Introduction

Who wrote ancient Chinese books, who edited them, and how was a writer's labor divided from an editor's (if at all)? How are books remade in the processes of transmission and interpretation? This article explores aspects of the formation of one book, the Laozi 老子, primarily at and between two levels of description: that of the fixed book or canon, and that of the (ostensibly fixed) zhang 章 (textual unit; chapter), usually demarcating a single recognizable idea or maxim.

John B. Henderson's Scripture, Canon, and Commentary sets forth several interpretive assumptions shared by diverse commentarial traditions.Footnote 2 The first is that canons are comprehensive and the second is that canons are well-ordered and coherent.Footnote 3 “Comprehensive,” as applied here, means that they are assumed to be all-encompassing and complete; “coherent” means that they present a single, unified, and comprehensible point of view. The two are not unrelated; the reason canons can be viewed as comprehensive derives in part from their diverse and varied contents. Such a diversity of contents, however, does not often emerge from a single source, nor does it become well-ordered and coherent of itself. Below, I am concerned not only with comprehensive books, but also with their parts. It has become common to speak of these parts—the zhang that Rudolf Wagner proposed as the “molecules” of early Chinese literature—as relatively coherent structures, in contrast to the books they formed.Footnote 4 Nonetheless, by peering closely at the seams along which canons were stitched and glued, I hope to show that the internal, cohesive forces that hold these discrete parts together share more in common than we thought with the intermolecular forces by which books cohere.

The Laozi has been a ruler's handbook, a religious scripture, and a guide for self-cultivation, among other things. Although its transmission and interpretation have already generated over a thousand titles,Footnote 5 new sources—ancient manuscript versions of the text—that have come to light in recent decades now offer unprecedented insight into the formation and early transmission of the text. In addition to Laozi manuscripts from late antiquity and medieval times removed from the library cave at Dunhuang,Footnote 6 several earlier Han and Warring States manuscripts have been unearthed recently, beginning with two early Western Han copies on silk excavated at Mawangdui in Changsha, Hunan, in 1973,Footnote 7 three bamboo manuscripts containing Laozi material excavated from Guodian, Jingmen, Hubei, in 1993 (estimated to have been buried around 300 b.c.e.),Footnote 8 and, most recently, a nearly complete version of the Laozi obtained by Peking University in 2009 (herafter “Beida Laozi”), which appears to have been written in the middle of the Western Han.Footnote 9 The latter manuscript is the first explicity labeled as a canon (jing 經). All of these texts shed light on different aspects of the Laozi's textual formation, and they reveal struggles at both the molecular and organismic levels to make a canon that is coherent, well-ordered, and comprehensive.

Nearly fifty years ago, as leading scholars began to digest evidence from the Mawangdui manuscripts, it was commonplace to voice hopes about recovering an urtext of the Laozi.Footnote 10 Whether this ostensible point of origin marks an authorial or editorial event was not then, and is not now, a matter of consensus.Footnote 11 The quest for the urtext of the Laozi, however, is not very fashionable of late, not least because the discoveries at Guodian produced three manuscripts containing Laozi material with a completely different and seemingly random order of zhang. These texts, and the narratives of textual accretion they seem to enable, has further shaken our faith in the existence of a single historical Laozi, and shifted attention to the collective actions of the many nameless scribes—the invisible hands of manuscript culture, operating under a model in which editorial work is understood to be at the center of school-based textual production.Footnote 12

Whether one subscribes to a model in which the Laozi was produced by an author, a school, or a set of historical processes, the sources we have clearly demonstrate that Laozi—the book as we know it—was altered and refined by editors and scribes. Its zhang, the molecules of its textual matter, the cells of its organism, appear to have evolved early on as motile creatures, such that, for example, essentially all the zhang found in the Guodian Laozi manuscripts are found in the transmitted text, albeit arranged differently, sometimes concatenated or divided, and often with significant textual variation.Footnote 13

Zhang, if viewed as a stable precursors of canons, have become the new face (or heritable facial features) of the urtext, in that they are presumed to be the raw, identifiable, discrete chunks-of-text out of which editors compiled canons, and which therefore implicitly pre-exist canons. In the Laozi, zhang have what the late Rudolf Wagner called “molecular coherence,” which implies that a zhang coheres both structurally and semantically, expressing a complete, bounded idea, thereby constituting the stable, independent building block of the book.Footnote 14 In recent years, this same relationship of zhang to book has been understood as a more pervasive, general phenomenon of book formation in early China.Footnote 15

Integral to the theory, and most relevant to the formation of textual units in the Laozi, is Wagner's theory of interlocking parallel prose, or IPS, a method by which zhang cohere. Since IPS is central to a formal account of the relationship between the Laozi and its parts, it merits a brief, illustrative, digression: in IPS, two or more parallel “strains” are held together by linking or summary sequences that generalize the relationships between parallel elements within each strain. There are thus horizontal structures more familiar from parallel prose in classical Chinese, and vertical structures, which semantically link the two upper and lower portions of each strain.

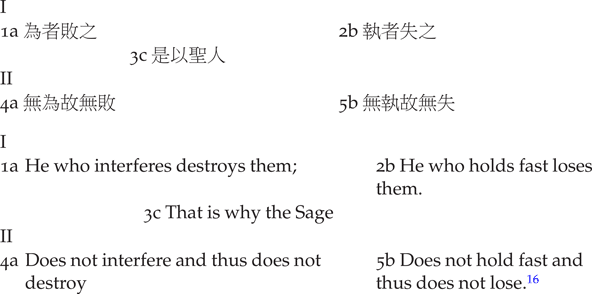

Wagner uses part of Laozi chapter 64 to illustrate the phenomenon:

The two horizontal strains a and b represent phrasal parallelism, whereas vertical rows I and II represent semantically interlocked parallel elements. This most basic example is what Wagner terms “open” IPS, in that its identification can be made on the basis of syntactic characteristics, by following continuity in the use of wei 為 (interfere), bai 敗 (destroy), zhi 執 (hold fast), and shi 失 (lose). C, in this case, is a generalized linker that interlocks the strains, although c passages can also be summative.Footnote 17

IPS is presented primarily as a theory of how zhang of the Laozi were interpreted by Wang Bi 王弼 (226–249 c.e.), although it is presumed also to be an inherent, stylistic feature of chapter composition.Footnote 18 Wagner's related theory of “molecular coherence” stands in starkest contrast to models of Laozi composition such as those of D. C. Lau 劉殿爵,Footnote 19 in which Laozi chapters are viewed as the product of preexisting, unrelated fragments having been assembled by editors.Footnote 20 In Lau's model, the interpretive assumption of coherence has been abandoned even for the zhang of the Laozi. It is worth noting that Wagner's example above of chapter 64, is only part of a zhang as the text is divided in the Wang Bi and Heshang Gong 河上公 recensions, but circulates independently in the Guodian version; sometimes the Guodian manuscripts lend support to Lau's model, sometimes to Wagner's.Footnote 21 Moreover, the two models are by no means the only attempts to grapple with the problem of form and composition in the Laozi,Footnote 22 but it is likely the case, if indeed the Laozi is composed of varying forms that became disposed on varying codices prior to the various versions we know, that to rely on a single theory of interpretation is to assume that some coherent set of rules or principles is applicable to this complex process—that there can be some unified M-theory governing the Laozi's formation. While I do not think such an assumption is tenable or likely to provide results any different from Henderson's assumption of textual coherence, I do hope that the following pages constitute an incremental step towards a more coherent account of some of the processes at work in the Laozi's formation and canonization.

The study proceeds in three parts, working from the interpretation of a single zhang, or chapter, to groups of zhang, to the book/canon (jing 經) as a whole. First, I examine chapter 13 of the Laozi in detail, in a case study of what I call “molecular incoherence.” Rather than revealing a molecular ur-zhang, versions of chapter 13 demonstrate a level of continuity in the processes of composition, editorship, and interpretation that has not yet been fully described. Second, I peer along the seams of Laozi recensions, examining chapter punctuation variants, showing that some of the processes by which chapters collocate—namely by repetition of themes, phrases, or patterns—are indistinguishable from those that help individual chapters cohere. Third, I examine structural features of Laozi recensions, which reveal emphatic efforts to ensure chapter separation in the Beida Laozi. More generally, I show that for editors and scribes who sought to perfect the Laozi, coherence of message was sometimes sacrificed for the continuity of a zhang, or for comprehensiveness in the ordering of the book.

Part One Hypervariability and Molecular Incoherence: A Case Study of Laozi Chapter 13

Zhang of the Laozi that appear to be coherent may not have always been that way. This applies for cases of semantic (or philosophical) coherence, in which a zhang addresses a single comprehensible idea, as well as for cases of structural coherence—in which a zhang coheres as a single textual unit. I treat primarily the former here and the latter in Part Two. In both cases, chapter 13 of the Laozi serves as a crucial subject for case study.

Chapter 13′, by which I mean the textual sequence homologous to chapter 13 in the received Wang Bi and Heshang Gong editions, is in all versions of the text difficult to decipher.Footnote 23 When a bewildered student asked Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200 c.e.), for guidance in the matter, Zhu replied that “[people] have long tried in vain to make sense of this chapter” (從前理會此章不得), and left it at that.Footnote 24 In the thousand or so years since he lived, many others have tried. The Mawangdui A and B 馬王堆甲、乙, Guodian A, B, and C 郭店甲、乙、丙, and Peking University (“Beida” 北大) Laozi manuscripts each present distinct versions of the chapter, and in response to these new manuscript discoveries, at least two full-length articles by prominent scholars in China and Taiwan have been devoted to deciphering 13′.Footnote 25 It may be tempting to hope that an authoritative early manuscript could help untangle the interpretive knot, and indeed new studies of paleography have been marshalled to do so authoritatively.Footnote 26 As I hope to show in Part Three of this article, it is certainly the case that those who produced the Beida recension hoped their reading would be recognized as authoritative, correct, and clear. Here, however, I suggest that looking at all witnesses of 13′ sheds as much light on the continuity of interpretive problems in the Laozi at the level of the zhang than it does on any original, correct, or clear meaning.

A look at how several modern translators have dealt with the opening phrase of 13′ is representative of the diversity of interpretations engendered by the chapter (see Table 1).

Table 1 Laozi Chapter 13, Section One: 寵辱若驚 貴大患若身.

a. Lin Yutang, The Wisdom of Laotse (York: Modern Library, 1948), chap. 13.

b. Michael LaFargue, Tao and Method: A Reasoned Approach to the Tao Te Ching (Albany: State University of New York, 1994), 382. My reading of Michael LaFargue's sentence might be a misreading due to a missing semicolon in his book; if so, perhaps it is all the better an analogy to the problems left in manuscript editions.

c. Chad Hansen, Tao Te Ching: On the Art of Harmony (London: Duncan Baird, 2009), chap. 13.

d. David Hinton, Tao Te Ching (Washington, DC: Counterpoint, 2000), 15.

Note that as varied as these translations are, they do not nearly exhaust the grammatical possibilities for interpreting the line. And although Michael Lafargue's translation does not conform to the conventions of the English sentence, perhaps for that very reason it bears the most resemblance to our extant versions of the text: it is something that we struggle to make sense of, not something clear of itself. This fact is obscured in part by the work of interpreters who seek coherence, including Wang Bi and Heshang Gong, to whose commentaries the most influential transmitted versions of the text are attached.Footnote 27 The Wang Bi and Heshang Gong versions read as follows, as translated according to their commentarial glosses (see Table 2).

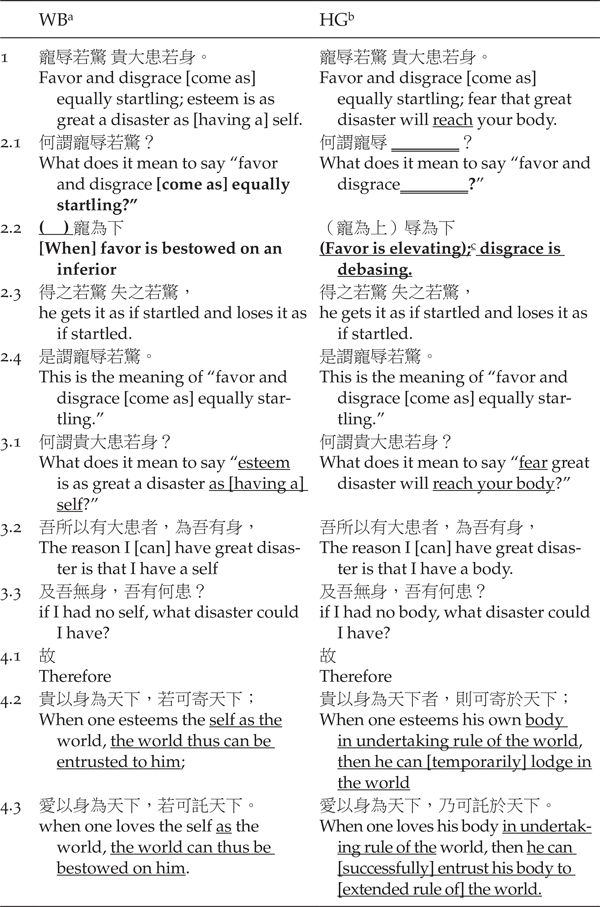

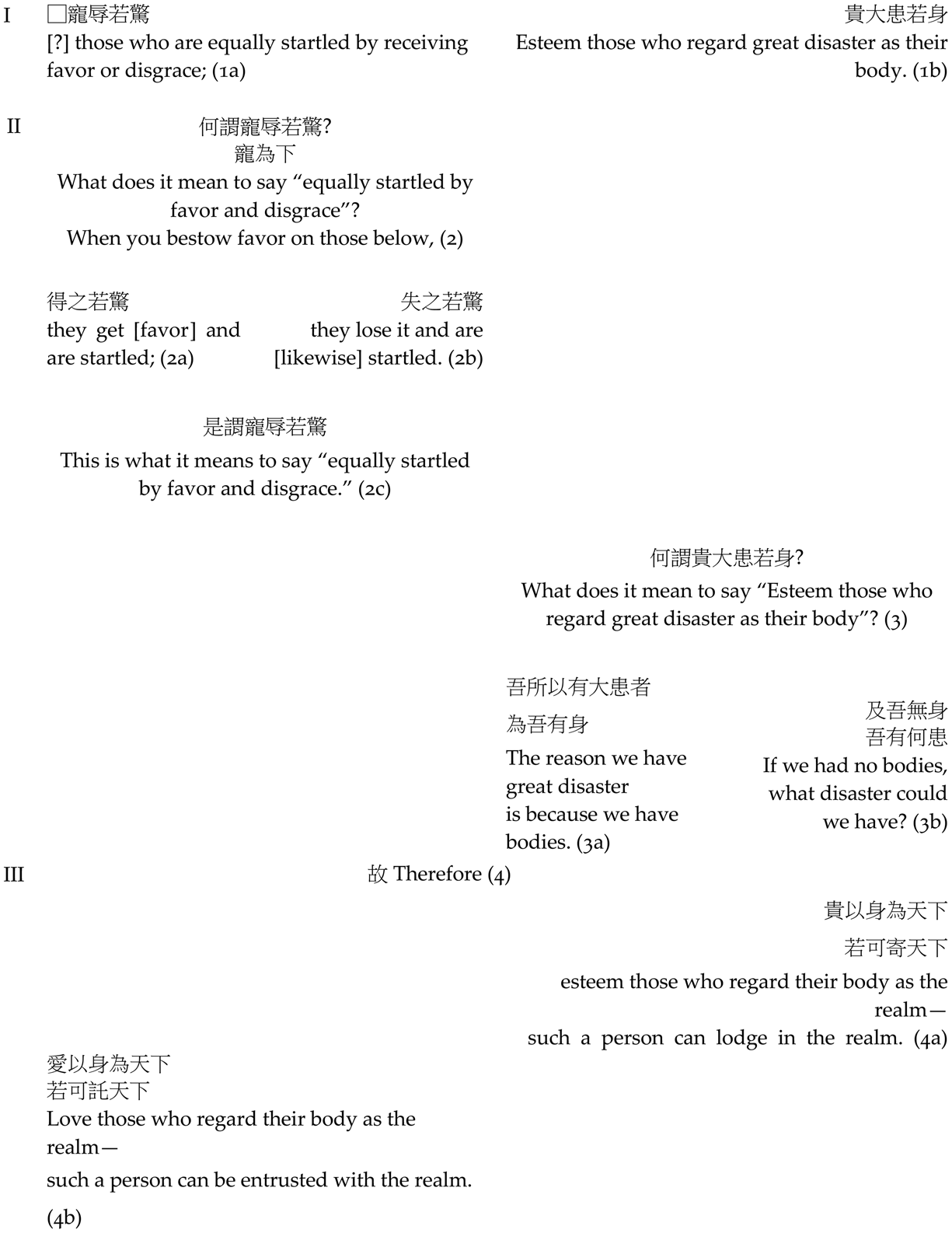

Table 2 Wang Bi (WB) and Heshang Gong (HG) Variants of Chapter 13′.

a. The base text for Wang Bi's Laozi Daodejing zhu 老子道德經注 canon and commentary are the Zhejiang shuju 浙江書局 reprint of the Ming Huating Zhang Zhixiang 明華亭張之象 edition, which is the basis for Lou Yulie 樓宇烈, Laozi Daodejing zhu jiaoshi 老子道德經注校釋 (Beijing: Zhonghua, 2008).

b. Base text: Southern Song Jian'an Yushi kanben 建安虞氏刊本; modern edition in Wang Ka 王卡, Laozi Daodejing Heshanggong zhangju 老子道德經河上公章句 (Beijing: Zhonghua, 1997).

c. Chen Jingyuan's 陳景元 edition of the Heshang Gong text, as well as some Japanese manuscript editions, include the phrase “favor is elevating” (chong wei shang 寵為上). See Wang Ka, Laozi Daodejing Heshanggong zhangju, 50, n. 1.

Although all the sections are essential to understanding the chapter as a whole, the variants of obvious consequence come mostly in section two: note that for the question “What does it mean to say ‘favor and disgrace [come as] equally startling?’” The Heshang Gong version asks merely the meaning of “favor and disgrace.”Footnote 28 In 2.2, Wang Bi's “favor” becomes Heshang Gong's “disgrace.” In the latter reading, as He Zeheng 何澤恆 has pointed out, the suggestion that someone would be startled by “losing disgrace” does not make much sense, and especially in the vast majority of Heshang Gong editions, which lack “favor is elevating,” it is not clear what the “it” of “losing it” 失之 should be.Footnote 29 What is very clear about the Heshang Gong variant and especially that which adds “favor is elevating” (寵為上), is that “favor” and “disgrace” must have the same lexical function; it cannot be sensibly read “favor is disgrace,” “favor the disgraceful” or “deem favor as disgraceful” etc., all of which are otherwise in principle possible.

The Heshang Gong commentary generally gives much more concrete explanations, although they are not always plausible. For example, in reading “fear that great disaster will reach your body” (畏大患若(至)身), it reads gui 貴 (esteem) as wei 畏 (fear), which has no philological basis and is inconsistent with the gloss in part four which reads gui 貴 in its normal sense of “esteem” (albeit portraying “esteem” as bad). It also reads ruo 若 (like; equally) as zhi 至 (arrive, reach), even though ruo 若 is read more conventionally as “equally; like” in the previous line. As is often the case in the Heshang Gong commentary, coherence of message is achieved only by bending conventions of grammar and use.

Both editions and their commentaries set down some influential cart tracks for the medieval interpretive tradition, but they also both leave open crucial ambiguities. Wang's commentary seeks as often to accentuate the multivalence of the Laozi as it does to explicate it. Some of the most important questions are left open by both commentaries: should the ideal person, for example, be startled? Both commentaries agree that the first line is something like “favor and disgrace [come as] equally startling,” but in saying this is the Laozi describing the emotional disposition of the sage or the simpleton? Wang Bi evades this problem by expanding the valence of the first lines:

寵必有辱,榮必有患,驚辱等,榮患同也。為下得寵辱榮患若驚,則不足以亂天下

Where there is favor must be disgrace; where there is honor must be disaster; favor equals disgrace, honor and disaster are the same. When an inferior is startled by getting favor or disgrace, honor or disaster, it is insufficient to bring order/chaos to the world”Footnote 30

Wang Bi's comment presents two opposite possibilities: the term luan 亂 means “chaos” in some circumstances and its opposite, “order” in others.Footnote 31 This is Wang Bi's purposeful use of ambiguity, also seen in one of his central interpretive statements on the Laozi, Laozi zhilue 老子指略, wherein he advocates an aesthetic of chongben ximo 崇本息末 (to revere the root and cease/proliferate the branches), and in which the opposite senses of xi 息, “to cease” and “to proliferate,” are both simultaneously intended.Footnote 32 Thus, according to Wang's anti-reductive “explanation,” an inferior being startled by honor or disgrace will either contribute to political order or chaos. Wang thus leaves open whether the fundamental topic of the chapter—being startled—is normative or counter-normative.Footnote 33

Some later interpreters are quite clear on the matter. The Tang interpreter, Wang Zhen 王真 (690–744), whose commentary follows the Heshang Gong tradition, says that “[to] the sage, losing or gaining [favor] always come as equally startling” (聖人的得失常若驚); Su Che 蘇轍 (1039–1112) said that “the attained ones of old knew to be startled by favor just as they were startled by disgrace” (古之達人, 驚寵如驚辱).Footnote 34 For them, being startled is good. To some, however, being startled is bad. Cheng Xuanying 成玄英 (fl. 636), for example, opines that favor and disgrace ought never disturb the mind of the attained:

喜怖之情皆非真性者也,是以達者譬窮通於寒暑,比榮辱於儻來,生死不撓其神,可(何)貴賤之能驚也

Neither the emotions of happiness or fear are true nature, therefore to the attained, adversity and success are as winter and summer; honor and disgrace are like random events. Life and death do not disturb their spirits—how could they be startled by esteem or disfavor?Footnote 35

Lu Xisheng 陸希聲 (d. 895) takes this even further, interpreting both propositions of section one as counter-normative; not only should one not be startled, one also should not esteem one's self/body any more than one would esteem disaster.Footnote 36

Many have struggled to reconcile the ideal of maintaining composure under pressure, without abandoning compassion for the world, and while medieval commentaries employ Buddhist technologies of reason to navigate this apparent conundrum, the textual problems that underlie them are indeed present not only in the earliest manuscript versions, but in other early transmitted sources (the Zhuangzi 莊子, Wenzi 文子, and Huainanzi 淮南子, further discussed in Part Two). The problem of whether being startled is good or bad is crucial to making sense of the chapter, but ultimately its solution is not easily untangled from the problems of self and body in sections three and four, to which I now turn.

Section three of 13′, which is ostensibly an explanation of the second proposition, section 1b, neither presents nor solves problems of interpretation: having a self/body is tied to disaster, which may be avoided by not having a body. Vague, perhaps, but the grammar is relatively straightforward and the meaning uncontested.

Section four is more difficult, Since ji 寄 (lodge; entrust) and tuo 託 (entrust) are opposed in the parallel structure of 4.2 and 4.3, they are most plausibly interpreted as either synonymous, opposed, or somehow complementary in meaning, but on this the two versions disagree. As customarily used, these meanings should be identical, as in the binome jituo 寄託 (to entrust) already well attested in the Warring States period. The same relationship normally obtains for ai 愛 (love) and gui 貴 (esteem). Yet while Wang Bi interprets these terms as two synonymous or complementary pairs,Footnote 37 the Heshang Gong commentary sees them as contrastive:

言人君貴其身而賤人;欲為天下主者則可寄立,不可以久也。言人君能愛其身,非為己也,乃欲為萬民之父母,以此得為天下主者,乃可以託其身於萬民之上,長無咎也

[Laozi] is talking about a ruler who esteems his own body and deems others as debased—such a ruler, in seeking [to rule] the world may be put in power, [but] cannot last long”; if a ruler is able to love his body, this is not to act selfishly, [but rather] is to be father and mother to all the people. In this way he can become the lord of the world, and his self/body can be entrusted above all the people, for ages without fault.

The decision to read ji opposed to tuo and ai opposed to gui is a way of solving the apparent paradox: how can one strive to not have a body, as is clearly advocated in section two, while simultaneously loving one's body? In the Heshang Gong interpretation, there is one way of having a body that is selfish, and another that is at least in some sense selfless. Wang Zhen expands on this, offering perhaps the clearest justification for the reading of gui and ai as opposites in Laozi 72′: “The sage knows himself but does not show himself; he loves (ai) himself but does not esteem (gui) himself” (聖人自知不自見(現)自愛不自貴).Footnote 38 Although advocacy of ai/ “love” definitely finds support within the text of the Laozi, there are also pronouncements to the contrary, for example, that “those who love deeply pay steeply” (甚愛必大費).Footnote 39 In addition to reversing the conventional meaning of parallel word pairs, the consistency of the Heshang Gong reading also relies on the highly dubious assumption that gui can be read as “fear” 畏 in the first sentence—a reading that even Wang Zhen does not follow.

Liu Xiaogan insightfully identifies a major source of confusion in Laozi 13′: how to reconcile “not having a self/body” 無身 with the apparent advocacy of “esteeming the body,” or “using the self/body to serve the world,” “loving the self/body” 愛身, so as to serve the world, “esteeming the self/body” above the world, or any combination of these that would enable a person to be “entrusted with the rule over the world” or just simply to “lodge in the world.” As Liu more succinctly poses it, is Laozi ultimately advocating a form of egoism, altruism, or neither?Footnote 40 All are possible if we are not bound by one school or another of commentarial exegesis.

Liu's solution to the paradox is ultimately by recourse to the pervasive trope of reversal within the Laozi, in which commonsense notions are overturned.Footnote 41 There is doubtless evidence of this trope throughout the text, from the opening sentence of chapter one, “the way that can be way-ed is not the eternal way” (道可道非常道), to the exhortation to “do the doing that does not and nothing's undoable” (無為而無不為). There are even a number that are of special relevance to the themes dealt with in chapter 13, such as is found in Laozi 7′:

聖人後其身而身先;外其身而身存。非以其無私耶?故能成其私。

The sage puts himself last to come out first; he casts his body aside so as to keep it. Is it not by being unselfish? Thereby he can achieve his selfish ends.Footnote 42

Certainly, this or any other like example can be used to reconcile the problems of 13′. Nonetheless, the main difference between the examples of reversal above and the difficulty of 13′ is that reversal generally announces quite clearly that it is turning convention on its head: opposites are presented within the same phrase, or words are repeated to have obviously distinct meanings; parallelism is often employed to clarify and elaborate on the reversal. And while there is some measure of parallelism in 13′, favor and disgrace are not natural opposites, nor are the terms of section one addressed with any symmetry in the remainder of the chapter, with “love” 愛 seeming to come out of the blue and “great disaster” 大患 going unexplained. This makes and relationship of reversal non-obvious, at best, at least as compared to the trope as exemplified by 7′ and other examples above. This, I think, is part—but not all—of why 13′ has long seemed incoherent.

Moreover, to insist that the trope of reversal as present in 13′ should be just like every other instance in the Laozi is to homogenize the text to itself in search of coherence; the idea that Laozi often means the opposite of what he says, applied indiscriminately, is precisely the sort of commentarial strategy that Henderson identifies, bound to smooth over any incongruences in the text, rather than reveal the seams along which chapters may have been spliced together from previously unattached material.

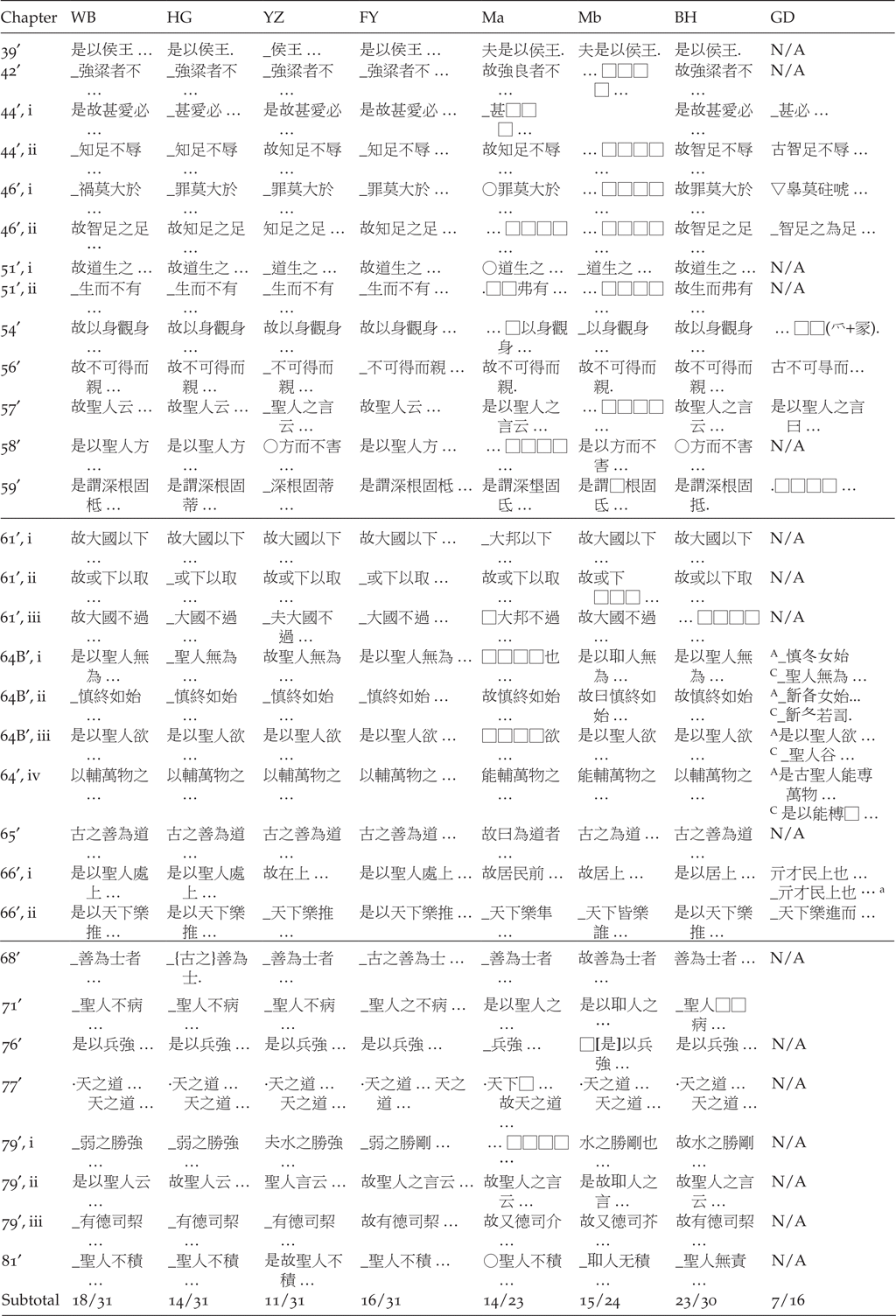

What is Chong-ru in Excavated Manuscripts?

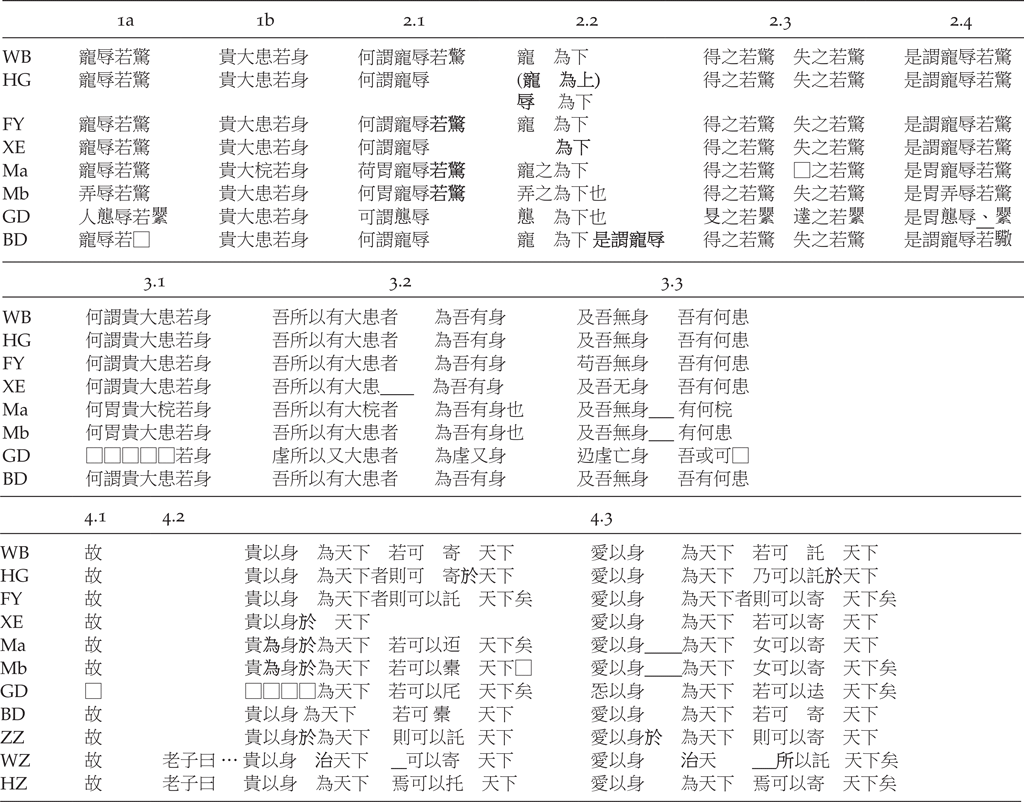

One can merely speculate about the possibility of a Laozi urtext, produced by a historical Laozi, but we are learning ever more about how Laozi manuscripts were read and copied. Rather than coming up with elaborate written explanations to make sense of the text, it seems that when the editors that produced our variant versions of the Laozi sought coherence, they were able to “clarify” the text by rewriting it (within certain limits) so as to conform to their interpretation. The evidence that they did so is that nearly every known manuscript that represents a Han or prior state of the text has a reading for 13′ that differs from all other versions in consequential ways.Footnote 43 The variants are listed in Table 3, and it is clear from the pattern of consequential variants (bolded or underlined) that the underlying interpretive knots—the points which generate textual variance and exegetical confabulations in the Wang Bi and Heshang Gong traditions—are the same points at which we find variance in the manuscripts, primarily in sections two and four. One might speculate that a number of other variants we do not know of also circulated during or prior to the Han, but especially in light of the Guodian and Beida manuscripts, the sources are now already sufficient to conclude that the apparent incoherence of 13′ was problematic for readers of even the oldest extant manuscripts.

Table 3 Laozi 13′ Variants

Abbreviations and notes: WB, Wang Bi; HG, Heshang Gong; FY, Fu Yi 傅奕; XE, Xiang'er; Ma, Mawangdui A; Mb, Mawangdui B, GD, Guodian; BD, Beida; ZZ, Zhuangzi 莊子; WZ Wenzi 文子; HZ, Huainanzi 淮南子. ZZ found in Zhuangzi “Zai You” 在宥 (chap. 11), Wang Xianqian 王先謙, Zhuangzi jijie 莊子集解 (Beijing: Zhonghua, 1995), 91. WZ in Wenzi 文子 “Shangren”上人 in Xin Bing 辛鈃, Tongxuan zhenjing 通玄真經 (Chang shou ju shi Tieqintongjianlou cang ming kanben 常熟瞿氏鐵琴銅劍樓藏明刊本), Sibu congkan 四部叢刊 (Shanghai: Shanghai shudian, 1985), juan 10. Note that the Wenzi places the phrase “Laozi said” 老子曰 prior to the same segment that also contextualizes the 13′ section 3 homolog in the Huainanzi. The contextualizing segment is also found in the Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋. HZ, Huainanzi 淮南子“Daoying” 道應.

To scholars that assumed a linear filiation among manuscripts, wherein older manuscripts represent readings closer to a historical Laozi, it might have seemed likely after the 1973 discoveries of the Mawangdui texts that the Heshang Gong reading in section 2.1, “what does it mean to say chong-ru (favor-disgrace)” (何謂寵辱), was simply the result of a later mistake.Footnote 44 The Mawangdui manuscripts seemed instead to corroborate the Wang Bi text at this locus. Now, however, both the Guodian B and the Beida manuscripts suggest that the Heshang Gong reading circulated in parallel with the longer form of the question, “what does it mean to say chong-ru ruo jing (favor-disgrace-like-startle)” (何謂寵辱若驚) in the Western Han (see Table 3).Footnote 45

There are in essence thus two versions of the question asked in section 2.1,Footnote 46 of which the Beida version poses the short form. Whereas other recensions seem to present and answer one or another of the short or long forms, the Beida text is unique in answering them both. Moreover, because the Beida insertion brackets the definition of chong-ru, it makes the grammatical interpretation more lucid than in any other version, if not coherent at the zhang level:Footnote 47

1

寵辱若驚, 貴大患若身。

Favor-disgrace-like(wise)-startle; Esteem-great-disaster-like(wise)-self.

2.1 2.2

何謂寵辱?寵為下,是謂寵辱

What does it mean to say “favor-disgrace?” Favor is low-down.Footnote 48 This is the meaning of “favor is disgraceful.”

2.3 2.4

得之若驚,失之若驚,是謂寵辱若驚

One gets it as if startled and loses it as if startled. This is the meaning of “favor is disgrace come as equally startling [sic].”

The reading of 2.1–2.2 is one that translators have advocated for other versions of the text,Footnote 49 and it is the first case in which the text of section two is considerably more restricted in meaning. Chong ru here can only really be grammatically interpreted as “favor is disgraceful.” Moreover, such a reading is consequential in that it runs counter to those found both the Wang Bi and Heshang Gong interpretations of this section that read both chong (favor) and ru (disgrace) as parallel elements belonging to the same lexical class,Footnote 50 although it is unclear whether this can also be followed in section 2.4.Footnote 51 Like the emendations of modern interpreters, the contortions of the Heshang Gong commentary, and the vagueness of Wang Bi's commentary, the variant readings encountered here represent another strategy for grappling with the chapter's difficult opening sequence: emend the text.

The matter of how slightly or greatly one might be able to alter or emend is a question of interest. As will be discussed in greater detail in part three, the Beida manuscript shows every sign of a maturing canon, and in the fixed version it seeks to establish, the likely answer is “not very much.” What might one do when faced with two conflicting, earlier versions of the text? The two variant answers to the question posed in section two shi wei chong ru 是謂寵辱 and shi wei chong ru ruo jing 是謂寵辱若驚 appear to have been present in the earlier Guodian and Mawangdui manuscripts, and the Beida text suggests one speculative answer: include them both. It might be argued that this is merely a scribal repetition error, but for a number of reasons I will make clear in Part Three, I think this represents an attempt to account comprehensively and authoritatively with a plurality of variants during a process of collation. Nonetheless, the topic of being startled (ruo jing 若驚), which is precisely the difference between the two variant versions of the answer just examined in section two, merits yet some additional attention below.

Returning to Prior Readings? The Quest for Symmetry in a Laozi Ur-zhang

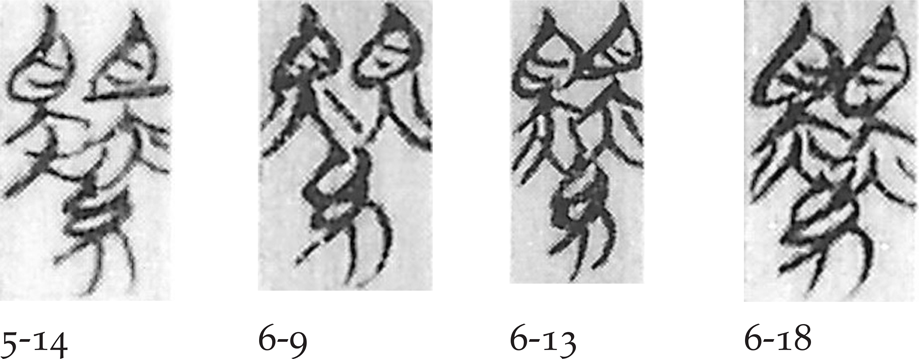

The Beida manuscript has been employed recently by Qiu Xigui to make a radical argument about the original reading of the Laozi. He argues that the character that appears as  in the GD manuscript should not be read as jing 驚 (startle) but as rong 榮, or “honor.”Footnote 52 Qiu argues that the Guodian and Beida versions share common sequences in sections 2.1 and 2.2 because the Beida is an old version that preserved the phrasing of Laozi's words while getting the characters wrong; the editions that add ruo jing 若驚 (as [equally] startling) to 2.1, such as the Mawangdui and Wang Bi texts, got both the characters and the phrasing wrong.Footnote 53

in the GD manuscript should not be read as jing 驚 (startle) but as rong 榮, or “honor.”Footnote 52 Qiu argues that the Guodian and Beida versions share common sequences in sections 2.1 and 2.2 because the Beida is an old version that preserved the phrasing of Laozi's words while getting the characters wrong; the editions that add ruo jing 若驚 (as [equally] startling) to 2.1, such as the Mawangdui and Wang Bi texts, got both the characters and the phrasing wrong.Footnote 53

Qiu's solution seeks a form of semantic symmetry that is otherwise missing from 13′: namely that between rong 榮 (honor) and ru 辱 (disgrace), which is absent between jing 驚 (startle) and ru 辱 (disgrace). The use of rong and ru as opposites is firmly established by the late Warring States; the Xunzi, for example, has an entire chapter on the topic, treating rong-ru as an opposed dyad.Footnote 54 There are obvious advantages to reading the chapter as Qiu's interpretation suggests, which although made explicit only fragmentarily, can be translated roughly as follows:

One can certainly find elsewhere in the Laozi passages in which the Laozi advocates situating oneself below others,Footnote 56 and the paleographic evidence for the above interpretation is quite plausible. The graph  , seen below was originally interpreted as ying 纓 *ʔeŋ (ribbon; twist),Footnote 57 read as a sound loan for jing 驚 *kreŋ (startle). While the upper element of 纓 was initially interpreted as the phonophore ying 賏 *ʔeŋ (strung pearls) by the Guodian editors, Bai Yulan 白於藍 has argued that the upper part of

, seen below was originally interpreted as ying 纓 *ʔeŋ (ribbon; twist),Footnote 57 read as a sound loan for jing 驚 *kreŋ (startle). While the upper element of 纓 was initially interpreted as the phonophore ying 賏 *ʔeŋ (strung pearls) by the Guodian editors, Bai Yulan 白於藍 has argued that the upper part of  should be interpreted as two eyes, or qu 䀠 *[k]ʷ(r)a-s, and that the graph as a whole may thus be transcribed as qu 瞿, an element of ju 懼 (fear) or ying 䁝 (dazzle),Footnote 58 written interchangeably with ying 熒 *[N]-qʷˤeŋ, ying 營 and probably also with rong 榮 *[N-qʷ]reŋ (glory; honor).Footnote 59

should be interpreted as two eyes, or qu 䀠 *[k]ʷ(r)a-s, and that the graph as a whole may thus be transcribed as qu 瞿, an element of ju 懼 (fear) or ying 䁝 (dazzle),Footnote 58 written interchangeably with ying 熒 *[N]-qʷˤeŋ, ying 營 and probably also with rong 榮 *[N-qʷ]reŋ (glory; honor).Footnote 59

Laozi B, rong 榮 or jing 驚Footnote 60

Phonologically, both jing 驚 (startle) and rong 榮 (efflorescence; glory; honor) seem possible. The problem of interpretation now is whether we interpret the two eyes at the top of the graph as the semantophore for the wide-eyed look of astonishment or as eyes bedazzled by “glory.” Both are plausible, although Qiu's solution achieves a new and satisfying coherence, both with the opposed dyad of rong and ru, and with the Laozi's advocacy elsewhere of taking up a low position.

Qiu's argument, although ingenious, has not silenced the debate.Footnote 61 One source of trouble is that the term chong 寵 (favor) as a verb, rendered in Qiu's reading as “cherish” is strictly speaking more like “to [bestow] favor [on].” The use of chong in early texts is primarily transitive with animate beings: you can chong a person, perhaps a pet, but not so much an abstract concept, like “disgrace” or the state of “being below others.” Thus the verb–object interpretation seems somewhat forced unless the object is metonymic for an individual, e.g. “bestow favor on those who [regard] disgrace as honor” (寵辱若榮). This is expressly different from Qiu's reading.Footnote 62

Another problem is that the Guodian Laozi's punctuation does not clearly support the emendation to rong 榮. Within the Guodian Laozi B manuscript, the beginning section of 20′ (henceforth 20A′) is written immediately preceding 13′. Between 20A′ and 13′ there is a punctuation mark, underlined below. Such a mark elsewhere in the manuscript usually denotes a self-sufficient section or chapter of text. If this is indeed a chapter punctuation mark, the opening sentence of 13′, read according to the punctuation, would begin with ren 人 (people):

人之所畏 不可以不畏、

人寵辱若 貴大患若身

貴大患若身

What people fear, cannot but be feared.

people chong ru ruo jing/rong gui da huan ruo shen.

Many interpreters have regarded this as a mistake,Footnote 63 as it does not agree with other versions, but on closer examination it seems that whoever punctuated the manuscript may have read two parallel or related sentences at the juncture of these two chapters: the end of 20′ and beginning of 13′ open with the same word and thus seem to be punctuated as parallel phrases. This would of course make more sense rhetorically and thematically if the manuscript user perceived that both sentences are about fear, which better supports a reading of jing 驚 (startle) for  . This would not necessarily require us to abandon Qiu's reading of “honor 榮” as preferable to “startle 驚,” but it suggests that the person who punctuated the manuscript is more likely to have read the graph as “startle,” mistaken or not.

. This would not necessarily require us to abandon Qiu's reading of “honor 榮” as preferable to “startle 驚,” but it suggests that the person who punctuated the manuscript is more likely to have read the graph as “startle,” mistaken or not.

If we are incorrect in interpreting the punctuation mark as a chapter punctuation, and it is instead a repeat marker, then we may read this section in two ways:

人之所畏不可以不畏畏人寵辱若 貴大患若身

貴大患若身

1) What people fear, cannot but be feared. Fearful people chong ru ruo jing gui da huan ruo shen [are equally startled by favor and disgrace, and regard great disaster as they do their body].

2) What people fear, cannot but fear being threatened.Footnote 64 People chong ru ruo jing gui da huan ruo shen.

In the first of these possibilities, the thematic connection becomes even more clear, such that 20A′ and 13′ perhaps even compose a single chapter in the reading of the punctuator. Should we seek grounds for reading “、” as a repeat mark, it is found on an identical mark on the very same slip, such that the phrase in section 2.4 of GD13 may be read as in every other version of 13′, provided we read ru 辱 (*nok) as a sound-loan for ruo 若 (*nak) as in option two below:Footnote 65

2.4

是為寵辱、

.

.1) This is chong ru. Jing/rong.

是為寵辱辱(若)

2) This is chong ru ruo jing/rong.

It is hard to make sense of the first option; the second is identical to the reading of all other versions, and thus preferable even though it is subject to the same problems of interpretation.Footnote 66 None of the readings discussed in the paragraphs above is a certainty, but the ones that see 13′ and 20′ as thematically connected do not generally support the reading of  as rong 榮 rather than jing 驚. The lack of consistency of punctuation does not help us to make perfect sense of the chapter with the manuscript alone. There may still be some confusion or fluidity at play in marking down the text,Footnote 67 a characteristic that later versions of the text, as we will see, did much to eliminate.

as rong 榮 rather than jing 驚. The lack of consistency of punctuation does not help us to make perfect sense of the chapter with the manuscript alone. There may still be some confusion or fluidity at play in marking down the text,Footnote 67 a characteristic that later versions of the text, as we will see, did much to eliminate.

If we may return, on the other hand, to the possibility that the punctuation mark after “what people fear, cannot but be feared”( 人之所畏 不可以不畏、) indeed indicates chapter punctuation, then the scheme to make each of the first two lines five syllables shares with Qiu's reading a desire for some sort of symmetry, although it seeks that symmetry in syntax, rather than (or in addition to) in the binary opposition of rong and ru (here merely parsed so as to visualize the symmetry):

人寵辱若 貴大患若身

貴大患若身

何謂寵辱 寵為下也

得之若 失之若

失之若

This quest for symmetry in interpretation—the key ingredient in Wagner's IPS—is hardly a new strategy. To provide just a few more modern examples, Chen Guying 陳鼓應 suggests that the order of the second phrase of the chapter should be inverted to rhyme “startle” with “disaster,” to read “esteem the body like great disaster” (貴身若大患), thus achieving an acoustic or phono-rhetorical symmetry,Footnote 68 Gao Heng 高亨 agrees that the “phrase does not make sense” (此句義不可通), and suspects it should read as “great disaster is like the body” (身若大患; four graphs, matching phrase 1.1) achieving parallel structure and metrical symmetry.Footnote 69 D. C. Lau likewise suggests that the word “esteem” has crept in by mistake, and that the phrase should be “great trouble is like one's body” (身若大患; again four graphs). The assumption behind these and many of the efforts to make sense of the chapter is that either Laozi or the Laozi adhered to certain aesthetic conventions of form (e.g. rhyme, rhythm, parallelism, etc.), and that the Laozi was written with conceptual clarity so as to produce a book of coherent philosophical outlook.Footnote 70 But what is particularly interesting is that in at least one regard, both the paleographic suggestions of Qiu Xigui and the speculations of other modern interpreters share more in common with the earliest scribes during textual formation than they do with medieval manuscript users for whom the base text was relatively fixed—namely that their solutions to the problems of incoherence prescribe the types of action that manuscript users actually took: emend the text, in a small but consequential way.

The foregoing has hopefully laid bare the struggle to achieve a perfectly coherent interpretation of the zhang. While one might have thought that early sources could reveal an original, long-lost solution (and perhaps, in the case of Qiu's solution, they do), they seem instead to reveal the continuity of interpretive problems across Laozi versions of varying fixity—problems evident not only in written commentaries, but in the punctuation of the earliest Guodian version, which as far as we know circulated prior to any written commentary. In the Guodian version, the unusual form and uncertainty of punctuation raises the question of where chapter 13′ began, or whether it was joined with 20A′. The matter of whether there was at some time in the Laozi (or in a proto-Laozi) a coherent interpretation at this locus, is for the moment inconclusive. Perhaps the Laozi was never coherent here, or was prone to misunderstanding even in the Warring States manuscript version, such that the statement “[people] have long tried in vain to make sense of this zhang (chapter)” has been true even longer than Zhu Xi imagined.Footnote 71 The next section, as part of a larger examination of chapter separation in Laozi editions and manuscripts, will explore the premise of Zhu Xi's reply (and presumably of the question he was asked), namely, that 13′ is indeed an integral zhang rather than a composite of superficially related parts.

Part TwoLaozi at the Seams: Repetition as a Cue for Compilation and for the Continuity of Zhang

The question of how 13′ and 20A′ were connected in the Guodian version raises the topic of another sort of variance evident across manuscripts—that of how zhang, or their constituent subunits, might have come together to make versions of the Laozi. Where does one chapter end and another begin? Many others have already noted that a chapter as punctuated in any given edition often contains two or more textual sequences that appear to have very little in common.Footnote 72 In addition to ancient recensions, like the seventy-two-chapter Yan Zun 嚴遵 Laozi that is transmitted in part, other ancient and modern editions have arranged, punctuated, and divided the Laozi differently, and these variants of chapter punctuation often reveal disagreement about what properly designates a unit.Footnote 73 For reference in the following sections, Chart 1 provides a map and overview of punctuation variance across the major editions, and makes clear where ancient recensions have drawn lines that separate units of text. The discussion below seeks to demonstrate that zhang are composite, that this compositeness matters for interpretation, and that the repetition of themes and patterns plays a role both in the compilation and in the composition of chapters. A close look at some of the seams along which the Laozi was stitched and glued will show that editorial processes operating between known units share more in common than is generally recognized with compositional processes operating within each unit; coherence and continuity in cell-like chapters and their multinucleate syncytia may not be merely a feature of some prior, urtextual act of de novo composition, but of editorial processes—including the strategies of emendation noted above—that operate on the units themselves. The apparent incoherence of chapter 13′ may result from such processes.

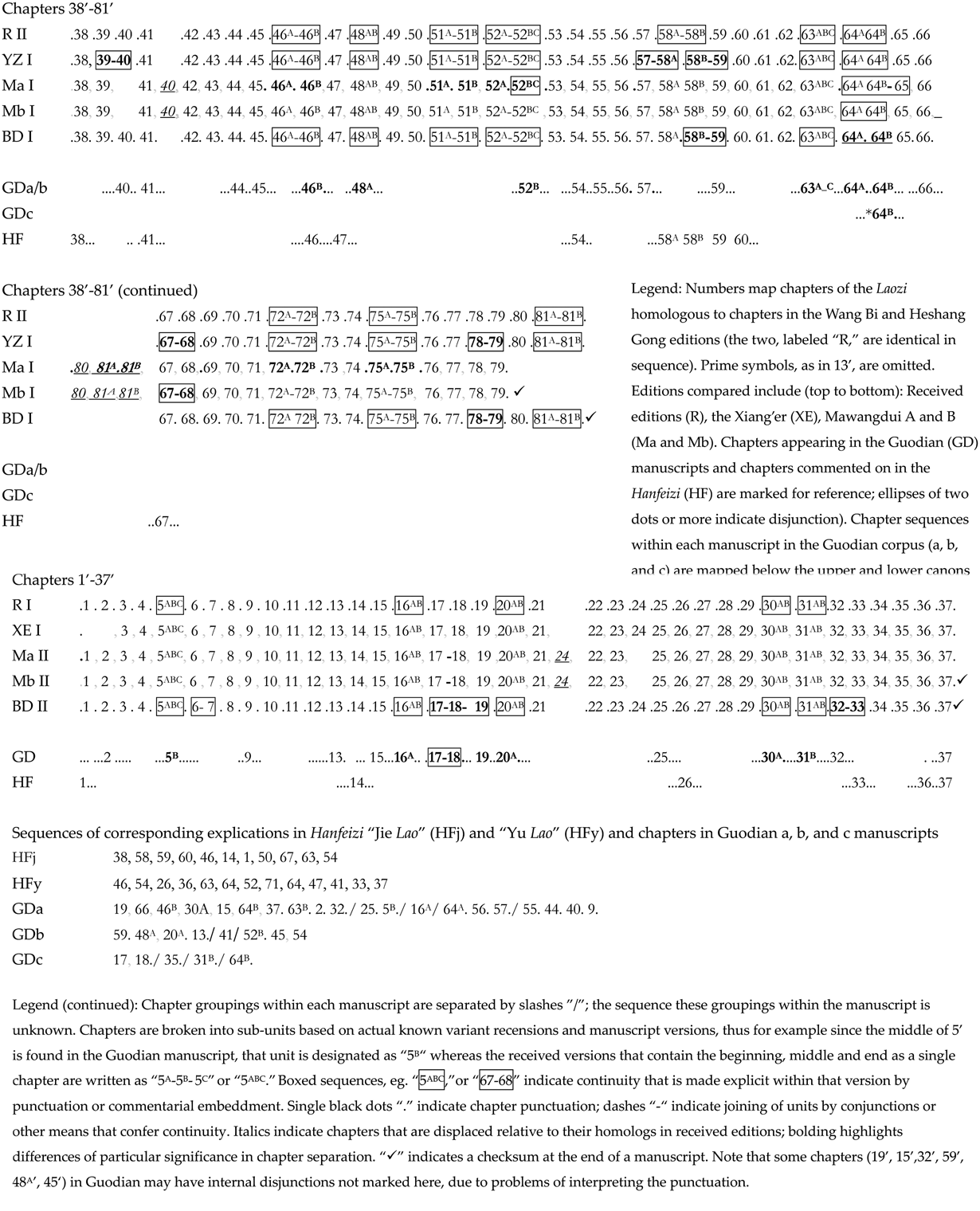

Chart 1 Schematic diagram of Laozi chapter organization

Repetition of Passages is a Sign of Compositeness

One indicator that a zhang is a composite of sub-zhang particles is when a given fragment or passage shows up in more than one place. Such evidence is already visible within received editions. D. C. Lau has pointed out more examples of these chapters than I will do here,Footnote 74 but I begin with one example that he does not discuss. The last sentence of chapter R10 is essentially an abbreviated version of the latter half of R51 (underlined text translates parts present in both versions), presented here as found in the Wang Bi recension:Footnote 75

WB51B

…故 道生之 德畜之 長之育之 亭之毒之 養之覆之

生而不有 為而不恃 長而不宰 是謂玄德

WB10B …

… 生之 畜之 生而不有 為而不恃 長而不宰 是謂玄德

…Therefore, The Way bears them, Virtue raises them; leads them, nurses them, tends them trains them, cares for them, covers them. To bear without being, do without depending, lead without ministering—this is called Profound Virtue.

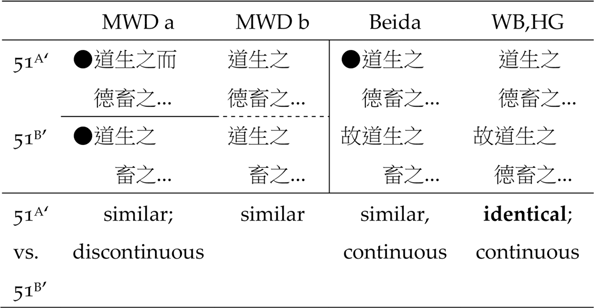

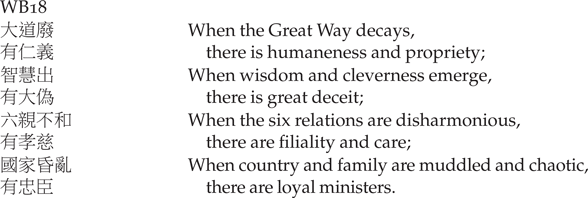

One might argue that either version of this shared textual sequence is merely a formula that gets tacked on to the end of an otherwise complete chapter,Footnote 76 but analyzed in terms of Wagner's IPS, Wang Bi 51B has all the interlocking parts of a complete zhang, and is at least by that measure self-sufficient. Moreover, if we look to its homolog in the Mawangdui manuscripts, we find that 51A′ and 51B′ are separated by punctuation marks in the A manuscript, and 51B′ omits the opening “therefore” 故 in both A and B manuscripts, so we know that in these versions, at least, the text was not read continuously at this juncture.Footnote 77

Chapter Fusion and Repetition of Phrases as a Cue for Adjacency

Chapter 51′, as punctuated in the Mawangdui recension into two separate chapters, also illustrates another important feature that may help bring textual sequences together during text formation: repetition of words or patterns. Both parts of the chapter repeat variants of the phrase “The Way bears them, Virtue raises them” (道生之 德畜之):

●道生之而德畜之 物刑之而器成之 是以萬物奠道貴德 道之尊也 德之貴也 夫莫之爵常自然

●道生之 畜之 長之遂之 亭之毒之 養之覆□ □□弗有 為而弗寺 長而弗宰 此之謂玄德

• The Way bears them and Virtue raises them, matter gives them form, implements complete them. This is why the myriad things revere The Way and esteem Virtue. That The Way is revered and Virtue esteemed—so it is that none give them titles and they are eternally self-such.

• The Way bears them raises them; leads them, follows them, tends them trains them, cares for them, covers [them]... ...[To be] without being, do without depending, lead without ministering—this is what is called Profound Virtue.Footnote 78

Either of these could be a zhang on its own, or the two could function like two verses in a single poem. But the process of making them into a single chapter also coincides with a subtle change in the reading: the difference found in the Mawangdui recension between the two phrases, “The Way bears them and Virtue raises them” in 51A′ versus “The Way bears them, raises them” in 51B′, is eventually erased in all received editions, in which 51A‘ and 51B′ are read as a single chapter, R51, and the two lines underlined above read identically. As seen in Table 4, the Beida manuscript may illustrate an intermediate state in which the chapter separation has been erased but the two lines not yet fully homogenized (black dots represent chapter punctuation).

Table 4 Punctuation Variants of 51′

This offers us a glimpse of the process whereby textual units placed side-by-side on the basis of similarity could be made more coherent by editing the two similar phrases so as to make a perfectly identical refrain.Footnote 79 In this case, two single textual units transform to undergo a cell fusion of sorts, producing a cohesive syncytium. The same phenomenon is evident in other chapters, such as 75′.Footnote 80

Compositeness Matters for Interpretation

One might argue, perhaps, in the case of chapter 51′ that because the two concatenated textual units are sufficiently abstruse or open-ended statements, they can be combined into a single chapter without much influence on their interpretation. In other cases, however, recombinant textual sequences can have more obvious consequences for interpretation. This can be seen more clearly with chapter 10′, which contextualizes the same variant textual unit differently (underlined below):

載營魄抱一,能無離乎?專氣致柔,能嬰兒乎?滌除玄覽,能無疵乎?愛民治國,能無知乎?天門開闔,能為雌乎?明白四達,能無知乎?生之、畜之,生而不有,為而不恃,長而不宰,是謂玄德。

When bearing up the hun and po while embracing The One—can you be without separation?

While concentrating qi and attaining suppleness—can you be like a baby?

When cleaning and polishing your profound mirror—can you be without defect?

While loving the people and ordering the country—can you be without wisdom?

As the Heavenly Gate opens and shuts, can you be the female?

When your bright clarity penetrates the four directions, can you be without knowledge?

[WB10A]

To bear without possessing, do without depending, lead without ministering—this is called Profound Virtue.

[WB10B]

Should we have misunderstood what it means to at once hang on to one's heaven-bound hun and earthbound po soul, attain the suppleness of a babe, be without knowledge or wisdom, etc., the final textual unit offers a set of processes (or ways of being) and a name, “Profound Virtue”—to attach to the ideal presented in 10A′. If we adopt a reading practice that presumes a chapter expresses a coherent idea, much as when contemplating the meaning of chapter 13′ required some contemplation of each of its parts, we are also inclined to consider the whole of chapter 10′ together as bearing out a single truth. Chapter concatenation thus matters for what the chapter means. And some versions take measures to ensure that a chapter coheres at seams where it might easily fall apart; in order to make the continuity of the two parts of 10′ unmistakable, the Beida version of the text inserts gu 故 between 10A′ and 10B′. Even more emphatic about the structural coherence of the passage, the Beida version of the chapter 51′ places a gu 故 not only between 51A′ and 51B′, but also another within 51B′ for good measure.

Repetition of Patterns as a Basis for Chapter Fusion

In the case of 51′ identical phrases seem to be the glue that holds units together, as either a structurally coherent (continuous) chapter or as an editorially coherent sequence within the compilation. Nonetheless, one need not look far to find evidence that even imperfect or partial repetition may suffice to bring units into proximity; the very next chapter, 52′, which is a single chapter in the received and Beida versions, appears to be two unrelated units held together by the pattern “X shen bu Y” (X身不Y), “your life may X and yet you will not Y,” bolded below:

52′

天下有始 以為天下母 既得其母 以知其子 既知其子 復守其母 沒身不殆[52A′]

(●Ma) (■ Gb)[52B′]

見小曰明 守柔曰強 用其光 復歸其明 無遺身殃 是為習常[52C′]

[The Realm] Below Heaven has its beginning, it is the mother of Below Heaven.

Once we know its mother, so may we know its child;

Once we know its child, so may we hold to the mother.

And until your life goes under, you will never face danger. [52A′]

(●Ma)

Block your passages, close your gates

And until your life ends you will never be weary.

Open your passages, conduct your affairs

And until your life ends you will get no relief.

(▓ Gb)[52B′]

To see the small is called clarity;

To hold to the supple is called strength.

By brightness, return again to clarity.

No danger of losing your life.

This is to practice constancy[52C′]

Chapter 52′ can be divided into three sections on the basis of prosody. Aside from the presence of the word shen 身 (body; life), there is little clear theme that brings these units together. For 52A′ and 52B′, the common use of “X shen bu Y” seems to be the main link between the passages. The same phrase “and until your life goes under, you will never face danger” 沒身不殆 appears in the unrelated chapter 16B′, so even in received versions the pattern is not endemic to 52′. Aside from the thematic, metric, and prosodic bases for separating the units, the middle section 52B′ (boxed text) is punctuated at the beginning in the Mawangdui A manuscript and at the end in the Guodian B manuscript,Footnote 81 so at least some early readers of the text regarded these parts as self-sufficient. If in the preceding chapter, 51′, one might suspect that the punctuation variance is merely an idiosyncrasy owing to one errant scribe, here it is much more difficult to argue that, since two independently excavated manuscripts concur on the discontinuity of 52′.

Traces of Fusion are Sometimes Erased in Transmitted Versions

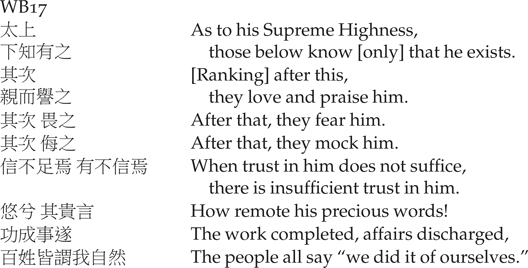

Other examples further illustrate the mechanics of the fission and fusion of textual units. Punctuation variants of 17′–18′, for example, illustrate how repetition that has been erased in received editions may have functioned in prior versions to order textual units. The Guodian C manuscript punctuates 17′ and 18′ as a single chapter; the Beida recension additionally combines 19′ with them to produce a single, larger chapter. Between 17′ and 18′ in the received editions there is no obvious thematic connection. As with the parts of 10′ or 13′, one needs to interpret both together and consider how one might make them cohere before such possibilities arise:

In the transmitted editions, there are few clues to why these should be put together, and they are regarded as separate. Chapter 17′ is apparently about the ideal ruler, in contrast to the non-ideal ones. Perhaps being a good ruler has something to do with trust as well?Footnote 82 The text here is unclear in received versions. Chapter 18′ seems to be about the rejection of virtues most explicitly championed in Confucian literature; that is, when the world has The Way, such artifice is unnecessary. If forced to put the chapters together, it seems necessary to me to seek coherence in some higher-order virtue, such as wuwei 無為 non-action or non-artifice. 17′ and 18′ are a single chapter in all of the manuscript versions, in each case linked by gu 故. Although there is no repetition that would clue us in to continuity in the received versions, there are two phrases that read differently in all manuscript versions of 17′ and 18′ respectively (shared also with the Fu Yi edition):

[WB, HG] 17′

信不足焉 有不信焉

… When trust in him does not suffice, there is insufficient trust in him.Footnote 83

[BD, GD, FY, Ma, Mb] 17’

信不足 焉有不信

… When his trust is insufficient, thereupon is there mistrust.

[WB, HG] 18′

大道廢 有仁義

When the Great Way decays, there is humaneness and propriety

[BD, GD, FY, Ma, Mb] 18′

故 大道廢安(焉)有仁義

… Therefore when the Great Way decays, thereupon is there humaneness and propriety.

The important part shared by all the versions that read 17′ and 18′ continuously are the repetition of the words yan you XX (焉有 XX).Footnote 84 Only manuscript versions of 18′ (and the Fu Yi) continue on to repeat the same pattern “thereupon there is XX” (焉有 XX) for each of the rejected virtues. Thus the presence of repetition in the units across different editions concurs with 17′ and 18′ being regarded as a fused syncytium; absence of repetition corresponds to punctuation as separate units. In most received traditions, which read 17′ and 18′ as separate, the clue to how the two passages came into proximity has been erased, and a case of fission is evident in the received versions.

Repetition May Help Index Sequences of Textual Units

In addition to precise and partial repetitions of phrase seen in examples above, repetition of theme may also play a role in compilation sequence. In most editions, chapter 19′ appears to follow 17′–18′ thematically, in that it continues the same critique of ren 仁 (humaneness), yi 義 (propriety), and zhi 知/智 (wisdom) in 18′. This is not the case in the Guodian version; both it and received versions are translated below for comparison:

19′ (All R and manuscripts other than GD are nearly identical for this chapter)

絕聖棄智,民利百倍;

絕仁棄義,民復孝慈;

絕巧棄利,盜賊無有。

此三者以為文不足,故令有所屬:見素抱樸,少私寡欲

Reject sagacity, discard wisdom, and the people will benefit a hundredfold;

Reject humaneness, discard propriety, and the people will revert to filiality and care;

Reject cleverness, discard benefit, and thieving bandits will be no more.

These three do not suffice as a pattern, so let them have what is [here] attached:

Demonstrate the plain and embrace the unhewn; be short of selfishness, few of desires.

GD19

(絕)智弃(棄)𰆴(辨),民利百伓(倍);

(絕)智弃(棄)𰆴(辨),民利百伓(倍);

(絕)攷(巧)弃(棄)利,覜(盜)惻(賊)亡又;

(絕)攷(巧)弃(棄)利,覜(盜)惻(賊)亡又;

(絕)𢡺(偽)弃(棄)

(絕)𢡺(偽)弃(棄) (詐),民复季(稚)子。

(詐),民复季(稚)子。

三言以為 (事)不足,或(又)命之或(有)𰲛(所)豆(樹):

(事)不足,或(又)命之或(有)𰲛(所)豆(樹):

視(現)索(素)保僕(樸)少厶(私)寡欲。

Reject wisdom, discard discrimination, and the min-people will benefit a hundredfold;

Reject cleverness, discard benefit, and thieving bandits will be no more.

Reject artifice, discard deceit, and the people will return to being like children.

Three sayings are insufficient for the task (at hand), so again we define them to set things straight:Footnote 85

Demonstrate the plain and guard the unhewn; be short of selfishness, few of desires.

Again, as with examples above, wherever 18′ and 19′ are read as either continuous or adjacent, the two units cohere in ways that the Guodian homologs GD18 and GD19 do not. In all received versions, as well as the Mawangdui texts that read 18′–19′ continuously and the Beida, which reads 17′–18′–19′ continuously, the two units 18′ and 19′ cohere in rejecting ren 仁 (humaneness), yi 義 (propriety) and zhi 智/知 (wisdom). Conversely, in the Guodian manuscripts, GD18 (found in the C manuscript) and GD19 (found in the A manuscript) are discontinuous—and, correspondingly, the two reject completely different sets of virtue-elements.Footnote 86 Much has been said about the particular tolerance in GD19 of the same Confucian virtues rejected so roundly in other Laozi recensions;Footnote 87 here I emphasize that the divergent content of GD19 correlates tightly with its thematic and codicological disjunction from 18′.

A number of other links of theme or repetition apply to other chapters in manuscript and received editions, and although the identification of thematic connections are in some case more contestable matters of interpretation, it should be clear from the previous examples that the content of a chapter may be subtly altered, making themes or repetition more or less apparent, and blurring what appear as clear boundaries between zhang in transmitted recensions.Footnote 88

A larger question that remains in reflecting on the preceding examples is whether repetition causes or merely correlates with the co-compilation (and potential fusion) of textual units. The beginning of 20′ as disposed differently across distinct Laozi versions indicates that repetition is likely to be a causative factor, rather than merely correlative, in determining how textual units become disposed during compilation. We have just witnessed the phrase opening 19′, “reject [this] discard [that]” (絕 X 棄Y), which in any variant version would suffice to link it to the beginning of 20′:

WB20A′

絕學無憂,

唯之與阿,相去幾何?

善之與惡,相去若何?

人之所畏,不可不畏。

Reject learning and there will be no worries.

To say “yes” to it or “no”—how far between them?

To regard it as good or bad—how different are they?

That which people fear cannot but fear [people?]

In 19′, because the theme “reject [this] and discard [that]” (絕 X 棄 Y) and the first four graphs of chapter 20A′, “reject learning and there will be no worries” (絕學無憂) constitute similar patterns, the opening of 20A′ was previously thought to belong somewhere within chapter 19′, with “learning” functioning presumably as a summative category encompassing the several other virtue-elements of sagacity, wisdom, cleverness, etc., rejected in 19′.Footnote 89 This has not been corroborated by any of the manuscripts. It is not obviously coherent with the rest of 20A′, and 20B′ (which I omit for the sake of brevity) has a distinct prosody and no clear connection to either the call to “reject learning” or the rest of 20A′. A related suspicion, that 20A′ and 20B′ do not cohere, is corroborated by the Guodian manuscript, which contains only 20A′. Again, then, as with the examples enumerated above, the disposition of 19′ and 20A′ on the same codex correlates with opening lines that appear similar or complementary. The same principle, however, seems to apply to the relationship between GD48A and GD20A, which are written in that order on the Guodian B manuscript: the former begins with “[in] pursuit of learning you add daily” (為學日益); the latter with “reject learning and there will be no worries” (絕學無憂). The fact that repetition of similar themes (or themes also complementary, in the Guodian case) functions according to a similar principle within these two distinct sequences indicates that repetition may in some cases play a causative role in the co-compilation or indexing of textual units. And such superficial similarities or partial repetition may bring together units that had no prior, fundamental philosophical connection.

We have seen so far that in addition to bringing units of text together in adjacent positions, the repetition of similar words, patterns, and phrases can be interpreted as continuity between textual units. Moreover, sometimes, where in two adjacent units, repetition of non-identical but similar phrases corresponds with division, identical versions of the phrases seem to confer continuity. The reason 52A′ is collated with 52B′ is probably because of the co-occurrence of the X-shen-bu-Y that is found repeated within 52B′ as well as between the two. The same is true of jue-X-Y-Z, found within 19′ as well as between 19′ and 20A′. In essence, the same principle of repetition that can confer internal coherence on a chapter or syncytium may also present an organizing or mnemonic principle for groups of chapters, and a means by which editors used the rhetorical similarity of units to affect greater coherence on compilations.

Repetition Can Confer Structural Continuity on a Chapter

In the foregoing, it has perhaps been unnecessary to show that repetition is an internal feature of structurally coherent textual units. Repetition indicates a continuity of topic, and it is an assumed feature of closed IPS. Sometimes, such a repetition is integral to a larger parallel structure within a chapter. An example of this is found in 66′ for which all versions but Guodian hold the chapter together with gu 故 or shiyi 是以 (for this reason) in the middle.Footnote 90 The Guodian version instead repeats “he is above the min (people)” 亓在民上也 to maintain clear continuity at this junction. The passage exhibits impressive symmetry.

GD66

江海所以為百浴王 That the rivers and seas are king of the hundred valleys

以亓能為百浴下 is because they can be below the hundred valleys.

是以 能為百浴王 Thus they can be king of the hundred valleys.

聖人 As to the sage,

之才民前也 his being in front of the min 以身後之 comes by standing behind them;

亓才民上也 his being above the min 以言下之 comes by speaking as if below them.

亓才民上也 His being above the min 民弗𥐽也 does not burden them;

亓才民前也 his being in front of the min 民弗害也 does not harm them.

天下樂推而弗詀 [That] the realm happily promotes him and does not complain

以亓不靜也 is because he does not contend.

故天下莫能與之靜 Thus, none in the realm contend with him.

In this case, an example of what Joachim Gentz calls “bidirectional parallelism,” is the exception that proves the general rule that repetition and parallel structure confer coherence and continuity on a textual sequence:Footnote 91 It shows on the one hand how repetition can be a fundamental signal of continuity, and yet, on the other hand, it is exceptional in that its repetition is integral to a thoroughgoing bidirectional structure. The primary axis around which the chapter is organized is the repeated phrase, “his being above the people” (亓才民上也) although this repetition is replaced by gu 故 in all other versions of the chapter. We do not know whether the chapter as it is structured in the Guodian manuscript is the product of parallelism as a compositional principle, or a set of editorial iterations that was applied to some prior set of seed materials brought into proximity and subsequently edited. A version of the last line of 66′ is found in the middle of chapter 22′, so one or both of these chapters must be constructed from previously circulating formulae or sayings. Nonetheless, having achieved such a high degree of conceptual structure, it is hard to imagine 66′ falling apart or being mistakenly subdivided. Indeed, it shows that repetition, as part of a larger symmetrical structure, can anchor the continuity of a chapter even more unambiguously than conjunctions such as gu.

Chapters May Accrete by Partial Repetition

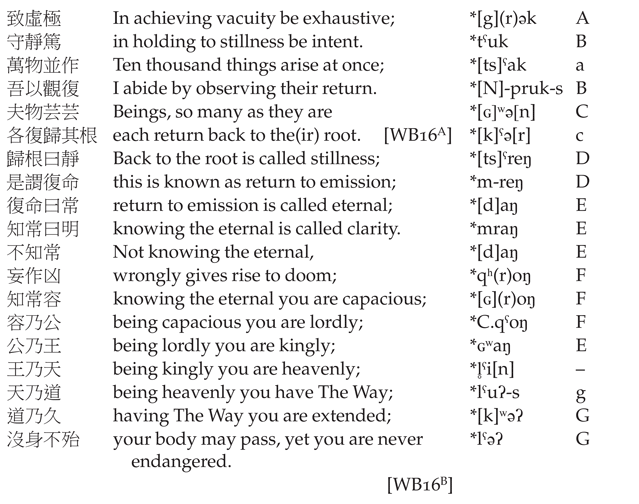

Sometimes, repetition may function in what appears to be either auto-commentarial accretion, or an otherwise indistinguishable process that splices units together. The final chapter punctuation variant discussed here, that within 16′, appears to be what D. C. Lau in 1963 called “a pre-existing passage … followed by a passage of exposition.”Footnote 92 In the received version of the text, 16′ reads as follows (here as in Wang Bi):

Only the first part of the passage above, a homolog of 16A, appears in the Guodian manuscripts, where its end is clearly punctuated.Footnote 93 The two parts are glued together in all other editions by repetition of “back to the root” (歸根) or “back to its root” (歸其根). Chapter 16B appears to be a comment on 16A, explaining, somewhat like the dialogic portions of 13′, the vocabulary that came before. But the disjunction in the Guodian version shows clearly that the integrity of the chapter 16AB as known from received versions was not guaranteed in a Warring States context.Footnote 94 Moreover, while 16A bears some of the structural features of IPS, the latter part, 16B, lacks the rhetoric of binary opposition in found in 16A, and operates instead like a string of rhyming sorites, capped with the formulaic “X身不Y” pattern seen above in other chapters. The sorites each present an incrementally plausible connection to the next, but with each iteration the theme recedes further from that of 16A′, to which the conclusion in 16B′ bears no obvious connection. The Guodian manuscript suggests either that 16B′ postdated the composition of 16A′, and was written as inline commentary, or that 16B′ was simply a separate element that was later concatenated with 16A′ on the basis of its repeated element.Footnote 95

Is Chapter 13′ Composite?

Given the varied models above for how textual units may be brought together at the seams, it is worthwhile to re-examine chapter 13′ once more, from another perspective. The opening line reads as follows:

We have seen above that ru 辱 and ruo 若 were homophones, with the former used as a sound loan for the latter in the Guodian manuscript. We might also, given the plausible argument that rong 榮 and jing 驚 are easily confused, that the same is true of those two words. The two lines, as reconstructed, contain substantial alliteration and consonance—a tongue-twister, perhaps; a brain-teaser, undoubtedly.

What is more, the overall structure of the chapter follows a layered, dialogical question and answer format that would be quite normal in early dialogues, but is rare in the Laozi,Footnote 96 such that one may wonder whether the layers are commentary that has sedimented on some prior bit of gnomic wisdom, as is plausible in continuous versions of 16′. The term, he wei 何謂 (what does it mean to say …) is found nowhere else in the Laozi, but it is found repeated in 13′—a fact that may directly respond to the apparent incoherence of the opening line. And despite the promise of elucidation, the internal responses do not satisfy. To close, there is an apparently normative statement (section four) about who or what should be “esteemed” (gui 貴) and “loved” (ai 愛), but, as with thematic drift in 16′, the mention of “love” downstream in 13′ appears to be a non-sequitur. Are we looking at a chapter that was all written at once, or at a composite that brings fragments together?

In his translation of 1963, before any of the manuscripts came to light, D. C. Lau assumed that 13′ is composite, and split it into three parts: 1) Lau's passage 30 (my section one); 2) a related passage 30a (my question and answer sections, two and three); and 3) an unrelated passage 31 (my section four).Footnote 97 The last of these Lau singles out as a Yangist statement that “does not fit well into the Lao Tzu, where survival is assumed, without question, to be the supreme goal in life.”Footnote 98 I will not take up the topic of whether the Laozi is at this locus philosophically incoherent. It is certainly possible that sections two and three are inline commentary that sought to decipher the opening line, but eventually became fossilized in the chapter itself. Notwithstanding the problems of linkage between 13′ and 20′, and the fact that there is a lacuna in GD13 obscuring the gu 故 that links the 13′ together in all other versions, it is probably the case that even in the Guodian version, 13′, was read continuously, as in all other versions;Footnote 99 but this does not mean that continuity in 13′ was produced by a single act of composition.

Although generally critical of Lau's assumption that the Laozi is composed of fragments rather than zhang, Wagner sees more order than chaos; yet he can find IPS evident only in the first part of this chapter: he labels section four as a sequence of c elements—summary comments on the first parallel pair.Footnote 100 Strictly speaking, he is correct that 13′ resists his analysis, but there is still a large degree of parallelism within sections two, three, and four that goes otherwise unaccounted for. I have tried to arrange the structure in Figure 1, such that parallelism, if not precisely Wagnerian IPS, is visible throughout. Sections 2 and 3 (block II), in this arrangement, appear to be nested parallel comments on phrases 1a and 1b (block I) respectively, and considering that Wagner presents IPS as a theory of interpretation, reproduced also as a compositional style in Wang Bi's commentarial Laozi weizhi lueli 老子微指略列, and numerous pre-imperial texts,Footnote 101 one should not be surprised that those who interpreted and commented on a proto-Laozi would mimic its style in inline commentary that elaborated on a pre-existing maxim.

Figure 1 Nested parallel structure in 13′

Although it is merely plausible speculation that the development of both 16′ and 13′ follow accretive processes or attached inline commentary to a previously existing passage correlated by its discussion of gui 貴 (esteem) and shen 身 (the body), it is a matter of fact that section four of 13′ circulates independently as a saying or quotation in other known early texts, including the Wenzi, Zhuangzi, and Huainanzi (see again Table 3), whereas the other sections do not. Variants of section four differ in the same consequential ways interpretations of the received texts differ.Footnote 102 For our purposes, however, the variants show that the meaning of the text could be modified in subtle ways, and that section four could function as a self-sufficient passage, as it functions beyond the Laozi.

As we have seen above, based on an examination of the points at which chapters are divided differently across versions, the forces that deposit independent textual units adjacent to one another include the repetition of words, patterns, or themes. This attains a high degree of order in IPS or bidirectional parallelism, but such passages are not necessarily representative of the level of structure found throughout the Laozi. The features, other than conjunctions and discourse markers (gu 故, shiyi 是以, shi wei 是謂, etc.) that signal continuity within textual units are, likewise, the repetition of words, patterns, or themes. Since the same set of principles is associated with both the proximity of textual units on a codex and continuity within textual units, and, moreover, because the degree and closeness of repetition appears quite malleable even after units are assembled into sequences, we need to reconsider the extent to which compositional and editorial processes can ever be distinguished in producing the Laozi, even at the level of its smallest (ostensibly stable) chapter units.

Part ThreePerfecting the Book: Editorial Intentionality and the Conjoining of Laozi Chapters

The question of exactly how chapters such as 13′ and 20A′ came to be composed and compiled as they did in the Guodian manuscripts versus all later recensions is still a matter of some speculation, particularly with regard to how a historical author may have been involved. Cheng Xuanying 成玄英 (fl. 631–50), a Tang interpreter who lived during a time in which manuscript production was still the primary means by which ideas were disseminated, looked back merely hundreds rather than thousands of years on the origin of the Laozi as a book, and on the development of its early interpretive schools. Cheng divided his synopsis of the Laozi into five parts: 1) Daode 道德者, or “The Way and Virtue”; 2) “explaining the term jing (warp-text; canon; scripture)” 釋經者; 3) “the essence of [discrete] schools” 宗體者; 4) “the number of graphs [in the text]” 文數者; and 5) “[the number of] zhang (chapters) and juan (scrolls)” 章卷者.Footnote 103 Certainly, before Yan Zun (as we will see in more detail below) the term Daode was perceived as the core philosophical dyad of the Laozi. In regard to the rubric for Cheng's synopsis, however, note that the first and second categories above spell together Daodejing (Canon of the Way and Virtue), the other common name for the canonized Laozi; Cheng's third category marks out the (written) interpretive lineages by which the Laozi was transmitted in Cheng's time. The structure of his overview mirrors, in part, the terse bibliographies found in the early dynastic histories. The “Yiwenzhi” 藝文志 (Record of Arts and Letters) bibliography in the Han shu 漢書 (Han History) provides much of the same data, listing first the name of a text, then the interpretive lineage, and then some accounting of its codicological features:

老子鄰氏經傳四篇。

Laozi, Lin lineage, jing (canon) and zhuan (commentary), four pian-scrolls

老子傅氏經說三十七篇。

Laozi, Fu lineage, jing and shuo (explications), thirty-seven pian-scrolls

老子徐氏經說六篇。

Laozi Xu lineage jing and shuo, six pian-scrolls

劉向說老子四篇。

Liu Xiang shuo Laozi, four pian-scrollsFootnote 104

These are precisely the data items most pertinent to the Laozi's textual identity in early imperial China: names of books, their status as jing and hence their relation to interpretive schools that transmitted them; as well as their codicological manifestations (number of chapters and scrolls).Footnote 105 The elements of Cheng's overview that official bibliographies do not address, such as the name Daodejing, or tallies of the number of graphs and chapters, are provided by the punctuation and paratextual sequences in some of our earliest manuscript sources.Footnote 106 Cheng did not ever live to see the Mawangdui, Guodian, or Beida manuscripts of the Laozi, but all these versions offer new perspectives on the features that were crucial both to the Laozi's integrity as a book and to Cheng's synoptic scheme.

Paratextual Markers of Editorial Intentionality: Making Books Books

The data items identified by Cheng Xuanying, by early bibliographers, and by the manuscripts themselves, reveal an interpretive environment in which the Laozi has a clear “textual identity.”Footnote 107 Titles, the first crucial piece of data for imperial bibliographies, are also found in excavated manuscripts of the Laozi: The Xianger manuscript has a postface that says Laozi Dao jing 老子道經, below which Xianger 想爾 is written on a separate line; in the new Beida manuscript, the upper (38′–81′) and lower (1′–37′) scrolls are labeled respectively Laozi shang jing 老子上經 (Laozi upper canon) and Laozi xia jing 老子下經 (Laozi lower canon), on the verso of each scroll's third slip; the Mawangdui manuscripts are less consistently titled, their names appearing only in the Laozi B 老子乙 manuscript, where brief postfaces record them as De 德 and Dao 道.Footnote 108 The Guodian Laozi manuscripts, in contrast, do not bear any explicit titles, making it difficult to determine their nature and purpose.

Character tallies, which are found in a number of manuscripts from early China, are another indication that accurate reproduction of the text, rather than the text's free use and adaptation, was a desideratum of those who produced a manuscript. The presence of a verifiable number at the end, like computational checksums now used to prevent errors in data transmission, strongly suggests that the copyist strove for accurate reproduction. For the Laozi, the question of character count becomes especially important at least by the late Eastern Han or early medieval period, but it was not necessarily so from the beginning, at least in early records of the legend that portray Laozi transmitting his teaching to Yin Xi 尹喜 on his way westward out of China, here related by Sima Qian 司馬遷:

老子修道德,其學以自隱,無名為務。居周久之,見周之衰,乃遂去。至關,關令尹喜曰:「子將隱矣,彊為我著書。」於是老子乃著書上下篇,言道德之意五千餘言而去,莫知其所終。

Laozi cultivated Daode (The Way and Virtue). His learning was attained in reclusion and his concern was the nameless. He had lived long in Zhou and saw Zhou's decline, so he left. When he got to the [border] pass, the Director of the Pass, Yin Xi said: “You, sir, have determined to go into hiding; could you be bothered to write something for me?” Thereupon Laozi wrote a book in upper and lower pian-scrolls, discussing the significance of Daode in five thousand and some characters, whereupon he left. No one knows where he ended up.Footnote 109

After Sima Qian, the numbers in this story took on a much more rigid doctrinal significance, and the book often known simply as the Wu qian wen 五千文 (Five Thousand Characters), was understood not to have “five thousand and some characters,” but to have exactly Five thousand characters, no more, no less. Or, in some doctrinal debates, precisely one less, as is explained by Cheng Xuanying: