–54), nephew of Frederick the Wise.Footnote 67

A MASS CHOSEN BY LUTHERANS

Lutheran owners of the Missae tredecim had the opportunity to perform the Missa Pange lingua, but they were not obligated to act on that opportunity. Evidence in both printed and manuscript sources, however, reveals that Lutherans specifically chose Josquin’s Corpus Christi mass for performance and further dissemination. In the nineteen extant Missae tredecim exemplars, fifteen contain at least one handwritten marking that appears to be from the mid- to late sixteenth century, when Lutheran liturgical practices stabilised. The Missa Pange lingua is one of the masses with the most handwritten annotations among these fifteen exemplars (Table 3). The Missae tredecim copies from Heilbronn, Kassel, Rostock, Zwickau, Paris, Regensburg (both A.R. 91 and C 62a), and the tenor partbook from Vienna all have at least one discernable handwritten marking in the Missa Pange lingua. Footnote 68

Table 3 Missae tredecim contents and handwritten markings in extant copies

The Missa Pange lingua also appears in more extant post-1540 manuscripts than any of the other twelve masses in Missae tredecim (Table 4). The six manuscript sources are concretely linked to Lutherans and date from approximately 1550, about a decade after the publication of Missae tredecim, when liturgical practices of many Lutheran communities began to crystallise (Table 5). Missae tredecim continued to be a catalyst for the Lutheran transmission of the Missa Pange lingua, as readings of the mass in three of the German manuscripts (RosU 49, LeipU 49/50 and RegB C 100) indicate that their scribes used the Nuremberg print as their copying exemplar.Footnote 69 However, the scribes of these manuscripts did not mindlessly copy the Missa Pange lingua as part of a series of works from Missae tredecim or in an attempt to copy all available Josquin-attributed masses. The Missa Pange lingua is the sole Missae tredecim mass copied in four manuscripts, and only one other mass from Ott’s collection appears in the other two manuscripts.Footnote 70

Table 4 Manuscript sources and pre-existent melodic material for Missae tredecim masses

Table 5 Lutheran manuscript sources of Missa Pange lingua

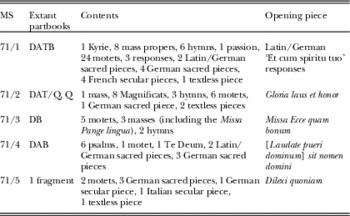

Three Missa Pange lingua manuscripts do not bespeak a direct relationship to Missae tredecim, but they are separated from the earlier pool of sources from the Vatican and Alamire workshop because they lack the second Agnus Dei section. In addition to RosU 49 and a Missae tredecim exemplar, Duke Johann Albrecht I of Mecklenburg-Schwerin owned a third copy of the Missa Pange lingua. RosU 71/3 is one of five worn, utilitarian sets of paper partbooks held at the Rostock Universitätsbibliothek with the shelfmark 71 (Table 6).Footnote 71 The partbooks must have survived as a group, although various folios and some entire voice partbooks are missing; in the case of RosU 71/3, only the discantus and bassus partbooks survive. An entry in the ducal library catalogue indicates that these ‘Rostock 71’ partbooks were in the possession of Duke Johann Albrecht I, an advocate for both Lutheranism and music.Footnote 72 While Johann Albrecht’s three Missa Pange lingua copies may seem to be an anomaly, this source situation is probably indicative of the music holdings in other wealthy churches and courts: printed editions were purchased, choirbooks were given as gifts, and utilitarian partbooks were copied, but only fragmented evidence of these actions survive today in the form of extant prints and manuscripts.Footnote 73

Table 6 Overview of the Rostock Universitätsbibliothek Mus. Saec. 71 Manuscripts

Lutheran interest in the Missa Pange lingua extended into the Czecho-Slovak region. BrnoAM 15/4 and a second choirbook containing Latin polyphony, BrnoAM 14/5, belonged to the German-speaking Lutheran community associated with the church of St James in Brno.Footnote 74 BudOS MS 8 is one of nearly fifty sets of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century music prints and manuscripts from the church of St Aegidius in Bardejov, a city in eastern Slovakia.Footnote 75 The repertory in BrnoAM 15/4 and BudOS MS 8 suggests a Saxon origin for the exemplars of these pieces and possibly the manuscripts themselves, as many of the pieces are also found in sources from Leipzig and the Electoral Library.Footnote 76

All six later manuscript readings of the Missa Pange lingua were suitable for use in the Lutheran liturgy.Footnote 77 In the case of RosU 49, Lothar Hoffmann-Erbrecht observed that the repertory therein was representative of Lutheran music in Saxony and could have provided a foundation of liturgical music for Duke Johann Albrecht as he promoted Lutheranism in the Mecklenburg region.Footnote 78 In the dedicatory letter of RegB C 100 addressed to the Lutheran city council of Regensburg, the scribe Johannes Buechmaier – a cantor at the Regensburg Gymnasium Poeticum – explicitly states that he copied the following masses and introits ‘for your church’.Footnote 79 Four manuscripts (LeipU 49/50, RosU 49, RosU 71/3, BudOS MS 8) contain the purely functional polyphonic Preface responses similar to those found in the Heilbronn Missae tredecim. Footnote 80

Two manuscripts contain altered versions of the Missa Pange lingua that reflect the choices Lutherans made when performing it. The Missa Pange lingua readings in the sources directly related to Missae tredecim – RosU 49, LeipU 49/50 and RegB C 100 – all differ from the print to some degree. The reading in RosU 49 is the most similar to Missae tredecim, with only a handful of minute differences across all mass movements and voice parts.Footnote 81 The differences between LeipU 49/50 and Missae tredecim seem to be the result of hurried or careless copying; in addition to a few stray variants, several brief passages are omitted in each voice.Footnote 82 In contrast, the Missa Pange lingua in RegB C 100 deviates from Missae tredecim in a more purposeful way. Buechmaier indicated in both the preface and the index that the masses he did not compose contained his own ‘resoluta’, alterations which include a nearly universal use of the cut-C signature and occasionally rewriting technically complex passages.Footnote 83 These changes reflect Buechmaier’s attempt to make older polyphony technically accessible to musicians living in the later sixteenth century and, therefore, his expectation that the masses in RegB C 100 would be performed.

The Missa Pange lingua reading in BudOS MS 8 lacks the middle section between ‘et homo factus est’ and ‘Confiteor unum baptisma’ in the Credo, another example of an abridged movement alongside the Missa Sub tuum praesidium Credo in the Kassel Missae tredecim exemplar (described above and pictured in Figure 5). The masses in RegB C 100 suggest that this phenomenon of abbreviated Mass Ordinary sections was a deliberate performance practice choice made by early Lutherans. Many of the Mass Ordinary settings in RegB C 100 contain similar omitted sections, including the masses composed by Buechmaier himself (Table 7). Since it is impossible that Buechmaier did not have access to sections of his own compositions, it stands to reason that at least some of the omissions in RegB C 100 as well as other Lutheran manuscripts were deliberate choices made by the copyists and not the result of lacking access to complete copying exemplars of these masses.

Table 7 Mass Ordinary settings in RegB C 100

Although they discontinued the original performance contexts of the Missa Pange lingua – Corpus Christi and votive masses – Lutherans throughout Germany and the Czecho-Slovak region selected the mass for performance in their schools and churches and for preservation in manuscripts created specifically for their communities. The sources discussed above may appear to be ordinary sixteenth-century prints and manuscripts – even the handwritten annotations found in the Missae tredecim exemplars are normal editorial markings – but they serve as evidence that Lutherans actively engaged with the Missa Pange lingua. They marked up the mass in their copies of Missae tredecim, they copied the mass into manuscripts created specifically for their communities, and in some cases they altered the Missa Pange lingua to make it more suitable for their performance needs.

TOWARDS A LUTHERAN UNDERSTANDING OF PANGE LINGUA

The Missae tredecim edition and subsequent manuscript sources firmly establish the interest Lutherans took in the Missa Pange lingua and solidify its place in the early Lutheran repertory. Nevertheless, these sources do not reveal Lutherans’ perception of this mass in terms of its association with multiple polemical topics of the Reformation beyond the inclusion of ‘Pange lingua’ in the title in five of the six manuscripts.Footnote 84 There are two printed Lutheran sources of the Missa Pange lingua from the mid-sixteenth century that offer some insight into how Lutherans perceived its earlier Catholic identity. It seems that Lutherans were aware of the earlier context of the Missa Pange lingua but at least in these two cases were comfortable with the mass, despite its borrowed melody and the allusions to controversial theology and liturgical practices. One print implies an emphasis of aesthetics and educational value over objectionable doctrine, while the other directly engages with multiple aspects of the Missa Pange lingua’s former life as a work associated with Corpus Christi and Eucharistic devotion.

In 1545, the Wittenberg printer Georg Rhau included the Pleni sunt and Agnus II sections from the Missa Pange lingua in his Bicinia gallica, latina, germanica (RISM 15456), a printed collection of duet sections extracted from larger compositions. The Missa Pange lingua duets, like other works in the collection, appear as contrafacta: the Pleni sunt section is entitled Quis separabit nos and contains text from Romans 8 (35; 38–9), while the Agnus II is entitled Exaudi Domine and contains text from Psalm 26 (7, 9, 11, 14).Footnote 85 In another music print from 1542 titled Sacrorum hymnorum liber primus, Rhau compiled a collection of 134 hymns for Vespers services held at Lutheran schools.Footnote 86 He organised the hymns according to the liturgical calendar with pieces from the Proper of the Time followed by the Proper of the Saints. Most feasts have between two and four pieces whereas the solemn feasts have more: there are eight hymns for Christmas (including the vigil and Christmas Day), ten for Easter (including the vigil), six for Pentecost, and six for the Assumption of Mary. Corpus Christi dominates the list with thirteen items, nine of which are settings of Pange lingua stanzas that paraphrase the chant melody. Sacrorum hymnorum also contains music for five Marian feasts and feasts of non-biblical saints.

Rhau was aware that some of the hymns in Sacrorum hymnorum conflicted with Lutheran beliefs and liturgical practices. In both the preface and the dedicatory letter to the Lutheran town of Joachimsthal, he states that some of the hymn texts contain false doctrine and explains that he included the questionable hymns in his collection because of their aesthetic and educational value.Footnote 87 Rhau does not specifically mention Corpus Christi, but his sentiments on ‘false doctrine’ are applicable to the feast; he was probably aware of Martin Luther’s objection to associated rituals such as processions, Benediction services and Corpus Christi itself, not to mention the Eucharist debates in sixteenth-century confessional discourse. Given that Sacrorum hymnorum was published three years before Bicinia gallica, Rhau probably held this attitude towards similar pieces with controversial liturgical and theological topics found in these other publications, although presenting the pieces as contrafacta as he did in Bicinia gallica masks their original identities and associated liturgical functions.Footnote 88

Georg Rhau does not speak for every Lutheran, but he was an influential music publisher working in Wittenberg alongside Luther, Melanchthon and their students. He marketed his prints to Lutherans and would have avoided controversial statements and musical material that conflicted with the views of his colleagues. Lutheran leaders from Germany and regions further east studied in Wittenberg and returned to their communities with education, values and liturgical and educational materials for their churches, including music. Thus, it is reasonable to believe that Reformers educated in Wittenberg might have adopted Rhau’s sentiments towards music and accepted the older Latin repertory without reservation.

Whereas Rhau accepted the Missa Pange lingua and other potentially polemical Catholic works for aesthetic and educational reasons, the final Missa Pange lingua source addressed in this study reveals an intimate engagement with the borrowed Corpus Christi melody. This single print of the mass contains added text and images not found in any other Missa Pange lingua source – Catholic or Lutheran. It is one of seven single prints of four-voice Mass Ordinary settings held today in a bound volume at the Hochschul- und Landesbibliothek RheinMain in Wiesbaden.Footnote 89 The prints are in choirbook format and no printer or publisher is indicated, but they contain the coat of arms and motto of Anton von Isenburg, count of Büdingen (1501–60). Unlike the products of Johannes Ott and Georg Rhau, these prints do not have a commercial purpose and it is quite possible that the seven prints are unica. They were intended for private use by Isenburg and did not circulate in mass quantities across Europe, but they make a significant contribution to the primary question concerning the Lutheran use of Missa Pange lingua: to what extent did Lutherans associate this polyphonic mass with Eucharistic devotion and the Corpus Christi hymn penned by Thomas Aquinas?

Anton von Isenburg embraced Lutheranism as early as 1529 and eventually set up a print shop in his castle, known as the Ronneburg.Footnote 90 Along with the seven Mass Ordinary prints, two other items were produced in the count’s print shop: the title page of his account books for 1557 and an edition of the Confessio Augustana (Augsburg Confession), also from 1557.Footnote 91 Both items have title-page ornaments similar to those on the mass prints, and the Confessio Augustana bears Isenburg’s coat of arms and motto: ‘Armut und Überflus gibt zeitlich Betrübnis’ (poverty and abundance give timely sorrow).

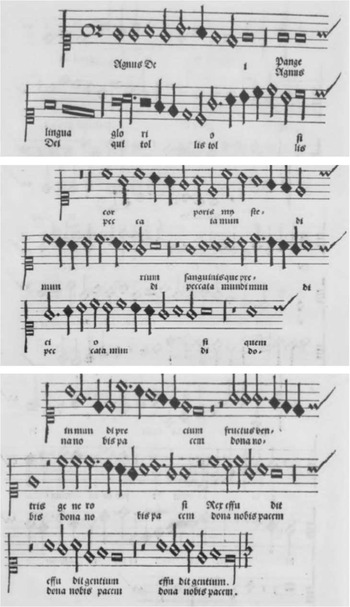

The Ronneburg Missa Pange lingua print contains all movements of the mass, including the Agnus II duet that is missing from Missae tredecim and other Lutheran sources.Footnote 92 The opening Kyrie folios of each printed Ronneburg mass contain two simple engraved images: Isenburg’s coat of arms next to the discantus voice and another object adjacent to the bassus voice that varies with each mass. The opening page of the Missa Pange lingua is adorned with a family of swans (Figure 8), which may hold a symbolic meaning relevant to both Catholic and Lutheran Eucharistic theology. In his study of the Confessio Augustana edition from the Ronneburg, Josef Benzing briefly mentions the various images in the Ronneburg mass prints and states it is probable that the swan image was originally printed in a ‘Volksbuch’ or fairy-tale book.Footnote 93 It appears that the image was cut and pasted into the book prior to the printing of the music, as the C-clef overlaps the image with the bottom of the clef almost touching the larger swan. Among the many legends and symbolism concerning swans in classical and medieval animal lore, the most likely symbolic connection between the swans and the Missa Pange lingua comes from German folklore.Footnote 94

Figure 8 Kyrie, Ronneburg Missa Pange lingua, Wiesbaden, Hochschul- und Landesbibliothek RheinMain, Sig. gr. 2 Qt 31

Swans in medieval German legends bear symbolic meanings pertinent to a Eucharistic tenet shared by Catholics and Lutherans: transformation and the concealment of a spirit or human under another form.Footnote 95 In Germanic myths and legends, humans, angels and other spirits were often concealed under the form of the elegant white bird.Footnote 96 In the legend of the Swan Knight, preserved in numerous medieval literary works and made famous by Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin, Lohengrin the ‘Swan Knight’ arrives and departs from the princess Elsa in a boat driven by a swan. Elsa later discovers that the swan is actually her brother Gottfried, who was transformed into a swan by a sorceress and is eventually changed back into a human.Footnote 97 The Swan Knight legend is sometimes associated with the Swan Children fairy tale recorded by the Brothers Grimm in which a group of siblings is transformed into swans; the parent swan and two younger swans in the Ronneburg edition could very well allude to this legend. The Catholic and Lutheran confessions both subscribe to the belief that bread and wine are transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ during the celebration of the Eucharist. While Martin Luther and his followers did not accept transubstantiation – the rationalised explanation for this transformation – they still acknowledged a physical presence of Christ in the Eucharist and, therefore, the transformation and supernatural concealment of a person within a non-human form.

In addition to the swans, the Ronneburg Missa Pange lingua features an explicit reference to the Pange lingua hymn not found any other source: the discantus voice of the final Agnus Dei contains the text of the first verse of Aquinas’s Pange lingua printed above the standard Agnus Dei text (Figure 9).Footnote 98 This is not only unusual for a Lutheran source, but for mid-sixteenth century Mass Ordinary sources in general.Footnote 99 The added text in the superius voice of the Agnus Dei in the Missa Pange lingua is relatively simple to explain in terms of the music itself. This voice contains a long-note paraphrase of the chant melody while the lower voices provide a supporting texture. Moreover, in a Mass Ordinary setting, the final Agnus typically contains a unique feature that unifies the entire work or provides a contextual commentary. When the liturgical functions of the Agnus Dei and Pange lingua are considered together, however, the added hymn text in this source represents a climactic point in the polemical side of Catholic–Lutheran Eucharistic theology.

Figure 9 Superius voice of Agnus Dei III, Missa Pange lingua, Wiesbaden, Hochschul- und Landesbibliothek RheinMain, Sig. gr. 2 Qt 31

In the Catholic Mass, the Agnus Dei was sung at the conclusion of the Pax Domini and coincided with the fraction, which is the breaking of the consecrated Host by the priest. The fraction was originally an Eastern practice that symbolised the Passion and death of Christ, a meaning held in the Western church as well.Footnote 100 The prominent mention of a (sacrificial) lamb in the Agnus Dei text reinforces the idea that the Mass itself was a sacrifice, a concept that Luther passionately refuted. The Pange lingua text contributes an additional layer of controversial symbolism to this movement of the mass. Charles Riepe explains that the period of time between the consecration of the Host and Communion ‘represents a reverential and, at the same time, humble greeting of Him who has been made present under the form of bread’, and describes how the silence during this interval was replaced by hymns which ‘were engendered not only by their Latin genius but by a new attitude towards the Sacrament – hymns like Ave verum corpus and O Salutaris hostia’.Footnote 101 Martin Luther may have defended the idea of Christ’s physical presence in the Eucharist against his fellow Reformers, but he did not believe that the systematic theory of transubstantiation (the ‘new attitude’ to which Riepe refers) should be a binding dogma, nor did he accept the teaching that the Mass was a sacrifice.

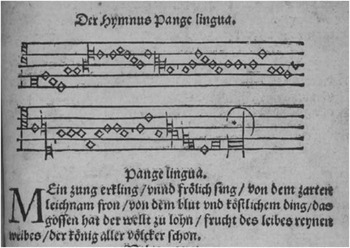

Whether it was Anton von Isenburg himself or his printer, someone permitted the Pange lingua text to appear in the Ronneburg edition.Footnote 102 Despite the theological differences and Lutheran abolition of Corpus Christi, this should not surprise us. Lutherans wanted to silence the context of Pange lingua rather than the text and melody. Although they suppressed the Eucharistic rituals during which Pange lingua was sung, they circulated both Latin and German versions of the hymn. Along with the many Pange lingua settings in Rhau’s Sacrorum hymnorum, polyphonic versions of the hymn survive in Lutheran manuscript sources, including LeipU 49/50 and RosU 71/3.Footnote 103 Moreover, a German version of the hymn, Mein Zung erkling und frölich sing, appeared in multiple editions of hymnals titled Enchiridion. Footnote 104 Two rival publishers in Erfurt, Johannes Loersfelt and Mathes Maler, printed the first Enchiridion hymnals in 1524, the Nuremberg publisher Hans Hergott produced an Enchiridion based on the Erfurt model in 1525, and numerous other Lutheran cities followed suit with their own reprinted and expanded Enchiridia.Footnote 105 Although Mein Zung erkling did not become one of the canonical Lutheran chorales later set by Johann Sebastian Bach, it circulated in these popular vernacular hymn collections. For example, Bartlett Butler identified the hymn in fourteen sixteenth-century Nuremberg hymnals beginning with Hergott’s 1525 edition.Footnote 106

When stripped of its original performance contexts – Corpus Christi Vespers, processions with the Eucharist and periods of Eucharistic adoration – most of the Pange lingua text itself does not present any explicitly objectionable concepts and actually highlights the similarities between Catholic and Lutheran Eucharistic theology rather than the differences (Table 8).Footnote 107 The first stanza is essentially a summary of the hymn itself and the Christian salvation narrative. The second and third verses follow with a description of Christ’s life from his birth to the Last Supper, an appropriate event to highlight in a Eucharistic hymn. The fifth verse describes the adoration of the Host as a new form of worship that replaced Old Testament rituals and the final verse is a concluding doxology.

Table 8 Pange lingua text – Latin and English

The first part of the fourth stanza would have been the most objectionable to Martin Luther and his followers because it references transubstantiation in the first two lines.Footnote 108 Most Lutheran polyphonic Pange lingua settings avoid the fourth stanza – Georg Rhau’s Sacrorum hymnorum includes settings of all Pange lingua stanzas except the fourth – but the early Enchiridion hymnals from Erfurt and Nuremberg reveal an intriguing engagement with this verse. Butler observed that the Nuremberg Enchiridia retained a very close translation of the fourth verse, including the reference to transubstantiation, but the Erfurt Enchiridia contained an altered version of Mein Zung erkling as early as 1527.Footnote 109 In fact, these hymnals contain two versions of Mein Zung erkling: the original with the transubstantiation reference and the corresponding Latin incipits above each verse, and the second version with a more liberal translation of Aquinas’s hymn (see Figure 10 for a page from the hymnal and Table 9 for the two complete texts).

Figure 10 Melody and opening verse of Mein Zung erkling. Enchiridion (Erfurt: Maler, 1527), fol. 33v. Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek

Table 9 Two versions of the German Pange lingua from the 1527 Erfurt Enchiridion

Whereas the original Mein Zung erkling retains the ‘word made flesh turning true bread into flesh’ line, the ‘noch eynmal’ version aligns more precisely with Lutheran Eucharistic theology. Unlike fellow reformers such as Huldrych Zwingli, who rejected any physical presence of Christ in the Eucharist, Martin Luther consistently argued in favour of a physical presence in the bread and wine.Footnote 110 However, Luther taught that this physical presence must be accepted based on faith alone as opposed to a rationalised explanation such as transubstantiation. Thus, the differences between Catholic and Lutheran Eucharistic beliefs are distinct, but subtle. In place of the bread/flesh/word lines, the initial lines in the fourth verse of the ‘noch eynmal’ version discuss the power of God’s word and how it can accomplish whatever God wills. The most specific reference to the Eucharist in the ‘noch eynmal’ version is found in the third verse, which describes how Christ, ‘with a great miracle’ (grossem wunder), left his Testament under ‘extraordinary’ bread and wine (brodt vnnd wein besonder). This wording conveys that the bread and wine underwent a miraculous change rather than being a mere symbol, but does not specify what that miracle is or how the change happens. It is also noteworthy that the fourth and fifth stanzas of the original Latin Pange lingua emphasise a tenet of Luther’s theology in regards to the Eucharist as well as the salvation of one’s soul: faith alone is sufficient. Immediately after the transubstantiation reference in the fourth stanza, Aquinas writes (emphasis mine), ‘et, si sensus deficit, ad firmandum cor sincerum, sola fides sufficit’. Likewise, the fifth stanza concludes with the line ‘praestet fides supplementum, sensuum defectui’.

Returning to the Missa Pange lingua, the Rhau and Ronneburg publications demonstrate two different ways that Lutherans could negotiate the controversial aspects of the mass, assuming that the people involved with its performance and distribution were cognisant of sixteenth-century Eucharistic polemics and the intricate theology behind those polemics. While educated members of the Lutheran community probably were aware of the ongoing discussions involving the Eucharist within liturgy and theology, the crowds of common people witnessing the Reformation from the church naves were not. Given this disparity in liturgical and theological knowledge, it may seem that the controversial contexts of the Missa Pange lingua would not be significant in the greater picture of the Reformation, but quite the opposite is true for this particular mass. Because Pange lingua was a popular hymn for Corpus Christi processions, people of all classes and education levels would have heard it in the streets and associated it with the lavish festival focused on the Blessed Sacrament.Footnote 111 It may be more difficult to discern whether the average churchgoer would have understood liturgical meanings behind less common borrowed melodies in masses, but listeners of the Missa Pange lingua in the mid-sixteenth century undoubtedly would have recognised the melody from the Corpus Christi festivities.Footnote 112

Sixteenth-century Christians had access to the Catholic context of Pange lingua via processions, and those who could afford printed books also had access to Pange lingua within a Lutheran context through the Enchiridion hymnals. These music books were intended for private, individual use in order for people to learn the words of Latin hymns and to practise singing them in their native language.Footnote 113 Melodies for the hymns did not always accompany the text, but in the case of Mein Zung erkling in Maler’s 1527 Enchiridion, the Gregorian Pange lingua melody is provided (see Figure 10 above). The wide circulation of Enchiridion hymnals exposed the general Lutheran population to at least some version of Pange lingua, even if the people were not educated enough to understand the complex and polemical Eucharistic theologies, or were not old enough to remember Corpus Christi processions and other Catholic rituals involving Pange lingua and the Eucharist.

There is remarkable evidence that both the German and Latin versions of Pange lingua were part of Lutheran musical life, despite the original liturgical contexts of the hymn being quite polemical in the sixteenth century. It stands to reason that if Lutherans did not take issue with the hymn, they should not take issue with a mass setting based on that hymn. Nevertheless, it is worth pausing to consider once again the relationship between a polyphonic work and its borrowed melody. It may have been easy for Lutherans to silence the context of Pange lingua (Corpus Christi, Eucharistic processions, etc.) and continue singing the hymn text and melody for their own devotional and pedagogical purposes, but the hymn acquired further problematic contextual overtones when fused with the text of the Mass Ordinary. In the case of the Missa Pange lingua, Lutherans had to negotiate not only the Gregorian melody originally associated with Corpus Christi and transubstantiation, but the objectionable practice of votive masses and the general tenet of the Mass as a sacrifice, although Martin Luther’s endorsement of the Mass Ordinary texts certainly helped with the final point.

CONCLUSION

Although the Missa Pange lingua began its life as a Catholic work associated with Corpus Christi and the trend of Eucharistic devotion rooted in medieval thought and ritual, the mass became part of the Lutheran Latin repertory throughout Germany and central Europe. The Lutheran interest in the Missa Pange lingua caused the mass to be distributed more widely and resulted in new performance contexts that were liturgical, pedagogical and recreational. An ironic aspect of the sixteenth-century transmission of the Missa Pange lingua – along with other Latin polyphonic repertory – is that the two institutions that vehemently fought the spread of Lutheranism, the Holy Roman Empire and the Vatican, also inadvertently cultivated music for the movement. Given the theories involving Johannes Ott’s acquisition of the Missae tredecim repertory from the former Imperial court musician Ludwig Senfl and the Wittenberg Electoral Library, the Holy Roman Empire was probably a direct supplier of liturgical music for the Lutheran movement.

We cannot know the sentiments of every individual Lutheran who transmitted or performed the Missa Pange lingua and why they chose to do so. Nevertheless, there is no evidence of Lutherans aligning the mass – or its borrowed material – with negative opinions of Corpus Christi such as those expressed by Martin Luther in his Kemberg sermon. Instead, Lutherans were indeed comfortable incorporating the text and melody of Pange lingua into their repertory, whether they chose to do so because they found the mass aesthetically pleasing or because they interpreted the hymn in a way that conformed to their own Eucharistic theology. Meanwhile, Catholics in Germany continued to observe Corpus Christi throughout the sixteenth century. In fact, the Eucharist became a powerful rhetorical device for the Counter-Reformation effort of the Catholic Church; Alexander Fisher referred to the Eucharist as ‘arguably the most powerful and controversial symbol in the Catholic arsenal’.Footnote 114 Nevertheless, there are no extant Germanic Missa Pange lingua sources associated with the Counter-Reformation efforts of the Catholic Church.Footnote 115

The Lutheran reception of the Missa Pange lingua is a striking example of how Christians who broke away from the Roman Church still utilised its music for their own purposes, but it is also significant in the current reception of the mass. Editors of the two earliest modern editions of the mass, Otto Kade and Friedrich Blume, both consulted Missae tredecim as their primary source.Footnote 116 At the International Josquin Festival-Conference in 1971, Blume described how he and his students studied the mass in 1927 after a student discovered Kade’s edition in the Prussian State Library.Footnote 117 Had the Missa Pange lingua not appeared in Missae tredecim and experienced a ‘Renaissance’ in the early Lutheran church, its life in the twentieth century might have been very different. Finally, the sixteenth-century Germanic reception of the Missa Pange lingua reveals that a borrowed melody in a mass may only be a single layer in the initial performance and reception history of that mass, thus warranting consideration of this mass – and perhaps many others – within the musical histories of both the Catholic and Lutheran confessions.

APPENDIX

Known Copies of Missae tredecim