INTRODUCTION

Debates in transnational queer studies highlight the problematics of a dichotomous framing between the global and local in shaping the emergence of queer identities, desire, and experiences/encounters in Asian contexts (Jackson Reference Jackson2009; Liu Reference Liu2015; Liu and Rofel, Reference Liu and Rofel2010). In other words, what Ara Wilson (Reference Wilson2006) calls the import-export calculus (where the non-West is the feminized, passive recipient of hegemonic Western queer culture) in the global gay/gaze (Altman Reference Altman1997) arena, often masks the interplay of complex factors that take place locally, temporally, and mutually in relation to global shifts and movements of ideas, peoples, and cultural productions (Jackson Reference Jackson2009). Queer Asia complicates and destabilizes the Asia/West binary as there exist local forms of queerness that develop outside the gaze of the West (Cho Reference Cho and Henry2020; Henry Reference Henry and Henry2020; Jackson Reference Jackson2009; Liu Reference Liu2015; Liu and Rofel, Reference Liu and Rofel2010; Rofel Reference Rofel2007, Reference Rofel2010).

South Korea (hereafter known as Korea) is a country whose relatively recent ascension into the global community of developed nations has ushered in rapid social changes tied to a governmental push to create a more “global Korea.” This pursuit of globalization has reshaped how individuals understand their role in the Korean nation, facilitating a type of neoliberal subjectivity among its post-democracy generations. Nancy Abelmann and colleagues (Reference Abelmann, Park, Kim, Anagnost, Arai and Ren2013) term this chaggi kwalli Footnote 1, or self-reliance, which is deployed in pursuit of cosmopolitan social capital. Following the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, John (Song Bae) Cho (Reference Cho and Henry2020) argues that in Korea, this facilitated the emergence of a complicated neoliberal gay subjectivity tied to intense structural reforms. I argue further that this has not only provided opportunities for individual agency to be lived out, which John D’Emilio (Reference D’Emilio, Hansen and Garey1983) postulates facilitates gay subjectivities within societies through capitalism, but also allows us to examine how this process in Korea is racialized.

My use of the Korea/local–West/global binary in this paper does not seek to reinforce it, rather, I adopt Katsuhiko Suganuma’s (Reference Suganuma2012) position, which purports that modes of queer being that are outside the West/Non-West binary often become intelligible precisely when they are othered. In other words, to highlight the specificities of the local, differences in power, experiences, parameters, and borders can be made visible when held in reference to the hegemonic global. As Suganuma (Reference Suganuma2012) argues, “referencing the binary does not only serve to reinvigorate it but is also a critical tool to dismantle it in the context of queer globalization” (p. 189).

This paper is positioned at the edges of Korean studies, critical race theory, queer globalization, and Pacific studies. I adopt this multidisciplinary approach because as Tom Boellstorff (Reference Boellstorff2005) notes, sexuality is always defined in terms of gender, nation, race, class, and other social categorizations, exposing sexuality to the conjecture of multiple cultural logics. As a Sāmoan researcher, I argue that my researcher identity is also made known in this space by my racialized positionality. Thus, my methodology carries a hybrid cultural logic in acknowledging how this has impacted the questions, direction, and outcome of this research. As such, the deployment and articulation of my Pacific Research Methodology (PRM) framework also allows for an interrogation of how the complex multiplicities of researcher identity directly affect the biases, limitations, types of data, and analyses that are possible in cross-cultural (Korean-Sāmoan) qualitative research.

Drawing on interest convergence theory (Bell Reference Bell and A1980; Delgado and Stefancic, Reference Delgado and Stefancic2017), this paper stories how participants’ racialized encounters with foreign gay men is connected structurally to the way South Korea’s immigration system is racialized. I argue that this system has been designed to fulfill, in differentiated ways, the aggressive pursuit of the Segyhewha or Global Korea paradigm. As such, this paper presents a unique entry point into the conversation around how Whiteness as a structuring hierarchy is produced locally in Korea but can also move across oceans as an accompaniment to transnational mobilities driven by Korea’s globalization aspirations. I purport that these complexities can be apprehended through the narratives of gay Korean men in this study.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In Japan and Thailand, a body of literature is emerging at the intersections of racialized desires, queerness, and notions of inter-Asia queer mobilities (Baudinette Reference Baudinette2016; Kang Reference Kang2017; Mackintosh Reference Mackintosh2010). Korean scholarship in queer studies, in contrast, has focused on mapping queer identities, (in)visibility, and the multiple ways they are imbricated/excluded within South Korean social, religious, state, and family institutions (for example: Bong Reference Bong2008; Cho and Sohn, Reference Cho and Sohn2016; Henry Reference Henry and Henry2020; Kim and Hong, Reference Kim and Hong2007; Kim and Hahn, Reference Kim and Hahn2006; Lim and Johnson, Reference Lim and Johnson2001; Seo Reference Seo2001; Thomsen Reference Thomsen2018; Um et al., Reference Um, Kim and Kim2016). Therefore, I find it a necessary exercise to briefly review relevant literature on race/racialization in Korea and relevant queer scholarship on Korea and draw insights from existing scholarship in Asia that locates itself at the intersections of race and queerness.

According to Choong Soon Kim (Reference Kim2011) many Koreans are deeply affected by the ethnonationalist view of Korean nationalism that advances the notion of Koreans as a nation of “pure-bloods” (sunhyol) descended from a common ancestor. Hyung Il Pai (Reference Pai2000) explains how many Koreans who were raised in the Park Chunghee era (1961–1979) were indoctrinated with the idea of a single national historiography (minjok sahak), that stresses the origins of the Korean national identity in a single unique and pure race (tanil minjok). This imagined national identity, or ethnonationalist construct, is an invented narrative created specifically to ‘other’ foreigners which first emerged prominently during the Middle Age Goryeo (918–1392) period as a response to threats from Chinese and non-Chinese forces (Goulde Reference Goulde1999). The resilience of this ethnonationalist construct in Korea is underscored by many local studies on race/racialization and multiculturalism that elucidate the perpetuation of this racial purity myth into contemporary times (Bae et al., Reference Bae, Choo and Lim2019; K. Han Reference Han2007; Hundt et al., Reference Hundt, Walton and Lee2019; Joo Reference Joo2015; Kang Reference Kang2010).

Since the 1990s, Korea has seen a significant increase in the number of foreign workers and migrants; first as labor migrants and international brides in mostly rural areas, and later through a growing influx of English teachers and business professionals (Park Reference Park2014). Iain Watson (Reference Watson2012) argues that the subsequent emergence of the discourse on multiculturalism in South Korea is driven by the Segyhewa (global Korea) policy that is tied to transnational forms of neoliberalism. Ji Hyun Ahn (Reference Ahn2013) suggests further that this discourse of multiculturalism now passes through the lens of race. Dong-hoon Seol (Reference Seol2012) indicates that this produces a hierarchy among foreign migrant workers, where professional workers and foreign investors (mostly from wealthy Western nations) enjoy the highest status, while less-skilled workers take the lowest position on the employment ladder. Critical race theorists would recognize this as differential racialization—a process in which dominant groups in society constitute racial categories for different purposes in response to shifting needs, most noticeably in the labor market (Delgado and Stefancic, Reference Delgado and Stefancic2017). This suggests that there is a link between Korea’s ethnonationalist construct of the foreigner, the forces of global capitalism, and the racialization of South Korea’s foreign population.

Incho Lee (Reference Lee2011) develops this point further by positing that Koreans understand globalization as part of a ferocious competition among countries, where Korea should gain global leadership and economic power to survive. As such, many Koreans are eager to position themselves closer to role models that have attained economic and political power. Lee also notes that for many Koreans, Whites symbolize economic advancement and have become a global representation of power. English, as part of this ‘global’ Korea, is now a modicum of social capital (Abelmann et al., Reference Abelmann, Park, Kim, Anagnost, Arai and Ren2013; Park Reference Park2011). As such, the ability to demonstrate high English proficiency carries social currency and allows for one to demonstrate cosmopolitan credentials and achieve upward mobility in the job market (Park Reference Park2011). In response, the Korean government set up a special visa category (E2) for education professionals targeting native speakers of English as teachers to meet the explosive demands for what Jin-Kyu Park (Reference Park2009) calls Korea’s obsessive English fever. Benjamin K. Wagner and Matthew Van Volkenburg (Reference Wagner and Volkenburg2011) suggest that due to the specific targeting of wealthy Western nations, these English teachers tend to be White. Thus, this tiered immigration system ties Korea directly to the West as it aims to fulfill a specific neoliberal-driven demand for English education. In contrast, migrants from less affluent Southeast, Central, and South Asian countries are given access to different employment visas that limit the types of work they can legally engage in. They are deployed to manufacturing and lower paid jobs, fulfilling what are called the three Ds: difficult, dirty, and dangerous work that many Koreans are unwilling to do (Kim Reference Kim, Bulmer and Solomos2014).

Queer Korea (Reference Henry and Henry2020), a collection of essays from Korean queer studies scholars edited by Todd Henry, is one of the most recent publications in the field that “problematizes how practices of non-normative sexuality and gender variance have been consistently ignored or thought away in Korea” (p. 8). This volume attends to “pervasive forms of ‘queer blindness’ that surround the peninsula and its inhabitants” (Henry Reference Henry and Henry2020, p. 8). This critique speaks to consistent criticism by scholars in Korean queer studies that the queer subject has been discursively erased from Korean national historiographies (Henry Reference Henry2018, Reference Henry and Henry2020; Seo Reference Seo2001; Thomsen Reference Thomsen2018). Dongjin Seo (Reference Seo2001) attributes this to the process of “orientalizing from within,” arguing this erasure serves specific biopolitical purposes to ensure the reproduction of the heteronormative Korean nation. Henry (Reference Henry and Henry2020) calls these “survivalist epistemologies” and that both “nationalist and postnationalist narratives have overlooked critical light that non-normative sexuality and gender variance can shed on the operation of successive and intersecting structures of power, including colonialism, nationalism, capitalism, and neoliberalism” (p. 8). Although this does crucial work to recuperate the queer subject in relation to structures of power, the role of race and racialization in the lived realities of Korean queer lives is still an analytic that remains relatively underexplored.

Woori Han (Reference Han2018) focuses on the Seoul Queer Culture Festival as a site of “queer developmental citizenship.” Han argues that LGBTQ Koreans seek to oppose the heteronormative narrative of Korean citizenship that singles out queer Koreans for ruining national development by relying on foreign embassies’ support in opposing an aggressive local anti-gay movement. This practice, which involves claiming pride in one’s LGBTQ identity, aligns itself with Euro-American forms of queer citizenship. Han also purports that this has made LGBTQ Koreans less likely to be critical of liberal politics and development hierarchies between Korea and the West. This important contribution speaks once again to the role of the West/Non-West binary or the local/global discussion on how we make known local differences in interrogating queer globalization.

In Japan and Thailand, scholarship that examines the way race intersects and impacts queer desires advocates for a shift away from a direct West/Non-West analytic toward inter-Asian productions of queer desire, necessitating more complicated readings of Whiteness (Jackson Reference Jackson2009; Kang Reference Kang2017). A key insight from Thailand is how local processes around nationhood, citizenship, and a hyper-sexualized Western reading of Thai national identity, shift cross-cultural desirability away from the idealized White gay, toward White East Asians. Dredge Kang (Reference Kang2017) explains that “partnerships with Caucasians can mark Thais as low status (i.e., they are publicly interpellated as paid companions), while East Asian partners are associated with racial similarity, high economic status, and new forms of Asian modernity” (p. 183). They also argue that desiring Whiteness is not the same thing as desiring Caucasians. Lisa Rofel (Reference Rofel2007) details a further complexity through Chinese gay men in mainland China who avoid dating Westerners to demonstrate a commitment to their nation. In the Korean studies literature, a similar shift is seen through the work of Ji Hyun Ahn (Reference Ahn2015) who uses the example of biracial Korean American celebrities as representative of Korean cosmopolitan desire attached to Whiteness. I argue further that this also allows these desires to remain pinned to the Korean nation. All these examples demonstrate the unstable nature of racial categories, but still elucidate Whiteness as a center of racial power.

Thomas Baudinette (Reference Baudinette2016) tracks the receptive end of this recalibration of queer inter-Asian racialized desire in Japan. Baudinette uses Joane Nagel’s (Reference Nagel2003) concept of the ethnosexual frontier to illustrate how gay men from other parts of Asia who pursue relationships and encounters with Japanese men are marginalized from intercultural queer contact spaces in Tokyo. Baudinette explains how many queer bars function as ethnosexual frontiers in Tokyo and are structured around the interactions between Japanese/White gay men. As a result, Asian men from China and Korea become “ethnosexual invaders” and are locked out of these spaces. All of these critiques, I believe, highlight a central theoretic offered by critical race theory in that although the socially constructed nature of race, ethnicity, and nationhood intersects with sexuality creating diffuse positionalities and subjectivities, it still marks out Whiteness as a symbol of power (Delgado and Stefancic, Reference Delgado and Stefancic2017).

Considering the under-examined nature of race as mediator in the production of queer desire in a Korean context, and in light of the racial hierarchies that exist in the way Korea racializes its foreigner population for neoliberal purposes, I deploy Suganuma’s (Reference Suganuma2012) position of using the Korea/local–Western/global binary to make known some of the multiplicities of queer experiences in contemporary Seoul. These experiences I apprehended behind the veil of the binary, as a researcher with clear ancestry and racial coding connected to the global south whilst interpellated as a foreign researcher attached to an American university with New Zealand citizenship. My complex rendering in the field is what led me to deploy the specific research strategy I detail in the next section.

METHODOLOGY AND POSITIONALITY

As an Indigenous Pacific researcher I am well-rehearsed in the hazards of unreflexive cross-cultural inquiries, coming from communities whose experiences with Euro-American researchers has led to even the word research being considered a “dirty” term (Smith Reference Smith2012; Naepi Reference Naepi2019). The inherent danger with cross-cultural research is essentialism and misinterpreting a social praxis or phenomenon based on one’s unacknowledged biases and limited knowledge of the cultural context (Choi Reference Choi2006). To begin to ameliorate this, one’s methodologies and positionalities must be made visible as the researcher and appropriately contextualized not only for understanding the rigor of analyses (Bryman Reference Bryman2016), but to minimize potential discursive and material harm on participants and communities one is working with (Smith Reference Smith2012). I do believe that for many non-Western peoples living in the imagined postcolonial moment, even the act of theorizing is loaded with the potentiality of violence.

Therefore, this study should not be viewed as a conventional ethnographic inquiry, as the goals of PRM diverge from cultural anthropology in important ways (as further described below). George E. Marcus and Michael M. J. Fischer (Reference Marcus and Fischer2014) argue that cultural anthropology attends to two critical functions. First, to salvage distinct cultural forms of life to challenge the idea of homogenization spread through globalization; second, to provide a lens of reflexive cultural critique for the West, or in their case, the United States. The second attendant goal is problematically conceived from a PRM perspective, as it does not adequately deal with the inherently extractive nature of this framing. For a reflexive critique of the West, the referential (non-West) must still be re-presented. This re-presentation is often still undertaken by the Western researcher or researchers trained and socialized into Western disciplines and methods that does not alleviate the risk of, and potential harm inflicted by, mis-re-presentation (Choi Reference Choi2006; Hau’ofa Reference Hau’ofa1994; Smith Reference Smith2012; Teaiwa Reference Teaiwa1994). Thus, PRM focuses on participatory methods that include participants as important co-constructors of knowledge to overcome the danger of disempowering, not just misrepresenting, participants’ worlds (Naepi Reference Naepi2019).

I argue that PRM promotes relational understanding between researcher and participant, and in a case like Korea, also means research interactions between researcher and participants take place beyond Western eyes (Thomsen Reference Thomsen2019). These interactions are situated epistemologically and paradigmatically on the edges of cross-cultural encounters (Teaiwa Reference Teaiwa2001). I argue that the generative qualities of these edges open innovative modes of thinking about how experiences of racialization can be apprehended in a queer setting. Further, I suggest that critiques of cultural relativism can be overcome through the collaborative, sensitive, and empowering way in which PRM generates intellectual insights and social commentary. This positions participants as co-constructors of knowledge, not just informants used to excavate social truths.

Talanoa dialogue is a method of qualitative interview inquiry that is rooted in Pacific oratory tradition as a type of inclusive, participatory, and transparent dialogue. Timote Vaioleti (Reference Vaioleti2006) defines it as a conversation, a talk, an exchange of ideas or thinking, whether formal or informal. Talanoa overcomes methods that disempower informants by legitimizing researchers’ exchanging personal stories that explicitly express feelings with participants. It allows people to engage in social conversation, which may lead to critical discussions or knowledge creation that generates rich, contextual, and interrelated information to surface as co-constructed (Vaioleti Reference Vaioleti2006). Trisia Farrelly and Unaisi Nabobo-Baba (Reference Farrelly and Nabobo‐Baba2014) state that empathy is central in talanoa, in that a researcher recognizes and makes central the worldview of the participants, especially when research is carried out with non-Pacific peoples (Vaioleti Reference Vaioleti2013). Talanoa also encompasses a practical method and theoretical concepts (respect, compassion, and relationality) used to enact the method and analysis of the information as it is deeply interconnected with concepts of cultural engagement (Fa’avae et al., Reference Fa’avae, Jones and Manu’atu2016).

In addition to talanoa dialogue, the Samoan concept of the vā also mediated this research praxis. The concept of the vā deals with holistic forms of identity formation predicated on co-belonging and relationship building (Refiti Reference Refiti2008). Epistemologically, the vā is encoded with respect, service, and hospitality (Lilomaiava-Doktor Reference Lilomaiava-Doktor2009). Albert Wendt (Reference Wendt, Hereniko and Wilson1999) explains that the vā is the space in-between, the between-ness, not empty space, not space that separates but space that relates, that holds separate entities together. Sāmoa’s traditions and protocols explain that the nature of a Sāmoan being is relational. There is myself and yourself, through myself, you are given primacy in light of our collective identity (Tamasese et al., Reference Tamasese, Peteru, Waldegrave and Bush2005). Therefore, in social research, the vā precipitates an understanding that the knowledge being generated is co-constructed in a shared space held by both the researcher and participant, not just observationally excavated (Thomsen Reference Thomsen2019). Unlike conventional ethnography, PRM acknowledges relationality between multiple parts of a researchers’ positionalities and that of participants as a site of knowledge generation (Naepi Reference Naepi2019).

I argue that this insight from PRM shares meaningful connection to a Korean worldview or view of self that is heavily impacted by relationality (which can also be framed as a type of collectivism) (Choi and Kim, Reference Choi, Kim, Yang, Hwang, Pederson and Daibo2003; Ho Reference Ho, Ivanhoe, Flanagan, Harrison, Sarkissian and Schwitzgebel2018). The Korean language demonstrates this symmetry, where the lexico-grammatical structure of Korean is formally dependent upon social and interpersonal factors such as symmetrical/asymmetrical relationships, kinship, gender, age, profession/vocation/trade, as well as socioeconomic status (Kim and Strauss, Reference Kim and Strauss2018). This shares strong parallels with the Sāmoan language where interpersonal factors such as age, rank, status, familial position, gender, etc. determine the appropriate linguistic system to be used in relation to others (Taumoefolau Reference Taumoefolau, Agee, McIntosh and Culbertson2013). Both systems are predicated on an innate understanding of culturally embedded contexts of respect, space, and relationality. In reflecting on my own positionality as a researcher, it was impossible for me not to be foregrounded by the vā. When interviewing participants, I took the active position that considered informants not as mere data points, but relational subjects in which I, the researcher self, was also constituted.

In a queer studies context this is a valuable insight. David Eng, Judith Halberstam, and José Esteban Muñoz (Reference Eng, Judith Halberstam and Muñoz2005) define “perverse modernity, body and knowledge as those that exist outside the boundaries of sanctioned time and space, legal status, citizen-subjecthood, and liberal humanism” (p. 13). Indeed, their critique is that there is no fixed embodied queer subjectivity, in that inner subjecthood can only be rendered visible by examining surfaces and external conditions that make certain subjectivities viable (Suganuma Reference Suganuma2012). In this research context, queer experiences in Korea are made intelligible through the medium of race and an exploration of the racialized texture of the Korea/local–Western/global binary. As a queer Sāmoan researcher, I am legible in this space not just through my queerness, but also through my racialized positionality. Not only does that shift what informants may wish to make known in our interactions, it also limits the realms of theorizing available to this research. ‘Contact moments’ between myself as researcher and participants were the site of knowledge generation, therefore this research can only seek to understand insights that surface because of my positionality as the racialized researcher.

RESEARCH PROCEDURE

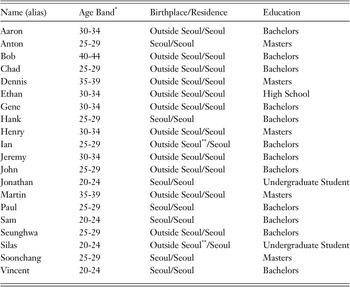

Data for this article were drawn from a wider study that looked at the ways Korean gay men in the U.S. and Korea negotiated sexual (in)visibility, however, this paper constructs its sample from participants based in Seoul only. Participants were recruited mostly through snowball sampling. They were invited to participate in open dialogues, where we talked about a range of topics that related to gay life in Seoul. I formally interviewed a total of twenty men across twelve months of fieldwork during 2017 and 2018 (see Table 1 for demographic information). The sample is of predominantly young to middle age self-identified gay men in their twenties to late thirties. They are well-educated and most had moved to Seoul later in life. To protect their confidentiality, all have been assigned aliases and more specific demographic information is withheld. Nonetheless, all interpretations offered in this paper must be read with these demographic caveats in mind and any shortcomings in the range of the sample, I believe, can be used to facilitate further research in this space.

Table 1. Participant Profiles

* An age band is used for confidentiality.

** refers to participants born outside Korea.

Recruitment procedures for the study meant rapport was built first, in that no talanoa took place with participants until we achieved a degree of familiarity. Building meaningful relationships with participants is a key feature of PRM (Naepi Reference Naepi2019). This often meant meeting each other before the actual interviews took place to get to know each other as people. The purpose of these meetings was to build not just rapport, but to establish participants’ confidence and an acknowledgement of their mana (spiritual power, strength, authority) as co-constructor of knowledge. Talanoa dialogue can only be effective when inherent power-imbalances are accounted for to allow for free dialogue to take place uninhibited by social hierarchies (Fa’avae et al., Reference Fa’avae, Jones and Manu’atu2016). These talanoa were recorded digitally with participant permission and transcribed manually. Transcripts from the fieldwork were coded openly using Nvivo software, then went through a process of axial coding to identify and synthesize themes (Strauss Reference Strauss1987). Following this, the themes were contextually placed against existing literature that looks at race/racialization and foreigners in South Korea as well as literature on queer Asia and my interpretations as researcher. What follows is what I term a thematic talanoa (Thomsen Reference Thomsen2019, Thomsen et al., in press) that allows the voices of participants to be centered in the pages, whilst analyses and theory is built around them. I argue that this approach was appropriate in that my open sharing of my own culture, worldview, experiences, and stories of living abroad in Korea for nearly a decade, in the U.S., and in my home countries is what led participants to feel comfort in sharing deeply and directly. But more importantly, this research approach developed trust and confidence in participants of my legitimacy as a researcher in a Korean space.

Researcher: When we talk about family life in Korea, I guess I feel like I can relate a bit more than another Westerner in the sense I was raised Sāmoan, and Sāmoan is my first language. For us, our family and their well-being is part of our identity, and filial piety, although we don’t call it that, is a central part of how we interact with our parents and other people older than us.

Informants responded positively to this aspect of my positionality as demonstrated by this response from one of the informants post-talanoa:

Participant: I felt really comfortable with your interview style, I was interviewed by a woman last week about the drag culture in Korea, and it was really uncomfortable, she didn’t really know what questions to ask most of the time that were important, [this] interview was so much easier, we spoke for an hour and it flowed freely.

There is no intention in the thematic talanoa to hide the impact my subjectivity had on subsequent discussions. Rather, what the thematic talanoa highlights, I believe, is how my racialized positionality as researcher led to extremely candid conversations around race and sexuality that I highly doubt would have been possible with a White Western researcher, as Whiteness often constituted the subject of the conversation. PRM highlights the agency and mana of participants (Fa’avae et al., Reference Fa’avae, Jones and Manu’atu2016; Naepi Reference Naepi2019; Thomsen Reference Thomsen2019, in-press; Vaioleti Reference Vaioleti2006, Reference Vaioleti2013). As such, a detailed ethnography on Korean queer worlds in my opinion should be carried out by Korean queer scholars. Therefore, the interpretations articulated here should not be taken as an attempt at constructing a definitive re-presentation. I only aspire for this article to present a complex understanding of racialized queer multiplicities generated through our intercultural research contact moments that may open further areas of investigation.

The thematic talanoa is broken into three themes: pervasiveness of White gay men in Seoul; reproducing/resisting race hierarchies in the construct of the foreigner; big dicks and potato queens: ameliorating racial deficits.

THEMATIC TALANOA

Pervasiveness of White Gay Men in Seoul

Seunghwa: White, but I’m not necessarily looking for White men. I also dated a half-Mexican, half-White guy.

Researcher: How do you usually meet them?

Seunghwa: Apps. Jack’d, Grindr, and Tinder.

Researcher: When you use these apps what are the common types of foreigners that you come across?

Seunghwa: White Americans usually. I think it’s because there are many English teachers and students. When it comes to English teaching jobs, I know they prefer White instructors, that’s why.

In this excerpt, Seunghwa details why they believe that White gay men are prominent in Seoul’s gay spaces. In fact, all participants expressed that the most common type of foreigner they met in Seoul’s gay scene was White. They also all explained that they had at least dated or had sex with a White gay man at some point in their dating life. All participants had a similar explanation to Seunghwa; they felt that there were more White men in Seoul because the demand for English teachers gave them a pathway into Korea’s largest metropolis. Nagel’s (Reference Nagel2003) concept of the ethnosexual frontier explains how particular erotic spaces that lie at the intersections of racial, ethnic, or national boundaries, are penetrated by individuals forging sexual links with ethnic Others across ethnic borders. Building on Nagel’s concept of the ethnosexual frontier I also argue that Seunghwa’s excerpt, supported by other participants, demonstrates how Seoul’s ethnosexual frontier is also a digital one. Itaewon, Seoul’s foreigner district, also boasts “homo hill” well-known for hosting one of Seoul’s most vibrant gay bar scenes. Itaewon is where foreigners and Korean gay men regularly meet for drinking and socializing activities. Yet, all participants in this study were primarily using dating apps to meet men to organize sexual liaisons and dating—through apps like Grindr and Jack’d they had met their White sexual or dating partners. It appears then that it is the digital ethnosexual frontier that is facilitating intercultural contact between participants and foreign gay bodies. While Korean gay men in the past have used internet sites like Ivan Korea and Daum to facilitate gay socialization and dating (Cho Reference Cho and Henry2020), these were predominantly used only by Korean men. Dating phone apps provided opportunities for foreign men to penetrate the ethnosexual frontier and facilitate intercultural queer contact and desire. Soonchang, another participant, had this to offer in our talanoa around the proliferation of White gay men in Seoul:

Soonchang: There are more White guys here than Black guys. Out of all the foreigners in Korea they’re mostly White guys, even more than other Asians in Seoul. Southeast Asians are more like factory workers, so they don’t live in Seoul. They live in rural areas. But for me it’s not about that. It’s whether they can hold a conversation. I can hook up with any guy. When it comes to dates, their ability to hold a conversation with me, anything we can talk about—if we don’t have anything in common with each other, we can’t go on dates with each other. I don’t think I have a special thing for White guys, but I date White guys.

Interest convergence theory explains how within racial hierarchies the interests of subjugated racial groups are only acted upon favorably when these interests converge with those of the more powerful (Delgado and Stefancic, Reference Delgado and Stefancic2017). I argue that the pronounced presence of White English teachers in the Seoul gay scene, according to informants, is related to an inverted transnational interest convergence, where the interests of two dominant groups across borders collude to reinforce racializing processes endemic to their own societies. In order to qualify for an English teaching visa (E2) in South Korea you must hold a bachelor’s degree and citizenship from one of the “big seven”—the United States, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, or South Africa (Thomsen Reference Thomsen2018). In the United States, as an example, there are simply far more White college graduates than Non-Asian People of Color.

According to the U.S. Department of Education (Reference Education2017), in the 2014–15 school year, the number of bachelor’s degrees awarded to White students in the U.S. was 1,210,523, whilst during the same time, 192,725 were awarded to Black students. For Black students this number represented a sizable statistical increase of 41% from ten years prior. Moreover, Black students in the U.S. are less likely than White students to complete college (Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, Dundar, Huie, Wakhungu, Yuan, Nathan and Hwang2017). This suggests that the number of White graduates in comparison to Black graduates forms a much larger White pool from which South Korea’s English teacher demand can draw. In this way, America literally produces more White graduates able to activate their citizenship to make use of immigration pathways like the E2 Visa to teach English in Korea. More research needs to be undertaken in this space, however, the idea that there are simply more White graduates to choose from is supported by Wagner and Van Volkenberg (Reference Wagner and Volkenburg2011) who assert that most native-speaking English teachers in South Korea are White.

By claiming that White men are just more likely to be in Seoul in contrast to Southeast Asians who, Soonchang explains, are likely to be factory workers, their narrative supports the findings advanced by Dong-hoon Seol (Reference Seol2012) that Korea’s foreigner community is racially-hierarchized. Soonchang constitutes the White foreigner as designated by the Korean state, by view of profession, as part of the urban middle class. What is also significant about this is that it structurally mediates opportunities for developing intercultural queer desires, whereby according to Soonchang, dating White guys as the proxy for foreigners happens simply because there are more of them in Seoul. This is of course likely to be more complex, but at the very least, this shows that special immigration pathways for English teachers from places like the United States directly impact the nature of who can participate in Seoul’s queer ethnosexual frontier.

Left out of this space are gay men from Southeast Asia and South Asia who, according to Statistics Korea (Reference Korea2017), along with ethnic Korean Chinese migrants make up the bulk of Korea’s foreigner population. Thus, the elevated presence of White gay men according to participant perspectives demonstrates the power of Whiteness to structure foreigner and queer cross-cultural spaces in Korea. These men, who are factory workers according to Soonchang, are made invisible through their deployment by the Korean state as labor migrants dispersed in industrial and rural areas. I conclude that we are witnessing twin racial processes that take place in different locations (Korea and the United States) converging in the narratives of participants. Racialization in the U.S. provides the supply of English teachers for a neoliberal driven Korean state, which institutes an immigration system that racializes its foreigner population spatially. The result is that access to the ethnosexual queer frontier in Seoul is left predominantly to Westerners and White gay men to negotiate with many of the participants.

Reproducing/Resisting Race Hierarchies in the Construct of the Foreigner

Martin: One of my gay friends from Malaysia, he loves Korea, but he has had many bad experiences with Korean gay guys—racist experiences. It makes me feel awful. In Korea there are ranks related to race. Koreans come first, second would be Japanese, third are White Westerners or Taiwanese, and after that all colored people are the same. In my experience that is how people think. It’s not just gay people, it’s across the board. If you’re a Korean parent, it goes, Korean, Japanese, White Westerner, maybe Chinese is OK. Except that, they don’t like anyone else.

Martin’s comments highlight the way in which common forms of racism within the gay community in Korea were seen by most participants as a direct reflection of societal-wide racialization processes. This is an important insight, as Peter A. Jackson (Reference Jackson2009) and others have argued convincingly, that queer subjectivities also emerge through specifically local forces in Asia. In the Korean case, I argue that pre-existing racial hierarchies have also helped to render visible queer Korean experiences. Martin connects this to heteronormative constructs which tie racialized preferences in marriage partners to Korean ethnonationalist racial hierarchies. This interpretation is supported by literature that stories how Korean parents, in lieu of Korean spouses, preferred that their sons married women from countries who demonstrated the ability to easily assimilate into Korean life both culturally and aesthetically (Kim Reference Kim2011). Within this framework, however, White gay men were still given a special category in Martin’s interpretation. They were included as an acceptable other. Korean scholarship on globalization suggests this is because of the proximity of Whiteness to global power. However, other work shows that the desire for White skin is also historical and locally tied to class. “In Korea, people who have White skin have long been told that they look noble. In the upper class of the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), children washed their faces with peach flower water to make their skin clean, White, and transparent” (Li et al., Reference Li, Min, Belk, Lee and Soman2008, p. 445). This suggests that local colorism processes may also be at play.

When I spoke with Gene about their experiences of dating with foreigners, Gene took an accusatory tone toward the racially inflected dating patterns of Korean gay men. Gene was a graduate student studying in the United States when we met. They came from a supportive family and loved hanging out with foreigner friends. Although critical of this practice, Gene was still a participant, co-opted into this scheme of racial hierarchy, offering this toward the end of our talanoa:

Gene: In Korea, gay society is really small, especially in Itaewon. We all know each other. I can know who they are, or who their ex-boyfriend is. So, bad rumors can follow you. I’ve met a lot of exchange students and they’re kind of like playboys, you know? They’re here for a short time and have fun, then leave. Especially White, as they are popular here in Korea, so they are very rude and not polite.

Researcher: Do you believe that White gay men are treated better in Korean society?

Gene: Yes, I found Korean society very racist because we prefer White people. I have a Filipino-American friend and he was rejected as a native speaker teacher in Korea because of his ethnicity.

Gene’s narrative highlights how the process of racialization in the gay community is something that all informants were cognizant and critical of to certain degrees. Gene, however, never sought distance from the practice. In acknowledging a racial preference in dating, it highlighted their role in the racialization process that presents a type of complicity in its reproduction. Much like Kang (Reference Kang2017) advances, desirability of partners is mediated through social categories and hierarchies. If racial hierarchies position White gay men at the apex of the foreign community, and postulate a proximity to power and cosmopolitan identity, then Gene’s narrative acknowledgement is important. It demonstrates how racialization can work insidiously to co-opt even racialized queer subjects who try to resist this framing.

A theoretical intervention I find useful here is the concept that Kang (Reference Kang2017) articulates in the Thai setting, where desiring Whiteness is not tied to Caucasian bodies, rather to “White Asians” who represent a type of gaypergamy (upward gay social mobility through interracial partnering) and Asian modernity. Literature reviewed on race in Korea points to the neoliberal production of Whiteness as an affect, through which cosmopolitan-minded Koreans continue to position themselves. However, Martin’s excerpt complicates this idea. Martin argues that East Asians are more desirable for Korean families for their ability to blend into the Korean nation. Thus, the desire for other East Asians is likely both a desire for sameness and a connection to an association with White skin that locally has been tied to class and nobility. This likely impacts what Baudinette (Reference Baudinette2016) identified in Japan, where Korean men in their study preferred to date Japanese men, and speaks to Kang’s (Reference Kang2017) gaypergamy findings in Thailand. An important distinction from Korea, though, is how foreigners are expected not to disrupt notions of Korean national identity (Hundt et al., Reference Hundt, Walton and Lee2019). In other words, foreigners are not meant to threaten ethnonationalist constructs and the Sunhyol narrative when they marry into the Korean nation. As Martin demonstrates here, Whiteness, however, is an acceptable alternative. This acceptance is derived in benefit to the nation and state due to its proximity to power in the global context. However it is also connected to local contexts of desire that are tied to class, nobility, and nationalism.

Big Dicks and Potato Queens: Ameliorating Racial Deficits

Soonchang: I prefer handsome, hung, preferably taller than me, brain is definitely a plus, not only face is important for me. You should be smart, so if you’re not smart, at least have a big dick. Redeeming qualities, (joking) I have a scorecard to check you off against, if you don’t have this you should have that at least. [Laughing] Yeah, race [long pause] I had one fling with a Black guy when I was 21. He was really kind. I was younger and he was really good looking, taller, hung, really good in bed, and he was kind to me.

Researcher: So, did you have any preconceived stereotype of Black guys before you dated him, like had you heard the trope about Black guys being more hung for example?

Soonchang: Of course, I had heard a lot of stereotypes.

Researcher: What are other stereotypes you have heard?

Soonchang: Like I said before, White guys have BO (body odor), I have a good sample size, honey. I lived in Australia and I fucked a truckload of White people. In my sampling that stereotype is true, and yeah Black guys in general, I think they do have big dicks, comparatively. I know because I sucked them and I know it. I think the dick size, the genitalia. Asian guys in general do have smaller dicks. I’m not joking, it’s more like an observational fact now. I can tell you that I’ve passed the sample size of thirty, yeah the central theorem and all that shit. There’s a term, a potato queen, and for me I asked myself if I’m a potato queen, and I’ve definitely dated more White guys than any other race. I don’t want to be one, but I made peace with it. I am, in a way.

In this very candid exchange with Soonchang, many stereotypical images of the racial other in the gay community in Western countries like the United States are put on prominent display. In particular, the characterizations of Black men with large genitalia and Asian men with smaller penises recall images identified in previous studies by Cho-suk Han (Reference Han2007, Reference Han2008a, Reference Han2008b), Niels Teunis (Reference Teunis2007), Glenn T. Tsunokai and colleagues (Reference Tsunokai, McGrath and Kavanagh2014) among others. These studies identify harmful racial stereotypes as part of the discursive elements in which non-White gay men are constituted within the gay community in the United States. To see them so prominently on display in Seoul through Soonchang’s narrative as well as those of other participants suggests that there is a link between the two communities’ discursive practices. Soonchang connected this to their experiences of living abroad. What is also important to note is that the term ‘potato queen’ or gay Asian men who have a preference/fetish for White men, works as a binary opposite for the term ‘rice queen’ or men who have a preference/fetish for Asian men (Kang Reference Kang2017). In contrast though, there is no binary term for an Asian gay man who fetishizes Black men or men of color.

However, much like Soonchang explained in an earlier exchange, race was just one piece of the attractiveness puzzle. When it came to the issue of racialized foreigners/others, hypermasculinity could help to ameliorate a racial deficit related to racial coding. In other words, possessing a muscular body with low body-fat, being tall, conventionally handsome, and strong allowed racialized others to move from outside the realm of exclusion to inside the sphere of attractiveness. Voon Chin Phua (Reference Phua2007) also found this in their study on the dating experiences of Asian American gay men. This was best explained by Martin when we talked about racialization in our talanoa. Previously, Martin had laid out their racial preferences for dating in Korea. In their view it went Koreans first, East Asians second, with Whites being acceptable and the rest disqualified. However, if someone were able to embody physical characteristics that were desirable, for Black men—hypermasculinized, well-endowed—they could overcome this racial deficit.

Researcher: In terms of body types, the Korean gay community is similar to a lot of places, I hear? Tall, muscular hunks are popular too.

Martin: Yes, those are the major groups, then the second group is the bear group, it’s quite big in Korea. Korean gay culture is affected in part by Japanese culture. In Japan bears are really popular so we have that, too. That’s second rank, the third ranking is twink type, KPOP performers. First, well hung and built, and in terms of racial preference it’s the same as what is in Korean culture as a whole. […] If you have the body type someone likes, hunk, muscular, or if someone likes bears, then race and all that sort of thing doesn’t matter.

Ultimately what this demonstrates is the unstable nature of racial categories when they encounter other axes of power. In this case hypermasculinity, and characteristics associated with strength, health, vitality, etc., erase the parameters of a racialized wall. In their study of Japanese gay men, Jonathan D. Mackintosh (Reference Mackintosh2010) argues that hypermasculinity was inscribed on the bodies of White men following the occupation of Japan in the postwar period. Eventually, Japanese men came to take on White men’s desirability/masculinity through what they call eugenic imaginations—meaning, modifying bodies to reflect or mimic the qualities of hypermasculinity that precipitate queer desire. Among participants in Seoul, there was an understanding that hypermasculinity or other desirable bodies (bears in Japan) could be mapped onto any ethnic or racialized body. Therefore, hypermasculinity can manufacture an aesthetic in this case, seen as more desirable than congruence with racial hierarchies. This, again, demonstrates the mutability of racial categories in the production of queer desire.

CONCLUSION

This article has attempted to illuminate the complexities of transnational interest convergence and how it is refracted through the lens of race, narrated by Korean gay men through this brief thematic talanoa. I have argued that although queer Asia complicates the unsustainable globalization binary between the passive, receptive Korea/local and the hegemonic queer trendsetter of the West/global, the Korea example demonstrates the persistent power of Whiteness as a referential propelled by its inherent construction as part of neoliberal forces. This symbolizes Korea’s international competitiveness providing access to global power and influence. As such, racialized hierarchies that exist locally are reinforced by the global in certain moments, resisted in others, but ultimately mark out the global as a mediating variable to Korean queer experiences.

Participants in this study demonstrated that in the Seoul gay community, the most common foreigners they encountered were, in fact, White English teachers. There is a spatial element related to racial and social class, in that participants understood this as a product of how Korea’s immigration system imbricated foreigners from divergent nations for different instrumental purposes. English teachers from wealthy, Western, and White (3 Ws) countries often were embedded in urban areas like Seoul, whilst the most populous of foreign populations in South Korea (ethnic Korean, Chinese, Thai, Filipino, and other Southeast and Central Asian groups) were dispersed to the rural and industrial areas as manual laborers and brides for rural men. These social narratives which are a product of wider societal processes tied to nationalism, capitalism, neoliberalism, and colorism, were all made intelligible by participants through the telling of their own stories as gay men in Seoul.

This story has been positioned on the edges of queer globalization, Korean studies, critical race theory, and Pacific studies. In doing so, I have demonstrated the potentiality of cross-cultural contact moments as a site for knowledge generation. This paper’s contribution has been both empirical and methodological. Empirically, it has helped to render further, in specific ways, the contours and uniqueness of Korean gay men’s experiences and subjecthood at the intersections of sexuality and race. More scholarship, both qualitative and quantitative, will need to be conducted to deepen the rendering of this space and to capture further the uniqueness of how Korean queer experiences are mediated by the race lens. The use of Pacific Research Methodologies such as talanoa dialogue and the vā in a Korean studies setting, I argue, also deepens the realm of hybrid methodological possibilities for Pacific studies scholars and opens up space for more meaningful research engagement between the Pacific and Asia in the future.