One of the great achievements of Michael Loewe's remarkably long career as one of the pre-eminent scholars shaping Western views of the history of early China has been the reconstruction of events that took place in the time between the final stage of Emperor Wu's 武 rule (141–87)Footnote 1 and the rise of the usurper Wang Mang 王莽 (r. 9–23 c.e.). The history of the first century of Han rule, i.e., the second century b.c.e., had always been comparatively well known because it was described in detail in Sima Qian's 司馬遷 (145?–87?) Historical Records (Shi ji 史記)Footnote 2 and quoted again and again in the works of Chinese men of letters until the end of imperial China. Far less prominent have been the historical figures acting during the second century of Han rule. Loewe's trailblazing articles on this period, which became a basis for his book Crisis and Conflict in Han China, as well as his contributions to volume one of The Cambridge History of China, laid the groundwork for future research on this topic.Footnote 3 His contributions have been so persuasive, however, that little work has been done on the history of the first century b.c.e. after those two books. Indeed, it is not easy to find subjects pertaining to this period that have not been touched upon by Michael Loewe at least once. As a result, despite a wealth of scholarship on Sima Qian and the Shi ji during the past fifty years, there is a striking dearth of Western-language publications on Ban Gu 班固 (32–92 c.e.) and his Han shu 漢書 (History of the Han).Footnote 4

Ban Gu has often been characterized as a historian who adhered to the principles of Confucianism, at least as long as they were accompanied by some ideas of Qin legalism. One basis for this claim is Ban's comments at the end of the biography of Sima Qian in which he reproaches his predecessor for having favored political tenets influenced by some kind of Daoism, over the Six Classics, standing in the eyes of many for Confucianism.Footnote 5 A more complex picture, however, emerges over Confucianism.Footnote 6 The politics of expansion of Emperor Wu of Han that were continued by his great-grandson Emperor Xuan 宣 (r. 74–48) have often been described as inspired by the ideas of legalism while the views of its opponents were “Confucian.” This conflict at the court of Emperor Wu and his successors found vivid expression in a debate that took place in 81, purportedly transcribed, with emendations, later by Huan Kuan 桓寬 in his Discussions on Salt and Iron (Yantie lun 鹽鐵論). True, that text's proponents of a state-centered approach to economics who defend Emperor Wu often make fun of the followers of Confucius (Ru 儒), and they themselves are not Confucian at all. Meanwhile, their opponents do indeed exalt the position of Confucius and his followers. Ban Gu is sometimes described as arguing in a manner like the opponents of state power.Footnote 7 At the same time, he is also suspected of having invented the so-called “victory of Confucianism” under Emperor Wu.Footnote 8 That there was such a “victory” is usually assumed because Emperor Wu established an imperial Academy with academics specializing in each of the Six Classics. Ban Gu commented on Emperor Wu's reign that he had “abolished the hundred schools and made shine the Six Classics as a standard.”Footnote 9 The second victory reportedly took place when Emperor Yuan 元 (r. 48–33) acceded to the throne. This second victory was different from the first one: now, knowledge of the Classics for the first time became the major criterion for selecting officials for the highest positions in the imperial bureaucracy.Footnote 10

Homer Dubs, in his translation of the Annals section of the Han shu, described the “victory of Confucianism,” often using this metaphor.Footnote 11 This description has been most influential in shaping Western scholarship's view of Ban Gu. What Confucianism actually meant to Ban Gu, however, remains somewhat unclear in Dubs's history. Although he mentioned that Emperor Xuan also criticized the followers of Confucius (Ru), a term that Dubs invariably translated as “Confucians,” he thought that this victory was an organic process in which Emperor Wu, Emperor Xuan, and Emperor Yuan all played important roles.Footnote 12 However, Ban Gu's Han shu is actually full of biting criticism of the Han Ru, and it is difficult to reconcile this impression with what has been said up until now in secondary literature on the subject. There is, thus, a need to better clarify the position that Ban Gu held, and this essay undertakes to do precisely this.

Although it is clear that, according to Ban Gu, the Ru took Confucius as their common intellectual ancestor,Footnote 13 in the biographies that Ban Gu wrote in his Han shu, all Ru shared only that they were educated in the Classics, not that they adhered to the values of classical Confucianism. Keeping in mind that they themselves, according to Ban Gu, seem to have thought that it was this classical education that turned them into followers of Confucius, it seems reasonable to translate this term as “classical expert,” not as “Confucian.”Footnote 14 The Han shu is so comprehensive a history that it would be impossible in a single essay to delve into all of the relevant passages that would enable us to fully understand Ban Gu's ideas about “Confucianism.” Therefore, this essay is simply a first step in that direction. Our point of departure will be Ban Gu's description of the crucial transition from the rule of Emperor Xuan to that of his son Emperor Yuan, when the “second victory” of Confucianism supposedly occurred.Footnote 15 It was actually a major break that took place. As the reader will see, Ban Gu's overall assessment of Xuandi was much better than that of Yuandi, even if the latter supported classical experts. Expertise in the classical texts, which according to traditional wisdom went back to a redaction by Confucius, was not Ban Gu's primary criterion for judging the efficacy of officials and rulers. To the contrary, he thought that classical experts actually did not manage to prevent the decline of the Han or that they may even helped to ruin them.

This does not say that Ban Gu did not value classical scholarship and the teachings of Confucius himself. It is obvious that he did so, as can be seen by his arrangement of the different groups of philosophical thinking as well as several other indicators. The Ru were important to him. Yet, as far as the second century of the Han was concerned he apparently did not discover many examples of classical experts who were good scholars and at the same time also able politicians. Whenever Ban Gu uses the term ru in his history of the second century of the Former Han period the reader feels his skepticism about their abilities and their honesty. The opposite is true as far as legal experts are concerned. Legal experts by and large seem to belong to the group that Michael Loewe has described as modernists, the proponents of state power in the Discussions on Salt and Iron. Quite obviously, for the period under description here, Ban Gu's classical experts are Loewe's Reformists, the opponents of a strong state. According to Ban Gu they paved the way for Wang Mang, and thus they were responsible for the fall of the Former Han.

Emperor Xuan and Emperor Yuan: Contrasting Pictures

The first ruler of the Han to have declared that he received an education in the Classics was Emperor Zhao 昭 (r. 87–74), who as a child succeeded Emperor Wu as ruler over the Han empire. In an edict preserved in Han shu, he proclaimed that he had studied the Classic of Filial Piety (Xiao jing) 孝經, the Analects (Lun yu 論語), and the Documents (Shang shu 尚書), although out of politeness he added that he did not really understand them.Footnote 16 There are no additional comments on the Classics found in Zhaodi's Annals, but in the biography of Wei Xian 韋賢 (c. 137–c. 56), a famous Ru scholar who came from Zou 鄒 in Lu 魯 kingdom, the hometown of Mengzi 孟子, we learn that he taught the Odes classic to Emperor Zhao.Footnote 17 Of Emperor Xuan we learn that he studied the Odes, the Xiaojing, and the Analects with an unnamed teacher.Footnote 18 Having been educated in the Classics did not necessarily convince an Emperor such as Emperor Xuan to believe that knowledge of these texts’ contents should be the main criterion for entrance into administrative service. But it seems to have been an important element in his curriculum vitae that made him an excellent candidate for becoming an emperor after the King of Changyi 昌邑, a son of Emperor Wu, had behaved so disastrously that he was removed from the throne after only twenty-seven days.Footnote 19 The King of Changyi had received an education in the Odes but this had apparently not changed his character.Footnote 20

In fact, when Emperor Xuan first selected teachers to educate his son, he chose a man called Bing Ji 丙吉 (d. 55) as the main tutor.Footnote 21 Bing Ji came from Lu (modern Shandong), home of many classical experts, although he himself had chosen to study the Statutes and Ordinances (lü ling 律令) and had been a prison officer early in his career.Footnote 22 Thus, Bing was not particularly a Ru scholar, and Emperor Xuan does not seem to have considered a knowledge of the Classics the prime desideratum for selecting a tutor. He had established his son as his crown prince at the age of seven in 67. As Bing Ji had saved the life of the future Emperor Xuan when Emperor Wu during his final years attempted to exterminate the family of his deposed crown prince, the grandfather of Emperor Xuan,Footnote 23 he naturally enjoyed favor with the young emperor. Shu Guang 疏廣 (fl. 70–60), the Junior Tutor of the crown prince, who hailed from Donghai 東海 (also modern Shandong), had learned the Annals classic, which he had taught at home before receiving a post at court. When Bing Ji shortly afterward became Imperial Counselor, the second highest office in the empire, Emperor Xuan promoted Shu Guang to become Senior Tutor, and chose Shu Shou 疏受, a nephew of Shu Guang, to become Junior Tutor. Both men retired when the crown prince was twelve sui and had learned the Analects and the Classic of Filial Piety.Footnote 24

Possibly a more important influence on the crown prince was exerted by Xiao Wangzhi 蕭望之 (107–47), a famous Ru, also from Donghai, who had studied the Odes and Analects, the latter with Xiahou Sheng 夏侯勝 (c. 150–60), a scholar from Lu who had also been the teacher of Emperor Zhao's widow.Footnote 25 This Xiahou Sheng often encouraged his students by telling them that the easiest way to gain an official post was to study the Classics.Footnote 26 (One wonders whether Ban Gu thought that this was a good idea.) Xiao Wangzhi had slowly risen to prominence under Emperor Xuan. Yet, after the emperor appointed him to become governor of a commandery, his desire to get back to the capital was so strong that he submitted a memorial suggesting that Emperor Xuan should employ in his court administration specialists in the Classics like himself. He was duly recalled to court, but then received a post that he deemed too lowly to accept. The emperor ordered someone to tell Xiao that he could not expect to gain a higher office unless he proved himself capable in practical service.Footnote 27 In the years that followed, Xiao Wangzhi argued several times against an aggressive stance against the steppe Xiongnu 匈奴. In 59, Xiao Wangzhi became Imperial Counselor, following Bing Ji who was promoted to the position of Chancellor. Three years later, in 56, Xiao Wangzhi again spoke up, warning that the Han should not wage war against the Xiongnu while arguing against a program to build granaries. The emperor ignored this advice, and since his proposals turned out to be successful, one might conclude that he had been right to make them. Yet, Ban Gu clearly wants his reader to understand that Xiao Wangzhi had been wrong. In a memorial submitted to the throne, he blamed himself and also the other highest ministers.Footnote 28 Probably correctly, Emperor Xuan interpreted his memorial as a critique of Bing Ji and demoted Xiao Wangzhi, who then became tutor to the crown prince, a position that at the moment, politically speaking, seemed unimportant, but was to become crucial over time, because Emperor Xuan's heir, the future Emperor Yuan, seems to have been most impressed by him.Footnote 29

Likely when Emperor Yuan was eighteen years old, a famous dialogue took place between him and his father that is recorded at the beginning of his Han shu Annals chapter. There, it says that when the crown prince had grown up (zhuangda 壯大),Footnote 30 he was:

柔仁好儒。見宣帝所用多文法吏,以刑名繩下,大臣楊惲、盍寬饒等坐刺譏辭語為罪而誅,嘗侍燕從容言。「陛下持刑太深,宜用儒生。」

soft and sympathetic and liked the classical experts. He saw that many of those whom Emperor Xuan had employed were functionaries well-versed in the written statutes who had subjected Han subjects to the strict line of the [legalistic] “punishments and their names”; and that [his father's] great officials—Yang Yun and Ge Kuanrao, among others—had been [wrongly] tried, sentenced, and executed for critical and derogatory sayings. [Hence] once when he was attending Emperor Xuan at a banquet, he said, with a deferential bearing, “Your Majesty is too severe in applying the laws. It would be proper to employ classical masters [in your government].”Footnote 31

To understand what Ban Gu thought of the crown princes’ ideas, one first must look at the biographies of the two officials Emperor Yuan mentioned. Yang Yun (d. 54) was the grandson of Sima Qian, Ban Gu's predecessor in writing history. On reading his biography in Han shu 66, one does not get the impression that Ban Gu felt much sympathy for him. On the contrary, Ban Gu suggests that he was disrespectful and thus had only himself to blame for his execution.Footnote 32 In other places in the Han shu, however, Yang Yun is said to have associated with classical experts.Footnote 33 Ge Kuanrao (d. 60) is described in an ambivalent way by Ban Gu.Footnote 34 On the one hand, he was a good, uncorrupt, and upright officer, and the Emperor had initially chosen him because of those qualities. On the other hand, he liked to slander and as a matter of fact destroyed others.Footnote 35 A colleague called him a “madman” (kuangfu 狂夫) and warned him to be more prudent, advice that he failed to act upon. Ban Gu agreed with the colleague. He judged all men whose biographies he assembled in chapter 77 of the Han shu to have fallen into the trap of being “too rash or too timid” (kuang juan 狂狷), citing an Analects line.Footnote 36

Ge Kuanrao was able to embark upon his official career because he was versed in the Classics (ming jing 明經).Footnote 37 When he saw that Emperor Xuan relied on punishments and the laws (xingfa 刑法) and employed officials from the ranks of the eunuchs, he was of the opinion that the sagely Way was in decline and the arts of the classical experts were no longer being practiced.Footnote 38 According to him, study of the Statutes and Ordinances had taken the place of the study of the Odes and the Documents classics. As a consequence, he implicitly suggested that Emperor Xuan should abdicate and hand over the empire to a more worthy person.Footnote 39 Small wonder that the emperor was enraged and handed him over to the law officers, after which he slit his own throat. Ban Gu adds that as he had done such good work before, there was no one among the population who did not commiserate with him. In his Appraisal, he deplores Ge Kuanrao's failure to accept his colleague's wise advice, which would have enabled him to survive. “Then he would indeed have come close to the worthy officials of the past” (斯近古之賢臣矣).Footnote 40 Ban's dismissiveness of Ge's exaggerated behavior is similar to his reaction when discussing an earlier case in which a classical expert suggested that Emperor Zhao should abdicate.Footnote 41 When Emperor Xuan heard what his son had said, he flushed with anger and said,

「漢家自有制度,本以霸王道雜之,奈何純住德教,用周政乎!且俗儒不達時宜,好是古非今,使人眩於名實,不知所守,何足委任!」乃歎曰。「亂我家者,太子也!」

“The Han dynasty has its own regulations and measures, which are variously taken from both the ways of the hegemons and the [ideal] kings. How could I trust purely to moral instruction and use the Zhou way of governance? The vulgar Ru moreover do not understand what is appropriate to the time. They love to approve whatever is ancient and disapprove whatever is recent, confusing people about names and realities, so that they do not know what they should cherish. How could they possibly be entrusted with responsibility?” Thereupon he sighed and said, “The one who will bring chaos to our ruling house will be my heir apparent.”Footnote 42

Ban Gu wants his reader to understand that Emperor Xuan was skeptical about the capacities of classical experts to become good administrators. He issued a strong warning that they would destroy the dynasty. We know what Ban Gu thought, when we read his concluding Appraisal of Emperor Xuan's reign:

孝宣之治,信賞必罰,綜核名實,政事文學法理之士咸精其能,至于技巧工匠器械,自元、成間鮮能及之,亦足以知吏稱其職,民安其業也。

[The fundamental principle in] the government of the Filial Emperor Xuan was to make rewards dependable and punishments certain and to examine and match names with realities. In matters of government, the gentlemen engaged in document drafting and legal administration all enhanced their capacities. Even the vessels and tools made by his skilled workmen and artisans could seldom be matched by those made in the time of Emperors Yuan and Cheng. This suffices to indicate that his officials were worthy of their positions and that the common people were satisfied in their occupations.Footnote 43

Plainly, Emperor Xuan achieved more than his successors who were far more influenced by “Confucianism,” in Ban's view. Ban Gu called his reign a “mid-dynastic renaissance” (zhongxing 中興), comparing it to those that had taken place under the best rulers of the Shang and Zhou dynasties.Footnote 44 Thus, we know that Ban Gu approved of Xuandi's style of governance. By contrast, his father Ban Biao had said of Emperor Yuan,

少而好儒, 及即位, 徵用儒生, 委之以政, 貢、薛、韋、匡迭為宰相.而上牽制文義,優游不斷,孝宣之業衰焉。然寬弘盡下,出於恭儉,號令溫雅,有古之風烈。

When he was young, he liked the Ru, and when he ascended the throne, he summoned to court and gave posts to the classical masters, entrusting them with governance. In turn, Gong Yu 貢禹 (d. c. 62), Xue Guangde 薛廣德 (fl. 59–43), Wei Xuancheng 韋玄成 (fl. 61–38), and Kuang Heng 匡衡 (d. c. 30) became his chancellors. The emperor, however, was impeded by the letter of the law, so that he proved indecisive, and thus the achievements of the Filial Emperor Xuan went into decline. Yet Emperor Yuan was broad-minded, and he let his subordinates express themselves fully. He was outstanding in his respectfulness and self-restraint. His proclamations and edicts are polished and elegant, and they have the spirit and fire of the Ancients.Footnote 45

This assessment is positive at the end, if it also contains criticism. Emperor Yuan relied on classical masters (Dubs's “Confucians”) and was not good at making decisions, although people at least could speak freely under him. If we look at the assessments of the two emperors in the last chapter of the Han shu, we see a pattern: unrestrained praise for Emperor Xuan, a more mixed description of Emperor Yuan (particularly Ban's remark in the Appraisal that eunuchs at the court “besmirched Our dynasty's bright virtue” hui wo mingde 穢我明德).Footnote 46 Ban Biao does not comment on the “classical masters” here, but their biographies deserve a closer look. Before proceeding to them, however, one must briefly mention the short attempt to “have the future Emperor Yuan supplanted by the son of another consort.”Footnote 47

Emperor Xuan's first empress had been a woman of low birth whom he had married before he became emperor. She gave birth to the future Emperor Yuan, but was later poisoned by Huo Guang's wife, who wanted the emperor to marry her own daughter, which he eventually did. The whole poisoning story soon came out, and after the death of Huo Guang in 68, Emperor Xuan established the son of his first wife as his successor. And when the entire Huo family fell shortly afterward, the Huo Empress was duly demoted.Footnote 48 At that point, Emperor Xuan wanted to establish his favorite, the Beautiful Companion Zhang 張, as empress. Out of consideration for Emperor Yuan's mother, who had been murdered, he instead selected a woman named Wang 王 to become empress, and she was to assume the role of mother to the heir, because she had no children herself.

Beautiful Companion Zhang did have a son, named Liu Qin 劉欽, who became King of Huaiyang 淮陽, and who, when he was grown up, “liked the Classics as well as the Statutes and Ordinances” (好經書法律).Footnote 49 He had a sharp mind, and he was gifted, so that “the emperor cherished him very much” (帝甚愛之). Several times, the emperor sighed in the presence of the King of Huaiyang, saying, “You are truly a son of mine!” (真我子也).Footnote 50 But although Emperor Xuan intended at one point to establish Liu Qin as heir and his mother as empress, he never did so, because he commiserated with the current heir, who had lost his mother as a small child. Instead, he sent Wei Xuancheng, a classical expert, to become a tutor to the King of Huaiyang, teaching him to be at peace with the decision.

What interests here is that the King of Huaiyang liked both the Classics and the Statutes and Ordinances, and he favored neither to the exclusion of the other. That made him an attractive candidate for the throne, according to Ban Gu.

Jing Fang and Xiao Wangzhi as Examples of Classical Expert's Failures, the Rule of the Eunuch Favorite Shi Xian

Wei Xuancheng succeeded only partly with his education of the King of Huaiyang in the values of the Classics the Ru taught. When Emperor Yuan came to the throne, Zhang Bo 張博 (d. 37), an uncle of Liu Qin, began to convince the king that Qin could become emperor should Emperor Yuan die. This uncle relied on a classical expert named Jing Fang 京房 (77–37) with whom he had studied and to whom he gave his daughter in marriage. Jing Fang, a major Changes (Yi jing 易經) expert specializing in the interpretation of natural phenomena, such as catastrophes and anomalies, had become a Palace Gentleman (i.e., courtier) in 45. The emperor was pleased with him because his advice “often hit the mark” (lü zhong 屢中). For example, in 38 or 37, he suggested that the performance of all officials should be systematically reviewed, to remove all those who had performed no meritorious service. Ministers and their superiors in the Executive Council, however, thought this suggestion could potentially foster a system of mutual distrust. Only two classical experts agreed with Jing.

Jing Fang also attacked the Prefect of the Palace Writers, the eunuch Shi Xian 石顯, who at that time monopolized power at court.Footnote 51 Shi Xian managed to convince Emperor Yuan to make Jing Fang a commandery governor, so as to remove him from the court.Footnote 52 Jing Fang submitted three memorials in a row, in an attempt to return to the capital, in which he suggested that the yin 陰 powers were obstructing the yang 陽, an obvious, if indirect reference to the power of the eunuch Shi Xian (yin), who then was stronger than the emperor (yang) himself. Zhang Bo, for his part, also used Jing Fang's readings of catastrophes to draw up a memorial for Liu Qin, requesting that he be allowed to come to the capital. Although at first reluctant, because he feared Shi Xian's eloquence and experience, Jing Fang came to agree with Zhang Bo's plan. In the end, Shi Xian got wind of the affair, and as soon as Jing Fang was out of the capital and no longer had direct access to the emperor, Shi Xian accused Zhang Bo and Jing Fang of high crimes, with the result that both were executed in 36.Footnote 53

The reader may wonder what Ban Gu thought of Jing Fang. The remark that he “often hit the mark” probably is a reference to the Analects in which Confucius remarked about his student Zigong 子貢 that he “often hit the mark”; the citation, however, also seems to suggest that this was due to pure luck, not real knowledge.Footnote 54 Also, in his concluding chapter Appraisal of Han shu 75, which includes Jing Fang's life, Ban Gu quotes Zigong with the remark that the master did not talk about the way of Heaven.Footnote 55 This seems to criticize Jing Fang's speculations, a suspicion that becomes even more probable in light of Ban Gu's enumeration of the most famous Yin Yang specialists in Han times, among them Jing Fang, which reiterates Ban Gu's conclusion that some of these specialists were lucky to sometimes hit the mark in their speculations. Ban Gu explicitly criticizes Jing Fang for not being able to judge weighty versus petty matters; he further comments that his death was due to his lack of concern with political realities.Footnote 56

An especially interesting aspect of this story is that Emperor Xuan seems to have liked his son Liu Qin because he had knowledge of the Statutes and Ordinances, as well as the Classics. The emperor was no pure legalist, quite obviously. He liked the Classics, but he was opposed to their exclusive use in governing, because he thought that classical experts often tended to be impractical. Han shu several times mentions the fact that the emperor had had important experiences in his youth, when he was “living among the people” (minjian 民間). That experience, for example, taught him that the population suffered from the harshness of some officials;Footnote 57 also early on, when “living among the People,” he had heard the classical expert Xiao Wangzhi praised, so he was keen to employ him when he began to rule on his own, in 67.Footnote 58

Xiao Wangzhi was one of the foremost classical experts under Emperor Xuan and the tutor of his son, as mentioned. In his biography, we again read of Emperor Xuan's predilection for the men who knew the laws. When Emperor Xuan was on the point of death, he named various ministers who could be entrusted with the affairs of state, among them Xiao Wangzhi. It was Xiao Wangzhi who then selected the young Liu Xiang 劉向 (at that time named Liu Gengsheng 更生), to look after Emperor Yuan, and the young emperor was very impressed by these men. Formerly, Emperor Xuan

不甚從儒術, 任用法律, 而中書宦官用事. 中書令弘恭、石顯久典樞機, 明習文法.

had not paid much heed to the arts of the classical experts, as he relied mainly on the laws and regulations. Meanwhile, the eunuchs employed in the office of Palace Writers had their own responsibilities and their Director Hong Gong and his assistant Shi Xian had long been accustomed to taking in hand the levers of power, being well-practiced in the handling of documents and the application of the laws.Footnote 59

Hong Gong (died c. 45), Shi Xian (fl. 48–33), and ShiiFootnote 60 Gao 史高 (d. 42), one member of the Shii 史 consort clan of Emperor Xuan, got along well, and it was they who decided matters according to the precedents (gushi 故事), without heeding the views of Xiao Wangzhi. This brought Xiao Wangzhi into continual conflict with the triumvirate, which led to his suicide shortly afterward.

Xiao Wangzhi tried to promote classical experts for the Censorate, because they did not “merely follow the precedents” 獨持故事, as Shi Xian and his allies did. This expression suggests that by Ban Gu's terminology Ru actually were the faction that Michael Loewe termed “Reformists,”Footnote 61 who hoped to introduce major changes to the ritual rulings of the Han. Ban Gu, more conservative, tended to disagree with the controversial view that there should be ritual reforms.Footnote 62 Although Ban Gu is not explicit about this, one must conclude from the account that follows that he thought Xiao Wangzhi did not really understand the rules of realpolitik. In 47, Shi Xian and Hong Gong brought charges against Xiao, claiming that he wanted to alienate the emperor from his maternal relatives in two consort families. Xiao defended himself but Hong Gong and Shi Xian recommended that the emperor turn over Xiao Wangzhi and his allies, such as Liu Xiang, to the lead judicial officer, the Commissioner of Trials. Unfortunately for Xiao, the emperor had just come to the throne and did not understand that “turn them over to the Commissioner of Trials” meant to throw them into prison. So he approved the recommendation. Later, he innocently called for them and was greatly shocked to learn they were in prison, exclaiming, “So it was not just that the Commissioner was to question them?” He reproached Hong Gong and Shi Xian, and ordered the prisoners’ release.

Hong Gong and Shi Xian were clever and experienced officials. They had Shii Gao tell the emperor that by sending his teacher to prison he had committed a grave mistake that should be kept hidden. According to Shii Gao, the best way out of this embarrassing situation was to have them serve the sentence. The emperor, however, called Xiao back to the palace and wanted to appoint him chancellor. Foiled, Hong Gong and Shi Xian then proceeded to develop a vicious plan. Knowing that Xiao Wangzhi had always had “lofty principles” (gao jie 高節) and would not slander others, they accused him of trying to push the families related by marriage out of court in order to seize all power himself. They said that it would be best “to bend Xiao Wangzhi a bit in prison” (po qu Wangzhi yu laoyu 頗詘望之於牢獄), to cure him of his arrogance. The emperor was reluctant, but Shi Xian reassured him that there was no need to worry. The emperor gave his approval.

In any case, Shi Xian sent the police to surround Xiao Wangzhi's residence. When the messenger with the remand from court arrived, Xiao wanted to end his own life, but his wise wife stopped him, arguing that surely the Son of Heaven did not intend to see him die. Xiao then asked for advice from his own student Zhu Yun 朱雲 (died c. 15), who had studied the Analects with him. He, too, was a man of principle (hao jie shi 好節士), and he convinced Xiao to end his life. Addressing his student Zhu in a very personal tone that reminds the reader of Confucius speaking to his disciples, Xiao said, “You, hurry up and mix me a potion. I would not have my death dragged out for long!” (游,趣和藥來! 無久留我死). Then he swallowed the poison and died. When Emperor Yuan heard this, he exclaimed, “When we discussed this before, I had certainly expressed my doubts that he ever would consent meekly to go to prison! I have, in fact, killed my own worthy tutor!” (曩固疑其不就牢獄,果然殺吾賢傅).Footnote 63 The emperor wept bitterly and berated Shi Xian and Hong Gong, at which they removed their caps and apologized. That was it. Probably they secretly smiled.

Leaving aside the tragedy of Xiao Wangzhi's suicide, Xiao's behavior verges on slapstick. His own high principles—or better: those of his own Analects’ student—kill him. In his concluding chapter Appraisal, Ban Gu laments the fact that the sycophantic eunuchs victimized Xiao Wangzhi—a man who could not be bent, who was considered a leading classicist (ru zong 儒宗), and who “came close to the servants of the altars of the past” (近古社稷臣), a true supporter of the ruling line, in other words. This sounds like high praise, especially since Ban Gu had spoken of Ge Kuanrao in his concluding Appraisal for the preceding chapter as someone who could “have come close to the worthy officials of the past.”Footnote 64 If we look into the summary that Ban Gu provided at the end of his last chapter, we find that there he condemns Xiao Wangzhi as someone “unable to plan and think things through” (bu tu bu lü 不圖不慮), giving this as the reason for his downfall.Footnote 65 Ban Gu's assessment of Xiao Wangzhi is almost the same as his assessment of Jing Fang, in other words: both men stuck to lofty ideals but were lacking in due foresight.

Classical experts of the Latter Han were divided by the question of whether high ministers should be subject to Han law just like everybody else, or whether they should obey an ethical code and commit suicide in the manner of the old warrior-aristocracy, rather than let lower officials touch their persons. While those among them who followed the Reformists of the Former Han relied on the famous sentence from the Record of Rites (Li ji 禮記) that “Corporal punishments were not to be applied to dignitaries” (xing bu shang dafu 刑不上大夫), the successors to the Modernists did not agree.Footnote 66 At the end of the Eastern Han, the philosopher Zhongchang Tong 仲長統 (180–220) referred to the Western Han thinker Jia Yi 賈誼 (200–168) as the first person to voice what later became a Reformist idea.Footnote 67 Ban Gu, who tended to adhere to Modernism, obviously was skeptical that Xiao Wangzhi's moral radicalism was wise, as we can see in Ban's treatment of Zhu Yun in another chapter. In his concluding Appraisal for that chapter devoted to classical experts like Zhu, Ban quoted Analects 13.21 again, on the comparative undesirability of rash and timid students of the Classics.Footnote 68

Shi Xian is represented in the biographies of Jing Fang and Xiao Wangzhi as a wily manipulator who saw to it that virtuous Ru were killed. Apparently, simultaneously he was seen as an official who adhered to the precedents of the ruling house and the Statutes and Ordinances in a way that Emperor Xuan liked. Ban Gu also devoted a biography to Shi Xian, which he placed in his chapter on the male favorites of the Han emperors. There, we read that in his youth Shi Xian had been castrated after committing some offence. Although he became a palace secretary (Zhong Shangshu 中尚書) under Emperor Xuan, he rose to power under Emperor Yuan, several years after Yuan had ascended the throne, after the death of Hong Gong, the eunuch who had been his superior and with whom he had connived to provoke the suicide of Xiao Wangzhi.

After some years on the throne, Emperor Yuan became ill and moreover was over-preoccupied with music and pleasure, so he did not personally attend to matters of governance (不親政事). He delegated all important matters to Shi Xian, because he thought Shi had the requisite experience and, as a eunuch, would not have many allies outside of the palace. Emperor Yuan's misplaced trust enabled Shi to harm a great many officials who had tried to act against him.Footnote 69 Apparently, this is when Shi changed his mind about classical experts. Realizing that it was widely rumored that he had killed the famous scholar Xiao Wangzhi, he recommended another classical expert, Gong Yu, who became Imperial Counselor in 44.Footnote 70 This was the first major appointment that Emperor Yuan actually made. Gong died but six months later, and Xue Guangde, another classical expert, followed in that position only to be replaced shortly afterward by Wei Xuancheng, a classical expert. From several passages of the Han shu, we learn that some Ru scholars feared Shi Xian, while others made common cause with him.Footnote 71 These passages shed an interesting light on the Ru employed by Emperor Yuan. As has been shown, Ban Gu does not seem to approve of Xiao Wangzhi and Jing Fang who were active under Emperor Xuan, but they clearly were strong men. Those later classical experts Ban Gu judged to be weaklings who did not dare to act against a powerful eunuch. Education in the Classics did not necessarily serve these Ru scholars in strengthening the realm, by Ban's account.

Major Appointments by Emperor Xuan

When Emperor Xuan came to the throne, all political power was wielded by the regent Huo Guang. Only after Huo Guang's death in 68 did Xuan begin to rule on his own. Some of the officials whom Emperor Xuan employed during his twenty-five-year rule are explicitly labelled as Ru by Ban Gu.Footnote 72 These were men such as Xiao Wangzhi, Xiahou Sheng, or Wei Xuancheng, who according to Michael Loewe belonged to the Reformist camp. Others had either had a purely legal training or received a classical education in addition to a legal one that they had been formed in first. As will be argued below, Ban Gu seems to have valued legal specialists more highly than classical experts, while appreciating a classical education for legal specialists as long as it did not turn them into true Ru.Footnote 73 A good example is Bing Ji who will be discussed in the next paragraph, a more dubious case is Huang Ba. Overall, according to Ban Gu's presentation, under Emperor Xuan Ru were competing with legal experts.

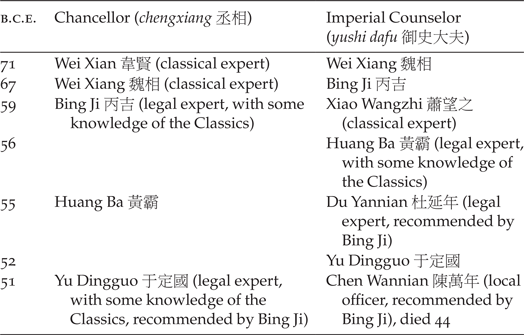

Emperor Xuan made his first major appointments in 67, when he installed Wei Xiang 魏相 (d. 59) as Chancellor and Bing Ji as Imperial Counselor (Table 1). Four years earlier, in 71, Wei Xiang had first been appointed as Imperial Counselor, assistant to the Chancellor Wei Xian, the former tutor of Emperor Zhao. When Wei Xian retired, Wei Xiang replaced him as Chancellor. This pattern of an Imperial Counselor replacing the Chancellor under Emperor Wu was to become normal under Emperor Xuan, as had been true before Emperor Wu. The only Imperial Counselor who did not automatically become Chancellor under Emperor Xuan's rule was the classical expert Xiao Wangzhi, who was deposed and posted to a commandery when it would have been his turn.

Table 1 Major Appointments under Emperor Xuan

Emperor Xuan appointed Wei Xiang because he belonged to a group of men who had earlier spoken against appointments for the sons of the regent Huo Guang after his death. Wei belonged to the faction of Emperor Xuan's mother from the Xu clan, whom the Huo had killed in order to have Emperor Xuan marry a daughter of Huo Guang. A Changes expert, he was in favor of hiring experts well-versed in the Classics (ming jing 明經), i.e., classical experts.Footnote 74 At the same time, like so many Reformists, he voted against launching an attack on the Xiongnu, as had been suggested by Zhao Chongguo 趙充國, a good general praised by Ban Gu.Footnote 75 As Ban Gu described him, “Wei Xiang was by nature stern and inflexible, less tolerant than Bing Ji” (相為人嚴毅,不如吉寬).Footnote 76 The historian obviously preferred Bing Ji who, unlike Wei Xiang, initially had won fame as a legal expert and who had studied Statutes and Ordinances (lüling 律令), although he later learned the “general meaning” (da yi 大義) of the Odes and the Ritual.Footnote 77 Bing had not from the beginning been a classical expert. Rather was he a legal expert but he also acquired some knowledge of the Classics. His emperor respected that he was a practical man.

When Bing Ji was near death, in 55, the emperor asked him who could possibly replace him.Footnote 78 He recommended three men, Du Yannian 杜延年 (d. 52), Yu Dingguo 于定國 (c. 110–40), and Chen Wannian 陳萬年 (d. 44).Footnote 79 None of them had been trained as classical experts, but these were the men on whom Emperor Xuan would later in fact rely. Xiao Wangzhi, a classical expert who held the post of Imperial Counselor for three years, from 59 to 56, did not get a second chance, probably because the emperor did not want classical experts in the highest court positions. According to Ban Gu, the affairs of state were well regulated without them. After Xiao Wangzhi, the position of Imperial Counselor was filled by Huang Ba 黃霸 (d. 51), a man whose life is portrayed in a Han shu chapter devoted to the “mild officials” or to “the officials who adapted themselves to the circumstances” (xunli 循吏).Footnote 80 Among the collective chapters in the Han shu, this is probably the most important one, because Sima Qian had written a similar chapter without mentioning one single Western Han official who fit this category. Ban Gu made the life of Huang Ba his centerpiece in the counterpart chapter. Huang Ba had become Imperial Counselor the year before Bing Ji died, and this may have been the reason why he became Chancellor, while Du Yannian replaced him before the other two had been appointed.

Ban Gu's assessment of Huang Ba was largely positive, although he did voice some criticism. Huang Ba had studied Statutes and Ordinances in his youth, but later studied the Documents from the classical expert Xiahou Sheng. Both of them had been thrown into prison for opposing Emperor Xuan's desire to commemorate Emperor Wu with a special temple name. Xiahou Sheng's criticism of Emperor Xuan was based on his belief that Emperor Wu should not be praised, a typical Reformist position. Huang Ba agreed with Xiahou, and so he prepared to share his fate.Footnote 81 Later, both men were released in a general amnesty. Huang Ba became governor of the important commandery of Yingchuan 潁川, where his extraordinary success as an administrator meant that he became acting Governor of the Capital in the capital region in 63, but he lost that position due to some offences. Soon he was recalled to Yingchuan because he knew how to instill order in the administrative ranks and among the populace, and later he became chancellor.

It seems, however, that Huang Ba was better at fighting crime than he was at being Chancellor. Ban Gu rates him less successful than Bing Ji, Wei Xiang, and his successor Yu Dingguo. Huang tried to advance a project similar to Jing Fang's, namely, an administrative survey of official merits and demerits, which meant that those officials who were without merit would have to publicly kowtow and apologize. These were reforms in the spirit of Han Reformist classicism.Footnote 82 Huang Ba was criticized by Zhang Chang 張敞 (d. 48), a typical functionary, with whom Ban Gu apparently agreed, for Zhang claimed that Huang had invoked omens (“divine birds” that were really wild pigeons) to claim that Heaven sanctioned his policy proposals. Ban Gu clearly ridicules Huang Ba here for trying to use Jing Fang's methods without having enough expertise to do so.Footnote 83 Huang Ba also tried to promote the imperial relative Shii Gao, who was later to make common cause with Shi Xian against Xiao Wangzhi, but after the emperor reproached him, he never dared again lodge such protests. Still, Ban Gu concedes that when it came to “talking about officials who created order among people and minor functionaries, Huang Ba was always ranked first” (言治民吏,以霸為首).Footnote 84 It seems that while Huang Ba may not have been the best choice for the position of a Chancellor, Emperor Xuan was a fairly good judge of character.

Du Yannian was a specialist in the laws and Statutes,Footnote 85 as son of Du Zhou 杜周, a man whom Sima Qian had classified as a “ruthless official” (kuli 酷吏), the opposite of the “mild officials.”Footnote 86 Du Yannian was a loyal subject of the Han ruling house, who helped suppress various rebellions that threatened the dynasty before Emperor Xuan managed to free himself from the Huo family. He retired after three years in office and died shortly afterward.

Yu Dingguo, who came from a family of county prison officers and studied the laws with his father, replaced first Du Yannian (d. 52) and then Huang Ba. After Emperor Xuan rose to power, he became Commissioner of Trials, the head of the judiciary. Only then, over the age of forty, did he study the Annals classic with a tutor, accepting the position of a normal student despite his high position.Footnote 87 Together with Chen Wannian, who became Imperial Counselor in the same year, Yu Dingguo oversaw the smooth transition from Emperor Xuan to Yuan. Yu Dingguo and Chen got along very well. Like Yu Dingguo, Chen Wannian had initially been a local official and an intimate of Bing Ji.Footnote 88 When Chen died, he was replaced by Gong Yu. Yu Dingguo often disagreed with Gong Yu, who was a dedicated Reformist scholar, but as Yu Dingguo was the more experienced person, everyone usually deferred to his opinion. Ban Gu has only words of praise for him.

According to Ban Gu's concluding Appraisal for Emperor Yuan's Annals, Gong Yu is the first in the list of classical experts whom Emperor Yuan appointed. As far as the high officials of Emperor Xuan are concerned, Emperor Xuan preferred legal judges over Reformist scholars, and this tendency Ban Gu applauded. Certainly, there was no “victory of Confucianism” under Emperor Xuan. Ban Gu did, however, appreciate efforts by legal functionaries to learn the “general meaning” (da yi 大義) of the Classics.

Lesser Officials under Emperor Xuan

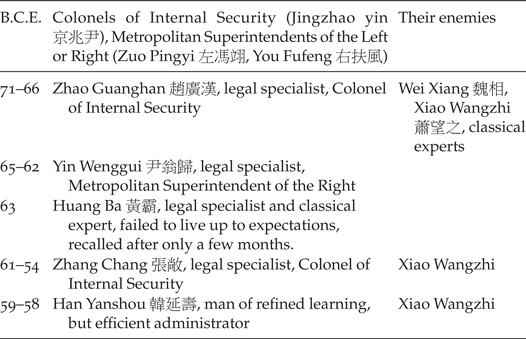

Han shu, chapter 76, provides biographies of four men who worked in lesser capacities under Emperor Xuan, without attaining the highest echelons at court, but reaching the high-ranking position as governor of one of the three metropolitan areas (see Table 2). Most at that rank were legal experts who achieved order but failed to rise higher, due to the circumstances of the time. The first of them was Zhao Guanghan 趙廣漢 (d. 66–64) from Hejian 河間, slightly south of modern Baoding 保定 (modern Hebei). At the beginning of his career, Zhao was quickly promoted until he reached the position of acting Governor of the Capital in the capital region, where he showed great courage in executing an influential strongman who had long bullied the residents of the area. Many of his noble friends had tried to stop Zhao in this but he persevered, and for this, he won praise in the capital.Footnote 89 Like so many other successful officers of Emperor Xuan's reign, he helped force the King of Changyi to abdicate, which paved the way for Emperor Xuan. When he became Governor of Yingchuan, he restored order in a commandery that had been plagued for decades by criminal gangs and by strong local clan networks. He then won military plaudits in a campaign in the northwest, from which he was promoted to the capital post of Governor of the Capital. Importantly, Zhao always ascribed his good deeds to his subordinates. Criminals reportedly humbly accepted the death penalty from him with a smile on their face. The elderly remarked that never, since the beginning of Western Han, had there been greater peace in the capital.Footnote 90 Of course, he was one of the first to recognize the danger from Huo Guang's sons, and he had helped Emperor Xuan to oust them.Footnote 91

Table 2 The Capital Police Chiefs and Their Enemies

According to Ban Gu, so honest was Zhao that even the Xiongnu had heard of his good character.Footnote 92 However, his straightforward character was also the reason for his eventual downfall, when he became embroiled in a private affair that almost cost him his life. Chancellor Wei Xiang, a classical expert, investigated the matter thoroughly, and only an amnesty spared Zhao from execution. Afterward, Zhao had someone executed, believing that he had connived to bring charges against him for some other offense. Then, in 67, a female servant of Chancellor Wei Xiang committed suicide, and Zhao believed that the Chancellor's wife had killed her out of jealousy. After his servant's death, the Chancellor had gone to the family shrine, fasted, and offered sacrifices there, which confirmed his guilt in Zhao's mind. He first tried, unsuccessfully, to blackmail the Chancellor and afterward openly accused him of wrongdoing. Because Zhao was the official in charge, the emperor submitted the file to him, and Zhao personally went with his officers into the Chancellor's residence, forcing his wife to kneel down and make a confession. The Chancellor was then able to bring evidence that the maiden had died while not at home. Xiao Wangzhi then accused Zhao of major crimes, whereupon he was sentenced to death. Tens of thousands of people cried and wept, and there was even one man who offered to be executed in Zhao's place, if allowed, to no avail. Zhao Guanghan was finally executed. The classical experts had won.

Ban Gu ends this biography with the following comment.

廣漢雖坐法誅, 為京兆尹廉明, 威制豪彊, 小民得職,百姓追思, 歌之至今.

Although Zhao Guanghan was tried and executed according to the laws, as Governor of the Capital in the capital region, he had been beyond reproach, a shining example. He had used his awesome authority to regulate the strong and mighty, so that the little people had all been able to practice their professions. The Hundred Families long for him, and they sing about him in ballads down to this day.Footnote 93

Evidently, Ban Gu sided with Zhao Guanghan, not Wei Xiang, the Chancellor. Again, Ban Gu criticizes a man whom he at the beginning of his biography has classified as a classical expert.

The next man treated in this chapter is Yin Wenggui 尹翁歸 (d. 62), a man from Pingyang 平陽 in Hedong 河東 who, like Zhao Guanghan, had become acquainted with the legal writings in his youth when he was a petty officer. Pingyang was the city where the Huo clan had had its base, and its members had tried to challenge him, ultimately unsuccessfully. Yin was just, modest, and incorruptible; he refused all bribes. The merchants, we are told, feared him. Du Yannian and Yu Dingguo both found him extraordinary, and Yu singled him out for praise for his uncorrupt behavior. After he served as Governor in Donghai 東海, he was promoted to the post of Metropolitan Superintendent of the Right in the capital region, where he promoted order. All of his sons eventually became governors.Footnote 94

The last official under Emperor Xuan whose story Ban Gu recounts in this chapter is Zhang Chang (mentioned above in the context of Huang Ba). Like Yin Wenggui, Zhang came from Pingyang, the stronghold of the Huo family, although in his grandfather's time his family had been transferred to Maoling 茂陵, Emperor Wu's mausoleum town. He, too, had been promoted by Du Yannian and belonged to the group of officers who had criticized the King of Changyi, enabling Emperor Xuan to ascend the throne, and later he, too, had spoken against Huo Guang's sons. After several promotions, he finally replaced Huang Ba as Governor of the Capital, in 61, when Huang failed to live up to expectations. What several predecessors had not been able to achieve, Zhang Chang managed to do: for the first time since Zhao Guanghan, the capital region was in peace, and naturally the Son of Heaven was pleased.Footnote 95 Ban Gu adds the remark that Zhang was no equal to Zhao Guanghan, but that he had studied the Annals classic, whose “arts” he found helpful in the administration of his job, with the result that his style of governing displayed some classical elegance (本治春秋, 以經術自輔, 其政頗雜儒雅). This helped him to escape the worst punishment.Footnote 96 This is an interesting statement. It clearly again provokes doubts in Ban Gu's reader about the seriousness of the historian's beliefs in the classical experts, who had become such a strong force at court that it was best to know the Classics for one's career advancement. They helped to escape punishment. Still, in Ban's view, the real capacities needed for bringing order had little to nothing to do with them.

Later, Zhang Chang, who had been good friends with Xiao Wangzhi and Yu Dingguo,Footnote 97 was dismissed because he was related to Yang Yun, the grandson of Sima Qian, but as crime immediately escalated in the capital region, the emperor promptly reinstated Zhang Chang, thinking he could not find another equally good administrator. Zhang was then given the task of restoring order in two commanderies far from the capital, which he did. It so happened that Emperor Xuan died at this juncture. Emperor Yuan wanted to employ Zhang Chang as a tutor for his heir, the future Emperor Cheng 成 (r. 33–7). However, Xiao Wangzhi opposed the appointment, saying that while Zhang was a capable officer, he was not qualified to become the heir's tutor, because he had insufficient talent. Emperor Yuan nevertheless recalled him to the capital, but on his way there he died.Footnote 98

For a third time in only four biographies,Footnote 99 Ban Gu casts the Reformist Ru Xiao Wangzhi as standing in the way of the career of an excellent official who had also learned the Classics, but whose major qualifications lay elsewhere. This explains why Ban implicitly congratulated Emperor Xuan for removing Xiao Wangzhi from his position in 56, although as Imperial Counsellor he would normally have become Chancellor later. Readers will recall Xiao was replaced by Huang Ba who was more capable, a man who did know how to deal with the common people.

Emperors Yuan and Cheng and the Classical experts

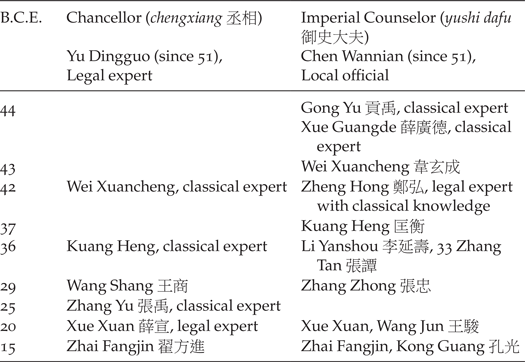

After the death of Chen Wannian, the last Imperial Counselor installed by Emperor Xuan, in 44,Footnote 100 Emperor Yuan for the first time appointed a classical expert for a major position, Gong Yu (see Table 3). As explained in a lengthy introduction for the chapter that contains Gong's and Chen's biographies, the chapter is devoted to scholars who upheld lofty ideals, such as those espoused in high antiquity by the likes of the famous hermits Bo Yi 伯夷 and Shu Qi 叔齊. Despite Ban Gu's acknowledgement of the classical learning of these scholars, in these biographies, he calls attention to the inconsistency between their education and lack of moral standing. He begins this chapter with a man called Wang Ji 王吉 from Langya 琅琊 in Shandong, an expert in the Classics. Emperor Xuan thought that his ideas were farfetched and impractical.Footnote 101 Wang Ji was a good friend of Gong Yu, who also came from Langya. Emperor Yuan called Gong to Chang'an. When Chen Wannian died, he became Imperial Counselor, in which position he went so far as to suggest that the money economy should be abolished because it was in circulation in antiquity.Footnote 102 More proposals about money followed. Emperor Yuan accepted most of Gong Yu's advice, including the famous suggestion that expenditures for the temples of Han ancestors should be reduced,Footnote 103 showing that the classical expert Gong was a Reformist. Gong Yu died only six months after he had been appointed Imperial Counselor and was followed in that office by Xue Guangde from Pei 沛 (less than fifty miles south of Lu 魯 in modern Shandong), a teacher of the Lu tradition of the Odes who had been on Xiao Wangzhi's staff. Not much is known of him, only that he adhered to the same Reformist approach as his predecessor. After only ten months, he retired from office along with Chancellor Yu Dingguo and Marshal Shi Gao because there had been bad harvests.Footnote 104 This opened the way for the appointment of another famous classical expert, Wei Xuancheng.

Table 3 Major Appointments under Emperors Yuan 元 and Cheng 成

Some people seemingly made deliberate use of natural disasters to remove the Chancellor Yu Dingguo, whose appointment had predated the accession of Emperor Yuan. Han shu says that “Those who spoke about these affairs put the blame for them on the high officials” (yan shi zhe guijiu yu dachen 言事者歸咎於大臣). The emperor therefore often called the Chancellor and his ministers to the audience hall, where he said that the process for selecting high officials had not been carried out properly and therefore many in office were incompetent. He then asked to hear what the Chancellor planned to do in this situation. Of course, the Chancellor had no recourse but to apologize for any signs of disorder. When, in 43, frost fell in the spring and the summer was cold, the emperor said that in the east—far away, but the region where most of the classical experts came from—people were in a desperate situation. In his mind, his high officials should take steps to prevent future disasters from happening. When Yu Dingguo asked to be released from service, the emperor made a half-hearted attempt to convince him to remain, but then consented.Footnote 105 At the end of the chapter, Ban Gu praised Yu Dingguo as an official who truly was able to fulfill his duties properly. He obviously thought that had he remained in office, this would have been ideal. Yet, Emperor Yuan did not want him to stay. Apparently he did not fit the ideas of the young emperor about what a good official should have learned. He was not a classical expert, and as stated above Ban Gu said that Emperor Yuan promoted classical experts.

The man perhaps best known for having made the link between natural disasters and those who held power in imperial administration was Yi Feng 翼奉 (fl. 50–40) from Donghai, who had studied the Qi tradition of the Odes with the same teacher as Wei Xuancheng and Kuang Heng, the successor to Wei Xuancheng. Yi Feng regretted the fact that the Han ruling house had no ministers as good as the Dukes of Zhou 周 or Shao 召 in antiquity: “How could it be that those who holding the reins of state do not harbor fears and take even the slightest precautions?” (執國政者豈可以不懷怵惕而戒萬分之一乎).Footnote 106 Yi went so far as to suggest that Emperor Yuan should transfer the capital from Chang'an to Luoyang, probably because the capital would then be closer to the old capital of Western Zhou and the homes of most classical experts, who could then use their networks in a much more efficient way. Yi received much the same criticism from Ban Gu as Jing Fang: his ideas were too speculative and unworkable. In his summary for the chapter that included Yi Feng's biography, Ban was even more critical: he claimed that those who acted like Yi and Jing “in a superficial way came to regret their mistakes, while those who did it more seriously did great damage” (淺為尤悔,深作敦害).Footnote 107

The man who profited most from Yi Feng's omen theories was his classmate Wei Xuancheng, who under Emperor Xuan had risen to the position of one of the Nine Ministers but who was soon dismissed, due to his friendship with Yang Yun. At the end of the biography of Wei Xian, Xuancheng's father, Ban Gu inserted a ditty that was sung about the Wei family: “To send one's sons a basket full of gold is worth less than to give them a single Classic” (遺子黃金滿籯,不如一經). Plainly, to acquire classical learning had become incredibly important for a successful administrative career, yet, again, one wonders whether Ban Gu thought that this was a good thing. He does not himself give an answer to that question. His reader has to decide.

Wei Xuancheng became Tutor of King Liu Qin of Huaiyang, but Emperor Yuan recalled him back to the capital, and within a few years, he reached the position of Chancellor. Ban Gu does not say very much about him, although he remarks, “In upholding the correct and maintaining the weighty, he did not measure up to his father Wei Xian, even if he surpassed him in literary attainments” (守正持重不及父賢,而文采過之).Footnote 108 The main part of Wei Xuancheng's biography is made up of a lengthy discussion of the changes he made to the regulations for the ancestral temples. (See Tian Tian's essay in this volume.) At the end of the biography, Ban Gu's father, Ban Biao, has the last word: that he found Liu Xin's ideas on that subject the best, a clear reproof of Wei Xuancheng.Footnote 109 In addition, Ban Gu reports the remark of Jing Fang that Wei, like Shi Xian, “had for long time not benefitted the people” (jie jiu wu bu yu min 皆久亡補於民).Footnote 110

Similar critiques are registered for Kuang Heng, another Reformist expert from eastern China and a classmate of Wei Xuancheng and Yi Feng. Kuang Heng had been recommended by Xiao Wangzhi, but as “Xuandi did not very much make use of classical experts, he dispatched Kuang Heng back to his office” (宣帝不甚用儒,遣衡歸官). When Emperor Yuan acceded to the throne, he employed Kuang Heng at court. With his first memorial that he submitted at the occasion of an eclipse of the sun and natural disasters Kuang Heng managed to force Yu Dingguo, who was not a Reformist, out of office, calling for new men in government.Footnote 111 At this point, Ban Gu again stresses Yuandi's predilection for classical experts: “As the sovereign enjoyed the arts of the classical experts, erudition and elegant speeches, he began to considerably change the government of Emperor Xuan”Footnote 112 (上好儒術文辭,頗改宣帝之政).

The most important privilege that allowed families related to the Han emperor to stay in power was the selection of the heir. Emperor Yuan had a son by his Empress Wang whom he soon established as crown prince. As is well-known, the Wang family became increasingly powerful during Yuandi's reign, a process culminating in the usurpation by Wang Mang, a nephew of Empress Wang. Just as Emperor Xuan at some point had thought about substituting his heir, Emperor Yuan, too, several times considered replacing his son by Empress Wang with a son by a consort named Fu 傅, but his court convinced him not to do so. Kuang Heng wrote a memorial warning him.Footnote 113 The installation of a new heir would have certainly kept Wang Mang from usurping power, but Reformist experts, out of principle, apparently, were reluctant to see changes made to the heirs apparent, maybe also because the Wang family protected them. (Emperor Yuan seems to have preferred his son by consort Fu only because he was an expert in music, not because he displayed any capacities for leading the realm. Ban Gu's comments on the Fu family are uniformly disparaging.)Footnote 114

Nobody seems to have thought about the third son whom Emperor Yuan had had with a consort née Feng 馮, daughter of Feng Fengshi 馮奉世 (c. 90–38), a famous general to whom, along with his sons, Ban Gu devoted a laudatory chapter, Han shu 79. Feng Fengshi's career and that of his son were blocked by Shi Xian, but also by the Reformist experts Xiao Wangzhi, Wei Xuancheng, and Kuang Heng.Footnote 115 In trying to prevent Feng Fengshi from gaining noble rank, Xiao Wangzhi had once said that Feng Fengshi had made decisions on his own authority.Footnote 116 Kuang Heng brought forward the same arguments against Feng Fengshi's successor in Central Asia. In this case, Kuang agreed with Shi Xian.Footnote 117 As is well known, the Ban family had a strong interest in Central Asia, and again it seems that Ban Gu did not agree with what the Confucian Kuang Heng did. One gets the impression that deep in his heart Ban Gu thought that the son by consort Feng would have been a better candidate for successor to Emperor Yuan, but that there was no chance whatsoever to realize this, under the circumstances.

In 36, Kuang Heng replaced Wei Xuancheng as Chancellor. When Chengdi became Emperor three years later at the age of eighteen, Kuang Heng wrote a long memorial in which he stressed the importance of classical expertise and the correct attitude privileging one's principal wife,Footnote 118 shortly after which he began to attack the eunuch Shi Xian. As Ban Gu remarks, “the former Chancellor Wei Xuancheng, as well as Kuang Heng, had both feared Shi Xian, so they did not dare to deviate from his ideas” (自前相韋玄成及衡皆畏顯,不敢失其意).Footnote 119 But suddenly, now that Shi Xian had lost his support, Kuang Heng began to enumerate Shi Xian's evils and also to name Shi's allies who should be blacklisted. This sudden switch elicited pushback, with the Governor of the Capital Wang Zun 王尊 asking why Kuang Heng had not dared to level these charges before now. Was this not an actual attack on the deceased Emperor Yuan? Emperor Cheng did not heed Wang Zun's advice, because he wanted to demonstrate his care for his high ministers, but “Most of his subjects agreed with Wang Zun” (然群下多是王尊者),Footnote 120 and Ban Gu surely did so as well otherwise he would have let his reader know.Footnote 121 Soon after, in 30, Kuang Heng had to step down, because of multiple mistakes that he and his son had committed.

Kuang Heng was then replaced by Wang Shang 王商 (d. 25), a man who belonged to a consort clan related by marriage to Emperor Xuan, not to the clan of Yuandi's Empress Wang. Like Kuang Heng, Wang Shang had protected the future Emperor Cheng when Emperor Yuan thought about changing his heir.Footnote 122 Wang Feng 王鳳, the brother of Empress Wang and uncle of Emperor Cheng, had become the first in a series of four Marshals of State from the Wang family.Footnote 123 The importance of the position of the Chancellor had meanwhile declined. Although Wang Shang was an upright man who tried to fight the rising influence of the other Wang family of Emperor Yuan's Empress, he failed and fell because he was attacked by Shii Dan 史丹 (d. 3 c.e.), the son of Shii Gao (see above).Footnote 124 With Wang Shang out of the way, Emperor Cheng again established a classical expert as Chancellor. This was Zhang Yu 張禹 (d. 5), a famous specialist in the Analects and a protégé of Xiao Wangzhi.Footnote 125 Upon his accession to the throne, Emperor Cheng raised Zhang Yu to the position of Counselor of the palace (zhu li guanglu dafu 諸吏光祿大夫) so that he led the affairs of the Secretariat with Wang Feng. Out of fear, he several times asked to be dismissed, but Emperor Cheng did not want to dismiss him, so instead he promoted him to Chancellor in 25. Six years later, he retired, but he was still treated with all the deference due a sitting Chancellor. Ban Gu describes Zhang Yu as a greedy and wasteful and licentious man who knew quite a bit about music, a knowledge that certainly interested both Emperors Yuan and Cheng, who liked their musical accompaniments at banquet.Footnote 126 Apparently without any fixed principles, he did not give his students true guidance.Footnote 127

As a former teacher of the emperor, Zhang Yu participated in all major decisions until the end of Emperor Cheng's life. During the reign periods from 16 to 9, when more and more memorials pointed to the dangers posed by the Wang family, Zhang Yu feared for the well-being of his own family. He declared all the accusations to be sheer nonsense; he advised his emperor to “judge with the help of the classical arts of governing these petty creatures with their newfound learning who disrupted the Way and misled others” (新學小生,亂道誤人 … .以經術斷之). A firm friend of the Wangs, he lived out his days happily until his natural death in 5.

Ban Gu disrespected this classical expert, just as he held in low esteem most of the other Reformist experts. Zhang Yu was the man whose editing produced our version of the Analects, the most Confucian of all Classics, and he seems to have exerted a major influence on Emperor Cheng (and not for the better). One wonders whether the famous consort Zhao Feiyan 趙飛燕 of low descent could have arisen so quickly to become empress, if Zhang Yu had opposed her ascent. Instead, by his own example, Zhang Yu encouraged his former pupil to behave as he did.

It seems important to look at what Ban Gu wrote in his Appraisal about the four Reformist scholars whose lives he described in chapter 81 of Han shu:

自孝武興學,公孫弘以儒相,其後蔡義、韋賢、玄成、匡衡、張禹、翟方進、孔光、平當、馬宮及當子晏咸以儒宗居宰相位,服儒衣冠,傳先王語,其醞藉可也,然皆持祿保位,被阿諛之譏。彼以古人之跡見繩,烏能勝其任乎!

From the time when the Filial Emperor Wu had made learning flourish, Gongsun Hong became Chancellor as a classical expert, and later, Cai Yi, Wei Xian and Wei Xuancheng, Kuang Heng, Zhang Yu, Zhai Fangjin, Kong Guang, Ping Dang, and Ma Gong, as well as Ping Dang's son Yan. All occupied positions as Chancellor, because they were leading classical experts. They wore the classical expert's robes and caps and transmitted the sayings of the former kings. Their cultural refinement was acceptable, but in office they just took their salary, secured their positions, and were liable to the criticism that they were sycophants. If one measures them by the traces that the Ancients have left, how could one say that they were able to fulfill their responsibilities [勝其任]?Footnote 128

Ban Gu managed to single out for his criticism exactly those Chancellors whom earlier in his compilation he had characterized as masters of classical learning. It is therefore obvious that Ban Gu condemned them harshly, despite their erudition, because they did not live up to the moral standard that one would have expected from their classical learning.

Conclusion

The main aim of the present article has been to elucidate Ban Gu's reconstruction of late Western Han, and more specifically the reigns of Emperors Yuan and Cheng, which Homer Dubs described as overseeing the “complete victory of Confucianism.” There is little doubt that previous courts, including those of Emperors Wu and Xuan, did not particularly favor the Ru. For although Emperor Wu may have established the first Imperial Academy structure in Chang'an and established positions for the Academicians who taught there, Han Wudi's policies were mostly guided by men who did not share the ideas that scholars would later derive from the Classics. Turning to Emperor Xuan, we find that at the beginning of his reign, his regent Huo Guang dictated Emperor Xuan's choice of officials, and when Xuandi was able to rule on his own, he tried to keep many classical experts out of power, preferring to rely on experienced administrators with expertise in the Statutes and Ordinances. These men cannot be called classical experts, let alone “Confucians,” although some of them acquired some classical learning, which may to some extent have improved their linguistic skills but not altered their ways of thinking. That Ban Gu thoroughly approved of Emperor Xuan's reign becomes clear when one looks at his portrait of that reign.

By contrast, Emperor Yuan promoted classical experts whenever he could do so, but these men proved themselves incapable of preserving the Han ruling house from the depredations by either the powerful Wang family or the eunuch Shi Xian. Ban Gu obviously made fun of the pure-minded Reformist experts, although in some chapters of his history devoted to the Western Han after Emperor Yuan, his satire turned into anger over the incompetence of prominent classicists such as Kuang Heng and Zhang Yu, who failed to guide Emperor Cheng properly. As Emperor Xuan had once predicted, Emperor Yuan's predilection for idealist scholars all but ruined the Western Han.

When reading the biographies that informed this article, chapters 71 to 82 of the Han shu, the reader wonders whether the historian implicitly asks readers to pose the question, What would have happened had Emperor Xuan dared to replace his heir? Ban's use of the phrase that Emperor Xuan “could not bear” (bu ren 不忍) to do it,Footnote 129 is significant, for, according to passages in the Han shu, a good emperor must bear the consequences of harsh decisions, and Emperor Xuan's feelings violated this principle.Footnote 130 A change of heir would probably also have been good under Emperor Yuan. Ban Gu does not dare to say openly that both Emperors Yuan and Cheng were outright failures who should actually have been replaced. Convention and prudence made that rhetoric impossible.

Notably, Ban Gu himself was an accomplished classical expert, and he also wrote about some classical experts whom he respected.Footnote 131 At the same time, in the Han shu, he condemned the Reformist idealists who paved the way for the rise of Wang Mang. We may read the Han shu as an attempt at rehabilitating the legal officers whom Ban Gu sometimes called “officers who adhered to the letter of the law” (wenli 文吏), in this attitude contrasting with Sima Qian, who in multiple passages ridiculed the little “scraper and brush officials” or daobi li 刀筆吏, who had been the pillars of state during the Qin empire and who rose again under Emperor Wu of the Han. Sima Qian had generally praised those officials who adhered to the non-interventionist laissez-faire politics that were at the core of what he called Huang-Lao 黃老 thought.Footnote 132 With some consistency, then, Sima Qian condemned the Annals scholar Gongsun Hong as a strong ally of the overly harsh officials. On balance, classical expertise or its lack was not an important evaluation when it came to judging character and fitness for office; to the contrary, he had condemned important classical experts.

In Ban Gu's telling, the officials who adhered to the letter of the law of the Han shu Footnote 133 look much better than they did in the Shi ji. They represented Modernist policies, which Ban Gu largely supported. At the same time, Ban Gu obviously fought with his brush against Reformist experts who wanted to continue the non-interventionist policies of those men whom Sima Qian deemed to be Huang-Lao adherents. By the time Ban Gu wrote, the world had changed completely. In the first century c.e., the Modernist arguments also began to be clad in the language of the Classics. That process cannot yet be seen in the Han shu. Its traces are to be found in Eastern Han commentaries on the Classics.